Abstract

Spending time in nature during childhood can improve mental and physical health, support academic success, and cultivate pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Increasing outdoor time during school can enhance the likelihood of those outcomes for all students. However, in practice incorporating outdoor time into the school day can be challenging. This study reports on barriers identified during the development phase of an action research project that aimed to increase outdoor time as a regular, repeated part of the elementary school day. Teachers (n = 22) and administrators (n = 3) in one school district in the Northeastern United States were asked to describe the barriers that limited their opportunities to take students outside. Data indicated 33 discrete barriers and 5 themes that cut across the barriers. Interactions and overlap across barriers increased the challenges encountered by teachers. A systems thinking approach is suggested to increase outdoor time in schools.

Introduction

Spending time in nature during childhood has the potential to bring many short- and long- term benefits to both people and the planet. Research has documented positive outcomes related to mental wellbeing, physical health, as well as social and academic development, (Bratman, Hamilton, and Daily Citation2012; Corraliza, Collado, and Bethelmy Citation2012; Lieberman, Hoody, and Lieberman Citation2000; Tillmann et al. Citation2018; Williams and Dixon Citation2013).Moreover, evidence suggests that spending time in nature during childhood may cultivate pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors in adulthood (Chawla Citation2009; Wells and Lekies Citation2006; Wells and Lekies Citation2012). Even small amounts of nature can help, and benefits related to mental wellbeing have been documented in as little as ten minute doses (Meredith et al. Citation2020) and two hours over the course of a week (White et al. Citation2019). These outcomes are critical at a time when child physical and mental wellbeing are declining (Sahoo et al. Citation2015; Twenge et al. Citation2010), and the need for environmental stewards is increasing (Whitmee et al. Citation2015). However, children today are spending less time outdoors than in previous generations (Charles and Louv Citation2009; Louv Citation2005; Rickinson et al. Citation2004; Waite Citation2010). Access to the benefits of time in nature has become more pressing as the COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on the mental health of young people, and schools have been called upon to increase support for students’ mental wellbeing (United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General, 2021).

This study was one component of a project with dual programmatic and research goals. Our programmatic aim was to increase the time students in three elementary schools spent in the natural spaces on the school grounds by incorporating time in nature as a consistent, repeated part of the school day. As a first step toward the goal of getting students outside and to guide the further development of our project, we worked with the partner schools to understand their existing contexts. We conducted an exploratory qualitative study utilizing interviews and focus groups to identify schools’ existing efforts related to outdoor time as well as existing barriers that limited teachers’ opportunities to take their students outside. The findings related to the barriers teachers encountered are presented here. While this project was conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the findings may be even more relevant today for schools seeking to support children’s health and wellbeing through time in nature.

The decline—in recent decades—of time spent in nature has been attributed to many factors, including increased focus on performance over play, increased time in school with decreased recess, greater use of technology, decreased access to nearby nature for urban populations, and more fear of letting children play outside unsupervised (Charles and Louv Citation2009; Hartig et al. Citation2014; Louv Citation2005). Limited time in nature may be particularly prevalent among children in low-income urban neighborhoods, where youth have less access to or feel less welcomed in parks or other green spaces (Strife and Downey Citation2009) or among predominantly Black communities where repeated and unacceptable acts of violence against children playing outside have created justifiable fear (Pinckney et al. Citation2018). Louv (Citation2005) described this loss of nature contact as nature-deficit disorder and suggested it may produce long-term physical, mental, and social consequences. Indeed, young people today have higher levels of obesity (Sahoo et al. Citation2015), stress and anxiety than in previous decades (Twenge et al. Citation2010). This is particularly impactful in low-income communities where anxiety and chronic health conditions occur with greater prevalence than in higher-income communities as early as the first decade of life (Evans and Kim Citation2007). Concurrently, human activities have stressed the natural environment such that anthropogenic changes are negatively impacting global human health (Whitmee et al. Citation2015). These challenges have many causes, and spending time in nature is not a cure-all. Even so, increasing the amount of time children spend outdoors is a simple strategy that may mitigate these crises by improving mental and physical health in the short term and environmental conservation in the future. While many forms of contact with nature may support wellbeing (Tillmann et al. Citation2018), research indicates the development of pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors may need guided interactions with the environment (Chawla Citation2009; Wells and Lekies Citation2006; Wells and Lekies Citation2012). Schools could provide that guidance and, by increasing the time students spend interacting with nature, concurrently support students’ mental and physical health.

Integrating outdoor time into the school day can increase time in nature for many children, reducing disparities in nature access (e.g. Pinckney et al. Citation2018; Strife and Downey Citation2009), and facilitating the benefits for many. The structure provided by schools offers the possibility of ensuring a consistent ‘dose’ of nature at a level and in a manner that research suggests would foster benefits (e.g. Chawla Citation2009; Meredith et al. Citation2020). Such an approach can provide equitable access for all children rather than through extracurricular programs that may unintentionally increase outcome gaps between students with more resources and students with fewer (Feinstein and Meshoulam Citation2014). Incorporating natural environments into formal schooling has a long history (e.g. Handbook of Nature Study (Comstock Citation1986) first published in 1939), and substantial evidence of success; several reviews have outlined the positive impacts that outdoor learning – on school grounds and during school time – can have on academic, social, and behavioral outcomes (Ayotte-Beaudet et al. 2017; Blair Citation2009; Dillon and Dickie Citation2012; Rickinson et al. Citation2004; Williams and Dixon Citation2013). With outcomes well-aligned with the goals of schools, nature-contact during school time seems like a natural fit.

Despite the alignment of school goals with the benefits from nature contact, implementing outdoor time can be challenging. Scholars have noted high-level challenges to incorporating environmental topics in schools, including a mismatch of underlying paradigms (Stevenson Citation2007), politicization of scientific findings (e.g. for climate change (Kunkle and Monroe Citation2019)), and poor integration of environmental topics across education standards (Salazar et al. Citation2021). Previous research has identified barriers that limit opportunities to take students outdoors. Rickinson et al. (2004) distinguished between barriers that limit provision of outdoor time (concerns about health and safety; teachers’ lack of confidence in teaching outdoors; school schedules and curriculum requirements; shortages of time, resources and support; and wider changes within the education sector including rising student/staff ratios and greater focus on assessing learning outcomes), and those that limit quality when outdoor time occurs (structure, duration, and pedagogy of the program; students age, background experience with nature, learning preferences, physical or special education needs, and cultural interactions with outdoor activities; and characteristics of the place where outdoor learning occurs). Dillon and Dickie (Citation2012) identified similar barriers to provision, highlighting liability as part of the concern about safety and adding limited access to professional development as an additional category.

Studies of outdoor learning on elementary school grounds highlight differences across contexts. Additional barriers identified include limited suitable outdoor spaces in the school yard (Dyment Citation2005; Edwards-Jones, Waite, and Passy Citation2018; Oberle et al. Citation2021; Shume and Blatt Citation2019; Waite Citation2011), limited support from administrators (Dring, Lee, and Rideout Citation2020; Dyment Citation2005; Oberle et al. Citation2021; Shume and Blatt Citation2019), managing inclement weather and clothing (Dyment Citation2005; Edwards-Jones, Waite, and Passy Citation2018; Oberle et al. Citation2021; Shume and Blatt Citation2019; Waite Citation2011), treating outdoor time as an add-on rather than part of the core curriculum (Carrier et al. Citation2014; Dyment Citation2005; Oberle et al. Citation2021; Waite Citation2011), pressure to prepare students for standardized tests (Edwards-Jones, Waite, and Passy Citation2018; Shume and Blatt Citation2019; Waite Citation2011), vandalism of outdoor resources (Edwards-Jones, Waite, and Passy Citation2018), anticipated resistance from others, school policies (Oberle et al. Citation2021; Shume and Blatt Citation2019), and teachers’ content knowledge of outdoor topics (Dring, Lee, and Rideout Citation2020).

Notable among studies are the contradictory and nuanced findings within barrier categories. Dyment (Citation2005) found that time was not a barrier for outdoor learning in the school yard, while others found that time pressure from required curriculum (Edwards-Jones, Waite, and Passy Citation2018; Oberle et al. Citation2021; Shume and Blatt Citation2019; Waite Citation2011) and the time needed for planning and managing the logistics of outdoor learning (Dring, Lee, and Rideout Citation2020; Edwards-Jones, Waite, and Passy Citation2018; Shume and Blatt Citation2019) were barriers to using school grounds. Waite (Citation2011) identified a lack of motivation among teachers as a barrier to outdoor learning, suggesting that if teachers were motivated they could overcome the other barriers they encountered, while others found that motivation was not lacking (Shume and Blatt Citation2019) or did not translate into time outdoors (Carrier et al. Citation2014). It is clear that multiple barriers may limit outdoor time, and prominent barriers vary across contexts. The differences among the studies and nuances within the categories suggest we do not yet have the full picture of the barriers teachers encounter, nor do we have clear solutions or strategies to address the barriers to increase outdoor time.

Healthy kids, healthy planet project

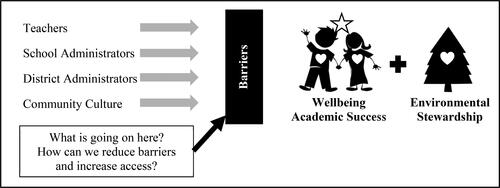

This study was part of a two-phase action research project with the primary aim to increase outdoor time in elementary schools in one school district in the northeastern United States. The underlying goals of the project were to (1) support students’ mental wellbeing and academic success and (2) promote the development of positive student attitudes toward the environment, via utilization of time outside during the school day. To that end, based on the research described above and discussions with school and district administrators, the specific goal of the project was to make outside time a regular part of the school week, so that each student would spend at least one hour of class time (i.e. time other than unstructured recess) outdoors each week in the natural areas on the school grounds.

As a first step, in Phase 1 we wished to learn about the existing opportunities educators saw for outdoor learning, the strategies that helped support their outdoor time, and the barriers that limited them from getting outdoors. The goal of Phase 1 was to collect and analyze data to guide the design of Phase 2 (reported elsewhere), so that Phase 2 could effectively increase consistent use of natural spaces on school grounds to enhance environmental education and wellbeing across the school day. Despite many affordances in this district related to outdoor time, in the Phase 1 data collection educators described encountering multiple existing barriers that greatly infringed upon opportunities to take students outside (see ). This paper reports on the barriers teachers described encountering that prevented them from taking students outside. The specific research question was: what barriers limit the inclusion of time in nature as a regular, routine part of the elementary school day? Strategies to support time outside are reported separately, and outlined in the Healthy Kids, Healthy Planet Toolkit (Patchen et al. n.d.).

Materials and methods

Context

Three elementary schools in one school district in a small city (population ∼56,000) in the northeastern United States participated in the project. The schools were located in different areas of the city, with one in a suburban neighborhood, one in a higher-density neighborhood near downtown, and one in the rural edge of the city. All three schools had multiple natural areas on the school grounds including access to woods, nature trails, garden plots, and playing fields. Two schools had small stands of apple trees, one had a pond, and two had existing outdoor classrooms consisting of benches in wooded areas. District administrators and the principals at all three schools were interested in increasing the time students spend in nature, and were enthusiastic partners during project development. Demographics for the three schools are shown in .

Table 1. School demographics.

Methods

This exploratory qualitative study used in-depth semi-structured interviews and focus groups (Given Citation2012) with educators (teachers and principals) to identify barriers that limit time outside during the school day. Through this approach, we sought to elicit information from the local experts—educators in the project district—about their experiences taking students to natural spaces in their specific context. Responses to open-ended qualitative questions identified barriers from the perspective of the individuals who need to navigate those barriers, and provided rich data (Given Citation2012) to understand the nature of those barriers. The project was submitted to the Cornell University Institutional Review Board and was qualified for an exemption (research protocol # 1812008455). Informed consent was obtained from participants before data collection.

Participants and data collection

Qualitative data on barriers were collected February–March 2019 through (1) three in-depth, semi-structured interviews with principals (n = 3) and (2) six focus groups with teachers (n = 22) at the three partner schools. Participants were recruited through presentations at staff meetings at each school. The recruitment presentations were the only project activities that occurred at the schools prior to data collection. The focus groups included 17 classroom teachers, two special education teachers, one social worker, one school psychologist, and one librarian. Ten of these teachers worked primarily with grades K-2, nine with grades 3-5, and three across K-5. Participants were primarily ‘early adopters’ who volunteered for the project because they were interested in taking students outside during the school day. The interviews and focus groups lasted 45–60 min during which we asked about existing opportunities to take students outside during the school day, challenges or barriers that limited opportunities, and strategies that might help increase opportunities. This paper reports on data that came from the questions on barriers. Teachers were asked about the factors that limited opportunities to take students outside, drawbacks they experienced from outdoor time, and specific times when they wanted to take students outside but could not. Principals were asked about barriers they observed that limited outdoor time, opportunities they saw in their school where teachers could take students outside but did not, and why they thought those times were not being used.

Data analysis

Interviews and focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data were coded using descriptive, simultaneous, and in vivo coding (Saldaña Citation2013) to identify experienced barriers and their underlying causes. Due to the lack of a standard framework in previous literature and in order to learn from the context experts (educators in this district) codes were developed inductively from the data. An initial round of coding was conducted, codes were edited to reduce overlap and capture nuance, peer coding was conducted on 10% of the data to assess reliability, and the data were then re-coded using the refined list. Summary descriptions of each barrier were written based on qualitative descriptions, and representative quotes for each barrier were identified. Data are coded as follows: FG1 (suburban school, teacher focus group 1), FG2 (suburban school, teacher focus group 2), FG3 (suburban school, teacher focus group 3), FG4 (rural school, teacher focus group 1), FG5 (rural school, teacher focus group 2), FG6 (urban school, teacher focus group 1), Principal 1/2/3 (principal interview, school/location not identified for privacy).

Finally, during analysis, several larger themes emerged that cut across the discrete barriers. These themes addressed overarching components that were manifest through a number of different specific barriers. For example, an overarching attention to equity across students was revealed through concerns about stigma related to borrowing outdoor clothing, or not wanting to exclude students who were receiving special education services, or worrying that spontaneous trips outside would disrupt learning for students who depend on a routine. It was informative to identify both the specific details (barriers) and overarching components (themes). Themes were iteratively refined during the coding of barriers, and the data were then re-examined for confirming and disconfirming evidence related to the themes.

Results

Barriers: descriptions and frequency

Educators collectively described 33 discrete barriers in nine loosely defined categories that affected opportunities to take students outside during the school day (). The most commonly noted categories were barriers related to Curriculum and Instruction, School Dynamics, and Time Pressures, while the least were Administration, Interest and Experience, and Spaces ().

Table 2. Barriers description and representative quote.

Table 3. Frequency of barriers.

As shown in (descriptions of each barrier and representative quotes), details of specific barriers within each category offer important nuance and an in-depth picture of the context teachers must navigate to take students outside. For example, the barriers linked to ‘time pressure’ show challenges related to not having enough time in the day, too much mandated content, and losing instructional time to transitions between indoor and outdoor activities. While the root cause of all of these barriers is a shortage of time, the facets of the barriers point to different issues teachers must navigate to take students outside, and different potential solutions to address them.

indicates the number of times each barrier was mentioned by teachers and by principals in independent data collection events. For example, ‘services’ was mentioned as a barrier in four of the six teacher focus groups, and zero of the three principal interviews. Multiple independent mentions suggests that a barrier may be a common experience for the different educators in the separate data collection events. Twenty of the barriers were mentioned in at least half of the teacher focus groups, with five (time in the day, student/staff ratios, policies, student background experience, physical location safety concerns) mentioned in all six focus groups. Five barriers were mentioned by all three principals (weather, time/space in standards, transitions, policies, physical location safety concerns). Only one barrier (physical location safety concerns) was mentioned in all six teacher focus groups and three principal interviews. Nine barriers were mentioned in teacher focus groups but not in any principal interviews, indicating that principals have a different experience of outdoor learning than teachers and may not be aware of the barriers that teachers encounter.

Themes across barriers

Five themes cut across the discrete barriers. These themes identify factors that complicate efforts to overcome specific barriers or ‘one-size-fits-all’ solutions and add to the challenges teachers face. Understanding them may inform efforts to increase outdoor time.

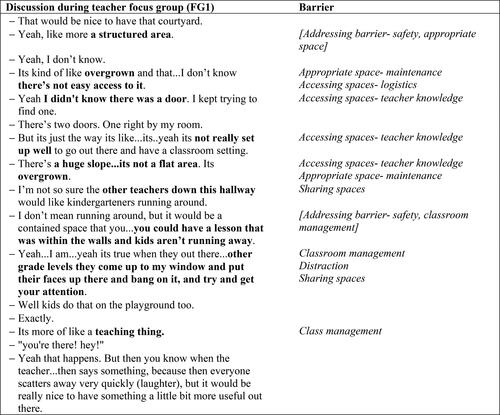

Theme 1: overlapping barriers limit opportunities

Teachers’ descriptions indicated that barriers did not occur in isolation, and that part of the challenge in using the outdoors for learning was navigating multiple barriers at once. For example, in one focus group, three teachers discussed an enclosed courtyard that existed at their school, and the range of barriers that prevented them from using the space (see ). Teachers stated that the enclosed space would allow them to have outdoor lessons without worrying about students running away, but that the space was not easy to get to or they did not know how to get in (access barriers); the landscape, set up, and maintenance were not conducive to class activities (appropriate space barriers); and, since the courtyard was ringed by classrooms, having a group of students there could easily disrupt other classes (sharing space, classroom management, and distraction barriers). While each of these barriers are relatively simple to address individually—find the door, cut the grass, set up seats, teach appropriate behaviors—the space could not be used effectively unless all the barriers were addressed simultaneously. Despite the safety and classroom management benefits of having an enclosed outdoor space and teachers’ stated interest in being able to use the space, the courtyard was not used for outdoor time. In this case, the combination of barriers prevented interested and motivated teachers from using a potentially beneficial outdoor space. This suggests that the co-occurrence of multiple barriers is itself an additional barrier to taking students outside.

Theme 2: the school-wide schedule for staff and instruction presented a substantial barrier

A second theme that was clear across the barriers was that the school-wide scheduling of staff and instruction impacted opportunities for classroom teachers to take their students outside. Several teachers indicated that the schedule of specialist or enrichment services was a substantial barrier to time outside as it limited their flexibility to shift topics or strategies to support outdoor learning. Additional services such as special education, reading support, or enrichment activities either push in (the specialist instruction occurs within the classroom) or take students out of classes for short lessons. In many cases, the schedule for these services is set across a school or district, and the classroom teacher does not control when they occur. As one teacher said, ‘If you have students who have services, it’s not necessarily scheduled where you could take your class outside at the spur of the moment, because somebody’s going to speech or somebody’s receiving OT [occupational therapy]’ (FG6 –School 3, Focus Group 1). A second teacher described how on ‘band day,’ there were small groups of students missing from class across the whole day, leaving no time in the schedule when the entire class could go outside. Teachers were unwilling to take everyone except the students receiving the specialized lessons outside, and unwilling or unable to ask the specialist to conduct their lessons outdoors. For others, the schedule of services broke the day into chunks that were too short for effective outdoor activities. As one teacher explained,

It could be half an hour at the most. Because of the block of time you have, with other teachers coming and taking kids…like there’s a limited time when you have everyone there or you have a provider that’s with you, that’s usually a half hour block. So you….you would explain, get outside, and get back in for the next transition. (FG1FG1)

Along with specialists and enrichments, the allocation of support staff across the school can also be a barrier. Teachers expressed concern about student-teacher ratios when taking students outside. Although many teachers stated that they had teaching assistants or aides in their classrooms, they explained that these extra adults may have multiple roles in the school and not always be available to go outside with the class. As one said,

a lot of our support is pulled for recess duty. So even if they’re assigned to your class, some of them are at recess duty during parts of the day and that leaves you a little bit understaffed to do something like that. (FG4)

The scheduling of staff, specialist instruction, and enrichment across the school, determined by someone other than classroom teachers, reduced the number of times teachers had an opportunity to take their classes outside. This is a substantial structural barrier—teachers cannot take their classes outside if there is not a time in the schedule to do so.

Theme 3: equity issues affect outdoor opportunities

A third theme that cut across the different barriers was that teachers sometimes chose to stay inside in an effort to provide an equitable experience for all students in their classes. This occurred for multiple reasons. First, as described in the previous theme, a major reason was to support students who received special education services or additional instruction. Teachers were wary of taking everyone except the students receiving special education services outside, for fear of singling out those students or ‘punishing’ them (through missing the exciting outdoor time) for needing those services, and concerned that asking the specialist to conduct the lesson outside might reduce the time or quality of the instruction the child received. As one teacher said, ‘I can’t just be like ‘yeah, we’re going outside for the morning’ because kids have services they need and I have to consider that too’ (FG3).

Second, teachers indicated concerns about equity related to clothing. For some, lack of appropriate weather gear created stress for students, and teachers needed to ‘[make] sure there’s equity among all the students and access is there for everyone’ (FG5). For others, expectations or limited resources at home meant students were concerned about getting their clothes dirty. As one teacher said,

Last year there was, I think maybe three kids who would get in trouble if they got dirty. So they didn’t want to go out when it was muddy or anything because they didn’t want to get their shoes dirty and they would get yelled at or punished in some way. And that was kind of a big issue for those three kids. (FG3)

While all three schools in the study had clothing ‘banks’ available in the nurse’s office, teachers noted concerns about stigma associated with wearing borrowed or ill-fitting clothes, and the logistics of getting clothing for an individual student when they needed it without increasing stigma by singling them out.

Third, teachers who worked closely with other classes at the same grade level considered fairness for the students across their classes. As two teachers said,

T1: ‘So the whole fourth grade, so we usually don’t just say “one class is going out while everybody sits miserably inside wishing they could go out now.”’

T2: ‘When one of the three of us can’t, the other two of us aren’t going to. So if she’s all “I have a teacher coming in to do such and such lesson, it’s not good for me,” we’ll just not.’ (FG5)

Finally, teachers stated that sometimes the needs of individual students led them to choose to stay inside. One teacher explained that without sufficient support, kids with sensory processing challenges ‘can get overstimulated and they come back in and they’re just very overwhelmed’ (FG4). Another described their efforts to ensure that students who depend on predictable structure were able to thrive. They explained that they were unable to take advantage of unscheduled opportunities to add outdoor time, because they had students who ‘need that routine more than anything so just going outside will throw off their entire day because it’s something different’ (FG4). A third echoed this, saying ‘if it’s not part of our routine it’s just, it’s more trouble than its worth because of the transition back is too hard for them’ (FG3). For these students, adding time outside to the schedule without sufficient preparation could disrupt their ability to focus for the rest of the day, resulting in lost learning time for those students. Creating a classroom environment that let them fully engage meant, at times, skipping potential outdoor opportunities for the class. These fairness and equity considerations led teachers to choose to stay inside in order to foster supportive experiences for all the students in their classes.

Theme 4: extra time for instruction and support was needed to make it work

A fourth theme that came up across focus groups was that addressing specific barriers required extra instruction. Teachers noted this in several contexts. First, while many teachers stated that transitions were a challenge due to increased disorder and lost time, they also felt that this could be addressed by developing and establishing routines for those transitions. However, teachers noted that although routines can be a powerful strategy for managing transitions, they do not happen automatically. Establishing them requires instruction and practice. Second, as described in Theme 3, teachers noted that once a classroom routine is established, students who depend on a routine need to be warned and prepared for it to change. As one teacher said,

we have to be strategic with the time that we go out to make sure it is a good time for them and that they know it’s coming so we have to prepare them for it and it’s just a lot of prep work. We do it but it’s a lot. (FG4)

Third, teachers explained that students with sensory processing disorders may need support and coaching to process the stimulating outdoor environment so they can continue to learn effectively outdoors. As one teacher said, ‘kids who have a hard time with texture laying on the grass is difficult and just the sun in their eyes is difficult so we have to get them used to that’ (FG4). Fourth, teachers and administrators noted that kids who have little experience with nature may need instruction on how to play in nature, and in a way that did not harm the environment. One principal described how students would build ‘structures and things and some of that was actually not healthy because they were trampling some plants and trees that didn’t need to be. So there’s some education that goes along with that’ (Principal). As one teacher summarized, ‘I’m not saying we can’t do it, but there’s some teaching that needs to be done’ (FG3). The extra instruction needed to make outdoor time functional for all students is real and essential work. Teaching these important pieces adds to the time and effort required to plan and implement outdoor experiences.

Theme 5: factors beyond the control of the classroom teacher limit opportunities

The final theme that emerged across barriers was that several of the factors that limited opportunities to take students outside were beyond the control of classroom teachers. These factors included the schedule for staff and instruction, content requirements, and safety policies. First, as described in Theme 2, the school-wide scheduling of staff and instruction limited time in the day when teachers could take their students outside. This schedule may be flexible, but changing it would require action from someone other than an individual classroom teacher. Second, the content required by state standards, state testing, and district requirements limited opportunities to add in ‘extra’ things. As one teacher said,

we feel the pressure for like reading and writing and math and so other things that you try and embed in, it still becomes one more thing. So at times you feel that you have more space to put it in, but at sometimes like ‘oh my god I can’t do it’ (FG1FG1).

Although the teachers in this study had a fair amount of autonomy over their instructional choices, they still had to meet state or district content requirements and did not have the authority to change that.

Third, teachers described how well-intentioned policies effectively reduced opportunities for time outside. In one focus group (FG5), teachers described policy limits based on weather conditions and potential injury. One said, ‘we aren’t allowed to go out at the very end of the day because it’s the most often time kids get hurt and the nurse needs time to tend to them’ (FG5). Another described how school safety policies created barriers to access:

accountability and all the safe school issues. Like the huge no prop doors, so the kids can’t go into the bathroom or go get a drink. You can’t just go, even though we have a nature trail right there, we can’t take them across the street and go for a 15-minute walk because it’s off school property. And that all feeds back into safe schools and accountabilities (FG6).

Discussion

The findings from this study support and expand our understanding of the barriers identified in previous work. The discussion presents four main implications for the field.

Barriers are similar to and different from previous work

Educators in this study reported experiencing a range of barriers to taking students outdoors that manifest differently for different classes. The major categories of barriers related to safety, scheduling and curriculum requirements, and lack of time and resources identified in previous literature reviews (Dillon and Dickie Citation2012; Rickinson et al. Citation2004) were also present in this context, as well as challenges related to planning for time in nature, resistance from administrators or students, a lack of appropriate outdoor spaces, compliance with school policies, and weather and clothing challenges (Dring, Lee, and Rideout Citation2020; Dyment Citation2005; Edwards-Jones, Waite, and Passy Citation2018; Oberle et al. Citation2021; Shume and Blatt Citation2019; Waite Citation2011). However, this study also identified novel barriers, particularly related to the scheduling of staff across the school, the extra instruction required to make outdoor time effective, efforts to maintain equitable instruction, and overlap of barriers as contributing to the challenges to taking students outdoors.

Many of the factors we initially believed would facilitate outdoor time in the study context—access to spaces, support from authorities in the district, motivation among the volunteer study participants, and a community culture that valued time in nature— were not mentioned as barriers as frequently as other components or as prominently as in other work (e.g. Dyment Citation2005; Edwards-Jones, Waite, and Passy Citation2018; Oberle et al. Citation2021; Shume and Blatt Citation2019). Additionally, distinct from the lack of confidence in teaching outdoors identified previously (Rickinson et al. Citation2004), teachers in this study seemed more concerned about their ability to teach well and equitably while outside. Teachers described concerns about meaningful connections to content, losing instructional time to transitions, effectively providing supports to facilitate learning for all, and making sure outdoor learning did not exclude or stigmatize students with special needs. These are more similar to the factors Rickinson et al. (2004) identified as impacting the quality, rather than the provision, of outdoor learning. In this case, however, the concerns about not being able to provide high quality instruction became the barriers to the provision of outdoor time. Rather than seeing these differences as disagreements, we suggest this indicates that barriers to outdoor learning are highly influenced by the context. While there may be categories of common challenges, the way those challenges manifest in a given setting are specific to that setting.

The parts and the sum of the barriers are both important

The nuance in the barriers described by teachers in this study suggests that identifying the specific challenges in an individual class or school could help increase the effectiveness of initiatives to increase time outside. The teachers in this study described barriers that are related to those described in previous work, but that appeared differently across schools and classrooms. For example, previous studies identified teachers’ lack of time for planning, fundraising, or managing the logistics of activities as major barriers to implementing outdoor learning (Dring, Lee, and Rideout Citation2020; Edwards-Jones, Waite, and Passy Citation2018; Rickinson et al. Citation2004; Shume and Blatt Citation2019). The current study likewise identified time-related barriers, including a shortage of time in the school day as a whole, lack of time during the day when the entire class could go outside due to the schedule of special services, the extra time needed to plan and conduct additional instruction to support outdoor learning for all students, and the loss of instructional time during transitions between indoors and out. While related, these barriers would require different actions to overcome them—a lack of time for fundraising, for example, could be addressed by hiring a fundraiser, while time lost to transitions could be addressed through practicing transition routines with a class. Interventions focusing on increasing outdoor time could benefit from examining exactly how barriers are experienced in their specific context.

While many of the barriers identified in this study seem relatively easy to overcome when considered individually, this obscures the complexity of the challenge. For example, coordinating shared spaces among groups could be addressed though a shared online calendar, or class management concerns could be addressed through pre-teaching behavioral expectations. These are relatively simple actions, and within the realm of things that regularly happen in schools. However, while the steps to address any individual barrier may be simple, simultaneously managing the multiple barriers that come up may be quite time consuming and complicated, as shown in teachers’ discussion of the courtyard in Theme 1 (see ). This appeared to be the case in the current study where, similar to Carrier et al. (2014), teachers’ and administrators’ enthusiasm for taking student outside did not enable teachers to overcome the range of barriers they encountered. Examining both the details (the parts) and the cumulative load (the sum) of the barriers may provide a better understanding of what is necessary to increase time outside.

A systems view might help increase opportunities

The findings from this study suggest that considering educators, classes, and schools as part of a dynamic system might help increase opportunities to take students outside. Systems thinking is an approach that looks at interactions between components of a system in order to better understand outcomes from the system (Midgley Citation2003). Systems thinking approaches have been widely used as a way to design interventions and improve outcomes in public health and other fields (e.g. Leischow and Milstein Citation2006; Livingood et al. Citation2011). Based on the barriers identified by educators, the education system that influences outdoor time includes: individuals including students, their families, teachers, and school or district administrators; state curriculum standards and testing; state and federal education laws; school components such as schedules, policies, and resources; physical components such as school buildings and grounds; community components such as values, beliefs, and the availability of resources; and environmental components such as plants, animals, and weather.

This and other work have identified barriers that originate from different parts of the system, and likewise need to be addressed through actions on different levels or by different individuals within the system. Oberle et al. (2021) suggested using a socio-ecological model framework for understanding the factors that impact implementation of outdoor learning. This is a valuable approach to identify factors from the various levels that impact implementation. Our suggestion of systems thinking extends this to facilitate a focus on the interactions between components in a specific context, and how those interactions impact implementation. While the socio-ecological model can expand the view to identify the factors impacting implementation, systems thinking strives to understand the network of interactions between components (within and across levels) that drive outcomes in a given context. A systems thinking approach can both complement and deepen a socio-ecological model lens, leading to increased opportunities to take students outdoors.

Systems thinking can highlight how changes ripple through a system and can facilitate the identification of leverage points to effect change. The pieces of the system are not independent such that changes to one piece can affect the rest of the system. Effecting change in a system depends on identifying the impact of proposed actions given the specific details of the components in that context. For example, a supportive administrator may allocate resources to outdoor learning spaces, which could lead to greater motivation among teachers or students to use those outdoor spaces, and result in more time spent outdoors. Alternatively, the impact could go the other direction, and extremely motivated teachers could convince a reluctant administrator to raise funds for their outdoor project. Neither of those scenarios, however, is likely to happen in a setting where there simply are no resources from which to draw. As was seen in the barriers in this study and the differences among barriers found in previous work (i.e. time and motivation (Carrier et al. Citation2014; Dring, Lee, and Rideout Citation2020; Dyment Citation2005; Edwards-Jones, Waite, and Passy Citation2018; Shume and Blatt Citation2019; Waite Citation2011)), the characteristics of the components in a system are specific to the context. Changing one component (such as resources) may have more impact in one setting than another. This suggests that educators wishing to increase outdoor time should look closely at the specific characteristics and interactions of components in their class or school in order to identify opportunities to increase outdoor time. Existing lists of barriers can provide guidance on what to look for, but the nature of the challenges and opportunities to address them are specific to individual settings. Future studies could examine interactions between supports and barriers in multiple contexts. Deeper understanding of these interactions could help to identify leverage points to increase outdoor time given the specific characteristics of a particular setting.

Equitable implementation for students with disabilities

Finally, while substantial recent work has rightfully focused on the lack of equitable access to nature for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) individuals (Ibes, Rakow, and Kim Citation2021; Pinckney et al. Citation2018), our study highlighted the need to examine equitable access for students with disabilities, particularly for work done in schools. Teachers in this study indicated that an overarching attention to equitable experiences for their students with disabilities limited their opportunities to take their classes outside through several specific barriers. Research has documented benefits of outdoor learning on academic, emotional, and behavioral development for elementary-age students with disabilities (e.g. Kuo and Faber Taylor Citation2004; Szczytko, Carrier, and Stevenson Citation2018). However, the literature on barriers to outdoor learning on elementary school grounds did not identify barriers that limited equal access for elementary-age students with disabilities. Rickinson et al. (2004) identified work that looked at barriers to provision of outdoor learning for university students with disabilities (Healey et al. Citation2001). Oberle et al. (Citation2021) identified special education services as one piece of scheduling challenges, but did not extend that to consider how this could impact participation for students with disabilities. In a context where children are required to be present, generally required to move with their class, and entitled to the least restrictive learning environment (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.), it is important to consider barriers to full participation.

Teachers in this study identified several specific barriers that impacted equitable implementation for students with disabilities. First, as described above, the schedule of special education services meant that there was not a time in the day when the entire class could go outside. Second, teachers were concerned that students with particular disabilities (physical, processing, sensory) would not be able to engage with the available outdoor experiences in the same way as students without disabilities, and thus not reap the same benefits. Third, changing the class routine to include occasional/unpredictable outdoor time could be extremely disruptive for students with particular disabilities (e.g. students on the autism spectrum (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013)). Supporting equal engagement would require arranging the schedule of services across the school to create time blocks where all students in a class could go outside, providing additional preparation or additional explicit instruction/support during activities for some students (e.g. students with sensory processing disorders; students who depend on routine), as well as planning activities that were accessible to all students.

Looking at these factors as discrete barriers does not fully explain the impact they might have on participation in outdoor learning for students with disabilities, or the work teachers need to do to facilitate equitable engagement. While these factors may occur in any classroom, the details of how they occur in a specific classroom dictate their impact on a student’s participation and the steps the teacher would need to take to address them. Managing the sum of barriers would be substantially more work than addressing any of the pieces individually. Inclusion of students with disabilities in general education classrooms is the right and equitable goal in K-12 schools (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2004). Failure to attend to these factors when planning outdoor time could succeed in enhancing learning opportunities for most of the class but fall short in providing that benefit to students with disabilities. Using a systems thinking approach to understand the network of factors that impact outdoor opportunities in a specific context could facilitate provision of targeted action and the right set of supports to enable full participation. Future work on outdoor learning opportunities in elementary schools should include examination of the factors that impact equitable provision of outdoor time for students with disabilities.

Limitations

This study provides an in-depth look at the barriers to utilizing natural spaces on schools grounds during the elementary school day at three schools in one district. The strengths and limitations are related. First, the qualitative approach and small sample allowed for a nuanced examination of the barriers in this particular context, however the results are not necessarily generalizable to other contexts. This may be particularly true for learning environments with limited natural spaces on school grounds. Second, the study was limited by potential selection bias. Recruiting volunteer participants meant that participants were likely predisposed to take students outside, and thus the data do not identify barriers experienced by educators who were not interested. Third, the self-reported qualitative data allowed for identification of multiple nuanced barriers, but did not indicate which barriers were more likely to prevent outdoor time across contexts. Future studies could examine barriers among interested and less-interested educators in other contexts; ask educators which barriers they find most limiting; and collect observational data to identify which barriers educators experience day to day.

Conclusion

Time in nature can enhance students’ wellbeing and learning, but to be successful it must be supported. Educators encounter multiple barriers to taking students outside during the elementary school day, and the details of the barriers are specific to individual classrooms. While some barriers can be addressed directly by classroom teachers, others require collaborative action and support. In order to reap the benefits from outdoor learning, educators should consider the details of discrete barriers, the cumulative effect of multiple barriers, and the impact they have on opportunities for all students. Examining opportunities and barriers as part of a dynamic system, where pieces occur simultaneously and interact, may help identify the factors that are in fact barriers in a specific context, and how they might be addressed to increase opportunities for taking students outdoors.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability and the David M. Einhorn Center for Community Engagement. The authors also wish to thank Dr. Janis Whitlock and Dr. Monika Safford for their guidance, the Cornell Master of Public Health program, and the educators in our partner district for sharing their time and expertise.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no potential competing interests connected to this work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. doi:10.1176/APPI.BOOKS.9780890425596.

- Ayotte-Beaudet, J. P., P. Potvin, H. G. Lapierre, and M. Glackin. 2017. “Teaching and Learning Science Outdoors in Schools’ Immediate Surroundings at K-12 Levels: A Meta-Synthesis.” EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 13 (8): 5343–5363. doi:10.12973/eurasia.2017.00833a.

- Blair, D. 2009. “The Child in the Garden: An Evaluative Review of the Benefits of School Gardening.” The Journal of Environmental Education 40 (2): 15–38. doi:10.3200/JOEE.40.2.15-38.

- Bratman, G. N., J. P. Hamilton, and G. C. Daily. 2012. “The Impacts of Nature Experience on Human Cognitive Function and Mental Health.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1249 (1): 118–136. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06400.x.

- Carrier, S. J., M. M. Thomson, L. P. Tugurian, and K. T. Stevenson. 2014. “Elementary Science Education in Classrooms and Outdoors: Stakeholder Views, Gender, Ethnicity, and Testing.” International Journal of Science Education 36 (13): 2195–2220. doi:10.1080/09500693.2014.917342.

- Charles, C, and R. Louv. 2009. Children’s Nature Deficit: What we know- and don’t know. Retrieved from https://assets.website-files.com/5b3406fd9a62ab41fe6f0cb6/5e25e94f451477c3fd4a13a5_childrens_nature_deficit_disorder_2009.pdf

- Chawla, L. 2009. “Growing up Green: Becoming an Agent of Care for the Natural World.” The Journal of Developmental Processes 4 (1): 6–23.

- Comstock, A. B. 1986. Handbook of Nature Study (Rev. ed.). Ithaca, NY: Comstock Publishing Associates.

- Corraliza, J. A., S. Collado, and L. Bethelmy. 2012. “Nature as a Moderator of Stress in Urban Children.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 38: 253–263. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.03.347.

- Dillon, J., and I. Dickie. 2012. Learning in the Natural Environment: Review of Social and Economic Benefits and Barriers (May), 1–48.

- Dring, C. C., S. Y. H. Lee, and C. A. Rideout. 2020. “Public School Teachers’ Perceptions of What Promotes or Hinders Their Use of Outdoor Learning Spaces.” Learning Environments Research 23 (3): 369–378. doi:10.1007/s10984-020-09310-5.

- Dyment, J. E. 2005. “Green School Grounds as Sites for Outdoor Learning: Barriers and Opportunities.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 14 (1): 28–45. doi:10.1080/09500790508668328.

- Edwards-Jones, A., S. Waite, and R. Passy. 2018. “Falling into LINE: School Strategies for Overcoming Challenges Associated with Learning in Natural Environments (LINE).” Education 3-13 46 (1): 49–63. doi:10.1080/03004279.2016.1176066.

- Evans, G. W., and P. Kim. 2007. “Childhood Poverty and Health: Cumulative Risk Exposure and Stress Dysregulation.” Psychological Science 18 (11): 953–957. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.02008.x.

- Feinstein, N. W., and D. Meshoulam. 2014. “Science for What Public? Addressing Equity in American Science Museums and Science Centers.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 51 (3): 368–394. doi:10.1002/tea.21130.

- Given, L. 2012. “The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods.” The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. doi:10.4135/9781412963909.

- Hartig, T., R. Mitchell, S. De Vries, and H. Frumkin. 2014. “Nature and Health.” Annual Review of Public Health 35: 207–228. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443.

- Healey, M., A. Jenkins, J. Leach, C. Roberts, and F. C. Hall. 2001. Issues in Providing Learning Support for Disabled Students Undertaking Fieldwork and Related Activities 65. Retrieved from http://www.glos.ac.uk/gdn/disabil/overview/index.htmhttp://www.glos.ac.uk/gdn/.

- Ibes, D. C., D. A. Rakow, and C. H. Kim. 2021. “Barriers to Nature Engagement for Youth of Color.” Children, Youth and Environments 31 (3): 49. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.31.3.0049.

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Act., Pub. L. No 2004. 1400.

- Kunkle, K. A., and M. C. Monroe. 2019. “Cultural Cognition and Climate Change Education in the U.S.: Why Consensus is Not Enough.” Environmental Education Research 25 (5): 633–655. ., doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1465893.

- Kuo, F. E., and A. Faber Taylor. 2004. “A Potential Natural Treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: Evidence from a National Study.” American Journal of Public Health 94 (9): 1580–1586. doi:10.2105/ajph.94.9.1580.

- Leischow, S. J., and B. Milstein. 2006. “Systems Thinking and Modeling for Public Health Practice.” American Journal of Public Health 96 (3): 403–405. ., doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.082842.

- Lieberman, G. a, Hoody, L. L., & Lieberman, G. M. 2000. California student assessment project-The effects of environment-based education on student achievement. State Education & Environmental Roundtable (March).

- Livingood, W. C., J. P. Allegrante, C. O. Airhihenbuwa, N. M. Clark, R. C. Windsor, M. A. Zimmerman, and L. W. Green. 2011. “Applied Social and Behavioral Science to Address Complex Health Problems.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 41 (5): 525–531. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.07.021.

- Louv, R. 2005. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder. Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

- Meredith, G. R., D. A. Rakow, E. R. B. Eldermire, C. G. Madsen, S. P. Shelley, and N. A. Sachs. 2020. “Minimum Time Dose in Nature to Positively Impact the Mental Health of College-Aged Students, and How to Measure It: A Scoping Review.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1–16. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02942.

- Midgley, G. 2003. (Ed.). Systems Thinking. London: Sage Publications.

- New York State Education Department. 2019. Parent Dashboard. Retrieved from https://data.nysed.gov/parents/

- Oberle, E., M. Zeni, F. Munday, and M. Brussoni. 2021. “Support Factors and Barriers for Outdoor Learning in Elementary Schools: A Systemic Perspective.” American Journal of Health Education 52 (5): 251–265. doi:10.1080/19325037.2021.1955232.

- Patchen, A. K. J. Hallas, B. Zhang, N. M. Wells, D. A. Rakow, J. Whitlock, … G. R. Meredith. (n.d.). Healthy Kids, Healthy Planet Outdoor Toolkit. Retrieved March 18, 2022, from https://cpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/blogs.cornell.edu/dist/d/9175/files/2020/10/HKHP-Toolkit-1.pdf

- Pinckney, H. P., C. Outley, A. Brown, and D. Theriault. 2018. “Playing While Black.” Leisure Sciences 40 (7): 675–685. doi:10.1080/01490400.2018.1534627.

- Rickinson, M. J. Dillon, K. Teamey, M. Morris, M. Y. Choi, D. Sanders, and P. Benefield. 2004. A Review On Outdoor Learning (March).

- Sahoo, K., B. Sahoo, A. K. Choudhury, N. Y. Sofi, R. Kumar, and A. S. Bhadoria. 2015. “Childhood Obesity: Causes and Consequences.” Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 4 (2): 187–192. doi:10.4103/2249-4863.154628

- Salazar, G., K. C. Rainer, L. A. Watkins, M. C. Monroe, and S. Hundemer. 2021. “2020 To 2040: Visions for the Future of Environmental Education.” Applied Environmental Education and Communication 21 (2): 182–203. doi:10.1080/1533015X.2021.2015484/SUPPL_FILE/UEEC_A_2015484_SM4619.DOCX.

- Saldaña, J. 2013. “The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers.” (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications Inc. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004.

- Shume, T. J., and E. Blatt. 2019. “A Sociocultural Investigation of Pre-Service Teachers’ Outdoor Experiences and Perceived Obstacles to Outdoor Learning.” Environmental Education Research 25 (9): 1347–1367. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1610862.

- Stevenson, R. B. 2007. “Schooling and Environmental Education: Contradictions in Purpose and Practice.” Environmental Education Research 13 (2): 139–153. doi:10.1080/13504620701295726.

- Strife, S., and L. Downey. 2009. “Childhood Development and Access to Nature.” Organization & Environment 22 (1): 99–122. doi:10.1177/1086026609333340.

- Szczytko, R., S. J. Carrier, and K. T. Stevenson. 2018. “Impacts of Outdoor Environmental Education on Teacher Reports of Attention, Behavior, and Learning Outcomes for Students with Emotional, Cognitive, and Behavioral Disabilities.” Frontiers in Education 3: 46. doi:10.3389/FEDUC.2018.00046/BIBTEX.

- Tillmann, S., D. Tobin, W. Avison, and J. Gilliland. 2018. “Mental Health Benefits of Interactions with Nature in Children and Teenagers: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 72 (10): 958–966. doi:10.1136/jech-2018-210436.

- Twenge, J. M., B. Gentile, C. N. DeWall, D. Ma, K. Lacefield, and D. R. Schurtz. 2010. “Birth Cohort Increases in Psychopathology among Young Americans, 1938-2007: A Cross-Temporal Meta-Analysis of the MMPI.” Clinical Psychology Review 30 (2): 145–154. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.005.

- U.S. Department of Education. (n.d.). Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Retrieved from https://sites.ed.gov/idea/

- United States. Public Health Service. Office of the Surgeon General. 2021. Protecting Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory. Retrieved from https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf

- Waite, S. 2010. “Losing Our Way? the Downward Path for Outdoor Learning for Children Aged 2-11 Years.” Journal of Adventure Education & Outdoor Learning 10 (2): 111–126. doi:10.1080/14729679.2010.531087.

- Waite, S. 2011. “Teaching and Learning outside the Classroom: Personal Values, Alternative Pedagogies and Standards.” Education 3-13 39 (1): 65–82. doi:10.1080/03004270903206141.

- Wells, N. M., and K. Lekies. 2006. “Nature and the Life Course: Pathways from Childhood Nature Experiences to Adult Environmentalism.” Children Youth and Environments 16 (1): 1–24.

- Wells, N. M, and K. S. Lekies. 2012. “Children and Nature: Following the Trail to Environmental Attitudes and Behavior.” In J. Dickinson & R. Bonney (Eds.), Citizen Science: public Collaboration in Environmental Research (201–213). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- White, Mathew P., Ian. Alcock, James. Grellier, Benedict W. Wheeler, Terry. Hartig, Sara L. Warber, Angie. Bone, Michael H. Depledge, and Lora E. Fleming. 2019. “Spending at Least 120 Minutes a Week in Nature is Associated with Good Health and Wellbeing.” Scientific Reports 9 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44097-3.

- Whitmee, Sarah., Andy. Haines, Chris. Beyrer, Frederick. Boltz, Anthony G. Capon, Braulio Ferreira. de Souza Dias, Alex. Ezeh, et al. 2015. “Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch: Report of the Rockefeller Foundation-Lancet Commission on Planetary Health.” Lancet (London, England) 386 (10007): 1973–2028. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60901-1.

- Williams, D. R., and P. S. Dixon. 2013. “Impact of Garden-Based Learning on Academic Outcomes in Schools.” Review of Educational Research 83 (2): 211–235. doi:10.3102/0034654313475824.