ABSTRACT

Despite the burgeoning comparative literature on authoritarian elections, less is known about the dynamics of competition in authoritarian subnational elections where opposition is not allowed to organize into parties. Local elections without partisan competition in single-party authoritarian regimes provide considerable advantages to the incumbents and may well turn the incumbent advantage common in liberal democracies into incumbent dominance. What economic factors can break incumbent dominance in such competition without parties? With quantitative and qualitative evidence from grassroots elections in China, this article illustrates that economic growth and industrial economic structure offering more economic autonomy help to break incumbent dominance and increase the prospects of successful challenge to incumbency by non-party outsiders. The examination of the findings in a broad context in China and against the backdrop of local democratization in the developing world suggests that though we may observe successful challenge to incumbency, liberalization of the political system requires not only competition, but also a relatively autonomous economy to sustain liberalization prospects. The findings contribute to the literature on electoral authoritarianism, subnational democratization and China’s grassroots elections.

Introduction

In liberal democracies, incumbents enjoy advantages in their re-election campaign which can be structural – the control they have of the playing field – or communicational – their experience and skill in using language, argument and recognition.Footnote1 Yet, authoritarian elections have a different logic. They are instruments of authoritarian rule, and thus give incumbents considerable power and tools to hollow out the democratic heart of electoral contestation to remain in power.Footnote2 In single-party authoritarian regimes where opposition is not allowed to organize into parties, incumbent advantage can well turn into incumbent dominance. Village elections in China are such a form of political contestation in which candidates who are not members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) are not allowed to organize into political parties and can only run as individuals. Moreover, as local governments emphasize leadership stability in rural governance and policy implementation, incumbent village leaders enjoy considerable advantage in their re-election and may even dominate electoral outcomes.

How should we interpret the incidence of incumbent turnover under a heavily skewed system in favour of incumbents? As Dahl proposed, democracy consists of two dimensions, contestation and inclusiveness.Footnote3 ‘Contestation’ means the extent of opposition and competition permitted in the political system, while ‘inclusiveness’ indicates the proportion of the population entitled to participate in the system of public contestation. For elections to be considered contested and inclusive, they need to have a reasonable turnover rate and a contestation open to the public. Thus, incumbent turnover indicates contestation, while successful challenge to incumbency by opposition outside the ruling party represents a shift towards inclusiveness. In practice, incumbent turnover does not indicate democratization, because the successor may be handpicked by or closely associated with the former ruler or may be even stronger and more authoritarian than the incumbent stepping down.Footnote4 But a successful challenge to incumbency certainly brings uncertainty to the contestation and raises challengers’ expectation about possible electoral victory in the future.

What economic factors can break incumbent dominance in electoral competition without parties? Using electoral data and case study of villages in a county of Guangdong Province in China, with the pseudonym of Liyuan County, this article offers an explanation of why incumbents dominate in some villages but fail in others.Footnote5 The results demonstrate that economic development, as is evident in democratization literature, increases substantially the chance of successful challenges to incumbency, especially by non-party challengers; equally important is another economic condition, a more industrial economic structure, which weakens the economic leverage possessed by authoritarian subnational governments to intervene in electoral contestation and manipulate the outcome.

There are two contributions in this article. First, this article is among the first to bring together the experience of China’s local elections and existing studies on subnational authoritarianism. Despite growing literature on subnational politics and existing literature in the field of Chinese village elections, experience from China’s village elections has not been well incorporated into the literature on subnational authoritarianism. The rise of scholarly attention to subnational democratization is an outcome of the third-wave democratization whereby national democratization transforming politics at the national level creates little pressure for subnational democratization and in some cases leaves subnational authoritarianism intact.Footnote6 China is the opposite combination, being nationally authoritarian while limited contestation of power has been introduced at the subnational levels. China's combination of limited subnational democracy under a nationally authoritarian regime is equally important to our understanding of subnational politics. Moreover, local elections without party competition in the context of single-party authoritarian regimes are quite often considered to be window dressing without any implication for the stability and durability of regimes. Yet, even when competition is structured to the benefit of pro-regime candidates and very poorly conducted, the provision of even limited choices can simultaneously strengthen demands for accountability and loyalty to the regime.Footnote7

Second, this article contributes to existing literature on China’s village elections in that it is the first to treat electoral outcome as a key indicator of the contestation and inclusiveness of village elections. Existing studies of China’s village elections have examined in great detail the variation in procedural quality of the elections, and focused on the degree to which village elections are competitive, that is, with multiple candidates standing for each office or electoral procedure fulfilling standards of liberal democracy, such as secret balloting, one-man-one-vote and fair and transparent ballot counting. However, procedural measurement of village elections, as important as it was, can no longer differentiate the more democratic elections from less democratic ones. For one thing, village elections have been largely standardized since 1998. Moreover, through years of practice local governments have learned how to fake compliance with election regulations and laws.Footnote8 In addition, recent studies of the regime sustainability of CCP rule demonstrate that the Chinese cultural concept of democracy as “guardianship” and the continuing efforts of the CCP to rely on mass mobilization to sustain regime support have weakened the role of formal political institutions and procedures such as elections and civil organizations.Footnote9 The diminished role of elections suggests that the focus of village election study should move away from the formal electoral institutions to more subtle authoritarian domination, that is, focus on electoral outcomes.

This article proceeds as follows. I begin with a discussion of incumbent advantages in China’s village elections. Section three develops hypotheses for statistical analysis based on the literature on both competitive authoritarianism and China’s village elections. The article then proceeds to research design and variable operationalization. Section five presents the statistical results and section six demonstrates how a successful challenge to incumbency works, using a case study of a village. Finally, the article concludes with political implications of the findings.

Incumbent advantage in China’s village elections

Rural residents in China get to choose their leaders at the ballot box. Holding competitive village elections every three years has become mandatory nationwide in 1998 since the promulgation of the Organic Law of Village Committee. Each village committee (VC) normally consists of three to seven members and is headed by a chairman. VCs are responsible for managing village collective resources and specific issues within villages, including, but not limited to, mediating disputes, maintaining social order, providing public goods and developing the village economy.

The 1998 law stipulates that VCs are organs of self-government whereby villagers select and supervise their leaders and decide and manage their own issues. Candidates should be directly nominated by eligible villagers, and all eligible villagers can vote and run for office in the villages they reside in. Elections must be competitive in that the number of candidates running for office should exceed the number of positions available on the VC. An election is valid only if the two majorities – at least 50% voter turnout and at least 50% votes of the turnout received by the winner – are met. If no candidate fulfils these two majorities, the top few candidates with the most votes are selected as the official candidates, and a run-off election will be held to decide the winner.Footnote10

Yet, VCs are not independent kingdoms; instead, they are nested within China’s one-party system and subject to the manipulation of local governments and grassroots party organizations. On the one hand, according to the law, township governments are assigned the duty of implementing and supervising village elections and the CCP’s grassroots organizations – village party committees (VPC) – should exercise leadership over VCs on important matters.Footnote11 In practice, this requirement offers local governments the de jure power to directly intervene in local elections and influence the election results. On the other hand, according to the law, VCs should also support the township governments in carrying out state policies and political tasks. The political careers of township officials depend on meeting performance targets. Thus, if township officials expect that the electoral outcomes will hinder their implementation of performance targets and affect their political career, they are incentivized to adjust the implementation of village elections and fake compliance with the law.Footnote12

In China’s village elections, the key goal for local governments to secure domination is the election of experienced incumbents, because they have a better understanding of the implementation of performance targets crucial to the political careers of upper-level officials. Local officials are assessed based on their performance on a range of performance targets ranked according to level of importance.Footnote13 Compared with new candidates, incumbents with experience of collaborating with township officials have a better understanding of the importance of these performance targets and their implementation. Uncertainty associated with new leadership in rural villages is a risk that rural township officials prefer to avoid when it comes to implementing priority targets. This preference is clearly spelled out in the fifth village election implementation plan issued by Liyuan County government, which states that in order to maintain leadership stability in rural areas, township governments and VPCs should strive to keep the majority of village incumbents re-elected.Footnote14

Incumbents also have a great incentive to run for re-election, as selective incentives are provided by the central government to maintain rural leadership stability. In a series of policies, the central government has called for recruiting incumbents with an excellent performance during their tenure to join the party and giving priority to grassroots officials working at the VC and VPC in the recruitment of township officials, especially VC chairmen and village party secretaries.Footnote15 In Liyuan County, in recruiting township officials, priority is given to candidates who have served in the VC or VPC for at least three terms, especially village party secretaries and VC chairmen.Footnote16 For incumbents, especially those who want to climb up the political ladder, the possibility of political advancement provides strong incentive to seek re-election and accumulate necessary political capital.

Explaining the variation in incumbent re-election in authoritarian elections: theories and arguments

In studies of authoritarian elections, scholars have explored what economic factors explain the variation in electoral authoritarianism at both national and subnational levels.Footnote17 In this section, two factors commonly discussed in the literature – economic development and structure – are introduced in more detail, followed by a discussion of controls for alternative explanations.

Economic development

In democratization literature, economic development is identified as a key factor affecting the development and consolidation of democracy, as increased wealth is often associated with structural conditions, such as a better-educated population, an empowered working class, enlarging size of the middle class, income equality, a diversified economy and industrialization.Footnote18 Yet, in competitive authoritarian regimes, economic growth may have a different effect. It can increase the amount of resources available to incumbents for patronage and public-sector salaries, allowing authoritarian incumbents to maintain their hold on power and strengthen their governance legitimacy.Footnote19 Scholars of China also explore the effect of economic development on village elections, but with different underlying mechanisms. Hu finds that village economic wealth increases the stake villagers have in the election and the rewards candidates obtain from the results of the election, thus greater participation by villagers in elections and more intense electoral competition are witnessed in more economically developed villages.Footnote20 Oi and Rozelle, and Shi find a somewhat negative relationship between economic development and competitive village elections.Footnote21 However, in their studies, economic development is a proxy for village economic structure and thus their studies are discussed in the next section on economic structure.

Studies of China’s local elections do not emphasize selective incentives, such as the spoils of office, because local officials have limited access to state patronage.Footnote22 Yet, the selective benefits can be financial rewards candidates can receive from holding village office, because VCs have control over collective village resources. In addition, selective benefits can also include political advancement from village positions to positions in the township government. Given that economic targets are one crucial criterion for the career advancement of local officials, elected officials in economically well-developed villages have a higher chance of being recruited to township governments. Thus, I expect to find a negative relationship between village economic wealth and incumbent dominance, because village economic wealth incentivizes candidates to join the electoral competition and increases electoral competitiveness.

Economic structure

In the study of local democracy, local economic structure emerges as a crucial local contextual factor shaping the development of local democracy. In competitive authoritarian regimes or poor democracies, local economic opportunities are quite often monopolized by local governments or locally based individuals, families, clans, cliques or organizations, leaving very limited space for opposition activities and giving rise to subnational authoritarianism.Footnote23 If economic well-being and livelihoods of most of the population are dependent on the state, voters tend to support candidates who are endorsed by incumbent elites and opposition forces tend to be coopted in order to maintain power and enjoy the benefits and patronage of holding onto power.Footnote24 Without economic autonomy – opportunities for jobs beyond the reach of local government – citizens and opponents do not have the economic means to protect themselves from governmental harassment in organizing and attending civic activities and are thus less likely to challenge local authorities.Footnote25 For example, revenue centralization in Mexico provides the PRI – the Institutional Revolutionary Party – an important economic tool to threaten localities in support of the opposition and achieve dominance in the electoral outcome.Footnote26

Similarly, in China’s village elections, electoral participation and competition are heavily shaped by village economic structure. Some scholars demonstrate a negative relationship between economic development and competitive village elections and in their accounts economic development is a proxy for economic structure. Shi demonstrates that rapid economic development provides incumbent village leaders incentive and financial resources to coopt voters and hold controlled elections that will guarantee their vested interests in the village.Footnote27 Oi and Rozelle propose a two-dimension continuum to measure village economic structure, one capturing the source of villagers’ income and the other measuring the composition of village wealth on the agricultural–industrial axis.Footnote28 Village leaders in industrial villages have more to lose than their counterparts in agricultural villages and thus have a greater incentive to limit participation. Thus, less competitive village elections are observed in industrial villages and villages with rapid economic development. The key mechanism is the motivation and capability of village leaders to limit participation and hold onto power, and thus the analysis focuses on the village level.

However, I argue that, compared with village incumbent leaders, the township government has considerably more leverage in electoral competition and thus township economic structure plays a major role in incumbent dominance. As mentioned earlier, township governments have the de jure power to directly intervene in local elections and influence the election results if they see fit. They may also have the de facto power to control village elections, because township governments may possess economic resources crucial to the development of the village economy, especially in less developed agricultural areas.

In industrial areas, external sources for village collective income can be rents for commercial and industrial premises paid by businessmen, fees paid by companies setting up their own business in the village or fees paid by outside contractors according to their particular business.Footnote29 Township–village enterprises (TVE) and village collective enterprises are more common in villages of industrial areas. However, in agricultural areas and most inland provinces of China, township governments were not very successful in developing TVEs before the mid-1990s; and they subsequently restructured and privatized TVEs, if there were any, retreating to focusing on their public function.Footnote30 For these villages, the networks and resources possessed by township governments are crucial to development. As part of the village poverty relief programme, local governments are also encouraged to introduce outside investment into poor villages in agricultural areas and to help them develop their economy.Footnote31 In Guangdong Province, for example, rural township and county governments select villages for a provincial investment programme that connects villages to outside investors, such as branches of commercial or state-owned banks, telecommunication companies and government sectors in cities of the Pearl River Delta.Footnote32 The key goal of this programme is to provide financial assistance and develop village economies. Thus, in agricultural areas, township governments have considerably greater economic leverage in influencing electoral competition than their counterparts in relatively industrialized areas. Hence, I argue that villages in industrial towns with lower farming population are more likely to break incumbent dominance, because township governments have less economic leverage to dominate elections.

Controls for alternative explanations

Incumbent advantage in authoritarian elections may be influenced by a number of other factors, most importantly an incumbent’s party connection. Much of the literature on authoritarian elections focuses on how opposition can form coalitions to compete with the authoritarian incumbents and point to the importance of opposition strategy.Footnote33 Yet, in single-party regimes like China where opposition cannot organize into political parties, the organizational strength of the incumbents is crucial to understanding electoral competition. At the national level, strong states and governing parties are often able to prevent elite defection, thwart opposition challenge and coopt or deny resources to opponents.Footnote34

Turning to grassroots elections in China: the organizational power of the village incumbent hinges on their connection to the CCP. Party membership is proven to be one dominant pathway to candidacy in village elections, though it does not guarantee electoral victory.Footnote35 Being a member at the CCP’s local organization, the VPC, can provide incumbents with the power and party resources to win the electoral competition. For one thing, party connection may help incumbents to mobilize support in local elections. As Tang argues, the current Chinese system is a populist authoritarian regime in which the CCP relies on the use of the mass line ideology to generate public support.Footnote36 The key of the mass line ideology is to mobilize the masses in political participation and create direct interaction between state and society, generating a high level of support for the CCP regime, especially the central government. Applying this populist authoritarianism concept to grassroots elections would suggest that the VPCs are granted the responsibility and duty to mobilize support for candidates handpicked by local governments. For example, in the village election implementation plan of Liyuan County, township and village party committees are requested to educate the masses on exercising democratic rights, mobilize the masses to participate in voting and guide the masses to pick qualified candidates in elections.Footnote37 The VPC is also given the de jure power to influence the electoral competition. According to the law, the VPC is required to exercise leadership in both elections and post-election governance.Footnote38 Village and township party committees can also nominate candidates and use the party’s organization network to campaign for their candidates. Thus, I expect that the party connection of the incumbent increases their chance of re-election.

In China’s village elections, incumbent re-election may be influenced by a number of other individual-level and village-level factors. At the individual level, VCs are still dominated by men.Footnote39 The CCP and local governments count on young and educated villagers to vote and participate in village politics, on the one hand, and are keen on socializing and coopting the best-educated youth into the party, on the other hand.Footnote40 Thus, educated, younger and male incumbents may have a higher chance of being re-elected.

At the village level, remoteness – the distance of a village to the county seat – tests the extent of political control by local officials. Earlier studies argue that local officials play a major role in introducing semi-competitive village elections and those closer to county seat should be more likely to have semi-competitive elections; while Shi found the opposite effect – that the further a village is away from the county seat, the more likely that elections in the village will be semi-competitive.Footnote41 If local officials play a major role in facilitating incumbent re-election, there should be a negative relationship between remoteness and the likelihood of an incumbent being re-elected. Village population may also have an effect on incumbent re-election, as voting is essentially a collective action. In China’s villages, the size of villages can range from a few hundred people to tens of thousands.Footnote42 Challengers in villages with larger populations may require more effort and resources to mobilize popular support, making it harder to win the elections. Inequality, as has been well documented in modernization literature, may affect regime transition and stability, while in China’s village elections, inequality, indicated by the percentage of villagers relying on poverty relief subsidies from the government, represents incumbents’ economic performance. A high inequality rate may well diminish the competitive advantage enjoyed by incumbents in elections.

As for the effect of local clans, in Liyuan County a common characteristic shared by all villages is the existence of lineage groups. It is embodied in the local culture in the way that people group together under a common ancestor and each village has one ancestral hall for holding ceremonies on a few fixed dates of the year to worship the common ancestor. Thus, there is limited variation among villages in the number and the fragmentation of local clans. Finally, concerning the township leaders’ attitudes towards incumbent re-election, re-election rate is one key measure of the performance of township leaders on the implementation of village elections and each township government is required to report this figure back to the county government in Liyuan County. Thus, township leaders’ preference towards incumbents are unlikely to differ substantially in Liyuan County.

In order to tease out the effects of these controls on incumbent re-election, I controlled for the incumbent’s party connection, age, gender and education at the individual level, and population, remoteness and percentage of poor at the village level.

Research design and variable operationalization

To understand the factors associated with incumbent re-election and the dynamics of electoral competition in China’s village elections, I adopt a mixed methods approach. Enquiry about the dynamics of political competition in village elections is considered politically sensitive by local officials in China and it requires networks and trust to gain access to local governments. A rural county in Guangdong Province – Liyuan County – is thus selected. I worked as an observer of village elections in the Liyuan County Civil Affair Bureau responsible for supervising village elections for three months in the election year of 2008, which helped me to establish the networks and trust essential for an in-depth study of the electoral dynamics. In addition, within Liyuan County, there is variation among villages at the village level regarding economic wealth, township economic structure, individual incumbents’ social demographic characteristics and village demographic characteristics, a fact that serves the research purpose of this article.

Although the findings are based on one county and may not be applicable to other places within China, Liyuan County does represent the general and average situation of China’s inland rural counties. Despite being located in Guangdong – one of the most economically developed and industrialized provinces of China – Liyuan is a typical non-coastal agricultural county like other rural counties in inland provinces of China. In Liyuan County, 84.67% of the total population work in agriculture. In terms of per capita annual net income of rural households, Liyuan County is in the lower quantile in Guangdong and thus closer to the national average. In 2006, the national average was ¥3587.04, while the average of Liyuan County was ¥3987.Footnote43

I did extensive fieldwork in Liyuan for about 18 months between 2008 and 2011 and collected both quantitative data and qualitative evidence from interviews. The quantitative data consist of results of two election cycles held in 2008 and 2011 and village economic and demographic data of 237 villages in the 15 townships of the county.Footnote44 In the case study section, Centre Village was selected to demonstrate how successful challenges to incumbency work. Various actors, including previous VC chairmen and members and county and township government officials, were interviewed to gather information about electoral competition in Centre Village in previous elections since 2005.

In terms of the sample for the regression analysis in this article, the sample includes only data on incumbents. The local governments do not collect detailed information of all candidates running for village elections; instead, they collect and store detailed information of elected VC chairmen and members in each election year. By comparing the list of elected VCs over two election years, I can identify re-elected incumbents and successors to those incumbents who failed to be re-elected. In China’s village elections, incumbent re-election rate is a key quantifiable indicator that can be used to assess local governments’ performance in the implementation of village elections, and thus in practice incumbent VC chairmen are always considered candidates in electoral competition.Footnote45 Local governments emphasize the re-election of the head position in VCs, thus the regression analysis focuses on the re-election of VC chairmen. Before moving to the statistical results, I shall introduce how variables are operationalized.

Dependent variables

The analysis examines the variation in incumbent re-elections in China’s village elections. I collected information about VC chairmen elected in 2008 and in 2011 in the sample county, including their gender, education, age, party affiliation and connection with the VPC. By comparing election results in 2008 and 2011, I can identity re-elected incumbents and successors to those incumbents who failed to be re-elected in 2011.

There are two types of dependent variables in the regression analysis capturing two dimensions of democracy proposed by Dahl, contestation and inclusiveness.Footnote46 Contestation and inclusiveness in the Chinese context mean that incumbents should face not only the possibility of being replaced but also the possibility of being replaced by non-party-member challengers. Among the 237 incumbent chairmen elected in 2008, 50% were re-elected to the chairman position in 2011, a reasonable turnover rate even compared with the turnover rate in liberal democracies. Yet, among the 50% incumbent VC chairmen who were not re-elected, 56% were replaced by party members and 44% were replaced by non-party-member challengers. The first dependent variable is a dummy variable – whether the VC chairmen elected in 2008 was re-elected in 2011 – as a proxy of contestation and binary logistic regression is used to analyse the data. The second dependent variable is a categorical one – whether the VC chairmen elected in 2008 was re-elected, replaced by a party member or replaced by a non-party outsider in 2011 – as a proxy of inclusiveness and multinomial logistic regression is used with an incumbent being replaced by a non-party candidate as the base outcome.

Independent variables

To capture the lucrative benefit associated with the VC head position, I measure village wealth using the log transformation of village collective business wealth generated through the business activities of the VCs in the first six months of 2011. In 2011, village elections in Liyuan were held between March and June. Business revenue generated in the months close to elections should have a very strong signalling effect on potential candidates’ decision to join the competition.

Similarly to Oi and Rozelle, I also measure economic structure on the agricultural–industrial axis;Footnote47 but I apply this axis at the township level and use the percentage of farming population at the township level to proxy the extent to which villages rely on township governments for economic development. A high percentage of township farming population indicates that agriculture remains the core source of village collective revenue and villages remain largely reliant on township governments’ financial and policy support to generate collective wealth, offering local governments considerable economic leverage to manipulate the elections. The most updated figure before the 2011 village elections was calculated in 2008 and from 2008 to 2011 there was no major restructuring and development programme in the county which would have changed this figure dramatically.

Control variables

All regression models additionally controlled for the incumbent’s party connection, age, age squared, gender and education at the individual level, and population, remoteness and percentage of poor at the village level. Both the CCP’s mass mobilization strategy and the elections law have given the VPC networks, resources and de jure power to mobilize support in elections, and thus I use the incumbent’s VPC membership in 2008, percentage of village party members and incumbent’s CCP membership prior to the election in 2011 to proxy the incumbent’s party connection and access to party organizational resources. shows the descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Statistical results and discussion

shows the coefficients (likelihood estimates). In model 1 with the dummy dependent variable of whether the incumbent chairman was re-elected in 2011, economic wealth has a statistically significant negative effect on incumbent re-election. Villages in towns with higher farming population – more agricultural economic structure – are more likely to have incumbents re-elected, significant at the 0.05 level.

Table 2. Explaining incumbent re-election and replacement.

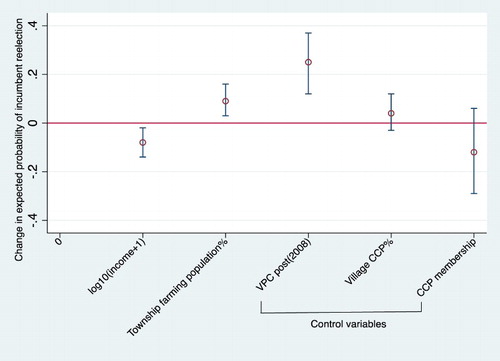

In order to compare the relative strength of the independent variables, shows the change in expected probability of incumbent re-election in model 1 when each continuous independent variable increases by one standard deviation from its mean and each dichotomous variable changes from 0 to 1 while all other variables are held constant at their mean. In the figure, the average expected probability is highlighted along with the associated confidence intervals at the 0.1 level.Footnote48 As illustrates, one standard deviation increase from the mean in village business wealth decreases the re-election of incumbents by 8%. One standard deviation increase from the mean in township farming population percentage increases the re-election of incumbents by 9%. These results support the arguments. Village business wealth incentivizes candidates to enter the electoral competition, thus making it harder for incumbents to be re-elected, while in agricultural towns incumbents are more likely to be re-elected given villages’ economic dependency on township governments.

Because the incumbent’s party connection and access to party organizational resources are important control variables, also indicates their effects on the probability of incumbent re-election. Holding VPC posts makes incumbents 25% more likely to be re-elected, significant at the 0.01 level, while the size of the party network and the party affiliation of the incumbent have no statistically significant effect on incumbent re-election. This is consistent with the empirical findings from a household survey in a rural county of Yunnan Province by Landry, Davis and Wang that party membership did not guarantee electoral victory.Footnote49 Taking this further, the findings of this article suggest that party membership of the incumbent and size of village party network do not guarantee incumbent re-election, but sitting in the VPC does increase incumbent advantage substantially and may well enable incumbents to dominate electoral outcome.

Model 2 in tests the inclusiveness dimension of village elections with an incumbent being replaced by a non-party candidate as the base outcome.Footnote50 The key focus is incumbent re-election vis-à-vis successful challenge by non-party candidates. Similar patterns are observed. In model 2, holding all other variables constant, one standard deviation increase from the mean in village wealth increases the probability of successful challenge by non-party candidates from 20% to 25% but decreases the probability of incumbent re-election from 52% to 44%. Similarly, one standard deviation increase from the mean in township farming population decreases the probability of a successful challenge by non-party candidates by 5% and increases the probability of incumbent re-election by 7%. In other words, the odds of a successful challenge by non-party candidates in comparison with incumbent re-election are higher in wealthier villages and in villages of industrial towns with a lower farming population percentage. In addition, among party connection variables, being a VPC member decreases substantially the probability of a successful challenge to incumbency by non-party candidates by 13%.

The regression results show that increasing village wealth and more industrial township economic structure not only decrease the probability of incumbent re-election, but also increase the probability of successful challenge to incumbency by non-party candidates. These results support the arguments. Village wealth incentivizes candidates, especially non-party candidates, to run for electoral competition, increasing the difficulty of incumbent re-election. In industrial towns with lower farming population where villages have more independent sources of collective revenue, local governments have lost important economic leverage to intervene in electoral competition and thus incumbents are more likely not only to fail to be re-elected but also to be replaced by non-party challengers. These mechanisms behind the relationship between economic factors and incumbent re-election are illustrated by a case study of a village in Liyuan County in the next section.

Centre village: a successful case of challenge to incumbency

In this section, I illustrate how a successful challenge to incumbency works. Centre Village experienced fierce electoral competition and successful challenges to incumbency in the three elections since 2005.Footnote51 In the three election years of 2005, 2008 and 2011, all incumbent VC chairmen were not party members; all ran for re-election campaign but failed to be re-elected; and all were replaced by non-party challengers. A close look at the dynamics of electoral competition in this village reveals the strategies used by both challengers and incumbents and demonstrates how economic factors affect the effectiveness of these strategies.

Centre Village is one of the wealthiest villages in terms of the amount of collective village resources possessed by the VC. In the early 2000s, there was major urbanization and industrial development in the county centre. During the early stage of this development, the VC of Centre Village generated a large amount of revenue through selling collective lands to both the county government and outside investors. Since major construction of the industrial development was completed in 2008, the VC has relied financially on subletting collective lands and properties.Footnote52 Possessing wealthy land and property resources provides strong selective incentives for candidates to join the electoral competition in Centre Village. The potential lucrative benefits one can pocket from the collective revenue is one lure for candidates to enter the electoral competition. Further, because the VC has direct contacts with various outside investors when utilizing village collective resources, holding VC offices can also help the officer-holders to accumulate network resources for their own business interests. Third, if a candidate can be continuously elected to the VC chairman position for three terms and given that Centre Village is one of the most developed villages in the county, the candidate will be given priority in the recruitment of township government officials. Potential rewards, either financial or political, attract challengers from both within and outside the CCP to compete for the VC chairman position in Centre Village, increasing the difficulty for the local government to achieve incumbent dominance.

Lucrative potential rewards make challengers resort to vote-buying practices. Vote-buying has been prevalent in Centre Village’s past electoral competition. In 2005, the competition between different groups led to a fight causing one death and several injuries. In 2008, a non-party challenger was elected after spending around ¥500,000 (US$81,967.21) on buying votes and villagers who voted for him received ¥100 (US$16.39) per ballot ticket.Footnote53 In 2011, the incumbent VC chairman elected in 2008 sought re-election. However, a non-party challenger won the VC chair position after spending some money on vote-buying.Footnote54 It is stated explicitly in the Guangdong Provincial internal policy documents that vote-buying and voter intimidation are strictly prohibited. Yet, in practice, to prove a candidate guilty of vote bribery or voter intimidation requires solid and direct evidence, which is difficult to obtain.Footnote55 Local governments cannot engage in similar vote-buying practice to outbid the challengers, because it is prohibited in the provincial policy documents to do so and the local government does not have the financial resources to engage in vote-buying.

For a local government, a cost-effective mechanism to achieve incumbent re-election is to rely on the economic leverage they have over village economic development. If villages rely on local governments to introduce economic development opportunities, local governments have considerable power to persuade or even threaten challengers to drop out of the electoral competition. Yet, this proves ineffective in villages of industrial townships. As a village party secretary has revealed,Footnote56

In those industrial towns with more private economic opportunities, it is very difficult to guide the elections towards local government’s intention, because these villages have their own development sources and they are not afraid of local government. They don’t count on the local government for any economic support and they also don't worry that their economic gains might be damaged if they don't follow the instructions from local governments.

Conclusion

Local elections without partisan competition in single-party authoritarian regimes provide considerable advantages to the incumbents and may well turn incumbent advantage common in liberal democracies into incumbent dominance. This article illustrates, with evidence from grassroots elections in China, that economic wealth can provide substantial selective incentives and lucrative benefits to attract competitors, while a more industrial economic structure, providing villages with independent economic development opportunities, weakens the economic leverage possessed by local governments to intervene in electoral competition and manipulate the outcome. Thus, growing economic wealth and decreasing farming population are likely to break incumbent dominance and increase the probability of successful challenges to incumbency by candidates from outside the CCP. The case study further demonstrates that lucrative benefits incentivize candidates to engage in vote-buying, while industrial economic structure has made local governments lose the important economic leverage they have to persuade or even threaten challengers to drop out of the electoral competition, thus giving rise to successful challenges to incumbency.

Given the importance of the CCP’s mass mobilization strategy and rule in China, the regression analyses also control for the incumbent’s party connection. Among these variables, the article finds that party membership of the incumbent and size of village party network do not affect incumbent re-election, but being a member of the VPC – the party’s grassroots organization – does substantially increase the probability of incumbent re-election. This may be related to the leadership status of the VPC in grassroots villages. This suggests that an effective strategy for incumbents to remain in power is to sit in the VPC. In order to be a member of the VPC, one needs to be a CCP member; and thus for non-party-member incumbents to maintain power, being coopted into the party and becoming a VPC member is a very attractive option. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss elite cooptation in China’s village elections. Future research can probe further in this direction, for example, the impact of elite cooptation on intra-party democracy starting from the grassroots levels.

The findings need to be examined in a broader Chinese context in order to understand the political implications. Competitive elections are only introduced in rural villages in China where the local economic structure is predominantly agricultural. In the majority of these areas, key economic resources are controlled by the local government and thus elections serve to guarantee incumbent advantage or even dominance most of the time. Yet, in recent decades, China has experienced rapid urbanization, which may break local governments’ monopoly over economic resources, thus bringing more successful challenges to incumbency in Chinese grassroots elections. I suspect that such a positive prospect, involving the urbanization of the suburban rural villages, may lead to rural villages being absorbed into cities, where direct election for the governance body will no longer be applicable. This transformation happened to an urbanized county neighbouring Liyuan and in cities in the Pearl River Delta, which I observed in 2008. This suggests that it is unlikely that village elections will bring genuine democratization in China, as these elections are mainly introduced in rural villages where economic conditions strengthen party dominance, and governments can always rein in the potential democratization effect of such reform in authoritarian regimes.

This leads to the last but in no way least important point, the logic of local democratization in authoritarian regimes and the political implications of the findings beyond China. Conventional wisdom considers local democratization a useful means to provide local actors with more power and autonomy. Yet, as Bohlken has argued, in the developing world local democratization is driven by the desire of government elites to consolidate their power and monitor and discipline local elites.Footnote58 Village elections in China are such a type of local democratization from above, as commonly observed in the developing world, especially in authoritarian regimes. Keeping this in mind, it is not surprising to find that local elections are quite often introduced without promoting local fiscal and economic autonomy. Without economic independence, local elections will only serve as a mechanism of manipulation by the state, rather than as “rule by the people”. This suggests that though we may observe successful challenge to incumbency in local elections, liberalization of the political system requires not only competition but also a relatively autonomous economy to sustain the prospects of liberalization.

Acknowledgements

For insightful comments, feedback and suggestions for revisions, the author would like to thank the editors of this journal, the two anonymous reviewers, Brenda van Coppenolle, Jean-Paul Faguet, Pei Gao, Simon Hix, Yu-Hsiang Lei, Lianjiang Li, Guoer Liu, Aofei Lu, John T. Sidel, Dorothy J. Solinger, Daniela Stockmann and seminar participants at the London School of Economics (LSE) and Political Science and Leiden University. Special thanks go to the late Mayling Birney (1972–2017) for her generous support and guidance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ting Luo

Ting Luo is a post-doctoral fellow in the Institute of Political Science of Leiden University and currently working on the European-research-council (ERC)-funded research project on “Authoritarianism 2.0: The Internet, Political Discussion, and Authoritarian Rule in China”. She received her PhD in government from LSE. Her research interests include comparative politics with a specialization on China, election and democratization, and digital politics.

Notes

1. Leuprecht and Skillicorn, “Incumbency Effects”.

2. Schedler, “The Menu of Manipulation”; “The Logic of Electoral Authoritarianism”.

3. Dahl, Polyarchy.

4. Howard and Roessler, “Liberalizing Electoral Outcomes”.

5. Researching local governments’ techniques and strategies of manipulating and influencing village elections is deemed sensitive in China and thus the county will be indicated by a pseudonym throughout this article.

6. Gibson, “Boundary Control”.

7. Manion, “The Electoral Connection”; Landry et al., “Elections in Rural China”; Brandt and Turner, “The Usefulness”.

8. Levy, “Village Elections in China”; O’Brien and Han, “Path to Democracy”; Wang, Tamed Village “Democracy”.

9. Shi, The Cultural; Tang, Populist Authoritarianism.

10. The number of candidates selected for the run-off elections is usually one or two more than the number of seats. On the ballot ticket, voters are also allowed to write down the name of a person who is not listed.

11. The 1998 law was vague on the “leadership core” status of VPCs; the revised law promulgated in 2010 made it explicit that the “leadership core” status of grassroots party organizations means leading and supporting the work of VCs. See also Guo and Bernstein, “The Impact”.

12. Birney, “Decentralization”.

13. Edin, “Remaking”; Birney, “Decentralization”.

14. Liyuan County Civil Affairs Bureau, “The 5th Village Election Implementation Plan of Liyuan County”, internal document, October 2010.

15. “Notice on How to Further Improve the Implementation of Village Committee Elections”, 2002, http://cpc.people.com.cn/GB/64162/71380/102565/182143/10993618.html; “The 20th Notice about How to Improve the Implementation of Village Committee Elections”, 2009, http://fuwu.12371.cn/2013/01/07/ARTI1357528637829211.shtml; “No.1 Central Document by the CCP Central Committee and the State Council”, 2007, http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/yhwj2017/wjhg_1/201301/t20130129_3209959.htm; “No.1 Central Document by the CCP Central Committee and the State Council”, 2008, http://www.moa.gov.cn/ztzl/2016zyyhwj/hgyhwj/201301/t20130129_3209960.htm; “Notice on Comments Regarding Recruiting Township Civil Servants from Excellent Village Cadres”, 2008, http://www.hb.hrss.gov.cn/hbwzweb/html/zcfg/zcfgk/53557.shtml; “Notice on Comments Regarding Strengthening Township Governments’ Governance Capability”, 2017, http://www.mca.gov.cn/article/yw/jczqhsqjs/xzjs/gzdt/201702/20170200003329.shtml.

16. Interview with the deputy head of Liyuan County Civil Affairs Bureau, August 2009.

17. For studies drawn upon subnational evidence: Sidel, “Economic Foundations”; Saikkonen, “Variation”; for studies focusing on national level regime transition: Howard and Roessler, “Liberalizing Electoral Outcomes”; Levitsky and Way, “The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism”; Competitive Authoritarianism.

18. Lipset, “Some Social Requisites”; “The Social Requisites”; Boix and Stokes, “Endogenous Democratization”; Przeworski, “Self-Enforcing Democracy”.

19. Levitsky and Way, “The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism”; Competitive Authoritarianism; Howard and Roessler, “Liberalizing Electoral Outcomes”.

20. Hu, “Economic Development”.

21. Shi, “Economic Development”; Oi and Rozelle, “Elections and Power”.

22. Gandhi and Lust-Okar, “Elections under Authoritarianism”.

23. McMann, Economic Autonomy and Democracy; Sidel, “Economic Foundations”.

24. Levitsky and Way, “The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism”; Competitive Authoritarianism; Way, “Authoritarian State Building”.

25. McMann, Economic Autonomy and Democracy.

26. Diaz-Cayeros et al., “Tragic Brilliance”.

27. Shi, “Economic Development”.

28. Oi and Rozelle, “Elections and Power”.

29. Saich and Hu, Chinese Village.

30. For a discussion about TVEs’ development before the mid-1990s and TVE restructuring and privatization after the mid-1990s, please see Lin et al., “Decentralization and Local Governance in the Context of China's Transition”.

31. Wang, “Target Poverty Relief”.

32. The State Council's Poverty Relief Office, The Yearbook of China's Poverty Alleviation and Development in 2010; interview with a township vice-party-secretary, July 2011; interview with the deputy head of the county finance bureau, August 2011; interview with deputy head of the county civil affairs bureau, August 2009.

33. For example, see Howard and Roessler, “Liberalizing Electoral Outcomes”.

34. Levitsky and Way, “The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism”.

35. Landry et al., “Elections in Rural China”.

36. Tang, Populist Authoritarianism.

37. Liyuan County Civil Affairs Bureau, “The 5th Village Election Implementation Plan of Liyuan County”.

38. The National People's Congress, “The Organic Law”.

39. Howell, “Prospects for Village Self-Governance in China”.

40. Landry et al., “Elections in Rural China”.

41. Shi, “Economic Development”.

42. Birney, “Can Local Elections”.

43. From 2008 yearbook of the municipal city where Liyuan County is located; national and provincial figures accessed at http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2009/indexch.htm.

44. The county has 16 towns in total. One town is excluded from the sample because of missing data. This town suffered flooding in 2008 and thus data on 2008 village elections are missing. The town is not more vulnerable to floods than other towns in the county. Moreover, in terms of economic development and economic structure, this town does not stand out as an extreme case. Thus, the exclusion of this town should not affect the empirical findings.

45. For example, in Liyuan County township governments are assessed on their performance in the village incumbent re-election rate. And they need to report the rate to the county government.

46. Dahl, Polyarchy.

47. Oi and Rozelle, “Elections and Power”.

48. The moreClarify programme is used to draw this figure. See King et al., “Making the Most”.; Márquez Peña, “moreClarify”.

49. Landry et al., “Elections in Rural China”.

50. The more Clarify programme is used to estimate these probabilities.

51. The first election in the county was in 1999 and the second in 2002. According to the county civil affairs bureau, because it was the very beginning of the grassroots electoral reform in Guangdong, potential challengers remained hesitant to run and competition was not fierce at all. Thus, a large percentage of incumbents who were appointed to the position before 1999 were re-elected to the VC chairman position in the first two elections in 1999 and 2002.

52. Interview with a former VC member in Centre Village, July 2011.

53. Interview with the father of the chairman of Centre Village elected in 2008, August 2009.

54. Interview with a former VC member in Centre Village, July 2011.

55. Interview with the head of the rural governance office of the county-level civil affairs bureau, July 2011.

56. Interview with the village party secretary of a village in a neighbouring town, July 2011.

57. Interview with a former VC member in Centre Village, July 2011; interview with the VC chairman elected in 2008 in Centre Village, November 2009.

58. Bohlken, Democratization from Above; Luo, “Democratization from Above”.

Bibliography

- Birney, Mayling. “Can Local Elections Contribute to Democratic Progress in Authoritarian Regimes?: Exploring the Political Ramifications of China’s Village Elections.” PhD diss., Yale University, 2007.

- Birney, M. “Decentralization and Veiled Corruption under China’s ‘Rule of Mandates.’” World Development 53 (2014): 55–67. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.01.006.

- Bohlken, A. T. Democratization from Above: The Logic of Local Democracy in the Developing World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

- Boix, C., and S. C. Stokes. “Endogenous Democratization.” World Politics 55 (2003): 517–549. doi:10.1353/wp.2003.0019.

- Brandt, L., and M. A. Turner. “The Usefulness of Imperfect Elections: The Case of Village Elections in Rural China.” Economics & Politics 19, no. 3 (2007): 453–480. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0343.2007.00316.x.

- Dahl, R. A. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973. https://books.google.nl/books?id=JcKz2249PQcC.

- Diaz-Cayeros, A., B. Magaloni, and B. Weingast. “Tragic Brilliance: Equilibrium Party Hegemony in Mexico.” SSRN Electronic Journal, 2003. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1153510.

- Edin, M. “Remaking the Communist Party-State: The Cadre Responsibility System at the Local Level in China.” China: An International Journal 1, no. 1 (2003): 1–15.

- Gandhi, J., and E. Lust-Okar. “Elections under Authoritarianism.” Annual Review of Political Science 12, no. 1 (2009): 403–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060106.095434.

- Gibson, E. L. “Boundary Control: Subnational Authoritarianism in Democratic Countries.” World Politics 58, no. 1 (2005): 101–132. doi: 10.1353/wp.2006.0018

- Guo, Z., and T. P. Bernstein. “The Impact of Elections on the Village Structure of Power: The Relations between the Village Committees and the Party Branches.” Journal of Contemporary China 13, no. 39 (2004): 257–275. doi:10.1080/1067056042000211898.

- Howard, M. M., and P. G. Roessler. “Liberalizing Electoral Outcomes in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes.” American Journal of Political Science 50, no. 2 (2006): 365–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00189.x

- Howell, J. “Prospects for Village Self-governance in China.” Journal of Peasant Studies 25, no. 3 (1998): 86–111. doi:10.1080/03066159808438676.

- Hu, R. “Economic Development and the Implementation of Village Elections in Rural China.” Journal of Contemporary China 14, no. 44 (2005): 427–444. doi:10.1080/10670560500115234.

- King, G., M. Tomz, and J. Wittenberg. “Making the Most of Statistical Analyses: Improving Interpretation and Presentation.” American Journal of Political Science 44, no. 2 (2000): 347–361. doi:10.2307/2669316.

- Landry, P. F., D. Davis, and S. Wang. “Elections in Rural China: Competition without Parties.” Comparative Political Studies 43, no. 6 (2010): 763–790. doi:10.1177/0010414009359392.

- Leuprecht, C., and D. B. Skillicorn. “Incumbency Effects in U.S. Presidential Campaigns: Language Patterns Matter.” Electoral Studies 43 (2016): 95–103. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2016.05.008.

- Levitsky, S., and L. A. Way. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan A. Way. “The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism.” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 2, (2002): 51–65. doi:10.1353/jod.2002.0026.

- Levy, Richard. “Village Elections in China – Democracy or Façade?” New Politics XII, no. 4 (2010). http://newpol.org/content/village-elections-china-democracy-or-fa%C3%A7ade.

- Lin, J. Y., R. Tao, and M. Liu. “Decentralization and Local Governance in the Context of China’s Transition.” Perspectives 6, no. 2 (2005): 25–36.

- Lipset, S. M. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” American Political Science Review 53, no. 1 (1959): 69–105. doi:10.2307/1951731.

- Luo, Ting. “Democratization from Above: The Logic of Local Democracy in the Developing World, by Anjali Thomas Bohlken.” Democratization 25 (2018): 574–576. doi:10.1080/13510347.2017.1293042.

- Manion, M. “The Electoral Connection in the Chinese Countryside.” American Political Science Review 90, no. 4 (1996): 736–748. doi:10.2307/2945839.

- McMann, Kelly M. Economic Autonomy and Democracy: Hybrid Regimes in Russia and Kyrgyzstan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511510281.

- O’Brien, K. J., and R. Han. “Path to Democracy? Assessing Village Elections in China.” Journal of Contemporary China 18, no. 60 (2009): 359–378. doi:10.1080/10670560902770206.

- Oi, J. C., and S. Rozelle. “Elections and Power: The Locus of Decision-making in Chinese Villages.” The China Quarterly 162 (2000): 513–539. http://www.jstor.org/stable/656019. doi: 10.1017/S0305741000008237

- Przeworski, Adam. “Self-enforcing Democracy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Economy, edited by Donald A. Wittman and Barry R. Weingast, 312–328. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199548477.003.0017.

- Saich, Tony, and Biliang Hu. Chinese Village, Global Market: New Collectives and Rural Development. China in Transformation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2012. https://books.google.nl/books?id=LOw6roudzYYC.

- Saikkonen, I. A.-L. “Variation in Subnational Electoral Authoritarianism: Evidence from the Russian Federation.” Democratization 23, no. 3 (2016): 437–458. doi:10.1080/13510347.2014.975693.

- Schedler, Andreas. “The Logic of Electoral Authoritarianism.” In Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition, edited by Andreas Schedler, 1–16. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 2006. doi:10.1002/9781118900772.etrds0098.

- Schedler, A. “The Menu of Manipulation.” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 2 (2002): 36–50. doi:10.1353/jod.2002.0031.

- Shi, T. “Economic Development and Village Elections in Rural China.” Journal of Contemporary China 8, no. 22 (1999): 425–442. doi:10.1080/10670569908724356.

- Shi, T. The Cultural Logic of Politics in Mainland China and Taiwan. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014. https://books.google.nl/books?id=HI9EBQAAQBAJ.

- Sidel, J. T. “Economic Foundations of Subnational Authoritarianism: Insights and Evidence from Qualitative and Quantitative Research.” Democratization 21, no. 1 (2014): 161–184. doi:10.1080/13510347.2012.725725.

- Tang, W. Populist Authoritarianism: Chinese Political Culture and Regime Sustainability. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. https://books.google.nl/books?id=wEIFCwAAQBAJ.

- The State Council’s Poverty Relief Office. Zhongguo Fupin Kaifa Nianjian 2010 [ The Yearbook of China’s Poverty Alleviation and Development in 2010]. Beijing: Chinese financial & Economic Publishing House, 2010.

- Wang, G. Tamed Village “Democracy”: Elections, Governance and Clientelism in a Contemporary Chinese Village. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 2014.

- Wang, Xiaoyi. “Jingzhun Fupin Yu Zhucun Bangfu.” [Target Poverty Relief and Poverty Relief with Officials Stationing in the Village]. Journal of China National School of Administration, 2016. http://www.ndrc.gov.cn/fzgggz/jyysr/zcyj/201607/t20160729_813513.html.

- Way, L. A. “Authoritarian State Building and the Sources of Regime Competitiveness in the Fourth Wave: The Cases of Belarus, Moldova, Russia, and Ukraine.” World Politics 57, no. 2 (2005): 231–261. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25054293. doi: 10.1353/wp.2005.0018