ABSTRACT

In visual narratives like comics, not only do comprehenders need to track shifts in characters, space, and time, but they do so across a spatial layout. While many scholars and comic artists have speculated about connections between meaning and layout in comics, few empirical studies have examined this relationship. We investigated whether situational changes between time, characters, or space interacted with page layouts, by looking at across-page, across-constituent, and within-constituent transitions in a corpus of 134 annotated comics from North America, Europe, and Asia. Panels shifting within constituents (e.g., while moving within a row) changed the situation the least, while those across pages and across constituents (like in a row break) had more situational changes. The boundary of a page especially aligned with changes in spatial location of the scene. In addition, discontinuous changes primarily aligned with across-page transitions. Cross-cultural analyses indicated that Asian comics convey meaning across panels in ways that are relatively less constrained by layouts, while American and European comics use the page as a unit to group and segment spatial information. Such results indicate a partial correspondence between layout and meaning, but with different cultural constraints.

Introduction

The understanding of narratives involves keeping track of the ever-changing flow of meaningful information across the form of media. In visual narratives like comics, depictions of characters, spaces, and events are connected across sequential images embedded within a spatial layout, like a comic page. While both scholars and creators have maintained an assumption of an interaction between a layout (i.e., form) and meaning (Caldwell, Citation2012; Groensteen, Citation2007), few works have examined such a connection within the structures of actual comics. Here, we seek evidence for this interaction of sequential meaning-making and the affordances of the visuospatial layout in comics by analyzing a corpus of comics from North America, Europe, and Asia.

To comprehend visual narratives, a reader needs to track changes in representations of characters, spatial locations, and events across panels. Many theories have focused on meaningful relations between juxtaposed images. These approaches have often categorized types of “panel transitions” with an emphasis on the inferences that readers make between images (e.g., McCloud, Citation1993). Such shifts have been claimed to operate both between adjacent and non-adjacent panels (Gavaler & Beavers, Citation2020), or build to form larger structures (Bateman & Wildfeuer, Citation2014).

This flow of meaningful information is suggested to feed into a reader’s situation model (Cohn, Citation2020b; Loschky et al., Citation2020), which is a constructed mental representation of a discourse integrated with the reader’s prior knowledge (Kintsch & van Dijk, Citation1978; Zwaan & Radvansky, Citation1998). While situation models are built across narratives of all modalities (Gernsbacher, Citation1985; Magliano et al., Citation2020), the properties of the modalities can contribute to their construction (Loschky et al., Citation2020). In visual narrative comprehension, readers first recognize the elements in the visual surface of a panel through mechanisms of scene perception and attentional selection, which may be informed by the elements or properties shared across images (Loschky et al., Citation2020). This extracted information can connect to semantic representations, which feed into the situation model of the ongoing scene. As a reader encounters new information (such as a new character or location), this situation model becomes updated, and inferences are made to reconcile information that cannot be readily mapped together (Cohn, Citation2020b). In contrast to many of the theories of meaning relations across panels in visual narratives (Bateman & Wildfeuer, Citation2014; Gavaler & Beavers, Citation2020; McCloud, Citation1993), from this psychological perspective, situational changes are non-exclusive since many dimensions of meaning can change at once, and they are non-binary since changes may be incremental (i.e., full, or partial changes) as in (a).

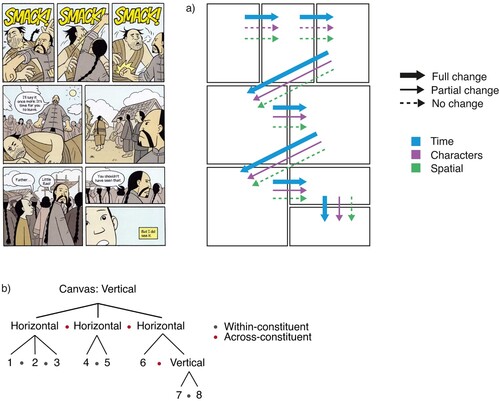

Figure 1. (a) The situational changes (i.e., time, characters, and spatial location) and (b) the layout structure analyzed in Boxers © Gene Yang (2013, 13, First Second).

Because such situational changes occur both across adjacent and non-adjacent panels, this semantic information may be organized by interfacing with other aspects of visual narratives’ architecture. For example, meaningful connections have been argued to interact with a hierarchic narrative structure that organizes meaning using categories and constituent structures (Cohn, Citation2013b). In this regard, meaning changes might overlap with or signal the boundaries of narrative constituents. This separation in structures is supported by research in cognitive neuroscience showing dissociative neural responses to manipulations of narrative and meaning (Cohn, Citation2020a).

Since both narrative and meaning need to manifest physically across sequential images in a page layout (i.e., form), the aspects of spatial layout also may interact with meaning structures, such as a way to segment and group meaning spatially. As such, many theories have indeed posited interactions between layout and meaning. One way people argue for a relationship between layout and meaning is the direct correspondence between time and layout. McCloud (Citation1993) argued for a notion of “time = space” such that each panel shows a different moment, and the distance between panels interacts with a fictive time passage. A strong view of this idea would imply that physical changes between rows or columns in a layout should signal more temporal change than between panels within a row or column.

In addition, the “meaningfulness” of layouts has been proposed in terms of their functional expressiveness (Caldwell, Citation2012; Groensteen, Citation2007; Peeters, Citation1998) such as being conventional, decorative, or experimental. Other work has posited that meaningful relations between panels directly connect across the analog surface of a layout, supposedly in ways that belie a linear reading order (Bateman & Wildfeuer, Citation2014). Natsume (Citation1997) has also postulated that in the context of Japanese manga, panel arrangements compress and release meaning , which is akin to the prosody of speech. Differences in size, shapes, and transitions of panels were suggested to influence readers’ perceptions about meaning (Holt & Teppei, Citation2021).

Yet, despite this, layouts have their own properties, which are independent of the meanings, expressed by the arranged panels (Bateman et al., Citation2021; Cohn, Citation2013a, Citation2020a; Pederson & Cohn, Citation2016). The most basic or default physical organization is a pure grid in which panels are ordered laterally (ex. left-to-right in American comics, right-to-left in Japanese manga) and then down to form rows with contiguous gaps between panels. This spatial organization maintains a Z-path of reading panels. However, panels can be misaligned to become staggered, or they can be organized into columns. Further, panels can also be stacked in a column adjacent to a big horizontal panel (Cohn, Citation2020a). This misalignment might require alternative navigation routes, pushing a reader downward instead of moving along the Z-path.

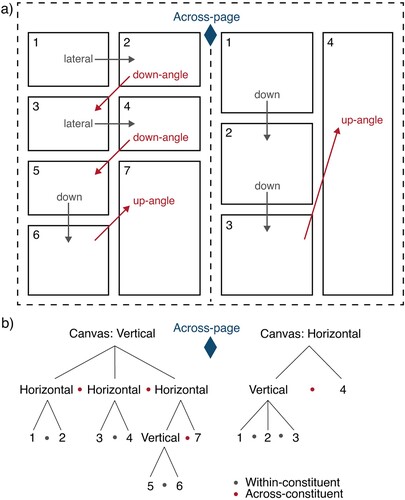

The physical organization of panels alone does not determine how a reader navigates through them though. Groupings of embedded rows and columns form a hierarchic organization of constituents (Cohn, Citation2013b; Tanaka et al., Citation2007) which a reader uses to navigate through a visual surface of a page. In other words, the reader constructs this “assemblage structure” in their mind as they engage with the layout (Cohn, Citation2013b). The grouping of panels in rows and columns might also cue changes in this hierarchic structure. For example, moving at a downward angle might signal changes between rows or an upward angle might signal changes between columns. In this assemblage structure, we refer to these navigational shifts as within-constituent (such as in a row) or across-constituent (such as moving across a row break) transitions, as in (b).

These constituent structures might be influenced by conventions of reading paths, but may also be influenced by Gestalt principles in how they group together (e.g., Wertheimer, Citation1923). For instance, proximity or alignment of panels have been shown to push readers to group panels in ways that belie the Z-path (Cohn, Citation2013a; Wertheimer, Citation1923). These properties influence readers to choose consistent groupings of panels in layouts, even when panels have no contents (Cohn, Citation2013a, Cohn & Campbell, Citation2015). Thus, the physical properties of the form might motivate the reading path, without relying on meaning.

Nevertheless, given the widespread ideas that layout interacts with meaning, we sought evidence for such an interaction. Specifically, might certain types of situational changes coincide with layout constituents? Would spatial changes occur more while crossing pages, given the greater spatial distance between pages? We investigate this issue by looking directly at how these phenomena appear in actual comics of the world. Indeed, prior corpus analyses have examined both situational changes across panels and aspects of page layout individually. McCloud’s (Citation1993) early comparison of the “panel transitions” in comics found that Western comics shifted between actions more often than between characters and scenes. In Japanese manga, character shifts were more prominent than changes in action, while scene-related changes were similar to American and European comics. Additionally, manga also shifted between aspects of scenes showing the surrounding environment.

Similar findings were made in a larger analysis of roughly 300 comics in the Visual Language Research Corpus (VLRC: Cohn et al., CitationIn Prep). Here, meaning relations were analyzed both for full and partial changes across panels for dimensions of time, characters, and spatial location, consistent with psychological models of event indices (Loschky et al., Citation2020; Radvansky & Zacks, Citation2014; Zwaan & Radvansky, Citation1998). Time changes occurred the most, and then character and spatial location changes, respectively (Cohn, Citation2020a; Klomberg et al., Citation2022). Also, cross-cultural differences emerged in line with McCloud’s (Citation1993) preliminary findings. Comics from Asia had more changes in characters than European and American comics, while the reverse occurred for time changes. Nevertheless, those dimensions changed over time, with an increase in character changes across American mainstream comics. Time shifts first grew more and then less frequent across publication dates of comics, while overall shifts in spatial location also decreased (Bateman et al., Citation2021; Cohn, Citation2020a).

Aspects of layout have been also analyzed in data from the VLRC (e.g., Cohn, Citation2020a) and the results again suggested cross-cultural variance. Overall, lateral directions (left or right) were used the most and up-angle directions (up-right or up-left) the least. European and American Indie comics mostly maintained row-based, Z-path arrangements, using lateral directions (from left to right) followed by down-angle directions (down-left), maintaining a Z-path. Straight downward directions were notable in Asian and American mainstream comics. However, Asian comics also had the most up-angle directions, signaling a deviation from a Z-path order of reading panels (i.e., up-angle directions occur when exiting an embedded column). Additional work has found that the layout properties have also changed over time in American mainstream comics with a decrease in directions that signal a Z-path (Pederson & Cohn, Citation2016).

Along these lines, here we ask whether aspects of the constituent structure of layouts might align with the segmentation of meaning across a comic. While corpus analyses have been undertaken on both situational changes across panels in comics, and for aspects of page layout, only minimal work has examined properties of meaning and layout together. Bateman et al. (Citation2021) showed that certain layout arrangements clustered with aspects of meaning in a principal components analysis of American mainstream comics. However, no work has examined the direct interactions of changes in meaning and the hierarchic structure of page layouts themselves. Thus, here we combined the meaning and layout data in the VLRC to investigate the situational changes across pages ((a)), and across and within the constituents of layouts, as illustrated in (b).

Overall, situational discontinuity (i.e., changes in characters and location with no temporal progression) was expected to differ on the basis of layout constituents. If layout constituents exhibit a strong hierarchy in relation to meaning, we expected across-page transitions would be more discontinuous than shifting across constituents, while the latter would have more discontinuity compared to within constituents.

We also had more specific predictions for situational changes. We predicted that across-page transitions would align with the most changes, while within-constituent transitions would have the least change in meaning. This would align with the idea of the page as a segmental unit (i.e., “meta panel”, Eisner, Citation2008; “multiframe”, Groensteen, Citation2007). The boundary of crossing between pages should especially align with spatial location changes. Because location shifts occur the least in visual narratives (Cohn, Citation2020a; Klomberg et al., Citation2022), we expected them to coincide with the most eminent boundary. In addition, we posited that changes in spatial locations might align with distinct physical boundaries (pages), which would reinforce the accompanying shift in a mental model (Loschky et al., Citation2020). That is, a new page would signal the start of a new scene, both physically and cognitively.

Given that characters tend to shift more than locations (Cohn, Citation2020a; Klomberg et al., Citation2022), and if there is indeed a strong correspondence between the hierarchy of meaning and hierarchy of form, then changes in characters could be expected to overlap with the second-most eminent boundary i.e., across constituents. Since temporal progression is pervasive in visual narratives, time should not necessarily be influenced by layout constituents, unless we expect a strong mapping of situational time and physical space (McCloud, Citation1993).

Finally, we also examined whether meaning-layout relations differ cross-culturally. Prior works showed differences in both meaning (Klomberg et al., Citation2022; McCloud, Citation1993) and layout across cultures (Cohn, Citation2020a). However, we do not have specific hypotheses about whether and how this specific interaction between meaning and layout would differ across cultures since it remains an open question.

Method

Materials

We analyzed the properties of layout and situational changes in comics from the Visual Language Research Corpus (VLRC; Cohn et al., CitationIn Prep). Information about VLRC and its data can be found online at http://www.visuallanguagelab.com/vlrc and/or at its DataverseNL repository (https://do.org/10.34894/LWMZ7G). The VLRC as a whole was annotated by 12 coders in total, who each passed at least one semester of courses on Visual Language Theory (Cohn, Citation2013b), and were required to reach a threshold of 80% interrater agreement in practice sessions to be able to annotate the actual corpus. Meetings about annotations were held weekly where edge cases were discussed until consensus.

Our analysis here examined comics annotated with both information about situational changes (i.e., shifts across panels in terms of time, characters, or spatial location), and features of the page layout. Prior analyses of the VLRC have investigated these constructs separately (Cohn, Citation2020a). Out of the total 360 comic books in the VLRC, 134 stories contained annotations of both meaning changes and layout, which extended across comics from North America (United States), Europe (Sweden, France), and Asia (China, Japan, Korea). lists information about continents and publication dates of our analyzed comics in this study, and the total number of pages and panels included. More information can be found in Cohn et al. (CitationIn Prep), and the data for this specific study are found at its DataverseNL repository (https://do.org/10.34894/DMAUD0).

Table 1. Comics analyzed from VLRC.

Areas of analysis

We here examined two primary areas of analysis coded across books in the corpus: situational changes (i.e., the meaningful changes occurring across panels) and aspects of page layout (spatial relations between panels).

Situational changes. Our analysis of situational changes assessed shifts in time, characters, and spatial location between panels (Zwaan et al., Citation1995). Those situational changes were based on explicit visual changes from panel to panel. If time clearly passed between panels, it was coded as “1”. Otherwise, if time did not pass or it was ambiguous, it was a “0”. Full changes in spatial location and characters were coded as “1”. Unlike time changes, partial changes were also possible here (e.g., shifting to a different room in the same building, or adding/omitting a character while the other character(s) remained the same), and these were coded as “0.5”. When no changes in spatial location or characters occurred, they were coded as “0”.

Following the approach in Klomberg et al. (Citation2022), we also considered instances of complete situational “discontinuity”. Temporal shifts (i.e., when the time changes between panels) are considered normative for the flow of continuity while characters and spatial locations repeat. Thus, instances of situational discontinuity occurred between panels when there was no shift in time, but spatial locations and characters changed.

Layout constituents. Our primary analysis of page layout used the directionality of panels to assess the spatial flow of panels across a page. Directionality between panels was assessed based on the panels’ orientation relative to their preceding panels. Directions were approximated as the vector between the center point of a panel and its preceding panel in terms of the four primary directions (up, down, left, right) or the angles between them (down angle, up angle). The starting panel of a page was coded with the designation “new page” without directionality since it had no preceding panel on that page. Because reading orders may differ in their directionality across Western comics (left-to-right) and Japanese manga (right-to-left), we “normalized” these directions to being lateral, with angles being either down angle or up angle, as in .

Figure 2. (a) Surface panel directions (i.e., lateral, and down versus down angle, and up angle) cueing assemblage structure of transitions within and across constituents and (b) the tree structure of layout showing those constituents.

We then defined layout constituents using directionality as cues for changes in assemblage structure. We collapsed lateral and down directions as within-constituent transitions, since, as depicted in , they would signal panels ordered within a row or a column, respectively. In contrast, down-angle and up-angle directions were cues for across-constituent transitions, signaling the changes between rows (down angle) and columns (up angle), as shown in . Finally, the first panel of a page relative to its previous page was used as an indicator of “across-page” transitions.

Data analyses

Situational changes (time, characters, spatial location) were recorded between each pair of panels in a book, and proportions were calculated for all changes out of all panels per book. Situational discontinuity was then computed by collapsing the instances when location and characters shift with no time changes. Layout constituents (transitions across page, across constituents, within constituents) were also recorded and averaged per book.

We analyzed the areas of analysis mentioned above using Repeated Measures Analysis of Variances (ANOVAs), starting with analyses of proportion of situational changes and average layout constituents found in our corpus. Given the proportional nature of our data, we first log transformed all proportions to normalize the data. Due to meaningful zeroes in our corpus which cannot be log transformed, we conducted transformations on x + 1, by x being proportions. After this step, ANOVAs with three levels were used to analyze both situational changes (i.e., time, character, and spatial location) and layout constituents (i.e., transitions across pages, across constituents, and within constituents). This analysis looked at the overall proportion of these structures across comics in our corpus.

We next turned to comparisons between situational changes and layout constituents. Here we calculated additional proportions to eliminate the confound of unequal instances of layout constituents. That is, layouts may have an unequal number of constituents on a single page. Consider a comic where each page uses a 3 × 3 grid of 9 panels. Each page would thus have only 1 across-page transition (recorded at the first panel), 6 within-constituent transitions (between panels within the rows), and 2 across-constituent transitions (between panels across rows). Means related to situational changes across these dimensions would be confounded, because of the uneven amounts of changes going into each layout constituent (e.g., if there are more within-constituent shifts as we reasoned, they might automatically have more changes). Thus, to correct this difference, for each layout constituent, we calculated the proportion of the total number of each situational change out of the total number of each layout constituent per book.

We then analyzed layout constituents with situational changes out of the total number of layout constituents across continents (i.e., North America, Europe, and Asia) using a 3 (continent) x 3 (situational change) x 3 (layout constituent) Repeated Measures ANOVA. Finally, to get a sense of the broader meaningful changes occurring while navigating layouts, we compared the situational discontinuity to constituent structures across continents. Again, we analyzed relative proportions, i.e., layout constituents with discontinuity out of all layout constituents through a 3 (continent) x 3 (layout constituents with situational discontinuity) ANOVA. For significant main effects and interactions, we conducted post-hoc analyses with Holm corrections.

Results

Mean situational changes across panels

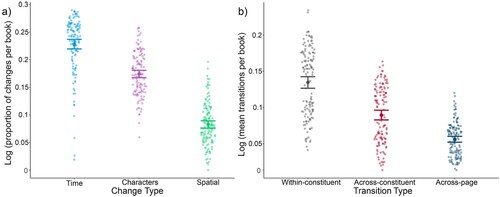

Our first analysis compared different types of situational changes (i.e., time, characters, and spatial location) occurring across the selected books in our corpus. Mean changes differed based on type of situational change, F(1, 238) = 345.240, p < .001. Specifically, time changes occurred between panels the most (all ts > 9.6, all ps < .001), while characters changed between panels more than spatial locations (t = 16.3, p < .001), as depicted in (a).

Figure 3. (a) Proportion of changes in time, characters and spatial location per book. (b) Mean numbers of layout constituents (across-page, across- and within-constituent transitions) averaged per book. Both proportions are log transformed and depicted as the colored dot, along with error bars showing standard error. Each dot represents a comic analyzed. Note the difference in scales (y-axes).

Mean layout constituents per book

We then looked at whether layout constituents (i.e., across-page, across- and within-constituent transitions) differed from each other, which was the case, F(1, 246) = 398.017, p < .001. Overall, on average books had more within- than across-constituent transitions (t = 16.1, p < .001), which occurred more than across-page transitions (t = 11.9, p < .001) as shown in (b). This followed our reasoning for relative proportions of layout segments, as described in the Methods section.

Situational changes in layout constituents

Since the average of each layout constituent per book varied from each other ((b)), our subsequent analyses looked at total number of situational change types in each layout constituents out of the total number of each layout constituent type (e.g., for time changes across pages, we calculated the total number of time changes across-page transitions out of all across-page transitions).

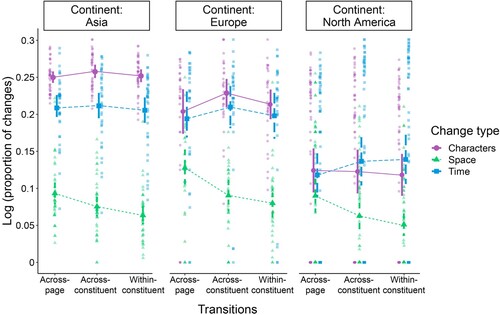

The first main effect suggested that situational changes in layout constituents differed from each other, F(1, 231) = 257.026, p < .001. As shown in , characters changed more than time (t = 2.8, p = .005), while time changes occurred more compared to spatial changes (t = 18.05, p < .001). Second, situational changes also varied based on which constituent type they occur at, F(2, 352) = 23.219, p < .001. Overall, the meaning changed more while moving across pages and across constituents than within constituents, all ts >3.2, all ps < .003. Finally, these changes also differed based on continents, F(2, 131) = 16.915, p < .001. North American comics had the fewest changes (all ts > 4.2, all ps < .001) while mean changes did not differ between European and Asian comics (t = 0.46, p = 0.645), as in .

Figure 4. The log transformed proportion of changes in layout constituents (across-page, across-constituent, and within-constituent transitions) with time, character, and spatial location changes across continents. Each dot represents a comic. Error bars represent standard error.

Interactions indicated variation in changes in time, characters, and spatial location on the basis of layout constituents (F(2, 352) = 23.219, p < .001) and of continent (F(3, 231) = 25.408, p < .001). First, although characters changed more than time across books overall (see (a)), this analysis demonstrated a different pattern for changes occurring in layout constituents. As shown in , shifts in time and characters did not differ from each other while navigating within- or across- layout constituents and crossing pages, all ps > .08. In addition, layout constituents did not influence the shifts in time. That is to say, regardless of where the transition happens, time shifted similarly and that was the case for characters as well, all ps > 0.115. However, spatial locations changed more across pages than both across and within constituents, all ts > 6.7, all ps < .001.

Second, as indicated in , time and characters shifted more in panels from Asian and European comics than North American ones (all ts > 4.1, all ps < .001) but Asian and European comics did not differ from each other (all ps > 0.440). This was not the case for spatial location changes, which shifted similarly in comics from all three continents, all ts < 1.83, all ps > 0.59. Moreover, Asian comics had a robust distinction between their situational changes. Characters shifted more than time did (t = 4.56, p < .001) while spatial location changed the least (all ts > 13.7, all ps < .001). In contrast, within both European and North American comics, character changes and time changes were comparable (all ps = 1.000) with the least changes occurring in spatial location (all ts > 7.07, all ps < .001).

Finally, a 3-way interaction arose between situational change, layout constituents and continent, F(5, 352) = 2.754, p = .016. Despite North American comics using fewer changes in spatial location than time and characters overall, all types of changes occurred in a similar fashion while moving across pages, all ps > 0.183. Moreover, comics from both North America and Europe shifted in locations more while moving across pages than in all other constituents, all ts > 4.8, all ps < .001. However, Asian comics had greater changes in spatial location while shifting into a new page compared to moving within constituents (t = 4.172, p = .006) but not across constituents (p = 1.0). Thus, this interaction further implied that the relationship found between across-page transitions and location shifts was mostly motivated by North American and European comics.

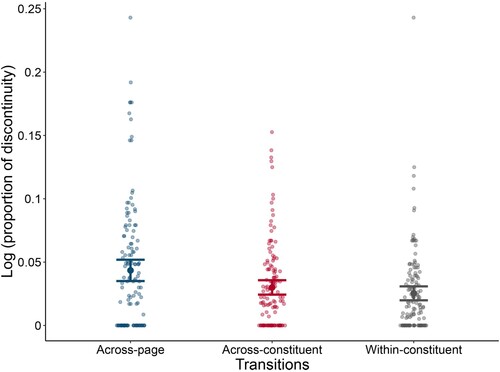

Situational discontinuity in layout constituents

Our final analysis looked at whether major breaks in meaning across all situational types (situational “discontinuity”: changes in characters and spatial location, but no change in time) aligned with segmental changes in layouts. Again, we calculated the proportion of all discontinuous situational changes in each of the layout constituents out of the total number of layout constituent types. Situational discontinuity indeed varied based on layout constituent structures, F(1, 176) = 7.6, p = .001, but not significantly across continents, F (2, 131) = 2.9, p = .091. Overall, breaks between pages had the most discontinuity (all ts > 3.06, all ps < .006) as expected, while discontinuity across and within constituents did not differ from each other (p = 0.314), as shown in .

Figure 5. The log transformed proportion of constituents with discontinuous situational changes out of the total number of each constituent averaged per book. Each dot represents a comic analyzed, and error bars show the standard error.

Discussion

This study looked at the interaction between meaning (situational changes) and form (layout) in visual narratives. Our primary finding showed that meaningful changes occurred the most in shifts across pages and across constituents. Layout structure primarily aligned with shifts in spatial location while moving into a new page, but to a lesser extent in Asian comics. Finally, across-page transitions involved the most situational discontinuity (i.e., no progress in time with changes in characters and spatial location) with no cross-cultural variation. Altogether, these findings suggest that pages provide a segmental boundary for spatial meaning especially for some cultures and overall align with more situational discontinuity.

Before looking at the relations between layout and situational changes, we first looked at all shifts in meaning between panels. In line with prior findings (see Cohn, Citation2020a; Klomberg et al., Citation2022) this analysis confirmed that time shifted more than characters, while spatial location changed the least in our selected stories. We then investigated whether these changes differ based on layout constituents. When situational changes were constrained to the context of specific layout arrangements, time shifts reduced compared to all layout forms. Since layout constituents were used here as a proxy for representing the main aspects of layouts, they do not cover every possible panel arrangement. Within these transitions between parts of layouts, time changes were reduced to equal to or less than character changes. This finding implies that time progresses even more outside the identified layout constituents compared to other types of changes, in line with the notion that time changes are predominant throughout a visual narrative in pushing the story forward.

Related to layout constituents, situational changes mainly occurred while crossing between pages or between constituents (rows, columns) than moving within those constituents. As predicted, within-constituent transitions had the fewest situational changes, implying that rows or columns might help comic authors to maintain a segmentation of the current situation. On the other hand, shifts occurring across constituents were comparable to those across pages. This finding goes against the idea that meaning changes occur across a robust hierarchy of layout constituents. It also suggests that across-page and across-constituent transitions might be comparably effective in segmenting overall meaning, or less influential in maintaining a current situation, in line with the idea that crossing a constituent may result in a cognitive change besides the physical change (Zacks et al., Citation2007).

However, when a page was broken down into its constituents, this specifically influenced shifts in spatial location. Neither time nor characters differed based on layout constituents, but location shifted the most across pages. This implies there is no one-to-one relationship between time and space as argued by McCloud (Citation1993). If the strong view of “time = space” were the case, the largest spatial distance between panels, as in a new page, would reflect more time progression (see Cohn, Citation2010). Yet, we showed no such relationship here between longer breaks and time changes. This was only applicable for changes in space itself.

Secondly, and perhaps more noteworthy, this finding of shifts in spatial location occurring the most across pages also suggests that pages might be working as a segmental boundary for spatial meaning. Comics do not change scenes often, but when they do, it aligns with the start of a new page. This also means the prior scene ends at the end of the previous page, reflecting another part of the segmental boundary. Thus, we suggest that a page is used to segment and group spatial meaning, in line with other theorists proposing that authors use pages as a unit (Bateman et al., Citation2021; Eisner, Citation2008; Groensteen, Citation2007).

This notion of a page as a segmental unit was also supported by our analysis of situational discontinuity (i.e., no time change while characters and spatial location shift) in layout constituents. Shifts across pages again carried the most discontinuous changes, further supporting the idea that the page functions as a segmental unit (Eisner, Citation2008; Groensteen, Citation2007). No variation in discontinuity appeared in shifts across or within constituents. Thus, although pages and across-layout constituents were comparably effective in segmenting meaning, pages remained more influential in segmenting full discontinuity. Altogether, situational discontinuity occurs between page-level units overall, but particularly for segmenting changes in spatial locations.

This alignment between spatial meaning and its manifestation in spatial form might also have psychological implications for the comprehension of comics. Works on event cognition have argued that a new situational model might be created when crossing an event boundary. In the case of spatial cognition, a location shift prior to encountering an event boundary becomes less accessible because of the new situational model created and stored in memory (Radvansky et al., Citation2011). In that sense, placing situational boundaries at physical page boundaries might make it easier to segment the situational change in constructing a cognitive situation model (Cohn, Citation2020b; Loschky et al., Citation2020). Therefore, the shift to a new physical space in the given layout could help align with shifting or updating the location in readers’ situation models.

Future research can look more into this relationship between the physical and situational segmentation, and whether the effects on comprehension would indeed only be limited to spatial coherence at page breaks. Though we did not find temporal or character changes to be distinguishable between different layout constituents in our corpus analyses, it would still be interesting to examine whether differences in physical segmentation (across pages, and between versus within constituents) would affect the comprehension processes of situational changes. In addition, such work could also examine the effect of placing a shift in space at an unexpected location (e.g., within constituents) on comprehension.

However, these alignments between meaning and layout do not appear universal, as we also found cross-cultural variation. Across all comics, only Asian comics shifted between characters across panels more than time, while locations shifted the least as in other cultures, in line with prior findings of situational changes (Cohn, Citation2020a; Klomberg et al., Citation2022). Yet, at the same time, Asian comics maintained less of a preference for pages as a segmental unit. Similar reduction of spatial location changes was observed within constituents compared to crossing pages, but unlike other continents locations shifted differently only between the two extreme sides (maintaining rows/columns vs. crossing pages) of the constituent hierarchy. In other words, pages segmented spatial meaning more than rows or columns, but page breaks were not more effective than across-consti tuent transitions (like row breaks) to segment spatial meaning in Asian comics. Thus, we conclude spatial location changes were not that influential across pages in Asian comics as much as in comics from Europe or the United States. This implies fewer constraints on where scenes might change in Asian comics, and that they do not package meaning in the same way as comics from Europe or the United States.

A possible explanation for why Asian comics do not use layouts robustly as a segmental boundary is that their overall storytelling styles differ from those in European or American comics. As reflected by the greater amounts of character changes overall, Asian comics have been said to sponsor more inferencing of spatial environments throughout their storytelling (Cohn, Citation2013b). It is possible that the greater prevalence of constructing spatial situation models throughout a visual sequence would render physical changes as less salient or necessary. Alternatively, Asian comics might be using physical cues other than page boundaries to compliment meaning, such as leaving wider gaps between panels (gutter distance) for full scene changes, as suggested by additional corpus analysis (Cohn, Citation2023). This would be then in line with the idea of Natsume (Citation1997) that Japanese manga uses differences in size and shapes of panels to influence the flow of meaning, akin to prosody in speech (Holt & Teppei, Citation2021). Thus, Asian comics might be less sensitive to using pages as scene boundaries, but rather also use within-page cues such as the gutter distance.

Despite cross-cultural variation in situational changes, we observed no variation related to situational discontinuity in the identified layout constituents. Outside of layout structure, prior work found overall more discontinuity in Asian comics compared to European and North American ones (Klomberg et al., Citation2022). That might imply that even though Asian comics do not maintain continuity in general, this tendency is also not influenced by layout constituents. However, it is noteworthy to point out that similarity across cultures for global situational discontinuity in layouts could be related to the nature of our corpus as well. Several books have low rates of discontinuity on the whole (i.e., see the prevalence of zeros in ), and thus a larger corpus with more data points could test if that is indeed the case. Similarly, future work can also examine whether specific concurrence in situational changes (e.g., only time changes, or spatial changes but no time or character changes) have alignments with layout, rather than just each situational dimension.

Altogether, the spatial organization of panels by layouts does appear to provide segmental boundaries for meaning, as intuited by comics creators and scholars. While situational changes occurred the least when moving within rows or columns, shifts across pages carried the most discontinuous changes, particularly segmenting between spatial locations. Thus, our results suggest that pages serve as the primary segmental boundary for situational changes. Yet, these alignments between meaning and layout vary across cultures, implying further complexity to cues or constraints of segmenting meaning besides the spatial layout.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bateman, J. A., Veloso, F. O., & Lau, Y. L. (2021). On the track of visual style: A diachronic study of page composition in comics and its functional motivation. Visual Communication, 20(2), 209–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357219839101

- Bateman, J. A., & Wildfeuer, J. (2014). A multimodal discourse theory of visual narrative. Journal of Pragmatics, 74, 180–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2014.10.001

- Caldwell, J. (2012). Comic panel layout: A Peircean analysis. Studies in Comics, 2(2), 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1386/stic.2.2.317_1

- Cohn, N. (2010). The limits of time and transitions: Challenges to theories of sequential image comprehension. Studies in Comics, 1(1), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1386/stic.1.1.127/1

- Cohn, N. (2013a). Navigating comics: An empirical and theoretical approach to strategies of reading comic page layouts. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00186.

- Cohn, N. (2013b). The visual language of comics: Introduction to the structure and cognition of sequential images. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Cohn, N. (2020a). Who understands comics? Questioning the universality of visual language comprehension. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Cohn, N. (2020b). Your brain on comics: A cognitive model of visual narrative comprehension. Topics in Cognitive Science, 12(1), 352–386. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12421

- Cohn, N. (2023). The patterns of comics: Analyzing visual languages from Asia, Europe, and North America. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Cohn, N., & Campbell, H. (2015). Navigating comics II: Constraints on the Reading order of comic page layouts. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29(2), 193–199. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3086

- Cohn, N., Cardoso, B., Klomberg, B., & Hacımusaoğlu, I. (In Prep). The Visual Language Research Corpus (VLRC): An annotated corpus of comics from Asia, Europe, and the United States.

- Eisner, W. (2008). Comics and sequential art: Principles and practices from the legendary cartoonist. W.W. Norton.

- Gavaler, C., & Beavers, L. A. (2020). Clarifying closure. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, 11(2), 182–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/21504857.2018.1540441

- Gernsbacher, M. A. (1985). Surface information loss in comprehension. Cognitive Psychology, 17(3), 324–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(85)90012-X

- Groensteen, T. (2007). The system of comics. (B. Beaty, N. Nguyen, Trans.). University of Mississippi Press. (Original work published: 1998).

- Holt, J., & Teppei, F. (2021). The functions of panels (koma) in manga: An essay by Natsume Fusanosuke. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 21(2).

- Kintsch, W., & van Dijk, T. A.. (1978). Toward a model of text comprehension and production. Psychological Review, 85(5), 363–394. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.85.5.363.

- Klomberg, B., Hacımusaoğlu, I., & Cohn, N. (2022). Running through the who, where, and when: A cross-cultural analysis of situational changes in comics. Discourse Processes, 59(9), 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/0163853X.2022.2106402

- Loschky, L. C., Larson, A. M., Smith, T. J., & Magliano, J. P. (2020). The scene perception & event comprehension theory (SPECT) applied to visual narratives. Topics in Cognitive Science, 12(1), 311–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/tops.12455

- Magliano, J. P., Kurby, C. A., Ackerman, T., Garlitch, S. M., & Stewart, J. M. (2020). Lights, camera, action: The role of editing and framing on the processing of filmed events. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 32(5–6), 506–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/20445911.2020.1796685

- McCloud, S. (1993). Understanding comics: The invisible art. Kitchen Sink Press.

- Natsume, F. (1997). Manga wa naze omoshiroi no ka: Sono hyogen to nunpo (Why Is Manga So Interesting?: Its Grammar and Expression). NHK Raiburari.

- Pederson, K., & Cohn, N. (2016). The changing pages of comics: Page layouts across eight decades of American superhero comics. Studies in Comics, 7(1), 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1386/stic.7.1.7_1

- Peeters, B. (1998). Case, Planche, et Récit: Lire la Bande Dessinée. Casterman.

- Radvansky, G. A., Krawietz, S. A., & Tamplin, A. K. (2011). Walking through doorways causes forgetting: Further explorations. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 64(8), 1632–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2011.571267

- Radvansky, G. A., & Zacks, J. M. (2014). Event cognition. (pp. ix, 272). Oxford University Press.

- Tanaka, T., Shoji, K., Toyama, F., & Miyamichi, J. (2007). Layout analysis of tree-structured scene frames in comic images. Paper Presented at the International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Hyderabad.

- Wertheimer, M. (1923). Untersuchungen zur Lehre von der Gestalt. II. Psychologische Forschung, 4(1), 301–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00410640

- Zacks, J. M., Speer, N. K., Swallow, K. M., Braver, T. S., & Reynolds, J. R. (2007). Event perception: A mind-brain perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 133(2), 273–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.273

- Zwaan, R. A., Langston, M. C., & Graesser, A. C. (1995). The construction of situation models in narrative comprehension: An event-indexing model. Psychological Science, 6(5), 292–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00513.x

- Zwaan, R. A., & Radvansky, G. A.. (1998). Situation models in language comprehension and memory. Psychological Bulletin, 123(2), 162–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.123.2.162.