Abstract

The Anthropocene is a geo-stratigraphic unit of the upper Earth’s layers, impacted by human disturbances, but also humankind’s historical record, and children’s place to live on. It is an unfinished narrative. This study explores how garden and soil-related activities with kindergarten children, guided by well-informed teachers, may have the potential to overcome some gaps of understanding of complex, interrelated concepts related to the Anthropocene and regenerative gardening. Within a framework of environmental citizenship, this qualitative study uses interdisciplinary, interactive and participatory approaches to explore inquiry-based activities based on observations, conversations, photos and videos. As participants in related processes, children may gradually develop garden skills, ecological knowledge and understanding of scientific concepts. The study may empower children and their teachers to contribute actively and positively to the ongoing narrative of the Anthropocene; to a more sustainable formation of the Earth’s upper layer; and to countering climate change.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS:

Introduction

Along with globally increasing urbanisation (UNFPA, Citation2007), in the future most of the world’s children will develop their nature-culture experiences, and connections with their local surroundings, in cities and urban areas. Since Crutzen & Stoermer (Citation2000) the discourse of the Anthropocene, a concept connecting nature and human culture, has influenced multiple scientific communities, including early childhood education for sustainability (ECEfS). However, most of the voices using the term Anthropocene outside the biogeosciences merely use it as an updated name for our current challenging time, where we face multiple complex and intertwined global crises (Sjögren, Citation2020, Allerberger & Stötter, Citation2022). Furthermore, this conceptualising of the Anthropocene as a ‘human epoch’ may in some respects be misleading, as a human epoch is a historical period, and can be replaced by a following historical epoch. This is not the case with the Anthropocene. As a potential formal geo-stratigraphic unit, the Anthropocene is a unit of strata in the Earth’s crust, recognisable all over the world, that we—and children—can dig into (Zalasiewicz, et al. Citation2019). The Anthropocene cannot be ‘replaced’. Parts of it are urban sediments, which we and children live on, and which most of us will live on in future (UNFPA, Citation2007). The geological Anthropocene includes our record in the soil which is like a book that we can read (Jefferson et al. Citation2013). We can learn from this record, and take and examine samples. Despite irreversible damage, the geological Anthropocene is an unfinished narrative (Zalasiewicz, et al. Citation2019). Both rural and city children search out the natural elements in their surroundings, like mud, trees, and water, even though environmental degradation is one of the factors that reduce the frequency of such positive experiences (Blair, Citation2009). Gardens are spaces for human-nature interrelationships. The plants’, and the soil’s sequestration of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere contribute to mitigate current ecological challenges, especially in urban contexts (Rashed, Citation2018). This qualitative study examines data gathered from activities with student preschool teachers in a community garden, and from activities in a kindergarten. The study adopts an integral view of children and their societal participation in ecological processes (Heggen et al. Citation2019; Andersen, Citation2023). The study explores the research question: How do children interact and communicate, while taking part in garden and soil activities, and how can preschool teachers facilitate their forming of Anthropocene-related concepts?

Theoretical background

Soils and sediments are huge, integrated parts of the Earth’s global ecosystem, and are essential for our agriculture-based global human society, and their food security and sustainability (Wild, Citation1993). Soils and sediments maintain plant growth and are sources and sinks for atmospheric gases. The terrestrial carbon cycle consists of primary producers, converting atmospheric carbon dioxide into organic compounds of living organisms, and of herbivores, carnivores, and decomposers which finally, through oxidation processes, return carbon dioxide to the atmosphere (Wild, Citation1993). This is among the subjects of ecological and garden learning (Desmond et al. Citation2004) and is further supported by soil education (Brevik et al. Citation2022). Gardens and soils provide common references for children across nations and cultures, and promote the playful development of skills, sensuous perceptions, interests and knowledge (Desmond et al. Citation2004; Blair, Citation2009; Bergersen, Citation2016; Brevik et al. Citation2022). Among numerous previous studies (Desmond et al. Citation2004; Blair, Citation2009), Miller (Citation2007) and Bergan et al. (Citation2023) underscore the teacher’s role to promote communication and collective learning during kindergarten children’s practical garden activities. Murakami (Citation2016) and Cheang et al. (Citation2017) provide examples of campus garden learning for undergraduate students.

Regenerative gardening includes various related, and integrated approaches aiming at the maintenance and regeneration of the natural soil compositions, carbon sequestration, soil fertility, biodiversity, food production and a regenerative society (Rusinamhodzi, Citation2019; Rashed, Citation2018). Mulching with organic materials and choosing suitable vegetation enhance carbon sequestration by absorbing CO2 and producing O2 and prevent CO2 loss from the soil (Rashed, Citation2018). The ‘4 per 1000’ Initiative supports the importance of gardening for countering climate change and suggests that an annual growth rate of only 0.4% of the standing global soil organic carbon stocks would ideally have the potential to counterbalance the current increase in atmospheric CO2, even if there are complex factors to consider (Rumpel et al. Citation2019).

Only in a few areas of the Earth, we can find naturally highly fertile soils, such as mollisols, also called black soils (Zech et al. Citation2022). Prehistoric, historic, and current humans all over the globe, have sought to create, to improve, or maintain fertile, humus-rich topsoils through manuring, cultivation and addition of suitable materials, to improve the growing of food, essential to human living (Bogaard, Citation2012; Shiel, Citation2012). Various international research on children’s gardening underlines that even young children can contribute to create, improve, and maintain soils for cultivation (Miller, Citation2007; Brevik et al. Citation2022; Bergan et al. Citation2023). Man-made anthropogenic soils and sediments, cultivation layers, or dark earth, have been identified worldwide during the last decades (Conry Citation1974; Bogaard, Citation2012), and recently even from the Amazon area (Madari et al. Citation2004), witnessing that humans’ impact on the upper Earth’s layers, has not just been negative.

The Anthropocene is now recognised as the current geological period during which human activity has been the profound influence on the environment (Crutzen & Stoermer, Citation2000; Lewis & Maslin, Citation2015), even if its formal inclusion in the International Chronostratigraphic Chart, which informs our official Geological Time Scale, awaits further ongoing investigation, related to criteria such as traceability in earth strata all over the world, and a clear transition to earlier periods (Zalasiewicz, et al., Citation2019; Luciano, Citation2022).

Together with all other biotic participants, each human, and in this way, each child is a member and citizen of the planet’s ecological system. Within this integral approach, the term citizen refers to each human member’s belonging to a broader local and global community and common humanity, based on universal values, common and individual responsibility, sharing of resources, critical thinking and active participation, and the recognition of intergenerational equity issues (Dean, Citation2001; Lee & Fouts, Citation2005; United Nations, Citation2015). Children with an active environmental identity may have an initial sense of belonging to our planet, and may develop a desire for care, solidarity, curiosity and knowledge (Heggen et al. Citation2019). Boyer et al. (Citation2022) use the term ‘cultures of aliveness’ to underline humankind’s close relationship with the Earth’s systems and their shared narratives, and the significance of intergenerational learning for both individual and the (global) community’s thriving.

Environmental citizenship education relates to environmental, economic, political, social, and cultural ways of understanding, acting and relating oneself to others and the environment (United Nations, Citation2015), in day-to-day contexts, based on a sociocultural learning paradigm (Bruner, Citation1960; Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Vygotzky, Citation1986). Communication and rhetorical agency are key for children to be included in practising environmental citizenship (Andersen, Citation2023) and underline that children’s interactions with the environment, and with each other, are both addressed. Supporting language development, and a common understanding of concepts, as well as the involvement of children in reasoning with other children, and with the teacher(s), are thus crucial elements for children’s subsequent participation in society (Bergersen, Citation2016).

Humans’ and children’s ‘understanding’ entails having a continuously developing mental model that represents the structure of a concept or phenomenon and can be transferred from one situation to another. A mental model or cognitive structure can generate predictions about the world (Halford, Citation2014, p. 238). Bruner (Citation1960) and Vygotzky (Citation1986) emphasise the importance of language and interaction in this connection.

Methodology

Studies in a community garden and in a kindergarten

This qualitative study uses an explorative interactive methodological approach (Svensson et al. Citation2015), and links a community garden, designed by student preschool teachers, with activities of children and adults in a kindergarten, all in Rogaland, Norway. The interactive approach underlines the joint learning between the participants and the researchers (Svensson et al. Citation2015). In line with the mosaic approach (Clark, Citation2017), children’s expressions, active participation and agency are particularly acknowledged. The researcher’s role is the reflexive understanding and linking of the study’s multiple perspectives (Svensson et al. Citation2015; Clark, Citation2017); during teaching and the collaboration with students, when spending time with the children in their kindergarten settings, during observations, both before and after conversations and video/audio recordings, when listening to the students and children, respectively, as well as during the data analysis (Clark, Citation2017; Vygotzky, Citation1986).

The ‘children’s garden’

The ‘Children’s Garden’ was founded in 2019 as a community garden, partly open for everyone, to give student preschool teachers an arena to explore the idea of regenerative gardening, close to the campus. The Stavanger municipality supplied about 300 m2 of grassland to facilitate students’ experiences with organising organic cycles of growth and decomposition, close to the university campus. Collaboration with the Norwegian branch of a Seed Savers organisation (Kvann) started in 2021. Student preschool teachers were involved in activities in this garden since spring 2019. Later, a network of kindergartens was established, to learn in and from the ‘Children’s Garden’.

The kindergarten

The kindergarten in this study has focus on gardening and is a member of the Children’s Garden network (Bergersen, Citation2023). It has rather huge outdoor facilities, close to the woods. Its outdoor area of 5,000 m2 includes areas for rabbits, chicken pens, plant beds and several garden basins, and is used daily and actively with the children, also prior to this study.

Process and data collection

The study was approved by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (NSD, Sikt since 2022), approval number: 920483. The kindergarten sent out information to parents, who were asked to decide, together with their child, whether to give permission to participate or not. It was made clear that children without permission would be included in the activities, but without video, or audio recording. All parents gave their permission.

The students involved in activities related to the community garden, and the kindergarten children, were introduced to the study’s purpose and to the use of video- and/or audio recording, and attention was paid especially to the children’s possible verbal and/or non-verbal expressions of being uncomfortable at any time and their right to withdraw from participation (Clark, Citation2017). The activities and questions were continuously adapted so as to be understandable for each child.

From spring 2019 until spring 22, both planning and seasonal activities were conducted in the Children’s Garden, mainly together with two student preschool teacher cohorts (due to Covid-19 interruptions in 2020 and partly 2021), and mainly related to a course in nature and outdoor pedagogy. Fieldwork in the kindergarten started with two introductory teaching sessions for the preschool teachers in spring 2021. The preschool teachers of the kindergarten were included in all further activities.

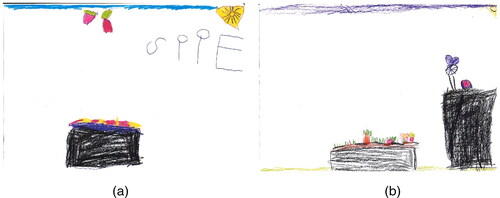

During 2021 and until spring 2022, planned and teacher-led, as well as everyday soil- and garden-related activities with the children (3 - 6-year-old) were conducted and/or took place in the kindergarten. Inspired by Clark (Citation2017), these activities were followed by reflective activities, i.e. activities that enabled the children to reflect on and to listen to each other’s reflections on the soil- and garden activities, like drawing, to facilitate children’s creative expression of their perceptions (see ). Data from these activities were collected as notes, photos, video and/or audio recordings of observations, and group conversations, including the children.

Data analysis and presentation

Data were analysed and selected through discussions with the preschool teachers, reflective analysis and interpretations (Battersby & Bailin, Citation2011), with special focus on the activity’s content, the children’s physical and social participation, and their verbal and non-verbal expression. The data were partly transcribed and compiled as reflected and reconstructed narratives (Clandinin, Citation2016; Nasheeda et al. Citation2019), while being aware of influence from the researchers’ pre-interpretations, beliefs and biases (Battersby & Bailin, Citation2011; Creswell & Poth, Citation2017). The narratives were further analysed, using qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). The selected and summarising two narratives representing our findings build on the activities’ context. The narrative from the kindergarten communicates significant excerpts from activities with the children. However, only the recorded verbal expressions of the children are included, as it was impossible to note all verbal interchanges between the children. According to Clark (Citation2017), four children’s drawings from a selected activity are part of the presented data (, along with the two narratives. All information was handled confidentially, and after the data collection, the individual identifiers were permanently removed.

Results

Activities in the ‘Children’s garden’

The challenge for the first student cohort in spring 2019, was to transform the oblong strip of grassland into something suitable for children’s exploration. Different student groups and individuals participated in this enterprise. Later, in 2019 and in 2021, two student cohorts specialising in outdoor pedagogy participated in designing suggestions for such a child-centred community garden. Their suggestions, which were also realised later in the growing season, included appeals for children’s physical and sensorial exploration, for example growing tunnels, and activities thematising ecological interrelationships, like the making of compost, and growing plants.

The aim was also to transform this grassland into a food producing ecosystem applicable for kindergartens. Parts of the grassland were turned into a series of half-buried garden beds for edible plants. Discussion with the students underscored that this action temporarily destroys some of the organic life in established soil strata, but improves the initially very compact soil structure. Another series of garden beds were established for decomposition. In between them, an area of grassland was maintained, to supply grass for mulching. The compost beds were built of locally available raw materials for compost and mulching such as wood chippings, brushwood, seaweed, marine shell, wool, bio char and coffee grounds, partly sampled by students.

Gardening beds with perennial species like onion (Allium, amaryllis family), and Caucasian spinach (Hablitzia tamnoides, amaranth family) were established. The students’ courses thematised how bokashi a fermented compost supports the growth of annual species in the cabbage family (Brassica) and mulching with covering like wool supports the growth of the perennial species like Caucasian spinach. A self-regenerating ecosystem with edible perennials and annuals, supported by grass cuttings, wood chippings, and bokashi (fermented organic matter), slowly emerged, and gave necessary experience for the development of activities to introduce in kindergarten.

Soil and garden related activities in the kindergarten

In early spring 2021, the kindergarten’s teachers had introductory sessions about regenerative gardening and how to initiate inquiry-based environmental activities, to inspire the kindergarten’s established everyday garden related activities with the children, during the following year.

The kindergarten started with the production of bokashi compost in the kindergarten kitchen. The children were included in related simple activities, for example the regular gathering of leftover food to add to the bokashi box. While the children could daily see, smell, and even touch the bokashi, they could also follow its ecological transformation. During collaborative social processes, together with the adults and peers, they could explore, ask and discuss questions in the related everyday situations and get a beginning understanding that fermentation is part of a cycle of ecological processes that connect food, food decay and growing plants in the garden.

During outside activities, the children explored earthworms and other animals living in the soil. While the children included the earthworms in their play, caring for them, and, for example, creating houses and beds for them, the adults explained the earthworms’ importance for the garden as decomposers and as mixers of the soil to keep it porous.

In October 2021, the oldest children in the kindergarten, three girls and three boys, aged 5 years were included in a researcher-initiated activity about the carbon cycle. A round table conversation with a poster of a simple carbon cycle and related processes was used to discuss with the children in relation to carbon dioxide emission and carbon sequestration, and to the meaning of an ‘ecological footprint’. A simple model of the Earth’s layers was used to give the children a beginning understanding of geological layers. Later, the children explored the local ground of the outdoor area next to the kindergarten for different layers. The preschool teachers used the introduction material to revisit these topics with the children during later everyday activities.

On 19 November 2021, eight boys and four girls (all 4- and 5-year-old) gathered in a room, together with three preschool teachers and three researchers. One of the researchers (not a co-author) initiated the conversation by asking; ‘…some of you asked what we shall do in the garden at this time of the year? It is nearly winter. It is necessary to do something in the garden’. After a short story about a child and its garden, we went outside with the children, and they became engaged in various activities.

The children could touch and use their spades to dig in the ground, while one of the researchers explained that the upper layer in the pine wood was full of living roots, while the layers below contained more sand and small stones. Some of the children put the various soil layers in their buckets, presumably pretending that it was food, as a 4-year-old boy said: ‘Do you want spaghetti?’.

Then, the children inspected the garden basins and cleaned them of garbage and weeds. Wheelbarrows were fetched. Most of the children were very engaged and some helped to transport the compost from the kindergarten’s kitchen bokashi in some of the wheelbarrows, which were pushed to the plant basins. Some children collected leaves from the ground around the kindergarten. These materials were put onto the garden basins. Some of them were overgrown by chickweed (Stellaria media), which already provided good protection of the ground for the winter. However, eagerly, some of the chickweed was drawn out. ‘When we are working, we get dirty…’, one of the children said, while all of them concentrated on their tasks, ‘…even if you are working with a car, you get dirty’. ‘What are you doing’ asked another child, and some others shouted, ‘the earthworms just get more and more debris’; ‘It smells very strange’. The children used shovels and their hands to move the debris over from the wheelbarrows to the garden basins, and to spread the material, for example around some curly kales (Brassica oleracea). ‘It is ok with the eye now’, a girl said after getting some dirt in her eye. Most of the time, the children were engaged silently. However, some were occasionally talking here and there, as the following conversation exemplifies:

A child said, ‘Don’t take it’.

‘An earthworm’, another child answered.

‘Can you do it?’, a third child said.

‘Put it into there’, the first child shouted.

‘I can help’, a fourth child spoke out.

‘I found an earthworm’, a fifth child shouted out.

‘Look, the earthworm is under there’, the second child commented,

‘…’, one of the children added something not understandable.

‘It is under the soil, I want it in my basket’, the first child shouted.

‘Where is it you will work?., the fourth child asked.

A sixth child commented, ‘We are working, and you are not working’.

‘We need…’, one of the children resumed.

‘Lucas feels a little warm’, the fourth child pointed out.

‘A spider!’, one of the other children shouted from a distance.

‘There is mandarin orange peel. … this will become soil’, the fifth child noticed.

A preschool teacher explained that the material contained waste from the kitchen and was not yet fully decayed to soil. All uncovered soils in the plant basins were further covered with a layer of the bokashi material, and a layer of leaves. In some of the basins, the children prepared small holes with their hands and into them put tulip bulbs (Tulipa L.), seeds of carrot (Daucus carota subsp. sativus), and red radish (Raphanus raphanistrum, subsp. sativus), respectively. Some of the basins were also covered with a layer of sheep’s wool, which one of the collaborating researchers had brought along. The adults explained and discussed with the children why we use these materials, and that this is to protect the ground. While the children were very engaged in, and concentrated on the processes, several boys and girls shouted out:

‘Here is the wool’, a child shouted out.

‘I have seen this on TV’, another child commented.

‘We have to put it up’, the first child continued.

‘Can I help you?’ a third child joined that conversation.

A child from further away explained, ‘I will make more holes (for bulbs and seeds)’.

The first child shouted, ‘He touches the peels’, addressing a peer,

who nearly simultaneously pointed out, ‘He (an earthworm) is alive’.

‘Shall we fill it?’, the third child asked, and continued, ‘There, we will put a lot of wool’.

‘It is from sheep’, some of the children said.

The first child pointed out, ‘We need more wool’.

A girl said, ‘And afterwards, shall we put the wool onto the flowers?’

Another girl said, ‘I am washing myself, I am washing myself’, while she rubbed up the wool against her hands.

The children seemed to be happy with the activity and some laughing comes up from times to others. ‘What are you doing?’; ‘Put it upon’; ‘We have to draw (the wool into smaller parts)’. ‘We can add a lot (material)’. The adults answered the children and explained details during the activities. Later, however, a girl just looked at the others, ‘I don’t know (if I want to continue) … because it gets cold)’.

During the meal after this half-day activity, the adults followed the children’s conversations. They didn’t seem to relate so much to the recently completed activity, apart from some possibly related comments like, ‘We should make piles (later in the garden) … of pallets’. Also, some children mentioned ‘spiders’ and ‘guinea pigs’.

While the children could observe, touch, talk about and play with the garden basins every day during their outdoor time around the kindergarten, as an adult-initiated activity, the garden basins were revisited on 22 February 2022. During their outdoor time, all children who were interested could join an adult-guided ‘trip’ along the basins, where they could all use their spades and touch, while the adults recalled ecological interrelations and encouraged the children to ask, to remember, and to discuss. It was cold and snowing, and after an hour, the activity continued indoors, where the 4- and 5-year-old children were invited to draw on A4 paper. The seven children who accepted this invitation prepared drawings showing plant basins with various kinds of visible layers (see examples in ). A girl commented on her drawing (: ‘The pink layer is made of sweets… and there is radish.’

Discussion

How do children interact and communicate, while taking part in garden and soil activities, and how can preschool teachers facilitate their forming of Anthropocene-related concepts?

Theory and practice in the kindergarten

This study sought to facilitate, analyse and understand the continuous and spontaneous joint learning (Svensson et al. Citation2015) of the researchers, the student preschool teachers, the preschool teachers, and the kindergarten children, seeing all as capable and contributing participants (Svensson et al. Citation2015; Heggen et al. Citation2019, Murakami, Citation2016; Cheang et al. Citation2017). Both in the community garden and in the kindergarten, students and/or teachers experienced and tried out garden-related activities, preferably together with kindergarten children, to explore how local and child adaptive perspectives can be developed with the help of theory and analysis (cf. Svensson et al. Citation2015).

The students and teachers, together with the researchers, started to get experience with interrelated complex concepts based on their open inquiry into the question of how children, together with adults, can create and carry out regenerative activities in a garden. They realised the kindergarten playgrounds and gardens as parts of the Anthropocene in a simplified, but concrete, practical and ‘hands-on’ perspective. Both the researchers’ introductory sessions, and the practice in the community garden, aimed to prepare preschool teachers and student preschool teachers to enhance children’s active participation ‘in further developing the Anthropocene’, with a focus on playful introductions to ecological knowledge. The current study can be understood as an abductive process in which a theoretical framework and local practices ‘that work’ in the kindergarten were continuously monitored, discussed and revised, like an interactive two-way flow of challenges between research and practice (Svensson et al. Citation2015).

Regenerative gardening requires knowledge of local characteristics of layers in the soil and knowledge concerning how gardening techniques influence these layers in the short and long term (Rumpel et al. Citation2019). However, a simplified understanding of the principles for regenerative gardening, such as an integral approach, constant soil covering, and organic manuring, is necessary in a kindergarten.

Involvement of the children

Including the children in sawing, cultivating, and harvesting of, for example, edible plants like red radish (Raphanus raphanistrum subsp. sativus), which many of the children remembered in their drawings (), introduced the children in our study to plant life cycles, to species knowledge, and to the ‘farm to fork’ concept. Another example is the establishment of deep-rooted plants to increase the organic carbon sequestration in the soil (Rashed, Citation2018). The related complicated interrelationships are difficult for children to understand. However, children’s involvement, curiosity and fascination may lead their inquiry in a variety of directions during an activity, and in time, the children will increase their understanding.

The use of the garden spaces around the kindergarten and of the grounds in the woods nearby, the involvement of the children in the preparation of bokashi and its transfer to the garden, as well as the cultivation of the garden beds, all introduced the children to the significance of soils and sediments in everyday life (Desmond et al., Citation2004; Blair, Citation2009; Brevik et al., Citation2022). According to Boyer et al. (Citation2022), bokashi is ‘the handcraft of soil-building’. The preparation of bokashi in the kindergarten allowed the children to touch, to smell and to use their senses, thereby making them aware of the ecological cycle of processes (Wild, Citation1993; Boyer et al., Citation2022). The children’s related and unrelated communications and play, during these activities, illustrate how environmental citizenship is about both children’s interactions with the environment, and with each other’s interactions (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Miller, Citation2007; Bergan et al., Citation2023; cf. Andersen, Citation2023), and thereby an integrating pedagogical resource.

Competences and skills about regenerative gardening and (bokashi) fermentation of organic materials are also related to intergenerational learning (Boyer et al. Citation2022; cf. Miller, Citation2007). Discussions with the children frequently included relations to the traditions of former times, such as covering the garden beds with locally available materials like wool and compost which can be traced in soils back to Neolithic times (Bogaard, Citation2012; Shiel, Citation2012). During the everyday practice together with the teachers, the children could learn from the soils, and even learn to read traces in the soil record—like earthworm holes, waste, or the layers which they have lain on by their own—making the soil similar to an unfinished narrative (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Vygotzky, Citation1986; Sageidet, Citation2012; Jefferson, et al. Citation2013; Zalasiewicz, et al. Citation2019). When the children found waste in the soil, this frequently entailed discussion of how it might damage nature.

The children could see that the bokashi they put on the garden beds was not fully decayed. They may have gained an initial understanding that added manure may stay as organic matter in soils for a very long time. The young children did not really understand that this happens in the form of humic acids, which can store organic carbon, in a similar way to peat or coal, and which can also prevent soil depletion (cf. Madari et al. Citation2004; Bogaard, Citation2012; Rashed, Citation2018). However, through their exploration of related concepts, the children may better understand that their measures in the garden are positive for the Earth.

Interaction and communication

Later, in early winter, not only bokashi, but also wool was transferred to the garden beds, and a girl asked, ‘…shall we put the wool [also] onto the flowers?’. This reaction may indicate that children easily associate wool with warm winter clothes. By transferring this association to the wool’s effect on the soil, the children may begin to develop a broader understanding of the concept of ‘covering’ (Halford, Citation2014, p. 238). Through their earlier or later experiences with sheep, some of the children may have understood that wool comes from sheep.

When the children, later in spring, helped to remove the wool from the garden beds, some may also have gained an initial understanding of the difference between the wool’s protecting role for the soil, and the bokashi’s role. The bokashi had fully disappeared at that later time. The earthworms’ mixing role in this connection was addressed during several activities. The children were very engaged in the earthworms during these playful introductions to these organisms of the terrestrial ecosystem and their role as decomposers (Wild, Citation1993). Expressions like, ‘He is alive!’, demonstrate how the children connected empathetically to the earthworms. The children seemed to gain an initial understanding that they and the earthworms had something in common, i.e. being alive, and being members of a community of organisms. Children’s play with earthworms or other (soil) animals may thus represent a ‘culture of aliveness’ (Boyer et al. Citation2022). The ecological, social and rhetorical aspects of such play may enact their eco-citizenship (Heggen et al. Citation2019).

In our study, we started several activities indoors, with the introduction of child-friendly models of concepts, such as a simplified poster of the carbon cycle. Also, the children were told narratives ahead of the outdoor activities. It is challenging, but also developmental for children to transfer models, concepts, or ideas from one situation to another (Halford, Citation2014, p. 238). However, the familiar day-to-day practices in the kindergarten’s indoor and outdoor spaces, within a joint community of children and adult learners, supported these mental processes in the children (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Vygotzky, Citation1986; Sageidet, Citation2012). We thus suggest that mental models of how humans can positively influence ecological processes in the Anthropocene can already be promoted and formed in kindergarten children, through the children’s active participation in relevant activities, as in this study.

The communication of the carbon cycle, and the plants’ capture of CO2 from the air, as well as the storage of organic carbon in the soil, were revealed to be especially challenging to grasp. However, the use of scientific terms appeared to be exciting for the children. Each revisiting of the experiences in the garden may increase their understanding (Bruner, Citation1960; Vygotzky, Citation1986; Miller, Citation2007). By creating a curious and reflexive community of learners in the kindergarten, the adults act as role models and promote collaborative inquiry, and both joint and individual learning processes (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Sageidet, Citation2012; Svensson et al. Citation2015). Offering practical activities as the starting point for children’s inquiry seems to be a fruitful approach to engaging young children in investigating complex concepts, as also found in Miller (Citation2007) and Bergan et al. (Citation2023).

During the garden activities described, both the adults and the children built on earlier knowledge, as exemplified by a child who recognised that, ‘When we are working, we get dirty…’, and another child who shouted out, ‘I have seen this on TV’. A similar connection to an earlier familiar experience was made by a 4-year-old boy who associated the soil layers in the pine wood activity with ‘… spaghetti.’, and thus, probably with ‘food preparation’ in the sandbox. In the pine wood, the children listened excitedly, but mostly silent, to the adult’s explanation of the upper soil layers, while they dug and touched the soil. Their silence may underline that children’s connection to earlier experiences may also be non-verbal, and merely by using the senses (cf. Clark, Citation2017).

Some of the children obviously understood the introduced term ‘layer’, as reflected in their drawings, prepared indoors, after the revisiting and manuring of the garden basins (see ). A girl commented on her drawing ( with, ‘The pink layer is made of sweets’. This analogical way of relating new and previous experiences supports the children’s collective memory-making (Vygotsky, 1986). Preschool teachers may build on various forms of children’s thinking and encourage them to move further and develop their discursive skills to tell and explain to others (Robsen, Citation2006, p. 6). By commenting on their own drawings, the children could express their own ideas and theories about their experiences (Sageidet, Citation2012), and literally ‘draw’ their own outcomes from the activity, in line with Clark (Citation2017).

Children’s initial understandings over time

The children obviously become more familiar with the kindergarten’s gardens and grounds during the activities over time (cf. Bergan et al., Citation2023). They may eventually develop their understanding that some places are for food production, while others have other functions, and they may begin to understand what the various places have in common, for example, supported by the terms introduced by the adults, such as ‘ground’, ‘sand’, ‘gravel’, ‘loam’ and ‘mulch’. The children may develop mental models (Halford, Citation2014), for example by making superior connections between the ground covering in the woods, the covering in the garden, and the covering in their sand box, and they may wonder about similarities and differences. From becoming familiar with the local soils and with gardening, the children may begin to understand that soils play a key role in food production. They may also understand that humans, too, have an important role in food production (Brevik et al. Citation2022). Through additional storytelling about earlier generations’ use of soils and gardens (cf. Bogaard, Citation2012; Shiel, Citation2012), the children may gain an initial understanding that their local soils are of anthropogenic origin.

Conclusion

Gardens and soils and their ecological processes are complex subject matter, and children cannot yet fully understand them. This study explored the potential of garden and soil-related activities in a kindergarten, guided by theoretically informed preschool teachers, and supported by simplified communication to bridge the gaps of understanding of a series of complex and interrelated concepts such as the layering of the soil, the CO2 cycle, the idea of ‘from farm to fork’, regenerative gardening, and the Anthropocene. The term ‘Anthropocene’ requires thinking in terms of timescales and distances, far beyond even adult’s imagination (Allerberger & Stötter, Citation2022). For children, there is a gigantic step from a beginning understanding of the layering in the local soils, to an understanding of the layering of the Earth.

However, if supported by playful activities, reasoning and continuous revisiting, simplified conceptualisation involving analogy, and by critical inquiry into local ground covering and soil phenomena, children may develop an increasing understanding of interrelationships by time (Miller, Citation2007; Gulay et al. Citation2010; Svensson et al. Citation2015). Challenging children early, may offer them opportunities to develop mental models based on knowledge, competences, and language that can later be adjusted and undergo more complex development (Vygotzky, Citation1986; Gulay et al. Citation2010; Halford, Citation2014). While children may gradually develop garden skills, ecological and social knowledge, and a beginning understanding of interrelated scientific concepts (cf. Miller Citation2007; Murakami, Citation2016), the teacher’s knowledge and pedagogy are key to facilitating and guiding children in this regard.

Children may gain an initial understanding that soils are not something good or bad, but living layers of space that can be explored, but also need care. In the Anthropocene, it is important to give children the confidence that their (urban) surroundings are not only negative and separated from the ecology of the planet, but also a vital part of it, providing a range of possibilities for children’s human-nature interrelationships. Children may ‘grow’ into a learning culture (Bruner, Citation1960; Lave & Wenger, Citation1991) that values soils and gardens as unreplaceable resources and spaces we live on (Zalasiewicz, et al. Citation2019).

Kindergarten gardens may be considered to have only symbolic significance for economic or ecological sustainability. However, in the broadest sense, there have been similar views on small-holders and family farmers, worldwide, who have received increasing attention as examples of an equilibrated coexistence of humans and nature (Madari et al. Citation2004). United Nations (Citation2015) and the ‘4 per 1000’ initiative (Rumpel et al. Citation2019) underscore the important role of cultivating, and its learning potential for people’s livelihoods through time and across cultures. Brevik et al. (Citation2022) underline the importance of soil education for both the environment and society. This study underlines the importance of giving children hope and developing children’s capacity to contribute positively to the further building, and addressing the issues of the Anthropocene, as an ongoing narrative. By participating in decomposition and cultivation activities, children can contribute to countering climate change (Rumpel et al. Citation2019). Thus, children really ‘can do something with the Anthropocene’. By such climate actions, children contribute to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal 13 (SDG 13: climate action, United Nations, Citation2015) and can find a way to engage in civic matters that not only include humans, but also constitute an ecological citizenship (Dean, Citation2001, Heggen et al. Citation2019).

This study values an open atmosphere for learning across various other perspectives of education in and for the Anthropocene (Svensson et al. Citation2015; Sjögren, Citation2020; Zalasiewicz et al. Citation2019; Allerberger & Stötter, Citation2022). Further research is necessary, specifically of how to build bridges between scientific concepts and young learners, and how to empower teachers to develop pedagogical practices to facilitate children’s active, and capable participation in transitions—like improving the upper Earth’s layer—to achieve the Global Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, Citation2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Faculty of Arts and Education, University of Stavanger, and supported by the Filiorum - Centre for Research in Early Childhood Education and Care, University of Stavanger (funded by the Research Council of Norway). Many thanks to Kari Grutle Nappen, Maritha Berger Nylund and the staff of the study’s kindergarten for field work collaborations and discussions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allerberger, F., and J. Stötter. 2022. “Anthropocene – Humankind as Global Actor: Insights into Historic and Current Perspectives.” Die Erde – Journal of the Geographical Society Berlin 153 (3): 138–148. https://doi.org/10.12854/erde-2022-631.

- Andersen, I. V. 2023. “Rhetorical Citizenship and the Environment.” Climate Resilience and Sustainability 2 (2): E 249. https://doi.org/10.1002/cli2.49.

- Battersby, M., and S. Bailin. 2011. “Critical Inquiry: Considering the Context.” Argumentation 25 (2): 243–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10503-011-9205-z.

- Bergan, V., M. B. Nylund, I. L. Midtbø, and B. H. Landsem Paulsen. 2023. “The Teacher’s Role for Engangement in Foraging and Gardening Activities in Kindergarten.” Environmental Education Research 30 (1): 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2023.2181271.

- Bergersen, O. 2023. February 28). Barnas hage på Ullandhaug. Forskning UiS. https://www.uis.no/nb/forskning/barnas-hage-pa-ullandhaug

- Bergersen, O. (Ed.) 2016. Barns Flerkulturelle Steder—Kulturskaping, Retorikk Og Barnehageutvikling. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Blair, D. 2009. “The Child in the Garden. An Evaluative Review of the Benefits of School Gardening.” The Journal of Environmental Education 40 (2): 15–38. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOEE.40.2.15-38.

- Bogaard, A. 2012. “Middening and Manuring in Neolithic Europe: Issues of Plausibility, Intensity and Archaeological Methods.” In Manure Matters – Historical Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives, edited by, R. Jones, (p. 25–40). London: Routledge.

- Boyer, B., M. Wernli, M. Koria, and L. Santamaria. 2022. “Our Own Metaphor: Tomorrow is Not for Sale.” World Futures 78 (8): 524–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/02604027.2021.2014751.

- Brevik, E. C., J. Hannam, M. Krzic, C. Muggler, and Y. Uchida. 2022. “The Importance of Soil Education to Connectivity as a Dimension of Soil Security.” Soil Security 7 (2022): 100066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soisec.2022.100066.

- Bruner, J. 1960. The Process of Education. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Cheang, C. C., W.-M. W. So, Y. Zhan, and K. H. Tsoi. 2017. “Education for Sustainability Using a Campus Eco-Garden as a Learning Environment.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 18 (2): 242–262. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-10-2015-0174.

- Clandinin, D. J. 2016. Engaging in Narrative Inquiry. London: Routledge.

- Clark, A. 2017. Listening to Young Children. Jessica London and Philadelphia: Kingsley Publishers.

- Conry, M. J. 1974. “Plaggen Soils: A Review of Man-Made Raised Soils.” Soils and Fertilizers 37: 319–326.

- Creswell, J. W., and C. N. Poth. 2017. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches (4th edition). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Crutzen, P. J., and E. F. Stoermer. 2000. “The ‘Anthropocene.” Global Change Newsletter 41: 17–18.

- Dean, H. 2001. “Green Citizenship.” Social Policy & Administration 35 (5): 490–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9515.t01-1-00249.

- Desmond, D., J. Grieshop, and A. Subramaniam. 2004. Revisiting garden-based learning in basic education. Roma, Paris: FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) and UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning. https://www.fao.org/3/aj462e/aj462e.pdf

- Gulay, H., S. Yilmaz, E. T. Gullac, and A. Onder. 2010. “The Effect of Soil Education Project on Pre-School Children.” Educational Research and Review 5 (11): 703–711. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ911918.

- Halford, G. S. 2014. Children’s Understanding—The Development of Mental Models (1st edition, 1993). New York: Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315801803.

- Heggen, P. M., B. M. Sageidet, N. Goga, L. T. Grindheim, V. Bergan, T. A. Utsi, 1. Wallem Krempig, and A. M. Lyngård. 2019. “Children as Eco-Citizens?” Nordic Studies in Science Education 15 (4): 387–402. https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.6186.

- Hsieh, H.-F., and S. E. Shannon. 2005. “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis.” Qualitative Health Research 15 (9): 1277–1288. https://d0i.org/lO.1177/1049732305276687. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Jefferson, A. J., K. W. Wegmann, and A. Chin. 2013. “Geomorphology of the Anthropocene: Understanding the Surficial Legacy of past and Present Human Activities.” Anthropocene 2: 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2013.10.005.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lee, W.O. & Fouts, J. (Eds) 2005. Education for Social Citizenship. Perceptions from Teachers in the USA, Australia, England, Russia and China. Aberdeen, Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press.

- Lewis, S. L., and M. A. Maslin. 2015. “Defining the Anthropocene.” Nature 519 (7542): 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14258.

- Luciano, E. 2022. “Is ‘Anthropocene’ a Suitable Chronostratigraphical Term?” Anthropocene Science 1 (1): 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44177-022-00011-7.

- Madari, B. E., W. G. Sombroek, and W. I. Woods. 2004. “Research on Anthropogenic Dark Earth Soils. Could It Be a Solution for Sustainable Agricultural Development in the Amazon?.” In Amazonian Dark Earth: explorations in Space and Time, edited by, B. Glaser & W.I. Woods. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-05683-7_13.

- Miller, D. L. 2007. “The Seeds of Learning: Young Children Develop Important Skills through Their Gardening Activities at a Midwestern Early Education Program.” Applied Environmental Education & Communication 6 (1): 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/15330150701318828.

- Murakami, C. D. 2016. “Developing a Learning Garden on a Mid-Western Land Grant University.” In Learning, Food, and Sustainability edited by, L. Summer, (pp. 75–92). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-53904-5_5.

- Nasheeda, A., H. B. Abdullah, S. E. Krauss, and N. B. Ahmed. 2019. “Transforming Transcripts into Stories: A Multimethod Approach to Narrative Analysis.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 18: 160940691985679. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919856797.

- Robsen, S. 2006. Developing Thinking and Understanding in Young Children. London: Routledge.

- Rumpel, C., F. Amiraslani, C. Chenu, M. G. Cardenas, M. Kaonga, L.-S. Koutika, J. Ladha, et al. 2019. “The 4pl 000 Initiative: Opportunities, Limitations, and Challenges for Implementing Soil Organic Carbon Sequestration as a Sustainable Development Strategy.” Ambio 49 (1): 350–360. (https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-019-01165-2.

- Rashed, Rowaida. 2018. “Urban Agriculture: A Regenerative Urban Development Practice to Decrease the Ecological Footprints of Cities.” International Journal of Environmental Science & Sustainable Development 2 (2): 85–98. https://doi.org/10.21625/essd.v2i2.170.

- Rusinamhodzi, L. 2019. The Role of Ecosystem Services in Sustainable Food Systems. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/C2018-0-00522-8.

- Sageidet, B. M. 2012. “Inquiry-Baserte Naturfagaktiviteter i Barnehagen.” Læringskulturer i Barnehagen, edited by I T. Vist & M. Alvestad, (pp. 115–139). Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Shiel, R. 2012. “Science and Practice: The Ecology of Manure in Historical Retrospect.” In Manure Matters – Historical Archaeological and Ethnographic Perspectives, edited by R. Jones, (pp. 13–24). London: Routledge.

- Sjögren, H. 2020. “A Review of Research on the Anthropocene in Early Childhood Education.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 24 (1): 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949120981787.

- Svensson, L., G. Brulin, and P.-E. Ellström. 2015. “Interactive Research and Ongoing Evaluation as Joint Learning Processes.” In Sustainable Development in Organizations: Studies on Innovative Practices , edited by M. Elg, P.-E. Ellström, M. Klofsten, & M. Tillmar (pp. 346–361). Northamption: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- UNFPA. 2007. State of the World Population 2007: Unleashing the potential of urban growth, UN Population Fund. https://www.unwomen.org/en/docs/2007/1/state-of-the-world-population-2007

- United Nations. 2015. Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. United Nations (UN). Department of Economics and Social Affairs. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

- Vygotzky, L. S. 1986. Thought and Language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wild, A. 1993. Soils and the Environment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zalasiewicz, J., Waters, C. N. Williams, and N. Summerhayes. 2019. “History and Development of the Anthropocene as a Stratigraphic Concept.” In The Anthropocene as a Geological Time Unit, edited by J. Zalasiewicz, C.N. Waters, N. Williams, C.P. Summerhayes (pp. 1–40). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zech, W., P. Schad, and G. Hintermaier-Erhard. 2022. Soils of the world. Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-540-30461-6