ABSTRACT

Neopatrimonialism has explanatory power regarding the limitations of post-war democratization because it considers the combination of formally-democratic institutions together with power relations based on patronage. Neopatrimonialism does not however explain why marginalized groups make political claims in such inhospitable climates, nor have their experiences of governance processes been adequately explored. This paper addresses this gap based on empirical research in Bosnia-Herzegovina, applying a framework of civic agency to elaborate the goals and capacities of civil society actors. Under what conditions can civic agency foster inclusive governance outcomes? The research found that perceptions of limited and ambiguous outcomes from engagement in governance processes encourage civil society organizations to have incrementalist goals and limit self-perceptions of capacity. Inclusive outcomes were nonetheless more likely with persistent intentions and actions. Transactional capacities based on ties to political actors rather than participatory capacities based on political mobilization were more likely to lead to inclusive governance outcomes.

Introduction

Scholarship of democratization within “liberal peace” intervention after war has frequently characterized the resulting governance as “(mere) electoral democracy”.Footnote1 The (lack of) political and civil rights however does not completely describe the ways that formally democratic governance can be devoid of a democratic essence that includes all citizens. Elections are not a guarantee of accountability to citizens or the public good as implied in Tilly’s definition of democratic governance as one in which “political relations between the state and its citizens feature broad, equal, protected, and mutually binding consultation”.Footnote2

Bosnia-Herzegovina is chronologically the second oldest of 19 major peacebuilding interventions since 1989 with the highest per capita value of post-conflict aid and as a result provides an extreme and instructive case.Footnote3 The persistence of nationalist party elites has been explained by post-war power structures based on patronage of state jobs and funds, connections to criminal elements, economic informality, and control of state-owned enterprises.Footnote4 In addition to their central role in post-war politics, clientilistic relationships and ethnic division are also seen as central for social order.Footnote5 These two characteristics are mutually reinforcing in that patronage networks have been strengthened by the ability to divide and conquer potential common interests of groups of citizens along ethnic lines.

Based on these findings, governance in Bosnia and Herzegovina can be characterized as neopatrimonialism, defined by patronage and clientilistic power relations within the institutions of rational-legal statehood.Footnote6 Patrimonial power relationships and neopatrimonialism have also been used to describe and explain post-war governance in countries including Cambodia, Liberia, Afghanistan, and Rwanda.Footnote7 These power relations are used to explain low levels of institutional responsiveness to citizens’ concerns and an equilibrium lacking in inclusive governance outcomes which benefit marginalized groups. In addition, neopatrimonialism means that “formal rules, elections and public bureaucracies exist and matter but in the reality of neopatrimonial regime informal rules and norms take precedence over formal institutions”.Footnote8 The degree of divergence between formal institutions and informal rules provides another reason for pessimism if even the few formal outcomes benefiting marginalized groups are not followed by substantive outcomes in practice.

A vigorous civil society (CS), a central stated objective of liberal peace interventions, is assigned a role within CS theory as watchdogs over government officials, holding them accountable, and as articulators of public interests.Footnote9 Empirically, however, civil society organizations (CSOs) in post-war states have rather frequently been observed to play apolitical roles or to articulate illiberal ideologies, pointing to the lack of conceptual clarity provided by CS theory in regard to governance roles.Footnote10 The literature on Bosnia following CS discourse has been largely pessimistic about the potential for CSOs to influence governance outcomes along these lines and has extensively elaborated the ways that structural factors (characteristics of interventions and intervenors, levels of CSO membership and generalized trust) lead to CSO-state disengagement and apolitical roles.Footnote11 Neopatrimonialism however provides an undifferentiated view of society-state interactions which empirically demonstrate variability. Lacking in these conclusions is a systematic examination of cases of CSO engagement. As a result the experiences of CS–state interactions remain unexplored, while doing so may reveal and help to explain this variability and ultimately the characteristics of actors that engage in them.Footnote12

Civic agency has been proposed as an alternative to address this plurality and ambiguity of CS discourses and diversity of context-specific expressions.Footnote13 This article will explore how neopatrimonialist post-war governance shapes and constrains the agency of CSOs and the governance outcomes that they are able to achieve. Civic agency can thus provide needed nuance to the rather deterministic structural perspective of neopatrimonialism. This is relevant as Dolenec has concluded that in the absence of elite decisions and limited sovereignty – conditions that apply to many post-war contexts – democratization “happens gradually through the strengthening of independent social spheres, citizens and associations that control the abuse of power that is so dear to the political elites of the region”.Footnote14

The incremental, bottom-up democratization thesis however depends on the efficacy of citizens and associations in achieving outcomes from their interactions with the state. Civic agency is a framework for understanding why CSO actors engage with and struggle against the state given an inhospitable neopatrimonialist climate and a potentially low sense of efficacy. The article will elaborate and apply civic agency to illuminate struggles involving CSO participation in governance processes. The research was guided by the following question: Under what conditions can civic agency contribute to inclusive governance outcomes?

The article makes several contributions to the literature on post-war governance. The application of “civic agency” provides clarity to debates regarding “local agency” by elaborating the factors leading to the emergence of agency vis-à-vis the state. Adopting civic agency as an object of study can provide insight into its origins and development by a longitudinal focus on the self-conceptualization of specific actors. Secondly, patronage and clientilism have been commonly referred to in order to explain the lack of intended outcomes of intervention, abuse of public resources, and low levels of public goods. Neopatrimonialism in contrast is more normatively neutral in the way that it describes patterns of interaction and expectations which constrain the agency of actors within the state and society. By adopting it, this article contributes to understanding the possibilities for agency of both CSO and state actors. Its application can provide a framework for clarifying the origins and structural limitations to this agency.

Based on extensive empirical research within eight case study CSOs in Bosnia-Herzegovina, the article applies civic agency as a framework to explain the conditions and outcomes of CSO–state interactions. The women’s, youth, and social welfare CSOs were selected based on their articulation of political goals as identified by key informants. For each CSO, one to three initiatives were investigated in-depth using process tracing to document the goals, actions taken, outcomes, and multiple perspectives on the reasons for the outcomes. Interviewees referred to “dead letters on a page” (mrtvo slovo na papiru) to describe unimplemented formal outcomes of engagement with the state and indicating the experience of neopatrimonialism. Despite this description, the article does find that the combination of persistent political claims and application of predominantly transactional capacities vis-à-vis political actors can lead to inclusive governance outcomes.

Theoretical framework

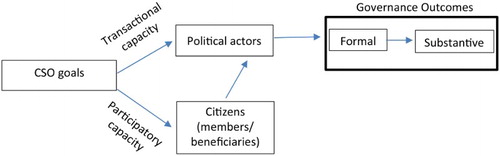

Civic agency is situated within debates regarding local agency in the liberal peace literature, followed by a discussion of the definitions and literature on the civic agency concept which provide a basis for its operationalization. Civic agency is approached via the distinction between participatory and transactional capacities. The framework concludes by diagramming the relationships explored in the research question and two subquestions.

Civic agency

The exploration of civic agency can benefit from following Richmond and MacGinty’s call towards a “local turn”, meaning a shift in epistemology from interventionism to the ideational constructions of local actors and the processes, practices, and interrelationships that shape them.Footnote15 Liberal peace literature has emphasized local agency and the “hybridity” that result from the meeting of indigenous and external discourses, actors and political projects but there are varied meanings for local agency.Footnote16 For authors in the critical International relations tradition the locus of local agency is resistance to the hegemonic dimensions of liberal peace interventions and understanding and engagement with local agency is central to conceptualized emancipatory approaches to peacebuilding.Footnote17 In policy debates about increasing local ownership, interest is largely focused on understanding the agency of elites.Footnote18 Local agency can also mean a focus on grassroots agency and small-scale and everyday actions, at times considered “hidden agency”.Footnote19 Finally local agency can mean to focus on the struggles which lead to legitimate institutions in different contexts based on local-international mixture of identities, norms, and practices.Footnote20 These myriad definitions raise the question of whether local agency provides conceptual clarity given that it reflects respective authors’ epistemological frameworks. This is made explicit in David Chandler’s critique of grassroots understandings of local agency based on the way that it locates the barriers to development at the ideational level without considering structural limitations.Footnote21

Civic agency may have utility within these debates because it is explicit about its normative assumptions and narrower in its focus. Civic agency was defined by Boyte to mean “people’s capacities, individually and collectively, to be agents of their lives and of development”, within its proponents’ research agenda of “civic driven change” (CDC).Footnote22 This agenda focuses on a system of governance that fosters self-organization around politically-empowering projects.Footnote23 Civic agency does not adopt a position restricting local agency to grassroots or elites as articulated above. Rather it focuses on agency on behalf of collectivities vis-à-vis the state.Footnote24 In this point it is more explicit in its focus on the connection between CSO action and governance than CS discourses. Moreover, its adoption focuses attention on those CSOs which do articulate political goals despite the limitations of a neopatrimonialist system and what can be learned regarding their experiences of engagement in governance processes. This attention may provide insight into the process of strengthening pluralist power relations often understood to be central to democratic governance.Footnote25 Relevant to neopatrimonialism is the potential of CDC to look “beyond political structures and mechanisms, such as voting, to the historical processes and fundamentals of power accumulation and reproduction”, and its sensitivity to contention between endogenous and exogenous values, measures, and processes.Footnote26

Although agency is central to actor-based theoretical models, it can be challenging to operationalize. As put by Long: “Agency is usually recognised ex post facto through its acknowledged or presumed effects”.Footnote27 To answer this challenge, for this inquiry civic agency was defined as “the intention, perception of capacity, and action to create change for a common good” leading to operationalization based on the intentions, capacities, and actions. Framing as “a common good” lies between the easily contested “public good” subject to the logic of collective action, and partial or club goods which only benefit contributing members.Footnote28 A common good is thus understood as a non-excludable good from which a group beyond those who directly contribute benefit. While this definition notes that capacities and perceptions of capacities are a needed component to understand and analyse civic agency, the following section will turn to examining two forms of capacity from empirical research.

Participatory and transactional capacities

Scholarship on political mobilization by CSOs in Eastern Europe has found that low levels of individual participation and CSO membership do not inherently limit the CSO capacities and the efficacy of CSO action. Rather this research suggests that analysis of individual participation as “participatory activism” should be complemented by theory of “transactional activism”: “ties – enduring and temporary – among organized nonstate actors and between them and political parties, power holders, and other institutions”.Footnote29 Participatory activism encompasses individual and group participation in civic life, electoral politics, and interest group activities as well as contentious politics. Transactional activism was formulated based on observed salience of linkages between grassroots organizations protesting the building of a new ring road around Budapest to NGOs with professional advocacy and subject expertise and to authorities which facilitated negotiation related to activists’ goals. Its transactional nature relates to strategic networking and problem-solving with authorities as means to achieve desired ends. Proponents of transactional capacity do not dispute the weakening effects of low CSO membership, rather they claim that the transactional character of activism merits attention due to its implications for the potential of coalition building, and negotiation with the state and elites.Footnote30 The two forms are additionally distinguished by the way that the media is used in transactional activism to shape public debates and influence various publics, rather than to mobilize for protest events.Footnote31 This observation regarding the use of media in transactional activism was also observed in the case studies.

The transactional characterization can be understood to emphasize temporary and instrumental characteristics, however the definition above focuses on the ties – the relationship – itself. Since many transactions are eased by relationships of trust, transactional capacity also includes a relational dimension. Although the advocacy actions encompassed within “transactional capacity” are similar to those of interest groups within pluralist democratic governance,Footnote32 proponents of the concept argue that it is the ties themselves and character of the relationships that are the source of capacity within democratizing polities rather than participatory mobilization and its influence on public opinion and electoral politics.Footnote33 “Perception of capacity” in the operationalization of civic agency refers to the actors’ reflexive understandings; it is not just analysis of the actions undertaken that provides analytical clarity but also the actors’ understandings of their efficacy. Neopatrimonialism may shape provisions for participation in that decision-making power does not reside in formal institutions and participation mechanisms but rather these institutions become permeable to the personal interests and preferences of some state officials. This inquiry then may provide insight into the way that a neopatrimonialist context shapes and constrains civic agency. The observed distinction between participatory and transactional capacity helps to form the expectation before commencing the empirical research that transactional capacity may be more effective than participatory capacity given a neopatrimonialist context.

The article will elaborate and apply civic agency to illuminate struggles involving CSO participation in governance processes. The research was guided by the following question: Under what conditions can civic agency contribute to inclusive governance outcomes? In order to answer this question, two subquestions will be first explored: Are governance outcomes formal or substantive? and Do CSOs demonstrate participatory or transactional capacities? The addressed concepts and relationships are shown in .

Methodology

Data was collected via triangulation of methods using semi-structured interviews, document analysis, and process tracing.Footnote34 Three focus areas of youth, women, and social welfare were chosen as groups marginalized within patronage-based power structures.Footnote35 Interviews with 27 key informants, selected to represent diverse and socially-significant perspectives,Footnote36 were used to identify change initiatives by registered CSOs within each focus area vis-à-vis the state at any level. Rather than a representative sample of all CSOs, CSOs were thus selected based on demonstrated articulation of political goals in order to explore their potential contribution to inclusive outcomes. This choice follows from the research interest in the conditions under which civic agency contributes to inclusive outcomes. Inclusive outcomes were understood as those that benefit the marginalized groups and the narrative will elaborate how the outcomes were assessed for inclusiveness.

The suggested CSOs were further researched to identify their constituencies, defined as members and beneficiaries.Footnote37 Selecting cases based on those with identified articulation of political goals and constituencies followed a most-likely case study methodology in that CSOs were selected which were most likely to demonstrate civic agency.Footnote38 The restriction to CSOs with constituencies further facilitated assessing the object of “a common good”. In addition, the presence of constituencies enabled potential participatory capacity through mobilizing of constituents, providing better data from which to investigate capacities present in the definition of civic agency. Fifteen CSOs were selected from three major urban areas for initial interviews which gathered further information about their change initiatives.Footnote39 For each potential case study CSO, a list of change initiatives with political goals was composed based on document analysis and an interview with CSO leadership.

This article is based on eight case study CSOs which were selected to include each urban area and focus area of work. The case study CSOs were diverse in size (numbers of staff, budgets) and sources of funding (donor funds, government, membership and donations). In selecting one to three of the initiatives for further study, a criteria was that given outcomes indicated an ongoing policy change, rather than for example a onetime financial allocation. Preference was also given to completed processes, although as the narrative will explain this turned out to be more ambiguous in practice. In some cases completed meant withdrawal from the process without achieving the intended outcome. The inclusiveness of outcomes was investigated using the number of participants and beneficiaries from the respective constituencies and whether outcomes applied to all members of an intended group. Process tracing involved interviews with state and other CS actors and relevant internal and public document review. Selected initiatives had existed for at least one year in order to provide material for the process tracing.

Process tracing was selected in order to examine causal processes between initial conditions and governance outcomes, factoring in responses of multiple actors in their context, based on its suitability for understanding decision-making.Footnote40 It factored in the actions and explanations of other stakeholders and the political actors who made the decisions which lead to a given observable outcome, rather than taking CSO claims of attribution at face value. In the process tracing, the hypothesis that CSO actions contributed to observed outcomes was weighed against alternative explanations. It covered the time from assertions of goals to the outcomes claimed by CSOs. In addition, ongoing events after the outcomes were also investigated. Triangulation provided multiple data streams regarding key events and decisions which were used to assemble narrative descriptions. The process tracing included contextual analysis of relevant initiatives and actions by other actors. The observed outcomes, types of actions taken, and relative contribution of civic agency to the outcomes in contrast to actions by other actors formed the basis for answering the research question.

During the process tracing there were several methodological challenges. The outcomes were selected based on CSO interviews, thus there was a potential bias based on self-aggrandizing narratives and financial interest to justify outcomes to donors. Secondly the neopatrimonial environment fosters obscuring of political decisions, often the decision-making process, and potential financial interests. Finally the subjective nature of determining the relative contribution of CSO action to confirmed outcomes creates the possibility of confirmation bias on the part of the researcher. In order to mitigate these factors, document review was used to confirm the outcomes and sequence of events. The outcomes were also investigated regarding their inclusiveness as described above. The actors’ accounts of when one event led to another was evaluated based on the sum of the evidence including whether two events happened close in time. In a small number of cases, decision makers explicitly identified the causal role of CSO agency leading to a given outcomes which was given particular weight.Footnote41 Both the evidence for the role of CSO actions and for that of the actions of other actors is available in the supplemental materials.

Findings

The findings section begins by grounding the narrative with an analysis of each of three fields of action. The two subquestions address civic agency via the components of its definition: focusing on goal formulation, the actions taken and their implications for understanding the salience of CSO capacities, and the nature (formal or substantive) of the outcomes. These subquestions are used as a basis for a more challenging examination of the evidence for a causal link between civic agency and inclusive outcomes and the conditions that fostered this result.

Governance outcomes

The following analysis focuses on civic agency on the part of women’s, youth, and social welfare CSOs in turn, particularly addressing whether formal outcomes were followed by substantive outcomes. Addressing domestic violence was a primary governance goal of each of the women’s CSOs identified by key informants and is illustrative because of the possibility to study parallel processes in the sub-national Federation and Republika Srpska (RS), each of which have their own criminal codes, police, and responsible social welfare institutions. The outcomes claimed by the case study CSOs include establishment of domestic violence shelters, criminalization of domestic violence, and improved responses to victims by state institutions such as the police, schools, and centres for social work. Domestic violence was criminalized in both the Federation and RS which was initially resisted by the drafting Ministries and remains a subject of ongoing contestation on the part of a case study CSO in the RS.Footnote42 The system of (partially) publicly-funded domestic violence shelters, run by CSOs, represents an atypical success in securing public funds on an ongoing basis.

When asked about the impact of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to coordinate responses to domestic violence victims, one policewoman in Mostar indicated its relevance by quickly pulling it out of the papers on her desk. However, she also noted its lack of implementation in practice because of regulatory and budgetary factors both in her own but also other signatory institutions.Footnote43 Similar CSO-initiated MOUs have also contributed to positive changes in the responses to calls related to potential domestic violence on the part of local police and centres for social work.

However, most of the formal outcomes beneficial to domestic violence victims were infrequently implemented if at all. This was due to institutional weaknesses (legal inconsistencies, varied interpretations, lack of developing mandated guidelines necessary for implementation of the law) and apparently a lack of will to allocate the necessary funds. Having undertaken commitments to fund domestic violence shelters, both Federation and RS Ministries introduced extensive technocratic criteria for the selection of CSOs to run them.Footnote44 In the perceptions of CSO actors, the intention was to secure state funds for politically-acceptable CSOs or to bring them under the control of political actors in place of those that had advocated for their adoption. Substantive outcomes regarding police and court responses to domestic violence have been similarly limited and inconsistent.

The outcomes that case study youth CSOs claimed as the result of their actions were regular activities and educational efforts with public funds up to 10,000 Euros/year per CSO. The CSO Democratic Youth Movement (DYM) committed volunteer time over a one-year period to participate in the creation of the Novo Sarajevo municipal youth strategy and lobbied at budget hearings to maintain its funding.Footnote45 Its implementation once approved however was repeatedly delayed for political reasons (suspension during an election campaign) and bureaucratic reasons (budgeting cycles, delays due to writing regulations for a tender process).Footnote46 A Mostar youth strategy, initially proposed by the CSO Abrašević in 2007, and finalized for adoption by November 2012, had neither been made available nor was scheduled for approval as of January 2016.Footnote47 Abrašević’s successful claim to a property title was the only such case that was observed over three years of fieldwork, and based on this resource Abrašević continues to offer cultural programmes as well as demonstrating civic agency by supporting city-level activism with broad transformational goals.

For the families of developmentally-disabled individuals (DDIs) in the RS, formal outcomes include the introduction of daily centres and minimal (41–82 €/month) financial support.Footnote48 Substantive outcomes were limited by the introduction of new procedures which required yearly verification of disability status by several doctors, causing a financial burden and delaying benefits particularly for rural beneficiaries. An Open Network campaign in order to establish the infrastructure for organ transplants appears to have led to the allocation of funds and the establishment of transplant teams.Footnote49 Substantively, as of 2016 only a few transplants had been conducted.

CSO staff repeatedly observed that formal outcomes had not been implemented in practice, noting that laws, strategies, and conventions are “dead letters on a page”. This image supports the neopatrimonialist framing in the way that these instruments of rational-legal statehood do not indicate, direct, or bind the decisions of state actors or the allocation of state resources. Although weaknesses in institutional capacity can be used to explain this lack of substantive outcomes, proponents of the neopatrimonialist framing should be sceptical that additional capacity would change the underlying power relations and nature of political decision-making.Footnote50 The narrative rather continues by focusing on the implications of this context for civic agency and particularly for the articulation of goals vis-à-vis the state.

Interviewees referred to “Fighting against windmills” to describe the experience of engagement with state institutions; referring not to the imaginary nature of the opponent as in Don Quixote but rather the pointlessness of the battle.Footnote51 Their accounts of their own efficacy were characterized as a series of struggles in which the outcomes achieved were followed by retrenchments, leading to the conclusion that their net effect was little change. In response, the case study CSOs did not abandon engagement but did distinguish intermediate goals, characterized by formal and institutionalist characteristics from ultimate goals, characterized by substantive outcomes. The discrepancy between formal and substantive outcomes is likely why CSO intentions regarding CSO–state interactions remain very limited in scope and scale. As related by a staff person working on behalf of the developmentally disabled:

In the negotiations with the state, we say we have 10 needs of particular rights to be regulated by law or to be implemented, let’s go with 1 or 2 for the next 3 years, that we’ll put aside and go step-by-step … The problem is that the rights which exist in certain laws are not implemented in practice or the internal inconsistencies within the entity [law].Footnote52

CSOs received responses regarding the lack of available funds for achieving CSO goals and perhaps as a result focused on modest improvements rather than broader contestation of political priorities. The goals of the studied CSOs were also limited in that they were extremely rarely expressed in the form of implementing national solutions, likely due to pragmatic calculation of potential success given the political salience of centralization/decentralization debate as a focus of dominant ethno-nationalist political contention, the risks related to challenging nationalist political projects, and personal political orientations. Within incrementalist goals, an interviewee countered descriptions of “dead letters on a page”: “Some say it’s only paper, paper, paper. We’re satisfied with what we’ve done. We’re a women’s organization that works within Mostar and Mostar is saturated with our activities. And that’s what we figured out we needed to do”.Footnote53 The ambiguous picture of the outcomes and varied understandings of efficacy provide the context for considering the next subquestion regarding the capacities applied by the case study CSOs.

Do CSOs demonstrate participatory or transactional capacities?

The process tracing provided significant evidence that transactional capacity, based on ties between CSOs, on the one hand, and state actors, elites, or other CSOs, on the other hand, was necessary in achieving intended outcomes. Despite this salience of transactional capacity, the processes studied also include some indications of participatory capacities. The interaction of multiple capacities will be explored by two case studies, the first of which is related to advocacy regarding treatment of domestic violence in the RS. The second considers an initiative regarding local policy undertaken by the Sarajevo youth organization DYM. Despite the heterogeneity of the two cases regarding location and beneficiary population they demonstrate commonalities regarding the links between CSO action and achieved outcomes and the ways that the case study CSOs responded to political opportunities.

United Women’s (UW) office gives the impression of activism and activity by the posters informing about domestic violence hotlines, the space filled with staff and shelves stuffed with archives of previous projects. Annual reports indicate its success in securing donor funds as well as ongoing municipal and RS financial support and legislative and regulatory outcomes related to victims of domestic violence. Seeking government rather than donor funding is indicated in the awarding of land by Banja Luka City for a shelter for domestic violence victims in 2002, attributed to cooperation between the organization and allies in the City Assembly.Footnote54 When the city administration did not provide funding as agreed, in 2005 UW lobbied via the use of media and direct advocacy with political actors at the local and RS levels and was successful in securing funds for renovation and furnishing the shelter which accepted its first beneficiaries in February 2007.Footnote55 Seeking state funds was a strategic choice, as indicated by one staff person:

We could have received international funds for the shelter from the very beginning but we didn’t want that. We wanted the state to systematically address that question and that it should be a legal responsibility of the state to provide the service and to financially support it.Footnote56

In 2007, UW responded to an institutional provision for participation by submitting written proposals and the participation by UW President Nada Golubović as a sole CSO member in a working group related to the amending of the existing Law on Protection from Domestic Violence in the RS. UW’s goals were to secure more consistent funding for all three safe houses that had been established in the RS by obligating the RS to provide funding, and to treat domestic violence only as a criminal act. In the discussion regarding whether it is a misdemeanour or a criminal act, UW President Golubović was alone in arguing for a change to be treated only as a criminal act and ultimately did not support the final recommendation of the working group and instead submitted a separate recommendation.Footnote57 UW engaged in subsequent lobbying via female parliamentarians with whom it had already established relationships.Footnote58 The amended law as adopted established that the RS should cover 70% of the cost and municipalities 30% for housing victims and children in a safe house but domestic violence continued to be treated as a misdemeanour. The relevance of the personal orientation of state officials rather than merely implementation of established law was demonstrated when Assistant Minister for Health and Social Welfare Ljubo Lepir publicly challenged the safe house model, arguing that it did not solve the problem of domestic violence because the victims’ only recourse after residing in the safe house was to return to the same household.Footnote59 Lepir was seen as an opponent because he had earlier publicly challenged the analysis of UW related to domestic violence and the professional qualifications of the staff. The transfer of administration of the safe houses to the Ministry of Family, Youth, and Sports (FYS), headed by previous UW ally Nada Tešanović, was welcomed. Although the 2008 revised Law required the revision and creation of numerous regulations within six months, this had not been done as of 2013, five years after its adoption. UW’s action to organize a round table in cooperation with the Ministry FYS was followed by the formulation and adoption of the guidelines related to the operation and funding of safe houses.Footnote60 Finally it is worth noting that additional case study CSOs engaged in actions regarding both establishment, regulation, and funding of domestic violence shelters and criminalization of domestic violence in the Federation which demonstrated largely similar dynamics regarding goals, capacities, and outcomes.

DYM began among university students in Sarajevo in 2005 articulating opposition to nationalism and in the early days an attempt to overcome ethnic division by creation of a Banja Luka (RS) chapter. By 2011 however, it consisted of 300 members in Sarajevo including 40 active members without staff or an office but as will be seen civic agency able to respond to opportunities. In 2009, DYM was invited by Faruk Pršeš, the head of the Novo Sarajevo municipal Department for Societal Activities, along with eight other organizations to nominate members of working groups for creation of a Youth Strategy for 2012–2014. Of interest for this analysis are the actions taken by DYM in support of adoption of the Strategy and to advocate for its funding despite opposition by political parties in the Municipal Assembly. DYM activists reported that meetings with municipal assembly members and a reputation for partisan autonomy helped to achieve approval in lobbying for adoption of the Strategy over expressed political hesitations that doing so would benefit the incumbent mayor during an election campaign.Footnote61 Further, they responded to opportunities for participation by advocacy in public hearings on the budget, leading to restoration of full funding.Footnote62

These two cases are representative of the case study CSOs in that they indicate that a highly salient capacity is relationships with political actors developed over multiple interactions. The nature of this capacity and how it develops can be examined from the perspectives of CSO actors and political actors. CSO actors describe effective lobbying and “political action” as lobbying in person: “Now it seems in this existing system the most effective method is political action, direct political action, lobbying party caucuses”.Footnote63 Frequent government changes are seen as an obstacle to developing the necessary kinds of relationships which demonstrated the importance of continuity.Footnote64 Women’s CSOs also directly engaged repeatedly with a few legislators and political actors related to legal and regulatory change processes.Footnote65 Political actors for their part emphasized that they chose to work together with CSOs with particular characteristics. DYM was invited to participate in the Youth Strategy based on the assessment that they would complete the task and build support for adopting the outcome. In several of the cases political actors emphasized working with CSOs that represented particular groups of members or beneficiaries. A parliamentarian highlighted the expertise of CSO members of a working group. This supports the transactional characterization in addition to the relational one – that is CSOs benefit when they can bring effectiveness via expertise and social acceptance via their members. A more critical assessment while still confirming the transactional nature was given by DYM, whose staff later assessed that the Youth Strategy was beneficial for the mayor’s re-election campaign but that neither DYM nor youth as a group had received the anticipated benefits.Footnote66

Although transactional capacity was more salient for the outcomes, some of the same case study CSOs also demonstrated willingness to mobilize supporters and the public. For example, procedures for public calls in order to receive state funds were perceived as a front for political preferences and financial interest over those favouring better outcomes, but some of the organizations made their case via the media. Statements such as “We’ll turn the world upside down” by a UW staff person in response to experienced retrenchment in governance outcomes could be taken to indicate participatory capacity within governance processes via contentious politics. On closer examination, however, what was almost always meant were calls for protest via mass media that in the opinions of the CSO actors would influence key decision makers. This matches previous findings about the use of media within transactional capacity. Contentious politics and other forms of participatory capacity were by themselves rarely perceived by the CSO actors as salient capacities.

The definition of transactional capacity also addresses the quality of relations between CSOs which was observed as an additional factor regarding multiple CSO capacities and outcomes in the case studies. In the face of state unresponsiveness, CSOs reached out to other potential CSO allies but frequently experienced a lack of CSO solidarity and identified this as a reason for reduced outcomes. The case study CSOs, claiming to work on behalf of constituencies, attempted broader mobilization based on an expectation of similar civic agency but were repeatedly rebuffed. Despite these setbacks, several of the case study CSOs were actively working on developing transactional capacity by engaging with selected CSOs on a local or thematic basis.

To summarize the findings to this point, the neopatrimonialist characterization was supported in that formal outcomes were infrequently followed by substantive outcomes (“dead letters on a page”). The experience of engagement with the state which frequently appeared futile (“fighting against windmills”) led to incrementalist framing of goals and limiting of their scope and scale. Transactional capacity via ties between CSO and political actors was an often necessary condition for achieving governance outcomes in a neopatrimonialist context. Participatory capacity via political mobilization was only infrequently observed and mobilization calls also indicated elements of transactional capacity in the strategic use of media. Despite these limitations, there was evidence of civic agency in that many of the studied CSOs have persisted in political claims.

Under what conditions can civic agency foster inclusive outcomes?

This article has advocated the utility of analysing cases of civic agency despite an inhospitable climate. This section addressing the research question will begin by introducing a case from one of the most difficult climates for inclusive governance outcomes, the city of Mostar. Despite the frequent difficulty to achieve substantive outcomes following formal ones as discussed earlier, formal outcomes are nonetheless a necessary precondition. In addition, formal outcomes can be more objectively evaluated as a change and related to the CSOs goals. The section will next summarize the evidence from all of the case studies that civic agency can foster formal outcomes and discuss the conditions under which this happens.

Mostar was divided during the war and despite a period of international administration and extensive international efforts, remains socially divided with separate institutions and spaces.Footnote67 Within this context, youth CSO Abrašević demonstrated civic agency through providing common space, cultural programmes, and support to contentious mobilization. Governance outcomes that Abrašević claimed as successful results of CSO actions included repeated lobbying for municipal financial support (5100 €/year) and a public campaign to secure title to a pre-war centre which identified obstructionist officials followed by a successful court challenge against the city government.Footnote68 Lobbying included direct appeals to municipal assembly members, who indicated that these appeals were effective based on their positive opinion of the organization and the impact of its activities.Footnote69 Further, Abrašević demonstrated agency by active voluntary participation within the Youth Council, established by youth NGOs with municipal support, and initiated re-shaping the council to include high school students’ associations. Their inclusion was accorded significance because they were known for their advocacy in favour of overcoming ethnic division.

The Abrašević case will be used to demonstrate the methodology and support for the findings. Multiple sources and perspectives were used to investigate the decision-making involved in formal outcomes. Abrašević’s advocacy regarding the municipal budget was assessed based on review of their written appeals and the minutes of municipal assembly meetings and changes between drafts of the municipal budget. In addition an assembly member, municipal staff person, and Youth Council staff were also interviewed. These multiple perspectives enabled consideration of evidence that formal outcomes were the result of CSO action against evidence that the outcomes were the results of the actions of other actors. Direct attribution by the decision makers to CSO actions as in the case of the Mostar assembly member, proximity in time between CSO action and outcomes, and review of the context including the (lack of) similar decisions were factors considered. Most importantly weighing evidence in favour of the role of civic agency against evidence in favour of other explanations reduced the reliance on the narratives of CSO actors in causal attribution. This evidence was used to assign each outcome to one of the categories in which indicates that civic agency was a contributing factor in each of the formal outcomes that was investigated. Supporting evidence for each of the cases is available in the online supplemental materials.

Table 1. Factors that contributed to formal outcomes.

Given an unfavourable neopatrimonialist context, one contributing factor to the outcomes was the consistency of intention and persistence of action over years and even decades. As put in one interview: “What’s most important in the whole story is that we don’t give up, that where we see a problem we force it, and initiate a solution”.Footnote70 In another (despite the evident hyperbole):

300 times we sent the head of the Department for Societal Activities a letter, an invitation, we called him, [they say] it’s the first time I hear of it, pass us on to somebody else. They don’t want any kind of cooperation. It’s political, now that is politics. We will be so stubborn that we will enter there.Footnote71

The goals and means of struggle are demonstrated in the reflexive understanding of CSO staff that, “ … we are the constant policemen who constantly register problems in practice, register where there are inconsistencies, register where rights are violated, constantly apply pressure in the sense of ‘people change this’”, whose relation to the state is, “a struggle, to literally claw rights out of your sleeve”.Footnote72 In a context demonstrating a lack of accountability and reliability by institutions to fulfil their statutory obligations, the utility of civic agency is supported by the observation that inclusive substantive outcomes are more likely in the face of CSO consistency of intention and persistence of action.

The findings have implications for understanding bottom-up democratization within a neopatrimonialist context. In the absence of established democratic norms, the orientation of state officials to CS actors varied from open to rejecting. Just as neopatrimonialism permits exploitation of state institutions for personal gain it also frees some state actors from the strictures of bureaucratic and institutional logic, increasing the manoeuvring room and autonomy of those who are reformist-oriented. Transactional capacity between CS and state actors is a property of dyads of actors and depends on repeated interactions and established trust. The transactional dimension however raises the question of the stability of CSO–state links and the degree of institutionalization of inclusive governance practices. Although governance interactions (consultation and verifiable outcomes) were repeated between CSO–state pairs, this rarely expanded to broader links with other CSO or state actors.

This research into the conditions in which civic agency fosters inclusive governance outcomes indicates a paradox between the analysis that civic agency does foster such outcomes and the perceived lack of increasing capacity on the part of the actors. One explanation is the observed distinction between the more common formal and less common substantive outcomes leading to a similar distinction in CSO goal formulation. The often necessary condition of transactional capacity to state actors works against autonomy instead supporting relationships that are at best interdependent. In addition, success regarding substantive outcomes occurred after persistent civic agency focused predominantly on incrementalist rather than transformative goals. Experiences of limited outcomes resulting from incrementalist goals further narrow goal setting regarding future actions oriented towards the state.

Conclusion

This article began by positing that theory and research on governance in a neopatrimonialist context does not adequately explain the variability in society–state interactions, particularly the factors that foster the emergence of CSOs which make inclusive political claims. It adopted the civic agency framework in order to follow the epistemological “local turn” and applied it to the goals and struggles of eight CSOs from marginalized groups. The research found that civic agency characterized by persistent political claims and primarily transactional capacities can lead to formal inclusive governance outcomes. However, experiences of bounded and ambiguous substantive outcomes from engagement in governance processes encourage CSOs to have incrementalist intentions and limit self-perceptions of capacity.

The findings support the potential benefits of additional research regarding transactional capacities in other post-war contexts. Given the relevance of persistent and long-term action in achieving desired outcomes, civic agency can provide insight into the self-conceptualization of the actors that engage in such forms of struggle despite inhospitable climates. Finally, the finding that reformist-oriented state actors often played an enabling (necessary but not sufficient) role in the establishment of inclusive outcomes supports the utility of civic agency over CS theories built on functional sectoral conceptualization.Footnote73 Concretely, the findings point to the relevance of key CS–state dyads for democratic governance processes and suggest civic agency of state actors as an area for further research.

The finding that formal governance outcomes were infrequently followed by substantive outcomes provides additional support for framing democratic governance as neopatrimonialism, emphasizing the persistence of customary order and authority and distinctiveness from consolidated democracy. The relevance of relationships to state actors for achieving given outcomes, regardless of their inclusive nature, can be seen to strengthen personal authority and indirectly neopatrimonialism rather than democratic governance via the rule of law and state capacity. However, the persistence of civic agency applied in order to achieve outcomes demonstrates the potential to use norms of democratic governance to contest the “rules of the game” and hegemony of neopatrimonialism, shedding light on local action and contestation as necessary conditions for long-term processes of post-war democratization.

Supplemental_Data

Download PDF (250.2 KB)Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Kees Biekart, Fabio Andres Diaz, Valery Perry, Mike Pugh, Rosa Rossi, Mathijs van Leeuwen and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. Thank you also to Marlies Glasius, Bertjan Verbeek and Willemijn Verkoren for all of your assistance and to Amela Puljek-Shank for your support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Randall Puljek-Shank is a PhD candidate at the Centre for International Conflict Analysis and Management (CICAM), Institute of Management Research, Radboud University Nijmegen. He holds an MA in Conflict Transformation from Eastern Mennonite University. His research focuses on CSO legitimacy, civic agency and local peacebuilding initiatives.

ORCiD

Randall Puljek-Shank http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7507-6040

Notes

1 Zürcher, “Building Democracy While Building Peace”; Segert and Džihić, “Lessons from ‘Post- Yugoslav’ Democratization.”

2 Tilly, Democracy, 13.

3 Yin, Case Study Research; Zürcher, “Building Democracy While Building Peace.”

4 Donais, The Political Economy of Peacebuilding; Belloni and Hemmer, “Bosnia-Herzegovina”; Segert and Džihić, “Lessons from ‘Post-Yugoslav’ Democratization.”

5 Donais, The Political Economy of Peacebuilding; Belloni, State Building and International Intervention.

6 Richmond and Franks, “Liberal Hubris?”; Ngin and Verkoren, “Understanding Power in Hybrid Political Orders.”

7 Bach and Gazibo, Neopatrimonialism in Africa and Beyond; Zürcher, “Building Democracy while Building Peace.”

8 Guliyev, “Personal Rule, Neopatrimonialism, and Regime Typologies,” 578.

9 Richmond, “Liberal Peacebuilding in Timor Leste”; Howell and Pearce, Civil Society and Development; Kostovicova, “Civil Society in Post-Conflict Scenarios.”

10 The withdrawal of many CSOs from participation in governance has been observed in EU grant recipients in Serbia and Bosnia (Fagan, “Civil Society and ‘Good Governance’”) and “bottom-out” peacebuilding NGOs (Belloni and Hemmer, “Bosnia-Herzegovina.”) See also Paffenholz and Spurk, Civil Society, Civic Engagement.

11 Fagan, “Civil Society and ‘Good Governance’”; Belloni and Hemmer, “Bosnia-Herzegovina”; Paffenholz and Spurk, Civil Society, Civic Engagement.

12 Following Verba et al., Designing Social Inquiry.

13 Fowler and Biekart, “Relocating Civil Society.”

14 Dolenec, Democratic Institutions and Authoritarian Rule.

15 Mac Ginty and Richmond, “The Local Turn in Peace Building.”

16 Richmond, “Resistance and the Post-Liberal Peace”; Millar, “Disaggregating Hybridity”; Ngin and Verkoren, “Understanding Power in Hybrid Political Orders.”

17 Leonardsson and Rudd, “The ‘Local Turn’ in Peacebuilding.”

18 Donais, Peacebuilding and Local Ownership.

19 Richmond, “Critical Agency, Resistance and a Post-Colonial Civil Society”; Mac Ginty and Richmond, “The Local Turn in Peace Building”; Pogodda and Richmond, “Palestinian Unity and Everyday State Formation.”

20 Mac Ginty and Richmond, “The Local Turn in Peace Building.”

21 Chandler, “Peacebuilding and the Politics of Non-Linearity.”

22 Fowler and Biekart, “Civic Driven Change”; Boyte, “Civic Driven Change and Developmental Democracy.”

23 Fowler and Biekart, “Civic Driven Change.”

24 Dagnino, “Civic Driven Change and Political Projects.”

25 Dahl, Who Governs?; Truman, The Governmental Process.

26 Fowler and Biekart, “Relocating Civil Society,” 471.

27 Long, Development Sociology, 240.

28 Olson, The Logic of Collective Action; Welzel et al., “Social Capital, Voluntary Associations.”

29 Petrova and Tarrow, “Transactional and Participatory Activism,” 79.

30 Cox, Interest Representation and State–Society Relations; Petrova and Tarrow, “Transactional and Participatory Activism.”

31 Císař, “Externally Sponsored Contention.”

32 See Truman, The Governmental Process.

33 Cox, Interest Representation and State–Society Relations.

34 Flick, An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 65.

35 As demonstrated in levels of employment 10.9% (youth aged 15–24 actively seeking employment) and 22.7% (women) vs. 31.7% (total population) and 2011 CSO grant support for women’s CSOs (0.7% of total), youth CSOs (2.8%), and for social welfare categories disabled and drug dependency CSOs (5.1%). Labour Force Survey; Center for Investigative Journalism, “Database for Public Fund Allocations.” In addition, 17% of Cantonal ministers and 22% of state ministers were women. Where Are Women in Governments?

36 From the following categories: political actors (4), religious CS (3), media and business (3), CS networks (5), international CS (2), CS Building projects (4), donors (4), and international political actors (2). Key informants were selected based on experience relating to CSOs in addition to their primary sectors.

37 Voluntary financial support and membership as determined by CSO websites and Daguda et al., Annual Financial Reports of Civil Society Organizations; TACSO, Assessment Report on Advocacy Capacity.

38 Yin, Case Study Research.

39 Focus on major urban areas to eliminate related variability in socioeconomic factors and CSO participation rates. UNDP, The Ties That Bind.

40 Reilly, Process Tracing.

41 For example, “CSOs had their suggestions, a significant part which were adopted particularly about people with disabilities, they even influenced that the approach to disability changed from a medical to a social approach to the problem of disability.” (Interview Lepir, 12 November 2013)

42 Regarding criminalization and opposition from relevant ministries see Godišnji Izvještaj 2007 [Annual Report 2007].

43 Interview Hasandedić, 11 November 2014.

44 Creating uncertainty by implementing tenders every six months for shelter providers in the RS, Interview Jančević, 11 April 2013, and potentially bringing the shelters in the Federation under political control by designating that public funds could only be provided to public institutions that would be subject to political appointments, Interview Bečirević, 28 November 2013.

45 Služba za društvene djelatnosti.

46 Interview Pršeš, 1 October 2013.

47 The proximate reason was the lack of formation of a city government since 2011. Civil Society in Action for Dialogue and Partnership Newsletter 6. Interview Memić, 11 November 2014.

48 The only form of assistance that disabled individuals including DDIs receive based on their disability.

49 A Ministry of Health representative agreed that given that implementation had been repeatedly announced over four years but no funds had been allocated demonstrated its newfound political priority in January 2014, three months following an Open Network public campaign. (Interview Čerkez, 14 January 2014)

50 This is the position of authors who advocate statebuilding first such as Belloni, “Civil Society in War-to-Democracy Transitions.”

51 Interviews Hasanbegović, 12 March 2013, Jančević, 4 November 2013.

52 Interview Rađen Radić, 12 November 2012.

53 Interview Hasanbegović, 12 March 2013.

54 2002 Annual Report.

55 Godišnji Izvještaj 2007 [Annual Report 2007]; Annual Report about the Work of the Safe House for Women and Children Victim of Domestic Violence for 2008; 2005 Annual Report of the United Women Association, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina; Memorandum O Razumjevanju I Suradnji [MOU].

56 Interview Petrić, 12 November 2013.

57 Godišnji Izvještaj 2007 [Annual Report 2007].

58 2008 Annual Report of the United Women Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

59 Interview Lepir, 12 November 2013.

60 Službeni Gasnik RS [RS Official Gazette] 25,62,71.

61 Interview Ernad Deni Čomaga, Denis Bahtijarević, 16 November 2012.

62 Supported by comparison of draft and final budgets.

63 Interview Ćorić, 20 February 2013.

64 Interview Ćehajić, 13 April 2013.

65 Attribution of success in securing donated land for a shelter mentioned earlier. 2002 Annual Report.

66 Interview Jovančić and Čomaga, 14 July 2014.

67 Hromadžić, “Discourses of Integration and Practices of Reunification”; Bieber, “Local Institutional Engineering.”

68 Because the budget had not been officially approved but was rather a temporary funding measure the cuts were not allowed by regulation. (Appeal, n.d.)

69 Interview Selma Jakupović, 7 November 2014.

70 Interview Rađen Radić, 11 April 2013.

71 Interview Hasanbegović, 12 March 2013.

72 Interview Rađen Radić, 12 November 2012.

73 Fowler and Biekart, “Relocating Civil Society.”

Bibliography

- 2002 Annual Report. Banja Luka: Udružene žene, 2003.

- 2005 Annual Report of the United Women Association, Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Banja Luka: Udružene žene, 2005.

- 2008 Annual Report of the United Women Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Banja Luka: Udružene žene, 2008.

- Annual Report about the Work of the Safe House for Women and Children Victim of Domestic Violence for 2008. Banja Luka: United Women Banja Luka, 2009.

- Bach, Daniel C., and Mamaudou Gazibo. Neopatrimonialism in Africa and Beyond. Edited by Daniel C. Bach and Mamoudou Gazibo. Routledge, 2012. doi:10.1080/08039410.2013.795458.

- Belloni, Roberto. State Building and International Intervention in Bosnia. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Belloni, Roberto. “Civil Society in War-to-Democracy Transitions.” In From War to Democracy: Dilemmas of Peacebuilding, edited by Anna Jarstad and Timothy Sisk, 182–210. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Belloni, Roberto, and Bruce Hemmer. “Bosnia-Herzegovina: Civil Society in a Semi-Protectorate.” In Civil Society and Peacebuilding: A Critical Assessment, edited by Thania Paffenholz, 129–152. Boulder: Lynne Rienner, 2010.

- Bieber, Florian. “Local Institutional Engineering: A Tale of Two Cities, Mostar and Brčko.” International Peacekeeping 12, no. 3 (2005): 420–433. doi:10.1080/13533310500074523.

- Boyte, Harry C. “Civic Driven Change and Developmental Democracy.” In Civic Driven Change: Citizen’s Imagination in Action, edited by Alan Fowler and Kees Biekart, 119–138. The Hague: Institute of Social Studies, 2008.

- Center for Investigative Journalism. “Database for Public Fund Allocations for Nonprofit Organizations and Public Institutions.”. 2011. http://database.cin.ba/finansiranjeudruzenja/.

- Chandler, David. “Peacebuilding and the Politics of Non-Linearity: Rethinking ‘Hidden’ Agency and ‘Resistance.’” Peacebuilding 1, no. 1 (March 2013): 17–32. doi:10.1080/21647259.2013.756256.

- Císař, Ondřej. “Externally Sponsored Contention: The Channelling of Environmental Movement Organisations in the Czech Republic after the Fall of Communism.” Environmental Politics 19, no. 5 (2010): 736–755. doi: 10.1080/09644016.2010.508305

- Civil Society in Action for Dialogue and Partnership Newsletter 6. Sarajevo: ALDI, 2013.

- Cox, Terry. Interest Representation and State-Society Relations in East Central Europe. Aleksanteri Papers. Helsinki: Kikimora Publications, 2012.

- Dagnino, Evelina. “Civic Driven Change and Political Projects.” In Civic Driven Change: Citizen’s Imagination in Action, edited by Alan Fowler and Kees Biekart, 27–49. The Hague: Institute of Social Studies, 2008.

- Daguda, Aida, Milan Mrđa, and Slaviša Prorok. Annual Financial Reports of Civil Society Organizations in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo: CPCD, 2013.

- Dahl, Robert A. Who Governs? Democracy and Power in an American City. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005.

- Dolenec, Danijela. Democratic Institutions and Authoritarian Rule in Southeast Europe. Colchester: ECPR Press, 2013.

- Donais, Timothy. Peacebuilding and Local Ownership: Post-Conflict Consensus-Building. Oxon: Routledge, 2012.

- Donais, Timothy. The Political Economy of Peacebuilding in Post-Dayton Bosnia. London: Routledge, 2005.

- Fagan, Adam. “Civil Society and ‘Good Governance’ in Bosnia- Herzegovina and Serbia: An Assessment of EU Assistance and Intervention.” In Civil Society and Transitions in the Western Balkans, edited by Vesna Bojicic-Dzelilovic, James Ker-Lindsay, and Denisa Kostovicova, 47–70. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

- Flick, Uwe. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. 4th ed. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2009.

- Fowler, Alan, and Kees Biekart. “Civic Driven Change.” In Civic Driven Change: Citizen’s Imagination in Action, edited by Alan Fowler and Kees Biekart, 17–25. The Hague: Institute of Social Studies, 2008.

- Fowler, Alan, and Kees Biekart. “Relocating Civil Society in a Politics of Civic-Driven Change.” Development Policy Review 31, no. 41 (2013): 463–483. doi:10.1111/dpr.12015.

- Godišnji Izvještaj. 2007. [Annual Report 2007]. Banja Luka: Udružene žene, 2007.

- Guliyev, Farid. “Personal Rule, Neopatrimonialism, and Regime Typologies: Integrating Dahlian and Weberian Approaches to Regime Studies.” Democratization 18, no. 3 (2011): 575–601. doi:10.1080/13510347.2011.563115.

- Howell, Jude, and Jenny Pearce. Civil Society and Development: A Critical Exploration. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2001.

- Hromadžić, Azra. “Discourses of Integration and Practices of Reunification at the Mostar Gymnasium, Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Comparative Education Review 52, no. 4 (2008): 541–563. doi: 10.1086/591297

- Kostovicova, Denisa. “Civil Society in Post-Conflict Scenarios.” In International Encyclopedia of Civil Society, edited by Helmut Anheier, Stefan Toepler, and Regina List, 371–376. New York: Springer Science, 2010.

- Labour Force Survey. Sarajevo: Agency for Statistics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2014.

- Leonardsson, Hanna, and Gustav Rudd. “The ‘Local Turn’ in Peacebuilding: A Literature Review of Effective and Emancipatory Local Peacebuilding.” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 5 (2015): 825–839. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1029905.

- Long, Norman. Development Sociology: Actor Perspectives. New York: Routledge, 2001.

- Mac Ginty, Roger, and Oliver P Richmond. “The Local Turn in Peace Building: A Critical Agenda for Peace.” Third World Quarterly 34, no. 5 (June 2013): 763–783. doi:10.1080/01436597.2013.800750.

- Memorandum O Razumjevanju I Suradnji [MOU]. Udružene žene, 2005.

- Millar, Gearoid. “Disaggregating Hybridity: Why Hybrid Institutions Do Not Produce Predictable Experiences of Peace.” Journal of Peace Research 51, no. 4 (March 19, 2014): 501–514. doi:10.1177/0022343313519465.

- Ngin, Chanrith, and Willemijn Verkoren. “Understanding Power in Hybrid Political Orders: Applying Stakeholder Analysis to Land Conflicts in Cambodia.” Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 10, no. 1 (2015): 25–39. doi:10.1080/15423166.2015.1009791.

- Olson, Mancur. The Logic of Collective Action: Public Good and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971.

- Paffenholz, Thania, and Christoph Spurk. Civil Society, Civic Engagement, and Peacebuilding. Social Development Papers. Washington, DC: World Bank, 2006.

- Petrova, Tsveta, and Sidney Tarrow. “Transactional and Participatory Activism in the Emerging European Polity: The Puzzle of East-Central Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 40, no. 1 (January 1, 2007): 74–94. doi:10.1177/0010414006291189.

- Pogodda, Sandra, and Oliver P. Richmond. “Palestinian Unity and Everyday State Formation: Subaltern ‘Ungovernmentality’ Versus Elite Interests.” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 5 (2015): 890–907. doi:10.1080/01436597.2015.1029909.

- Reilly, Rosemary C. “Process Tracing”. In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research, edited by Albert J. Mills, Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, 735–737. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2010. doi:10.4135/9781412957397.n272.

- Richmond, Oliver P. “Liberal Peacebuilding in Timor Leste: The Emperor’s New Clothes?” International Peacekeeping 15, no. 2 (2008): 185–200. doi: 10.1080/13533310802041436

- Richmond, Oliver P. “Resistance and the Post-Liberal Peace.” Millennium – Journal of International Studies 38, no. 3 (May 10, 2010): 665–692. doi:10.1177/0305829810365017.

- Richmond, Oliver P. “Critical Agency, Resistance and a Post-Colonial Civil Society.” Cooperation and Conflict 46, no. 4 (December 2, 2011): 419–440. doi:10.1177/0010836711422416.

- Richmond, O. P., and J. Franks. “Liberal Hubris? Virtual Peace in Cambodia.” Security Dialogue 38, no. 1 (2007): 27–48. doi:10.1177/0967010607075971.

- Segert, Dieter, and Vedran Džihić. “Lessons from ‘Post-Yugoslav’ Democratization: Functional Problems of Stateness and the Limits of Democracy.” East European Politics and Societies 26, no. 2 (2012): 239–253. doi: 10.1177/0888325411406436

- Služba za društvene djelatnosti. Strategija Prema Mladima Općine Novo Sarajevo Sa Akcionim Planom 2012–14. Sarajevo, 2012.

- Službeni Gasnik RS [RS Official Gazette] 25,62,71. Banja Luka: NS RS, 2013.

- TACSO. Assessment Report on Advocacy Capacity of Membership Based CSOs in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo: TACSO, 2012.

- Tilly, Charles. Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Truman, David Bicknell. The Governmental Process: Political Interests and Public Opinion. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1951.

- UNDP. The Ties That Bind: Social Capital in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo: UNDP, 2009.

- Verba, Sidney, Robert O Keohane, and Gary King. Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994.

- Welzel, Christian, Ronald Inglehart, and Franziska Deutsch. “Social Capital, Voluntary Associations and Collective Action: Which Aspects of Social Capital Have the Greatest ‘civic’ Payoff?” Journal of Civil Society 1, no. 2 (2005): 121–146. doi: 10.1080/17448680500337475

- Where Are Women in Governments? Human Rights Papers. Sarajevo: Sarajevo Open Center, 2015.

- Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research : Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications, 2003.

- Zürcher, Christoph. “Building Democracy While Building Peace.” Journal of Democracy 22, no. 1 (2011): 81–95.