Abstract

Climate change threatens hard won progress in the education and life outcomes of adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) by compounding the harmful effects of gender inequality and poverty. In recent years, there has been a rise in global advocacy for gender transformative education for climate justice that addresses the underlying gender inequalities driving climate vulnerability for adolescent girls in LMICs. But, has the international development and education community responded to this call? This paper seeks to establish a baseline for answering this question through a landscape analysis of actors working on issues of gender and climate change with youth, especially girls, as well as a landscape analysis of publicly available curricular materials on climate justice and gender equality. We find that although there are many nongovernmental efforts focused on different entry points into the nexus of gender, education, leadership, and climate change, there is much more room for aligning gender equality and climate justice programming for girls. This paper highlights the gaps and opportunities for doing so and offers a taxonomy of programming approaches to guide actors and their collaborators toward more intersectional educational programming.

Introduction

The gendered impacts of climate change threaten hard won progress toward gender equality, especially for women and girls, in all their diversity, in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where gender roles heavily constrain their opportunities (Jameel et al. Citation2022; Rao et al. Citation2019). This threat is especially significant for the girls’ education community–defined here as the international development and education organizations that target improved life outcomes through education for adolescent girls in LMICs (Malala Fund Citation2021).Footnote1

Research in LMICs shows that during weather-related crises, girls are often more likely than boys to have their schooling interrupted due to girls’ role in environment-dependent household chores (e.g. securing water) and agriculture-based livelihoods (Graham, Hirai, and Kim Citation2016; Nordstrom and Cotton Citation2020; Nübler et al. Citation2021; Porter Citation2021).Footnote2 Adolescent girls are also more likely to have their education end prematurely due to their heightened risk of early and forced child marriage as households attempt to ease resource scarcity caused by environmental shocks and/or to secure a girl’s future in times of environmental uncertainty (Alston et al. Citation2014; Asadullah, Islam, and Wahhaj Citation2021; CitationFigueroa et al. 2020; Tsaneva Citation2020). Based on trends like these, Malala Fund (Citation2021) estimates that climate change will prevent at least 12.5 million girls in LMICs from completing their education by 2025 (Malala Fund Citation2021). Such gendered impacts of climate change point to an urgent need for girls’ education actors (and global education actors, in general) to address the intersections of gender equality and climate justice through their programming.

Climate justice is the recognition that climate change impacts people differently—a difference that is influenced by a combination of historic economic inequalities that are structured by things like gender and race and by historic and contemporary geopolitics that preserve the power of the elite (Sultana Citation2022). The unequal impacts borne by girls and women in LMICs are a stark reminder of how those who are least responsible for climate change are often impacted the worst (Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development [APWLD] et al. 2022; Terry Citation2009). In this context, climate change is an issue of human rights as much as an issue of greenhouse gases. Addressing climate change must be done through solutions that redress inequalities and transform unequal relations of power. While underlying gender inequalities and harmful gender practices structure adolescent girls’ unique climate vulnerabilities, research suggests that a quality, gender-transformative education—one that addresses the root causes of gender inequality and seeks to transform harmful gender norms, roles, and relations of power (Plan International et al. 2021)—can enhance not only girls’ own climate resilience and adaptive capacity but also that of her community as well (UNFPA, UNICEF, UN Women Citation2020). Specifically, a gender-transformative education places girls on three interrelated pathways to climate empowerment (Kwauk and Braga Citation2017).

First, it ensures girls (and boys) have the knowledge and awareness of their rights, including their sexual and reproductive health and rights, and the skills and agency to claim those rights and to determine the course of their own lives (Haberland Citation2015; Mekonnen and Worku Citation2011; Mocan and Cannonier Citation2012). Second, it ensures girls can acquire important ‘green skills’, including environmental and climate literacies (Simpson et al. Citation2021), needed to participate, succeed, and lead careers in green sector industries as her country transitions to a green economy (Kwauk and Casey Citation2022; ILO Citation2015; Transform Education et al. Citation2021). And third, it builds opportunities for girls to engage in decision-making that builds confidence and experience to take on leadership roles in her household, community, and country, creating the conditions for systems-transforming policy and solutions that benefit both her community(ies) and the planet (Ergas and York Citation2012; Lv and Deng Citation2019; Mavisakalyan and Tarverdi Citation2018; Norgaard and York Citation2005; Nugent and Shandra Citation2009).

In the face of a growing climate crisis, international development and education organizations must consider adolescent girls’ unique climate risks as they intersect with gender, class, geographic location, and other structures of power that differentially shape their climate vulnerabilities (Kaijser and Kronsell Citation2014; Amorim-Maia et al. Citation2022). For decades, actors from other sectors have similarly helped to advance a more holistic view around the broader intersections of gender (i.e. women), the environment, and climate change (Terry Citation2009; UN Women Watch Citation2009; Wamukonya and Skutsch Citation2002). Such an approach would help to unlock the transformative potential of education for both gender equality and climate justice, supporting the advancement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals as well as the Paris Agreement. But doing so requires new intersectional approaches to formal and non-formal educational programming that challenges ‘education-as-usual’, acknowledges systems of oppression and discrimination, and seeks to address unequal relations of power (Donville Citation2020; Kwauk Citation2022b; Plan International et al. Citation2021; Transform Education et al. Citation2021). Such approaches will need to be (co-)designed with youth and delivered across formal and non-formal educational contexts (Jelks and Jennings Citation2022; Transform Education et al. Citation2021).

Indeed, over the last five years and especially during the lead-up to the 2021 UN Climate Change ConferenceFootnote3 and the 2022 UN Commission on the Status of WomenFootnote4 (which officially addressed the intersections of gender equality and climate change for the first time in its history), there has been a notable increase in global advocacy around the need to address the climate crisis through an intersectional feminist lens–that is, rooted in the cross sections of critical feminism, anti-racism, decolonization, and other liberation movements including the fight against environmental racism and climate injustice (Malik Citation2019; APWLD et al. 2022; Thomas Citation2022; Transform Education et al. Citation2021). Fueled largely by the gendered impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, these advocacy efforts have progressively focused on raising global awareness and increasing global investments to girls’ education as an important climate solution (see for example, Patterson et al. Citation2021; Rost, Cooke, and Fergus Citation2021; Transform Education et al. Citation2021). But are these advocacy efforts mirrored by educational programming and opportunities for girls? Are implementing actors in the education sector meeting the needs of the times, or has the gap in quality educational programming widened when it comes to educational opportunities that advance gender equality and climate justice?

Research looking explicitly at the intersections of gender equality, climate justice, and education has been dominated by a focus on unearthing the evidence of the impact that climate change has on girls’ education and/or on gender inequality, and of the impact that investing in girls’ education can have on climate outcomes of interest, like increased climate resilience (Bangay Citation2022; Chigwanda Citation2016; Kwauk and Braga Citation2017; Plan International Citation2011; Sims Citation2021; Tanner, Mazingi, and Muyambwa Citation2021). To date, there have been little to no studies attempting to understand whether education programming itself has turned to address these topics. While there have been studies seeking to gauge global attention to the intersections of girls’ education and climate change at the policy level (Kwauk et al. Citation2019), this study aims to do so at the programming level.

Fully answering the question of whether education programming has caught up to the urgent need to address gender equality and climate justice would require resources to monitor global trends over time—resources which are beyond our reach. Nevertheless, we wanted to start by establishing a baseline ecosystem of actors that are tackling this challenge, as well as to identify gaps and opportunities for collaboration and coordinated action that benefits both girls’ education and climate action. First, we conducted a landscape analysis of actors working in four domain areas most germane to the achievement of gender equality, girls’ empowerment, and climate action: gender, education, climate change, and leadership development. We examined the programming areas of these actors to better situate them within this ecosystem. Second, we conducted a landscape analysis of program curricular materials to analyze how actors are approaching the teaching of climate change and gender equality. Together, these two scans (actors and curriculum) help us to identify recommendations for how educational programming might better integrate climate and gender justice topics. In the sections that follow, we overview our methodology (and its underlying rationale) before highlighting our key findings from both analyses.

Methods

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child enshrine the right to education for all children. As such, states bear the responsibility of delivering education to all children and youth. Different actors have attempted to define the parameters of such an education, especially with regards to a minimum standard of quality, including being gender transformative (Plan International et al. 2021). In the context of the climate crisis, quality education must address climate change (Education International Citation2021). However, research demonstrates that governments have not yet stepped up to the urgent need to deliver climate change education (McKenzie et al. Citation2019), let alone climate change education that is gender transformative (Kwauk Citation2022a; Kwauk et al. Citation2019). As is the case where governments lag in delivering basic education, nongovernmental actors (i.e. nongovernmental organizations) may need to help fill the gap in climate change education while developing the capacity of national education systems to do so. It is important to recognize this transitory state when trying to identify the present landscape of education actors working on gender equality and climate justice. Given the level of attention and ambition toward climate change in education policy, we anticipate that the gender equality and climate justice education landscape may be rather patchy.

As such, we cast a wide net for the actor scan in hopes of identifying any government and nongovernmental, national and international actors who might meet our inclusion criteria. The analysis was guided by an internet-based scan of global actors with programming in LMICS at the thematic intersections of our four domains of interest: gender, education, leadership, and climate change. We first identified known principal ‘nodal’ organizationsFootnote5 based on their global advocacy efforts (e.g. social media campaigns) and identified additional nodal organizations using different combinations of a range of related search terms (e.g. ‘girls’, ‘climate justice’, ‘green skills’, ‘education’, etc., see also Appendix A). This was followed by a secondary search of networks of partner organizations publicly listed on nodal organizations’ websites and social media channels. We also conducted member checks through 13 informational interviews with organizations currently working at the intersections of climate change and education. Interviewees were identified based on actor scans, snowballing recommendations, and existing professional networks of the first author. Information gathered from the interviews were used to confirm actors and programs already included in the scan, or to identify new nodal organizations to investigate.

Organizations identified through our search were included for the actor analysis based on their clearFootnote6 presentation of work and/or investmentFootnote7 in adolescent girls, education, leadership, and climate change.Footnote8 Our search identified 88 actors (entities, organizations, and collaboratives) working on 110 initiatives. We narrowed this down to 19 actors for analysis based on the criteria that the organization had an education or leadership development program on the topic of climate change that was directly implemented with a population of girls (see Appendix B).Footnote9

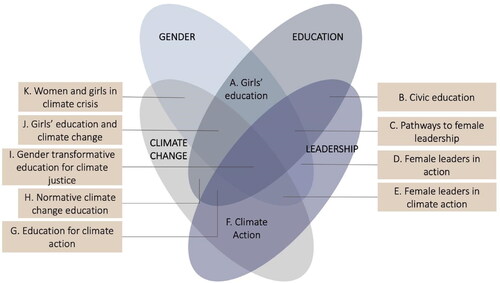

Next, to understand where each organization ‘sits’ in the broader actor landscape (see ), we analyzed the organization’s publicly available programmatic materials (including websites, social media, and publications). In doing so, we sought to identify their programmatic entry point–or, their main thematic area of focus for the specific program–into the topic of girls’ education and climate change, as well as their primary methods of engagement and whether the program focused on individual behavioral change or on catalyzing systemic change. We then categorized the organization into one or more of 11 potential programming areas (see for a description of these programming areas).Footnote10

Figure 1. Programmatic and curricular entry points of actors focused on the domains of gender, education, leadership, and climate change.

Table 1. Major programming areas across the four key domains of interest.

We developed the taxonomy of the 11 programming areas in and their descriptions in through a two-step process. First, we identified the programming area type by considering the type of programmatic focus that an organization might take if approaching their work from the lens of the intersecting domains. We used our professional knowledge of programs in gender, education, and climate change to give these programming areas a label. For instance, an organization sitting at the intersection of ‘gender’ and ‘education’ would likely have a programmatic focus on ‘girls’ education’ (Programming Area A). An organization sitting at the intersection of ‘gender’, ‘education’, and ‘leadership’ might have a programmatic focus supporting ‘pathways to female leadership’ (Programming Area C). And an organization sitting at the intersection of ‘gender’, ‘education’, ‘leadership’, and ‘climate change’ might be likely to have gender transformative education programming for climate justice (Programming Area I–our main area of interest driving this inquiry). Second, we used our knowledge of gender, education, and climate change programs to develop descriptions of each programming area, a process informed heavily by feminist and intersectional thinking on gender and climate change, as well as in education (APWLD et al. 2022; Maina-Okori, Koushik, and Wilson Citation2018; Plan International et al. 2021).

Together, and served as the primary metric against which we analyzed actor and curricular material and functioned as a taxonomy by which we classified actor type and curricular focus. Beyond the purpose of this study and paper, the taxonomy and framework can be used by gender and girls’ education advocates to monitor further programmatic developments in the field. And it can be used by practitioners as guideposts for designing more transformative educational programming based on their domains of focus.

In addition to understanding who may be in the gender, education, leadership, and climate change ecosystem, and where in this ecosystem, we wanted also to understand how actors might be approaching the teaching and learning of gender and climate change, or Programming Areas I and J. To complement the actor scan, we wanted to conduct a second scan of curricular and instructional work of the actors and their programs addressing the intersections of climate change education and girls’ education that were initially identified in the actor analysis. However, because we found few publicly available curricular materials that addressed our specific intersections of interest (Curricular Areas I and J, or the curricular equivalent to Programming Areas I and J in , above), we adjusted our approach and conducted a new search for two alternative but related types of curricular materials: 1) climate change education material with a social justice lens (referred to herein as climate justice curricular materialsFootnote11), and 2) gender equality education material with a social change lens (referred to herein as gender transformative curricular materials). The first falls within the most transformative vision of Curricular Area G (Education for climate action), and the second falls within the most transformative vision of Curricular Area A (Girls’ education). Climate justice curricular materials were searched using key terms like ‘climate justice’ or ‘social justice’ and ‘curriculum’ or ‘lesson plan’, while gender transformative curricular materials were searched using key terms like ‘gender transformative’, ‘gender justice’, or ‘gender equality’ and ‘curriculum’ or ‘lesson plan’.

In total 206 curricular materials were identified in our scan, 80 of which were included for the landscape analysis because they were publicly available, included substantial guidance and/or supplemental materials to support teaching, and had an identifiable focus on climate justice and youth leadership and action, or gender transformative social change) (see Appendix C).Footnote12 Materials were examined first to identify and understand their areas of overlap and differentiation in terms of their entry points (i.e. the major topics covered, learning objectives, and intended application) into the two topics (climate justice and gender equality); and second to understand their pedagogical approaches and orientation to learning and student action. Gaps were analyzed in Excel based on where there were fewer data points collected per any given curricular area and by analyzing the frequencies of different pedagogical approaches observed. The goal was to identify recommendations for developing more quality educational programming targeting the achievement of both climate justice and gender equality.

Our approach to conducting the actor and curriculum scans was limited in multiple ways—three of which we discuss briefly here. First, our approach was limited to internet searches and to the key search terms and search term combinations we pre-identified. Although we made every effort to cast a wide net (capturing 88 entities initially, more than we had anticipated given our knowledge of the practitioner landscape), we do not suggest that our scan is in any way comprehensive nor representative. The landscape of actors is also constantly growing and evolving, including well-established gender and climate actors expanding their work to adolescent girls and well-established girls’ education actors expanding their work to climate change. Thus, our findings should be interpreted with caution and our landscape viewed as a baseline or snapshot of the gender, education, and climate change ecosystem. Second, our search process was limited to and by English-language only websites and programmatic materials. This means that organizations and initiatives without an English-language online presence were not captured in our scan. Notably, this could include small grassroots and/or youth-led organizations as well. Future research should consider conducting a multilingual global survey or to follow the approach used to build the Evidence for Gender and Education Resource (EGER Citation2021). Third, our classification of actors and curriculum was limited by our analysis of publicly available materials. As a result, we may have missed critical information and material about an actor or have reached a conclusion about an actor that may not necessarily align with how the actor would have self-identified. Our conclusions about the pedagogical approach of teaching and learning materials—while reflective of a critical analysis of its discursive content—may not necessarily reflect the intention of the materials’ creators.

Findings from the landscape analysis of actors

Given our interest in identifying actors delivering education programming that advances gender equality and climate justice, we were especially interested in actors situated in Programming Areas J and I (girls’ education and climate change and gender transformative education for climate justice). Our search, however, only identified one initiative that fit our programmatic criteria for Programming Area I—a notable gap given the rise in global advocacy around gender transformative education for climate justice. Instead, our scan found actors generally coalescing around three points of programmatic entry: 1) Women and girls in climate crisis (Programming Area K) (3 actors total), 2) Female leadership in climate crisis (Programming Area E) (6 actors total), and 3) Girls’ education and climate change (Programming Area J) (6 actors total).

Actors working with a focus on gender and climate change (Programming Area K) demonstrate clear attention toward the gendered dimensions of climate change with a stated interest in women and girls. For instance, a program might focus on increasing women’s climate resilience through access to land for small-shareholder farming or promoting gender-conscious climate change mitigation efforts. This programmatic entry point is where actors are most clearly connecting girls and women to climate change issues distinctly based on gender, but where attention to education and action-oriented learning is lacking.

Actors working at the intersection of gender, climate change, and leadership (Programming Area E) focus on female leadership in formal and non-formal climate decision-making. For example, a program might focus on leveraging female leadership to introduce climate-conscious technologies into communities or encourage women’s participation in community negotiations about collective natural resource allocation. This area could, however, become a more meaningful entry point to girls’ engagement in climate decision-making if actors working on women’s and girls’ leadership development bridged efforts more deliberately to girls’ and women’s educational opportunities in climate science and social science.

Finally, while nearly all actors across this landscape analysis consider issues of gender, 32% of actors work at the intersection of gender, education, and climate change (Programming Area J), paying notable attention to the development of women’s and girls’ green skills development, green entrepreneurship and employment, and sustainability practices. Although much of these education and training efforts have an applied or practical component, the lack of attention to the leadership domain means that much of these action-oriented efforts are not targeted at addressing the underlying drivers of their climate vulnerabilities, leaving unaddressed issues of climate justice or gender-transformative systems change.

Locus of change: the individual or the system?

When it comes to how organizations target improved outcomes in gender and climate change, especially those operating in Programming Areas J and E, many actors (17) target change by directing efforts at strengthening individual capacity and skills among girls and women—a focus not uncommon among girls’ education organizations (Dupuy et al. Citation2018)). For example, of the 17 actors that work directly with women and girls, 16 deliver a range of educational activities, including skill building like life skills education. Nine actors teach women and girls green skills for green jobs (see ). Notably, only two actors in this landscape analysis are involved in education activities that focus on formal classroom learning for girls or young people more broadly. A minority of actors (6) target change by directing efforts at changing ‘the system’—by striving to promote gender in climate solutions (most notably, climate mitigation).

Table 2. Examples of green skills targeted by programs for women and girls.

Seven of the nine green skills programs were also accompanied by efforts to bolster female economic empowerment by increasing women’s participation in green jobs, green business development, or women’s integration into green production cycles, all while addressing (girl) child labor. Indeed, the majority of actors in this analysis (10) focus on women’s green entrepreneurship and green employment. In three cases, organizations provided women with small business and farming loans, seed funding, or investments in an individual enterprise. Notably, programs attending to entrepreneurial activities were almost exclusively focused on women, while programs oriented toward employment targeted adolescent girls and young women before or at the beginning of their professional careers.

In addition to education and employment activities, some actors also engaged in leadership training for women. In particular, eight organizations focus on promoting and supporting female leadership in grassroots initiatives and in specific industries and sectors (e.g. agriculture and waste management), while three organizations aim for increasing women’s leadership at a more global scale of influence (i.e. in international climate policy spaces). While these leadership development efforts differ depending on the target population (i.e. female farmers, women from low-income households, etc.), activities often share a focus on capacity building in technical climate or sustainability issues, as well as building empowerment skills like negotiation and decision-making, and resilience training. In addition, these activities may involve the development and support of female leadership networks, which bridges the focus on individuals with targeting more systems-level change.

In contrast to actors focused on targeting girls and women directly, six actors in our landscape analysis engaged in activities focused on systems change. Two of these actors targeted ‘the system’ by striving to promote gender in climate solutions, but not necessarily in collaboration with women and girls themselves. Instead, they work to strengthen civil society organizations’ (CSOs) institutional capacity around green or sustainability efforts that benefit women and girls. Meanwhile, four actors in our analysis highlight how systems-focused approaches can bridge efforts to shift structural change by working directly with and/or supporting individual girls and women, thus demonstrating a dual focus on both the individual and the system.

For instance, as mentioned earlier in the leadership training discussion, some actors are focused on increasing women’s participation in international climate policy negotiations (sometimes providing women with sponsorships and grant opportunities to do so) and encouraging women and girls to take leadership positions in their own communities. To support this, activities also aimed to provide women with mentorship and to promote network building among women and key institutions within specific fields (e.g. renewable energy). Notably, there was more attention to adding or amplifying female voices and leadership within existing systems (at international and national scales) over efforts at transforming existing decision-making structures to be more gender inclusive.

Notable gaps in the actor landscape

Our analysis of the actor landscape reveals four important gaps. First, as mentioned earlier, the impetus for this analysis was our interest in identifying whether advocacy efforts around girls’ education and climate change were being mirrored by organizations delivering educational programming that addresses the climate crisis through an intersectional lens. Although we identified actors addressing the intersections between gender and climate change, we found that initiatives are largely ignoring how these domains intersect with education and leadership development. This lack of attention to leadership is surprising given how long civil society and NGO actors have been advocating for increased women in climate leadership at international climate forums like the UN Climate Change Conference, as well as how popular leadership development for adolescent girls has been for NGOs focused on girls’ life skills education. Our scan identified only one organization with a programmatic focus in Area I (gender transformative education for climate justice) and six in Area J (girls’ education and climate change). This speaks to a significant lag in programming in comparison to growing advocacy, as well as to an obvious gap for girls in climate vulnerable and gender unequal contexts.

Second, we found that most green skills targeted by programs are technical in nature, missing an important opportunity to develop what Kwauk and Casey (Citation2022) call a breadth of green skills—or, a balance of technical, socioemotional, and justice- or civic-oriented skills—and thus an important opportunity to tap into the more transformative potential of education for broader systems change. Specifically, we found 12 actors providing green skills development opportunities for girls and women, nine of which, mentioned above, referenced building sector-specific green skills for green jobs (e.g. climate-smart agricultural techniques, solar installation, and business, environmental and ecosystem management skills). We found three actors also pay attention to gender empowerment skills like negotiation and understanding gendered relations of power, moving closer to what Kwauk and Casey (Citation2022) would call ‘transformative green skills’.

Third, more than half of the actors we identified have a stated programmatic focus on adult women and girls—often in the context of women’s leadership (i.e. Programming Area E)—while only four have a specific programmatic focus on exclusively young women, adolescent girls, or young girls—often in the context of improving green employment opportunities (i.e. Programming Area J). The heavy focus on women’s leadership means that current efforts to address gender inequality and climate injustice are limited to addressing the downstream effects of histories of exclusion from education and decision-making opportunities. Equal attention is needed to ensure girls have access to quality, gender transformative education and leadership opportunities to influence their foundational experiences before entering adulthood.

Finally, as this analysis illuminates, many actors focus on the individual as the locus of change. However, at the surface, approaches to ‘greening’ the individual did not appear to fall into a deficit approach characteristic of many efforts in international development and education (Aikman et al. Citation2016) and even in climate change education (Wibeck Citation2014). Rather, actors appear to be quite intent on shifting systems through individual capacity building that then enables systems to benefit from the inclusion of women and girls. Yet this focus on systems change is largely reminiscent of an ‘add women and stir’ approach made popular by Women in Development (WID) efforts in the 1970s (Koczberski Citation1998). Even among those six actors in our sample for whom systems change is the target of activities—including the four organizations with a dual focus on the individual and systems—their approaches focus on capacitating women and girls in order for them (women and girls) to change the systems they are a part of, including where they live and work. There appears to be little concomitant attention to address issues that would directly change systemic problems. For example, rather than pushing to shift existing climate governance structures to be more inclusive of female leaders, these efforts instead seek to equip women with tools to work within gender discriminatory climate governance systems. The relationship between individual and systems change for gender equality and climate justice as targeted by gender, education, leadership, and climate programs remains to be explored through more in-depth research that is unfortunately outside the scope of this landscape analysis.

Findings from the landscape analysis of curriculum

Our analysis of curricular and instructional materials aimed to deepen our understanding of current programmatic approaches to education that advance climate justice and gender equality (Curricular Areas I and J in , above). However, due to the gaps in the actor landscape discussed above (mainly, that we identified only one actor in Programming Area I) and the limited publicly available curricular materials for those actors we identified in Programming Areas J and K, we searched and analyzed curricular materials of initiatives focused on the most critical ends of the spectrum for Curricular Area G (climate justice curricular materials) and Curricular Area A (gender transformative curricular materials).

In the sections to follow, we overview our findings from two levels of analysis: topical and pedagogical. We first present our findings from the analysis of topical entry points for the climate justice curricular materials (sample of 64) and the gender-transformative curricular materials (sample of 16), separately, before presenting our findings from a comparative analysis of the topical areas covered by these two curricular types. We then present our findings of the dominant pedagogical approaches taken by both sets of materials as they converge and diverge in our analysis. Finally, we discuss notable gaps and opportunities for programming moving forward.

Entry points in climate justice curricular materials

Our sample of climate justice curricular materials consists of three primary types of teaching and learning materials: 45 structured curricula for use in formal and non-formal education settings, 14 instructional materials for educators (including lessons plans and activities, teaching guides, and assessment materials) to integrate climate justice concepts into teaching practice, and 5 self-guided online lessons on key issues related to climate change impacts (global and local), mitigation, and activism. Of the 36 materials that specify an intended age or grade range, the majority (31) are intended for students in primary and secondary school, with the most consistent target between 5th and 12th grade learners (middle and high school). Exceptions include materials that cater to preschool learners (1 total) and higher education students (4 total).

Notably, the climate justice curricular materials were often connected to school subject areas in economics, environmental studies, fine arts, geography, health, history, and government (United States), journalism, language, physical sciences, political science, social science, and sociology. These curricular connections are likely intentionally created by instructional designers to encourage formal educators to integrate these topics into lessons for traditional classrooms while meeting education standards. But aside from the more subject-specific topical entry points to climate justice topics, which ranged considerably, we found that curricular materials were largely guided by a focus on contextualizing climate change to learner’s lived experiences, introducing systemic issues of environmental and climate justice, and motivating climate activism and civic engagement through increased personal and collective agency, voice, and empowerment.

To elaborate, the climate justice materials in our sample introduce learners to the global sociopolitical context of climate change, notably, not just the science of climate change. In addition to the global aspects, these materials also emphasize place-based perspectives that contextualize and make more personally relevant the potentially abstract global processes and experiences of climate change (cf. Stapleton Citation2019). Often this contextualization involves consideration of climate change impacts (physical, social, political, economic, health and wellness, etc.) on individuals, specific communities, and local environments. It draws attention to personal and individual relationships with nature, the environment, and non-human living things. And, it highlights how global and local political and economic systems interact with climate change, often to help learners understand opportunities for civic engagement, collective leadership, and climate activism. In a few materials, contextualization also involves consideration of experiences of indigenous, marginalized, and underrepresented peoples, communities, and nations—locally and globally. Of note, only two climate justice materials in our sample included a reference to the gendered dynamics of climate change.

Alongside contextualization of the global to the local, our sample of curricular materials also leverage intersectionality and interdisciplinarity to introduce systemic issues of environmental and climate (in)justice, demonstrating to learners the interrelated nature of environmental degradation and social and political inequalities. For example, curricular materials in the US and other high-income country contexts generally explore through critical self-reflection issues connecting (under-)privilege and environmental racism. That is, these materials foreground the historic and systemic connections between socioeconomic status, wealth, capital, and race, and how these intersect with environmental health and community wellbeing, often with the largest environmental burdens placed on historically marginalized communities of color. While our curricular sample suggests programmatic attention is being directed toward important topics of people, power, and place (Kluttz and Walter Citation2018), our landscape analysis remains limited in scope to determine whether the materials create sufficient opportunity to connect cognitive expansion to increased political agency–although agency and empowerment are often stated learning outcomes.

Entry points in gender transformative curricular materials

Our scan of gender transformative curricular materials resulted in a more diverse set of teaching and learning materials than our climate justice sample in terms of the types of resources that are publicly available. Among the eight structured curricular materials we identified that targeted gender transformative education, there were activity and discussion plans, guides for running girls’ clubs and youth and community groups, recommendations for educators and parents to engage young people in discussions about gender roles, norms, and stereotypes, and manuals for gender sensitization trainings. While these materials are more diverse, they all aim at promoting gender empowerment and social change through understanding, deconstructing, and resisting patriarchal norms underlying girls’ marginalization and harmful gender practices. Entry points to gender transformative outcomes include reflecting on formations of gender identity and sexuality, building intra- and interpersonal skills, and interrogating systems of power.

In terms of gender identity and sexuality, gender transformative curricular materials focus largely on unpacking the intersecting social, political, and economic dimensions of gender identity through self-reflection. Moreover, sexuality, as it relates not only to gender and sexual expression and to sexual and reproductive health, is a notable entry point (5 materials) to challenging heteronormative norms and stigmas and changing behavior around consent and safety. Unsurprisingly, gender inequalities are almost universally discussed as systems of power imbalances that must be challenged and transformed. Notably, rather than placing the onus of change on the shoulders of girls and women alone, solutions raised by these materials often underscore the importance of cross-gender dialogue and cooperation. In fact, when men and boys are centered in these materials, it is often in the context of their important role as allies in challenging oppressive gender norms and systems.

Unlike the actor landscape analysis that identified an overemphasis on ‘specific’ (i.e. technical) skills in the context of green jobs, our analysis of gender transformative curricular materials highlighted how programmatic efforts have a considerable focus on ‘generic’ and ‘transformative’ skills that are critical to social change efforts (Kwauk and Casey Citation2022). This includes intra- and interpersonal skills like communication, relationship building, mutual respect, collaboration and teamwork, negotiation and decision making, perspective sharing and taking, and strategic planning and goal setting. Notably, gender transformative curricular materials in our sample also pay considerable attention to strengthening the voices of young women and girls, in particular to articulate experience and self-reflection.

Perhaps among the most transformative of the curricular entry points—and among the most transformative of the targeted skill sets—is attention to understanding and interrogating inequitable social and political systems of power in household, community, professional, and policy spaces as they relate to girls and women, although there is some attention to boys and men. Often, this attention translates into critically analyzing unequal gender relations and norms inherent in these systems and identifying how to work within and challenge them through political representation and rights-based advocacy. This curricular entry point is perhaps the strongest when it comes to bridging a focus on equipping the individual with a breadth of empowerment skills and changing inequitable systems through leadership and action.

Overlapping entry points and areas for greater convergence

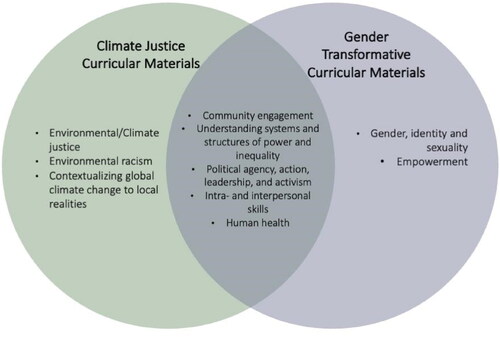

Much like the climate justice curricular materials, the gender transformative curricular materials aim to help learners move their learning into (social and political) action. Attention by both curricular entry points to youth-led and girl-led activism is almost entirely united in aiming to inspire social change and to transform inequitable and unsustainable dominant social, economic, and political structures. Indeed, the divergence in topical scope across both sets of curricular materials is largely offset by the endeavor to promote community engagement, especially at the local level. Other overlapping areas of focus include understanding unequal systems of power; attention to building political agency for empowered action; and centering human wellbeing (see ). These overlaps highlight how these curricular entry points share goals of creating social movement learning that is rooted in informed community engagement, social action, and critical analysis (McGregor et al. Citation2018).

This shared focus suggests opportunities for actors implementing these curricula independently to work in tandem or in sync with one another, integrating aspects of gender transformative materials into climate justice education and vice versa. Given the interconnected underlying drivers of gender inequality and climate injustice—mainly, historic marginalization and systematic exclusion—it would be an act of expanding cognitive entry points—that is, by incorporating additional topics or units of exploration—to create curricular convergence between climate justice and gender transformative curricular materials. This could help move programs implementing in Curricular Areas G and A into the ideal intersection of Curricular Area I.

Pedagogical and learning approaches of curricular materials

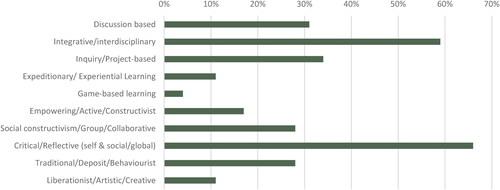

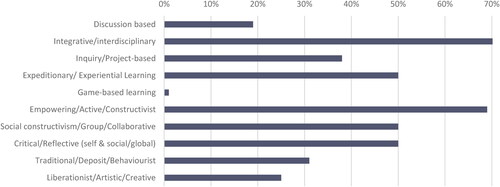

Climate justice and gender transformative curricular materials make distinct use of pedagogical approaches to learning. For example, the climate justice materials in our sample tend to use critical/reflective (66%) pedagogies (including attention to critical hope, anti-colonial, and radical relationality approaches) and integrative/interdisciplinary (59%) pedagogies in their learning activities and approaches to teaching (see ). While gender-transformative materials in our sample also rely heavily on integrative and interdisciplinary pedagogies (75%), these materials tend also to use a broader variety of pedagogical approaches, including empowering pedagogical approaches (69%) like gender-responsive pedagogy, experiential (50%), collaborative (50%), and critical/reflective (50%) pedagogical approaches (see ).

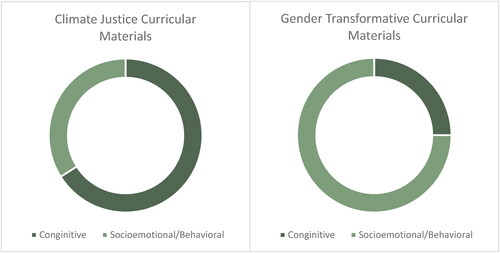

Our two curricular domains can also be characterized with distinct approaches to cognitive, socioemotional, and behavioral learning. Climate justice curricular materials, for instance, were inclined to use more cognitive approaches to teaching and learning that focused on information sharing and retention—a trend that others have similarly found for climate change education more broadly and globally (Benavot and McKenzie Citation2021; McKenzie et al. Citation2019). In contrast, gender transformative materials were more oriented towards socioemotional and behavioral forms of teaching and learning aimed at promoting the co-construction of knowledge and the creation of safe spaces and learning communities (see ).

Notable gaps in the curricular landscape

There is a critical gap in the curricular landscape when it comes to teaching and learning at the intersection of gender equality and climate justice (Curricular Area I) and, more generally, at the intersection of girls’ education and climate change (Curricular Area J)—a gap which led us to conduct our curricular scan in peripheral domains. But even our scan of the more critically leaning materials of Curricular Areas A (Girls’ education) and G (Education for climate action) resulted in few positive outliers. The lack of attention to gender in climate justice curricula appears to be largely reciprocated by a lack of attention to climate change in gender transformative curricula—although, we did identify two cases of climate justice curricular materials with references to gender. To ensure programming for girls is both gender transformative and climate empowering, greater attention is needed to develop curricula that bridges these two topical areas to create gender-transformative education for climate justice.

Second, gender transformative materials appear to have the strongest focus on empowerment and social change and their predominant focus is on empowering and experiential pedagogies. The underemphasis of these approaches in climate justice materials is surprising given our categorization of these materials in Curricular Area G, which intersects with the Leadership domain focused on empowering action and leadership development (see , above). Notably, we did observe in our 2021 scan a growth in climate justice curricular materials that utilize empowering pedagogical approaches targeted at building youth climate leadership and youth climate activism. Perhaps this is a growing departure from a predominant focus in climate change education on cognitive approaches to teaching and learning, as well as a long-standing trend for climate change education to be education about climate change rather than for climate action (Kwauk Citation2020). Nonetheless, it comes as no surprise that the majority of our sample of climate justice curricula ignores socioemotional areas like emotional literacy that could support youth climate activists in multiple ways, from dealing with eco-anxiety or climate grief to communicating effectively with climate deniers or those with different views on climate policy solutions.

Conclusions

Based on our analysis of the actor and curricular landscape, it appears as though educational programming for girls has not yet caught up with global advocacy efforts to address the climate crisis through an intersectional feminist lens. Although, these findings should be interpreted and generalized with caution given the small sample of actors identified. Where intersectional education programming is happening, it often falls short of what advocates might call gender transformative education for climate justice, integrating all four domains of gender, education, leadership, and climate change (Programming Area I) and targeting not only understanding of but also action to redress harmful gender roles, norms, and relations of power and the underlying social, political, and economic drivers of the climate crisis (Plan International et al. 2021; Kwauk Citation2022b). Instead, we identified three neighboring entry points around which clusters of organizations centered: women and girls in climate crisis (Programming Area K), female leaders in climate action (Programming Area E), and girls’ education and climate change (Programming Area J). Programming Area J comes closest to our intersection of interest but lacks a focus on leadership development and/or action that can catalyze broader systems change.

We argue that a baseline understanding the programming and curricular areas of focus is important for a number of reasons, not least of which to help identify critical programming and curricular gaps that may need to be filled. Understanding this landscape is also important for enhanced collaboration and coordinated action among a growing network of diverse actors. For example, based on this analysis there is an opportunity to bridge the plethora of initiatives focused on female leaders in climate action (Programming Area E) to actors focused on girls’ education, which would effectively pull actors in Area E into Area C, working to build pathways for girls to become women leaders in climate action. With the support of initiatives from Programming Area G (education for climate action), actors working in Area C could be pulled into Area I, the ‘sweet spot’ across all four domains. All of this goes without saying that the ultimate goal here is to ensure that formal and non-formal educational programming for girls in the context of the climate crisis is oriented toward empowerment and action for both people and the planet.

Finally, understanding the actor and curricular landscape can also help to create awareness of the overall level of ambition driving the field—and what targets or direction are needed to help raise that ambition. For instance, our analysis points to a need to bridge programmatic gaps with the Leadership domain to help actors at least move their educational programming on gender equality and climate justice from ‘fixing’ the individual to empowering the individual toward transformative action. At most integrating a leadership development dimension could help actors to expand their programmatic focus on the individual to include a focus on achieving broader gender transformative systems change. Our analysis also points to an opportunity for greater convergence within climate justice and gender transformative curricular materials. Specifically, both sets of materials tend to utilize critical/reflective and integrative/interdisciplinary pedagogies with an eye toward building learners’ understanding of systems and structures of power as well as their political agency, community engagement, and activism. Such pedagogical groundwork suggests that developing learning units that bridge issues of climate justice with issues of gender (in)equality would not be a far stretch to make.

While our actor and curricular landscapes were limited to publicly available, internet-searchable, English-language materials, this analysis nonetheless provides an important snapshot of growing attention by actors to tackle climate (in)justice and gender (in)equality through education. This analysis also adds to an emerging body of literature monitoring the progress of the field of climate change education more broadly. For example, our analysis of the curricular landscape confirms findings elsewhere in the literature (cf. Benavot and McKenzie Citation2021; McKenzie et al. Citation2019) that highlight a distinct overemphasis on cognitive learning in climate justice materials—in contrast to a tendency to rely on socioemotional/behavioral learning in gender transformative curricular materials. Also, our analysis of the landscape of actors illustrates that when initiatives target green skills development, they typically target green skills for green jobs (e.g. skills in climate-smart agriculture, management skills, handicrafts), echoing green skills discourse dominating just transitions policy discussions (Kwauk and Casey Citation2022). Notably, our scan of justice-leaning curriculum shows that there are efforts targeting a broader breadth of green skills, including transformative skills like political agency.

There is much room for development for this nascent field of gender transformative education for climate justice. The COVID-19 pandemic helped to propel attention to the intersections of gender and crises, and the road to COP26—which was delayed because of the pandemic—hastened the global education community’s attention to the intersection of gender and climate change. If the growth of climate justice curricular materials targeting the growth of youth climate activism in 2021 is any indication of where the broader field of education for climate action is heading, it is only certain that this landscape of gender transformative education for climate justice is heading in a similar direction. It is our hope that this landscape analysis provides the emerging field with a baseline to track its ambition to achieve gender equality and climate justice.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Lucina Di Meco for supporting this work, and for the comments and suggestions of three anonymous reviewers. All shortcomings are the authors’ own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on Contributors

Christina T. Kwauk is an education consultant and Research Director at Unbounded Associates.

Natalie Wyss is an education consultant at Unbounded Associates.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This paper approaches the concept of gender from a critical intersectional feminist lens (Amorim-Maia et al. Citation2022; Kaijser and Kronsell Citation2014; Thomas Citation2022) and understands gender as a social construct, as non-binary, as a continuum of identities, and as structured by relations of power. We focus on girls and women in this paper primarily because they, in all their diversity, have historically faced the most acute impacts of poverty, inequality, discrimination, and now the climate crisis. However, this experience is not homogenous, with some girls and women faring worse than others because of intersecting vulnerabilities defined by race, class, religion, and many other identities. We recognize that boys and men also experience climate change in ways that are uniquely structured by notions of masculinity; however because societies have granted boys and men dominance in the social and political economies, we give special attention to girls and women in this paper.

2 It is important to recognize that in some contexts predominant gender roles may put boys’ educational outcomes at greater risk of disruption by extreme climatic events than girls (see for example, Takasaki Citation2017). Such cases are a reminder that climate change’s gendered impacts are not homogenous, but rather highly context dependent.

3 The 2021 UN Climate Change Conference is also known as COP26, or the 26th Conference of the Parties.

4 The 2022 UN Commission on the Status of Women is also known as CSW66.

5 These nodal organizations were all known to the first author based on existing work and professional networks in girls’ education. These nodal organizations are all entities with established professional connections to a network of education organizations, programs, and leaders working in our domains of interest. These groups included CAMFED, FEMNET, Green Skills South Africa, Helvetas, MADRE (VIVA Girls Initiative), MAIA Impact, Office for Climate Change Education, Purposful, SELCO Foundation, SERVIR, The New Dawn Pacesetter (TNDP), Women and Earth Initiative (WORTH), and Youth Climate Leaders.

6 Easily identifiable and publicly searchable.

7 Identified via content analysis of actor’s stated areas of interest, work, programming, project titles, intervention descriptions, and published works.

8 Inclusion was not dependent on current work in these areas, therefore a portion of the landscape sample consisted of currently completed or non-active work.

9 85 actors were identified in an initial scan conducted in 2020. An additional 3 actors were identified in a scan conducted in 2021 following major growth in global advocacy around the intersections of girls’ education and climate change leading up to COP26. Notably, we did not identify any government entity that met our criteria for inclusion.

10 It is important to note that our categorization of actors was derived from our analysis of the thematic areas gleaned from publicly available program and curricular documents, and not how organizations may self-identify.

11 Attention to climate justice means recognizing that, globally, communities that are least responsible for the climate crisis often experience its impacts first and the worst. These communities often include Black, brown, and Indigenous peoples and nations; women and girls; low-income countries; small island developing states; etc. In the context of this analysis, we use the term climate justice to capture curricular approaches that attend to the systemic or underlying social drivers of the climate crisis, but for whom a focus on justice as a concept may not be articulated explicitly.

12 178 curricular materials were identified in an initial scan in 2020, 52 of which were included for in-depth analysis. An additional 28 curricular materials (24 climate justice and 4 gender transformative related materials) were identified in a scan conducted in 2021 following major growth in global advocacy around the intersections of girls’ education and climate change leading up to COP26. Notably, we did not include games that may have been developed as a standalone learning material.

References

- Aikman, S., A. Robinson-Pant, S. McGrath, C. M. Jere, I. Cheffy, S. Themelis, and A. Rogers. 2016. “Challenging Deficit Discourses in International Education and Development.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 46 (2): 314–334. doi:10.1080/03057925.2016.1134954.

- Alston, M., K. Whittenbury, A. Haynes, and N. Godden. 2014. “Are Climate Challenges Reinforcing Child and Forced Marriage and Dowry as Adaptation Strategies in the Context of Bangladesh?” Women’s Studies International Forum 47: 137–144. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2014.08.005.

- Amorim-Maia, A. T., I. Anguelovski, E. Chu, and J. Connolly. 2022. “Intersectional Climate Justice: A Conceptual Pathway for Bridging Adaptation Planning, Transformative Action, and Social Equity.” Urban Climate 41: 101053. doi:10.1016/j.uclim.2021.101053.

- Asadullah, M. N., K. M. M. Islam, and Z. Wahhaj. 2021. “Child Marriage, Climate Vulnerability and Natural Disasters in Coastal Bangladesh.” Journal of Biosocial Science 53 (6): 948–967. 10.1017/S0021932020000644.

- Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development (APWLD), The African Women’s Development and Communication Network (FEMNET), Fòs Feminista, & WEDO. 2022. “Toward a Gender-Transformative Agenda for Climate and Environmental Action: A Framework for Policy Outcomes at CSW66.” https://wedo.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/WRC_CSW-key-demands_2022-1.pdf

- Bangay, C. 2022. “Education, Anthropogenic Environmental Change, and Sustainable Development: A Rudimentary Framework and Reflections on Proposed Causal Pathways for Positive Change in Low- and Lower-Middle Income Countries.” Development Policy Review doi:10.1111/dpr.12615.

- Benavot, A., and M. McKenzie. 2021. “Learn for Our Planet: A Global Review of How Environmental Issues Are Integrated in Education.” http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en

- Chigwanda, E. 2016. A Framework for Building Resilience to Climate Change through Girls’ Education Programming. Washington, DC: Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/a-framework-for-building-resilience-to-climate-change-through-girls-education-programming/

- Donville, J. 2020. “Guidance Note: Gender Transformative Education and Programming.” Plan International. https://plan-international.org/eu/news/2020/08/20/gender-transformative-education-guidance/

- Dupuy, K., S. Bezu, A. Knudsen, S. Halvorsen, C. Kwauk, A. Braga, and H. Kiim. 2018. Life Skills in Non-Formal Contexts for Adolescent Girls in Developing Countries. CMI Report, 5. Washington DC: Chr. Michelsen Institute and Brookings.

- Education International. 2021. “Education International Manifesto on Quality Climate Change Education for All.” https://www.ei-ie.org/en/item/24244:education-international-manifesto-on-quality-climate-change-education-for-all

- Ergas, C., and R. York. 2012. “Women’s Status and Carbon Dioxide Emissions: A Quantitative Cross-National Analysis.” Social Science Research 41 (4): 965–976. 10.1016/J.SSRESEARCH.2012.03.008.

- Evidence for Gender and Education Resource. 2021. [website]. Evidence for Gender and Education Resource. https://egeresource.org/about/

- Figueroa, E., R. Pasten, D. Muñoz, and C. Colther. 2020. “Not a Dream Wedding: The Hidden Nexus between Climate Change and Child Marriage.” Series Documentos de Trabajo 508: 1–35. https://ideas.repec.org/p/udc/wpaper/wp508.html.

- Fund, Malala. 2021. “A Greener, Fairer Future: Why Leaders Need to Invest in Climate and Girls’ Education.” https://assets.ctfassets.net/0oan5gk9rgbh/OFgutQPKIFoi5lfY2iwFC/6b2fffd2c893ebdebee60f93be814299/MalalaFund_GirlsEducation_ClimateReport.pdf

- Graham, J. P., M. Hirai, and S.-S. Kim. 2016. “An Analysis of Water Collection Labor among Women and Children in 24 Sub-Saharan African Countries.” Plos ONE 11 (6): e0155981. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155981.

- Haberland, N. A. 2015. “The Case for Addressing Gender and Power in Sexuality and HIV Education: A Comprehensive Review of Evaluation Studies.” International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 41 (1): 31–42. 10.1363/4103115.

- International Labour Organization. 2015. Gender Equality and Green Jobs: Policy Brief. Geneva. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/green-jobs/publications/WCMS_36—72/lang–en/index.htm

- Jameel, Y., C. M. Patrone, K. P. Patterson, and P. C. West. 2022. “Climate–Poverty Connections: Opportunities for Synergistic Solutions at the Intersection of Planetary and Human Well-Being.” Project Drawdown. doi:10.55789/y2c0k2p2.

- Jelks, N. O., and C. Jennings. 2022. “Equitable and Just by Design: Engaging Youth of Color in Climate Change Education.” In Justice and Equity in Climate Change Education: Exploring Social and Ethical Dimensions of Environmental Education, edited by E. M. Walsh. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429326011.

- Kaijser, A., and A. Kronsell. 2014. “Climate Change through the Lens of Intersectionality.” Environmental Politics 23 (3): 417–433. doi:10.1080/09644016.2013.835203.

- Kluttz, J., and P. Walter. 2018. “Conceptualizing Learning in the Climate Justice Movement.” Adult Education Quarterly 68 (2): 91–107. doi:10.1177/0741713617751043.

- Koczberski, G. 1998. “Women in Development: A Critical Analysis.” Third World Quarterly 19 (3): 395–410. doi:10.1080/01436599814316.

- Kwauk, C. 2020. Roadblocks to Quality Education in a Time of Climate Change. Washington, DC: Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/roadblocks-to-quality-education-in-a-time-of-climate-change/

- Kwauk, C. 2022a. The Climate Change Education Ambition Report Card: An analysis of updated Nationally Determined Contributions submitted to the UNFCCC and National Climate Change Learning Strategies. Brussels: Education International. https://www.ei-ie.org/en/item/25344:the-climate-change-education-ambition-report-card

- Kwauk, C. 2022b. “Towards Climate Justice: Lessons from Girls’ Education.” NORRAG, Special Issue 7: 23–27. https://www.norrag.org/app/uploads/2022/05/Norrag_NSI_07_EN_ToC.pdf

- Kwauk, C., and Braga, A. 2017. Three Platforms for Girls’ Education in Climate Strategies. Washington, DC: Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/3-platforms-for-girls-education-in-climate-strategies/

- Kwauk, C., J. Cooke, E. Hara, and J. Pegram. 2019. Girls’ Education in Climate Strategies: Opportunities for Improved Policy and Enhanced Action in Nationally Determined Contributions. Washington, DC: Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/research/girls-education-in-climate-strategies/

- Kwauk, Christina T., and Olivia M. Casey. 2022. “A Green Skills Framework for Climate Action, Gender Empowerment, and Climate Justice.” Development Policy Review doi:10.1111/dpr.12624.

- Lv, Z., and C. Deng. 2019. “Does Women’s Political Empowerment Matter for Improving the Environment? A Heterogeneous Dynamic Panel Analysis.” Sustainable Development 27 (4): 603–612. doi:10.1002/sd.1926.

- Maina-Okori, N. M., J. R. Koushik, and A. Wilson. 2018. “Reimagining Intersectionality in Environmental and Sustainability Education: A Critical Literature Review.” The Journal of Environmental Education 49 (4): 286–296. doi:10.1080/00958964.2017.1364215.

- Malik, L. 2019. “We Need An Anti-Colonial, Intersectional Feminist Climate Justice Movement.” AWID. https://www.awid.org/news-and-analysis/we-need-anti-colonial-intersectional-feminist-climate-justice-movement

- Mavisakalyan, A., and Y. Tarverdi. 2018. “A Service of zbw Gender and Climate Change: Do Female Parliamentarians Make Difference?” (No. 221). https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/179923

- McGregor, C., E. Scandrett, B. Christie, and J. Crowther. 2018. “Climate Justice Education: From Social Movement Learning to Schooling.” In Routledge Handbook of Climate Justice, edited by T. Jafry, 494–508. Oxon, New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315537689.

- McKenzie, M., Y. Li, K. Hargis, and N. Chopin. 2019. Country Progress on Climate Change Education, Training and Public Awareness: An Analysis of Country Submissions under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Paris: UNESCO.

- Mekonnen, W., and A. Worku. 2011. “Determinants of Low Family Planning Use and High Unmet Need in Butajira District, South Central Ethiopia.” Reproductive Health 8 (1): 37–38. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-8-37/TABLES/4[PMC].[22151888.

- Mocan, N. H., and C. Cannonier. 2012. “Empowering Women Through Education: Evidence FromSierra Leon.” Working Paper 18016. https://www.nber.org/papers/w18016

- Nordstrom, A., and C. Cotton. 2020. Impact of a Severe Drought on Education: More Schooling But Less Learning (No. 1430; Vol. 125, Issue 2). Kingston, Ontario: Economics Department, Queen’s University. doi:10.1086/690828.

- Norgaard, K., and R. York. 2005. “Gender Equality and State Environmentalism.” Gender & Society 19 (4): 506–522. doi:10.1177/0891243204273612.

- Nübler, L., K. Austrian, J. A. Maluccio, and J. Pinchoff. 2021. “Rainfall Shocks, Cognitive Development and Educational Attainment among Adolescents in a Drought-Prone Region in Kenya.” Environment and Development Economics 26 (5–6): 466–487. doi:10.1017/S1355770X20000406.

- Nugent, C., and J. M. Shandra. 2009. “State Environmental Protection Efforts, Women’s Status, and World Polity: A Cross-National Analysis.” Organization & Environment 22 (2): 208–229. doi:10.1177/1086026609338166.

- Patterson, K. P., Y. Jameel, M. Mehra, and C. Patrone. 2021. “Girls’ Education, Family Planning, and Climate Adaptation.” https://www.drawdown.org/sites/default/files/Drawdown_Lift_Policy_Brief_Girls_Education_122121.pdf

- Plan International, Transform Education, UNGEI, and UNICEF. 2021. Gender transformative education: Reimagining education for a more just and inclusive world. New York: UNICEF. https://plan-international.org/publications/gender-transformative-education/

- Plan International. 2011. Weathering the Storm: Adolescent Girls and Climate Change. London. https://plan-uk.org/file/adolescent-girls-and-climate-changepdf/download?token=r2nEvZxb

- Porter, C. 2021. Education is Under Threat from Climate Change–Especially for Women and Girls. Oxford: University of Oxford. https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/features/education-under-threat-climate-change-especially-women-and-girls

- Rao, N., A. Mishra, A. Prakash, C. Singh, A. Qaisrani, P. Poonacha, K. Vincent, and C. Bedelian. 2019. “A Qualitative Comparative Analysis of Women’s Agency and Adaptive Capacity in Climate Change Hotspots in Asia and Africa.” Nature Climate Change 9 (12): 964–971. doi:https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-019-0638-y.

- Rost, L., J. Cooke, and I. Fergus. 2021. “Reimagining Climate Education and Youth Leadership.” https://plan-international.org/publications/reimagining-climate-education-and-youth-leadership#download-options

- Simpson, N. P., T. M. Andrews, M. Krönke, C. Lennard, R. C. Odoulami, B. Ouweneel, A. Steynor, and C. H. Trisos. 2021. “Climate Change Literacy in Africa.” Nature Climate Change 11 (11): 937–944. doi:https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-021-01171-x.

- Sims, K. 2021. Education, Girls’ Education and Climate Change. K4D Emerging Issues Report, 29. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies. doi:10.19088/K4D.2021.044.

- Stapleton, S. R. 2019. “A Case for Climate Justice Education: American Youth Connecting to Intragenerational Climate Injustice in Bangladesh.” Environmental Education Research 25 (5): 732–750. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1472220.

- Sultana, F. 2022. “Critical Climate Justice.” The Geographical Journal 188 (1): 118–124. doi:10.1111/geoj.12417.

- Takasaki, Y. 2017. “Do Natural Disasters Decrease the Gender Gap in Schooling?” World Development 94: 75–89. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.12.041.

- Tanner, T., L. Mazingi, and D. F. Muyambwa. 2021. “Adolescent Girls in the Climate Crisis: Empowering Young Women through Feminist Participatory Action Research in Zambia and Ziimbabwe. Plan International.” https://plan-international.org/uploads/2022/03/Voices-from-Zim-and-Zam-Technical-Report-Sep2021.pdf

- Terry, G. 2009. “No Climate Justice without Gender Justice: An Overview of the Issues.” Gender & Development 17 (1): 5–18. doi:10.1080/13552070802696839.

- Thomas, L. 2022. The Intersectional Environmentalist: How to Dismantle Systems of Oppression to Protect People + Planet. New York: Voracious Books.

- Transform Education, Plan International, Malala Fund & UNGEI. 2021. “Our Call for Gender Transformative Education to Advance Climate Justice.” https://plan-international.org/uploads/sites/27/2022/03/final_final_final_youth_led_statement-1.pdf

- Tsaneva, M. 2020. “The Effect of Weather Variability on Child Marriage in Bangladesh.” Journal of International Development 32 (8): 1346–1359. doi:10.1002/jid.3507.

- UN Women Watch. 2009. “Women, Gender Equality and Climate Change.” Fact Sheet. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/feature/climate_change/downloads/Women_and_Climate_Change_Factsheet.pdf

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women). 2020. “Technical Note on Gender-Transformative Approaches in the Global Programme to End Child Marriage Phase II: A Summary for Practitioners.” https://www.unicef.org/media/104806/file/Gender-transformation-technical-note-2019.pdf

- Wamukonya, N., and M. Skutsch. 2002. “Gender Angle to the Climate Change Negotiations.” Energy & Environment 13 (1): 115–124. doi:10.1260/0958305021501119.

- Wibeck, V. 2014. “Enhancing Learning, Communication and Public Engagement about Climate Change – Some Lessons from Recent Literature.” Environmental Education Research 20 (3): 387–411. doi:10.1080/13504622.2013.812720.

Appendix A

List of key search terms

Appendix tB

Actors included in the actor analysis. Actors marked with an asterisk (*) are no longer running.

Appendix tC

Learning materials assessed in the curricular analysis