ABSTRACT

In recent years, Sierra Leone has witnessed intense population movements. During the civil war (1991–2002), many populations fled the fighting zones of the interior to take refuge on the coast. Since the conflict ended, new populations have reached the coastal area with the hope of accessing economic opportunities in the fishing business. Mobility, along with changing sociopolitical and economic conditions, has generated conflict between immigrants and Sherbro populations, who consider themselves autochthonous and deny migrants the freedom to access political and land rights. The paper argues that present dynamics of conflicts are rooted in long-term patterns of settlement and relationships of reciprocity between groups. Relations between migrants and local populations are grounded in a sociocultural idiom that implies the institutionalization of practices of reciprocity between local inhabitants (hosts) and later settlers (strangers). The host/stranger reciprocity system is an emic model of cultural action embedded in historical and power relations between groups. It implies the progressive integration of strangers into the host society. This paper highlights how, in a situation of conflict, long-established social relationships between groups are reevaluated with reference to norms of integration and reciprocity. The paper draws on Sherbro oral traditions to show how social memories about interethnic relations are reframed with reference to values and expectations of reciprocity, in order to explain the recent conflict that opposes Sherbros to immigrants. Sherbros use oral traditions to interpret these tensions in a long-term perspective, thereby expressing their own view on settlement, conflict and integration.

This article examines conflicts between local populations and migrant groups in a West African context where important socioeconomic transformations have exacerbated competition for resources. It analyses the way local populations imagine and reinterpret through oral traditions their relationships with newcomers over time. Local oral tradition is an ambiguous social product. On the one hand, it participates in supporting autochthonous claims – the claim that one is ‘born from the soil’. Local populations perceive their identity as tied to a distinct territory to the exclusion of other groups. Often, the autochthonous status is linked to a specific ethnic identity. Autochthonous discourses contribute to drawing an exclusionary boundary between those who belong and those who do not, thereby reinforcing representations of recent immigrants as a homogenous rival group (Bräuchler & Ménard, Citation2017). On the other hand, oral traditions describe a ‘standard’ integration: they create a narrative about the norms and practices through which a newcomer should integrate into the host group. With reference to conflicts on the coastline of Sierra Leone, I show that this normative discourse about integration revolves around the notion of reciprocity. I argue that present dynamics of conflict are rooted in long-term patterns of mobility, settlement and reciprocal practices between ethnic groups. In oral tradition, long-established interethnic relationships are reevaluated with reference to customary norms of integration and reciprocity. Local oral traditions thus reflect the permanent tension that exists between the necessity of including new populations and a tendency towards exclusion when demographic, political and socioeconomic conditions change in favour of recent immigrants.

Introduction

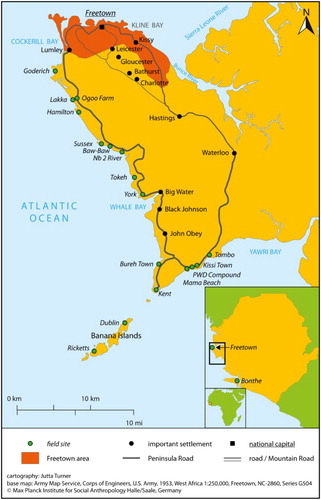

The part of the Sierra Leonean coast known as the Peninsula, situated south of the capital Freetown (see ), has been at the centre of frequent population movements. In 1808, it became a Crown Colony. In the course of the nineteenth century, the British resettled many former slaves in the Colony, who established their own settlements on the coast and engaged in fishing and trade. Their descendants are known as the Krios and constitute a minority ethnic group in the country. In 1896, British authorities declared a Protectorate over the rest of the country. During colonial and postcolonial times, the Peninsula, due to its proximity with urban Freetown and the development of intense economic activities, became a territory of migration for populations from the interior. In particular, the growth of the fishing economy has been key to the development of the region since the nineteenth century and its development has been tightly related to the growing demand of the Freetown urban market, thereby making the Peninsula attractive for migrants.

The civil war that raged in the country between 1991 and 2002 resulted in a critical demographic change in Freetown and on the Peninsula. Coastal settlements hosted displaced populations fleeing the fighting zones of the interior, many of whom eventually settled in the region. During the post-conflict period, new economic opportunities in the commercial fishing economy, as well as the lack of employment in the countryside, attracted to the coastal region a large population of Temne-speaking migrants coming from the north and the southern coast of the country (see Diggins, Citation2015). Fishing constitutes the primary livelihood for most people on the Peninsula, along with fishing-related activities such as fish-smoking, selling, wood-cutting and charcoal-burning. During the past decade, major coastal towns, such as Goderich, Tombo and Tokeh, have expanded their fishing activities and experienced a high population growth.Footnote1

The presence of a large population of newcomers, and their massive involvement in fishing, has generated tensions with Sherbro populations, who view themselves as autochthonous on the Peninsula.Footnote2 At the time of research, Sherbros expressed their resentment against the presence of immigrants, who held a majority in large coastal settlements, were economically dominant, and in some cases, had attained political leadership. The conflict, among other causes, has been triggered by the massive involvement of migrants in a capital-intensive and market-oriented type of fishing, which competes with Sherbro small-scale fishing techniques. In settlements, such as Goderich and Tombo, fishermen use motor-boats and ring nets to catch large quantities of small fish that are later smoked and sold across the country. Tombo in particular has become a centre for seasonal fishing migration, which ensures the availability of a large number of crewmen during the peak of the fishing season. By contrast, local Sherbro populations practice local artisanal canoe fishingFootnote3 and catch large fish more expensive per unit to supply the local market.

In the remainder of this article, I analyse Sherbro oral traditions to illustrate how Sherbros perceive their relations with immigrants in both a historical and social perspective. The data presented below are based on a 16-month fieldwork (March 2011–June 2012) in the various settlements of the Freetown Peninsula. I collected official versions of oral traditions from local Sherbro elders, either in Sherbro or in Krio. Many Sherbros on the Peninsula do not speak the Sherbro language and prefer expressing themselves in Krio, the regional lingua franca. Local political elites were of various origins, but even in places numerically dominated by newcomers, headmen directed me towards Sherbro elders and did not interfere with my work. However, this exercise opened debates about the relationship between local and newly arrived populations, which led to further informal discussions and semi-structured interviews with both members of the Sherbro group and immigrants. This allowed me to gather competing views about integration and reciprocity. The anonymity of informants has been preserved and names are not mentioned.

The host/stranger relationship, integration and autochthony

On the Upper Guinea Coast region, oral tradition, by codifying the arrival of groups in a given area, establishes social hierarchies between groups of firstcomers, who consider themselves autochthones, and groups of latecomers, who are considered strangers.Footnote4 Murphy and Bledsoe (Citation1987), discussing Kpelle society, show that people employ oral tradition to highlight events of local political significance, which they term ‘pivotal historical events’, such as an early migration, land appropriation or the definition of new political boundaries, to create political and social hierarchies with regard to leadership, inheritance rights and access to land.

Relationships between firstcomers (or hosts) and latecomers (or strangers) are informed by reciprocity. In the West African region, the host/stranger reciprocity mechanism is an emic model that was identified by historians (see Brooks, Citation1993; Dorjahn & Fyfe, Citation1962; Mouser, Citation1975) as a key social mechanism ensuring the integration of strangers into local communities. Hosts and strangers articulate their relationships around a set of mutual obligations that place both groups in a relation of interdependence (also see Bedert, Citation2017).Footnote5 Newcomers, who wish to secure permission to settle or lead an economic activity in a specific place, such as trading or farming, place themselves under the authority of the local landlord, who welcomes them and grants them protection. This compels strangers to reciprocate by being loyal to the landlord, following local rules and refraining from involving in local politics (Dorjahn & Fyfe, Citation1962, p. 392).Footnote6 Yet, the host/stranger reciprocity mechanism does not establish fixed barriers between groups (Trajano Filho, Citation2010, p. 161). Rather, it allows for the accommodation of cultural and social heterogeneity and results in the emergence of multi-ethnic polities and fluid ethnic identities (Trajano Filho, Citation2010, p. 162). Social categories are open to permanent renegotiation (Lentz, Citation2006, p. 14): relations between groups can be reassessed as new people arrive, but strangers and their descendants also normally gain land and political rights over generations. Despite the regional character of this mechanism, Bräuchler (Citation2017) also describes processes by which ‘outsiders’ in Eastern Indonesia are included in the local political system, as complements to local authorities and as neutral mediating forces.

The host/stranger reciprocity mechanism allows societies to negotiate alterity at a local level and incorporate newcomers into the host community. Strangers are not considered ‘foreigners’ nor ‘outsiders’: they have a specific social status and enjoy specific rights, which binds them socially and emotionally to the host group. Mouser (Citation1975, pp. 426–427) argues that historically, the purpose of this mechanism ‘was not one of control but of accommodation and assimilation by stages and over generations which brought structural changes to local societies’. Integration is thus understood as the acceptance of one’s status as stranger to the host community and the fulfilment of the social obligations deriving from one’s position as stranger. This process often results in the social and cultural assimilation of the settlers’ group into the host community. However, this type of integration rests on specific socioeconomic conditions, such as resources availability, for example, land and other economic resources. Wider regional and national dynamics, such as access to citizenship, also shape local attitudes towards newcomers (Sarró, Citation2010, p. 232).

On the Peninsula, several factors have affected the relationships between local populations and settlers. Firstly, the restoration of multiparty politics after the war, driven by a global agenda for democratization, consolidated the dividing line between the two main parties, the Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) and the All People’s Congress (APC). The APC government, in power at the time of fieldwork, usually enjoys support from Temne populations. Thus, Sherbros have held it responsible for encouraging in-migration into the area.Footnote7 Democratization also opens debates about local belonging and the right to vote (see Geschiere, Citation2009). The new voter registration process binds individuals to a specific location for their participation in a wide range of elections, from the local to the national level, and thereby encourages politicians to secure votes at a local level. During the first registration process in 2012, Sherbro populations strongly criticized this new framework, since the result of local headmanship elections could be influenced by registered voters, whom they did not consider autochthonous. Whereas Sherbros advocated for the negotiation of relations between groups in line with customary law, immigrants supported the government’s legal discourse based on individual rights to register and vote in any locality.

These changes have also taken place in an uncertain environment characterized by economic competition and land shortage. A continued landlord/stranger relationship implies that strangers and their descendants, particularly second-generation tenants, acquire land rights (Dorjahn & Fyfe, Citation1962, p. 392). Long-term land occupation is a legitimate reason to access property under customary law.Footnote8 In turn, land ownership implies the right to take part in local politics. On the Peninsula, land pressure and the increasing value of land explain that landowning families have been less inclined to grant ownership to newcomers (see Ménard, Citation2015). Sherbros reject the claim of immigrants to obtain local citizenship rights, which they link to an autochthonous status (also see Bräuchler, Citation2017). People, who have recently migrated, by contrast, discard the legitimacy of local authorities and reaffirm the ultimate role of the state in legalizing ownership and arbitrating local disputes. Against the local politics of autochthony, they brandish national citizenship as granting them rights also at the local level (O’Kane & Ménard, Citation2015).Footnote9 Ownership legitimation thus becomes part of a process of recognition of one’s local rights by certain institutions (see Lund, Citation2002, p. 13). This legal dimension further polarizes ethnic and social identities along different normative orders and conceptualizations of national citizenship (Bräuchler & Ménard, Citation2017).

Autochthonous discourses developed by Sherbros reveal the inability for both groups to maintain customary modes of interaction and integration. Autochthony rests on essentialist definitions of identity (see Bräuchler & Ménard, Citation2017). Social identities such as autochthones and migrants are often supported by specific ethnic identities that become bounded and exclusive (Geschiere & Jackson, Citation2006, p. 5). Strangers normally get incorporated into local societies through a specific sociocultural process, which may involve the acquisition of language, customs, livelihood or participation to religious practices, so that eventually ‘all traces of strangeness’ can be lost (Shack & Skinner, Citation1979, p. 9). Anthropologists working with coastal populations of the Upper Guinea Coast note the importance of ‘idioms of transformation’ (Berliner, Citation2010, p. 261; Sarró, Citation2010, p. 237): by adopting a set of attributes, such as pursuing a certain livelihood or joining a local secret society, an individual can acquire a new ethnic identity. Yet, as Shack and Skinner note (Citation1979, p. 10), the ‘smallness of scale’ plays a decisive role in determining the receptivity of hosts towards strangers (compare also Bräuchler, Citation2017). The fact that recent settlers have become a numerical majority, along with the factors that have allowed for their recent socioeconomic and political empowerment, has had an impact on the attitudes of local populations towards them, but has also lessened the necessity for immigrants to enter reciprocal relations with landowning families. Rather, immigrants have turned towards the state in order to free themselves from customary relationships, create their own polities and gain local citizenship rights on the Peninsula (O’Kane & Ménard, Citation2015).

Temne settlement in Sherbro oral tradition

Sherbro oral tradition reflects the ambiguity of the host/stranger relationship: it supports the idea of an autochthonous ethnic identity opposed to that of immigrants, while setting the criteria for their social integration. Those criteria include marriage within a Sherbro community, initiation or initiation of one’s children into secret societies – namely local cults with initiation rites – and participation in local ritual activities, and often a change of livelihood to canoe fishing. As Shack notes (Citation1979, p. 41), it is a ritual process, whereby strangers experience the passage from lower to higher status. However, oral traditions concerned with the settlement of Temnes contrast with oral traditions that describe integration processes based on marriage and a common livelihood (Ménard, Citation2015, p. 81). Rather, these narratives suggest that Sherbro local authorities initially opposed the creation of a host/stranger relationship with Temne settlers, due to their suspicion that Temnes would not respect customary rules of integration and would thus represent a threat to Sherbro economic and political interests. Thus, oral traditions provide a long-term explanation to the conflict with immigrants and give a justification for Sherbros’ attitudes towards newcomers and unwillingness to put into practice the ideal of reciprocity, for instance regarding land allocation.

This article focuses on Sherbro group accounts. As Vansina puts it (Citation1985, p. 19), group accounts ‘embody something which expresses the identity of the group in which they are told or substantiates rights over land, resources, women, office and herds’. As historical narratives, they are based on past events, but go through a discursive process of selection and alteration that serves present purposes (Murphy & Bledsoe, Citation1987; Tonkin, Citation1986; Vansina, Citation1985). Group accounts present an official narrative of the group’s history that can help supporting autochthonous claims, justifying relations of power or legitimizing property rights within a territory (Lentz, Citation2006). As such, they support the construction of distinct collective identities. As Bedert (Citation2017) demonstrates with the case of the Mandingo in Liberia, the long-term construction of identity narratives can help framing a distinct ‘historical imagination’ that characterizes group identity. Group accounts often give a homogeneous representation of ethnic groups, whose members may have heterogeneous origins. In local Sherbro communities, the ethnic labels ‘Temne’ and ‘Sherbro’ are used to draw a line between immigrants and autochthones, regardless of the heterogeneity of origins of individuals included in each group.

While social conflicts in Sierra Leone are often presented as part of the post-war timeframe, in this case post-war economic migration, they are actually grounded in long-term patterns of mobility and settlement. Migration of Temne fishermen to the Peninsula coast has been reported since the nineteenth century.Footnote10 Migration to Tombo, which lies at the crossroads of several trading routes, has received comparatively larger attention in maritime studies (Hendrix, Citation1984; Kotnik, Citation1981) and is used here as a representative illustration of demographic changes related to fishing. The first large Temne migration to Tombo likely occurred at the end of the nineteenth century when the fishing industry was growing alongside the demands of the Freetown market (Kotnik, Citation1981, p. 17). A second demographic change followed in the 1920s, as rising standards of living led Temne fishermen and their families to migrate to the Peninsula and settle permanently in Tombo (Hendrix, Citation1984, p. 13). This change coincided with a specialization in bonga fishing, which could be easily marketed in the interior due to its low price (Hornell, Citation1928). The Peninsula road constructed at the end of the 1930s also facilitated selling to markets in Waterloo and Freetown.

Nevertheless, oral traditions recall the 1960s as the main turning point in Sherbro/Temne relations. To borrow Murphy and Bledsoe’s term (Citation1987), the 1960s constitute the ‘pivotal moment’ that explains later relationships between the two groups. The fishing economy changed radically in the 1950s with the arrival of Ghanaian fishermen, who introduced new fishing techniques, such as larger canoes and crews, outboard motors and nylon ring nets. This gear is still in use today for Ghanaian-boat fishing, which is prevalent in Tombo. As fishing became market-oriented, populations fully specialized in fishing, processing and marketing fish. Hendrix (Citation1984, p. 19) states that ‘the period from about 1955 to 1965 can be characterized as a period of radical social and economic development in the Tombo fishery’. From this point onwards, the number of fishermen, traders and fishmongers settling in Tombo continued to grow.

During the same period, relations between Ghanaian and Temne fishermen became uneasy. Temne complained of unfair competition due to the Ghanaians’ capital-intensive fishing techniques. Ghanaians were then prohibited by colonial authorities from fishing in certain areas of the Peninsula and were finally expelled from the country by the Sierra Leonean government in 1967. Temne acquired Ghanaian boats and gears and took over this form of fishing almost exclusively (Krabacher, Citation1990, p. 203). Temne fishermen still dominate Ghanaian-boat fishing, mostly in Goderich and Tombo. They also significantly outnumber other fishermen and earn greater profits. Sherbro oral tradition stated that Temne fishermen trained with the Ghanaians and acquired their techniques. It emphasized not the arrival of Temnes per se, but their massive involvement in fishing after the departure of the Ghanaians, which also implied that Temne populations settled permanently.Footnote11 Sherbros considered that since this particular historical turning point, Sherbro/Temne relations had been characterized by conflicts regarding livelihoods.

Fittingly, Sherbro oral tradition tended to silence early Temne migration and rather focused on recent arrivals. Informants often mentioned that Temnes came last to the Peninsula and refer to migration from the 1960s onwards. The following founding myth, collected in Tokeh on 21 July 2011, is at odds with this usual historical sequence. It mentions the first Temne man, who came to Tokeh in the first half of the twentieth century. I collected this narrative during an official encounter with the local authorities of Tokeh. The three local representatives considered themselves Sherbro with regard to ancestorship and one of them delivered the following account in Sherbro:

The first people were fishermen. They were coming from Shenge (on the Sherbro coast). They passed along this road to go to Freetown. … They settled by the side of the river. … No other people were here, only Sherbros. One day, the first Temne man came to this village. His name was Pa Santigi. He used to farm for Sherbros and worked here by seasons. He used to go back to his village when the rains started. Sherbros used to dry fish for him before he departed. After the first rainy season, he came back with his brother, who was a farmer too. … Pa Santigi’s brother, after another rainy season, came with another brother. Sherbros started to protest that they did not want a lot of Temne people here. Pa Santigi’s brother said: ‘No, this is my younger brother. He will settle quietly … we will not cause any problem’. At that time, one of our Sherbro grandmothers … met this man on his farm and they fell in love, but kept this love secret. People did not know. But by the time the brothers needed to go back to their village, this brother said that he did not want to return to his village, since he had a woman here. Pa Santigi said: ‘I have been here for a long time and I did not take a wife. And you have a wife? Sherbros said that they did not want any problem here. How will I tell them that I leave my brother here?’ The brother said: ‘I want you to tell them that I am staying here because I am with one of their daughters. I will not cause any problem and just continue doing the work we are doing.’ Pa Santigi called the Sherbro elders and said that he had something to tell them. The elders asked him who the brother was in love with and he said Mamfuei. They called Mamfuei and asked her. Mamfuei said that it was true … When the time came for Pa Santigi to go, Sherbros dried fish for him. He left his brother. The woman got pregnant and had a son, Kontham. It is [Pa Santigi’s brother] who brought the Muslim religion here. He is the first Temne who settled here.

The founding myth describes the reluctance of Sherbros to establish a host/stranger relationship with Temne settlers. The integration of early immigrants by way of marriage or livelihood was not considered desirable. The original relationship implied a strict social, economic and geographical separation between the two groups. Sherbros and Temnes practiced a type of barter system based on farming/fishing exchange and Sherbros only tolerated the seasonal presence of Temne farmers. Many Sherbro oral traditions mentioned that Temne farmers did not stay on a permanent basis and returned home regularly. Because of their farming activity, it is also implicit that settlements were separated. The story is silent about Temnes’ later involvement in fishing.

The narrative suggests that a break from the first arrangement between the two groups led to the disruption of initial relations based on exchange and trust. The establishment of kinship is critical to this disruption. Initial relations between Sherbros and Temnes did not involve wife-exchange, whereas kinship normally structures social hierarchies between hosts and strangers in patrilineal societies of the Upper Guinea Coast. The host/stranger relationship implies a link of subordination ‘between the descendants of politically superior patrilineage, defined as firstcomers and as wife-givers, or mother’s brother, and the descendants of subordinate patrilineages, defined as latecomers and as wife-takers, or sister’s sons’ (Højbjerg, Citation2007, p. 237). Matrilateral kinship, which refers here to the relationship between mother’s brother and sister’s son, structures social and political relations between both groups (Murphy & Bledsoe, Citation1987).

In Sherbro society, the pattern of integration differs from the patrilineal model. Sherbro society has a cognatic descent system that gives primacy to matrilineal ties (MacCormack, Citation1979). Therefore, group identity and social rights continue to be ‘transmittable through women’ (Day, Citation1983, p. 84). Sherbro society has retained a matrilineal bias with regard to the integration of strangers: children born to male strangers are considered to belong to their mother’s descent group. This matrilineal ideology is positively correlated with the full incorporation of in-marrying men and their children into Sherbro society.Footnote12 This process results in the social and cultural absorption of strangers and the rapid levelling of social hierarchies, since strangers and their children can rapidly become full members of the Sherbro ethnic group. Upgrading one’s social position can happen within a generation (MacCormack, Citation1979, p. 198), as the main criteria for Sherbro ethnicity remain Sherbro female ancestorship and membership in local secret societies, often combined with the adoption of the fishing livelihood. This system does not lead to the establishment of permanent social and political hierarchies based on kinship. However, integration implies that strangers, as part of their reciprocal obligations, commit to abandoning their previous identification and to acquiring Sherbro identity by conforming to local rules.

In the narrative, by their decision not to create kinship ties with Temnes, Sherbros mark their unwillingness to consider the settlers as their ‘strangers’.Footnote13 The relationship between Pa Santigi’s brother and Mamfuei is not part of an official process of exchange between groups but an isolated incident. The situation remains hidden from the elders of the host group. Trust disappears and the presence of Temne migrants in the settlement is regarded with suspicion. The brother has also concealed what he has done from Pa Santigi himself. He thus betrays authority figures of his own group, who had initially negotiated the terms and conditions of their presence in the Sherbro community. It also mirrors present-day statements about the changing nature of host/stranger relationships over generations. People commonly mentioned that the first settlers respected their obligations, while following generations felt more comfortable in breaking the rules.

The kinship idiom – the way kinship expresses wider social, economic and political relations between groups – is an idiom of non-association that refers to long-standing dynamics of political and economic rivalry. Sherbro oral traditions, by describing the reluctance of Sherbro authorities to create kinship ties with Temne settlers and to integrate them by way of marriage, expresses the fear that Temnes may refuse sociocultural assimilation to the host group, reject Sherbro authority and try to impose their own leadership. Informants often mentioned that Temnes settlers, in the past, were usually neither associated with local leadership nor involved in decision-making.

Oral traditions thus give a long-term timeframe to the present conflict and allow Sherbros to reinterpret their past relations with Temnes as problematic. The narrative reflects the fact that recent immigrants reject the Sherbro model of integration. Sherbro political and ritual authority erodes as newcomers compete for leadership or oppose ritual practices related to secret societies. For instance, immigrants, who are Muslims for their large majority, reject local ritual practices on the ground that secret societies are incompatible with Islam, urbanization and modernity (Ménard, Citation2017).Footnote14 By stressing their inability to comply with the customary rules of the host group, oral traditions put the blame of the contemporary conflict on immigrants and gives a justification for Sherbros to disengage themselves from reciprocal relations with them. The founding myth of Tokeh also contains an acknowledgment of powerlessness, as the presence of newcomers, who are described as imposing their permanent stay, has to be negotiated anyway.

The description of problematic kinship ties with Temnes also suggests the development of economic competition between the two groups. Oral tradition in Tombo described a similar process as in Tokeh, whereby Sherbros were forced to accept kinship relations with Temnes, which led to permanent Temne presence in the settlement. Here is one version of this story:

When the Temne people came, they came by boat to do fishing. People did not want them here. One man was called Jamba and called his Sherbro brothers. He said that they should not accept them inside. But it happened that Aunty Nakana fell in love with Yamba Legbe, the first Temne man. That was in 1958/59. People did not like him but the women were able to convince their brothers that they should not drive him away. But Jamba said: Tomorrow, you will understand what I tell you. [29 March 2012, Tombo, story told by a Sherbro local authority]

An ambiguous process of integration

Oral traditions allow Sherbros to (re)interpret long-term interethnic relations with reference to a ‘standard integration’ and changing power relations between groups that allow (or not) for the continuation of reciprocal relations. Therefore, historical narratives also point to interactions and processes of integration between Sherbros and Temnes. They give examples of immigrants, who integrated into Sherbro society by complying with customary rules pertaining to the host/stranger model. Personal narratives revealed that many individuals, who claimed themselves Sherbro, also had Temne ancestorship. However, Temne ancestry was often concealed, due to historical and political factors. Firstly, representations of ethnic and social identities are deeply rooted in the colonial past. In colonial hierarchies, populations of the Colony, Krios in particular, had access to Christian education and were considered ‘civilized’ as compared to ‘natives’ from the interior.Footnote15 By contrast, Temnes suffered from negative stereotyping, as colonial authorities did not encourage the establishment of schools in the northern Temne region, where Islamic schools were predominant (see Bolten, Citation2012). Ethnic clichés still stress their ‘lack of education’. By recalling their historical belonging to the Colony, Sherbros emphasized a privileged social status opposed to that of immigrants (Ménard, Citation2015). Secondly, the sociocultural and economic differences between Freetown and the Provinces persisted during the postcolonial period – urbanization, modernity and social upward mobility being mostly associated with Freetown. In the post-war context, Temne immigrants have contested the possibility for Sherbros and Krios to claim autochthony in a territory that offers opportunities for all Sierra Leoneans.Footnote16 Therefore, to deny Temne family connections is an intimate consequence of the polarization of ethnic identities on the political chessboard, as it has become imperative to dissociate oneself from newcomers and prove one’s commitment to Sherbro identity and one’s belonging to the Peninsula territory.

Thus, Sherbro oral traditions referring to Temne settlers describe a ‘standard integration’ located in an idealized past characterized by socioeconomic and political conditions that allowed for the preservation of Sherbro interests. Oral tradition contrasts early migration in the 1960s with recent migration and emphasize the willingness of early migrants to accept Sherbro authority and respect local customs. Firstly, historical narratives collected in settlements, where land conflicts between local people and settlers constituted a pressing issue, stressed that early migrants acquired land in a customary way: they gave gifts (kola), such as money, rice and rum, as signs of respect towards landowners, who allocated them land. This was set against the behaviour of recent immigrants, who tended to bypass local authorities and claim land directly from the state. Secondly, it was claimed that seasonal migrants in the 1960s came from the Bullom shore and practiced artisanal small-scale fishing as their main livelihood. This was compared with the supposed lack of fishing knowledge of recent immigrants – many of whom are actually fishermen. Livelihoods as referred to in oral tradition becomes a way to emphasize the sociocultural similarities and peaceful relations that Sherbros claim to have had with early migrants. Thirdly, oral traditions stressed that early migrants showed their acceptance of Sherbro political and ritual authority either by joining secret societies or by giving their children to be initiated. Sherbros often evoked laughingly the fact that settlers, at that time, ‘were scared’ of the male secret society and settled outside of local towns in order to avoid interfering with ritual performances (Ménard, Citation2017).

These various elements create an account of an ideal-type of integration that certainly silences past conflicts. Oral traditions present a set of customary norms, through which migrants are expected to acquire local Sherbro identity. One example of ‘successful integration’ appears in the founding myth of Tokeh. In the narrative, Pa Santigi’s brother and Mamfuei are the paternal grandparents of the former headman of Tokeh. Locally, the former headman is considered Sherbro, because he is born in a Sherbro settlement, he has a Sherbro mother and he is a member of Poro. This illustrates the flexible process through which one can acquire Sherbro identity over generations and refers to the family’s gradual inclusion in Sherbro political and ritual structures.

Informants mentioned membership in Poro, the male secret society, as a necessary condition to acquire Sherbro identity.Footnote17 The Poro sacred grove is a place for ritual initiation, meeting and decision-making: it symbolizes the sacred value of the land and the political authority of landowners (see Hoffer, Citation1971; Murphy, Citation1980). Therefore, the initiation of strangers and their children is a way to maintain Sherbro authority over them (Hoffer, Citation1971, pp. 185, 313). The integration of settlers is often measured according to their willingness to comply with the political and ritual authority embodied in Poro leadership. About the former headman’s family background, one Poro senior member said: ‘His grandfather had a lot of children: [he named them by their society names]. He put all of them in the society here, all of them. He put them here, but he did not [want to join Poro].’ When I asked why, he responded: ‘Because of the agreement he made with the Sherbro people. He agreed to dance to their tune.’ This statement stressed the fundamental gesture of moral commitment and good relations with the Sherbro: giving children to be initiated into Poro. The expression ‘to dance to their tune’ indicated the grandfather’s compliance with community laws, despite his personal decision not to join Poro. Another senior member had a similar opinion about the former headman and his family:

[The grandfather] had a child, who had a child, who is [our] former headman. His father was married to our big sister. … He is a Temne but he relates to the Sherbros. He ruled more than thirteen years. But he joined with us as a Sherbro now, because he’s born here and he married to our sister who is a Sherbro. His father was named [society name], he had a Sherbro name, he had a society name. So he’s a Sherbro, he had become [dɔn tɔn] Sherbro. And even if your father is a stranger, but if you are born here, you are a citizen, they will not drive you away. [Poro senior member, 11 April 2012, Tokeh]

Nevertheless, in many ways, the former headman was considered ‘more Sherbro’ than the current headman. The headman at the time of research was part of Sherbro landowning lineages on both sides of his family tree. Recently, he had converted to Islam, rejected Poro ritual practices and established his voting base among newcomers. His detractors often said of him that he had become Temne. In the local context, the former headman, the descendant of a ‘stranger’, appeared as a protector of Sherbro interests: he readily acknowledged his Temne identity, but positioned himself as a Sherbro citizen opposed to the new headman, who was supported by migrants. This shows the possibility of claiming two ethnic identities, one related to ethnic roots and the other to the notion of local citizenship. The former identity is ascribed. The latter identity is both ascribed through female ancestorship and achieved by demonstrating one’s commitment to Sherbro ‘culture’, including Poro ritual practice, and by protecting Sherbro interests and leadership in a context of political tensions with immigrants. Oral traditions described customary ways of acquiring Sherbro identity and citizenship rights, which was set against migrants’ conceptualization of citizenship as attached to one’s identity as a Sierra Leonean national and to the rights granted by the state across the national territory (see Bräuchler & Ménard, Citation2017).

This example reveals the fluidity of identity ascriptions as grounded in collective representations about integration. At first sight, oral traditions, such as the one collected in Tokeh, tended to present the audience with a discourse of exclusion that is supported by past tensions and by the description of Temne behaviour as non-accommodative and disrespectful of Sherbro authority. At the same time, such historical narratives subtly introduced norms of integration that referred to a local conceptualization of reciprocity between groups. Some ‘strangers’ or descendants of ‘strangers’ assumed both Temne ethnic roots and Sherbro ancestorship and stressed a process of ‘standard integration’, by which they had become Sherbro over generations. While the emphasis on matrilineal ties facilitates the integration of newcomers and their children, social identities are constantly fluctuating: individuals, regardless of origin, must demonstrate their commitment to the criteria of Sherbro identity over time. ‘Success stories’ of integration thus rest on a long-term assessment of the ability of newcomers to abide by local rules and to become Sherbro in this specific way. Integration, in that sense, remains an ambiguous process related to individual skills.

Conclusion

In a region characterized by population movements, Sherbro oral traditions refer to historical patterns of settlement and subsequent socioeconomic and political interactions between groups. They reflect the ambivalence of local populations towards settlers: Sherbros use oral traditions to claim autochthony, but also to draw a model of integration situated in an idealized past, in which the socioeconomic, political and demographic conditions were reunited for newcomers to integrate into local communities. Integration through sociocultural assimilation is set against patterns of separated communities and economic competition. Integration and reciprocity are understood as two sides of the same coin: in exchange for land and economic and political rights provided by hosts, strangers have to acquire the attributes of Sherbro identity in specific ways. Sherbros thus interpret their conflict with Temne settlers as a consequence of the non-respect by the latter of local norms of reciprocity. The kinship idiom used in oral traditions with regard to Temne immigrants implies a fear of losing one’s status and authority as a host group. Therefore, oral traditions tell the audience which strangers can or cannot be trusted based on historical precedents and emphasize that the initial social arrangements with Temnes were precarious.

Oral traditions also point to a key aspect of the host/stranger relationship, namely the possibility to become a member of another ethnic group, which mainly depends on the commitment of newcomers and their children to that new identity. Although recent immigrants contest that form of integration, it gives insights into the long-term basis of the conflict and the way people interpret it. Reciprocity and integration are key notions of social life that permeate conflict. In this case, social conflict needs to be historicized and understood with reference to a continuum of social relationships in which norms of reciprocity continue to be relevant. Reciprocity and its contemporary social value need to be analysed as part of a larger system in which actors operate over a long period of time. In the post-war environment, which is economically and socially insecure, historical narratives about integration and its related social practices are reactivated in order to make sense of current immigration and concomitant social diversity and change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Population numbers are unreliable, but the office of Statistics Sierra Leone provided the author with data from the 2004 census, which show that Goderich and Tombo had more than 20,000 inhabitants and Tokeh about 15,000 inhabitants. This represents an important change compared to the pre-war period.

2. Sherbros, who constitute a minority ethnic group, claim an autochthonous status in many coastal towns, but not in those founded by the liberated slaves, such as York and Kent. Those are referred to as Krio settlements (Krio vilej).

3. The main Sherbro fishing gear is the Kru-canoe, a one-man paddle canoe used for hook-and-line fishing.

4. See Højbjerg (Citation1999), Lentz (Citation2006) and Murphy and Bledsoe (Citation1987).

5. Throughout the text, I use the terms host(s) and stranger(s) with reference to this specific theoretical model.

6. This system emerged during the precolonial period, as long-distance trading networks connected different societies (Knörr & Trajano Filho, Citation2010, p. 9; Shack, Citation1979, p. 40). Strangers paid taxes and tribute to the landlord (see Mouser, Citation1975). As Shack and Skinner (Citation1979, p. 8) argue, payment ‘gave symbolic recognition to the superior social and political position of hosts’. According to the logics of patronage, conflict may have emerged when groups of strangers sought autonomy, competed for resources or when landlords failed to redistribute wealth (Knörr & Trajano Filho, Citation2010, p. 10). Yet, beyond a patron–client relationship, strangers became part of the host group’s social system and their position was not fixed.

7. The civil war itself did not play out along ethnic lines. Although neopatrimonialism and ethnic clientelism were surely a critical factor in the decline of the state, the revolutionary movement that broke out cut across ethnic lines.

8. Although customary law is not legally recognized on the Peninsula, customary land rights still prevail at a local level.

9. In describing various scenarios of land-related conflicts, Boone (Citation2013, p. 195, italics in the original) argues that ‘where high in-migration has taken place under state sponsorship (statist land regime), rising competition for land will find political expression in tension between state-sponsored settlers and indigenes. … Central authorities can be expected to back those they have settled on the land – in other words, settlers with whom they have patron–client relations.’

10. This includes migration from the Sherbro coast to the south and the Bullom shore to the north.

11. By contrast, Sherbros stress their close relations with the Ghanaian fishermen. Historical narratives mentioned acts of Sherbro bravery by which Sherbros warned Ghanaians of government patrols and hid them in their house. Hence, Sherbros emphasize their dislike of Temne fishermen also by referring to a history of Ghanaian/Temne conflict.

12. This analysis only concerns in-marrying men. More research would be needed concerning patterns of integration for in-marrying female immigrants and the possibility for them to acquire a new ethnic identity.

13. In Krio, the difference between settlers and strangers appears through the use of the possessive: ‘I na strenja’ (S/he’s a stranger/foreigner) differs from ‘I/den na wi strenja/dem’ (He is our stranger, they are our strangers).

14. The conflict between practitioners of Islam and practitioners of local religions, as embodied by secret societies, is a long-standing one. Yet, the conflict on the Peninsula accentuated after the war, as the presence of migrants has prevented local populations from organizing initiation and other ritual practices related to secret societies (Ménard, Citation2017).

15. In Krio, the terms used to express this social distinction are civilayzd (civilised) vs. netiv or kɔntri (native).

16. The autochthonous status of Krios, due to their slave ancestry, has been often contested by other groups. Temne and Krio/Sherbro populations have also long argued as to whom the Peninsula really belongs to. As the British acquired the territory from Temne chiefs, Temne often claimed the Peninsula to be part of Koya chiefdom to the north-east.

17. In Guinea, Sarró (Citation2010, p. 239) also shows that becoming Baga is intimately related to the process of initiation.

References

- Bedert, M. (2017). The complementarity of divergent historical imaginations: Narratives of mobility and alterity in contemporary Liberia. Social Identities. doi:10.1080/13504630.2017.1281467

- Berliner, D. (2010). The invention of Bulongic identity (Guinea-Conakry). In J. Knörr & W. T. Filho (Eds.), The powerful presence of the past: Integration and conflict along the upper Guinea coast (pp. 253–271). Leiden: Brill.

- Bolten, C. E. (2012). I did it to save my life: Love and survival in Sierra Leone. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Boone, C. (2013). Land regimes and the structure of politics: Patterns of land-related conflict. Africa, 83(1), 188–203. doi: 10.1017/S0001972012000770

- Bräuchler, B. (2017). Changing patterns of mobility, citizenship and conflict in Indonesia. Social Identities. doi:10.1080/13504630.2017.1281468

- Bräuchler, B., & Ménard, A. (2017). Patterns of im/mobility, conflict and the re/making of identity narratives. Social Identities. doi:10.1080/13504630.2017.1281418

- Brooks, G. E. (1993). Landlords and strangers: Ecology, society, and trade in Western Africa, 1000–1630. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Day, L. R. (1983). Afro-British integration on the Sherbro Coast 1665–1795. Africana Research Bulletin, XII(3), 82–107.

- Diggins, J. (2015). Economic runaways: Patronage, poverty and the pursuit of ‘freedom’ on Sierra Leone’s maritime frontier. Africa, 85(2), 312–332. doi: 10.1017/S0001972014001041

- Dorjahn, V. R., & Fyfe, C. (1962). Landlord and stranger: Change in tenancy relations in Sierra Leone. The Journal of African History, 3(3), 391–387. doi: 10.1017/S0021853700003315

- Geschiere, P. (2009). The perils of belonging. Autochthony, citizenship, and exclusion in Africa and Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Geschiere, P., & Jackson, S. (2006). Autochthony and the crisis of citizenship: Democratization, decentralization, and the politics of belonging. African Studies Review, 49(2), 1–7. doi: 10.1353/arw.2006.0104

- Hendrix, M. K. (1984). Technical change and social relations in a West African maritime fishery: A development history. ICMRD Working Paper 21. Kingston: International Center for Marine Resource Development, University of Rhode Island.

- Hoffer, C. P. (see MacCormack) (1971). Acquisition and exercise of political power by a woman paramount chief of the Sherbro people (Dissertation), Bryn Mawr College, Ann Arbor, Mich.

- Højbjerg, C. K. (1999). Loma political culture: A phenomenology of structural form. Africa, 69, 535–554. doi: 10.2307/1160874

- Højbjerg, C. K. (2007). Resisting state iconoclasm among the Loma of Guinea. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

- Hornell, J. (1928). The indigenous fishing methods of Sierra Leone. Sierra Leone Studies, 13, 10–16.

- Knörr, J., & Trajano Filho, W. (Eds.). (2010). The powerful presence of the past: Integration and conflict along the upper Guinea coast. Leiden: Brill.

- Kotnik, A. (1981). A demographic and infrastructural profile of the Tombo fishing village in Sierra Leone. Fisheries Pilot Project, Tombo. Freetown: GTZ.

- Krabacher, T. S. (1990). Fishing, food, and change along the Sherbro Coast of Sierra Leone (Dissertation), University of California, Ann Arbor, Mich.

- Lentz, C. (2006). First-comers and late-comers: Indigenous theories of land ownership in the West African Savanna. In R. Kuba & C. Lentz (Eds.), Land and the politics of belonging in West Africa (pp. 35–56). Leiden: Brill.

- Lund, C. (2002). Negotiating property institutions: On the symbiosis of property and authority in Africa. In K. Juul & C. Lund (Eds.), Negotiating property in Africa (pp. 11–43). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- MacCormack, C. P. (1979). Wono: Institutionalized dependency in Sherbro descent groups (Sierra Leone). In S. Miers & I. Kopytoff (Eds.), Slavery in Africa. Historical and anthropological perspectives (pp. 181–203). Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Ménard, A. (2015). Beyond autochthony discourses: Sherbro identity and (re-)construction of social and national cohesion in Sierra Leone (Dissertation), Martin-Luther Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Halle/Saale.

- Ménard, A. (2017). Poro society, migration, and political incorporation on the Freetown Peninsula, Sierra Leone. In C. K. Højbjerg, J. Knörr, & W P. Murphy (Eds.), Politics and policies in Upper Guinea Coast societies. Change and continuity (pp. 29–52). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mouser, B. L. (1975). Landlords-strangers: A process of accommodation and assimilation. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, 8(3), 425–440. doi: 10.2307/217153

- Murphy, W. P. (1980). Secret knowledge as property and power in Kpelle society: Elders versus youth. Africa, 50, 193–207. doi: 10.2307/1159011

- Murphy, W. P., & Bledsoe, C. H. (1987). Kinship and territory in the history of a Kpelle chiefdom (Liberia). In I. Kopytoff (Ed.), The African Frontier: The reproduction of African traditional societies (pp. 123–147). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- O’Kane, D., & Ménard, A. (2015). The frontier in Sierra Leone: Past experiences, present status, and future trajectories (Working Paper No. 162).

- Sarró, R. (2010). Map and territory: The politics of place and autochthony among baga sitem (and their Neighbours). In J. Knörr & W. T. Filho (Eds.), The powerful presence of the past: Integration and conflict along the upper Guinea coast (pp. 231–252). Leiden: Brill.

- Schneider, D. M. (1961). Introduction: The distinctive features of matrilineal descent groups. In D. M. Schneider & K. Gough (Eds.), Matrilineal kinship (pp. 1–32). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Shack, W. A. (1979). Open systems and closed boundaries: The ritual process of stranger relations in New African States. In W. A. Shack & E. P. Skinner (Eds.), Strangers in African societies (pp. 37–50). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Shack, W. A., & Skinner, E. P. (Eds.). (1979). Strangers in African societies. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Tonkin, E. (1986). Investigating oral tradition. The Journal of African History, 27(2), 203–213. doi: 10.1017/S0021853700036641

- Trajano Filho, W. (2010). The creole idea of nation and its predicaments: The case of Guinea-Bissau. In J. Knörr & W. T. Filho (Eds.), The powerful presence of the past: Integration and conflict along the upper Guinea coast (pp. 257–284). Leiden: Brill.

- Vansina, J. (1985). Oral tradition as history. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.