ABSTRACT

This contribution investigates the arrival of British developers on Dutch soil during the 1970s from a transnational perspective. Doing so will not only reveal how British expertise and financial strength led to a maturation of the Dutch property market, but will also shed a new light on the economic, cultural and political ties between two European trading partners. There is much academic and public debate today about the invasion of global cities by foreign property investors, yet empirical investigations of historical predecessors to the current situation are virtually non-existent. This contribution puts Britain’s business relationship and interactions with Europe and the Netherlands central. This will reveal why British developers became interested in European property in the first place, how they viewed the market and its players based on national characteristics and stereotypes, and why British involvement eventually became heavily contested on the local level. This will lead to a more comprehensive and multifaceted narrative of British involvement in overseas property affairs during a period of growing rapprochement between Britain and the EEC, and adds to our understanding of both Anglo-European relations and local sentiments towards international influences in a more general sense. The focus of the article lies on attitudes and mindsets, as these ultimately facilitated the transnational flows of capital and knowledge exchange.

Introduction

For a film about the workings of local democracy, the Dutch docudrama De Strijd om de Stad (‘The Battle over the City’, 1978) features a remarkable opening sequence. Accompanied by a sinister David Bowie tune, a panning shot of the British Houses of Parliament takes us to a glimmering office block, where a group of middle-aged men is eagerly listening to a Dutch real-estate broker. His slide presentation concerns a working-class area in central Amsterdam, supposedly ripe for British-funded luxury developments. The remainder of the film, first screened in 1978, narrates the neighbourhood’s struggle for affordable housing and the backroom politics through which the developers eventually achieve planning permission.Footnote1 More documentary than drama, the film is an accurate depiction of the post-war tensions over urban redevelopment. In particular during the early 1970s, Dutch newspapers and professional journals frequently ran background stories on how the Brits were ‘invading’ the country and had ‘thrown’ themselves at the Dutch property market at the expense of local residents (Trouw, 17 October 1970; Het Financieele Dagblad, 19 October 1970; Nieuwsblad van het Noorden, 27 October 1970; De Volkskrant, 4 December 1970). Between early 1971 and late 1972, the number of British developers operating on Dutch soil quadrupled (The Guardian, 7 September 1972; De Volkskrant, 5 October 1972). Their growing interest in European bricks and mortar, and the growing tensions in which this resulted, was picked up on the other side of the North Sea as well, where The Guardian spoke of the ‘dramatic impact’ of British finance and expertise on the continental property market (The Guardian, 25 February 1974).

Driving the property boom was a seemingly insatiable appetite for new construction, which was by no means unique to the Dutch context. The age of affluence, which roughly lasted from the late 1940s into the early 1970s, was one of unprecedented urban expansion and renewal in Western Europe, conducted under the auspices of the expanding welfare state.Footnote2 Urban centres considered to be out-dated or obsolete were redeveloped, while new planned settlements took shape on the fringes of cities and towns. Growing prosperity and the transition to a post-industrial economy coalesced with an unprecedented planning fervour. Central in the vocabulary of planners stood the notion of comprehensive redevelopment, which entailed the zoning of urban functions and the replacement of run-down central districts with modern apartment buildings, expressways, office blocks and shopping centres. Only after the Oil Crisis of 1973 and mounting criticism from neighbourhood action groups did the renewal machine slow down – much to the detriment of property developers.Footnote3

While private entrepreneurs have been professionally engaged in real-estate development since the advent of the Second Industrial Revolution, property developers only rose to prominence during the post-war era. Land being a scarce resource and accommodation a basic necessity meant that developers were in a strong position during this period of exponentially growing demand.Footnote4 Acting on their own initiative and risk, they played a decisive role in designing, financing and constructing the ‘brave new world’ of urban modernism, either by partnering with a city council or applying for planning permission.Footnote5 Most notable in the developer’s modus operandi is the assembling of different phases and actors in the construction process. Usually without knowing his future occupants, a developer would find a building site, arrange the finance for construction, conceptualize, and finally market the product.Footnote6 In the words of Marshall Berman, the property developer ‘can bring material, technical and spiritual resources together, and transform them into new structures of social life’.Footnote7 In his seminal book on the British property boom of the late 1950s and early 1960s, Oliver Marriott even compares the work of a developer to that of an impresario:

He is the catalyst, the man in the middle who creates nothing himself, maybe has a vague vision, and causes others to create things. His raw material is land, and his aim is to take land and improve it […] so that it becomes more useful to somebody else and thus more valuable to him.Footnote8

As the undertone in Marriott’s comparison suggests, developers have often been the target of slander and ridicule. Together with the architects they worked with, they have been stereotyped as the greedy arch-villains of urban planning. More balanced historical accounts of property developers and their conduct of business are scarce, except for a limited number of studies by scholars in the fields of real estate and financial geography. However, while the work of the former is often restricted to legal contexts and business strategies, the latter tend to assume that private sector involvement in urban development only became widespread during the 1980s.Footnote9 In addition to a number of (auto)biographical accounts, notable exceptions in the British context concern extensive monographs by Hedley Smyth and Peter Scott, who examine the historical development of British commercial property through a number of selected case studies and nationwide economic dynamics.Footnote10 More recently, architectural historians Amy Thomas and Ewan Harrison investigated the partnerships between infamous developers and commercial architects such as, respectively, Harry Hyams and Richard Seifert.Footnote11

Urban history approaches to the topic are fairly new as well. Recently, Alistair Kefford has proposed to examine the first post-war decades as a breeding ground for neoliberal urbanism, while Peter Shapely has drawn our attention to the public–private partnerships forged between elected officials and developers in post-war British cities and towns.Footnote12 In the American context, a recent monograph by Sara Stevens is the first major study to focus on the work of developers, although their overseas involvement in property markets is left out of consideration.Footnote13 In the Netherlands, Hans Buiter and Willem van der Boor have adopted a case study approach to examine, respectively, the history of one construction company in particular and the legacy of public–private partnerships in general.Footnote14 Thus, we are left with a scattered historiography of a worldwide phenomenon that has been only marginally discussed by Anglophone and Dutch historians.

This contribution investigates the arrival of British developers on Dutch soil from a transnational perspective. Doing so will not only reveal how British expertise and financial strength led to a maturation of the Dutch property market, but will also shed new light on the economic, cultural and political ties between two European trading partners. According to Pierre-Yves Saunier, transnational history leads historians to follow flows, watch ties and reconstruct formations and relations between, across and through nations. Through historicizing contacts between communities, polities and societies, an empirical answer can be given to what is, and when was, globalization.Footnote15 There is much academic and public debate today about the ‘invasion’ of global cities by foreign property investors, yet empirical investigations of historical predecessors to the current situation are virtually non-existent.Footnote16 This contribution argues that already during the 1970s British and Dutch property markets became heavily intertwined through the overseas development and financialization of real-estate projects, office buildings in particular. The focus lies on attitudes and mind-sets, as these ultimately facilitated the transnational flows of capital and knowledge exchange.Footnote17

To examine the role of British property developers operating during the post-war period, this research builds on insights from the field of critical urban theory. Key in this field is the idea that urban questions, state power and the overall economic structures of advanced capitalist societies are intrinsically linked.Footnote18 During the post-war era, urbanization has supplanted industrialization as the driving force of capitalism, or, as Andy Merrifield explains:

The capitalist epoch reigns because it now orchestrates and manufactures a very special commodity, an abundant source of surplus value as well as massive means of production, a launch pad as well as a rocket in a stratospheric global market: urban space itself.Footnote19

According to David Harvey, to understand how cities are financed and constructed, scholars need to examine how local governments facilitated and coordinated the involvement of private entrepreneurs.Footnote20 As one of the few Dutch scholars to underpin Harvey’s theories with an empirical base, Ralph Ploeger has observed how each phase of Amsterdam’s capitalist development builds on a distinctive form of territorial organization, and how mobile capital is temporally fixed to a certain geographical place by way of long-term investments, in this case office buildings.Footnote21 Following this observation, the post-war agenda of urban redevelopment can be seen as the state guarantee of long-term, large-scale investments in the built environment, from which developers stood to profit.Footnote22 Often in close cooperation with elected officials, these entrepreneurs transformed cities into growth machines internationally competing with one another to attract ever more jobs, investments and prestige.Footnote23

To underpin these theories with a firm empirical base, the article makes use of the foremost British property journals and newspapers, and – to a lesser extent – their Dutch counterparts. The contributors and readers of the Estates Times, Investors Chronicle, Property Gazette and Financial Times were usually active in the field of property development themselves or were at least knowledgeable about its workings. Thus, these printed publications give us a unique insight into why certain investment decisions were made, for which reasons continental Europe came into sight as an investment destination, and how the sector saw itself in relation to the outside world. The focus on the British perspective is justified by the sheer number of British journals on the topic, and the agility of the British property sector in comparison to its European equivalents. Indeed, the publications under examination in this article were well read outside of the UK as well, whereas the Netherlands boosted one professional journal (Vastgoedmarkt) which was only launched in 1974. More in general, company archives are notoriously difficult to access due to poor recordkeeping, business volatility and privacy issues, forcing historians to consult alternative bodies of primary sources.

Not coincidentally, British activity in Europe accelerated as the country was gearing up for its entry into the European Common Market. Expecting a freer flow of capital and goods, developers looked eagerly towards the opportunities awaiting them on the continent. As this article will demonstrate, contrary to the mixed feelings with which British business leaders look at the European project today (The Guardian, 1 September 2019), the mood in the early 1970s was mostly buoyant and self-confident. Interestingly, in their longing for profit maximization abroad, the property sector expressed the same sentiments as the opponents of European integration.Footnote24 British developers still thought of their country as a global rather than a European power, were suspicious about continental customs in their field of business, and remained wedded to their strong bilateral ties with the United States. In their view, the conservative and stagnant European property market would be injected with much-needed British capital and entrepreneurship. Huge profits were expected because of the growing demand for office space in European capitals, most notably Amsterdam. The investment yields on Amsterdam offices, which were several percentage points higher than London offices, drew nearly a hundred British firms to the Dutch property market during the early 1970s.

However, the appetite for continental property came at an unfortunate moment. Soon after the British had entered the Dutch market, the property crash of 1974 and an increasingly hostile investment climate compromised their operations, forcing many newcomers to retreat within the timespan of only a few years.Footnote25 With the political focus on equal say and social activism of the early 1970s, foreign developers came to be seen as undemocratic bodies with illegitimated power over people’s living environments. It will be demonstrated that the British presence in the Dutch property market needs to be seen against the background of a growing rapprochement between Britain and Europe, which had a direct influence on both the conduct of business and the everyday life of Amsterdam’s residents. Thus, a more comprehensive and multifaceted narrative of British involvement in overseas property affairs emerges, adding to our understanding of both Anglo-European relations and local sentiments towards international influences in a more general sense. In doing so, this article heeds recent calls by economic historians to move our focus away from political and diplomatic history, and instead address the intrinsic links between European integration and capitalism.Footnote26 This in turn will provide more empirical evidence for the internationalization of capital flows and the rise of neoliberalism during the ‘long 1970s’, for which cities were an important testing ground.Footnote27 In relation to this last point, this contribution argues that cities need a firmer embedding in studies of international economic activity.Footnote28

I.

From the late 1940s well into the 1970s, Western Europe experienced unprecedented growth in affluence and prosperity. Inspired by Keynesian thinking, there was a widespread consensus amongst political elites that the state should lubricate the wheels of the economy by regulating supply and demand while restricting the most volatile dictates of the market, and that improvements in the living conditions of the masses could be obtained by social provisions.Footnote29 The post-war economic boom was achieved by what Mark Mazower has labelled a ‘mutually acceptable and beneficial symbiosis’ between public and private sectors, which agreed on the advantages of directive economic measures and counter-cyclical management.Footnote30 Britain was no exception in the expansion of the welfare state and growing levels of prosperity during the economic miracle of the 1950s and 1960s. Economic growth averaged 2–3% of GDP per annum, with peaks of up to 7% towards the end of the period.Footnote31 Average earnings were on the rise, society enjoyed near full employment and ever more people had access to leisure and consumer durables.Footnote32 In particular during the late 1950s, there was an unshakeable optimism about continuing economic growth and the inevitable march of affluence.Footnote33

As a consequence of the economic upswing there was a rapidly growing demand for new infrastructures and buildings, which quickly manifested itself in an increasingly dynamic real-estate market. The 1950s and early 1960s saw an increase in lending by building societies, more private house-building, and rising prices for both new developments and second-hand homes.Footnote34 Because affluent societies require more services, the composition of Britain’s workforce was gradually shifting towards office and administrative support occupations.Footnote35 Whereas in 1951 only 33% of final expenditure by households and government was on services, in 1975 this had risen to 55%.Footnote36 By the third quarter of the twentieth century, the service sector had become the dominant employer of Britain’s workforce. The growing number of jobs in finance and business services and those professions linked to the expanding welfare state, most notably public administration, education, health and social services, accelerated demand for office space and triggered a massive building spree, in which property developers played a crucial role. As observed by Marriott, the basic economics of British property development were rather straightforward: ‘they were men who happened to be in the right business at the right time and, given the profit margins in that business, could hardly fail to make money … . The only equipment he needs is a telephone.’Footnote37 Scott reaffirms this observation by stating that developers were primarily depending on dealing skills, in addition to an understanding of how locational factors determined site values.Footnote38 While the majority of firms consisted of just one individual or a limited number of partners, others had dozens of employees on their payrolls.

Credit for their developments was usually established by banks, but from the mid-1950s onwards, by institutional investors as well. To match long-term commitments to long-term assets, pension funds and insurance companies became particularly interested in property and equity partnerships with developers.Footnote39 In particular the increasing coverage rate of private pension funds in Britain, going up from less than 15% before the Second World War to 50% in 1965,Footnote40 led to an accumulation of financial assets and thus a growing incentive to invest in bricks and mortar. These institutional investors would buy property directly off the market as ready-made investments, lent money to developers as mortgages against property, or participate in sale-and-leaseback arrangements.Footnote41 Because property enjoyed a relatively steady market, it could be more realistically priced than other assets. Property portfolios were an attractive investment as they acted as an inflation hedge, and provided investors with secure and rising yields without much further activity on their part. From only just outpacing inflation between 1965 and 1967, the return on property grew to an annual average of almost 11% ahead of inflation between 1968 and 1970 and a staggering 14.2% per annum from 1971 to 1973.Footnote42

Investments in new office buildings were primarily directed towards city centres. Historically the service sector had always concentred in central districts, where transport and communication facilities were optimal and managers had easy access to other professionals. This became even more true during the post-war period, when developers came to understand central urban areas as the hubs of a new economy dominated by business, finance and consumerism.Footnote43 This resulted in the loss of many Victorian and Edwardian buildings, which had to make way for a growing number of cars, increasing amounts of office space and more retail and shopping venues.Footnote44 In particular, London’s City became a focal point for property development, where a backlog in office construction and the preference of companies for a prestigious address spurred demand.Footnote45 From the aftermath of the Second World War onwards, the lifting of planning restrictions, expanding institutional resources, and decreasing shortages of building materials paved the roads to riches for many property men, who began to search for development opportunities outside of the City as well.Footnote46

While the transformation of British city centres often resulted in the loss of housing and stark architectural contrasts with historical surroundings, the office boom was initially met by much apathy. Only during the 1970s did hostile reactions against urban redevelopment become widespread and well organized.Footnote47 Whereas the opposition in Western European cities was led by neighbourhood action groups, in the British context the lead was taken by the heritage movement and the architectural profession.Footnote48 Property developers were their main villains. Their economical and frugal approach to design and abuse of judicial loopholes, through which developers maximized the floor area permissible on a particular site, led critics to accuse them of putting profits ahead of aesthetics.Footnote49 Obviously the property man was not the only one to blame. Looking back on the concrete results of the office boom in 1971, Alex Gordon, president of the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA), stated that developers often ‘erred’ by their choice of designers, thus reproaching the architectural profession for the questionable quality of the property rush (Estates Times, 28 October 1971).

The building boom would have been impossible without the active involvement of local and national governments. On the one hand, the expansion of the British state lessened local autonomy and reduced the influence of civic elites. At the same time, capital was no longer predominantly locally but nationally organized, which is exemplified by the rise of institutional property investors. Thus, local councillors often became more dependent on the resources of property developers.Footnote50 On the other hand, government planners tried to get a stronger grip on the geographical spread of investments. To counter commercial overconcentration and traffic congestion, in 1964 the incoming Labour government of Harold Wilson imposed a ban on speculative office development in the Midlands and the South of England, followed by a heavier taxation of property investments. A period of stronger interventionism had arrived.Footnote51 The heavy involvement of the British state in economic and planning affairs even led David Edgerton to label its policies during the 1960s as ‘national capitalism’.Footnote52 While dispersal and taxes were imposed to slow down the office boom, they ultimately resulted in pent-up demand and higher prices (Investors Chronicle, 13 March 1970). It soon transpired that market conditions changed far more rapidly than planners could change their rules and attitudes (Investors Chronicle, 26 September 1971). After coming to power in 1970, the Conservative government of Edward Heath lifted planning restrictions again and simplified bank lending to property developers. Interventionist policies in the economy were replaced with market solutions again.Footnote53 The inducements came on top of the increased capital inflow from insurance companies and pension funds, as well as a perceived shortage of top-class property.

These conditions paved the way for a new boom. There was a significant rise in real estate prices, in particular from 1971 onwards, which not only led to increasing office development, but also the first signs of gentrification in London’s inner boroughs.Footnote54 Contrary to the bull market of 1955–64, when property shares were based on actual profits, the 1970–73 boom was mainly fuelled by expectations. After the first stirrings of the bull market were felt in 1967, the value of British property shares quintupled. The massive inflow of institutional funds meant that business could only be done on the basis of extremely optimistic assumptions.Footnote55 Property commentators soon acknowledged that what goes up, must eventually come down. In 1970, the Investors Chronicle was still confident that bricks and mortar would remain an attractive investment in the new decade (Investors Chronicle, 16 January 1970). Only two years later, the same journal labelled 1971 as a year of ‘fever and madness’, in which the property market went beyond reason and prices were no longer in proportion to expected benefits (Investors Chronicle, 7 April 1972). As it transpired that developers could not ascertain the real value of their assets, investment conditions rapidly went from favourable to insecure (Investors Chronicle, 30 January 1973; Investors Chronicle, 6 April 1973).

This time public awareness of the property boom and its negative consequences was much greater. Comprehensive urban redevelopment, which underpinned many of the inner-city office schemes, began succumbing to conservation as the prevalent planning paradigm, with a new value placed on the human scale and local identity.Footnote56 The politicization of the public sphere during the 1970s was expressed in more zealous reporting and investigative journalism, as well as the polarization of local and national politics.Footnote57 Given its accumulation of wealth based on speculative development, the property industry was a popular scapegoat amongst inquisitive journalists and left-wing commentators. During a 1973 speech, trade union leader Clive Jenkins even called property developers ‘the social evil of our times’ (Estates Times, 6 December 1973). Such allegations were substantiated by a growing number of critical reports on the work of property developers, most notably The Recurrent Crisis of London.Footnote58 The mounting criticism led some developers to defend their work as improving the British quality of life, while others called for a facelift of their troubled public image (Estates Times, 6 December 1973, 18 April 1974, 20 June 1974, 29 May 1975, 7 November 1975). Still others admitted their past mistakes. Discussing the renewal of city centres in 1972, the chairman of property development company Capital and Counties, Richard Thompson, called for reconciliation:

The developer must accept wholeheartedly the social responsibility that falls on those who have the power and the resources to reshape, perhaps for a century to come, the surrounds in which the rest of us will live, work and play. It means accepting that conservationists are not cranks and developers are not vandals, and trying a little harder to achieve a working comprise between the two. (Investors Chronicle, 24 November 1972)

It was against this background of an imminent property crash and growing criticism at home that British developers began ogling continental Europe.

II.

While the early 1970s was a period of growing rapprochement between Britain and the European Economic Community (EEC), earlier encounters were rather problematic. During the 1950s Britain had favoured a strong partnership with the United States, which was still its most important trading partner. Economically the country was still very much oriented towards the Commonwealth, whereas the fastest growth in world trade was increasingly occurring between industrialized nations.Footnote59 By the end of the decade British economists and civil servants grew worried about the nation’s structural economic problems, which they partially blamed on its insular position in world politics and trade relations.Footnote60 The official realization that Britain was economically lagging behind the six founding members of the EEC led Britain to apply for membership in 1961, albeit on their own terms. This insistence on special treatment and its warm ties with the United States was watched with suspicion by the French in particular, which used their veto power to delay British membership.Footnote61 When entry into the Community was finally formalized on 1 January 1973, the country had missed out on many of the economic benefits enjoyed by the Inner Six.Footnote62 However, if the mood amongst the general public might have been one of wary acceptance, for business elites and the Conservative Heath government, the move towards Europe was a move towards free trade and growing prosperity.Footnote63 The European market would open up to British exporters, while at home labour unions and management would be subjected to healthy competition from the continent as well as EEC aid to economically backward regions.Footnote64

In the years leading up to membership, British business journals burst with enthusiasm over the European project. The property sector was particularly impassioned about the prospects. Expecting the removal of investment barriers and a 40% increase of exports, the Investors Chronicle made an emotional plea to join the continental trading bloc in 1971: ‘If Britain joins the Common Market, hope will have triumphed over sober expectation. Do or decline in a spacious and stimulating environment is the exhortation. Fade away in insular isolation the implied alternative’ (Investors Chronicle, 9 July 1971). This rhetoric was widespread amongst pro-marketeers, who depicted their opponents as isolationists out of touch with global realities.Footnote65 Eventually, they were proven right by positive export figures and an increasingly favourable public opinion.Footnote66 The budding relationship with Europe was particularly welcomed by the British property industry, as its home market was becoming saturated. Anticipating membership, the Estates Times was pleased to see Britain ‘looking beyond her own shores again’ and recovering from a ‘depressing period’ of introspection (Estates Times, 2 July 1970). In a call to break down the fences, Colin Hunt of Taylor Woodrow Property expressed a view commonly held amongst his colleagues: ‘With modern communication systems, the growth of the multinational company and internationalisation of funding operations, the world is shrinking and inevitably an entrepreneurial country like Britain looks overseas for expansion’ (Estates Times, 22 July 1971). Given such observations, it should come as no surprise that property developers were active supporters of the pro-Europe campaigns led by the European League of Economic Cooperation (ELEC) and similar organizations.Footnote67

Notwithstanding their support for the EEC, the property men made no secret of their superior feelings towards their European colleagues. In 1972 the Investors Chronicle stated rather immodestly that ‘in sheer versatility and entrepreneurial flair, the British are perhaps unmatched elsewhere in the world’ (Investors Chronicle, 19 May 1972). There was a general belief that British development expertise was unsurpassed, or as chairman of Reamhurst Properties Julian Markham told The Guardian: ‘There are no people in the world better able to take advantage of out-to-date conditions and land scarcity in the face of heavy demand than the British developer, weaned on the redevelopment of London and major provincial cities’ (The Guardian, 25 February 1974). Although slightly overstated, during the 1960s the British property industry had indeed been further institutionalized and professionalized, which advanced its march into Europe. This was also due to the much larger share of the services sector in the British economy than in any other of the European economies, which had provided British businesses with a vast amount of experience in office building and financing.Footnote68 The property media agreed that during the 1960s the flamboyancy and instinct of the 1950s had made way for cold-bloodedness and calculation, in particular with regards to the scouting of untapped markets (Estates Times, 7 March 1974; Financial Times, 23 March 1972; Financial Times, 4 April 1973). According to senior property advisor Jack Collis, on the continent the British had to overcome a lack of institutional long-term finance and weave a path through the myriad of local exchange controls, taxation provisions and building regulations (Estates Times, 4 November 1971).

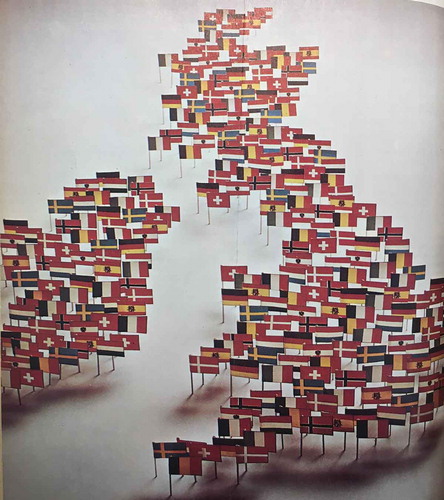

For fear of missing out, throughout 1972 and 1973 dozens of British firms jumped on the property bandwagon. The most popular destinations for jet-hopping developers were Brussels and Paris, where an expanding EEC bureaucracy and a growing number of international head offices spurred demand. By 1973 as much as 80% of modern office blocks in Brussels were developed by British companies (Investors Chronicle, 6 April 1973). They were not always welcomed with open arms. The Estates Times discerned a growing resentment and even outright anger over the British recklessness in Europe (Estates Times, 20 July 1972, 23 November 1972, 4 January 1973). The increasingly hectic and overcrowded market led property advisers Jones Lang Wootton to issue a dire warning: ‘It is unfortunate that, partly due to a sudden lack of reticence coupled to remarkable success, we are in danger of causing an unfavourable reaction to what many regard as an invasion’ (Financial Times, 3 January 1973). A few months later, again Julian Markham even summoned his colleagues to hit the brakes: ‘Europe is now fully aware of the British role and while countries encourage overseas investment, the scale and publicity of British investment has hardened attitudes’ (Estates Times, 12 July 1973). This became painfully clear during a conference organized by the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) in 1973, when several attendees lashed out against British developers. Perhaps the most scathing attack came from one of their fellow countrymen. While Britain had long since abandoned its imperial mission, Charles Strachey, British Conservative Member of the European Parliament, observed a persistent imperial attitude towards foreign territories: ‘The British are behaving as if they had just rediscovered India. They like our aims but not our manner’ (Estates Times, 19 July 1973).

During the early 1970s, the continent’s less active market, the scarcity of skilled property valuers, and a growing demand for better and more prestigious office accommodation encouraged British developers to cross the Channel. British business circles were quick to foresee the opportunities of European unification.Footnote69 This was not only the case in the field of property, as might be exemplified by the simultaneous rise of the Eurobond market, which bankers actively encouraged to advance political integration, and the unliteral liberalization of the initially tight restrictions on capital movement within Europe.Footnote70 Seen against this background, the increasing British activity on the continent was part of a much wider globalization of capital flows, which shaped an increasingly non-territorial domain for economic activity.Footnote71 Indeed, the internationalization of British property capital and expertise was just one example of a strategy of geographical expansion pursued by firms during the 1970s to confront declining profitability.Footnote72 As this section has demonstrated, British imperial attitudes clearly resurfaced in the conduct of business abroad.Footnote73 According to Brian Harrison, Britain’s entry into the EEC called into existence a new sphere of influence to ‘redress the waning of the old’,Footnote74 which can be seen in the almost missionary zeal for development and how the press described the property rush as a scramble for Europe. As the next section will demonstrate, national identities and cultural aspects played an important role in the property relations between Britain and the Netherlands as well.Footnote75

III.

Similar to Britain, during the post-war period the Netherlands was characterized by a mixed economy. Whereas the Dutch Labour Party and factions within the Christian-Democratic parties wished for more state involvement, the conservative liberals were much more on the side of the country’s commercial elites. The system of coalition governments however placed social democracy firmly in the saddle and created a strong consensus over the merits of state planning.Footnote76 Still, in property development free enterprise was seen as essential in providing the country with the buildings it needed to flourish. By examining the development of the British and Dutch economies in tandem, three interrelated reasons can be found for the British interest in Dutch property. Firstly, during the post-war period the Dutch economic centre of gravity shifted from manufacturing to services. From 1960 onwards, the number of Dutch blue-collar workers was in relative decline, and dwindled from 1965 onwards in absolute numbers as well.Footnote77 By contrast, office employment grew by a spectacular 31.5% between 1950 and 1965. Within the service sector, the government accounted for 32% of employment growth while banking and insurance provided 42% of the newly created jobs.Footnote78 By the end of the 1960s, more than half of Dutch GDP was earned by the tertiary sector, making the Netherlands one of the most advanced service economies in Western Europe.Footnote79 This post-industrial revolution resulted in a rapidly increasing demand for office space, especially in the central urban areas of the densely populated Randstad. Further driving up demand for space was the lack of purposely designed office buildings.

Secondly, the service economy proliferated at a time when the Dutch property industry was still in its infancy. Until the Second World War, commercial real estate in the Netherlands was largely developed by end users, who arranged their own financing, design and contractors.Footnote80 This changed during the 1960s, when an increasing number of businesses and government agencies shifted from owning to renting their offices to free up financial reserves and allow for a more flexible management of human resources, which spurred demand.Footnote81 Instead of retaining buildings as assets to produce cash flow, which was common in the British context, Dutch developers would normally sell a building upon completion to investors or end users. Those who acquired a property portfolio would usually draw up a 10-year lease for their tenants with a complete review at the end of a five-year period, combined with a yearly increase in rent related to the cost of living index. Finance was provided by private equity as well as pension funds and insurance companies, which during the 1960s were enticed by the liberalization of government restrictions on real-estate investments and the price control of building plots.Footnote82 Thus, while the market was certainly expanding and becoming more volatile, the British saw room for improvement.Footnote83 At the peak of the property rush in 1973, British firms had established more partnerships in the Netherlands than anywhere else, and had acquired nearly a quarter of all available office space in the country (Estates Times, 18 October 1973; Investors Chronicle, 6 April 1973).

Thirdly, Anglo-Dutch commercial relations were already well established as the rush took off, which facilitated the forging of business partnerships. Between 1965 and 1970, bilateral trade had grown at an annual rate of 10% to 15%, and the Dutch had received nearly a quarter of total British investment in EEC countries (Estates Times, 13 April 1972; Estates Times, 28 September 1972). Not surprisingly, Dutch officials were amongst the most ardent supporters of British EEC membership. The promotion of commerce and free trade had been at the core of British and Dutch relations long before European unification, as exemplified by Anglo-Dutch multinationals such as Shell and Unilever. As observed by Nigel Ashton and Duco Hellema, the countries shared ‘the businessman’s perception that profits could better be made in times of international order and stability rather than change and conflict’.Footnote84 In keeping the old but welcoming the new, the nation of merchants maintained similar business ethics as the British, said the Estates Times in 1973 (Estates Times, 18 October 1973). The Dutch proficiency in English and cultural similarities greased the wheels of business, or as a correspondent of the same newspaper noted: ‘The Netherlands, with their traditions of royal family, colonial empire, maritime trading and few natural resources understand the English in a way that is unique on the continent’ (Estates Times, 28 September 1972). Indeed, besides the growing demand for office space and an underdeveloped property industry, which were common to all European markets, a shared history provided fertile soil for doing business.Footnote85

While the affinities between the two nations certainly went deeper than economic self-interest, there were differences too. Planning regulations in the Netherlands were stricter, speculation was much more frowned upon, and it was more difficult to find long-term finance (Financial Times, 23 March 1972; Financial Times, 25 May 1972). This more conservative approach to property only bolstered British attitudes, or as one boisterous developer told the Financial Times: ‘They think the same way as we do – what they lack are good teachers’ (Financial Times, 15 October 1970). A correspondent of the same newspaper did little to overcome such stereotypes by describing the Netherlands as ‘stolid, likable but rather unexciting. [It] is a bit provincial, a country where seriousness and honesty and respect for the law represent the virtuous marks of its long Calvinist tradition’ (Financial Times, 23 October 1973). Not surprisingly, such attitudes offended the Dutch, or as the CEO of a leading construction company reflected on the British invasion: ‘We can see what Europe has to offer the British chartered surveyor, but what has the British chartered surveyor got to offer his European clients?’ (Estates Times, 19 July 1973).

Such observations not only point to growing hostilities, but also to a distinct bluntness in the Dutch conduct of business, on which the Estates Times commented: ‘The one really surprising thing about business methods is the complete lack of secrecy – everybody, allies, and competitors alike, work with refreshing candour’ (Estates Times, 18 October 1973). While the perceived naivety of the Dutch was something to be exploited, their dirigisme in planning matters was to be feared. When the centre-right governments that had governed the country during the 1950s and 1960s were succeeded by a more progressive administration in 1973, developers expected heavier taxation and the enforced dispersal of their investments (Investors Chronicle, 12 July 1974). However, it soon turned out that Dutch socialism was much milder than the British version.

By identifying the economic forces driving the property boom in the Netherlands, this section has demonstrated how the Dutch investment climate was largely favourable to British developers. It has also revealed some of the similarities in the organization of the countries’ mixed economies, most notably the reliance of local governments on private enterprise. As Peter Shapely has suggested, the relationship between public and private actors in the field of property development was rather unequal: ‘Faced with the promise of new investment […] it is little wonder that local councillors agreed to numerous schemes, many of which have since been heavily criticized.’Footnote86 In the face of a looming economic crisis, Dutch Labour councillors were just as keen as their British counterparts to co-operate with property developers for the sake of job growth and economic expansion. Thus, urban redevelopment was a pre-eminent social-democratic project, planned by local governments and executed by (inter)national market players. To investigate their interplay the next section zooms in on Amsterdam – the country’s commercial and financial hub, and therefore the primary destination of British investments during the 1970s.

IV.

A common complaint of British developers operating on Dutch soil was the complexity of the local planning process. On the bureaucratic level, their planning applications were subject to approval by state, provincial and municipal entities. While the central government aimed to regulate the flow of construction work throughout the country, local authorities asked developers to abide by technical requirements and land-use plans.Footnote87 During the post-war period, the land on which properties were built usually remained in the hands of the municipality, which charged a ground rent determined by the future location and value of a particular building.Footnote88 Added to the chicanery of preservationist lobbies and neighbourhood action groups, these formalities meant that obtaining consent to develop could take several years. On the political level, planning decisions were made by a municipal executive consisting of five to seven aldermen, one of whom presided over the local planning department. The executive was monitored by 45 city councillors, who were recruited by local political parties and elected during quadrennial elections.Footnote89 Almost without exception, all through the 1960s and 1970s the aldermen of the larger cities were members of the Dutch Labour Party.Footnote90 Indeed, during most of the post-war period, the Left dominated Dutch local politics.Footnote91

This was also the case in Amsterdam, which became the focal point of British investments in the early 1970s. Between 1969 and 1974, the number of British planning applications went from zero to 40, while it was estimated that nearly 100 British firms were engaged in the buying and selling of properties. The preference for Amsterdam was motivated by the city’s reputation as Europe’s third financial capital – after London and Paris (Financial Times, 23 March 1972). In addition, there was tremendous growth potential. Whereas investment yields on London offices were between 4.5% and 5% in 1972, Amsterdam offices brought in average yields of 7.5% to 8.5% (Financial Times, 23 November 1972). Distance played an equally important role. As the Estates Times noted, it was easier for a London-based developer to commute to Schiphol airport than to the North of England (Estates Times, 4 January 1973). He would probably feel more at home in Amsterdam anyway, or, as the same newspaper depicted the local street scene: ‘New cars, traffic jams, free-spending tourists, jampacked restaurants, crowded shops and prosperous looking businessmen’ (Estates Times, 28 September 1972). The arrival of the British did not go unnoticed: Town and City Properties, Bovis, Galliford, Hammerson and Reamhurst Properties frequently appeared on the financial pages of local and national newspapers (De Telegraaf, 5 October 1972; NRC Handelsblad, 10 January 1973). Thanks to their arrangements with capital-hungry builders, they quickly gained a foothold in the Amsterdam market. Knowledge about the local real estate market was gathered through contacting experienced real estate agents and the setting up of branch offices.

The British interest was not a one-sided love affair. In particular the planning department encouraged British involvement in expanding the local service sector. Ton de Gier, chief urban planner between 1966 and 1981, was pragmatic when it came to Amsterdam’s economic future: ‘The organisation of social life is led by private enterprise. Growth should not be confined, or else you will drain the city’ (Algemeen Handelsblad, 28 September 1968). De Gier’s colleague Hans Davidson made similar observations:

The city has to live, which means the service sector should be allowed to expand. Whether you like it or not, in our time this translates into rational architecture and the need to make sacrifices. A pity for historic cityscapes, but alas inevitable.Footnote92

Initially the planners were backed by their political superiors in the municipal executive, albeit with less of a laissez-faire attitude. Whereas his predecessors Joop den Uyl and Roel de Wit were largely in favour of urban redevelopment, Han Lammers, who served as planning alderman from 1970 to 1975, took a more ambivalent stance. A few years after his appointment, the Labour politician flew to London to meet the most prolific British developers in the Amsterdam market, whom he summoned to build flats instead of hotels and offices (Het Parool, 11 January 1973). The British were most certainly welcome but had to abide by his rules, or as Lammers told the Financial Times in 1973: ‘Basically, the city’s natural beauty and character must be preserved and we cannot tolerate any demolishment of housing, of which there is a big enough shortage already’ (Financial Times, 12 March 1973). Heeding these calls and sensing a new market, British developers pioneered the refurbishing of canal warehouses into swanky new apartments (De Tijd, 6 June 1973).

Despite such encouragements, most British developers remained primarily interested in office development. One of the most poignant symbols of the British property rush became the gargantuan Rivierstaete complex southeast of the city centre, co-designed by Basil Spence and built between 1967 and 1973 as the result of a joint venture between Hammerson and the Bank Onroerende Zaken (BOZ). By cooperating with a Dutch firm, Hammerson gained access to local planning knowledge and finance, giving it a significant advantage over its competitors (Financial Times, 15 May 1973). A similar joint venture was set up between life insurer Equity & Law and British developer Grand Vista Properties – an alliance that was funded by life assurance policies instead of financial institutions. Under the leadership of the 27-year-old Mike Slade, in 1974 Grand Vista acquired building plots in the Nieuwmarkt area to the east of the city centre, which were to be cleared for the construction of an urban expressway and the eastern axis of the city’s metro network. The Grand Vista scheme was eventually shelved due to protests from the budding heritage and squatting movements, which were supported by an increasingly critical architecture and planning press.Footnote93 Fearing a foreign takeover and oversupply of the local office market, in 1974 one journal even dedicated a special issue to the ‘British disease’. To scrutinize foreign involvement in their hometown, the contributors visited property conferences abroad and contacted London’s squatting movement, frequented the land registry, and compiled detailed maps and graphs of British operations in Amsterdam.Footnote94

While the victory over Grand Vista and similar office schemes has often been ascribed to an increasingly hostile planning climate,Footnote95 structural developments played a far bigger role. From 1973 onwards, it transpired that supply was far greater than demand in the Netherlands. Throughout the year the Financial Times noticed a worrying slowdown in Amsterdam’s office uptake, while schemes proposed earlier in the decade were not even on the market. Many British developers were already leaving the Netherlands again (Financial Times, 16 October 1974). Soon after the British entry into the EEC, stagflation and a worsening oil crisis put an end to the relative stability and rosy prospects of the golden years.Footnote96 The economic recession of 1973–75 forced many British developers to curtail their overseas operations. Obviously, the risk takers were hit the hardest, or as the Property Gazette put it: ‘Many of the pioneers, as pioneers do, failed and their bleached financial bones marked the pitfalls for those who followed’ (Property Gazette, 20 September 1973). The creation of the EEC and internationalization of property finance had caused a widening of markets, but made British entrepreneurs more vulnerable to global slumps as well. In addition to the economic downturn, during the 1970s the electronic revolution and automatization of clerical work further threatened the profitability of the Dutch office market (Elseviers Weekblad, 29 July 1978; De Groene Amsterdammer, 9 August 1978). Consequentially British survivors of the property onslaught moved their capital into the hotel business, thus contributing to Amsterdam’s more recent transformation into a popular tourist destination (Estates Times, 28 September 1972).

Conclusion

This contribution has examined why British developers became interested in European property in the first place, how they viewed national markets and their players, and why British involvement eventually became contested on the local level. After the first dust of the property rush had settled in 1975, the Estates Times looked back on the British involvement in Dutch property affairs as the cause of much resentment, or as well-known real-estate broker Cor van Zadelhoff put it: ‘They really must have thought we were idiots. We do have some quite intelligent men in the Netherlands. Did the British really think that if there was money to be made out of some of these schemes we would have let them go to outsiders?’ (Estates Times, 5 December 1975) While it was rhetorically framed, five years earlier the question might have been answered in the positive. Between 1970 and 1975, British developers propelled the European property market with financial strength and expertise, or at least made the Europeans more aware of property’s trading value. Their preference for investing in the Netherlands was both economically and culturally motivated: the saturation of their home market drove them to try their luck abroad, where they found rapidly growing demand in a relatively underdeveloped and friendly market. Despite the insensibilities with which British property men tried to conquer the continent, the Dutch initially welcomed their financial clout. The Netherlands had always been one of Britain’s strongest trading partners, which obviously enhanced the views developers and officials on both sides of the North Sea held of each other.

By employing a transnational approach, British developers have been unveiled as spiders in the web of national and local property markets, and agents in the transfer of international financial flows and expert knowledge. So far, historians have examined European integration mainly from the perspective of nation-states and international diplomacy. This contribution has demonstrated how closer scrutiny of developments on the urban level – as documented by such hitherto under-examined primary sources as the property media, local policy documents, newspapers and publications by neighbourhood action groups – can provide us with an alternative locus of historical interest.Footnote97 This article’s approach has not only demonstrated how the internationalization and liberalization of property markets has a much longer history than has been assumed so far, but also provides geographers interested in the urbanization of capital and the financialization of property assets with more empirical historical evidence.Footnote98 In addition, grander narratives of post-war European history, in which neoliberalism and globalization only began affecting policy-making from the late 1970s onwards,Footnote99 are complemented. Even at the zenith of the social-democratic welfare state, local governments very much depended on the market to get urban redevelopment of the ground.

Thus, we should be careful to draw a clean line between the golden age of state involvement in urban affairs from the end of the Second World War to the economic crises of the 1970s and the neoliberal policies of the 1980s. This contribution has demonstrated that historical watershed moments such as British entry into the EEC and the oil crisis that followed were preceded by growing international business ties. Still, to understand the investment decisions of British developers, one cannot merely focus on factors of supply and demand, as national stereotypes and attitudes shape international relations in a very real sense. This is true for both business and political contacts, but also for the attitudes of local residents towards the influence of foreign capital. A more economically in-depth approach to the topic of this paper, supported by access to a number of company archives, could further reveal to what extent British developers were involved in Amsterdam’s and other European capitals’ property affairs. Such an endeavour should be of interest to a wide array of academics, not only historians of Europe and cities, but financial geographers, property analysts and economists as well.

Acknowledgements

This article was mainly written during a research leave at Leicester’s Centre for Urban History. The author would like to thank Paul Knevel and Simon Gunn for granting him the opportunity to work abroad, and Alistair Kefford and Catherine Flinn for their comments on an earlier version of this article.

Disclosure statement

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tim Verlaan

Tim Verlaan is assistant professor of urban history at the University of Amsterdam, where he investigates the history of urban redevelopment and gentrification in Western European cities. He has published on these and other topics in, amongst others, a recent Dutch monograph, Planning Perspectives and Contemporary European History, and is an associate editor for Urban History.

Notes

1. Verhoeff, De Strijd.

2. Wagenaar, Town Planning, 465.

3. Ward, Planning the Twentieth-Century City, 227.

4. Marriott, The Property Boom, 13–23.

5. Kefford and Verlaan, “Building for Prosperity.”

6. Verlaan, “Producing Space,” 421.

7. Berman, All That is Solid, 63.

8. Marriott, The Property Boom, 24.

9. Pugh, “Olympia and York”; Rogers, The Geopolitics of Real Estate; Fainstein, The City Builders; Halbert and Attuyer, “Introduction”; Coakley, “The Integration of Property”; Van Loon, “Patient Versus Impatient Capital”; Soares de Magalhães, “International Property Consultants”; Rogers and Koh, “The Globalisation of Real Estate.”

10. Gordon, The Two Tycoons; Jack Rose, The Dynamics of Urban Property Development (London: Spon, 1985); Smyth, Property Companies; Scott, The Property Masters.

11. Thomas, “Prejudice and Pragmatism”; Harrison, “Money Spinners.”

12. Kefford, “Actually Existing Managerialism”; Shapely, “The Entrepreneurial City”; Shapely, “Governance in the Post-War City.”

13. Stevens, Developing Expertise.

14. Buiter, Hoog Catharijne; Buiter, “Naar een Internationaal Bouwconcern”; Van der Boor, Stedebouw in Samenwerking.

15. Saunier, Transnational History, 3, 10.

16. Büdenbender and Golubchikov, “The Geopolitics of Real Estate,” 76.

17. Harris and Moore, “Planning Histories.”

18. Brenner, “What is Critical Urban Theory?”

19. Merrifield, Henri Lefebvre, 81.

20. Harvey, “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism,” 6.

21. Ploeger, Regulating Urban Office Provision, 12.

22. Harvey, The Urbanization of Capital, 7.

23. Molotch, “The City as a Growth Machine,” 310.

24. Beckett, When the Lights Went Out, 89.

25. Scott, The Property Masters, 194–201.

26. Andry, Mourlon-Druol, Ikonomou and Jouan, “Rethinking European Integration History in Light of Capitalism,” 553–72.

27. See, for a recent empirical study of how neoliberalism affected urban policies during the post-war period, Phillips-Stein, Fear City, and for the intrinsic links between neoliberalism and urbanism Tochterman, “Theorizing Neoliberal Urban Development,” 65–87.

28. Sassen, Cities in a World Economy, 3.

29. Judt, Postwar, 360–2.

30. Mazower, Dark Continent, 297.

31. Edgerton, The Rise and Fall of the British Nation, 283.

32. Black and Pemberton, “Introduction,” 7.

33. Morgan, Britain Since 1945, 209.

34. Dow, The Management of the British Economy, 250.

35. Harrison, Seeking a Role, 312.

36. Millward, “The Rise of the Service Economy,” 242.

37. Marriott, The Property Boom, 8, 10.

38. Scott, The Property Masters, 143.

39. Watson, “The Financial Services Sector Since 1945,” 172.

40. Clark, Pension Fund Capitalism, 51; Harrison, Seeking a Role, 318.

41. Marriott, The Property Boom, 38–40.

42. Scott, The Property Masters, 169.

43. Thane, Divided Kingdom, 264–5.

44. Mandler, “New Towns for Old,” 208–27.

45. White, London in the Twentieth Century, 53.

46. Flinn, “The City of our Dreams?”; Flinn, Rebuilding Britain’s Blitzed Cities; Mandler, “New Towns for Old,” 219.

47. Saumarez Smith, “The Inner City Crisis,” 580.

48. Klemek, The Transatlantic Collapse of Urban Renewal, 83–9.

49. Thomas, “Prejudice and Pragmatism,” 89; Gold, The Practice of Modernism, 54.

50. Shapely, “Governance in the Post-War City,” 1289–92.

51. Howlett, “The “Golden Age,” 329.

52. Edgerton, The Rise and Fall of the British Nation, 309.

53. Clarke, Hope and Glory, 331.

54. Clarke, Hope and Glory, 337.

55. Scott, The Property Masters, 195.

56. Harrison, B. Finding a Role? The United Kingdom 1970–1990. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

57. Forster and Harper, “Introduction.”

58. Counter Information Services, The Recurrent Crisis of London.

59. Gowland and Turner, Reluctant Europeans, 83–95.

60. George, An Awkward Partner, 19, 29–30.

61. Ludlow, Dealing with Britain, 206–12; Daddow, “Introduction.”

62. Thane, Divided Kingdom, 306.

63. Morgan, Britain Since 1945, 342; Edgerton, The Rise and Fall of the British Nation, 269; Gowland, Wright and Turner, Britain and European Integration Since 1945, 72–3; Wall, The Official History of Britain and the European Community, 405–56.

64. Neal, “Impact of Europe,” 284.

65. Saunders, Yes to Europe!, 18.

66. Neal, “Impact of Europe,” 286–7; Beckett, When the Lights Went Out, 171.

67. Ramírez Pérez, “Crises and Transformations of European Integration,” 623.

68. Neal, “Impact of Europe,” 268.

69. Rollings, British Business, 260.

70. Ferguson, “Siegmund Warburg”; Dinan, Ever Closer Union, 365.

71. Abdelal, Capital Rules, 8; Maier, “Malaise,” 45.

72. Van Apeldoorn, Transnational Capitalism, 56.

73. Daddow, Britain and Europe Since 1945, 8.

74. Harrison, Finding a Role, 114.

75. Cf. Grob-Fitzgibbon, Continental Drift, 468.

76. Prak and Luiten van Zanden, Nederland en het Poldermodel, 249.

77. Rijksplanologische Dienst (hereafter: RPD), Jaarverslag 1963, 57.

78. RPD, Nota Inzake de Ruimtelijke Ordening, 22; RPD, Jaarverslag 1961, 47; RPD, Jaarverslag 1969, 69–70.

79. Clarke, Hope and Glory, 76.

80. Van Gool et al., Onroerend Goed, 3.

81. Ter Hart, Commercieel Vastgoed, 13.

82. Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting en Bouwnijverheid, Rapport van de Commissie Grondkosten, 42; Vleugels, 85 Jaar ABP, 76.

83. Rompelman, “1868/1969-2009: Een Terugblik,” 69.

84. Ashton and Hellema, “Introduction,” 13.

85. Haley, The British and the Dutch, 233.

86. Shapely, “Governance,” 1292.

87. Nederlands Instituut voor Ruimtelijke Ordening en Volkshuisvesting, Handleiding, 195–8.

88. Nelisse, Stedelijke Erfpacht, 193.

89. Tops and Korsten, “Het College van Burgemeester en Wethouders,” 183–96; Denters and Van der Kolk, “De Gemeente en het Raadslid,” 222–32.

90. Verlaan, De Ruimtemakers, 15.

91. Eley, Forging Democracy, 406.

92. Davidson, “Oud Stadsdeel.”

93. Duivenvoorden, Een Voet Tussen de Deur, 41.

94. Bijlsma, “Het Gaat om de Knikkers,” 3–4.

95. De Liagre Böhl, Amsterdam op de Helling.

96. Dinan, Ever Closer Union, 55.

97. Cf. Ewen, What is Urban History?, 116.

98. Harvey, The Urbanization of Capital.

99. Rodgers, Age of Fracture; Ther, Europe since 1989.

Bibliography

- Abdelal, R. Capital Rules: The Construction of Global Finance. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Andry, A., E. Mourlon-Druol, H. A. Ikonomou, and Q. Jouan. “Rethinking European Integration History in Light of Capitalism: The Case of the Long 1970s.” European Review of History: Revue européenne d’Histoire 26, no. 4 (2019): 553–572. doi:10.1080/13507486.2019.1610361.

- Ashton, N., and D. Hellema. “Introduction.” In Unspoken Allies: Anglo-Dutch Relations since 1780, edited by N. Ashton and D. Hellema, 9–16. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2001.

- Beckett, A. When the Lights Went Out: What Really Happened to Britain in the Seventies. London: Faber and Faber, 2009.

- Berman, M. All that is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. New York: Verso, 2010.

- Bijlsma, A. A. O., eds. “Het Gaat om de Knikkers – de Stad en de Stedelingen Staan op het Spel.” Wonen TA/BK 5, no. 19 (1974): 3–4.

- Black, L., and H. Pemberton. “Introduction.” In An Affluent Society? Britain’s Post-War “Golden Age” Revisited, edited by L. Black and H. Pemberton, 1–13. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004.

- Brenner, N. “What Is Critical Urban Theory?” City 13, nos. 2–3 (2009): 198–207. doi:10.1080/13604810902996466.

- Büdenbender, M., and O. Golubchikov. “The Geopolitics of Real Estate: Assembling Soft Power via Property Markets.” International Journal of Housing Policy 17, no. 1 (2017): 75–96. doi:10.1080/14616718.2016.1248646.

- Buiter, H. Hoog Catharijne: De Wording van het Winkelhart van Nederland. Matrijs: Utrecht, 1993.

- Buiter, H. “Naar een Internationaal Bouwconcern.” In Bredero’s Bouwbedrijf: Familiebedrijf, Mondiaal Concern, Ontvlechting, edited by M. J. Willem and A. O. Bekkers, 59–108. Amsterdam: Dutch University Press, 2005.

- Clark, G. L. Pension Fund Capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Clarke, P. Hope and Glory. Britain 1900–1990. London: Allen Lane, 1990.

- Coakley, J. “The Integration of Property and Financial Markets.” Environment and Planning A 26, no. 5 (1994): 697–713. doi:10.1068/a260697.

- Counter Information Services. The Recurrent Crisis of London. London: Counter Information Services, 1973.

- Daddow, O. J. “Introduction: The Historiography of Wilson’s Attempt to Take Britain into the EEC.” In Harold Wilson and European Integration: Britain’s Second Application to Join the EEC, edited by O.J. Daddow, 1–36. London: Frank Cass, 2003.

- Daddow, O. J. Britain and Europe since 1945: Historiographical Perspectives on Integration. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004.

- Davidson, H. “Oud Stadsdeel Niet Isoleren.” Plan 1, no. 7 (1970): 437–443.

- de Liagre Böhl, H. Amsterdam op de Helling: De Strijd om Stadsvernieuwing. Amsterdam: Boom, 2010.

- Denters, B., and H. van der Kolk. “De Gemeente en het Raadslid.” In Lokaal Bestuur in Nederland: Inleiding in de Gemeentekunde, edited by P. Tops and A. Korsten, 222–232. Alphen aan den Rijn: Samson, 1998.

- Dinan, D. Ever Closer Union: An Introduction to European Integration. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- Dow, C. The Management of the British Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1964.

- Duivenvoorden, E. Een Voet Tussen de Deur: Geschiedenis van de Kraakbeweging 1964–1999. Amsterdam, De Arbeiderspers, 2000.

- Edgerton, D. The Rise and Fall of the British Nation: A Twentieth Century History. London: Allen Lane, 2018.

- Eley, G. Forging Democracy: The History of the Left in Europe, 1850–2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Ewen, S. What Is Urban History? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Fainstein, S. The City Builders: Property, Politics, and Planning in London and New York. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994.

- Ferguson, N. “Siegmund Warburg, the City of London and the Financial Roots of European Integration.” Business History 51, no. 3 (2009): 362–380. doi:10.1080/00076790902843916.

- Flinn, C. “The City of Our Dreams? The Political and Economic Realities of Rebuilding Britain’s Blitzed Cities, 1945–54.” Twentieth Century British History 23, no. 2 (2012): 221–245. doi:10.1093/tcbh/hwr009.

- Flinn, C. Rebuilding Britain’s Blitzed Cities: Hopeful Dreams, Stark Realities. London: Bloomsbury, 2018.

- Forster, L., and S. Harper. “Introduction.” In British Culture and Society in the 1970s, edited by L. Forster and S. Harper, 1–12. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2010.

- George, S. An Awkward Partner: Britain in the European Community. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Gold, J. The Practice of Modernism: Modern Architects and Urban Transformation 1954–1972. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Gordon, C. The Two Tycoons: A Personal Memoir of Jack Cotton and Charles Clore. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1984.

- Gowland, D., and A. Turner. Reluctant Europeans: Britain and European Integration, 1945–1998. Harlow: Pearson Longman, 2000.

- Gowland, D., A. Wright, and A. Turner. Britain and European Integration since 1945: On the Sidelines. Routledge: Abingdon, 2010.

- Grob-Fitzgibbon, B. Continental Drift: Britain and Europe from the End of Empire to the Rise of Euroscepticism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Halbert, L., and K. Attuyer. “Introduction: The Financialisation of Urban Production: Conditions, Mediations and Transformations.” Urban Studies 53, no. 7 (2016): 1347–1361. doi:10.1177/0042098016635420.

- Haley, K. The British and the Dutch: Political and Cultural Relations Throughout the Ages. London: George Philip, 1988.

- Harris, A., and S. Moore. “Planning Histories and Practices of Circulating Urban Knowledge.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37, no. 5 (2013): 1499–1509. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12043.

- Harrison, B. Seeking a Role: The United Kingdom 1951–1970. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Harrison, E. “‘Money Spinners’: R. Seifert & Partners, Sir Frank Price and Public-Sector Speculative Development in the 1970s.” Architectural History 61 (2018): 1–22. doi:10.1017/arh.2018.10.

- Harvey, D. The Urbanization of Capital. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

- Harvey, D. “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation of Urban Governance in Late Capitalism.” Geografiska Annaler 71, no. 1 (1989): 3–17. doi:10.1080/04353684.1989.11879583.

- Howlett, P. “The ‘Golden Age’, 1955–1973.” In Twentieth-Century Britain: Economic, Social and Cultural Change, edited by F. Carnevali and J.-M. Strange, 320–339. Harlow: Pearson Longman, 1994.

- Judt, T. Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945. London: Vintage, 2010.

- Kefford, A. “Actually Existing Managerialism: Planning, Politics and Property Development in Post-1945 Britain.” Urban Studies, (2020): 004209802094903. OnlineFirst. doi:10.1177/0042098020949034.

- Kefford, A., and T. Verlaan. “Building for Prosperity: Private Developers and the Western-European Welfare State.” Session at the Fifth International Meeting of the European Architectural History Network, Tallinn, 13–16 June 2018.

- Klemek, C. The Transatlantic Collapse of Urban Renewal: Postwar Urbanism from New York to Berlin. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2011.

- Ludlow, P. Dealing with Britain: The Six and the First Application to the EEC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

- Maier, C. S. “‘Malaise’: The Crisis of Capitalism in the 1970s.” In The Shock of the Global: The 1970s in Perspective, edited by N. Ferguson, Charles S. Maier, Erez Manela, and Daniel J. Sargent, 25–48. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Mandler, P. “New Towns for Old.” In Moments of Modernity: Reconstructing Britain 1945–1964, edited by E. C. Becky, F. Mort, and C. Waters, 208–227. London: Rivers Oram Press, 1999.

- Marriott, O. The Property Boom. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1967.

- Mazower, M. Dark Continent: Europe’s Twentieth Century. London: Allen Lane, 1998.

- Merrifield, A. Henri Lefebvre: A Critical Introduction. New York: Routledge, 2006.

- Millward, R. “The Rise of the Service Economy.” In The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain, edited by R. Floud and P. Johnson, 238–326. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting en Bouwnijverheid. Rapport van de Commissie Grondkosten. The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij, 1962.

- Molotch, H. “The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place.” American Journal of Sociology 82, no. 2 (1976): 309–332. doi:10.1086/226311.

- Morgan, K. O. Britain Since 1945: The People’s Peace. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Neal, L. “Impact of Europe.” In The Cambridge Economic History of Modern Britain, edited by R. Floud and P. Johnson, 267–298. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Nederlands Instituut voor Ruimtelijke Ordening en Volkshuisvesting. Handleiding Voorbereiding Structuur- en Bestemmingsplannen. Alphen aan den Rijn: Samson, 1965.

- Nelisse, P. C. J. P. Stedelijke Erfpacht. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, 2003.

- Phillips-Stein, K. Fear City: New York’s Fiscal Crisis and the Rise of Austerity Politics. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2017.

- Ploeger, R. A. Regulating Urban Office Provision: A Study of the Ebb and Flow of Regimes of Urbanisation in Amsterdam and Frankfurt am Main 1945–2000. Amsterdam: S.N, 2004.

- Prak, M., and J. L. van Zanden. Nederland en het Poldermodel: Sociaal-economische Geschiedenis van Nederland, 1000–2000. Amsterdam: Bakker, 2013.

- Pugh, C. “Olympia and York, Canary Wharf and What May Be Learned.” Property Management 14, no. 2 (1996): 5–18. doi:10.1108/02637479610115503.

- Ramírez Pérez, S. M. “Crises and Transformations of European Integration: European Business Circles during the Long 1970s.” European Review of History: Revue européenne d’Histoire 26, no. 4 (2019): 618–635. doi:10.1080/13507486.2019.1613964.

- Rijksplanologische Dienst (RPD). Jaarverslag 1963. The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij, 1964.

- Rijksplanologische Dienst (RPD). Nota Inzake de Ruimtelijke Ordening in Nederland. The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij, 1960.

- Rijksplanologische Dienst (RPD). Jaarverslag 1961. The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij, 1962.

- Rijksplanologische Dienst (RPD). Jaarverslag 1969. The Hague: Staatsdrukkerij, 1970.

- Rodgers, D. T. Age of Fracture. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2011.

- Rogers, D. The Geopolitics of Real Estate: Reconfiguring Property, Capital and Rights. London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

- Rogers, D., and S. Y. Koh. “The Globalisation of Real Estate: The Politics and Practice of Foreign Real Estate Investment.” International Journal of Housing Policy 17, no. 1 (2017): 1–14. doi:10.1080/19491247.2016.1270618.

- Rollings, N. British Business in the Formative Years of European Integration 1945–1973. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Rompelman, D. “1968/1969-2009: Een Terugblik.” Vastgoedmarkt 36, no. 4 (2009): 66–71.

- Rompelman, D. “1968/1969-2009: Een Terugblik.” Vastgoedmarkt 36, no. 4 (2009): 66–71.

- Rose, J. The Dynamics of Urban Property Development. London: Spon, 1985.

- Saumarez Smith, O. “The Inner City Crisis and the End of Urban Modernism in 1970s Britain.” Twentieth Century British History 27, no. 4 (2016): 578–598.

- Saunders, R. Yes to Europe! The 1975 Referendum and Seventies Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Saunier, P.-Y. Transnational History. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Scott, P. The Property Masters: A History of the British Commercial Property Sector. London: Taylor and Francis, 1996.

- Shapely, P. “The Entrepreneurial City: The Role of Local Government and City-Centre Redevelopment in Post-War Industrial English Cities.” Twentieth Century British History 22, no. 4 (2011): 498–520. doi:10.1093/tcbh/hwq049.

- Shapely, P. “Governance in the Post-War City: Historical Reflections on Public-Private Partnerships in the UK.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37, no. 4 (2013): 1288–1304. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01113.x.

- Smyth, H. Property Companies and the Construction Industry in Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- Soares de Magalhães, C. “International Property Consultants and the Transformation of Local Markets.” Journal of Property Research 18, no. 2 (2001): 99–121. doi:10.1080/09599910110014156.

- Stevens, S. Developing Expertise: Architecture and Real Estate in Metropolitan America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

- Ter Hart, H. W., Commercieel Vastgoed in Nederland: Een Terreinverkenning. Vlaardingen: Nederlands Studie Centrum, 1987.

- Thane, P. Divided Kingdom: A History of Britain, 1900 to the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Ther, P. Europe since 1989: A History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Thomas, A. “Prejudice and Pragmatism: The Commercial Architect in the Development of Postwar London.” Gray Room 71 (2018): 88–155. doi:10.1162/grey_a_00243.

- Tochterman, B. “Theorizing Neoliberal Urban Development: A Genealogy from Richard Florida to Jane Jacobs.” Radical History Review 112, no. 1 (2012): 65–87. doi:10.1215/01636545-1416169.

- Tops, P., and A. Korsten. “Het College van Burgemeester en Wethouders.” In Lokaal Bestuur in Nederland: Inleiding in de Gemeentekunde, edited by P. Tops and A. Korsten, 183–196. Alphen aan den Rijn: Samson, 1998.

- van Apeldoorn, B. Transnational Capitalism and the Struggle over European Integration. London: Routledge, 2002.

- van der Boor, W. S. Stedebouw in Samenwerking: Een Onderzoek naar de Grondslagen voor Publiek-Private Samenwerking in de Stedebouw. Alphen aan den Rijn: Samson, 1991.

- van Gool, P., R. M. Weisz, and P. G. M. van Wetten. Onroerend Goed als Belegging. Groningen: Wolters-Noordhoff, 2007.

- van Loon, J. “Patient versus Impatient Capital: The (Non-) Financialization of Real Estate Developers in the Low Countries.” Socio-Economic Review 14, no. 4 (2016): 709–728. doi:10.1093/ser/mww021.

- Verhoeff, P. De Strijd om de Stad. Hilversum: VPRO, 1978.

- Verlaan, T. “Producing Space: Post-war Redevelopment as Big Business, Utrecht and Hannover 1962–1975.” Planning Perspectives 34, no. 3 (2019): 415–437. doi:10.1080/02665433.2017.1408486.

- Verlaan, T. De Ruimtemakers: Projectontwikkelaars en de Nederlandse Binnenstad 1950–1980. Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2017

- Vleugels, M. 85 Jaar ABP. Heerlen: ABP, 2007.

- Wagenaar, C. Town Planning in the Netherlands since 1800. Rotterdam: 010, 2010.