Abstract

Youth currently in secondary school will spend most of their adult life in a hotter climate associated with climate change (CC). This study investigated attitudes of youth living in an Australian Biosphere Reserve to identify their understanding of CC causes, impact, and mitigation measures, as well as their feelings of self-efficacy and hope. An online survey of 425 youth found that although participants reported a high level of understanding of impacts, they had significant knowledge gaps regarding the most effective measures to mitigate CC. In addition, youth expressed little hope that society will take action, and a lowered sense of self-efficacy. Significant gender and age differences were found for knowledge, experience, and concern about CC impacts, as well as perceptions of how well school had prepared them for navigating the impacts of CC. These findings inform communication and education interventions to mobilise youth to respond to the global climate crisis.

Introduction

Human-induced climate change (CC) is reaching a crisis point. It is already increasing land and sea temperatures and affecting weather extremes such as heatwaves, heavy precipitation, droughts, and tropical cyclones in every region across the globe (IPCC 2021). Greenhouse gas emissions (GGE) are the main cause of CC, and carbon dioxide and methane are the main contributors to greenhouse gases that cause global warming. Global warming will reach 1.5°C in the near term, and emissions must be cut significantly by 2030 to reduce (but not eliminate) the substantial further damage to human systems and ecosystems (IPCC Citation2022). While Australia produces between 1.4% and 4.8% of total global emissions (depending on whether imports and exports of carbon pollution are taken into account – ABC FactCheck Citation2020), its emissions are among the highest in the world per person and by wealth (EPA Vic Citation2011a). It ranks among the bottom ten on the CC Performance Index due to its poor policy efforts, GGE, and energy use (Germanwatch Citation2021), making it an appropriate focus for this research.

In 2021, electricity, stationary energy, and fugitive emissions combined accounted for 62.6% of Australia’s GGE, reflecting the dominant role of coal and, increasingly, liquefied natural gas (LNG; CoA Citation2021). In addition, transport accounted for 18.3% of GGE, agriculture for 15%, and waste for 2.8%. Transport’s contribution is almost entirely through emissions of carbon dioxide, whereas agriculture’s contribution is through methane and nitrous oxide – gases with global warming potentials many times that of carbon dioxide (CoA Citation2021). Parties to the Kyoto protocol can use net changes in GGE associated with land use and land use change to meet emission reduction commitments. However, these vary significantly from year to year in Australia, reflecting variability in climate and extreme events such as bushfires and drought, which lead to major loss of carbon from vegetative and soil sinks (CoA Citation2021).

Australian households generate at least one-fifth of Australia’s GGE, from transport, heating and cooling, appliances, and waste in landfill (EPA Vic Citation2011b). Individuals can lower their GGE and save money by reducing their energy, buying local, and using fewer packaged products which require more energy to produce and transport. To maximise mitigationFootnote1, interventions by governments, industry, and households need to target activities that contribute the most to GGE. However, it is unclear whether the general population, including youth, has an adequate understanding of effective actions or are willing to undertake them.

A recent poll of Australian adults found that 60% of Australians think that global warming is a serious and pressing problem and we should be taking major steps now, even if it involves significant costs (Kassam and Leser 2021). There was strong support for subsidies for renewable energy technology (91%), a net-zero emissions target for 2050 (78%), and introduction of a carbon tax or emissions trading scheme (64%). They also reported a significant gap based on age, with 78% of young adults aged 18–20 indicating that CC is a pressing problem, compared with 50% of those over 60 years of age. However, research on Australian youth perspectives and knowledge of CC is minimal. This research begins to fill this gap by examining the views of secondary school students living in the Noosa Biosphere Reserve.

Why focus on youth?

Youth will have to live with the legacy of a hotter climate so they have a right to be informed and engaged in issues that will impact their lives. Involving young people provides a means for them to add their voice to the public discourse about CC and possibly influence responses (Rooney-Varga et al. Citation2014). Today’s young people are forming their worldviews and behavioural patterns, and the cumulative effects of their lifestyle decisions and actions up to 2050 can make a significant difference in reducing GGE (Pickering et al. Citation2020). They will be tomorrow’s leaders, making decisions about transitioning to a low-carbon future to deal with environmental and societal consequences of CC (Hermans and Korhonen Citation2017; Kuthe et al. Citation2019; Sanson, Burke and Van Hoorn Citation2018).

In addition, there is evidence of widespread worry about CC among children and youth (Hickman et al. Citation2021; Clayton and Karazsia Citation2020) and a need to support and empower them with the knowledge they need to respond appropriately to these anxieties (Fielding and Head Citation2012). Globally, youth are voicing their concerns about insufficient action from governments to address CC. International events such as ‘Youth for Climate Action’, a UNICEF sponsored Summit in New York in 2019, and the school strike for climate movement inspired by Swedish activist Greta Thunberg, were opportunities for millions of youth across the world to publicly demand climate action. The School Strike 4 Climate movement, which gained momentum in Australia in late 2019, called for ‘desperate action for a dying planet’ (ABC News Citation2019). The rise of youth social action groups worldwide is an indication of young people’s concern (Sanson, Burke, and Van Hoorn Citation2018), reflecting a situation in which young people feel they have no recourse other than to self-organise to protect their interests (Whitehouse Citation2021).

Students are more likely to engage in climate action and make informed decisions when they understand the causes of CC and have knowledge of possible strategies for action (McNeill and Vaughn Citation2012), at both individual and societal levels. Research about the Australian movement found it was characterised by peer and experiential learning (in the absence of sufficient CC education in schools) and growing agency, becoming pathways for leadership development (Tattersall, Hinchliffe, and Yajman Citation2022; White et al. Citation2022; Verlief and Flynn 2022).

Seeing a need for education on CC, UNESCO (Citation2020) developed the ESD Roadmap, encouraging students to become agents of change, as they continue to have creative solutions to sustainability challenges (p32). The Roadmap draws on educational research that consistently shows empowering and mobilizing young people is vital to transformation in practice (Whitehouse Citation2021). While parental encouragement affects environmental awareness and is a predictor of pro-environment behaviour among young people, youth also play a role as informed agents of change in families and communities (Trott Citation2020). Parents and children influence one another through intergenerational learning. Additionally, children have been shown to influence parent perceptions around controversial topics (Lawson et al. Citation2019), such as gender orientation.

In general, particularly given the recent COVID 19 restrictions, there are limited opportunities for youth to express their views on the climate emergency and to feel that they have any influence on the world of their future. Many young people are increasingly discouraged about their ability to influence the future legacy that they will inherit. Li and Monroe (Citation2019) found that a sense of hope among high school students was related to their beliefs around their competency and ability to undertake actions to make a difference and be effective in addressing CC. However, indications are that young people’s understanding of CC and the most effective actions to mitigate it, are generally limited (Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020; Pickering et al. Citation2020) and highly influenced by mass media (Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020). Additionally, in spite of UNESCO’s 2010 call for CC to be part of the curricula for primary and secondary education to increase climate literacy among young people, CC is still not part of the core curriculum in most schools in Australia (Whitehouse and Larri Citation2019). Teachers could be potential change agents but they are left to their own devices in terms of resources.

This research builds on recent but limited research on youth perceptions and knowledge of CC, their sense of self-efficacy, and how they can best contribute, through a survey of youth in Noosa, Australia - an area known for its pro-environmental values.

The context – Noosa biosphere reserve

Noosa Local Government Area (LGA), with a population of 56,587, is located on the subtropical coast of South-East Queensland about a 90 min drive north of the Queensland state capital, Brisbane, Australia. It is comprised the major town of Noosa and several small towns, with almost half of the LGA land area comprised of national parks. A consistent set of values has evolved over time shaping Noosa LGA’s identity as a valued tourist destination and place to live – values about conserving natural assets, preserving visual amenity of both the built and natural environment (landscapes and seascapes), and a growing sense of community and sense of place, with an objective of achieving economic viability without substantial population growth [Baldwin and Bycroft Citation2010]. These were reflected in Noosa Council’s participation in a community-government partnership to nominate the area for UNESCO Biosphere Reserve status. Designated for the entire Noosa LGA in 2007, a Biosphere Reserve represents a commitment to enhancing the relationship between people and their environments; to understanding and managing changes and interactions between social and ecological systems. They are expected to provide local solutions to global challenges, be ‘learning places for sustainable development’, and to take action on CC (UNESCO Citation2021). Inherent in the term ‘sustainability’ is intergenerational equity, providing a driver for local youth to be involved in a CC conversation. Noosa LGA is the only Council in the State of Queensland to have declared a climate emergency, and is among 90 other municipalities that have so declared in Australia.

At the time of this study, the Council was finalising a new planning scheme, a Coastal Hazard Adaptation Strategy, and commencing development of a CC Response Plan. Though known for good community engagement practice, anecdotally staff indicated it was difficult to engage youth on CC and planning issues. The survey undertaken as part of this research was intended to provide some insight on youths’ views, guide Council’s communication on CC, and provide a basis for design of a future Youth Climate Summit. Given the Council’s environmental priorities, it was expected that youth living in the Noosa Biosphere Reserve would be fairly environmentally aware.

A core concept - motivation to act

A holistic response to CC is urgent. In order to mitigate and adapt to CC, people need to have a basic understanding of its causes and impacts. However, research has found that awareness itself is not a sufficient motivator to cause a change in behaviour (Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020). People need to be engaged in a way that is meaningful, and they need to care (Khadka et al. Citation2021).

Having an understanding of possible and effective solutions is also needed. Wynes et al. (Citation2018), for example, calculated the relative efficacy in reducing GGE of a range of individual-level actions, and identified that the most effective mitigation interventions are having few or no children, reducing air travel and vehicle usage, changing to a more plant-based diet, and switching to green energy (depending on policy setting). Further examining the Wynes et al. (Citation2018) mitigation actions in the context of Canadian youth, Pickering et al. (Citation2020) found a low level of knowledge regarding which individual level behaviours can most reduce GGE. Specifically, youth overestimated the impact of recycling on reducing GGE and underestimated the impact of having fewer children. Their findings are informed by Hermans and Korhonen (Citation2017), who found that young people are willing to take personal action to mitigate CC only if it involved a minor inconvenience, such as switching off unused electrical appliances at home, rather than reducing meat consumption, or using public rather than private transport. Other researchers suggest that solutions that are easy to do, time-efficient, save money, and can be conducted within a short timeframe may provide a pathway to greater interest, engagement, and hope in addressing CC (Fielding and Head Citation2012; Pickering et al. Citation2020).

The individual actions required to have an impact may be seen as inadequate to the scale of the issue, leading to the questioning of the effectiveness of individual agency to address CC (Gallagher and Cattelino Citation2020). The logic of the model of individual behaviour change is based on the expectation that one person’s actions will add to others to have a cumulative effect. However without a collective approach, individual actions are unlikely to ‘cohere’ together (Gallagher and Cattelino Citation2020).

The implications of CC can be quite distressing and overwhelming among both adults and youth, leading to a variety of reactions including avoidance, denial, and eco-depression (Li and Monroe Citation2019; Ojala Citation2021). The climate debate has also caused existential anxiety among young people who have grown up in a world of tension; not only about the scientific evidence vs. climate denial debate (Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020) but also between individualistic (neoliberalist) vs. community norms. This has implications regarding who, and which generation, should take responsibility for action on environmental sustainability including on CC. As a result, CC has become a source of anxiety and pessimism about the future of the planet amongst youth (Ojala Citation2012). Ojala (Citation2015a) has suggested that a distrust in institutions, low interest in societal issues, and the belief that one cannot personally influence environmental issues have contributed to climate scepticism and a feeling of societal powerlessness. More recently, Hickman et al. (Citation2021) found that over 50% of their international sample of 10,000 young people (aged 16–25 years) felt sad, anxious, angry, powerless, helpless, and guilty in relation to CC. They attributed this to the failure of governments to take action, resulting in impact on younger generations and thus constituting moral injury.

Schools and family need to support students so they can respond adaptively to anxieties (Sanson, Burke, and Van Hoorn Citation2018). Teachers need to acknowledge the emotional stress and communicate in a positive, solution-oriented way to generate hope (Ojala Citation2015b). Hope is based on students’ belief that they and society can undertake actions to be effective and make a difference (Li and Monroe Citation2019). They need to be acknowledged as CC actors, rather than victims.

Motivation to act is in turn affected by a sense of self-efficacy, which is the belief that our actions can bring about positive outcomes. A related term, sense of agency, is also used to describe the experience of being in control of both one’s own actions and, through them, of events in the external world (Haggard and Tsakiris Citation2009). In addition to self-efficacy and agency, a person’s belief that they have control or influence over the outcomes of events in their lives (i.e. internal locus of control; Rotter Citation1966), as opposed to external influences beyond their control, is also a critical factor influencing whether or not individuals will take action. These perceptions are themselves affected by social norms (Busch et al. Citation2019), knowledge, and prior positive experiences with taking action. Indeed, Littrell et al. (Citation2020) found that an interactive program with youth about CC that gave them a better understanding of the causes and consequences of CC led to a stronger sense of both collective and personal responsibility to take action to address CC challenges in their communities. It promoted greater ‘hope, agency, and engagement around CC rather than despair, overwhelm and withdrawal’ (Ibid: 607). Young people’s visions of the future reflect their perceptions of society’s ability to address current problems and of their own power to effect the changes they wish to see (Gallagher and Cattelino Citation2020).

A further concept, collective efficacy, contributes to motivation to take action. Collective efficacy is defined as a group of ‘people’s shared beliefs in their collective power to produce desired results’ (Bandura Citation2000, 75 in Busch et al. Citation2019, 2393). When considering collective global environmental problems such as CC, individual actions are unlikely to make a big difference unless large numbers of people act together (Busch et al. Citation2019). But without connection to a political process with strong leadership on CC mitigation, collective action is unlikely to take place (Gallagher and Cattelino Citation2020).

Youth have few opportunities to share their understanding and concerns about CC within their communities (Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020). Trott’s (Citation2020) study in the USA reported that the most popular sources of CC information for teens, beyond school, is the Internet. Formal education on CC varies widely around the world with some countries including it in the secondary school curriculum while in others, teachers express uncertainty about the science and how to deal with potential controversy (Kunkle and Monroe Citation2019). Pickering et al. (Citation2020) found that the knowledge of the relative efficacy of GGE-reducing actions was generally poor. Likewise, Wynes and Nicholas (Citation2017) found that Canadian high school textbook content for GGE reduction behaviours largely failed to mention high-impact actions, which accounted for just 4% of recommended actions, and instead focused on incremental changes that would yield much smaller potential emission reductions. In most cases, the most effective strategies for mitigation are not included in educational materials (Ibid).

As a result, this exploratory study aimed to identify the knowledge, perceptions, behaviour and sense of self-efficacy about CC issues and solutions by youthFootnote2 in the Noosa Biosphere Reserve area, as a precursor to engaging them in developing climate actions.

Methods

An online survey directed at young people in secondary school in Noosa Council area was used to identify their understanding of causes, impacts and mitigation of CC, level of concern, and sense of agency between February and May 2021. The survey was administered using Qualtrics, with a link circulated via (i) a direct approach by the principal researcher to the heads of the nine secondary schools in the district, (ii) the Noosa Youth Advocacy Group (NYAG) members, who are high school students with an interest in environmental sustainability, and (iii) school contacts of the Noosa Environmental Hub (a local NGO that supports a range of projects, including NYAG). An estimated 5000 young people between the ages of 11 and 18 live in the Noosa Council area (ABS Citation2021), although some of these students may attend schools outside of the Noosa LGA or have left school, and some students living outside the LGA may attend schools inside the boundaries. Completed responses for analysis purposes were 425 by the closing date, with responses varying per question from 309 to 425 responses.

Survey measures

Survey questions were derived from the literature (see Appendix A for an abbreviated list of questions) and revised after pilot testing with NYAG members to maximise clarity. The 26 questions were mainly comprised of five-point Likert scale questions, as well as two open-ended questions, and took approximately 15 min to complete. Ethics approval was granted by the University of the Sunshine Coast Human Ethics research panel # A211540. Responses were anonymous, and participants provided informed consent.

Data analysis

The quantitative data were analysed using a variety of statistical techniques (see below) including paired-samples t-tests, one-way ANOVA with Scheffe post-hoc tests, and chi-squared analyses (as appropriate) using IBM® SPSS Statistics (Armonk, NY). The open-answer question on mitigation actions were analysed using an inductive coding approach that closely mirrored the categories identified in Pickering et al. (Citation2020). For all analyses based on gender, only those who identified as female or male were included, as the number of respondents identifying otherwise was very small (n = 21).

Results

Demographics

Of the 425 respondents, 243 identified as female (57%), 161 identified as male (38%), and 21 respondents did not disclose their gender (5%). The mean participant age was 14.1 (SD = 1.6) years, with ages ranging from 11 to 18. Students were fairly evenly split among the grades (grade 7 = 51; grade 8 = 148; grade 9 = 51; grade 10 = 78; grade 11 = 53; grade 12 = 41; ‘other’ = 4), although approximately a third of respondents were in grade 8. With the exception of a small number from two state public secondary schools, most of the respondents attended private schools.

Climate change knowledge, beliefs, and experiences

Belief in climate change/anthropogenic cause

The majority of participants (85%) indicated the belief that the global climate is changing, and 68% indicated that it was completely or mainly human-caused (just 4% indicated that the climate is not changing, and only 3% that the cause of CC is unrelated to human involvement). This is consistent with Pickering et al. (Citation2020) data on Canadian youth which illustrated that the majority of youth believe in the severity and impact of CC. A chi-square analysis showed that females were more likely to report that they believe in CC as compared to males, χ2 (2403) = 17.32 p < .001, although there were no gender differences with respect to belief in the anthropogenic contributions to CC.

Contributors to climate change

The majority of respondents accurately identified fossil fuels for transport and electricity (59%) and deforestation (59%) as major contributors to CC. However, a similar percentage (59%) incorrectly identified waste pollution as a major contributor to CC, and 42% incorrectly identify ozone layer hole as a major contributor. Interestingly, only 1 in 6 of respondents (17%) identified grazing animals as a major CC contributor, suggesting a significant knowledge gap on the negative impacts of grazing livestock, but also a disconnect between proximal (deforestation) and distal (gazing livestock) causes of anthropogenic CC. Interestingly, females were more likely than males to identify each of the eight possible contributing factors as “major contributors” (all F’s > 6.5; all p’s < .01), with effect sizes ranging from 0.02 (volcanos) to 0.09 (waste pollution).

Impacts of climate change

The vast majority of respondents (90–95%) accurately identified rising sea levels, hotter temperatures, melting glaciers, animal extinction, warmer oceans, and severe weather as possible impacts of CC, demonstrating sound knowledge of the impacts of CC at the macroscale. As with the CC contributors question, females were more likely than males to identify each of the 10 possible factors as a potential impact of CC, with the exception of hotter temperatures, glaciers melting, and animal extinction, where the two groups did not differ (all F’s > 3.2; all p’s < .04). Interestingly, 46% of these students also incorrectly identified earthquakes as a potential impact of CC, and 13% indicated that COVID-19 was a potential impact.

Personal experiences with climate change

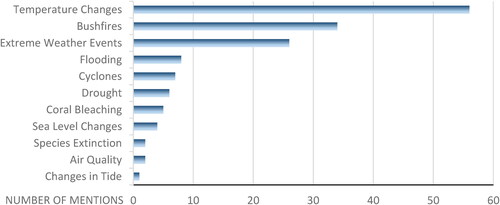

Approximately 29% of participants indicated that they had personally experienced the negative effects of CC, whereas 48% indicated that they were ‘unsure’ and 22% indicated that they had no experiences. A one-way ANOVA with a Scheffe post-hoc test revealed that older participants were more likely to report personally experiencing the negative effects of CC, F(4,398) = 5.43, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.05, such that a greater proportion of 15+ year-olds reported that they experienced the effects of CC as compared to individuals aged 14 or younger (all p’s < .001). In addition, females were more likely than males to indicate that they had personally experienced the effects of CC, F(1398) = 15.83, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.04. Of those participants who indicated that they had experienced the effects of CC, 55% reported experiencing higher temperatures, 35% experienced bushfires, and 25% experienced extreme weather events (see ).

Climate change mitigation

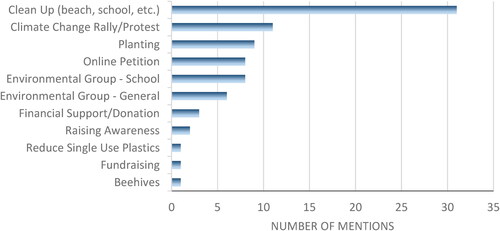

Reduced use of fossil fuels was correctly identified (directly and indirectly – in transport, electricity or unspecified) as an effective individual-level action for reducing GGE (see ). While the impact of recycling and reuse, which together reduce Australia’s GGE by just 2.8% (CoA Citation2021), were overestimated by the respondents, the effect of reducing meat consumption was underestimated (11%), despite the fact that methane from grazing animals is a major contributor to warming the environment. Having no or fewer children was not identified at all as a mitigation action, despite the literature indicating that it is the single most impactful individual-level behavior in reducing GGE (Wynes et al. Citation2018). In the Pickering et al. (Citation2020) findings on Canadian youth’s identification of mitigation measures, recycling/reducing waste was likewise overrepresented, plant-based diets had a similarly low mention (10%), and having fewer children was not mentioned at all.

Table 1. Individual actions for mitigating climate change cited by respondents (N = 264).

The most frequently cited actions that government could take to reduce GGE were measures to invest/transition to renewable energy and reduce use of fossil fuels (63%). Actions in these categories included: encourage reduction of vehicle use; subsidize electric cars and public transport; introduce a carbon tax, buy local, and use green energy. The next most frequent mentions also accurately identified government roles to educate the public, enact and enforce laws, develop polices, guidelines and incentives, and invest in research and innovative technologies (43%). Land use actions and waste reduction were also mentioned.

Climate change information

Sources of information

TV news was rated as the most common source of information on CC (M = 3.13; SD = 1.33), followed by school (M = 3.07; SD = 1.16), social media (M = 2.88; SD = 1.37), online streaming (M = 2.70; SD = 1.19), family (M = 2.65; SD = 1.21), online news (M = 2.47; SD = 1.37), podcasts/radio (M = 2.22; SD = 1.14), friends (M = 2.16; SD = 1.03), and books (M = 2.14; SD = 1.13). This somewhat contrasts with studies in Canada where television was ranked as the sixth most accessed source among youth, but the highest among adults (Pickering et al. Citation2020; Morris and Pickering Citation2019). Females were more likely than males to get their information about CC from the following sources: social media, online news sites, podcasts/radio, and books (all p’s < .05).

Scientists were considered the most trustworthy sources of information on CC (M = 4.51; SD = 0.93), followed by school (M = 4.02; SD = 1.12), family (M = 3.47; SD = 1.15), government (M = 3.45; SD = 1.38), friends (M = 2.66; SD = 1.02), and social media (M = 2.40; SD = 1.08). Females rated scientists as more trustworthy than did males, F(1361) = 18.26, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.05, and the older group (16+) rated their family as a significantly less trustworthy source than did individuals aged 14 and under, F(4359) = 4.74, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.05.

With respect to whether CC was adequately taught in school, over two-thirds of respondents indicated that they were adequately educated on CC impacts (69%), whereas climate science (59%), adaptation (57%), and mitigation (51%) were less well taught. Interestingly, females were more likely to report that adaptation (χ2 (1310) = 7.97, p = .01) and mitigation (χ2 (1295) = 3.80, p = .05) are not adequately taught in school. Similarly, older individuals (age 16+) are more likely to report that adaptation (χ2 (4308) = 11.83, p = .02) and mitigation (χ2 (4294) = 13.00 p = .01) are not adequately taught in school, as compared to younger individuals (age 11–12).

Discussing climate change

Although the respondents in this study had a fairly decent grasp of the effects and impacts of CC, they did not frequently discuss CC with others. Indeed, only 1 in 6 respondents reported that they discuss CC often or much of the time, whereas 42% reported that they rarely or never discuss CC. Females were more likely than males to discuss CC with others, F(1363) = 10.66, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.03. Parents, friends, and teachers (in descending order) were the most frequently cited discussants. This is important because peer-to-peer exchange is crucial in spreading the message about the threats of CC, and possible mitigation strategies.

Worry and hope

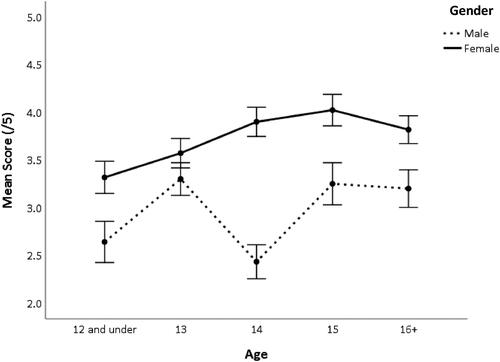

Approximately 52% of respondents indicated that they were ‘concerned’ or ‘very concerned’ about the effects of CC, with females reporting significantly greater concern than males, F(1394) = 45.36, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.11. Responses also varied as a function of age, such that older individuals indicated that they were more worried about the effects of CC than did younger individuals, F(4394) = 4.09, p = .003, ηp2 = 0.04. There was also a significant gender by age interaction, such that the difference in concern between males and females was more pronounced in older individuals, F(4394) = 3.51, p = .008, ηp2 = 0.04, although this interaction was largely driven by a lack of difference between 13-year-old males and females and a large difference between 14-year-old males and females (see ).

Figure 2. Climate change worry as a function of gender and age. Bars represent the standard error for each condition mean.

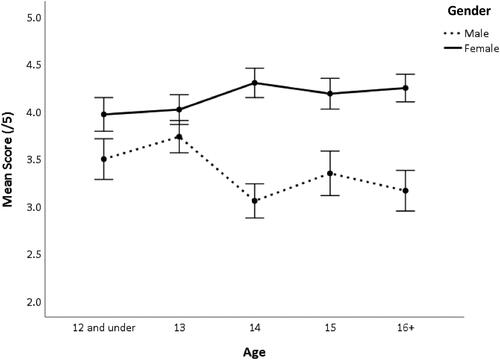

Participants reported significantly greater concern for the environment in general than for CC specifically, t(360) = −8.38, p < .001, d = 0.35, with approximately 66% of participants indicating that they were ‘concerned’ or ‘very concerned’ with protecting the environment. As with CC concern, responses varied as a function of gender, F(1360) = 45.76, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.12, such that females reported greater concern over protecting the environment, and there was a significant gender by age interaction, such that the difference in concern between males and females was more pronounced in older individuals, F(4360) = 2.76, p = .03, ηp2 = 0.03 (see ).

Figure 3. Concern for protecting the environment as a function of gender and age. Bars represent the standard error for each condition mean.

The vast majority of participants indicated that CC will have significant negative impact on Australia as a whole (63%) and on future generations (87%), with females indicating a greater perceived impact for both Australia as a whole, F(1396) = 30.44, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.07, and for future generations, F(1396) = 33.12, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.08. Beliefs about the impact of CC on future generations also differed as a function of age, F(4396) = 2.63, p = .03, ηp2 = 0.03, such that older respondents indicated a stronger impact. Although participants indicated that CC would have significant negative effects, surprisingly few indicated that CC would affect them personally (33%). Beliefs about personal impacts differed as a function of both gender, F(1395) = 14.31, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.04, and age, F(4395) = 3.51, p = .01, ηp2 = 0.04, such that females and older individuals indicated a greater personal impact.

Although the majority of respondents are concerned about the effects of CC, they are equivocal about being hopeful that society can reverse CC trends. The majority of responses clustered around the mid-point (i.e. half-way between ‘Little hope’ and ‘I’m convinced we can’), revealing some uncertainty, with 8% expressing very little hope and 7% believing that society can reverse the trend, with similar parity between the lowest two categories (32.4%), and the highest two categories (30.1%).

Self-efficacy and action

In relation to a series of questions to measure self-efficacy, responses were neutral to low for individual efficacy (M = 3.21; SD = 0.97) but stronger for collective efficacy (M = 3.82; SD = 1.02). Only 15% of respondents indicated that they were ‘prepared, informed and capable’ of taking action on CC. Both collective-efficacy (F(2350) = 27.73, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.16), and self-efficacy (F(2350) = 35.21, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.20) differed as a function of whether or not participants had engaged, or planned to engage, in group action. That is, individuals who indicated that they did not engage in action nor intend to in the future had significantly lower collective and self-efficacy scores (all p’s < .001) than those individuals who were either already engaged in collective action, or who intended to engage in the future.

Approximately 28% of respondents reported that they are currently engaging in group action to raise awareness or promote change in the environment, and 47% plan to in the future (24.9% do not intend to engage in group action). Of those who engaged, 91.3% said it was a positive experience. Beach, school and other clean-ups were by far the most popular group action with CC rally/protest being the next most frequently cited recent example (see ). Females were more likely to participate in group action on the environment, χ2 (2361) = 32.76, p < .001, and were also more likely to both give encouragement to act F(1353) = 19.48, p <.001, ηp2 = 0.05, and receive it, F(1350) = 10.99, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.03.

In order to examine potential predictors of youth engagement in pro-environmental action, we conducted a logistic multinomial regression (see ). Logistic multinomial regression enables us to examine the drivers of both action (‘yes’) and inaction (technically called precontemplation; ‘No, and I do not expect to participate in the future’) independently relative to the change group (“No, but I intend to in the future”) following the approach of Tobler, Visschers, and Siegrist (Citation2011) and Pickering, Schoen, and Botta (Citation2021). Interestingly, none of the variables predicted being in the action stage for participation in group action, although respondents who believe in CC were more likely to be in the action stage compared to those who did not or were not sure.

Table 2. Multinomial regression for participation in group action on environmental issues, with standardized β-values (β), standard errors (SEs), odds ratios (ORs), and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

In contrast, four factors predicted being in the inaction (precontemplation) stage. Specifically, youth were more likely to be in the precontemplation (inaction) stage if they were male, had lower environmental concern, received less encouragement from other individuals to engage in environmentally-friendly behaviours, and had lower belief that their actions can help mitigate CC. Interestingly, only one of these predictors directly references CC, suggesting that on the whole CC beliefs and attitudes are not closely tied to the action stage with respect to participation in group action around “an environmental issue”. This makes sense, as young participants are more likely to participate in something that is already organised, like the annual beach clean-up.

Discussion

This study extends the literature in a number of important ways. We discuss the implications of the research findings about Noosa youth’s understanding and source of information on CC, their perceptions of trust in that information, and feelings of self-efficacy. We emphasise the need to include CC science, particularly mitigation and adaptation, in the school curriculum.

Understanding and knowledge of climate change

While youth generally had good knowledge of the impacts of CC and certain GGE-reducing actions such as reducing fossil fuel use and deforestation, there was a clear gap in their knowledge of individual mitigation options as evidenced by the fact that participants rated recycling as a more effective action and adopting a plant-based diet as a less effective action to mitigate GGE. This reflected their lack of recognition of the significant contribution of grazing and general agriculture to GGE (CoA Citation2021), and their over-estimation of waste as a contributor to GGE, which also emerged in Pickering, Schoen, and Botta (Citation2021). One explanation for these findings may be that recycling is a behaviour over which youth have a fair amount of control, awareness, and support. For instance, they can dispose of plastics, glass, and paper in home, school, and public recycling bins, and Australia has long had strong anti-litter and ‘clean-up’ campaigns. Many of the students (49%) reported participation in ‘Clean Up Australia Day’, school, and beach clean-ups, where litter is separated, weighed and reported, thus the emphasis on clean-up activities may have increased their perceived importance of reducing waste.

Given the contribution from agriculture, including grazing, to methane and nitrous oxide – gases with global warming potentials many times that of carbon dioxide (IPCC 2007) and targeted for reduction in the Global Methane Pledge at COP26 (UN Climate Change Citation2021), individual youth can also play a role by reducing meat in their diet and encouraging the same within their families. Education for the entire family may be needed about growth-stage appropriate nutrition for meat-avoiding/reducing active teenagers.

This lack of knowledge of personal mitigation options is similar to other studies overseas (Wynes et al. Citation2018; Wynes and Nicholas Citation2019; Pickering et al. Citation2020). Wynes and Nicholas (Citation2017) point out that in Canada, education and government documents do not focus on high-impact actions for reducing emissions, such as having one fewer child, living car-free, avoiding airplane travel, and eating a plant-based diet. Rather, recycling (four times less effective than a plant-based diet) or changing household light bulbs (eight times less) are commonly promoted.

Will knowledge alone translate into individual youth taking action? In terms of reducing fossil fuel use for travel, though school buses are prevalent in the sprawling Noosa regional area, alternatives to private transport are limited. For instance, public transport is inefficient (particularly for students involved in extracurricular activities), and bicycle paths or lanes separated from motorised traffic are uncommon, thus bicycling is not generally safe. As in North America, youth have aspirations of gaining a drivers licence and car ownership, as well as travelling overseas. To date, feasibility of widespread use of electric vehicles in Australia is challenged by high capital cost compared to internal combustion engine vehicles, and constrained driving range due to limited charging infrastructure and vehicle capacity (Greaves, Backman, and Ellison Citation2014), although this is improving. In comparison to transport (18.3%), electricity is the highest contributor to GGE in Australia, accounting for 32.9% of Australia’s emissions, mainly from coal-fired and increasingly gas-generated electricity (CoA Citation2021). Mitigating these emissions requires government and corporate willingness to change, which optimistically could be influenced by public pressure.

Information sources and education

Another explanation for the lower level of understanding of GGE mitigation measures, as compared to impacts of CC, is the emphasis on impacts of disasters such as floods in Queensland and recent catastrophic bushfires in southern Australia, on TV, social media and, as reported by the students in this study, in the education system. In addition, Bacon (Citation2013:1) found that Australia’s concentrated newspaper ownership has a significant effect on how climate science is covered, with one-third of articles in Australia’s major newspapers not accepting the consensus position of climate science: that human beings are contributing to CC – the logical conclusion being that mitigation measures will not make a difference. Times could be changing, though, with a review of the 2019–2020 bushfires in Australia clearly attributing the hot dry preceding conditions to CC (CSIRO 2020). Additionally, a rather large portion of the respondents (33%) reported that they had direct experience with bushfires/wildfires in the Noosa area, thus natural disasters are particularly tangible and relevant to many of the respondents. Indeed, thousands of people in Noosa LGA were evacuated in 2019 due to various bushfires; a rarity in the normally humid sub-tropical Noosa area. Many young people in the Noosa area would also be aware of the preceding hot dry conditions that increased bushfire risk.

The relatively low scores for effective teaching of mitigation measures are consistent with calls for improved nation-wide curriculum on CC mitigation and adaptation over the years (Whitehouse and Larri Citation2019; Fielding and Head Citation2012). The issue reached a low point in 2019 as Australia’s education Ministers launched the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Education Declaration, removing all references to CC and integrating sustainability across the curriculum. As a result, CC education is left to school leaders and teachers, who themselves may not be knowledgeable about the topic, or supported in its teaching (Purves Citation2021). A similar concern was raised by Wynes and Nicholas (Citation2017:12) in Canada, who reported a lack of focus on high-impact actions for reducing emissions in their thorough assessment of secondary school curricula. They pointed out that textbooks and curricula might cause students to doubt the ‘very robust existing consensus in the scientific community’. Given the trust in scientists revealed in our survey results, a revised Australian secondary school curriculum could include more about this scientific consensus and refer to scientists in explanations about the most effective mitigation measures. This might improve trust in the education system as a source of information by youth. Not only does the curriculum need to be addressed, a priority action of the ESD Roadmap (UNESCO Citation2020) is to build the capacity of educators, who ‘themselves need to be empowered and equipped with the knowledge, skills, values and behaviours that are required for the transition’ (p30).

The low profile of mitigation could also be attributed to the minimal attention paid to mitigation in government policy at federal, state, and local levels to date. For example, although the Queensland state government has a Queensland Strategy for Disaster Resilience 2017, a Climate Adaptation Strategy, several Sector Adaptation Plans (e.g. for agriculture, health and built environment sectors), and has sponsored local governments to prepare Coastal Adaptation Plans, to date, none mention mitigation measures to reduce GGE or additional policies to mitigate GGE.

Agency, self-efficacy, and hope

Based on the fact that world-wide action is needed to mitigate GGE, and the importance of collective efficacy in achieving that goal, we asked students to rate effectiveness of collective action and action by government, as well as their belief in the efficacy of individual action. They reported little confidence that government would adequately address CC. Indeed, Hickman et al. (Citation2021) found that climate anxiety and distress are significantly related to perceived inadequate government response.

Of interest was the strong relationship that emerged between both collective and individual efficacy, and engagement in group action. The low current engagement in environmental action (28%) may be due to a lack of self-efficacy and lack of agency among these students.

Education can increase a sense of self-efficacy among high school students who better understand the causes of CC and what actions are necessary to mitigate heat-increasing GGE. With knowledge, youth sense of agency should increase and they may be more likely to engage in climate mitigation (McNeill and Vaughn Citation2012). In this study, however, only 51% of respondents thought that mitigation was adequately taught in school, and only 15% felt they were ‘prepared, informed and capable’ of taking action on CC, reinforcing the need to improve teaching of mitigation measures. Information alone will not necessarily cause behaviour change however; perceived efficacy of one’s actions is also needed (Fielding and Head Citation2012).

Introducing students to higher impact actions early in life allows them to integrate these actions into their lifestyle (Pickering et al. Citation2020). Empowering youth to adopt high-impact actions may decrease youth anxiety about the future and CC in particular (Clayton and Karazsia Citation2020). However Nairn’s study (2019) of youth in New Zealand, suggests that despair and hope might be related to both collective and individual processes. In addition, youth could use their influence on their parental attitudes to encourage adoption of mitigation measures by families, such as food choices, installing solar panels, and transitioning to energy-efficient cars (Lawson et al. Citation2019). Youth can also have influence on governments at all levels, by meeting with elected representatives, writing letters, and voicing their concerns in the media about mitigation.

Gender and age differentiation

Of interest was the difference between gender, and with age. Consistent with other, primarily adult research (Arcury and Christianson Citation1990; Blaikie Citation1992; Mainieri et al. 1997; McCright Citation2010), females reported significantly greater concern for the environment, and females typically engage in more pro-environmental activity (e.g. Diamantopoulos et al. Citation2003; Fielding and Head Citation2012; Hunter, Hatch, and Johnson Citation2004; Pickering et al. Citation2022; Tindall, Davies, and Mauboulès Citation2003). Semenza et al. (Citation2008) found a greater concern by women about CC compared to men, while Linden (Citation2015) found that gender and political orientation were significant and consistent predictors of both personal and societal risk perceptions of CC (p121). We also found that the difference in concern between males and females was more pronounced in older individuals. In our study, there appeared to be an age, between approximately 13−14 years, at which males and females begin to diverge in terms of concern for the environment, with males becoming less concerned as they age.

Females rated scientists as more trustworthy than did males, and the older group (16+) rated their family as a significantly less trustworthy source than did individuals aged 14 and under. Females were more likely than males to discuss CC with others and were also less likely to agree that mitigation and adaptation were adequately taught in school, as were older students.

An explanation of why gender does make such a difference across a wide range of environment-related beliefs is not clear from the literature and should be a priority in further research. McCright (Citation2010) reports that the gender divide is not accounted for by differences in key values and beliefs or in the social roles that men and women differentially perform in society. The potential role of empathy is one area worthy of more investigation, given that it varies with gender (Eisenberg and Lennon Citation1983), yet – at least in the case of empathy for the environment – may be facilitated by relatively simple interventions (e.g. Schultz Citation2000; Blythe et al. Citation2021).

Like Fielding and Head (Citation2012), females were also more likely to engage in action and environmentally friendly behaviours. This latter finding is not unexpected under the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen Citation1991), which postulates that behavioural intent is shaped by attitude towards the behaviour, perceived control over the behaviour, and subjective norms. Males in our study were less likely than females to believe in CC, and reported less concern about it and protecting the environment more generally. Thus, these attitudinal factors can be expected to reduce intent to undertake pro-environmental action, and may be mediated by lower risk perception in males (Linden, Citation2015).

In summary, it should be of concern to government, educators and parents, that these Australian young people (aged 11–18), living in a Biosphere Reserve, in general, lack hope that society can reduce GGE sufficiently to reverse CC trends. It extends Sanson, Burke, and Van Hoorn (Citation2018) findings of evidence of widespread worry about CC among children and youth, and their need for support and empowerment to respond adaptively to these anxieties. Parents and educators can actively contribute by engaging with the issue themselves and communicating strategies.

The challenge is in making the link between actions and outcomes and instilling amongst youth a sense that it is not just their responsibility but the responsibility of communities in general to take action. Providing stories about young people’s actions and how they make a difference and influence the broader community as well as government policy should be a priority.

There is a need for a review of Australian curriculum to include broader information, but also to engage more participatory, creative, and empowering approaches to CC education, in order to motivate youth towards action. It should focus on meaningful and relevant information; use active and engaging teaching methods including deliberative methods; interaction with scientists; addressing misconceptions; and implementing school or community projects (Monroe et al. Citation2019; Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles Citation2020). Place-based engagement can also connect localised impacts of CC within a systems approach that reveals how impacts are connected to decision-making and behavioural choices (Schweizer, Davis, and Thompson Citation2013).

Limitations

In common with questionnaires similarly made available online, respondents self-selected to respond on this topic, possibly resulting in a pro-environment or CC biased sample. Since environment and sustainability have a high profile locally through the Biosphere Reserve designation and amount of land under conservation in the LGA, respondents might have been expected to have high environmental interest and action. This did not necessarily appear to be the case (e.g. 65% of respondents indicated that they were concerned about protecting the environment, yet only 28% have actively participated in a pro-environmental initiative), although we know of no other recent similar studies on Australian youth for comparison.

Our choice of measures in this study was largely informed by their prior use in published research and by keeping the survey length manageable to increase completion rates and data quality. An expanded set of questions may have provided greater insight into particular aspects, such as self-efficacy.

Conclusions

In a Biosphere Reserve community that is generally considered environmentally aware and committed, these responses by students aged 11–18 must provoke reflection on how CC is communicated in the Australian education system, media, and government policy, and why so few of our participants felt ‘prepared, informed and capable’ of taking action on CC. Broader understanding of the interventions that promote both individual and collective efficacy are essential to engaging youth in adopting a low-carbon lifestyle early enough to have long-term benefits and lead to lower net emissions.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of Dalia Mikhail of Noosa Environmental Education Hub and students in the Noosa Environmental Advocacy Group for facilitating circulation of the survey link and pilot testing the survey. We appreciate the time and effort of all the students who completed the online survey. We also acknowledge the support of Hannah Pickering for formatting the survey on Qualtrics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Mitigation action in this study is defined as action which reduces GGE.

2 ‘Youth’ are generally defined as those aged 12–24. Our respondents fall within this category, although we had a few aged 11 also respond.

References

- ABC FactCheck. 2020. “Do Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions account for more than 5 per cent of the global total once exports are included, as Mike Cannon-Brookes says?” Accessed 29 June 22. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-11-20/fact-check-australia-carbon-emissions-fossil-fuel-exports/11645670

- ABS. 2021. “Schools 2021.” Australian Bureau of Statistics. Accessed 2 February 2022. abs.gov.au

- Ajzen, I. 1991. “The Theory of Planned Behavior.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50 (2): 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

- Arcury, T. A., and E. H. Christianson. 1990. “Environmental Worldview in Response to Environmental Problems: Kentucky 1984 and 1988 Compared.” Environment and Behavior 22 (3): 387–407. doi:10.1177/0013916590223004.

- Bacon, W. 2013. “Big Australia media reject climate science.” The Conversation, Accessed 24 February 2022, from Big Australian media reject climate science. theconversation.com

- Baldwin, C, and P. Bycroft. 2010. “Governance Options for Maintaining Values in Times of Change.” Proceedings of People and the Sea V: ‘Living with uncertainty and adapting to change’. Amsterdam: Centre for Maritime Research (MARE) 9 - 11 July 2009, p 1–31.

- Bandura, A. 2000. “Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 9(3): 75–78.

- Blaikie, N. W. 1992. “The Nature and Origins of Ecological World Views: An Australian Study.” Social Science Quarterly 73 (1): 144–165. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44656060

- Blythe, J., J. Baird, N. Bennett, G. Dale, K. L. Nash, G. J. Pickering, and C. C. C. Wabnitz. 2021. “Fostering Ocean Empathy through Future Scenarios.” People and Nature 3 (6): 1284–1296. doi:10.1002/pan3.10253.

- Busch, K., N. Ardoin, D. Gruehn, and K. Stevenson. 2019. “Exploring a Theoretical Model of Climate Change Action for Youth.” International Journal of Science Education 41 (17): 2389–2409. doi:10.1080/09500693.2019.1680903.

- Clayton, S, and B. Karazsia. 2020. “Development and Validation of a Measure of Climate Change Anxiety.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 69: 101434. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101434.

- CoA (Dept of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources). 2021. “Quarterly update of Australia’s national greenhouse gas inventory. Accessed June 2021. https://www.industry.gov.au/data-and-publications/national-greenhouse-gas-inventory-quarterly-update-june-2021

- CSIRO. 2020. “Climate and disaster resilience.” Accessed 24 February 22. CSIRO-Report-Climate-and-Disaster-Resilience-Overview.pdf

- Diamantopoulos, A., B. B. Schlegelmilch, R. R. Sinkovics, and G. M. Bohlen. 2003. “Can Socio-Demographics Still Play a Role in Profiling Green Consumers? A Review of the Evidence and an Empirical Investigation.” Journal of Business Research 56 (6): 465–480. doi:10.1016/S0148-2963(01)00241-7.

- Eisenberg, N., and R. Lennon. 1983. “Sex Differences in Empathy and Related Capacities.” Psychological Bulletin 94 (1): 100–131. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.94.1.100.

- EPA Vic (Environmental Protection Authority Victoria). 2011a. “Greenhouse gas emissions in Australia.” Australian Greenhouse Calculator. Accessed 1 Sepetember 2021. https://apps.epa.vic.gov.au/AGC/r_emissions.html#/!

- EPA Vic (Environmental Protection Authority Victoria). 2011b. “Households and greenhouse gas emissions.” Australian Greenhouse Calculator. Accessed 1 Sepetember 2021. https://apps.epa.vic.gov.au/AGC/r_emissions.html#/!

- Fielding, K., and B. W. Head. 2012. “Determinants of Young Australians’ Environmental Actions: The Role of Responsibility Attributions, Locus of Control, Knowledge and Attitudes.” Environmental Education Research 18 (2): 171–186. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2011.592936.

- Gallagher, M., and J. Cattelino. 2020. “Youth, Climate Change and Visions of the Future in Miami.” Local Environment 25 (4): 290–304. doi:10.1080/13549839.2020.1744116.

- Germanwatch. 2021. “Australia.” Climate Change Performance Index. Accessed 1 Sepetember 2021. https://ccpi.org/country/aus/

- Greaves, S., H. Backman, and A. B. Ellison. 2014. “An Empirical Assessment of the Feasibility of Battery Electric Vehicles for Day-to Day Driving.” Transportation Research Part A: Policy and Practice 66: 226–237. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2014.05.011.

- Haggard, P., and M. Tsakiris. 2009. “The Experience of Agency: Feelings, Judgments, and Responsibility.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 18 (4): 242–246. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01644.x.

- Hermans, M., and J. Korhonen. 2017. “Ninth Graders and Climate Change: Attitudes towards Consequences, Views on Mitigation, and Predictors of Willingness to Act.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 26 (3): 223–239. doi:10.1080/10382046.2017.1330035.

- Hickman, C., E. Marks, P. Pihkala, S. Clayton, R. Lewandowsk, E. Mayall, B. Wray, C. Mellor, and L. van Susteren. 2021. “Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs about Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey.” The Lancet Planetary Health 5 (12): e863–e873. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3.

- Hunter, L. M., A. Hatch, and A. Johnson. 2004. “Cross-National Gender Variation in Environmental Behaviors.” Social Science Quarterly 85 (3): 677–694. doi:10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.00239.x.

- IPCC. 2007. “Summary for Policymakers.” In Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M. Tignor and H.L. Miller, 1–18. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. 2021. “Summary for Policymakers.” In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu and B. Zhou, 1–32. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- IPCC. 2022. “Sixth assessment report: Summary for policymakers headline statements.” 28 February 2022. Accessed 29 June 2022. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/resources/spm-headline-statements/

- Kassan, N, and H. Leser. 2021. “Climate poll 2021.” Lowy Institute. Accessed 18 January 2022. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/climatepoll-2021

- Khadka, A., C. J. Li, S. W. Stanis, and M. Morgan. 2021. “Unpacking the Power of Place-Based Education in Climate Change Communication.” Applied Environmental Education & Communication 20 (1): 77–91. doi:10.1080/1533015X.2020.1719238.

- Kunkle, K., and M. C. Monroe. 2019. “Cultural Cognition and Climate Change Education in the U.S.: Why Consensus is not Enough.” Environmental Education Research 25 (5): 633–655. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1465893.

- Kuthe, A., L. Keller, A. Körfgen, H. Stötter, A. Oberrauch, and K. M. Höferl. 2019. “How Many Young Generations Are There? – a Typology of Teenagers’ Climate Change Awareness in Germany and Austria.” The Journal of Environmental Education 50 (3): 172–182. doi:10.1080/00958964.2019.1598927.

- Lawson, D. F., K. T. Stevenson, M. N. Peterson, S. J. Carrier, E. Seekamp, and R. Strnad. 2019. “Evaluating Climate Change Behaviors and Concern in the Family Context.” Environmental Education Research 25 (5): 678–690. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1564248.

- Littrell, M. K., K. Tayne, C. Okochi, E. Leckey, A. U. Gold, and S. Lynds. 2020. “Student Perspectives on Climate Change through Place-Based Filmmaking.” Environmental Education Research 26 (4): 594–610. doi:10.1080/13504622.2020.1736516.

- Li, C, and M. Monroe. 2019. “Exploring the Essential Psychological Factors in Fostering Hope concerning Climate Change.” Environmental Education Research 25 (6): 936–954. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1367916.

- Mainieri, T., E. G. Barnett, T. R. Valdero, J. B. Unipan, and S. Oskamp. 1997. “Green Buying: The Influence of Environmental Concern on Consumer Behavior.” The Journal of Social Psychology 137 (2): 189–204. doi:10.1080/00224549709595430.

- McCright, A. M. 2010. “The Effects of Gender on Climate Change Knowledge and Concern in the American Public.” Population and Environment 32 (1): 66–87. doi:10.1007/s11111-010-0113-1.

- McNeill, K. L., and M. H. Vaughn. 2012. “Urban High School Students’ Critical Science Agency: Conceptual Understandings and Environmental Actions around Climate Change.” Research in Science Education 42 (2): 373–399. doi:10.1007/s11165-010-9202-5.

- Monroe, M., R. R. Plate, A. Oxarart, A. Bowers, and W. A. Chaves. 2019. “Identifying Effective Climate Change Education Strategies: A Systematic Review of the Research.” Environmental Education Research 25 (6): 791–812. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1360842.

- Morris, S., and G. J. Pickering. 2019. “Visual Representations of Climate Change in Canada.” Journal of Environmental and Social Sciences 6 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abb492.

- ABC News. 2019. “Student climate change protesters take to the streets across the country.” ABC News, 30.11.19. Accessed 29 August 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-11-29/school-strike-for-climate–sees-students-march-across-country/11749566

- Nairn, K. 2019. “Learning from Young People Engaged in Climate Activism: The Potential of Collectivizing Despair and Hope.” Young 27 (5): 435–450. doi:10.1177/1103308818817603.

- Ojala, M. 2012. “Hope and Climate Change: The Importance of Hope for Pro-Environmental Engagement among Young People.” Environmental Education Research 18 (5): 625–642. doi:10.1080/13504622.2011.637157.

- Ojala, M. 2015a. “Climate Change Scepticism among Adolescents.” Journal of Youth Studies 18 (9): 1135–1153. doi:10.1080/13676261.2015.1020927.

- Ojala, M. 2015b. “Hope in the Face of Climate Change: Associations with Environmental Engagement and Student Perceptions of Teachers’ Emotion Communication Style and Future Orientation.” The Journal of Environmental Education 46 (3): 133–148. doi:10.1080/00958964.2015.1021662.

- Ojala, M. 2017. “Hope and Anticipation in Education for a Sustainable Future.” Futures 94: 76–84. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2016.10.004.

- Ojala, M. 2021. “To Trust or Not to Trust? Young People’s Trust in Climate Change Science and Implications for Climate Change Engagement.” Children’s Geographies 19 (3): 284–290. doi:10.1080/14733285.2020.1822516.

- Pickering, G., K. Schoen, M. Botta, and X. Fazio. 2020. “Exploration of Youth Knowledge and Perceptions of Individual-Level Climate Mitigation Action.” Environmental Research Letters 15 (10): 104080. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/abb492.

- Pickering, G., K. Schoen, and M. Botta. 2021. “Lifestyle Decisions and Climate Mitigation: Current Action and Behavioural Intent of Youth.” Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 26 (6) doi:10.1007/s11027-021-09963-4.

- Pickering, G. J., N. Anger, J. Baird, G. Dale, and G. J. Tattersall. 2022. Use of crowdsourced images for determining 2D:4D and relationship to proenvironmental variables. Acta Ethologica 1–14. doi:10.1007/s10211-022-00401-5.

- Purves, N. 2021. “Cloiamte justice education: The need for climate action in education.” Professional Voice 14.2.3. Accessed 29 June 2022. https://www.aeuvic.asn.au/professional-voice-1423.

- Rooney-Varga, J., A. A. Brisk, E. Adams, M. Shuldman, and K. Rath. 2014. “Student Media Production to Meet Challenges in Climate Change Science Education.” Journal of Geoscience Education 62 (4): 598–608. doi:10.5408/13-050.1.

- Rotter, J. 1966. “Generalised Expectations for Internal vs External Control of Reinforcement.” Psychological Monographs: General and Applied 80 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1037/h0092976.

- Rousell, D, and A. Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles. 2020. “A Systematic Review of Climate Change Education: Giving Children and Young People a ‘Voice’ and a ‘Hand’ in Redressing Climate Change.” Children’s Geographies 18 (2): 191–208. doi:10.1080/14733285.2019.1614532.

- Salehi, S., Z. P. Nejad, H. Mahmoudi, and S. Burkart. 2016. “Knowledge of Global Climate Change: View of Iranian University Students.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 25 (3): 226–243. doi:10.1080/10382046.2016.1155322.

- Sanson, A., S. E. L. Burke, and J. Van Hoorn. 2018. “Climate Change: Implications for Parents and Parenting.” Parenting 18 (3): 200–217. doi:10.1080/15295192.2018.1465307.

- Schultz, P. 2000. “Empathizing with Nature: The Effects of Perspective Taking on Concern for Environmental Issues.” Journal of Social Issues 56 (3): 391–406. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00174.

- Schweizer, S., S. Davis, and J. L. Thompson. 2013. “Changing the Conversation about Climate Change: A Theoretical Framework for Place-Based Climate Change Engagement.” Environmental Communication 7 (1): 42–62. doi:10.1080/17524032.2012.753634.

- Scott-Parker, B, and R. Kumar. 2018. “Fijian Adolescents’ Understanding and Evaluation of Climate Change: Implications for Enabling Effective Future Adaptation.” Asia Pacific Viewpoint 59 (1): 47–59. doi:10.1111/apv.12184.

- Semenza, J., D. Hall, D. Wilson, B. Bontempo, D. Sailor, and L. George. 2008. “Public Perception of Climate Change.” American Journal of Preventative Medicine 35 (5): 479–487. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.020.

- Tattersall, A., J. Hinchliffe, and V. Yajman. 2022. “School Strike for Climate Are Leading the Way: How Their People Power Strategies Are Generating Distinctive Pathways for Leadership Development.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 38 (1): 40–56. doi:10.1017/aee.2021.23.

- Tindall, D. B., S. Davies, and C. Mauboulès. 2003. “Activism and Conservation Behavior in an Environmental Movement: The Contradictory Effects of Gender.” Society & Natural Resources 16 (10): 909–932. doi:10.1080/716100620.

- Tobler, C., V. Visschers, and M. Siegrist. 2011. “Eating Green. Consumers’ Willingness to Adopt Ecological Food Consumption Behaviors.” Appetite 57 (3): 674–682. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2011.08.010.

- Trott, C. 2020. “Children’s Constructive Climate Change Engagement: Empowering Awareness, Agency, and Action.” Environmental Education Research 26 (4): 532–554. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1675594.

- Linden, V. 2015. “ The Social-Psychological Determinants of Climate Change Risk Perceptions: Towards a Comprehensive Model.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 41: 112–124. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1675594.

- White, P., J. Ferguson, N. O’Connor Smith, and H. O’Shea Carre. 2022. “School Strikers Enacting Politics for Climate Justice: Daring to Think Differently about Education.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 38 (1): 26–39. doi:10.1017/aee.2021.24.

- Whitehouse, H. 2021. “Australia needs a climate change education policy.” Professional Voice 14.2.2. Accessed 29 June 2022. https://www.aeuvic.asn.au/professional-voice-1422

- Whitehouse, H., and L. Larri. 2019. “Ever Wondered What Our Curriculum Teaches Kids about Climate Change? The Answer is ‘Not Much.” The Conversation :1–4. https://theconversation.com/ever-wondered-what-our-curriculum-teaches-kids-about-climate-change-the-answer-is-not-much-123272

- Wynes, S., and K. Nicholas. 2017. “The Climate Mitigation Gap: Education and Government Recommendations Miss the Most Effective Individual Actions.” Environmental Research Letters 12 (7): 074024. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aa7541.

- Wynes, S., K. Nicholas, J. Zhao, and S. Donner. 2018. “Measuring What Works: Quantifying Greenhouse Gas Emission Reductions of Behavioural Interventions to Reduce Driving, Meat Consumption, and Household Energy Use.” Environmental Research Letters 13 (11): 113002. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/aae5d7.

- Wynes, S., and K. A. Nicholas. 2019. “Climate Science Curricula in Canadian Secondary Schools Focus on Human Warming, Not Scientific Consensus, Impacts or Solutions.” PLoS One 14 (7): e0218305.0218305 doi:10.1371/journal.

- UN Climate Change. 2021. COP 26 The Glasgow Climate Pact, 1–28. https://ukcop26.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/COP26-Presidency-Outcomes-The-Climate-Pact.pdf

- UNESCO. 2021. “Biosphere reserves.” Accessed 29 August 2021. https://en.unesco.org/node/314143

- UNESCO. 2020. “Education for sustainable development: A roadmap, #ESD for 2030.” Accessed 29 June 2022. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000374802.locale=en.

- Verlie, B., and A. Flynn. 2022. “School Strike for Climate: A Reckoning for Education.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 38 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1017/aee.2022.5.