ABSTRACT

Less than 30 years after Fukuyama and others declared liberal democracy’s eternal dominance, a third wave of autocratization is manifest. Gradual declines of democratic regime attributes characterize contemporary autocratization. Yet, we lack the appropriate conceptual and empirical tools to diagnose and compare such elusive processes. Addressing that gap, this article provides the first comprehensive empirical overview of all autocratization episodes from 1900 to today based on data from the Varieties of Democracy Project (V-Dem). We demonstrate that a third wave of autocratization is indeed unfolding. It mainly affects democracies with gradual setbacks under a legal façade. While this is a cause for concern, the historical perspective presented in this article shows that panic is not warranted: the current declines are relatively mild and the global share of democratic countries remains close to its all-time high. As it was premature to announce the “end of history” in 1992, it is premature to proclaim the “end of democracy” now.

Introduction

The decline of democratic regime attributes – autocratization – has emerged as a conspicuous global challenge. Democratic setbacks in countries as diverse as Brazil, Burundi, Hungary, Russia, Serbia, and Turkey have sparked a new generation of studies on autocratization.Footnote1

Two key issues are not yet settled in this reinvigorated field. First, scholars agree that contemporary democracies tend to erode gradually and under legal disguise.Footnote2 Democratic breakdowns used to be rather sudden events – for instance military coups – and relatively easy to identify empirically.Footnote3 Now, multi-party regimes slowly become less meaningful in practiceFootnote4 making it increasingly difficult to pinpoint the end of democracy. Yet, in face of this emerging consensus we lack the appropriate conceptual and empirical tools to systematically analyse such obscure processes.

The second key issue, partly a product of the first, is that analysts disagree about how momentous the current wave of autocratization is. Some draw parallels to the breakdown of democracies in the 1930s and the rise of anti-democratic demagogues.Footnote5 Others maintain that the world is still more democratic,Footnote6 developedFootnote7 and emancipatedFootnote8 than ever during the twentieth century. How wide and deep does the current autocratization trend cut?

This article addresses these gaps with a three-pronged strategy. First, it provides a definition of autocratization as substantial de-facto decline of core institutional requirements for electoral democracy. This notion is more encompassing than the frequently used term democratic backsliding, which suggests an involuntary reversal back to historical precedents. Our notion of democracy is based on Dahl’s famous conceptualization of electoral democracy as “polyarchy”, namely clean elections, freedom of association, universal suffrage, an elected executive, as well as freedom of expression and alternative sources of information.Footnote9

Second, this article offers a new type of operationalization that in a systematic fashion captures the conceptual meaning of autocratization as episodes of substantial change based on data from the Varieties of Democracy Project (V-Dem). This new measure has four major advantages: It measures what we actually want to study; it is sensitive to changes in the de-facto implementation of democratic rules; and it is nuanced enough to also capture gradual autocratization processes and thus avoid biasing the sample towards fast-moving changes. Finally, it allows us to pinpoint the year of the onset of autocratization processes, which opens new avenues for empirical studies.

Third, this article employs the new measure in a systematic study that adds a historical perspective on contemporary autocratization. The resultant findings are mixed. On the one hand, we are the first to show that a “third wave of autocratization” affecting an unprecedented high number of democracies is under way. This wave unfolds slow and piecemeal making it hard to evidence. Ruling elites shy away from sudden, drastic moves to autocracy and instead mimic democratic institutions while gradually eroding their functions. This suggests we should heed the call of alarm issued by some scholars.

On the other hand, the evidence here also shows that we still live in a democratic era with more than half of all countries qualifying as democratic. In addition, most episodes of contemporary autocratization are not only slower, but also feebler than their historical cousins, at least as of yet. Thus, the affected countries remain more democratic than their equivalents hit by earlier waves of autocratization.

Below, we first pursue a review of the literature followed by a reconceptualization of autocratization with accompanying operationalization, description of data, and coding procedures. The following section presents a series of descriptive analyses of the three waves of autocratization, followed by a closer examination of the autocratization of democracies. The final section introduces a new metric – the rate of autocratization – as an indicator for the pace of such processes. We conclude with a summary of the findings and avenues for future research.

State of the art at present

Many have noted that the optimism spurred by the force of the third wave of democratizationFootnote10 was premature, including Fukuyama’sFootnote11 relegation of the reverse process – autocratization – to the history books. A plethora of autocracies defied the trendFootnote12 or made some half-hearted reforms while remaining in the grey zone between democracy and autocracy.Footnote13

Yet, when assessments about “freedom in retreat”Footnote14 or “democratic rollback”Footnote15 emerged, they were frequently challenged. At the time, global measures of democracy had merely plateaued and established democracies did not appear to be in distress.Footnote16 Now evidence is mounting that a global reversal is challenging a series of established democracies, including the United States who were downgraded by both Freedom House and V-Dem in 2018.Footnote17 Substantial autocratization has been recorded over the last 10 years in countries as diverse as Hungary, India, Russia, Turkey, and Venezuela.Footnote18 An increasingly bleak picture is emerging on the global state of democracy,Footnote19 even if some maintain that the achievements of the third wave of democratization are still noticeable.Footnote20

Waldner and Lust recently concluded that “[t]he study of [democratic] backsliding is an important new research frontier”. Footnote21 A series of new studies on autocratization seems to have generated an emerging consensus on one important insight: the process of autocratization seems to have changed. Bermeo for example suggests a decline of the “most blatant forms of backsliding” – such as military coups and election day vote fraud.Footnote22 Conversely, more clandestine ways of autocratization – harassment of the opposition, subversion of horizontal accountability – are on the rise.Footnote23 Svolik similarly argues that the risk of military coups has declined over time in new democracies, while the risk of self-coups remains.Footnote24 Mechkova et al. demonstrate that between 2006 and 2016 autocratization mainly maimed aspects such as media freedom and the space for civil society leaving the institutions of multiparty elections in place.Footnote25 Coppedge singled out the gradual concentration of power in the executive as a key contemporary pattern of autocratization – next to what he calls the more “classical” path of intensified repression.Footnote26 “Executive aggrandizement” is the term Bermeo uses for this process when “elected executives weaken checks on executive power one by one, undertaking a series of institutional changes that hamper the power of opposition forces to challenge executive preferences”.Footnote27

While the literature thus agrees that the process of autocratization has changed, it does not yet offer a systematic way of measuring the new mode of autocratization. The contributions build on case examples,Footnote28 statistics on selected indicators of gradual autocratization – that is, military coups and electoral fraud,Footnote29 opinion polls,Footnote30 or on changes in quantitative measures over a set time period.Footnote31 Most existing studies on the causes of autocratizationFootnote32 as well as descriptive overviewsFootnote33 are also biased in that they include only cases of complete breakdown of democracies. Such binary approaches not only fail to capture the often protracted, gradual and opaque processes of contemporary regime change,Footnote34 but also exclude important variations: autocratization in democracies that have not (yet) lead to complete breakdown (for example Hungary) and reversals in electoral autocracies that never became democracies (for example Sudan).

This is important because the archetype of dramatic reversals to closed autocracy is becoming rare – as are closed autocracies. About half of all countries were closed autocracies in 1980, but by 2017 they only make up 12% of regimes in the world.Footnote35 Contemporary autocrats have mastered the art of subverting electoral standards without breaking their democratic façade completely.Footnote36 Some have labelled this phenomenon “illiberal democracy”.Footnote37 Hence, as of 2017 a majority of countries still qualify as democracies (56%) and the most common form of dictatorship (32%) are the electoral autocracies.Footnote38

This dominance of multi-party electoral regimes made other analysists posit that democracy as a global norm after the end of the Cold WarFootnote39 continues to shape expectations and behaviour even of autocrats.Footnote40 If that is true, it does not come as a surprise that sudden reversals to authoritarianism have grown out of fashion since they involve the abolishment of multi-party elections in a coup. Such evident violations of democratic norms carry with them high legitimacy costs.Footnote41 Obviously “stolen” elections have triggered mass protests leading up to the colour revolutions.Footnote42 Likewise, the international community tends to sanction political leaders who explicitly disrespect electoral results, and international aid is often conditioned on a country holding multi-party elections.Footnote43 For instance, after the Gambian elections in 2016, president Jammeh’s refusal to accept defeat was quickly met with a military intervention from neighbouring countries – forcing him into exile.Footnote44 The same seems to apply for military coups – which might explain the sharp drop of coups in recent decades.Footnote45

A gradual transition into electoral authoritarianism is more difficult to pinpoint than a clear violation of democratic standards, and provides fewer opportunities for domestic and international opposition. Electoral autocrats secure their competitive advantage through subtler tactics such as censoring and harassing the media, restricting civil society and political parties and the undermining the autonomy of election management bodies. Aspiring autocrats learn from each otherFootnote46 and are seemingly borrowing tactics perceived to be less risky than abolishing multi-party elections altogether.

Thus, the literatures on autocratization as well as on the global rise of multiparty elections suggest that the current wave of autocratization unfolds in a more clandestine and gradual fashion than its historical precedents.

This leads to the next question: If autocratization occurs more gradually does this also reduce the magnitude of change? Bermeo suggests it does;Footnote47 others entertain more pessimism in books titled for instance “How democracies die” and “How democracy ends”.Footnote48 Yet, the recent literature on autocratization does not offer fine-grained, systematic empirical comparisons on this issue either.

Thus, we find important contributions and emerging propositions in the extant literature on contemporary autocratization. This article seeks to fill two main gaps. First, it provides a comprehensive conceptualization of autocratization with an accompanying operationalization with high validity, which is clearly needed to make future findings comparable. Second, we lack a comprehensive empirical analysis diagnosing contemporary autocratization in historical perspective: (1) its extent and which types of regimes are mostly affected compared to previous waves; (2) the nature of how it is enacted by rulers in comparative perspective; and (3) its pace and magnitude of change.

What is, and is not, autocratization?

Just like with the debate about whether democratization should be understood as a difference in kind (countries moving across a qualitative thresholdFootnote49), or in degree (gradual moves away from pure dictatorshipFootnote50), there are seemingly opposed understandings of autocratization. Three different terms are commonly used for moves away from democracy: backsliding, breakdown of democracy, and autocratization.Footnote51

We suggest that it is preferable to conceptualize autocratization – the antipode of democratization – as a matter of degree that can occur both in democracies and autocracies. Democracies can lose democratic traits to varying degrees without fully, and long before breaking down. For instance, it is still an open question if Orbán’s model of “illiberal democracy” in Hungary will transmute into authoritarianism, and non-democratic regimes can be placed on a long spectrum ranging from closed autocracies – such as North Korea or Eritrea – to electoral autocracies with varying degrees of closeness to democracy – such as Nigeria before the 2015 elections. Thus, even most autocracies harbour some democratic regime traits to different degrees (for example somewhat competitive, but far from fully free and fair elections) and can lose them, such as the 1989 military coup in Sudan when Omar Al-Bashir replaced an electoral autocracy with one of Africa’s worst closed dictatorships.

The classic literature focuses on the breakdown of democraciesFootnote52 even if some also identified gradual erosion of democracy in this earlier period.Footnote53 Sudden transitions dominated the moves away from democracy in the 1960s and 1970s making it a proper label for moves away from democracy at the time. However, the concept of “breakdown” is useful only for a subset of possible episodes of autocratization. First, it requires a crisp approach to the difference between democracy and dictatorship to enable the identification of the point of breakdown. That excludes studies of the protracted undermining of democratic institutions encapsulated by autogolpe and unfinished degeneration of qualities in democracies, as well as the waning away of partial democratic qualities in electoral authoritarian regimes. This is particularly problematic for the contemporary period when instances of sudden autocratization – coups d’état for instance – are rare.

Some scholars have suggested democratic backsliding to denote the diminishing of democratic traits. For example, Bermeo defines backsliding as “state-led debilitation or elimination of any of the political institutions that sustain an existing democracy.”Footnote54 Waldner and Lust understand backsliding as a “deterioration of entails a deterioration of qualities associated with democratic governance, within any regime” (emphasis added).Footnote55 While we are sympathetic to Waldner and Lust’s move away from an exclusive focus on democracies, we find the use of term backsliding problematic for three reasons: First, democratic backsliding implies a decline “in terms of” democracy and thus a conceptual extension beyond the democratic regime spectrum would border to conceptual stretching.Footnote56 From our point of view, an already autocratic country cannot undergo “democratic” backsliding into a deeper dictatorship. Second, the term suggests that regimes slide “back” to where they were before whereas in reality they may develop in a new direction, to a different form of authoritarianism for example.Footnote57 Finally, “sliding” makes it sound like an involuntary, unconscious process, which does not do justice to conscious actions political actors take in order to change a regime. It simply invokes the wrong kind of notion about the process.

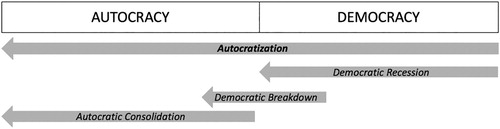

Third, we suggest that the overarching, or superior in Sartori’s terms, concept is autocratization.Footnote58 Semantically, it signals that we study the opposite of democratization, thus describing “any move away from [full] democracy”.Footnote59 As an overarching concept autocratization covers both sudden breakdowns of democracy á la Linz and gradual processes within and outside of democratic regimes where democratic traits decline – resulting in less democratic, or more autocratic, situations (). This conceptualization enables us to study both the pace and the methods of bringing a regime closer to a closed dictatorship, while keeping the distinction between democratic recessions starting in democracies, democratic breakdowns, and further consolidation of already authoritarian regimes.

To provide a comprehensive definition of autocratization processes, we use the term democratic recession to denote autocratization processes taking place within democracies, democratic breakdown to capture when a democracy turns into an autocracy, and autocratic consolidation as designation for gradual declines of democratic traits in already authoritarian situations.

Operationalization and data

Contemporary political science puts a heavy emphasis on identification of causal factors in experimental research designs. However, we cannot randomly assign either autocratization nor its potential causes to countries. Whether we like it or not, we must rely on observational data to depict, understand, and explain a phenomenon like autocratization. Taking one step back, any causal analysis is predicated on an accurate description of the outcome: how do we know an autocratization process when we see it? What are the more useful ways to decipher the dynamics and depict patterns, so as to facilitate descriptive inferences?

While there is relatively satisfactory data on sudden breakdowns – for instance on military coupsFootnote60 and dichotomous measures focusing on transitions from democracy to autocracy recorded in extant datasetsFootnote61 – we have lacked sufficiently nuanced yet systematic cross-national, times-series data on various aspects of regimes to detail incremental autocratization processes.

This article presents a novel approach identifying autocratization episodes – connected periods of time with a substantial decline in democratic regime traits. We use V-Dem’s dataFootnote62 on 182 countries from 1900 to the end of 2017, or 18,031 country-years.Footnote63 To identify autocratization episodes, we rely on the Electoral Democracy Index (EDI, v2x_polyarchy). The EDI captures to what extend regimes achieve the core institutional requirements in Dahl’s famous conceptualization of electoral democracy as “polyarchy”: universal suffrage, officials elected in free and fair elections, alternative sources of information and freedom of speech as well as freedom of association.Footnote64 For present purposes, V-Dem’s EDI has four key advantages. First, V-Dem data provide vast temporal and geographical coverage with data reaching back to 1900. Second, the EDI reflects how democratic a political regime is de-facto beyond the mere de-jure presence of political institutions. Additionally, it has a strong theoretical foundation in regime attributes that Dahl has identified as core requirements for an electoral democracy.Footnote65 Finally, as a continuous index of de-facto levels of democracy it is sensitive to gradual and slow-moving autocratization processes.

The EDI runs on a continuous scale from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a more democratic dispensation. We operationalize autocratization as a substantial decline on the EDI (within one year or over a connected time period). A decline is substantial if it amounts to drop of 0.1 or more on the EDI. The choice of cut-off point on a continuous index is naturally arbitrary but a change of 10% seems a reasonable and intuitive choice for the following reasons. This relatively demanding cut-off point of 0.1 minimizes the risk of measurement error driving the results since it requires more of an agreement among V-Dem coders that declines occurred among the 40 components of the EDI to achieve this magnitude of difference on the EDI scale.Footnote66 The cut-off point should also be high enough to rule out inconsequential changes but low enough to capture substantial yet incremental changes that do not amount to a full breakdown. A typical example would be the series of declines in democratic qualities in Hungary from 2006 to 2017 adding up to drop of the EDI of 0.11. In appendix A4, we demonstrate the robustness of our main findings to a higher cut-off point.

Episodes of autocratization have a start and an end. We proceed in two steps to identify such episodes. First, we identify potential autocratization episodes, which are adverse regime change of any magnitude. Second, we exclude all cases that involve only minor overall change, hence are not really cases of autocratization.

First, a potential autocratization episode starts with a decline on the EDI of 0.01 points or more, from one year to the next. We chose this relatively low threshold in order to spot the very beginning of incremental autocratization episodes.Footnote67 Second, we follow the potential episode as long as there is a continued decline, while allowing up to four years of temporary stagnation (no further decline of 0.01 points on the EDI) in order to reflect the concept of slow-moving processes that can move in fits and starts with a careful autocrat at the helm. The potential autocratization period ends when there are no further declines on the EDI of 0.01 or more over four years, or if the EDI increases by 0.02 points or more during one of those years since the latter would indicate a potential democratization episode.Footnote68

Second, we calculate the total magnitude of change from the year before the start of an episode to the end, and record as manifest autocratization episodes only those which add up to a change of at least 0.1 (10% of the total 0–1 scale) on the EDI.Footnote69

These coding rules ensure that periods of some fits and starts in what is often a protracted and messy process, are counted as one episode while at the same time minimizing the risk that measurement error plays a role in determining when an episode starts or finishes. Appendix A.E also demonstrates that the main findings of this article are robust to modifications of these coding rules.

For some analyses, one obviously needs a clear-cut distinction between democracies and autocracies. Following Lührmann et al.,Footnote70 we define countries as democracies if they hold free and fair and de-facto multiparty elections, and achieve at least a minimal level of institutional guarantees captured by the EDI (universal suffrage, officials elected in multiparty elections, freedom of association and alternative sources of information).

Diagnosing autocratization from 1900 to 2017

Here we present the first ever comprehensive identification of the 217 autocratization episodes taking place in 109 countries from 1900 to 2017 (Table A1 in the Appendix) leaving only 69 states unaffected (Table A2 in the Appendix).Footnote71 This count includes 33 countries classified as autocracies in 2017 such as North Korea and Angola who seem to be caught in an “autocracy trap” and due to the “floor effect” never had much possibility to become worse. The remaining 36 “non-autocratizers” are classified as democracies in 2017. This group consists mainly of countries with a long democratic history, such as Sweden and Switzerland, or that democratized recently, such as Bhutan and Namibia. Additionally, seven countries experienced autocratization solely due to foreign invasion during the two World Wars.Footnote72

Roughly two-thirds the autocratization episodes (N = 142, 65%) took place in already authoritarian states. Noteworthy are the many (60) episodes of autocratization in Africa, most of which occurred in electoral autocracies where autocratization dissipated initial democratic gains. For instance, three autocratization episodes in Sudan (1958–1959; 1969; 1989–1990) followed military coups disposing presidents elected in less-than perfect elections.

About a third of all autocratization episodes (N = 75) episodes started under a democratic dispensation. Almost all of the latter (N = 60, 80%) led to the country turning into an autocracy. This should give us great pause about spectre of the current third wave of autocratization. Very few episodes of autocratization starting in democracies have ever been stopped before countries become autocracies.

The third wave of autocratization is real and endangers democracies

Huntington conspicuously identified three waves of democratization and two waves of reversals.Footnote73 Our new measure of autocratization episodes picks up these two reverse waves and demonstrates that a third wave of autocratization is now unfolding.

For the precise delineation of the reverse waves – or waves of autocratization – we deviate slightly from Huntington’s original approach in order to reflect our conceptual and methodological innovations. First, we take as our point of departure democracy in Dahl’s understanding as “polyarchy”.Footnote74 With its seven (later collapsed to six) institutional requirements it is much more ambitious, and demanding, than Huntington’s Schumpeterian measure focusing on competition.Footnote75 Second, we are concerned here with gradual moves away from democracy. Huntington focused in his 1991 book on the crisp distinctions of democratic transitions and breakdowns. He speaks of a democratization wave when the transitions to democracy as events outnumber the democratic breakdowns.Footnote76 Our approach better captures the empirical realities – in particular during recent decades – that regime change is typically gradual and slowly leading to hybridization into electoral authoritarianism instead of sudden, dramatic transitions. The more sensitive and fine-grained measures we have at our disposal compared to what was available to Huntington, also make it possible to pick up such dynamic processes in a greater number of countries than Huntington could capture with binary transitions. Therefore, we use the direction of these changes to delineate waves of autocratization. We define as an autocratization wave the time period during which the number of countries undergoing democratization declines while at the same time autocratization affects more and more countries.Footnote77

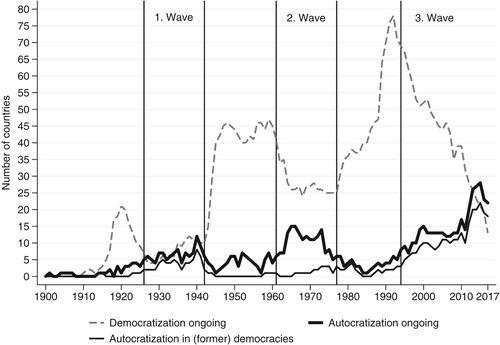

In the dashed grey line represents the number of countries that were affected by democratization each year.Footnote78 The black, thick line represents the number of countries that underwent autocratization each year. The black, thin line indicates how many of the latter started in democracies. Thus, delineates the three waves of autocratization: the first wave of autocratization occurred roughly from 1926 to 1942 and the second from 1961 to 1977. The post-cold war democratization surge already slowed down in the early 1990s and gradually reverse processes began to spread, beginning in Russia, Armenia and Belarus. Therefore, we can for the first time show that the third wave of autocratization already began in earnest in 1994. Notably, his undercurrent remained under the radar of most political scientists until Carothers declared “The End of the Transition Paradigm” in his seminal 2002 article.Footnote79 By 2017, the third wave of autocratization dominated with the reversals outnumbering the countries making progress. This had not occurred since 1940.

The dates for the first two reverse waves presented here are very similar to Huntington’s despite the conceptual and measurement differences (first reverse wave 1922–1942; second reverse wave to 1960–1975). There were 32 autocratization episodes in the first wave; 62 episodes during the second reversed wave; and 75 episodes occurring since the start of the third wave.Footnote80 A list of these episodes is found in Appendix B.

One observation immediately stands out from . Whereas the first reversed wave affected both democracies and autocracies and the second reversal period almost only worsened electoral autocracies, almost all contemporary autocratization episodes affect democracies. We are the first to show also this systematic difference. It is a source of concern especially given the finding reported above that few such episodes stop short of decent into authoritarianism. At the same time, fewer autocracies are affected by autocratization, that is, transition from electoral to closed autocracy. This reflects the trend that even in the authoritarian regime spectrum multi-party elections have become the norm.Footnote81

Post-communist East European countries account for 16 mainly protracted, autocratization episodes in the third wave for example the gradual autocratization processes in Russia, Hungary, and Poland. The third wave of reversals may still be mounting affecting as many as 22 countries in 2017. At the same time, the share of countries in the world that are democratic remains close to its highest ever – 53%. To some extent, the latter explains the former. The more democratic countries there are, the greater the likelihood that democracies suffer setbacks.

In sum, an important characteristic of the third wave of autocratization is unprecedented: It mainly affects democracies – and not electoral autocracies as the earlier period – and this occurs while the global level of democracy is close to an all-time high. Hence, for now at least, the trend is manifest, but less dramatic than some claim. This observation reiterates Brunkert, Kruse and Welzel’s finding that while the centennial democratic trend has passed its climax, the ongoing reverse process remains relatively mild.Footnote82

In democracies: the third wave of autocratization has a legal facade

Arguably, the loss of democratic traits in regimes that were democratic when an autocratization episode started matters more for the state of democracy in the world than further deterioration in already autocratic regimes. In this and the next section, we analyse these 75 episodes of autocratization of democracies in more depth.

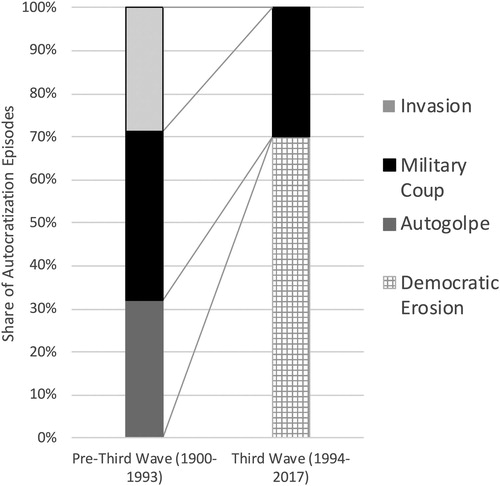

The case-based literature suggests that incumbents behind the current processes of autocratization are using mostly legal means and that illegal power grabs have become less frequent. We test this proposition by distinguishing between three different types of autocratization strategies based on how they abolish or undermine democratic institutions. The results are reported in . The analysis uses original data covering all autocratization episodes affecting democracies from 1900 to 2017.Footnote83

Figure 3. Types of autocratization of democracies.

Note: 28 episodes are included in the pre-third wave period, and 47 in the third wave.

The first and second waves of reversals were almost completely dominated by the “classic” form of autocratization tactics of illegal access to power, such as a military coup (39% of episodes) or foreign invasion (29%), and by autogolpes, where the chief executive comes to power by legal means but then suddenly abolishes key democratic institutions such as elections or parliaments (32%). The paradigmatic example of an autogolpe is president Fujimori’s suspension of the Peruvian constitution and parliament in 1992.Footnote84 Even Hitler came to power by legal means and then disposed democratic institutions with the “Ermächtigungsgesetz” (Enabling Act) in 1933.

Democratic erosion became the modal tactic during the third wave of autocratization. Here, incumbents legally access power and then gradually, but substantially, undermine democratic norms without abolishing key democratic institutions. Such processes account for 70% in the third reversal wave with prominent cases of such gradual deterioration in Hungary and Poland. Aspiring autocrats have clearly found a new set of tools to stay in power, and that news has spread.

In democracies: the third wave of autocratization is gradual

We have developed another new metric to measure the rate of autocratization in an informative way: maximum annual depletion rate. This metric captures how fast democratic traits decline during an autocratization episode in terms of changes from one year to the other on the V-Dem EDI. Using the maximum allows us to distinguish between episodes where a period of gradual declines combines with a sudden decline in democratic traits; and stretches that consist of gradual declines only. The advantage of the maximum depletion rate is that a high value indicates that the episode encompassed a sudden and radical change whereas a low value indicates an autocratization process that was incremental throughout. For ease of interpretation, we report maximum depletion rate values as a percentage of 1 (the highest possible score on EDI). Thus, if the maximum change in the EDI from one year to the next during an autocratization episode was −0.1, the corresponding autocratization rate is 10%.

For instance, the autocratization episode in Germany from 1930 to 1935 started with three years of gradual declines during the Weimar Republic. Yet, the main characteristic of this episode was Hitler’s accession to power in 1933 and the subsequent sudden breakdown of the democratic system. This is reflected by a high maximum depletion rate of 26%. Conversely, chapters such as Turkey’s from 2008 to 2017 and Russia’s from 1993 to 2017, involve only gradual changes – reflected by relatively low depletion rates of 7% (Turkey) and 5% (Russia). Alternative measures of pace such as the average depletion rate, the annual depletion rate and the decay rate, do not fully capture the difference between these two patterns. However, we include those as robustness tests to the subsequent empirical analysis (see more detailed discussions in Appendix C and E).

Figure D.1 in Appendix D shows a box plot comparing autocratization during the three reversal waves using this new metric. The median autocratization rate during the first and second waves was 31% and it dropped to 8% in the third wave. At the bottom end of the scale with a 3.8% maximum depletion rate we find with the extremely gradual autocratization process in Philippines from 2001 to 2005, followed by Vanuatu’s spell from 1988 to 1996 at 4.3%. The most sudden breakdowns occurred after the German invasion in the Czech Republic (55%) and in the Netherlands (52%) during World War II.

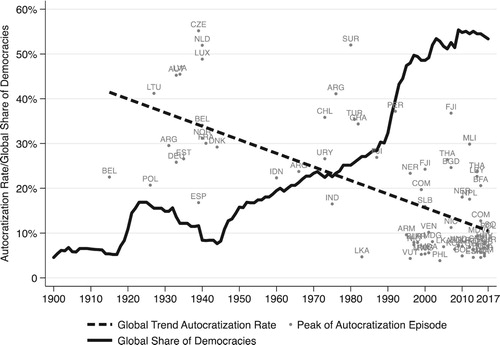

The rate of autocratization of democracies has dropped significantly (r = −0.66, dashed line on ) over time. At the same time, the global share of democracies increased remarkably – to hover well-above 50% after the turn of the century (black line). The global share of democracies is negatively and statistically significantly correlated with the autocratization rate. This relationship holds even when controlling for important confounders such as GDP, time since transition, level of democracy and foreign occupation as well as the types of autocratization reported in the prior section. Based on these regression analyses (results omitted here, see Appendix C), the rate of autocratization among democracies is predicted to drop from 35% when few countries were democratic (15%; for example, in the early 1930s) to 10% in 2017 when more than half of the world’s countries were democratic. This finding is robust to alternative specifications of the autocratization rate (Appendix C) as well as of the autocratization episodes (Appendix E).

Figure 4. Global trend rate of autocratization in democracies and share of democracies.

Note: The autocratization rate captures how fast the V-Dem Electoral Democracy Index declines at the peak of the autocratization episode in terms of changes from one year to the other. High values indicate sudden autocratization and low values more gradual. The x-axis of the figure shows the year where the peak of the autocratization rate occurred during the episode.

However, since we have to rely on observational data and a relatively small number of cases (75), we need to acknowledge these empirical tests as tentative findings. Nevertheless – as discussed in the literature review – there are reasonable intuitions for why a global rise of democracy should be expected to have a dampening effect on the rate of autocratization.

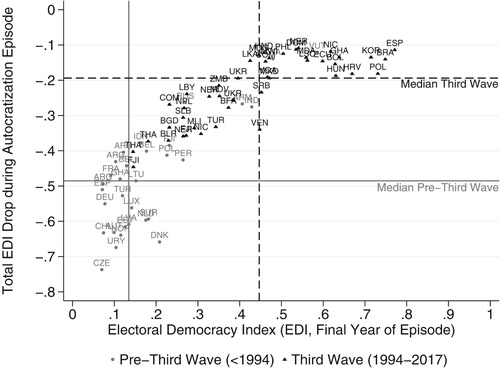

This development results in opposite expectations for the further prospects of democracy. On the one hand, autocratization has become more obscure and therefore one can suspect less likely to produce triggers for mobilization of pro-democratic forces. On the other hand, autocratization has also become less severe – at least on average in (former) democracies. illustrates how the effect of autocratization on the level of democracy has changed over time. The y-axis shows the total EDI drop during an autocratization episode and the x-axis the EDI score at the final year of autocratization. Before 1994, autocratization typically resulted in the dramatic transitions to closed autocracy with a median EDI score of 0.13 at the end of the episode. During the third wave of autocratization, the median democracy level at the end of autocratization episodes remains much higher with a score of 0.45 on the EDI. Also, the median total decline of democratic attributes during the third wave (−0.19) is less than half of the decline during the pre-third wave period (−0.50). This is mainly due to the emergence of the phenomenon of democratic erosion (33 out of 47 cases, or 70%) in the third wave, which was not discernible before.

The sudden forms of autocratization – invasions, military coups, autogolpes –always result in a democratic breakdown. Even democratic erosion processes are more often than not lethal for democracy: 18 (55%) of them have resulted in democratic breakdowns; only 5 (15%) processes have stopped before democracy broke down and 10 (30%) were still ongoing in 2017.Footnote85

Conclusion: the third wave of autocratization

This article presents the first systematic empirical analysis of contemporary autocratization in historical perspective. The article, first, contributes with a new method to identify not only sudden but also gradual autocratization episodes, providing a comprehensive empirical overview of adverse regime change from 1900 to today across the democracy-autocracy spectrum. This new operationalization pinpoints the start and end year of autocratization processes, which facilitates a new generation of studies for instance on the drivers of autocratization onset and sequential pathways during episodes.

Second, we provide evidence that contemporary declines of democracy amount to a third wave of autocratization. A key finding is that the present reverse wave – starting after 1993 – mainly affects democracies, unlike prior waves. What is especially worrying about this trend is that historically, very few autocratization episodes starting in democracies have been stopped short of turning countries into autocracies.

Furthermore, we present a series of descriptive tests corroborating key claims found in the extent literature but not tested before on systematic evidence: Contemporary autocratizers mainly use legal and gradual strategies to undermine democracies. Based on original data, we show that about 68% of all contemporary autocratization episodes starting in democracies are led by incumbents who came to power legally and typically by democratic elections. Conversely, during the pre-third wave period most autocratization episodes included an illegal power grab, such as a military coup. Whereas autocratizers before the third wave took clearly recognizable moves such as issuing a new non-democratic constitution or dissolved the legislature, most contemporary autocratizers do not change the formal rules. Thus, also the way incumbents undermine democracy has become more informal and clandestine.

Finally, we devise a new metric – the autocratization rate – capturing how fast regimes lose their democratic quality from one year to the other measured as a percentage change of the highest possible value of V-Dem’s EDI. We can then show that autocratization has become much more gradual than before. Its maximum rate declined from a median of about 31% in the pre-third wave period to about 8% in the third wave. This trend is strongly correlated with the changes in the global share of democratic regimes. As democracy spread around the globe in the 1990s and 2000s, autocratization became more gradual.

By now, most regimes – even autocracies – hold some form of multiparty elections. Sudden and illegal moves to autocracy tend to provoke national and international opposition. The tests we present suggest that contemporary autocratizers have learned their lesson and thus now proceed in a much slower and much less noticeable way than their historical predecessors. Thus, while democracy has undoubtedly come under threat, its normative power still seems to force aspiring autocrats to play a game of deception.

Consequently, states hit by the third wave of autocratization remain much more democratic than their historical cousins. On the one hand, this gives hope that the current wave of autocratization might be milder than the first and second waves. On the other hand, the third wave may still be picking up. It has affected 22 countries in 2017 and more are on the threshold. For these countries, two scenarios are plausible: Because autocratization is more gradual, democratic actors may remain strong enough to mobilize resistance. This happened for instance in South Korea in 2017, when mass protests forced parliament to impeach the president, which reversed the prior autocratization trend.Footnote86 Conversely, initial small steps towards autocracy brought other countries – such as Turkey, Nicaragua, Venezuela and Russia – on a slippery slope deep into the authoritarian regime spectrum. Future research needs to investigate what distinguishes these two scenarios and how autocratization can be stopped and reversed. Yet, one conclusion is clear: As it was premature to announce the “end of history” in 1992, it is premature to proclaim the “end of democracy” now.

FDEM-2018-0218.R2_online-appendix_AL.docx

Download MS Word (639.9 KB)Acknowledgements

For helpful comments, we thank Scott Gates, Kyle Marquardt, Jan Teorell, Joe Wright, three anonymous reviewers and participants of the APSA Conferences (8/2017; 8/2018), the ECPR General Conferences (9/2017; 8/2018), the V-Dem Research conference (5/2018) the post-doctoral working group at the University of Gothenburg and the HU/Princeton workshop on constitutionalism, dissent and resistance (6/2018), where earlier versions of this article were discussed. In particular, we are grateful to Rick Morgen who helped to better operationalize our idea of autocratization episodes. We also benefited immensely from Philipp Tönjes’ and Sandra Grahn’s skillful research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on the contributors

Anna Lührmann is Deputy Director of the V-Dem Institute and Assistant Professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of Gothenburg.

Staffan I. Lindberg is Professor of Political Science, Director of the V-Dem Institute at University of Gothenburg and one of six Principal Investigators for V-Dem.

ORCID

Anna Lührmann http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4258-1088

Staffan I. Lindberg http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0386-7390

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See for example Altman and Perez-Liñan, “Explaining the Erosion of Democracy”; Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding”; Cassini and Tomini, “Reversing Regimes and Concepts”; Coppedge, “Eroding Regimes”; Diamond, “Facing Up Democratic Recession”; Haggard and Kaufmann, Dictators and Democrats; Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die; Lührmann et al., “State of the World”; Mounk, The People vs. Democracy; Runciman, How Democracy Ends; Snyder, On Tyranny; Tomini and Wagemann, “Varieties of Democratic Breakdown”; Waldner and Lust, “Unwelcome Change.”

2 E.g. Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding”; Runciman, How Democracy Ends.

3 Linz, Breakdown of Democratic Regimes.

4 Lührmann et al., “State of the World.”

5 Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die; Snyder, On Tyranny.

6 Mechkova, Lührmann, and Lindberg, “How Much Backsliding?”

7 Runciman, How Democracy Ends.

8 Norris, “Is Western Democracy Backsliding?”; Brunkert et al., “Culture-bound Regime Evolution.”

9 Dahl, Polyarchy; Dahl, On Democracy.

10 Huntington, The Third Wave.

11 Fukuyama, The End of History.

12 Svolik, Politics of Authoritarian Rule.

13 Schedler, The Politics of Uncertainty; Diamond, “Thinking about Hybrid Regimes.”

14 Freedom House, Freedom in the World, 2008.

15 Diamond, “The Democratic Rollback”; Freedom House, Freedom in the World, 2008.

16 Merkel, “Are Dictatorships Returning?”; Levitsky and Way, “Myth of Democratic Recession.”

17 Freedom House, Freedom in the World, 2018.

18 Lührmann et al., “State of the World.”

19 Diamond, “Facing Up Democratic Recession”; Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die; Kurlantzick, Democracy in Retreat.

20 Mechkova, Lührmann, and Lindberg, “How Much Backsliding?”

21 Waldner and Lust, “Unwelcome Change,” 14.

22 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding,” 6.

23 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding,” 14; Diamond, “Facing Up Democratic Recession.”

24 Svolik, “Which Democracies will Last?”

25 Mechkova, Lührmann, and Lindberg, “How Much Backsliding?”

26 Coppedge, “Eroding Regimes.”

27 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding,” 10.

28 Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die.

29 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding.”

30 Mounk, The People vs. Democracy.

31 Diamond, Facing Up Democratic Recession; Lührmann et al., “State of the World.”

32 E.g. Svolik , “Authoritarian Reversals and Democratic Consolidation”; Bernhard, Nordstrom, and Reenock, “Economic Performance and Democratic Survival”; Ulfelder and Lustik, “Modeling Transitions to Democracy”; Przeworski, Democracy and Development.

33 E.g. Merkel, “Are Dictatorships Returning?”; Erdmann, “Decline of Democracy”; Levitsky and Way, “Myth of Democratic Recession.”

34 Lueders and Lust, “Multiple Measurements of Regime Change.”

35 Closed autocracies are typically defined in the literature as regimes where the chief executive is not subjected to de jure multiparty elections. Thus, this category includes monarchies, military regimes, as well as one-party states.

36 Schedler, The Politics of Uncertainty; Levitsky and Way, Competitive Authoritarianism.

37 Zakaria, The Future of Freedom.

38 Lührmann, Tanneberg, and Lindberg, “Regimes of the World.”

39 Norris, “Does the World Agree?”; Hyde, The Pseudo-democrats’ Dilemma.

40 Diamond, “Liberal Democratic Order Crisis.”

41 Schedler, The Politics of Uncertainty.

42 Bunce and Wolchik, “Defeating Dictators”; Kuntz and Thompson, “More than Final Straw.”

43 Kim and Kroeger, “Rewarding Introduction of Multiparty Elections.”

44 See Searcey and Yaya Barry, “As Yahya Jammeh Entered Exile.”

45 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding.”

46 Hall and Ambrosio, “Authoritarian Learning.”

47 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding,” 17.

48 Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die; Runciman, How Democracy Ends.

49 See Przeworski, Democracy and Development.

50 See Collier and Adcock, “Democracy and Dichotomies”; Lindberg, Democracy and Elections in Africa, 24–27.

51 While these are the most commonly used terms, it is important to note that others exist as well such as “democratic erosion” (Coppedge, “Eroding Regimes”), “de-democratization” (Tilly, “Inequality, Democratization, and De-democratization”), “democratic recession” (Diamond, “Facing Up Democratic Recession”) or “closing space” (Carothers and Brechenmacher, “Closing Space”). For a more extensive list of terms used in the debate see Cassani and Tomini “Reversing Regimes and Concepts,” 4.

52 E.g. Linz, Breakdown of Democratic Regimes.

53 Przeworski, Democracy and Development.

54 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding,” 5.

55 Waldner and Lust, “Unwelcome Change,” 5.3.

56 Sartori, “Concept Misinformation in Comparative Politics.”

57 Runciman, How Democracy Ends, 3.

58 Sartori, “Concept Misinformation in Comparative Politics.”

59 Lindberg, Democratization by Elections, 12; Cassani and Tomini (Cassani and Tomini, “Reversing Regimes and Concepts”) define autocratization positively as a “process of regime change towards autocracy that makes politics increasingly exclusive and monopolistic, and political power increasingly repressive and arbitrary.” This definition differs from our approach to think about autocratization negatively – as a move away from democracy. We prefer our approach for two reasons. First, it is in-line with the common understanding of autocracy as non-democracy (e.g. Schedler, The Politics of Uncertainty). Second, our approach allows us to understand autocratization and democratization as mutually exclusive, which allows us to operationalize them unambiguously.

60 Powell and Thyne, “Global Instances of Coups.”

61 E.g. Bernhard, Nordstrom, and Reenock, “Economic Performance and Democratic Survival”; Haggard and Kaufman, Dictators and Democrats.

62 Coppedge et al., “V-Dem Dataset v8.”

63 Approximately half of the indicators in the V-Dem dataset are based on factual information from official documents such as constitutions. The remainder consists of expert assessments on topics like the quality of elections and de facto compliance with constitutional standards. On such issues, typically five experts provide ratings for the country, thematic area and time period for which they are specialists (Coppedge et al., “V-Dem Codebook v8”).

64 Dahl, Polyarchy; Dahl, On Democracy; Teorell et al., “Measuring Polyarchy Across the Globe.”

65 Lührmann et al. (Lührmann et al., “State of the World”) use V-Dem’s Liberal Democracy Index to identify democratic declines. The advantage of this alternative strategy is that it provides an early warning tool because liberal aspects of democracy often are the first to erode (see Coppedge, “Eroding Regimes”). However, the aim of this article is different. Namely, we want to provide a heuristic device, which facilitates the analysis of questions such as how liberal constraints influence the likelihood of autocratization. Therefore, we need to operationalize autocratization in a way that is parsimonious and does not include liberal aspects of democracy.

66 V-Dem aggregates the expert assessments using Bayesian IRT model (Pemstein et al., “The V-Dem Measurement Model”; Marquardt and Pemstein, “IRT Models”).

67 Robustness checks with different thresholds yield similar results in regression analysis (see Appendix A4).

68 A lower threshold of 0.01 for ending episodes would for instance lead to the episode in Russia to be limited to the years 2011–2017, even though already the years since 1993 saw major cumulative declines (−.19).

69 An alternative option would have been to use a rolling five-year average change on the EDI as for instance Coppedge (Coppedge, “Eroding Regimes”). However, our strategy gives us a start or end point of more gradual processes.

70 Lührmann, Tannenberg, and Lindberg, “Regimes of the World.”

71 This count includes only countries still in existence in 2017.

72 Albania, Romania, Belgium, Denmark, France, Netherlands and Norway.

73 Huntington, The Third Wave.

74 Dahl, Polyarchy; Dahl, Democracy and its Critics.

75 See Doorenspleet (“Reassessing the Three Waves”) for a similar point.

76 Huntington, The Third Wave, 16.

77 It is somewhat ambiguous to precisely delineate a start and end point of autocratization and democratization waves every year given that at almost any given year there are a number of countries changing in both directions. Thus, the dates we suggest here should be understood to delineate the main part of a wave. But the issue about whether a wave started in exactly this year or that is not a critical issue in a century-long perspective. We identify an autocratization wave starting when the number of democratization episodes begins to decrease at the same time as autocratization episodes increase for two years in a row. It ends when autocratization episodes decline in number and democratization episodes increase over the next four years.

78 Following Doorenspleet (“Reassessing the Three Waves”) we focus our analysis on the number of countries. In Appendix D we show that the three reverse waves are also manifest when basing the graphical analysis on the share of countries. Democratization episodes are based on Lindberg et al. (“Successful and Failed Democratization”).

79 Carothers, “End of the Transition Paradigm.”

80 48 cases occurred in-between the waves.

81 Schedler, The Politics of Uncertainty; Levitsky and Way, Competitive Authoritarianism.

82 Brunkert et al. base their analysis on V-Dem data, but operationalize democratic trends differently, that is, focusing on a combination of liberal, electoral and participatory aspects. Consequently, their findings in detail differ from ours. For instance, they argue that the climax of democracy has been reached in about 2000 when 21% of the world’s population was living in what they term “full democracies”. Brunkert et al., “Culture-bound Regime Evolution,” 7.

83 The coding process proceeded in three steps: First, we used V-Dem data to identify whether or not the appointment of the Head of the Executive involved force (v2expathhs/v2expathhg; Coppedge et al., “V-Dem Codebook v8”). Second, taking this information into account, a research assistant coded the four sub-categories based on standard references such as Nohlen and Stöver (Elections in Europe), and Lentz (Encyclopedia of Heads of states), as well as case specific literature. Third, we verified the coding choices in particular with regards to borderline cases. Table A1 in the appendix shows the categorization of individual episodes.

84 Lentz, Heads of States 1945 Through 1992, 633; Levitsky and Ziblatt, “How Democracies Die.”

85 The following five episodes stopped before breakdown: Bolivia (2015), Ecuador (2010), Nicaragua (1999), South Korea (2014) and Vanuatu (1996). Brazil, Croatia, Dominican Republic, Ghana, Hungary, Lesotho, Moldova, Niger, Poland and Spain were ongoing in 2017.

86 Shin and Moon, “South Korea after Impeachment,” 130.

Bibliography

- Freedom House. Freedom in the World. Freedom House, 2008. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2008.

- Freedom House. Freedom in the World. Freedom House, 2008. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/FH_FITW_Report_2018_Final_SinglePage.pdf.

- Altman, D., and A. Pérez-Liñán. “Explaining the Erosion of Democracy: Can Economic Growth Hinder Democracy?” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute Working Paper No. 42, 2017.

- Bermeo, N. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27, no. 1 (2016): 5–19. doi: 10.1353/jod.2016.0012

- Bernhard, M., T. Nordstrom, and C. Reenock. “Economic Performance, Institutional Intermediation, and Democratic Survival.” The Journal of Politics 63, no. 3 (2001): 775–803. doi: 10.1111/0022-3816.00087

- Brunkert, L., S. Kruse, and C. Welzel. “A Tale of Culture-bound Regime Evolution: The Centennial Democratic Trend and its Recent Reversal.” Democratization 26, no. 3 (2018): 422–443. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1542430.

- Bunce, V. J., and S. L. Wolchik. “Defeating Dictators: Electoral Change and Stability in Competitive Authoritarian Regimes.” World Politics 62, no. 1 (2010): 43–86. doi: 10.1017/S0043887109990207

- Carothers, T. “The End of the Transition Paradigm.” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 1 (2002): 5–21. doi: 10.1353/jod.2002.0003

- Cassani, A., and L. Tomini. “Reversing Regimes and Concepts: From Democratization to Autocratization.” European Political Science 57, no. 3 (2018): 687–716. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12244

- Collier, D., and R. Adcock. “Democracy and Dichotomies: A Pragmatic Approach to Choices About Concepts.” Annual Review of Political Science 2 (1999): 537–565. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.537

- Coppedge, M. “Eroding Regimes: What, Where, and When?” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute Working Paper No. 57, 2017.

- Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, C. H. Knutsen, S. I. Lindberg, S.-E. Skaaning, J. Teorell, D. Altman, et al. “V-Dem Codebook v8.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project (2018).

- Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, C. H. Knutsen, S. I. Lindberg, S.-E. Skaaning, J. Teorell, D. Altman, et al. “V-Dem Dataset v8.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute (2018).

- Dahl, R. A. Democracy and its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

- Dahl, R. A. On Democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998.

- Dahl, R. A. Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1971.

- Diamond, L. “Facing up to the Democratic Recession.” Journal of Democracy 26, no. 1 (2015): 141–155. doi: 10.1353/jod.2015.0009

- Diamond, L. “The Democratic Rollback.” Foreign Affairs 87, no. 2 (2008): 36–48.

- Diamond, L. “The Liberal Democratic Order in Crisis.” The American Interest, 2018. https://www.the-american-interest.com/2018/02/16/liberal-democratic-order-crisis/.

- Diamond, L. “Thinking about Hybrid Regimes.” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 2 (2002): 21–35. doi: 10.1353/jod.2002.0025

- Erdmann, G. “Decline of Democracy.” Comparative Governance and Politics 1 (2011): 21–58.

- Fukuyama, F. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press, 1992.

- Haggard, S., and R. R. Kaufman. Dictators and Democrats - Masses, Elites and Regime Change. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016.

- Hall, S. G. F., and T. Ambrosio. “Authoritarian Learning: A Conceptual Overview.” East European Politics 33, no. 2 (2017): 143–161. doi: 10.1080/21599165.2017.1307826

- Huntington, S. P. The Third Wave of Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. London: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.

- Hyde, S. D. The Pseudo-democrat’s Dilemma. Why Election Observation Became an International Norm. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011.

- Kim, N. K., and A. Kroeger. “Rewarding the Introduction of Multiparty Elections.” European Journal of Political Economy 49 (2017): 164–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2017.02.004

- Kurlantzick, J. Democracy in Retreat: The Revolt of the Middle Class and the Worldwide Decline of Representative Government. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013.

- Lentz, H. M. Encyclopedia of Heads of States and Governnments, 1900 Through 1945. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1999.

- Lentz, H. M. Heads of States and Governments - A Worldwide Encyclopedia of Over 2,300 Leaders, 1945 Through 1992. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1994.

- Levitsky, S., and L. A. Way. Competetive Authoritariansism: Hybrid Regimes after the Cold War, Problems of International Politics. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Levitsky, S., and L. A. Way. “The Myth of Democratic Recession.” Journal of Democracy 26, no. 1 (2015): 45–58.

- Levitsky, S., and D. Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. London: Penguin Books, 2018.

- Lindberg, S. I., P. Lindenfors, A. Lührmann, L. Maxwell, J. Medzihorsky, R. Morgan, and M. C. Wilson. “Successful and Failed Episodes of Democratization: Conceptualization, Identification, and Description.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute Working Paper No. 79, 2018.

- Linz, J. J. The Breakdown of Democratic Regimes - Crisis, Breakdown, & Reequilibration. Edited by J. J. Linz and A. Stepan. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978.

- Lührmann, A., V. Mechkova, S. Dahlum, L. Maxwell, M. Olin, C. S. Petrarca, R. Sigman, M. C. Wilson, and S. I. Lindberg. “State of the World 2017: Autocratization and Exclusion?” Democratization 25, no. 8 (2018): 1321–1340. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2018.1479693

- Lührmann, A., M. Tanneberg, and S. Lindberg. “Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes.” Politics and Governance 6, no. 1 (2018): 60–77. doi: 10.17645/pag.v6i1.1214

- Marquardt, K., and D. Pemstein. “IRT Models for Expert-coded Panel Data.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute Working Paper No. 41, 2017.

- Mechkova, V., A. Lührmann, and S. I. Lindberg. “How Much Democratic Backsliding?” Journal of Democracy 28, no. 4 (2017): 162–169. doi: 10.1353/jod.2017.0075

- Merkel, W. “Are Dictatorships Returning? Revisiting the ‘Democratic Rollback’ Hypothesis.” Contemporary Politics 16, no. 1 (2010): 17–31. doi: 10.1080/13569771003593839

- Mounk, Y. The People vs. Democracy: Why Our Freedom is in Danger. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018.

- Nohlen, D., and P. Stöver. Elections in Europe: A Data Handbook. Nomos, Germany: Baden-Baden, 2010.

- Norris, P. “Is Western Democracy Backsliding? Diagnosing the Risks.” Journal of Democracy (Online Exchange) (2017). https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/online-exchange-%E2%80%9Cdemocratic-deconsolidation%E2%80%9D.

- Pemstein, D., K. Marquardt, E. Tzelgov, Y. Wang, J. Krusell, and F. Miri. “The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-national and Cross-temporal Expert-coded Data”. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute Working Paper No. 21, 2nd ed., 2017.

- Przeworski, A. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Material Well-being in the World, 1950–1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Runciman, D. How Democracy Ends. London: Profile Books, 2018.

- Schedler, A. The Politics of Uncertainty: Sustaining and Subverting Electoral Authoritarianism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Snyder, T. On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century. 1st ed. New York: Tim Duggan Books, 2017.

- Svolik, M. W. “Which Democracies will Last? Coups, Incumbent Takeovers and the Dynamic of Democratic Consolidation.” British Journal of Political Science 45, no. 4 (2015): 715–738. doi: 10.1017/S0007123413000550

- Svolik, M. W. The Politics of Authoritarian Rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Tomini, L., and C. Wagemann. “Varieties of Contemporary Democratic Breakdown and Regression: A Comparative Analysis.” European Journal of Political Research 57, no. 3 (2018): 687–716. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12244

- Waldner, D., and E. Lust. “Unwelcome Change: Coming to Terms with Democratic Backsliding.” Annual Review of Political Science 21, no. 1 (2018): 93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-050517-114628