ABSTRACT

In research on authoritarian institutions, legislatures are portrayed as capable of resolving dilemmas between the leader and opposition members. Nevertheless, repeated interactions between a leader and their ruling coalition can lead to both contested dictatorships, in which institutions constrain the leader, and established dictatorships, in which the leader exercises near-complete control. To date, however, no one has examined the patterns by which powers vary across legislatures in different settings and over time. Using data from the Varieties of Democracy Project on legislative powers between 1900 and 2017, we conceptualize changes in the powers afforded to the national congress to characterize the development of regimes in either direction. The study expounds on the content of legislatures across regimes and the ways in which they change, encouraging scholars to further consider the relationship between regime dynamics and legislative institutionalization.

Introduction

Given the prominence of legislatures around the world and their central place in the dynamics of nondemocratic rule, it is surprising that few have concentrated on the ways in which legislatures are empowered or disempowered. Even more surprising is the extent to which we lack basic studies that examine how the content of legislative powers differs across regimes. Cross-nationally, we know very little about how powerful legislatures actually are or what the process of legislative strengthening looks like. This represents a weakness of comparative legislative studies, particularly for understanding the role of institutions in sustaining nondemocracies and initiating democratization. This article takes an important step in addressing this problem by elucidating on comparative differences in legislative powers across democracies and nondemocracies alike.

Building on existing work by scholars to measure and compare legislative strength, we utilize cross-national data from the Varieties of Democracy Project and offer a descriptive account of both the kinds of legislative powers that are observable across regimes and the ways in which they change.Footnote1 We seek to answer some basic questions that, though crucial to the literature, have yet to be explored: Do legislatures possess similar powers across the same regions and regime types? Are the differences between democracies and nondemocracies reflected in the powers of their respective legislatures? Our descriptive approach to answering these questions supports the goal of treating descriptive inference as an independent and complementary tool of political science research – one that aims to establish the validity of the data for empirically evaluating legislative strength in nondemocracies.Footnote2

Though descriptive, our analysis provides valuable findings regarding legislative powers across regimes and highlights the importance of conceptualizing legislative institutionalization. We show that when legislatures lose or accrue power, they do so incrementally rather than drastically. We demonstrate that the number of legislative powers is strongly correlated with electoral democracy but shows greater variation among less democratic countries. The cumulative number of powers is related to the types of powers that we observe, with less powerful legislatures first assuming basic parliamentary functions and acquiring “consultative” powers. There are also notable regional differences, such as parliaments in Latin America trailing behind those in Western Europe and North America but exhibiting considerable strength relative to other parts of the world. By exploring the interrelation of democraticness and legislative strength, we find patterns that conform to theoretical models in which interactions between the executive and the ruling coalition produce different types of nondemocracies.

By drawing attention to legislative powers, our study encourages scholars to more seriously consider them when evaluating the relationship between legislative institutionalization and nondemocratic performance. Our analysis exemplifies ways of using newly released data to build upon approaches that measured legislative strength as an index of powers.Footnote3 We also evaluate the data against multiple different measures of democracy, both continuous and dichotomous, to demonstrate its validity across measures. In the following sections, we summarize extant research on the topic of legislatures in nondemocratic regimes. We then outline our approach to depicting legislative powers and present descriptive findings that offer guidance for future research that accounts for comparative differences in legislatures. By paying greater attention to the substance of legislatures as well as the ways in which they change over time, we argue that research on the institutions that undergird regimes can get a better grasp on explaining outcomes that result from them.

Comparing legislatures across regimes

Despite its close ties to democratic practices, scholars note that parliaments are ubiquitous across all regimes. With the exception of the years that encompassed the major world wars, more than half of all countries had a legislature over the last century according to the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.Footnote4 The proportion of countries with a legislature surpassed 0.75 in 1950 and 0.9 in 1990; today, virtually every country in the world is listed as having a legislature (Figure B-1 in Online Appendix B). This trend has motivated scholars to explain why legislatures have been so widely adopted by durable authoritarian regimes. Once dismissed as a mere façade – a rubber stamp giving the appearance of legitimacy to the ruler’s decisions – research has now shown that legislatures are, in fact, important pillars of stability in authoritarian regimes.Footnote5 The formalization of opposition in authoritarian regimes – their inclusion in formal political institutions – is also associated with a variety of “positive” outcomes, such as increased regime longevity, a decreased risk of conflict, and greater investment.Footnote6 The emerging picture from this research underscores the claim that rather than being “less-perfect versions of their democratic counterparts … under dictatorship, nominally democratic institutions serve quintessentially authoritarian ends.”Footnote7 In other words, dictators do not survive in spite of parliaments but because of them.

While our understanding about the purpose of the legislature in authoritarian settings has certainly improved, scholars have yet to explore the ways the strength of the legislature varies across regimes and across time. Consider, for example, Venezuela's President Nicolas Maduro. Amid an economic crisis, the opposition in the National Assembly initiated a referendum in 2016 to impeach him. Maduro responded to the threat not only by shutting down the National Assembly, but also by calling for an overhaul to the constitution to allow him to circumvent the National Assembly on a permanent basis.Footnote8 Instances like these highlight the often fragile environment in which parliaments and executives coexist. Parliaments may very well serve important functions in authoritarian regimes, but the powers they possess make them a double-edged sword. On the one hand, the legislature offers an institutional solution to temporary regime threats, enabling the leader to co-opt opponents and diminish their destructive potential. On the other hand, more powerful legislatures are better able to constrain the ruler’s decision-making. If the opposition gains control of such a legislature, they can successfully leverage that institutional power to marginalize, and perhaps even remove, the leader. As a result, the leader has an incentive to maintain a legislature, albeit one with limited power.

Absent other formal institutions, the strength of the legislature is an important indicator of the power asymmetry that characterizes the relationship between the leader and critical actors. This is especially so for the past, in which party cohesion and interparty competition were historically low. Understanding the relationship between executive and legislative power – what legislatures can do and the ways in which it is reinforced or undermined – is thus valuable for explaining differences in regimes and political outcomes, particularly where other institutions are not fully developed. For this reason, we exploit the variation in the powers attributed to legislatures to characterize their strength across regimes, with the aim of supporting research that could explain this variation.

As Judge pointed out, “other than in agreeing that institutionalization is a process whereby legislatures develop discrete modes of internal organization which help to differentiate them from their political environment, there is little agreement as to exactly what its defining core characteristics are.”Footnote9 While institutionalization has been conceptualized in a number of ways – including increasing adaptability, complexity, autonomy and coherenceFootnote10 – our use of the term refers to the process by which legislatures acquire value as a result of taking on additional roles and responsibilities and becoming more autonomous. To that end, we are primarily interested in using information on legislative capabilities and autonomy to indicate greater institutional capacity and complexity through expanded functions. We argue that changes in the powers of the legislature, both nominal and observed, provide an informative gauge of parliamentary strength vis-à-vis the executive.

Prior work

The nature of executive-legislative relationships represents a major agenda in the study of comparative politics, but only a few studies have attempted to develop comparable measures of legislative strength. Though scholars lamented as late as 2012 that “[c]omparative legislative studies are often comparative in name only”Footnote11, there are several notable exceptions. Fish and Kroenig used a large number of expert surveys in tandem with other data collection efforts to identify 32 attributes of national legislatures in 2007.Footnote12 The binary indicators that they used to construct the Parliamentary Powers Index (PPI) were based on questions that concerned four concept areas: influence over the executive, institutional autonomy, specified powers, and institutional capacity. Their approach to measuring the strength of national legislatures was unprecedented and for the first time opened up the possibility of comparing parliaments across countries based on multiple powers. The information that the project yielded was only available for 2007, however, limiting the range over which national legislatures could be compared and forestalling its use to study change over time.

An alternative project that also collected cross-national data on legislative abilities is the Institutions and Elections Project (IAEP), which documented codified rules regarding formal political institutions for countries between 1960 and 2012.Footnote13 Like Fish and Kroenig, IAEP denoted qualities such as whether legislatures had the power to amend the constitution, executive veto power and the power to dissolve the legislature, and requirements of congressional approval for war and international treaties. A major distinction between the two is that IAEP focused exclusively on de jure rules, meaning whether powers were stipulated by law, whereas Fish and Kroenig also compared experts’ subjective assessments regarding specific powers.Footnote14 The trade-off involved combining legal mandates with hypothetical outcomes – if the executive engaged in unconstitutional action, could the legislature prevent it? – as opposed to interpreting legislative strength based on documents that may or may not reflect reality.

Improvements on the efforts of the aforementioned projects occurred with the creation of the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, on which contributors from both of the previous projects collaborated. Based on a similar approach to that used by Fish and Kroenig, V-Dem amassed survey responses from over 3000 country experts to produce a large number of disaggregated estimates of components of democracy for nearly every country in the world between 1900 and 2017.Footnote15 Constructing the dataset involved administering questions to country experts regarding specific rules and practices and using Bayesian item response modelling to derive reliable estimates, which are provided on both continuous and ordinal/dichotomous scales. The dataset includes detailed information on attributes regarding elections, parties, the executive, the legislature and judiciary, and civil society, as well as indicators of their strength and autonomy.

Research design

Building on the foundational data collection efforts of Fish and Kroenig and IAEP – in combination with insightful critiques offered by scholars such as Desposato and Chernykh et al. and the extensions provided by the V-Dem ProjectFootnote16 – , we utilized information on de facto and de jure powers attributed to the legislature to gauge its strength relative to the executive. Our focus on both legally mandated and expected powers stems from the recognition that not all constitutions are explicit in the enumeration of legislative powers and that the limits of the parliament can grow to exceed that conferred upon them on parchment. Expanding to include information on expected powers enables us to better differentiate among less democratic regimes, in which constitutional provisions do not necessarily reflect the balance of power between the executive and the legislature. At the same time, however, the stipulation of legislative powers on paper can still send a valuable signal in the evolving balance of power between a leader and her opponents.Footnote17

The V-Dem data denote several critical functions of the legislature through a series of questions that pertain to constitutionally mandated powers as well as their expected enforcement capacity, all of which were determined by expert coders. The exact wording of the questions that we considered for inclusion are provided from the codebook in Online Appendix A. For transparency, and to facilitate replication, we also provided a table in Online Appendix B (Table B-1) that shows how the powers that we selected correspond to those included in the PPI.Footnote18 The first set of powers concerns legally codified consultative powers. We noted whether the legislature is able to unilaterally amend the constitution and grant pardons, and whether legislative approval is legally required to ratify foreign treaties or declare war. We also included whether the legislature has the ability to introduce bills in all policy areas and if its approval is required to pass legislation.

In addition to powers granted by law, we also considered questions related to the enforcement power of the legislature. These include whether the legislature regularly questions members of the executive branch and the likelihood that the legislature could conduct an independent investigation of the executive. To dichotomize the question of whether the legislature could investigate the executive, we coded a one if it were likely or nearly certain that the legislature would conduct an investigation against the executive if they were involved in unconstitutional activity, and zero otherwise. We also noted whether the legislature controls the necessary resources to finance internal operations in practice.

As additional indicators of the strength of the legislature relative to the executive, we included several questions that assessed the leader’s relation to parliament. First, we noted whether the head of state was appointed or approved by the legislature. We also noted whether the legislature would likely succeed if it took steps to remove the head of state from office. Roughly 60% of observations in which the IAEP coded the legislature as having the legal power to dismiss the executive were considered likely to succeed in practice. We added to this whether the head of state would not be likely to succeed in either dissolving the legislature or vetoing legislation, and whether they did not have the power to propose legislation. Compared to measures from the IAEP, about 86% of observations in which the executive had the legal power to dissolve the legislature were coded by experts as likely to succeed. Likewise, around 85 and 83% of the observations in which IAEP coded the executive as having the legal power to propose and veto legislation were observed or considered likely to succeed in practice based on V-Dem measures.

In total, the 16 indicators that we identified to gauge the ability of the executive to interfere with legislative activity and its power to create law and check the executive – six “by law” and ten “by practice” – correspond to 12 of those used to construct the PPI. This includes three variables relating to influence over the executive, four features of institutional autonomy, and five specified powers. Nine of these are in the top half of variables that were considered more important features by experts surveyed by Chernykh et al.Footnote19 Of the 32 variables that composed the Parliamentary Powers Index, 12 were either not explicitly coded by V-Dem or were not easily identifiable. We also included five variables that were not directly part of the PPI – whether the legislature legislates in practice or by law; whether the legislature appoints the head of state; if the head of state can propose legislation; and if opposition parties exert oversight and investigative power. For opposition oversight, we only coded it as one if experts’ responses to whether opposition parties exercise oversight and investigatory functions were “Yes, for the most part.” We converted all of the indicators to binary variables out of a foremost concern with whether a particular power was likely to hold or existed rather than qualifications of how likely it was to occur.

There are a number of features that are vital for the functioning of the legislature that we did not account for. Nevertheless, information on those characteristics is available in the V-Dem dataset and ought to be considered in analyses that employ estimates of legislative strength. This includes eight of the variables that were originally part of the PPI. First, we purposefully omitted the relationship between the legislature and the cabinet; we did not count whether legislators could serve as ministers in the government, nor whether their approval was required to appoint (or dismiss) ministers. This decision was guided in part by a desire to minimize the impact of constitutional design; in 98% of parliamentary democracies, for example, the head of state either cannot appoint cabinet ministers or does so only with legislative approval, compared to 16% of presidential democracies.

In focusing on the relationship between the legislature and the head of state, we also excluded indicators of its relationship to other actors. We did not include variables denoting the legislature’s power relative to the head of government – often appointed by the head of state, who is nominally more powerful – , nor whether the laws passed by the legislature were subject to judicial review. Likewise, we did not indicate whether alternative bodies, such as a comptroller general, had the capacity to question and investigate the executive. Excluding questions about outside actors is crucial for making comparisons across nondemocratic regimes, in which the lack of other autonomous institutions could be confounded with legislative strength. This is also true regarding elections, which do not always occur with the same regularity in nondemocracies. Other factors may influence legislative capacity but are further removed and less certain in nondemocracies, such as party discipline and legislative cohesion, as well as methods of popular participation that can supplant legislative decision-making (initiatives, plebiscites, and referendums). We do not consider the exclusion of such information a “sin of omission”, but instead as driven by a focus on comparing one institution across different contexts.Footnote20

Our use of specific indicators to denote legislative strength across regimes takes heed of criticisms that scholars have raised regarding the PPI. We tried to be judicious in the attributes that we selected to examine, thereby avoiding an overly inclusive approach that mixes information that may only be marginally relevant.Footnote21 Using the V-Dem data also helps to alleviate scholars’ concern with respondent uncertainty, insofar as the dataset provides upper and lower bounds on the point estimates calculated based on intercoder disagreement and measurement error.Footnote22 Though we focus on the primary estimates, we illustrate bounds for high and low estimates in subsequent tables and figures. Scholars have also pointed out the potential weakness of treating legislative powers as being equally important.Footnote23 This concern is most relevant when scholars employ an aggregate index based on powers in empirical analyses. To this end, Chernykh et al. used a large-scale survey of political scientists to re-weight the powers that made up the PPI.Footnote24 For our purposes, comparing the number of powers is intended only to summarize how many of the aforementioned attributes corresponded across intervals of time and democracy level. Notwithstanding, the valuable exercise undertaken by Chernykh et al. offers guidance for scholars who want to use the questions in the V-Dem data to construct a similarly weighted index.

Table B-2 provides summary statistics for each of the 16 powers on which we focused. Figure B-1 also illustrates trends in the proportion of each power by year, highlighting the least common power (opposition oversight) and most common power (legislates in practice) in 1900. Despite variation in the amount of missing observations, all of the variables cover 181 countries between 1900 and 2017. The recently added Historical V-Dem data extended many indicators as far back as 1789, but the dataset is substantially more complete for the period after 1900. For years before 1900, an average of 24 countries were covered, while roughly 101 countries are represented annually in the post-1900 data. All of the information that we report thus refers to the period 1900–2017.

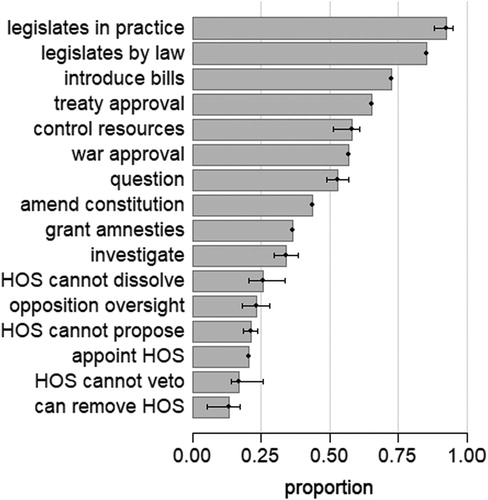

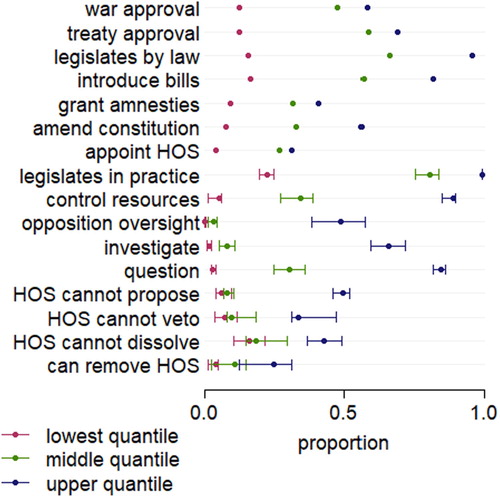

provides summary information by showing the frequency of each legislative power in our sample. The mean and median number of observations for which we have information on each legislative power is 14,788 and 13,415, respectively. The most commonly observed powers are legislation by the parliament in practice and by law, followed by the ability to introduce bills and approve treaties. The cumulative number of powers is fairly normally distributed, with a mean of 7.6 and median value of 8 powers (Figure B-2). Thus, the sample is not clearly differentiable into more and less democratic regimes, resembling a bimodal distribution. The overall number of powers based on low and high estimates are also normally distributed, with respective means of 7.4 and 7.8 and a mode of 8.

In the following section, we examine legislative powers across all regimes. First, we look at country examples and regional differences in the proportion of powers that have been observed. We then focus on the relationship between types of powers and the overall number of powers, highlighting potential contingencies. We also look at how legislative powers vary across the level of democracy and elucidate on the manner in which they change over time. Such a comparison promises to add flesh to models of legislative dynamics by describing both the extent to which legislatures differ and the speed with which they change.

Results

Regional comparisons and examples

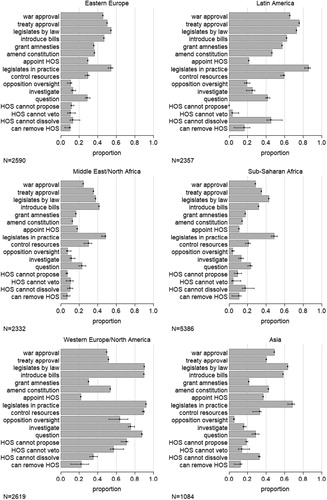

illustrates how regions differ with regard to the proportion of observations in which each type of power has occurred since 1900. Notably, there is no region that outperforms others on every question. As expected, countries in Western Europe and North America exhibit substantially more equipped parliaments in terms of de jure powers and an anticipated ability to monitor and sanction the executive, especially with regard to the powers to introduce bills, control internal resources, and question the executive. In contrast, a greater proportion of legislatures in Latin America have required legislative approval for war and treaties and have been able to grant amnesties. Although the region lags behind “Western” powers in terms of the legislature’s ability to control resources and exert oversight functions – including investigating and questioning the executive – it surpasses other world regions on these dimensions. Countries in Eastern Europe are comparatively weaker relative to Latin America, particularly with regard to monitoring and enforcing the actions of the executive. The distribution of observations in the Middle East and North Africa most closely resembles that of Sub-Saharan Africa – not simply in the relative weakness of the legislature, but also in the frequencies of each power. In South and East Asia, more legislatures are able to introduce bills and amend the constitution compared to other developing regions, despite having relatively little opposition oversight.

The distribution of legislative powers across regions is consistent with regime patterns and corroborate what existing scholarship has noted. Western Europe and North America show the most equipped legislatures, which have a longer history of parliamentary rule. They are followed by Latin America, which is characterized by presidential democracy but has been subject to strong executives and repeated military intervention. Eastern Europe and many countries in Asia, in contrast, have had legislatures that tended to be dominated by one-party rule. Likewise, legislatures in Sub-Saharan Africa have been undermined by personalist regimes, while the Middle East has seen a mix of “strongman” regimes like that of Saddam Hussein alongside durable monarchies found in Saudi Arabia and the Emirates. These differences are reflected in the prevalence of powers that are observable in each region.

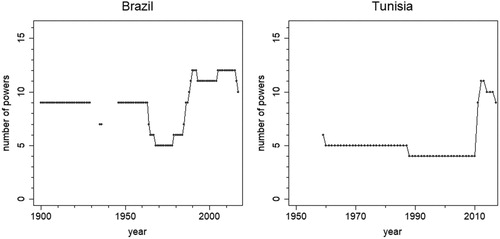

In addition to depicting cross-regional differences, the data on legislative powers show temporal variation within countries that testify to their face validity. shows two cases that were chosen because they exemplify extreme variations associated with nondemocratic rule and democratization, both within and across regimes. Brazil illustrates two ways in which military rule undermined legislative strength. Following a defeat in the 1930 presidential elections, Governor of Rio Grande do Sul Getúlio Vargas participated in an insurrection supported by the military. The coup that placed him in office launched roughly 15 years of dictatorship, during most of which the legislature was abolished. After overthrowing Vargas in 1945, the armed forces once again intervened in politics by replacing João Goulart in 1964. The military remained in power for the next two decades; instead of abolishing the legislature, however, it increasingly restricted its power through a series of decrees known as the Institutional Acts. Upon returning to the barracks in 1985, a new constitution was promulgated in 1988 and the first legislative elections were held in 1990, inaugurating a legislature with greater powers relative to the executive.

As one of the few successes – indeed, the origin – of the “Arab Spring” that began in late 2010, Tunisia is also an exemplary case. Following independence in 1956, the first legislative elections held after the new constitution occurred in 1959. As was true for the Constituent Assembly, the party of President Habib Bourguiba won all of the seats. Bourguiba remained head of state for over 30 years and was only replaced after being declared mentally unfit and removed from office by Prime Minister Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali. In turn, Ben Ali continued in office as president for roughly 24 years, continuously being elected with large majorities until the large-scale uprising that unseated him in 2011. Unlike other MENA countries that were subject to widespread protests at the time, the political regime change that occurred resulted in democratization and corresponded with the emergence of a substantially stronger legislature in terms of the powers that we identified.

Legislative powers and level of democracy

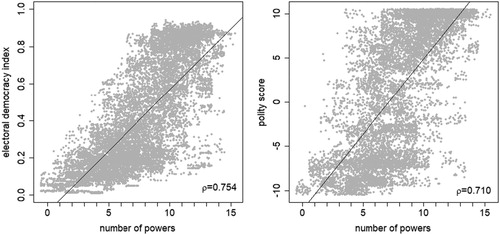

Insofar as legislative strength is considered a key institutional feature of democratization,Footnote25 important questions are whether more democratic countries correspond with more empowered legislatures and how powers attributed to the legislature vary across levels of democracy. shows the relationship between the number of powers a legislature possesses and V-Dem’s measure of electoral democracy (v2x_polyarchy). None of the legislative powers feature directly in the construction of the electoral democracy index (EDI) – and different coders responded to specific sets of questions in the data – , thereby allowing us to compare the relationship between legislative strength and other aspects of democracy. As the figure shows, there is a fairly strong positive correlation between the level of electoral democracy and the strength of the legislature. Indeed, no legislature possesses fewer than five of the 16 powers in regimes with a democracy score above 0.6. At the same time, the greatest amount of variation in the number of legislative powers occurs below the median and mean value of democracy (0.321 and 0.413, respectively), which spans nearly the entire index. The apparent relationship between democracy and legislative strength is not restricted to the EDI. The number of powers shows a similar correlation with the polity score from the Polity IV project, which measures regime authority characteristics on a scale from −10 to 10, with 10 being the most democratic.Footnote26

The findings also appear robust when we move from continuous to categorical regime type measures. Here, scholars have used a number of different approaches to distinguish democracies from less democratic regimes. These include assigning regimes to discrete categories based on qualitative differences,Footnote27 using a “minimal definition” of democracy based on electoral practices,Footnote28 and creating cut-off values for indices of democracy.Footnote29 For the purpose at hand, none of these approaches allow us differentiate across regimes without imposing specific assumptions about the power arrangement between the executive and legislature. As an initial approach, therefore, we split the sample of observations into evenly divided quantiles and compare legislative powers across them. In so doing, we are able to compare more democratic with less democratic regimes while leaving the characteristics of their respective legislature unspecified.

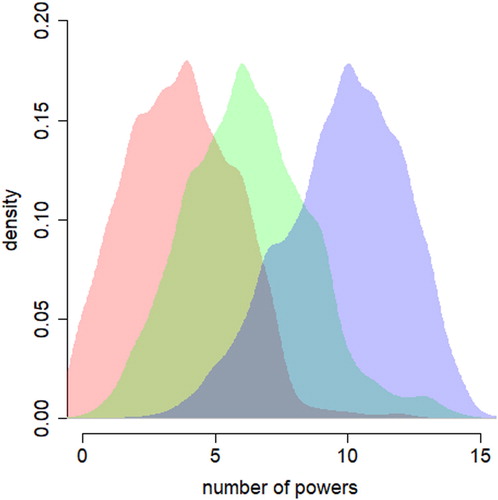

When we divide the sample between two and five quantiles based on the electoral democracy index and plot the distribution of legislative powers for each, three quantiles appear to be the most distinct (shown in ).Footnote30 Going from two to three quantiles produces a “middle” category situated fairly evenly between the countries with more institutionalized and less institutionalized legislatures. In contrast, specifying four quantiles results in a distribution that overlaps considerably with the third (refer to Figure B-3). The way in which observations are distributed based on the number of legislative powers supports the idea that regimes can be characterized as belonging to one of three “types”: democracies with institutionalized legislatures, nondemocracies with no or noninstitutionalized legislatures, and mid-range regimes with weakly to moderately institutionalized legislatures. The average number of legislative powers associated with each of the three quantiles is 3.7, 6.3, and 9.9, respectively, increasing by roughly three as we move from the lowest to the highest quantile. The distribution is strikingly similar when we evaluate the number of powers across three quantiles based on the polity score (Figure B-4), which average 5.4, 7.7, and 10.7.

Figure 5. Distribution of count of legislative powers (Showing three quantiles of the electoral democracy index).

Our approach to creating subsets based on relative democraticness comports well with existing categorical measures of democracy. Cheibub et al., for example, take a strictly minimalist approach wherein democracies satisfy the following requirements – they hold elections in which the outcome is uncertain, executive turnover follows a similar procedure, and elections are regularly held.Footnote31 Based on their coding scheme, we observe the average number of legislative powers to be 10.2 in democracies (Figure B-5). There is thus only a 0.3-point difference between the legislative powers found in our highest democracy quantile – democracies with institutionalized legislatures – and those defined by Cheibub et al. The same 0.3-point difference in legislative powers persists when switching to the measure by Boix et al.Footnote32, who designate as democracies those in which the executive and legislature are freely elected and a majority of adult men has the right to vote. Notably, the types of democracy identified by Cheibub et al.Footnote33 – parliamentary versus presidential regimes – do not differ much by the number of powers, averaging 10.6 and 9.4 respectively (Figure B-6).Footnote34

In comparison to their democratic counterparts, scholars argue that legislatures in authoritarian settings serve qualitatively different purposes. Rather than acting as a conduit for channelling citizen preferences through representatives, in authoritarian regimes the legislature is a forum that regulates the contention between the leader and ruling elites. In what Svolik termed established dictatorships, the leader is powerful enough that challenges to their rule are non-threatening.Footnote35 Here, if the legislature is present at all, it largely serves as a signalling mechanism – one where the leader offers minimal powers to elites for their cooperation. By contrast, in contested dictatorships the ruling elite is sufficiently strong to hold the leader in check and thereby maintain a more even power-sharing arrangement, which is often evident in its institutions. This is illustrated by the distribution of powers among party-based autocracies coded by Geddes et al.Footnote36 Such regimes possess an average of 6.6 legislative powers, a difference of only 0.3 from the middle quantile (Figure B-7). This supports the notion that regimes in this group are closer to contested dictatorships, which exhibit institutions that are somewhat capable of constraining the dictator.

We also find support for differentiating between contested and established autocracies when focusing on the content of the legislative powers across the three quantiles. depicts differences in the types of legislative powers that are observable across the three quantiles by illustrating the proportion of observations with each of the powers. The figure also provides upper and lower bounds associated with the estimates. As the figure shows, legislatures in the lowest third of countries based on electoral democracy are considerably weaker. Among them, the most common attributes include the head of state being unlikely to succeed in dissolving them, legislating in practice, and the ability to introduce bills. This reflects the fledgling nature of legislatures in the least democratic countries – they assume the basic functions of legislating but have little real power and few constitutional protections.

Among countries with middle-range values of electoral democracy, the most substantial increases occur in de facto legislation and the legal power to legislate and introduce bills, followed by the power to approve war and treaties. At the highest quantile of the electoral democracy index, control over funds and the power to investigate the executive become most prominent, followed by greater questioning and oversight capacity. Legislative strengthening across regimes is actually more pronounced for quantiles based on the polity index (Figure B-8), in which countries in the lowest quantile go from legislating in practice and by law and introducing bills to questioning the executive and controlling resources in the middle quantile. The highest quantile of democracy shows a greater propensity to investigate the executive and to exert opposition oversight. The differences in proportions, then, demonstrate that legislatures in more democratic regimes show greater legislative activity and the ability to hold the executive accountable. In the context of nondemocratic regimes, it suggests that contested dictatorships (i.e. quantile 2) contain more institutionalized legislatures than their established counterparts (i.e. quantile 1). This is consistent with categorizations of regimes based on the EDI, which code all countries in the lowest two quantiles as nondemocracies.Footnote37

Temporal features of changes in legislative powers

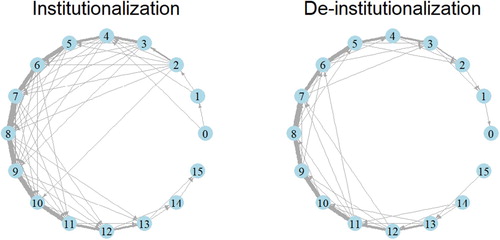

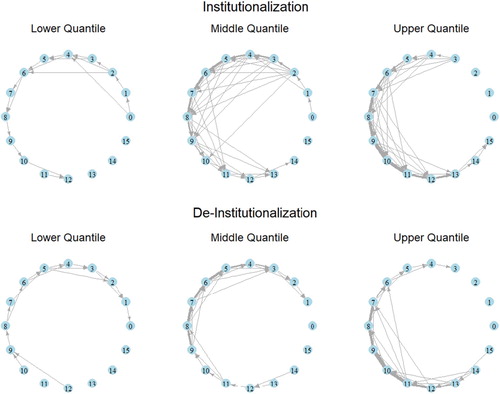

Given our findings on the relationship between “democraticness”, legislative institutionalization, and the types of powers with which they are endowed, it is also important to consider the rate at which legislatures become further equipped or disempowered. Inasmuch as a count of the powers ascribed to the legislature provides a measure of strength, what is the actual process by which it changes? Moreover, does the rate of change differ when legislatures accrue power as opposed when they lose it? represents the acquisition (left panel) and loss (right panel) of powers in form of a network, illustrating how much change there is likely to be in powers from one year to the next.

The nodes in represent the number of powers a legislature possessed at a given year, and the ties indicate transitions that occurred from one node to another in the sample. The thicker the link between any two nodes, the more frequently that transition occurred. A link between the nodes one and ten, for example, represents a legislature that underwent drastic changes, one in which they transitioned from possessing just one power in a given year to possessing ten of the powers in the subsequent year. This example is not reflected in the results, however; not a single instance occurred in which a legislature made a leap from one to ten powers, or vice-versa. Instead, the figure shows a strong tendency towards incremental change. Out of a total of 1230 cross-node transition instances, over 80% (987) involved a neighbouring node. Given the legislature’s current powers, if it changed it tended to acquire or lose just one power. This is particularly true for legislatures that became weaker – roughly 86% of downward movements involved a one-power change, compared to 76% of upward transitions. Moreover, larger changes are apparent in institutionalizing legislatures – such as jumps from 2 to 10, or from 3 to 9 powers – which do not occur among those that were de-institutionalizing. This supports the implication that legislatures strengthen faster than they become weaker.

To evaluate the way in which dynamics differ across regimes, we constructed similar networks representing institutionalization and de-institutionalization based on a dichotomous measure of democracy as well as across quantiles of the electoral democracy index. Figure B-9 shows the breakdown of upwards and downwards changes in the number of legislative powers for democracies and nondemocracies coded by Boix et al.,Footnote38 for which there were more observations. De-institutionalization in democracies appears more iterative than in nondemocracies. Another interesting finding is that changes spanning multiple powers tend to centre around the average number of legislative powers in both types of regimes.

Legislative institutionalization – in the form of increases in the number of powers – is also illustrated for each of the three quantiles in . Fewer transitions occurred in the lowest quantile of electoral democracy, but a greater proportion of increases occurred over one value (0.895). Nearly the same proportion of increases in the upper-two quantiles involved single-value increases (0.836 and 0.841). Mid-range regimes thus exhibit greater activity in terms of legislative institutionalization, as well as a tendency towards larger increases, compared to the least democratic regimes. This emphasizes the importance of considering the role of legislative institutionalization in contested authoritarian regimes, where it tends to be in greater flux.

Discussion

The prevalence of legislatures across regimes, in combination with the established work on political institutions in nondemocracies, implies that they can be more than window dressings. The clout that the legislature wields as an institution is also not static, accentuating the need to better understand how powerful they are and in what ways they are empowered. Moreover, the types of powers secured by the legislature may be meaningful, even if on paper.Footnote39 The content of powers with which legislatures are imbued is not well known, however, making it difficult to describe exactly how executive-legislative relations affect regime dynamics, especially in nondemocratic regimes. This underscores the first contribution of this article, which is to illustrate and describe the powers of legislatures across regimes. To yield insights into the content of legislatures, we examined differences in 16 specific powers coded by the Varieties of Democracy Project.Footnote40

Leveraging expert assessments of constitutionally inscribed and inferred powers attributed to legislatures, we evaluated their frequencies across regimes. In doing so, we found considerable variation in the types of powers that we observed and illuminated several findings. The differences between regions in the average level of legislative institutionalization and the proportion of specific powers is clear – Western Europe and North America have substantially stronger legislatures, but the strength of parliaments in Latin America also stands apart from other world regions. There is also a fairly strong correlation between the overall number of legislative powers and the level of democracy. In particular, there is noticeable differentiation between regimes based on the number of legislative powers and the level of electoral democracy, which coalesce into groups that resemble consolidated authoritarianism, institutionalized authoritarian regimes, and democracies. We find similar patterns across alternative indices of democracy level as well as extant regime typologies, suggesting a dimension on which many different measures correspond.Footnote41 It is thus remarkable that none of the previous efforts to typify nondemocracies based on institutions have included legislatures as a distinguishing feature.Footnote42

Across quantiles of electoral democracy, the tenuous relationship between the legislature and the executive first becomes formalized, followed by the addition of enforcement powers and then oversight and investigative powers. Given that the types of powers that we observed differs by the overall number of powers and the aggregate count of legislative powers corresponds to the electoral democracy index, it follows that there are differences in the types of powers that exist across democracy level. Comparing changes in legislative powers across time also shows that such change is often incremental. Rather than occurring all at once, the accumulation of more powers tends to be piecemeal, reflecting the notion of bargaining between the executive and parliamentarians as well as institutional continuity. The extent of changes in legislative powers among mid-range regimes, towards both institutionalization and de-institutionalization, also testifies to the need to pay greater attention to legislative powers in democratizing and “contested” authoritarian regimes.Footnote43

Our approach to indicating institutionalization combined information on both legal and implied capabilities and treated the set of powers that we examined as being equally relevant, which is a valid concern for analyses that utilize indices of legislative power.Footnote44 The combination of critical approaches to index construction and estimates of uncertainty provided by the V-Dem data can help to improve empirical research on legislative institutionalization. Our approach encourages advancements in the study of legislative institutionalization by overviewing the available data and demonstrating its applicability in less democratic regimes. This represents the second major contribution of this article, which is to point to the possibility of using legislative powers to vastly expand the scope of research on executive-legislative relations in institutionalized autocracies, which use legislatures to constrain opposition and mitigate threats to the regime. This could involve modelling legislative institutionalization as a function of opposition gains and regime dynamics and using it to predict outcomes such as regime survival and conflict. Additional questions include the extent to which powers act as substitutes for other concessions, and their specific impacts on features such as accountability and corruption. By utilizing data on specific powers, comparative legislative scholars are in a better position to expound on differences across regimes and to explain their effects on subsequent developments.

Conclusion

Although scholars have argued that legislatures may serve functional roles in nondemocracies, there is little work that considers the types of power that authoritarian legislatures have. While the literature on authoritarian institutions contains explanations for the dynamics that seemingly give rise to new rules and practices, they are not substantiated by analyses that relate the type or number of powers wielded by the congress to their ability to check the executive and exert constraints. This article elucidates on legislative strength across regimes by looking at differences in the types and number of powers associated with them. Based on data from the Varieties of Democracy Project for 181 countries between 1900 and 2017, we used dichotomous information on 16 different powers to depict the ways in which regimes differ in terms of the types and number of legislative powers.

Our comparative overview highlights several noteworthy findings. First, we observe regional differences in the frequencies of specific legislative attributes, as well as temporal changes that appear to be face-valid descriptors of well-known cases. Different “types” of regimes are also distinguishable by the overall number of powers, across which the types of powers differ, and there is some evidence of order in the accumulation of powers attributed to the legislature. We demonstrated that the cumulative number of legislative powers that we examined is strongly correlated with the level of electoral democracy and that the type of powers varies by both the overall number of powers and the level of democracy. In particular, splitting the sample into equal groups based on the level of electoral democracy shows that the least democratic regimes tend to be associated with legislatures that have only “consultative powers”, referring to the ability to approve treaties and war and to amend the constitution. Though they are unlikely to meet the minimal criteria to be considered democratic, a greater proportion of countries in the middle range of democraticness have legislatures that have increasing power to select and question the executive and to administer the funding of internal operations. Only in the most democratic group of countries are investigation and oversight powers observable among legislatures.

Analysing changes in legislative powers across time also revealed that such changes are slow and incremental, which supports models that portray legislatures as products of a bargaining process between the executive and coalition members. We argued that patterns of legislative institutionalization support theoretical accounts of such processes producing established and contested dictatorships, which is reflected in both the type and number of powers that we observed. Our descriptive analyses constitute a necessary part of the process of expanding the frontier of research objectives.Footnote45 By thinking more about the content as well as the structure that leaders use to form a support coalition and respond to outsiders, institutional scholarship can develop more precise explanations for the mechanisms that affect regime change and persistence.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Mona Morgan-Collins and the School of Government and International Affairs at Durham University for their help developing the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Matthew Charles Wilson

Matthew Charles Wilson is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of South Carolina. He received his PhD from Pennsylvania State University. His research focuses on the interactions of autocratic leaders and institutions, particularly with regard to regime change and conflict outcomes.

Josef Woldense

Josef Woldense is an Assistant Professor in the Department of African American & African Studies and is an Affiliated Faculty in Political Science at the University of Minnesota. He received his PhD from Indiana University in Political Science. His research interests are in the areas of elite politics, authoritarian regimes, political institutions and social network analysis, with a geographical focus on Africa.

Notes

1. Coppedge et al., V-Dem Codebook v8.

2. Gerring, “Mere Description.”

3. Chernykh, Doyle, and Power, “Measuring Legislative Power”; Fish and Kroenig, Handbook of National Legislatures.

4. Coppedge et al., V-Dem Codebook v8; Pemstein et al., “V-dem Measurement Model.”

5. Boix and Svolik, “Foundations of Limited Authoritarian”; Gandhi, Political Institutions; Gandhi and Przeworski, “Cooperation, Cooptation and Rebellion”; Gandhi and Przeworski, “Authoritarian Institutions”; Jensen, Malesky, and Weymouth, “Unbundling the Relationship”; Truex, “Returns to Office”; Wright, “Do Authoritarian Institutions Constrain?”

6. Fjelde, “Generals, Dictators and Kings”; Fjelde and de Soysa, “Coercion, Co-optation, or Cooperation”; Weeks, “Autocratic Audience Costs”; Wright, “Do Authoritarian Institutions Constrain”; Wright and Escribá-Folch, “Authoritarian Institutions.”

7. Svolik, Politics of Authoritarian Rule, 13.

8. Tamkin, “Venezuela’s Supreme Court.”

9. Judge, “Legislative Institutionalization,” 499.

10. Huntington, Political Order.

11. Desposato, “Book Review,” 389.

12. Fish and Kroenig, Handbook of National Legislatures.

13. Wig, Hegre, and Regan, “Updated Data.”

14. Fish and Kroenig, Handbook of National Legislatures.

15. Coppedge et al., V-Dem Codebook v8; Pemstein et al., “V-dem Measurement Model.”

16. Chernykh, Doyle, and Power, “Measuring Legislative Power”; Desposato, “Book Review.”

17. Albertus and Menaldo, “Dictators as Founding Fathers.”

18. All items prefixed with “B” (e.g. Table B-1) are provided in Online Appendix B.

19. Chernykh, Doyle, and Power, “Measuring Legislative Power.”

20. Desposato, “Book Review”; Fish and Kroenig, Handbook of National Legislatures.

21. Chernykh, Doyle, and Power, “Measuring Legislative Power”; Desposato, “Book Review.”

22. Coppedge et al., V-Dem Codebook v8; Desposato, “Book Review.”

23. Chernykh, Doyle, and Power, “Measuring Legislative Power”; Desposato, “Book Review.”

24. Chernykh, Doyle, and Power, “Measuring Legislative Power.”

25. Dryzek, “Democratization as Deliberative”; Fish, “Stronger Legislatures.”

26. Marshall, Gurr, and Jaggers, “Polity IV Project.”

27. Collier and Levitsky, “Democracy with Adjectives”; Diamond, “Thinking about Hybrid Regimes.”

28. Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland, “Democracy and Dictatorship”; Przeworski et al., Democracy and Development.

29. Epstein et al., “Democratic Transitions”; Hegre et al., “Toward a Democratic Civil Peace.”

30. The values that separate the EDI into three evenly divided quantiles are 0.117 and 0.339.

31. Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland, “Democracy and Dictatorship.”

32. Boix, Miller, and Rosato, “A Complete Data Set.”

33. Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland, “Democracy and Dictatorship.”

34. The biggest differences between parliamentary and presidential regimes concern limits on executive power; a substantially higher proportion of heads of state cannot veto or propose legislation in parliamentary democracies, and the heads of state in presidential democracies tend to face greater challenges dissolving the legislature.

35. Svolik, “Power Sharing.”

36. Geddes, Wright, and Frantz, “Autocratic Breakdown.”

37. Lührmann, Tannenberg, and Lindberg, “Regimes of the World.”

38. Boix, Miller, and Rosato, “A Complete Data Set.”

39. Albertus and Menaldo, “Dictators as Founding Fathers.”

40. Coppedge et al., V-Dem Codebook v8; Pemstein et al., “V-dem Measurement Model.”

41. Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland, “Democracy and Dictatorship”; Geddes, Wright, and Frantz, “Autocratic Breakdown.”

42. Wilson, “A Discreet Critique.”

43. Svolik, “Power Sharing.”

44. Chernykh, Doyle, and Power, “Measuring Legislative Power”; Desposato, “Book Review.”

45. Gerring, “Mere Description.”

References

- Albertus, Michael, and Victor Menaldo. “Dictators as Founding Fathers? The Role of Constitutions Under Autocracy.” Economics & Politics 24, no. 3 (2012): 279–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0343.2012.00402.x

- Boix, Carles, and Milan W. Svolik. “The Foundations of Limited Authoritarian Government: Institutions, Commitment and Power-sharing in Dictatorships.” The Journal of Politics 75, no. 2 (2013): 300–316. doi: 10.1017/S0022381613000029

- Boix, Carles, Michael K. Miller, and Sebastian Rosato. “A Complete Data Set of Political Regimes, 1800–2007.” Comparative Political Studies 46, no. 12 (2013): 1523–1554. doi: 10.1177/0010414012463905

- Cheibub, José A., Jennifer Gandhi, and James R. Vreeland. “Democracy and Dictatorship Revisited.” Public Choice 143 (2010): 67–101. doi: 10.1007/s11127-009-9491-2

- Chernykh, Svitlana, David Doyle, and Timothy J. Power. “Measuring Legislative Power: An Expert Reweighting of the Fish-Kroenig Parliamentary Powers Index.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 42, no. 2 (2017): 295–320. doi: 10.1111/lsq.12154

- Collier, David, and Steven Levitsky. “Democracy with Adjectives: Conceptual Innovation in Comparative Research.” World Politics 49, no. 3 (1997): 430–451. doi: 10.1353/wp.1997.0009

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jan Teorell, David Altman, et al. V-Dem Codebook v8. Varieties of Democracy Project, 2018.

- Desposato, Scott. “Book Review: The Handbook of National Legislatures.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 37, no. 3 (2012): 389–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-9162.2012.00052.x

- Diamond, Larry J. “Thinking about Hybrid Regimes.” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 2 (2002): 21–35. doi: 10.1353/jod.2002.0025

- Dryzek, John S. “Democratization as Deliberative Capacity Building.” Comparative Political Studies 42, no. 11 (2009): 1379–1402. doi: 10.1177/0010414009332129

- Epstein, David L., Robert Bates, Jack Goldstone, Ida Kristensen, and Sharyn O’Halloran. “Democratic Transitions.” American Journal of Political Science 50, no. 3 (2006): 551–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00201.x

- Fish, M. Steven. “Stronger Legislatures, Stronger Democracies.” Journal of Democracy 17, no. 1 (2006): 5–20. doi: 10.1353/jod.2006.0008

- Fish, M. Steven, and Matthew Kroenig. The Handbook of National Legislatures: A Global Survey. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Fjelde, Hanne. “Generals, Dictators and Kings: Authoritarian Regimes and Civil Conflict, 1973–2004.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 27, no. 3 (2010): 195–218. doi: 10.1177/0738894210366507

- Fjelde, Hanne, and Indra de Soysa. “Coercion, Co-optation, or Cooperation?” Conflict Management and Peace Science 26, no. 1 (2009): 5–25. doi: 10.1177/0738894208097664

- Gandhi, Jennifer. Political Institutions Under Dictatorship. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski. “Authoritarian Institutions and the Survival of Autocrats.” Comparative Political Studies 40, no. 11 (2007): 1279–1301. doi: 10.1177/0010414007305817

- Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski. “Cooperation, Cooptation and Rebellion Under Dictatorships.” Economics & Politics 18, no. 1 (2006): 1–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0343.2006.00160.x

- Geddes, Barbara, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz. “Autocratic Breakdown and Regime Transitions: A New Data Set.” Perspectives on Politics 12, no. 2 (2014): 313–331. doi: 10.1017/S1537592714000851

- Gerring, John. “Mere Description.” British Journal of Political Science 42, no. 4 (2012): 721–746. doi: 10.1017/S0007123412000130

- Hegre, Håvard, Tanja Ellingsen, Scott Gates, and Nils Petter Gleditsch. “Toward a Democratic Civil Peace? Democracy, Political Change and Civil War, 1816–1992.” American Political Science Review 95, no. 1 (2001): 33–48.

- Huntington, Samuel P. Political Order in Changing Societies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1968.

- Jensen, Nathan M., Edmund Malesky, and Stephen Weymouth. “Unbundling the Relationship between Authoritarian Legislatures and Political Risk.” British Journal of Political Science 44, no. 3 (2014): 655–684. doi: 10.1017/S0007123412000774

- Judge, David. “Legislative Institutionalization: A Bent Analytical Arrow?” Government and Opposition 38, no. 4 (2003): 497–516. doi: 10.1111/1477-7053.t01-1-00026

- Lührmann, Anna, Marcus Tannenberg, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes.” Politics and Governance 6, no. 1 (2018). doi: 10.17645/pag.v6i1.1214

- Marshall, Monty G., Tedd R. Gurr, and Keith Jaggers. “Polity IV Project: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2016.” 2017. http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscr/p4manualv2016.pdf.

- Pemstein, Daniel, Kyle L. Marquardt, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting. Wang, Joshua Krusell, and Farhad Miri. “The V-dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-national and Cross-temporal Expert-coded Data.” Working Paper No. 21, University of Gothenburg, Varieties of Democracy Institute, 2018.

- Przeworski, Adam, Michael E. Alvarez, José A. Cheibub, and Fernando Limongi. Democracy and Development. Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Svolik, Milan W. “Power Sharing and Leadership Dynamics in Authoritarian Regimes.” American Journal of Political Science 53, no. 1 (2009): 477–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00382.x

- Svolik, Milan W. The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Tamkin, Emily. “Venezuela’s Supreme Court Shuts Down Country’s Congress.” Foreign Policy, March 30, 2017.

- Truex, Rory. “The Returns to Office in a ‘Rubber Stamp’ Parliament.” American Political Science Review 108, no. 2 (2014): 235–251. doi: 10.1017/S0003055414000112

- Weeks, Jessica L. “Autocratic Audience Costs: Regime Type and Signaling Resolve.” International Organization 62 (2008): 35–64. doi: 10.1017/S0020818308080028

- Wig, Tore, Håvard Hegre, and Patrick M. Regan. “Updated Data on Institutions and Elections 1960–2012: Presenting the Iaep Dataset Version 2.0: Research & Politics.” April–June, 2015, 1–11.

- Wilson, Matthew Charles. “A Discreet Critique of Discrete Regime Type Data.” Comparative Political Studies 47, no. 5 (2014): 689–714. doi: 10.1177/0010414013488546

- Wright, Joseph, and Abel Escribá-Folch. “Authoritarian Institutions and Regime Survival: Transitions to Democracy and Subsequent Autocracy.” British Journal of Political Science 42, no. 2 (2012): 283–309. doi: 10.1017/S0007123411000317

- Wright, Joseph. “Do Authoritarian Institutions Constrain? How Legislatures Affect Economic Growth and Investment.” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 2 (2008): 322–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00315.x