ABSTRACT

This article considers the development of hospitals and their funding mechanisms across the Ottoman imperial (ca. 1516–1830) and French colonial (1830–1962) states in Algeria. The first section of the article describes Islamic welfare structures introduced under the stewardship of the Ottoman Empire, and explains how these were appropriated, outlawed and reconfigured in the wake of the French invasion of Algiers. The second section discusses French and colonial policies on assistance publique (public assistance) and their implementation in rural zones of Algeria in the early decades of the twentieth century to create segregated infirmeries indigènes (‘native’ infirmaries). The third section of the article examines how officials contrived to limit the role of the state in financing hospitals by increasing taxes on ordinary Algerians, especially taxes based on Ottoman precedents. The final section uses financial audits conducted by the Cour des comptes (Court of Audit) in Paris, along with other administrative records, to reveal how revenues misrepresented as Islamic were spent, including their use to reduce the tax liabilities of elites associated with the French colonial state. This case shows the enduring importance of Ottoman and Islamic infrastructures to French colonial welfare in Algeria and helps open Algeria up for comparison with the politics of welfare provision in other imperial and post-imperial states.

On 17 October 1926, the front page of Algeria’s most popular Arabic-language newspaper, al-Najah, featured an article titled ‘A Tour in the Civil Hospital’.Footnote1 In response to complaints from patients, al-Najah’s co-founder and editor Smaïl Mami had conducted an undercover investigation of the main hospital in Constantine, principal city of the Department of Constantine in eastern Algeria. He discovered dusty wards, dirty bedlinens and meals that were served in broken cups and petrol canisters. Patients questioned by Mami made no specific complaints against the physicians in charge (they had nothing good to say about them either), but lamented the cruel treatment and neglect they received from female nursing staff. The French authorities in Algeria considered al-Najah as non-political in comparison to other Arabic-language newspapers, but its editor hardly spared them from criticism:

It is the duty of the government to reflect on the fact that it spends immense amounts of money on nursing the weak among its flock. They should receive the best treatment and nursing. The number of people leaving the hospital cured should be greater than the number leaving it dead.

Quite simply, Mami protested, ‘the hospital should not be a slaughterhouse’.Footnote2

‘A Tour in the Civil Hospital’ calls to mind the writings of Frantz Fanon, the Martiniquan psychiatrist and revolutionary theorist whose powerful critique of colonial medicine in Algeria went far beyond a discussion of hospitals’ material deficiencies.Footnote3 Writing at the height of the Algerian War of Independence (1954–62), Fanon saw clearly how the values of French medicine had been compromised and perverted through close association with colonialism. With the outbreak of revolution in 1954, state hospitals had remained open to Algerian patients, at least nominally. However, the following year, French government decrees restricted or outright banned the sale of essential hygienic and pharmaceutical items, severely reducing Algerians’ access to treatment. Some doctors informed on patients and were complicit in torture.Footnote4 These were not isolated incidents, Fanon wrote, but part of a system of oppression. ‘The sudden deaths of Algerians in hospitals,’ explained Fanon, ‘are interpreted as the effects of a murderous and deliberate decision, as the result of criminal maneuvres on the part of the European doctor.’Footnote5

Unlike Fanon, who characterized Algerian attitudes to French colonial medicine during one of the most violent wars of decolonization, Mami expressed concern for everyday conditions in hospitals and their financial costs when the colonial status quo seemed assured. In the wake of the First World War, fiscal injustice became an increasing source of discontent for Algerians, who had served and died for France in large numbers. Even after French authorities reformed the most discriminatory aspects of the colonial tax system in 1918–19, tax resistance and demands for tax equality developed into a key site of political contestation.Footnote6 Mami judged the civil hospital in Constantine according to this calculus: he presented the deaths of hospital patients in terms of the inefficient use of tax contributions.

Mami’s reporting raises fundamental questions about hospital finance in Algeria, particularly during the first decades of the twentieth century, a period when facilities called infirmeries indigènes (‘native’ infirmaries) were established in the hinterlands of colonial cities. How were hospitals and infirmaries financed in colonial-era Algeria? Which social groups were able to access them? Who paid for patients’ treatment and nursing? Who had oversight over hospital funding?Footnote7 Generations of historians have helped us understand the economic, social, cultural and intellectual systems and values that underpinned colonial medicine in Algeria, including the determination of European settlers to oppose spending on services for Algerians.Footnote8 What has been missing from these studies, until now, is detailed attention to the fiscal tools and revenue streams that funded hospitals.Footnote9 This means historians have missed the existence of on-the-ground tussles among officials, municipal commissioners and property owners to avoid paying for hospitals and other forms of welfare, for example, or the proliferation of new philanthropic discourses and initiatives pursued by wealthy elites, to give another example, of the kind that have been identified by historians of other colonial states.Footnote10

Marginalization of financial considerations in the literature can be traced to several different, if interrelated, reasons. One is characteristics and politics of archives located in different sites in Algeria and France. Records about hospital finance in Algeria under French occupation were fragmented by design: external oversight procedures left paper trails in both Algeria and France. This raises barriers to researchers without resources, institutional power and personal circumstances that allow for extensive travel to multiple sites, particularly as the ownership and accessibility of Algeria’s colonial-era archives remain contested.Footnote11 This article mobilizes documentation in Arabic and French that I gathered from multiple archives in Algeria and France over the course of a decade, with help from numerous archivists and (in 2018) from researchers Claire Khelfaoui and Ouanassa Siari Tengour. This enables me to track revenues across hierarchical management processes that involved administrative structures in communes mixtes (mixed communes) in rural regions of Algeria, prefectures in Algiers, Oran and Constantine, the colonial government in Algiers, and the Cour des comptes (Court of Audit) in Paris.Footnote12 Only with such a breadth of sources can we begin to understand how hospitals were actually funded, but many of these documents have not been used by historians until now—particularly the Algerian records of the Cour des comptes, discussed here for the first time.Footnote13 It is unsurprising, then, that scholars depending on a single archive have drawn a partial picture of healthcare finance or missed it altogether.

Another reason, a paradoxical one, is Algeria’s longstanding significance as a key case for understanding colonial medicine. Isabelle Grangaud and M’hamed Oualdi argued that the ‘success’ of colonial history as a field has encouraged scholars to double down on the geopolitical and temporal boundaries of French colonialism, ignoring the fact that Algeria was an integral part of the Ottoman Empire for more than 300 years (ca. 1516–1830).Footnote14 The blind spots identified by Grangaud and Oualdi also matter for histories of healthcare and medicine.Footnote15 While on a formal level, Algeria was legally assimilated to France in 1848, meaning the gradual, if incomplete, convergence of its tax laws and social welfare policies to those of the metropole, the Ottoman Turkish substrate and Islamic law (as well as Halakha or Jewish law and Berber customary law) remained important.Footnote16 Accordingly, this article begins by looking back on Ottoman-era infrastructures dismantled by French officials. It examines a deed of habous (endowment, also known as waqf) alongside administrative and financial records, including audits, to find further traces of Ottoman and Islamic ideologies and funding sources that French authorities usurped, outlawed and reconfigured in the years and decades following the invasion of Algiers.Footnote17

It is impossible to calculate in precise terms the extent of Algerians’ financial contributions to hospitals during more than 130 years of French colonial rule. What is beyond a doubt, and what this article shows, is that funding mechanisms for government hospitals established in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—hospitals considered as French and colonial by officials and even by Algerians themselves—derived importantly from Ottoman and Islamic precedents. The story of how pre-colonial fiscal tools and other funding sources such as habous were appropriated (and how their origins were conveniently forgotten) resembles what Ann Laura Stoler called ‘imperial ruins and ruination’ and Faisal Devji referred to as ‘the scene of a crime’.Footnote18 One revenue stream identified in this article and analysed for its social and political implications is a tax known as fêtes ‘Eurs’ that was levied on Algerian weddings and other gatherings, and spent on so-called ‘native’ infirmaries. Even after officials in Algeria’s major cities and magistrates at the Cour des comptes in Paris declared fêtes ‘Eurs’ to be an illegal tax, politicians and colonial administrators justified its continued collection through appeals to Islamic tradition—and yet the tax originated in Ottoman lands and was not, in fact, religiously inspired.

The eclipse of Ottoman welfare and emergence of assistance publique

From the earliest days of the French invasion of Algiers in 1830, French military doctors and officials invoked the decline of Arab and Islamic medicine under Ottoman suzerainty. Several historians have challenged this politically loaded framework. Wafia Nafti examined writings of European clerics, travellers and doctors in the service of the Ottoman deys (honorific title for ruler) in Algiers during the sixteenth–eighteenth centuries. She found that while their accounts discussed the shortcomings of hospital provision in Algiers—only a handful of institutions existed to support the sick, elderly and social groups such as Christian captives and army pensioners—they overlooked evidence of the role of alms and charitable endowments in supporting vulnerable people and therefore failed to fully comprehend community practices of health.Footnote19 Adda Bendaha acknowledged that the Ottoman regency and later the state established briefly by amir (military and religious leader) ʿAbd al-Qadir (1832–47) did not provide medical services to the general population (nor did the French state at the time), but showed the ways the amir envisaged a 'modern' health system.Footnote20 As Ahmed Ragab explained, there is a sense in which accusations of decline were a useful discursive strategy (and not only in colonial Algeria) for French doctors to legitimize new medical schools, a new medical elite and their associated medical practices.Footnote21

Discursive invocations of pre-colonial neglect also importantly helped draw attention away from the widescale transfer of social welfare assets from indigenous to French control. Chief among these assets were religious endowments called awqaf (sing. waqf), known colloquially in North Africa as habous (from form II of the verb habasa, meaning to tie up inalienably). A deed of waqf allows an individual to circumvent Islamic inheritance law and bestow property and possessions outside the legal line of succession, for pious or secular ends.Footnote22 As much as one-half of agricultural land in pre-colonial Algeria was designated as waqf, and the rents from the properties thus endowed—along with independent charitable donations and state-distributed income from corsairs’ booty—routinely funded social goods such as public baths, water fountains, schools and hospices and asylums for the sick and vulnerable.Footnote23 Under Ottoman stewardship, management of charitable waqf in Algiers was brought under a single foundation known as Waqf al-Haramayn, al-Haramayn being the term used by Muslims to describe the two holy cities of Islam, Mecca and Medina. While Ottoman rulers did not administer these resources directly, the state did ‘create an atmosphere conducive to activating the town’s endowment potential’ by providing a legal and administrative framework enabling ‘good, rational management’, thereby supporting expansion of social welfare institutions.Footnote24

Waqf became a major resource for the French state in Algeria when it was seized by the military, inventoried and assimilated to state property in the years and decades following the invasion.Footnote25 Among other objectives, waqf was used to underpin wider state poor law.Footnote26 The process by which this occurred can be seen in relation to a declaration of habous by al-Hajj ʿAbd al-Rahman Ibn ʿAli al-Qinʿai on 22 June 1866 in the time of ‘Napoleon [III], Sultan of the French’.Footnote27 Having no surviving children, the twice married, twice divorced al-Qinʿai tied up his worldly possessions for the benefit of ‘the poor among the Muslims resident in Algiers incapable of earning due to illness or blindness or loss of a limb or age’.Footnote28 In creating the habous, al-Qinʿai followed the official madhhab of the Ottoman Empire, the Hanafi legal school, since the Hanafi interpretation of family endowment law—in contrast to that of the Maliki school that predominated in North Africa—allowed him to retain control and use of his property and other assets during his lifetime.Footnote29 The value of the habous exclusive of annual income from rents was estimated at 611,146F89, representing a considerable fortune.Footnote30 Following al-Qinʿai’s death on 10 January 1868, responsibility for administering the endowment and supervising its accounts devolved to the Maliki mufti (legal expert) and qadi (judge) of Algiers, but the French prefect of Algiers ordered the transfer of the endowment to the city’s bureau de bienfaisance musulman (Muslim welfare bureau), an institution created by imperial decree on 5 December 1857.Footnote31 One of the beleaguered religious officials on the receiving end of the prefect’s instructions, the qadi Hamida Ben al-ʿAmmali, described how he was verbally intimidated by the French director of the Muslim welfare bureau. He was also issued with an admonitory letter, ‘in which I was advised of my best interest and ordered to hand supervision over to the appointed bureau’.Footnote32

The dispute over al-Qinʿai’s legacy rumbled on until the French government eliminated Islamic property law in Algeria on 26 July 1873, with the passage of the loi Warnier (Warnier law). Since the deed of habous was now invalid under French law, ownership of al-Qinʿai’s property was transferred to the Muslim welfare bureau in Algiers in line with the prefect’s orders, thereby superseding al-Qinʿai’s wishes and frustrating the hopes of his legal heirs.Footnote33 In the year of the transfer, 2343 patients received medical treatment, both at the welfare bureau and in their own homes, and 1268 families deemed unable to earn a living were supported by funds from al-Qinʿai’s bequest.Footnote34 But instead of being managed by the original trustees who were members of the Maliki religious establishment, the proceeds of the habous now ensured employment for Europeans, who included the director of the welfare bureau, administrative staff and a resident doctor. The poor of Algiers benefited, as the late al-Qinʿai had intended, but their benefactors assumed a French, rather than a Muslim, countenance.

For the next three decades, the Muslim welfare bureau in Algiers and its counterpart in the city of Constantine constituted the only form of official state welfare provision for the Algerian population.Footnote35 In 1904, during a debate in the Délégations financières algériennes (Algerian financial delegations), Algerian delegate and notable Si Mustapha el Hadj Moussa called on the French government to provide free hospital treatment to Algerians.Footnote36 Moussa had seen first-hand the demand for medical services. In 1897, for instance, he oversaw creation of a société de secours (benefit society) for sick people who appealed for help and shelter at the Sidi Abderrahmane Mosque in Algiers where Moussa was wakil (trustee or agent designated by a qadi).Footnote37 Justifying the expense that would be incurred in expanding hospital provision, Moussa explicitly invoked the seizure of habous:

You are not unaware that the rents from habous properties were for the most part designed to help the unfortunate. These properties were taken and sold by the Service des domaines [land tenure service] and the remaining buildings in Algiers (one hundred houses) were subsequently provided to the Mustapha civil hospital in 1875, which sold them for profit.Footnote38

Prior to the elimination of Islamic property law, the office of wakil entailed administration of habous and Moussa presumably maintained his own system of record-keeping. Officials confessed to lack of knowledge of the transactions (it was ‘fait qui serait à verifier’) and argued that if it were true that the properties had been seized, their sale must have benefited Algeria’s indigenous population.Footnote39

Moussa’s intervention in the debating chamber of the Délégations financières algériennes was part of a broader discussion among French officials and settler politicians—some of whom combined politics with private medical practice—about how, and to what extent, French Republican laws on medical assistance and public health should apply to Algeria. In parallel, settler doctors embedded tropes of Ottoman-era neglect towards public health in the curriculum at the Algiers École de médecine (medical school), articles in medical journals and pamphlets for a wider settler audience.Footnote40 Certainly, the pre-colonial system of waqf and the institutions it supported were not assistance publique (public assistance) in the sense defined by French Republican law, discussed later in this article. However, as this section has shown, waqf depended on the Ottoman state for its efficient management and provided vital public services to the most vulnerable in society. How, then, were Ottoman-era welfare and its funding sources so easily disregarded? French officials during the Second Republic and Second Empire were familiar with Algeria’s waqf resources, not least because they were required to resolve ongoing legal challenges caused by their expropriation, as can be seen with the legacy tied up by al-Qinʿai. This was no longer the case by the early twentieth century, when Islamic property law was no longer legal. Since the dismantling of waqf also brought an end to the systems that had documented assets to see that they reached their intended beneficiaries, Moussa’s ‘You are not unaware’ was plausibly deniable by French officials. As a later section will show, a similar process of appropriation and forgetting took place in relation to the revenues used to establish rural infirmaries.

‘Not actual hospitals’

Moussa called for Republican welfare laws to apply to Algerians as well as settlers. In France, the loi du 15 juillet 1893 sur l’assistance médicale gratuite (law of 15 July 1893 on free medical assistance) pledged free health care in the form of doctors’ home visits and hospital treatment to people classed as indigent (destitute), making local government responsible for bearing the cost. In Algeria, the settler-dominated Délégations financières algériennes voted to apply the 1893 law partially, with modifications.Footnote41 Delegates proposed the creation of distinct funding mechanisms for settlers who were French citizens and those who were not, and different ways of sharing costs across communal budgets and the central budget of the colony were considered.Footnote42 It was unclear in these debates how assistance for Algerians (who represented 86% of the population at the close of the nineteenth century) would be funded or if they would benefit at all.Footnote43

A major difficulty was the failure of the state to create institutions for public assistance outside major cities and colonial settlements, and the unwillingness of localities to pay towards their costs, which meant that most Algerians as well as settlers in rural areas were unable to lay claim to the law’s provisions.Footnote44 In 1900, the French state legally recognized 16 civil hospitals in Algeria. Civilians also had the option of being treated in six ‘mixed’ military hospitals alongside soldiers. Finally, six hôpitaux indigènes (‘native’ hospitals) run by Catholic religious societies—the Pères blancs (White Fathers) and Soeurs blanches (White Sisters)—and financed by the French state accepted only Muslim patients.Footnote45 All but five of these establishments were located along the Mediterranean littoral and were therefore geographically inaccessible to rural populations, in other words, to most Algerians. Historian and social scientist Djilali Sari calculated that, at the end of the nineteenth century, ‘eighty-eight per cent of Algerians were excluded from [hospitals], even though they were financed almost exclusively by resources from Algerians’.Footnote46 Delving into the particulars, we find the distribution of benefits compared with contributions to be even more unequal than Sari suggested. In 1900, less than 0.003% of the Algerian population (approximately 10,000 people) received treatment in the abovementioned hospitals and yet Algerian contributions to the whole of what was called ‘public’ assistance the following year amounted to 2,725,550F or one-quarter of total annual expenditure.Footnote47

To increase access to hospitals in the hinterlands of colonial cities, the most senior French official in Algeria, Governor General Paul Révoil, issued an administrative circular on 21 November 1901 ordering the creation of a small number of infirmeries indigènes (‘native’ infirmaries).Footnote48 By designating the proposed infirmaries as ‘native’, Révoil indicated their intended users were to be Algeria’s Muslim population but not the autochthonous Jewish population, the majority of whom were naturalized French citizens, or settlers. Revenues were collected centrally through the impôts arabes (Arab taxes: see later in this article) and design proposals were discussed locally, but after two years ground had not been broken for any of the planned infirmaries.Footnote49 Some nine months after Moussa’s speech, on 5 December 1904, Révoil’s successor Governor General Charles Jonnart issued his own administrative circular calling for the establishment of assistance médicale des indigènes (‘native’ medical assistance), including the creation of ‘native’ infirmaries.Footnote50 Archival evidence suggests Jonnart and other senior officials were motivated to extend some form of medical assistance to Algerians by a sense of anxiety about the viability of settler colonialism, which depended on Algerian labour and a shrinking European settler population, in the face of real and perceived threats from frequent epidemics. Growing imperial rivalry among European powers to exert political influence over the Sultanate of Morocco and what was considered as Islamic Africa, including influence achieved through medical propaganda, provided an additional stimulus.Footnote51

Financial considerations, not functionality, were the priority for senior officials when outlining plans for medical assistance for Algerians. As Révoil made clear, and Jonnart reiterated, ‘native’ infirmaries were ‘not [to be] actual hospitals equipped with all modern developments, the costs of construction of which would exceed our resources, but modest and inexpensive facilities’.Footnote52 In other words, wrote Pasteurian scientist and settler Henri Soulié, a booster for the scheme, the goal was to build ‘small establishments adapted to [Algerian] habits [… not] as if it were a French region or an agglomeration of Europeans’.Footnote53 Food purchasing and preparation was one area where Soulié envisaged achieving important savings, since it was expected that orthodox Muslim patients would abstain from drinking wine at meals (as much as a quarter of the prix de journée, the cost per patient bed day, in some nineteenth-century French hospitals was spent on wine).Footnote54 Soulié and other officials considered that additional efficiency gains could be made by employing Algerian auxiliaires médicaux (medical auxiliaries) to assist in infirmaries under a doctor’s supervision.Footnote55 Within three months, Révoil’s and Jonnart’s vision for ‘native’ infirmaries had been hastily adopted in 50 communes de plein exercice and communes mixtes. From 1912 until 1926, when rural medical assistance was reorganized, around 82 infirmaries received and treated patients (see and ).

Table 1. Number of infirmaries, beds and Algerian patients treated with average cost of bed day and length of stay, 1904–26

Figure 1. Location and date of creation of ‘native’ infirmaries established in Algeria, 1906–14.

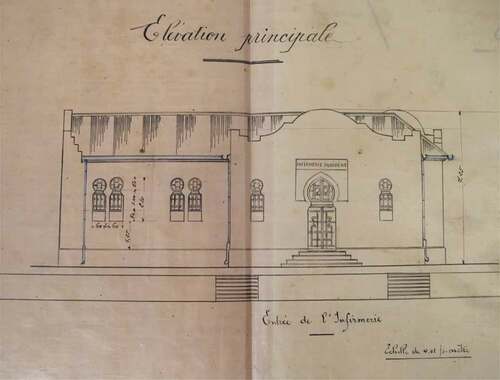

By inviting communes to establish ‘not actual hospitals’, senior officials authorized mayors and administrators to adapt existing structures for use as infirmaries. Not all the buildings chosen—they included old hospitals, a dilapidated house, a mosque, a courtroom, abandoned forts dating from the Ottoman and Napoleonic eras, and lean-to structures open to the elements—were suited to the purpose.Footnote56 Where no existing property was available for conversion into an infirmary, there was a scramble to erect new buildings. Jonnart recommended that all public buildings in Algeria should be constructed ‘in the Arab style’, which he believed would make them more culturally acceptable to Muslims.Footnote57 This ideal was followed closely by the European architect who drew up plans for an infirmary in Rabelais (present-day ʿAyn Miran) in 1905 (). Ironically, the infirmary’s aesthetics were a failure in terms of finance and function: the architect’s fees and construction costs ran to 14,000F for a building that lacked piped water and laundry facilities.Footnote58 Nor did the building age well. ‘You will find it attractive in appearance with its Moorish façade, its mullioned window frames,’ wrote Soulié for a publication celebrating the centenary of the French invasion of Algiers in 1930. ‘If you wish to retain this good impression, do not enter, because you will be in a hurry to leave.’Footnote59 An infirmary built in Taher, initially criticized for not conforming to Jonnart’s ‘neo-Moorish’ design brief, was subsequently held up as a model of good design, until it was recognized that the building possessed insufficient space to isolate infectious patients, launder bedding and indeed to meet demand for services.Footnote60

Figure 2. Plans for a ‘neo-Moorish’-style Infirmerie indigène, Rabelais. Archives nationales d’Outre-Mer (France), February 20, 1905, Commune mixte de Ténès. Q1 – Assistance publique, organisation, “Batiments communaux. Travaux neufs. Projet de construction d’une Infirmerie Indigène dans le centre de Colonisation de Rabelais.” Image taken by the author. Reproduced with permission.

The number of Algerians admitted to hospitals and infirmaries was very small. Nevertheless, the creation of infirmaries did lead to admissions doubling between 1904 and 1906 (from 6191 to 12,287 patients). Subsequent annual increases were more modest, and the occupancy rate of infirmaries never exceeded more than an average of 11.69 patients per hospital bed per annum during the period 1904–26 (in 1909, see ). The relatively small number of admissions was due to a combination of factors. Colonial officials and settler physicians habitually emphasized demand-side issues and blamed the perennial colonial bugbears of Muslim culture and orthodox rules of gender segregation for keeping Algerians out of French hospitals and away from medical techniques such as smallpox vaccination.Footnote61 Anecdotal evidence collected by one infirmary physician suggested how bureaucratic procedures required for admission and the financial cost deterred potential patients. One individual who refused treatment in the Rabelais infirmary (despite the building’s ‘Arab’ design features) was reported to say, ‘I have only one cow, the taxman will take it from me to pay the hospital.’Footnote62 (As the next section will show, fear of the tax collector was wholly warranted.) While unwillingness to seek help for these and other reasons must be considered a factor, there is ample evidence that state medical services were welcomed by some Algerians, and that the problem lay with supply as well as demand.Footnote63

Although established with the intention of being more accessible to Algerians, infirmaries were in administrative centres, not in the villages and semi-nomadic camps where most Algerians lived, and so physical problems of access remained. Sufferers faced restrictions based on residence, health conditions and religious confessional identity/race.Footnote64 Administrators and doctors scrutinized individuals’ circumstances to decide who was entitled to inclusion on the liste des indigents (list of the destitute) and who was not, and determined if treatment was ‘medically useful’ or merely palliative, in which case they might refuse to issue a bulletin d’admission (admission slip).Footnote65 More generally, there were problems with length of stay, with most infirmary patients spending long periods in establishments which, as noted earlier, were tightly restricted for space. All these factors meant that consultations were offered to only a tiny fraction of people who needed them. Despite this, the upward trend in admissions led to increasing expenditures.

During the First World War, the mobilization of medical staff and shortages of medicines forced some infirmaries to close.Footnote66 When infirmaries returned to regular service following the war, operating costs soared (although five infirmaries were so dilapidated that services were suspended in 1920, and equipment was found to have rotted and rusted away in many more establishments).Footnote67 As Barry Doyle showed for metropolitan France, the large budget deficit following the war and depreciation of the French franc ‘produced a crisis in hospital funding […] with inflation of around 500% in 1914–20ʹ.Footnote68 In Algiers, the cost of food almost quintupled between 1914 and 1924.Footnote69 Across Algeria, aspects of hospital economy that were supplied by private contractors, such as food preparation, had to be renegotiated to take account of inflation.Footnote70 The effects of inflation were more acute for infirmaries further from Algiers, because of the length of supply chains and poor communications infrastructure. This was reflected in variations across the average prix de journée, which averaged 1F21 in the Department of Algiers in 1919 compared with 3F24 and 4F12 respectively in the departments of Constantine and Oran.Footnote71 By 1926, the average prix de journée across the colony had risen to 10F79.Footnote72

‘I have seen many of these native infirmaries,’ pronounced delegate Dr Charles Aboulker in a 1921 session of the Délégations financières algériennes. ‘They seemed to me to be establishments that did not meet the target for which they had been created.’Footnote73 But what was that target? From one perspective, infirmaries did (narrowly) widen access to state medical assistance for Algerians in the areas where they were established. From another perspective, infirmaries formally inscribed religious and racial segregation into hospital provision, although this fact was resolutely denied by French officials such as JonnartFootnote74:

[The intention was] not at all to separate medical assistance for natives from that of Europeans on principle, but to supplement for the benefit of the natives the organization of this assistance in regions where they are too far from hospitals to be able to benefit and to provide them with facilities where they feel a little more at home than in our ordinary hospitals.Footnote75

This explanation was spurious. Whereas civil hospitals were managed by the Bureau de l’Intérieur (Interior Office), infirmaries came under the authority of the Bureau des Affaires indigènes et de la Police (Office of ‘Native’ Affairs and Police), marking them as an extension of the colonial security apparatus. Official government reports and design guidance clearly stated that infirmaries were explicitly ‘reserved for our Muslim subjects’ and should be built to different aesthetic and functional specifications than hospitals designed for Europeans. Care and treatment provided to Algerian patients in infirmaries was designed to cost less than if these same patients sought treatment in civil hospitals and it seems that some progress was made towards this goal.Footnote76

Despite official efforts to mark infirmaries as ‘native’, European settlers were known to seek treatment in them, for the simple reason that there usually was no other hospital to be found in rural zones.Footnote77 This situation continued until the end of 1926, the same year that Smaïl Mami called on the French government to consider the efficiency of its spending on hospitals. Against the backdrop of rising costs, Governor General Maurice Violette issued a circular ordering mayors and administrators to repurpose ‘native’ infirmaries as hôpitaux auxiliaires (auxiliary hospitals) open to settlers and Algerian Jews as well as Muslims.Footnote78 Each auxiliary hospital was placed under the oversight of an administrative commission comprising two ‘European’ and two ‘native’ notables.Footnote79 From 1 October 1927, the central government assumed increasing responsibility for reimbursing communes for the costs of hospitalization in these establishments.Footnote80 This new approach was driven by settler demand for hospital services in rural areas: it was deemed uneconomic to operate separate healthcare structures for settlers and Algerians. Publicly, the renamed auxiliary hospitals were hailed as evidence ‘of the colonial project moving forward in the interest of all populations, without distinction of race or religion’.Footnote81 In this way, officials and journalists indirectly acknowledged that, prior to this point, the hospital system had been set up to discriminate along racial and religious lines, as closer study of infirmary finances makes clear.

Limiting colonial liabilities: the mechanisms

Although successive governors general called for the creation of infirmaries in 1901 and 1904, they also made clear the government in Algiers would not commit to paying for them. Several decades earlier, the décret du 23 décembre 1874 portant organisation du service de l’assistance hospitalière en Algérie (decree of 23 December 1874 for the organization of the service for hospital care in Algeria) applied French governance and financial organization to civil hospitals and hospices in Algeria. The decree recognized three classes of potential income and expenditure for these establishments. First, recettes extraordinaires (extraordinary revenue), formed of non-state sources of income such as philanthropic gifts and bequests, were supposed to cover construction and repair costs for buildings and equipment. Second, reimbursement of the prix de journée by patients along with recettes ordinaires (regular revenue) accruing from rents and investment returns were intended to meet operating costs such as staff, medicines and other equipment, laundry, lighting, heat, janitorial services and insurance. Patients recognized as destitute were exempt from paying the prix de journée, which would instead be reimbursed from the communal or colonial budget, depending on where the patient claimed residence. The third funding stream envisaged by the 1874 decree was recettes spéciales (special revenue) in the form of occasional upfront subsidies from the state to provide working capital.Footnote82 In other words, hospitals in Algeria were placed on the same financial footing as those in metropolitan France, where the central state was keen to increase its oversight of local welfare initiatives but not to fund them.Footnote83

Unfortunately, the streams of hospital revenue envisaged by French lawmakers were mostly non-existent for infirmaries in rural Algeria. Unlike Mustapha Hospital in Algiers, which had amassed wealth from the sale of waqf properties, as discussed earlier, infirmaries did not benefit from endowments, rents or investment income. Wealthy Algerians did donate building materials, mattresses and beds to some infirmaries—and, in at least one instance, a wealthy Algerian landowner arranged and paid for construction of a salle de consultations (consulting room) for his workforce—but occasional gifts were hardly a large or reliable source of income.Footnote84

As for the fees that were supposed to be recovered from patients who could afford them, or from their guarantors, these revenues were scarce and difficult to collect. Mayors and administrators were regularly reminded of their duty to collect patient fees, in conformity with a circular dated 13 January 1908, but the number of patients who qualified for free treatment was extremely high. For instance, the infirmary in La Meskiana was not able to collect a single centime in four out of five years between 1915 and 1919 because all its patients were recognized as destitute.Footnote85 Some patients judged solvent on their admission to hospital were unable to pay after their release, either because they were still ill and unable to work or because they died from their illness. Discussion of unpaid patient fees in the Extrait du registre des délibérations de la commission municipale (‘Extracts of proceedings from the municipal commission’) for the commune mixte of Taher make for characteristically sad reading. In December 1915, commissioners learned that Salah ben Mohammed Zelloufi had ‘fallen into complete destitution and possesses no material assets’ since his illness and thus was unable to cover the relatively small amount of 14F95 (approximately three days’ wages) in fees.Footnote86 In August 1917, municipal commissioners authorized payment of 272F20 in infirmary fees from the communal budget, since several patients ‘had fallen into complete destitution or had died, and possessed no material assets’.Footnote87 In February 1919, the Receveur des Contributions Diverses, the civilian official responsible for tax collection in Taher, informed municipal commissioners that ‘despite every effort he had made’ it was impossible for him to recover 73F70 in fees from either the patient Zohra Frioui or her guarantor, since both individuals had fallen into poverty.Footnote88 Under these conditions, how was patient care to be funded?

Inevitably, the French government pushed responsibility for infirmary construction and operating costs onto ordinary Algerian taxpayers—who, it should be remembered, were already subsidizing public assistance used primarily by Europeans. Initially, these monies were raised centrally through the impôts arabes (Arab taxes). Beginning on 1 January 1903, an additional four centimes in each franc was collected from ‘populations of indigenous, mixed, or plein exercice municipalities subject to the payment of the Achour, Zekkat and Hockor taxes’ and an added 20 centimes in each franc was imposed on ‘Kabyle populations subject to the Lezma tax, regardless of the municipal regime to which they belong’ to support ‘assistance, charitable, and public utility works advantageous to the native population’.Footnote89 These land taxes, inherited from the Ottoman state and from the state established by amir ʿAbd al-Qadir, were levied exclusively on Algerian Muslims until 1919. A portion of the centimes additionnels collected was funnelled to support infirmary construction. The salaries of Algerian medical auxiliaries who worked in infirmaries were also funded from these taxes, and thus did not cost a penny to settler taxpayers.Footnote90 Some mayors and administrators also employed as much as one-fifth of the octroi de mer (consumption taxes on imports) to pay the costs of medical assistance for needy residents, where these funds were available.Footnote91

Recognizing that the centimes additionnels and octroi de mer were insufficient to meet growing welfare bills, Jonnart’s 1904 circular on ‘native’ medical assistance authorized mayors and administrators to collect an additional levy, the fêtes ‘Eurs’. The circular stipulated that gatherings held by Muslims should be levied with a flat-rate charge of 5F, rising to 10F for celebrations with music and/or the discharge of firearms. The sums collected were to be awarded to a Muslim welfare bureau, or, failing that a European welfare bureau, for distribution to Algerians in the locality. If, as was invariably the case, no welfare bureau existed,

[t]he proceeds of the abovementioned tax will be passed in their entirety to aid for poor natives, to the functioning of native infirmaries and the service of free medical consultations, to native or other works of charity concerning the native population in particular.Footnote92

As this section has shown, the mechanisms for paying for medical assistance and infirmaries were regressive, in the sense that they increased taxes on the (poorer) Algerian population through land taxes, consumption taxes and levies and lightened the burden on settlers who did not pay either the impôts arabes or fêtes ‘Eurs’. The final section of this article unravels the pre-colonial origins of fêtes ‘Eurs’ and traces how it was reconfigured by government officials and spent by local authorities.

Inventing fêtes ‘Eurs’ as an Islamic tradition

What the French called fêtes ‘Eurs’ was originally a feudal tax on marriage introduced to Algeria under Ottoman rule, the resm-i ʿarus orʿarus resmi (with the original meaning of bride/bridegroom tax). Resm-i ʿarus probably originated in the feudal kingdoms of northern Syria, was inherited by the later Mamluk and Turkmen regimes, and was then adopted by the Ottoman Empire, which spread the practice throughout Arab lands under its sovereign control.Footnote93 French officials recognized that fêtes ‘Eurs’ ‘goes back to a date long before our arrival in Algeria’ but did not understand or care that its origins were in Ottoman kanun (administrative law) rather than in shariʿa or ʿurfi (customary) law.Footnote94 Nor did they explain the original terms according to which these monies were collected and spent.Footnote95 The name adopted by officials—a tautological hybrid of the French word for ‘celebration’ or ‘party’ (fête) and the Ottoman Turkish and Arabic words for ‘wedding celebration’ (ʿurus, rendered phonetically in French as ‘eurs’)—is a clear indication that the Ottoman element was not well understood.

On 12 May 1888, fêtes ‘Eurs’ levies were formally assimilated to the French taxe sur les spectacles (entertainment tax) or droit des indigents (poor law) established by the loi du 7 primaire an V and the décret du 21 août 1806, so that they could be used to support state welfare objectives in Algeria.Footnote96 A sample of financial audits carried out on the accounts of Algeria’s communes mixtes in the 1890s indicates the determination of local authorities to avoid spending these monies to aid poor Algerians.Footnote97 For instance, in the commune mixte of Ténès in the Department of Oran, fêtes ‘Eurs’ was indeed collected. However, an auditor for the Cour des comptes identified a lack of transparency around how the tax was collected and spent, including that sums of money spent on the needy were far smaller than the amounts of fêtes ‘Eurs’ collected. Funds were also misspent in Saïda.Footnote98 These instances of non-compliance were flagged to officials at the Ministry of the Interior, who alerted the prefect of Oran. On this and other occasions, the prefect ordered mayors and administrators to spend sums raised from fêtes ‘Eurs’ in strict conformity with the 1806 decree: to assist the Algerian poor, and not to fund public works or other objectives.Footnote99

The assimilation of fêtes ‘Eurs’ to wider state poor law was a controversial decision in more ways than one. The droit des indigents applied only to ticketed entertainments such as theatrical performances and dances: as one well-informed official at the European welfare bureau in Algiers noted in 1911, ‘Free entertainment is exempt from all taxes.’Footnote100 In contrast, collection of fêtes ‘Eurs’ became mandatory for private occasions organized ‘in the douars [Algerian settlements] and tribes’ and, when municipalities decreed it, in café maures (so-called ‘Moorish’ cafés) and other public places where guests were invited to give money to a collection plate.Footnote101 Officials referred to this practice as ‘taoussa’, but did not define its scope. Nor did they appear to recognize that different forms of customary gift exchange operated across different regions of Algeria—or, indeed, within regions, towns and individual tribes—or that mutual aid and gift exchange were not equivalent to ticketed entertainment.Footnote102 This meant that private gatherings to mark births, circumcisions, engagements, marriages and funerals potentially fell afoul of the levy.

Governor General Jonnart issued a slew of circulars related to fêtes ‘Eurs’ in 1904. One circular dated 7 January 1904 called out the arbitrary and unlawful way in which some communes were collecting and spending these funds; another dated 6 June 1904 condemned municipalities for charging fees on Algerian social gatherings indiscriminately; yet another dated 21 June 1904 announced the levy’s imminent suppression. Following intense pressure from settler politicians but also from Arab delegates of the Délégations financières algériennes, Jonnart repealed the latter decision in yet another circular of 14 November 1904 ‘so as not to cause too much disruption’ in communal budgets, but only as stop-gap measure.Footnote103 The 5 December 1904 circular permanently reinstated fêtes ‘Eurs’ in relation to assistance médicale des indigènes (‘native’ medical assistance), including treatment and care delivered in infirmaries.

Accounting discrepancies and misuse of fêtes ‘Eurs’ continued apace. ‘In the commune of La Meskiana it [fêtes “Eurs”] should be spent on the operation of the native infirmary,’ wrote auditor Labeyric in a report he titled ‘tax judged illegal’.

In 1906 a sum of 450F only was devoted to [the infirmary] whereas this special tax brought in 835F and in the statement of revenues specially allocated to the infirmary in 1907 nothing derived from the tax on ‘Eurs’ which nevertheless raised 1400F.Footnote104

Labeyric reported the non-compliance in the accounts for La Meskiana, as well as those for Sédrata, both in the Department of Constantine, to the Minister of the Interior. The accounts for communes mixtes are complex documents and income is not easily matched with outgoings. Nevertheless, recurring incidents of non-compliance suggest very intentional decisions to avoid spending fêtes ‘Eurs’ in the manner stipulated in official circulars.

In 1921, after decades of auditors flagging accounting irregularities to the Ministry of the Interior, magistrates at the Cour des comptes again ruled the tax to be illegal.Footnote105 Algeria’s Director of ‘Native’ Affairs Jean Mirante demurred,

[i]n no way have those subject [to it] challenged the abovementioned tax which, far from having an illegal nature, finds on the contrary its origins in Muslim customs. Historically, the destitute have received succour in cash or in kind from the collection plate at feasts organized in the douars. But the use of these resources not being carried out with any oversight, the administration viewed it necessary to regulate their collection and distribution.Footnote106

Informal economic transactions were extremely vexing to French authorities because they constituted a basis for patron–client relationships in competition with the colonial state. By presenting fêtes ‘Eurs’ as a religiously inspired tradition, Mirante sidestepped the legal challenge from the Cour des comptes and secured continued use of the funds for localities.Footnote107

The symbolic power of invented traditions to legitimize elite domination in both national and imperial settings has long been a favourite subject for social historians.Footnote108 In the case of fêtes ‘Eurs’, we find hospital finance in Algeria to have been an unexpected site of inventiveness. Based on the assumption that fêtes ‘Eurs’ was an Islamic tradition and ‘strictly confessional’ it was collected from Algerian Muslims only, although at least one official zealously attempted to extend its collection among Algerian Jews, who as mentioned earlier were French citizens.Footnote109 So-called ‘Muslim customs’ and the supposedly ancient and traditional nature of the levy—which, as noted earlier, was an Ottoman invention and not religiously inspired—provided colonial officials with convenient cover for the fact that the tax was illegal under French law and easy to manipulate at the local level.

The performance of accountability by auditors at the Cour des comptes did not stop irregular transactions from taking place, as we see in serial documentation from the prefecture of Algiers dating from 1920 to 1927, when hospitals were experiencing a crisis of funding. A range of documents reveal ‘emergency’ use of fêtes ‘Eurs’ across the Department of Algiers as a matter of routine to pay for free consultations and the running costs of infirmaries, whether in full or in part.Footnote110 Sums were used for purposes stipulated in the 1904 circular as well as others that were not, such as hospitalization costs for settlers as well as Algerians, hardship funds, drugs, disinfectants, janitors’ wages, the purchase of furniture and surgical equipment, and doctors’ travel expenses: in short, expenses that were not exclusively incurred to benefit Algerians. These records also show that the prefect of Algiers was obliged to monitor communal accounts personally, to ensure that municipal commissioners were not abusing the fêtes ‘Eurs’, for example, by using these revenues to fund the transport of sick people away from their commune of residence to their commune of origin, thereby avoiding their own obligation and imparting the costs of medical care to another commune’s budget.Footnote111

What also becomes apparent from this documentation is that decisions on the use of fêtes ‘Eurs’ were voted on by municipal commissioners. It could be months, even years later, before these decisions were ratified by the prefect and audited by the Cour des comptes. The minutes of meetings held by municipal commissions very often reveal that Algerian landowners and notables formed a majority on commissions, and that they recommended use of fêtes ‘Eurs’ for medical purposes rather than for poor relief or other charitable works.Footnote112 Mayors and administrators may have influenced these decisions. Even in times of famine and epidemic disease, such as occurred between 1919 and 1923, local authorities refused to instate welfare relief for starving Algerians, in the form of distribution of grain supplies or chantiers de travail (public works projects) as recommended by senior officials in Algiers or Paris, on the grounds that state welfare would reward and encourage ‘idleness’, and destabilize the labour supply needed for colonial agriculture.Footnote113 Another possibility is that use of fêtes ‘Eurs’ was a convenient way for municipal commissioners, who comprised Algerian and settler elites, to reduce their tax liabilities for medical costs. Yet another possibility is that post-war inflation and economic instability increased the number of people reliant on state assistance rather than private healthcare, and so using taxes to improve local infirmary services became an active choice. Although further study of communal archives and matching audits at the Cour des comptes is needed to reach firmer conclusions, the available evidence suggests that behavioural responses to tax rules and funding structures at the local level contributed to the medicalization of welfare. The full extent of fêtes ‘Eurs’ collected, and the destination of all these funds, remains unknown.

Conclusions

In ‘Medicine and Colonialism’, Frantz Fanon drew an analytical distinction between the reluctance of rural Europeans to submit to hospital treatment and that of colonized populations. To Fanon, poor Europeans avoided hospitalization out of fear of the unknown or a desire to remain close to home and family. Colonized Algerians experienced fears of this nature, Fanon argued, but also resisted entering the ‘hospital of the whites […], the conquerors’ because this implied giving consent to colonial rule.Footnote114 But Algerians did seek medical attention and care in colonial hospitals, when this was accessible to them—as Fanon knew well, having treated many such patients himself. Rather than focus on motives and attitudes of patients, this article has brought to light some of the shared features of how hospitals were funded across Algeria and metropolitan France, as well as marked differences. In doing so, it has opened up the Algerian case for comparison with the politics of welfare provision in other imperial and post-imperial states, including the cases discussed in this special issue.Footnote115

In the wake of the invasion of Algiers, French authorities in Algeria appropriated, dismantled and ultimately outlawed Ottoman and Islamic infrastructures that effectively supported community welfare, namely Waqf al-Haramayn and habous. The French imperial state leaned on the Ottoman fiscal system to establish unequal rates of taxation for Algerians (the impôts arabes) compared with settlers who were French citizens. French welfare innovations in Algeria, including two Muslim welfare bureaus and hospitals established in the late nineteenth century, gave the appearance of colonial benevolence, but were resourced from unequal taxation and confiscated wealth. In the early twentieth century, officials applied elements of the loi du 15 juillet 1893 sur l’assistance médicale gratuite to Algeria, requiring the state to move to provide medical care for the destitute. From 1901, the government in Algiers proposed extending assistance to rural Algerians through construction of ‘native’ infirmaries—designed in what was considered as a ‘neo-Moorish’ style as part of a broader attempt to pay lip service to Muslim culture—but declined to fund their construction and maintenance. During the period from 1904 to 1926, segregated infirmaries were indeed constructed on Algerians’ behalf. Since localities simply would ‘not contribute under conditions sufficient for [infirmaries’] functioning’, it was ordinary Algerians who shouldered the financial burden—regardless of whether or not they sought treatment in infirmaries—through collection of centimes additionnels as part of the impôts arabes, taxes on consumption and the Ottoman levy known as fêtes ‘Eurs’, which was misrepresented as an Islamic tradition.Footnote116

The invented tradition underpinning infirmary operating costs came under scrutiny by centralizing institutions of the French state: departmental prefectures, the government in Algiers, and the Cour des comptes, whose Algerian records have been analysed in this article for the first time. However, colonial officials in the Bureau des Affaires indigènes et de la Police (Office of ‘Native’ Affairs and the Police, later called the Direction des Affaires indigènes et de la Police), delegates of the Délégations financières algériennes, and local administrators overruled legal objections to fêtes ‘Eurs’ by appealing to purported Islamic tradition.Footnote117 Local authorities continued to collect fêtes ‘Eurs’ from private gatherings such as weddings at the increased base rate of 30F and 60F with music/firearms from 7 January 1927, and 80F to 250F from 17 October 1946. Monies characterized as fêtes ‘Eurs’ were used for a variety of objectives up to the War of Independence, despite growing opposition from Algerian politicians who objected to the unfair and burdensome nature of the levy.Footnote118

Ultimately, legal and discursive strategies, accounting dexterities, and outright theft combined to transfer the costs of French colonial welfare onto economically marginalized Algerians. When the time came to publicize the expansion of state medical services, such as during celebrations held in 1930 to commemorate the centenary of the French invasion of Algeria, French officials suffered collective amnesia about these sources of funding.Footnote119 Many colonial-era hospital constructions remained in use decades after Independence in 1962 (some even to this day) presenting a façade of French colonial welfare provision, while their true origins lay hidden in accounting ledgers.

Archives

ADF = Centre des archives diplomatiques de La Courneuve, Paris, France

ANA = Centre des Archives Nationales d’Algérie, Birkhadem, Algeria

AWC = Service de conservation des archives de la Wilaya de Constantine, Constantine, Algeria

CAC = Archives nationales de France, Centre des archives contemporaines, Paris, France

CAOM = Centre des archives d’Outre-Mer, Aix-en-Provence, France

NARA = National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, USA

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Katja Guenther, Nathan Fonder, Christopher Markiewicz, Ahmed Ragab, Helen Tilley, Samiksha Sehrawat, Cyrus Schayegh, Keith Wailoo, fellow panellists at the 2014 Society for the Social History of Medicine conference in Oxford and fellow participants in the 2018 workshop ‘Healthcare before Welfare States’ in Prague, Czech Republic, who were encouraging interlocutors at different stages of this project’s genesis. I also wish to thank my colleagues in the Economic and Social History work-in-progress seminar at University of Glasgow, my co-editor Barry Doyle, Nathan Fonder, Andrea Talabér, Lewis Ryder, Madeline Woker and two anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier drafts and Sara Griffiths-Brown and Charlotte Mosedale for their copy-editing assistance; all flaws and interpretive choices are my own. This research was made possible by the assistance and encouragement I received in Algeria from the director of the Centre des Archives Nationales d’Algérie Abdelmadjid Chikhi, as well as Samia Benali, Zineb Chergui, Houriyya Rebba, Yasmina Ketir, Naouel Sai and Farid Zabat; Mr Boujemaʾa and Mina at the Bibliothèque Universitaire d’Alger; and Ahmed Arbi, Yasmine Arjoun, Amina Djebli Bilek, Leili Borsas and Mohamed Gharzouli at the Service de conservation des archives de la Wilaya de Constantine. In France, staff at the Centre des archives d’Outre-mer, particularly Dominique Duret and Daniel Hick, were always helpful and welcoming. I am also indebted to Louise Duroyon and colleagues at the Direction de la documentation, Cour des comptes, Paris, who patiently helped me identify relevant historical audits and arranged for their retrieval from the Fontainebleau site of the Archives Nationales, Paris. This work was further facilitated by the precious assistance of Ouanassa Siari Tengour and Claire Khelfaoui who liaised with archivists and photographed documents at the Service de conservation des archives de la Wilaya de Constantine, Constantine, Algeria, and the Cour des comptes, Paris, respectively when I was unable to travel in the autumn of 2018 due to disability.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hannah-Louise Clark

Hannah-Louise Clark is Lecturer in Global Economic and Social History at the University of Glasgow. She has published articles on the intersections between medical and racial categories in syphilis research; vaccination, epidemics and the colonial state; and cross-cultural translations of knowledge and law in North Africa, Algeria and Morocco specifically. She is lead author of a transdisciplinary teaching tool, Global History Hackathons Playbook (2019), and is currently finishing a book about race, religion and colonial medicine in Algeria.

Notes

1. The newspaper had an estimated print run of 5000 to 12,000 in the interwar period, but even non-readers encountered al-Najāḥ in public places such as cafés and markets. Asseraf, Electric News, 49.

2. Māmī, “Jawla fī al-mustashfa al-madanī.” All translations from Arabic and French are my own. For ease of reading, I have adopted simplified transliterations for Arabic in the main text and followed the International Journal of Middle East Studies system in the footnotes. I also use the Gallicized version of Algerian proper names where appropriate, e.g., ‘Mami’ in place of ‘Māmī,’ to assist the reader in finding them elsewhere in literature and archival documentation.

3. For an introduction to Fanon’s life and thought, see Gordon, What Fanon Said.

4. Johnson, The Battle for Algeria, especially chapter 3.

5. Quotations from Fanon, “Medicine and Colonialism,” 123–4.

6. Woker, “Empire of Inequality,” 211. See also Ageron, “Fiscalité française et les contribuables Musulmans” and Todd, “The impôts arabes,” for discussion of how French citizens were exempted from certain taxes, whereas Algerian Muslim subjects paid special ‘Arab’ taxes. Archival evidence from the interwar period indicates that a small number of Algerians sought French citizenship to avoid paying taxes and that inhabitants of some rural villages petitioned the governor general when they felt they were getting nothing for their taxes compared to their neighbours. See, for example, circular, Prefect of Algiers, February 27, 1926, and petition, villagers in Michelet to Governor General, February 25, 1926, Sous-préfectures d’Algérie/Sous-préfecture de Tizi Ouzou/Assistance, santé, émigration 1904–1954/Santé 904–1954/Fonctionnement du service médical de colonisation/915 48 (hereafter 915 48), CAOM.

7. These questions are directly modelled on Doyle,“Contrasting Accounting Practices,” 144.

8. To give one example, Keller points out it took six decades of wrangling over budgets before French authorities finally opened a psychiatric hospital at Blida in 1938, the hospital where Frantz Fanon would later work. Keller, Colonial Madness, 44–5. A great deal has been written on colonial medicine in Algeria since Fanon’s work. Ageron, Les Algériens musulmans et la France was one of the first historians to give an overview of public assistance for Muslims, including its financial component. Turin, Affrontements culturels dans l’Algérie colonial, considered medicine as an integral part of colonial ideology in Algeria, and showed that French medical propaganda was underfunded in relation to its grand goals. Still, their accounts did not systematically consider spending at the level of individual hospitals. It should be noted that, in parallel to historians’ efforts, Algerian policymakers, economists, doctors and public health experts set about responding to the economic and medical inequalities produced by colonialism but understanding the precise mechanisms of funding colonial healthcare was largely irrelevant to their endeavours. This was particularly the case once the nationalization of Algeria’s oil resources in 1971 generated new revenues for healthcare. See, for examples, Seminaire sur le développement d’un système national de santé; Belhocine and Belhocine, “Positions et pratiques des médecins dans le système de soins Algérien”; and Chachoua, “Le système national de santé: 1962 à nos jours.”

9. Historians of powerful developed countries, Britain especially, have found hospital finance and the negotiations among sufferers, payers and providers to be useful sites for examining the changing nature of states and societies. See Clark and Doyle, “Imperial and Post-Imperial Healthcare before Welfare States,” in this volume.

10. See, for example, Sehrawat, Colonial Medical Care in North India, and Johnson and Khalid, eds, Public Health in the British Empire, 10.

11. Soufi, “Les archives.”

12. Most Algerians lived in what were called communes mixtes (established 1868 onwards), vast administrative units settled with too few Europeans to be considered for ‘full’ municipal government, where they were subjected to a draconian system of rule under an appointed administrator. Algerians living in communes de plein exercice (established from 1843) that were comparable to regular communes in the metropole fell under government by elected mayors. For details see McDougall, A History of Algeria, 125–6.

13. Published colonial budgets are of limited use. As Jacques Bouveresse notes, ‘Le budget ordinaire, constitué par les recettes et les dépenses permanents de la colonie, ne s’exécute jamais dans les conditions où il a été vote.’ Bouveresse, Un parlement colonial?, 343.

14. Grangaud and Oualdi, “Tout est-il colonial dans le Maghreb?” 235.

15. Elsewhere, I demonstrate that the reception of bacteriological medicine in Algeria was shaped by cosmopolitan interpretations of Islamic law and long-standing religious cosmologies as much as it was by French and colonial law. Clark, “Of Jinn Theories and Germ Theories.”

16. This was the case for other states that succeeded the Ottoman Empire. See, for examples, Fischbach, State, Society, and Land in Jordan and Likhovski, Tax Law and Social Norms in Mandatory Palestine and Israel.

17. The process by which certain states have set the terms of ‘public’ health by ignoring or outlawing vernacular and alternative definitions of health is discussed in Tilley, “Medical Cultures,” 7–8.

18. Stoler, Imperial Debris, 2, 28. I would like to thank one of the anonymous reviewers for suggesting I engage with this work.

19. Nafti, “Masaʾlat ʿUlūm al-Ṭibb,” 24–5.

20. Bendaha, “Al-Niẓām al-Ṣiḥḥī.”

21. Ragab, “Making History.”

22. In practical and conceptual terms, waqf fall into two categories: waqf ‘whose immediate beneficiary was a charitable or public establishment (khayri endowments in modern terminology) and those whose immediate beneficiaries were private people […] (ahli endowments in modern terminology)’. Hoexter, Endowments, Rulers, and Community, 85.

23. This figure is given in Powers, “Orientalism, Colonialism, and Legal History,” 537. Regular collection and distribution of booty, a.k.a. ‘Victories due to God,’ is documented until the 1730s. Hoexter, Endowments, Rulers, and Community, 14–15. For information on waqf in relation to healthcare, see for example, Nafti, “Masaʾlat ʿUlūm al-Ṭibb.” See also references in Abid, La pratique médicale en Algérie; Buhajra, “Al-Ṭibb wa-l-Mujtamaʿ fī al-Jazāʾir,” 74; Mujahid, “Tarīkh al-Ṭibb fī al-Jazāʾir,” 197.

24. Hoexter, Endowments, Rulers, and Community, 85, quotation on 122. Studies of waqf in other cities in pre-colonial Algeria include Boughoufala, “Relations socio-économiques entre deux villes”; and Grangaud, La Ville imprenable.

25. David Powers writes how, following the French invasion of Algiers, General Bertrand Clauzel seized deeds of Waqf al-Haramayn together with the treasury and domains of the Ottoman regency. Subsequently, decrees and circulars issued by the Second Republic assimilated habous to state property (December 7, 1830), eliminated Islamic property law (the loi Warnier of July 26, 1873), and appropriated pre-colonial systems of mutual aid for official use. Agents of public ḥabūs were compelled to surrender their management to non-Muslim administrators appointed by the French state. Over time, French colonial officials led a campaign to discredit family waqf in the eyes of Algerian Muslims. Powers, “Orientalism, Colonialism, and Legal History.” Similar processes can be observed in British, Italian, Russian and Ottoman imperial contexts. For examples, see Ener, Managing Egypt’s Poor; Medici, “Waqfs of Cyrenaica and Italian Colonialism in Libya (1911–41)”; Oberauer, “Fantastic Charities”; Ross, “Muslim Charity under Russian Rule.”

26. This is discussed briefly in Ageron, Les Algériens musulmans et la France, 523–7. Mercier, La Question de l’assistance publique musulmane, documented the use of waqf to support the Muslim welfare bureau in Constantine.

27. Judgment, qadi in Blida, October 1, 1869, Affaires indigènes et territoires du Sud, 1830–1960/Questions sociales concernant les indigènes (1846/1944)/ALG GGA14H 2 (hereafter ALG GGA 14H 2), CAOM.

28. Act of ḥabūs of al-Hajj ʿAbd al-Raḥman Ibn ʿAli al-Qinʿai, dated June 22, 1886, ALG GGA 14H 2, CAOM. The endowment’s most important sources of income were rents from 27 private homes, shops and a public ḥammam (bathhouse) in Algiers and 38 hectares of agricultural land located in Birkhadem, Blida, El-Biar and Kouba, as well books, pearls and precious stones.

29. See Powers, “The Maliki Family Endowment.”

30. Blasselle, “Bureau de Bienfaisance Musulman de la Commune d’Alger. Exercice. Tableau de la Situation du Bureau de Bienfaisance Musulman de la Commune d’Alger pendant l’année 1873,” undated, ALG GGA 14 H 2, CAOM.

31. Letter, Prefect of Algiers, January 10, 1868, ALG GGA 14 H 2, CAOM. The prefect leaned on an imperial ordinance of April 2, 1817.

32. Letter, Hamida, Maliki Mufti of Algiers to Prefect of Algiers, June 18 [dated January in error] 1868, ALG GGA 14 H 2, CAOM.

33. Any change to the terms of the deed of gift invalidates a ḥabūs, so that the inheritance passes back to the rightful heirs. Following al-Qīnʿaī’s death, his sister ʿAīsha—who under the terms of the waqf received usufruct rights to one of al-Qīnʿaī’s properties as did her son and two daughters—sought support from the Hanafi qadi of Algiers to annul the waqf on the basis that her brother had not been in his right mind when he signed over his property. Her suit was unsuccessful.

34. Blasselle, “Bureau de Bienfaisance Musulman de la Commune d’Alger. Exercice. Tableau de la Situation du Bureau de Bienfaisance Musulman de la Commune d’Alger pendant l’année 1873,” undated, ALG GGA 14 H 2, CAOM.

35. Ageron, Les Algériens musulmans et la France, 1871–1919, vol. 1, 524. To compare this with the situation in France, Smith estimated 8 million French citizens in France lacked access to a bureau de bienfaisance (welfare bureau) prior to 1914. Smith, Creating the Welfare State in France, chapter 2.

36. The Délégations financières algériennes were a consultative body founded in 1898. In 1901 the Délégations were granted voting rights to determine the colonial budget, a right which became effective from 1902. These rights rested on a series of laws passed in 1900 which institutionalized the unwillingness of the French metropolitan state to face the costs of empire in Algeria and elsewhere. Woker, “Empire of Inequality.”

37. Ageron, Les Algériens musulmans et la France, vol. 1, 527.

38. Gouvernement Général de l’Algérie, Délégations financières algériennes. Colons. 1re Séance. Lundi March 7, 1904, 17.

39. Ibid., 19.

40. Programme, 1904, ANA TDS 0531; Soulié, “L’Assistance publique chez les Indigènes musulmans de l’Algérie,” 366; Soulié, L’Assistance publique chez les indigènes. Brochure de l’Exposition de 1900; Lejeune, La médecine de colonisation.

41. Délégations financières. Session de Mai 1902, 8.

42. “Réforme du regime de l’assistance hospitalière,” Délégations financières. Session de Mai 1902, 8–11 and “Assemblée plénière. 4e Séance. – Vendredi 6 Juin 1902 (Soir),” in Délégations financières, session de Mai 1902, 94.

43. The 1896 census recorded 318,100 French citizens (‘French origin, naturalized’), 48,700 Algerian Jews (‘Israelites’), 3,764,100 Algerians (‘Muslims, French subjects’) and 228,600 foreigners. Kateb, Européens, ‘indigènes’ et juifs en Algérie, 120.

44. This paralleled the situation in rural France. See Smith, Creating the Welfare State in France, chapter 2.

45. Figures from Soulié, “L’Assistance publique chez les indigènes musulmans de l’Algérie,” 6. On military medicine, see, for example, Fredj, “Les médecins de l’armée.” On missionary medicine, see, for example, Dirèche-Slimani, Les Chrétiens de Kabylie.

46. Sari, “La Transition de santé en Algérie,” 3.

47. Admission figures taken from Délégations financières. Session de Mai 1902, 9. Financial contribution for 1901 given in Gros, “L’Infirmerie indigène de Rébeval.” Under colonialism there could be no public assistance, strictly speaking, because there was no ‘public’ that deliberated common political concerns or shared a social vision. As Bouveresse explains, inbuilt distortions within the system of representation in the Délégations financières algériennes, which voted these sums of money, ensured that the agenda and interests of settlers always prevailed over those of Arab and Kabyle delegates. See Bouveresse, Un Parlement colonial? (2 volumes).

48. Letter, Prefect of Algiers to Sub-Prefect Tizi-Ouzou, “Assistance publique. Infirmeries indigènes. Création à Port Gueydon et à Rebeval,” December 23, 1902, 915 48, CAOM.

49. Letter, Prefect of Algiers to Sub-Prefect Tizi-Ouzou, “Infirmeries indigènes. Port Gueydon. Rebeval,” May 9, 1903, 915 48, CAOM.

50. Assistance médicale des indigènes. Circulaire du Gouverneur général aux Préfets (5 Décembre 1904), Commune Mixte de Ténès Q3 11, CAOM.

51. Draft letter, Charles Jonnart, February 2, 1905, ANA Territoires du Sud 0531. These factors are discussed in Clark, “Doctoring the Bled.” A small number of Algerian and settler doctors also called for expanded medical services for Algerians. One of these doctors, Dr Mohamed Nekkache, is described in Sari, A la recherche de notre histoire, 58–65.

52. Circular, “Assistance musulmane,” June 9, 1902, 915 48, CAOM; reprised in Assistance médicale des indigènes. Circulaire du Gouverneur général aux Préfets (5 Décembre 1904), Commune Mixte de Ténès Q3 11, CAOM.

53. Soulié, “L’Assistance publique chez les Indigènes musulmans de l’Algérie,” 386.

54. The figure is from Garden, Le Budget des hospices civils de Lyon, 98. The cost of food and wine combined could absorb between 50 and 70% of hospital budgets before the First World War. Smith, Creating the Welfare State in France, 64.

55. Clark, “Doctoring the Bled.”

56. Examples taken from “Œuvres intéressant les indigènes. Infirmeries – Consultations gratuites – Opthalmies,” April 11, 1901, ALG GGA 14 H 1, CAOM; “Note relative à l’Infirmerie indigène de Dra-el-Mizan,” April 10, 1918, 915 48, CAOM; “Extrait du registre des délibérations de la commission municipale,” May 29, 1916, Communes mixte d’Akbou, 60, AWC.

57. “Divers. Circulaire et Plans du Service Vicinal,” Commune Mixte de Ténès Q3 11, CAOM. On Jonnart’s architectural policy, see Béguin, Arabisances.

58. “AMIM – Rapport Prof. Soulié,” December 18, 1922, GGA Direction de la Santé Publique 079, ANA; “Rapport Prof. Soulié,” December 15, 1923, DZ/AN/17E/2031, ANA; Soulié, L’Assistance médicale des indigènes en Algérie (un siècle d’efforts).

59. As inspector of ‘native’ medical assistance, Soulié was familiar with conditions on the ground. Raynaud et al., Hygiène et pathologie nord-africaines, 521.

60. “Chasse émouvante,” L’Impartial, April 8, 1906, 2.

61. Opposition to smallpox vaccination on religious grounds is discussed in Turin, Affrontements culturels, for the nineteenth century and Clark, “Administering Vaccination,” 41–3 for the twentieth century. Although religious beliefs and behaviour did inform opposition to French medicine in some cases, there is also evidence of compatibility between metaphysical and materialist approaches to health, as documented in Clark, “Of Jinn Theories.”

62. Gros, L’Assistance medicale en Algérie, 30.

63. Clark, “Expressing Entitlement in Colonial Algeria” and “Of Jinn Theories.”

64. As Todd Sheperd and Malika Rahal remind us, the categories of ‘Muslim’ and ‘European’ ‘were in fact racial rather than properly religious,’ since Muslim converts to Christianity were unable to escape their legal status as 'Muslim subjects'. Shepard, The Invention of Decolonization, 24, footnote 14; and Rahal, “A Local Approach to the UDMA.”

65. Clark, “Expressing Entitlement in Colonial Algeria.”

66. Ibid.

67. Report, Henri Soulié, “Auxiliaires médicaux,” December 15, 1923, DZ/AN/17E/2031, ANA.

68. Doyle, “Healthcare before Welfare States,” quotation on 190.

69. Report, Consul Lewis W. Haskell, “Report No. 44. Cost of Living and Salaries at Algiers. Period 1900 to 1924,” May 21, 1925, 2–3, Records of the Department of State relating to internal affairs of France, 1910–29, Algeria, NARA [microform, consulted in Firestone Library, Princeton University]. The rising cost of food and medicines is mentioned in Exposé de la situation de l’Algérie en 1920 présenté par M. J.-B. Abel, 985.

70. Arrêt, Dupont, La Meskiana, July 3, 1922, 20070524/art 172, CAC.

71. Exposé de la situation de l’Algérie présenté par M. J.-B. Abel, Gouverneur général de l’Algérie. 1919, 583.

72. Exposé de la situation de l’Algérie en 1927, 18.

73. Délégations financières algériennes. Session ordinaire de mai-juin 1921, séance du 24 mai, 307.

74. As noted earlier, so-called ‘native’ hospitals had existed since 1876, but these were operated by religious societies.

75. Circular, Charles Jonnart, Assistance médicale des indigènes, December 5, 1904, 4.

76. For example, an audit of accounts for the commune mixte of Akbou showed that the prix de journée charged to Jacques Cartillino in 1905 varied between 2F25 and 3F15, whereas for Hamida and Bachir ben Ali Chila the following year the charge was 1F40. Arrêt provisoire, M. de Jouvencel, Ackbou [ou Akbou], October 19, 1908, 10–12, 20070337/art 89, CAC.

77. Clark, “Doctoring the Bled,” see chapter 3.

78. Soulié, “Congrès de Constantine,” 547. An additional circular was issued on March 18, 1927, see Bulletin sanitaire de l’Algérie no. 352, 59.

79. Letters, “Infirmerie indigene. Commission administrative,” December 11, 1926, Dra-el-Mizan; December 11, 1926, Haut-Sebaou; December 24, 1926, Boghni; January 7, 1927, Mizrana, 915 48, CAOM.