?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to investigate whether social connectedness can mitigate the fiscal common pool problem in municipal mergers, as many studies have primarily focused on whether this problem occurs. I employ the synthetic control method by using higher-level government borders to identify the moderating effects of social connectedness. The findings reveal that subordinate partners in cross-prefectural border mergers significantly reduce their bonds and construction expenses just before the mergers. Merger partners with strong incentives to merge do not create fiscal common pool problems, which is the opposite of previous studies. The result might imply the potential effectiveness of merger support policies that prioritize social connectedness.

I. Introduction

Many studies investigate the fiscal common pool problem of municipal mergers (e.g. Blom-Hansen Citation2010; Fritz and Feld Citation2020; Goto, Sekgetle, and Kuramoto Citation2021; Hansen Citation2014; Hinnerich Citation2009; Hirota and Yunoue Citation2017, Citation2020; Jordahl and Liang Citation2010; Nakazawa Citation2016; Saarimaa and Tukiainen Citation2015). The fiscal common pool problem is related to the free-rider problem based on the concept of the law of . Both public project and bond size tend to increase with a common pool size just before mergers because merged municipalities expect to share their fiscal burden after mergers and to be able to free-ride.Footnote1 In Japan’s case, Hirota and Yunoue (Citation2017, Citation2020) reveal that subordinate merger partners rapidly increase their construction expenses and bond issuances just before mergers, although those of the dominant merger partners decrease or do not increase.

The purpose of this paper is to investigate whether social connectedness, including historical, economic, and geographical ties, can mitigate the fiscal common pool problem in municipal mergers. Many studies have focused on whether the common pool problem occurs. Bhatti and Hansen (Citation2011) emphasize the significance of social connectedness in the context of municipal mergers. In the case of heterogeneous merged municipalities, one would anticipate greater welfare losses. Moreover, there are relatively few studies that explore ways to prevent the common pool problem. For example, Askim and Houlberg (Citation2022) reveal the moderating effects of social norms just before mergers.

In this paper, my focus is on cross-prefectural border municipal mergers in Japan, and I employ the synthetic control method by using higher-level government borders to identify the moderating effects of social connectedness. In many merger cases, municipalities choose neighbouring partners within the same higher-level governments because they expect to receive support including subsidies from these higher-level governments. Given the similarity of social connectedness among merged municipalities, it is not easy to reveal whether social connectedness mitigate the fiscal common pool problem just before mergers. To identify ways to mitigate the fiscal common problem in quasi-experimental approaches, the cross-prefectural border merger case provides a more suitable approach, aligning with the literature on social connectedness. From an identification strategy perspective, the synthetic control method is capable of generating appropriate counterfactuals, especially when dealing with a single treated unit.

This paper is organized as follows. Section II describes the background of Japan’s municipal mergers. Section III presents the empirical framework and results. Section IV concludes.

II. Background

In Japan, there are three layers of administrative systems: the central government and prefectural and municipal governments. Prefectures and municipalities are both local public entities that collaborate in local administration based on their respective roles and responsibilities. Prefectures serve as regional authorities that encompass municipalities and oversee broader regional administration. Each municipality falls within a specific prefecture.

The central government enacted the Special Municipal Mergers Law, which has been called a carrot-and-stick policy, to induce a large number of municipal mergers in FY1999.Footnote2 The law provided that if municipalities decided to merge up to FY2005, the merged municipalities would receive special fiscal or other support from the central government, such as local allocation tax (LAT) grants, subsidies, and bonds.Footnote3 In contrast, for municipalities that decided not to merge, their grants, subsidies, and others would decrease.

Prefectures played many roles in the process of municipal mergers, including creating combinations of merger partners, establishing subsidies for mergers, setting up support headquarters, and dispatching prefectural staff, all based on national guidelines (e.g. Goto Yasuda Kinen Tokyo Toshi Kenkyusho Citation2013; Hirota and Yunoue Citation2014). Most prefectures adhered to the national guidelines for promoting municipal mergers. The reason is that many prefectures depend on intergovernmental transfers from the central government. During the period from FY1999 to FY2005, the number of municipalities decreased from 3,232 to 1,820.

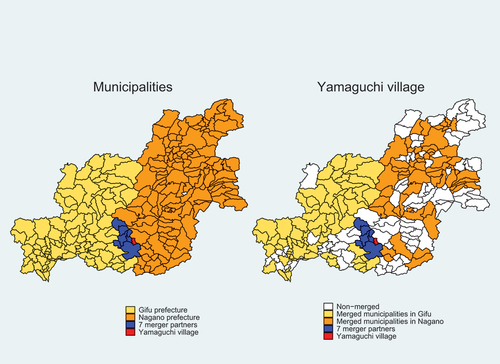

All merged municipalities chose to merge with neighbouring municipalities within the same prefectures except in one merger case.Footnote4 The reason is that there are not only cultural connectedness but also administrative or fiscal interrelationships between prefectural and municipal governments, embodied in links such as personnel exchange, intergovernmental transfers from prefectural government, and public projects. However, Yamaguchi village in Nagano Prefecture decided to merge with Nakatsugawa city in Gifu Prefecture in FY2004. shows the map of both Gifu and Nagano prefectures. The sole cross-prefectural merger case was Yamaguchi village in Nagano Prefecture. Nakatsugawa city was the dominant merger partner, with the largest population size in Gifu at 55,477 people in FY2003. The other six towns and villages in Gifu (Sakashita town, Kawakami village, Kashimo village, Tsukechi village, Fukuoka town, and Hirukawa village) were subordinate merger partners that had smaller population sizes, at less than one-fifth the size of the dominant merger partner. Yamaguchi village in Nagano Prefecture historically had an intense connection to Nakatsugawa city in Gifu Prefecture. In FY1958, Misaka village in Nagano decided to merge with Nakatsugawa city in Gifu across the prefectural border. Yamaguchi district in Nagano, which is a part of Misaka village in Nagano, did not merge, while the other three districts of Misaka village decided to merge with Nakatsugawa. According to the opinion survey of residents in FY2001, over seventy percent of residents hoped to merge with Nakatsugawa city across the prefecture’s border (e.g. Kitazaki Citation2005). Fiscal simulations by the Yamaguchi village government revealed better conditions under such a merger than under other potential mergers with neighbouring municipalities in Nagano. However, the Nagano prefectural mayor had a negative attitude towards the merger. Yasuo Tanaka, the prefectural mayor, first rejected the cross-prefectural merger proposal, but later allowed the merger after consulting with the minister of Internal Affairs and Communications.

III. Empirical framework and results

Synthetic control method

To reveal the fiscal common pool problem under cross-prefectural municipal mergers, I apply the synthetic control method developed by Abadie and Gardeazabal (Citation2003) and Abadie, Diamond, and Hainmueller (Citation2010, Citation2015). The method is to generate synthetic control values for a treated unit by calculating the weighted average of untreated control units from a donor pool. The method can consider time-varying confounding when there is a close fit between the treated and synthetic control paths and is similar to a combination of the matching and difference-in-differences methods. In detail, the pretreatment root mean square prediction error (RMSPE) of the treated outcomes and the counterfactual pretreatment outcomes are minimized as follows:

where is the observed outcome of unit

in pretreatment period

.

is the counterfactual outcome of

in period

, given by the weighted average of untreated units from the donor pool. Suppose that

and

. The counterfactual weights

chosen by the RMSPE are minimized (e.g. Abadie Citation2021; Gilchrist et al. Citation2022).

This paper employs the eight merged municipalities as treated units. Nakatsugawa city decided to merge with seven towns and villages of Gifu and Nagano prefectures in FY2004. The main treated unit in this paper is the cross-prefectural merger partner, Yamaguchi village in Nagano prefecture. In this merger case, Nakatsugawa city is the dominant partner. The other six towns and villages in Gifu and Yamaguchi village in Nagano are subordinate partners. According to Hirota and Yunoue (Citation2017), subordinate partners rapidly increase their bonds, total expenditure, and construction work expenses a few years before mergers. This paper sets the treatment period from FY2001 to FY2003. The period in which the RMSPE should be minimized is from FY1980 until FY2000. Additionally, this paper employs 88 nonmerged municipalities in both Gifu and Nagano prefectures for the donor pool to calculate the synthetic control values.Footnote5

The main outcome variables are per capita bonds, total expenditure, and construction work expenses, following previous papers. Additionally, I employ the per capita prefectural subsidies because the different prefecture’s policies might affect the cross-prefectural partner’s behaviour. As predictors, I employ the population; the share of the population under 15; the share of the population over 65; the shares of the primary and tertiary industries; the shares of LAT grants, central subsidies, and prefectural subsidies in total revenue; and per capita accumulated debts. These predictors are almost the same as those in previous papers (e.g. Hirota and Yunoue (Citation2017, Citation2020)). This paper uses Japan’s municipal data from FY1980 to FY2003, excluding the data from FY1981 to FY1984 due to data unavailability. The data on municipal governments are derived primarily from the Statistics of the Final Accounts of Municipal Governments, Survey on the Basic Register of Residents, and Population Census. shows summary statistics of the cross-prefectural partner and donor municipalities.

Table 1. Summary statistics.

Empirical results

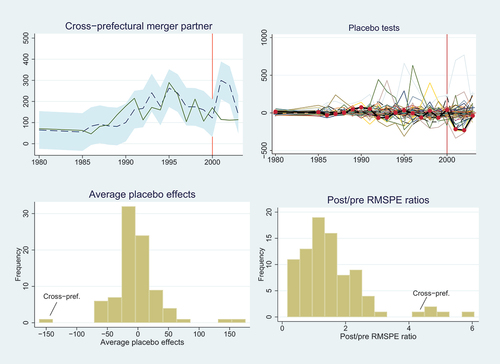

shows the results of the per capita bonds of the cross-prefectural partner, that is, Yamaguchi village in Nagano Prefecture. Additionally, I apply the placebo tests suggested by Abadie, Diamond, and Hainmueller (Citation2010, Citation2015). The placebo tests calculate the synthetic control of each municipality in the donor pool one by one, excluding the real treated units. The average placebo effects show the average gap between the placebo-treated units and synthetic control values. Moreover, the post/pre RMSPE ratios show the ratios of the post RMSPE to the pre RMSPE. The higher ratios indicate that the treated values are largely different from the synthetic control values in the posttreatment period.

The top left side of the figure shows the results of both the treated and the synthetic control values. The colour part of the synthetic control values is the 95% confidence interval.Footnote6 The bonds of the cross-prefectural partner are lower than the synthetic control values and are outside the 95% confidence interval. The cross-prefectural partner decreases its bonds just before the merger. The result is the opposite of findings from previous papers. The top right side of the figure shows the placebo tests that show the differences between the placebo-treated and synthetic control values. The cross-prefectural partner’s bonds decrease in the posttreatment period, while there are no differences in the pretreatment period. The bottom left side shows the average placebo effects that indicate the average gaps between the placebo-treated and synthetic control values. The cross-prefectural partner clearly decreases its bond issuances in the posttreatment period. Moreover, the bottom right side shows the histogram of the post/pre RMSPE ratios.

(note) The outcome variable is the per capita bonds of the cross-prefectural merger partner. The monetary unit is 1 million Japanese yen, which is approximately 10,000 dollars at an exchange rate of 100 yen to 1 US dollar. The colour part of the synthetic control units is the 95% confidence interval. ‘Average placebo effects’ are the average gaps of both the placebo-treated and placebo synthetic values. ‘Post/pre RMSPE ratios’ are the ratios of the post RMSPE to pre RMSPE. The post/pre RMSPE ratio of the cross-prefectural partner is 4.222, which has the fifth-highest ratio out of 89 municipalities with a p value of 0.058 ( = 5th/89 units).

shows the summary results of the synthetic control method on bonds. The average gap shows the average gap between the treated and synthetic control values. The average gap of the cross-prefectural partner is approximately −157.62 million Japanese yen, and the average gap ratio is approximately −52.8%. The bond reduction rate is largely higher than that of other treated units, including the dominant partner and other subordinate partners in Gifu Prefecture.

Table 2. Summary results of bonds.

shows the summary results of additional outcomes, including per capita total expenditure, construction work expenses, and prefectural subsidies. Regarding total expenditure, the average gap ratio is approximately −17.6%. Regarding construction work expenses, the average gap ratio is approximately −48%. The cross-prefectural character of the merger prevents the occurrence of the fiscal common pool problem under municipal mergers. This result differs from the findings of previous studies. The average gap ratio of per capita prefectural subsidies is −51.5%. The rate of reduction in prefectural subsidies is higher for the subordinate partners in cross-prefectural mergers than for other partners.

Table 3. Summary results of additional outcomes.

IV. Conclusion

This paper investigates whether social connectedness can mitigate the fiscal common pool problem in municipal mergers. I reveal that the subordinate partners in cross-prefectural border mergers clearly decrease their bonds and construction work expenses just before the mergers. The result is the opposite of findings from previous studies.

In Japan’s case, all merged municipalities chose to merge through the carrot-and-stick policy combining fiscal support or the reduction of intergovernmental transfers from the central government. However, the cross-prefectural border partner decreases their bonds and construction works just before the mergers. The cross-prefectural border partner might place great emphasis on social connectedness including historical, economic, and geographical connectedness. The result might imply the potential effectiveness of merger support policies that prioritize social connectedness. The reason is that merger partners with strong incentives to merge do not create fiscal common pool problems.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges financial support received from the JSPS (Nos. 20H01504, 20H01450, 22K01542, 22H00856)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Askim et al. (Citation2020) reveal that government agency facing a termination threat reacts by a last-minute flurry of spending when faced with a termination threat.

2 Strebel (Citation2018) examines the driving factors behind bottom-up mergers in the Swiss context and concentrated on financial incentives. However, in the case of Japan, the central government implemented not only a ‘carrot policy’, which includes grants, but also a ‘stick policy’ towards municipalities. Japan’s merger approach may lie somewhere in between a top-down and a bottom-up approach. See, Goto Yasuda Kinen Tokyo Toshi Kenkyusho (Citation2013).

3 The amount of LAT grants provided to each municipality is determined based on the municipal fiscal shortfall calculated by the central government. Because LAT grants are general-purpose lump-sum grants, most municipalities prefer them to specific subsidies. For more details, see Ihori (Citation2008), and Hirota and Yunoue (Citation2017, Citation2020).

4 To my knowledge, there is no cross-higher level government border merger case.

5 As alternative donor pools, the paper employs 193 other nonmerged municipalities for donors. The 193 municipalities belong to neighbouring prefectures, including Toyama, Yamanashi, Nagano, Gifu, and Shizuoka prefectures. Additionally, the paper employs 95 merged municipalities belong to Nagano and Gifu prefectures. The results obtained are similar to those in this paper and are available upon request.

6 For more information on the confidence interval, see Firpo and Possebom (Citation2018) and Abadie (Citation2021).

References

- Abadie, A. 2021. “Using Synthetic Controls: Feasibility, Data Requirements, and Methodological Aspects.” Journal of Economic Literature 59 (2): 391–425. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20191450.

- Abadie, A., A. Diamond, and J. Hainmueller. 2010. “Synthetic Control Methods for Comparative Case Studies: Estimating the Effect of California’s Tobacco Control Program.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 105 (490): 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2009.ap08746.

- Abadie, A., A. Diamond, and J. Hainmueller. 2015. “Comparative Politics and the Synthetic Control Method.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (2): 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12116.

- Abadie, A., and J. Gardeazabal. 2003. “The Economic Costs of Conflict: A Case Study of the Basque Country.” American Economic Review 93 (1): 113–132. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282803321455188.

- Askim, J., J. Blom-Hansen, K. Houlberg, and S. Serritzlew. 2020. “How Government Agencies React to Termination Threats.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory 30 (2): 324–338. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muz022.

- Askim, J., and J. Houlberg. 2022. “The Moderating Effects of Social Norms on Pre-Merger Overspending: Results from a Survey Experiment.” Urban Affairs Review 59 (5): 1295–1320. https://doi.org/10.1177/10780874221090873.

- Bhatti, Y., and K. M. Hansen. 2011. “Who ‘Marries’ Whom? The Influence of Societal Connectedness, Economic and Political Homogeneity, and Population Size on Jurisdictional Consolidations.” European Journal of Political Research 50 (2): 212–238. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01928.x.

- Blom-Hansen, J. 2010. “Municipal Amalgamations and Common Pool Problems: The Danish Local Government Reform in 2007.” Scandinavian Political Studies 33 (1): 51–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2009.00239.x.

- Firpo, S., and V. Possebom. 2018. “Synthetic Control Method: Inference, Sensitivity Analysis and Confidence Sets.” Journal of Causal Inference 6 (2): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1515/jci-2016-0026.

- Fritz, B., and L. P. Feld. 2020. “Common Pool Effects and Local Public Debt in Amalgamated Municipalities.” Public Choice 183 (1–2): 69–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-019-00688-2.

- Gilchrist, D., T. Emery, N. Garoupa, and R. Spruk. 2022. “Synthetic Control Method: A Tool for Comparative Case Studies in Economic History.” Journal of Economic Survey 37 (2): 1–37. online first. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12493.

- Goto, T., S. Sekgetle, and T. Kuramoto. 2021. “Municipal Merger and Debt Issuance in South African Municipality.” Applied Economics Letters 28 (5): 343–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2020.1753872.

- Goto Yasuda Kinen Tokyo Toshi Kenkyusho. 2013. “(16)Heisei no Shichoson Gappei -Sono Eikyo ni Kansuru Sogoteki Kenkyu.” https://www.timr.or.jp/publish/103_part1chap2.pdf. (in Japanese).

- Hansen, S. W. 2014. “Common Pool Size and Project Size: An Empirical Test on Expenditures Using Danish Municipal Mergers.” Public Choice 159 (1–2): 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-012-0009-y.

- Hinnerich, B. T. 2009. “Do Merging Local Governments Free Ride on Their Counterparts When Facing Boundary Reform?” Journal of Public Economics 93 (5–6): 721–728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.01.003.

- Hirota, H., and H. Yunoue. 2014. “Municipal Mergers and Special Provisions of Local Council Members in Japan.” The Japanese Political Economy 40 (3–4): 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/2329194X.2014.1006453.

- Hirota, H., and H. Yunoue. 2017. “Evaluation of the Fiscal Effect on Municipal Mergers: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Japanese Municipal Data.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 66:132–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2017.05.010.

- Hirota, H., and H. Yunoue. 2020. “Public Investment and the Fiscal Common Pool Problem on Municipal Mergers in Japan.” Economic Analysis and Policy 67:124–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eap.2020.07.001.

- Ihori, T. 2008. “Trinity Reform of Local Fiscal System in Japan Chapter 3.” In Decentralization Policies in Asian Development, edited by S. Ichimura and R. Bahl. World Scientific, 55–83.

- Jordahl, H., and C.-Y. Liang. 2010. “Merged Municipalities, Higher Debt: On Free-Riding and the Common Pool Problem in Politics.” Public Choice 143 (1–2): 157–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-009-9495-y.

- Kitazaki, K. 2005. “The Municipal Merger Across Prefectural Border After an Interval of 46 Years: The Case of Nakatsugawa City and Yamaguchi Village.” Journal of Economics and Sociology, Kagoshima University 63:115–127. (In Japanese).

- Nakazawa, K. 2016. “Amalgamation, free-ride behavior, and regulation.” International Tax and Public Finance 23 (5): 812–833. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-015-9381-0.

- Saarimaa, T., and J. Tukiainen. 2015. “Common Pool Problems in Voluntary Municipal Mergers.” European Journal of Political Economy 38:140–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2015.02.006.

- Strebel, M. A. 2018. “Incented Voluntary Municipal Mergers as a Two-Stage Process: Evidence from the Swiss Canton of Fribourg.” Urban Affairs Review 54 (2): 267–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087416651935.