Abstract

Critical thinking as a concept, has a rich history and is central to much of the debate within international educational research and increasingly within environmental and sustainability education (ESE). Currently, it is gaining a foothold in the curriculum and in practice in Nordic countries. However, to date, there has been no proper account of what critical thinking entails in formal ESE settings in Nordic countries. In this article, we utilise a theoretically explorative approach to discuss the following research question: How can various conceptualisations of critical thinking be understood in relation to a selection of ESE positions and current challenges in the Nordic educational context? Through a theoretical exploration of critical thinking and action in relation to selected ESE positions, we find that although critical ESE positions favour critical thinking, which enables a strong degree of deliberate and detectable action, conceptualisations of critical thinking that promote cognitive skills are also important for critical ESE.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS:

Introduction

Our world is on fire (Thunberg Citation2019), and for the first time in history, humans have the ability to destroy life on Earth. The UN and UNESCO insist that climate change is here, and that states and educational systems need to react. Countries around the world have responded to this threat in different ways. In the Global North, Norway has also reacted. Kind of. Even though the Norwegian government keeps looking for and refining oil, in 2020, the terms ‘sustainable development’ and ‘critical thinking’ became central aspects of the national curriculum for primary and secondary schooling (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2020). In 2020, sustainable development was introduced as a cross-curricular topic that is to be addressed throughout all thirteen years of primary and secondary education. The reform also highlighted the concept of critical thinking as an explicit part of the national competence definition, which is to serve as the foundation for teaching, learning and assessment in all subjects. In the curriculum, there are minimal guidelines on how ‘critical thinking’ is to be understood in relation to ‘sustainable development’. Hence, analyses of the curriculum show that it comes down to the individual teacher as to how these terms are to be accessed in formal educational settings (Jegstad and Ryen Citation2020; Ott Citation2019; Scheie et al. Citation2022).

‘Critical thinking’ has been a mainstay of diverse national and international educational spheres. The concept is often linked with notions of how to deal with ethical issues in education and support continued democratic development (Facione Citation2020; Paul and Elder Citation2009). This has very much been the case in the Nordic countries and in discussions in the field of environmental and sustainability education (ESE) (e.g. Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010; Öhman and Östman Citation2008; Van Poeck, Östman, and Öhman Citation2019). In the wider ESE context, critical thinking appears in relation to both the Nordic ESE tradition and the Anglo-Saxon ‘critical’ ESE tradition (Gough and Scott Citation2003; Jickling Citation1992). A key recurring idea behind the use of the concept is that learners with critical minds will no longer passively accept truth claims from authorities, thus becoming active influencers in shaping their own possible futures (Rieckmann Citation2018; UNESCO Citation2016). To transform the predicted outcomes of the climate crisis, whereby global warming will affect millions of people (Guterres Citation2021), there is a need to think anew so that students will actively contribute to solutions (Jónsson et al. Citation2021; Van Poeck Citation2019). Furthermore, there is a need to address whether thinking about this is enough or if action is also required within formal educational settings (Lysgaard and Bengtsson Citation2022). Although such positions frame critical thinking as a central component for dealing with environmental problems and challenges, there is no accepted formalised conceptualisation of ‘critical thinking’ as a concept in formal ESE settings in Nordic schools (Jónsson et al. Citation2021).

This paper aims to provide a view of the conceptualisations of four theoretical lines of thought regarding critical thinking and explore their strengths and limitations in relation to selected positions of critical ESE that are a part of the Nordic dialogue on formal education and that are increasingly under discussion in Nordic research (Carlsson & Lysgaard, forthcoming). These are the pluralistic teaching approach (e.g. Öhman and Östman Citation2019; Tryggvason, Öhman, and Van Poeck Citation2023), wild pedagogies (Blenkinsop, Morse, and Jickling Citation2022; The Crex Crex Collective, Citation2018), dark pedagogy (Lysgaard, Bengtsson, and Laugesen Citation2019) and pyropedagogies (Reid Citation2019). In our view, these positions offer a diversity of scholarly thinking that supports a critical take, where they all share the need for change as a driving force. Their approach to ESE varies; hence, the role of critical thinking differs. Taken together, they illustrate possible ideals for current and future ESE, and they highlight various aspects that can be discussed in relation to critical thinking.

Critical thinking has its origins in ancient philosophy (Watson Citation2024), and it has evolved into distinct strands over time (Popkewitz Citation1999). In this paper, we elaborate on conceptualisations that were extensively developed during the 20th and 21st centuries, drawing on Burbules and Berk’s (Citation1999) exploration of critical thinking, which delineates four main conceptualisations: 1) Critical thinking as a logic-analytical concept, as theorised by philosophers in the critical thinking (CT)-movement, 2) critical pedagogy, 3) criticality and 4) critical openness. Our exploration is centred on the intersection of critical thinking and action, which is particularly relevant to critical ESE. This intersection is not only pivotal to ESE but is also a topic of debate among scholars of critical thinking (Burbules and Berk Citation1999; Davies Citation2015; Shpeizer Citation2018). The research question guiding our exploration is as follows:

How can various conceptualisations of critical thinking be understood in relation to a selection of ESE positions and current challenges in the Nordic educational context?

Methodology

Theoretical exploration is essential for clarifying implicit assumptions within complex practices, such as education, by illuminating tacit knowledge, values and diverse interpretations of multifaceted concepts such as critical thinking. In ESE, theoretical explorations might aid in creating tools to connect past and future ESE and guide the field towards a better future (Reunamo and Pipere Citation2011). Burbules and Warnick (Citation2006) outline ten philosophical inquiry methods, with this study focusing on the first two: concept analysis for clarification and an ideological critique to expose a term’s ambiguities and biases. Utilising a theoretically explorative approach commonly employed to deepen insights and guide future research, this approach also serves to refine and elucidate concepts.

It is difficult to map out a concept comprehensively; therefore, we have made several choices relating to what to include and to focus on in our exploration. We elaborate on the conceptualisations in the next section. Here, we will briefly mention the conceptualisations we have chosen and why. Two of the conceptualisations of critical thinking, the logic-analytical concept and critical pedagogy, have long traditions and have influenced critical thinking in education for decades. The other two conceptualisations, criticality and critical openness, are newer, and therefore less established, which represent evolutions of the more traditional conceptualisations (Burbules and Berk Citation1999). Criticality, in particular, is gaining traction in ESE discussions in the Nordic region. In this paper, we lean towards the more philosophical notions of the concepts, as opposed to the more political aspects, since these have arguably had the greatest impact on educational research to date (Carlsson & Lysgaard, forthcoming). There are also other conceptualisations we could have explored more thoroughly, such as different branches of post-humanism, which have yet to be directly linked to the existing traditions on critical thinking in ESE, especially in the Nordic countries (Ceder, Citation2018; Taylor & Bayley, Citation2019). Consequently, these have not been the focus of this paper.

For this paper, we have also selected four ESE positions pertinent to Nordic educational discussions, such as the pluralistic approach and those increasingly impacting Nordic ESE perspectives theoretically. Although alternative positions merit attention, for example, community-based and transformative environmental education, ecofeminism, deep ecology, ecojustice and climate change education (e.g. Iverson Citation2015; Kopnina Citation2014; Martusewicz, Edmundson, and Lupinacci Citation2021; Ruiz-Mallén et al. Citation2022; Van Poeck, Lysgaard, and Reid Citation2018), a comprehensive exploration of these positions is beyond the scope of this paper.

In delving into critical thinking, we embrace critical openness, a conceptualisation that we will detail later in our paper. However, to introduce our position, we provide a brief outline here. Critical openness allows for a probing exploration and comprehension of ideas, unencumbered by the constraints of entrenched scholarly positions. It downplays the significance of incommensurability, instead inviting engagement with the tensions between differing conceptualisations and traditions. This approach emphasises the importance of rethinking established ideas with a renewed perspective (Burbules and Berk Citation1999).

In this paper, definitive answers are neither possible nor sought. What we have sought to do is map out a conceptualisation of critical thinking from different lines of theory and view it in relation to ESE positions. We do this to make the various positions visible and to develop and reimagine concepts with the hope of inspiring and enriching researchers’ and practitioners’ use of critical thinking.

Four conceptualisations of critical thinking

In this section we will elaborate on the following four conceptualisations of critical thinking: The logic-analytical line, critical pedagogy, criticality and critical openness.

The first conceptualisation of critical thinking that we will elaborate on is the logic-analytical conceptualisation related to the CT-movement that arose in the United States in the latter part of the 1900s.Footnote1 The CT-movement is a philosophical movement that works towards a broad educational ideal that uses informal logic in argumentation as its tool to help people make reasoned and logical choices (Shpeizer Citation2018; Watson Citation2024). The term ‘critical thinking’ is closely related to this line (Burbules and Berk Citation1999). Drawing from John Dewey’s concept of ‘reflective thinking’, critical thinking is portrayed as a form of active and conscious thinking that involves evaluating beliefs based on reasons and judgements, aiming for knowledge through justification (Dewey Citation1910). Within the CT-movement, several definitions of critical thinking have emergedFootnote2, but as Robert Ennis (Citation2018) points out, ‘Each is a different way of cutting the same conceptual pie’ (p. 166). Others might argue differently, since Ennis (Citation1985) is the one who holds the most cited definition of critical thinking as ‘reflective and reasonable thinking that is focused on deciding what to believe or do’ (p. 45). It is argued that this definition lacks specificity in educational contexts (Kuhn Citation2019). A more detailed definition emerged from the consensus-driven Delphi report from the American Philosophical Association, which briefly defined critical thinking as ‘purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation and inference’ (Facione Citation1990, p. 3). The Delphi report further highlights that critical thinking is a logic-analytical process aimed at generating knowledge through a set of cognitive skills – including interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation and self-regulation – and dispositions, such as trust, self-confidence, open-mindedness, willingness, inquisitiveness, clarity, orderliness, diligence, precision and persistence. As a part of critical thinking skills and dispositions, observing, questioning, investigating and finding evidence are also encouraged (Ennis Citation2018; Facione Citation1990, Citation2020). Initially centred on mental processes, the CT-movement evolved to embrace a ‘critical spirit’ that merges emotional and rational elements (Bailin et al. Citation1999; Siegel Citation2010), positioning critical thinking as a vehicle for personal development, autonomy and democratic values, with a traditional focus on an individual dimension (Shpeizer Citation2018).

The CT-movement predominantly frames critical thinking in terms of cognition, not action, emphasising the mental processes involved in reasoning and decision-making. Ennis (Citation1985) does indeed hint at the idea of action, stating that critical thinking involves ‘reasonable and reflective thinking about what to believe or do’ (p. 45). Nonetheless, this statement allows room for different interpretations in the context of action. One perspective is that the action implied in Ennis’s definition could simply refer to the contemplation of possible actions and not necessarily to the execution of those actions (Davies Citation2015). Alternatively, it could suggest that making a decision to act seamlessly translates into the action itself, implying an assumption that ‘deciding’ unproblematically leads to the ‘doing’ (Burbules and Berk Citation1999). ESE research supports this complexity, indicating that knowledge does not automatically equate to observable action (Marcinkowski and Reid Citation2019; Vare and Scott Citation2007). Thus, according to these interpretations, actions remain somewhat on the periphery of critical thinking outlined by these influential definitions from the CT-movement, which focus more on judgement than on the actions that may or may not follow.

Critical pedagogy offers a second conceptualisation of critical thinking that diverges from the logic-analytical focus of the CT-movement, grounding itself in Marxist theory and the Frankfurt School’s critique of power structures and societal norms (Popkewitz Citation1999). Pioneers, such as Paulo Freire (Citation1998), view critical thinking as a vehicle for social transformation, advocating for the use of critical curiosity to question and disrupt the status quo, fostering a deeper comprehension of social issues and empowering individuals to proactively shape a more equitable and just world, which requires action. Critical pedagogy asserts that to be truly autonomous and informed, individuals must comprehend how power dynamics have shaped, and continue to shape, society, nature and the individual across time. This involves learning about societal organisation and functioning at the local, national and international levels, as well as cultivating the capacity to critically analyse individual actions and the operation of social structures (Burbules and Berk Citation1999). Critical pedagogues, such as Papastephanou and Angeli (Citation2007) and Lim (Citation2015), critique the CT-movement’s overemphasis on formal logic and argumentation for not sufficiently addressing the interconnectedness of social beings and the opaque ways in which social relations are constructed. For critical pedagogues, individual emancipation is intertwined with social emancipation; thus, the validity of arguments is inseparable from the social contexts in which they arise (Burbules and Berk Citation1999). Through the lens of critical pedagogy, critical thinking is compelled to transcend cognitive processes. It involves relationality and action, reflecting the belief that thought and action are mutually reinforcing. Within this paradigm, one cannot exist without the other – thinking informs action, and action informs thinking (Burbules and Berk Citation1999). Consequently, critical pedagogy embeds a social dimension within the concept of critical thinking, underscoring the importance of applying critical thought to enact social change.

The third conceptualisation of critical thinking, criticality, bridges perspectives from the logic-analytical line of reasoning and critical pedagogy, allowing for the exploration of their respective interests (Davies Citation2015). Ron Barnett (Citation1997), a key proponent of criticality, acknowledges the value of the cognitive dimension emphasised by the CT-movement but contends that on its own, it is insufficient. He posits that genuine critical thinking emerges at the intersection of three components: critical reasoning (related to knowledge), critical self-reflection (related to the self) and critical action (related to the world), collectively nurturing the formation of a critical being (Barnett Citation1997). Criticality recognises the individual as a starting point but emphasises the importance of engaging with the world. Social elements are integral to critical thinking within criticality and involve the examination of collective knowledge and values related to power across various contexts. Barnett (Citation1997) also accentuates the ethical and moral aspects of critical thinking, focusing on the action and agency of the critical thinker. Therefore, Barnett (Citation1997) differentiates between levels of criticality, with lower levels associated with the skill-centric views of the CT-movement and higher levels concerning the transformation of knowledge and the foundations upon which it rests, aligning more with critical pedagogy. Proponents of criticality advocate for a balance that avoids both the narrow focus on argumentation and the potentially extreme political positions associated with critical pedagogy (Barnett Citation1997; Davies Citation2015). In educational contexts, the application of criticality is contingent on the particular setting and objectives of each lesson in the context of formal education (Davies Citation2015). Furthermore, dialogue is a fundamental component of criticality, as it facilitates access to the collective mindset and provides an opportunity to engage with all levels of criticality, thus fostering a comprehensive and communicative approach to critical thought and action (Barnett Citation1997). The lack of action in the CT-movement served as a launch pad for Barnett’s (Citation1997) conceptualisation of criticality (Davies Citation2015). Within criticality, critical thinking is impossible without action (Barnett Citation1997). Barnett (Citation1997) emphasises that reflections alone are insufficient; they must be contextualised within broader social structures, policies and public interests, prompting students to envision alternative frameworks, systems and possibilities for collective action – however, the focus of critical thinking remains as a means to encourage personal responses to events (Davies Citation2015).

The fourth conceptualisation of critical thinking, called critical openness, was introduced by Burbules and Berk (Citation1999) and has been discussed and refined by Davies (Citation2015). This conceptualisation suggests moving beyond the established boundaries of the logic-analytical concept and critical pedagogy to foster the capacity to think outside of an issue’s original context, thereby embracing deeply challenging alternatives. This involves shedding preconceived fundamentals and transcending cultural logic, essentially promoting thinking outside the box. Critical openness encourages reflection on the limitations of the other conceptualisations of critical thinking, not by critiquing their ontological or epistemological bases, but instead by recognising the constraints that any ideology imposes on our understanding (Davies Citation2015). Openness is a necessity, thus making sure the concept is ever-evolving and always adapting. With critical openness, action is connected to critical thinking as practice, preferably in dialogue with others, where thinking in new ways arises from the interaction with challenging alternative views (Burbules and Berk Citation1999).

Critical thinking as action in relation to critical environmental and sustainability education

Action, as it relates to critical thinking, is more than the routine tasks that people perform subconsciously every day. For an action to be aligned with critical thinking, it must involve reflexivity and consciousness (Dewey Citation1910). Based on the premise that action is deliberate (Lysgaard and Bengtsson Citation2022), Jensen and Schnack (Citation1997) categorise environmental actions into direct action, where actions contribute to solving specific environmental problems, and indirect action, aimed at persuading others to address such issues. The context of this paper, which considers the curriculum changes in Norwegian formal education, suggests different modalities of action where critical thinking can be applied in ESE settings. These modalities are inspired by Arnstein’s ‘Ladder of Citizen Participation’ (1969), which outlines three degrees of participation: non-participation, tokenism and citizen power, here translated as student power.

In a formal educational setting, we can imagine ‘non-participation’ as an expert knowledge-driven form of education where non-experts are guided and/or indoctrinated by experts. This could manifest as a teacher taking full control of the class and giving authoritative lectures on sustainability issues. In light of critical thinking, true critical thinking will not be inherent; however, the teacher can work with parts of critical thinking, such as systematic learning of skills. In ESE, the non-participatory level aligns with earlier notions of ESE, often referred to as education for sustainable development 1 (ESD 1) (Vare and Scott Citation2007). Although critical thinking is not promoted at this level, students may still engage in critical thinking unintentionally, as they react to the presented content, thus maintaining their critical curiosity. According to Freire (Citation1998), keeping critical curiosity alive is crucial for social change, and for that to occur, it is important to ‘be immersed in existing knowledge as it is to be open and capable of producing something that does not yet exist’ (p. 35).

The middle level on Arnstein’s Ladder, tokenism, aligns with ESD 2 perspectives, which focus on open-ended and social learning processes with an emphasis on critically assessing expert statements and moving beyond them (Vare and Scott Citation2007). Here, we can imagine the teacher giving the students multiple possibilities to express their opinions and understandings in social and relational contexts. At this tokenism stage, while conversations are encouraged and may be rich in content, they do not necessarily translate into tangible change regarding the issues being discussed. Nevertheless, in Nordic educational settings, classroom dialogues are a common pedagogical tool (Hodgson, Rønning, and Tomlinson Citation2012; Lieberkind Citation2015) that aligns with curriculum values, such as democracy and participation (Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training Citation2020). In these dialogues, action manifests through the use of language (Searle Citation1969), the acquisition of knowledge (Rudsberg and Öhman Citation2015) and the very process of engaging in dialogue (Burbules Citation1993).

In this context, dialogues are understood as existing on two levels that are often intertwined: indirect dialogic thought and direct dialogue between people (Burbules and Berk Citation1999). The first level, indirect dialogic thought, is most closely linked to the cognitive domain of thinking, in which thinking happens inside a person’s mind. However, the thinking is in dialogue with thoughts that have already been uttered by someone else – either orally or in different kinds of texts from different times – by looking at a topic from different angles. Mikhail Bakhtin (Citation1986) phrases this as follows: ‘Each utterance is filled with echoes and reverberations of other utterances to which it is related by the communality of the sphere of speech communication’ (p. 91). From this perspective, no thought is purely cognitive or individualistic, since all that we think is related to others and others’ thoughts. Humans are always part of an ongoing dialogue (Bakhtin Citation1986). These ideas are also emphasised by Lim (Citation2015), a critical pedagogue who argues for a relational understanding of critical thinking, where ‘relational’ means that other people in different places at different times in history need to be considered when exploring a topic. The second level, engaging in conversation, is a central dimension of being critical (Burbules and Berk Citation1999), since it helps us see the strengths and limitations of our own understandings. Through conversational dialogues, the thoughts and words of others that have been encountered through the indirect dialogic approach become one’s own when they are rephrased and contextualised in relation to others (Bakhtin Citation1986). Wals (Citation2011) argues that dialogic approaches are important for ESE, since people learn from each other, and specifically from people who think differently – if our minds are open to it. Drawing on various perspectives addressed by different people in diverse contexts can offer promise in finding creative solutions to complex problems (Jickling Citation2013; Lim Citation2015).

According to Arnstein (Citation1969), the middle level of the Ladder might easily lead to apathy, since it is all about talk with no detectable action. However, language has the ability to change and reorganise peoples’ thoughts (Cobb Citation2007); hence, it leads the way towards reorganising understandings of culture, which is crucial for envisioning and creating possible sustainable futures, as there is not merely one possible future, but many (Lysgaard and Jørgensen Citation2020; Vare and Scott Citation2007). Therefore, dialogue has been framed as a central process towards educating critical thinkers (Barnett Citation1997; Burbules and Berk Citation1999; Freire Citation1998), but also much debated in relationship to how such dialogue should and could be framed, substantiated and continued in order to add to critical thinking and not merely entrench existing views (Lysgaard, Citation2018, Long & Henderson, Citation2024).

The final level of the Ladder is student power. In an educational setting, that level might be translated into a high degree of student participation and agency – where action and change go hand in hand. Here, action is more detectable, as it happens through the body and not only in the mind. In school, students might work on making sustainable choices, such as sorting trash and mending their own clothes. Or the students can make an active choice to stand on the barricades and fight for political change, as Greta Thunberg has done. However, Thunberg’s actions have not taken place in a formal school setting; hence, this is not possible within the current educational system (Ferrer et al. Citation2021). Regardless, this level of the Ladder aligns with critical ESE, where thinking and action are integrated, emphasising the importance of engaging with real-world challenges (Mogensen and Schnack Citation2010). Another way of engaging with the real world, as juxtaposed to Thunberg’s revolt, is to take on a very moderate form of action, while at the same time maintaining power over one’s participation – which is referred to as ‘actively doing nothing’ (Paulsen Citation2021, p. 227). By this, Paulsen (Citation2021) means that students should spend time together with other humans and more-than-humans to create ‘blooming and fertile relations’ (s. 227).

Although the active practices mentioned in this section can contribute to students’ critical action, they can also have uncritical motivations and outcomes. This is addressed by Hart (Citation2008), in his critique of his own interpretation of the ‘Ladder of Participation’. In the article “Stepping back from ‘The ladder’: Reflections on a model of participatory work with children”, Hart (2008) suggests that ‘the ladder’ as a metaphor has outplayed its role in defining participation, since participation is better understood by a metaphor of branches, giving children multiple ways to climb into meaningful encounters. In an ESE context, Tryggvason, Öhman, and Van Poeck (Citation2023) caution that activities promoting politically neutral actions, such as recycling and mending clothes, can end up reproducing depoliticised understandings of sustainability where marginalised voices are kept silent. They contend that empowering actions must incorporate post-colonial perspectives and address power dynamics (Tryggvason, Öhman, and Van Poeck Citation2023). Based on this discussion, we argue that all forms of action need to be complemented with dialogue and conversation that are reflective and critical. As Freire (Citation1998) says, ‘Critical reflection on practice is a requirement of the relationship between theory and practice. Otherwise theory becomes simply “blah, blah, blah,” and practice, pure activism’ (p. 30). Based on Freire’s perspective, we propose that all conceptualisations of critical thinking, both narrow and broad, bring valuable perspectives to critical ESE.

Conceptualisations of critical thinking in the four positions of environmental and sustainability education

The way researchers and practitioners understand the world we live in affects ESE politically, ethically, practically and pedagogically (Paulsen, Jagodzinski, and Hawke Citation2022). To cope with the climate crisis and a changing world, ESE researchers have introduced different positions as a response to answer the current challenges in education, such as the pluralistic teaching approach (e.g. Öhman and Östman Citation2019; Tryggvason, Öhman, and Van Poeck Citation2023), wild pedagogies (e.g. Blenkinsop, Morse, and Jickling Citation2022; Jickling Citation2018; The Crex Crex Collective, Citation2018), dark pedagogy (Lysgaard, Bengtsson, and Laugesen Citation2019) and pyropedagogies (Reid Citation2019). Our interpretations of the ESE positions are mainly based on the research referenced above; however, there are probably many more takes on the different positions than we elaborate on here. Regardless, we see these as sufficient to get a picture of the positions in terms of the critical thinking conceptualisations.

The first position is the pluralistic teaching approach. The pluralistic approach is one of three teaching traditions that has been identified through empirical research on ESE in Sweden, where the other two traditions are fact-based and normative traditions (Öhman and Östman Citation2019). Fact-based and normative traditions are embedded in the pluralistic approach, where perspectives on sustainability issues are explored through participatory processes and where students are to use their knowledge in action (Sund, Gericke, and Bladh Citation2020; Tryggvason, Öhman, and Van Poeck Citation2023). The pluralistic approach is both political and ethical (Van Poeck, Östman, and Öhman Citation2019), democratic and emancipatory (Sund and Gericke Citation2021). Here, the solutions for future challenges are open (Sund and Gericke Citation2021) and should not be understood as a plurality of ‘already fixed political positions and identities’ (Tryggvason, Öhman, and Van Poeck Citation2023, p. 12). The aim is for students to shape their perspectives and subjectivity in relation to themselves and others (Tryggvason, Öhman, and Van Poeck Citation2023). This is in line with the dialogic perspectives we referred to earlier. In this tradition, values are also important, since values clarify a variety of different interests and perspectives (Sund and Gericke Citation2021). In terms of critical thinking, we place the pluralistic approach within the dimension of criticality. Here, aspects of the CT-movement, such as skills and dispositions, are important for evaluating arguments and looking for reasons and justifications within a plurality of perspectives. The pluralistic approach also emphasises aspects of critical pedagogy, such as social relations and emancipation. In this tradition, dialogues as philosophy and pedagogy are at the core of thinking and action.

The second position that we will explore is the emerging construct of wild pedagogies. Wild pedagogies arose as a response to the current educational system in Canada, but also involve other Western countries where education is strongly under the influence of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, which their proponents claim is infused with cultural control that limits how it is possible to think, act and live in uncertain times (Jickling, Blenkinsop, Timmerman, and Sitka-Sage Citation2018). They further hold that education should be a partner in making change in the world (Blenkinsop, Morse, and Jickling Citation2022; Paulsen, Jagodzinski, and Hawke Citation2022) by engaging in imaginative, creative, courageous and radical responses, which means working less with routine and universal ideas (Blenkinsop, Morse, and Jickling Citation2022). Wild pedagogies urge teachers to break free from the control in the educational system, to become wilder, to engage in less mainstream education, as mentioned above, in relation to the first and middle levels of the Ladder of Citizen Participation, and to instead engage in more outdoor education (Paulsen, Jagodzinski, and Hawke Citation2022). The aim of wild pedagogies is ‘to renegotiate what it means to be human in relationship with the world by engaging in deep and transformational change using educational practices’ (Paulsen, Jagodzinski, and Hawke Citation2022, p. 17), where individualisation, alienation and instrumental control are not a part of education (Blenkinsop, Morse, and Jickling Citation2022). The change they are aiming for requires being in the world – dwelling there and listening to the marginalised voices of the more-than-human-world (Jickling Citation2018), to find and penetrate the edges of our cultural understandings and collective limits, imagine and re-examine different alternatives, critique and challenge dominant assumptions and worldviews, create visions for change and build community outcomes (Blenkinsop, Morse, and Jickling Citation2022; The Crex Crex Collective, Citation2018). When considering critical thinking, we place wild pedagogies within the line of critical openness. Here, the critical being who dares to move beyond current cultural logic and be creative in finding new solutions is emphasised.

The third ESE position, dark pedagogy, aims to respond to alarming changes on Earth with a new navigation tool that is fundamentally different from the ones that are in use today. Founded in a Bildung and Didaktik tradition, with a focus on character formation and spiritual development, dark pedagogy is ‘for an age of mass extinction’ (Lysgaard, Bengtsson, and Laugesen Citation2019, p. 2). Dark pedagogy considers the dark side of reality (Lysgaard, Bengtsson, and Laugesen Citation2019; Paulsen, Jagodzinski, and Hawke Citation2022), which is an unpleasant consequence of our current living conditions. The ‘dark’ informs us of aspects that lie beyond human control and comprehension; however, it can also inform us of the potential of something new that is not yet known (Lysgaard, Bengtsson, and Laugesen Citation2019). In that sense, dark pedagogy is not a gloomy, doomsday way of engaging with education, but an orientation that acknowledges the climate emergency and, at the same time, aims to help people remain sane and curious about possible futures. According to Lysgaard, Bengtsson, and Laugesen (Citation2019), dark pedagogy aims to ‘give the students the best possible points of departure to acknowledge and change the status quo for human societies’ (p. 3). Another goal is for students to become their own persons and belong to a more-than-human collective. As with wild pedagogies, dark pedagogy criticises the current educational system regarding its control or imitation of control:

The surreal and dangerous fantasy of being able to totally master educational content or reducing the objects of education to fully comprehensible phenomena for rationally trained human pupils, students or researchers is no longer sustainable. Didactical ideals ought to be recast with a renewed respect for and acknowledgement of the initially horrific ontological truth of the infinite depth of educational objects that lurk in the darker dens of reality (Lysgaard, Bengtsson, and Laugesen Citation2019, p. 16).

Finally, we will elaborate on pyropedagogies, which is a part of a Nordic ESE dialogue, specifically through a PhD course and concurrent seminars at the University of Oslo (UiO Citation2021). The term ‘pyropedagogies’ is inspired by Greta Thunberg’s speech at the World Economic Forum Annual Meeting in Davos in 2019, where she stated, ‘I want you to act as if you would in a crisis. I want you to act as if the house was on fire. Because it is’ (Thunberg cited in Reid Citation2019, p. 771). Pyropedagogies are related to climate emergency education, where the call is for action, not mere talk, as is often seen in today’s politics. To increase concrete action, pyropedagogies call on educators to fight for the world we want to live in through relational, translational and mediational values (Reid Citation2019). Different perspectives and scopes in education are important in pyropedagogies, since different positions create different opportunities for learning. These positions will be influenced by educators’ take on climate change. Pyropedagogies should also foster sustainability, equity and authenticity through freedom from oppression caused by climate injustices (Reid Citation2019). In terms of critical thinking, pyropedagogies have a strong foothold in action. As with wild pedagogies, pyropedagogies call on educators to act. However, where wild pedagogies aim for re-wilding and dwelling in the more-than-human-world, pyropedagogies want to fight. Not as in a medieval form of fighting with swords and fists, but with knowledge of multiple perspectives and fertile relations, as at the highest level on the Ladder of Citizen Participation. The action has a direction, and that is sustainability, equity, authenticity and freedom from oppression – values that are inherent in critical pedagogy. In this manner, we place pyropedagogies within critical pedagogy; however, the position also touches upon critical openness.

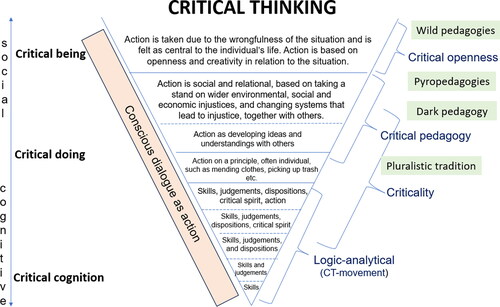

Drawing on this short and somewhat cursory analysis, we next place the ESE positions within a model of critical thinking in environmental and sustainability education (see ).

A model of critical thinking in environmental and sustainability education

The model of critical thinking in environmental and sustainability education, represented in , is inspired by the framework developed by Davies (Citation2015) for critical thinking in higher education. This model adapts Davis’s classifications to illustrate how critical thinking within ESE may be comprehended, particularly in terms of the correlation between thinking and action.

The model depicting critical thinking in ESE shows the relationship between the four conceptualisations of critical thinking we elaborated on previously: logic-analytical, criticality, critical pedagogy and critical openness conceptualisations. These conceptualisations are arranged in a reverse pyramid, with the logic-analytical concept representing the narrowest conceptualisation of critical thinking, and critical openness representing the broadest. Each conceptualisation offers a unique perspective on the action element within critical thinking, where the brackets point to which aspects are inherent in the various conceptualisations. Inside the reversed pyramid, the component of action is described. Running diagonally lengthwise is ‘conscious dialogue as action’. This amplifies dialogue as a form of action. Dialogue is therefore applicable across all conceptualisations, embracing both indirect and direct forms, as elaborated on earlier. To the left of the reversed pyramid is an arrow that points to two different focal points of critical thinking, with a bidirectional arrow suggesting two continuums. First, it points to a spectrum from inner cognitive processes associated with the individual to outer social aspects. Second, the continuum transitions from critical cognition to critical being, with critical doing situated in the middle. The term ‘critical cognition’ is employed instead of ‘critical thinking’ to distinguish between the narrow CT-movement conceptualisation and the broader notions that include critical doing and critical being. This distinction is made to clarify that ‘critical thinking’ serves as the umbrella term encompassing critical cognition, critical doing and critical being.

The ESE positions were placed in the model based on the analysis in the previous section of the paper. The model shows the differences between the pluralistic teaching approach and the ESE pedagogies. In this model, the ESE pedagogies are mainly connected to the outer aspects of critical thinking and not to the inner aspects that are inherent in the CT-movement, while the pluralistic approach finds itself somewhere in the middle as criticality. Based on the placement of the ESE positions, critical thinking as cognition might not be a desirable goal in ESE – perhaps critical doing or critical being would be more accurate.

In ESE, critical thinking is not to be seen as an isolated activity but as something intertwined with action. Hence, critical cognition and critical doing are important. Although the inner aspects of critical thinking as cognition are not emphasised in the ESE positions, they are important for the development of the self, which is specifically emphasised in dark pedagogy. Additionally, the self, which implies cognitive aspects, must be a factor in relation to the more-than-human-world and actions regarding fighting or rebellion, which is asked for by wild pedagogies and pyropedagogies.

In ESE, the different conceptualisations of critical thinking can therefore serve various and equally important educational aims. We argue that there is a need to use different conceptualisations of critical thinking in ESE, varying from broad to narrow. The various positions in critical thinking are different, although complementary, or at least they can be. In an environmental and sustainability setting, thinking alone will not develop or sustain the planet, since both aspects require some kind of action. However, mere thinking will make actions more informed. For critical ESE to have an impact on changing the status quo of the planet, action is required. However, not all situations, places and times during a school week can be action-oriented. Some need to involve mere thinking, talking and exploring cognitively. Therefore, we argue that different conceptualisations of critical thinking are right for different purposes and that one should not rule out the others. To critically examine and transform the status quo, multiple possibilities in education are needed to open up educational practices. The tensions between the conceptualisations can be used to further develop critical ESE and how critical thinking is understood and used.

The model is not intended to be seen as a developmental progression, where beginning with skills and culminating with openness represent a linear path towards learning critical thinking. Rather, the model is designed to illustrate a spectrum of perspectives on critical thinking, thus offering a tool that can aid researchers in empirically discerning ESE positions and transforming them into a reflection tool for practitioners. Acknowledging the model’s limitations, it is important to note that our ambition is not to encompass all facets of critical thinking. For instance, the model does not highlight emotional, affective or, for example, post-colonial or feminist perspectives as parts of critical thinking. Constructs from wild and dark pedagogies, which place a significant emphasis on the more-than-human-world, are also left out. The model’s focus has been deliberately chosen to highlight links between critical thinking and action within formal education in Nordic countries.

Challenges ahead

Although researchers strongly agree that critical thinking is important in ESE, there are several challenges in our society and educational systems that can make it difficult to work with critical ESE in practice, thus inhibiting student autonomy and critical thinking. One pertinent challenge is the post-truth society, where facts and opinions have become negotiable (Peters, Citation2017; Van Poeck Citation2019). This has led to a situation in which facts are ignored or individuals treat facts as beliefs. Another challenge we want to point to is the educational system, which is increasingly instrumentalised, where knowledge measurement, accountability and stronger control of both teachers and students are inherent (Tryggvason, Öhman, and Van Poeck Citation2023). Therefore, institutions and social relations may foster critical thinking or suppress it (Burbules and Berk Citation1999). Tryggvason, Öhman, and Van Poeck (Citation2023) point to how increased instrumentality creates a larger gap between the educational system and ideals in ESE. The ESE positions are clear in that a desirable approach demands change; however, there is a need to raise the question of whether the positions explored here are an option at all for teachers in today’s schools. Wild pedagogies call for teachers to become rebels. Maybe that is necessary, but it is demanding on the teacher who mainly teaches inside a classroom, where the wild and rebellious might not be present due to other factors, such as reaching governmentally decided learning goals and testing and assessment procedures. Therefore, we need to ask whether it is fair for the burden (or golden opportunity) to be placed on individual teachers to turn these ideals into action. A third challenge faced in ESE is to what degree education should impact student behaviour when it comes to taking action for sustainable living. Our times call for rapid change; thus, indoctrination could be an effective measure (Tryggvason, Öhman, and Van Poeck Citation2023). Is now the right time for ESE positions that emphasise the importance of open-ended endeavours, free will and autonomy? Yet, by telling people how to live their lives, their autonomy and free will are jeopardised and education becomes an undemocratic endeavour – which is the opposite of what the ESE positions above wish to achieve. Simultaneously, the Earth itself has a larger say in how humans can live their lives, as it is getting warmer, leading to more unpredictable and more severe weather patterns, hence changing the conditions for life and living. In the context of sustainability issues, critical thinking is needed to change the patterns of thought and action that have led us into an unsustainable world.

The conceptualisations explored in this article are potential starting points for conscious choices when planning for critical thinking in ESE settings. Through this paper, we hope to show different aspects of critical thinking and make it easier for people to use the parts of the terms that are relevant to their particular research or educational practice. While the various perspectives offered on critical thinking in ESE differ in a number of respects, the provided model might aid in locating these positions in terms of their relative proximity. This might aid scholars within different fields of critical thinking and critical ESE to amplify one another in a dialogic sum, hence help avoid the problem of scholars talking over one another. The ESE positions we used as examples originated in different parts of the world, such as Scandinavia (pluralism and dark pedagogy), Canada (wild pedagogies) and Australia (pyropedagogies). Although three continents are represented, they have all originated in the Western world, and they are all mainly developed by middle-aged men. We do not point this out as being a bad thing, but as an aspect to be aware of, since there will be aspects of both critical thinking and ESE that fall outside of this scope, such as community-based and transformative environmental education, ecofeminism, deep ecology, ecojustice and climate change education, etc. (e.g. Iverson Citation2015; Kopnina Citation2014; Martusewicz, Edmundson, and Lupinacci Citation2021; Ruiz-Mallén et al. Citation2022; Van Poeck, Lysgaard, and Reid Citation2018). Therefore, there is a need for more research on critical thinking in ESE positions with other geographical and ontological foundations. Furthermore, the provided model is only a rough sketch. Additional work needs to be done to outline how the model can illuminate important issues in the field. Locating various positions on a model of critical thinking in ESE might be intrinsically interesting, but the important work to be done is in providing insights into how critical thinking can be best taught and incorporated in the curriculum. This is where the real value of the model will be tested. Therefore, there is a great need for more research on current educational practices and how the conceptualisations of critical thinking are engaged with. Empirical research on critical thinking is needed, especially on how critical thinking can be enacted in current educational systems, what ESE looks like in various educational practices at different grade levels and how teachers can work to enhance students’ critical thinking. If teachers are to engage with critical thinking as a concept, ideal and practice in education, further knowledge is important in order to offer insights into the challenges and potential of the notion.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the reviewers, Kirsti Marie Jegstad, Margareth Sandvik, Emilia Andersson-Bakken, Annelie Ott and members of COSER research group at the University of Oslo for giving us constructive feedback during the thinking and writing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marthe Berg Andresen Reffhaug

Marthe Berg Andresen Reffhaug is a PhD-student in educational science at the Department of Primary and Secondary Teacher Education at OsloMet - Oslo Metropolitan University. Her thesis is about critical thinking in environmental and sustainable education in primary school.

Jonas Andreasen Lysgaard

Jonas Andreasen Lysgaard is an associate professor in educational science at the Department of Education Studies at Danish School of Education at Aarhus University. His research interests are in the areas of environmental and sustainability education, philosophy of education, and history of the concept of education.

Notes

1 The history of the CT-movement is thoroughly explained in Shpeizer (Citation2018). Teaching critical thinking as a vehicle for personal and social transformation. Research in Education, 100, 32-49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034523718762176

2 For a comprehensive list of these definitions, see Johnson, R. H., & Hamby, B. (2015). A Meta-Level Approach to the Problem of Defining ‘Critical Thinking’. Argumentation, 29(4), 417-430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-015-9356-4

References

- Arnstein, S. R. 1969. “A Ladder of Citizen Participation.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 35 (4): 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225.

- Bailin, S., R. Case, J. R. Coombs, and L. B. Daniels. 1999. “Common Misconceptions of Critical Thinking.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 31 (3): 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/002202799183124.

- Bakhtin, M. 1986. Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. University of Texas.

- Barnett, R. 1997. Higher Education: A Critical Business. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Blenkinsop, S., M. Morse, and B. Jickling. 2022. “Wild Pedagogies: Opportunities and Challenges for Practice.” In Pedagogy in the Anthropocene: Re-Wilding Education for a New Earth, edited by M. Paulsen, J. Jagodzinski, and S. M. Hawke, 33–51. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90980-2_2.

- Burbules, N. 1993. Dialogue in Teaching: Theory and Practice. New York, NY, USA: Teachers College Press.

- Burbules, N. C., and R. Berk. 1999. “Critical Thinking and Critical Pedagogy: Relations, Differences, and Limits.” In Critical Theories in Education: Changing Terrains of Knowledge and Politics, edited by T. Popkewitz and L. Fendler. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

- Burbules, N. C., and B. R. Warnick. 2006. “Philosophical Inquiry.” In Handbook of Complementary Methods in Education Research, edited by J. L. Greene, G. Camilli, and P. B. Elmore, 489–502. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

- Carlsson, M., and J. A. Lysgaard. (forthcoming). “Uddannelse og bæredygtighed. Pædagogisk indblik [Education & Sustainability, a Reseaerch Review].” Danish School of Education.

- Ceder, S. 2018. Towards a Posthuman Theory of Educational Relationality. New York, NY: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351044196.

- Cobb, P. 2007. “Putting Philosophy to Work.” In Second Handbook of Research on Mathematics Teaching and Learning: A Project of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, edited by F. K. J. Lester. Charlotte, NC, USA: Information Age Publishing.

- Davies, M. 2015. “A Model of Critical Thinking in Higher Education.” In Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, edited by M. B. Paulsen, 41–82. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Dewey, J. 1910. How We Think. Boston, MA, USA: D. C. Heath & co., publishers.

- Ennis, R. 1985. “A Logical Basis for Measuring Critical Thinking Skills.” Educational Leadership 43 (2): 44–48.

- Ennis, R. 2018. “Critical Thinking across the Curriculum: A Vision.” Topoi 37 (1): 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-016-9401-4.

- Facione, P. 1990. Critical Thinking: A Statement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction. Executive Summary. The Delphi Report. Milbrae, CA, USA: T. C. A. Press.

- Facione, P. 2020. “Critical Thinking: What It is and Why It Counts.” Insight Assessment.

- Ferrer, M., H. S. Johannesen, A. Wetlesen, and P. A. Aas. 2021. “Burde Greta heller vært på skolen? Om vilkårene for systemkritisk tenkning i skolen, med elevenes klimaopprør som utgangspunkt [Shouldn’t Greta Just Go to Class? A Discussion of the Conditions of Systemic Criticism in Schools, Using School Strikes for Climate as a Starting Point].” Norsk sosiologisk tidsskrift 5 (5): 19–36. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2535-2512-2021-05-02.

- Freire, P. 1998. Pedagogy of Freedom: Ethics, Democracy, and Civic Courage. Lanham, MD, USA: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Gough, S., and W. Scott. 2003. Sustainable Development and Learning: Framing the Issues. Sussex, England: Psychology Press.

- Guterres, A. 2021. Secretary-General’s Statement on the IPCC Working Group 1 Report on the Physical Science Basis of the Sixth Assessment. UN.org. Retrieved 09.08.21 from https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/secretary-generals-statement-the-ipcc-working-group-1-report-the-physical-science-basis-of-the-sixth-assessment?_gl=1*1s9hdrr*_ga*NzAxMTkyNzI2LjE2MTgxMDc2NzE.*_ga_TK9BQL5X7Z*MTY3NDAzNDAyMS4xLjEuMTY3NDAzNDA5My4wLjAuMA.

- Hart, R. 2008. “Stepping Back from ‘The Ladder’: Reflections on a Model of Participatory Work with Children.” In Participation and Learning, edited by A. Reid, B. B. Jensen, J. Nikel, and V. Simovska, 19–31. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Hodgson, J., W. Rønning, and P. Tomlinson. 2012. “Sammenhengen mellom undervisning og læring. En studie av læreres praksis og deres tenkning under Kunnskapsløftet. Sluttrapport 4 [the Coherence between Teaching and Learning: A Study of Teachers’ Practice and Thinking during Knowledge Promotion. Report 4].”

- Iverson, S. V. 2015. “The Potential of Ecofeminism to Develop ‘Deep’ Sustainability Competencies for Education for Sustainable Development.” The Seneca Falls Dialogues Journal 1, Article 4.

- Jegstad, K. M., and E. Ryen. 2020. “Bærekraftig utvikling som tverrfaglig tema i grunnskolens naturfag og samfunnsfag – en læreplananalyse. [Sustainable Development as an Interdisciplinary Topic in the Norwegian School Subjects Natural Sciences and Social Studies – a Curriculum Analysis].” Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift 104 (3): 297–312. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-2987-2020-03-07.

- Jensen, B. B., and K. Schnack. 1997. “The Action Competence Approach in Environmental Education.” Environmental Education Research 3 (2): 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350462970030205.

- Jickling, B. 1992. “Why I Don’t Want My Children to Be Educated for Sustainable Development.” The Journal of Environmental Education 23 (4): 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1992.9942801.

- Jickling, B. 2013. “Normalizing Catastrophe: An Educational Response.” Environmental Education Research 19 (2): 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2012.721114.

- Jickling, B. 2018. “Preface.” In Wild Pedagogies: Touchstones for Re-Negotiating Education and the Environment in the Anthropocene, edited by B. Jickling, S. Blenkinsop, N. Timmerman, and M. D. D. Sitka-Sage, vii–xiv. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave macmillan.

- Jickling, B., S. Blenkinsop, N. Timmerman, and M. D. D. Sitka-Sage. 2018. Wild Pedagogies: Touchstones for Re-Negotiating Education and the Environment in the Anthropocene. Cham: Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Johnson, R. H., and B. Hamby. 2015. “A Meta-Level Approach to the Problem of Defining ‘Critical Thinking.” Argumentation 29 (4): 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-015-9356-4.

- Jónsson, Ó. P., B. Guðmundsson, A. B. Øyehaug, R. J. Didham, L.-A. Wolff, S. Bengtsson, J. A. Lysgaard, et al. 2021. Mapping Education for Sustainability in the Nordic Countries https://doi.org/10.6027/temanord2021-511.

- Kopnina, H. 2014. “Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) as If Environment Really Mattered.” Environmental Development 12: 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2014.09.001.

- Kuhn, D. 2019. “Critical Thinking as Discourse.” Human Development 62 (3): 146–164. https://doi.org/10.1159/000500171.

- Lieberkind, J. 2015. “Democratic Experience and the Democratic Challenge: A Historical and Comparative Citizenship Education Study of Scandinavian Schools.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 59 (6): 710–730. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2014.971862.

- Lim, L. 2015. “Critical Thinking, Social Education and the Curriculum: Foregrounding a Social and Relational Epistemology.” The Curriculum Journal 26 (1): 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2014.975733.

- Long, D. E., and J. A. Henderson. 2024. “Emergent Forms of ‘Dark Green Religion’ and the (Ecofascist) Future of Environmental Education in the United States.” Environmental Education Research 2024: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2024.2359455.

- Lysgaard, J. A. 2018. Laerning from Bad Practice in Environmental and Sustainability Education. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing, Inc.

- Lysgaard, J. A., and S. Bengtsson. 2022. “Action Incontinence: Action and Competence in Dark Pedagogy.” In Pedagogy in the Anthropocene: Re-Wilding Education for a New Earth, edited by M. Paulsen, J. Jagodzinski, and S. M. Hawke, 107–128. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90980-2_6.

- Lysgaard, J. A., S. Bengtsson, and M. H.-L. Laugesen. 2019. Dark Pedagogy: Education, Horror and the Anthropocene. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lysgaard, J. A., and N. J. Jørgensen. 2020. “Bæredygtighed og viden i krise [Sustainability and Knowledge in Crisis].” In Bæredygtighetens pædagogik: Forskningsperspektiver og eksempler fra praksis, edited by J. A. Lysgaard and N. J. Jørgensen, 90–106. Frederiksberg C, Denmark: Frydenlund Academic.

- Marcinkowski, T., and A. Reid. 2019. “Reviews of Research on the Attitude–Behavior Relationship and Their Implications for Future Environmental Education Research.” Environmental Education Research 25 (4): 459–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1634237.

- Martusewicz, R. A., J. Edmundson, and J. Lupinacci. 2021. EcoJustice Education: Toward Diverse, Democratic, and Sustainable Communities. 3rd ed. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

- Mogensen, F., and K. Schnack. 2010. “The Action Competence Approach and the ‘New’ Discourses of Education for Sustainable Development, Competence and Quality Criteria.” Environmental Education Research 16 (1): 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620903504032.

- Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training. 2020. Core Curriculum – Values and Principles For Primary and Secondary Education. https://www.regjeringen.no/en/dokumenter/verdier-og-prinsipper-for-grunnopplaringen–-overordnet-del-av-lareplanverket/id2570003/

- Öhman, J., and L. Östman. 2008. “Clarifying the Ethical Tendency in Education for Sustainable Development Practice: A Wittgenstein-Inspired Approach.” Canadian Journal of Environmental Education 13: 57–72.

- Öhman, J., and L. Östman. 2019. “Different Teaching Traditions in Environmental and Sustainability Education.” In Sustainable Development Teaching: Ethical and Political Challenges, edited by K. Van Poeck, L. Östman, and J. Öhman, 70–82. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

- Ott, A. 2019. “Kritisk Tenkning og Bærekraft i Fagfornyelsen [Critical Thinking and Sustainability in the New Curriculum].” In Kritisk tenkning i samfunnsfag [Critical thinking in social science], edited by M. Ferrer and A. Wetlesen, Vol. 1, 30–49. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Papastephanou, M., and C. Angeli. 2007. “Critical Thinking beyond Skill.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 39 (6): 604–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-5812.2007.00311.x.

- Paul, R., and L. Elder. 2009. “Critical Thinking, Creativity, Ethical Reasoning: A Unity of Opposites.” In Morality, Ethics, and Gifted Minds, edited by T. Cross and D. Ambrose, 117–131. New York, NY, USA: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-89368-6_8.

- Paulsen, M. 2021. “Cautiousness as a New Pedagogical Ideal in the Anthropocene.” In Rethinking Education in Light of Global Challenges, edited by K. B. Petersen, K. von Brömssen, G. H. Jacobsen, J. Garsdal, M. Paulsen, and O. Koefoed, 220–233. New York, NY, USA: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003217213-17.

- Paulsen, M. B., j Jagodzinski, and S. M. Hawke. 2022. “A Critical Introduction.” In Pedagogy in the Anthropocene, edited by M. B. Paulsen, J. Jagodzinski, and S. M. Hawke. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-90980-2_1.

- Peters, M. A. 2017. “Education in a Post-Truth World.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 49 (6): 563–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2016.1264114.

- Popkewitz, T. 1999. “Introduction. Critical Traditions, Modernisms, and the “Posts.” In Critical Theories in Education: Changing Terrains of Knowledge and Politics, edited by T. Popkewitz and L. Fendler. New York, NY, USA: Routledge.

- Reid, A. 2019. “Climate Change Education and Research: Possibilities and Potentials versus Problems and Perils?” Environmental Education Research 25 (6): 767–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1664075.

- Reunamo, J., and A. Pipere. 2011. “Doing Research on Education for Sustainable Development.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 12 (2): 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676371111118183.

- Rieckmann, M. 2018. “Learning to Transform the World: Key Competencies in Education for Sustainable Development.” In Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development, edited by A. Leicht, J. Heiss, and W. J. Byun, 39–59. UNESCO, Unesco. org or Unesdoc digictal library, https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000261445

- Rudsberg, K., and J. Öhman. 2015. “The Role of Knowledge in Participatory and Pluralistic Approaches to ESE.” Environmental Education Research 21 (7): 955–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2014.971717.

- Ruiz-Mallén, I., M. Satorras, H. March, and F. Baró. 2022. “Community Climate Resilience and Environmental Education: Opportunities and Challenges for Transformative Learning.” Environmental Education Research 28 (7): 1088–1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2022.2070602.

- Scheie, E., T. Berglund, E. Munkebye, R. Lyngved Staberg, and N. Gericke. 2022. “Læreplananalyse av Kritisk Tenking og Bærekraftig Utvikling i Norsk og Svensk Læreplan [Curriculum Analysis of Critical Thinking and Sustainable Development in the Norwegian and Swedish Curricula].” Acta Didactica Norden 16 (2): 32. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.9095.

- Searle, J. R. 1969. Speech Acts. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Shpeizer, R. 2018. “Teaching Critical Thinking as a Vehicle for Personal and Social Transformation.” Research in Education 100 (1): 32–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034523718762176.

- Siegel, H. 2010. “Critical Thinking.” In International Encyclopedia of Education, edited by P. Peterson, E. Baker, and B. McGaw, 3rd ed., 141–145. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.00582-0.

- Sund, P. J., and N. Gericke. 2021. “More than Two Decades of Research on Selective Traditions in Environmental and Sustainability Education—Seven Functions of the Concept.” Sustainability 13 (12): 6524. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126524.

- Sund, P., N. Gericke, and G. Bladh. 2020. “Educational Content in Cross-Curricular ESE Teaching and a Model to Discern Teacher’s Teaching Traditions.” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 14 (1): 78–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973408220930706.

- Taylor, C. A., and A. Bayley. 2019. Posthumanism and Higher Education: Reimagining Pedagogy, Practice and Research. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14672-6.

- The Crex Crex Collective. 2018. “Why Wild Pedagogies.” In Wild Pedagogies: Touchstones for Re-Negotiating Education and the Environment in the Anthropocene, edited by B. Jickling, S. Blenkinsop, N. Timmerman, and M. D. D. Sitka-Sage, 1–22. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave macmillan.

- Thunberg, G. 2019. ‘Our house is on fire’: Greta Thunberg, 16, urges leaders to act on climate. The Guardian. Retrieved 25.1.2019 from https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/jan/25/our-house-is-on-fire-greta-thunberg16-urges-leaders-to-act-on-climate

- Tryggvason, Á., J. Öhman, and K. Van Poeck. 2023. “Pluralistic Environmental and Sustainability Education – A Scholarly Review.” Environmental Education Research 29 (10): 1460–1485. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2023.2229076.

- UiO. 2021. Addressing the Climate Emergency through Education. Oslo: Norway: University of Oslo. https://www.uio.no/studier/emner/sv/sv/OSS9103/.

- UNESCO. 2016. Action for Climate Empowerment: Guidelines for Accelerating Solutions through Education, Training and Puplic Awareness. https://unfccc.int/topics/education-and-outreach/resources/ace-guidelines

- Van Poeck, K. 2019. “Environmental and Sustainability Education in a Post-Truth Era. An Exploration of Epistemology and Didactics beyond the Objectivism-Relativism Dualism.” Environmental Education Research 25 (4): 472–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2018.1496404.

- Van Poeck, K., J. A. Lysgaard, and A. Reid. 2018. Environmental and Sustainability Education Policy: International Trends, Priorities and Challenges. New York, NY, USA: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203732359.

- Van Poeck, K., L. Östman, and J. Öhman. 2019. “Introduction.” In Sustainable Development Teaching: Ethical and Political Challenges, edited by K. Van Poeck, L. Östman, and J. Öhman, 1–12). Routledge.

- Vare, P., and W. Scott. 2007. “Learning for a Change: Exploring the Relationship between Education and Sustainable Development.” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 1 (2): 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/097340820700100209.

- Wals, A. E. J. 2011. “Learning Our Way to Sustainability.” Journal of Education for Sustainable Development 5 (2): 177–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/097340821100500208.

- Watson, J. C. 2024. Critical Thinking. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/critical-thinking/#SH7a.