?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper provides a meta-analysis of the impact of business formalization on performance. We exploit a meta-dataset of 1,271 estimates derived from 20 studies available until October 2019. The analysis reveals that formalization is associated with fairly small benefits that take time to materialize. We then exploited the difference between policy-induced formalization and self-induced formalization investigating underlying effects, publication bias, and sources of heterogeneity. Policy-induced formalization brings large benefits, whereas self-induced formalization only results in medium benefits, suggesting that indeed formalization can be spurred by adequate policy actions. To be most effective, formalization policies should be implemented with information sessions, trainings/workshops, and business development services to unleash the growth potential of newly formalized firms in the most potent way.

I. Introduction

Informal firms represent the most micro and small enterprises in developing countries. Their relevance for the private sector and potential contribution to economic growth induce governments and policymakers to take actions promoting the formalization of informal enterprises.

Despite such efforts, policies fostering business formalization do not seem to achieve the expected transformation (Floridi, Demena, and Wagner Citation2020). If formalization policies have limited impacts, it is not clear whether those firms opting for formalizing actually gain advantages from switching status. A popular view is that enterprises take decisions concerning business formalization based on the costs and benefits associated with formality (Maloney Citation2004). If business registration is the result of a cost-benefit analysis, limited advantages associated with formalization may explain the resilience of informal entrepreneurs and the limited effects of formalization policies.

Thus, a crucial question for development studies and policymakers is whether firms benefit from formalizing their business. To address this question, a rapidly growing empirical literature investigates the effects of formalization on firms switching formality status. The existing studies represent two strands of literature – results from policy-induced actions via reforms and field experiments, and self-induced formalization independent of external interventions. The evidence gathered by now is far from being conclusive. Studies report heterogeneous findings, analyse the effects on various performance indicators, and employ different econometric models and specifications.

This study uses meta-regression analysis (MRA) to synthesize the empirical literature and consolidate the available evidence. The analysis exploits the difference between policy-induced and self-induced formalization, identifying the respective genuine effects, publication bias, and other sources of heterogeneity. We believe that this exercise is timely given the reported heterogeneity of the findings. Moreover, this study provides useful insights for policymaking, as it allows to assess whether formalization policies are to some extent successful, at least in terms of improving business performance.

Whilst meta-analyses have been carried out in several areas of economics and business management (Tingvall and Ljungwall Citation2012; Demena Citation2015), few reviews and meta-analyses explore the impact of policy actions on business formalization (Floridi, Demena, and Wagner Citation2020). To the best of our knowledge, there are no meta-analyses investigating firm performance induced by formalization.

II. Methodology

Search and selection strategies

We searched Google Scholar, Scopus, and World Bank Knowledge Retrieve and employed forward and backward search to retrieve potential empirical studies. Searching for eligible studies was a challenging task as the formality and business performance literature is abundant. For instance, the keywords ‘Benefit of formalization informal firms’ in Google Scholar hit more than 55,000 results. Therefore, we split the queries into two main categories: formality and performance indicators. The formality indicators were formalization, registration, and licence. For the outcomes, we selected the most common performance indicators: revenues, profits, credit, input, and tax payment. We combine the two categories with ‘AND’ to obtain a narrower web search.

Two authors separately conducted the multiple searches (June 2018 to October 2019). We inspected English language studies reporting regression-based results, focusing on formalization impacts on business performances and comparing firms before and after switching formality status to non-switchers. We conducted a two-stage screening process: the first stage identified 47 studies based on screening titles, abstracts and conclusions, whilst the second stage excluded 27 studies after analysing the potential studies in detail. We excluded studies that do not focus on enterprises switching formality status, investigate treatment effects on the performance of informal enterprises, and/or do not employ regression analysis. Eventually, we selected a sample of 20 empirical studies. The list of papers included in the meta-analysis can be found in the references indicated with a star.

Meta-dataset

The analysis exploits a meta-dataset of 1,271 estimates from 20 studies. The average and median number of estimates per study are 63.5 and 39, respectively. The oldest study is published in 2011, and the most recent in 2019. Thus, the empirical literature started recently investigating the effects of formalization. Specifically, 14 of the studies are from the period 2015–2019, indicating that this is an emerging topic fraught with mixed results and a steadily increasing evidence based.

We include 9 peer-reviewed and 11 unpublished studies. Eleven studies (704 estimates) assess policy-induced and 9 studies (567 estimates) self-induced formalization. Regarding performance indicators, roughly half the estimates capture revenues and sales (46%), followed by access to credit (16%), and access to inputs (9%). Other indicators are employment and tax payment. provides a detailed description of the meta-dataset.

Table 1. Definition and descriptive statistics

Empirical approach

We design the empirical approach in three steps. The first-stage presents arithmetic and weighted averages. We first apply partial correlation coefficients (PCC) to ensure comparison across the studies. We compute PCCs as:

where represents the partial correlation coefficient between firms switching status (formalization) and performance indicators, r denotes the reported estimate from primary study s,

and df are t-value and the regression’s degrees of freedom.

The second-step uses visual inspection and bivariate MRA. The former uses funnel plots to visually inspect publication bias and the latter performs the Funnel Asymmetry Test (FAT) and Precise Estimates Test (PET) to investigate the regression-based publication bias and genuine effect.

The third-step uses a multivariate MRA exploring potential sources of heterogeneity. We use the General-to-specific (G-to-S) approach on the full sample and then analyse the two sub-samples, policy-induced and self-induced, separately. We estimate the multilevel mixed effects (MEM) model using precision as weight as it addresses both inter- and intra-study dependencies. We use Doucouliagos (Citation2011) for interpreting the PCC results (small, medium, and large between 0.07 and 0.173, 0.173 and 0.327, and above 0.327, respectively).

III. Findings and discussion

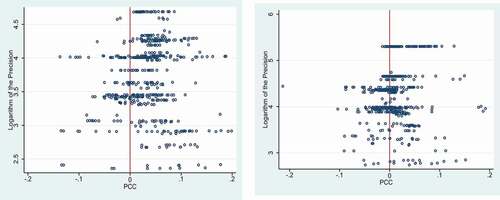

presents the arithmetic and weighted averages. The overall average effect greatly varies – self-induced formalization has more than double the effect compared to policy-induced formalization. All averages are positive and statistically significant. However, we need to account potential sources of bias and heterogeneity. depicts two funnel plots, providing the first indication of publication bias. Close inspection seems to indicate slight asymmetries. provides the related bivariate FAT-PET findings. We find very small and similar underlying effects and no systematic publication bias (though downward bias for policy-induced formalization). Thus, on average firms do not benefit from formalization.

Table 2. Average impact of formality on performance

Table 3. Bivariate MRA: Publication bias and genuine effect tests

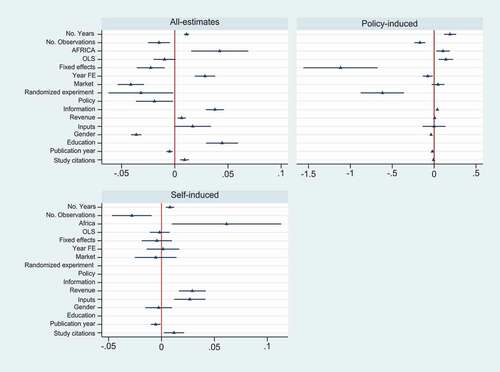

To assess whether the bivariate FAT-PET results are influenced by study heterogeneity, and present the multivariate MRA. The multivariate MRA (all-estimates) identifies a small underlying effect (0.140) and insignificant publication bias, suggesting formalization benefit firms by improving revenues and access to services. Though the effect is small, this finding supports the view of informality as an incubator for firms, with formalization benefits arising after a trial stage in the informal sector (Williams, Martinez–Perez, and Kedir Citation2017). Further analysing the two sub-samples with policy-induced and self-induced effects, policy reforms display a systematically larger PCC (1.643) and a substantial downward publication bias which is statistically significant; on the other hand, self-induced formalization results in medium effects (0.246) and negative albeit statistically insignificant bias. Thus, after accounting for study heterogeneity, policy-induced formalization seems to benefit the newly formalized firms.

Table 4. Multivariate MRA

Concerning drivers of heterogeneity (), policies accompanied by information sessions seem more effective, indicating the importance of informational face-to-face meetings. Thus, formalization policies should be implemented with information sessions, trainings/workshops, and bank sessions if they want to effectively unleash the growth potential of newly formalized firms. Revenues appear the main channel through which firms benefit from both policy-induced and self-induced formalizations. Additionally, self-induced formalization is associated with improved access to inputs.

Other sources of heterogeneity are common in both sub-samples (). For instance, more years of data period results in better business performance, implying that time is needed for benefits to materialize as firms initially recover the immediate costs of formalization. Given that the majority of the policies (9 out of 11) cut the costs of registration, it is plausible that firms formalize due to the low extensive costs of switching status. However, they require time to overcome the intensive costs of formality, which are higher for less productive newly formalized firms (Ulyssea Citation2018). Larger samples detect lower effects, implying that increasing the study population decreases the detected benefits. This suggests that selection bias declines with larger samples and a better representation of the heterogenous informal enterprises

Although overall formalization only brings modest advantages to firms, the bright side of policy-induced formalization is that firm performance is further reinforced.

IV. Conclusions

Overall, we show that formalization brings small advantages to firms. Yet, effects need time to materialize which might be explained by the high intensive costs of formalization. After breaking the sample in two groups, the analysis reveals that policy-induced formalization is associated with high benefits whereas self-induced formalization with medium advantages. Particularly effective are those interventions accompanied by informational sessions. Policy strategies providing training and business services can generate more benefits compared to policies simply cutting the costs of formalization. Future research should investigate potential benefits for governments from providing such a comprehensive formalization framework.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alcázar, L., and M. Jaramillo. 2016. “The Impact of Formality on Microenterprise Performance: A Case Study in Downtown Lima. GRADE Group for the Analysis of Development. Lima, Peru. *

- Benhassine, N., D. McKenzie, V. Pouliquen, and M. Santini. 2018. “Does Inducing Informal Firms to Formalize Make Sense? Experimental Evidence from Benin.” Journal of Public Economics 157: 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2017.11.004.*

- Berkel, H. .2018. The costs and benefits of formalization for firms: A mixed-methods study on Mozambique Working Paper N° 159. World Institute for Development Economic Research (UNU-WIDER). *

- Bich, T. T., and H. A. La. 2018. “Why Do Household Businesses in Viet Nam Stay Informal?” WIDER Working Paper N° 2018/64. *

- Boly, A. 2015. “On the Benefits of Formalization: Panel Evidence from Vietnam.” Working Paper N° 2015/038. Helsinki: UNU WIDER. *.

- Boly, A. 2018. “On the Short-and Medium-term Effects of Formalisation: Panel Evidence from Vietnam.” Journal of Development Studies 54 (4): 641–656. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1342817.*

- Campos, F., M. Goldstein, and D. McKenzie. 2015. Short-term impacts of formalization assistance and a bank information session on business registration and access to finance in Malawi. *

- Campos, F., M. Goldstein, and D. McKenzie. 2018. “How Should the Government Bring Small Firms into the Formal System? Experimental Evidence from Malawi.” Policy Research Working Paper N° 8601. Washington DC: World Bank Group. *

- Campos, F., M. Goldstein, and D. McKenzie. 2019. The Impacts of Formal Registration of Businesses in Malawi, 3ie Grantee Final Report. New Delhi: International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie). *

- De Mel, S., D. McKenzie, and C. Woodruff. 2011. What Is the Cost of Formality? Experimentally Estimating the Demand for Formalization. Mimeo. *

- De Mel, S., D. McKenzie, and C. Woodruff. 2013. “The Demand For, and Consequences Of, Formalization among Informal Firms in Sri Lanka.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5 (2): 122–150. *

- Demena, B. A. 2015. “Publication Bias in FDI Spillovers in Developing Countries: A Meta-regression Analysis.” Applied Economics Letters 22 (14): 1170–1174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2015.1013604.

- Demenet, A., M. Razafindrakoto, and F. Roubaud. 2016. “Do Informal Businesses Gain from Registration and How? Panel Data Evidence from Vietnam.” World Development 84: 326–341. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.09.002.*

- Doucouliagos, H. 2011. How Large Is Large? Preliminary and Relative Guidelines for Interpreting Partial Correlations in Economics (WP 2011-5). Geelong, Victoria: Deakin University.

- Fajnzylber, P., W. F. Maloney, and G. V. Montes-Rojas. 2011. “Does Formality Improve Micro-Firm Performance? Evidence from the Brazilian SIMPLES Program.” Journal of Development Economics 94 (2): 262–276. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.01.009.*

- Floridi, A., B. A. Demena, and N. Wagner. 2020. “Shedding Light on the Shadows of Informality: A Meta- Analysis of Formalization Interventions Targeted at Informal Firms.” Labour Economics 67: 101925. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2020.101925.

- Gabrieli, T., and G. A. F. Montes-Rojas. 2011. “Who Benefits from Reducing the Cost of Formality? Quantile Regression Discontinuity Analysis.” In Informal Employment in Emerging and Transition Economies. 101–133. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. *

- Maloney, W. F. 2004. “Informality Revisited.” World Development 32 (7): 1159–1178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.01.008.

- McCaig, B., and J. Nanowski. 2018. “Business Formalization in Vietnam.” Working Paper. *

- McCaig, B., and J. Nanowski. 2019. “Business Formalisation in Vietnam.” Journal of Development Studies 55 (5): 805–821. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2018.1475646.*

- Rand, J. 2017. “Comparing Estimated and Self-reported Mark-ups for Formal and Informal Firms in an Emerging Market Context.” WIDER Working Paper N° 2017/160. *

- Rand, J., and N. Torm. 2012. “The Benefits of Formalization: Evidence from Vietnamese Manufacturing SMEs.” World Development 40 (5): 983–998. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.09.004.*

- Rocha, R., G. Ulyssea, and L. Rachter. 2014. Do Entry Regulation and Taxes Hinder Firm Creation and Formalization. Evidence from Brazil. Working Paper. *

- Rocha, R., G. Ulyssea, and L. Rachter. 2018. “Do Lower Taxes Reduce Informality? Evidence from Brazil.” Journal of Development Economics 134: 28–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.04.003.*

- Tingvall, P. G., and C. Ljungwall. 2012. “Is China Different? A Meta-analysis of Export-led Growth.” Economics Letters 115 (2): 177–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2011.11.028.

- Ulyssea, G. 2018. “Firms, Informality, and Development: Theory and Evidence from Brazil.” American Economic Review 108 (8): 2015–2047. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20141745.

- Williams, C. C., A. Martinez–Perez, and A. M. Kedir. 2017. “Informal Entrepreneurship in Developing Economies: The Impacts of Starting up Unregistered on Firm Performance.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41 (5): 773–799. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12238.