Abstract

Children and young people today are growing up in an increasingly urban, technical, virtual and ecologically precarious world, leaving many feel disconnected from nature yet anxious about its degradation at the same time. Two distinct bodies of knowledge – namely youth human-nature relationships and youth eco-anxiety – are concerned with the former and the latter respectively. Through a narrative literature review, we bring these fields together and explore their interaction. We demonstrate that the dominant responses of facilitating nature exposure and encouraging environmental action risk counteracting each other and ultimately fail to address the root cause of children and young people’s experiences. We further show that emerging responses in both fields are overcoming these limitations by turning towards a reimagination of humanity’s relationship with nature, providing a holistic way forward. We conclude by discussing barriers restricting the expansion of such approaches and opportunities for future research to contribute to dismantling these barriers.

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS:

1. Introduction

The current epoch is often referred to as the Anthropocene, in recognition of the fact that the world’s ecological crises are deepening as a direct result of humanity’s relationship with nature (Lewis and Maslin Citation2015). Despite ongoing efforts to work towards globally agreed upon climate change mitigation and nature conservation targets, it seems increasingly unlikely that these targets will be met. In 2018, the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimated that the target to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels will be exceeded within the next three decades if current trajectories continue (IPCC Citation2018). Since then, these trajectories have continued, as illustrated by the ongoing gap between the required greenhouse gas emission reductions and those realised and promised by different countries around the world. In fact, even a complete realisation of all binding and non-binding commitments is projected to result in 2.4 °C of warming over the course of this century (UNEP Citation2022). Similarly, none of the 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets were met on a global level in 2020 (CBD Citation2020), and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) illustrates that current rates of biodiversity loss are projected to worsen in all future scenarios that do not include transformative change of the world’s social and economic systems (IPBES Citation2019). While both the IPCC (Citation2018) and the IPBES (Citation2019, 5) suggest that such a ‘fundamental, system-wide reorganisation across technological, economic and social factors, including paradigms, goals and values’ could still occur, neither find evidence that it is underway at this point in time.

In the ongoing absence of transformative change, the world’s ecological crises represent a ‘child and adolescent health emergency’ (Pinsky Citation2020, 16). Children and young people are particularly vulnerable to the impacts these crises have already, due to their comparatively weak physiological defence systems (Sanson, Hoorn, and Burke Citation2019) and their increasing awareness of the threats posed during a time in which they are developing ‘psychologically, physically, socially, and neurologically’ (Hickman et al. Citation2021, 864). This awareness often leads to eco-anxiety – a ‘chronic fear of environmental doom’ (Clayton et al. Citation2021, 71) – which is comparatively prevalent among younger generations (Patrick et al. Citation2023). At the same time, children and young people’s direct contact with nature is declining around the world, which can negatively affect their personal connectedness to nature, their efforts to protect it and their overall health and wellbeing (Bashan, Colléony, and Shwartz Citation2021; Liefländer et al. Citation2013). While this decline is predominantly attributed to global trends in urbanisation and technification (Edwards and Larson Citation2020; Gabrielsen and Harper Citation2017; Larson et al. Citation2019), it can also be a result of eco-anxiety induced nature avoidance (Hickman Citation2020; Ray Citation2020). In times of deepening ecological crises, children and young people’s contact with nature, connection to nature, environmental awareness, environmental action and personal wellbeing thus affect one another in complex ways.

Environmental education (EE) plays a key role in shaping each of these factors, and by extension, their interconnections. Here, it is useful to provide a definition of EE – a term that refers to diverse formal and informal educational activities that aim to achieve a ‘range of intended environmental and sustainability-related outcomes’ (Ardoin et al. Citation2022, 476). This diversity of educational activities is represented in the results of our literature review, which locates studies of formal EE interventions in schools at all levels, including analyses of school textbooks, and informal education via media such as films and children’s books. Several sources identify the key role that social media platforms play in many young people’s lives, including shaping their knowledge of and responses to ecological crises (Basch, Yalamanchili, and Fera Citation2021; Crandon et al. Citation2022; Gunasiri et al. Citation2022; Parry, McCarthy, and Clark Citation2022; Sternudd Citation2020). Parry, McCarthy, and Clark (Citation2022) study of young people’s digital engagements with climate change even found that they predominantly used social media to access news, including climate change issues, which demonstrates its growing importance as a source of information about ecological crises.

Overall, formal EE thus represents one of several important influences on children and young people’s awareness of their interrelationship with nature and its continuous degradation. For this reason, environmental educators carry a responsibility to communicate these matters with both urgency and care. To do so, it is essential that environmental educators understand children and young people’s experiences of growing up during a time of declining nature exposure and deepening ecological crises, as well as the ways in which they can provide effective support to their students. It was the desire to understand both that led to the formation of our interdisciplinary research team in 2022, which consists of ten environmental educators and researchers at the University of Adelaide.

Like caregivers and educators elsewhere (Baker, Clayton, and Bragg Citation2021; Jimenez and Moorhead Citation2021; Ray Citation2019), we noticed heightened levels of environmental concern among university students across our disciplines of social sciences, environmental science and public health, which seemed to be driven, at least in part, by their recognition of the unsustainability of humanity’s contemporary relationship with nature and their difficulties in imagining its transformation. To investigate these shared observations, we are currently conducting a quantitative study into the extent and distribution of eco-anxiety among university students and a qualitative study into their experiences of eco-anxiety, nature (dis)connection and the role of their formal education in this context. In this article, we present the literature review both of these studies are grounded in, through which we sought to gain insights into the full complexity of children and young people’s relationship with nature and its degradation. It draws on two distinct bodies of knowledge – namely youth human-nature relationships and youth eco-anxiety – that are concerned with the former and the latter respectively to investigate how these experiences are understood individually, how they are responded to individually, and how these components interact. Specifically, our review sought to answer the following research questions:

How do children and young people experience growing up in the current era?

How do children and young people’s experience interact with each other?

How do caretakers and educators respond to children and young people’s experiences?

How do caretakers and educators’ responses interact with each other?

How do children and young people’s experiences and caretakers and educators’ responses interact with each other?

To answer these questions, we provide an overview of established and emerging narratives in both fields, illustrate their interconnections and highlight important ways forward for EE practice, EE research and for the field of education more broadly.

2. Method

To draw out established and emerging narratives in both fields and investigate the ways in which they intersect, we conducted a narrative review of the relevant literature. The primary objectives of narrative reviews are the clarification of ‘what has been previously published’ on a specific topic and the identification of ‘new study areas not yet addressed’ (Ferrari Citation2015, 230). An important part of these objectives is to not only consider what is known about the topic in question, but also how it is commonly studied and interpreted (Greenhalgh, Thorne, and Malterud Citation2018). Narrative reviews can be used to analyse studies based on different research questions and methods (Pautasso Citation2020) and even to bring together ‘two fields of research that have not been crossed before’ (Amprazis and Papadopoulou Citation2020, 1066), which makes this method a particularly good fit for our review.

While narrative reviews draw on a wide variety of studies, they still begin with a structured literature search and selection process. Following Ferrari’s (Citation2015, 230) ‘best practice recommendations for the preparation of a narrative review’, our literature search and selection process was based on the clear definition of search terms, the strict application of inclusion criteria and the use of multiple databases. Due to our dual interest in children and young people’s experiences and the ways in which caretakers and educators respond to them, we began by identifying key search terms relating to children and young people and environmental education, as well as human-nature relationships or eco-anxiety, which are illustrated in .

Table 1. Search terms.

On this basis, we conducted comprehensive searches on both topics using the Scopus and Web of Science databases. For youth human-nature relationships, we used the terms associated with Children and Young People OR Environmental Education AND Human Nature Relationship, which yielded 87 results in Scopus, 79 results in Web of Science and a total of 110 results once duplicates were eliminated. For youth eco-anxiety, we used the terms associated with Children and Young People OR Environmental Education AND Eco-Anxiety, which yielded 59 results in Scopus, 68 results in Web of Science and a total of 80 results once duplicates were eliminated. As there was no overlap between the two topics, our initial searches resulted in a total of 190 sources.

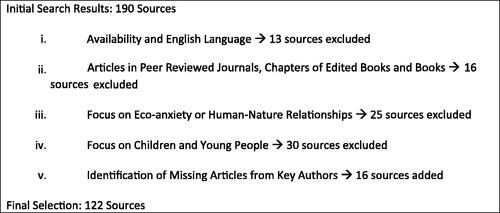

After eliminating those that were unavailable or written in languages other than English, we scanned the remaining sources in full to determine their suitability based on a set of inclusion criteria. Due to our interest in narratives, we included articles published in peer reviewed journals, book chapters and books. We included studies, reviews, essays and even commentaries, as long as they contained a clear point of view and did not just summarise other works. We further assessed whether each source actually focussed on children and young people’s eco-anxiety or human-nature relationships and excluded those that were not age or topic specific. Finally, we scanned the reference lists of all included sources and added an additional 16 sources. provides an overview of this process, which resulted in a final selection of 122 articles, book chapters and books on children and young people’s experiences, responses to their experiences or both.

Figure 1. Selection criteria and process.

The fields of youth nature disconnection and youth eco-anxiety are interdisciplinary, as illustrated by the fact that final selection of sources included in our review spans the disciplines of education, social sciences, psychology and health (see appendices 1 and 2). Rather than focussing exclusively on the education literature, we therefore took a similar approach to Pikhala (2020) by drawing out overarching narratives across disciplines in both fields and discussing their implications for environmental education and research. To do so, we proceeded to analyse all selected sources in depth. Firstly, five of us carefully read these sources and wrote annotations containing descriptions of their conceptualisations of youth nature disconnection or youth eco-anxiety, their recommendations for responding to these experiences, their approach for evaluating these experiences and/or responses, and their empirical findings and/or theoretical arguments, as well as critical reflections on their implications and the ways in which these points relate to each other (Basham, Radcliff, and Bryson Citation2023). These annotations were then collated and read by all team members in preparation for a workshop, during which we reflected on how children and young people’s experiences of nature disconnection and eco-anxiety are commonly perceived and addressed (Greenhalgh, Thorne, and Malterud Citation2018) and on the broader (in)consistencies within and across the fields of youth human-nature relationships and eco-anxiety (Ferrari Citation2015). On this basis, the first author led the coding of these annotations and wrote the first draft of this review, which was further refined through co-authors’ contributions and comments. Conducting a narrative review thus allowed us to not only identify dominant and emerging narratives in both fields, but to also reflect on the commonalities between them and on the implications of their dominance, or lack thereof, for how children and young people’s experiences are understood, communicated and responded to.

3. Results

The results of our analysis are presented in two parts. The first part illustrates how children and young people’s experiences of growing up in an urban and technological world interact with their knowledge of ecological crises, and how this interaction affects their wellbeing and their relationship with the natural world. On this basis, the second part provides an overview of dominant and emerging strategies aimed at strengthening these factors, evaluates their benefits and limitations and identifies potential ways forward.

3.1. Understanding young people’s experiences

Compared to older generations, children and young people today have less direct contact with nature and a greater awareness of its ongoing degradation. In this section, we illustrate their experiences of nature disconnection, eco-anxiety and ontological insecurity that arise from these circumstances, identify key factors that shape their extent and severity and draw attention to their interconnections.

3.1.1. Nature disconnection

As an interdisciplinary concept, diverse definitions exist for youth nature disconnection (Grimwood, Gordon, and Stevens Citation2018; Kawas et al. Citation2020), ranging from conceptualisations of children and young people’s lack of personal connectedness to nature to their lack of awareness of humanity’s interrelatedness with nature. Across the reviewed literature, the former was most common and thus provides our starting point here. Those who understand youth nature disconnection in this way usually attribute it to an ‘extinction of experience’ (Bashan, Colléony, and Shwartz Citation2021, 348; Colding et al. Citation2020, 3), which they attribute, in turn, to global trends of urbanisation and technification (Dornhoff et al. Citation2019; Freeman, Harris, and Loynes Citation2021; Grimwood, Gordon, and Stevens Citation2018). These trends simultaneously decrease the amount of time people spend outside (Hammond Citation2020; Zwierzchowska and Lupa Citation2021) and the quantity and quality of nature they are exposed when they are outside (Colding et al. Citation2020). Nature disconnection is a result of this physical loss of interaction between people and nature. It is characterised by both cognitive and emotional distance, with the former referring to limited ecological knowledge and the latter referring to apathy, dissatisfaction and a low sense of ‘community with nature’ (Askerlund et al. Citation2022; Bashan, Colléony, and Shwartz Citation2021; Hammond Citation2020, 44; Zwierzchowska and Lupa Citation2021). It can also be associated with an actual fear of nature (Hammond Citation2020), which then further deters physical contact (Prasad et al. Citation2022). In addition, nature disconnection is commonly perceived to be harmful for both people and nature (Bashan, Colléony, and Shwartz Citation2021; Charles and Louv Citation2020; Meltzer et al. Citation2020; Reese Citation2018). However, this relationship is becoming increasingly complex with ongoing environmental degradation.

The possibility that children and young people today are less exposed and less connected to nature compared to older generations is a frequently raised concern (Colding et al. Citation2020; Colding and Barthel Citation2017; Kawas et al. Citation2020; Reese Citation2018). Evidence from around the world provides some backing for this concern, as children and young people’s exposure to nature is considerably lower than that of their parents when they were young (Charles and Louv Citation2020) and even that of children and young people ten years ago (Colding et al. Citation2020). Moreover, Dasgupta et al. (Citation2022) find that older adults in Tokyo feel greater attachment to urban green spaces in their neighbourhood compared to young adults. Similarly, Bauer, Wallner, and Hunziker (Citation2009) find that older adults in Switzerland are more likely to emphasise the utilitarian value of nature while feeling emotional closeness to it, whereas younger adults are more likely to emphasise the intrinsic value of nature while feeling emotional distance from it. The importance of nature is therefore more abstract to young people in this case, which supports Louv’s (Citation2009, 2) claim that ‘students today are aware of global threats to the environment but hardly notice what’s happening on a more personal scale’. In contrast, Nisbet, Zelenski, and Murphy (Citation2011) found no difference in the nature relatedness of university students and professionals in Canada and Li and Lang (Citation2015) found that Chinese adolescents’ pro-environmental attitudes are stronger than those of their parents. However, as this study specifically focussed on students attending a green school, it is unclear whether their comparatively strong pro-environmental attitudes were a result of their green school education or indicative of their wider generation. Either way, children and young people’s concern for nature simply appears to be different to that of older generations, but not necessarily lower, despite their comparatively limited direct exposure and personal connection to nature.

Intragenerational differences in children and young people’s perceptions of and interactions with nature provide further insights into the nuances of their connection to nature. On the one hand, several studies provide evidence that urbanisation and technification reduce children and young people’s nature exposure and connectedness. Both are lower, for instance, among university students with smartphone addictions (Gao et al. Citation2022) and among those enrolled in non-environmental degrees (Nisbet, Zelenski, and Murphy Citation2011). They are also lower among children growing up in urban areas (Collado, Íñiguez-Rueda, and Corraliza Citation2016; Kim, Vaswani, and Lee Citation2017; Moula, Walshe, and Lee Citation2021; Tomasso et al. Citation2022) and industrialised societies (Barragan-Jason et al. Citation2022) and among children whose notions of self and home are more connected to cities and less connected to nature (Giusti Citation2019). Dornhoff et al. (Citation2019, 3) further find that young people in Ecuador are more connected to nature than young people in Germany, which they attribute to differences in their exposure, as the former ‘live in a biodiversity hotspot’, while the latter live in ‘one of the most industrialised countries in the world’. On the other hand, Dornhoff et al. (Citation2019, 7) also find slightly higher ‘altruistic environmental concern’ among young people in Germany, which implies that such concern depends not only on nature exposure and connection. Li and Ernst (Citation2015) identification of cultural differences in children’s environmental value orientations in the US and China that cannot be explained by differences in exposure supports this conclusion. Moreover, Hatala et al. (Citation2019, 125) illustrate that urban Indigenous young people in Canada engage in meaning-making which ‘minimises’ the ‘distance between the land out there and the land here in the city’, which implies that urbanisation does not always lead to disconnection from nature. Even though urbanisation and technification can decrease children and young people’s nature exposure and connectedness, this impact thus appears to be neither universal across all contexts, nor always connected to a lack of environmental concern.

Despite these complexities, the potential of children and young people’s nature disconnection to drive unsustainable behaviour continues to be a frequently cited reason for addressing it (Colding et al. Citation2020; Grimwood, Gordon, and Stevens Citation2018). This potential is seen as particularly concerning because of the stability of nature disconnection later in life, as it ‘may trigger baseline shifts in collectively shared environmental attitudes’ of entire generations (Colding and Barthel Citation2017, 98) and therefore contribute to the worsening of the climate and biodiversity crises (Eastwood et al. Citation2021; Gao et al. Citation2022; Hammond Citation2020; Liefländer et al. Citation2013). The second pervasive reason for addressing children and young people’s nature disconnection is its potential to harm their health and wellbeing (Kellert Citation2008; Maller, Henderson-Wilson, and Townsend Citation2009; Moula, Walshe, and Lee Citation2021; Tomasso et al. Citation2022). In this context, Louv’s (Citation2009, 2) ‘Nature Deficit Disorder’ is particularly influential, which is ‘not a medical diagnosis’, but ‘a description of the growing gap between human beings and nature’ and its negative implications for children and young people’s physical health, mental health, readiness to learn and overall ‘sense of wonder’. In fact, studies not only show that children ‘tend to be smarter, more cooperative, happier and healthier’ if they have ‘frequent and varied opportunities’ to engage with nature (Charles and Louv Citation2020, 403), but also that this exposure, and the connection it results in, improve their immediate wellbeing (Nisbet, Zelenski, and Murphy Citation2011) and their quality of life throughout adulthood (Rosa et al. Citation2019). At the same time, however, emerging eco-anxiety research also shows that the ‘gradual environmental degradation is particularly damaging to the wellbeing of children in communities with deep cultural or working ties to the land’ (Chalupka, Anderko, and Pennea Citation2020, 13), which implies that nature connection may lose its benefits as the world’s ecological crises deepen. Understanding how children and young people’s awareness of these crises interacts with their nature connection is therefore important, as both have implications for their wellbeing and the actions they take, and thus for the health of people and the planet.

3.1.2. Eco-anxiety

While there is no universal definition of eco-anxiety, it is commonly referred to as the ‘chronic fear of environmental doom’ (Clayton et al. Citation2021, 71) that is associated with threats ‘posed by the climate and biodiversity crisis’ (Hickman Citation2020, 414). It has ‘affective, cognitive, and behavioural dimensions’ (Hickman et al. Citation2021, 864) and can relate to threats in the near or far future that ecological crises pose to oneself, future generations or the natural world (Crandon et al. Citation2022). In addition to direct experiences or knowledge of these threats, children and young people’s eco-anxiety is further fuelled by the insufficient societal and political responses to them (Bright and Eames Citation2020; Hickman et al. Citation2021; Thompson et al. Citation2022; Wortzel et al. Citation2022a) and their own inability to influence these responses (Kelly et al. Citation2022). Studies written by young people emphasise the combination of guilt and frustration they feel because of these limitations (Diffey et al. Citation2022), as well as the sense of betrayal they feel when they witness the ‘political nonchalance’ and the ‘eco-gaslighting’ that occurs at climate summits (Uchendu Citation2022, 546). Youth eco-anxiety is therefore not only associated with fear, but also with anger, annoyance, hopelessness, sadness, sorrow, grief, responsibility, guilt and shame (Diffey et al. Citation2022; Gislason, Kennedy, and Witham Citation2021; Léger-Goodes et al. Citation2022; Ojala Citation2019; Pikhala 2020; Thompson et al. Citation2022). It is an ‘umbrella term’ that broadly refers to these ‘various forms of distress’ (Senay et al. Citation2022), which children and young people experience based on the existing and anticipated impacts of global ecological crises, the insufficient action that is taken to prevent these impacts and the limitations of their own agency in this space.

As the world’s ecological crises are projected to worsen over time, it is neither surprising that eco-anxiety is prevalent among children and young people globally, nor that their experiences differ from those of older generations. Hickman et al. (Citation2021) global survey on youth climate anxiety, which spans ten countries on five continents, reveals that 84% of young people at least moderately worried about climate change, with 32 and 27% of them even being very and extremely worried respectively. Sciberras and Fernando (Citation2022) reveal a similar prevalence among Australian teenagers throughout their adolescence, with over 70% experiencing either increasing or persistently moderate to high climate anxiety. Intergenerational comparisons illustrate that young people’s eco-anxiety is not only disproportionately high (Patrick et al. Citation2023; Whitmarsh et al. Citation2022), it is also tied to fundamental concerns about starvation, displacement and death as a result of climate change and natural resource depletion, which differ from older generations’ concerns about rising costs (Barchielli et al. Citation2022). Qualitative studies further illustrate that young people perceive their parents’ and teachers’ generation to be less concerned and less inclined to act even though they are more responsible and able to do so (Jones and Davison Citation2021). They reinforce that eco-anxiety is prevalent among children (Jones and Whitehouse Citation2021), as well as adolescents (Thompson et al. Citation2022) and young adults (Helm, Kemper, and White Citation2021), and that it is ‘severe more often than mild’ (Hickman Citation2020, 419). It is featured prominently in the social media content young people produce (Basch, Yalamanchili, and Fera Citation2021; Sternudd Citation2020) and is increasingly noticed by caregivers and educators (Baker, Clayton, and Bragg Citation2021; Jimenez and Moorhead Citation2021; Mellor et al. Citation2022; Verlie et al. Citation2020), all of which provides additional evidence for its overall pervasiveness.

Despite this pervasiveness, children and young people are ‘not a homogenous group’ and they experience eco-anxiety in different ways (Ojala Citation2019, 11). Hickman et al. (Citation2021) illustrate that high to extreme climate anxiety is especially prevalent among young people in the Philippines, followed by India, and least prevalent among young people in Finland, the UK and the US, which implies that it is connected place-specific exposure to climate related impacts and/or differences in young people’s perceived agency. Uchendu (Citation2022, 546) – a youth climate activist from Nigeria – argues that climate anxiety is closely connected to uneven distributions of power, vulnerability, and risk, which affects her experiences and those of fellow young people in the Global South. At the same time, however, she also argues that youth climate activists everywhere are ‘passionate about a healthier planet’, even if they are ‘acutely impacted by this unjust reality in different ways’. Diffey et al. (Citation2022, 501) – a group of concerned young people from 15 countries across the Global North and Global South – make a similar point. While they mention minor differences in the severity of their climate anxiety and the specific, place-based impacts they are most concerned about, they state that there are ‘no major differences’ in their ‘deeply uncomfortable feelings’ of ‘worry, sorrow, grief, fear, anger, hopelessness and responsibility’. Ojala (Citation2019, 13) further claims that eco-anxiety exists among those who are most vulnerable to the impacts of the world’s ecological crises, but also among those who are ‘often seen as responsible’ for them. For the latter, their eco-anxiety is ‘not foremost related to self-focused worry but rather to concern about the wellbeing of others’ and ‘mixed up with guilt’ regarding their own role in perpetuating the threats to this wellbeing. While research investigating youth eco-anxiety in the Global South remains limited (Aruta Citation2022; Aruta and Simon Citation2022), emerging comparisons thus suggest that its severity and nature varies around the world.

Children and young people’s experiences of eco-anxiety also vary locally based on several factors. It tends to be more common and more severe among girls and young women (Boluda-Verdú et al. Citation2022; Léger-Goodes et al. Citation2022), and among those who are already experiencing ecological and non-ecological stressors (Patrick et al. Citation2023; Simon, Pakingan, and Aruta Citation2022). Heightened eco-anxiety further coincides with significant life situations, such as having children (Pikhala 2020), and clinical mental health disorders, such as Major Depressive Disorder and Generalized Anxiety Disorder (Bhullar et al. Citation2022; Schwartz et al. Citation2022; Senay et al. Citation2022; Whitmarsh et al. Citation2022). While it is mostly unclear whether eco-anxiety is a cause or a consequence of clinical mental health disorders, Sciberras and Fernando (Citation2022) longitudinal study finds no evidence of increasing general mental health symptoms as a result of increasing eco-anxiety among Australian adolescents at this point in time. Moreover, while nature exposure and connection can reduce general anxiety, they do not have this effect on eco-anxiety (Whitmarsh et al. Citation2022), as they increase the sense of loss that is associated with existing and future impacts of climate change, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation (Crandon et al. Citation2022; Léger-Goodes et al. Citation2022). Together, these global and local intragenerational differences of youth eco-anxiety clearly indicate that it has the potential to exacerbate existing threats to children and young people’s overall wellbeing, as well as existing inequalities between them.

This potentiality forms a big part of the reason why it is important to respond to youth eco-anxiety, which is not as straightforward as it may seem. In itself, eco-anxiety is ‘a rational response to a real, major and global threat’ and thus not pathological (Crandon et al. Citation2022, 123; Hurley, Dalglish, and Sacks Citation2022). In fact, it often manifests as ‘practical anxiety’, which links the encounter of a problem with the desire to solve it (Pikhala 2020, 11). For this reason, Hickman (Citation2020, 422) argues that it should not be treated as ‘a problem that needs to be fixed’, Bright and Eames (Citation2020, 15) make the case for reframing eco-anxiety as eco-empathy to represent it as an ‘emotionally congruent and healthy response’ and Sternudd (Citation2020, 166, 168) warns against the use of ‘medicalising terminology’ that emphasises ‘individual recovery instead of activities that will result in change’. He further claims that change has historically been driven by ‘wrath and feelings of injustice – not hope’, which implies that mitigating children and young people’s eco-anxiety may reduce their efforts to bring about change. A similar perspective is reflected in Löfström, Klöckner, and Nesvold (Citation2020, Löfström, Richter, and Nesvold Citation2021) ‘Nature in Your Face’ methodology, which uses images of plastic pollution to trigger ‘negative emotions like fear and anger’ in children in the hopes that they will function as ‘catalysts for climate action’. As long as youth eco-anxiety is not too overwhelming, these authors perceive it to be a desirable condition in light of the urgent need for action.

However, even failing to respond to youth eco-anxiety without actively triggering it can make it become ‘too intense’ and ‘overwhelming’ (Hickman et al. Citation2021, e863) and turn it into a source of chronic stress during childhood and adolescence that can have negative repercussions for their health and wellbeing later in life (Wu, Snell, and Samji Citation2020). Without attending to the affect of learning about the world’s ecological crises, there is a genuine risk that students will ‘leave college not as the well-trained, problem-solving leaders’ that programs promise, but ‘deflated, aimless, angry, or apathetic’ (Ray Citation2019, 302), which may even end up preventing them from taking action. Considering that children and young people are simultaneously the most anxious and least responsible generation regarding the current trajectories of these crises, failing to help them manage their eco-anxiety for the sake of the planet seems not only futile, but also unfair and actively harmful. Yet helping them manage their eco-anxiety must be undertaken with the aim of helping them to sustain action, not accept inaction. It must allow children and young people – and society more broadly – to ‘bounce elsewhere’ rather than ‘bounce back’ to the status quo (Verlie Citation2021, 133). It must further be actively supported by action taken by all generations, especially those in positions of power. In reference to Greta Thunberg, Kouppanou (Citation2020, 956) points out that ‘the problem is that those with the greater potentiality of agency do not listen. This is the cause of her anxiety’. Hence, ‘we need to…wonder if children’s political agency should be solicited or if adult human beings should take on their responsibilities’.

3.1.3. Ontological insecurity

In addition to children and young people’s inability to shape the global response to world’s ecological crises, a small number of studies implicitly suggest that their eco-anxiety is further fuelled by their inability to imagine how these crises can be managed at all. Children with severe eco-anxiety, for instance, are certain ‘the climate crisis will lead to social collapse’ and do not believe that anything can be done to prevent this outcome (Hickman Citation2020, 418). Adolescents in the UK share this ‘general sense of impending doom’, which is not only connected to their observations of political inaction and unsustainable social structures, but also to their own sense of helplessness, especially in the context of climate change, as they do ‘not know what to do to prevent it’ (Thompson et al. Citation2022, 7). University students in the US, too, often express ‘a sense of fatalism’, which is connected to the restrictions their ‘commitment to their current frames of reference’ place on their ability to imagine alternative futures (Skilling et al. Citation2022, 665, 668). Simultaneously learning about the insufficiency of taking individual action and the limited institutional and systemic change that is occurring not only shakes students’ ‘epistemological foundations and emotional armour’, but also makes it easier for them to imagine the ‘apocalypse’ than to imagine ‘society transitioning away from carbon’ (Ray Citation2019, 303, 310). In fact, when explicitly asked to visualise an ‘ideal future state’, they were unable to form any ‘mental image of the path ahead, much less a future that they could thrive in’ (Ray Citation2020, 2).

This inability to imagine a departure from current trajectories is also reflected in young adults’ struggle to make life-plans due to their ‘growing lack of faith in the future of Western societies’ (Jones and Davison Citation2021, 198), as well as their decisions to remain childfree. These increasingly common decisions are simultaneously underpinned by a sense of personal responsibility to not worsen the problem, as well as a sense of doubt that personal ‘small actions’ can actually have a meaningful impact on the planet (Helm, Kemper, and White Citation2021, 121). In this context, Nairn (Citation2019, 441) argues that the ‘end of the world’ discourse among young people ‘can also be understood as an ‘end of life’ discourse’, as represented in decisions not to bring new life into an ‘unfixable’ world. Collectively, these examples illustrate that children and young people growing up within the dominant social and economic system recognise its unsustainability, but still frequently internalise the individualisation of responsibility that is characteristic of it. While they know that human existence cannot continue in its current form, they do not know what other forms it could take, which lends itself to the conclusion that it cannot continue at all.

In this way, the world’s ecological crises can trigger ‘existential concerns’ (Benoit, Thomas, and Martin Citation2022, 53), ‘existential uncertainty’ (Skilling et al. Citation2022, 676) or an ‘existential crisis’ (Ray Citation2019, 300), as the continuity of oneself, society and humanity are no longer taken for granted. For children and young people who are simultaneously threatened by these crises and complicit in the systems that drive them, these existential concerns derive from the disruption of the ‘sense of security’ that ‘global histories of imperialism’ have afforded them (Verlie Citation2021, 7). Though the term is rarely used in the context of eco-anxiety, this conscious engagement with fundamental existential questions and lack of trust in the ‘constancy’ of one’s ‘social and material environment’ is a form of ontological insecurity. It is the ‘result of critical situations, circumstances of radical and unpredictable disjuncture’ (Ejdus Citation2018, 886, 887) that ‘threaten or destroy the certitudes of institutionalised routines’ (Giddens Citation1984, 61). There is no question that human-induced climate change represents a profound global moment of ontological disjuncture. It threatens children and young people’s existence, disrupts the paradigm of their civilization and demands a fundamental rethink of humanity’s relationship with nature. Drawing attention to this dimension of eco-anxiety is essential, as it clearly illustrates that children and young people growing up in anthropocentric societies not only require more opportunities to be heard, but also more opportunities to experience alternative ways of knowing, doing and being.

3.2. Responding to young people’s experiences

Children and young people today feel increasingly disconnected from nature but are increasingly aware of threats its ongoing degradation poses. Together, these factors affect their interactions with nature and their overall wellbeing in complex ways. In this section, we provide an overview of dominant and emerging avenues of support that are available to them, which include attempts to foster nature connection, encourage environmental action and build ontological reflexivity, and evaluate their benefits and limitations.

3.2.1. Fostering nature connection

Despite the complex interconnections between children and young people’s nature connection and their eco-anxiety, fostering nature connection is still widely considered to be important for their overall health and wellbeing and their interest in leading sustainable lives. In this context, the greatest emphasis is put on increasing children and young people’s exposure to nature, which involves greening the environments they encounter on a daily basis in their neighbourhoods (Giusti et al. Citation2017; Kellert Citation2008) and schools (Askerlund et al. Citation2022; To and Grierson Citation2020; Zwierzchowska and Lupa Citation2021), and creating opportunities that increase the time they spend outside (D’Amore Citation2018; Eastwood et al. Citation2021; Giusti et al. Citation2017; Hammond Citation2020; Meltzer et al. Citation2020; Zwierzchowska and Lupa Citation2021). A secondary emphasis is put on facilitating forms of engagement that build nature connection most reliably, such as activities that involve immersive and unstructured interaction (Hill Citation2013; Kelly et al. Citation2022; Rosa et al. Citation2019) as well as tactile and aesthetic experiences (Tsevreni Citation2022), and that build nature familiarity, self-efficacy and agency (Prasad et al. Citation2022; Reese Citation2018). Overall, fostering nature connection thus involves increasing the quantity and quality of people’s interactions with nature, which is thought to be particularly important at a young age.

The most useful settings for advancing children and young people’s engagement with nature are the ones in which they spend most of their time. They include their schools, families and communities (Charles and Louv Citation2020), as well as cyberspace, although the benefits and costs of the latter are contested (Colding et al. Citation2020; Gao et al. Citation2022; Hawley Citation2022; Kawas et al. Citation2020). Across all of these settings, opportunities created through EE have been studied most extensively. Examples that are part of children and young people’s formal education range from the installation of bird feeders and insect hotels on school grounds to the inclusion of activities like nature observation, gardening, recycling and composting in lessons (Askerlund et al. Citation2022; Gugssa, Aasetre, and Debele Citation2021; Louv Citation2009; Maller, Henderson-Wilson, and Townsend Citation2009; Reese Citation2018). They further include school-based conservation programs, which involve environmental monitoring and the protection of endangered species (Giusti Citation2019; Maller, Henderson-Wilson, and Townsend Citation2009), as well as various forms of outdoor education. The latter range from eco-art programs centred around creative engagement with nature (Huhmarniemi, Jokela, and Hiltunen Citation2021; Raatikainen et al. Citation2020; Tsevreni Citation2022) to field trips centred around environmental challenges and solutions (Payne Citation2015; Raatikainen et al. Citation2020) to school camps centred around physical activities in nature over an extended period of time (Hill Citation2013; Liefländer et al. Citation2013; Meltzer et al. Citation2020). Similar informal EE opportunities also exist in the form of after school programs (Grimwood, Gordon, and Stevens Citation2018), weekend field trips (D’Amore 2018; Louv Citation2009) and summer camps (Tomasso et al. Citation2022), which are supported by organisations raising awareness on how to ‘Leave No Trace’ while undertaking them (Loynes Citation2018, 180).

Studies that investigate the outcomes of these diverse opportunities almost always find them to be successful in increasing children and young people’s connection to nature. Swedish children participating in arts in nature fieldtrips, for instance, developed greater respect for nature (Raatikainen et al. Citation2020) and those participating in a yearlong salamander conservation program developed empathy and concern for salamanders, as well as other animals and nature in general during this time (Giusti Citation2019). Teachers running lessons involving gardening and wildlife observation in other Swedish schools observed similar changes in their students, who not only became less afraid of insects over time, but also started acting kinder towards them (Askerlund et al. Citation2022). Instructors of urban outdoor education programs in Canada even observed empathy towards wasps after a child had been stung and felt like their program successfully builds nature awareness and connection, as well as overall confidence, in all participating children and adolescents (Grimwood, Gordon, and Stevens Citation2018). Such an increase in confidence was also experienced by young people participating in a video project involving local green spaces in the UK (Eastwood et al. Citation2021) and observed in children participating in nature-based activities at urban primary schools in Australia (Maller, Henderson-Wilson, and Townsend Citation2009) and in nature clubs in the US (D’Amore 2018). Moreover, university students enrolled in EE courses in Canada maintained their nature relatedness levels throughout the winter semester (Nisbet, Zelenski, and Murphy Citation2011), those participating in a semester long eco-art course in Greece developed greater empathy for non-human species (Tseverni 2022) and those participating in a three-week outdoor orientation program in the US increased their ‘innate tendency to affiliate with life and lifelike processes’ (Meltzer et al. Citation2020, 209).

Despite these immediate benefits, however, much less is known about longer term effects. On the one hand, participation in the yearlong salamander project still shaped children’s nature connection two years later (Giusti Citation2019) and repeated participation in nature-based camps had an ongoing effect on young people’s biophilic expression in the US (Meltzer et al. Citation2020). On the other hand, only children, but not adolescents, participating in a four-day nature-based school camp in Germany still felt closer to nature four weeks later (Liefländer et al. Citation2013). Outside of these examples, systematic reviews highlight that follow up studies measuring the long-term outcomes of efforts to foster youth nature connection – and EE more broadly – remain rare (Ardoin et al. Citation2018; Stern, Powell, and Hill Citation2014). Whether their effectiveness is maintained over time is therefore much more uncertain, which also applies to their associated benefits for people and nature.

In fact, even if children and young people’s nature connection can successfully be strengthened and maintained throughout their lives, it is questionable whether it is enough to maintain its associated benefits. Several critiques of contemporary efforts to foster nature connection argue that these efforts are still underpinned by an ‘anthropocentric view of nature’ (Colding et al. Citation2020, 4) and fail to question the ‘power differentials’ within this view ‘to any meaningful extent’ (Ärlemalm-Hagsér Citation2013, 27). The same institutions that aim to expose children and young people to nature also expose them to pedagogies that are underpinned by human-nature hierarchies (Dreamson and Kim Citation2022; Payne Citation2015), curriculum content that provides ‘readymade solutions and actions’ for a sustainable life (Ärlemalm-Hagsér Citation2013, 37-38) and textbooks that emphasise human control over nature (Lemoni, Stamou, and Stamou Citation2011, Lemoni et al. Citation2013; Zahoor and Janjua Citation2020). Moreover, even nature engagement programs themselves frequently reinforce a utilitarian view of nature by strengthening students’ beliefs in human ingenuity to overcome environmental challenges (Sidiropoulos Citation2018), by failing to consider the environmental costs associated with the required materials, equipment and travel (Huhmarniemi, Jokela, and Hiltunen Citation2021; Loynes Citation2018) and by putting too much of an emphasis on adventure and personal development in wilderness settings ‘out there’ rather than ‘at home’ (Hill Citation2013, 26; Hill and Brown Citation2014). Not only is the accessibility of such wilderness settings – which are typically associated with remote and pristine places – unequally distributed (Loynes Citation2018), even those who have the privilege to connect with them may not extend this connection to the more mundane and modified environments they encounter in their everyday lives (Hill Citation2013). In fact, the wilderness concept itself problematically contains a conceptualisation of nature as something that is ‘other than human’ and spatially distant (Loynes Citation2018, 180), which reinforces, rather than dismantles, the human nature binary.

Such nature engagement programs fall into the category of ‘weak sustainability’, which refers to ‘environmental movements that preserve the social and economic relations that cause and perpetuate environmental problems’ (Dickinson Citation2013, 326, 328). Collectively, these critiques imply that strengthening children and young people’s personal connection to nature does not automatically transform their understanding of humanity’s relationship with nature, and that achieving former without the latter is insufficient to alter the trajectories of the world’s ecological crises. While fostering personal nature connection is beneficial for people and nature in the short term, it is therefore insufficient to maintain these benefits long term and must be accompanied by fundamental transformations in how humanity, nature and their interconnectedness are understood.

3.2.2. Encouraging environmental action

Environmental action is not only one of the main desired outcomes of fostering children and young people’s nature connection, but also the most widely recommended strategy for managing their eco-anxiety. In fact, even when other strategies are discussed, such as utilising creative avenues for expressing their experiences (Lehtonen and Pikhala 2021; Moula, Palmer, and Walshe Citation2022), ‘almost all eco-anxiety scholars’ also advocate for encouraging individual and/or collective environmental action as part of the solution (Gallay et al. Citation2022, 40). Its popularity is not surprising, as it simultaneously addresses the threats posed by the world’s ecological crises, the insufficient action that is taken to mitigate these threats and the restricted ability of children and young people to influence this action, at least to a certain extent.

As a result of this predominance, considerable interest exists in different avenues through which children and young people can learn about and identify opportunities for taking action. By far the strongest emphasis is put on the role that formal education can play in this space, as it has the potential to ‘reach a substantial proportion of young people’ due to mandatory school attendance (Eichinger et al. Citation2022) and is one of their main sources of information about climate change, biodiversity loss and environmental degradation (Thompson et al. Citation2022). This information, however, can trigger eco-anxiety (Jones and Whitehouse Citation2021; Thompson et al. Citation2022), which is why environmental educators actively combine it with information on what children and young people can do about these crises (Acton and Saxe Citation2020; Crandon et al. Citation2022; Léger-Goodes et al. Citation2022) and what others are doing about them (Ojala Citation2019; Wortzel et al. Citation2022b). Even though educators around the world also raise concerns that the opportunities they can create are limited by their institutions and the broader education systems within which they work (Baker, Clayton, and Bragg Citation2021; Eichinger et al. Citation2022; Jimenez and Moorhead Citation2021), it is clear that they are actively trying to offset youth eco-anxiety by facilitating individual pro-environmental behaviour, collective pro-environmental action or both.

Specifically, individual pro-environmental behaviour can be encouraged by raising children and young people’s awareness of their ecological footprints (Skilling et al. Citation2022), by highlighting the benefits of personal lifestyle choices such as recycling, saving energy, dietary changes, using public transport and riding bikes (Bandura and Cherry Citation2020; Schwartz et al. Citation2022; Wild and Woodward Citation2021) and by creating opportunities to take some of these actions in their classrooms (Acton and Saxe Citation2020). Studies that measure the effects of taking such actions show that it helps children and young people relieve the cognitive dissonance between their values and actions (Skilling et al. Citation2022) and feel like they are ‘heard’, ‘part of the solution’ and ‘capable of making a difference’ (Gunasiri et al. Citation2022). Parry, McCarthy, and Clark (Citation2022, 34) even illustrate that some young people are actively calling for more ‘positive stories’ and ‘practical small things’ individuals can do to help mitigate climate change as a way to reduce their ‘feelings of helplessness’, which implies that even individual pro-environmental behaviour can reduce youth eco-anxiety, at least in the short term.

Whether these benefits of individual pro-environmental behaviour can be maintained in the long term is yet to be measured directly, but it is already contested. In contrast to those asking for guides to practical action, other young people are becoming increasingly critical of the promotion of ‘individual change’, arguing that it often functions to negate the urgent need for ‘systemic change’ (Bright and Eames Citation2020, 22). Making a similar point, Cairns (Citation2021, 525) argues that ‘well-intentioned efforts to generate good feelings through individual impact’ unfairly shift the responsibility for addressing the problem to ‘the very communities that have been subject to harm’. Moreover, several scholars caution that children and young people’s motivation to act can quickly turn to disillusionment and despair when they apprehend the ‘relative insignificance of their actions’ (Skilling et al. Citation2022, 666), witness the lack of action taken by ‘powerful organisations, governments and institutions’ (Hickman Citation2020, 415) and realise that the world’s ecological crises continue to worsen despite decades of personal sacrifice (Boluda-Verdú et al. Citation2022; Léger-Goodes et al. Citation2022). While providing students with the ‘prescriptive solutions’ they desire may boost their mood temporarily, they are unlikely to sustain environmental action in the long run (Ray Citation2019, 309), thus limiting their benefits for personal and planetary wellbeing.

The encouragement of collective pro-environmental action tends to be seen as superior in both regards. Examples include collective lifestyle choices, such as organising local energy audits and clothes swap events, promoting ‘meatless Mondays’, and managing joined tool libraries and community gardens (Acton and Saxe Citation2020; Gallay et al. Citation2022), as well as collective activism (Baker, Clayton, and Bragg Citation2021; Gislason, Kennedy, and Witham Citation2021; Gunasiri et al. Citation2022; MacKay, Parlee, and Karsgaard Citation2020; Schwartz et al. Citation2022). Educators can ‘empower youth to be politically active’ (Bright and Eames Citation2020, 22) by teaching ‘mechanisms of political change’ (Jones and Davison Citation2021, 195), but also by emphasising that ‘spectacular, triumphant moments are only the result of the invisible work of a lot of faceless idealists’ (Ray Citation2019, 311). Understanding the latter is essential to give children and young people a ‘sense of proportionate and shared responsibility’, which reinforces their ability to maintain action and the benefits they derive from it (Skilling et al. Citation2022, 674; Thompson et al. Citation2022). Engaging in local civic science projects, for instance, not only increased young people’s ‘agency and efficacy’ but also built solidarity among them, which helped them ‘share a sense of hope that their collective work can make a difference’ (Gallay et al. Citation2022, 44). Similarly, participating in COP24 built the same sense of ‘hope’, ‘efficacy’ and ‘being heard’ among members of an Indigenous youth group (MacKay, Parlee, and Karsgaard Citation2020, 14), and participating in climate strikes showed youth activists that ‘many other people’ were ‘just as passionate’ as them (Bright and Eames Citation2020, 20). Working together and witnessing the successful actions of others around the world are important, as both can build a sense of collective efficacy that far exceeds their sense of self-efficacy, which counteracts feelings of despondency and motivates children and young people to sustain action (Bandura and Cherry Citation2020). Consequently, it is not surprising that Schwartz et al. (Citation2022) direct comparison shows that collective pro-environmental action functions as an eco-anxiety buffer, while individual pro-environmental behaviour only lowers general anxiety levels.

Yet even encouraging collective action has its drawbacks. While it is less individualising, it still often involves a ‘transference of guilt onto climate activists’, which negatively affects their health and wellbeing over time (Nairn Citation2019, 442). In fact, Ojala (Citation2019, 13) argues that ‘problem-focussed coping’ can be counterproductive and actually increase children and young people’s distress ‘when stressors are relatively uncontrollable’. A recent article written by young people themselves shows that their activism already has this effect, as they ‘struggle with burnout’ and ‘vicarious trauma’ as they try to ‘overcome other people’s neglect of the climate crisis by working extremely hard’ themselves. They further describe the guilt they feel for their own ecological footprints, even though they acknowledge that broader ‘structures and systems’ make ‘ethical choices’, such as only working for perfectly sustainable employers, ‘extremely difficult’. Instead of calling for more opportunities for taking action themselves – collective or otherwise – they thus call for more political action and more intergenerational collaboration (Diffey et al. Citation2022, 502). These insights support Hickman et al. (Citation2021, e871) conclusion that supporting children and young people’s wellbeing in the long term requires ‘recognising, understanding, and validating’ their experiences, as well as ‘placing them at the centre of policy making’. When encouraging any form of youth action, it is thus important to stress that the responsibility does not lie solely on children and young people’s shoulders and to advocate for giving them a greater voice in places that matter and for more fundamental political and economic action on societal scales at the same time.

3.2.3. Building ontological reflexivity

While being heard and being able to influence the global response to the world’s ecological crises would likely help children and young people manage their eco-anxiety, it will only do so successfully if they believe that meaningful action can be taken and that the harmonious co-existence of people and nature is possible. Their hope thus needs to be grounded not only in an ‘empowerment to act’, but also in a clear ‘vision for change’ (Mercer Citation2022, 10). Diffey et al. (Citation2022, 506) articulate such a vision in their call for ‘a radically more compassionate world’ that is ‘built on systems that value the protection of people and the rest of the natural world, now and in the future’. However, children and young people’s experiences of ontological insecurity described previously indicate that not all share this vision, or believe in its possibility, as they cannot imagine a future for life at all. In recognition of those who require a ‘more concrete way to find climate hope’ (Ojala Citation2019, 13), several scholars in the fields of eco-anxiety and human-nature relationships are beginning to explore different avenues of helping children and young people recognise and challenge their subconscious assumptions about human existence and the forms that it can and cannot take. We refer to this capacity as ontological reflexivity.

These explorations consist of diverse investigations into when and how children and young people form these assumptions and whether it is possible to undo them. Marin et al. (Citation2017, 47) illustrate that children in anthropocentric cultures slowly adopt ‘human-centred perspectives’ between the ages of three and five, but that they are still able to ‘take different perspectives’ if they are exposed to those in books and movies. On this basis, they conclude that ‘anthropocentrism is a learned cultural model’ in certain societies and that cultural artefacts and practices can increase or decrease its salience. Taylor (Citation2017, 1456) further argues that young children often ignore ‘onto-epistemological boundaries that divide the world into humans and the rest’ as they ‘have not yet been fully acculturated into the foundational binary traditions of western education’. Several studies involving Indigenous young people in Canada also support this conclusion by illustrating their ‘ontological inclusion of other-than-human actors’ (Hatala et al. Citation2019, 128), their ‘everyday relational practices grounded in spirituality, morality, and non-interference with nature’ (Morton et al. Citation2020, 6) and the ways in which both shape their values and behaviour (Bang et al. Citation2015). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that anthropocentrism is learnt, which opens up the possibility that it can be unlearnt, at least partially, through the engagement with alternative human-nature ontologies.

Emerging research further explores the role that innovative educational practices can play in raising children and young people’s awareness of their own human-nature ontologies, and of the existence and validity of others, which indicates a shift towards transformative education in both fields. This shift involves the disruption of ‘old ways of knowing and being’ (Skilling et al. Citation2022, 670) – including reason/emotion and human/nature binaries – that ‘limit imaginations and sap motivation to act’ (Ray Citation2019, 312). Cairns (Citation2021), as well as Jones and Davison (Citation2021), argue for centring affective processes more firmly in EE, while Huhmarniemi, Jokela, and Hiltunen (Citation2021, 7) argue that art-based approaches represent an opportunity for ‘deep existential and spiritual experiences, which are in touch with the body and mind, along with profound ideologies and emotions’. Taylor (Citation2017) uses the example of children’s reoccurring encounters with kangaroos to make the case for ‘Anthropocene-attuned common world pedagogies’ that ‘reaffirm the inextricable entanglement of social and natural worlds’. Similarly, Pollitt, Blaise, and Rooney (Citation2021, 1145, 1149) demonstrate how to open up ‘new ways of knowing and understanding’ by engaging preschool children ‘with and within weather through dance’, while Clarke (Citation2017, 313-314) makes the case for ‘flat environmental education’ based on ‘new materialisms’, which urges students to ‘consider’ how they are already ‘materially manifested of the world’. Payne (Citation2015, 169) advocates for using slow ecopedagogy – a form of gradual, embodied, experimental and student-led learning – to reintroduce the ‘non-anthropocentric’ into ‘Western thought patterns, habits and worldviews’, while Verlie et al. (Citation2020, 142) argue more broadly for introducing university students to ‘alternatives to the status quo’ that prompt reflection on ‘how we might need to think differently’. To facilitate such reflection, Verlie (Citation2021, 10, 7, 113) describes the practices of ‘encountering, witnessing and storying climate change’ as ‘embodied, affective and relational’ alternatives to simply ‘knowing about’ and ‘acting on’ climate change. Their aim is to ‘cultivate a relational understanding’ of ‘humans as part of climate’ that allows ‘climate-complicit people’ to ‘change themselves and the socio-economic structures they are entangled with’.

Opening up avenues to thinking differently further requires exposure to non-dominant human-nature ontologies. In this context, Cairns (Citation2021, 525) illustrates the importance of non-white leadership – and thus diverse ways of knowing, doing and being – in the transition from ‘colonial ideas of environmental stewardship’ towards more ‘ethical, relational entanglements with the more-than-human world’. In a similar vein, Hines, Daniel, and Bobilya (Citation2020, 125) argue that engagement with ‘traditional Cherokee environmental philosophies’ can encourage ‘younger generations to think on a deeper level about their relationship to nature’, while Hill and Brown (Citation2014, 226) argue that ‘Māori perspectives’ can build an ‘ethic of care that draws on, and connects to, the knowledges residing in local communities’ into outdoor education.

Additional points of exposure are currently located outside of education but could be translated and facilitated further in EE in the future. Mercer (Citation2022, 11), for example, argues that Christian theology has the potential to alleviate children and young people’s climate anxiety by ‘fostering ecological kinship’ with the ‘ecosphere that is God’s oikos’. Similarly, Benoit, Thomas, and Martin (Citation2022, 56) suggest that Shinto, which finds ‘meaning in a cosmic sense’, may help counteract feelings of hopelessness, yet also acknowledge the limited role that religion plays in the lives of children and young people in secular societies. Other scholars pick up on the potential of books, movies and TV shows to encourage children and young people develop ‘a sustainable way of thinking and an environmental mind-set’ by analysing the ecocentric messages that are contained in them (Arafah, Abbas, and Hikmah Citation2021; Hawley Citation2022; Yarova Citation2020, 478).

While the diversity of innovative educational approaches and additional points of exposure to non-dominant human-nature ontologies outlined in this section is encouraging, the majority currently represent visions for the future, the realisation of which faces several barriers. Even Payne (Citation2015, 179), who has successfully applied the slow ecopedagogy he is arguing for, still admits that this ‘processual means of becoming educated’ receives little space in his own university courses and tends to get lost in most mainstream ‘education of the mind’. This admission implies that the broader education system needs to be rethought to fully support children and young people to move beyond their nature disconnection, eco-anxiety and ontological insecurity.

4. Discussion

Our analysis of children and young people’s experiences of nature disconnection and eco-anxiety and the support they receive and require reveals an emerging shift towards educational practices that aim to transform dominant human nature ontologies in both fields. Despite this shift, however, educational practices that only aim to build personal nature connection and emotional resilience are still frequently recommended and implemented. In what follows, we briefly illustrate that without the former, the latter are not only insufficient to address youth nature disconnection and eco-anxiety in the long run, but also contradictory in their aims. We further demonstrate that emerging efforts to build ontological reflexivity resolve these contradictions and open up the possibility of responding to children and young people’s experiences holistically. On this basis, we make the case for expanding emerging efforts towards transformative change in EE practice and the broader field of education and highlight key future research required to realise this vision.

Our review has shown that youth nature disconnection is often understood as children and young people’s cognitive and emotional separation from nature deriving from declining opportunities to spend time outside. Creating such opportunities is therefore one common approach to fostering youth nature connection, which appears to enhance children and young people’s wellbeing and build their empathy for non-human species – at least in the short term. Beyond those immediate benefits, however, the potential of this approach is limited by several factors. Firstly, nature exposure is not universally perceived to be positive, as some children and young people associate it with dangers posed by other people (Eastwood et al. Citation2021) and natural disasters (Keith et al. Citation2022). Secondly, nature engagement activates are not universally accessible and often attract ‘students from predominantly white middle- and upper-class families’ who have the resources participation requires (McLean Citation2013, 356). And thirdly, such activities are often contained to specifically dedicated times and supposedly wild places that are separate from children and young people’s everyday environments, which not only risks that connections to the former do not extend to the latter (Hill Citation2013), but also inadvertently reinforces the human/nature binary.

Our review has further shown that youth eco-anxiety is often understood as children and young people’s fear of environmental doom, which is reinforced by the insufficient action that is taken to address the climate and biodiversity crises. Helping children and young people take individual and/or collective action remains a common approach to build their emotional resilience, despite growing concerns regarding its long-term effectiveness. In this context, the promotion of individual pro-environmental behaviour has been criticised extensively for transferring the responsibility of addressing the world’s ecological crises to individuals and for paradoxically implying that a reduction of carbon consumption can be achieved through consumerism, thus perpetuating the hope that climate change can be solved without changing neoliberalism (Cao Citation2019; Cossman Citation2013). As such, it meets the definition of ‘cruel optimism’, which occurs when hope keeps us attached to a situation that is actually causing us harm (Berlant Citation2011). The promotion of collective action as a solution to eco-anxiety represents an opportunity to depart from the individualising framing of pro-environmental behaviour, but only if great care is taken to avoid a disproportionate allocation of responsibility to younger generations (Nairn Citation2019). It is not only important for educators and caregivers to actively support children and young people’s collective action (Cairns Citation2021; Ray Citation2019; Skilling et al. Citation2022), but also to take just as much – or more – action themselves (Diffey et al. Citation2022; Hickman et al. Citation2021). It is further important to accept that business as usual cannot solve the problem (Berlant Citation2011) and to avoid the reiteration of human exceptionalism through an emphasis on human agency alone (Taylor Citation2017), as solutions that fail to challenge the ideology that is the root cause of world’s ecological crises may temporarily alleviate eco-anxiety but will ultimately worsen the ontological insecurity that often underpins it.

In addition to being insufficient solutions for nature disconnection and eco-anxiety individually, efforts to foster personal nature connection and encourage pro-environmental action without an ontological component may also inadvertently counteract each other. Specifically, fostering personal nature connection without transforming humanity’s relationship with nature is likely to worsen children and young people’s eco-anxiety in the long term, as it will increase their grief associated with its degradation (Crandon et al. Citation2022; Léger-Goodes et al. Citation2022). Encouraging individual and/or collective action without transforming humanity’s relationship with nature is likely to worsen children and young people’s disconnection from nature, as it can make them feel guilty about seeking pleasure in nature (Ray Citation2020) while simultaneously enabling them to ‘‘bounce back’ to anthropocentric ways of being’ (Verlie Citation2021, 112). Yet remaining detached is not the answer either – even if only human wellbeing is taken into consideration – as humanity’s interrelatedness with nature is ‘not a choice’, but a fact. Regardless of how conscious individuals are of this interrelatedness, their wellbeing will be affected when ‘organs fail in extreme heat’, ‘local economies’ reel ‘from cyclones’ and ‘ancestral homelands are slowly eaten away by the rising tides’ (Verlie Citation2021, 7). When the experiences of children growing up in an increasingly urbanised, technological and ecologically volatile world are considered holistically, the need for education to build ontological reflexivity thus becomes even more apparent.

In fact, the contradictions between the fields of youth nature disconnection and youth eco-anxiety dissolve when their focus shifts towards ontological reflexivity as a solution to children and young people’s perceived human-nature separation and ontological insecurity. Emerging research in both fields argues for the dismantling of human/nature and body/mind binaries, which involves challenging dominant conceptualisations of nature as ‘wildlife’, ‘natural processes’ and ‘‘natural’ places’ (Clarke Citation2017, 309; Hill Citation2013), exclusive ascriptions of culture and agency to human beings (Taylor Citation2017; Verlie Citation2021) and common limitations of knowledge to rational and ‘disembodied abstraction’ (Skilling et al. Citation2022; Verlie Citation2021, 2). It involves pedagogies that foster a relational understanding of ‘children and place’, ‘children and materials’, ‘children and other species’ (Clarke Citation2017; Taylor Citation2017, 1456) and children and climate (Pollitt, Blaise, and Rooney Citation2021; Verlie Citation2021). Diverse approaches employed for these aims include the encouragement of critical reflection of common assumptions (Ray Citation2019), the directing of attention to the relations children and young people are embedded in (Verlie Citation2021), the facilitation slow, repeated, extensive and embodied engagement with these relations (Payne Citation2015; Pollitt, Blaise, and Rooney Citation2021; Taylor Citation2017) and the embedding of outdoor experiences in non-anthropocentric ways of knowing oneself and the world (Clarke Citation2017). Through their individual evolutions, the fields of youth human-nature relationships and youth eco-anxiety are therefore converging and illuminating a coherent way forward.

This evolution is co-occurring with a growing body of environmental and sustainability education research that is concerned with the transformation of its ontological and epistemological base in the pursuit of environmental sustainability (Anastacio Citation2020; Baumber Citation2022; Beeman and Sims Citation2019), decolonisation (Ajaps Citation2023; Ali et al. Citation2019) or both (De-Abreu et al. Citation2022; Hatcher Citation2012). As part of this transformation, the approaches described above are complemented by efforts to decentre dominant human-nature ontologies (Mcphie and Clarke Citation2015; Rodrigues Citation2018; Rooney Citation2019; Taylor Citation2017; Wallin Citation2022) and to expand the space for non-dominant human-nature ontologies – such as those contained in Eastern philosophies (Chang Citation2020; Savelyeva Citation2017; Yoneyama Citation2019, Citation2020; Citation2021) and Indigenous knowledge systems (Cohn Citation2011; Harrison et al. Citation2017) – in pedagogies and curricula.

Despite the emergence of such innovative forms of EE, they are still exceptions rather than the norm (Taylor Citation2017), and their widespread implementation faces personal and structural barriers. Building ontological reflexivity can be difficult for educators and students alike. It can be emotionally challenging, as it requires those who are complicit in the systems that drive current crises to endure the loss of the privileges this complicity provides and of increasingly conscious relations with the more-than-human world at the same time (Ray Citation2019; Verlie Citation2021). It can further be intellectually challenging, as many disciplines do not traditionally concern themselves with the existence and validity of diverse knowledge systems (Boyle, Wilson, and Dimmock Citation2015; Kemper et al. Citation2019; Ray Citation2019; Skilling et al. Citation2022) and the institutional silos within universities impede opportunities for interdisciplinary engagement (Baumber Citation2022). More broadly, ‘epistemologies of the South’ still ‘struggle to achieve legitimacy and inclusion’ due to the ‘entrenched belief that Western science embodies objectivity and transcends culture’ (De-Abreu et al. Citation2022, 2) and the English language – which dominates education practice and research – is inadequate for representing Indigenous lifeworlds (Ali et al. Citation2019), conceptualisations of Country (Harrison et al. Citation2017) and the recognition of nature as ‘all-that-is’ (Beeman and Sims Citation2019, 204).

The barriers within the field of education are connected to the broader political and economic structures within which it is embedded, such as the Sustainable Development discourse that locates ‘environmental sustainability within capitalist growth and free markets rather than opposing them’ (Tulloch Citation2016, 174). These structures drive the ongoing ‘commodification and commercialisation’ of an education system that is already based on ‘unconstrained progress, individualism and competition’, which is at odds with transformative EE. They further universalise pedagogies and curricula ‘from the Global North to the Global South’ rather than diversifying them from the Global South to the Global North (Ajaps Citation2023, 1030; Anastacio Citation2020, 549). Consequently, the ‘majority of educational approaches continues to hold on to environmental stewardship ideas that form the ‘status quo’ of default human-centric concerns and priorities’ despite ‘some moves’ in EE to illustrate their insufficiency and develop alternatives (Taylor Citation2017, 1451). Without fundamental changes within and beyond the broader field of education, there is therefore a risk that diverse human-nature relationships will – at best – be inserted as one additional course, with all other courses remaining bound by dominant ontologies and epistemologies.

To mitigate this risk, we echo UNESCO’s recent call for transformative change in education itself, which envisions the diversification of the field’s ontological and epistemological base to create the pedagogy of solidarity required to address the world’s ecological crises: