ABSTRACT

As a mainstay of local and national cultural heritage management, historic environment records play an effective role in the dissemination of data, particularly in the modern development control process. However, despite their functionality and sustained professional use, these inventories are not unproblematic, particularly in regards to informal usage. Based on the author’s professional experience this article will discuss some of the issues which convolute the delivery of historic environment data. These issues can be grouped thematically beneath the banners of fragmentation, interoperability, and accessibility. Underpinning these three topics is the relationship between historic environment records as institutions and digitality as both a cognitive process and a distribution mechanism. From a critical perspective, the extent to which these issues reoccur and inhibit the flow of data will be highlighted by examining the historic environment practice in England and Sweden in the hope that these insights can inform the contemporary approach.

Introduction

Archives, collections, and databases have long been the sources for information used in promoting regional and international growth and development, as well as providing the backdrop to research and tourism. They exist as one of the primary means of disseminating culture from generation to generation (Foster, Benford, and Price Citation2013, 773). This is equally true of historic environment records (hereafter HERs), which transmit human culture across a vast number of generations. The only hindrance to how vast and how wide is how one defines the ‘historic environment’. For the sake of policy and practice, definitions that can be enrolled by the heritage profession at large, such as the UK’s National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) (Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government Citation2012) are considered effective. Some definitions are more fluid, such as those of King (Citation2010), who summarises the historic environment to be ‘everything that has influenced, or that reflects, our cultures and those of our progenitors’. This in itself is ‘all-encompassing’ (Holtorf Citation2011, 157), and far beyond the purely material and tangible that most recording mechanisms are most rigorously able to consolidate. As such it should be considered distinctly interdisciplinary.

Along with determining the relationships between the landscape and national heritage resources, there is also public concern driving the process of managing the historic environment. These notions of heritage, borne from the focus on fixed points in the landscape, monuments, or historic buildings, often transcend societal and sociological change (Fowler Citation1997), providing not only tangible and visible markers of communal interest but also points for the expression of intangible heritage. Thus, they require careful categorisation and management in gauging significance academically, professionally and socially. As a result, systems of archaeological and cultural resource management are one of the most prominent elements of global heritage practice, with near universal application. Almost every country has some form of national record of heritage assets (Carman Citation2015, 80), a notion which itself holds some antiquity; the first government-organised inventory of historic buildings in France began in 1837 by the Commission des Monuments Historique (Harrison Citation2013, 44).

This paper seeks to take a critical approach in identifying several of the persistent issues, the most frequently recurring difficulties, regionally and nationally, which currently problematise the keeping of historic environment records. In exploring the problems in recording the historic environment, I will take a comparative approach, allowing for the identification of prevalent issues and diversity in practice; offering perspectives on the symptoms of the bureaucratisation of heritage; the impact of financial stakeholders and the needs for a more egalitarian outlook towards all of the users of these resources. Based on my own professional familiarity, I have rooted the analysis in the archival practices carried out in England. This will be augmented by analysis of Swedish practices, following claims that the Swedish system is one of the most comprehensive inventories in the world (Rundkvist Citation2010, 848) and the recent reconfiguration of the state mechanisms of historic environment data delivery. Given the aforementioned globality of historic environment management, limiting the comparison to two countries is pragmatic; one could almost choose any country as a viable analogue.

Digitality and the Historic Environment

Different contexts, even for similar issues, can require different solutions. So before delving into the comparative issues between English and Swedish practices, it is perhaps useful to briefly take the time to focus on an issue that is prominent in both countries in the form of digitality. Digitality, and therefore digitalisation, relates to the process of adoption of digitised material; digitisation, then, being the process in which analogue material is translated into the digital (Gunnarson Citation2018, 17). With the growing presence and awareness of digitality, both within heritage fields and in the wider humanities, there is a marked effort to allocate attention and resources into realising the ‘digital turn’.

As with any discipline or field, it comes with its own technologies and buzzwords, some of which, such as ‘interoperability’ and ‘linked data’ are included within this text and are becoming important terminologies within historic environment practice. It is important to remember that this turn does not represent a turn away from or a turn towards ‘new culture’ (Pruulman-Vengerfeldt et al. Citation2013), nor does it represent the universal solution – indeed, a digital solution for someone who has been born into a digitally minded culture growing up with digital technology is not likely to be the same as that of previous generations. What is evident, however, is that digital technologies and their application change the dynamics in the fields they are applied to by altering practices and changing relationships between producer and user.

The latter point is particularly important in the historic environment field, as it is generally developed from a top-down perspective. Recent comment that ‘present-day archaeology and heritage management may be much less beneficial for the future than we commonly expect’ (Högberg et al. Citation2018, 640) is particularly true for in situ preservation and site management. This appears Knut-like in its attempt to temporarily halt inevitable decay curves, in light of looming climate change, fuel and food security pressures. While limiting landscape use as a means of heritage protection seems naïve in its long-term aspirations, and therefore futile in its short-term aspirations, rigorous incorporation of digitality within the management of the historic environment could be a mitigating factor. This does not mean that digitality should become the goal or destination; a change of format is not the only way to promote culture. Nor should digitality be isolated from the current cultural process (Pruulman-Vengerfeldt et al. Citation2013). Nonetheless, digitality as a concept has become so closely connected to contemporary heritage practices, it follows that it should also figure heavily in future heritage practices.

To be clear, digitality and the historic environment are not newly introduced; the first forays into digitality centre around the digitisation of analogue material and more perfunctorily, the adoption of computers as a tool. Heritage institutions have already become adept and active users of ‘existing digital environments’ (Pruulman-Vengerfeldt et al. Citation2013), such as social media or internet-based platforms and many individual historic environment records are no strangers to this. By exploiting web-based search functions, numerous institutions have found a method of boosting the accessibility of the historic environment by speeding up the process and by making basic search functions more widely available. However, while these digital environments are commonly employed, one could still argue then that an even greater embrace of the digital turn is required.

The increase in egalitarian availability is only a small step; to access social value, the historic environment has to be democratically usable. The proliferation of GIS-based software has made spatial databases universal in archaeology, with a great deal of success through a great variety of applications (Larrain and McCall Citation2018, 247). There is a temptation to see GIS software merely as a method of making analogue practices quicker, wielded without epistemological or theoretical care (Hacιgüzeller Citation2012). It has been questioned whether GIS can be effective in understanding the relationship between people and place, with certain studies indicating that mapping functionality can be ineffective in the grand scheme of the results (Corbett and Keller Citation2006, 27). The functionality and learning curve required can affect crowdsourcing projects as well, though it should be highlighted that many of these issues are a result of over-functionality rather than user-friendliness (Conolly and Lake Citation2006). In fact, as part of the Know Your Place project conceived by the historic environment team in the city of Bristol, it was made explicitly clear that their volunteers had no queries in regard to the GIS technologies engaged unless they ceased to function (Nourse, Insole, and Warren Citation2017, 157).

Further application of egalitarian principles to the historic environment could be achieved through visualisation. Visualisation already plays an important role within HERs; the events and records themselves are visualisations or representations of the historic environment. However, to quote Kenderdine (Citation2016, 23), this ‘remains largely constrained to 2D small-screen-based analysis, limiting interactive techniques’. Data is still displayed as dots and vectors on a map, simple translations of analogue drawings such as cropmarks and site plans into digital formats. This extent of information visualisation and interface display renders space as being a priori and unchanging (Drucker Citation2016, 241). To this end, the historic environment is reduced to an assemblage of interrelating map points, information rather than knowledge (Lee Citation2012), denying us the ability to acknowledge a narrative image and to form our own presuppositions and relationship to the world (Megill Citation2007). In objective settings, such as an HER, visualisation process favours professional use rather than individual use, enabling rapid data collation for the gazetteers required in the planning process; thereby assuming intrinsic worth (Jones Citation2016, 22–24). Without sufficient mediation, this can fail to encourage public value-based interaction with the historic environment.

Although familiar, maps and 2D distributions remain a positive tool that can be utilised in novel or inspirational settings. It is perhaps the developments in 3D digitisation, however, that most headway is gained. For example, the increasing digitisation in the field, ‘at the trowel’s edge’, allowing onsite interpretation and digital documentation (Dell’Unto et al. Citation2017), some of the in situ preservation issues highlighted earlier can be addressed. Feasibly the documentation of 3D landscapes in GIS can be envisioned for the future of historic environment practice, enabling the pathways to ‘new levels of cognition’ (Kenderdine Citation2016, 23) that visualisation can offer users of any background. This optimism is enforced by the development of virtual products, such as the City of Gothenburg’s Min Stad web portal and application (https://minstad.goteborg.se/minstad/index.do), an annotated 3D visualisation of the city for urban planning and interaction. While Min Stad focuses on the development of the contemporary city, in keeping with Gothenburg’s official policy of ‘citizen dialogue’ (Tahvilzadeh Citation2015; Soneryd and Lindh Citation2018), its latest iteration also allows for the inclusion of personal stories, addressing the intangible interaction with the city’s landmarks, as well as linking to the city museum’s archive of historic images. With such precedents, it is not difficult to envisage similar concepts for the historic environment. Techniques such as LiDAR imaging already enhance and present alternative visualisations of the landscape (Challis et al. Citation2008). This is not to conflate data management with data visualisation, of course. The two are linked, but the problems to which these actions are responses are not the same. Nevertheless, a greater emphasis is placed on the task of managing raw data. As such the solutions to harnessing this data into more cognitive visualisations of the historic environments are not likely to come from within the historic environment sector itself, but from external industries such as urban planning, gaming, and media. This does not absolve the historic environment practice of innovation, but the onus is on the profession for the recognition of potential and utilisation of newer technologies.

There is a criticism that, in general, the skills needed to utilise the historic environment sectors tools and standards are not widely taught in British academia (Lee Citation2012, 32), even less so the skills needed to harness digitality in the historic environment. From personal experience, one fears that under the climate of austerity measures taken at local government level, and the tendency to treat HER officers as administrative staff purely within the bureaucratic process of development, rather than heritage professionals negatively impacts the valuing, the dissemination and the significance of the historic environment. As a result, worries over how to digitally enable greater informal use is not of great concern to staff who are required to demonstrate their economic viability.

This is by no means a complete picture. More novel digital formats such as that of augmented reality are being utilised on an individual basis. One such example is Worcester City HER’s exploitation of the popular mobile game, Pokémon Go in order to promote historic landmarks and sites in the city (Worcester City Council Citation2016). The wider county of Worcestershire has taken a less mobile but nonetheless engaging approach to digital experiences in the historic environment. The Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology team is situated within ‘The Hive’, an integrated public, university and history centre, jointly operated by the county council and the University of Worcester (Creed, Sivell, and Sear Citation2013, 76). Using a multi-touch table, their goal has been to create a touch table application that is both fun and educational for their audience, ranging from children and school trips, university students, staff members, and older generations. Evaluations of the installation demonstrated the Touching History app to be very positively received, with the general public and staff utilising the table as individuals and in small groups. Furthermore, there was evidence to suggest that users were able to socially learn the required gestures to use the table, though a need to ‘subtly and efficiently educate’ some older visitors was noted (Creed, Sivell, and Sear Citation2013, 85).

There is also innovation implemented from above, via Historic England and the Archaeology Data Service (ADS), a digital repository with some 20 years of deployment. As demonstrated in the movement toward the digitalisation of museums, there is great value to be had in identifying best practice from others, particularly within a network of museums (Olsson and Svensson Citation2013). New approaches to interpretation, which explicitly include digital technologies is part of the national research agenda (Historic England Citation2017, 8). Unfortunately, the current financial trends often force HERs to rely upon Historic England, rather than mobilisation of the existing network of local authorities. While it has its benefits, the two-tier system in place in England impacts the direction heritage safeguarding can travel. Many HERs sit within local planning authorities (LPA), which remains the most pragmatic option as they essentially become a cost neutral service. However, that leaves an implication that serving the needs of the LPA is the HERs primary role, which (see Accessibility) attests to. In contrast, in HERs linked to cultural services, public access, digitality and interoperability are no longer a secondary consideration. The drawback in this scenario is greater financial vulnerability. The question then is how can a balance be achieved?

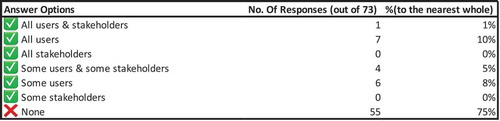

Figure 1. Percentage (based on average number of users) from each user category based on responses to the 2019 Historic England and ALGAO UK HER committee annual survey. Reprinted with permission from Historic England and ALGAO UK.

Digital expression appears more overtly to be a goal of the Swedish historic environment practice. The Digital Archaeological Process (DAP) is a five-year plan developed by the National Heritage Board and is a consequence of the more central approach employed in Sweden. The plan is to improve the workflow of historic environment data between all its actors (Larsson et al. Citation2017; Smith Citation2015) which will allow for the recording of a site along with all of its components, not just the reports and syntheses but the raw data produced in the field too. This, coupled with the semantic linking of digital objects using established data standards, further negates the need for inherent information. There are multiple English HERs that already use DOIs to link to databases of grey literature, such as the ADS. Equally, there are still numerous HERs that use database software that does not allow for hyperlinking, or only provides a reference to the syntheses as part of the record.

In truth, the adoption of digitality in historic environment contexts most probably warrants another article, a thesis or more, devoted entirely unto itself, so for practical reasons, it is necessary to keep this section relatively brief in order to cover more operational issues. There is some necessity for this discussion, however, and the adoption of digital processes is influenced by the chronological development of historic environment practices and the approaches taken at national level. In studying both historiographies, there is a suggestion that many of the issues are mature and deeply rooted in the progression of the field.

Historic England and Regional HERs: The English Approach

As a body Historic England, are inextricably linked with historic environment practices in England. While it is too early to fully realise the implications of the publication, their recently published guide to HERs in England (Historic England Citation2019) sets out the expectations for what is required of an English HER. The historiography of the English HER is long and varied, involving numerous institutional transformations, regulation and increasing levels of state interest (Harrison Citation2013, 11) resulting in the two-tier system in use today. As a result, a variety of seemingly interchangeable terminologies have been acquired, such as Sites and Monuments Record (SMR) or HER. To some extent, which terminology is used is colloquial. There remains continued informal usage of the SMR terminology, though semantically HER is certainly the more inclusive and holistic title. The two are not separate entities, however. SMRs evolved almost organically into HERs with the addition of historic buildings, historic landscape characteristics data, and rapid coastal zone assessment. The realisation that replicating existing data in a new database was unnecessary, invoked a need for a new terminology. What follows is a considerably abbreviated version of these events in order to avoid becoming too heavily mired in the various makeovers.

The National Perspective

Recording the historic environment in England was marked by the establishment of the Ancient Monument Protection Act in 1882 (followed in 1900), whereby a select group of inspectors were charged with advising and reporting to the commissioner of works to facilitate state purchase or guardianship of monuments (Harrison Citation2013, 51). It was not until 1908, with the formation of the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England (RCHME), that the first systematic approach to inventorying the nation’s heritage was begun (Carlisle and Lee Citation2016, 128), reinforcing the Ancient Monuments Protection Acts with definitive lists of the monuments and buildings ‘most deserving’ of protection. This, in turn, was supported by the development of the National Buildings Record (NBR) in 1940, which became part of the RCHME in the 1960s. In parallel, the Ordnance Survey (OS) routinely recorded and mapped the locations of earthworks, ruins, and the locations of major sites from the outset, leading to the appointment of an Archaeology Officer in the 1920s (Newman Citation2011; Carlisle and Lee Citation2016, 129). This data was the result of the work carried out by the National Archaeological Record (NAR) and lead to the card index system employed from 1947 onwards, after C.W. Phillips took over from O.G.S Crawford as OS Archaeology Officer (Phillips Citation1959). Eventually, the OS’ archaeological responsibilities were passed to the RCHME in 1983 and became part of the NAR (Newman Citation2011). These, in turn, were amalgamated with the NBR to form the National Monuments Record (NMR) in the 1990s (Carlisle and Lee Citation2016, 129).

Following the merger of the RCHME and the government’s advisory body, English Heritage (lately subdivided into the English Heritage Trust and Historic England), the NMR currently stands as two national datasets (Carlisle and Lee Citation2016, 129). First, there is the National Heritage List for England (NHLE), which lists all statutory and protected sites in the country, including listed buildings, scheduled monuments, protected wrecks, registered parks and gardens, and battlefields. This is definitive, and while the data is available elsewhere, this is the only official and fully informed source. Secondly, there is the National Record of the Historic Environment (NRHE), which is far more comprehensive in a historic environment sense and currently holds over 420,000 records. Despite being a national dataset in practice, the NRHE is not and should not be viewed as conclusive in the same manner as the NHLE. This is due to the coexistence of the historic environment datasets maintained by various authorities on a regional level.

The Regional Perspective

Originally SMRs were held at local government level, usually with the local council as the burdens of heritage fell upon the public purse. According to Gilman and Newman (Citation2018), the first true SMR to be established was in Oxfordshire, with others following suit due to a growing awareness in light of post-war urban development that information on in situ archaeology was sparse. This development took place before Planning Policy Guideline 16 (Department for Communities and Local Government Citation1990) gave archaeology a statutory position in the planning process, resulting in needless damage and destruction of historic environment material. PPG16 was driven by the environment white paper, This Common Inheritance, which moved to levy the cost of environmental but also heritage damage upon the developers and beneficiaries – in other words, the polluter pays (Kearns Citation1991, 367). By unburdening the public responsibility for the cost, the local authority digging units dissolved but the SMR evidence bases remained with the LPAs and became financially covered by planning fees. If local authorities could inventory and identify archaeology ahead of development, more could be done to manage archaeological risk.

As ‘the scope of SMRs has expanded to include historic features across a broad range of landscapes, townscapes, and seascapes’ (Darvill Citation2009), as well as recording the act of archaeological practice itself (Carlisle and Lee Citation2016, 131), they became known as the HERs in order to reflect this newfound universality. The NPPF rules that local planning authorities do not necessarily need to maintain their own database – at one point Lancashire’s dataset was being curated by Lancaster University (Fraser Citation1997) and even now is maintained only on a voluntary basis on behalf of Lancashire County Council. They must, however, have access to a HER and as a minimum the relevant record should have been consulted when a planning application is to be considered (Ministry of Housing Citation2012). Resultantly, HERs are operated on various levels of local government such as county councils, district councils, unitary authorities or in certain cases they are covered by specific urban archaeological databases, such as those in Oxford and Winchester. Further to this, other bodies such as The National Trust and the Church of England who operate their own databases, though this is primarily from the perspective of property management (Historic England Citation2019, 6). Currently, there are 84 local authority HERs operating alongside the NRHE and NHLE, and these are now viewed as the primary repository for historic environment data.

Much is owed to this pattern of growth in the sector. Holding the evidence base within the local authority was often linked to the adoption of digital technologies, mainly because local authorities were early implementers of computer power. As small, often well maintained and non-critical databases, SMRs/HERs were often used as test beds for IT, for example Berkshire County Council first tested their adoption of GIS in their SMR (David Hopkins, county archaeologist at Hampshire CC and formerly Berkshire CC, personal communication and additional thoughts and comments on the topic and this article). In this sense, many SMRs/HERs were ahead of the archaeology sector at the time, though arguably these roles have reversed. Now most, if not all, of these services, have adopted a digital storage and extraction system for the data they originally held in paper format. Not all of them have fully digitised their backlog of paper documents and there remains a great deal of supporting information awaiting OCR scanning. As there is an increasing need to cover costs, the data provision aspect is routinely the priority, and the notion of digitality is often associated with encumbrance and the burdensome task of scanning archaeological literature.

Riksantikvarieämbetet: The Swedish Approach

The current approach the Swedish National Heritage Board, Riksantikvarieämbetet (RAÄ, see https://www.raa.se/), takes is significantly different from the practices of inventory in the UK. Rather than operating a national database as well as regional repositories, the management of the Swedish historic environment has always been provided centrally, though there still remain observable national vs. regional divergences, particularly in regards to how and who carries out archaeological excavation.

The origin of Swedish practice is also far more antiquated than those in the UK. In fact, the first steps towards archaeological resource management as we might recognise it took place by the end of the sixteenth century (Carman Citation2015). From 1599, Johan Bure (Latinised to Johannes Bureus) and several assistants undertook regular topographic surveys for the collection of runic inscriptions (Carman Citation2015; Schnapp Citation1997). Bure was appointed Sweden’s first Riksantikvarie in 1630 (Gardinge Citation2018) and a statute concerning the protection of Swedish antiquities was passed on the very same day. Such marked ‘the passing of archaeology into the public domain’ (Schnapp Citation1997).

Despite these early forays into heritage management, it was not until the twentieth century that the practice of inventorying the past in Sweden became as exhaustive or representative as that of the RCHME. As Sweden transitioned from a rural populace to an industrialised nation, sections of the intellectual elite turned to archaeology and history as a galvanising component of national identity (Magnusson Staaf Citation2000, 182). Modernisation of cities required greater organisation and scale of archaeological recording, for example, the construction of a new sewage system in Malmö in 1907 and the subsequent documentation of the medieval city (Magnusson Staaf Citation2000, 182). Such developments inevitably require systematic recording and dedicated repositories, which at this point were largely held by regional museums, universities or local history societies. In 1937 however, with the inception of the Fornminnesregistret, the National Heritage Board made the concerted effort to systematically inventory visible ancient remains (Riksantikvarieämbetet Citation2018). The inventory was collated on a parish by parish basis originally using cadastral maps, though this has since been supplemented by archaeological fieldwork reports (Marcus J. Smith, personal communication, 28 February 2018). Initially, this was recorded in inventory books, but as of the mid-1980s, small-scale digitisation of written material was undertaken. By the 1999 introduction of the Fornminnesinformationssystemet (FMIS), the National Heritage Board began envisioning digital access to the database in its entirety (Riksantikvarieämbetet Citation2018). This was achieved surprisingly quickly. Although only the counties of Skåne and Gotland had successfully been digitised by 2003, by 2005, data for every county was digitally available, albeit only to heritage professionals (Riksantikvarieämbetet Citation2018). As of Autumn 2018, FMIS began a new transition as part of the DAP. This culminated with the launch of the new Kulturmiljöregistret (KMR) in February 2019, superseding FMIS and acting as an umbrella system (Larsson et al. Citation2017) allowing all the data housed in digital archives to be related to the sites and monument recorded in the HER, with the long-term goal of achieving ‘reciprocal linking of data across databases and institutions’ (Marcus J. Smith, personal communication, 26 June 2018).

Situating KMR within the National Heritage Board is significant in terms of the structure of heritage management in Sweden. Traditionally, the distribution of roles has been well delineated: the County Administrative Boards manage administration and control; regional County Museums handle collecting and outreach; and the universities focus on research and education (Högberg and Fahlander Citation2017, 14). The delineation of this structure is maintained by KMR and each role remains distinctive. Crucially, this favourably impacts upon funding; the austerity measures in place in English LPAs often demand internal heritage actors compete for financial resources. By comparison, holding HERs within the local planning authorities often requires one institution covering multiple roles. Usually, this is in the areas of administration and control, as well as collecting and outreach, with local museums often falling under the remit the county council. Sweden’s approach allows for separate funding sources, and therefore greater potential for development.

There are other differences of note. The urban environment, as both a historic and contemporary architectural context, is not recorded in the same dataset as ancient monuments in Sweden. This is somewhat unusual given that at times Swedish archaeology and architecture have been closely interlinked. Again, to use Malmö as an example, to facilitate the city’s modernisation, several medieval and renaissance buildings were torn down to make way for modern replacements, so the cultural resource management efforts at the time were oriented toward the urban environment (Magnusson Staaf Citation2000, 183). This of course only represents the perspective of the city of Malmö, which has a distinct history from other major cities and towns in Sweden, but it demonstrates the difficulty separating historic buildings studies entirely from archaeology. The relationship with a bygone urban environment, experienced through the lens of archaeology, is somewhat different from the interaction with an extant urban environment, where distinctions between extinct and standing structures can be delineated. This is evident in Sweden’s management of historic buildings. While still under the operation of the National Heritage Board, the built environment is recorded separately within the Bebyggelsregistret (BeBR) (Fadeel Citation2018). Unlike the NHLE, which records only the designated built environment, BeBR allows for the record of all buildings, not just historic or listed buildings. Eighty-thousand entries have been recorded since the record was implemented in 2011, around 13,000 of which are designated National Monuments, Historic Buildings and Church Monuments (Fadeel Citation2018).

The Comparative Issues

These different trajectories and procedures directly inform perspectives on the operational issues in managing historic environment data in both countries as many of the systemic issues are particularly complex and deep-rooted. They will likely continue to impact the utility of such resources, not only for the commercial and professional heritage sector, but also to academics and members of the public.

Fragmentation

A historic environment record is a skein of archaeology, geography, history, and urban studies among other fields, and as such the ties that bind them together within one collection are not solid. Perhaps, it should be unsurprising then, that the most mutually persistent restriction to the convenience and usefulness of historic environment data is fragmentation. Historic environment fragmentation is embodied in several ways; it is not merely a case of scattered resources. Fragmentation takes place across the archaeological record; through architectural style; patterns of urban development; regional social and economic conditions; through standards of practice to name but a few. The representativity of the archaeological record itself is frequently fragmented, via taphonomic processes and differential preservation. Even if ‘the influence of physical and environmental factors is in general constant in a given geographical and climatic region’, (Kristiansen Citation1985, 7), this is not a priori if one considers the impact of the last glacial maximum and the changing land/sea relationships in coastal regions. Then there is the impact of modern urbanisation and settlement geography. Björn Magnusson Staaf (Citation2000) is explicit in this regard, highlighting that ‘circumstances surrounding the excavation of a Sami settlement in Lapland are quite different from the investigation of an Iron Age burial site in a densely built-up area in the surroundings of Stockholm’.

These examples of representativity are easily identified within the historic environment, and contemporary practice has evolved to take these factors into account. Understanding and reflecting the various nuances is key, but this is not necessarily compatible with the education and specialisms of all HER officers. Thus, even within a single corpus, there is the fragmentation of standards, varying significantly with each incumbent employee’s tenure. Inevitably, it is part of the job to limit these variations as much as possible, however, given the multidisciplinary nature of the task it is unsurprising to find that the recording of different disciplinary aspects is often biased by an HER officer’s own background and specialities. While they do not work in isolation – there is often both peer and academic support within the sector – the problems occur in the form of Rumsfeldian ‘unknown unknowns’; lacking the prerequisite starting point of the more resolvable ‘known unknowns’. As a result, the lack of interdisciplinarity restricts the vision of both the assets and the potential latent and current demand (Montella Citation2015) of the historic environment as a cultural heritage asset.

The degree to which these variations are problematic can be mitigated against, through personal development or as is often the case, longevity of exposure and work experience. Institutional fragmentation is more difficult to work around and is most frequently demonstrated by the multiple bodies and stakeholders involved in processing and managing historic environment data. In England, these boundary restrictions and delimitations are often closely tied to county boundaries and historic political developments and are heavily intertwined with accessibility issues. Who has responsibility for what areas, given that there are so many different authorities maintaining accessible records, is a regular source of confusion, even within the heritage profession. This is particularly problematic in places such as Hampshire, where the county council maintains a central HER, but is not responsible for the cities of Portsmouth, Southampton and Winchester, who maintain their own datasets. This is further complicated by the New Forest National Park Authority who are responsible for the supply of data within the National Park’s boundary but lease the data itself from the county council. This is occasionally further confused by the Isle of Wight, who use several of the county council’s ecology service but maintain their own HER, as well as the South Downs National Park Authority, which spans three counties and use the HER services of five different local authorities (South Downs National Park Authority Citation2018). This is not a unique situation, and intra-county division of the historic environment record is evident through the South West, the Midlands and the North.

It is via historic material type though that the Swedish system is most fragmented. While the centrality of RAÄ’s historic environment management negates most of the issues of institutional fragmentation, it is still evident in places, for example, historic maps for which the copyright is held with the National Land Survey Lantmäteriet. Cartographic information pertaining to city fortifications is held in Krigsarkivet, which itself is part of Riksarkivet (the National Archive), as such material is still considered to be a concern of national security as well as a historic resource.

Holding KMR and BeBR as two separate datasets is not ideal from a theoretical standpoint, given that the built environment is rarely mutually exclusive from the historic environment. From a historic buildings perspective, there is no need to translate the raw data into knowledge, as the building itself is the record (Lee Citation2012, 30) though this only applies if one studies a single building in isolation. As historic environments are in a continuous transformation process (Karakul Citation2007), the tangible features of both the historic and modern urban landscape are the physical structure around which intangible heritage and cultural expression grows. To separate the two is to divide the historic environment itself. While the data is maintained and provided by the same body, it is somewhat less problematic than the institutional divisions evident in England, but it also makes compatibility and holism harder to achieve.

Interoperability

One problem that both countries share as a result of the fragmentation of records is the double handling of data. Double handling in the Swedish system is rare, but it is generally the result of the recording of historic buildings as monuments within FMIS prior to the conception of BeBR. In England, doublehanding is more common. In theory, this should not be the case, but in practice, with different standards of recording and data handling between institutions and even within institutions, it occasionally becomes difficult to distinguish exactly which records relate to each other and how. Resultantly, interoperability has long been a noted requirement, since any given site or monument may be simultaneously recorded by ‘a local authority for development control purposes, a national body for purposes of legal protection, the landowner for land management, or a thematic national survey of sites of a particular type’ (Lee Citation2005). Attempts to minimise the variability of recording standards were introduced in earnest with the introduction of the Forum on Information Standards in Heritage in 2000, and the production of the MIDAS data standard, which essentially provides definitions in the form of metadata to increase the commonality of a dataset (Lee Citation2005).

Despite this, interoperability remains a potential issue in England. This is due to the variability of information management systems in place throughout the country. This is highlighted by Carlisle and Lee (Citation2016, 132–133); of the 84 HERs operating in England, 75% make use of a single software, HBSMR produced by exeGesiS, while the rest either use in-house systems, alternative off-the-shelf products, such as Intrasis, or they merely get by with database software such as Microsoft Access. In the same paper, it is pointed out that it is perceived that exeGesiS are capable of influencing the development of standards in the historic environment management sector. This is not necessarily problematic in itself, it is not unreasonable to receive consultation from software development, particularly in terms of how to progress technically. This is evident in the Heritage Information Access Strategy (HIAS) (May Citation2018), whereby exeGesiS were employed as consultants in determining how best to accession the NRHE into the local HER databases (Flower and Lush Citation2016). This can still be problematic though, given the wide functionality of HBSMR, such as allowing for customisable chronologies. Most use the MIDAS data standard, but there is encouragement from exeGesiS to modify regional periodisation standards to reflect local conditions and ‘change understanding’ (Crispin Flower, email addressing [email protected], 25 June 2018). This would be understandable on a national level as archaeologies and histories do not always evolve coevally; however, this alternative practice would have serious implications for interoperability, hence the development of the MIDAS data standard in the first instance.

A further problem is how this relates to efforts to improve the interchange of data between the supposed ‘authorised’ datasets and the contributions of community-led projects (Carlisle and Lee Citation2016, 133). Given that many such community projects are run by volunteers, complex software solutions, that for the most part are not self-intuitive, are not necessarily compatible with these aims. More importantly, in the scheme of providing a national overview as required by HIAS, any failure to interact with a regional HER becomes a hindrance to this goal. Those HERs who have rejected exeGesiS software, for another provider or in favour of in-house proprietary software must be kept in the loop. In practice, many of those still running incompatible software are not doing so out of choice but out of economic necessity, and in these instances, the cost of upgrading would require the loss of staff or may even represent a threat to the service’s existence.

The dynamic of interoperability is slightly different in Sweden as a result of the RAÄ’s centralised HER. As if to prove that it is not the universal solution to all ills, digital technology is at the heart of the issue. A contributing factor to data fragmentation and issues of interoperability is arguably a surfeit of funding for digital projects, through the likes of the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences (Riksbankens Jubileumsfond) and the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters (Kungliga Vitterhetsakademien). These bodies have financed, and continue to finance, a range of different projects, all of which offer different solutions in different fields. Fortunately, an awareness of the necessity of defined structure has already been established, making demands for data management plans compatible with the Swedish National Data Service (SND). This is where interoperability, via metadata and linked data, becomes crucial, as there is a great amount of historic environment data deposited within the SND. However, if sites are to be considered historically valuable, and form the basis for an archaeological narrative, ongoing research and reporting must be part of the feedback mechanism within the historic environment record. Without the essential data, a given site’s relevance cannot be accurately assessed, and therefore protected.

As a result, what data belongs where can be troublesome when efforts are made to streamline the workflow of both depositing and distributing historic environment data. Although FMIS (formerly) and BeBR recorded the monuments and buildings themselves, the products of fieldwork, both in terms of the tangible heritage produced as artefactual material and the reports, drawings, notes and photos that form the synthesis of a site are required to be deposited with the local authority, most often a national or local museum (Larsson et al. Citation2017). However, in this format only analogue data is captured, despite the increasing turn towards digitally produced fieldwork reports over the last 20 years, prompting the switch to KMR. Platforms such as RAÄ’s Digisam (http://www.digisam.se/) bring together state organisations to cooperate in providing useful access to digitised heritage resources, strengthening interoperability and accessibility. Nonetheless, unity between archaeological actors is still required in forwarding the development of a coherent historic environment record within the public domain. The lack of a mandatory register for archaeological fieldwork or events that affect the status of ancient monuments held by the National Heritage Board (Smith Citation2015) was identified, as has the need for a digital repository for grey literature produced as a result of fieldwork, similar to the ADS or the Dutch depository, EDNA (DANS Citation2018). Without these repositories, digitally produced site records and post-excavation data are at risk of being lost or excluded from the narrative. The DAP was actioned by the National Heritage Board in direct response to these shortcomings.

Accessibility

The accessibility of historic environment data is very much multifaceted and relates as much to format and display of information, as it does to the mechanisms for extracting the information. It is important when discussing access to HER data to understand what or who usership entails. Different users have different needs and responses. For example, those purely interested in data grabs in relation to development and planning industry tend to be defined as commercial, and numbers tend to ebb and flow in response to demand. Public or community users, however, tend to be more interested in place or representation, benefitting more from solutions focused on content rather than ‘medium, process, or professional expertise’ (Roued-Cunliffe and Copeland Citation2017).

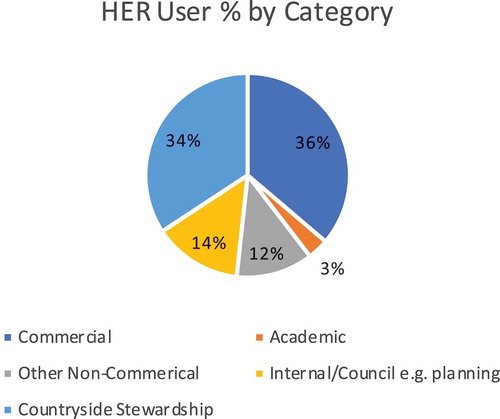

From statistical sources, the English system is utilised in the vast majority by contract archaeologists. Using data extracted from the Historic England and ALGAO’s Annual Survey, demonstrates that commercial archaeological entities and countryside stewardship schemes are the primary consumers of HER data. As these activities have a financial incentive for HERs it could be argued that they are also the primary drivers, and that this system of inventory is skewed towards professional practice. The Swedish system is also user-driven, albeit via remote access, and while the anecdotal responses from historic environment record officers suggest a similar pattern of usage is apparent, the definitive figures were only available from 2009. It has been noted within the RAÄ that usage has approximately doubled since then, with a number of users from beyond the remit of cultural heritage management, usually interested individuals and the real estate agents (Malin Blomqvist, personal communication, 30 January 2018).

In England, the current arrangement ‘works’, in that it functions to the extent that heritage consultants and developers can access the data and planning archaeologists can devise appropriate measures of mitigation to lawfully carry out development within NPPF guidelines. Even so, the current situation is inhibitive and can be disruptive. Waiting times and priorities, as well as the availability of staff, vary from authority to authority, since numerous HERs operate with part-time officers. The question of service cost is also relevant to the conversation, as there is no standard price for the cost of a commercial HER search, and the guidelines that are in place allow for generous interpretation. Since the data held in an HER is considered to be public information, it is mostly paid for by funds generated by local and national taxes, it is unlawful to charge for ‘accessing information’. However, as per the EIR (Department for Food Citation2004), it is not illegal to charge for reasonable costs, and it even recommended that these are recovered and explicit access and charging policies should be put in place (Gilman and Newman Citation2018). This ought to be measured by staff time and operating cost, but there seems to be no definitive correlation between the amount charged and the actual cost of running the search, with numerous local authorities charging over 100 pounds sterling for what realistically takes no more than two hours. This leaves many on shaky legal ground, especially when one considers that the cost rises inversely in many authorities when asked to perform the search as a priority. This is regularly defended in the context of Public Sector Information Regulations (The National Archives Citation2018) and is rarely challenged by contractors, who often welcome the cost as a necessary burden to maintain the current levels of custodianship.

Clearly, this is no longer a case of staff time and operating cost, nor is it proportionately egalitarian access to a public resource. This statement requires a degree of clarification, however. Exemptions are commonplace and data access is frequently made freely available for members of the public. Academics are often exempted too, though recent anecdotal evidence from Richard Bradley at a recent conference would indicate that this is not a nationwide policy. The issue is that the attention given to each user demographic is not equal, with beneficiaries that pay most receiving the quickest and best service. This is problematic given that the national planning systems insist this service is provided for. Unfortunately, this is rarely driven by the archaeological representatives of the LPA, and instead is the result of pressure to cover costs by internal and external stakeholders. The cost is regularly justified by stakeholders and commercial heritage professionals as being minimal in the grand scale of modern development, and many would argue that it is worth it to maintain the services currently in place. This should, and does, cause ethical and theoretical concerns for local government archaeologists, but there are many who equally see it as the only means for HERs to continue to exist in the same capacity.

As well as the financial aspects of access, there are further issues closely tied to the problematic aspects of fragmentation. In Sweden, the centrality of the RAÄ and the goals of the DAP largely eliminate this issue, though there are minor issues. There is no agreement with Lantmäteriet or Riksarkivet for the integration of historical maps (Åsa M. Larsson, personal communication, 30 January 2018) for example, meaning for such documents a charge may be levied by the National Archive.

English HERs, meanwhile, perform an admirable and incomparable service for locality-based enquiries. The issues tend to become more apparent when thematic enquiries are required, whereby one must stitch together the results of enquiries from multiple HERs across numerous various sources. The numerous operators that coexist in England and their lack of cohesion inhibit accessibility, but there is also greater depth to the problem.

Resources such as land management and national survey results, as well as the grey literature produced as a result of archaeological fieldwork should be deposited in one or both of the local HER and the NMR, and this inevitably raises the question of which is the definitive source of data. The HIAS guidelines indicate the local HER should be the first point of contact, and according to Historic England’s Three Corporate Plan 2018–21 (Historic England Citation2018, 27), there is a distinct negative trend in sites added to the NHLE, and the pre-application proposals and planning casework advised upon, due in to additions to HERs. Previously users, commercial or otherwise, were required to visit multiple sources to ascertain the most complete dataset. While to some extent this is still a requirement, not gone unnoticed by either Historic England or within the HER community and positive movement towards rectification are being made.

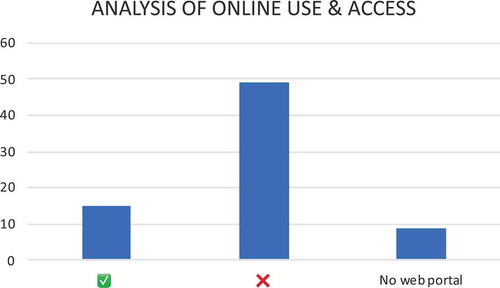

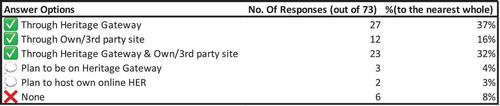

As well as bespoke HER web portals, aggregation platforms are a route that is being explored. The Swedish model demonstrates that this method of user-focused extraction of historic environment data is clearly viable, and English practice is following suite. The UK Heritage Gateway (https://www.heritagegateway.org.uk/gateway/), for example, is operated in partnership with Historic England, the Association of Local Government Archaeology Officers (ALGAO) and the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC). An online portal allows users of any background the ability to remotely search multiple national and regional data sources for any location, object or site type, as per the MIDAS data standard. As demonstrates, the majority of HERs surveyed respond positively to the idea of hosting information online, with the majority utilising or planning to utilise the Heritage Gateway.

Figure 2. Approaches to online HER access based on the 2019 Historic England and ALGAO UK HER committee annual survey. Reprinted with permission from Historic England and ALGAO UK.

This is not yet without criticism, perhaps as the 6 HERs that retain local access to their data would argue (the data is anonymised, so the circumstances pertaining to individual HER responses are unknown). There are worries that the online access will either infringe upon the HER position as the definitive data source or undermine the HER by subverting the need for a local enquiry. It is also possible to question the user focus of the Heritage Gateway initiative. While one can register for a Historic England Heritage Passport, allowing one to register their areas of interest, it is not a necessity for accessing the search functions. As such, there is no fixed user profile, or an audience development plan. The literature provided by ALGAO simply indicates Heritage Gateway is most useful as the first port of call for ‘smaller projects’ (Thompson Citation2014). Since the HIAS guidelines indicate the local HER should be the contact point for planning casework, the implication is that both HIAS and the Heritage Gateway are aimed at the academic user. As demonstrates, this is a very small sector and resultantly, there are HER officers who limit Heritage Gateway interaction based on this narrow audience field, instead prioritising community-focused initiatives.

It is perhaps the lack of understanding of user needs that is most problematic in terms of accessibility, both locally and online. While it seems that the RAÄ know internally how their system is being used, the figures are not available in support of that. Conversely in the English system, worryingly 75% of the HERs responding to the 2019 Annual Survey are not gathering feedback or surveying user’s needs . A similar trend is evident for those that utilise online web portals. Only 15 of the 73 HERs surveyed carry out analysis of the online use and access to their data . Many of those that do also derive their analysis from Heritage Gateway, which is limited to analytics such as search terms and usage analytics as it stands (Charina Jones, email addressing [email protected], 1 May 2019). While this is set to change, it leaves the sector critically short on the qualitative understanding of its social value, particularly among its non-commercial usership.

The Historic Environment as a Public Resource

There is clearly still a requirement for local and regional management of the historic environment. The archaeological and scientific expertise championed by national organisations are valid, particularly for the management, curation and conservation of the historic environment in the context of development and modernisation, but as Sian Jones argues, it often fails to capture and embody people’s relationships to the historic environment on an informal or non-professional level (Jones Citation2016, 22). These informal interactions rely upon social value and sense of place. While management against loss on a commercial scale is necessary, a sense of place is borne of locally realised meaning, the required negotiation of regional community and expertise (Waterton Citation2005) also has to take place in close vicinity.

There are exemplars within the profession, with a public facing focus rather than serving the planning system. The aforementioned Know Your Place is regularly cited as a benchmark within the HER practice. The project’s intention was to ‘promote positive Localism’ (City Design Group Citation2011, 3), championing collaborative practice between the HER and local community groups and volunteers. Workshops, a programme of data collection, and new web interface all formed a toolkit to widen public access and engagement with the HER. This approach is already being replicated in the Layers of London, Our Warwickshire, and New Forest Knowledge projects. This community success indicates that even though regional HERs should be encouraged to open access to online users, they must equally remain a presence and feed the management and discourse of historic environment, as they are best placed for public interaction. This is an area in which the Swedish system cannot compare. In these instances, the traditional delineation that community focus is the domain of local cultural institutions, which means that the KMR is almost entirely separated from the local experience.

This leads to a final point regarding custodianship. As Insole (Citation2017, 57) highlights, building a comprehensive heritage database requires sourcing information from beyond the planning process, and therefore requires different strategies for data collection. One such strategy, which as he points out, ‘reflects the current zeitgeist’ is crowdsourcing (Insole Citation2017, 60). This approach however significantly alters the role of the database and the expert. In this situation, as demonstrated by the Out Stories (Outstories Bristol Citation2018) dataset maintained as part of the Know Your Place dataset, enables a community to define and manage their own heritage, using the platform as a means of publication and distribution. In this role, the community can focus on the topic, while the expert takes on the role of curator and facilitator (Westberg Gabriel and Jenssen Citation2017, 94). This is a significant departure from the current paradigm which enables the local authority to present the data they receive from the source material and choose their own methods of validating and referencing the producer of the data, which is still most frequently the archaeological contractor. Open and easy to access online platforms, characterised by an ‘online bazaar’ approach, are encouraged (Westberg Gabriel and Jenssen Citation2017, 93–94). While this presents its own set of preservation and operational challenges, the requirement for local centres and facilitators clearly must remain a presence to feed the management and discourse of historic environment, as they are best placed for community interaction.

Conclusion

Both England and Sweden have deep-rooted ties to cultural resource management, from the early appointment of a Riksantikvarie to the Ancient Monuments Act’s first forays into the systematic recording of national heritage. While this was largely a measure of aesthetic values in both states’ increasing levels of government involvement in heritage management is evident, resulting in both increasing bureaucratisation and an ever-greater focus on risk management in response to the growing threat of modern development to both known and unknown heritage. This resulted in complex, multi-stakeholder mechanisms for recording and managing the known historic environment. These systems require careful regulation and in-depth standardisation to maximise interoperability and accessibility for a varied audience. As observed in the article, the mechanisms in place have a varying impact due to persistent structural and conceptual issues. Although much of this relates to what historic environment data is and how it has been stored and disseminated historically, it is proposed that the principles of digitality may mediate several of these issues.

Both Swedish and English approaches have turned to the adoption of digitality over the past two decades, allowing access directly in the historic environment database via a self-service web portal. This approach favours egalitarian access to commercial enterprises, academics and the public alike. In the English context, there are still stumbling blocks in the form of local policy and data fragmentation inhibit realisation in the same way as the centralised Swedish approach achieves. However, where defragmentation and standardisation are encouraged in England; in Sweden, the remote and central approach means cooperation with local repositories to unify the approaches of heritage actors is the call to combine the state operation with the realities of regionality. For both, along with continued encouragement of informal usage, more needs to be done to promote the dissemination of historic environment data and its archives. With a greater cognition and access to more intangible aspects of heritage, the social value and understanding of the historic environment can be improved on a wider scale.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

William R. Illsley

William R. Illsley is a PhD candidate and early stage researcher on the CHEurope project. He studies archaeological archives and collections as digital manifestations of heritage. [email protected]

References

- Carlisle, P., and E. Lee. 2016. “Recording the Past: Heritage Inventories in England.” Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 6 (2): 128–137. doi:10.1108/jchmsd-02-2016-0013.

- Carman, J. 2015. Archaeological Resource Management: An International Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Challis, K., Z. Kokalj, M. Kincey, D. Moscrop, and A. J. Howard. 2008. “Airborne Lidar and Historic Environment Records.” Antiquity 82: 1055–1064. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00097775.

- City Design Group. 2011. Know Your Place: Learning and Sharing Information about Historic Bristol. Bristol: Bristol City Council.

- Conolly, J., and M. Lake. 2006. “Introduction and Theoretical Issues in Archaeological Gis.” In Geographical Information Systems in Archaeology, edited by J. Conolly and M. Lake, 1–10. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Corbett, J., and P. Keller. 2006. “Using Community Information Systems to Communicate Traditional Knowledge Embedded in the Landscape.” Participatory Learning and Action 54: 21–27.

- Creed, C., J. Sivell, and J. Sear. 2013. “Multi-Touch Tables for Exploring Heritage Content in Public Spaces.” In Visual Heritage in the Digital Age, edited by E. Ch’ng, V. Gaffney, and H. Chapman, 67–90. London: Springer.

- DANS. 2018. “E-depot Voor De Nederlandse Archeologie.” Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed. Accessed 13 March 2018. https://archeologieinnederland.nl/bronnen-en-kaarten/e-depot-voor-de-nederlandse-archeologie

- Darvill, T. 2009. “Sites and Monuments Record (SMR).” In The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology, edited by T. Darvill, 420–421. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dell’Unto, N., G. Landeschi, J. Apel, and G. Poggi. 2017. “4D Recording at the Trowel’s Edge: Using Three-dimensional Simulation Platforms to Support Field Interpretation.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 12: 632–645. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2017.03.011.

- Department for Communities and Local Government. 1990. Planning Policy Guidance 16: Archaeology and Planning. London: HMSO. https://www.wyreforestdc.gov.uk/media/115277/NP25-PPG16-Archaeology-and-Planning.pdf

- Department for Food, Environment and Rural Affairs. 2004. “The Environmental Information Regulations.” http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2004/3391/contents/made

- Drucker, J. 2016. “Graphical Approaches to the Digital Humanities.” In A New Companion to Digital Humanities, edited by S. Schriebman, R. Siemans, and J. Unsworth, 238–250. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

- Fadeel, E. 2018. “About BeBR.” Riksantivarieämbetet. Accessed 5 March 2018. https://www.raa.se/in-english/digital-services/about-bebr/

- Flower, C., and M. J. Lush. 2016. Data Supply and Reconciliation between NRHE and HERs – End-of Project Report. Talgarth: exeGesiS Spatial Data Management.

- Foster, J., S. Benford, and D. Price. 2013. “Digital Archiving as Information Production.” Journal of Documentation 69 (6): 773–785. doi:10.1108/jd-04-2012-0047.

- Fowler, P. 1997. “Archaeology in a Matrix.” In Archaeological Resource Management in the UK: An Introduction, edited by J. Hunter and I. Ralston, 1–10. Stroud: Sutton Publishing.

- Fraser, D. 1997. “The British Archaeological Database.” In Archaeological Resource Management in the UK, edited by J. Hunter and I. Ralston, 19–29. Stroud: Sutton Publishing.

- Gardinge, A. 2018. “Our History.” Riksantikvarieämbetet. Accessed 1 March 2018. https://www.raa.se/in-english/swedish-national-heritage-board/our-history/

- Gilman, P., and M. Newman. 2018. “Informing the Future of the Past: Guidelines for Historic Environment Records.” Historic England. Accessed 27 February 2018. http://archaeologydataservice.ac.uk/ifp/Wiki.jsp?page=Main

- Gunnarson, F. 2018. “Archaeological Challenges, Digital Possibilities: Digital Knowledge Development and Communication in Contract Archaeology.” Licentiate thesis, Linnaeus University.

- Hacιgüzeller, P. 2012. “GIS, Critique, Representation and Beyond.” Journal of Social Archaeology 12 (2): 245–263. doi:10.1177/1469605312439139.

- Harrison, R. 2013. Heritage: Critical Approaches. London: Routledge.

- Historic England. 2017. Research Agenda. Swindon: Historic England.

- Historic England. 2018. Three Year Corporate Plan 2018–21. Swindon: Historic England.

- Historic England. 2019. A Guide to Historic Environment Records (hers) in England. Swindon: Historic England.

- Högberg, A., and F. Fahlander. 2017. “The Changing Roles of Archaeology in Swedish Museums.” Current Swedish Archaeology 25: 13–19.

- Högberg, A., C. Holtorf, S. May, and G. Wollentz. 2018. “No Future in Archaeological Heritage Management?” World Archaeology 49 (5): 639–647. doi:10.1080/00438243.2017.1406398.

- Holtorf, C. 2011. “My Historic Environment.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 2 (2): 157–159. doi:10.1179/175675011x13122044136596.

- Insole, P. 2017. “Crowdsourcing the Story of Bristol.” In Urban Archaeology, Muncipal Government and Local Planning, edited by S. Baugher, D. R. Appler, and W. Moss, 53–68. Cham: Springer.

- Jones, S. 2016. “Wrestling with the Social Value of Heritage: Problems, Dilemmas and Opportunities.” Journal of Community Archaeology & Heritage 4 (1): 21–37. doi:10.1080/20518196.2016.1193996.

- Karakul, Ö. 2007. “Folk Architecture in Historic Environments: Living Spaces for Intangible Cultural Heritage.” Millî Folklor: Uluslararasi Kültür Arastirmalari Dergis 75: 151–163.

- Kearns, G. 1991. “This Common Inheritance: Green Idealism Versus Tory Pragmatism.” Journal of Biogeography 18 (4): 363–370. doi:10.2307/2845478.

- Kenderdine, S. 2016. “Embodiment, Entanglement, and Immersion in Digital Cultural Heritage.” In A New Companion to Digital Humanities, edited by S. Schriebman, R. Siemans, and J. Unsworth, 22–41. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell.

- King, T. F. 2010. “My Historic Environment.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 1 (1): 103–104. doi:10.1179/175675010x12662480108992.

- Kristiansen, K. 1985. “Post-Depositional Formation Processes and the Archaeological Record.” In Archaeological Formation Processes: The Representativity of Archaeological Remains from Danish Prehistory, edited by K. Kristiansen, 7–11. Copenhagen: Nationalmuseets Forlag.

- Larrain, A. Á., and M. K. McCall. 2018. “Participatory Mapping and Participatory GIS for Historical and Archaeological Landscape Studies: A Critical Review.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 26 (2): 643–678. doi:10.1007/s10816-018-9385-z.

- Larsson, Å. M., M. Smith, R. Sohlenius, and T. Klafver. 2017. “Digitising the Archaeological Process at the Swedish National Heritage Board: Producing, Managing and Sharing Archaeological Information.” Internet Archaeology 43. doi:10.11141/ia.43.6.

- Lee, E. 2005. “Building Interoperability for United Kingdom Historic Environment Information Resources.” D-Lib Magazine 11 (6): 179–185. doi:10.1045/dlib.magazine.

- Lee, E. 2012. “‘Everything We Know Informs Everything We Do’: A Vision for Historic Environment Sector Knowledge and Information Management.” The Historic Environment: Policy & Practice 3 (1): 28–41. doi:10.1179/1756750512z.0000000006.

- Magnusson Staaf, B. 2000. “The Rise and Decline(?) of the Modern in Sweden: Reflected through Cultural Resource Management Archaeology.” Current Swedish Archaeology 8: 179–194. https://lup.lub.lu.se/search/publication/322c475e-8e6d-4f6d-a1d8-b597537671ac

- May, K. 2018. “Heritage Information Access Strategy.” Historic England. Accessed 12 March 2018. https://historicengland.org.uk/research/support-and-collaboration/heritage-information-access-strategy/

- Megill, A. 2007. Historical Knowledge, Historical Error: A Contemporary Guide to Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government. 2012. National Planning Policy Framework. London: HMSO.

- Montella, M. 2015. “The Post-Modern Context.” In Cultural Heritage and Value Creation: Towards New Pathways, edited by G. M. Golinelli, 1–6. Cham: Springer International Publishing Switzerland.

- The National Archives. 2018. “The Re-Use of Public Sector Information Regulations.” Accessed 18 July 2018. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2015/1415/regulation/15/made

- Newman, M. 2011. “The Database as Material Culture.” Internet Archaeology 29. doi:10.11141/ia.29.8.

- Nourse, N., P. Insole, and J. Warren. 2017. “Participatory Heritage.” In Having a Lovely Time: Localized Crowdsourcing to Create a 1930s Street View of Bristol from a Digitized Postcard Collection, edited by H. Roued-Cunliffe and A. Copeland, 153–162. London: Facet Publishing.

- Olsson, T., and A. Svensson. 2013. “Reaching and Including Digital Visitors: Swedish Museums and Social Demand.” In The Digital Turn: User’s Practices and Cultural Transfromations, edited by P. Runnel, P. Pruulman-Vengerfedlt, P. Viires, and M. Laak, 45–60. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Academic Research.

- Outstories Bristol. 2018. “Mapping LGBT+ Bristol.” Accessed 20 November 2018. http://outstoriesbristol.org.uk/map/#osb/kyp/115

- Phillips, C. W. 1959. “Archaeology and the Ordnance Survey.” Antiquity 33 (131): 195–204. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00027496.

- Pruulman-Vengerfeldt, P., P. Runnel, M. Laak, and P. Viires. 2013. “The Challenge of the Digital Turn.” In The Digital Turn: User’s Practices and Cultural Transformations, edited by P. Runnel, P. Pruulman-Vengerfeldt, P. Viires, and M. Laak, 7–13. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang Academic Reserch.

- Riksantikvarieämbetet. 2018. “Bakgrund till Fornminnesinformationen.” Riksantikvarieämbetet. Accessed 1 March 2018. https://www.raa.se/hitta-information/fornsok/om-fornsok/bakgrunden-till-fornsok/

- Roued-Cunliffe, H., and A. Copeland. 2017. “Introduction: What Is Participatory Heritage?.” In Participatory Heritage, edited by H. Roued-Cunliffe and A. Copeland, XV–XXI. London: Facet Publishing.

- Rundkvist, M. 2010. “Prospects for Sweden.” Antiquity 84 (325): 848–852. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00100262.

- Schnapp, A. 1997. The Discovery of the Past. Translated by Ian Kinnes and Gillian Varndell. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

- Smith, M. J. 2015. “The Digital Archaeological Workflow: A Case Study from Sweden.” In CAA 2014 – 21st Century Archaeology, Concepts, Methods and Tools. Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology, edited by F. Giligny, F. Djindjian, L. Costa, P. Moscati, and S. Robert, 215–220. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Soneryd, L., and E. Lindh. 2018. “Citizen Dialogue for Whom? Competing Rationalities in Urban Planning, the Case of Gothenburg, Sweden.” Urban Research & Practice 1–17. doi:10.1080/17535069.2018.1436721.

- South Downs National Park Authority. 2018. “Historic Environment Records.” South Downs National Park Authority. Accessed 6 March 2018. https://www.southdowns.gov.uk/discover/heritage/secrets-of-the-high-woods/historic-environment-records/

- Tahvilzadeh, N. 2015. “Understanding Participatory Governance Arrangements in Urban Politics: Idealist and Cynical Perspectives on the Politics of Citizen Dialogues in Göteborg, Sweden.” Urban Research & Practice 1–17. doi:10.1080/17535069.2015.1050210.

- Thompson, I. 2014. “HER Services and Research Projects in England.” ALGAO. Accessed 15 July. https://www.algao.org.uk/sites/default/files/documents/HER_Services_and_Research_projects_in_England_final_version.pdf.

- Waterton, E. 2005. “Whose Sense of Place? Reconciling Archaeological Perspectives with Community Values: Cultural Landscapes in England.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 11 (4): 309–325. doi:10.1080/13527250500235591.

- Westberg Gabriel, L., and T. Jenssen. 2017. “Who Is the Expert in Participatory Culture?” In Participatory Heritage, edited by H. Roued-Cunliffe and A. Copeland, 87–97. London: Facet Publishing.

- Worcester City Council. 2016. “Capitalising on Pokemon Craze Will Entice Visitors to Historic Worcester.” Worcester City Council, January 9. Accessed 2017. http://www.worcester.gov.uk/news-alerts/-/blogs/capitalising-on-pokemon-craze-will-entice-visitors-to-historic-worcester