ABSTRACT

This article examines the impact of embodied actions in the daily practices of parliamentary debates in nineteenth-century France. The publication of parliamentary transcripts in the main newspapers at the time confirms the interest of the public in political debates. Instead of simply reporting the content of speeches delivered in the assemblies, these transcripts provided readers with highly detailed accounts of the deliberations, including, for example, the reactions of the audience, as well as the movements and vocal characteristics of political actors. Reproducing the articulations of speeches within the material context of the Chambre, journalists and stenographers sought to allow readers to immerse themselves into the parliamentary experience. Using the analytical frame of experience to examine these material elements within the recorded parliamentary activity found in a representative selection of newspapers, this paper argues that the discursive interactions within the assembly relied on practices that used the materiality of the Chambre. These practices shaped the cultural code of the assembly, which merged within its institutional fabric and exerted a strong influence on the debates. Given the volume of transcripts published during the long nineteenth century, the analysis focuses on a significant parliamentary crisis, the Manuel Affair, to serve as a contextual entry point into the topic.

Introduction

Sirs, in the sitting of February 26, you were very angry, we can agree on that. (On the right: No! No! we were indignant!). This anger led you to some very extraordinary actions. You filled this space (which is in front of the tribune); you assaulted the tribune; you jeered at your accused; you almost used physical force to wrest him off the tribune.

Louis de Saint-Aulaire, Chambre des Députés, 3 March 1823.Footnote1

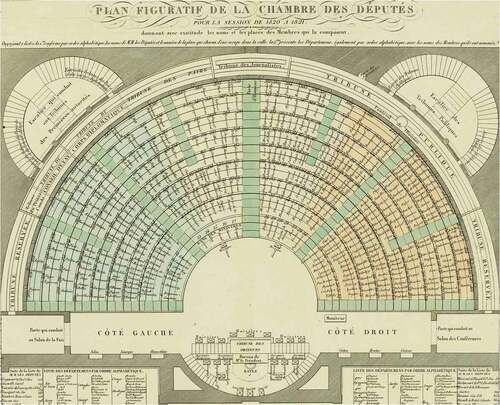

Figure 1. Plan figuratif de la Chambre des Députés pour la session de 1820–1821 (cropped). Madame E. Colin (ed.).

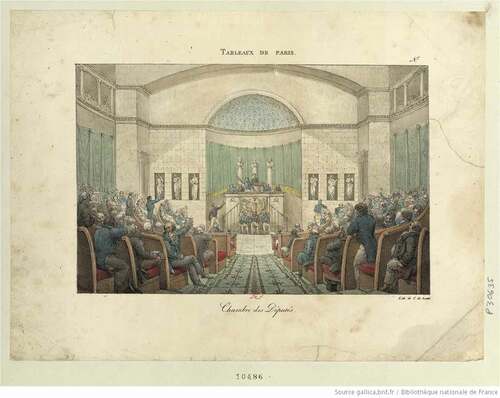

Figure 2. Chambre des Députés, décembre 1821. Charles-Philibert de Lasteyrie.

Considering parliamentary debates in the early nineteenth century usually conjures up images of focused parliamentarians, riveted on their benches, listening to orators in a solemn atmosphere. Until 1848, a restrictive tax-based election system even made it so that only the upper-aristocratic or professional economic elites could become députés (‘deputies’). Since these well-educated gentlemen, trained in the art of rhetoric, discussed the nation’s most important political matters, the general assumption is that speech was the essence of their orderly deliberations. The ‘extraordinary’ events recalled by Saint-Aulaire draw attention to the definition of ordinary parliamentary activity, to the physical component of the verbal exchanges and to the basis on which behaviours were judged to be acceptable. In other words, it leads to questions about how politics was practised within the culturally and institutionally framed assemblies. Using the context of the episode Saint-Aulaire described, which occurred during the debate on the Spanish Expedition in 1823, this article investigates the impact of embodied performances on the political debates of the French representative assemblies of the nineteenth century. Among other historians, Josephine Hoegaerts and Christopher Reid have already foregrounded the argument, for the British House of Commons, that how speeches were materially produced and delivered influenced their success. Political scientists, such as Shirin Rai and Alan Finlayson, have also discussed the significance of these aspects in oratory events and underlined that the performance of orations relies on the co-presence and interactions of the orator and the audience. Consequently, the following analysis focuses on the words but also on their production, reception and situation in the assembly.

Since past events can no longer be witnessed, this study proceeds from their reconstruction. Mirroring how past readers mentally experienced them in the printed press, it leans on the analysis of official and non-official transcriptions of debates published in a variety of French newspapers now available digitally from the French National Archives. Speeches occupied most of these transcriptions, but these newspaper columns also contained reactions from the audience, contextual and behavioural elements. It is within and between speeches where the indicators of performance in the shape of the dynamics between orators, the topic and the audience lie. Scattered or subtly noticeable in the daily routine, when they were not simply discarded from the reports,Footnote2 incidents reveal parliamentary mechanisms and norms, to paraphrase Jean-Philippe Heurtin.Footnote3 Thus, the Jacques Antoine Manuel affair, which interrupted and overlapped with the debate on the Spanish Expedition, is not the main interest of this paper, but a crisis that helps to scrutinize parliamentary practices. Spanning between February and March 1823, this affair serves as a contextual entry point into characteristic aspects of the Chambre as a space of performance and a politico-cultural domain. For this reason, in keeping with the significance of the elements discussed within their national and cultural setting, some French terms are preserved in this article.

The prism of performance offers the possibility of tying the scripted with the experienced assemblies together. It shows the political friction between the constructed roles of deputies with their personal incarnations. It allows us to pit the imagined or idealized Chambre against its material realities and the range of activities negotiated by parliamentary actors between the official regulations and the culturally established norms. In other words, it leads us to consider parliaments as a blend of ‘framed’ events from an institutional and national perspective, caught in the ‘scenario of everyday life’,Footnote4 especially at the professional level, and to focus on the product of these forces: practices. Therefore, the first section of this article presents the parliamentary stage and its actors. Including contextual explanations on the selected case, it describes the parliamentary spaces and highlights the role of journalists, thanks to whom we can experience past deliberations. A second section argues that practices emerged from a flexible understanding of assembly regulations and the sedimentation of activities resulting from an appropriation of the Chambre. These practices cemented the political process and ameliorated the structure of debate, but may have increased the fragility of the parliamentary order, as shown by the incident happening at the end of Chateaubriand’s speech. This fragility is illustrated in the third section, demonstrating the continuity of practices between incidents and crises as it explores the articulations and receptions of personal and group practices in the Chambre.

Setting up the parliamentary scene

When the debates regarding the Spanish Expedition opened on 22 February 1823, there was no doubt as to their outcome. The right, comprising the ultra-royalists, had an overwhelming majority of seats and advocated an urgent military intervention in Spain, which the constitutional and liberal left opposed. On 25 February, the discussions took a dramatic turn when the Minster for Foreign Affairs, François-René de Chateaubriand, an ultra-royalist peer in the Chambre des Pairs (‘Chamber of peers’ – the upper Chamber), delivered his first speech in the lower Chamber. Chateaubriand’s oration was a much-anticipated political and social event in which he passionately celebrated French patriotism and the monarchic order. To counter the Minister, on the following day, the left-wing liberal orator Manuel improvised an elaborated response against a war that would endanger the Spanish political balance. However, he could not finish his speech. Mentioning the risks incurred by King Ferdinand VII of Spain, Manuel would have said that the dangers for the monarch increased when ‘Revolutionary France felt it had to defend herself by using a new form, an energy never seen before...’.Footnote5 Interpreting this ‘new form’ as an intolerable justification of Louis XVI’s regicide during the French Revolutions,Footnote6 the right erupted. For them, such reasoning damaged the honour of all deputies, the Chambre and the monarchic order.Footnote7 The right pressured the assembly into examining Manuel’s exclusion, later voted on 3 March, a sanction that did not exist in the rules. On 4 March, Manuel, joined by fellow liberal deputies, defied the decision, entered the Palais-Bourbon and sat in the assembly, but was expelled by the armed police force. Consequently, on 5 March, the left boycotted the debates until the end of the session.

These events left a lasting mark on nineteenth-century French society and parliamentary history. The press covered the affair and its aftermath extensively. Nineteenth-century French historians broached the topic within developments on the Spanish expeditionFootnote8 and Manuel figured prominently in the Restoration era section of Timon’s successful Livre des orateurs (‘Book of Orators’).Footnote9 In current parliamentary or Restoration-focused studies, historians frequently allude to this crisis in relation to parliamentary sanctions.Footnote10 Beside Theo Jung’s use of the case to discuss boycott as a political strategy,Footnote11 the Manuel affair has recently benefitted from detailed attention. Thomas Bouchet has examined the scope of Manuel’s words and their insulting character as a justification of the revolutionary regicide.Footnote12 Jean-Claude Caron has discussed the construction of parliamentary order, in the antagonistic context of the Restoration, when deputies leant on radically diverging interpretations of France’s traumatic revolutionary past.Footnote13 What these two studies insist upon is the problematic cohabitation of conflictual perspectives on national identity in a shared political space, where modes of communication were underpinned by the common cultural frame of rhetoric. Their conclusions stress the impact of the words and discourse in the process that shaped the assembly as a political space.

Building upon these contributions, my aim is to further knowledge of political representation by bringing a more material perspective to rhetoric and parliamentary activity. This draws on Fabrice D’Almeida’s call to investigate ‘the concrete conditions in the practice of the verbal magister’Footnote14 as a need to balance the importance of discourse with a more physical perspective on parliamentary activity. On the one hand, nineteenth-century definitions of eloquence included not only the discursive and organizational elements of speech-making but also more material aspects: the power of the voice; the adequateness of comportment; or even the appropriate dress code. On the other hand, whilst speech analysis demands a consideration of the wider political environment, it equally requires an assessment of the articulation of speeches within the immediate context of the assembly. Indeed, the reception of speeches depended on their conditions of production, how and where they were delivered and the dispositions of the audience. Thus, the public side of political representation encompassed the roles played by orators, the audience of deputies on the benches, the public audience in the galleries and those of the assembly President (comparable to the Speaker) and administrative personnel, in the shared space of the assembly.

Studying parliaments from a performance perspective allows the inspection of individuals’ embodied practices against the backdrop of a cultural, institutional and material script. Consisting of formal and informal elements, this script encloses the entirety of constraints on the actions to be performed, of which conformity and success are evaluated by multiple audiences. Since Peter Burke identified a ‘performative turn’ in history inspired from theatre studies,Footnote15 the concept was adjusted to the parliamentary context. Reasserting the materiality of performance, Shirin Rai has proposed a ‘political performance framework’,Footnote16 which articulates four axes: performance relies on embodied presence; bodies perform in space co-constituted by the performance; spoken messages can be considered as speech acts not only for their rhetorical qualities but also for their sonic and vocal characteristics; and performance is a product that requires efforts and practice. Studying the late eighteenth-century House of Commons, Christopher Reid has demonstrated that speeches were performed within a highly normed cultural and architectural apparatus. He notes that the assembly room supported and constrained delivery, shaping the form and content of the debates and that oratory culture articulated around rhetorical skills, calculated gestures and emotional display.Footnote17 Delving into the embodied and vocal characters of oratory, Josephine Hoegaerts has shown that MPs in the nineteenth century were also keenly aware of their performances and skills. By her account, orators strived to control their vocal productions to suit the audience’s tastes and improve the impact of their speeches.Footnote18

Whilst orators were the main attraction, their role only existed in the presence of the audience, who evaluated their actions during the events. In Alan Finlayson’s view, performance is an occasion in which the topic, the speaker and the audience are interconnected.Footnote19 Nonetheless, understanding their relationships requires situating them in space,Footnote20 or in the case of the French Chambre, within their shared and respective spaces. Indeed, with regard to the French assembly, Delphine Gardey has explained that ‘the debating room forms a fragmented and highly regulated combination in terms of space but also in terms of presence and circulation of bodies’.Footnote21 These restrictions of circulation between clearly defined functional spaces co-create the political and institutional dimensions of the assembly, as they provide a sanctuary to the deliberation area.Footnote22 Thus, the public audience, considered as ‘strangers’ to the Chambre,Footnote23 sit in galleries that form an arc at the periphery of the hémicycle, the semi-circular concentric rows of the deputies’ benches (see for a more visual description of the assembly). These galleries had pre-defined sections so the different social groups would remain separated. The public audience could witness the discussions but could not join the debating zone. Forced to stay silent, they were under the watchful supervision of huissiers (‘ushers’) who could expel anyone disrespecting the rules.Footnote24 For Jean-Philippe Heurtin, the divisions of the debating space organize parliamentary activity in a grammar synonymous with ‘regularity, normality, harmony, in other words, order’.Footnote25 The core of this grammar is the ‘figuration of the people by the orator, the focalisation of space on the speech area’ and the ‘analytical distance between the orator and the audience’.Footnote26 The distance between the orator and the other deputies is generated by the corridor and inner half-moon space that separate the hemicycle from the tribune, the rostrum from where orators delivered speeches. Located under the President’s desk, the tribune is additionally protected by the institutional authority.

As Hervé Fayat has emphasized in his study on parliamentary discipline, individuals must internalize and maintain the hierarchic spatial structures to preserve parliamentary order.Footnote27 These structures were, for instance, highlighted by the uniforms worn by the ‘members of the Chambre’,Footnote28 such as the silver-embroidered blue vest that identified the deputies during all public sittings.Footnote29 As proof that some practices were temporary, journalists, probably wearing bourgeois clothes, also shared the floor and corridors until 1820, although it contradicted rule 90 that banned ‘strangers’ from this area.Footnote30 In March of that year, an incident between a deputy and journalists resulted in a formal complaint addressed to the President to uphold rule 90. Somehow comparable to the eighteenth-century clearing of the theatre house parterres of their rowdy audiences,Footnote31 this abolished the tolerated presence of journalists on the floor.Footnote32 From then onwards, unless a throng of people violently invaded the Chambre, only the professional group of the President, huissiers, deputies and the journalists of Le Moniteur Universel could enter the debating zone.

The selection of material used to conduct the analysis retains a close proximity to the nature of the debates as events and preserves the roles individuals assumed. Drama specialists and historians alike underline the necessary process of reconstruction that is due to the transient nature of events.Footnote33 Instead of relying on multiple sources, including illustrations, historical accounts or collections of speeches, this study relies on transcripts published the day after the debates, and especially on the Parisian press that circulated nationally. The reasons are that daily Parisian publications could neither be amended nor corrected; therefore, they chronicled a series of bracketed events that mirrored the ritual structure of the debates. By contrast, the less frequent or local press favoured summaries, lagged actual events and proposed several sittings in the same issue.Footnote34 Contributing to the publicity of debates, transcripts recreated the articulation between the people and the parliamentary events.Footnote35 The specialized journalists in charge of the transcription acted as ‘modest witnesses’Footnote36 recording the debates for a secondary audience that was absent from the Chambre. Fidelity and accuracy in the recording process meant not only preserving the content of speeches, but also their context: the orality of orations, the reactions of the audience that measured orators’ success and the scenography. Given the number of details in the Chambre that could be reported, each journalist and editor had to measure the relevance of these more behavioural details in comparison to the textual content of speeches.Footnote37 Therefore most of these details remain lost to historians, especially if they were considered normal. Still, the presence of such contextual and material realities denotes a real interest for readers, who could mentally reconstitute the parliamentary experience.Footnote38

The recording process was neither infallible nor neutral. The controversies over whether Manuel discussed a new ‘force’ or ‘form’ of resistance attest to the political dimension of the transcripts and the material condition of oratory production. Journalists interpreted and reported the same events in distinct political tones and the political distribution of the press was unbalanced. Although the publication of opinions considered unsupportive of the monarchy was unthinkable, some newspapers seemed sometimes more royalist than the King (La Quotidienne, Le Drapeau Blanc, La Gazette de France). At the other end of the spectrum, others favoured a more liberal interpretation of the Royal Charter (Le Constitutionnel). Between these newspapers stood the moderate ones (Le Journal du Commerce, Le Journal des Débats Politiques et Littéraires).Footnote39 Besides, journalists’ working conditions affected transcriptions. Before the national transcription service settled in the assembly in 1848, and before Le Moniteur Universel became Le Journal Officiel, journalists of Le Moniteur Universel were contracted by the Chambre. Redacting the only institutionally sanctioned transcriptions, these journalists were the only ones granted a desk close to the tribune. Benefiting from this proximity and easier access to orators’ manuscripts, they produced the longest transcripts that focused on speech content. Situated in the central section of the galleries, journalists of the other newspapers could not have been physically further from the tribune. Such distance diminished their ability to hear the debates, particularly when the Chambre was agitated, but they compensated for this drawback with a wider perspective of the assembly and greater editorial freedom. Finally, the selection of newspapers may give the impression that the royalist perspective is given more weight. After consulting the other newspapers available, such as Le Courrier Français (left-wing) and Le Journal de Paris (centre-left), they seemed qualitatively similar to the ones already referred to, which made their addition redundant.

Defining spaces: interacting with the audiences

Performing the role of a deputy meant acting within the frames of parliamentary rules and its cultural norms, even though this could generate conflicts in practice. As Hervé Fayat has mentioned, the explicit rules and disciplinary measures of the Chambre were the most visible constraints on deputies’ behaviour.Footnote40 Indeed, the rules not only described an order, in the meaning of a predictable sequence of events,Footnote41 but they also shaped the deputies’ repertoire of performances. In this regard, on 20 February 1823, the sitting began in an orderly fashion. President Auguste Ravez opened the debates. A deputy read the previous day’s proceedings and some administrative matters were resolved. Ravez then called Jean-Baptiste Gaye de Martignac to the tribune, where speeches were delivered according to rule 20.Footnote42 As the reporter for the commission on the Expedition of Spain, Martignac logically had the first speech-turn. Other orators had to add their names to a list to join the discussions and were called by the President, who combined the enrolment order with the pro and contra structure of the deliberation.Footnote43 The moment Martignac implied that no French person would hesitate to intervene in Spain, General Maximilien Sébastien Foy, a liberal, voiced a loud contradictory ‘Ah!’ from his seat and ‘agitation beg[an] on the left’.Footnote44 Other reactions echoed throughout Martignac’s speech,Footnote45 even though rules 23 and 26 forbade interruptions, marks of disapproval or support.Footnote46 When Martignac could not be heard over the tumult the President intervened vocally or rang his bell to restore order.Footnote47 Such customary tolerance with reactions issued from the benches, instead of disciplining the interrupters instantly, demonstrated that the rules organizing the discussion were not rigidly enforced. Adapted to the circumstances of the debates, the implementation of the regulations was left to the self-regulatory power of the assembly and the interpretation of the President.

This facilitated the emergence of tacit knowledge, added to the parliamentary script. The primacy of speech still belonged to the orators but the interactive role of deputies in the audience expanded. Sporadic reactions from the benches commonly voiced discontent, support or engaged precisely with orations. For instance, during Chateaubriand’s speech, the liberal Louis-Stanislas de Girardin interrupted the Minister for calling the Spanish insurrectionary forces ‘levellers’. Considering the objection, Chateaubriand substituted the term for ‘revolutionaries’.Footnote48 Later, the left stopped the Minister again and questioned his ethos:

M. Girardin and others: You have served the one you call the usurper as well.

[…]

On the right. – Silence! Order.

M. President: I wish the side of the assembly, who can be heard muttering, remembered that order remained undisturbed yesterday during their orators’ speeches. They should reciprocate.

M. Chauvelin: These are merely reflections.

M. President: It is those exact reflections, from which one should abstain, that disturb order.

M. Foy: The minister for foreign affairs did as many others did; he served Napoleon; he was his plenipotentiary minister in le Valais.

M. de Chateaubriand: Yes, sirs, I fulfilled diplomatic functions under Napoleon: but at that time, the Duke of Enghien had not been assassinated.Footnote49

While still excluding the public audience with whom only the huissiers were supposed to engage, such interactions between the sitting deputies and the orator seem to mirror the dynamics between the audience and the actors in the eighteenth-century theatre houses.Footnote50 Like theatrical representations, orations were dialogic co-constructions different from the scripts that speakers had prepared. However, deputies and orators had a very similar professional status in the Chambre and their words as individual political actors had the same weight. In practice, these tolerated exchanges between the tribune and the benches transformed the debating space into a shared space where the orator exerted his rhetorical authority.

Reactions in the previous examples illustrated the heterogeneous nature of the audiences and the identities they performed within the Chambre. In the early days of the Restoration, the ultra-royalist ended the rotation of seats after elections, which marked a new step in the spatial appropriation of the assembly that began in the First Revolution.Footnote51 In the hemicycle, stark royalists sat on the right, moderates took the centre-right and centre-left and liberals had the left. Not supported by any assembly regulations, these sides were restricted to deputies sharing political affinities. Density in each division represented political strength and sitting in one section was a performance through which deputies asserted their political opinions. ‘Loud cheering on the right’ and ‘bursts of laughter on the left’Footnote52 during Chateaubriand’s speech not only described the types and intensity of reactions, but also reproduced this spatial division to translate the opinions of deputies in these entities metonymically. Sitting behind but higher than the tribune, the President protected the integrity of the debates. While monitoring the orator and the benches, he also exerted his authority by proxy in the entire Chambre thanks to the huissiers and guards. According to the rule, no one could speak without his consent. In practice, he could only react and, staking his own institutional and rhetorical authority, interrupt any speech and remark. This he did vocally or extra-linguistically with his bell, a relic from the Revolution,Footnote53 absent from the written rules after that period. Whenever this proved ineffective, he could perform rule 25, symbolically donning his hat, to indicate the debate would stop if chaos persisted. Deputies performed both a political and an institutional part in the debating area and the audience, divided along political lines and status, to whom they spoke did not listen or react with the same analytical grid, possibilities or authority.

While rules and entrenched practices governed the hemicycle and the tribune, other spaces such as the floor and the corridors remained undefined, porous to new performances and practices. Within the debating area, the floor and its corridors corresponded to the central semi-circular zone of the Chambre and the two straight passageways separating the tribune from the benches. Materializing the required distance between the orator and the audience, the floor and the corridors also functioned as transition spaces, trodden when deputies entered the Chambre from the assembly salons, or when they switched roles between orator or audience member. As Minister for Foreign Affairs Chateaubriand was returning to the ministerial bench after his speech on 25 February, a crowd of right-wing deputies surrounded him in the centre of the Chambre. Standing on the floor, they enthusiastically congratulated the Minister, embracing him, shaking his hand and patting him on the back.Footnote54 After remarkable speeches, orators often received such demonstrative praise from their colleagues on their political benches. Since Ministers sat in the inner front row, a demonstration of support required right-wing deputies to move from their benches to the floor. Considering the list of names cited in the newspapers,Footnote55 showing support for the Minister and being witnessed in friendly interactions with him was a calculated move from the right-wing deputies. Instead of simply cheering the Minister from their benches, what they initially performed was an amplified and ostentatious reaction to a Minister’s speech advocating shared values and arguments that borrowed the floor of the Chambre.

Still, many deputies lingered in the centre and the laudatory performance grew into a show of strength when Guillaume-Xavier Labbey de Pompières, a liberal, was called to the tribune: ‘M President: It is now M. Labbey de Pompière’s turn to speak. (much laughter on the right).’Footnote56 On behalf of the institution, the President implied that the right exceeded the tolerance limit for the practice of their support, categorizing their performance from then onward as a disturbance. His performative announcement returned the floor to its function of a necessary empty space and signified to the right that they now encroached on what Hervé Fayat calls ‘the ideal space situated around the tribune’.Footnote57 Nevertheless, the right refused to comply with the order for another 10 minutes,Footnote58 during which Labbey de Pompières stood at the tribune. To counter their resistance and the disdain the right had expressed with their laughter, some liberals gathered at the foot of the tribune, requesting from Labbey de Pompières that he swap turns with an orator ‘more favoured by the Chambre’.Footnote59 Against the growing agitation, the President played his institutional role. He demanded silence, rang his bell and again ordered deputies back to their seats, but his efforts were considered ‘vain’Footnote60 and ‘useless’.Footnote61 The noise produced by the right, still standing on the floor, drowned out the voice of the orator who had attempted to be heard several times. Strategically, Labbey de Pompières pushed his manuscript on the side of the tribune to signal an improvisation, in hopes this would attract some interest,Footnote62 since most speeches were read. However, Jean-Guillaume Hyde de Neuville, challenging the President who had just told him to stay quiet, interrupted the orator twice to erode his credibility.Footnote63 In their conversations, interruptions and appropriation of central space of the assembly, the right filled the Chambre with their corporeal and sonic presence. Doing so, they disrupted the political process by forming an obstacle between the audience on one side and the orator and President on the other. Only their departure, after a while, restored quiet, but the orator was nevertheless ignored.Footnote64 Thus, the interactions between the audiences and the orators in the assembly spaces indicate that parliamentary activity was framed by practices resulting from a flexible understanding of the rules or emerging from their absence. While this improved the fluidity of the exchanges, it endangered order, especially when the assembly became more emotional and less receptive. In such times, there was a greater stress on personal authority from speakers, whether authority originated from their role, personality or both.

Continuity into the crisis and personal articulation of performances

The crisis merely amplified the intensity of actions and acted as a magnifying glass allowing us to witness the usually more discrete elements in a concatenated aspect. While the consequences of the Manuel affair were exceptional, the unfolding of its crisis highlights the role of embodied actions and their inclusion on the repertoire of parliamentary activity. Alone at the tribune, facing the deputies and the galleries, orators fulfilled a more public role when delivering speeches. Contextualizing their orations in the deliberation, they referred to previous orations, while their unfolding performance articulated with constructions of their own past appearances. On 26 March 1823, as Manuel exchanged speech-turn with a fellow liberal deputy, ‘a crowd of deputies from the right […] hurried back to their seats’.Footnote65 The left-wing orator was welcomed by a ‘worried’ and ‘disapproving atmosphere’ in an assembly filled with ‘a lot of noise’.Footnote66 Sources reported that issues simultaneously occurred in the galleries, which forced the President to send the huissiers twice to restore order in the public audience.Footnote67 After a probably ironic tribute to Chateaubriand’s rhetorical skills at presenting ‘everything that can be said in favour of the war’,Footnote68 Manuel frequently antagonized the Minister, even reducing the debates to their exchange: ‘Manuel: […] according to the speech that you heard yesterday and to which I wish I had answered right away […].’Footnote69 Immediately responding to Manuel’s barbs, the right calibrated their interruptive comments to the orator’s argument and targeted the orator himself. When Manuel implied that Chateaubriand had little knowledge of diplomacy for a Minister for Foreign Affairs, a voice on the right wondered aloud: ‘Should he take lessons from the man of repugnance?’Footnote70 These numerous references to Manuel’s ‘repugnance’ pertained to a speech delivered in 1822, in which Manuel stated that some ‘people had perceived [the returning Bourbon] family with repugnance’. The right, back then, had ordered that Manuel be punished for such terms but Ravez, already President at that time, had not yielded. Thereafter, the word ‘repugnance’ referred to that occasion and constructed Manuel as a constant insult to the ultra-royalist identity. While the audience constantly revaluated orators, some events attached defining characteristics to how deputies were perceived.

As the day before when celebrating Chateaubriand’s oration, the performance of the right in response to Manuel’s speech stemmed from an emotional reaction to an oratory event. Manuel’s oratory failure lay in his ‘[in]ability to read the audience and to re-calibrate [his] performance as it unfold[ed] in response to reception indicators of/from the audience’.Footnote71 The content of his improvised speech did not infringe regulations or the strict parliamentary norms but offended the overall rhetorical values governing what the audience could tolerate. Already reproached for his attack on the King of Spain and his government earlier in his oration, Manuel omitted any rhetorical precaution preventing the misinterpretation of the ‘new form of resistance’ as a justification of Louis XVI’s death. In Jean-Claude Caron’s words, ‘no one [took] the risk to mention the martyr king’s figure, using another register than lamentation’.Footnote72 Some deputies ‘rejected such language’ as they said laterFootnote73 but they remained seated and demanded that Manuel finished his sentence.Footnote74 Only the right interpreted Manuel’s words as ‘strictly speaking, intolerable […] as if they induced physical pain’ leading to ‘this almost furious desire to silence the speaker’, as Thomas Bouchet has explained.Footnote75 ‘Tumultuous cries coming from the right side interrupted the orator’Footnote76 and ‘a crowd of voices’ repeatedly shouted ‘order!’, ‘remove him from the tribune!’ or ‘cancel his speech-turn!’Footnote77 Meanwhile, ‘as a crowd’, the right ‘gather[ed] at the foot of the tribune and in the corridor’ situated on the rightFootnote78 and, being ‘moved by an emotion that is easy to understand, they [left] a large space between them and the left’.Footnote79 The intensity of the chaos was such that transcripts could hardly render it. The Moniteur universel, for example, mentioned that ‘the uproar [was] at its height’, soon followed by ‘the noise redouble[d]’.Footnote80 Other transcripts presented the pervasive noise in more spatial terms, as ‘resonating up to the cupola’,Footnote81 reaching outside of the assembly,Footnote82 or as a storm that had not raged for a long time.Footnote83

In denouncing Manuel’s ‘horrible speech’,Footnote84 the right also opposed parliamentary order, objecting to the ‘call to order’ issued by the President, which they deemed lenient. They ‘brought the stage into being by occupying it, speaking from it […]’,Footnote85 to borrow from Shirin Rai, and turned it into a space for their contention. Firstly, their protest began when, shouting, they emptied their benches and stretched to the floor facing the tribune with some deputies even directly ‘speak[ing] heatedly with the President’.Footnote86 In the process, they erased the symbolic liminal space between the tribune and the hemicycle and reduced the debates to their interactions with the President and the orator. Secondly, they countered the application of rule 21 announced by Ravez, which allowed the orator to clarify his words after a ‘personal call to order’.Footnote87 Thirdly, although some suggested that they should leave the room,Footnote88 they remained on the floor and demanded that the President obey them and remove the orator from the tribune. Ravez attempted to reassert his authority and argued all deputies should respect the rules, to which the right responded that ‘[they] were stronger than the rules’ and that they would not listen to the orator.Footnote89 Seeing themselves as the embodied will of the assembly, they reclaimed full institutional powers: ‘The same voices on the right. The Chambre is stronger than the rules.’Footnote90 Made inaudible by the right as well, Ravez donned his hat, stood up and read rule 25, which stated that if the tumult was too strong and the President was unable to restore order, he would pause the debates for an hour. This institutional performative utterance released the pressure from the tribune and the right left the public space of the Chambre.Footnote91 Neither the orator nor the President had been bodily silenced, but by physically and sonically invading the floor, the right had seized the Chambre.

So far, transcripts complemented each other and allowed for a mainly straightforward reconstruction of the events with only minor variations of content, intensity or chronology. Newspapers always took a position politically in their reports and comments from right-wing deputies, written in full in royalist columns, were often shortened as ‘interruptions from the right’ in liberal transcripts and vice-versa. However, this crisis produced some irreconcilable alternative descriptions that also differ from the neutralized reports in the Moniteur universel, in which individuals’ implications mattered less. While Manuel kept silent at the tribune, two right-wing deputies, including Hyde de Neuville, defied the President and spoke to the assembly.Footnote92 Their examples show how behaviours and vocal performance were interpreted and rendered in distinct political tones. In versions favourable to the right, Hyde de Neuville rushed to the tribune and looked contemptuously at an impressed and confused Manuel. The power of the right-wing deputy’s voice dominated the noise of the assembly and quieted the left at once.Footnote93 Manuel was then portrayed with his arms folded, scornfully eyeing the right or reading a newspaper.Footnote94 In contrast to that, the rest of the press underscored Manuel’s tranquillity. Standing firmly behind the tribune, Manuel remained composed and smiled at the ultra-royalist deputy’s ‘emotional gesticulations’.Footnote95 Attempting to be heard, Hyde de Neuville seemed ‘pale’ and ‘convulsive’.Footnote96 Although such polarized versions were rare, details on the embodied performances served to nuance the reach and effect of speeches, without overly altering the structure of the events or the content of the debates.

Finally, considering the uniforms as visible political attributes of parliamentary functionsFootnote97 leads to a rethink of the role and presence of other items in the Chambre. Spaces defined the repertoire of roles available to deputies, but for each space certain items corresponded with their related practices. Whilst Manuel’s reading of his newspaper at the tribune seemed disrespectful, it was because this solitary activity ironically expressed resilience against the right. Orators commonly carried newspapers to quote speeches accurately,Footnote98 and also typically read manuscripts at the tribune, as opposed to their British counterparts, although remarks on their heftiness signalled boredom and inefficiency, as with Labbey de Pompières’ ‘long written speech’.Footnote99 Other objects forced users into a conventional and meaningful posture. For instance, transcripts often began with the President ritually taking his seat in his armchair, which marked the opening of the debates. Standing up to sanction Manuel over the right’s outraged cries, to allow the liberal orator to justify his words, or to read article 25,Footnote100 the President’s change of posture served to reassert his authority. On 26 March, after the pause, the President rang his bell to signal the discussions resumed, then shook it later to quiet the assembly.Footnote101 The moment Manuel walked to the tribune to finish his speech, the right exploded once more. Transcripts portrayed the President ‘ring[ing] the bell to no avail’,Footnote102 as he had done several times throughout this sitting, but he was unable to restore order. However differently it may have rung in these examples, as a symbolic attribute of authority, the bell signalled that a threshold into disorder had been reached in the temple of political eloquence.

Conclusion

The crisis altered the environment of the assembly and required deputies to adjust their performances. Each time Manuel appeared at the tribune after his unfortunate words, the right prevented him from speaking. Framing him as ‘the accused’,Footnote103 they silenced Manuel as a deputy until his exclusion. Usual debates resumed on 5 March, after the left declared a boycott, but the mood of the assembly had considerably changed. When Martignac closed the debates, he seemed ‘too heated and emotionally involved’ for a speech addressed ‘to the seats’,Footnote104 which shows he expected a more engaged and less empty room. The left faced the dilemma of its own silent performance, torn between fulfilling an elected function and acting upon personal convictions. Some left-wing deputies occasionally joined the public audience or the gallery section ‘reserved for former deputies’,Footnote105 while a few others sat in the hemicycle without their official attire,Footnote106 demonstrating their unwillingness to join the deliberation. Exemplifying the interaction with the symbolic materiality of the assembly, the benches the liberals had emptied were soon filled by the right. The laughter this occasioned during the votesFootnote107 and the ‘pleasure’ right-wing transcripts echoed at the situation,Footnote108 underline that this was not simply motivated by an acoustic issue or ‘a lack of space on the right benches’.Footnote109 Sitting there meant emphasizing their victory over Manuel and the left. In other words, performances were always tied to the context of the assembly and the translation of actions into a meaningful performance relied on the perception of the audience.

To conclude, performance helps to historicize parliaments as social, cultural and political domains, transcending their representations as decision-making institutions, and allows a grasp of the daily realities and practices of the parliamentary experience. This experience relied on the materiality of the Chambre, the social interactions of the political actors and the constantly evolving institutional and cultural frame of the Chambre. Deliberations were not a succession of convincing orations, but a physically interactive discussion involving previous and incoming orators at the tribune entwined in dialogic negotiations with an audience. Speeches always caused reactions and orators who asserted their authority against the interruptions and negative comments usually increased the value of their speeches and their rhetorical status within the Chambre. Whether their choices were always conscious or not, deputies harnessed the full physical potential of the assembly and performed what they regarded as the most suitable embodied actions. Repeated performances contributed to the sedimentation of practices and tuned the assembly into a singular debating space. From the President’s desk to the galleries, everything could be imbued with political essence if it were used during the daily rhetorical confrontations. Because each role was anchored in a specific environment, deputies did not have the same means available nor were the same gestures accepted in each defined space. The collective community of deputies past and present negotiated with this tacit knowledge of what was considered as efficient, ridicule, aggressive and so forth in comparison with what the representative craft should entail. Practices often superseded the rules and almost nullified some of its articles, forcing the President to defend his institutional authority against individuals, groups and the cultural majority of the Chambre.

Commenting on the incident in 1823, the press underlined that the President had only used article 25 three times over the last 12 years of the Restoration. In comparison, on 14 March 1872, after deputies had invaded the tribune two days prior, Le Petit Journal mentioned that the President had already donned his hat three times to suspend the sitting over the last six months.Footnote110 Since the Restoration, new rules had attempted to enforce more disciplinary measures to protect the debates. The political culture had evolved and the assemblies had gathered in many different architectural spaces. Nevertheless, none of these modifications erased the practice of invading the floor, which began much before the Manuel affair and remained in the parliamentary repertoire in the Third Republic or after. Thus, tracking practices in the longer term allows us to deconstruct some events as epiphenomena secluded within their particular contexts and regimes, as much as shedding light on the routine-like and benign elements of parliamentary activity. Methodologically, focusing on practices invites us to bridge the gaps between the many political regimes and to inspect parliamentary activity from the Revolution until now, although the quality, degree of subjectivity and nature of the sources available differ greatly. Moreover, as it reveals the continuities and breaks of parliamentary activity, it tells the story of the national and cultural traditions of the parliamentary craft and sheds light on the embodied memory of its actors.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to all the participants in the ‘Oratory and Representation’ workshop (March 2020) for their fascinating papers and the discussions we had on that day. I especially want to thank Henk te Velde and Theo Jung, who insisted that I should pay more attention to the Assembly corridors. I also want to thank the participants in the Intellectual History and Cultural History seminars at the University of Helsinki for their feedback on previous versions of this text. Additionally, I would like to thank Marlene Broemer for her appreciated linguistic revision and suggestions (any remaining mistakes are mine). Finally, I want to thank the Calliope team members Esha Sill, Karen Lauwers and Liesl Yamaguchi, as well as my supervisors Josephine Hoegaerts and Elise Garritzen, for their constructive comments and continuous support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ludovic Marionneau

Ludovic Marionneau is a doctoral student in cultural history at the University of Helsinki, where he is writing a dissertation entitled ‘Pratique du métier parlementaire: Performances in the French Lower Chamber in the Long Nineteenth Century’. Supported by the project ‘CALLIOPE: Vocal Articulations of Parliamentary Identity and Empire’ (ERC StG 2017), his research examines representatives’ parliamentary performances in the French Chambers, with an emphasis on sounds, space and objects in the political and cultural space of the assemblies.

Notes

1. Journal du Commerce, 04-03-1823, 1.

2. Gardey, Scriptes de la démocratie, 202.

3. Heurtin, L’espace public parlementaire, 177.

4. Burke, “Performing History,” 43.

5. Le Moniteur universel (MU), 27-02-1823, 4.

6. Bouchet, Noms d’oiseaux, 29.

7. MU, 02-03-1823, 2.

8. Capefigue, Histoire de la Restaurations, 87–127; de Vaulabelle, Histoire des deux Restauration, 248–358.

9. De Cormenin, Le livre des orateurs, 293–301.

10. Fayat, “Bien se tenir à la Chambre,” 64; Garrigues, Histoire du Parlement, 161; El Gammal, Être parlementaire, 37.

11. Jung, “Auftritt durch Austritt,” 40–3.

12. Bouchet, Noms d’oiseaux, 22–36.

13. Caron, “Les mots qui tuent,” 24–5.

14. D’Almeida, “Pour une chronologie de l’éloquence démocratique,” 3.

15. Burke, “Performing History,” 35.

16. Rai, “Political Performance,” 3.

17. Reid, Imprison’d Wranglers, 191–213.

18. Hoegaerts, “Speaking Like Intelligent Men,” 138–9.

19. Finlayson, “Becoming a Democratic Audience,” 99–100.

20. Rai, “Political Performance,” 5–6.

21. Gardey, Le linge du Palais-Bourbon, 39.

22. Ibid., 70.

23. Bonnard, Les règlements des assemblées, 230–1.

24. Bonnard, Les règlements des assemblées, 229.

25. Heurtin, L’espace public parlementaire, 17–19.

26. Heurtin, L’espace public parlementaire, 104–5.

27. Fayat, “Bien se tenir à la Chambre,” 72.

28. Bonnard, Les règlements des assemblées, 211, 223.

29. Pierre and Poudra, Traité pratique de droit politique, 122–3.

30. Bonnard, Les règlements des assemblées, 230.

31. Ravel, “Le théâtre et ses publics,” 113–18.

32. MU, 13-03-1820, 6.

33. Reid, Imprison’d Wranglers, 2–3; Fisher-Lichte, “Performance as Event,” 31.

34. e.g. Journal du Gard, 08-03-1823, 1–3.

35. Coniez, Écrire la démocratie, 99–107.

36. Gardey, “Turning Public Discourse into an Authentic Artefact,” 841.

37. Gardey, “Turning Public Discourse into an Authentic Artefact,” 838.

38. Hoegaerts and Marionneau, “Throwing One’s Voice,” 101–4.

39. Respectively in the footnotes: QTDN, DPB, GDF, CST, JDC, JDDPL.

40. Fayat, “Bien se tenir à la Chambre,” 62.

41. Heurtin, L’espace public parlementaire, 9.

42. Bonnard, Les règlements des assemblées, 223.

43. Bonnard, Les règlements des assemblées, 222, 224.

44. JDDPL, 22-02-1823, 2.

45. GDF, 22-02-1823, 2.

46. Bonnard, Les règlements des assemblées, 223–4.

47. JDDPL, 22-02-1823, 3; CST, 22-02-1823, 3.

48. CST, 26-02-1823, 4.

49. Ibid., 5.

50. Ravel, “Le théâtre et ses publics,” 106–12.

51. Gauchet, “La droite et la gauche,” 2541.

52. CST, 26-02-1823, 4.

53. Bonnard, Les règlements des assemblées, 135–6.

54. CST 26-02-1823, 5; DPB 26-02-1823, 4.

55. DPB 26-02-1823, 8; QTDN, 26-02-1823, 5.

56. MU, 26-02-1823, 7.

57. Fayat, “Bien se tenir à la Chambre,” 72.

58. GDF, 26-02-1823, 6.

59. QTDN, 26-02-1823, 5; GDF, 26-02-1823, 6; JDDPL, 26-02-1823, 6.

60. QTDN, 26-02-1823, 5.

61. GDF, 26-02-1823, 6. DPB, 26-02-1823, 8.

62. QTDN, 26-02-1823, 5.

63. MU, 26-02-1823, 7.

64. CST, 26-02-1823, 5.

65. CST, 27-02-1823, 2.

66. GDF, 27-02-1823, 2.

67. GDF, 27-02-1823, 2.

68. MU, 27-02-1823, 3.

69. Ibid., 3.

70. GDF, 27-02-1823, 2.

71. Rai, “Political Performance,” 10.

72. Caron, “Les mots qui tuent,” 14.

73. JDC, 04-03-1823, 2.

74. JDC, 27-02-1823, 3.

75. Bouchet, Noms d’oiseaux, 23.

76. JDC, 27-02-1823, 3.

77. MU, 27-02-1823, 4.

78. JDC, 27-02-1823, 3.

79. QTDN, 27-02-1823, 3.

80. MU, 27-02-1823, 4.

81. DPB, 27-02-1823, 3.

82. JDDPL, 27-02-1823, 3.

83. Ibid., 3.

84. MU, 27-02-1823, 4.

85. Rai, Political Performance, 5.

86. CST, 27-02-1823, 4.

87. GDF, 27-02-1823, 3.

88. QTDN, 27-02-1823, 3.

89. MU, 27-02-1823, 4.

90. Ibid., 4.

91. JDC, 27-02-1823, 3.

92. MU, 27-02-1823, 4.

93. GDF, 27-02-1823, 3; QTDN,27-02-1823, 3.

94. DPB, 27-03-1823, 3. GDF, 27-03-1823, 3.

95. CST, 27-02-1823, 4.

96. JDC, 27-02-1823, 3.

97. Garday, Le linge du Palais-Bourbon, 218–19; 240–52.

98. Manuel quoting La Bourdonnay: GDF, 28-02-1823, 3.

99. JDDPL, 26-02-1823, 6; GDF, 26-02-1823, 6.

100. CST, 27-02-1823, 3–4.

101. QTDN, 27-02-1823, 4.

102. QTDN, 27-02-1823, 3–4; GDF, 27-02-1823, 3–4; JDDPL, 27-02-1823, 4.

103. QTDN, 01-03-1823, 4.

104. JDC, 6-03-1823, 2.

105. DPB, 22-03-1823, 2.

106. QTDN, 6-03-1823, 3; JDDPL, 7-03-1823, 4.

107. QTDN 15-03-1823, 4.

108. DPB 19-03-1823, 2.

109. GDF, 18-03-1823, 3.

110. Le Petit Journal, 14-03-1872, 1.

Bibliography

- Bonnard, R. Les règlements des assemblées législatives de la France depuis 1789. Paris: société anonyme du recueil Sirey, 1926.

- Bouchet, T. “La Révolution dans l’hémicycle: Violence courtoise de l’insulte.” In Noms d’oiseaux. L’insulte en politique de la Restauration à nos jours, 22–36. Paris: Stock, 2010.

- Burke, P. “Performing History: The Importance of Occasions.” Rethinking History 9, no. 1 (2005): 35–52. doi:10.1080/1364252042000329241.

- Capefigue, B. Histoire de la Restauration et des causes qui ont amené la chute de la branche aînée des Bourbons. Vol. 8 of Histoire de la Restauration et des causes qui ont amené la chute de la branche aînée des Bourbons. 2nd ed. Paris: Duféy, 1831–1833

- Caron, J.-C. “Les mots qui tuent: Le meurtre parlementaire de Manuel (1823).” Genèses 83, no. 2 (2011): 6–28.

- Coniez, H. Écrire la démocratie: De la publicité des débats parlementaires. Paris: L’Harmattan, 2012.

- D’Almeida, F. “Pour une chronologie de l’éloquence démocratique.” In L’Éloquence politique en France et en Italie de 1870 à nos jours, edited by F. d’Almeida, 1–13. Rome: École française de Rome, 2001.

- de Cormenin, L.-M. de Laye. Livre des orateurs. 11th ed. Paris: Pagnerre, 1842.

- de Vaulabelle, A. Histoire des deux Restaurations jusqu’à l’avènement de Louis-Philippe. Vol 6 of Histoire des deux Restaurations jusqu’à l’avènement de Louis-Philippe. 7th ed. Paris: Perrotin, 1869.

- El Gammal, J. Être parlementaire du XVIIIème siècle à nos jours. Paris: Armand Colin, 2013.

- Fayat, H. “Bien se tenir à la Chambre: L’invention de la discipline parlementaire.” Jean Jaurès. Cahiers trimestriels 153, no. 3 (1999): 61–89.

- Finlayson, A. “Becoming a Democratic Audience.” In The Grammar of Politics and Performance, edited by S. Rai and J. Reinelt, 93–105. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Fisher-Lichte, E. “Performance as Event – Reception as Transformation.” In Theorising Performance: Greek Drama, Cultural History and Critical Practice, edited by E. Hall and S. Harrop, 29–42. London: Bloomsbury, 2010.

- Gardey, D. “Turning Public Discourse into an Authentic Artefact: Shorthand Transcription in the French National Assembly.” In Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy, edited by L. Bruno and P. Weibel, 836–843, London: MIT Press, 2005.

- Gardey, D. “Scriptes de la démocratie: Les sténographes et rédacteurs des débats (1848-2005).” Sociologie du travail 52, no. 2 (2010): DOI:10.4000/sdt.13695.

- Gardey, D. Le Linge du Palais-Bourbon: Corps, matérialité et genre du politique à l’ère démocratique. Lormont: Le Bord de l’Eau, 2015.

- Garrigues, J., ed. Histoire du Parlement: De 1789 à nos jours. Paris: Armand Colin, 2007.

- Gauchet, M. “La droite et la gauche.” In Les lieux de mémoire, tome II: La nation, edited by P. Nora, 2533–2601. Paris: Gallimard, 1997.

- Heurtin, J.-P. L’espace public parlementaire: Essai sur les raisons du législateur. Paris: Presse Universitaire de France, 1999.

- Hoegaerts, J. “Speaking like Intelligent Men: Vocal Articulations of Authority and Identity in the House of Commons in the Nineteenth Century.” Radical History Review 121, no. 121 (2015): 123–144. doi:10.1215/01636545-2800004.

- Hoegaerts, J., and L. Marionneau. “Throwing One’s Voice and Speaking for Others: Performative Vocality and Transcription in the Assemblées of the Long Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies 6, no. 1 (2021): 91–108.

- Jung, T. “Auftritt durch Austritt: Debattenboykotts als parlamentarische Praxis in Großbritannien und Frankreich (1797–1823).” Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 58 (2018): 37–67. doi:10.6094/UNIFR/151306.

- Pierre, E., and J. Poudra. Traité pratique de droit parlementaire. Paris: Librairie de J.Baudry, 1878.

- Rai, S. “Political Performance: A Framework for Analysing Democratic Politics.” Political Studies 63, no. 5 (2014): 1179–1197. doi:10.1111/1467-9248.12154.

- Ravel, J. S. “Le théâtre et ses publics: Pratiques et représentations du parterre à Paris au XVIIIe siècle.” Revue d’histoire moderne & contemporaine, no. 49–53 (2002): 89–118. doi:10.3917/rhmc.493.0089.

- Reid, C. Imprison’d Wranglers: The Rhetorical Culture of the House of Commons 1760–1800. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.