Abstract

The remarkably growing body of academic literature on the university in relation to sustainability pivots around the idea that the university has an important role to play regarding this issue. However, which role this precisely is and what type of university this requires is often left implicit. This article presents an empirical analysis of how the idea of the “sustainable university” – understood as any notions of an existing or desirable future university that engages with sustainability – is discursively constructed in 4584 scientific publications on the topic. Through a combination of a discourse analysis with the content analysis tool topic modelling, three discourses on the sustainable university are discerned: the sustainable higher education institution, the engaged community, and the green-tech campus, providing the groundwork for further research and debate on what the sustainable university could be and should be.

Introduction

In the remarkably growing literature on the university – sustainability nexus (see e.g. Hallinger & Chatpinyakoop, Citation2019), universitiesFootnote1 are often regarded as a crucial actor in society’s strive towards sustainable development: It is for example said that higher education has an unavoidable responsibility to engage with sustainability challenges (Gale, Davison, Wood, Williams, & Towle, Citation2015) and that the university would even be ‘morally culpable if it did not do everything in its power to address these [sustainability] challenges’ (McCowan, Citation2018, p. 286). This responsibility can also be related to observations of how the university has contributed to the present state of the planet (Howlett, Ferreira, & Blomfield, Citation2016), implying it has the responsibility to also play a role in solving it.

While there seems to be somewhat of an academic consensus about the importance of universities engaging with sustainability, the academic debate displays a wide variety of purposes for universities to do this. To give just a few examples: catalyzing and accelerating a societal transition (Stephens & Graham, Citation2010), reducing campus’ climate-altering emissions (Rappaport & Creighton, Citation2007), reducing energy costs (Horhota, Asman, Stratton, & Halfacre, Citation2014), constructing an institutional identity which helps to find a niche to attract the best students (Bardaglio & Putman, Citation2009), building critical and reflective thinking capacities in students (Howlett et al., Citation2016), contributing ‘graduates who can lead, but not be too far ahead of reality, at the time of graduation’ (Desha & Hargroves, Citation2013, p. 39), or convincing students to change their carbon emitting behavior (Rappaport & Creighton, Citation2007).

These examples not only show different purposes for the university to engage with sustainability, they also imply different views of what a sustainable university actually is or should be. This fits within a larger discussion on the purpose of the university (Gough & Scott, Citation2007), a question the mere listing of the traditional three functions (education, research, service) no longer seems to be able to answer in a satisfactory way (Biesta et al., Citation2009). However, in the academic literature on the university-sustainability nexus, the different views of the university in relation to sustainability are very often left implicit and undertheorized, as emphasized by for example Figueiró and Raufflet (Citation2015) and Shephard, Rieckmann, and Barth (Citation2019). Such a situation does not foster the academic debate, since discussions about a large-scale change of the university towards a ‘sustainable university’ could benefit from having a clear view on the possible and desirable end goals of such a transition (Deleye, Van Poeck, & Block, Citation2019). Possible end goals (i.e. different images of a desirable sustainable university) that each entail a view (or views) of what such a university actually is or should be. This is where the societal contribution of the current article lies: to advance the field’s discussion of possible and desirable end goals of a sustainability transition of higher education by creating a clearer view on how ‘the sustainable university’ is currently understood in the academic debate.

The scientific aim of this study is to contribute to the advancement of knowledge concerning the state of art in the research field by ‘identifying’ discourses on the sustainable university in the relevant scientific literature: In which ways is the sustainable university (re)presented in this body of the literature? The aim is not to summarize or synthesize the field, nor to argue for a specific view of what the sustainable university should be, but to make the different ways in which the sustainable university is understood or approached in the literature more open and sharp, to lay differences and similarities between different discourses bare (cf. Östman, Citation1996), and to provide tools to further discuss the university – sustainability nexus in the field. This allows to provide a groundwork and explore a number of pathways for future research on the topic.

The object of study is the body of the literature on the university – sustainability nexus. Through combining a systematic literature review, a post-structural discourse analysis (Laclau & Mouffe, Citation1985), and topic modelling as data mining technique, this study is able to analyze a substantial sample of 4584 academic publications on the subject. Three discourses on the sustainable university are discerned in an iterative interplay between original data, earlier research and discourse theoretical framework through the use of topic modelling. To the author’s knowledge, it is the first time that discourse theory and topic modelling are combined for a study of academic literature.

In what follows, the study is first situated in the larger academic debate on the university and sustainability. This is done on a meta-level in function of the formulation of sensitizing concepts that serve an important role in the study’s inductive methodology. In the second part, this methodology is explicated in four sections, discussing discourse theory, topic modelling, the topic modelling-discourse theory combination, and the data collection and analysis. This is followed by the results section in which three dominant discourses on the sustainable university are introduced. The discussion section starts off with zooming in on the specific nature of these discourses and on how they are to be understood in relation to the theoretical framework of the study. This is followed by a final discussion of the results of the study in function of an exploration of pathways for future research for which this study is intended as a first step.

The sustainable university

While the amount of the literature on the university – sustainability nexus is increasing rapidly, the field of study focusing on the topic is still rather novel (Alejandro-Cruz, Rio-Belver, Alamnza-Arjona, & Rodriguez-Andara, Citation2019). The field has repeatedly been described as having a general lack of conceptual clarity and theoretical thoroughness. Figueiró and Raufflet (Citation2015), for example, state that most articles about sustainability in management education are descriptive, lack consistency in the conceptual framework, and lack reference to educational theory. Lambrechts, Van Liedekerke, and Van Petegem (Citation2018) discuss the field as in lack of philosophical grounding. Viegas et al. (Citation2016) describe the literature as having an ‘existing lack of depth and comprehensiveness’ regarding the essential attributes of the sustainable university. Shephard et al. (Citation2019) state that miscommunication, internal contradictions, inconsistencies, and misunderstandings of basic concepts (such as ‘competence’ and ‘capability’) are a big problem in the field and need to be addressed.

In a response to this, the present article aims to contribute to the field of research by studying how ‘the sustainable university’ – arguably the most central concept or idea of the field – is approached and conceptualized in the academic literature. Sterling and Maxey describe the sustainable university as follows:

[a] university can only contribute fully to a more sustainable future if it becomes more sustainable itself, if it strives and learns to become a sustainable university. Such a university embodies, critically explores and lives sustainability, rather than seeking to deliver it in various discrete curricula or research programmes without reference to its own ethos, practices and operations. (Sterling & Maxey, Citation2013, p. 7, original emphasis)

While the importance of an inductive approach in such an endeavor is emphasized, some theoretical foothold to start off from is necessary. To cater for this need within such an inductive approach, an initial categorization is used as sensitizing concepts (Blumer, Citation1954) for the data analysis of this studyFootnote3. A starting point for this can be found in a recurring theme in the field: the ways in which the university can engage with sustainability. This is usually conceptualized in the form of lists of elements of the university within which attention for sustainability can be integrated. Henderson, Bieler, and McKenzie (Citation2017) discern five domains of the university in which sustainability can be integrated: governance, education, campus operations, research and community outreach. Findler, Schonherr, Lozano, Reider, and Martinuzzi (Citation2019) focus on education, research, outreach, campus operations and campus experiences. Leal Filho (Citation2011) gives five areas of sustainability action: curriculum greening, campus operations, research, extension (i.e. continuing education and further education programs) and concrete projects. Lozano et al. (Citation2015) use seven elements: institutional framework, campus operations, education, research, outreach & collaboration, and on-campus experience. In this study, these approaches were combined to arrive at the framework with six domains of university sustainability engagement in . These lists of domains of university sustainability engagement, each in their own way, build further on the traditional three tasks of the university: education, research and service (e.g. as described by Biesta et al. (Citation2009)) in an attempt to encompass all aspects of the university in which there can be attention for sustainability. Campus projects and student and employee wellbeing are for example very popular in Flemish universities’ attention for sustainability (Lambrechts et al., Citation2018), but are hard to give a place within those classic three tasks.

Table 1. Six domains of university sustainability engagement (sensitizing concepts).

These six domains of university sustainability engagement offer a scope of the areas in which the university can engage with sustainability but do not define in which way or to which extent this happens. In other words: they provide a way of grasping the different things a sustainable university can be about, without pre-defining what this actually might entail, for example by defining how is taught or which (if any) specific learning outcomes are preferred. In doing so, they offer an important groundwork for the remainder of the study and are hence used as sensitizing concepts in step 2 of the analysis (see further).

Discourse theory

This study starts off from a discourse theoretical (DT) perspective, more specifically Laclau and Mouffe’s (Citation1985) post-structural strand. As opposed to many other approaches in discourse studies, their DT uses a macro-textual and macro-contextualFootnote4 definition of discourse as framework of intelligibility (Carpentier, Citation2017). A discourse in DT ‘is a social and political construction that establishes a system of relations between different objects and practices’ (Howarth & Stavrakakis, Citation2000, p. 3). They are concrete systems of social relations and meaningful practices that give meaning to the world. A discourse can best be understood as a particular configuration of connected elementsFootnote5 (i.e. words or phrases) that receive their meaning through their connectedness with each other. Elements are connected and form a relationship through the practice of articulation, understood as any practice that establishes a relation among elements such that their meaning is modified. Through such practices, elements become (or are affirmed) as part of a discourse. Elements receive their specific meaning through their connection with other elements. For example, stating that universities have the responsibility to tackle climate change connects university with responsibility and climate change, altering the meaning of what the university is. In discourses on the university where this connection is not made, the university has a different meaning: it is something else. Elements can thus assume different meanings in different contexts and discourses. Some elements remain particularly open to the ascription of meaning and play an important role in multiple discourses, these are called floating signifiers. Discourses are thus like spider webs, connecting a multitude of elements (some peripheral, some more central) around a center, in which one or several nodal points are located (Jacobs, Citation2018). These nodal points are the central ideas of a discourse, and they define the discourse’s organization and provide it with the necessary stability (Laclau & Mouffe, 1985). Despite the stability of such nodal points, discourses are also inherently instable and contingent. Discourses are continually reproduced and challenged through articulatory practices (Jørgensen & Phillips, Citation2002). This never-ending process implies that discourses in DT are always contingent and structurally open. They are open to change (Doudaki & Carpentier, Citation2019) and vulnerable to re-articulation, while also still to a certain degree fixated and stabilized.

This very brief introduction to DT allows for a rephrasing and elaboration of the original aim of the article as stated in the introduction. This study approaches research on the university – sustainability nexus with a DT lens. This means that the research field is seen as a specific social system (cf. Howarth & Stavrakakis, Citation2000) understood as consisting of different discourses that are continually reproduced and/or challenged through articulations. Scientific publications can be seen as such articulations that confirm or challenge discourses within this specific ‘area’ by connecting particular elements in particular ways. This study focuses on one specific question, that is on how ‘the sustainable university’, that is: a university that engages with sustainability, is discursively constructed in academic publications on the university – sustainability nexus. When understood from a DT perspective, the research field can be characterized by one or several discourses on what the university precisely is or should be. The aim of the study is thus to ‘identify’ such discourses on the sustainable university in the literature by studying how they are constructed around particular nodal points and elements, and looking at how different discursive constellations differ. Since this study is intended to provide the groundwork for a more thorough discussion of what a sustainable university is and should be (as discussed in the introduction section), discourse theory is applied in a rather pragmatic way in function of the development of an analytical toolbox that allows the answering of the central research question. The use of Laclau and Mouffe’s discourse theory in this study is thus mainly limited to their social ontology, building on the vocabulary and mechanics of discourse theory, and consequently does not really go into Laclau and Mouffe’s – what Smith (Citation1999) called – political identity theory as the latter falls beyond the specific scope of this study.

Discourse analyses usually do not allow us to study large corpora. Because of the large size of the studied corpus (i.e. the selected academic publications on the university – sustainability nexus) with its 4584 academic publications (see data collection and analysis section), a content analysis method is necessary to make a discourse analysis possible. Topic modelling serves this purpose and is introduced in the next section.

Topic modelling

Topic modelling (TM) is a powerful automated content analysis method that allows to analyze large corpora (Arora et al., Citation2018; Jaworska & Nanda, Citation2018) by deriving latent meaning from documents. It is a text mining technique based on a probabilistic model and was developed within the field of computer science. The most commonly used algorithm for TM is Latent Dirichlit Allocation, also called Vanilla LDA, (Blei, Ng, & Jordan, Citation2003), which is also the algorithm behind the software used in this studyFootnote6. TM can be regarded as a type of distant reading (as opposed to close reading) (Wiedemann, Citation2013) which means that the power of TM lies in investigating larger patterns over multiple documents and not in studying individual documents in depth. In a nutshell, TM reduces the complexity of a corpus through finding topics: ‘collections of words that have a high probability of co-occurrence and not topics as we understand the term in everyday language’ (Jaworska & Nanda, 2018, p. 11)Footnote7. Topic is thus a slightly misleading term: ‘the interpretation of these clusters [of words] as themes, frames, issues, or other latent concepts (such as discourses) depends on the methodological and theoretical choices made by the analyst’ (Jacobs & Tschötschel, 2019, p. 471). This implies that how these topics should be interpreted is not inherent in TM. TM is in essence merely a technique. I will come back to this later, but first we need to have a closer look at the rationale behind TM.

TM starts from the assumption that documents in the corpus are constructed from a finite set of topics and that the proportions of these topics vary in each document (Jaworska & Nanda, Citation2018). Every single one of these topics is defined by a set of words that are most frequently used in this topic (e.g. a topic on agriculture would contain the words farm, farmer, cow, crops, harvest, profit…). Different topics can have certain words in common (e.g. cow can also be a word in a topic on mammals). This means that, hypothetically speaking, an author first selects the topics she wants to write about, and then uses these topics’ words to write the document. The main goal of TM consequently lies in reversing this hypothetical process by, based on the word frequencies and probabilities of occurrence, discovering the underlying set of topics used to generate the documents in the corpus under analysis (Arora et al., Citation2018). The order of the words in the documents is not important for this process: Documents are approached as so-called ‘bags of words’ (Blei et al., Citation2003).

TM has a number of clear advantages. Through its use of corpora, it makes large-scale analysis possible and allows the study of subtle aspects of language use (Baker, Citation2006). It is a corpus-driven technique, meaning that no pre-set keywords or hypotheses are required: the analysis is based on patterns in the corpus itself. Obviously, this does not leave the researcher without a job (as described below) but TM offers a way to postpone interpretation and forces the researcher to stay close to the data and remain open for empirical surprises.

The outcome of TM is a topic model: a number of topics (with every topic consisting of a list of the most important words in that topic) that together represent the corpus. The definitive topic model is the result of an iterative process between running the TM software, analyzing the output in a back-and-forth movement between topics and documents, changing the software configuration and adapting the data pre-processing. This means that this is not a QUAN→QUAL sequential mixed methods design, but a circular process with an intricate entanglement between the quantitative method and the qualitative analysis. This process is discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Combining topic modelling and discourse theory

Topic modelling is used in this study as a means to enable a discourse analysis of such a large corpus. This implies that the topic modelling does not dominate the analysis; it plays a supporting (albeit crucial) role. This specific role is made possible because of TM and DT’s compatibility. The ‘topics’ in a topic model have no meaning in se. The way to interpret topics stems from the characteristics of the corpus (topics should be interpreted differently whether the corpus consists of, for example, tweets, political speeches, or scientific publications), the research question (what aspects of the topic model are we interested in?), the granularity of the model (a model with the 20 topics will have more general topics than a model with 200 topics), and the theoretical foundation of the study (how to interpret these topics). DT provides such a theoretical foundation and does this in a way that fits with TM’s theoretical underbelly (Jacobs & Tschötschel, Citation2019).

The relation between topics in TM and discourses is not new (e.g. Goldstone & Underwood, Citation2014) but recently Jacobs and Tschötschel (Citation2019) provided theoretical and methodological arguments for combining TM and discourse analysis: First, TM explicitly models polysemy (words can have multiple meanings depending on their context, e.g. chair as a seat, and chair as the chairperson), which is in line with DT’s openness of meaning. Second, TM and DT share the idea of relationality of meaning. While in DT elements derive their meaning from their connectedness to other elements, meaning in TM stems from the co-occurrence of words. For example, in a topic with table, bed, closet and pillow, a chair will be seat while in a topic with words as meeting, director and agenda, a chair will be a chairperson. Meaning arises from the context and is consequently contingent (words in a different context can have a different meaning), which is clearly in line with discourse theory’s non-essentialist perspective.

The combination of TM with DT allows us to meet a number of specific needs of the present study. Identifying discourses preferably requires a highly inductive approach. Furthermore, the selection of the sample should not limit the scope of the study nor exclude less dominant (i.e. non-hegemonic) discourses. However, a large sample should not lead to a superficial analysis. Furthermore, in order to minimize/control researcher bias, a systematic approach is necessary. TM in combination with a DT framework offers a way to cater for these various demands, because the following three conditions (Jacobs & Tschötschel, 2019) are met in this study:

The corpus is thematically coherent (it focuses on one well-delineated meta-subject). The corpus of this study is selected based on its content: All documents are about the university (incl. higher education) AND sustainability.

The corpus is stylistically coherent (it contains texts from one genre). All documents in the corpus of this study are academic publications and thus share a similar writing style.

The overall number of topics in the model is large enough in order to find ‘more fine-grained and nuanced aspects of language use’ to be interpreted as ‘discursive units’: The topic model contains 250 topics.

Data collection and analysis

The object of study consists of academic writings about the university – sustainability nexus. The amount of data in the study had to be as large as possible to let the topic modeling software do its work properly. The collection of such a number of articles was done manually via the database SCOPUS. SCOPUS was preferred over Web of Science and ERIC. The former’s coverage of educational work is less extensive (Hallinger & Chatpinyakoop, Citation2019) and the latter’s focus on educational research would put an undesirable limit on the study. The following search query was used

TITLE (‘higher education’ OR universit* OR campus*) AND (sustainab* OR eco* OR green* OR sdg* OR environmental* OR climate))

The underlying aim of this search query was to find publications that address both the university (or related) and sustainability (or related) in its title, hence the ‘AND’ in the search query. This rationale was based on the study’s focus on the university-sustainability nexus: the intersection of writings on these two topics. A publication was thus included in the study if it was a) about a sustainability issue in relation to the university and thus combined these two themes; b) in English (because all texts in text mining need to be in the same language); and c) an academic publication (which was always the case given the nature of the database). This includes for example publications about teaching about (or for) sustainability in higher education, higher education sustainability policy, university sustainability charters, campus greening (including very technological articles), student behavior etc. This specific search query was selected through trial-and-error and deliberation with colleagues aimed at finding as much relevant publications as possible while minimizing the number of irrelevant publications to be filtered out in order to keep the manual work feasibleFootnote8.

The search yielded 10,264 publications (published before 2022). Because the search query was designed to catch as many relevant publications as possible, the search results still included a large number of irrelevant publications that needed to be excluded. The search results were thus screened based on careful reading of the titles and abstracts to check whether or not a publication is about the relation between a sustainability issue and the university. Given the relational meaning of some keywords, publications on for example organizational climate, sustainable in the sense of ‘durable’, mentions of a university press, mentions of research by or in a university, environment in the non-ecological sense, and economical issues were excluded. The access to publications of two university libraries and availability of publications on ResearchGate was combined. This combination allowed for access to most relevant publications in the SCOPUS search. Relevant publications (based on screening of title and abstract) to which this combination did not provide access were ruled out (less than 500). This was deemed to not give a systematic error or selection bias and consequently, also due to the large size of the corpus, not have an impact on the results of the study. Relevant publications were manually downloaded. The SCOPUS search offered papers, book chapters, and some books. If the entire book was relevant, this was also added. Edited books were cut into chapters which then were treated as individual publications. All relevant articles of two leading journals in the field (Environmental Education Research and International Journal for Sustainability in Higher Education) that were not part of the initial set (i.e. articles about the university and sustainability) were also added. During the pre-processing (see below), a final check of eligibility happened in which 14 extra publications were excluded. This process resulted in a final corpus of 4584 publications.

A number of choices need to be made and tested throughout the process of TM. After the data gathering, the raw data is prepared before the actual TM can start. This is called pre-processing the data, which is a necessary and common step in data mining. presents all pre-processing steps taken. An important step in the pre-processing is the splitting of the documents. Topic modelling does not perform well with long documentsFootnote9. The 4584 publications were thus cut in pieces of maximum 1000 words, leading to a final corpus of 27231 documents. 1000 words are claimed to be a good document size for TM (Jockers & Mimno, Citation2012) and also proved to provide better results than tests with documents with 500, 750 and 1500 words. These split documents were handled by MALLET as separate texts. The actual TM itself (i.e. running the software to make the model) was done in MALLETFootnote10 which uses so-called Vanilla LDA. offers an overview of all TM specifics. The choices reflected in and were partly informed by the literature (as described in this section) and partly the result of running test modelsFootnote11.

Table 2. Overview of the steps in pre-processing of the data in the corpus.

Table 3. Overview of topic modelling specifics.

Although the iterative process of TM and the analysis of the topic model cannot be emphasized enough, the data analysis process can be described as consisting of two analytical phases: (1) the actual TM as described above, and (2) the analysis of the topic model. This second phase entails a number of steps.

The first step is an inductive analysis. Every topic in the topic model is given a descriptive label (or name) that represents the content of that topic. This naming is done based on the words in the topic and by checking the documents in which those topics have a high prevalence. gives an example of a labeled topic: the description is kept as close as possible to the content of the topic and how the words are used in the original documents. The number of the topic (110) has no particular meaning. The words are ordered in descending importance in the topic: ‘curriculum’ has a higher probability of occurrence than ‘courses’ and so on. Besides giving every topic one unique label, the topics are in this step also inductively and descriptively labeled in order to find recurring themes throughout the model. Topic 110, for example, was inductively linked to the themes ‘educational curriculum’, ‘educational structures and institution’, ‘change, integration and transition’, ‘institutionality’, and ‘students’. The aim of this first step is to get a grasp of the ‘aboutness’ of the corpus based on the topic model: What the topics and the model are about.

Table 4. Topic 110.

The second step of the analysis is a categorization of the topic model by using sensitizing concepts. Sensitizing concepts (Blumer, Citation1954) offer a ‘general sense of reference and guidance in approaching empirical instances’ (p. 7). It is a way of explicitly bringing theoretical concepts into the analysis that help the analyst by pointing at what to look for and where to look (Bowen, Citation2006; Carpentier & De Cleen, Citation2007; Ritzer, Citation2000) without determining what to see. The six domains of university sustainability engagement introduced in the second section are used in this study as such sensitizing concepts. They offer a way of structuring different foci in the literature on the university in relation to sustainability without determining how these foci are specifically approached. This renders these domains ideal as sensitizing concepts: They offer discriminatory principles for categorization without defining how the content of the categories will be approached. This categorization is not exclusive: The six domains were not ‘forced’ upon the topic model which means that one topic could be placed in multiple categories. shows topic 196 which was placed in the domains education and institutional.

Table 5. Topic 196.

The third step is to look for similarities and differences (cf. Östman, Citation1996) within the domains of university sustainability engagement. This process is aided by the inductive analysis of the first step. For example, the topics that belong to the domain of education (55 topics) are studied in order to find different clusters that approach education in a different way. In this example, two such coherent clusters were found, which are presented in the results section as ‘education as accumulation’ and ‘education as change’. A query matrix in Nvivo in which the themes of step 1 and the domains of step 2 are combined plays an important starting point in this process. It allows for example to zoom in on how students (as a theme) are articulated across different domains (education, research, campus operations…). This means that in this step the themes from step 1 offer some guidance regarding what to see within and between the six domains (step 2).

Step four uses steps two and three as a starting point to discern coherent discourses on the sustainable university. In this step the discourse-theoretical framework of the study offers a specific way in which to understand how discourses are structured (i.e. as a web of connected elements around nodal points). Every element in the discourses (see results section) matches with the label of a topic (cf. step 1) or a word that recurs in multiple topics with a similar focus. Which elements are connected stems from whether topics articulate a relation between the elements (i.e. co-occurrence in a way that is meaningful in relation to the discourse), and similar words that are used in related topics. The same topic can be a part of multiple discourses but play a different role in these discourses because of a different structuration and different connectedness to other elements. Which elements can be regarded as nodal points (grey ellipses in visualizations below) is decided based on the centrality of elements in the discourse, the number of connections to other important elements, and the importance the element has for the overall meaning of the discourse. For example: ‘research’ in the third discourse (see results section) is rather in the periphery and has four connections to other elements but it is important in how to understand the entire discourse, as is described in the results section.

Results: Three discourses on the sustainable university

The topic modelling-assisted discourse analysis allows to discern three dominant ways in which the sustainable university is understood in the academic literature on the topic. The three discourses on the sustainable university are (1) the sustainable higher education institution, (2) the engaged community, and (3) the green-tech campus. In the overview below, these discourses are represented and discussed as specific constellations of concepts (i.e. elements). None of the discourses presents the sustainable university as a combination of the 6 domains of university sustainability engagement discussed above: Every discourse focuses on some of these domains and does this in a particular way.

The sustainable higher education institution

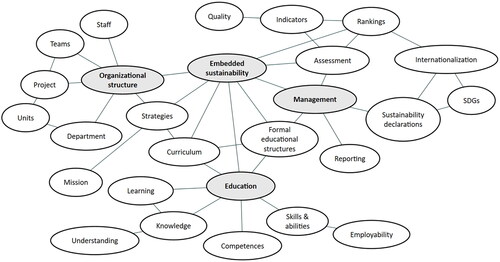

In the discourse of the sustainable higher education institution, the sustainable university is primarily understood as an institution in which attention for sustainability is embedded or integrated. Education and the institutional framework are the crucial domains of the university in this discourse (see ). The discourse centers around the nodal points ‘education’, ‘organizational structure’, ‘management’, and ‘embedded sustainability’ (see the discursive constellation in ).

The first nodal point, education, plays an important role in this discourse, but it appears in a specific way. It is clearly articulated in relation to a very specific jargon: gathering knowledge, competences, skills and abilities. In this sense education might be described with the metaphor of accumulation: learning is accumulating knowledge, skills etc. Education is also understood as part of a formal educational structure (e.g. programs, courses, levels, assessment…) and in close relation to the curriculum. This implies that sustainability is institutionally embedded in education through the official curriculum.

The second nodal point of this discourse is the organizational structure of the institution: The sustainable university is primarily understood and approached as an organizational structure consisting of distinct and separable entities: departments, teams, units, projects etc. This is closely related to the element ‘strategies’ and also to ‘embedded sustainability’, implying that sustainability is embedded in all layers of this organizational structure via specific strategies.

Management forms a third nodal point in this discourse. It is central in the discourse and is articulated in relation to education through the formal educational structures. Also (sustainability) reporting is related to management. It is noteworthy that the main external focus of this discourse is via the cluster of elements around management: via rankings, sustainability declarations, internationalization, and the Sustainable Development Goals there is a clear connection with what happens beyond the university walls, but the attention remains internal. This also shows how the international aspect of this discourse is rather formal and (in line with the discourse as a whole) institutional. The management nodal point is via assessment also linked with indicators, quality and rankings which again shows a managerial jargon.

The fourth nodal point of the discourse is positioned at the center of the discursive constellation in : embedded sustainability. This is the only nodal point of the discourse that is connected to the three other nodal points, which implies that it is very important in how we should understand the sustainable university in this discourse. Sustainability is embedded into the internal workings of the university. This means that the primary attention for sustainability is internal and not external. Sustainability is brought into the university. This notion of the integration or embedding of sustainability is far from this overtly and explicitly present in the next two discourses.

The focus on the domains of education and institutional framework implies that four of the domains of university sustainability engagement are excluded from this discourse. According to this discourse, the sustainable university is primarily an education institution, research is not relevant in this picture. The campus (as material entity) and what happens on campus are also not essential to what makes this university sustainable. Finally, the domain outreach & collaboration is also absent from this discursive constellation: the attention for sustainability is pointed inwards. This does not mean that this sustainable university does not have a campus, has no campus life, does not perform any research, and has no outreach beyond its walls; it means that these things are not relevant to what makes a university sustainable. A university is only a sustainable university if sustainability is embedded in its organization and curriculum in an institutionalized way.

The engaged community

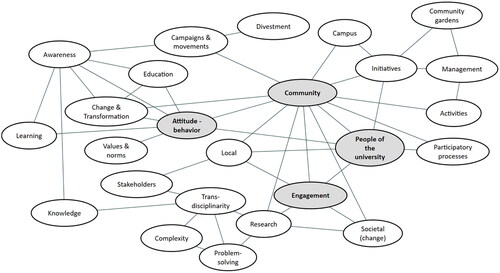

The engaged community discourse presents the sustainable university as a community of people that is engaged with sustainability. This engagement can be both directed inwards (campus and its inhabitants) as outwards (i.e. the local community). This discourse focuses on four of the six domains of university sustainability engagement: on-campus experience, outreach & collaboration, education, and research. The discursive constellation (see ) is centered around the nodal points ‘community’, ‘people of the university’, ‘attitude & behavior’, and ‘engagement’.

The most central nodal point of this discourse is community, which implies that this sustainable university is mainly to be understood as an engaged group of people that is involved in initiatives, activities, research, campaigns and movements. Participatory processes play a role in these engagements. This group of people has (or aims at) a shared attitude and behavior, and is engaged towards (local) sustainability issues and societal change. Management, a nodal point in the first discourse, appears in this discourse as element in the periphery of the cluster around community, and is only related to activities and initiatives, of which the community gardens are an example that often reappears in the literature. Because of this location in the margins and the fact that it only has connections to these three, more practical elements, management can thus be understood as having a more marginal, practical and less determining meaning in this discourse than in the first one. Campus, something that was absent in the first discourse, also appears in the periphery of this community cluster, but in a community-campus-initiatives triangle, which implies that it only comes in the picture as the object of initiatives. The element campaigns and movements relate the community with two other elements which can be interpreted as popular goals: awareness (for sustainability issues), and (fossil fuel) divestment.

The second nodal point is people of the university, which entails mentions throughout the corpus of professors, teachers, faculty, students, etc. in relation to initiatives, participatory processes, the university community, engagement, and the local. This nodal point shares all its connections with the community nodal point but is important to underline the difference between this and the first discourse. Together with the nodal point community it provides a stark contrast to the nodal point organizational structure of the first discourse. While in the first discourse, the sustainable university is understood as an organizational structure, here it is a community of people.

The third nodal point of this discourse is engagement. Engagement is on the one hand connected to community and people of the university: this sustainable university primarily consists of an engaged community of people. This engagement is oriented towards sustainability issues in general, but has an articulated focus on societal change and local challenges. Research also plays a role in this engagement, but a very particular understanding of research: transdisciplinary research, with (local) stakeholders, problem-solving and with attention for complexity.

The last nodal point, attitude & behavior, is closely related to the educational. It also connects to what happens on campus through its connections to community and, especially, people of the university. This means that this nodal point should not only be understood as an educational outcome or point of interest, but also as desirable towards other people of the university: staff’s attitude and behavior is also important in this discourse. Education in this discourse comes to the fore in an entirely different way as in the first discourse, whereas education in the first discourse can be described as accumulation, education in this discourse can be understood as closely related to change in a multitude of ways: change of behavior, change of attitude, transformative learning, critical thinking, critical reflection… Knowledge plays a role in this endeavor, but does this through the concept of awareness, in connection to learning. Knowing can thus be interpreted as being aware (of sustainability issues, for example). Discussions of values and norms are also related to the educational in this discourse, as part of the focus on attitude & behavior.

The central domain on which this discourse focuses is the on-campus experience. The whole discourse pivots around this. Education, research and outreach & collaboration can be seen as derivates from this central domain. However, the gaze is less pointed inwards than in the first discourse. Through engaged research, attention for the local community, and a focus on societal change, this sustainable university aims to reach out into society. Two domains are absent in this discourse. There is barely no explicit attention for campus operations in this discursive constellation. This does not mean that this sustainable university does not have a physical infrastructure, but that it is not the primary focus of the discourse. Campus operations, for example, might be the subject of initiatives and campaigns within the sustainable university, but this makes them into a secondary focus. What makes a university sustainable according to this discourse is its community, not the sustainability of its campus, nor the integration of sustainability in its curriculum.

The green-tech campus

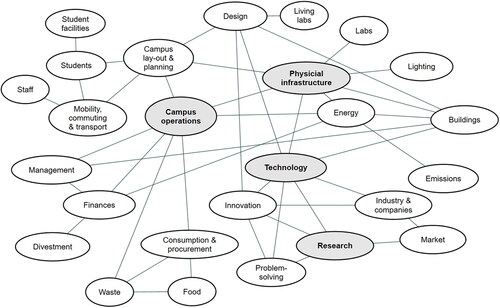

The third discourse on the sustainable university is that of the green-tech campus. This discourse can best be understood as a combination of two sub-discourses: a greening the campus discourse and a discourse in which the university is primarily seen as the creator of technological innovations. These two sub-discourses reinforce each other into a primarily material understanding of what a sustainable university is about. This combined discourse focuses on three domains: campus, research, and outreach and collaboration. It is centered around the nodal points campus operations, physical infrastructure, technology and research.

The nodal points campus operations and physical infrastructure together form this discourse’s focus on the green campus. Campus operations is understood as encompassing a whole range of related aspects, such as campus management, consumption and procurement at and of the university, waste, finances of the university (with a link to divestment, as discussed in the previous discourse), and energy. The physical infrastructure nodal point is related to campus operations, but is discussed in the literature in relation to themes such as buildings, labs, lighting, and energy. The elements energy and campus lay-out & planning are connected to both nodal points, which makes sense since both are related to what happens (campus operations) and where it happens (the physical infrastructure). It is only via campus lay-out & planning in relationship to mobility, commuting & transport (top right of ) that students and staff come in the picture, albeit as users of the campus.

The nodal point research in this discourse is connected to the greening the campus nodal points via innovation and technology. This shows that research here is entirely differently articulated than in the engaged community discourse. Although it also has an outwards focus that can be understood as societal outreach and collaboration (problem-solving, the market, industry & companies…), its aim is to improve or find new sustainable technologies. The connection to problem-solving was also present in the second discourse, but here it has a different meaning: it is related to innovation and technology, and not to complexity and transdisciplinarity as in the second discourse. Problem-solving is thus solving technological (or technologically understood) problems through innovation. This understanding of research in relation to technology and the market is mirrored in an understanding of the university campus as a physical and optimizable infrastructure. The university campus can be seen as an important place where this research and technology can be applied to. The university is, besides a place where this research takes place, thus also a place that has to be optimized itself (and that can function as a testing ground). This specific application is articulated in relation to the important elements ‘energy’, ‘physical infrastructure’, ‘campus lay-out & planning’, and ‘consumption & procurement’.

This makes the university a very material place, whereas the other discourses understand the sustainable university respectively primarily as an institution or a community, the university is here primarily a material entity that has to be sustainable in itself. This implies that sustainability is not embedded in the university, but that the university as material entity is made sustainable.

The green-tech campus pivots around the domains campus, research, and outreach & collaboration. On-campus experience is not in the picture in this discourse. This can be explained by the dominance of technology in this discourse, which draws attention away from this ‘softer’ issue. Education is absent from this discourse as well. Students play a role, but only in the periphery of the discourse as commuters and users of the campus facilities and infrastructure. This should not be understood as a claim that authors who adhere to this discourse believe education has no place in the university. It does imply, however, that education does not have an important place in how the sustainable university is discussed. What makes a university sustainable is its research and campus operations, not its education.

Discussion

By means of a topic modelling-assisted discourse analysis of the literature on the university-sustainability nexus, this study shows that (1) the sustainable university can be conceptualized in many different ways, and (2) that three such conceptualizations – or discourses – of the sustainable university are dominant in the academic debate on the topic: the sustainable higher education institution, the engaged community, and the green-tech campus. The discussion section first zooms in on how these three discourses are to be interpreted. This is followed by a more substantive discussion of the three discourses as part of an exploration of pathways for future research for which this study aims to provide some groundwork. This exploration consists of two steps: First, the three discourses are discussed with a focus on similarities and differences between them. Second, the discourses are connected to existing conceptual (non-sustainability related) frameworks on higher education that are relevant for the results of this study and offer some direction for further research.

Interpreting the discourses

Before entering into a substantive discussion of the discourses, it is important to first zoom in on the nature of these discourses, that is: what they actually are, how they are to be interpreted, how they allow to understand the current academic debate, and how they relate to what happens in the actual university (i.e. existing universities and university practices and policy in relation to sustainable development). Besides being a necessary step to facilitate a substantive discussion of the discourses, this also provides valuable further insights into the implications of this study’s TM/DT methodology.

Approaching the research field as a specific social system from a discourse theoretical perspective (cf. Howarth & Stavrakakis, Citation2000) implies that it is understood as consisting of different discourses that are continually reproduced and/or challenged through articulations, i.e. academic publications. Every publication is thus to be seen as such an articulation that reproduces and/or challenges particular discourses on what a sustainable university actually is. This also means that, via the topic modelling, the discourses are derived from what is written in publications. The discourses’ elements and specific configurations as described in the results section are thus derived from what authors in the field focus on in their writing, or in other words: what makes a university a sustainable university. However, the three discourses do not form a typology to categorize all publications in the field. There is not necessarily a one-to-one connection between individual publications and these discourses. On the one hand, individual publications can address and represent one specific discourse, but can also address only a specific aspect, nodal point or element of a discourse. A publication does not per se articulate a discourse in its entirety (i.e. all the elements of the discursive constellation). This is where the topic modelling also proves its value in this study: through finding topics first, TM allows to combine aspects of different articulations into coherent discourses throughout a large corpus. The three discourses as presented above are thus to be understood as generalized and abstracted to a large extent. The study started off from 4584 publications, so individual publications contain more detail than the three discourses suggest. On the other hand, individual publications can also challenge a discourse, by adhering to another one of the three discourses, but also by articulating alternative connections and thus opening up for new potential discursive constellations. This implies that the three discourses on the sustainable university as presented in the results section are the dominant discourses, not necessarily the only (possible) discourses. They were the ones that were strong or dominant enough within the corpus to be caught by the topic modelling approach, and hence also the ones that dominate how the sustainable university is understood in the field. It also does not mean that alternative conceptions of the sustainable university do not exist outside this specific social system.

This understanding of the discourses in relation to individual publications allows us to make some methodological comments about the specifics of a TM/DT approach for reviewing the academic literature. In this approach, it is irrelevant who says something (whether they are the leading voices in the field, or early career researchers), where it is said (a high impact journal or not), or how well it is said. The dominance/importance of a topic, idea, or discourse is derived from how often and how consistently a specific vocabulary co-occurs throughout the field. Such an approach has its limitations (as discussed above in relation to close vs. distant reading) but clearly also its merits. In a very inductive way, it allows to understand what happens in a research field in a different way by looking at overarching trends and patterns: How is the object of knowledge (in this case the sustainable university) dominantly presented and approached. This does not necessarily neglect the potential high impact of specific scholars or journals. If this high impact is indeed the case, this will result in co-occurrence of a similar vocabulary in the corpus, and thus find its way into the topic model.

The results of the discourse analysis allow us to say something about practice as well. The publications in the corpus are a combination of empirical research on for example ongoing change processes, case studies, best practices, and lessons learned on the one hand, and more conceptual work on the university and sustainable development on the other. This means that these three discourses have a root in practice and consequently also say something about these practices, despite this being an analysis of academic debate. However, just as the discourses are no typology to classify academic publications, they are also not a typology to classify or rank universities or higher education practices according to how sustainable they areFootnote14. As discourses, they show different ways in which the sustainable university can be discursively constructed. In doing so, these discourses suggest ways to approach policy documents on sustainability in higher education and might offer new ways to understand the meaning of higher education sustainability (niche) practices and how they relate to views on what a sustainable university is about.

Exploring pathways for further research

The notion of the sustainable university appears to be an ambiguous one: It refers to an idea of a (desirable future) university that engages with sustainability, but it is an umbrella term. It covers a plethora of different understandings of what such a sustainable university might be. This study made explicit how the sustainable university is dominantly understood and approached in the research field by identifying and analyzing the three dominant discourses on the sustainable university. A discourse analysis of dominant discourses makes explicit what often remains implicit and, in doing so, opens things up for discussion. This was also the aim of this study: To make the different ways in which the sustainable university is understood or approached more open and sharp, to lay differences and similarities between different discourses bare (cf. Östman, Citation1996), and to provide tools to further discuss the university – sustainability nexus in the field. This final section builds further towards this goal. Through a further comparison and discussion of the three discourses, both within the specific field and within a broader context of higher education scholarship, pathways for further research are explored. This is intended to provide conceptual resources for a continued discussion of what constitutes (or should constitute) the sustainable university.

Each of the three dominant discourses have specific implications for what elements are included and excluded and in what particular way. Zooming in on this is a good way to initiate this discussion, and the six domains of university sustainability engagement that formed the sensitizing conceptual framework (education, research, institutional organization, campus, on-campus experiences, and outreach & collaboration; see ) form a fitting starting point for this. shows an overview of which discourse addresses which domains of university sustainability engagement, shedding light on how the discourses differ regarding which of these domains they address and which they exclude.

Table 6. Included domains of university sustainability engagement in the three discourses.

Although the way and extent to which these six domains are addressed in the three discourses is already touched upon in the results section, it is important to zoom in on a few aspects here. Education appears to be primarily addressed in two ways in the corpus, tentatively described in the results section as education as accumulation and education as change, respectively in the first and second discourse. In the first discourse, we see an understanding of education as accumulation, which is characterized by a very specific jargon, referring to the student’s accumulation of knowledge, competences, skills and abilities. This can be related to a conceptualization of sustainability education as equipping and preparing students (with knowledge, competences etc.) to deal with complex and challenging sustainability issues in society (Lambrechts & Van Petegem, Citation2016). In the second discourse, we see an understanding of education as change, characterized by notions of behavior change, change of attitude, transformative learning, critical thinking, critical reflection and so on. However, this education as change appears to be a hybrid understanding of education. On the one hand, concepts such as behavior change and change of attitude refer to more normative and instrumental approaches to education in function of achieving (pre-determined) change in students (as for example described by Lambrechts et al. (Citation2018)). On the other hand, notions such as transformative learning, critical thinking and critical reflection relate closely to more open-ended approaches to education as transformation (as for example describe by Sterling (Citation2010) as a transformative approach to learning). These are two distinct and contrasting approaches to sustainability education in the university (Lambrechts et al., Citation2018) and the fact that they appear together in one discourse is interesting. It could mean that the differences between instrumental and open-ended sustainability education are not as clear-cut as often imagined (as e.g. argued by Ferreira (Citation2009)) or it might mean that the vocabulary used to write about these things simply is not broad and distinct enough to emerge as distinct in the topic modelling. Another point to emphasize here is that in the third discourse education is not in the picture at all. That one of the three dominant discourses on the sustainable university has no attention for education is an important finding. On the one hand it brings forth the question why this is the case, while on the other hand it is an invitation to further explore how a more technological focus on research and campus operations can be reconciled with education in a fruitful and meaningful way.

While discussions of domains of university sustainability engagement are a recurring theme in the field and often lead to comparable lists (e.g. Findler et al., Citation2019; Henderson et al., Citation2017; Lozano et al., Citation2015), it is a remarkable result of the study that none of the three discourses address all six domains. It implies that the sustainable university as approached in the literature is far from holistically sustainable, as elaborated in the introduction section in reference to Sterling and Maxey (2013). This observation might open up for envisioning alternative coherent ways of what a sustainable university could be. For example, what a sustainable university that engages with sustainability on all six domains would looks like, but also how the six domains can be approached in alternative ways. The three discourses presented here are thus in no way a delineation of the possible ways the sustainable university can be envisioned, but form a concrete starting point for further discussions on the matter, with the six domains as a powerful tool to engage with the matter.

Besides focusing on the differences between the three discourses, an extra step in this discussion is necessary. The academic debate on the sustainable university does not happen in a vacuum. Consequently, connecting the three dominant discourses in the university-sustainability literature to broader analyses and conceptualizations of higher education and the university in general, is a valuable way to explore new pathways for further research. In the remainder of this section, the discourses are connected to existing conceptual (non-sustainability related) frameworks on higher education that are, as argued for, relevant for the results of this study. This second step in the discussion, thus, can be seen as a stepping stone for future discussions on the sustainable university and to explore a number of pathways for future research on the topic.

The first discourse, the sustainable higher education institution, shows clear links to a number of recurring themes and critical discussions in the higher education literature. The centrality of management in this discourse, for example, relates closely to discussions on what some describe as (new) managerialism: in higher education in general (Deem & Brehony, Citation2005; Deem, Hillyard, & Reed, Citation2007), but also more specifically for example in relation to rankings (Lynch, Citation2015), assessment (Kalfa & Taksa, Citation2017), and quality assurance (Jarvis, Citation2014); not coincidentally three other elements in this first discourse. The sustainable higher education discourse also has elements of what Barnett (Citation2011) rather pejoratively calls the bureaucratic university: a university of regulation, management, surveillance, proformas, and evaluation. A final important connection to be made is that to the wider discussion on higher education and competences. Barnett (Citation1994), for example, critically discusses a ‘new vocabulary’ in higher education consisting of concepts as skills, vocationalism, competence, outcomes, capabilities, which is mirrored in how education is framed within this discourse.

The second discourse, the engaged community taps into a wide discussion about the university’s civic engagement, public service, and social responsibility. The discourse for example bares a stark resemblance to what Watson, Hollister, Stroud, and Babcock (Citation2011) call engaged universities, ‘committed to mobilizing their human and intellectual resources to address pressing needs of the societies in which they are located, and in the process to educate their students to be leaders for change’ (p. xxvii). The second discourse could thus be understood as a sustainable variant of such an engaged university in which civic engagement focuses on sustainability. However, there are also reasons to be weary of engagement as a guiding principle for the university. Barnett, for example, discusses ‘the lure of engagement’ (Barnett, Citation2022, p. 212) and warns for certain traps an all too strong focus on engagement can bring with it: the loss of autonomy and space for independent critical thinking. An over-commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals, for example, could leave the university ‘unable to critique those goals’ (Barnett, Citation2022, p. 220).

The outward focus of the green-tech campus discourse relates closely to models such as the triple helix (Etzkowitz, Citation2008) in which the university, industry and government are deeply interwoven with a focus on innovation for the knowledge-based society. Through its focus on the hard sciences, the green-tech campus discourse can also be related to two distinct but related forms of the university discussed by Barnett (Citation2011) as ‘the scientific university’ and ‘the entrepreneurial university’. The former is a university in which the knowledge core is dominated by the physical sciences (Barnett, Citation2011). This is reflected in this third discourse through the research-technology-innovation triad in relation to the physical infrastructure and design of the campus. The entrepreneurial university, on the other hand, presents itself with a different focus but is still mirrored in this discourse as well. The entrepreneurial university describes itself in the first place as an enterprise or corporation; it is a marketized university and the goods and services it supplies should be in function of the needs of its many stakeholders (Simons & Masschelein, Citation2009). This is reflected in how the market, industry and companies are related to the research-technology-innovation triad, but also for example in how consumption, procurement, and the users of the campus come to the fore in relation to campus operations. However, where Simons and Masschelein (2009) describe the entrepreneurial university as a university that produces research and education, the green-tech campus discourse seems to focus mainly on the former, neglecting the education aspect when it comes to what makes the university a sustainable university.

This situation of the three discourses in the wider higher education literature shows two things. On the one hand, it shows that the discourse analysis strengthens the empirical basis of the conceptualizations and problematizations discussed in the higher education literature referred to above. It makes clear that these approaches to and understandings of the university are also prominent in the literature that focuses on the university – sustainability nexus and, moreover, provides more insight into how they find a place in this literature. On the other hand, however, – and perhaps more importantly – this also shows that the three ways in which the sustainable university is most dominantly discussed in the academic literature are closely related to, or build upon conceptions of the university and higher education that have been problematized to a great extent in the wider higher education literature. This is a rather problematic observation that shows that further work in this direction is necessary. There is a lot of potential for further theoretical work on the sustainable university by building on discussions from the wider higher education field. This would also contribute to tackling the general lack of conceptual clarity and theoretical thoroughness of the literature on the university – sustainability nexus (see e.g. Alejandro-Cruz et al., Citation2019; Figueiró & Raufflet, Citation2015; Shephard et al., 2019) as described in the introduction section.

To summarize and conclude, this study opens up several pathways for further research on the sustainable university. First, similar research that would focuses on how the sustainable university is discursively constructed in other corpora such as for example policy documents, university sustainability reports, or course descriptions could be a valuable contribution to the field of study. Second, a more in-depth study of the discourses would complement the distant reading approach used in this article, whereas the latter allowed to study large-scale patterns in a very large corpus, a second step could be to zoom in on how these discourses are actually articulated in their specificity, with, for example, more attention for differences between the discourses, or for how sustainability or education are conceptualized. The discussion already hinted at this. A third path for future research is to relate the three discourses to actual practice. For example, having insight in how individual actors (teachers, university staff, students, policy makers) relate to these discourses would allow us to affirm, expand or problematize them. The same goes for individual universities with a strong sustainability agenda. It would be interesting to see how they relate (or do not) with these discourses. A fourth path is suggested by the exploration of connections between the results and the wider higher education literature. These connections show how the dominant ways in which the sustainable university is understood seem to tap into problematized conceptualizations of the university, something that warrants further investigation. Theoretical work is needed to further explore these connections in depth, but also empirical work is necessary, for example, to see how sustainable university practices and initiatives relate to these conceptualizations. Finally, and relating to the initial aim of the study, the three dominant discourses provide a groundwork for a continued debate about the sustainable university, in which the discussion in light of the six domains of university sustainability engagement and the exploration of connections with the higher education literature form a starting point. In this sense, this study should be seen as an open invitation for further work on alternative conceptualizations of what a sustainable university could be or should be.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Prof. Dr. Leif Östman and Prof. Dr. Katrien Van Poeck for their feedback and assistance throughout the study, Dr. Tom Van Acker for his help by writing the Julia script for splitting the documents, and the anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare.

Notes

1 Throughout the article the concept “university” is used in its broadest meaning, for example also including higher education institutions that do not officially carry the name “university”.

2 The author intentionally leaves open what this might imply.

3 How these sensitizing concepts are used in the data analysis is discussed in detail in the data collection and analysis section.

4 This means that the focus does not lie on for example one person’s use of language in one specific context such as a political speech, but on how discourses as discursive constellations of meaning function in larger social systems.

5 Laclau and Mouffe (Citation1985) originally discern between signs that are part of a discourse (i.e. “moments”) and signs that are not and reside in a discourse’s field of discursivity (i.e. “elements”). Following Carpentier & De Cleen (Citation2007) I use the term “element” to refer to both in order to keep it simple.

6 In what follows, all references to topic modelling refer to this algorithm.

7 In the original LDA article (Blei et al., Citation2003), the word “topic” is not defined besides as a latent variable.

8 An example of such a deliberation: The “eco*” search term could have been replaced by “ecol*” in order to exclude irrelevant purely economy-related hits which have to be manually excluded. However, this would have omitted hits with compound words with “eco” and was thus decided against.

9 Topic modelling does not perform well with long documents because longer documents tend to contain more unique words. TM aims to find clusters of words that have a high probability of co-occurrence in documents. If individual documents in a corpus contain more unique words, this implies a larger overlap of word use between documents, which makes documents less unique, leading to a fuzzier analysis.

The opposite is also a problem: if documents are too short, there might not be enough overlap in word use to find meaningful topics. A corpus with a variety in writing styles (for example text messages, personal emails, newspaper articles, and academic publications) could provide a similar problem.

10 MALLET is an open source software package which contains a topic modelling package provided by David Mimno (http://mallet.cs.umass.edu/). “MALLET” stands for “Machine learning for language toolkit”.

11 Comparable to doing test interviews to try out questions before starting the actual interview series of a study.

12 OCR: optical character recognition, a process that makes text in documents recognizable as text by the computer to allow further processing.

13 Making n-grams refers to the process of grouping together strands of words that together form one concept (e.g. “living lab” becomes “living_lab”). This allows the topic modelling software to recognize the concept as one word.

14 Partly also because universities are heterogeneous entities. Just like “it is unlikely that any single institution can be a pure instantiation of any one idea of the university” (Barnett, Citation2011, p.1), it is unlikely that this would be any different with these discourses.

References

- Alejandro-Cruz, J., R. Rio-Belver, Y. Alamnza-Arjona, and A. Rodriguez-Andara. 2019. “Towards a Science Map on Sustainability in Higher Education.” Sustainability 11 (13): 3521.

- Arora, S., R. Ge, Y. Halpern, D. Mimno, A. Moitra, D. Sontag, … M. Zhu. 2018. “Learning Topic Models – Provably and Efficiently.” Communications of the ACM. 61 (4): 85–93. doi:10.1145/3186262.

- Baker, P. 2006. Using Corpora in Discourse Analysis. London – New York: Continuum.

- Bardaglio, P. W., and A. Putman. 2009. Boldly Sustainable: Hope and Opportunity for Higher Education in the Age of Climate Change. Washinton, DC: NACUBO.

- Barnett, R. 1994. The Limits of Competence: Knowledge, Higher Education, and Society. Philadelphia: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

- Barnett, R. 2011. Being a University. London; New York: Routledge.

- Barnett, R. 2022. The Philosophy of Higher Education. A Critical Introduction. London & New York: Routledge.

- Biesta, G., M. Kwiek, G. Lock, H. Martins, J. Masschelein, V. Papatsiba, M. Simons, and P. Zgaga. 2009. “What is the Public Role of the University? A Proposal for a Public Research Agenda.” European Educational Research Journal 8 (2): 249–254. doi:10.2304/eerj.2009.8.2.249.

- Blei, D., A. Ng, and M. Jordan. 2003. “Latent Dirichlit Allocation.” Journal of Machine Learning Research 3: 993–1022.

- Blumer, H. 1954. “What is Wrong with Social Theory?” American Sociological Review 19 (1): 3–10. doi:10.2307/2088165.

- Bowen, G. A. 2006. “Grounded Theory and Sensitizing Concepts.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (3): 12–23. doi:10.1177/160940690600500304.

- Carpentier, N. 2017. The Discursive-Material Knot: Cyprus in Conflict and Community Media Participation. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Carpentier, N., and B. De Cleen. 2007. “Bringing Discourse Theory into Media Studies – The Applicability of Discourse Theoretical Analysis (DTA) for the Study of Media Practises and Discourses.” Journal of Language and Politics 6 (2): 265–293. doi:10.1075/jlp.6.2.08car.

- Deem, R., and K. J. Brehony. 2005. “Management as Ideology: The Case of ‘New Managerialism’ in Higher Education.” Oxford Review of Education 31 (2): 217–235. doi:10.1080/03054980500117827.

- Deem, R., S. Hillyard, and M. Reed. 2007. Knowledge, Higher Education, and the New Managerialism: The Changing Management of UK Universities. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Deleye, M., K. Van Poeck, and T. Block. 2019. “Lock-Ins and Opportunities for Sustainability Transition: A Multi-Level Analysis of the Flemish Higher Education System.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 20 (7): 1109–1124. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-09-2018-0160.

- Desha, C., and K. Hargroves. 2013. Higher Education and Sustainable Development: A Model for Curriculum Renewal (1st ed.). London: Routledge.

- Doudaki, V., and N. Carpentier. 2019. Critiquing Hegemony and Fostering Alternative Ways of Thinking about Homelessness: The Articulation of the Homeless Subject Position in the Greek Street Paper Shedia.

- Etzkowitz, H. 2018. The Triple Helix: University-Industry-Government Innovation and Entrepreneurship. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Ferreira, J. A. 2009. “Unsettling Orthodoxies: Education for the Environment/for Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 15 (5): 607–620. doi:10.1080/13504620903326097.

- Figueiró, P. S., and E. Raufflet. 2015. “Sustainability in Higher Education: A Systematic Review with Focus on Management Education.” Journal of Cleaner Production 106: 22–33. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.04.118.

- Findler, F., N. Schonherr, R. Lozano, D. Reider, and A. Martinuzzi. 2019. “The Impacts of Higher Education Institutions on Sustainable Development: A Review and Conceptualization.” Sustainability 20 (1): 23–38. doi:10.1108/Ijshe-07-2017-0114.

- Gale, F., A. Davison, G. Wood, S. Williams, and N. Towle. 2015. “Four Impediments to Embedding Education for Sustainability in Higher Education.” Australian Journal of Environmental Education 31 (2): 248–263. doi:10.1017/aee.2015.36.

- Goldstone, A., and T. Underwood. 2014. “The Quiet Transformations of Literary Studies: What Thirteen Thousand Scholars Could Tell Us.” New Literary History 45 (3): . 59–384. doi:10.1353/nlh.2014.0025.

- Gough, S., and W. Scott. 2007. Higher Education and Sustainable Development. Paradox and possibility: Routledge.

- Hallinger, P., and C. Chatpinyakoop. 2019. “A Bibliometric Review of Research on Higher Education for Sustainable Development, 1998–2018.” Sustainability 11 (8): 2401. doi:10.3390/su11082401.

- Henderson, J., A. Bieler, and M. McKenzie. 2017. “Climate Change and the Canadian Higher Education System: An Institutional Policy Analysis.” Canadian Journal of Higher Education 47 (1): 1–26.

- Horhota, M., J. Asman, J. P. Stratton, and A. C. Halfacre. 2014. “Identifying Behavioral Barriers to Campus Sustainability: A Multi-Method Approach.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 15 (3): 343–358. doi:10.1108/IJSHE-07-2012-0065.

- Howarth, D. R., and Y. Stavrakakis. 2000. “Introducing Discourse Theory and Political Analysis.” In Discourse Theory and Political Analysis: Identities, Hegemonies and Social Change, edited by D. R. Howarth, A. J. Norval, & Y. Stavrakakis. Manchester: Manchester University Press.