?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Plant-based dietary choices can help to mitigate climate change. Yet, most people still consume meat. Social identity influences dietary choices. This study tests whether shared identity, pro-veg*n norms, attitudes, and dietary intentions, can be strengthened via a vegan cooking workshop for children. Pupils (N = 155) cooked in small groups (3–6 members). Compared to pre-measures, shared identity, pro-veg*n (vegan and/or vegetarian) norms, attitudes, dietary intentions, and appreciation of vegan food increased after the vegan cooking workshop. Changed perceptions about what is important or not (injunctive norms) at school predicted changes in attitudes; increased dietary intentions were predicted by changed inferences about the behaviours of peers with whom pupils directly cooked. Jointly cooking a vegan meal thus seems an effective intervention to shape shared identity and pro-veg*n norms, and foster attitudes and dietary intentions in line with this formed pro-veg*n social identity. Therefore, cooking workshops may induce social change.

Graphical Abstract

Today’s global food supply chain creates approximately 26% of global greenhouse gas emissions (IPCC Citation2018; Poore & Nemecek, Citation2018). Livestock – especially cattle – are responsible for more greenhouse gas emissions than all other food sources, predominantly due to methane emissions resulting from rumen fermentation. A dietary shift away from the consumption of meat and dairy products is, therefore, one of the most effective ways to reduce the negative environmental impact on global warming (Poore & Nemecek, Citation2018; Aleksandrowicz et al. Citation2016). Indeed, dietary adjustments are included in all the proposed pathways of the latest IPCC Special Report (2018), as they fundamentally contribute to the mitigation needed to meet the climate targets set by the Paris Agreement. However, to date, little scientific research has examined how people can be motivated to change their dietary choices.

Recent literature suggests that the transition to a vegan diet may be difficult (Bolderdijk and Jans Citation2021; Kurz et al. Citation2020). Food consumption is associated with clear norms and strong customs (Higgs and Ruddock Citation2020), and those adhering to a plant-based diet can face derogation and stigma, as they deviate from current ‘normal’ food practices of their group (Judge & Wilson, Citation2019; Minson and Monin Citation2012; MacInnis and Hodson Citation2017; Stapleton Citation2015). Food consumption is thus largely informed by our social identity, that is, by group membership(s) we internalise into our self-concept, and that guide how we (should) think and act (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979; Turner Citation1991).

The internalisation of group identities shows as early as the age of five (Bennett Citation2011; Bennett and Sani Citation2011), and an appreciation of group-related food practices develops among children between six and ten years old (Bennett Citation2011; Quintana et al., 1988). As meat-eating continues to be the norm, children are socialised into the belief that meat consumption is ‘normal, natural, and necessary’ (Joy 2010, p. 96). Children learn to like meat, for example, through their family and educational institutions (Rice Citation2013). Thus, while children between six and ten years old can already morally commit to a vegan diet (Hussar and Harris 2010), group identities and group norms discourage and derogate this behaviour.

Compared to today’s adults, children and future generations will be much more affected by climate change, and the most drastic changes will be required from them (Sanson, Van Hoorn, and Burke Citation2019). It therefore is vital to understand how children develop social identities and associated pro-vegan norms, promoting plant-based dietary practices which ultimately facilitate the mitigation of climate change (Spannring & Grušovnik, Citation2019). School lunches are often not considered as part of the written curriculum, but they can be an overt educational event (Reise, 2013; Rowe and Rocha Citation2015). However, because meat consumption is still normative in society at large, school interventions promoting plant-based diets at school, can result in political and conflictual responses from pupils (e.g. Lindgren Citation2020).

In the present paper, we test whether vegan cooking workshops at schools are an effective intervention to change dietary norms that promote plant-based dietary choices among children. Specifically, we propose that the act of cooking a vegan meal together may enable the formation of a shared identity with pro-veg*n norms in children, and as such promote pro-veg*n attitudes and dietary intentions aligned with this identity. In this paper, we do not distinguish between vegan and vegetarian plant-based diets and refer to them together as ‘pro-veg*n’.

1.1. The relevance of pro-veg*n social identity

The influence of groups on members’ pro-veg*n dietary choices, should in theory be dependent on both the content and strength of the group’s pro-veg*n norms, and the extent to which an individual identifies with this group (Fielding and Hornsey Citation2016; Fritsche et al. Citation2018; Masson & Fritsche, 2016). Veg*n dietary norms reflect both the extent to which group members find a veg*n diet important and (in)appropriate (injunctive group norms), as well as the veg*n dietary behaviours group members generally engage in (descriptive group norms; Cialdini, Reno, and Kallgren Citation1990, Cialdini, Kallgren, and Reno Citation1991). Previous research shows that both injunctive and descriptive norms correlate with dietary intentions, but that their impact on dietary intentions can depend on their interplay (Staunton et al. Citation2014). Importantly, this normative influence is dependent on the extent to which a particular group membership is part of one’s identity, and thus internalised into the self-concept (Turner Citation1991). The more one identifies themselves in terms of a social identity with strong pro-veg*n norms (which we jointly refer to as a ‘pro-veg*n’ social identityFootnote1), the more motivated one should be to engage in a pro-veg*n diet. This implies that the influence of vegan cooking workshops on pupil’s pro-veg*n attitudes and dietary intentions, might partially depend on their ability to (a) induce (injunctive and descriptive) pro-veg*n norms and (b) social identification among participating children.

1.2. The formation of pro-veg*n social identities

We propose that by cooking a vegan meal together, both the perception of pro-veg*n group norms and identification among participating children can be strengthened. We derive this proposition from general insights on the processes of social identity formation. Social identities can be formed both from the commonalities group members share (and that differentiate them from other groups; Turner et al. Citation1987; a deductive process, see Postmes, Haslam, and Swaab Citation2005a), as well as from the integration of individual group members’ actions and contributions (an inductive process; Jans, Postmes, and Van der Zee Citation2011; Koudenburg et al. Citation2015; Postmes, Haslam, and Swaab Citation2005a). Through the interactions with our peers, we can discuss what we find important as a group and develop behavioural norms. These intra-group interactions simultaneously shape group norms and enable members to identify as a group (Jans, Postmes, and Van der Zee Citation2012, Jans et al. Citation2015; Postmes et al. Citation2005b; Thomas, McGarty, and Mavor Citation2016). As such, cooking a vegan meal together during a cooking workshop can make dietary veg*n behaviours normative and the engagement in this joint action can strengthen group identification. Thus, by inducing a pro-veg*n social identity among participants, vegan cooking workshops may boost pro-veg*n attitudes and dietary intentions aligned with this identity.

Importantly, we assume that this creation of a pro-veg*n social identity is not limited to those with whom pupils cook together in direct collaboration. We expect that the impact might spill over to the overarching social category in which these cooking workshops take place. Social interactions within small interactive groups play a central role in shaping and transmitting social and cultural norms (Kashima, Klein, and Clark Citation2007; Koudenburg et al. Citation2021). From daily interactions, we infer what is normative within the social category. Hence, the small-group cooking activities may also change perceptions of what is normative at school and increase pupils’ identification with school. This induced pro-veg*n social identity at the school level, can be an additional social influence on pro-veg*n attitudes and dietary intentions.

1.3. The present study

There is limited research on the development of social identities in children (Bennet, 2011). Research on children has mainly focused on the development of major social categories (e.g. gender) as social identities, but has neglected the formation of more specific social identities, such as a pro-veg*n social identity. Moreover, studies on the development of social identities in small interactive groups are rare, with limited research focusing on the influence of social identities in shaping children’s actions. A notable exception is the work by Reynolds and colleagues who have argued and found that school identification is a critical component in transforming (learning) behaviours of children (e.g. Lee et al. Citation2017; Reynolds et al. Citation2015).

The present research aims to contribute to this limited research, by examining whether vegan cooking workshops foster the formation of pro-veg*n social identity at the cooking-group level where interactions occur and at the school-level, and as consequence promote plant-based food choices. Specifically, using a repeated-measures design, we propose that pro-veg*n attitudes and intentions are higher after the vegan cooking workshop (H1), because vegan cooking workshops enable the formation of social identities with pro-veg*n norms at the level of the cooking group (H2), and the school (H3). Hence, stronger pro-veg*n social identities at the cooking group and school level are expected to be related to higher pro-veg*n attitudes and intentions (H4 and H5).

2. Method

2.1. Participants and design

Data were collected in nine schools across Germany (in five states), in the context of Plant-Powered Pupils project days (https://aktion-pflanzenpower.de/aktionstag/). Schools varied in type: one primary Montessori school, eight secondary schools, of which four contemporary (one private), two general (hauptschule), and two more academic (gymnasium). Three of the schools were in an urban area; the others were in a rural area. Three schools had a large proportion of pupils with migrant backgrounds.

Data were collected before and after the vegan cooking workshop sessions (n = 17), in which pupils cooked in small groups (n = 52), ranging from three to six membersFootnote2. In total, 155 pupils consented (including parental consent, and school consent) to participate in the study. Pupils, who did not consent to the study, could still voluntarily participate in the vegan cooking workshop as part of the project day. No children refused participation in the workshop. Age ranged from 10 to 17 years (M = 13.48; SD = 1.54; 9 missing). The study included 59 male, and 95 female pupils (one participant omitted their gender).

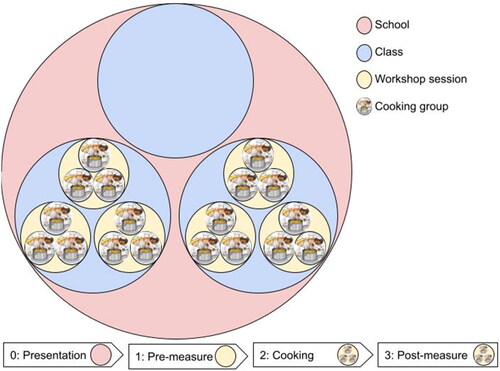

An a-priori power analysis showed that 54 participants were required to detect a medium-sized effect with a one-way MANOVA repeated-measures design (f = .25, ∝ = 0.05; power = 0.95; 2 groups; 2 measurements with a .5 correlation; G*Power; Faul et al. Citation2007). As participants would be nested in small cooking groups (nested in workshop sessions, nested in classes, nested in schools; see ), we considered a Design effect to correct for the interdependence in cooking groups. Assuming cooking groups with an average size of four members and an ICC of .15 (see Koudenburg et al. Citation2015), the required sample size was 78. When recalculating the power analyses with the obtained ICCs (which turned out higher than expected, highest rho = .41), the required sample size was 121. Hence, our sample of 155 pupils still yielded over 95% power to detect a medium-sized effect.

2.2. Procedure

School teachers could request a project day, fully funded by ProVeg and the health insurance company BKK ProVita. The teachers’ requests for a project day were shared with a facilitator pool. We confirmed project days that suited our time schedule. The researchers then contacted the teachers to arrange the necessary preparation (including asking for parental and school informed consent and organising the cooking workshop). The study (18276-O) obtained ethics approval by the Ethical Committee of Psychology of the University of Groningen.

The project days were one-time activities, and not embedded in a broader curriculum. They generally consisted of two parts. First, a presentation on reasons for a vegan diet was given for as many pupils as possible at the participating schools (Step 0; ). Second, cooking workshops were carried out with selected classes afterwards. The teacher divided a participating class into two or more cooking workshop sessions in advance, depending on the size of the class. The first session always started immediately after the presentation, while participants of the other session(s) had regular class. The next workshop session started after the previous one had ended. The presentation targeted five reasons for a vegan diet (taste, health, justice, animal, and environmental protection; https://proveg.com/5-pros/) and gave all participants of our study the same base-line information on vegan diets prior to the pre-measure. Any changes in dietary preferences between the pre- and post-measure can thus be attributed to the cooking workshop and not the presentation as such.

At the beginning of each cooking workshop, participants independently completed the pre-measure in silence, under the supervision of the researcher and teacher (Step 1; ). Participants could ask the researcher questions to clarify specific questions for them. After the completion of the pre-questionnaire, participants were divided into cooking groupsFootnote3 (Step 2; ). The researchers adapted the cooking workshops to stimulate shared social identity formation in the cooking group. Therefore, before the actual cooking started, participants put on t-shirts as aprons, read the recipe in their groups out loud, and engaged in a group energizer (a ‘meal dance’). Every cooking group cooked at a different kitchenette or table, depending on the availability and spatiality of the school kitchen or classroom. Where possible, the same recipes were cooked (i.e. spaghetti, with muffins as dessert). However, in some cases an alternative dish was cooked (for example, when there was no kitchen, as was the case in one school). In most cases, four cooking groups were formed, two of which cooked the same dish. Finally, when all cooking groups had cooked their dish, all cooking groups of a session sat together to discuss the cooking process and eat their meal. Depending on the lay-out of the room, cooking groups sat behind their own table when possible. After all participants of a session finished eating, they filled out the post-questionnaire (Step 3; ).

2.3. Measures

The pre-questionnaire and post-questionnaire mostly included the same measures. At the start of the pre-questionnaire, definitions for ‘vegetarian’, ‘vegan’, ‘vegetarian food’ and ‘vegan food’ were given. The pre-questionnaire assessed appreciation of vegan meals, pro-veg*n attitudes and dietary behaviours. Furthermore, the pre-questionnaire assessed injunctive and descriptive pro-veg*n norms and identification at the level of the workshop session and the school. The post-questionnaire assessed the same measures. However, aspects of pro-veg*n social identity were assessed at the level of the cooking-group instead of the workshop session, as this was the group with which pupils most directly interacted (cooking groups were not yet formed at the time of the pre-measure). All items could be answered on a scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree, unless otherwise specified. The researcher was present to help pupils understand the items in the questionnaire. See for an overview of all measures, including descriptive statistics and reliability indicators.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations for all measures.

2.3.1. Vegan taste

We assessed participants’ appreciation of vegan food in the pre- and post-questionnaire. In the pre-measure participants were asked how good vegan food tasted to them on an 8-point scale, ranging from 1 = not at all to 8 = very good). In the post-measure this was assessed slightly differently. Participants indicated their agreement to the statement ‘In general vegan food tastes good to me’ on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree. To make the two scales comparable we transformed the scales of the pre-measure to a 7-point scale.

2.3.2. Pro-veg*n attitudes

We assessed pro-veg*n attitudes in the pre-and post-measure by asking to what extent participants found it important to eat vegetarian, vegan, and to reduce their own meat consumptionFootnote4.

2.3.3. Pro-veg*n behaviours and intentions

In the pre-measure, participants estimated how often they ate vegan dishes, cooked vegan dishes with their family, and brought vegan dishes to school in the past seven days. In the post-measure, this was assessed as their intentions in the next seven days. Both scales were answered on an 8-point scale (0 = not to 7 = seven days). Vegetarian behaviours/intentions were assessed in the same way. Vegan behaviours were positively skewed (skewness = 2.89, SEskewness = 0.195, kurtosis = 10.05, SEkurtosis = 0.387), as most respondents did not eat vegan. In the post-measure, vegan and vegetarian intentions loaded on the same factor (in the pre-measure behaviours loaded on separate factors). We, therefore, aggregate vegan and vegetarian behaviours (and intentions), in a single scale of pro-veg*n behaviours (intentions). This also reduced the skewness in the pre-measure (skewness = 1.22, SEskewness = 0.195, kurtosis = 1.574, SEkurtosis = 0.387).

2.3.4. Injunctive pro-veg*n norms

We assessed perceived injunctive pro-veg*n norms with four items. The first three items are similarly formulated as the pro-veg*n personal attitudes, but ‘I’ is replaced by the specific reference group, e.g. pupils from my cooking group. Specifically, we assessed to what extent participants perceived pupils from their workshop session (cooking group)/school, to find it important: …to eat vegetarian, …to eat vegan, …to reduce their meat consumption, and …that the participant eats little meat (e.g. ‘The pupils from my school find it important that I eat little meat’).

2.3.5. Descriptive pro-veg*n norms

We assessed the perceived descriptive norms similarly to the assessment of personal behaviours and intentions. In the pre-measure we asked participants how often they thought the pupils from their workshop session [school] ate vegan and vegetarian in the past 7 days. In the post-measure we assessed the perceived intentions of pupils from their cooking group and school. We combined the vegan and vegetarian behaviour (intention) into one scale, to reduce the number of constructs, and because these scales did not clearly cluster into separate factors.

2.3.6. Social identification

Social identification with the cooking group and school was assessed in the pre-and post-measure with the single-item measure of social identification (Postmes et al., 2013), complemented by two items from the satisfaction and solidarity component of the identification scale by Leach et al. (Citation2008; as recommended by Postmes et al., 2013), e.g. ‘I am glad to be in this cooking group’. The reliability at the school-level was rather low, α pre = .63; α post = .71. This might be because for the two latter items we referred to the school and not to the pupils from school, and as such might have captured some form of place identity rather than a social identity. We therefore decided to only include the single item of social identification on the school level (i.e. I identify with the pupils from my school), as this single item has good validity and reliability (Postmes et al., 2013; Reysen et al., 2013).

3. Results

As participants were nested in cooking groups, workshop sessions, classes and schools, we controlled for the interdependence of the data. We conducted multilevel regression analyses with random intercepts (Mixed Models; SPSS 26). ICC scores differed for the level of nesting, but particularly ICCs within cooking groups and sometimes within sessions were high. We controlled for either the cooking group or the session level, depending on which level improved model fit significantly, and accounted for most of the variance at the other level (consistently controlling for the cooking group resulted in a non-positive Hessian Matrix for school identification). Also controlling for the other levels did not significantly improve model fit and was thus redundant.

For the repeated-measures analyses, the intercept-only model consisted of three levels (measurement, individuals, cooking groups or session). To assess whether the workshop affected our key outcomes we added Time as repeated measure in Model 1 (0 = pre-measure; 1 = post-measure). Repeated measures models were specified with unstructured covariance structure between individuals. Explained variance and effect sizes are calculated based on compound symmetry variance components, as these simpler calculations generally yield similar values as the complex calculations based on fully multivariate models (Snijders and Bosker Citation1991).

3.1. Effects of the cooking workshop on personal motivation

After the cooking workshop participants scored significantly higher on how well they believed vegan food tasted and how important they felt it was to eat veg*n. Furthermore, participants intended to eat significantly more veg*n after the workshop, then they ate before (a small effect). In line with our first hypothesis the cooking workshop thus increased pupils’ personal motivation to eat veg*n ().

Table 2. Regressions of outcome variables on time (after compared to before the cooking workshop).

3.2. Effects of the cooking workshop on pro-veg*n social identities

Importantly, we assumed that the cooking workshop would also increase participants’ pro-veg*n social identity at the cooking-group level (H2) and the school level (H3; see ). This increase was not present in the strength of identification with the cooking group; we did not find a difference in session identification before, and cooking group identification after the workshop. However, the content of the social identity of the cooking group did change: After the cooking workshop participants perceived their cooking group to have stronger injunctive and descriptive pro-veg*n norms, than they perceived their session group to have before the cooking workshop.

Furthermore, the cooking workshop resulted in an increased pro-veg*n social identity at the school level. School identification was higher after the cooking workshop, compared to before. Furthermore, participants perceived their school to have stronger injunctive pro-veg*n norms, compared to before the cooking workshop. However, there was no significant difference in perceived pro-veg*n descriptive school norms.

3.3. The relation between pro-veg*n social identities and personal motivation

Next, we examined whether the increased personal motivation to eat veg*n (attitudes and intentions), was predicted by participants’ pro-veg*n social identities at the cooking group and school level. For this, we added pro-vegan group and school norms, besides Time, to the Repeated measures models for attitudes and intentionsFootnote5.

In total, pro-veg*n norms explained an additional 22% of the variance in attitudes. Specifically, pro-veg*n attitudes were only significantly predicted by pro-veg*n injunctive norms at the school level, but not by descriptive pro-veg*n school norms, nor by injunctive or descriptive pro-veg*n cooking group norms (see ). By adding pro-veg*n norms to the model, the positive relationship between Time and pro-veg*n attitudes reduced and became non-significant.

Table 3. Regressions of personal motivations on pro-veg*n norms at the cooking group and school level.

For intentions, pro-veg*n norms explained an additional 19% of the variance. Specifically, pro-veg*n intentions were significantly uniquely predicted by pro-vegan descriptive norms at the cooking-group level, but not by injunctive cooking group norms, nor by injunctive or descriptive school norms (see ). By adding pro-veg*n norms to the model, the positive relationship between Time and pro-veg*n intentions decreased but remained significant.

Thus, as expected, pro-veg*n norms at the group- and school level were positively associated with personal pro-veg*n attitudes and intentions. However, what type of norm at which level was predictive, differed per outcome measure. Whereas more abstract ideas about what is important or not (injunctive norms) at the school level influenced personal pro-veg*n attitudes; simultaneously, the influence on behavioural intentions was shaped by pupils’ direct interactions with their peers, and the inferences they made about the behaviours of their peers in their direct environment.

4. Discussion

Using a repeated-measures design, we tested whether vegan cooking workshops at schools, in which pupils cooked together in small-cooking groups could be an effective intervention to change dietary norms to promote more sustainable dietary choices among children. Specifically, we proposed that the act of jointly cooking a vegan meal could foster the formation of a shared identity and associated pro-veg*n norms in children at the level of the cooking group and the school, and as such promote dietary intentions aligned with these pro-veg*n social identities. Generally, we found support for the effectiveness of the cooking workshop, and for the formation and relevance of pro-veg*n social identities (although not on all indicators; see for a summary of findings ).

Figure 2. Visual representation of the effects of the vegan cooking workshop on the formation of pro-veg*n social identities and personal motivations.

4.1. The effectiveness of vegan cooking workshops

Our findings corroborate with previous findings on the impact of cooking workshops, and cooking more generally, on food preferences, and dietary motivations of adults and children (see for reviews; Farmer, Touchton-Leonard, and Ross Citation2018; Hasan et al. Citation2019; Reicks, Kocher, and Reeder Citation2018; Carahar et al., 2010). Specifically, we show that pupils enjoyed the taste of vegan food more after the cooking workshop compared to before, and that their motivation to engage in pro-veg*n dietary behaviours (attitudes and intentions) increased after the workshop. Vegan cooking workshops may thus be an effective tool to foster the transition to plant-based diets.

Importantly, our findings extend generally examined benefits of cooking workshops, by showing that these workshops do not only increase personal dietary motivations but also induce the formation of pro-veg*n social identities; strengthen pupil’s identification with their schools, and the content of this identity. This leads pupils to perceive their schools as endorsing more pro-veg*n norms (injunctive norms). Moreover, while identification with peer pupils remains unaffected by the workshop, the content of the identity does change; pupils perceive their peers to endorse more pro-veg*n norms (injunctive norm change) and to behave accordingly (descriptive norm change). This means that cooking workshops might change more than individuals’ dietary attitudes and intentions. Cooking workshops may induce larger social change; changing with which groups we identify and perceptions of what is normative amongst those with whom we interact, and in the broader societal context in which these interactions occur.

Developing food literacy (i.e. ‘knowledge, skills and behaviours required to plan, manage, select, prepare and eat food to meet needs and determine intake’; Vidgen and Gallegos Citation2014, p.54) is becoming more central to education (Vidgen Citation2016). The impact of vegan cooking workshops might be bigger, broader, and longer lasting when part of the written school curriculum, instead of a one-time activity (cf., Reise, 2013; Rowe and Rocha Citation2015). For example, in a whole school approach to health and sustainability, food consumption and provision is a fundamental component of education (Hunt et al. Citation2015; Lister-Sharp et al., 1999; Shepherd et al, 2002). Future research could examine whether and how the embeddedness of vegan cooking workshops in the school’s curriculum influences the impact vegan cooking workshops have on developing food literacy, changing personal dietary motivations, and creating larger social change.

4.2. The formation of pro-veg*n social identities

Our findings provide novel evidence that social identities are not only deduced from intergroup comparisons and similarities within the group but can also be shaped by interactions between individual group members and their unique contributions to the group (a process of inductive identity formation; Postmes et al., 2005). Previous research on the inductive formation of shared identity focused on identification (e.g. Postmes et al., 2005; Jans, Postmes, and Van der Zee Citation2011, Citation2012), norms regarding how we interact with others (e.g. Postmes et al., 2005; Smith & Postmes, 2009), and other indicators of solidarity (Koudenburg et al. Citation2015). The present study extends these findings, first, by showing that perceptions of what ‘we’ find important (injunctive norms), and what group members generally do or intend to do (descriptive norms) in terms of everyday practices (eating), are induced out of intra-group interactions too.

Second, we show that this inductive social identity formation is not limited to the group in which these interactions occur but extend to perceptions of how group members should act in the broader societal context, in this case, at school (see also; Kashima, Klein, and Clark Citation2007; Koudenburg et al. Citation2021), and their identification with this higher-order group. This is a promising finding as it suggests that social identities might spark wider change, than suggested by self-categorization theory (Turner Citation1991); social identities can cross group boundaries (see also Jans Citation2021; Postmes et al. Citation2013b; Van Mourik Broekman et al. Citation2019) impacting how we think and feel about overarching group memberships too.

Third, this is, to our knowledge, the first study that suggests the possibility of inductive social identity formation already among children of around 13 years old. Previous research has examined self-categorization processes of social identity formation in children (see for reviews, Benett, 2011, Bennett and Sani Citation2011); children self-categorise from a young age in terms of larger social categories, such as gender, ethnicity, nationality. The present research underlines the importance of social identity processes at the school level, for shaping children’s attitudes and behaviours (Reynolds et al. Citation2015). The study provides evidence that children shape their own social identities through their interactions with their peers (cf. Brandstatdter & Lerner, 1991), and that these identities have consequences for their personal motivations to engage in behaviours, in a rather similar vein as social identities for adults. Participatory approaches at school may facilitate pupils’ ability to induce a shared identity, as it enables them to actively contribute and interact (cf. Öhman and Öhman Citation2013). Previous research suggests that the implementation of vegan food at school without pupils’ involvement can result in fierce resistance (e.g. Lindgren Citation2020). Our research suggests that when pupils’ can actively participate and discuss the implementation of vegan food via vegan cooking workshops, pro-veg*n can become part of their identity.

Fourth, while our findings underline that social identities impact group members’ personal motivations (Turner Citation1991), we do find differential social influences depending on the source of influence (school vs. cooking group), the type of influence (injunctive vs. descriptive norms), and the specific outcome measure. It seems that what people themselves find important, is shaped by abstract ideas about what is (dis)approved of in their broader society (here: the school), yet, how they intend to act seems to be shaped by their observations and expectations of actions of the peers with whom they directly interact. Whilst previous research has theorised about the differential impact of descriptive and injunctive norms (Keizer et al., 2016; Cialdini et al., 990;1991) and about the source of influence separately, our findings suggest an interplay between the type of norm, the source of influence (society at large or our direct network), and the outcome measure, which requires further theorising. In this regard, an interesting question arises for future research: How do newly shaped norms (here: pro-veg*n cooking group and school norms) compete with well-established conflicting norms of those with whom people interact daily (e.g. pupil’s parents) and that exist in relevant subgroups (e.g. cultural, religious, or national groups) and society at large. A pessimistic perspective suggests that people can face stigma and derogation from other groups for their newly established intentions, and these competing social influences thus make long-lasting change unlikely (Kurz et al. Citation2020). However, there is room for optimism, as research shows that children can change their parents’ norms and environmental behaviours (Damerall, et al., 2013; Gentina and Muratore Citation2012), and that pro-environmental minorities can pave the way towards ‘tipping points’ and societal change (Bolderdijk and Jans Citation2021).

5. Limitations

Our findings on the effectiveness of cooking workshops to change dietary motivations among children seem promising and have ecological validity. Yet, there are some limitations that urge for future research before firm conclusions can be drawn about the causality and strength of these effects.

First, like most studies on cooking interventions (Reicks, Kocher, and Reeder Citation2018), our study did not include a control condition nor a long-term follow up. The study did include a pre-measure, which was taken after pupils received general information about the benefits of a vegan diet; changes between the pre-and post-measure can thus be attributed to the cooking workshop. Yet, future research is needed to examine how long lasting the impact of a vegan cooking workshop on the formation of pro-veg*n social identities is.

Second, the present study did not account for sociological and cultural factors, which may hinder or facilitate the impact of vegan cooking workshops. Future research is needed to examine whether our findings are generalizable to other cultural contexts, and to better understand how effects of vegan cooking workshops interact with other norms that also influence children’s attitudes and dietary intentions.

Third, because we assessed the pre-measure before cooking groups were formed, we assessed characteristics of a pro-veg*n social identity at the workshop-session level in the pre-measure instead. As such, differences between the pre- and post-measure might be partly due to these different levels of assessment. However, our important effects of the cooking workshop cannot be attributed to allocation to different (more or less) pro-veg*n groups, as this would have resulted in more diversity in group norms, whereas we found an increase in injunctive and descriptive norms across the board. It could, however, explain why we did not find an effect on identification for the cooking-group level: identification with the workshop session and cooking group might be informed by participants’ relational history with pupils from their class.

Fourth, our measures were either self-developed or adapted from validated scales for adult samples, to keep the questionnaires short. Although participating children could ask for clarification when a question was unclear to them, we do not know how suitable our measures are for this specific age group.

Fifth, we assume that the effects of the cooking workshop can be attributed to group processes. Indeed, most cooking interventions are group based (Farmer, Touchton-Leonard, and Ross Citation2018). However, as we did not directly compare the effectiveness of the cooking workshop to a condition in which pupils cooked by themselves, we cannot conclude that the found benefits are due to the act of cooking together. Future, research could compare the current cooking workshop, to a cooking alone condition, and a no-cooking condition, to gain better understanding in whether cooking alone indeed is significantly less impactful than cooking together, as social identities – especially those at the peer level, which are most important in shaping descriptive norms – are less likely to be affected.

6. Conclusion

Compared to today’s adults, children and future generations will be much more affected by climate change, and the most drastic changes will be required from them (Sanson, Van Hoorn, and Burke Citation2019). However, so far, the youth is largely left out from participation in important societal decision-making about the sustainability of their future. Our findings underline children’s capacity to experience collective life and define themselves in terms of shared group memberships (see also Bennett Citation2011). Children consider the interest of collectives in their thoughts and actions and are motivated to act in a manner that benefits the future of society (see also the Fridays For Future movement). Educators perceive a moral necessity to prepare future generations to address the impacts of climate change (Cutter-Mackenzie & Rousell, Citation2019; Lawson et al. Citation2019). The present research suggests vegan cooking workshops at school might help in this regard as they foster the formation of social identities that benefit the environment. This capacity of social identity development suggests that the youth could potentially play a more active role in the creation of a sustainable society.

Author contribution

Lise Jans (conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, writing), Namkje Koudenburg (conceptualization, methodology, review and editing), Lea Grosse (Conceptualization, methodology, investigation)

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.2 KB)Disclosure statement

Lea Grosse conducted the research for her master thesis under supervision of Lise Jans and Namkje Koudenburg. She received financial support from ProVeg Deutschland e.V. for her work as an action cook (speaking and lecture fees and travel reimbursement). ProVeg Deutschland e.V. had no influence on the hypotheses, research design, execution, analyses, and write-up.

Notes

1 Note that we slightly diverge from the definition of veg*n identity in the literature. Where ‘veg*n’ (social) identity tends to refer to an opinion-based group identity (McGarthy et al., 2009), i.e., identifying with veg*ns as a group (e.g., Cruwys et al., Citation2020; Judge et al., 2022) we use the term ‘pro-veg*n’ social identity more broadly, to refer to identifying with any group with strong pro-veg*n norms.

2 We planned our research around 20 workshop sessions with 258 pupils. Three sessions (with approximately 40 pupils) were cancelled. We collected raw data from 188 pupils, of which 33 pupils were deleted because parental and/or child’s active consent was missing afterwards.

3 We manipulated the form of cooking (cooking in unison vs. complementary) to explore whether the impact of the cooking workshop on the formation of a pro-vegan social identity, depended on the form of cooking. Methods and results regarding the form of cooking are described in the appendix(Supplemental).

4 To get a better understanding of why they perceived this to be important, we added two additional items, which were not aggregated in the scale: I find it important to behave environmentally friendly/ animal friendly.

5 We checked whether identification impacted the effects of norms on personal motivations (cf. Masson and Fritsche Citation2014). This was not the case. For parsimony, we report the results excluding identification.

References

- Aleksandrowicz, L., R. Green, E. J. Joy, P. Smith, and A. Haines. 2016. “The Impacts of Dietary Change on Greenhouse Gas Emissions, Land Use, Water Use, and Health: A Systematic Review.” PLoS One 11(11): e0165797. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0165797.

- Bennett, M. 2011. “Children’s Social Identities.” Infant and Child Development 20(4): 353–363. doi:10.1002/icd.741.

- Bennett, M., and F. Sani. 2011. “The Internalisation of Group Identities in Childhood.” Psychological Studies 56(1): 117–124. doi:10.1007/s12646-011-0063-4.

- Bliuc, A. M., C. McGarty, K. Reynolds, and D. Muntele. 2007. “Opinion-Based Group Membership as a Predictor of Commitment to Political Action.” European Journal of Social Psychology 37(1): 19–32. doi:10.1002/ejsp.334.

- Bolderdijk, J. W., and L. Jans. 2021. “Minority Influence in Climate Change Mitigation.” Current Opinion in Psychology 42: 25–30. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.02.005.

- Caraher, M., M. Wu, and A. Seeley. 2010. “Should we Teach Cooking in Schools? A Systematic Review of the Literature of School-Based Cooking Interventions.” Journal of the Home Economics Institute of Australia 17(1): 10–18.

- Cialdini, R. B., C. A. Kallgren, and R. R. Reno. 1991. “A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: A Theoretical Refinement and Reevaluation of the Role of Norms in Human Behavior.” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 24: 201–234. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60330-5

- Cialdini, R. B., R. R. Reno, and C. A. Kallgren. 1990. “A Focus Theory of Normative Conduct: Recycling the Concept of Norms to Reduce Littering in Public Places.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 58(6): 1015–1026. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015.

- Cutter-Mackenzie, A., and D. S. Rousell. 2019. “Education for What? Shaping the Field of Climate Change Education with Children and Young People as Coresearchers.” Children’s Geographies 17(1): 90–104. ISSN 1473-3277 doi:10.1080/14733285.2018.1467556.

- Cruwys, T., R. Norwood, V. S. Chachay, E. Ntontis, and J. Sheffield. 2020. “An Important Part of Who I Am": the Predictors of Dietary Adherence among Weight-Loss, Vegetarian, Vegan, Paleo, and Gluten-Free Dietary Groups.” Nutrients 12(4): 970. doi:10.3390/nu12040970.

- Damerell, P., C. Howe, and E. J. Milner-Gulland. 2013. “Child-Orientated Environmental Education Influences Adult Knowledge and Household Behaviour.” Environmental Research Letters 8(1): 015016. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/8/1/015016.

- Farmer, N., K. Touchton-Leonard, and A. Ross. 2018. “Psychosocial Benefits of Cooking Interventions: A Systematic Review.” Health Education & Behavior : The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education 45(2): 167–180. doi:10.1177/1090198117736352.

- Faul, F., E. Erdfelder, A.-G. Lang, and A. Buchner. 2007. “G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences.” Behavior Research Methods 39(2): 175–191. doi:10.3758/bf03193146.

- Fielding, K. S., and M. J. Hornsey. 2016. “A Social Identity Analysis of Climate Change and Environmental Attitudes and Behaviours: Insights and Opportunities.” Frontiers in Psychology 7(121): 1–12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00121.

- Fritsche, I., M. Barth, P. Jugert, T. Masson, and G. Reese. 2018. “A Social Identity Model of Pro-Environmental Action (SIMPEA).” Psychological Review 125(2): 245–269. doi:10.1037/rev0000090.

- Gentina, E., and I. Muratore. 2012. “Environmentalism at Home: The Process of Ecological Resocialization by Teenagers.” Journal of Consumer Behaviour 11(2): 162–169. doi:10.1002/cb.373.

- IPCC 2018. “Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5 °C above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways.” in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107415324.

- Hasan, Bashar, Warren G. Thompson, Jehad Almasri, Zhen Wang, Sumaya Lakis, Larry J. Prokop, Donald D. Hensrud, et al. 2019. “The Effect of Culinary Interventions (Cooking Classes) on Dietary Intake and Behavioral Change: A Systematic Review and Evidence Map.” BMC Nutrition 5(1): 29. doi:10.1186/s40795-019-0293-8.

- Hayes, A. F., and N. J. Rockwood. 2020. “Conditional Process Analysis: Concepts, Computation, and Advances in the Modeling of the Contingencies of Mechanisms.” American Behavioral Scientist 64(1): 19–54. doi:10.1177/0002764219859633.

- Higgs, S., and H. Ruddock. 2020. “Social Influences on Eating.”. In: Meiselman H. (eds) Handbook of Eating and Drinking. Springer, Cham. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-14504-0_27.

- Hunt, P., L. Barrios, S. K. Telljohann, and D. Mazyck. 2015. “A Whole School Approach: collaborative Development of School Health Policies, Processes, and Practices.” The Journal of School Health 85(11): 802–809. doi:10.1111/josh.12305.

- Hussar, K. M., and P. L. Harris. 2010. “Children Who Choose Not to Eat Meat: A Study of Early Moral Decision-Making.” Social Development 19(3): 627–641. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00547.x.

- Jans, L. 2021. “Changing Environmental Behaviour from the Bottom up: The Formation of Pro-Environmental Social Identities.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 73: 101531. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101531.

- Jans, L., T. Postmes, and K. I. Van der Zee. 2011. “The Induction of Shared Identity: The Positive Role of Individual Distinctiveness for Groups.” Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin 37(8): 1130–1141. doi:10.1177/0146167211407342.

- Jans, L., T. Postmes, and K. I. Van der Zee. 2012. “Sharing Differences: The Inductive Route to Social Identity Formation.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48(5): 1145–1149. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2012.04.013.

- Jans, L., C. W. Leach, R. L. Garcia, and T. Postmes. 2015. “The Development of Group Influence on in-Group Identification: A Multilevel Approach.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 18(2): 190–209. doi:10.1177/1368430214540757.

- Judge, M., and M. S. Wilson. 2019. “A Dual-Process Motivational Model of Attitudes towards Vegetarians and Vegans.” European Journal of Social Psychology 49(1): 169–178. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2386.

- Kashima, Y., O. Klein, and A. E. Clark. 2007. “Grounding: Sharing Information in Social Interaction.” In K. Fiedler (Ed.), Frontiers of Social Psychology. Social Communication (pp. 27–77). New York: Psychology Press.

- Koudenburg, N., T. Postmes, E. H. Gordijn, and A. van Mourik Broekman. 2015. “Uniform and Complementary Social Interaction: Distinct Pathways to Solidarity.” Plos ONE 10(6): e0129061. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0129061.

- Koudenburg, N., A. Kannegieter, T. Postmes, and Y. Kashima. 2021. “The Subtle Spreading of Sexist Norms.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 24(8): 1467–1485. doi:10.1177/1368430220961838.

- Kurz, T., A. M. Prosser, A. Rabinovich, and S. O’Neill. 2020. “Could Vegans and Lycra Cyclists Be Bad for the Planet? Theorizing the Role of Moralized Minority Practice Identities in Processes of Societal-Level Change.” Journal of Social Issues 76(1): 86–100. doi:10.1111/josi.12366.

- Lawson, D. F., K. T. Stevenson, M. N. Peterson, S. J. Carrier, E. Seekamp, and R. Strnad. 2019. “Evaluating Climate Change Behaviors and Concern in the Family Context.” Environmental Education Research 25(5): 678–690. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1564248.

- Leach, Colin Wayne, Martijn van Zomeren, Sven Zebel, Michael L. W. Vliek, Sjoerd F. Pennekamp, Bertjan Doosje, Jaap W. Ouwerkerk, and Russell Spears. 2008. “Group-Level Self-Definition and Self-Investment: A Hierarchical (Multicomponent) Model of in-Group Identification.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 95(1): 144–165. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.144.

- Lee, E., K. J. Reynolds, E. Subasic, D. Bromhead, H. Lin, V. Marinov, and M. Smithson. 2017. “Development of a Dual School Climate and School Identification Measure-Student (SCASIM-St).” Contemporary Educational Psychology 49: 91–106. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.01.003.

- Legault, L., and L. G. Pelletier. 2000. “Impact of an Environmental Education Program on Students’ and Parents’ Attitudes, Motivation, and Behaviours.” Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences du Comportement 32(4): 243–250. doi:10.1037/h0087121.

- Lindgren, N. 2020. “The Political Dimension of Consuming Animal Products in Education: An Analysis of Upper-Secondary Student Responses When School Lunch Turns Green and Vegan.” Environmental Education Research 26(5): 684–700. doi:10.1080/13504622.2020.1752626.

- MacInnis, C. C., and G. Hodson. 2017. “It Ain’t Easy Eating Greens: Evidence of Bias toward Vegetarians and Vegans from Both Source and Target.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 20(6): 721–744. doi:10.1177/1368430215618253.

- Masson, T., and I. Fritsche. 2014. “Adherence to Climate Change-Related Ingroup Norms: Do Dimensions of Group Identification Matter?” European Journal of Social Psychology 44(5): 455–465. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2036.

- McGarty, C., A. Bliuc, E. F. Thomas, and R. Bongiorno. 2009. “Collective Action as the Material Expression of Opinion-Based Group Membership.” Journal of Social Issues 65(4): 839–857. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01627.x.

- Minson, J. A., and B. Monin. 2012. “Do-Gooder Derogation: disparaging Morally Motivated Minorities to Defuse Anticipated Reproach.” Social Psychological and Personality Science 3(2): 200–207. doi:10.1177/1948550611415695.

- Öhman, J., and M. Öhman. 2013. “Participatory Approach in Practice: An Analysis of Student Discussions about Climate Change.” Environmental Education Research 19(3): 324–341. doi:10.1080/13504622.2012.695012.

- Poore, J., and T. Nemecek. 2018. “Reducing Food’s Environmental Impacts through Producers and Consumers.” Science 360(6392): 987–992. doi:10.1126/science.aaw9908.

- Postmes, T., S. A. Haslam, and L. Jans. 2013a. “A Single-Item Measure of Social Identification: Reliability, Validity, and Utility.” The British Journal of Social Psychology 52(4): 597–617. doi:10.1111/bjso.12006.

- Postmes, T., S. Haslam, and R. I. Swaab. 2005a. “Social Influence in Small Groups: An Interactive Model of Social Identity Formation.” European Review of Social Psychology 16(1): 1–42. doi:10.1080/10463280440000062.

- Postmes, T., A. Rabinovich, T. Morton, and M. Van Zomeren. 2013b. “Towards Sustainable Social Identities: Including Our Collective Future into the Celf-Concept.” In H. C. M. Van Trijp (Ed.), Encouraging Sustainable Behaviour: Psychology and the Environment (pp.185–202). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Postmes, T., R. Spears, A. T. Lee, and R. J. Novak. 2005b. “Individuality and Social Influence in Groups: Inductive and Deductive Routes to Group Identity.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89(5): 747–763. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.89.5.747.

- Quintana, S. M. 1998. “Children’s Developmental Understanding of Ethnicity and Race.” Applied and Preventive Psychology 7(1): 27–45. doi:10.1016/S0962-1849(98)80020-6.

- Reicks, M., M. Kocher, and J. Reeder. 2018. “Impact of Cooking and Home Food Preparation Interventions among Adults: A Systematic Review (2011–2016).” Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 50(2): 148–172.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2017.08.004.

- Reynolds, K. J., E. Subasic, E. Lee, D. Bromhead, and K. Tindall. 2015. “Does Education Really Change us? The Impact of Social School Processes on the Person.” K.J. Reynolds, N. Branscombe (Eds.), The Psychology of Change: Life Contexts, Experiences, and Identities, Psychology Press, New York & London pp. 170–186

- Rice, S. 2013. “Three Educational Problems: The Case of Eating Animals.” Journal of Thought 48(2): 112–127.

- Rowe, B., and S. Rocha. 2015. “School Lunch is Not a Meal. Posthuman Eating as Folk Phenomenology.” Educational Studies 51(6): 482–496. doi:10.1080/00131946.2015.1098643.

- Sanson, A. V., J. Van Hoorn, and S. E. L. Burke. 2019. “Responding to the Impacts of the Climate Crisis on Children and Youth.” Child Development Perspectives 13(4): 201–207. doi:10.1111/cdep.12342.

- Smith, L. G., and T. Postmes. 2011. “The Power of Talk: Developing Discriminatory Group Norms through Discussion.” The British Journal of Social Psychology 50 (Pt 2): 193–215. doi:10.1348/014466610X504805.

- Snijders, T. A., and R. J. Bosker. 1991. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. London: Sage.

- Spannring, R., and T. Grušovnik. 2019. “Leaving the Meatrix? Transformative Learning and Denialism in the Case of Meat Consumption.” Environmental Education Research 25(8): 1190–1199. doi:10.1080/13504622.2018.1455076.

- Stapleton, S. R. 2015. “Food, Identity, and Environmental Education.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 20: 12–24.

- Staunton, M., W. R. Louis, J. R. Smith, D. J. Terry, and R. I. McDonald. 2014. “How Negative Descriptive Norms for Healthy Eating Undermine the Effects of Positive Injunctive Norms.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 44(4): 319–330. doi:10.1111/jasp.12223.

- Tajfel, H., and J. Turner. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Thomas, E. F., C. McGarty, and K. Mavor. 2016. “Group Interaction as the Crucible of Social Identity Formation: A Glimpse at the Foundations of Social Identities for Collective Action.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 19(2): 137–151. doi:10.1177/1368430215612217.

- Turner, J. C. 1991. Social Influence. Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole.

- Turner, J. C., M. A. Hogg, P. J. Oakes, S. Reicher, and M. S. Wetherell. 1987. Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

- Van Mourik Broekman, A., N. Koudenburg, E. H. Gordijn, K. L. S. Krans, and T. Postmes. 2019. “The Impact of Art: Exploring the Social-Psychological Pathways That Connect Audiences to Live Performances.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 116(6): 942–965. doi:10.1037/pspi0000159.

- Vidgen, H. (Ed.). 2016. Food Literacy: key Concepts for Health and Education. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Vidgen, H. A., and D. Gallegos. 2014. “Defining Food Literacy and Its Components.” Appetite 76: 50–59. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2014.01.010.