ABSTRACT

The impact of external actors on political change in the European neighbourhood has mostly been examined through the prism of elite empowerment through externally offered incentives. The legitimacy of external policies has received less scrutiny, both with regard to liberal powers promoting democracy and illiberal powers preventing democracy. This article investigates the conflicting notions of legitimate political governance that underpin the contest between the European Union (EU) and Russia in the Eastern neighbourhood. It proposes four mechanisms of external soft influence that take into account the EU’s and Russia’s actorness and the structural power of their norms of political governance, and consider their effects on domestic actors and societal understandings of appropriate forms of political authority. It finally traces the EU’s and Russia’s soft influence on political governance in Ukraine. It maintains that through shaping the domestic understandings of legitimate political authority and reinforcing the domestic political competition, the EU and Russia have both left a durable imprint on Ukraine’s uneven political path.

Introduction

The EU’s and Russia’s approaches to their common neighbourhood in Eastern Europe have often been contrasted as opposites, with the EU frequently portrayed as a prime supporter of democratization in the former Soviet space and Russia frequently presented as a spoiler of democratization, if not an outright supporter of authoritarianism in the region. Both external actors have used a wide variety of instruments ranging from more coercive to softer tools to influence the domestic political trajectories of the former Soviet states, geographically squeezed between the EU and Russia. The democracy ratings of the countries concerned indicate that the authoritarian temptation has been strong across the region but that democracy has nevertheless found more conducive ground in some countries than in others.Footnote1

The scholarly literature on the international dimensions of democratization has only recently begun examining the role of powerful autocracies in protecting other authoritarian regimes, inter alia blocking international democratization pressure on the latter.Footnote2 The tendency has been to zoom in on the coercive and incentive-based policies of these actors, under-emphasizing their soft influences on the political governance of non-democracies. The EU-focused scholarship has largely disregarded the role of other external non-Western actors on the domestic polities of non-EU countries, focusing mainly on the EU’s impact on democratic governance in those countries.Footnote3 And although conceptual models foresee the possibility for “cross-conditionality” or policies of other actors that work at cross-purposes with EU policy, the emphasis has been on teasing out the EU mechanisms of democracy support. Empirical studies have revealed some of the “pathologies of Europeanization”Footnote4 but the overwhelming majority of scholars have tended to view the EU as a “force for good” in democratization, assuming its positive impact without scrutinizing closely its soft influence on the political trajectories of non-EU countries.Footnote5

This article sets out to examine the EU’s and Russia’s soft influence on the political governance of countries from the eastern neighbourhood. It analyses the capacity of both actors to shape the domestic political trajectories in the region via non-coercive means, by representing political examples worthy of emulation and by emphasizing the attractiveness of their political models in external policies. It proposes four mechanisms of external soft influence that take into account the EU’s and Russia’s actorness and the structural power of their norms of political governance, and consider their effects on domestic actors and societal understandings of appropriate forms of political authority. It further explores the extent to which the ideational sway of the two actors has traction on the politics and society in Ukraine – a country whose political trajectory has oscillated between authoritarianism and democracy in its post-independence history and whose domestic political transformation has been marked by a particularly acute contestation between pro-EU and pro-Russia political forces. It maintains that the EU and Russia have both directly and indirectly influenced Ukraine’s uneven political path through legitimizing opposing visions of political governance.

External soft influence and domestic political governance

The literature on the EU’s impact on political change in the eastern neighbourhood has largely followed the EU enlargement scholarship in embracing the external incentives model as the main explanation for the lack of a tangible EU imprint on political developments in the region. Weak and under-specified incentives for EU integration and fuzzy conditions for their delivery have been put forward as the main reasons for the EU’s poor performance vis-à-vis its eastern neighbours.Footnote6 Where partial democracy-enhancing reform has occurred, it has come as a result of occasional outmanoeuvring of change-resistant elites by pro-reform groups banking on EU support.Footnote7 Instrumentalization of EU support by seemingly liberal reform coalitions has taken place in parallel too, with EU resources being de facto thrown behind democratic backsliding in some cases.Footnote8 The overall conclusion of this research strand is that the EU conditionality cannot generate a reform dynamic similar to the pre-accession context, owing to problems of credibility and high adoption costs for incumbents.Footnote9 These dominant scholarly accounts emphasize political agency and zoom in on the policies of external actors and the rational choices of domestic actors in democratizing countries as the main driving force behind democratization trends.

An alternative view of east European countries’ political trajectories has co-existed but has rarely engaged directly with the EU external governance scholarship. That parallel line of enquiry has credited the international structural environment with the lack of tangible political change in the eastern neighbourhood. In this vein of research, the poor democracy record in the post-Soviet space is attributed primarily to the region’s low economic, geopolitical, social and communication linkages to the EU and the United States (US), with low Western leverage reinforcing the pattern.Footnote10 When unpacking the external linkages of the eastern neighbours, Sasse has found the region to be linked in various ways to both the EU and Russia, with some countries evenly connected to both regional patrons and others more densely tied to one or the other.Footnote11 Echoing some of the findings about the “dark side of Europeanization”,Footnote12 she has insisted that linkage to the West can spur democratic change only when it reinforces political competition in the country concerned. In other words, linkages to the West alone, even if dense and substantial, do not guarantee a democratic outcome and may even work against democracy. Tolstrup goes one step further and claims that linkages can be manipulated by what he calls “gatekeeping elites” who are able to activate or deactivate a country’s external ties thus bringing political agency back into the democratization equation.Footnote13

Recently, scholars have begun to investigate more systematically the influence of non-Western external actors on political developments in non-democracies.Footnote14 Similar to the democratization scholarship, the influence of illiberal regional powers is mostly examined through study of the policies and actions of powerful autocracies at the expense of the structural dimensions of their outreach. In this vein, Risse and Babayan have suggested that illiberal powers, while not promoting autocracy per se, can de facto support authoritarian rule by empowering illiberal domestic coalitions.Footnote15 In the eastern neighbourhood Russia has long been coined a spoiler of democratization but its role in propping up friendly authoritarian regimes in the post-Soviet space has not yet been fully uncovered. Tolstrup has maintained that Russia persistently undermines the liberal performance of countries in its “near abroad” through its policies of “managed stability” and “managed instability”.Footnote16 Not everyone shares this view. Echoing the “pathologies of Europeanization”, some scholars have discovered that illiberal powers can unintentionally boost democratization while trying to strengthen autocratic allies.Footnote17 Russia’s coercive policy towards the eastern neighbours has been seen by some as anchoring countries even more firmly in the Western sphere and generating more resolve in pro-democracy domestic constituencies.Footnote18 Yet others find Russia’s policies of democracy prevention as having no particular traction on political governance in the post-Soviet space where domestic conditions, on the whole, are unfavourable to democratization.Footnote19 While Russia’s influence is open to debate, the tendency has been to discuss its policies and their effect on domestic actors through the rational choice paradigm of incentives, rewards, sanctions, punishments and the ensuing reactions of rational individuals.

The structural influence of linkages to authoritarian powers on domestic regime outcomes has not been consistently investigated, although some scholars have hypothesized that denser ties with authoritarian states may strengthen autocracy supporters and weaken democracy advocates in domestic regimes and as such deepen authoritarian tendencies.Footnote20 Others have suggested that substantive linkage to Russia has eroded democratic rights and liberties in the post-Soviet space.Footnote21 Still others have emphasized the links forged between the authoritarian states in the post-Soviet space and the diffusion of authoritarian pre-emptive policies in the region meant to counter the democratic contagion in the wake of the “colour revolutions” in the 2000s.Footnote22 While the scholarship is inconclusive, there is an implicit recognition that the regional context in which autocracies are embedded is important for their chances for survival, and the more that environment is defined by authoritarian trends, the higher the likelihood for authoritarian persistence.

Notable in these debates about the external impact on political governance in the eastern neighbourhood is the lack of attention to the soft mechanisms of external influence on continuity and change, notwithstanding the bourgeoning debates about the normative facets of the EU’s external powerFootnote23 and the similarly normative trends in Russian foreign policy.Footnote24 While there has been extensive debate over the last decade about whether and how the EU can be conceptualized as a normative power,Footnote25 the question of what impact the EU’s norms of liberal democracy have had on political governance in countries beyond its borders has featured less prominently on research agendas. The mechanism of socialization intended to induce gradual but durable political change has been conceptually acknowledged in the literatureFootnote26 but rarely tested in empirical work.Footnote27 Socialization models of EU external governance have emphasized the legitimacy of EU-promoted norms as a key determinant of domestic impact.Footnote28 Scholars have examined how the legitimacy of EU sovereignty-linked conditions influences state-building in the Western BalkansFootnote29 or how “identity convergence” preconditions progress towards EU accession of countries from the region more generally,Footnote30 but analysis of how the EU’s conception of democracy contributes to its impact on democratization is rare.Footnote31 Likewise, Russia’s claims to represent a “sovereign democracy” model are well established in political discourse and popular commentary but little is known about whether and how Russia’s ideas about political life have traction on societies and political elites beyond its borders.

In order to arrive at a holistic understanding of external soft influence on domestic political governance, it is necessary to take into account both the deliberate actions of external players to socialize domestic actors and the structural power of external norms over domestic understandings of appropriate forms of political authority. In other words, the analysis should bear in mind both agency and structure at both the domestic and the external level and consider their cross-effects in order to avoid an arbitrary privileging of either agents or structures in explanatory accounts of external soft influences on domestic political governance. Identifying the “right” unit of analysis is a longstanding problem in social theory and has generated much reflection on how to solve the implicit bias according primacy to either agents or structures.Footnote32 By incorporating into the analysis all possible interactions between these entities, this article advances four mechanisms of external soft influence on different forms of domestic political authority (see ).

Table 1. Mechanisms of external soft influence on domestic political governance.

Collectively, the four mechanisms try to overcome the subjective preference for either individual action(s) or social structure(s) by treating agents and structures as ontologically equal entities. Each of the mechanisms offers only a partial analysis of the phenomenon examined but taken together they uncover the whole spectrum of relevant inter-relationships and as such propose a holistic understanding of the subtle ways in which external powers and norms reach out to constituencies beyond their borders. For this reason, they should be seen as complementary rather than competing pathways of external soft influence, even though empirical evidence may show that one is more significant than others in specific domestic settings. They can be equally applied to study the soft influence of powerful democracies as well as that of powerful autocracies, although the normative impact of liberal and illiberal powers on non-democracies is expected to point in opposite directions.

Persuasion of domestic actors

This mechanism traces the purposeful exchange between external actors and domestic elites (political, societal, economic) aimed at transferring ideas, templates and policy frames to relevant domestic constituencies. It emphasizes political agency on both sides of the relationship and zooms in on the intentional policies of external players to either reinforce or change the understandings of key domestic actors about appropriate forms of political authority.

Persuasion is defined as “a microprocess of socialization [that] involves changing minds, opinions, and attitudes about causality and affect (identity) in the absence of overtly material or mental coercion”.Footnote33 It has been studied in the broader context of international socialization as one of different pathways through which novices and newcomers learn new roles and acquire new beliefs and understandings.Footnote34 Non-coercive communication involves argument and deliberation and leads to social learning and norm internalization.Footnote35 The density of institutional contact has been identified as a key condition for successful persuasion but intense informal contact is equally conducive to persuasion.Footnote36

In the past decade or so both the EU and Russia have developed institutional structures that support their regular exchanges with representatives of the eastern neighbourhood states, in addition to the diplomatic channels used for official high-level communication. The EU in particular has been seen as a big socialization agency through the cooperative regimes it has developed with non-EU countries in various policy areas.Footnote37 This functional cooperation does not target the core features of the political institutions nor the main policy regimes related to political governance such as human rights or judicial independence, but contributes indirectly to democratization through the promotion of principles such as transparency, accountability and participation in key sectors of the EU acquis subject to export, especially to the EU neighbourhood.Footnote38

The EU’s efforts at engaging the eastern neighbours have centred on the multilateral track of the Eastern Partnership (EaP) since its launch in 2009. Involving numerous forums for discussion between the EU and the EaP states at all levels (heads of state, governments, parliaments, mayors, civil society organizations), the EaP is a meeting place for ongoing debate on various topics including democracy and good governance (platform 1). While scholars have doubted the genuine application of the idea of equal partnership central to the EaP discourse,Footnote39 the multilateral track of the EaP can be seen as an attempt to set in motion a socialization process in parallel to the more hierarchical mode of EU engagement through conditionality. Although not completely devoid of hierarchy, the exchanges taking place in the various forums go a long way in implementing the principle of “joint ownership” of cooperation between the EU and its eastern partners.Footnote40 The EU has also entertained more direct ways of “talking” democracy to the political elites in the eastern neighbourhood in the context of negotiating the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) Action Plans, the Visa Liberalization Action Plans and the Association Agreements as well as in the framework of conducting human rights dialogues with them. In the context of these formal relations, the EU has also maintained numerous informal contacts with representatives of the EaP countries, including communication among political leaders at the margins of official forums, exchanges within the political party families represented in the European Parliament and the Committee of the Regions, contacts between the EU bureaucracy and the national administrations of the neighbours, and so on.

Russia has also stepped up its efforts at institutionalizing the web of relations that draws the countries from its “near abroad” to its own centre of gravity, aiming to reverse the centrifugal processes that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. Most recently, it has boosted the role of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) as a main hub of economic integration of the post-Soviet space inter alia proliferating contacts and negotiations between Russia and the leadership of some of the former Soviet states. From Moscow’s point of view, this technical project is meant to grow into a geopolitical endeavour whose longevity will depend on the likemindedness of current and future generations of elites in the countries concerned.Footnote41 The EEU is in this sense the institutional vehicle through which to create a common regulatory and governance space across the participating post-Soviet countries, mimicking the EU’s own experiment and engaging in what some have called “normative rivalry” with the EU in the “shared neighbourhood”.Footnote42

Russia’s approach is also complemented by informal relations with political and societal elites across the post-Soviet space. Mimicking Western initiatives seen as key vehicles for soft influence abroad, the Kremlin has set up the Russian Cooperation Agency (Rossotrudnichestvo), the Russkiy Mir Foundation, the Russian International Affairs Council and the Gorchakov Foundation with the objective of promoting Russian interests in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) area and beyond through language, culture, diplomacy, science, assistance.Footnote43 Furthermore, under Putin, the Russian Orthodox Church has become a real foreign policy tool in Moscow’s outreach to the wider public in the former Soviet Bloc, spreading the virtues of pan-Slavism and affirming the spiritual leadership of the Moscow Patriarchate.Footnote44

Legitimization of domestic policies and practices

This mechanism captures the effects of external symbolic action on domestic societal understandings of appropriate forms of political authority. It emphasizes external agency as a source of social order in domestic settings. It views external players as active defenders of particular models of political governance and traces their conscious efforts to present an attractive narrative through political communication aimed at shaping domestic perceptions of appropriate political organization and practice.

Both the EU and Russia have actively tried to shape societal conceptions of political authority in the eastern neighbourhood. The EU has consciously projected a liberal democratic model of governance by standing up for its political values in political communication and diplomatic action. Official EU pronouncements are critical for articulating what is appropriate in specific situations and contexts. Brussels can thus endorse and encourage democratic improvements or criticize and delegitimize democratic malpractice. The EU’s record on tacitly backing up democratizing efforts in eastern neighbourhood countries is mixed and its pronouncements in concrete situations have not always lived up to its projected image of democracy defender.

Russia is no stranger to using softer ways of asserting its own interpretation of events and seeking to influence domestic developments through its own narrative on appropriate political action. Just like the EU, it has consciously worked to project itself as an attractive power centre with its own normative appeal. Unlike the EU, however, Russia’s efforts have concentrated predominantly on delegitimizing Western democracy support and less so on projecting a coherent alternative political model. In this vein, it has consistently condemned regime changes after societal mobilization as instances of illegitimate overthrow of legally elected and serving governments. The “colour revolutions” in the post-Soviet space are a particular case in point.Footnote45 Moscow has also launched an assault on the Western and Western-funded non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in Russia, demonizing them as “foreign agents” and criminalizing their activities, thus forcing them to discontinue any pro-democracy projects.Footnote46 By taking such a stance, Russia has tried to position itself as an actor opposed to the Western practices of interfering in domestic political processes and has stood up for the sovereign rights of countries to determine their own political trajectory.Footnote47 It has been less successful in projecting a positive image of what that alternative political trajectory entails.

Legitimization of domestic actions

This mechanism captures the interaction between the structural power of external actors deriving from the attractiveness of the political models they stand for and the entrepreneurship of domestic actors in target countries in using external examples as reference points in defending certain political forms and actions in public life. It highlights the agency of domestic actors to evoke certain images, ideas and practices associated with external actors in order to garner domestic support for particular types of political authority. EU scholars have advanced the notion of “‘usages of Europe’” to explain how domestic actors can instrumentalize the EU layer of governance in order to justify or reject policy ideas in their domestic environment.Footnote48 The EU’s sectoral policiesFootnote49 and democratic normsFootnote50 have been found to have democratizing effects on polities whose societies are eager to validate domestic action by aligning it with EU templates and rules. By the same logic, domestic action can be anchored on the political norms of governance of various external actors, provided that the latter represent an attractive political model to follow. In this sense, the mechanism conceives of domestic activism as a function of the structural power of external political norms and values. Important in this context is not what the EU or Russia do but how domestic actors in the eastern neighbourhood countries see and use their political identities.

The legitimacy of EU-promoted norms of democratic governance is argued to stem from what the EU is – a loose polity of 28 democracies based on the rule of law and respect for diversity.Footnote51 The EU’s identity as democracy promoter was firmly established in the post-Cold War era, most prominently in the context of EU enlargement but also beyond the immediate neighbourhood. Although the EU has shied away from naming the democratic model it subscribes to, the broad principles it has outlined in official communications reveal the liberal democratic underpinnings of its political governance standards.Footnote52

Russia, for its part, has over the years tried to articulate a critique of the Western-promoted model of liberal democracy and to present itself as an alternative model based on traditional societal values, toleration of ethnic and religious differences and preservation of the cultural heritage of various traditional societies.Footnote53 Inherent in this position is “an appeal for a pluralist international order that recognises alternative types of development and different models of modernity”.Footnote54 Pro-Kremlin experts have also argued that the Western model of democracy is not fit for all societies and cultures and maintained that societies like the Russian one need a strong state to manage societal transformation and economic modernization in order to avoid disorder and societal conflict associated with democratic transitions and political confrontation in liberal democracies.Footnote55 It has thus attempted to justify its political practice as a distinct political model, even though the general principles it has outlined are difficult to translate into a clear blueprint for political governance.

Diffusion of ideas

This mechanism traces the spread of ideas across space and time. It captures the mutual influence of societies through the power of examples and depicts processes that are not dependent on human agency. It shows an important aspect of how domestic political values are formed, re-interpreted and shaped from outside through references to external political models worthy of replication in domestic settings and without the active promotion of those models by external actors. Emulation and mimicry are two ways in which ideas and normative standards can travel across borders unaided by agents.Footnote56 Both functional and normative reasons can account for such cross-societal exchanges. And while both the EU’s and Russia’s influence on these processes is immaterial, they indirectly compete on the global market of political ideas.

Social media, satellite television and smartphone technology have been seen as key vehicles for transnational protest diffusion,Footnote57 but they can also be instrumental in spreading ideas about political practice more generally. By diffusing powerful images and providing an open space for debate and sharing of opinions, they provide easy contact with events happening elsewhere and an accessible platform for their collective interpretation in the domestic context. The advances in technology thus act as a facilitator of the global conversation on political models and templates.

External soft influence and political governance in Ukraine

The case of Ukraine is illustrative of an uneven pattern of political transformation in the post-Soviet period. Its democratic development peaked in 2006 during the early years in office of the authorities brought to power by the Orange Revolution, but declined steadily thereafter for almost a decade before reversing the trend in 2015.Footnote58 It is currently classified as a “hybrid regime” and its political governance has oscillated between democracy and authoritarianism for a good part of its independent existence since the early 1990s. The EU and Russia have both made conscious efforts to influence its domestic trajectory by offering material and ideational support, the EU for anchoring Ukraine in the Western club of liberal democracies and Russia for stopping Ukraine’s Western orientation. Ukraine has at times acquiesced with and at times defied the policies of both regional powers, while exposing the incompatibility of their external agendas. Both external actors have applied leverage to tip the balance in their preferred direction but these policies have mostly had an effect on short-term political developments. The long-term prospects for democratization in Ukraine can only be understood by considering the EU’s and Russia’s soft influences on the political governance of the country. The key to understanding this subtle impact is the recognition that the domestic legitimacy of regimes is as crucial for democratic consolidation as it is for authoritarian survival.Footnote59 It is through shaping the domestic understandings of legitimate political authority that both the EU and Russia have been able to leave a durable imprint on Ukraine’s political trajectory. This has occurred through both direct and indirect means and via reaching out to both political elites and society at large. And while Ukraine’s political pendulum is the outcome of domestic swings in popular and political support for opposing visions of political governance, the domestic views on what is appropriate in political life have been shaped by various interactions with the key protagonists of these opposing visions, the EU and Russia.

Persuasion of domestic actors in Ukraine

As a sui generis polity with a thick institutional foundation, the EU is conducive to socializing outside actors. It stepped up engagement with the Ukrainian political elite in the context of the ENP and in particular after the Orange Revolution ushered hope for a democratic future for the country in 2005. Ukraine was subsequently seen as a frontrunner from the eastern neighbourhood and a test case for the instruments that institutionalized the EU’s relations with ENP partners. In 2007 it was the first country to begin negotiations with the EU on a new-generation association agreement, including the prospect for a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area. It has worked on a national reform plan agreed with the EU first in the context of an ENP Action Plan and since 2009 in the framework of the so-called “Association Agenda”. It has been in discussion with the EU over visa liberalization since 2008. In the framework of these and other bilateral instruments, various parts of the Brussels bureaucracy have been in constant contact with their Ukrainian interlocutors from the public service and the political establishment. Moreover, since the launch of the EaP in 2009, Ukraine has been an active participant in all multilateral forums put in place to bring the EU closer to its eastern neighbours. The numerous institutionalized points of contact between the EU and Ukraine have facilitated formal dialogue and informal exchange of views, including on democracy and human rights issues. Moreover, by maintaining contacts with a wide range of interlocutors, the EU has been able to reach beyond a closed circle of top policymakers and engage Ukrainians in various public positions at senior as well as lower levels. It has kept the dialogue going regardless of who is in power in Kiev.

Russia, for its part, relies mostly on informal contacts to reach out to Ukraine, which has kept out of the institutionalized web of contacts in the EEU context. Moscow’s influence on Ukraine is “substantially less structured and institutionalised than the Western one” and consists primarily of setting up and strengthening anti-Western platforms in the Ukrainian business community, civil society and political circles.Footnote60 Russia also banks on Ukraine’s unreformed institutions and obscure relationship between business and politics to further its informal influence. While these informal practices are difficult to document, their existence is hard to deny. The energy sector in Ukraine, for example, is well known to be tightly interconnected with the Russian energy business, itself closely linked to Russian state interests and subject to Kremlin political tutelage. The so-called government-organized NGOs (GONGOs) sponsored by the Russian government and based in Ukraine are another vehicle through which Russia tries to counter Western political narratives and Western-financed civil society initiatives.Footnote61 Furthermore, owing to Russia’s state monopoly over television broadcasting, Russian television has actively diffused Moscow’s political narrative across Ukraine, providing a mirror image of Ukraine’s political events through the Kremlin prism.Footnote62 The Russian language proficiency of a very large number of Ukrainians (around 94% of the populationFootnote63) has undoubtedly facilitated Russia’s (dis)information policy. Last but not least, Patriarch Kirill I of the Russian Orthodox Church, a true spokesperson of Kremlin political worldviews, has not only tried to assert the supremacy of the Moscow Patriarchate in Ukraine but has also persistently emphasized the cultural and spiritual unity of Russians and Ukrainians.Footnote64

Legitimization of domestic policies and practices in Ukraine

The EU’s actual support for pro-democracy forces in Ukraine has mostly been described as weak, insufficient and inconsistent.Footnote65 What is often overlooked, however, is the important symbolic help the EU has been able to provide to the democracy cause in Ukraine at critical junctures of recent political history. One such episode is the societal mobilization against the Yanukovych government in 2013–2014, when the EU’s “strong moral authority” was particularly visible.Footnote66 Throughout the unfolding crisis, the EU consistently sent strong messages of support to the protesters on the Euromaidan. Through its frequent communiqués and press releases on the Ukrainian crisis, the EU actively sought to frame the perception of what was appropriate in the volatile and changing situation, directly conferring legitimacy on some actors and condemning the actions of others.Footnote67 The most visible sign of EU support for the aspirations of Ukrainian society towards clean governance and public accountability of officeholders was its direct endorsement of the demands of the Euromaidan movement, including through high-level EU diplomatic presence at rallies in Kiev.

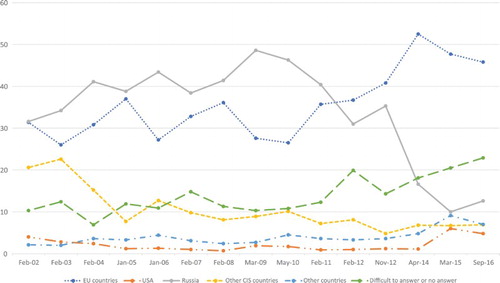

The EU was able to play such a role owing to the alignment of its views with those of a sizeable part of the Ukrainian society. The Euromaidan protests were above all against a kleptocratic authoritarian regime that departed from societal understandings of accountable and socially responsible governance. Ukrainian society is far from consensual about the model of political governance it wants to follow but a majority of Ukrainians (50.9%) see democracy as “the most suitable type of political system for Ukraine”.Footnote68 A large proportion of citizens also view the European orientation of Ukraine as a legitimate priority for the country and the size of this constituency has only increased since the Euromaidan protests – see .

Figure 1. Ukrainians’ views on the preferred foreign policy orientation of their country, in %.

Russia has also seized the Euromaidan protests to develop its critical discourse on various Western policies, trying to position itself as a positive actor opposed to the meddling Western practices of interference and control. Russia’s state-controlled media outlets and pro-Kremlin Russian experts echoed the official attempts to present the Ukrainian societal mobilization as an illegitimate, unconstitutional and Western-backed coup by extreme-right groups and neo-Nazis.Footnote69 It actively tried to frame an alternative image of the crisis in Ukraine and to present Russia in positive terms as a “force for good” acting within the law, responding to the legitimate concerns of the Russian speakers in southern and eastern Ukraine and trying to undo a massive injustice instigated by Western-backed violent extremists who toppled the legitimately elected and constitutional government in Kiev.Footnote70

Russia’s political narrative has over the years found receptive ground in a segment of Ukrainian society that is nostalgic about the Soviet times and identifies with a Soviet-type state paternalism.Footnote71 Opinion polls have consistently shown that those societal groups prefer integration in Russia-led unions to European integration, although the size of this constituency has drastically shrunk since the Crimea annexation – see . A representative survey conducted on behalf of the EU in autumn 2012 reveals that 20% of Ukrainians are satisfied with the way “democracy” works in their country.Footnote72 Another recurrent representative poll shows consistently across the years that about a fifth of Ukrainians view autocracy as preferable to democracy in some circumstances.Footnote73

Legitimization of domestic actions in Ukraine

The political spectrum in Ukraine has often been described as divided between pro-EU and pro-Russia political forces.Footnote74 While oversimplified and not the only cleavage in Ukrainian politics, the positioning of the political actors with regard to the two main regional powers is indicative of the sources of their external identification. The pro-Western political formations have all relied on political endorsement from the EU and used their pro-EU credentials to secure electoral support. Likewise, the pro-Russian political parties have always emphasized Ukraine’s traditional cultural ties, Soviet legacy and ethno-linguistic similarities with Russia, even if officially supporting the country’s European journey.

Most of the elections in Ukraine’s recent political history have not only been hotly contested but have also manifested the clash between two visions for the country’s future, one anchored on the European political model of liberal democracy and the other associated with Russia and its illiberal political tradition of state paternalism and centralized leadership captured in the term “managed democracy”. Taras Kuzio has described the 2004 election that triggered the Orange Revolution as “a ‘clash of civilizations’ between two political cultures: Eurasian and European”.Footnote75 While Yushchenko stood for “European values”, Yanukovych represented “the neo-Soviet political culture that dominated Russia and the Eurasian CIS”.Footnote76 The 2010 presidential election echoed this clash, opposing the West-leaning Tymoshenko and the Russia-leaning Yanukovych. By contrast, the 2014 presidential vote, held shortly after the Euromaidan, marked a shift in Ukrainian public opinion away from pro-Russian political forces and towards pro-European candidates, with Petro Poroshenko winning a convincing 54% of the vote in the first round.Footnote77 And while domestic concerns top the list of factors that determine the political choice of Ukrainian voters, the vote for domestic reform is more often associated with pro-EU political formations whereas the vote for the status quo is more often linked with pro-Russian political actors.

This underlying political conflict that has defined Ukraine’s politics since independence has occurred without incitation from outside. Domestic political actors have themselves constructed a political identity that draws on external symbols, frames and templates. The pro-EU rhetoric and references to European standards and norms have helped pro-European forces craft an image that appeals to the segments of Ukrainian society that would like to leave behind the Soviet past and embrace democratic practice as known from the European experience. The symbolic toppling of the statue of Lenin in central Kiev by the Euromaidan protestors embodies this quest for a break with the past.Footnote78 The massive presence of EU flags and slogans affirming the Europeanness of Ukraine at the Euromaidan ralliesFootnote79 has similarly symbolized the search for the kind of normalcy in political life associated with the European political example.

Likewise, the support base of the pro-Russian Party of Regions (Opposition Bloc since 2014) in eastern and southern Ukraine has been attributed to the distinct identity of Ukrainians living there, heavily influenced by political, social and economic developments in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union.Footnote80 When in power, Yanukovych consolidated the image of the Party of Regions as the main defender of the Russophone population in Ukraine, including through various initiatives meant to elevate the legal status of the Russian language.Footnote81 Endorsing the viewpoints central to the Kremlin discourse helped the Party of Regions establish itself as a “neo-Soviet political force” and appeal to constituencies nostalgic of the past, in the years prior to the annexation of Crimea.Footnote82 Russia’s aggressive policy in Crimea and the Donbas however has done much to undo its soft political influence in Ukraine since 2014.Footnote83 In 2016, a large majority of 71.8% of Ukrainians considered Russia an aggressor in eastern Ukraine whereas only 8.4% thought that Russia was not a party to the conflict.Footnote84

Diffusion of ideas in Ukraine

The free flow of ideas has at times both helped Ukraine’s democratization prospects and facilitated the strengthening of authoritarian rule in the country.

The Euromaidan protests unfolded in parallel to similar events taking place in Turkey, Brazil, Spain, Bulgaria and Egypt. These and other contemporary protest movements use similar organizational tactics and resistance frames.Footnote85 Although local in nature, they happen with the knowledge that similar protests are unfolding elsewhere at the same time and collectively contribute to a global protest narrative.Footnote86 Similar to other protests, the Euromaidan movement used social media, in particular Facebook and Twitter, to coordinate protest actions and to disseminate information to non-participants, including to an international audience.Footnote87 Observing closely how Ukrainian protesters used social media, Barberá and Metzger found that Facebook was much more actively used for logistical purposes concerning the location of gatherings, sites of violence, places to get hot tea, and so on, with the main Facebook page operating almost entirely in Ukrainian. In contrast, Twitter was strategically used to call international attention to what was happening on the streets of Kiev, with the vast majority of tweets communicating information in English.Footnote88 Social media and internet news sites were also instrumental in framing protest demands and slogans and interpreting protest events.Footnote89 The Euromaidan protests attracted citizens with a wide range of social and political backgrounds, who came out in the streets spontaneously,Footnote90 confirming the global trend of a “leaderless” protest organization outside the political process and without the involvement of traditional NGOs.Footnote91 For many of its features, the Euromaidan mobilization can be seen as an example of protest diffusion across borders.

Similarly, the Russian domestic policies developed to counter the contagion effects of the “colour revolutions” in Eastern Europe on Russia itself have not only obstructed pro-democracy external assistance at home but have also enjoyed a second life abroad through emulation by other authoritarian leaders. Russia’s restrictive legislation on the activities of NGOs and on social protests is a case in point. It clearly inspired the Yanukovych government’s legal actions to criminalize pro-democracy protests in Ukraine in early 2014 as the Euromaidan protests were unfolding.Footnote92 And while such policies did not last long in Ukraine owing to the societal revolt against these and other authoritarian practices, the Kremlin-inspired legislation can be said to have been enabled by the free travel of ideas across borders.

Conclusion

The preceding analysis has demonstrated the relevance of the soft mechanisms of EU and Russian influence on the eastern neighbourhood. The lack of a stronger EU imprint on democracy in the former Soviet countries has too often been attributed to the absence of strong incentives, in particular the golden carrot of an EU accession prospect. This article has shown that the EU’s democratizing influence is not limited to the material sphere. It can empower domestic agents of change by directly and indirectly legitimizing the democracy cause. Its soft influence, however, is conditioned by the domestic understandings of legitimate political authority, and faces opposition in those Eastern European societies that are not consensual about the appropriateness of liberal democracy in the local context. Likewise, Russia’s impact on Eastern Europe has too often been seen through the prism of coercive power politics. The article has revealed that Russia is no stranger to using softer means of political influence and just like the EU is constrained in what it can achieve in the eastern neighbourhood, by societal norms of appropriate political governance.

The article has also demonstrated the merits of examining holistically the external soft influences on domestic political governance, taking into account the EU’s and Russia’s actorness and the structural power of their political norms and considering their effects on domestic actors and norms of political authority. It has put forward four mechanisms of external soft influence which collectively consider all possible interactions between agents and structures, at the international and the domestic level. It has revealed how external influence that both favours democracy and works against it can be channelled through various subtle pathways via microprocesses of persuasion, the external legitimization of domestic actors and actions and the transnational diffusion of ideas. The article has thus advanced a conceptual approach of studying the soft influence of both liberal and illiberal external actors whose powers of appeal have been under-studied in the literature on the international dimension of democratization and authoritarian rule. It has offered a new perspective on the capacities of such actors to inspire domestic political change, calling inter alia for more research on this theme, using the examples of other regional players and tracing their influences in different geographical settings. Cumulative empirical evidence can provide the basis for drawing more general conclusions about the relative significance of the four mechanisms, including their weight in the foreign policy toolkit of different types of actors as well as their explanatory potential in different regional environments.

The case of Ukraine has demonstrated how opposing external soft influences can dramatically clash in a divided society not sure of its political identity. Ukraine’s internal societal friction based on different political visions for the country’s future has been reproduced at the political level, resulting in an uneven trend of democratic advances and setbacks. And while external actors or norms alone cannot provide a sufficient explanation of Ukraine’s patchy democracy record, their interaction with domestic actors and norms has reinforced the inconsistent political trajectory of the country to date. The EU and Russia have both appeared more influential than the other at different periods of time, with Russia’s power of appeal dramatically plummeting after 2014. More importantly, these opposing external soft influences have reinforced the domestic political competition in Ukraine and in this way improved the country’s long-term prospects for democratization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gergana Noutcheva

Gergana Noutcheva is an Associate Professor of International Relations at the Political Science Department of Maastricht University, The Netherlands.

Notes

1 Freedom House, “Nations in Transit 2016.”

2 Burnell and Schlumberger, “Promoting Democracy – Promoting Autocracy?”; Risse and Babayan, “Democracy Promotion.”

3 Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, The Europeanization of Central and Eastern Europe; Vachudova, Europe Undivided; Börzel and Risse, “From Europeanisation to Diffusion.”

4 Börzel and Pamuk, “Pathologies of Europeanization.”

5 Manners, “Normative Power Europe”; Grabbe, The EU's Transformative Power.

6 Weber, Smith, and Baun, Governing Europe's Neighbourhood; Whitman and Wolff, The European Neighbourhood Policy in Perspective.

7 Langbein and Wolczuk, “Convergence without Membership?”

8 Börzel and Pamuk, “Pathologies of Europeanization.”

9 Schimmelfennig and Scholtz, “EU Democracy Promotion.”

10 Way and Levitsky, “Linkage, Leverage, and the Post-Communist Divide.”

11 Sasse, “Linkages and the Promotion of Democracy.”

12 Börzel and Pamuk, “Pathologies of Europeanization.”

13 Tolstrup, “When Can External Actors Influence Democratization?”

14 Von Soest, “Democracy Prevention”; Vanderhill, Promoting Authoritarianism Abroad; Ambrosio, Authoritarian Backlash.

15 Risse and Babayan, “Democracy Promotion.”

16 Tolstrup, “Studying a Negative External Actor.”

17 Börzel, “The Noble West.”

18 Delcour and Wolczuk, “Spoiler or Facilitator of Democratization?”

19 Way, “The Limits of Autocracy Promotion.”

20 Ambrosio, “Constructing a Framework of Authoritarian Diffusion.”

21 Cameron and Orenstein, “Post-Soviet Authoritarianism.”

22 Silitski, “'Survival of the Fittest.’”

23 Manners, “Normative Power Europe”; Whitman, “The Neo-Normative Turn.”

24 Averre, “Competing Rationalities”; Casier, “The EU–Russia Strategic Partnership.”

25 Sjursen, “The EU as a ‘Normative’ Power”; Diez, “Normative Power as Hegemony.”

26 Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, The Europeanization of Central and Eastern Europe; Börzel and Risse, “From Europeanisation to Diffusion.”

27 For an exception see Checkel, “International Institutions and Socialisation in Europe.”

28 Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, The Europeanization of Central and Eastern Europe.

29 Noutcheva, “Fake, Partial and Imposed Compliance.”

30 Subotic, “Europe is a State of Mind.”

31 Noutcheva, “Societal Empowerment and Europeanisation.”

32 Wendt, “The Agent-Structure Problem”; Carlsnaes, “The Agent-Structure Problem.”

33 Johnston, “Treating International Institutions,” 496.

34 Park, “Socialisation and the Liberal Order.”

35 Risse, “Let's Argue!”

36 Checkel, “International Institutions and Socialisation in Europe”; Park “Socialisation and the Liberal Order”; Johnston, “Treating International Institutions.”

37 Lavenex and Schimmelfennig, Democracy Promotion in the EU’s Neighbourhood .

38 Ibid.

39 Korosteleva, “Change or Continuity.”

40 Delcour, “The Institutional Functioning of the Eastern Partnership.”

41 Popescu, “Eurasian Union.”

42 Dragneva and Wolczuk, “Russia, the Eurasian Customs Union and the EU.”

43 Van Herpen, Putin's Propaganda Machine, 34–40.

44 Ibid., 129–138.

45 Finkel and Brudny, “No More Colour!”

46 Van Herpen, Putin's Propaganda Machine, 40–43.

47 Sakwa, Frontline Ukraine, 34.

48 Woll and Jacquot, “Using Europe.”

49 Dimitrova and Buzogány, “Post-Accession Policy-Making in Bulgaria and Romania.”

50 Noutcheva, “Societal Empowerment and Europeanisation.”

51 Manners, “Normative Power Europe.”

52 Wetzel and Orbie, “Promoting Embedded Democracy?”

53 Dannreuther, “Russia and the Arab Spring.”

54 Sakwa, Frontline Ukraine, 34.

55 Dannreuther, “Russia and the Arab Spring.”

56 Börzel and Risse, “From Europeanisation to Diffusion.”

57 Bellin, “The Robustness of Authoritarianism”; Della Porta and Mattoni, Spreading Protest.

58 Freedom House, “Nations in Transit 2016.”

59 Gerschewski, “The Three Pillars of Stability”; Korosteleva, “Questioning Democracy Promotion.”

60 Suchko, “The Impact of Russia,” 1.

61 Bogomolov and Lytvynenko, “A Ghost in the Mirror,” 7.

62 Ibid., 8–9.

63 See 2002 poll, http://old.razumkov.org.ua/eng/poll.php?poll_id=594.

64 Bogomolov and Lytvynenko, “A Ghost in the Mirror,” 11–13.

65 Delcour and Wolczuk, “Spoiler or Facilitator of Democratization?”

66 Samokhvalov, “Ukraine between Russia and the European Union.”

67 Council of the European Union, Council Conclusions on Ukraine, 2014a, 2014b, 2014c.

68 Razumkov Centre, “Attitudes of the Population.”

69 The Economist, “Russia's Chief Propagandist.”

70 See interview with Vladimir Putin, Radio Europe 1 and TF1 TV, 2014, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/45832.

71 Torbakov, “Insecurity Drives Putin's Crimea Response.”

72 EU Neighbourhood Barometer East, 2012.

73 Razumkov Centre, “Attitudes of the Population”

74 Wilson, “Ukrainian Politics Since Independence.”

75 Kuzio, “From Kuchma to Yushchenko,” 35.

76 Ibid.

77 Shevel, “How Putin Turned Ukraine to the West.”

78 Wolczuk and Wolczuk, “What You Need to Know.”

79 For a sample of Euromaidan slogans see http://www.rferl.org/media/photogallery/ukraine-protest-signs-euromaidan/25180736.html.

80 Petro, “Understanding the Other Ukraine.”

81 Sakwa, Frontline Ukraine, 56.

82 Kuzio, “The Origins of Peace,” 111–113.

83 Shevel, “How Putin Turned Ukraine to the West.”

84 Razumkov Centre, “Russia's Position.”

85 Della Porta and Mattoni, Spreading Protest.

86 Kaldor, Moore, and Selchow, Global Civil Society 2012.

87 Barberá and Metzger, “How Ukrainian Protestors Are Using Twitter and Facebook.”

88 Barberá and Metzger, “Tweeting the Revolution.”

89 Onuch, “Social Networks and Social Media.”

90 Ibid.

91 Anheier, Kaldor, and Glasius, “The Global Civil Society Yearbook.”

92 Rettman, “Ukraine Criminalises Pro-EU Protests.”

Bibliography

- Ambrosio, Thomas. Authoritarian Backlash: How the Kremlin Undermines Democratization in the Former Soviet Union. Surrey: Ashgate, 2009.

- Ambrosio, Thomas. “Constructing a Framework of Authoritarian Diffusion: Concepts, Dynamics, and Future Research.” International Studies Perspectives 11 (2010): 375–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-3585.2010.00411.x

- Anheier, Helmut, Mary Kaldor, and Marlies Glasius. “The Global Civil Society Yearbook: Lessons and Insights 2001–2011”. In Global Civil Society 2012. Ten Years of Critical Reflection, edited by M. Kaldor, H. L. Moore, and S. Selchow, 2–26. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Averre, Derek. “Competing Rationalities: Russia, the EU and the ‘Shared Neighbourhood’.” Europe-Asia Studies 61, no. 1 (2009): 1689–1713. doi: 10.1080/09668130903278918

- Barberá, Pablo, and Megan Metzger. “How Ukrainian Protestors Are Using Twitter and Facebook.” The Washington Post, December 4, 2013.

- Barberá, Pablo, and Megan Metzger. “Tweeting the Revolution: Social Media Use and the #Euromaidan Protests.” Huffpost Politics, 23 April 2014. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/pablo-barbera/tweeting-the-revolution-s_b_4831104.html.

- Bellin, Eva. “Reconsidering the Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Lessons From the Arab Spring.” Comparative Politics 44, no. 2 (2012): 127–149. doi: 10.5129/001041512798838021

- Bogomolov, Alexander and Oleksandr Lytvynenko. “A Ghost in the Mirror: Russian Soft Power in Ukraine.” Chatham House Briefing Paper, January 2012.

- Börzel, Tanja. “The Noble West and the Dirty Rest? Western Democracy Promoters and Illiberal Regional Powers.” Democratization 22, no. 3 (2015): 519–535. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2014.1000312

- Börzel, Tanja, and Yasemin Pamuk. “Pathologies of Europeanisation: Fighting Corruption in the Southern Caucasus.” West European Politics 35, no. 1 (2012): 79–97. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.631315

- Börzel, Tanja A., and Thomas Risse. “From Europeanisation to Diffusion: Introduction.” West European Politics 35, no. 1 (2012): 1–19. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.631310

- Burnell, Peter, and Oliver Schlumberger. “Promoting Democracy – Promoting Autocracy? International Politics and National Political Regimes.” Contemporary Politics 16, no. 1 (2010): 1–15. doi: 10.1080/13569771003593805

- Cameron, David R., and Mitchell Orenstein. “Post-Soviet Authoritarianism: The Influence of Russia in Its ‘Near Abroad’.” Post-Soviet Affairs 28, no. 1 (2012): 1–44. doi: 10.2747/1060-586X.28.1.1

- Carlsnaes, Walter. “The Agency-Structure Problem in Foreign Policy Analysis.” International Studies Quarterly 36, no. 3 (1992): 245–270. doi: 10.2307/2600772

- Casier, Tom. “The EU–Russia Strategic Partnership: Challenging the Normative Argument.” Europe-Asia Studies 65, no. 7 (2013): 1377–1395. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2013.824137

- Checkel, Geffrey. “International Institutions and Socialisation in Europe: Introduction and Framework.” International Organization 59, no. 4 (2005): 881–826. doi: 10.1017/S0020818305050289

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on Ukraine. 10 February 2014a.

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on Ukraine. 14 April 2014b.

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on Ukraine. 12 May 2014c.

- Dannreuther, Roland. “Russia and the Arab Spring: Supporting the Counter-Revolution?” Journal of European Integration 37, no. 1 (2015): 77–94. doi: 10.1080/07036337.2014.975990

- Delcour, Laure. “The Institutional Functioning of the Eastern Partnership: An Early Assessment.” Eastern Partnership Review 1 (2011). http://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2276452.

- Delcour, Laure, and Kataryna Wolczuk. “Spoiler or Facilitator of Democratization? Russia’s Role in Georgia and Ukraine.” Democratization 22, no. 3 (2015): 459–478. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2014.996135

- Della Porta, D., and A. Mattoni, eds. Spreading Protest. Social Movements in Times of Crisis. Colchester: ECPR Press, 2014.

- Diez, Thomas. “Normative Power as Hegemony.” Cooperation and Conflict 48 (2013): 194–210. doi: 10.1177/0010836713485387

- Dimitrova, Antoaneta, and Aron Buzogány. “Post-Accession Policy-Making in Bulgaria and Romania: Can Non-State Actors Use EU Rules to Promote Better Governance?” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 52, no. 1 (2014): 139–156. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02452-13

- Dragneva, Rilka, and Kataryna Wolczuk. “Russia, the Eurasian Customs Union and the EU: Cooperation, Stagnation or Rivalry?” Chatham House Briefing Paper 2012/01. London: Chatham House, August 2012.

- EU Neighbourhood Barometer East, Autumn 2012.

- Finkel, Evgeny, and Yitzhak M. Brudny. “No More Colour! Authoritarian Regimes and Colour Revolutions in Eurasia.” Democratization 19, no. 1 (2012): 1–14. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2012.641298

- Freedom House. “Nations in Transit 2016: Europe and Eurasia Brace for Impact.” 2016. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/FH_NIT2016_Final_FWeb.pdf.

- Gerschewski, Johannes. “The Three Pillars of Stability: Legitimation, Repression, and Co-Optation in Autocratic Regimes.” Democratization 20, no. 1 (2013): 13–38. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2013.738860

- Grabbe, Heather. The EU’s Transformative Power: Europeanization Through Conditionality in Central and Eastern Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

- Johnston, Alastair Iain. “Treating International Institutions as Social Environments.” International Studies Quarterly 45, no. 4 (2001): 487–515. doi: 10.1111/0020-8833.00212

- Kaldor, M., H. L. Moore, and S. Selchow, eds. Global Civil Society 2012. Ten Years of Critical Reflection. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Korosteleva, Elena A. “Change or Continuity: Is the Eastern Partnership an Adequate Tool for the European Neighbourhood?” International Relations 25 (2011): 243–262. doi: 10.1177/0047117811404446

- Korosteleva, Elena A. “Questioning Democracy Promotion: Belarus” Response to the “Colour Revolutions.”” Democratization 19, no. 1 (2012): 37–59. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2012.641294

- Kuzio, Taras. “From Kuchma to Yushchenko: Ukraine’s 2004 Presidential Elections and the Orange Revolution.” Problems of Post-Communism 52, no. 2 (2005): 29–44.

- Kuzio, Taras. “The Origins of Peace, Non-Violence and Conflict in Ukraine.” In Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives, edited by Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska and Richard Sakawa, 109–122. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2015.

- Langbein, Julia, and Kataryna Wolczuk. “Convergence Without Membership? The Impact of the European Union in the Neighbourhood: Evidence From Ukraine.” Journal of European Public Policy 19, No. 6 (2012): 863–881. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2011.614133

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Frank Schimmelfennig. Democracy Promotion in the EU’s Neighbourhood: From Leverage to Governance? London: Routledge, 2012.

- Manners, Ian. “Normative Power Europe: A Contradiction in Terms?” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 40, no. 2 (2002): 235–258.

- Noutcheva, Gergana. “Fake, Partial and Imposed Compliance: The Limits of the EU’s Normative Power in the Western Balkans.” Journal of European Public Policy 16, no. 7 (2009): 1065–1084. doi: 10.1080/13501760903226872

- Noutcheva, Gergana. “Societal Empowerment and Europeanization: Revisiting the EU’s Impact on Democratization.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 54, no. 3 (2016): 691–708.

- Onuch, Olga. “Social Networks and Social Media in Ukrainian ‘Eurmaidan’ Protests.” Monkey Cage, Washington Post, 2 January 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2014/01/02/social-networks-and-social-media-in-ukrainian-euromaidan-protests-2/.

- Park, Susan. “Socialisation and the Liberal Order.” International Politics 51, no. 3 (2014): 334–349. doi: 10.1057/ip.2014.14

- Petro, Nicolai N. “Understanding the Other Ukraine: Identity and Agency in Roussophone Ukraine.” In Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives, edited by Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska and Richard Sakawa, 19–35. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2015.

- Popescu, Nicu. “Eurasian Union: The Real, the Imaginary and the Likely.” Chaillot Paper No. 132. Paris: EU Institute for Security Studies, September 2014.

- Razumkov Centre. “Attitudes of the Population of Ukraine towards Democracy and Authoritarianism” (recurrent, 2004–2012). 2016a. http://old.razumkov.org.ua/eng/poll.php?poll_id=612.

- Razumkov Centre. “How do you assess Russia’s position in the conflict in eastern Ukraine?” 2016b. http://old.razumkov.org.ua/eng/poll.php?poll_id=1024.

- Rettman, Andrew. “Ukraine Criminalises Pro-EU Protests.” EUobserver, 17 January 2014.

- Risse, Thomas. ““Let’s Argue!”: Communicative Action in World Politics. International Organization 54, no. 1 (2000): 1–39. doi: 10.1162/002081800551109

- Risse, Thomas, and Nelli Babayan. “Democracy Promotion and the Challenges of Illiberal Regional Powers: introduction to the Special Issue.” Democratization 22, no. 3 (2015): 381–399. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2014.997716

- Sakwa, Richard. Frontline Ukraine: Crisis in the Borderlands. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 2016.

- Samokhvalov, Vsevolod. “Ukraine Between Russia and the European Union: Triangle Revisited.” Europe-Asia Studies 67, no. 9 (2015): 1371–1393. doi: 10.1080/09668136.2015.1088513

- Sasse, Gwendolyn. “Linkages and the Promotion of Democracy: The EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood.” Democratization 20, no. 4 (2013): 553–591. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2012.659014

- Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Hanno Scholtz. “EU Democracy Promotion in the European Neighbourhood.” European Union Politics 9, no. 2 (2008): 187–215. doi: 10.1177/1465116508089085

- Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Ulrich Sedelmeier, eds. The Europeanization of Central and Eastern Europe. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2005.

- Shevel, Oxana. “How Putin Turned Ukraine to the West.” Monkey Cage, Washington Post, 29 October 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/monkey-cage/wp/2014/10/29/how-putin-turned-ukraine-to-the-west/.

- Silitski, Vitali. ““Survival of the Fittest:” Domestic and International Dimensions of the Authoritarian Reaction in the Former Soviet Union Following the Colored Revolutions.” Communist and Post-Communist Studies 43 (2010): 339–350. doi: 10.1016/j.postcomstud.2010.10.007

- Sjursen, Helene. “The EU as a ‘Normative’ Power: How Can This Be?” Journal of European Public Policy 13, no. 2 (2006): 235–251. doi: 10.1080/13501760500451667

- Subotic, Jelena. “Europe is a State of Mind: Identity and Europeanization in the Balkans1.” International Studies Quarterly 55 (2011): 309–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2011.00649.x

- Suchko, Oleksandr. “The Impact of Russia on Governance Structures in Ukraine.” German Development Institute, Discussion Paper 24/2008.

- The Economist. “Russia’s Chief Propagandist.” 10 December 2013.

- Tolstrup, Jacob. “Studying a Negative External Actor: Russia’s Management of Stability and Instability in the ‘Near Abroad’.” Democratization 16, no. 5 (2009): 922–944. doi: 10.1080/13510340903162101

- Tolstrup, Jacob. “When Can External Actors Influence Democratization? Leverage, Linkages, and Gatekeeper Elites.” Democratization 20, no. 4 (2013): 716–742. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2012.666066

- Torbakov, Igor. “Insecurity Drives Putin’s Crimea Response.” EurasiaNet, 3 March 2014.

- Vachudova, Milada Ana. Europe Undivided: Democracy, Leverage and Integration After Communism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Vanderhill, Rachel. Promoting Authoritarianism Abroad. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., 2013.

- Van Herpen, Marcel H. Putin’s Propaganda Machine: Soft Power and Russian Foreign Policy. Lanham and London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2016.

- Von Soest, Christian. “Democracy Prevention: The International Collaboration of Authoritarian Regimes.” European Journal of Political Research 54 (2015): 623–638.

- Way, Lucan A. “The Limits of Autocracy Promotion: The Case of Russia in the ‘Near Abroad’.” European Journal of Political Research 54 (2015): 691–706. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12092

- Way, Lucan A., and Steven Levitsky. “Linkage, Leverage, and the Post-Communist Divide.” East European Politics and Societies 21 (2007): 48–66. doi: 10.1177/0888325406297134

- Weber, Katja, Michael E. Smith, and Michael Baun, eds. Governing Europe’s Neighbourhood: Partners or Periphery? Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007.

- Wendt, Alexander. “The Agent-Structure Problem in International Relations Theory.” International Organization 41, no. 2 (1987): 335–370. doi: 10.1017/S002081830002751X

- Wetzel, Anne, and Jan Orbie. “Promoting Embedded Democracy? Researching the Substance of EU Democracy Promotion.” European Foreign Affairs Review 16 (2011): 565–588.

- Whitman, Richard G. “The Neo-Normative Turn in Theorising the EU’s International Presence.” Cooperation and Conflict 48 (2013): 171–193. doi: 10.1177/0010836713485538

- Whitman, Richard, and Stephen Wolff. The European Neighbourhood Policy in Perspective. Context, Implementation and Impact. Basingstoke: Palgave Macmillan, 2010.

- Wilson, Andrew. “Ukrainian Politics Since Independence.” In Ukraine and Russia: People, Politics, Propaganda and Perspectives, edited by Agnieszka Pikulicka-Wilczewska and Richard Sakawa, 101–108. Bristol: E-International Relations Publishing, 2015.

- Wolczuk, Kataryna, and Roman Wolczuk. “What You Need to Know about the Causes of the Ukrainian Protests.” Monkey Cage, Washington Post, 9 December 2013. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2013/12/09/what-you-need-to-know-about-the-causes-of-the-ukrainian-protests/.

- Woll, Cornelia and Sophie Jacquot. “Using Europe: Strategic Action in Multi-Level Politics.” Comparative European Politics 8, no. 1 (2010): 110–126. doi: 10.1057/cep.2010.7