Abstract

Civic engagement is recognized as a critical process to address environmental and other societal issues. To examine the intersection between environmental education and civic engagement, as reported in the peer-reviewed literature, we undertook a systematic mixed studies review to identify environmental education program outcomes related to civic engagement. The environmental education programs included in the final sample (n = 56) occurred in a range of settings, involved diverse audiences, and were generally longer than a month in duration. All 56 studies reported some level of positive findings, with 19 reporting civic-related outcomes at the community level, such as community learning, community resilience, partnership building, and increased social capital. Fifty studies reported civic-related outcomes at the individual level, with civic attitudes being the most frequent. Increased civic skills and civic knowledge were also commonly reported. Analysis revealed five themes related to environmental education practices and implementation that appear to support development of civic engagement: (1) focusing on the local community; (2) actively engaging learners through participatory and experiential approaches; (3) including action-taking as an integral part of the education program; (4) emphasizing development of lifelong cognitive skills; and (5) providing ongoing opportunities for participants to engage in meaningful social interaction.

Introduction

As the world grapples with complex problems such as a global pandemic, climate change, economic and social injustices, threats to democracy and human rights, and many others, increasing civic engagement is recognized as a necessary thread underlying efforts to address such challenges (Brulle Citation2010). An initial step in supporting and measuring civic engagement is defining what civic engagement means and entails. In the scholarly literature, various conceptualizations of civic engagement exist, alongside debates over civic engagement’s defining features and nuances (cf., Adler and Goggin Citation2005; Ekman and Amnå Citation2012; Schudson Citation2006; Serrat, Scharf, and Villar Citation2021; Zaff et al. Citation2010). Definitions range in their areas of focus, with some emphasizing community service while others tend toward social change; similarly, definitions can be narrow or broad, encompassing many activities and domains (Adler and Goggin Citation2005). Ehrlich’s (Citation2000, vi) definition captures many ideas essential to civic engagement, including an emphasis on the notion that it is both an outcome and process:

At the core of the issue, civic engagement means working to make a difference in the civic life of our communities and developing the combination of knowledge, skills, values and motivation to make that difference. It means promoting the quality of life in a community, through both political and non-political processes.

Researchers suggest a number of potential benefits of civic engagement that occur at both individual and collective levels. At the most comprehensive conceptualization, civic engagement not only supports institutions and governance, but also is essential for the very survival of democracy (LeCompte, Blevins, and Riggers-Piehl Citation2020; Skocpol and Fiorina Citation2004). Communities with actively engaged citizens are shown to be stronger, more resilient, more equitable, and more economically sound (Den Broeder et al. Citation2018; Nelson, Sloan, and Chandra Citation2019; Pancer Citation2015; Putnam Citation2020; Talò, Mannarini, and Rochira Citation2014). Individuals benefit from civic engagement through gains in strengthened networks, economic status, and social connection (Ballard, Hoyt, and Pachucki Citation2019; Dubowitz et al. Citation2020; Nelson, Sloan, and Chandra Citation2019; Pancer Citation2015). For youth, increased levels of civic engagement have been shown to improve social-emotional development and correlate with enhanced academic performance (Ballard, Hoyt, and Pachucki Citation2019; Balsano Citation2005; Cohen et al. Citation2021; Lerner Citation2004; Pancer Citation2015).

One of civic engagement’s greatest benefits, which applies across ages and socioeconomic groups, is the connection between civic engagement and the elusive goal of a just and equitable society. When more people become involved in their communities in a meaningful way, democratic governance becomes more representative of the people it was designed to support, protect, and benefit. Increased civic engagement infuses a community with new ideas, perspectives, discourse, and energy, helping overcome the negative cycle of unheard voices and disengagement that often lead to injustice and inequity (Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement Citation2022).

Despite the documented benefits of civic engagement, some researchers and practitioners report an ongoing decline in civic engagement across a range of relevant indicators, such as voter turnout, volunteering, and memberships in civic organizations (Delli Carpini Citation2000; Hylton Citation2018; Putnam Citation2020; Sanders Thompson and McClenden Citation2020; Winthrop Citation2020). Yet, accurately describing civic engagement trends is complex with some indicators, like involvement in protests, voting, and volunteering, showing increases, while other indicators, such as membership in civic organizations and number of local newspapers, continuing to decline (Atwell, Stillerman, and Bridgeland Citation2021; Sloam Citation2014). Researchers have coined the term ‘civic deserts’ to describe areas with few opportunities for civic engagement (Kawashima-Ginsberg and Sullivan Citation2017; Slavkova et al. Citation2022).

Studies have suggested possible avenues to combat the decline of civic engagement. Recommendations have included, but are not limited to, supporting non-governmental organizations and government agencies working on relevant local concerns (Martinson and Minkler Citation2006; Putnam Citation2020; Putnam, Feldstein, and Cohen Citation2003; Wray-Lake and Abrams Citation2020), facilitating civic engagement across diverse groups, and considering broadening the definition of what counts as civic engagement, to include, for example, digital civic engagement via social media (see Mirra and Garcia Citation2017).

The connection between civic engagement and environmental education

Key to understanding and growing civic engagement is civic education, a field of study and practice with a long history that has received increasing attention in recent years (Campbell Citation2019; Fitzgerald et al. Citation2021; Rogers Citation2017). Crittenden and Levine (Citation2018, para. 1) offer this definition of civic education:

In its broadest definition, “civic education” means all the processes that affect people’s beliefs, commitments, capabilities, and actions as members or prospective members of communities. Civic education need not be intentional or deliberate; institutions and communities transmit values and norms without meaning to. It may not be beneficial: sometimes people are civically educated in ways that disempower them or impart harmful values and goals. It is certainly not limited to schooling and the education of children and youth. Families, governments, religions, and mass media are just some of the institutions involved in civic education, understood as a lifelong process.

Relatedly, the field of environmental education works to motivate people to become more involved in their communities in ways similar to those of civic education (Aguilar Citation2018; Ardoin, Clark, and Kelsey Citation2013; Hollstein and Smith Citation2020; Simmons and Monroe Citation2020). The core tenets of environmental education include not only attitudes, values, knowledge, and skills, but also citizen action (UNESCO Citation1978). Thus, scholars and practitioners have noted intersecting processes and outcomes between civic and environmental education, highlighting connections between environmental education and civic-related constructs such as social capital, civics literacy, and environmental justice, among others (Berkowitz, Ford, and Brewer Citation2005; Braus Citation2020; Fraser, Gupta, and Krasny Citation2015; Krasny et al. Citation2015). Many of these civic-related constructs are prioritized in specific environmental education approaches such as sustainability education (Wals and Benavot Citation2017), civic ecology (Maddox and Krasny Citation2018), citizen science (Turrini et al. Citation2018), and community environmental education (Aguilar Citation2018).

To achieve the needed action to address environmental issues, environmental education scholars have promoted theories and forms of learning such as action competence (Jensen and Schnack Citation1997), social learning (Wals Citation2007), and political socialization (Chawla and Cushing Citation2007). Environmental education scholars have merged environmental protection and civic engagement into the construct of environmental citizenship (Dobson Citation2007), generally using this term to describe the ‘active participation of citizens in moving towards sustainability’ (Hadjichambis and Reis Citation2020, 1). Schild (Citation2016, 30–31) expands this definition, suggesting environmental citizenship is ‘more than pro-environmental actions and behaviors enacted by individuals; it also requires collective and participatory decision-making in an effort to promote the common good.’

This natural intersection of environmental and civic education creates an opportunity to address some of the challenges associated with increasing civic engagement. For civic educators, environmental issues provide an engaging, real-world context for learning and participation in civic life. Moreover, the public-goods nature of many natural resources (Flanagan, Gallay, and Pykett Citation2021) can create opportunities for civic action and connections with community partners (Simmons and Monroe Citation2020). Conversely, explicitly incorporating aspects of civic education into environmental education can improve program outcomes. For environmental educators, developing civic knowledge, skills, and dispositions is crucial to enhancing people’s involvement in their communities, as well as supporting their identification with and likelihood to take action on environmental issues (Gallay et al. Citation2016; Schusler and Krasny Citation2008). Civic participation in environmentally relevant issues also offers environmental educators an action-oriented, project-based approach, rather than offering a program solely focused on developing environmentally related knowledge, awareness, and attitudes.

While other researchers have theorized about or reviewed practices supporting civic engagement in an environmental context, such as how environmental action impacts civic learning (Schusler and Krasny Citation2008), how educational experiences influence environmental political participation (Levy and Zint Citation2013), and how environmental citizen science programs affect environmental citizenship (Adamou et al. Citation2021), we are unaware of studies that systematically review the relevant, empirical evidence base to identify civic engagement-related outcomes in environmental education programs. Therefore, in this study we sought to systematically search for and synthesize empirical evidence of environmental education outcomes related to civic engagement. What differentiates the work presented herein from the existing literature is a broad focus on civic engagement (beyond an environmental context) and an expansive definition of environmental education to include a range of approaches such as, but not limited to, education for sustainability, education for sustainable development, and citizen science. To obtain those data, we addressed the following primary research question: What environmental education program outcomes related to civic engagement are reported in the peer-reviewed, empirical literature? Additionally, with the dataset identified through that systematic review process, we conducted exploratory analyses to consider how and under what conditions environmental education programs contribute to civic engagement-related outcomes.

Statement of positionality

Like most social constructs, civic engagement is context-dependent and thus can be viewed differently based on who is discussing and examining the idea (Adler and Goggin Citation2005). How a person, institution, or culture conceptualizes and values civic engagement is impacted by attitudes and values, past experiences, existing knowledge, dominant culture, and geographic location (Brabant and Braid Citation2009; Flanagan and Levine Citation2010; Flanagan, Gallay, and Pykett Citation2021). We (the authors of this paper) and those involved in the research process of undertaking this systematic review currently reside in/hail from countries that are representative democracies. Our personal and professional belief structures support those aligned with social democratic governance and, therefore, encourage and argue for the power of involved community members. We believe that citizens have the right and privilege to be active participants in their own communities as well as the broader society. Within this frame, we see civic engagement as an essential component to addressing today’s sustainability challenges. We describe our positionality in acknowledgement of the ways in which our beliefs and experiences impact our thinking and writing about, as well as study of, civic engagement. That positionality is reflected in our work on this review.

Methods

Knowing environmental education research is home to a range of research designs and, based on our experience with prior environmental education-related reviews (e.g. Ardoin et al. Citation2018; Ardoin and Bowers Citation2020; Ardoin, Bowers, and Gaillard Citation2020), we conducted a systematic mixed studies review to account for the expected diversity in designs (e.g. qualitative, mixed methods, and quantitative; Pluye and Hong Citation2014). Additionally, systematic mixed studies reviews are appropriate tools for examining complex interventions, such as environmental education programs, which consist of multiple components and varying contexts, approaches, audiences, topics, lengths, and settings (Pluye and Hong Citation2014). Pluye and Hong (Citation2014, 36) suggest, ‘A typical mixed studies review question is, “What does the qualitative and quantitative evidence tell us about […]?”’

In our review, we wished to know what the research says about outcomes of environmental education programs that support civic engagement. We therefore followed conventional steps of a systematic review to search for, identify, and synthesize relevant research (Gough, Oliver, and Thomas Citation2017; Moher et al. Citation2009; Page et al. Citation2021) and modeled our process on previous reviews also focused on environmental education outcomes (Ardoin et al. Citation2018, Ardoin, Bowers, and Gaillard Citation2020; Ardoin and Bowers Citation2020). To address our research questions, we used a combination of content and thematic analysis (Heyvaert, Hannes, and Onghena Citation2016).

Systematic search of the peer-reviewed literature

We used EBSCOhost, an academic meta-database, to search for relevant research in five specific databases: Academic Search Premier, Education Full Text (H.W. Wilson), Environment Index, ERIC, and GreenFILE. We selected Academic Search Premier as an all-around general database and selected the other databases for their focus on education or the environment. We confirmed the journal coverage of each database to ensure that the major journals of the environmental education field were included.

Our search terms consisted of two sets: The first set of search terms focused on environmental education and selected synonyms. We chose the second set of search terms to identify research related to civic engagement. The final database query was: (‘environmental education’ OR ‘conservation education’ OR ‘education for sustainability’ OR ‘sustainability education’ OR ‘education for sustainable development’) AND (citizen* OR civic*). To ensure we captured relevant studies related to environmental citizenship, we added the search combination of (‘education’ AND ‘environmental citizenship’). We limited our search to peer-reviewed studies published after January 1, 2001. Search terms and parameters were selected based on the results of many scoping searches to explore the impacts of different search combinations. A subject specialist from the Stanford University library reviewed our initial search protocol and made suggestions to improve the rigor and specificity of our process, with the goal of helping achieve a system that would yield a manageable number of results, given the timeframe and resources available, while balancing breadth and relevancy. We ran the search, as described above, in January 2021.

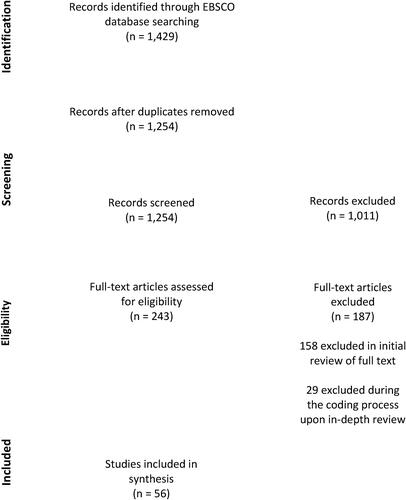

Following this described process yielded 1,429 citation records (after EBSCOhost removed duplicate records), which we then exported to Zotero, a bibliographic management program. Zotero identified an additional 175 duplicate records, leaving an initial search sample of 1,254 citations. (See for the PRISMA flow diagram.) Based on team discussions concerning the need to include climate change education as a search term, we ran an additional search in March 2021 using the terms ‘climate change education’ and ‘citizen*’ or ‘civic*’. This search surfaced 21 records not captured in the original search; however, none of those records were included in the final sample once we applied our vetting criteria.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram based on Moher et al. (Citation2009).

Vetting the search results for relevancy and quality

To determine the relevancy and appropriateness of each of the 1,254 citations, we developed a list of questions that would eliminate studies that were not written in English, were not peer-reviewed, and did not report on an implemented environmental education program with measured outcomes related to civic engagement. Using this decision tree, three team members read the abstracts of 30 randomly selected citations and decided whether each should be included or excluded at this stage. We compared the inclusion/exclusion decisions of the three team members, discussing and resolving any discrepancies. We then annotated the decision tree based on those team discussions, adding explanatory notes to clarify we were defining environmental education broadly (to include approaches like education for sustainability, citizen science, and education for sustainable development) and adding examples of potential civic-engagement related outcomes such as civic knowledge, civic skills, and civic action. At least one team member read each of the remaining abstracts to decide whether each study should be included or excluded from the final sample. The other two team members were consulted if the initial team member was uncertain as to whether the study met the criteria for inclusion outlined in the decision tree. In this way, we eliminated 1,011 citation records, leaving 243 records for full-text vetting in the second round of review.

We obtained the full-text article for each of the remaining 243 citation records. In this round, we applied the same decision tree from the previous round of vetting, but consulted the complete study text rather than only the abstract. We used additional criteria to conduct a basic study quality check. Those criteria required each included study to contain sufficient description of the methods and measures used in the study and to provide data to support claims made about civic engagement-related outcomes. Based on a review of the full text of the 243 studies at this stage, we eliminated 158 studies (the majority of excluded studies were excluded as they did not report civic-engagement related outcomes), leaving 85 studies to be coded at the next stage. During the coding process (described below), we excluded an additional 29 studies that were determined not to meet the inclusion and quality criteria (again, a lack of civic-engagement related outcomes was a common reason for exclusion as was issue with study quality). This vetting resulted in 56 studies remaining for the final review sample. (See Appendix A for a bibliography of the 56 studies.)

Extracting, coding, and analyzing data in the final sample

We initially extracted data from each study using Excel, a data spreadsheet program, and then coded each study in NVivo 12, a qualitative data software program, to allow for deeper analysis. Taking an inductive approach, we recorded data for three main areas of interest: study, program, and participant characteristics; program outcomes; and program strategies. For study, program, and participant characteristics, we recorded information concerning publication year, publication outlet, study location, study design, data collection methods, program setting, program length, program findings, and participant demographics. Using content analysis, we calculated the frequencies for each of those categories (Heyvaert, Hannes, and Onghena Citation2016).

During initial coding, we coded all reported program outcomes, which included both civic-engagement related outcomes and outcomes not related to civic engagement. We next conducted focused coding in NVivo, which involved organizing coded outcomes into the emergent categories of civic-engagement related outcomes, environmental outcomes, and academic outcomes. When reporting civic-related outcomes, study authors used a range of terminology to describe outcomes of interest (i.e. there were not standardized outcomes for reporting civic engagement and its supporting processes). This variation complicated the coding process, making it difficult to draw conclusions about discrete outcomes (which were not always well-defined) like social capital and community resilience. To create meaningful analysis, we purposefully grouped related outcomes into emergent categories at two different scales (two categories at the community level and four categories at the individual level). At the community level, we coded for the outcomes of social cohesion and community well-being. At the individual level, we coded for outcomes of civic knowledge and understanding; civic attitudes and dispositions; civic skills; and civic action. (See in the Findings section for example codes associated with each category.) We again used content analysis to calculate frequencies for each category.

Table 1. Reported civic engagement-related outcomes from environmental education programs (n = 56).

To address this review’s scoping question of how environmental education programs support civic engagement, we used inductive thematic analysis (Heyvaert, Hannes, and Onghena Citation2016; Nowell et al. Citation2017) to identify practices and program characteristics that appeared to support the development of civic engagement-related outcomes. We conducted an initial round of open coding focused on program descriptions, seeking common practices among all studied programs. In a second round of coding, we focused on text (usually in the Discussion or Conclusion sections) wherein the authors reflected on or theorized about program components that likely led to civic engagement-related outcomes. Finally, looking across initial codes and emergent categories, we abstracted common, thematic practices. As a form of peer debriefing (Lincoln and Guba Citation1985), two colleagues, who were not involved in the thematic coding, reviewed the themes for plausibility and reasonableness.

Findings

We present the findings in four sections: study characteristics, program and participant characteristics, reported civic engagement-related outcomes, and emergent themes related to the practice of environmental education in support of civic engagement. We share data on study, program, and participant characteristics to provide an overview of the programs studied in the final sample of articles and to highlight trends concerning how environmental education programs are impacting civic-engagement related outcomes.

Study characteristics

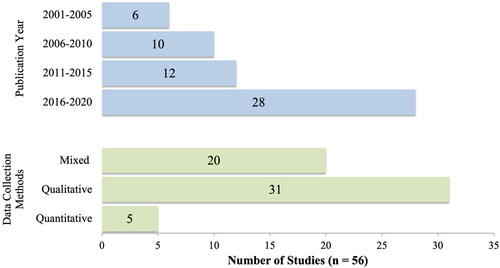

To provide an overview of the 56 studies in the final sample, we examined trends in publication year and journal outlet. The publication years were distributed over the 20-year timeframe, with no studies published in 2002, 2007, or 2013. (See .) Based on our sample, the amount of studies that report civic engagement-related outcomes appears to be increasing in recent years (approaching our 2021 cutoff). Half (n = 28) of the studies in the final sample were published in the most recent 5 years of the 20-year period.

In terms of journal outlet, the 56 studies were published in 33 different journals. Most frequently, studies in our sample appeared in Environmental Education Research (n = 12), followed by The Journal of Environmental Education (n = 5) and the International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education (n = 5). The remaining 30 journals were home to one or two articles in the review sample.

We anticipated and included studies with varied research methods and approaches. Five studies used data collection methods that primarily yield quantitative data, such as surveys and analysis of student work (see ). Thirty-one studies involved data collection methods that primarily yield qualitative data: such as interviews, focus groups, and observation. Twenty studies used a mix of qualitative and quantitative data collection methods. Study authors reported a range of research approaches, including action research, community-based research, design-based research, mixed methods, program evaluation, and ethnography. Nineteen of the studies involved a case-study approach.

Program and participant characteristics

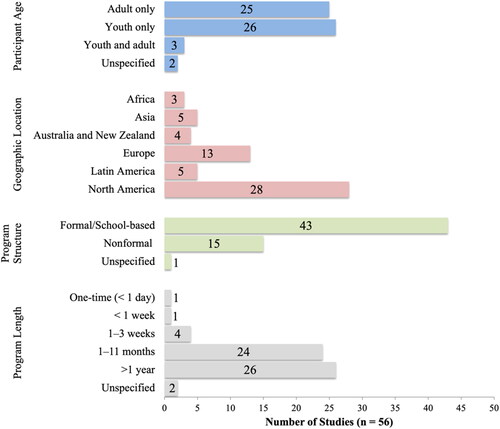

Participants in the environmental education programs under study in the final sample included youth (ages 0–18) as well as adults (18+; see ). Twenty-six studies (46%) focused on youth only, while 25 studies (45%) focused on adults only. Three studies (5%) included both youth and adults. Of the 26 studies with youth-only participants, only 1 included an early-childhood audience (ages 3 to 4 years), 14 involved primary-aged youth (ages 5–11), and 18 involved secondary-aged youth (ages 12–18). In the adult-only studies, 10 of the 25 studies included undergraduate university students and 6 of the studies involved graduate students.

Beyond participant age, studies varied tremendously in the amount and type of participant characteristics reported. Of the 56 studies, 15 (27%) did not report any demographic information for participants, such as race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, or location on the rural-urban gradient. The remaining 41 studies (74%) reported some type of demographic information, but inconsistent descriptions made categorization and reporting of trends difficult. Some diversity existed among participants across all studies. What remained unclear, however, due to inconsistent or lack of participant demographic data, was how representative the samples under study were of larger populations. (The only exception to this was participant age.)

Environmental education programs described in the 56 studies occurred across all six inhabited continents (see ). By far, the most frequently reported site of program location was the United States (n = 25), followed by the United Kingdom (n = 5). The programs occurred in a range of settings, although formal settings such as schools and colleges/universities were dominant (n = 43; see ). The majority of environmental education programs under study were designed to take place over an extended length of time (see ). Of the 56 studies, only one examined a one-time program that occurred for just a few hours. Many programs occurred over longer periods of time with 26 programs lasting more than a year and 24 taking place over 1 or more months (but less than a year).

As part of the coding process, we set out to categorize the different environmental education programs based on overall program approach. We wished to determine, for example, how many programs were classified as ‘citizen science’ or ‘education for sustainability.’ This proved to be a difficult endeavor, however, as study authors often reported programs as combining different approaches. Trajber et al. (Citation2019, 88), for instance, described the program in their study as ‘citizen science and nexus thinking under the aegis of participatory action research’ and Keen and Baldwin (Citation2004, 384) examined a ‘community-based research and service-learning program.’ As a result of such complex descriptions, we coded many programs to multiple categories of program type. The most popular categories were education for sustainability (n = 6), community-based programs (n = 5), service-learning programs (n = 5), and stewardship programs (n = 5). Other less common approaches included education for sustainable development, citizen science, place-based education, and sustainability education. Whenever possible, we coded programs based on the specific terms used by the study authors and this resulted in a list of specialized approaches, such as active citizenship education program (Zivkovic Citation2019), adventure learning (Olsen et al. Citation2020), and ecojustice education (Sperling and Bencze Citation2015). Given the small number of studies within each program type and due to the almost exclusive reporting of positive findings, we were not able to draw conclusions about what types of environmental education programs were most likely to lead to civic-engagement related outcomes within this particular sample. Therefore, instead, we conducted a thematic analysis of practices across all programs to identify common threads among the different program types that may be contributing to the development of civic engagement knowledge, skills, and practices (see the Emergent Themes Related to Practice section).

Reported civic engagement-related outcomes

All 56 studies reported some level of positive findings across a range of civic-related outcomes. Seventeen studies reported civic-related outcomes at the community level, such as community learning, community resilience, partnership building, and increased social capital. Alkaher and Gan (Citation2020), for example, presented a case study of an eight-year education for sustainability program in an Israeli elementary school. The researchers focused on the partnerships formed between the school and various entities such as local government agencies, higher education institutions, environmental non-governmental organizations, and a community garden. These partnerships not only led to collective action to promote sustainability, they also ‘broadened the local social capital’ (Alkaher and Gan Citation2020, 428). Under the category of community well-being, Smith, DuBois, and Krasny (Citation2016) investigated the impacts of civic ecology education (CEE) on youth and their communities following natural disasters (e.g. hurricanes and flooding) in the United States. The researchers described social learning and cognitive gains in youth and also documented an impact on community resilience, noting ‘CEE programs in disaster zones may represent important social adaptations in themselves that can help communities cope with, and recover from, external shocks’ (Smith, DuBois, and Krasny Citation2016, 452).

Fifty-three studies reported civic-related outcomes at the individual level, with civic attitudes being the most frequent (n = 39). Many of these civic attitudes related to self-efficacy, empowerment, and agency around collective action, with 29 studies describing an increase in these variables. Lara, Crispín, and Téllez (Citation2018) researched the impact of a participatory rural appraisal workshop with an Indigenous community in Mexico focused on fracking and hydroelectric dams. The authors shared:

It is difficult to evaluate the degree to which the CAP implemented here influenced in stopping the establishment of hydroelectric projects and fracking in the Totonacapan region; however, it did achieve the empowerment of indigenous people and their capacity for action and conflict resolution. (Lara, Crispín, and Téllez Citation2018, 4260)

Researchers also documented increases in other civic attitudes like civic responsibility and civic motivation. Peters and Stearns (Citation2003) studied an environmental learning community for U.S. university students exploring groundwater pollution. Comparing participant responses to a control group suggested an increase in civic responsibility after program completion. In their study of Canadian university students who participated in a community-based experiential learning (CBEL) program focused on a local, invasive plant species, Kalas and Raisinghani (Citation2019) reported increased civic motivation. They noted, ‘Many students acknowledged that this CBEL activity motivated them to learn more about ecology and continue community engagement as it provided them with an outdoor learning opportunity that was physically satisfying, mentally strengthening and morally rewarding’ (Kalas and Raisinghani Citation2019, 269).

Increased civic skills and knowledge were also commonly reported. Gallay et al. (Citation2016), for example, reported a range of positive outcomes after rural youth participated in a place-based stewardship education program. The authors described an increased understanding and knowledge of civic society, suggesting that the program helped students ‘understand themselves as stakeholders whose civic actions affect the quality of life for others, today and in the future’ (Gallay et al. Citation2016, 169) and develop ‘an awareness of their interdependence with other people and species, and an understanding of their capacities for taking action on behalf of the local community’ (170). McNaughton (Citation2006) presented evidence of civic skills development in a study of the use of educational drama as part of an education for sustainable development program in a Scottish primary school:

The nature of the drama activities afforded the children opportunities to develop essential skills in co-operating, collaborating, communicating their thoughts and ideas, stating their own opinions and listening to the opinions of others. There is also evidence of the use of higher-order skills: synthesis of ideas and information. They were able to infer and speculate about meanings and intentions and they could make important and difficult decisions by weighing up options. (p. 32)

Six studies reported a measure of civic action that continued after program completion and these actions reflected diversity in how civic engagement is defined. Dittmer et al. (Citation2018), for example, reported that, after participating in an environmental justice education program in Uganda and Germany, young people showed increased involvement in environmental and civic organizations, took part in protests, and engaged in community service. As part of a study of an adult volunteer stewardship program in local parks the United States, Dresner et al. (Citation2014) reported increased civic actions in the form of contacting elected officials, volunteering, and joining environmental and social organizations.

Although not the focus of this review, we did code for other reported positive outcomes to explore whether civic engagement-related outcomes were achieved alongside other environmental education outcomes. Thirty-four studies reported positive environmental outcomes such as improved environmental knowledge, attitudes, skills, and behaviors. Nineteen studies reported positive academic outcomes such as increased knowledge and skills in reading, writing, and science; improved career preparation and job skills; and increased interest in school and learning.

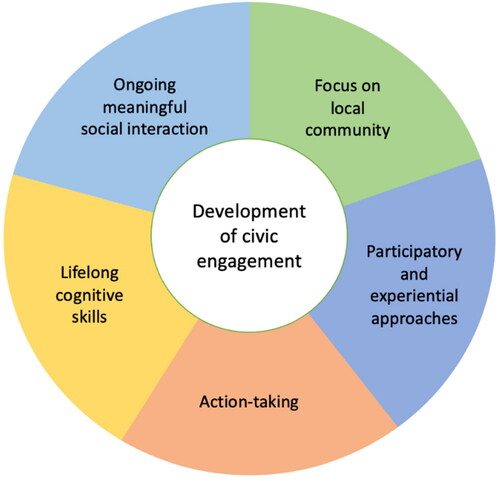

Emergent themes related to practice

A thematic analysis of the 56 studies revealed five themes related to environmental education practices and implementation that support development of civic engagement among participants: (1) focusing on the local community; (2) actively engaging learners through participatory and experiential approaches; (3) including action-taking as an integral part of the education program; (4) emphasizing development of lifelong cognitive skills; and (5) providing ongoing opportunities for participants to engage in meaningful social interaction. (See .) These themes emerged from a combination of study authors indicating what was particularly efficacious in achieving desirable outcomes in the studied programs, as well as from author reflection on what was ineffective in the programs. Below, we discuss each of these thematic practices in turn.

Focusing on the local community

In most of the programs, study authors described educators working to connect program content and topics to the local community. This frequently involved learning about the local environment and exploring local environmental issues (e.g. Alkaher and Tal Citation2014; Baum, Aman, and Israel Citation2012; Clegg et al. Citation2020), often through what was described as a place-based approach (e.g. Cincera et al. Citation2019; Gallay et al. Citation2016; Olsen et al. Citation2020). Ampuero et al. (Citation2015, 9) discussed one valuable aspect of a local focus, explaining, ‘The use of real-world environmental problems within the local community, the school community and the family gave students a context in which to immediately practice the course concepts.’ Green, Medina-Jerez, and Bryant (Citation2016, 123) suggested, ‘Coupling place-based EE with civic literacy enables students to recognize ways to politically participate in environmental decision making within a specific context.’ A focus on the local community, however, did not exclude an emphasis on connections to and recognition of environmental issues at larger scales. Several programs were described as explicitly making connections to regional and global communities (e.g. Mackey Citation2012; Porto Citation2016; Sperling and Bencze Citation2015). Haywood, Parrish, and Dolliver (Citation2016, 476) linked their positive findings to a place-based approach that connected participants to multiple scales:

Our results suggest that a place-based, data-rich experience linked explicitly to local, regional, and global issues can lead to measurable change in individual and collective action, expressed in our case study principally through participation in citizen science and community action and communication of program results to personal acquaintances and elected officials.

In addition to situating program content, topics, and issues in the context of the local community, many of the studied environmental education programs centered locality by developing and strengthening community partnerships. Partnerships were made between local universities colleges, and schools; local government agencies or local offices of state, regional, and federal government agencies; and local non-profits and citizen groups, among others (e.g. Dittmer et al. Citation2018; Gibbs et al. Citation2018). Although benefits of community partnerships—such as generation of new ideas and provision of opportunities for first-time engagement with community organizations—were highlighted, authors also acknowledged the time, effort, and resources needed to develop successful partnerships, emphasizing the need for clear communication and explicit commitment from all partners (Eflin and Sheaffer Citation2006; Kalas and Raisinghani Citation2019). In cases where partnerships were not an option or desirable, programs integrated and valued other meaningful contact between program participants and diverse members of the community. Outside formal partnerships, for example, program participants might describe meeting and working with local decision-makers (Iversen and Jónsdóttir Citation2019), ecosystem restoration professionals (Kalas and Raisinghani Citation2019), community activists (Peters and Stearns Citation2003), and other community stakeholders and members (e.g. Reeves Citation2019; Trajber et al. Citation2019).

Actively engaging learners through participatory and experiential approaches

This theme emphasizes active learning of participants, with authors describing several approaches and avenues for involving program participants directly in learning about the environment and environmental issues, as well as processes to address those issues. This intention to actively engage participants contrasts with more traditional, passive classroom learning in which an instructor delivers information to an audience via a presentation, although several studies did describe lectures as components of successful programs, suggesting that top-down knowledge transmission approaches can, at times, be effective (e.g. Dresner and Blatner Citation2006; Griswold Citation2017; Merenlender et al. Citation2016). However, overall, efforts to promote civic engagement seemed to benefit from programs that actively involved participants through participatory and/or experiential approaches.

Experiential learning is a well-studied area in psychology and learning sciences. Such approaches promote learning as a hands-on, community-driven, multi-modal endeavor, often accompanied by reflection, thinking, and action (Kolb Citation2014). Many of the 56 studies described learning through approaches such as field trips (e.g. Griswold Citation2017; Molderez and Fonseca Citation2018; Peters and Stearns Citation2003), drama- and art-based activities (e.g. Birdsall Citation2010; Johnson-Pynn and Johnson Citation2005; McNaughton Citation2004, Citation2006; Tsevreni Citation2011), writing exercises (Green, Medina-Jerez, and Bryant Citation2016; Johnson-Pynn et al. Citation2014; Sherman and Burns Citation2015), and service-learning (e.g. Eflin and Sheaffer Citation2006; Keen and Baldwin Citation2004; Schneller Citation2008). A number of studies explicitly described the approach to development and implementation of the environmental education program as ‘experiential’ and addressed how the program achieved key characteristics of experiential learning (e.g. Kalas and Raisinghani Citation2019; Peters and Stearns Citation2003; Zocher and Hougham Citation2020). Several also reported using a participatory approach, involving community stakeholders via an emphasis on local issues, communication, and inquiry, with the aim of engaging learners in a meaningful, relevant manner. Specific methods and processes included participatory action research (Ballard and Belsky Citation2010; Trajber et al. Citation2019), participatory research (Marques et al. Citation2020), participatory rural appraisal (Lara, Crispín, and Téllez Citation2018), and participative approaches (Cincera et al. Citation2019).

Including action-taking as an integral part of the educational program

Complementing the previous theme focused on active learning, our thematic coding also surfaced a preponderance of studies that featured an action project as part of the program, if not the defining focal feature of the program. For programs using a service-learning approach (e.g. Eflin and Sheaffer Citation2006; Keen and Baldwin Citation2004; Schneller Citation2008), taking action was a compulsory element. Even in non-service-learning programs, however, an action component was often presented as the ultimate goal of the program. Action projects varied tremendously in terms of scope, scale, and topic, but as natural resources are a common-pool resource (Ostrom Citation2000), environmental action projects, by default, benefit the broader community. Across the sample, program participants were involved in a range of efforts including, but not limited to, agroforestry-related projects such as setting up tree nurseries and planting native plants (Johnson-Pynn and Johnson Citation2005), conducting a letter-writing campaign to encourage a local water management agency to become involved in addressing water pollution (Bouillion and Gomez Citation2001), collecting and sharing data about local marine resources through a citizen-science program (Haywood, Parrish, and Dolliver Citation2016), and designing and implementing an education campaign to decrease bottled water consumption on a university campus (Bencze, Sperling, and Carter Citation2012).

In some of the reviewed studies, authors acknowledged the difficulties educators may encounter when striving to incorporate action-taking into educational programs. Birdsall (Citation2010) noted that the idea of students taking action may conflict with principles of conventional education in many countries, particularly where the learning content and curricula are predetermined, and educators have little autonomy or flexibility. Issues of power and empowerment may also arise, with potential tension between what the educators wish the participants to do and what participants view as their preferred course of action (e.g. Birdsall Citation2010; Dimick Citation2012). Another major barrier may be a lack of time and resources as learning about the action process, developing an action plan, and then carrying out the planned action can require substantial time and support. Several studies (e.g. Green, Medina-Jerez, and Bryant Citation2016; Lara, Crispín, and Téllez Citation2018) reported on programs focused on the action process, such as identifying the issue, gathering data and information, talking with stakeholders, and brainstorming solutions. In these cases, the final program goal was the development of an action plan, but those plans were not carried out, possibly due to a lack of time or support.

Emphasizing development of lifelong cognitive skills

Another emergent theme from the descriptions of successful program components was an intentional focus on developing participants’ cognitive skills. The skills were not always developed as part of an effort to support civic engagement but, rather, targeted due to their perceived importance for taking environmental action. Skills such as critical thinking (e.g. Ampuero et al. Citation2015; Peters and Stearns Citation2003; Volk and Cheak Citation2003), problem solving (e.g. Dresner and Blatner Citation2006; Green, Medina-Jerez, and Bryant Citation2016), systems thinking (e.g. Griswold Citation2017; Molderez and Fonseca Citation2018; Sherman and Burns Citation2015), and decision making (e.g. Birdsall Citation2010; Cincera et al. Citation2019; Dimick Citation2012) were emphasized in environmental education programs. Such skills commonly support both civic engagement and environmental action.

The development of the specified cognitive skills occurred via multiple activities and processes. McNaughton (Citation2006), for example, reported that young students were able to develop critical thinking skills through drama activities when the teachers worked directly to guide them in reflection and articulation of ideas. Dresner and Blatner (Citation2006) described the use of guided controversies to help undergraduate students develop problem solving skills. In these activities and others, instructors shared information about real-life, local issues. Groups of undergraduate students then worked to identify the problem, gather data, and formulate possible solutions.

As noted earlier, we drew the thematic findings not only from what was successful in these studies, but also from what authors reported as unsuccessful at times. A good example of such a balance relates to this theme: Although some study authors reported success in developing participant decision-making skills, others noted this to be a challenging, yet worthy, process. Dimick (Citation2012) reported that one program instructor, a high school teacher, struggled at times with giving students the power to make decisions, despite an understanding that allowing students to make decisions was impactful. While noting the importance of allowing participants to explore and engage in decision-making, Zivkovic (Citation2019) and DuBois, Krasny, and Smith (Citation2018) described a lack of opportunities for participant decision-making and practice in the programs they examined.

Providing ongoing opportunities for participants to engage in meaningful social interaction

As we coded and reviewed the 56 studies, we developed a number of codes related to social interaction. Those codes combined into the final theme highlighting the importance of providing regular opportunities for participants to interact with others. In some studies, perceived civic benefits arose from simply bringing people together and recognizing the value of the collective (Ardoin, Bowers, and Wheaton, Citation2022). Dresner et al. (Citation2014, 13), examining the benefits of an environmental education program focused on volunteers in local parks, wrote:

Stewardship activities in natural areas provide people living in a community with opportunities to interact with each other and create shared values and understandings, move beyond individual benefits and experience and work collectively in particular activities (trail building, invasive plant removal, and establishing native plants). Through participation, people may learn particular civic virtues, including trust and mutual respect, as well as practicing the democratic skills of discussion and organization. The outcomes of participation create ties that help bind society together (Edwards and Foley, Citation1997). Volunteering by its very nature is participation in public life, with people participating in a shared endeavor which they perceive to be meaningful, and puts an emphasis on serving the common good, not just the self (Arai and Pedlar, 2003).

Other authors emphasized the benefits of having participants interact with those who were different from themselves (e.g. Reeves Citation2019; Schusler and Krasny Citation2010), with some programs designed specifically to gather diverse participants (e.g. Alkaher and Tal Citation2014; Dittmer et al. Citation2018; McNeal et al. Citation2014; Porto Citation2016). McNeal et al. (Citation2014) wrote how the goal of public dialogue sessions in their studied program was to ‘give stakeholders who would not normally be in the same room together an opportunity to hear and deepen their understanding of others’ realities’ (p. 634). In their study of an environmental education program involving Bedouin and Jewish students in Israel, Alkaher and Tal (Citation2014) described one of the program’s main goals as having participants from the different communities interact to ‘increase respect and awareness of the students towards the other communities that share the same landscapes’ (p. 361).

Having participants interact with each other, or other members of the community, appeared to be a tool leveraged for promoting social and collaborative learning (Alkaher and Tal Citation2014; Ballard and Belsky Citation2010). Sometimes this occurred by including activities such as debates (e.g. Johnson-Pynn et al. Citation2014; Lee Citation2017), group work (e.g. Dresner and Blatner Citation2006; Griswold Citation2017; Volk and Cheak Citation2003), and peer-based learning (e.g. Dittmer et al. Citation2018; Volk and Cheak Citation2003). Other studies described more elaborate ideas such as forming communities of practice (Reeves Citation2019) and learning communities (e.g. Griswold Citation2017; Peters and Stearns Citation2003), as well as emphasizing opportunities for knowledge co-production (Bencze, Sperling, and Carter Citation2012).

Discussion

The findings from our systematic mixed studies review suggests environmental education programs can impact the individual-level outcomes of civic knowledge and understanding, civic attitudes and dispositions, civic skills, and civic action. (See .) While only 6 of the 56 reviewed studies attempted to measure community-level outcomes—perhaps indicative of the difficulty in measuring community/social outcomes (see Ardoin et al., Citation2022; Thomas et al. Citation2018)—all 6 of the studies reported some success with community-level outcomes such as social cohesion and community well-being. Taken together, these outcomes, achieved by a range of environmental education programs in diverse contexts, can contribute to increased civic engagement and the associated benefits that accrue from higher levels of civic engagement. Our findings provide evidence for what many environmental education practitioners have intuitively known and scholars have suggested: the focus of many environment education programs on problem-solving inherently supports civic engagement through the development of related knowledge, attitudes, dispositions, and skills that ultimately lead to collective action on behalf of communities and the environment. While additional research is needed to confirm relevant environmental education practices and conditions for developing civic engagement, this initial work suggests sustained, ongoing efforts that involve local community, active engagement, action-taking, cognitive skill development, and social interaction may impact a range of civic-engagement related outcomes.

Environmental education research and practice most frequently focus on environmental outcomes (Ardoin et al. Citation2018), although spillover effects in other domains, such as youth development (e.g. Stern, Powell, and Frensley Citation2021), physical and mental health (e.g. Ekenga, Sprague, and Shobiye Citation2019), and academic achievement (e.g. Artun and Özsevgeç Citation2018), among others, have also been studied (Ardoin et al. Citation2018; Ardoin and Bowers Citation2020). With their reporting and measurement of civic-engagement related outcomes, the studies in our review represent a significant sample of studies and on-the-ground programs pursuing environmental education outcomes not solely focused on the environment—and doing so at both an individual and community level. These studies align with ongoing discussions in environmental education focusing on community (Aguilar Citation2018), social learning (Wals Citation2007), and collective action (Ardoin et al., Citation2022), reflecting the entwinement of environmental issues with ‘society and our way of living’ (Jensen and Schnack Citation1997, 164). Addressing environmental issues requires people to create change at the community and societal levels, necessitating the development of environmental citizenship (Dobson Citation2007; Schild Citation2016) and a sense of individual and collective competence (Chawla and Cushing Citation2007).

Our review also explores a scoping question related to how and under what conditions environmental education programs can contribute to civic engagement. All of the 56 studies in our review report positive findings for at least one civic-engagement related outcome, even if not all program goals and objectives were achieved. These programs were able to achieve at least one positive outcome for both youth and adults. Working with young people can lay the groundwork for a lifetime of civic engagement, building skills now that may be activated later as those youth become leaders, voters, and changemakers through their professional and personal lives (Johnson-Pynn and Johnson Citation2005). Concurrently, younger and older adults alike are at pivotal ages and life stages, with regard to their ability to vote, participate in key civic roles, make change through their professions, and serve as role models for others. Looking more closely at the ages of participants reveals, of the 25 studies that targeted adults, 16 involved undergraduate or graduate students. Those audiences likely consist of young adults poised for action-taking. This is confirmed by the data on settings, with the vast majority of programs coded as school-based. Yet, also drawing on the participant age and setting data, a clear gap and opportunity exists in environmental education programming for older adults, who are often ready and willing to pursue civic-engagement related outcomes (Serrat, Scharf, and Villar Citation2021; Wilson and Simson Citation2012).

Another condition of note emerging from the data has to do with program length. The vast majority were not one-time or brief programs; rather, most spanned the course of a month or longer. (See .) Several authors acknowledged the value of longer-term interventions (Marques et al. Citation2020; Tsevreni Citation2011). Zivkovic (Citation2019) attributed the need for longer programs to the difficulty of building civic engagement given the complex nature of civic life and the interplay of scales and sectors that impact environmental issues. In an ideal world, meaningful environmental education would be infused throughout a person’s lifetime and support lifelong, lifewide learning and civic engagement (Ardoin and Heimlich Citation2021). Until this goal is a reality, striving to provide relevant, longer-term experiences may serve as a proxy.

Our inductive thematic analysis surfaced five practice-related themes involving local community, active engagement, action-taking, cognitive skill development, and social interaction. These identified practices have been named as important strategies for both environmental education (Monroe et al. Citation2017; North American Association for Environmental Education Citation2019) and civic education (Bennion and Laughlin Citation2018; Guilfoile and Delander Citation2014), adding support to the notion that environmental education and civic education are deeply intertwined. Levy and Zint’s (Citation2013, 553) work considering how to foster environmental political participation suggested that educators should offer ‘open-ended discussions of political issues, opportunities to identify with politically oriented groups, and involvement in actual and simulated democratic decision-making processes.’ Those experiences align with our themes of action-taking, active engagement, and social interaction.

Limitations and delimitations

We set out to address the question of what civic engagement-related outcomes have been reported in research examining environmental education programs. Findings from this systematic mixed studies review provide a snapshot to address our guiding question but are impacted by both the limitations and delimitations of our review, specifically, and of systematic reviews more generally. For example, we made the decision to focus only on peer-reviewed, published literature. Additional data surely exists in unpublished program evaluations and reports as well as in other grey literature. We did not pursue a search of the grey literature as that work can often be difficult to find through a systematic search process, yet we recognize that we likely missed important aspects that would have added to our findings. We also only reviewed English-language journal articles and considered only empirical work. Studies in other languages and theoretical papers would certainly contribute additional data and perspectives. As in all systematic reviews, we were limited in our data to the information provided and reported on by the authors of each study. Finally, the inherent nature of systematic reviews and the rapid growth in research on the intersection of environmental education and civic engagement means that there most assuredly have been additional, relevant studies published since the end of our search period.

Implications for research and practice

Knowing the types of civic engagement-related outcomes that have been studied in environmental education yields multiple benefits: Such data can help inform a research agenda for the intersection of environmental and civic engagement, assist practitioners wishing to develop and implement programs that support civic engagement, and provide evidence of environmental education’s impact on civic-engagement-related outcomes.

Conducting a systematic review frequently results in illumination of questions ripe for exploration in research. Working with the data in our review, emergent questions included: What does civic engagement look like in different parts of the world, and how does this impact environmental education programs? How can environmental education support civic engagement around issues of environmental justice and provide opportunities for civic engagement in identified civic deserts (Atwell, Bridgeland, and Levine Citation2017; Kawashima-Ginsberg and Sullivan Citation2017)? How do different theories and conceptualizations of environmental citizenship, sustainability, and civic engagement influence the ways in which environmental education contributes to civic engagement? While only six studies reported measures of direct civic engagement (coded as civic action in this study), within those studies we saw diversity in the way researchers are defining civic engagement—reported civic engagement included all four of the civic engagement dimensions presented by Adler and Goggin (Citation2005): community service, collective action, political involvement, and social change. Future review work could focus on the implications of how different ways of defining civic engagement impact environmental education programs. Finally, after conducting several systematic reviews in the environmental education field, we urge researchers to include as much information as possible about program strategies, outcomes, and contexts when describing their studies in the empirical literature. Complete information about programs and initiatives under study aids in future reviews as well as other efforts to coalesce the comparative, synthetic evidence base in environmental education and related fields.

Our systematic mixed studies review also suggests several implications for environmental education practitioners. Our findings of a range of civic-engagement related outcomes provides support for educators as they promote the interdisciplinarity of environmental education. Although often relegated to science education and science-related settings, such as science museums and classrooms, the clear connection to civic education bolsters arguments for robust environmental education curricula in social studies classrooms and civic education themes in everyday settings and contexts. Including and emphasizing civic-engagement related outcomes in environmental education can advance the field of environmental education in its quest to be more inclusive and progressive. Interdisciplinarity can be viewed as more than bridging academic subjects like science and social studies, an interdisciplinary lens can mean engaging with practices and movements such as environmental justice, social justice, and critical pedagogy (Cole Citation2007).

We call for expanded work with and focused on older adults, as the majority of reported participants in this review were youth or young adults. Yet, intergenerational and lifelong environmental learning has been spotlighted as offering rich opportunities for engagement (Ardoin and Heimlich Citation2021). Moreover, the most effective programs in connecting environmental and civic education processes and outcomes appear to be those involving longer timeframes. Although this may be daunting in terms of resources (including funding, staffing, and time), rather than having to develop and fund long-term programs alone, practitioners might consider creatively partnering with organizations throughout a community-wide network to expand lifelong exposure to environmental and civic education concurrently (Wojcik, Ardoin, and Gould Citation2021).

Our hope is that these review findings might assist in illuminating a vision of environmental education not only as a path to enhancing attitudes, knowledge, and skills for protecting and conserving the environment, but also to build social cohesion and community connectedness. Through such processes, we might, as Ehrlich (Citation2000, vi) says, ‘make a difference in the civic life of our communities’ and work to build a more equitable and sustainable environmental future, as well.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to eeWORKS advisors for their insights during study conceptualization. We appreciate the research assistance provided by numerous Stanford Social Ecology Lab members, especially Brennecke Gale, Pari Ghorbani, and Archana Kannan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nicole M. Ardoin

Nicole M. Ardoin Emmett Faculty Scholar, is an associate professor in the Social Sciences Division of the Doerr School of Sustainability at Stanford University. She is the Sykes Family Faculty Director of the Emmett Interdisciplinary Program in Environment and Resources and a senior fellow in the Woods Institute for the Environment. Nicole’s scholarship focuses on individual and collective engagement in sustainability behaviors, as well as people’s connections to place(s) and the ways in which those influence their relationships to each other, their communities, and the natural world.

Alison W. Bowers

Alison W. Bowers is a senior research associate in the Social Ecology Lab at Stanford University. Her research interests include research design and methods, with a focus on research reviews, qualitative analysis, and grounded theory methodology.

Estelle Gaillard

Estelle Gaillard is a consulting researcher with the Social Ecology Lab where she collaborates on a number of research projects. She is also a researcher and consultant with university faculty and organizations in Australia working on sustainability issues. Estelle’s research interests include environmental and social learning, citizen science, and climate change education and communication.

References

- Adamou, A., Y. Georgiou, D. Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, and A. C. Hadjichambis. 2021. “Environmental Citizen Science Initiatives as a Springboard towards the Education for Environmental Citizenship: A Systematic Literature Review of Empirical Research.” Sustainability 13 (24): 13692. doi:10.3390/su132413692.

- Adler, R. P., and J. Goggin. 2005. “What Do we Mean by “Civic Engagement”?” Journal of Transformative Education 3 (3): 236–253. doi:10.1177/1541344605276792.

- Aguilar, O. 2018. “Toward a Theoretical Framework for Community EE.” The Journal of Environmental Education 49 (3): 207–227. doi:10.1080/00958964.2017.1397593.

- Alkaher, I., and D. Gan. 2020. “The Role of School Partnerships in Promoting Education for Sustainability and Social Capital.” The Journal of Environmental Education 51 (6): 416–433. doi:10.1080/00958964.2020.1711499.

- Alkaher, I., and T. Tal. 2014. “The Impact of Socio-Environmental Projects of Jewish and Bedouin Youth in Israel on Students’ Local Knowledge and Views of Each Other.” International Journal of Science Education 36 (3): 355–381. doi:10.1080/09500693.2013.775610.

- Ampuero, D., C. E. Miranda, L. E. Delgado, S. Goyen, and S. Weaver. 2015. “Empathy and Critical Thinking: Primary Students Solving Local Environmental Problems through Outdoor Learning.” Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning 15 (1): 64–78. doi:10.1080/14729679.2013.848817.

- Arai, S., and A. Pedlar. 2003. “Moving Beyond Individualism in Leisure Theory: A Critical Analysis of Concepts of Community and Social Engagement.” Leisure Studies 22 (3): 185–202. doi:10.1080/026143603200075489.

- Ardoin, N. M., and A. W. Bowers. 2020. “Early Childhood Environmental Education: A Systematic Review of the Research Literature.” Educational Research Review 31: 100353. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100353.

- Ardoin, N. M., A. W. Bowers, and E. Gaillard. 2020. “Environmental Education Outcomes for Conservation: A Systematic Review.” Biological Conservation 241: 108224. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108224.

- Ardoin, N. M., A. W. Bowers, N. W. Roth, and N. Holthuis. 2018. “Environmental Education and K-12 Student Outcomes: A Review and Analysis of Research.” The Journal of Environmental Education 49 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/00958964.2017.1366155.

- Ardoin, N. M., A. W. Bowers, and M. Wheaton. 2022. “Leveraging Collective Action and Environmental Literacy to Address Complex Sustainability Challenges.” Ambio 1–15. doi:10.1007/s13280-022-01764-6.

- Ardoin, N. M., C. Clark, and E. Kelsey. 2013. “An Exploration of Future Trends in Environmental Education Research.” Environmental Education Research 19 (4): 499–520. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.709823.

- Ardoin, N. M., and J. E. Heimlich. 2021. “Environmental Learning in Everyday Life: Foundations of Meaning and a Context for Change.” Environmental Education Research 27 (12): 1681–1699. doi:10.1080/13504622.2021.1992354.

- Artun, H., and T. Özsevgeç. 2018. “Influence of Environmental Education Modular Curriculum on Academic Achievement and Conceptual Understanding.” International Electronic Journal of Environmental Education 8 (2): 150–171.

- Atwell, M. N., B. Stillerman, and J. M. Bridgeland. 2021. Civic health index 2021: Citizenship during crisis. Civic. https://www.civicllc.com/_files/ugd/03cac8_9d6c072c6df948ff9e003424f51437b2.pdf

- Atwell, M. N., J. M. Bridgeland, and P. Levine. 2017. Civic deserts: America’s civic health challenge. National Conference on Citizenship. https://www.ncoc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/2017CHIUpdate-FINAL-small.pdf

- Ballard, H. L., and J. M. Belsky. 2010. “Participatory Action Research and Environmental Learning: Implications for Resilient Forests and Communities.” Environmental Education Research 16 (5–6): 611–627. doi:10.1080/13504622.2010.505440.

- Ballard, P. J., L. T. Hoyt, and M. C. Pachucki. 2019. “Impacts of Adolescent and Young Adult Civic Engagement on Health and Socioeconomic Status in Adulthood.” Child Development 90 (4): 1138–1154. doi:10.1111/cdev.12998.

- Balsano, A. B. 2005. “Youth Civic Engagement in the United States: Understanding and Addressing the Impact of Social Impediments on Positive Youth and Community Development.” Applied Developmental Science 9 (4): 188–201. doi:10.1207/s1532480xads0904_2.

- Baum, S. D., D. D. Aman, and A. L. Israel. 2012. “Public Scholarship Student Projects for Introductory Environmental Courses.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 36 (3): 403–419. doi:10.1080/03098265.2011.641109.

- Bencze, L., E. Sperling, and L. Carter. 2012. “Students’ Research-Informed Socio-Scientific Activism: Re/Visions for a Sustainable Future.” Research in Science Education 42 (1): 129–148. doi:10.1007/s11165-011-9260-3.

- Bennion, E. A., and X. E. Laughlin. 2018. “Best Practices in Civic Education: Lessons from the Journal of Political Science Education.” Journal of Political Science Education 14 (3): 287–330. doi:10.1080/15512169.2017.1399798.

- Berkowitz, A. R., M. E. Ford, and C. A. Brewer. 2005. “A Framework for Integrating Ecological Literacy, Civics Literacy, and Environmental Citizenship in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education and Advocacy: Changing Perspectives of Ecology and Education 227: 66.

- Birdsall, S. 2010. “Empowering Students to Act: Learning about, through and from the Nature of Action.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 26: 65–84. doi:10.1017/S0814062600000835.

- Bouillion, L. M., and L. M. Gomez. 2001. “Connecting School and Community with Science Learning: Real World Problems and School-Community Partnerships as Contextual Scaffolds.” Journal of Research in Science Teaching 38 (8): 878–898. doi:10.1002/tea.1037.

- Brabant, M., and D. Braid. 2009. “The Devil is in the Details: Defining Civic Engagement.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 13 (2): 59–88.

- Braus, J. 2020. “Civic and Environmental Education: Protecting the Planet and Our Democracy.” In Democracy Unchained: How to Rebuild Government for the People, edited by D. Orr, A. Gumbel, B. Kitwana, and W. Becker, 183–195. New York: The New Press.

- Brulle, R. J. 2010. “From Environmental Campaigns to Advancing the Public Dialog: Environmental Communication for Civic Engagement.” Environmental Communication 4 (1): 82–98. doi:10.1080/17524030903522397.

- Campbell, D. E. 2019. “What Social Scientists Have Learned about Civic Education: A Review of the Literature.” Peabody Journal of Education 94 (1): 32–47. doi:10.1080/0161956X.2019.1553601.

- Center for Information & Research on Civic Learning and Engagement. 2022. Why Is Youth Civic Engagement Important? CIRCLE. https://circle.tufts.edu/understanding-youth-civic-engagement/why-it-important

- Chawla, L., and D. F. Cushing. 2007. “Education for Strategic Environmental Behavior.” Environmental Education Research 13 (4): 437–452. doi:10.1080/13504620701581539.

- Cincera, J., B. Valesova, S. Krepelkova, P. Simonova, and R. Kroufek. 2019. “Place-Based Education from Three Perspectives.” Environmental Education Research 25 (10): 1510–1523. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1651826.

- Clegg, T., C. Boston, J. Preece, E. Warrick, D. Pauw, and J. Cameron. 2020. “Community-Driven Informal Adult Environmental Learning: Using Theory as a Lens to Identify Steps toward Concientización.” The Journal of Environmental Education 51 (1): 55–71. doi:10.1080/00958964.2019.1629380.

- Cohen, A. K., J. C. Fitzgerald, A. Ridley-Kerr, E. Maker Castro, and P. J. Ballard. 2021. “Investigating the Impact of Generation Citizen’s Action Civics Education Program on Student Academic Engagement.” The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas 94 (4): 168–180. doi:10.1080/00098655.2021.1927942.

- Cole, A. G. 2007. “Expanding the Field: Revisiting Environmental Education Principles through Multidisciplinary Frameworks.” The Journal of Environmental Education 38 (2): 35–45. doi:10.3200/JOEE.38.1.35-46.

- Crittenden, J., and P. Levine. 2018. Civic education. In The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Fall 2018), edited by E. N. Zalta. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/civic-education/

- Delli Carpini, M. X. 2000. “Gen.com: Youth, Civic Engagement, and the New Information Environment.” Political Communication 17 (4): 341–349. doi:10.1080/10584600050178942.

- Den Broeder, L., J. Devilee, H. Van Oers, A. J. Schuit, and A. Wagemakers. 2018. “Citizen Science for Public Health.” Health Promotion International 33 (3): 505–514. doi:10.1093/heapro/daw086.

- Dimick, A. S. 2012. “Student Empowerment in an Environmental Science Classroom: Toward a Framework for Social Justice Science Education.” Science Education 96 (6): 990–1012. doi:10.1002/sce.21035.

- Dittmer, L., F. Mugagga, A. Metternich, P. Schweizer-Ries, G. Asiimwe, and M. Riemer. 2018. “We Can Keep the Fire Burning”: Building Action Competence through Environmental Justice Education in Uganda and Germany.” Local Environment 23 (2): 144–157. doi:10.1080/13549839.2017.1391188.

- Dobson, A. 2007. “Environmental Citizenship: Towards Sustainable Development.” Sustainable Development 15 (5): 276–285. doi:10.1002/sd.344.

- Dresner, M., and J. S. Blatner. 2006. “Approaching Civic Responsibility Using Guided Controversies about Environmental Issues.” College Teaching 54 (2): 213–220. doi:10.3200/CTCH.54.2.213-220.

- Dresner, M., C. Handelman, S. Braun, and G. Rollwagen-Bollens. 2014. “Environmental Identity, Pro-Environmental Behaviors, and Civic Engagement of Volunteer Stewards in Portland Area Parks.” Environmental Education Research 21 (7): 991–1010. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.964188.

- DuBois, B., M. E. Krasny, and J. G. Smith. 2018. “Connecting Brawn, Brains, and People: An Exploration of Non-Traditional Outcomes of Youth Stewardship Programs.” Environmental Education Research 24 (7): 937–954. doi:10.1080/13504622.2017.1373069.

- Dubowitz, T., C. Nelson, S. Weilant, J. Sloan, A. Bogart, C. Miller, and A. Chandra. 2020. “Factors Related to Health Civic Engagement: Results from the 2018 National Survey of Health Attitudes to Understand Progress towards a Culture of Health.” BMC Public Health 20 (1): 635. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08507-w.

- Edwards, B., and M. W. Foley. 1997. “Civil Society and Social Capital beyond Putnam.” American Behavioral Scientist 42 (1): 124–139. doi:10.1177/0002764298042001010.

- Eflin, J., and A. L. Sheaffer. 2006. “Service-Learning in Watershed-Based Initiatives: Keys to Education for Sustainability in Geography?” Journal of Geography 105 (1): 33–44.

- Ehrlich, T. 2000. Civic Responsibility and Higher Education. Illustrated edition. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Ekenga, C. C., N. Sprague, and D. M. Shobiye. 2019. “Promoting Health-Related Quality of Life in Minority Youth through Environmental Education and Nature Contact.” Sustainability 11 (13): 3544. doi:10.3390/su11133544.

- Ekman, J., and E. Amnå. 2012. “Political Participation and Civic Engagement: Towards a New Typology.” Human Affairs 22 (3): 283–300. doi:10.2478/s13374-012-0024-1.

- Fitzgerald, J. C., A. K. Cohen, E. Maker Castro, and A. Pope. 2021. “A Systematic Review of the Last Decade of Civic Education Research in the United States.” Peabody Journal of Education 96 (3): 235–246. doi:10.1080/0161956X.2021.1942703.

- Flanagan, C., and P. Levine. 2010. “Civic Engagement and the Transition to Adulthood.” The Future of Children 20 (1): 159–179.

- Flanagan, C., E. Gallay, and A. Pykett. 2021. “Urban Youth and the Environmental Commons: Rejuvenating Civic Engagement through Civic Science.” Journal of Youth Studies 25 (6): 692–708. doi:10.1080/13676261.2021.1994132.

- Fraser, J., R. Gupta, and M. E. Krasny. 2015. “Practitioners’ Perspectives on the Purpose of Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 21 (5): 777–800. doi:10.1080/13504622.2014.933777.

- Gallay, E., L. Marckini-Polk, B. Schroeder, and C. Flanagan. 2016. “Place-Based Stewardship Education: Nurturing Aspirations to Protect the Rural Commons.” Peabody Journal of Education 91 (2): 155–175. doi:10.1080/0161956X.2016.1151736.

- Gibbs, L., K. Block, G. Ireton, and E. Taunt. 2018. “Children as Bushfire Educators—"Just Be Calm, and Stuff like That.” Journal of International Social Studies 8 (1): 86–112.

- Gough, D., S. Oliver, and J. Thomas. 2017. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Green, C., W. Medina-Jerez, and C. Bryant. 2016. “Cultivating Environmental Citizenship in Teacher Education.” Teaching Education 27 (2): 117–135. doi:10.1080/10476210.2015.1043121.

- Griswold, W. 2017. “Creating Sustainable Societies: Developing Emerging Professionals through Transforming Current Mindsets.” Studies in Continuing Education 39 (3): 286–302. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2017.1284054.

- Guilfoile, L., and B. Delander. 2014. Guidebook: Six proven practices for effective civic learning. Education Commission of the States. http://www.ecs.org/clearinghouse/01/10/48/11048.pdf