Abstract

A substantial body of research highlights the value of nature experience in supporting children’s well-being and development. Given the growing interest in connectedness to nature (C2N), a better understanding of C2N measurement provides multiple opportunities, including consideration of the use of tools for research purposes and practitioner program measurement. The combination of interest in C2N and the potential for measuring the human relationship with nature provide the background for this exploratory study. The study’s goal was to highlight the appropriate use of C2N scales based on considerations of context and culture. Three different, albeit related, efforts to translate, adapt, and use C2N measurements with children in a Danish-Swedish context during 2021–2022 were examined using case study methodology. Synthesis of the case studies provides general lessons and specific insights researchers and practitioners have learned regarding scale development and the application of measurement tools for children. Process functionality, child well-being, and conceptual appropriateness are three outcomes of the analysis that guide using child-oriented C2N scales in a Nordic context. The results highlight promoting discussions about nature and children’s access to nature while guiding scale use. Based on the results, a checklist was created supporting a decision-making process for scale use.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS:

1. Introduction

Recent research highlights the value of nature experience to support connectedness to nature (C2N) (Beery et al. Citation2020; Barragan-Jason et al. Citation2022; Chawla Citation2020). This interest comes from a broad foundation in many subject areas, including environmental education, environmental psychology, health promotion, landscape architecture, and human geography. The interest in children’s C2N and the idea of connectedness to nature through the life course (Wells and Lekies Citation2006) has also increased interest in the need to understand the measurement of C2N.

Increased interest in measurement ranges from practical questions regarding implementation and application to consideration of the properties of measurements, such as validity and reliability (Rosa et al. Citation2023; Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020; Taber Citation2018). A concern exists that interest in measurement may serve to reinforce a potential overreliance on educational testing; on the other hand, a better understanding of C2N measurement provides at least four opportunities:

Increased knowledge about C2N measurement tools.

Evaluation of environmental education interventions, programs, and practices promoting C2N (Salazar et al. Citation2021); C2N measurement tools may support having valid and reliable methodologies to consider outcomes of environmental education programming.

Data to support a more explicit inclusion of children in ecosystem services/nature contributions to people, policy, and planning (Beery and Lekies Citation2021).

Opportunity to go beyond individual testing and contribute to a standardized global testing culture (Martin, Ives, and Carney Citation2023). Such an opportunity may offer a chance to facilitate a relational dialog (between research, practice, and policymakers) about people as part of nature (Beery, Citation2014).

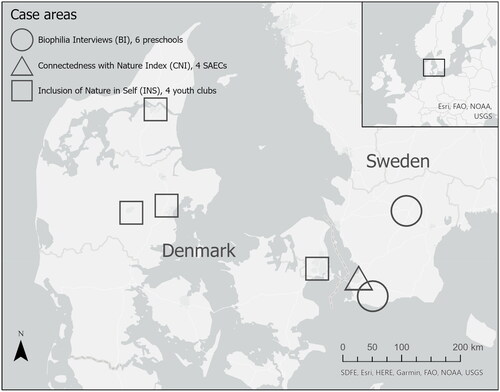

The combination of interest in C2N and the potential for measuring the human relationship with nature provide the background for this research–an exploratory study of the appropriate use of C2N scales based on considerations of context and culture. This interest is coupled with a unique alignment of three different, albeit related, efforts to translate, adapt, and use C2N measurements with children in a Danish-Swedish context during 2021–2022 (see ). This interest in scale adaptation and use represents the research focus; however, the study also intends to consider scale use from practitioners’ perspectives, given the similarities between the three efforts. The broad goal of the study is to address the question of what can be learned regarding scale use with children from three C2N measurement case studies in a Nordic context. Moreover, beyond an application in the Nordic context, what can be learned regarding psychometric scale use in general, and how can this support researchers and practitioners in expanding the scale use decision-making process?

Figure 1. Location of the cases where the three different C2N scales were applied (SAEC = school-age educare).

Note that this application of C2N measurement tools is not the first known adaptation of C2N scales from English to Nordic language/context. Beery (Citation2013) previously used several scales (Connection to Nature Scale, Nature Relatedness Scale, and Inclusion of Nature in the Self Scale) to validate a three-item Swedish C2N scale. While this previous effort established validity and internal consistency for the three-item Swedish scale, the target audience was an adult population, and the focus context was nature-based outdoor recreation. This current study turns its focus to children and institutional childhood education-oriented settings.

2. Background

This section provides a brief background on content and process. Drawing heavily on the literature detailing the benefits of nature experience to support childhood C2N, a foundation to better understand scale use has been established. A brief background of C2N measurement with children is presented. Finally, a general overview of case study methodology provides a background for the study methods.

2.1. Connectedness to nature

The broad interdisciplinary concept of C2N captures the degree to which people feel a part of nature (Mayer and Frantz Citation2004) and perceive nature within a cognitive representation of the self (Schultz Citation2002). C2N has been described in numerous similar, albeit unique, ways using terms such as biophilia, inclusion, and relatedness (Beery and Wolf-Watz Citation2014). One reason for so many nuanced definitions for and approaches to considering C2N is based on concern for the outcomes of a diminished human experience of nature (Louv Citation2005; Pyle Citation1993; Soga and Gaston Citation2016, Citation2021). These concerns include loss of educational opportunity (affective, cognitive, and psychomotor learning) (e.g. Gaston and Soga Citation2020; Ives et al. Citation2018; Genc, Genc, and Rasgele Citation2018; Lim et al. Citation2017). In addition, concerns include the loss of opportunity for developing pro-environmental attitudes and behavior (e.g. Schultz Citation2002; Mayer and Frantz Citation2004; Mayer et al. Citation2009; Davis, Green, and Reed Citation2009; Restall and Conrad Citation2015; Barragan-Jason et al. Citation2023).

Concerns and consequences regarding this potential loss of crucial human-nature interaction have resulted in a breadth of C2N research to focus on the importance and possibility of a conscious pursuit of C2N (e.g. Barragan-Jason et al. 2022, Citation2023; Barrable Citation2019; Zylstra et al. Citation2014; Nisbet and Zelenski Citation2011). In this literature, C2N is viewed as a state to be deliberately pursued through various pathways, including teaching outside the classroom (Waite Citation2009), specific pedagogies (Barrable Citation2019), or direct intervention (Richardson and Butler Citation2022). Furthermore, childhood is emphasized as a critical arena for the deliberate pursuit of C2N (Beery et al. Citation2020; Price et al. Citation2022; Richardson et al. Citation2016; Wells and Lekies Citation2006) given both concerns for child well-being and development and not least, the potential for childhood C2N to show a relationship with C2N across the lifespan (Chawla Citation2020; Mygind et al. Citation2019; Rosa, Profice, and Collado Citation2018; Wells and Lekies Citation2006).

Given this interest in children’s C2N, it is essential to consider children’s access to opportunities that may support C2N. Such considerations can happen in many ways, for example, through physical/spatial considerations of children’s home/community environments or family-based attitudes and behavior regarding nature experience (Beery et al. Citation2023; Chawla Citation2020; Cheng and Monroe Citation2012). Moreover, supporting the development of C2N can be considered through the role of institutions and organizations in children’s daily lives (e.g. preschool, school, extended care, and youth clubs). Considering this institutional opportunity to promote C2N in the Nordic countries is warranted, given Denmark and Sweden’s high participation rates in institutional childcare/educational settings. For example, beyond mandatory school requirements for children in Denmark and Sweden, it is estimated that 86% and 95% of children aged 1–5 participate in early childhood programs (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2022; Statistics Denmark Citation2015). Furthermore, 82% of children aged 6–9 participate in after-school leisure programs in Sweden and Denmark (Klerfelt and Haglund Citation2014; Statistics Denmark Citation2015).

2.2. Measurement of children’s connectedness to nature

Demand for programs and curricula to support C2N is reflected in the growth of resources that explicitly focus on C2N as a goal for their programs; for example, curriculum guides and organizations dedicated to the topic of children and nature, such as The North American-based Child and Nature Network, or the Danish-based Children and Nature - Denmark (CN&N Citation2023; Præstholm Citationn.d.; Richardson and Butler Citation2022). Given this interest, having the ability to measure connectedness to nature is viewed as helpful to a wide range of educational, environmental, and youth professionals because this concept is both an outcome of experience and a potential indicator of well-being and conservation behaviors (Beery and Lekies Citation2021). We recognize that the desire for measurement may take different/multiple forms. Programs may need measurements to provide evidence of outcomes for ongoing support from outside entities (Head Citation2016). Alternatively, programs may want an increased internal awareness of learning outcomes (Carleton-Hug and Hug Citation2010).

These current efforts to consider the measurement of C2N are part of a childhood education effort that originated in 2018. A participatory process involving researchers and practitioners in reviewing existing C2N assessment tools was initiated in conjunction with the North American Association for Environmental Education (NAAEE) Research Symposium 2018. This undertaking resulted in the Practitioner Guide to Assessing Connection to Nature and scientific articles outlining that process (Beery et al. Citation2020; Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020; Salazar et al. Citation2021). The NAAEE effort highlights that this current inquiry is not new, nor stand-alone, but rather a part of ongoing research progression focused upon deepening understanding of childhood C2N and ways to measure it. The Practitioner Guide process (Salazar et al. Citation2021) includes a careful review of 26 C2N scales/measurement tools conducted by 23 practitioners and researchers in the C2N field. The final guide included 11 scales/measurement tools based on this deliberate process.

A specific example of the Practitioner Guide review effort, applicable to this current consideration of scale translation and application, is the outcome of the Biophilia Interview (BI) review process for possible inclusion in the Practitioner Guide (Beery et al. Citation2020). Upon reflecting on the assessment of C2N for 2 to 5-year-old children, a nine-member expert panel encouraged a mixed methods approach, noting strengths and limitations in both qualitative and quantitative approaches to C2N measurement. In addition, a playful, game-like format for measurement was recommended. The expert panel also noted the value of multiple sources, such as teachers and parents, in addition to children directly. While this effort was focused on early childhood, the results nonetheless were deemed helpful for consideration of C2N measures with children 6–10.

This robust consideration of the BI in the Practitioner Guide process was an effort to take the scale review to a deeper level (Beery et al. Citation2020); such consideration also fits with a critique of how statistical testing is used to assess reliability. For example, despite the widespread use of Cronbach’s alpha as a measure of international consistency/reliability (e.g. Navarro, Olivos, and Fleury-Bahi Citation2017; Rosa et al. Citation2022b; Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020), a reliance upon Cronbach’s alpha for measures of internal consistency is questioned (Kane Citation2013; Taber Citation2018; Van Bork, Wijsen, and Rhemtulla Citation2017). Tabor (2017) urges a greater awareness of possible limitations and broad representation of other complementary statistical measures. Rosa et al. (Citation2023) also urge caution and assert that additional approaches are needed to gain perspective on the interrelatedness of scale items. For example, expert review is encouraged, where experts in connectedness to nature can be provided with the construct definition and asked to indicate whether they think all the items of the scale are relevant and comprehensive for a particular construct and if the items cover all aspects of connectedness to nature (Rosa, Collado, and Larson Citation2022a; Terwee et al. Citation2018). Nonetheless, despite these noted concerns about over-reliance on Cronbach’s alpha as an exclusive measure of internal consistency, these scores are reported in the following case studies. This reporting is in accordance with how reliability was considered in developing the Practitioner Guide.

2.3. Case study methodology

This research combines three cases where C2N scales have been applied and investigated, given that case study methodology allows for in-depth investigations of complex issues in real-life settings (Crowe et al. Citation2011; Yin Citation2009). Three cases have been selected for several reasons in line with case study method guidelines, including:

All three projects have coincided in time.

All three cases share a geo-cultural-educational connection. All are set in a Danish-Swedish context with cases in Capitol Region, Central and Northern Jutland in Denmark, and Scania in Sweden.

All three projects focused on scale use, albeit different scales, to consider C2N outcomes in an educational context.

Finally, all three cases represent community partners hospitable to this inquiry.

Case study methodology usually uses multiple data types to create a picture that is as comprehensive as possible (Crowe et al. Citation2011). For example, all three cases explored in this research presented quantitative and qualitative data collection methods. Survey results from participating children were coupled with teacher observations about use, process, and fit. Finally, given the researcher’s involvement at each site, researcher field notes were consulted in the analysis process.

3. Case studies: methods and case outcomes

Three cases are presented in this section to address the research question presented in the introduction: what can be learned from three C2N measurement case studies in a Nordic context?

The Biophilia Interview (BI) tool applied in Swedish preschool settings in the county of Scania Sweden.

The Connectedness with Nature Index (CNI) applied in school-age educare settings in Malmö, Sweden.

Inclusion of Nature in Self Scale (INS) applied in Danish after school clubs (in Capital Region, Central and Northern Jutland) for children in socio-economically disadvantaged areas.

Each case is presented with a brief background on the measurement tool, the site context, the scale implementation, and a summary of the outcomes. Each outcome summary combines the available data for each case.

3.1. Biophilia interview in Swedish preschools

The BI constitutes an 11-item interview using puppets individually administered to children aged 3–5 (Rice and Torquati Citation2013). An interviewer uses two identical gender-neutral puppets and changes the gender of the puppets to match the interviewed child by saying “this boy” or “this girl.” Non-biophilic and biophilic statements are made for the puppets, and children are asked questions about which puppet they are most like, for example: “This boy (puppet) likes to watch birds, and this boy (the other puppet) does not like to watch birds. Which one is more like you?” The child is intended to pick the puppet most closely resembling his/her interests. Non-biophilic responses receive a score of 0, and biophilic responses receive a score of 1, for a maximum score of 11. Details about previous uses, including internal consistency and validity testing, are concisely detailed in the Practitioner Guide to Assessing Connection to Nature (Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020).

3.1.1. Case description

The study aims to investigate how Swedish preschool teachers view the BI as a potential tool for assessment. Swedish preschool is a voluntary and separate school form, subsidized nationally, with municipalities required to provide a place in preschool settings for all children. The Swedish curriculum for early childhood states that preschool should provide each child with the conditions to develop specified goals (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2018). Children’s knowledge is not measured, but early childhood teachers reflect on each child’s development as part of the assessment process. Preschool teachers are licensed with a university degree in early childhood studies.

The BI was translated to Swedish by native Swedish speakers (with English language competence) working within early childhood education (research and practice) and a native English speaker (with Swedish language competence) working in environmental education (research and practice). The need for a careful iterative process of language translation with speakers of both languages was acknowledged and guided the process (Tsang, Royse, and Terkawi Citation2017). Based on the iterative translation process, adjustments were made in the text of the instrument, but the original meaning of the BI was ensured by a discussion with one of the scale’s creators; this outreach was done in hopes that the translation would not interfere with measures of reliability and validity (Alikari et al. Citation2021).

Six preschools in three municipalities in southern Sweden participated in this case study. The research team established a research protocol aligned with the translation process. The number of children for each preschool varied between six and ten, and the preschool teachers selected the children based on their ability to understand the questions and express opinions. The interviews were completed over two weeks. A research assistant with experience in children’s theater was recruited to perform the interviews. The research assistant switched attitudes between the puppets to ensure that the same puppet did not have all the positive/negative statements; however, she always started with the puppet representing the biophilic statement.

3.1.2. Scale implementation

Fifty-five children between 3 and 5 years of age were interviewed: 21 girls (38%) and 34 boys (62%). In Sweden, the early childhood curriculum states how preschool teachers should inspire and challenge children to broaden their abilities in a way that goes beyond gender in stereotypical ways. In line with this, two gender-neutral puppets were chosen for the interviews. However, during preparations, the sentence "This boy/girl likes to…" was changed to "This puppet likes to…"; the research team decided that dropping gender identification did not change the interview focus.

Present at each interview was a preschool teacher, henceforth called "practitioner," known to the children. This participation enabled the researchers to capture practitioner perspectives and allowed the research assistant to manage the puppets while the practitioner took notes during the BI. Having a known person in the room enabled a secure environment for the children during the interview. While the participating children’s parents had given written consent to the interviews, children were free to opt out if they expressed hesitation or discomfort. Children’s names were not collected. This effort to protect the child’s rights reflects the values and rights expressed in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) and according to the guidelines in the Swedish Research Council (Citation2017).

One of the researchers conducted follow-up semi-structured interviews with one practitioner per research site to gain their perception of the process approximately one month after the BIs were conducted. In total, five of the six practitioners were interviewed.

3.1.3. Summary of outcomes

In the BI, a score between 0 and 5 reflects low biophilia, 6 represents neutral biophilia, and 7–11 is high biophilia. Fifty-five children participated in the BI; four answered seven or fewer of the eleven questions; data from these four participants has not been included, resulting in an adjusted total of 51 participants. Using SPSS 27 for analysis, the data yielded a mean BI score of 7.6 (σ = 2.7). A test for internal reliability for a scale with dichotomous items was conducted, a Kuder-Richardson 20 test (providing a Cronbach’s alpha statistic), and yielded a result of 0.84, a possible indicator of good internal consistency.

The practitioners viewed the results as reflecting their experiences with the children. One practitioner stated that the children who chose the biophilic answers were those who experienced outdoor recreation with their families. In contrast, the more negative answers came from children who get tired and appear uninterested when the practitioners are out in nature with them. Some children’s answers surprised the practitioners. "Why did [the child] answer negatively to "playing outside" when I know how much s/he seems to enjoy it?" These surprises lead the practitioners to reflect on the meaning the children give to the questions. Could practitioners not be aware of the children’s innermost feelings, or could the child think of something concrete outside at the interview, e.g. riding a bike, that they do not like to do? One practitioner was surprised when several children in her group answered negatively regarding playing in creeks and playing with sticks. It made her reflect on school risk management and how they often warn the children not to go too close to a nearby creek and to be careful when they play with sticks. Are the negative answers reflecting what the children think the observing practitioner wants to hear more than an honest opinion? Or are the practitioners’ warnings making some children afraid of the creek? In addition, the research assistant reported that she had to explain the word ‘creek’ to several children, indicating language issues.

When the practitioners reflected on the role of the research assistant in the BI, several focused on the importance of a trusting relationship between the interviewer and the children. According to the practitioners, the research assistant managed to create trust based on her ‘way’ with the children and her attention to children’s needs. The research assistant reflected on the dilemma that arises when, as an adult, one meets children in a novel interview situation. Children might feel pressured to deliver ‘correct’ answers to please the adult in a power position. On at least one occasion, she felt a child being stressed about this and decided to end the interview for the child’s sake. On the other hand, a practitioner reported on the reaction of some children not interviewed (based on a lack of parental written consent), noting that these children were upset that they were not interviewed; they, too, wanted to talk to the puppets! Hence, including and excluding children in the BIs could constitute a dilemma.

The practitioners and the research assistant acknowledged the impact of the interview environment. It was clear from the practitioners’ reflections that the setting was beneficial, i.e. an external interviewer and a familiar participating practitioner. For example, when children pointed to one of the puppets, the practitioner could see if it was meant as a joke or if the answer seemed to deviate from how that child normally behaved. The practitioners’ sometimes surprised reactions to the children’s choices stress the importance of a person present, either in the role of interviewer or by-stander, who knows the children. Adjustments, such as re-positioning the child/puppets/researcher so that they all were sitting on the same level, e.g. on the floor, were made to create a comfortable interview environment for the children.

Another issue the research assistant and several practitioners mentioned was the length of the questionnaire. Overall, the children got tired after about half of the 11 statements, and the research assistant commented on how she had to work harder with the puppets to keep the process enjoyable. This effort made the "low biophilia" puppet funnier than the other puppet. Maintaining a neutral handling of the puppets so that children were not manipulated into a specific answer while keeping the puppets fun and exciting was described as challenging by the research assistant.

Another reflection made by a practitioner was how one pair of statements in the questionnaire was tricky. "This child likes to look at the stars and moon at night" versus "This child would rather play indoors at night" does not necessarily reflect the same thing. A child could focus on the word ‘play’ and prefer that or like to be up at night but not looking at the stars. In conclusion, the wording and length of the interview guide could be further developed.

When practitioners were asked to evaluate the BI concerning assessing children’s learning, most found it too blunt to be useful. The practitioner reflected on how the puppets only capture a yes or no. At the same time, their standard assessment tools include in-depth discussions with each child about photographs the children have taken themselves, what the child thinks s/he learned, and how. In contrast, one practitioner reflected on the benefit of assessing children’s thoughts more straightforwardly, such as with the BI. Sometimes, she reasoned that it could be convenient for children not to articulate their thoughts. Some children feel pressured when they need to put words to feelings and opinions, and she reflected that pointing to a puppet and choosing one of only two alternatives may ease anxiety.

An overview of the findings of the BI used in Swedish preschool settings is presented in .

Table 1. Biophilia Interview process data.

3.2. The connectedness with nature index applied in school-age educare in Malmö, Sweden

The CNI (Cheng and Monroe Citation2012) was chosen for use in Swedish school-age educare (SAEC) settings based mainly on the literature on C2N and information provided in the Practitioner Guide to Assessing of Connection to Nature (Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020). This source was used based on the effectiveness of aligning a measurement with a particular group and context. For example, the CNI scale is designed for children 8–10 years involved in a high-intensity program. These criteria are a close match with the participating Malmö schools in terms of intensity (year-long program) and ages; in Malmö, the children range in age from 6 to 12, with most being in the target age range of 7–9. The CNI consists of 14 Likert scale items that measure a child’s feelings about C2N. Consideration also included knowledge that the scale has been used previously (e.g. Bragg, Wood, and Barton Citation2013; Cheng and Monroe Citation2012); details about previous use, including internal consistency and validity testing, are concisely presented in the Practitioner Guide to Assessing Connection to Nature (Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020).

3.2.1. Case description

While often viewed as a culturally unique institutional setting, Swedish School-Age Educare is similar to many other after-school care programs, i.e. sites where children are supervised and provided with education and play opportunities at the beginning and end of the school day (Boström, Elvstrand, and Orwehag Citation2022; Haglund and Boström Citation2022; Lago and Elvstrand Citation2022). SAEC is a recognized part of elementary education in Sweden. Swedish school for 6–9-year-olds consists of three scholastic forms: preschool, elementary school, and SAEC (Lager Citation2015; Andersson Citation2013). These are regulated through various parts of a common curriculum with a complementary aim of holistically supporting child development and learning throughout the first four school years (Skolverket Citation2022). SAEC is a non-compulsory (Elvstrand and Närvänen Citation2016) care-based social arena (Calander Citation2001) with a particular leisure pedagogy (Lago and Elvstrand Citation2019). SAEC differs from formal school settings based on a strong focus on free play (Holmberg and Kane Citation2020), curiosity, and intrinsic motivation-driven activity (Halldén Citation2007). SAEC teachers are licensed with a university degree in education.

An intervention in four Malmö area SAECs was developed to explore multiple data sources regarding children’s C2N, including data from a psychometric scale (pre- and post-intervention data collections) and post-test qualitative semi-structured interviews. Four SAECs in the urban area of Malmö, Sweden, are included in this ongoing study. The initial data presented here represents 142 child participants.

Similar to the description of the challenges faced using the BI in a Swedish preschool setting, there is a lack of experience with using the CNI in a Nordic context. To our knowledge, the CNI was used only one other time in a Nordic language/cultural context (namely, in the early stage of the Danish case, see section 4.3). Given this lack of experience, the research team undertook a process of translation and cultural adaptation (Klarare et al. Citation2021) almost identical to the process employed in the BI translation. The CNI was carefully translated into Swedish by a native Swedish speaker (with English language competence) working within education (research and practice) and a native English speaker (with Swedish language competence) and environmental educator (research and practice) (Tsang, Royse, and Terkawi Citation2017). Based on the iterative translation process, adjustments were made in the text of the instrument, but the original meaning, internal consistency, and construct validity of the CNI were supported by a discussion with the original scale authors (Alikari et al. Citation2021).

3.2.2. Scale implementation

The pilot scale draft was text-based, i.e. to be presented to children in language form. The pilot test was conducted at one of the participating schools with small groups of approximately eight children per group. The pilot test was conducted with a young group (predominantly 6-year-old children) and older groups (7–9-year-old children). The researcher sat with each group and read and explained each item to the children; the researcher reminded children to respond with their own opinions and allowed questions. The test was conducted in a familiar classroom with their SAEC teachers in attendance.

The pilot test was a successful event as far as a generally positive response from the children and interesting interactions between the researcher, children, and teachers. The text-based form, however, was deemed inappropriate for the children’s language skills. This particular SAEC was similar to at least two more SAECs regarding children with a broad range of language backgrounds. With the youngest child group, the researcher stopped the process after three questions based on the observation that some children appeared uncomfortable and others were not fully engaged in the process; instead of pilot test completion, the researcher and children sat on a big rug and talked about nature including the topics of wild animals, plants, flowers, rocks, and shells in an attempt to have a positive nature-oriented (non-measured) experience.

As a follow-up to the pilot testing, the researchers reached out to the scale creators with questions about particular items and possible adaptations; these questions were well received, eliminating concerns of misuse or misunderstanding on the part of the research team in Sweden. Edits based on communication with scale creators and concerns from use with the younger child group resulted in several changes. Given the language challenge, an emoji-based Likert scale replaced text to help children understand the response options (see for a sample); an emoji-based Likert scale has been used previously with young children (Bragg, Wood, and Barton Citation2013). Other emoji-based Likert scale applications supported our use of this form of scale communication (Massey Citation2022). The total number of items was reduced from 14 to 10 to make the experience more positive and child-friendly. Cues for each question were developed and used consistently at all sites. The emoji-based responses, the shorter scale, and the consistent cues seemed useful and appropriate in subsequent testing (the other three schools in the project).

3.2.3. Summary of outcomes

With the CNI, scores of 1–2 indicate a lower connectedness to nature; a score of 3 indicates neither a low nor a high connectedness; and scores of 4–5 indicate a higher level of C2N. One hundred and forty-two children participated in the CNI. Using SPSS 27 for analysis, the data yielded a mean CNI score of 4.3 (σ = 0.63); a Cronbach’s alpha test for internal reliability was conducted, resulting in a score of 0.74, indicating possible support for internal consistency. See for results.

Table 2. CNI process data.

At each school, the researcher had time to talk with teachers and make minor adjustments to fit a given school’s context-oriented elements. The teachers were generally helpful and interested in the process. A formal individual assessment environment was not created with scale-use sessions; the hope was to create as comfortable an environment as possible. The SAEC environment is generally one of high energy and movement; there was a deliberate attempt to keep the testing time short and lively (ongoing discussion) so that it would fit the existing atmosphere. Efforts were undertaken to remind children to answer independently and to state their opinions; nonetheless, social interaction was considerable, and peer agreement appeared to be a confounding variable. A blatant example of this was the verbal discounting of the final CNI question, which asked children to respond to the level at which they perceived themselves as a part of nature; numerous children had loud and forceful responses to the final question that may have impacted others. One-on-one testing to avoid such concerns was considered but ultimately rejected, given the potential to create an uncomfortable context for the child. An overview of the findings of the CNI used in Swedish SAECs is presented in .

3.3. Inclusion of Nature in Self Scale (INS) applied in Danish youth clubs

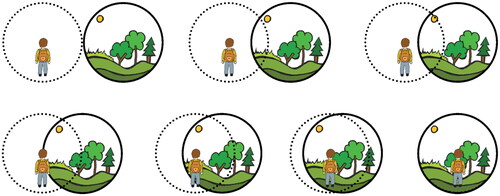

INS provides a simple measure of the degree to which the respondents include nature in their views of themselves. The degree is visualized by seven illustrations ranging from the first showing two circles named “me” and “nature” with no overlap to the last showing the complete overlap between the two circles. INS was developed by Schultz (Citation2002), and it has proved consistent with other scales of C2N (Bragg, Wood, and Barton Citation2013; Richardson et al. Citation2019; Kleespies et al. Citation2021). The measure can be applied to children from seven years of age (Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020). As reported in the Practitioner Guide to Assessing Connection to Nature (Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020), the INS is thought to be valid based on positive correlation scores on other scales that measure environmental attitudes and behavior; however, internal consistency for INS cannot be determined because it is a single-item test.

Kleespies et al. (Citation2021) elaborated the visual design of the scale by including an illustration of a person (me) and a landscape with natural features of a stream, trees, flowers, green surfaces, and mountains (nature) in the circles. This design inspired the evaluation of the Danish case – the so-called “Nature Clubs” that provide weekly after-school nature-based activities for children in socio-economically disadvantaged housing areas.

3.3.1. Case description

The Danish case represents activities hosted by volunteers from the NGO Save the Children Denmark (SCD) during children’s free time outside preschool or school. In 2019, SCD initiated the Nature Clubs project for children aged 6–15 in socio-economically disadvantaged housing areas by offering weekly nature-based activities with volunteers. The children’s families were invited to take part in the activities monthly.

The idea behind the project originated ten years ago with different types of nature-based activities, e.g. for refugees and families in socio-economically challenged positions (Skytte et al. Citation2019). SCD wanted to develop these activities and document possible outcomes regarding well-being, more use of local green spaces, and a stronger C2N. An external consultancy company planned the evaluation, including pre-and post-intervention questionnaires (after one year). Researchers from Children & Nature Denmark, a partnership between four universities and two national NGOs – were partly involved in the evaluation design and eventually also in the collection of data, which is the background for including this case in the present context.

An evaluation in 2019 of the first two pilot Nature Clubs included a Danish version of the CNI (Cheng and Monroe Citation2012) inspired by learnings from testing different measures in the UK (Bragg, Wood, and Barton Citation2013). Meanwhile, the questionnaire proved to be far too complicated for the children to answer, irrespective of help from the club volunteers. Consequently, the 16 items CNI and several other questions were skipped in successive evaluations. Eventually, in 2021, ambitions to measure C2N before and after a season with Nature Club activities resumed by applying the far simpler measure of INS based on Kleespies et al.’s experiences (2021). Learnings from the application of INS constitute the focus of the case. However, preliminary failing experiences with implementing CNI represent important supplementary learnings (Bølling and Præstholm Citation2023).

3.3.2. Scale implementation

The visualization of “me” and “nature” circles by Kleespies et al. (Citation2021) is not aligned with Danish natural environments, as there are no mountains in Denmark. Hence, alternative illustrations included a terrestrial environment significant to rural and urban settings. Different versions of the accompanying question to the illustrations were tested with several groups of children before applying the final version of INS in the pre-questionnaire for the 2021–22 season in selected Nature Clubs, see .

3.3.3. Summary of outcomes

The translation of the accompanying question into the Danish language proved difficult; the notion of (how) “interconnected” (are you with nature) was considered especially problematic to translate literally. After discussions between researchers, SCD professionals, and volunteers, several tests with different wordings were performed with children aged five to ten. A final translation was decided upon by phrasing “interconnected” as “a feeling of being close to nature.”

Unfortunately, the SCD volunteers reported doubts about the trustworthiness of the answers to INS in the pre-questionnaires in the four nature clubs by autumn 2021 (55% of the 29 responses complied with the highest level of interconnectedness, see ). Many children seemed to understand the word “close” literally: they started considering the distance to the nearest grass, scrub, or tree. The natural-looking illustrations in the circles might have made the respondents consider a concrete understanding of distance instead of feeling emotionally close to nature. However, some volunteers also found it fruitful that the question started reflections and discussions among the children:

Table 3. INS process data.

The question about relation with nature was difficult to most, but good. It initiated talking/thinking. It varied if the children perceived it as about physical nearness to nature (I live nearby trees) or as relation with nature. (written reflection from a SCD-volunteer in Aalborg 2021)

A cultural bias in understanding the word ‘nature’ might be an important challenge regarding the question. This challenge was raised by one of the volunteers when applying the CNI in the early phase of the two pilot Nature Clubs in 2019:

The questions are too unclear to them…[]…think if you are not visiting the nature already, and that was the issue with these children, then it is very hard to say what influence it [the nature] has on you. (Bølling and Præstholm Citation2023)

I don’t think their parents ever take them to nature…[]…this going outdoors to play, experience and invent games, or all the adventures you can make up for yourself during play, I don’t think they ever do. They are indoor children and very much online-kids.

Participating in the Nature Club activities is voluntary. This open option means the children might only come if motivated to participate. Also, the volunteers must find preparing and guiding the club activities rewarding. Hence, implementing an evaluation might conflict with the interests of both children and volunteers if it is problematic for the children to answer the questions. Volunteers may need to spend time helping in cases where children need assistance understanding the questionnaire and refuse to participate.

The volunteers criticized the first evaluation design (2019). They further felt it disturbed the activities to perform the pre-test (baseline) already from the very first gatherings of the Nature Clubs:

…I was not too enthusiastic about how easy it would be to carry out. I kind of expected that it would be difficult. I am usually someone that is not giving up. I simply got so affected by it. (Bølling and Præstholm Citation2023)

After further testing with a post-questionnaire for the end of the season 2021–22, it was decided to abandon the use of INS during summer 2022 due to the revealed problems. The cancelation of the use of INS included ethical discussions, worries about the trustworthiness of the answers, and the SCD’s concerns about the motivation of the volunteers in the clubs.

4. Results

The fundamental question of whether the scales would prove helpful in understanding the outcomes of each program was the driving force in each case study. However, the three cases’ conceptual, geographical, and timing overlap provided the foundation of inquiry for this study; the overlap provided a unique opportunity to consider specific experiences more broadly. The objective of this study was to combine all three cases and analyze them collectively. A case study synthesis was conducted by the researchers involved with each case study. Themes from each case were presented by the specific case researchers (two researchers per case study) and discussed by the entire research team in an iterative process; for example, each team presented their work and preliminary themes derived from the case and discussed it with the other researchers. Moreover, the theme discussions required outreach to practitioners in two of the three studies to confirm data interpretation. This process resulted in a list of themes highlighting the most meaningful outcomes. highlights key themes from each case study.

Table 4. Case study synthesis: key themes.

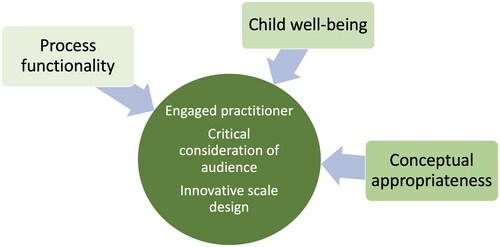

From the critical themes identified in the research process, a deeper consideration of how these themes fit together broadly for consideration in other contexts was conducted. While the focus of this study is the three Nordic cases, the outcomes of this research may be transferable to other contexts (Bloomberg and Volpe Citation2018). This continued analysis effort resulted in the identification of three meta-themes:

Process functionality (time, language, adult support, group size, and research process).

Child well-being (time, language, adult support, age appropriateness, group size, respect).

Conceptual appropriateness (language, nature experience accuracy, age appropriateness).

Each of these meta-themes is presented in the following sections.

4.1. Process functionality

Numerous themes combine to comprise a meta-theme of functionality. At the fundamental level, the length of time children were asked to focus on the scale was a consideration in each of the case studies; the time required to conduct the test needed not to be so long as to tire or bore the participants as considered in the BI and CNI application; time was also a concern with the INS with the practitioners employing the scale concerned about the time lost to other program activity, for example, when implementing the pre-test parallel with the start-up of the club activities; these time concerns were probably influenced by the fact that children attended the Nature Clubs for only a few hours weekly.

These questions of time led to the adjustments of the CNI. Possibly related to the CNI time dimension was language (written answer form); adjustments to the CNI led to a reduction in the total number of items and an abandonment of the written language response checklist version in place of an emoji-based response sheet al.so constituting a language challenge is the concrete versus abstract wording in the questionnaires. Scale wording needs to be concrete enough for children to associate the question or statement with their previous experience and understanding but not too concrete since children need to generalize and think abstractly for their answers to reflect their connectedness to nature. This dilemma also accounts for graphic illustrations of “me” and “nature” applied in INS; the illustrations showed images from no gap to a total gap between the child and nature; some children may have been estimating a concrete distance to natural features in answering rather than considering a general relation with nature.

Functionality beyond time and language also included aspects of each case study experience, such as adult involvement, group size, and research process. The BI and CNI cases both had results that indicated the importance of an adult sensitive to the setting and context in guiding and nurturing the research process of the data collection, looking out for challenges and concerns such as child discomfort, evident confusion, or child-to-child disruption. The overall setup for comfort, efficiency, and consistency was closely related to the aspect of adults as process guides; for example, this role includes well-organized materials, consistent sequencing, prepared cues for each item statement, and awareness of child confusion.

4.2. Child well-being

Considering child participant well-being provides clear examples of how meta-themes often share subthemes. For example, time considerations were about maintaining child participant focus in the data collection and concern for their comfort. This concern for child comfort included language appropriateness, related to age and first language, and group size-related aspects. Concerns were raised regarding the power balance, where some children non-verbally expressed discomfort during BI and CNI but were still eager to please the interviewer by answering. These considerations together resulted in a deliberate effort to respect the child participants. For example, in the CNI small group testing context, the researcher supported CNI scale use through reading and discussing questions with the children. Alternatively, in the case of the INS, the decision to drop the test was partly based on meeting the children’s interests and engagement. The research team discussed research ethics regarding these questions of child well-being. While none of the specific aspects rose to a potential ethical breach, the focus was on well-being, including ethical considerations, to ensure the research process was respectful to the child participants.

4.3. Conceptual appropriateness

This particular meta-theme, conceptual appropriateness, is of great interest regarding whether the scale applications measured the concepts of interest, i.e. the children’s C2N. Three distinct methods of communication were applied to the interaction with participating children: interaction with puppets (BI), an emoji scale survey (CNI), and an image representing C2N (INS). In the BI case, the children’s teachers generally agreed with the outcomes, i.e. the measure indicated general construct validity between their knowledge of the children and the children’s responses; note some of the teachers saw the instrument as blunt and limited in its ability to provide information, they nonetheless perceived it as generally accurate. In the INS case, the question of whether the children had adequate prior nature experience to understand the intended connotation of the scale’s graphic image was raised.

In the CNI application, the researcher noted ongoing child confusion during two pilot attempts with the youngest children (ages 5–7). While the specific underlying reason was not pinpointed, the observation of child confusion was partly interpreted as children not understanding the process and the questions, i.e. a discussion of nature, inclusive of making scale-based choices, was novel and outside of many of the children’s understanding; much of the child response relates to the previous meta-theme of child well-being. Still, the conceptual understanding of nature and the testing process was a probable underlying reason for the confusion.

5. Discussion

This paper considers three C2N measurement initiatives bound together by time, geography, and intent. The broad goal of the study analysis was to consider possible general lessons and specific insights for researchers regarding connectedness to nature scale use from a synthesis of three case studies in a Nordic context; lessons learned support practitioner decision-making regarding scale use. This section considers how to apply the outcomes of the case study synthesis. provides a simple graphic bringing meta-themes from the synthesis together to guide the work of measuring connectedness to nature in a Nordic context–and possibly beyond-given the potential transferability of these outcomes to other settings (Bloomberg and Volpe Citation2018).

The use of the phrase "engaged practitioners" in is meant to emphasize that C2N measurement efforts by researchers must be grounded in an acceptance by the practitioner of their role, whether as an evaluator of the teaching process, a facilitator of the research process, a full partner in a transdisciplinary research process, or a full researcher as in an action research process (Newton and Burgess Citation2008). Regardless, it should be emphasized that both the researcher and practitioner roles have essential information and skills to support the process (Morton, Eigenbrode, and Martin Citation2015; Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020). However, the idea of an "engaged practitioner" emphasizes that practitioners have critical information/skills, including child-specific awareness, site awareness, relationships with the school community, and other context-specific information to which an outside researcher may not have direct access. Such information can facilitate child comfort, process efficiency, and awareness of unique aspects of C2N conceptual awareness and, in doing so, strengthen the research and the research-practice partnership. Further use of the term "engaged" means that the practitioner sees themselves as a partner (or lead) in the process and that this role begins with the decision to measure C2N.

A critical consideration of audience stretches from the particularities of a given group to the broader awareness of cultural context, language use, and social norms. For example, many Nordic child groups in institutional settings have become increasingly diverse from a variety of vantage points, including, but not limited to, socioeconomic status, cultural heritage, and first language use (Kuusisto and Garvis Citation2020). Demographically, Nordic societies have become increasingly urban, which may also influence cultural understanding or identity assumptions. Thus, using the term “Nordic” must imply an awareness of the potential for a new Nordic diversity and social landscape (Furseth et al. Citation2018; Kuusisto and Garvis Citation2020; Haarstad et al. Citation2021). One key example of this critical awareness is conceptual understanding of how child participants understand nature and nature experience; a careful approach to normative assumptions regarding nature and nature experience is essential.

Innovative scale design means that C2N scales may need to have multiple ways in which they can be communicated (Massey Citation2022). For example, both visual image-based scale presentation and text-based scales, with awareness of language use, both from the standpoints of reading development and cultural awareness (e.g. the possibility for scales in multiple languages), should be considered to address concerns about children’s comprehension of scale items, as noted in the case studies. Along with using text or emoji-based response options, this study also considered other aspects of scale delivery, for example, using props such as puppets. Multiple scale delivery options must be available to facilitate the most efficient, comfortable, and conceptually appropriate scale application. These recommendations, coupled with previous scale use emphasizing the challenges of child comprehension of scale items (Rosa, Profice, and Collado Citation2018; Rosa, Collado, and Larson Citation2022a), are reminders for scale design to consider the participant group in the scale choice process closely.

One outcome of an increased understanding of C2N scale use based on the three case studies should be the ability to answer the question as to whether these three scales featured in this study are recommended for use. The answer is, perhaps! Given the awareness of the factors identified in this article (culminating in application recommendations for measuring connectedness to nature) and the use of the C2N scale use checklist (see ) in conjunction with the Practitioner Guide to Assessing Connection to Nature (Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020), good decisions can be made. When the C2N scale use checklist is used concurrently (iteratively) with the scale selection process presented in the Practitioner Guide (Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020), practitioners and researchers have significant support for making decisions and planning measurement strategies. The C2N checklist provides a starting point for decision-making (common goals and conceptual clarity). Moreover, the C2N checklist helps monitor the process, emphasizing child well-being and process integrity.

Table 5. C2N scale use checklist.

Creation of the checklist is a direct outcome of the case study synthesis; moreover, the checklist shows a strong alignment with findings from the previously noted early childhood scale review (Beery et al. Citation2020). Results from that study encouraged a mixed methods approach to measurement data collection, highlighting the value of multiple sources, such as teachers and parents in addition to children directly involved in the measurement process. The earlier review also encouraged a playful, game-like format to help engage children’s participation.

The process described in this section and culminating in the C2N scale use checklist raises the question of how flexible teams of researchers and practitioners can be in their quest to measure C2N while simultaneously generating data that can be used, shared, and compared. If other researchers or practitioners wish to use the results, they must accept the modifications as relevant and applicable to their setting, i.e. transferable. This balance between flexibility and a systematic approach underscores the dynamic aspect of transdisciplinary research, simultaneously meeting community and scientific needs. Given this concern, a vital aspect of the measurement process is a highly transparent approach regarding any possible adaptations to ensure conceptual clarity, child well-being, and program integration. For example, in the CNI case, the scale was modified by translation to Swedish, text was replaced with an emoji-based scale, several questions were eliminated, and data collection involved small groups of children supported by a researcher. Such transparency allows other researchers and practitioners to make informed decisions about transferability over time or in context (Bloomberg and Volpe Citation2018).

6. Conclusion

Measuring C2N and evaluating an environmental education program’s ability to promote the development of C2N is supported in the environmental education literature (Salazar et al. Citation2021); there is a need to provide tangible results indicating that environmental education programs are delivering regarding C2N outcomes on organizational and institutional levels. At the core of this need is a commitment to providing children with nature experience that supports affective, cognitive, and physical well-being and growth while supporting pro-environmental behavior development throughout life.

This study analyzed three cases united by time, geography, and intent to consider C2N scale use in environmental education programming. While the analysis and discussion of the three case studies are not generalizable, the cases provide adequate information to gauge transferability; the meta-themes and checklist for application may be useful in other Western environmental education contexts. Specifically, a combination of support using the Practitioner Guide to Assessing Connection to Nature (Salazar, Kunkle, and Monroe Citation2020) coupled with the C2N scale use checklist (see ) can help practitioners and researchers make informed decisions about scale use.

Authors’ contributions

Thomas Beery: Conceptualization; Planning; Methodology; Data collection; Analysis; Lead writing, review, and editing. Marie Fridberg: Conceptualization; Planning; Methodology; Data collection; Analysis; Writing, review, and editing. ̈Søren Præstholm: Conceptualization; Planning; Methodology; Data collection; Analysis; Writing, review, and editing. Tanya Uhnger Wünsche: Planning; Analysis; Writing, review, and editing. Mads Bølling: Planning; Methodology; Data collection; Analysis; Writing, review and editing.

Ethics statement

Ethical treatment of research participants and ethical data management have been observed. All necessary permissions were obtained in accordance with ethical guidelines for research.

| Abbreviations | ||

| BI | = | Biophilia Interview |

| C2N | = | Connectedness to nature |

| CNI | = | Connectedness with Nature Index |

| INS | = | Inclusion of Nature in Self Scale |

| SAEC | = | School-age educare |

| SCD | = | Save the Children Denmark |

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the educators and youth professionals that assisted the research teams at the various sites. Save the Children Denmark is acknowledged for the collaboration regarding the Danish Case. Thank you to LinaMaria Bengtsson for Biophilia Interviews assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alikari, Victoria, Evangelos C. Fradelos, Natalia Giannakopoulou, Georgia Gerogianni, Flora Efstathiou, Maria Lavdaniti, and Sofia Zyga. 2021. “Translation, Cultural Adaptation, Validation and Internal Consistency of the Factors of Nurses Caring Behavior. ”Materia Socio-Medica 33 (1): 34. https://doi.org/10.5455/msm.2021.33.34-40.

- Andersson, Birgit. 2013. “Nya fritidspedagoger-i spänningsfältet mellan tradition och nya styrformer.” PhD diss., Umeå universitet. https://www.divaportal.org/smash/get/diva2:603114/FULLTEXT02.pdf.

- Andkjær, Rikke, Søren Præstholm, and Søren Andkjær. 2022. “Jag tror inte att de någonsin sett en groda förut!”: Kvalitativ utvärdering av Rädda Barnens Naturklubbar och Familjeupplevelseklubbar. Frederiksberg: Centrum för barn och natur, IGN, KU, 29 sid.

- Barrable, Alexia. 2019. “The Case for Nature Connectedness as a Distinct Goal of Early Childhood Education.” International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education 6 (2): 59–70.

- Barragan‐Jason, Gladys, Claire de Mazancourt, Camille Parmesan, Michael C. Singer, and Michel Loreau. 2022. “Human–Nature Connectedness as a Pathway to Sustainability: A Global Meta‐Analysis.” Conservation Letters 15 (1): e12852. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12852.

- Barragan-Jason, Gladys, Michel Loreau, Claire de Mazancourt, Michael C. Singer, and Camille Parmesan. 2023. “Psychological and Physical Connections with Nature Improve Both Human Well-Being and Nature Conservation: A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses.” Biological Conservation 277: 109842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109842.

- Beery, Thomas H. 2013. “Establishing Reliability and Construct Validity for an Instrument to Measure Environmental Connectedness.” Environmental Education Research 19 (1): 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.687045.

- Beery, Thomas. 2014. “People in Nature: Relational Discourse for Outdoor Educators.” Research in Outdoor Education 12 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1353/roe.2014.0001.

- Beery, Thomas H., and Daniel Wolf-Watz. 2014. “Nature to Place: Rethinking the Environmental Connectedness Perspective.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 40: 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.06.006.

- Beery, Thomas H., and Kristi S. Lekies. 2021. “Nature’s Services and Contributions: The Relational Value of Childhood Nature Experience and the Importance of Reciprocity.” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9: 636944. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2021.636944.

- Beery, Thomas, Louise Chawla, and Peter Levin. 2020. “Being and Becoming in Nature: Defining and Measuring Connection to Nature in Young Children.” International Journal of Early Childhood Environmental Education 7 (3): 3–22.

- Beery, Thomas, Henric Djerf, Tanya Uhnger Wünsche, and Marie Fridberg. 2023. “Broadening the Foundation for the Study of Childhood Connectedness to Nature.” Frontiers in Environmental Science 11: 1225044. https://doi.org/10.3389/fen-vs.2023.1225044.

- Bloomberg, Linda, and Marie Dale. 2018. “Completing Your Qualitative Work: A Road Map from Beginning to End.” Volpe.

- Bølling, Mads, and Søren Præstholm. 2023. “At gennemføre spørgeskemaundersøgelser med børn.” Erfaringer fra fire evalueringer i krydsfeltet mellem børn, udsatte boligområder og naturbaserede aktiviteter.

- Boström, Lena, Helene Elvstrand, and Monica Orwehag. 2022. “Didactics in School-Age Educare Centres–An Unexplored Field but with Distinctive Views.” Social Sciences & Humanities Open 6 (1): 100333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssa-ho.2022.100333.

- Bragg, Rachel, Carly Wood, Jo Barton, and Jules Pretty. 2013. Measuring Connection to Nature in Children Aged 8-12: A Robust Methodology for the RSPB. Essex: University of Essex.

- Calander, Finn. 2001. “Fritidspedagogen: Lärare, barnavårdare eller fritidsledare?: En analys av utskick till medlemmarna i Sveriges Fritidspedagogers Förening 1969–1979.” https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:109744/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Carleton-Hug, Annelise, and J. William Hug. 2010. “Challenges and Opportunities for Evaluating Environmental Education Programs.” Evaluation and Program Planning 33 (2): 159–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2009.07.005.

- Chawla, Louise. 2020. “Childhood Nature Connection and Constructive Hope: A Review of Research on Connecting with Nature and Coping with Environmental Loss.” People and Nature 2 (3): 619–642. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10128.

- Cheng, Judith Chen-Hsuan, and Martha C. Monroe. 2012. “Connection to Nature: Children’s Affective Attitude toward Nature.” Environment and Behavior 44 (1): 31–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916510385082.

- Children & Nature Network. 2023. “About the Children & Nature Network.” https://www.childrenandnature.org/about/.

- Crowe, S., K. Cresswell, A. Robertson, G. Avery Huby, A. Avery, and Sheikh, A. 2011. “The Case Study Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11 (1): 100. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100.

- Davis, Jody L., Jeffrey D. Green, and Allison Reed. 2009. “Interdependence with the Environment: Commitment, Interconnectedness, and Environmental Behavior.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 29 (2): 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2008.11.001.

- Elvstrand, Helene, and Anna-Liisa Närvänen. 2016. “Children’s Own Perspectives on Participation in Leisure-Time Centers in Sweden.” American Journal of Educational Research 4 (6): 496–503. https://doi.org/10.12691/education-4-6-10.

- Furseth, Inger, Lars Ahlin, and Kimmo Ketola. 2018. “Annette Leis-Peters, and Bjarni Randver Sigurvinsson. “Changing Religious Landscapes in the Nordic Countries.” In Religious Complexity in the Public Sphere: Comparing Nordic Countries, edited by Inger Furseth, 31–80. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gaston, Kevin J., and Masashi Soga. 2020. “Extinction of Experience: The Need to Be More Specific.” People and Nature 2 (3): 575–581. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10118.

- Genc, Murat, Tulin Genc, and Pinar Goc Rasgele. 2018. “Effects of Nature-Based Environmental Education on the Attitudes of 7th Grade Students towards the Environment and Living Organisms and Affective Tendency.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 27 (4): 326–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2017.1382211.

- Haarstad, Håvard, Gro Sandkjær Hanssen, Bengt Andersen, Lisbet Harboe, Jørn Ljunggren, Per Gunnar Røe, Tarje Iversen Wanvik, and Marikken Wullf-Wathne. 2021. “Nordic Responses to Urban Challenges of the 21st Century.” Nordic Journal of Urban Studies 1 (1): 4–18. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2703-8866-2021-01-01.

- Haglund, Björn, and Lena Boström. 2022. “Everyday Practices in Swedish School-Age Educare Centres: A Reproduction of Subordination and Difficulty in Fulfilling Their Mission.” Early Child Development and Care 192 (2): 248–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2020.1755665.

- Halldén, Gunilla. 2007. “Barns plats och platser för barn.” Den moderna barndomen och barns vardagsliv: 81–96.

- Head, Brian W. 2016. “Toward More “Evidence‐Informed” Policy Making?” Public Administration Review 76 (3): 472–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12475.

- Holmberg, Linnéa, and Eva Kane. 2020. “Den tacksamma leken-Legitimering av fritidshemsverksamhet genom utbildningspolitik och forskning.” Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige 25 (2–3): 92–113. https://doi.org/10.15626/pfs25.0203.05.

- Ives, Christopher D., David J. Abson, Henrik Von Wehrden, Christian Dorninger, Kathleen Klaniecki, and Joern Fischer. 2018. “Reconnecting with Nature for Sustainability.” Sustainability Science 13 (5): 1389–1397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0542-9.

- Kane, Michael T. 2013. “Validating the Interpretations and Uses of Test Scores.” Journal of Educational Measurement 50 (1): 1–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12000.

- Klarare, Anna, Anna Wikman, Mona Söderlund, Jenny McGreevy, Elisabet Mattsson, and Andreas Rosenblad. 2021. “Translation, Cross‐Cultural Adaptation, and Psychometric Analysis of the Attitudes towards Homelessness Inventory for Use in Sweden.” Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 18 (1): 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12477.

- Kleespies, Matthias Winfried, Tina Braun, Paul Wilhelm Dierkes, and Volker Wenzel. 2021. “Measuring Connection to Nature—A Illustrated Extension of the Inclusion of Nature in Self Scale.” Sustainability 13 (4): 1761. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041761.

- Klerfelt, Anna, and Björn Haglund. 2014. “Presentation of Research on School-Age Educare in Sweden.” International Journal for Research on Extended Education 2 (1): 45–62. https://doi.org/10.3224/ijree.v2i1.19533.

- Kuusisto, Arniika, and Susanne Garvis. 2020. “Superdiversity and the Nordic Model in ECEC.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 21 (4): 279–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949120983619.

- Lager, Karin. 2015. “I spänningsfältet mellan kontroll och utveckling. En policystudie av systematiskt kvalitetsarbete i kommunen, förskolan och fritidshemmet.” https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/handle/2077/40661/gupea_2077_40661_2.pdf?sequence=2

- Lago, Lina, and Helene Elvstrand. 2019. “Där är vi inblandade allihop”: Samverkan mellan lärare i fritidshem, förskoleklass och grundskola.” Venue 8 (2). https://doi.org/10.3384/venue.2001-788X.19813.

- Lago, Lina, and Helene Elvstrand. 2022. “Children on the Borders between Institution, Home and Leisure: Space to Fend for Yourself When Leaving the School-Age Educare Centre.” Early Child Development and Care 192 (11): 1715–1727. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2021.1929200.

- Lim, Christopher, Andrew M. Donovan, Nevin J. Harper, and Patti-Jean Naylor. 2017. “Nature Elements and Fundamental Motor Skill Development Opportunities at Five Elementary School Districts in British Columbia.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14 (10): 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14101279.

- Louv, Richard. 2005. Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder. Algonquin Books.

- Martin, Stephen, Christopher D. Ives, and Barry Carney. 2023. “Universities as Agents of Change: Green Academy to Ecological University.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Sustainability in Higher Education, e, edited by Wendy M. Purcell, and Janet Haddock-Fraser. Bloomsbury: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Massey, Simon. 2022. “Using Emojis and Drawings in Surveys to Measure Children’s Attitudes to Mathematics.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 25 (6): 877–889. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2021.1940774.

- Mayer, F. Stephan, and Cynthia McPherson Frantz. 2004. “The Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Individuals’ Feeling in Community with Nature.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 24 (4): 503–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen-vp.2004.10.001.

- Mayer, F. Stephan, Cynthia McPherson Frantz, Emma Bruehlman-Senecal, and Kyffin Dolliver. 2009. “Why Is Nature Beneficial? The Role of Connectedness to Nature.” Environment and Behavior 41 (5): 607–643. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508319745.

- Morton, Lois., Wright, Sanford D. Eigenbrode, and Timothy A. Martin. 2015. “Architectures of Adaptive Integration in Large Collaborative Projects.” Ecology and Society 20 (4). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07788-200405.

- Mygind, Lærke, Eva Kjeldsted, Rikke Hartmeyer, Erik Mygind, Mads Bølling, and Peter Bentsen. 2019. “Mental, Physical and Social Health Benefits of Immersive Nature-Experience for Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Quality Assessment of the Evidence.” Health & Place 58: 102136. ’. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.05.014.

- Navarro, Oscar, Pablo Olivos, and Ghozlane Fleury-Bahi. 2017. ““Connectedness to Nature Scale”: Validity and Reliability in the French Context.” Frontiers in Psychology 8: 2180. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02180.

- Newton, Paul, and David Burgess. 2008. “Exploring Types of Educational Action Research: Implications for Research Validity.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 7 (4): 18–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690800700402.

- Nisbet, Elizabeth K., and John M. Zelenski. 2011. “Underestimating Nearby Nature: Affective Forecasting Errors Obscure the Happy Path to Sustainability.” Psychological Science 22 (9): 1101–1106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611418527.

- Præstholm, Søren. n.d. “Children & Nature - Denmark. Center for Børn og Natur.” https://centerforboernognatur.dk//children-and-nature-denmark/.

- Price, Eluned, Sarah Maguire, Catherine Firth, Ryan Lumber, Miles Richardson, and Richard Young. 2022. “Factors Associated with Nature Connectedness in School-Aged Children.” Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology 3: 100037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cresp.2022.100037.

- Pyle, Robert Michael. 1993. The Thunder Tree. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Restall, Brian, and Elisabeth Conrad. 2015. “A Literature Review of Connectedness to Nature and Its Potential for Environmental Management.” Journal of Environmental Management 159: 264–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.05.022.

- Rice, Camilla S., and Julia C. Torquati. 2013. “Assessing Connections between Young Children’s Affinity for Nature and Their Experiences in Natural Outdoor Settings in Preschools.” Children Youth and Environments 23 (2): 78–102. https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.23.2.0078.

- Richardson, M., and C. W. Butler. 2022. “The Nature Connection Handbook: A Guide for Increasing People’s Connection with Nature.” https://findingnatureblog.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/the-nature-connection-handbook.pdf

- Richardson, M., D. Sheffield, C. Harvey, and D. Petronzi. 2015. ”The Impact of Children’s Connection to Nature. A Report for the Royal Society of the Protection of Birds (RSPB).” www.derby.ac.uk/

- Richardson, Miles, Anne Hunt, Joe Hinds, Rachel Bragg, Dean Fido, Dominic Petronzi, Lea Barbett, Theodore Clitherow, and Matthew White. 2019. “A Measure of Nature Connectedness for Children and Adults: Validation, Performance, and Insights.” Sustainability 11 (12): 3250. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123250.

- Rosa, Claudio D., Christiana Cabicieri Profice, and Silvia Collado. 2018. “Nature Experiences and Adults’ Self-Reported Pro-Environmental Behaviors: The Role of Connectedness to Nature and Childhood Nature Experiences.” Frontiers in Psychology 9: 1055. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01055.

- Rosa, Claudio D., Eiko I. Fried, Lincoln R. Larson, and Silvia Collado. 2023. “Four Challenges for Measurement in Environmental Psychology, and How to Address Them.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 85: 1–3.

- Rosa, Claudio D., Silvia Collado, and Lincoln R. Larson. 2022. “The Utility and Limitations of the New Ecological Paradigm Scale for Children.” The Journal of Environmental Education 53 (2): 87–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.2022.2044281.

- Rosa, Claudio D., Silvia Collado, Christiana Cabicieri Profice, and Pedro P. Pires. 2022. “The 7-Items Version of the Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Study of Its Validity and Reliability with Brazilians.” Current Psychology 41 (8): 5105–5110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01026-2.

- Salazar, Gabby, Kristen Kunkle, and Martha C. Monroe. 2020. Practitioner Guide to Assessing Connection to Nature. Washington, DC: North American Association for Environmental Education. https://naaee.org/sites/default/files/2022-10/

- Salazar, Gabby, Martha C. Monroe, Catherine Jordan, Nicole M. Ardoin, and Thomas H. Beery. 2021. “Improving Assessments of Connection to Nature: A Participatory Approach.” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 8: 609104. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.609104.

- Schultz, P. Wesley. 2002. “Inclusion with Nature: The Psychology of Human-Nature Relations.” In Psychology of Sustainable Development, pp. 61–78. Boston, MA: Springer US, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0995-0_4.

- Skolverket. 2022. ”Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet 2011.” Revised 2019, Lgr11. Skolverket.

- Skytte, E. 2019. Ud i naturen − ind i fællesskabet. København: Akademisk Forlag

- Soga, Masashi, and Kevin J. Gaston. 2016. “Extinction of Experience: The Loss of Human–Nature Interactions.” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14 (2): 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.1225.

- Soga, Masashi, and Kevin J. Gaston. “Towards a Unified Understanding of Human–Nature Interactions.” Nature Sustainability 5, no. 5 (2021): 374–383. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00818-z.

- Denmark, Statistics. 2014. “Færre børn i daginstitutionerne efter skolereformen.” Nyt Fra Danmarks Statistik 162. https://www.dst.dk/Site/Dst/Udgivelser/nyt/GetPdf.aspx?cid=19245.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. 2018. Curriculum for the Preschool Lpfö 2018. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. 2022. Statistics for Preschool. Stockholm: Swedish National Agency for Education. www.skolverket.se

- Swedish Research Council. 2017. Good Research Practice. Stockholm: Swedish Research Council.

- Taber, Keith S. 2018. “The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education.” Research in Science Education 48 (6): 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2.

- Terwee, C. B., C. A. C. Prinsen, A. Chiarotto, M. J. Westerman, D. L. Patrick, J. Alonso, L. M. Bouter, H. C. W. de Vet, and L. B. Mokkink. 2018. “COSMIN Methodology for Evaluating the Content Validity of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: A Delphi Study.” Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation 27 (5): 1159–1170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0.

- Tsang, Siny, Colin F. Royse, and Abdullah Sulieman Terkawi. 2017. “Guidelines for Developing, Translating, and Validating a Questionnaire in Perioperative and Pain Medicine.” Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia 11 (Suppl 1): S80–S89. https://doi.org/10.4103/sja.SJA_203_17.

- Van Bork, Riet, Lisa D. Wijsen, and Mijke Rhemtulla. 2017. “Toward a Causal Interpretation of the Common Factor Model.” Disputatio 9 (47): 581–601. https://doi.org/10.1515/disp-2017-0019.

- Waite, Sue. 2020. “Teaching and Learning outside the Classroom: Personal Values, Alternative Pedagogies and Standards.” In Outdoor Learning Research, 8–25. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004270903206141.

- Wells, Nancy M., and Kristi S. Lekies. 2006. “Nature and the Life Course: Pathways from Childhood Nature Experiences to Adult Environmentalism.” Children, Youth and Environments 16 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1353/cye.2006.0031.

- Yin, Robert K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Vol. 5. Sage.