Abstract

Transthyretin hereditary amyloid polyneuropathy, also traditionally known as transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy (ATTR-FAP), is a rare, relentless, fatal hereditary disorder. Tafamidis, an oral, non-NSAID, highly specific transthyretin stabilizer, demonstrated safety and efficacy in slowing neuropathy progression in early-stage ATTRV30M-FAP in a 1.5-year, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, and 1-year open-label extension study, with a second long-term open-label extension study ongoing. Subgroup analysis of the effectiveness of tafamidis in the pivotal study and its open-label extensions revealed a relatively cohesive cohort of patients with mild neuropathy (i.e. Neuropathy Impairment Score for Lower Limbs [NIS-LL] ≤ 10) at the start of active treatment. Early treatment with tafamidis for up to 5.5 years (≥1 dose of tafamidis meglumine 20 mg once daily during the original trial or after switching from placebo in its extension) resulted in sustained delay in neurologic progression and long-term preservation of nutritional status in this cohort. Mean (95% CI) changes from baseline in NIS-LL and mBMI were 5.3 (1.6, 9.1) points and −7.8 (−44.3, 28.8) kg/m2 × g/L at 5.5 years, respectively. No new safety issues or side effects were identified. These data represent the longest prospective evaluation of tafamidis to date, confirm a favorable safety profile, and underscore the long-term benefits of early intervention with tafamidis.

Trial Registration: ClincalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00409175, NCT00791492, and NCT00925002.

Introduction

Transthyretin hereditary amyloid polyneuropathy, traditionally called familial amyloid polyneuropathy (ATTR-FAP), is a rare, relentless, fatal, autosomal dominant genetic disorder caused by mutations in the TTR gene, which destabilize the tetrameric structure of TTR protein, causing it to dissociate, misfold, and form amyloid deposits in nerve tissues, the heart, and other organs [Citation1,Citation2]. Of more than 100 different TTR mutations linked to ATTR-FAP, the most common variant is the TTRV30M [protein variant including 20-amino acid signal peptide, p.(V50M)] mutation with large endemic foci in Portugal, Japan, Sweden, and Brazil [Citation2,Citation3]. ATTR-FAP is characterized by amyloid deposition in the peripheral nervous system, resulting in a progressive and severely debilitating sensorimotor and autonomic polyneuropathy [Citation1,Citation4]. Early neuropathic symptoms include impairment of temperature and pain sensation in the feet, erectile dysfunction, alternating constipation and diarrhea, sweating abnormalities, or postural hypotension [Citation1,Citation4]. Other common clinical features of ATTR-FAP are inexplicable weight loss, cardiac arrhythmia, renal impairment, and ocular involvement [Citation1,Citation5]. If left untreated, ATTR-FAP has a clinical course that is characterized by pain and progressive disability, leading to death on average within 10 years after symptom onset [Citation1].

Liver transplantation and TTR stabilization represent the current treatment options for ATTR-FAP [Citation6,Citation7]. Liver transplantation, which has historically been the standard of care for mild or moderate ATTR-FAP [Citation1], removes the primary source of circulating mutant TTR and may slow or halt neuropathy progression in a restricted group of patients with early-stage disease and primarily the V30M mutation who can withstand the invasive surgical procedures and subsequent life-long immunosuppressive therapy [Citation8]. With successively stricter selection criteria in terms of disease duration, nutritional status, and patient age applied over the past 20 years, liver transplant was associated with a 15-year survival rate of nearly 80% in patients with early-onset ATTRV30M-FAP (i.e. disease onset before 50 years of age) [Citation8]. Interestingly, data from the Familial Amyloidotic Polyneuropathy World Transplant Registry show a notable decline in liver transplantations since 2008 that is possibly related to the approval of tafamidis [Citation8], and there is a growing consensus that noninvasive treatments with broader applicability to the diverse phenotypes seen in TTR amyloidosis are needed [Citation6,Citation7,Citation9,Citation10].

Tafamidis, an oral, non-NSAID, highly specific TTR stabilizer, is emerging as the new standard of care for ATTR-FAP and remains the only medicine approved to delay peripheral neurologic impairment in ATTR-FAP. Tafamidis is presently approved in the European Union and several countries in Latin America and Asia, with several hundred patients treated clinically to date [Citation11,Citation12].

The efficacy and safety of tafamidis was demonstrated in an 18-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled registration trial in 128 patients with early-stage ATTRV30M-FAP from Europe and Latin America [Citation13]. Pre-specified analyses of five measures of clinical disease progression (including Neuropathy Impairment Score for Lower Limbs [NIS-LL], small and large fiber measures of neuropathy, modified body mass index [mBMI], and Norfolk Quality of Life-Diabetic Neuropathy total score), favored tafamidis over placebo, with significant positive treatment group differences in NIS-LL total score, small fiber measures, and mBMI at month 18 [Citation13].

Following the registration trial [Citation13], patients originally assigned to receive tafamidis who continued tafamidis treatment in the 1-year open-label extension study had stable rates of change in NIS-LL; whereas patients who had previously received placebo and switched to tafamidis during the open-label extension had a reduction in their rate of change in NIS-LL [Citation14]. All patients who completed the 1-year extension study were eligible for enrollment in a second and ongoing open-label extension study to evaluate the long-term safety and efficacy of tafamidis (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00925002). The current analysis focuses on the long-term effects of tafamidis in patients with mild neuropathy at treatment start. The long-term safety and disease progression trajectory for patients with ATTRV30M-FAP and a low level of baseline disease severity at treatment start (i.e. NIS-LL ≤ 10) over 5.5 years of tafamidis treatment are described.

Methods

Analysis population and study designs

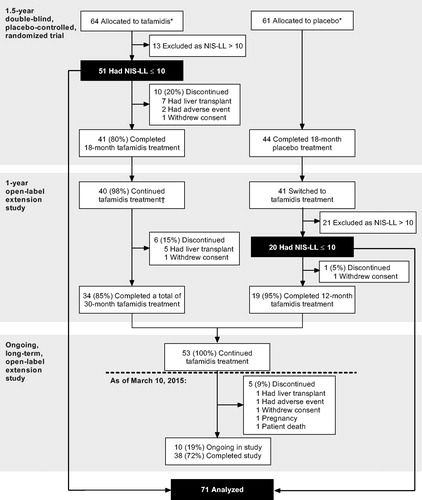

Patients between the ages of 18 and 75 years with early-stage, biopsy-confirmed ATTR-FAP due to a documented TTRV30M mutation at enrollment into the registration trial were included in this analysis if they (a) received at least one dose of tafamidis in the registration trial [Citation13] or its 12-month extension [Citation14], (b) had a baseline NIS-LL total score ≤10 points just prior to the first dose of tafamidis (i.e. very early Coutinho Stage 1 disease [Citation4,Citation15]), and (c) had follow-up data available. Patients self-administered oral tafamidis meglumine (20 mg soft gelatin capsule once daily) since the start of the registration trial or after switching from placebo to tafamidis at the start of the 12-month extension study (). Full details regarding the double-blind trial and 1-year open-label extension study have been published previously [Citation13,Citation14,Citation16]. The ongoing long-term extension study was initiated in August 2009 for up to 10 years or until study participants have access to tafamidis for ATTR-FAP via prescription (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00925002).

Figure 1. Analysis population and patient disposition. *All randomized patients who received at least one dose of study medication and had at least one follow-up assessment. †One patient who completed the tafamidis arm of the double-blind trial did not enroll in the open-label extension study, as he/she wanted to become pregnant. NIS-LL: Neuropathy Impairment Score for the Lower Limbs.

All study protocols were approved by the local scientific ethical committees and regulatory authorities and were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. All patients provided written informed consent and re-consent prior to their inclusion in the studies.

Efficacy and safety assessments

Efficacy and safety assessments were scheduled for weeks 2, 4, 8, and 12, and at months 6, 9, 12, and 18 during conduct of the double-blind study; at week 6 and months 3, 6, and 12 of the completed open-label extension study; and every 3 months (safety) or annually (efficacy) during the ongoing open-label extension study.

Disease severity and the impact of tafamidis on neurologic progression over time were evaluated using the NIS-LL, a validated instrument for assessing neuropathy progression in ATTR-FAP previously used to detect change in severity of diabetic polyneuropathy [Citation13,Citation14,Citation17]. The NIS-LL quantifies the neurologic examination by measuring motor, sensory, and reflex functions in the lower limbs, which are most affected in early-stage ATTR-FAP [Citation13]. The NIS-LL total score is obtained by adding subscale scores in each lower limb for muscle weakness, reflexes, and sensation to yield a result on a scale that ranges from 0 (normal) to 88 (absence of all activity in the lower limbs) [Citation13]. During the original trial and first 12-month extension study, the NIS-LL was assessed twice at each study visit, separated by 24 h to 1 week, with the results reported as the average of the two tests. In the ongoing long-term extension study single NIS-LL assessments were obtained.

Nutritional status was assessed using the mBMI [Citation18]. The mBMI compensated for potential edema caused by malnutrition due to gastrointestinal dysfunction, and is calculated by multiplying BMI (kg/m2) with serum albumin concentration (g/L) [Citation18].

Safety and tolerability were measured by adverse event (AE) monitoring, physical and neurologic examinations, vital signs, and clinical laboratory evaluations. All observed or volunteered AEs, regardless of severity or suspected relation to tafamidis, were documented during the studies. Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (version 18.0) coding was applied. The study investigators rated the intensity of each AE (mild, moderate, or severe) and categorized the relationship between each AE and study drug.

Statistical analysis

The cutoff point for this intent-to-treat analysis was 10 March 2015. Baseline was defined as the last measurement before the first active dose of tafamidis. Individual and mean (standard deviation [SD] or 95% confidence interval [CI]) change from baseline in NIS-LL and mBMI over time was analyzed using SAS® (SAS® Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The analysis was descriptive in nature (i.e. no formal hypotheses were tested) and based on observed data only (i.e. missing data were not imputed).

Results

Patients and treatment

Seventy-one of 128 patients who entered the double-blind trial met the criteria for evaluation and were included in the analysis. Of these, 72% (51/71) initiated tafamidis treatment at the start of the double-blind study and 28% (20/71) after switching from placebo to tafamidis in the first extension trial (). At the time of the data cutoff, 22/71 patients (31%) had discontinued tafamidis treatment during the three studies (59% (13/22) due to availability of a donor liver), 1/71 (1.4%) had not enrolled in the open-label extension study after completing the double-blind trial as they wanted to become pregnant, and 38/71 (54%) had completed the third study when tafamidis became approved for the treatment of ATTR-FAP and available in their country. Ten of 71 patients (14%) were still receiving tafamidis treatment within the ongoing long-term extension study.

The baseline characteristics of the analysis population at the last assessment before the first dose of tafamidis were representative of an early-stage ATTR-FAP population (). At baseline, only modest impairment was observed of NIS-LL, and nutritional status was well preserved based on the mBMI [Citation13,Citation18]. Median (range) age at disease onset was 32.0 (22–65) years. Based on medical history terms related to ATTR-FAP, the most common ongoing symptoms at baseline were paraesthesia and neuralgia, which affected 56.3% (40/71) and 35.2% (25/71) of patients, respectively (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics at baselineTable Footnotea.

Excluding the 10 patients who were ongoing in the second extension study, the median exposure time to tafamidis (range) was 3.9 (0.5–5.9) years (n = 61). The maximum exposure time to tafamidis was 7.5 years (n = 3) at the time of this analysis.

Longitudinal analysis of neurologic impairment and malnutrition

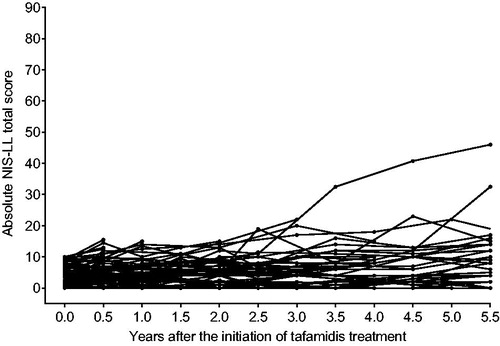

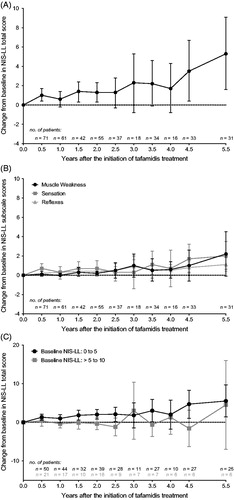

A baseline NIS-LL ≤ 10 at treatment start was associated with a minimal level of neurologic disease progression over time (). The mean (95% CI) change from baseline in NIS-LL was 0.6 (−0.2, 1.4) at 1 year, 1.3 (0.3, 2.3) at 2 years, 2.2 (−0.1, 4.6) at 3.5 years, 3.5 (0.4, 6.7) at 4.5 years, and 5.3 (1.6, 9.1) points after 5.5 years of tafamidis treatment (). Muscle weakness, loss of sensation, and loss of reflex contributed to the small increase in NIS-LL total score (). The main sensory impairment detected at baseline and during tafamidis treatment was reduced perception of pin-prick, soft touch, and vibration in the toe, and muscle weakness occurred primarily in the toe with little or no dysfunction in the ankle or knee (Supplementary Table S2). Furthermore, reductions in reflexes were detected primarily in the triceps surae muscle, with very minor reductions detected also in the quadriceps femoris muscle at 5.5 years. Additional categorization of patients by their baseline NIS-LL scores as either 0–5 (n = 50) or >5–10 (n = 21) at the start of treatment revealed similar disease trajectories to the full analysis population ().

Figure 2. Absolute NIS-LL total scores throughout long-term tafamidis treatment for each of the 71 patients with baseline NIS-LL ≤ 10 at the last assessment before the first dose of tafamidis. NIS-LL: Neuropathy Impairment Score for the Lower Limbs.

Figure 3. Mean (95% CI) change from baseline in NIS-LL throughout 5.5 years of tafamidis treatment among 71 patients with baseline NIS-LL ≤ 10 at last assessment before first dose of tafamidis. Analyses were performed using observed cases. Year 5 data were excluded due to limited data (n = 2). Mean change in NIS-LL total score (Panel A). Mean change in three NIS-LL subscale scores, muscle weakness, sensation, and reflexes (Panel B). The subscales range from 0 to 64 (muscle weakness), 0 to 16 (sensation), or 0 to 8 (reflexes), with higher values indicating greater neurologic deficit. Mean (95% CI) baseline NIS-LL sub-scores in the analysis population were 0.2 (0.0–0.4) for muscle weakness, 3.4 (2.8–4.0) for sensation, and 0.5 (0.2–0.8) for reflexes. Subgroup analysis of the mean change in NIS-LL total score in patients with baseline NIS-LL score of 0–5 (n = 50) versus those with a baseline NIS-LL score of >5–10 (n = 21) (Panel C). Mean (95% CI) baseline NIS-LL total scores were 2.5 (2.0–2.9) and 8.1 (7.4–8.8) for the two subgroups. CI: confidence interval; NIS-LL: Neuropathy Impairment Score for the Lower Limbs.

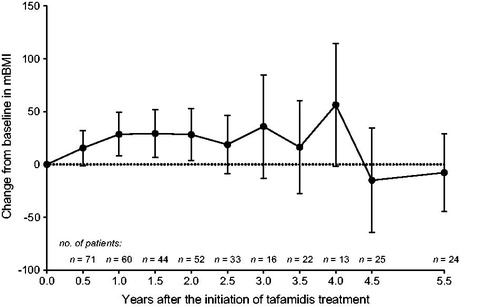

Nutritional status did not significantly deteriorate during long-term tafamidis treatment based on a mean (95% CI) change from baseline in mBMI of 28.5 (7.9, 49.1) at 1 year, 28.2 (3.5, 52.9) at 2 years, 16.3 (−27.5, 60.1) at 3.5 years, −15 (−64.6, 34.7) at 4.5 years, and −7.8 (−44.3, 28.8) kg/m2 × g/L at 5.5 years ().

Figure 4. Mean (95% CI) change from baseline in mBMI throughout 5.5 years of tafamidis treatment among 71 patients with baseline NIS-LL ≤ 10 at last assessment before first dose of tafamidis. Analyses were performed using observed cases. Year 5 data were excluded due to limited data (n = 2). CI: confidence interval; mBMI: modified body mass index.

Safety and tolerability

No new safety issues or side effects of tafamidis were identified in this long-term analysis. The most common all-causality treatment-emergent AEs are listed in Supplementary Table S3, and reflect the long observation period. AEs of urinary tract infection and vaginal infection were experienced by 28.2% and 9.9% of patients, respectively; of these, 40.0% and 14.3% were considered to be possibly related to tafamidis treatment. Episodes of diarrhea were reported in 22.5% of patients, 43.8% of these events were assessed as possibly treatment-related. During up to 5.5 years of follow-up, 3/71 patients (4%) discontinued treatment due to treatment-emergent AEs, including 1 AE of diarrhea judged to be possibly related to the underlying ATTR-FAP, 1 AE of urticaria, and 1 AE of renal impairment, all considered to be possibly treatment-related. None of these 3 AEs recovered after discontinuation. In addition, 1 patient died of lymphoma 10 days after the last dose of tafamidis. The treatment-emergent lymphoma was not judged to be treatment-related.

Discussion

The present analysis represents the longest prospective evaluation to date of tafamidis, an oral treatment for ATTR-FAP approved in Europe and several Asian and Latin-American countries. Results showed a sustained delay in neurologic progression and preservation of nutritional status for up to 5.5 years following early treatment with tafamidis. A minimal level of disease progression as measured by NIS-LL was observed in patients with ATTRV30M-FAP and low baseline disease severity upon initiation of tafamidis, defined as a NIS-LL total score ≤ 10 at treatment start. The mean change from baseline in NIS-LL increased slowly to 5.3 points at 5.5 years, with an increase in mean change from baseline from 3.5 to 5.3 points in the last year. Importantly, the results in the current population do not preclude favorable effects in patients with greater baseline severity. Tafamidis treatment was generally well tolerated. The type and incidence of treatment-emergent AEs in this analysis population are consistent with previous studies and reflect the underlying disease of ATTR-FAP and the long observation period. No new safety issues or side effects were identified.

The results were from a post hoc analysis of patients with ATTRV30M-FAP who received tafamidis 20 mg once daily in three sequential studies. Neurologic disease progression was assessed from a single outcome measure, NIS-LL, which may have missed changes in small fiber nerve function. The lack of a direct control group for comparison limits the ability to determine whether the observed low rates of neuropathic progression were a consequence of tafamidis treatment or of the natural history of the disease itself. The use of natural history data as a historical comparator, a common approach in rare disease drug development, is challenging due to the dependence on, and the need to adjust for, baseline severity levels when examining the rate of change in NIS-LL. Published estimates of the mean rate of natural disease progression as measured by NIS-LL range from ∼4 points per year (i.e. 0.34 points/month) in 33 placebo-treated patients with early-stage ATTRV30M-FAP (mean [SD] baseline NIS-LL, 11.6 [14.5] points) [Citation14], to ∼6 points per year (i.e. 12.1 points over 2 years) in a heterogeneous ATTR-FAP population of 66 placebo-treated patients some of whom had more advanced disease (mean [SD] baseline NIS-LL, 27.2 [24.5] points) [Citation19].

In conclusion, early intervention with tafamidis led to minimal disease progression over 5.5 years in this cohort of patients with mild ATTR-FAP at treatment start and was accompanied by a favorable long-term side-effect profile. As part of good clinical practice, patients taking tafamidis should receive regular multifaceted clinical assessments of neurologic, cardiac, and renal function at referral centers in order to fully assess patient response to treatment. Overall, these findings underscore the long-term benefits, efficacy, and safety of early intervention with tafamidis and support earlier work, suggesting that tafamidis treatment should be initiated as early as possible in patients with symptomatic ATTR-FAP [Citation14].

| Abbreviations | ||

| AE | = | adverse event |

| ATTR-FAP | = | transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy |

| CI | = | confidence interval |

| mBMI | = | modified body mass index |

| NIS-LL | = | Neuropathy Impairment Score for the Lower Limbs |

| SD | = | standard deviation |

| TTR | = | transthyretin |

Supplementary material available online.

downloadFromZipFile.pdf

Download PDF (51.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors express their sincere gratitude and appreciation to all participating patients, investigators, and their staff; without their help these studies would not have been possible.

All named authors meet the ICMJE criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All authors were responsible for the initial conception and drafting of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

This study was sponsored by Pfizer. Editorial support for the development of this manuscript was provided by Malcolm Darkes and Susanne Vidot of Engage Scientific Solutions, Horsham, UK, and was funded by Pfizer.

M.W.C. reports receiving support from Pfizer as a clinical investigator, as a consultant, and for scientific meeting expenses (travel, accommodation, and registration).

L.A., D.K., J.S., and H.L. are employees of Pfizer.

B.G., an employee of inVentiv Health, was a paid contractor to Pfizer in association with providing statistical support for this analysis and for the development of this manuscript.

References

- Ando Y, Coelho T, Berk JL, Cruz MW, Ericzon BG, Ikeda S, Lewis WD, et al. Guideline of transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis for clinicians. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013;8:31

- Sekijima Y. Transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis: clinical spectrum, molecular pathogenesis and disease-modifying treatments. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015;86:1036–43

- Rowczenio DM, Noor I, Gillmore JD, Lachmann HJ, Whelan C, Hawkins PN, Obici L, et al. Online registry for mutations in hereditary amyloidosis including nomenclature recommendations. Hum Mutat 2014;35:E2403–12

- Coutinho P, Martins da Silva A, Lopes Lima J, Resende Barbosa A. Forty years of experience with type I amyloid neuropathy: review of 483 cases. In: Glenner GG, Pinho e Costa P, Falcao de Freitas A, eds. Amyloid and amyloidosis. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica; 1980:88–98

- Conceição IM, González-Duarte A, Obici L, Harmut HH, Simoneau D, Ong ML, Amass L. “Red-flag” symptom clusters in transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Peripher Nerv Syst 2015;21:5–9

- Adams D. Recent advances in the treatment of familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2013;6:129–39

- Planté-Bordeneuve V. Update in the diagnosis and management of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Neurol 2014;261:1227–33

- Ericzon BG, Wilczek HE, Larsson M, Wijayatunga P, Stangou A, Pena JR, Furtado E, et al. Liver transplantation for hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis: after 20 years still the best therapeutic alternative? Transplantation 2015;99:1847–54

- Hanna M. Novel drugs targeting transthyretin amyloidosis. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2014;11:50–7

- Sekijima Y, Tojo K, Morita H, Koyama J, Ikeda S. Safety and efficacy of long-term diflunisal administration in hereditary transthyretin (ATTR) amyloidosis. Amyloid 2015;22:79–83

- Scott LJ. Tafamidis: a review of its use in familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Drugs 2014;74:1371–8

- Waddington Cruz M, Benson M. A review of tafamidis for the treatment of transthyretin-related amyloidosis. Neurol Ther 2015;4:61–79

- Coelho T, Maia LF, Martins da Silva A, Waddington Cruz M, Planté-Bordeneuve V, Lozeron P, Suhr OB, et al. Tafamidis for transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurology 2012;79:785–92

- Coelho T, Maia LF, da Silva AM, Cruz MW, Planté-Bordeneuve V, Suhr OB, Conceicao I, et al. Long-term effects of tafamidis for the treatment of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Neurol 2013;260:2802–14

- Coelho T, Merkies I, Vinik A, Vinik EJ, Chan J, Packman J, Grogan DR. Relationship between objective measures of neuropathy and quality of life in stages of severity of transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy. Abstract P-098 of the XII International Symposium on Amyloidosis, April 18–21, 2010, Rome, Italy. Amyloid 2010;17 Suppl 1:138

- Suhr OB, Conceição IM, Karayal ON, Mandel FS, Huertas PE, Ericzon BG. Post hoc analysis of nutritional status in patients with transthyretin familial amyloid polyneuropathy: impact of tafamidis. Neurol Ther 2014;3:101–12

- Dyck PJ, Davies JL, Litchy WJ, O’Brien PC. Longitudinal assessment of diabetic polyneuropathy using a composite score in the Rochester Diabetic Neuropathy Study cohort. Neurology 1997;49:229–39

- Suhr O, Danielsson A, Holmgren G, Steen L. Malnutrition and gastrointestinal dysfunction as prognostic factors for survival in familial amyloidotic polyneuropathy. J Intern Med 1994;235:479–85

- Berk JL, Suhr OB, Obici L, Sekijima Y, Zeldenrust SR, Yamashita T, Heneghan MA, et al. Repurposing diflunisal for familial amyloid polyneuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310:2658–67