ABSTRACT

Democracy as a form of civilian rule must navigate a path between clerical and military powers, both of which are highly engaged in the politics of post-Mubarak Egypt. The authors ask in this article how mass support for democracy changed in Egypt between 2011 and 2014, and how this support is connected with views on religion and the role of the military. This question is important for understanding the prospects for democracy in a major state in the Arab world. It is also of comparative interest because of what change in the social and ideological drivers of mass attitudes may tell us about the nature of democratic support more generally. The authors’ analysis is based on nationally representative surveys of Egyptians in 2011 after the country’s first post-Mubarak parliamentary elections and in 2014 after the removal of the Islamist President Morsi. The findings indicate that Egyptians in large numbers favour both democracy and unfettered military intervention in politics. The authors also observe important shifts in the social bases of support for democracy away from religion but also from economic aspiration. Negative political experience with democratic procedures in 2011–2013 seems to be the strongest factor behind the observed decrease in democratic support.

1. Introduction

Democracy is a form of civilian rule that establishes a public space between the rule of the clergy and the military – between Scylla and Charybdis. The precise balance of these forces is of course a matter of historical negotiation and may vary considerably across countries. But we see in Egypt an example of extreme pressures from the military and religion. So, we ask whether the contours of mass democratic support provide a map for navigating the country to civilian control and how this map may have changed between 2011 and 2014.

In 2011, following the mass protests in Tahrir Square, democratic aspirations were strongly expressed by a range of political and social actors, including those of political Islamists such as the Muslim Brotherhood, who saw democracy as a means to achieve their own objectives. At the same time, democratic aspirations were also evident among young, educated and aspirational sections of society – the “usual suspects” of modernization – who saw in democracy a means of economic and political advancement. In 2014, by contrast, following the removal of the democratically elected Islamist President Morsi by a combination of mass mobilization and army support in 2013, profound questions emerged about whether mass support for democracy in the country had been sustained. On the one hand, given the evidence of significant shifts in the ideology, strategy and organization of the Muslim Brotherhood,Footnote1 might we not expect that followers of political Islam would defect from democratic support, having seen their president removed, their movement banned and in many cases their members imprisoned? On the other hand, might we not also expect that those “usual suspects”, who favoured democracy but who opposed the Islamists, would defect, having seen the (to them) negative consequences of the Muslim Brotherhood winning power through the ballot box and the necessity of Morsi’s removal? And with such forces potentially defecting, who, in short, might be left a democrat in Egypt to steer between the Scylla of Islamist rule and the Charybdis of the military?

Our study takes in two crucial time points in Egypt’s post-Mubarak politics. We gain our first view of mass support for democracy in 2011, in a survey conducted immediately following the December 2011/January 2012 parliamentary elections. We then compare these views with the results of other surveys conducted in 2014 after Morsi’s removal.

Our findings point to the fragility of democracy and of democrats in Egypt. First, so far as the civilian character of democracy benefits from the aspirations and commitments of the young, educated and middle classes (and of women), this base appears to have eroded over time. Negative experience of democracy appears to be the strongest approach in explaining this decrease in democratic support. Second, so far as the potential for achieving goals through the ballot box might cement Islamists into the democratic process, this too appears to have been undercut. But, third, if the Scylla of Islamist rule appears to have been avoided, Egyptians still appear to feel the lure of Charybdis, given high levels of mass support for unfettered military intervention.

The article proceeds as follows. We first give readers a clear sense of the direction of public attitudes towards democracy as they evolved between 2011 and 2014. The following section presents theoretical insights on how support for either military or Islamist rule shrinks the space for a fully functioning democratic system. It then lays out the main trends in the literature on what explains support for democracy. The fourth section moves the debate to Egypt. It analyses how support for political Islam and military rule have traditionally evolved in Egypt, their historical and structural explanations, and how eventually both pressures can create puzzling contradictions in views on democratic support. The fifth section presents our argument that negative experience of democratic practice since 2011 has played a crucial role in affecting attitudes towards democracy among Egyptians. The sixth section tests our hypotheses about the drivers of democratic support using data from two surveys conducted in Egypt in 2011/2012 and 2014.

2. The trajectory of support for democracy, the military and Islamism in Egypt, 2011–2014

We begin by showing the results of a series of questions we asked of nationally representative samples of Egyptians in mass surveys designed by the authors in Egypt in 2011 and 2014 (see ). The changes we observe over these waves provide a significant motivation for our research question. All surveys had the same core questions (see Appendix 1). For the first face-to-face survey in 2011, the authors designed an extensive questionnaire of roughly 35 minutes with a nationally representative sample of 2000 individuals drawn from the electorate. The sample was determined using census data and targeted only those citizens aged 18 or over who were eligible to vote in the 2011 parliamentary elections.Footnote2

Table 1. Details of the surveys.

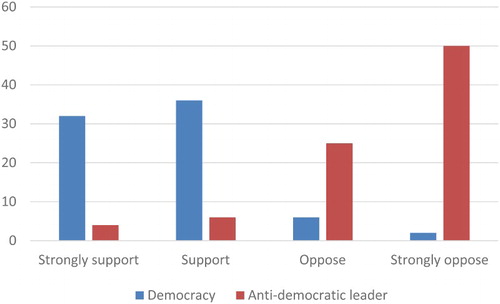

We drew on two ways to measure support for democracy. The first was asking the straightforward question: Tell us please, do you think that democracy, in which multiple parties compete for power through free elections, is the best system for governing Egypt? The second was to ask about attitudes towards limitation on democracy: Do you think that it would be worthwhile to support a leader who could solve the main problems facing Egypt today even if he overthrew democracy? Especially in the Arab World, previous research indicates that such limitation reveals some anti-democratic attitudes opposite to those expressed in response to the straightforward question.Footnote3 Responses to these questions in 2011 are summarized in and reveal a very high level of support for normative democracy and relatively low level of support for an anti-democratic leader.

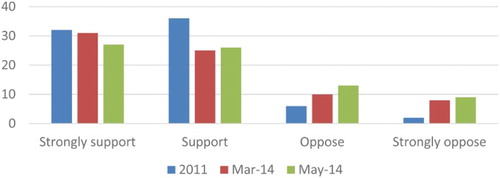

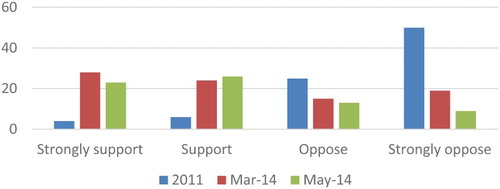

Given the significant developments that took place after 2011 (discussed in Sections 4 and 5), two subsequent waves of the same questionnaire were conducted in April 2014 and June 2014. The interesting question was whether or not Egyptian public opinion would hold on the lines of 2011. If not, in what directions would it break? Would support for democracy in Egypt plummet for the reasons we outlined above? And how would views regarding religious leaders and the military interact with democratic support? The results are shown in .

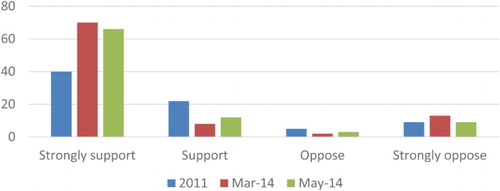

As expected, we find very significant changes in public attitudes to politics and the role of religion in our data after the 2011 survey. Attitudes were relatively stable in the two surveys in 2014. While support for democracy as a system remains high overall (), it does clearly fall, and this goes along with a big increase in support for – and more particularly a huge fall in opposition to – anti-democratic leadership (). At the same time, we find overwhelming support for military intervention in politics (), even when the question was posed to respondents to allow maximum discretion to the military to decide when to intervene (that is, “the military should intervene in politics whenever it considers necessary”). Strikingly, although support was already high in 2011 for unfettered military intervention (40%), by 2014 the level had increased to well over 60%, with almost no opposition. So, we appear to see a shift away from democracy towards the Charybdis of military rule. Similar trends of decreasing democratic support between 2011 and 2013 were found among Egyptian Twitter users, a significant percentage of whom are Egyptian youth.Footnote4

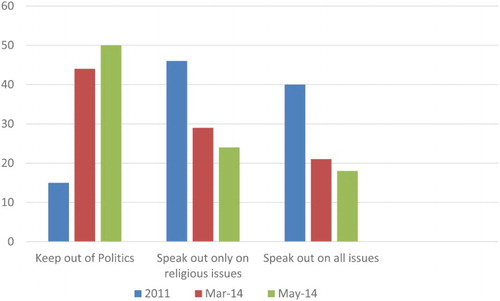

So far as religion is concerned, however, the shift appears to be away from Scylla, as shows. Between 2011 and 2014, there was a huge decrease in the number of those who believe that religious leaders should speak out on all issues, including political matters (from 40% in 2011 to around 20% in 2014). There was a correspondingly large increase in those who say that religious leaders should stay out of politics altogether (from 15% in 2011 to 50% in 2014).

In short, therefore, we find mixed evidence for the emergence of a space of democratic civilian rule: certainly, the role for religious intervention appears to have weakened; but the role for military intervention has expanded considerably. Support for democracy itself has also fallen. An interesting question is what could explain such attitudes and what this tells us about drivers for support for democracy in Egypt post-2011. In the next section, we theorize how to explain public attitudes towards democracy in light of both comparative theory and the Egyptian experience.

3. Theorizing support for democracy in a comparative context

It is by now a truism to say that the meaning of democracy is strongly contested, most prominently between narrow and broad conceptions of the conditions required for its existence and stability,Footnote5 the role of elites and mass participation,Footnote6 and the importance of institutional design versus democratic culture.Footnote7 Similarly, there is no shortage of debate about what drives support for democracy at the mass level, not least again prior cultural commitments and institutional congruence,Footnote8 economic modernization,Footnote9 economic performance,Footnote10 and successful representation.Footnote11

Two matters are less contested in the literature, however. First, there is little disagreement that mass normative support for democracy as a system is a powerful factor for democratic survival,Footnote12 even if that support may in part be driven by how democracies perform in practice. In Egypt, therefore, where democracy has certainly faced huge challenges in the years since the ousting of Mubarak, it is important to establish whether there is a reservoir of normative commitment to democracy given its experience of democratic institutions.

Second, there is little disagreement about the need for democracy to carve a space for civilian rule via elected and accountable institutions. In short, the people constituted as a demos must be integrally involved either directly in making authoritative judgments or must be the principal that establishes a set of political agents to take decisions on its behalf, subject to regular account. Democracy as rule by the people – in its multiple and contested forms – can therefore easily be contrasted with alternative sources of political authority, of which two are of particular relevance in the Egyptian context.

On the one hand, strong claims to authority are made by Islamists on the basis of religious texts and laws. Central to such claims is the argument that “Islam is a religion and state”. That is, Islamic religious texts also contain clear rules on worldly matters such as regulation of social life, inheritance, penal code, and others.Footnote13 Thus, the “Islamist” state can be a moral actor responsible for social transformation.Footnote14 Such argument, however, could be used to restrict democracy in many ways. First, although this reduction of complicated matters of government and politics into dualities of right and wrong can help mobilize followers, it greatly expands the sphere of governance that is not subject to political debate and majority rule. Second, political Islam could also carry the risk that Islamist parties could seek democratically to end democracy by moving gradually towards clerical rule with popular backing (that is, people voting to give up the vote). So far as religion is the ultimate source of power, democracy is – to say the least – constrained. This raises again the question asked by Alfred Stepan in his seminal paper on the “twin tolerations” about the mutual respect of religion and the political sphere that is required for a fully functioning democracy.Footnote15

On the other hand, the military has its own claims to exercise power. Throughout history, we have seen armies enforcing their own authority structures, often through justification of ensuring stability or as a source of development. The majority of existing literature assumes that any political role for the military works against the democratic ideal through several mechanisms. First, the military’s imposition of reserve domains on elected governments usually obstructs the functioning of a democratic systemFootnote16 making it antithetical to core principles of the Madisonian system.Footnote17 Second, civilian control of the military has been one of the cornerstones of measurements and definitions of democracy. Dahl’s definition of democracy,Footnote18 for example, stipulated that control over government decisions about policy should be constitutionally vested in elected officials, whereas Huntington has argued that the objective civilian control of the military requires making them the tool of the state.Footnote19 So far as the military is the ultimate source of power, therefore, we can equally say that democracy is constrained.

We refer to the need for civilians to exercise power via democratically elected and accountable institutions (of whatever sort) as when the demos has successfully navigated a course between the Scylla of religious rule and the Charybdis of military rule. All consolidated democracies have managed this course, albeit with varying degrees of religious and military involvement in political life. But many transitional democracies have struggled to find a balance and have either slipped back into clerical rule (for example, Iran) or into military dominance (for example, Pakistan).

What, however, may shape the democratic attitudes of citizens in ways that may engender the emergence of a civilian space in which the institutions of the demos rule? Or, alternatively, what may incline citizens not to respond to the pulls of Scylla or Charybdis? Here, in fact, the comparative literature on the sources of democratic support may be of considerable help. We identify three principal schools of thought regarding what drives democratic support.

The first emphasizes economic factors. Traditionally, this view rests on the mid-twentieth century modernization school which saw rising living standards and the growth of private ownership and urban middle classes as constituting the main forces leading citizens to support democratic procedures for the resolution of social conflictFootnote20 or as a factor that helps prevent new democratic experiments from regressing towards authoritarianism.Footnote21 From this perspective, the chances of Islamist or army rule will be reduced in Egypt as long as the “usual suspects” of secular modernization – young, educated, aspirational forces who anticipate that democracy can deliver economic gains – can play a pivotal role in the design and maintenance of the country’s political institutions.

The second school of thought stresses the primacy of political rather than economic factors. According to this view, effective political institutions and interest representation are likely to produce positive perceptions of the functioning of democracy among the electorate. The key factors underlying popular support for democracy would be the performance of new political institutions and the ability of electors to be heard via the party and electoral systems.Footnote22 Closely related to this argument is an argument that attributes high levels of democratic support in non-democratic countries to dissatisfaction with the failures of authoritarianism.Footnote23 Both these perspectives would speak to the Egyptian situation if support for democracy came from those who negatively recall the authoritarian past under Mubarak and/or who positively evaluate democracy in Egypt since Mubarak’s ousting. The difficulties that this may pose for democratic support, however, are obvious: memories of the Mubarak past may fade or even generate positive nostalgia so far as the democracy of the Morsi period is perceived to have failed.

The third view, often specifically directed towards the Arab World, is a culturalist one. At its broadest,Footnote24 it asserts that the fit of the political culture, considered as the “foci of identification and loyalty”,Footnote25 with national institutions plays a decisive role in generating support for a democratic regime and its performance. In the Islamic and Arab worlds, this perspective has gained particular traction via arguments that some elements of Islamic or Arab cultures run counter to the values required for democracy and, instead, contribute to the entrenchment of authoritarian regimes, either because they promote fatalism and the acceptance of the status quo or fail to advocate a commitment to political freedom.Footnote26 Another culturalist argument is that Islam fosters a blind acceptance of authority.Footnote27 Finally, as we have argued regarding Scylla, some contend that Islam and democracy are inherently incompatible because Islam does not recognize any division between “church” and “state” and emphasizes the community over the individual.Footnote28 Some scholars assert that Islamic law and doctrine are fundamentally illiberal and hence create an environment within which democracy cannot flourish.Footnote29 Certainly, these claims about Islamic and Arab culture have also been strongly contested,Footnote30 and studies employing different measures or model specifications found no incompatibility between Islam and democracy.Footnote31 But, if such an approach is relevant to the case of popular support for democracy in Egypt, then Egyptians’ views of the role of religion in politics may make it less likely that a civilian demos will emerge.

In Egypt, however, along with these potential drivers, the Scylla of political Islam and Charybdis of military rule had their own counter pulls. These are analysed in the next section before our argument is presented.

4. Sources of the Islamist and military appeals in Egypt

Political Islam was a major political force in Egypt for most of the twentieth century. Ever since its official start through the establishment of the Muslim Brotherhood in 1928, however, it has been an opposition force, albeit the longest serving and strongest opposition force in the country. Despite some periods of mutual tolerance between the Brotherhood and the incumbent regime – most notably in the late 1970s under Sadat – political Islam presented itself as the more pious alternative to a corrupt authoritarian incumbent regime.Footnote32 The abrupt interruption of the regime in February 2011 thus provided a significant opportunity for the Brotherhood to rise from decades of underground activity to the surface of public and political space, an opportunity it was expected to seize in full. It was only in 2011 that the Muslim Brotherhood – and even Salafist movements – launched, for the first time, political parties that were legally recognized. Both then moved quickly to win around 70% of the seats in the first post-Mubarak legislative elections and later the presidency by the Brotherhood in 2012.

The reasons why the electoral and political horizon was wide open for Islamists in 2011 and 2012 were several. First, organizationally they were much stronger than their secular rivals.Footnote33 Since the 1980s, the Brotherhood had managed to create strongholds in professional syndicates, civil society institutions and university student unions in a manner that helped them create an organizational network of supporters – or at least sympathizers. Their associated clinics and schools were also part of that wide network,Footnote34 which paid off when free parliamentary elections were finally held in 2011. Second, Islamists were also better funded than secular parties, partly through a system of communal fundingFootnote35 and partly through their associated organizations outside Egypt.Footnote36 Conversely, Egypt’s secular forces largely lacked funding. Whereas businesses in the period before 2011 were either pro-regime – as a means to protect their interests – or politically inactive, the middle classes and other sectors of society had difficulty funding the kinds of activities needed to sustain politically viable organizations.

The electoral and political gains of Islamists have put pressure on the democratic transition.Footnote37 On the one hand, very early in the transition, the sudden rise of Islamists confronted Egyptians with one of the most difficult questions in any nation’s path towards democracy: where should religion be positioned in the political system of an Islamic country and – more importantly – what are the limits on majority rule? Indeed, Egyptians found themselves at the heart of heated debates ranging from weighty issues such as the permissibility under Islam of interest on International Monetary Fund loans to trivial issues such as whether or not Muslims can congratulate Copts on their religious holidays. Eventually, the 2012 constitution placed serious limits on majority rule.

So far as the military is concerned, it also had strong appeal. First, the political landscape immediately following Mubarak’s removal was indeed one where the party system could hardly provide the basis for stable democratic competition. With both parliamentary chambers dissolved, the former ruling National Democratic Party outlawed by a court order, its local leaders given several signals to stay out of politics, and other secular opposition parties weakened by the authoritarian era, there were few credible political forces left on the ground. Relevant literature does argue for a stabilizing role for the military in cases where other institutions designed to preserve and promote democracy and stability are absent.Footnote38 At such times, fragile democracies may need to retain undemocratic elements to guard against democratic breakdown.Footnote39

The second reason draws more strongly from Egypt’s historical trajectory since the 1952 revolution, a point after which the military became a strategic political and economic player, enabling it to be a symbol of stability and continuity at times of uncertainty. In addition, the country’s involvement in several regional wars also gave special status to its military in the nation’s psyche.Footnote40 The military also positions itself as a significant economic player, owning companies that stretch from the construction sector to consumer goods in addition to its own military industry.Footnote41 All these factors have contributed to making Egypt’s military one of the strongest political players in the nation’s recent history. Theoretically, public support for the military could also stem from characteristics specific to the military itself, including its egalitarian institutions if composed of citizen-soldiers, and its traditional focus on external, not internal, threats. Both features tend to apply to the Egyptian military.Footnote42 Such comparative advantages enjoyed by the military led even some civil society activists to support the takeover by the Supreme Council for the Armed Forces in February 2011, preferring “a military junta not unlike the one that seized power in 1952”.Footnote43

5. The significant role of political experience

Our main argument is that political experience – positive or negative – with democracy is likely to play a significant role in generating support for democracy in principle, particularly in new democracies where diffuse supportFootnote44 has not yet been inculcated in the minds of citizens.

The vast majority of survey-based literature in the Arab World conducted before the Arab Spring paints a general picture in which Arab peoples across the Arab World are pro-democracy. Arab Barometer data, for example, reveal that 86% of those interviewed believe that democracy is the best form of government, and 90% agree that democracy would be a good or very good system of governance for the country in which they live.Footnote45 Such observations were reiterated in several surveys, giving the impression that, by the time the Arab Spring made headway in some Arab countries, public support for democracy was high.

In Egypt, however, most of what has taken place on the democratic front since 2011 is likely to affect judgement-based democratic attitudes negatively. On the one hand, although Egyptians were called to take part in several voting processes, either to ratify constitutional drafts (three times) or to elect a president (twice) or a legislative chamber (twice), such processes led to increased divergence between Islamists, liberals and supporters of the military. Within each of those camps, there were even further divisions. The Islamist camp was divided between the Salafists and the Muslim Brotherhood, the liberals between leftist, Nasserist forces and right-wing pro-market liberals, and supporters of the military between the sympathizers with and opponents of the Mubarak regime.

Moreover, elections made little progress towards settling the deep divisions or the most controversial questions. On the one hand, despite successive election victories by the Islamists, this hardly stopped mass – and sometimes violent – protests against them, before and during the Morsi presidency. On the other hand, although the 2012 constitution was written by an indirectly elected assembly and ratified in a public referendum (widely judged to be free and fair), it granted religious bodies powers over elected legislatures and excluded almost all members of the Mubarak elite from the political process. It was also boycotted by liberals who claimed it was creating a theocracy.

Elected bodies also had little effect on the lives of ordinary Egyptians. The Egyptian parliament elected in 2011/2012 was dissolved before it passed any consequential laws. Moreover, the upper chamber – which remained in office after the lower chamber was dissolved and took over full legislative powers in 2013 – could hardly be labelled a transformative legislature.Footnote46 One of the strongest indicators of the lower chamber’s weak popular acceptance was the fact that its dissolution did not spark any strong protests.

The performance of Mohammed Morsi, the first democratically elected president after Mubarak’s removal, could also be argued to have contributed to negative perceptions of democracy. Elected with a slim majority of just 1%, he made little attempt to unite a divided country. Instead, he further polarized opinions, disregarding many of the demands made by the liberal opposition for a less Islamist-dominated constitution-writing process, and predominantly fielded Brotherhood figures in posts over which he had the power of appointment.

A final blow to democratic practice came with the removal of Morsi. Muslim Brotherhood supporters seeing their president removed, the constitution they worked hard to write annulled and being confronted with one of the most serious crackdowns against them in their almost 90 years of history are all factors that probably negatively affected their support for democracy. Negative experience with democratic procedures was thus a mechanism that had the potential to affect democratic attitudes of both liberals and Islamists.

It is important to note, moreover, that all these negative political developments happened against the backdrop of deteriorating socio-economic conditions. Unemployment increased from below 9% in 2010 to around 13% in 2012, 2013 and 2014. Gross domestic product growth rates decreased from above 5% in 2010 to an average of 1–2% in the three subsequent years. The local currency lost more than one-third of its value against the US dollar between 2011 and 2014, leading to double-digit inflation.Footnote47

How, then, might these experiences with democracy in practice and with the pulls of Scylla and Charybdis in Egypt fit with the dynamics of support for democracy as an ideal system of government for the country? And, most saliently, have the political and economic experiences of Egyptians between 2011 and 2014 resulted in shifts in what inclines citizens to support democracy? We have a number of clear concerns. First, we expect that the negative political experience of this period will have led to an overall fall in democratic support. Unlike established democracies, in Egypt, we do not expect that democracy can rely on a reservoir of diffuse supportFootnote48 where there is a deep-seated set of attitudes towards politics and the operation of the political system that is relatively impervious to change. The result is the likelihood of performance-based judgements of democracy, making such support to some extent conditional on what democracy delivers.Footnote49

Second, we expect that some citizens are more likely to have defected from democracy. In particular, we expect reduced support from two sides: from those political Islamists who can no longer see the possibility of achieving their goals through the ballot box after the forcible removal of Morsi and the banning of their party; and from those “usual suspects” who see democracy in practice as failing to achieve their hopes for economic and social modernization.

Third, we expect that support for the intervention of the army will have grown significantly. In essence, a belief in a political role for the military negatively affects support for democracy because it reserves for the military the power to intervene in what is seen as a failing democratic game. The appeal of the army may be felt especially among those who were previously democrats but who now see the military as a guardian of the state against Islamism and against instability more generally.

6. Data and analyses

We test our expectations regarding the drivers of democratic support drawing on multiple measures from our survey data. Our dependent variable is whether Egyptians support democracy as the ideal system for governing the country, shown in . In line with our theoretical expectations developed above, we next considered what might predict support for democracy among Egyptians in the 2011 survey. To do so, we operationalized each of the likely predictors outlined in the theory section above. (Precise details of the questions are found in Appendix 1.)

The “usual suspects” – age, education, economic circumstances, economic expectations, urban settlement.

Religion and religiosity, views of the role of religion in political life.

Political experience, including efficacy and views of democratic representation.

Views of the role of the military in political life.

We then considered the relationships between each of these predictors and support for democracy using ordinal logistic regression, which is suitable for a dependent variable with ordinal categories of response. The results are shown in .

Table 2. Ordinal logistic regression of the drivers of democratic support among Egyptians in 2011.

We found evidence in 2011 for a number of the democratic support drivers echoed in the relevant literature. There is certainly some evidence for the modernization theory. The more educated, the young and the urban were significantly more supportive of democracy. Note at this point that there are no gender effects of support for democracy. We also found some evidence for economic drivers of democratic support. People who looked back negatively on the old regime for their household and the country but looked forward optimistically to the economic future were stronger supporters of democracy. So, we do find support among the “usual suspects” – those who in a broader comparative context we would expect to support democratic values in part because they expect them to deliver on their modernizing aspirations.

As can be seen from columns 3 and 4 in , however, it is the political experience variables that are most powerful in explaining the variance in support for democracy. As the full model indicates, variables tracing political efficacy (feelings of having political influence, seeing parties as having different policies, seeing a point in voting and opposing military intervention and anti-democratic leaders) and political experience (people feeling positive about democracy in practice in 2011) are more democratic. In line with our expectations, therefore, in the absence of a reservoir of diffuse support, we observe citizens in the then emerging Egyptian democracy to make strong connections between their experience of democracy and their view of it as an ideal system.

Two important points stand out, however, with regard to Scylla and Charybdis. First, Egyptians in 2011 who supported democracy were also significantly more likely to oppose military intervention in politics. One aspect of the relationship of democracy to civilian rule – a restricted sphere for the military – is supported. Second, and by contrast, we do find clear support for an “Islamist” base to democratic support in 2011. Citizens who believe that there should be either no or just some limitations on religious leaders’ intervention in politics are stronger supporters of democracy than those who hold that religious leaders should stay out of politics. It appears that more secular respondents were the least supportive of democracy at that time of the transition – controlling for other factors. The second aspect of civilian rule – the role of religion and religious leaders – therefore is not settled. But the direction of the religious effect is not against democracy per se but towards finding in democracy a means of achieving religious aims.

How then might the shifts between 2011 and 2014 in support for democracy, which we showed in , be explained by shifts in the demographic, economic, religious and political experiences of Egyptians over the same time? To consider this, we tested again the relationships between our theorized predictors and democratic support. As discussed above, our expectations were that support for democracy among both Islamists and the “usual suspects” of modernization would have fallen as both groups lost faith in democracy as a means of achieving their goals.

shows the relationships comparing 2011 with 2014. Because the effects for the two surveys in 2014 are almost identical (analysis available on request), we show regressions for just one survey. The results offer strong evidence for our expectations. The connection of forces of modernization to democracy appears to be on the retreat. Education is no longer a significant predictor of democratic support. Moreover, some of the usual suspects now work in the opposite direction; it is rural and older citizens who have become the stronger supporters of democracy. Finally, we observe the emergence of a significant gender gap – men now stand out as stronger supporters. We also see the failure of democracy as economic aspiration in the minds of Egyptians. It is now not those who have done badly but have higher hopes for the future who are more inclined to support democracy – as was the case in 2011 – but those who have been doing relatively well in the recent past, with no effect at all on expectations for family or country in the future. The relation between holding strong religious views and democracy also largely disappears. It is no longer the case that those who see a significant role for religious leaders in politics are more supportive of democracy – the Islamist effect is fading, although we note that the sign here has not turned negative. Finally, as for attitudes regarding a political role for the military, those opposed to intervention do remain more democratic, confirming our second hypothesis again in 2014, but the strength of the coefficient is now weaker and of less significance. Overall, moreover, we see a great reduction in the strength of all these factors combined in explaining democratic support – from R2 = .23 to .06.

Table 3. Ordinal logistic regression of the drivers of democratic support among Egyptians, 2011–2014 comparison.

7. Conclusion

Our findings point to highly significant changes in Egyptian public opinion in the time between the democratic opening following the removal of Mubarak and the removal of Morsi. Many of our expectations were met: support for democracy has fallen and conditional support for anti-democratic leaders has risen significantly.

With these overall shifts, we also see important changes in the bases of democratic support. Two potentially contradictory groups were distinctly supportive in 2011: Islamists who saw a reason to support democracy as a means to enhance the role of religion in Egyptian politics; and the “usual suspects” of modernization, who saw in democracy a means to advance their economic and other aspirations. Neither of these groups is now distinctive in its support for democracy. Our evidence shows that many of the usual suspects are now less supportive of democracy. At the same time, the organization, strategy and ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood have altered significantly since 2011 and perhaps especially since Morsi’s removal,Footnote50 and democracy is no longer a distinctively Islamist project in the minds of Egyptians. It seems, in fact, that democracy in Egypt now has no distinctive and powerful social base at all.

Although not quite captured by our individual-level survey data, democratic attitudes are likely also to have been influenced by the measures taken in post-Morsi Egypt to organize society and public space, directed mainly against Islamists and 2011 revolutionary forces. In particular, the clampdown against the Muslim Brotherhood’s organizational and financial networks, laws restricting protest and non-governmental organizations’ activities,Footnote51 government closure of some media outlets and buy-outs of others have enabled the government to influence public discourse over democracy. Democratic attitudes have thus probably been negatively influenced by the portrayal of democratic elections as a mechanism for carrying “extremists” to power and the framing of democratic demands as the catalyst for civil wars in neighbouring countries such as Syria, Libya and Iraq.

Egypt therefore appears to have navigated away from the Scylla of Islamist rule. But it has done so only by tacking towards the Charybdis of military rule. If democracy depends on negotiating a position of balance of autonomous space between these two, then it has not yet consolidated in Egyptian public opinion, even if many citizens still place some value upon it as a system of government. However, if, as we show, support for democracy decreases as a result of the poor performance of what is perceived to have been democratic dynamics, then it might also be expected to increase if the less democratic system fares equally badly. In other words, if the current government of President Sisi also fails to deliver economically and suffers from problems of political representation and legitimacy, attitudes towards democracy might also change soon. We see a picture of a fragile democracy and equally fragile democrats.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mazen Hassan

Mazen Hassan is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Cairo University. His research interests include elections and electoral systems, political parties and party systems, democratic transition in Egypt and Arab Spring, experiments and mass surveys.

Elisabeth Kendall

Elisabeth Kendall is Senior Research Fellow in Arabic and Islamic Studies at Pembroke College, University of Oxford. She works on the intersections between cultural and political/militant movements in the contemporary Middle East. Her current interests are in jihadist propaganda through poetry, tribal representation and youth politics in eastern Yemen, and the surge of cultural production inspired by the Arab Spring, particularly in Egypt.

Stephen Whitefield

Stephen Whitefield is a Professor of Politics in the Department of Politics and International Relations and Pembroke College, University of Oxford. His research interests include democratization, electoral behaviour in post-Communist Europe, and party competition across Europe as a whole.

Notes

1 POMEPS, Evolving Methodologies in the Study of Islamism.

2 Owing to restrictions by the Egyptian authorities on conducting face-to-face interviews, subsequent surveys were phone surveys and thus used shorter versions of the original questionnaire so as to limit the number of questions to an average of 20 questions to avoid respondent fatigue over the phone. Respondents were drawn from both landline and mobile phone users, which include 94% of the Egyptian population, and targeted only those citizens aged 18 or over. In all surveys, analysis was weighted to census data demographics for age, sex and the urban–rural divide.

3 Jamal and Tessler, “The Democracy Barometers”.

4 Lynch et al., “Online Clustering, Fear and Uncertainty in Egypt's Transition”.

5 Przeworski, Democracy and the Market; Dahl, Polyarchy.

6 Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Linz and Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation.

7 Diamond, Developing Democracy; Almond and Verba, The Civic Culture.

8 Eckstein and Apter, Comparative Politics.

9 Lipset, “Some Social Requisites of Democracy”.

10 Przeworski et al., Democracy and Development.

11 Evans and Whitefield, “The Politics and Economics of Democratic Commitment”.

12 Easton, “A Reassessment of the Concept of Political Support”; Dalton, “Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies”.

13 Ayubi, Political Islam.

14 Dunne and Radwan, “Egypt: Why Liberalism Still Matters”.

15 Stepan, “Religion, Democracy and the ‘Twin Tolerations’”.

16 Linz and Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation.

17 Turley, “Tribunals and Tribulations”.

18 Dahl, Polyarchy.

19 Huntington, The Soldier and the State.

20 Lipset, “Some Social Requisites of Democracy”.

21 Przeworski et al., Democracy and Development.

22 Evans and Whitefield, “The Politics and Economics of Democratic Commitment”.

23 Jamal and Tessler, “The Democracy Barometers”.

24 Almond and Verba, The Civic Culture.

25 Brown, “Introduction,” 1.

26 Kedourie, Democracy and Arab Political Culture.

27 Fish, “Islam and Authoritarianism”.

28 Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order.

29 Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man.

30 Abou Fadl, Islam and the Challenge of Democracy; Esposito and Voll, Islam and Democracy; Nasr, “The Rise of ‘Muslim Democracy’?”; Jamal, “Reassessing Support for Democracy and Islam in the Arab World”.

31 Przeworski et al., Democracy and Development; Elbadawi and Makdisi, Democracy in the Arab World.

32 Wickham, Mobilizing Isla; Fuller, The Future of Political Islam.

33 Masoud, Counting Islam; Trager, “The Unbreakable Muslim Brotherhood”.

34 Ismail, “The Paradox of Islamist Politics”; Bayat, “Activism and Social Development in the Middle East”.

35 Munson, “Islamic Mobilization”.

36 Mandaville, Global Political Islam; Denoeux, “The Forgotten Swamp”.

37 Hamzawy, “On Religion, Politics and Democratic Legitimacy in Egypt, January 2011–June 2013”.

38 Przeworski, “Some Problems in the Study of the Transition to Democracy”.

39 Issacharoff, “Fragile Democracies”.

40 Karawan, “Politics and the Army in Egypt”.

41 Harb, “The Egyptian Military in Politics”; Marshall and Stacher, “Egypt's Generals and Transnational Capital”; Sayigh, Above the State; Frisch, “The Egyptian Army and Egypt's ‘Spring’”.

42 Varol, “The Military as the Guardian of Constitutional Democracy”.

43 Masoud, “The Upheavals in Egypt and Tunisia,” 25.

44 Easton, “A Reassessment of the Concept of Political Support”; Benstead, “Why Do Some Arab Citizens see Democracy as Unsuitable for their Country?”.

45 Jamal and Tessler, “The Democracy Barometers”.

46 Polsby, “Legislatures'.

47 Data taken from periodic reports by the Central Bank of Egypt. For more information, see http://www.cbe.org.eg/English/.

48 Easton, “A Reassessment of the Concept of Political Support”.

49 For African democracies, see Bratton, “Wide but Shallow”; for Eastern Europe, see Evans and Whitefield, “The Politics and Economics of Democratic Commitment”.

50 POMEPS, Evolving Methodologies in the Study of Islamism.

51 In 2016, however, this law was ruled as unconstitutional by the Constitutional court and was amended by parliament.

Bibliography

- Abou Fadl, Khaled. Islam and the Challenge of Democracy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004.

- Almond, Gabriel, and Sidney Verba. The Civic Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1963.

- Ayubi, Nazih. Political Islam: Religion and Politics in the Arab World. London: Routledge, 1991.

- Bayat, Asef. “Activism and Social Development in the Middle East.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 34, no. 1 (2002): 1–28.

- Benstead, Lindsay J. “Why Do Some Arab Citizens See Democracy as Unsuitable for their Country?” Democratization 22, no. 7 (2015): 1183–1208. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2014.940041

- Bratton, Michael. “Wide but Shallow: Popular Support for Democracy in Africa.” Afrobarometer Paper No. 19, Cape Town, 2002.

- Brown, Archie. “Introduction.” In Political Culture and Political Change in Communist States, edited by Archie Brown and Jack Gray, 1–24. London: Macmillan, 1977.

- Dahl, Robert. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1971.

- Dalton, Russell J. “Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies.” In Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Governance, edited by Pippa Norris. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Denoeux, Guilain. “The Forgotten Swamp: Navigating Political Islam.” In Political Islam: A Critical Reader, edited by Frederic Volpi, 55–79. London: Routledge, 2012.

- Diamond, Larry. Developing Democracy: Toward Consolidation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

- Dunne, M., and T. Radwan. “Egypt: Why Liberalism Still Matters.” Journal of Democracy 24, no. 1 (2013): 86–100. doi: 10.1353/jod.2013.0017

- Easton, David. “A Reassessment of the Concept of Political Support.” British Journal of Political Science 5 (1975): 435–437. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309

- Eckstein, Harry, and David Apter, eds. Comparative Politics: A Reader. London: Free Press of Glencoe, 1963.

- Elbadawi, Ibrahim, and Samir Makdisi. Democracy in the Arab World: Explaining the Deficit. London and New York: Routledge, 2011.

- Esposito, John, and John Voll. Islam and Democracy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Evans, Geoffrey, and Stephen Whitefield. “The Politics and Economics of Democratic Commitment; Support for Democracy in Transition Societies.” British Journal of Political Science 25 (1995): 485–514. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400007328

- Fish, Steven. “Islam and Authoritarianism.” World Politics 55, no. 1 (2002): 4–37. doi: 10.1353/wp.2003.0004

- Frisch, Hillel. “The Egyptian Army and Egypt’s “Spring”.” Journal of Strategic Studies 36, no. 2 (2013): 180–204. doi: 10.1080/01402390.2012.740659

- Fukuyama, Francis. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Avon, 1992.

- Fuller, Graham. The Future of Political Islam. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004.

- Gellner, Ernest, ed. Islamic Dilemmas: Reformers, Nationalists, and Industrialization—The Southern Shore of the Mediterranean. New York: Mouton, 1985.

- Harb, Imad. “The Egyptian Military in Politics: Disengagement or Accommodation?” Middle East Journal 57, no. 2 (2003): 269–290.

- Huntington, Samuel. The Soldier and the State, The Theory and Politics of Civil-Military Relations. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1957.

- Huntington, Samuel. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996.

- Ismail, Salwa. “The Paradox of Islamist Politics.” Middle East Report 31, no. 221 (2001): 34–39. doi: 10.2307/1559338

- Issacharoff, Samuel. “Fragile Democracies.” Harvard Law Review 120, no. 6 (2007): 1405.

- Jamal, Amaney. “Reassessing Support for Islam and Democracy in the Arab World?: Evidence From Egypt and Jordan.” World Affairs 169 (2006): 51–63. doi: 10.3200/WAFS.169.2.51-63

- Jamal, Amaney A., and Mark A. Tessler. “The Democracy Barometers: Attitudes in the Arab World.” Journal of Democracy 19, no. 1 (2008): 97–110. doi: 10.1353/jod.2008.0004

- Karawan, I. “Politics and the Army in Egypt.” Survival: Global Politics and Strategy 53, no. 2 (2011): 43–50. doi: 10.1080/00396338.2011.571009

- Kedourie, Elie. Democracy and Arab Political Culture. Washington, DC: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1992.

- Lewis, Bernard. The Shaping of the Modern Middle East. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Linz, Juan, and Alfred Stepan. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

- Lipset, Seymour M. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” American Political Science Review 53 (1959): 69–105. doi: 10.2307/1951731

- Lutterbeck, Derek. “Arab Uprisings, Armed Forces, and Civil–Military Relations.” Armed Forces & Society 39, no. 1 (2013): 28–52. doi: 10.1177/0095327X12442768

- Lynch, Marc, Deen Freelon, and Sean Aday. “Online Clustering, Fear and Uncertainty in Egypt’s Transition.” Democratization (2017). doi:10.1080/13510347.2017.1289179.

- Mandaville, Peter. Global Political Islam. London: Routledge, 2007.

- Marshall, Shana, and Joshua Stacher. “Egypt’s Generals and Transnational Capital.” Middle East Report 262 (2013): 12–18.

- Masoud, Tarek. “The Upheavals in Egypt and Tunisia: The Road to (and from) Liberation Square.” Journal of Democracy 22, no. 3 (2011): 20–34. doi: 10.1353/jod.2011.0038

- Masoud, Tarek. Counting Islam. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Munson, Ziad. “Islamic Mobilization: Social Movement Theory and the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood.” The Sociological Quarterly 42, no. 4 (2001): 487–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2001.tb01777.x

- Nasr, Seyyed Vali Reza. “The Rise of ‘Muslim Democracy’?” Journal of Democracy 16 (April 2005): 13–27. doi: 10.1353/jod.2005.0032

- Polsby, Nelson. “Legislatures.” reprint In Legislatures, edited by Philip Norton. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990, 1975.

- POMEPS. Evolving Methodologies in the Study of Islamism, 2016. http://pomeps.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/POMEPS_Studies_17_Methods_Web.pdf.

- Przeworski, Adam. “Some Problems in the Study of the Transition to Democracy.” In Transitions From Authoritarian Rule: Comparative Perspectives, edited by Guillermo O’Donnell, Philippe C. Schmitter, and Laurence Whitehead, 47–61. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

- Przeworski, Adam. Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- Przeworski, Adam, Michael Alvarez, Jose Cheibub, and Fernando Limongi. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-being in the World, 1950–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Sayigh, Yezid. Above the State: The Officers’ Republic in Egypt. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2013.

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. London: Allen & Unwin, 1942, reprinted 1976.

- Stepan, Alfred C. “Religion, Democracy and the “Twin Tolerations”.” Journal of Democracy 11, no. 4 (2000): 37–57. doi: 10.1353/jod.2000.0088

- Trager, E. “The Unbreakable Muslim Brotherhood: Grim Prospects for a Liberal Egypt.” Foreign Affairs 90, no. 5 (2011): 114–126.

- Turley, Jonathan. “Tribunals and Tribulations: The Antithetical Elements of Military Governance in a Madisonian Democracy.” GEO. WASH. L. REV 70 (2002): 649–653.

- Varol, Ozan. “The Military as the Guardian of Constitutional Democracy.” 51 Colum. Journal of Transnational Law and Policy 547 (2012–2013).

- Wickham, Carrie. Mobilizing Islam: Religion, Activism, and Political Change in Egypt. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.