ABSTRACT

The article mainly seeks to explain the legislature’s preferences in social welfare before and after democratization using South Korea as a case study. Based on an original dataset that consists of all executive and of legislative branch-submitted bills between 1948 and 2016 – roughly 60,000– legislative priority on social welfare is compared over time, and tested using logistic regressions. The key focus of analysis is whether and how the level of democracy affected the degree and universality of social welfare priority. The findings show that the promotion of social welfare is positively related to higher levels of democracy in a continuous fashion, which clearly points to the need to avoid applying a simple regime dichotomy – authoritarian or democratic – when seeking to understand social welfare development. Going further, the article examines the legislature's priority in welfare issues within a presidential structure and under majoritarian electoral rule, at different levels of democracy. The result shows that the higher levels of democracy are, the more the legislative branch contributes to the overall salience of social welfare legislative initiatives as compared to the executive branch. Moreover, the legislative branch itself prioritizes a social welfare agenda – alongside democratic deepening – over other issues.

Introduction

The positive impact of democratization and multiparty competition on welfare expansion has been a widely accepted finding.Footnote1 On this, and using an integrated framework between authoritarian and democratic regimes, De Mesquita and others find the increasing level of democracy to be a key political condition for political elites providing goods and services to a wider range of people.Footnote2 That is, different levels of democracy are treated as political conditions – ones with varying institutional incentives – to provide different degrees of a public–private goods mixture.

Going beyond the existing approach, the article considers both successful and failed welfare attempts, who specifically supports each attempt, and how their role has changed at different democratic levels. Because the authoritarian welfare scholarship has focused on expenditure or a few landmark pieces of legislation, many of the unsuccessful or less salient legislative attempts regarding social welfare emanating from marginalized actors such as opposition party members have hitherto gone unnoticed.Footnote3 Furthermore, due to the lack of data availability, information on which specific political actors in the government supported particular social welfare initiatives has not been systematically scrutinized. For instance, when Knutsen and Rasmussen measured “the degree of pension universality” in autocracies, they based their study on eight groups but were uncertain about whether the key ones of interest to their paper – civil servants and the military – were included.Footnote4 Finally, even if the authoritarian legislature started to be noticed as a point of policy compromises, there has still not been much attention paid to how specific institutional arrangements – for example majoritarian electoral rules or presidential constitutional structures – can affect the social welfare agenda within an autocratic legislature.

In this article, I examine the changes in the legislative prioritization of social welfare issues in South Korea (henceforth, Korea) between 1948 and 2016. Korea is an ideal case to test how the different political actors’ policy preferences on social welfare issues have changed along with the deepening of democracy for the following reasons. First, over the past 70 years, the country has experienced different levels of democracy over time (from 0 to 0.84 by annual Polyarchy scoreFootnote5 in ) and, at the same time, the degree of legislative priority given to social welfare issues has also shifted substantially over time (from 0 to 27% according to the annual welfare bill sponsorship proportion that I calculated based on the ensuing definition thereof). Second, because Korea consistently allowed legislative initiatives to be taken by both the executive and legislative branches during the period of observation (this is not the norm in other countries; for instance, the executive branch cannot sponsor bills in the United States), it provides a unique opportunity to examine the changing priorities of presidents – both dictatorial and democratically elected ones – and legislatures over the degree and types of social welfare issue prioritization at different levels of democracy.Footnote6 Third, the whole universe of both successful and unsuccessful bills submitted since 1948 is publicly available, and from this I built an original welfare bill sponsorship dataset. Fourth, because the country consistently had strong majoritarian electoral rules and a presidential constitutional structure during the period of observationFootnote7, we can further our insights into how political actors’ social welfare preferences changes with democratic deepening within these specific institutional arrangements.

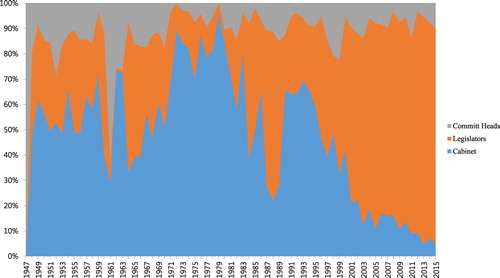

Figure 1. Change of Democracy and Legislative Independence Levels in Korea. Source: Polyarchy and Legislative Constraints indicators by Varieties of Democracy.

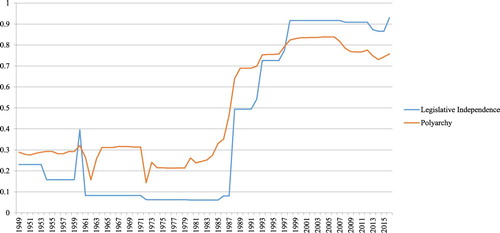

By analysing legislation patterns over time, I demonstrate that the legislative branch has steadily been more median voter-oriented than the executive branch in Korea. Moreover, under majoritarian electoral rules, lower levels of constraint through greater democratization (illustrated in the legislative constraint scoreFootnote8 in ) have led the legislative branch to increasingly prioritize and contribute to the overall saliency of social welfare issues. The article is organized as follows: First, after a brief introduction of the previous literature on social welfare expansion and the role of the legislature in authoritarian regimes, I will derive related testable hypotheses. Second, the article will point out political contexts in Korea and then specify how welfare bills (and universal welfare bills) are defined. Finally, both descriptive statistics and regression analyses are employed to examine the effect of democracy level on social welfare agenda promotion, as well as the legislative mechanism behind it.

Theory, Korean context and data

Social welfare expansion in authoritarian and democratic regimes

It has been repeatedly pointed out in the social policy literature that authoritarian regimes do not necessary avoid providing public goods. In addition to Bismarck’s utilization of social policy in imperial Germany– which is often identified as the origin of the modern welfare state – the majority of social welfare programmes were in fact introduced by authoritarian regimes.Footnote9 Moreover, several other empirical works have revealed that authoritarian regimes can extend welfare efforts under particular conditions – for example a favourable economic situation – and/or with particular motivations, such as: i) to control strategically important groups like the military or the government bureaucracy or ii) to pre-empt potential social unrest.Footnote10

However, ceteris paribus, higher levels of democracy are more likely to lead to the provision of public goods; empirical findings drawn from a large number of countries have demonstrated this, by showing that welfare spending increases in tandem with franchise extensions.Footnote11 The following political logics have been pointed out in explaining the positive impact of democratization on social welfare expansion meanwhile: On the one hand, mass enfranchisement can be approached as a tipping point that is qualitatively different from authoritarian rule. For instance Marshall points out that after achieving civil rights and political rights, people will then ask for social rights too – based on their now more socio-economically substantive understanding of democratic citizenship.Footnote12 Similarly, mass enfranchisement can be a critical turning point since it indicates expansion of the franchise to the poor – and the median voter in this context will ask for greater wealth sharing in light of typically right-skewed income distribution.Footnote13

On the other hand, there is an integrated approach that views social welfare provision between authoritarian and democratic regimes respectively on a continuous scale. De Mesquita and others’ work is an exemplary case;Footnote14 they argue that, even though there will be mixture of public and private goods for any regime type, higher levels of public goods provision are expected to occur in line with the upward progression of the democratic level. This for the following reason: Leaders in authoritarian regimes are supported by a winning coalition – an indispensable core group that keeps these leaders in power – and goods and services thus have to be provided to prevent the defection of its members, which can result in the overthrowing of those leaders. Even though leaders naturally prefer to keep onside only a small circle of winning coalition members so as to maximize their own share of power, if the coalition becomes too big to be maintained by private goods alone then they can mix more public goods into the deal. In other words, although political elites are likely to provide goods and services to a wider range of people after mass enfranchisement – meaning when that winning coalition becomes over 50% of those involved – there can still be varying degrees of public goods provision across authoritarian regimes too.

Taking a cue from the integrated approach, the relationship between private and public goods provision can be understood on a continuous scale; we can therefore argue that the lower a country’s level of democracy, the greater the level of goods that will be provided privately. Core supporters of the regime will be key beneficiaries of these private goods and usually they include organized groups with identifiable features: ruling party members, soldiers, land owners, civil servants, teachers, industrial workers, business groups and the like.Footnote15 Because these groups retracting their support can increase the chance of regime collapse or leadership change, a wide range of private goods tend to be provided to them. These can take either a direct material form – such as fertilizers, subsidized housing, construction materials, food – or a more indirect one – for example regulatory favours, policy influence, access to economic rents, political postsFootnote16– albeit with material implications. By and large, these private goods are discretionary distributions that do not take the form of formal social welfare (see online appendix for a detailed distinction between formal and informal social welfare). Therefore, with regards to the levels of democracy, the following hypothesis can be derived:

H1: The higher the level of democracy, the more formal social welfare will be.

H2: The higher the level of democracy, the more formal social welfare will be targeted towards median voters instead of narrow groups.

The relationship between legislature and democracy on social welfare

When it comes to democratic regimes, it is widely accepted that legislatures can be used to hold leaders accountable; it is also well known that their relationship with the executive branch affects important political and economic outcomes.Footnote21 Unlike in democracies, legislatures were often marginalized in the study of policies in authoritarian regimes however – due to the perception of them having no substantial impact.Footnote22 That is, in authoritarian regimes democratic institutions – constitutions, legislatures, elections and political parties – exist either only for window-dressing purposes, to reinforce a dictator’s position through demonstrating invincibility (with overwhelming victories), gathering information on potential opponents or detecting lower-level corruption.Footnote23 However, when it comes to deciding the specific form of policies, the legislature in authoritarian regimes is often not treated as being a meaningful point of analysis. That is, because they exist only for dictators then their main perceived function is to rubber stamp government-proposed legislation – while they can be suspended anytime they challenge the government. From this perspective, obstruction of authoritarian executives is unlikely, infrequent and inconsequential.

However, often noted as “consultative authoritarianism” or “authoritarianism with binding legislature”Footnote24, authoritarian legislatures are increasingly being portrayed now on the basis of more nuanced views. Evidence drawn from various locations shows that, when it comes to legislative amendments and reversals, performance varied significantly between countries; whether a regime is ruled by a collective executive or not is an important factor herein.Footnote25 Similarly, nomination procedures, competitiveness and the level of professionalism of the legislature vary across authoritarian regimes – and they affect the specific forms taken of co-optation strategies too.Footnote26

As for the effect of the legislature on social welfare, students of authoritarian institutions have demonstrated that it can be a place in which policy compromises are organized through concessions.Footnote27 For instance, the legislature can be used to buy support from political elites and citizens using both private and public goods.Footnote28 This is particularly more likely if dictators cannot generate rents from natural resources (as in oil-rich nations), but depend instead on revenues garnered through domestic investment and growth.Footnote29 Under these circumstances, the legislature is not a venue where autocrats can just unilaterally adjust policies regarding private and public goods as they wish. Various organized groups, for example trade unions or religious leaders, who are cooperating with the dictator will seek more concessions, whereas opposition ones will ask for more median voter-oriented public goods given their lack of access to state resources. And, as long as there are competitive elections, not all ruling-party legislators are safe from potential defeat, so some can – similar to their democratic counterparts – use the legislature for position-taking, credit-claiming and advertising.Footnote30

However what is still lacking in the literature is a clear understanding of the specific institutional arrangements under which the legislature can prioritize public goods, such as social welfare. Among other things, the potential effect of two political institutions with wider relevance can be identified: presidential structure and majoritarian electoral rule. Drawing from the theories of democratic countries, the following expectations can be derived in relation to social welfare.

With respect to the presidential structure, it has been accepted that in presidential democracies, both the president and legislators are guaranteed to remain in power for a fixed term of office. Hence, within a given term, neither side can be fundamentally checked by threatening each other’s political life. Resonating greater levels of legislator independence, higher levels of legislative activism by individual legislators have been reported in presidential democracies than in parliamentary ones.Footnote31 Moreover, it has been claimed that presidential democracies yield more points of access, a space for new policy ideas and higher levels of transparency too.Footnote32 This policy environment can serve as a breeding ground for legislators who seek to maximize their political chances by venturing into new popular areas, such as the greater promotion of social welfare. And, ceteris paribus, the policy environment will become more favourable as the level of democracy advances.

Drawing insights from this, I argue that the degree of separation of powers should be approached along a continuous scale for both authoritarian and democratic regimes. In other words, it can be said that the extent to which the separation of powers principle is effective can vary between authoritarian legislatures (just like it can vary between different stages of democracies – in other words, democratic transition and consolidation). Connected with this, the greater independence of the legislature should be positively related to its more active prioritization of social welfare issues. The following hypothesis can thus be derived:

H3-a: The higher the level of democracy, the more the legislative branch will contribute to formal social welfare than the executive branch will under a presidential structure.

H3-b: The higher the level of democracy, the more the legislative branch will prioritize formal social welfare over other issues under majoritarian electoral rules.

H3-c: The higher the level of democracy, the more formal social welfare initiated by the legislative branch will be targeted towards median voters instead of narrow groups under majoritarian electoral rule.

First, one of the most established findings in social policy scholarship is that partisanship matters. The power resources theory tells us that the strength of the labour movement and of left-wing parties are known as the key factors driving welfare expansion.Footnote35 From this, we can expect legislators affiliated with left-leaning parties are more likely to push for social welfare issues than those connected to right-leaning ones are.

Second, gender is another important aspect. Existing works suggest that female politicians tend to be more oriented towards care and compassion for vulnerable groups like children and families, to promote education and health, and more likely to pass measures that benefit these marginalized people.Footnote36 Therefore, female legislators should be more likely to focus on social welfare issues than their male counterparts are.

Third, which level a legislator was elected to should also matter. Korea has had a two-tiered electoral system – one party level and one district level – during both democratic and authoritarian rule. Considering that proportional representation electoral rules tend to lead to larger welfare states, specifically by incentivizing politicians to promote inclusive nationwide interestsFootnote37, legislators elected at the party level by proportional representation electoral rules should promote social welfare more than their district-elected colleagues do.

Fourth, we can also derive an expectation from the status of a legislator’s affiliated party. Authoritarian welfare research has shown that, in the context of electoral authoritarianism, opposition parties tend to prioritize public goods more than the ruling party does – given the former’s lack of access to the necessary state resources with which to target particular groups.Footnote38 Although the resource-access gap is not as large for more democratized countries, it still exists. Therefore, ceteris paribus, opposition party members are more likely to focus on social welfare.

From these prior expectations, it is clear that being left-wing, female, party-elected, and affiliated with opposition party is positively associated with prioritizing social welfare. However, the key focus of this article is on how each legislator trait varies in relation to the level of democracy. Following the expectation derived from the majoritarian electoral rule, I anticipate seeing all legislators converge on prioritizing more social welfare irrespective of their individual characteristics. Therefore, in light of the previous expectations, the following hypothesis can be derived:

H4: under the majoritarian electoral rule, deepening of democracy will make legislators prioritize social welfare issues in general. But this effect will be particularly pronounced for male, ruling party, party-tier, right-leaning legislators who do not usually prioritize social welfare issues compared to female, opposition party, district-tier, left-leaning legislators.

Korean context and data

Korea is an ideal case to test the four specified hypotheses, for several reasons: variations in the level of democracy over time; the continuous experience of presidentialism as well as majoritarian electoral rules; and, analytical advantages coming from the bill sponsorship record – which exists through the whole period of observation.

In understanding Korea’s democratic experiences, several critical junctures can be pointed out. The country was colonized by the Empire of Japan for the first half of the twentieth century and then finally liberated in 1945. After three years of US trusteeship, Korea held its first-ever election in 1948. Then what followed came close to “competitive authoritarianism”Footnote39, lasting until 1987 – on the one hand competitive elections existed but, on the other, presidents occasionally came to and maintained power through rigged elections, military coups and/or by removing term limits. The forward progress and back-pedalling of democratic levels during the authoritarian period is reflected in the scores measuring democracy in . Even if 1987 marks the first sustained democratic transition with mass enfranchisement and a free-and-fair election (although 1948 saw the first mass enfranchisement, the democracy was short-lived), it was not until 2008 that Korea would pass Huntington’s two turn-over test (1991) and ‘consolidate’ its democracy.

Here, the article examines an original dataset that is based on the full universe of sponsored social welfare bills in Korea between 1948 and 2016. As pointed out, both the executive and legislative branch can propose bills in Korea. In the case of legislative branch-proposed ones, these can be divided into individual legislator-submitted ones and head of the standing committee-submitted ones. In the case of legislator-initiated bills (also known as private members’ bills), each sponsoring legislator must have the support (co-sponsorship) of ten or more members of the National Assembly.Footnote40And, there is no upper limit to the number of co-sponsors. Considering that legislator-initiated bills have been the dominant form within the legislative branch (making up more than 95% thereof), the ensuing analyses will be primarily conducted based on them.

The original dataset used here consists of roughly 60,000 submitted bills (in the years between 1948 and 2016). Specifically, 6,259 and 50,130 bills were submitted during the authoritarian and democratic periods of rule in Korea respectively. The whole dataset was collected from the legislation search engineFootnote41, and coded as “welfare” if the title and the key changes of a bill in the official summary section (the opening lines) include one of the following contents described in .Footnote42 In the case of a bill including both welfare and non-welfare related changes, it was coded as either welfare or non-welfare based on the primary emphasis in the bill’s introduction. Such coding makes both the welfare and non-welfare categories mutually exclusive and totally exhaustive.

Table 1. Categories of formal social welfare.

Taking a cue from previous findings that formal welfare with a universal appeal tend to resonate particularly well with median votersFootnote43, a distinction is made based on the universalistic or particularistic nature of welfare. It is coded as “particularistic” if a benefit is catered to “organized group(s)” and/or specific “geographical constituent(s)” such as teachers, military, civil servants, politicians, farmers or business organizations.Footnote44 A welfare bill is coded as “universalistic”, meanwhile, if the benefit is provided to median voters or the marginalized, many of whom tend to be non-organized and non-geographical targets – such as children, the elderly, the disabled and women. Coding in this way, the proportion of welfare bills was 21% (from the noted total overall number of approximately 60,000) while universal welfare ones made up 88% of those welfare bills during the period of observation (see the online appendix for the detailed conceptual distinction and examples).

Before getting into the analysis, it needs to be pointed out that not all welfare bills are created equal. Specifically, if we consider the direction and significance of each welfare bill it should be noted that social policy ones sponsored during authoritarian periods can be about rolling back social welfare benefits or expanding insignificant ones just for signalling purposes. Bearing this in mind, I sampled 500 social welfare bills from each period to check whether those introduced during the authoritarian periods were more trivial and more likely to be about retrenchment. I coded the substantiality and direction of each bill according to the coding schemes employed in the previous works to distinguish social policy bills (significance: trivial or significantFootnote45; direction: retrenchment or expansionFootnote46). The results show that submitted social policy bills are mostly about expansion (94%) and are indeed significant (93%); there is no systematic difference between the two periods.

Analysis

Testing the four hypotheses

The four specified hypotheses on expected legislative patterns regarding social welfare issues are tested here using logistic regressions. Model 1 tests H1, which expects that as democratization proceeds, more legislative attention will be directed towards social welfare issues in general. Model 2 is confined to social welfare bills only, and tests H2, which posits that higher levels of democratization are positively related to universal (rather than particularistic) welfare. Furthermore, Model 3 adds an interaction effect between the democratization level and the entity of origin of bill submission – the executive branch or legislative branch – and examines whether individual legislators are increasingly playing an important legislative role in pushing the social welfare agenda in general (Model 3-a) and universal welfare one in particular (Model 3-b). Finally, Model 4 tests the interaction effect of four individual legislators’ characteristics—party ideology, gender, elected tier, and party status (ruling/opposition party) and democracy levels on social welfare agenda setting.

The outcome variable is binary (0/1) for all three models: Model 1, Model 3-a, Model 4 being welfare (1) or non-welfare (0); Model 2 and Model 3-b being universal welfare (1) or particularistic welfare (0). The predictor variable of interest is the level of democracy (continuous, from 0 to 1) measured as a Polyarchy score for Model 1 and 2, the entity of bill sponsorship (cabinet 0, individual legislators 1, and head of the standing committee 2) for Model 3, and four legislator characteristics for Model 4: legislators’ gender (female 1, male 0); elected level (party 1, district 0); ideological spectrum of legislators’ affiliated party (0 centre-right, 1 centre-left, 2 left, 3 othersFootnote47); and the party’s status in the legislature (opposition 0, ruling party 1).

Other variables used as control ones draw from legislative studies, authoritarian welfare and the political contexts of Korea. They are: i) electoral cycle (non-electoral cycle 0, from ‘a year before an election day’ to ‘the election day’ 1); ii) gross domestic product per capita (continuous, logged); iii) population size (continuous, logged; iv) type of legislative initiative (enactment 0, amendment 1); v) the total number of submitted bills in each legislative session (continuous). The logistic regression results are based on robust standard errors, and they are reported in the parentheses.

Hypotheses 1 and 2

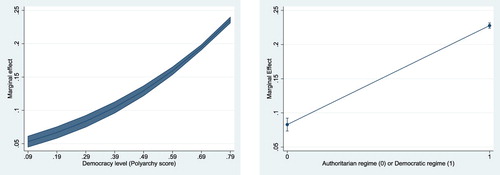

Based on Model 1, it can be said that the level of democracy is positively related to prioritizing welfare bills (). Moving from the lowest to highest democracy level, the predicted probability of a bill concerning welfare more than quadruples – from 5% to 24% (). In contrast, if a simple binary distinction is used based on the year 1987 (before: authoritarian; after: democracy), the likelihood of a submitted bill being concerned with social welfare moves to a much lesser extent–from 9% to 22%.

Table 2. Logistic regression results by all political actors.

Figure 2. Marginal effect of democratic levels on social welfare bills (left: continuous scale; right: dichotomous scale).

Moreover, considering that there is a substantial within-regime-type variation in the sponsored welfare bill proportion per year (from 0 to 19% during authoritarian rule and from 5 to 27% during the democratic era) then prioritization of social welfare should be understood from the perspective of a continuous democracy scale existing. Seeing it in this way allows for a more nuanced understanding of these events, instead of glossing them over by focussing only on the regime type. This pattern clearly diverges from the Korean welfare state literature which often draws sharp distinctions between authoritarian and democratic regime periods by labelling the former “developmental welfare state/productivist regime” and the latter “inclusive welfare state” based on social solidarity, universality and with redistributive implications.Footnote48

Model 2 shows that H2 is also confirmed, in line with the expected prediction. A submitted welfare bill is substantially more likely to be universalistic in nature – and thus concern median voters and the marginalized – than it is particularistic – the predicted probability moves from 48% to 89%. These two patterns clearly resonate with the development of social welfare in Korea. On the one hand, the lower level of democracy during the authoritarian period features the underdevelopment of income-maintenance programmes and social services, as well as low overall state expenditure on social welfare. Oftentimes, the role of income-maintenance programmes was fulfilled through other discretionary benefits – which were not part of formal social welfare – targeting only particular regions or groups. Often labelled as “surrogate social policy” or “social protection by other means”, these include corporate welfare, occupational pensions, or agriculture subsidies.Footnote49

On the other hand, evidence from the previous literature shows that when formal social welfare was adopted it was mainly for the key supporters of presidents. In combination with a long-term strategy – namely legitimization through economic growth – short-term strategies are also needed to pre-empt potential challenges and threats. As is clear from the cross-national evidence, the dictator’s elite supporters – rather than the mass public – pose the primary challenge to the governing power; in four out of five cases, dictators were ousted from power by government insiders.Footnote50 In this sense, with its transparency, predictability and irreversibility, formal social welfare was a crucial means for Korean dictators to show their commitment to their core supporters. Therefore, it is not surprising to note that, throughout the authoritarian period in Korea, most key formal welfare benefits were directed/prioritized towards civil servants, the military and teachers. Specifically, in Korea government pension schemes were first introduced to the military and civil servants in 1957 and 1960 respectively; they saw increases in the levels of benefit enjoyed and of coverage during the 1970s and 1980s meanwhile. National health insurance first started with employees of large companies in 1977, and afterwards moved to civil servants and private school teachers too.

To examine how this pattern is reflected in the welfare-specific categories, I broke down each social welfare bill based on the subject of ‘key beneficiaries’. This resulted in 123 categories, which include a wide range of individuals such as victims of disasters, veterans, refugees, the disabled, foreign workers, women, consumers, depositors with banks, farmers/agriculture industry, fishermen/fishing industry, small and medium enterprises, small retailers, teachers, soldiers and the like. By examining the proportion of specific welfare categories for particular subjects (from the total welfare bills submitted during each of the two regime periods), below lists for who a particular social welfare measure was prioritized in one regime as compared to in the other. Echoing the idea of a minimum winning coalition by De Mesquita and othersFootnote51, civil servants, the military and teachers tended to be prioritized significantly more during the authoritarian period (making up 30 to 40% of the total welfare bills); median voters and the marginalized received more social policy attention during the democratic period, meanwhile. Moreover, it also confirms the key point of the developmental welfare stateFootnote52, by showing that three aspects of welfare – education, health and compensating for work-related injuries – known to be more growth-friendly were promoted during the authoritarian regime period.

Table 3. Different targets of social welfare bills by regime type.

Hypothesis 3

Models 1 and 2 are heavily based on the expectations drawn from previous scholarship, and the results clearly show that the Korean case does not deviate from these. Model 3 is based on an original hypothesis that the article has formulated out of authoritarian legislature, presidential studies, and electoral studies and the results clearly add an interesting nuance to the relationship between social welfare promotion (both degree and type) and the level of democracy. To begin with, from the political logic of separation of powers in presidential structure, Hypothesis 3-a predicted that the legislative branch under presidential regime will increasingly contribute to the agenda setting of social welfare along with the deepening of democracy. To examine if this is the case, depicts the role of individual legislators in welfare bill sponsorship over time. It shows the percentage of total welfare bills sponsored by particular actors in given years, and the trend clearly indicates that legislators have gained importance after the democratic transition – being behind more than 90% of all social welfare bills after 2011. Moreover, along with the progress of democracy in Korea, legislative constraints have concomitantly been minimized (the correlation coefficient between the two indicators described in is 0.96 and statistically significant at 1 percent level) while their legislative activities have substantially increased (going from 16 sponsored bills in 1948 to 4,624 such items in 2016).

In addition, the within-regime variation should not escape our attention. Similar to the importance of applying a continuous democracy scale for understanding the welfare orientation of legislators, their legislative contribution over time can be understood better in light of variances in democratic level at different points in times. Even during the democratic period, legislators undeniably have played a more significant role in the course of moving from the democratic transition (1987–2008) to consolidation period (2008–2016). And, with regards to the authoritarian regime period, the Korean case shows that there was a sudden plummeting of legislators’ contributions to social welfare bills between 1972 and 1979. This change is not coincidental, since 1972 is the year when President Park violated the democratic principle by imposing the Yushin Constitution – reflected in the change of Polyarchy score from 0.3 to 0.2 in above. Judging by these patterns, we can confirm Hypothesis 3-a. Considering that students of East Asian welfare states have emphasized the importance of the executive branch (particularly bureaucrats) or expert institutionsFootnote53, findings here clearly point to include the legislative branch as a key political actor.

clearly shows the shift in legislators’ welfare bill contribution – vis-à-vis the other two initiators of bills – to the social welfare agenda at different levels of democracy. However, how much they actually contributed to the whole social agenda and the degree of their preference for welfare are two different things. In other words, they can increasingly contribute to the social welfare agenda as the level of democracy increases but end up being less pro-welfare themselves. For this, the preference dimension is separately tested with Model 3-a and 3-b in .

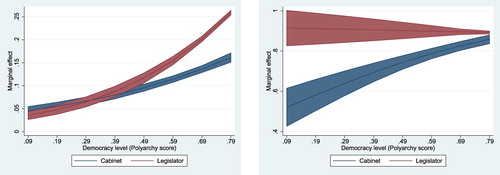

The results (Model 3-a) show that legislators are not necessarily more prone to promoting social welfare than the cabinet. However, the interaction term shows that legislators are much more sensitive to increasing democracy levels (compared to cabinet) when it comes to promoting social welfare. That is, as can be demonstrated from below (left-hand side), the likelihood that a submitted bill concerns welfare increases both for legislator- and cabinet-initiated bills. However, the conditional effect is strong enough to make legislators to appear more pro-welfare in general. It is particularly noteworthy that the democratic level 0.5 forms a point of divergence when the degree of welfare prioritization between cabinet- and legislator-submitted bills crosses over. As is clear from the Polyarchy score in earlier, this coincides with the time period of the democratic transition. Therefore, we can also confirm Hypothesis 3-b.

Figure 4. Marginal effect of democratic levels on social welfare bills by sponsoring entity (left: social welfare or others; right: universal or particularistic welfare).

As for the universality of welfare tested in Model 3-b (Hypothesis 3-c), interestingly enough, the direction is completely reversed from Model 3-a. Statistical results tell us that legislators are more likely to focus on universal welfare than the cabinet but, at the same time, the latter is much more sensitive to the effect of democratization. This difference is clearly manifested in (right-hand side). That is, we can see that legislators have constantly and clearly supported universal welfare more than the cabinet – regardless of democratic level.

However, when we shift our attention to the direction of change occurring along with the progression of democracy, we observe a contrasting image. Welfare bills sponsored by both the cabinet and legislators merge in their universalistic character by a dramatic shift of cabinet welfare bills from particularistic to universalistic—nearing the highest levels of democracy, the universality of welfare between legislators and cabinet is indistinguishable. While Model 1 and Model 2 tell us the importance of approaching social welfare from different degrees of democracy, an important insight we can glean from Model 3 is to add information about who supported a particular type of welfare. Namely here there are high levels of association between legislators and universal welfare on the one hand, and cabinet members and particularistic welfare on the other. Moreover it also shows that cabinet bills have substantially shifted their focus from particularistic to universal welfare between the two regime types, while the emphasis has not changed much for legislators under either. Combined with the results from Models 1 and 2, this indicates that legislators have constantly been more concerned with universal welfare – but the degree to which they prioritize social welfare issues in general (out of their total legislative efforts) rose after the democratic transition, when serious multiparty competition now came into being. Furthermore, it also confirms the previous observation that welfare benefits for the military, teachers, politicians and civil servants were directly controlled by the president (in the form of cabinet bills) during authoritarian periods. However, this lost its importance after the democratic transition.

To begin with, Model 4-a tested the effect of legislator attributes on social welfare prioritization (hypothesis 4) without interacting with the levels of democracy (). The result shows that being a female legislator, elected at the party level and affiliated with an opposition party are important positive predictors of a bill submitted concerning welfare. This is all in line with the expectations derived from previous works. However, in contrast to the established welfare state literature, the known ideological spectrum of the legislators’ party manifests no difference. This is not completely surprising, since key political divisions have not clearly formed around social welfare issues in Korea.Footnote54 For instance, empirical evidence drawn from mass opinion surveys, public voting patterns, party manifestoes, legislative speeches and legislative voting demonstrates mixed results in that income, occupation status, and views on social welfare issues have not been consistent predictors in pubic voting or legislative behaviour to date.Footnote55

Table 4. Logistic regression results by legislators.

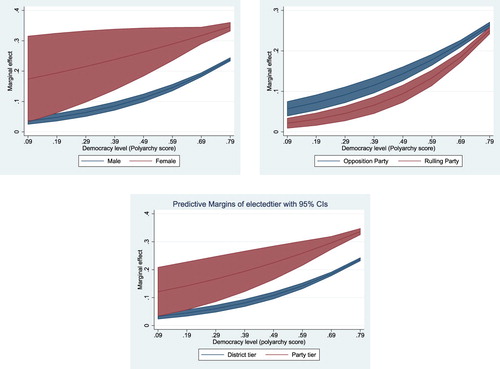

Insofar as gender, elected level and party status are concerned, separate regressions are conducted by adding an interaction term of each legislator character – to investigate how the effect has changed across different levels of democracy (Hypothesis 4). In line with the prediction, for all three variables that turned out to be effective in Model 4-a, we can observe a convergence towards more social welfare bill sponsorship. This can be inferred from both the negative direction of interaction terms in Models 4-b, 4-c and 4-d as well as from the predicted probability changes at different democracy levels illustrated in below. That is, being male, a ruling-party member or district-level elected are all positively affected by the impact of increasing levels of democracy on social welfare, more so than for those who are female, opposition party members or party-level elected. As a result, by 2016, the gap regarding social welfare promotion had been significantly narrowed. Particularly, the indistinguishable gap between opposition and ruling party members resonates with previous findings that competition between parties has resulted of late in a “race to the top” and a “ratcheting up” of welfare policy reform promises in Korea.Footnote56

Figure 5. Marginal effect of democratic levels on social welfare bills by legislators' attributes (left: gender; right: party status; bottom: elected tier).

For the sake of the robustness of the findings that I have presented so far, I removed each social welfare category described in to examine if anything changes (i.e., this is not included here to preserve space). The results show none of the key findings that I previously demonstrated are hereafter altered.

Concluding remarks

The article has examined the legislative prioritization of social welfare issues in Korea in the years from 1948 to 2016, with the whole universe of submitted bills being taken into account. The following three key findings stand out: First, confirming previous scholarship, the level of democracy is positively related to the sponsorship of more social welfare bills in general and of universalistic ones in particular. However, the evidence clearly suggests that this relationship can be better understood from a continuous-scale perspective instead of from a dichotomous one. Second, going further, the article has examined the relationship between democratic deepening and the role of the legislature in prioritizing social welfare issues and contributing to its overall saliency in light of two political institutions with global relevance: presidential structure and majoritarian electoral rule. On the one hand, and drawing insights from the separation of powers logic pointed out in presidential studies, the article has shown the increasing role of the legislative branch in prioritizing social welfare as occurring in tandem with rising levels of democracy. On the other, and building on the Downsian expectation of what happens under majoritarian electoral rules, the article has demonstrated the increasing policy orientation towards median-voter-friendly social policies unfolding together with rising levels of democracy. This has clearly manifested itself in the form of the increasing welfare-orientation of legislators, irrespective of their gender, elected tier (party or district), or their affiliated party status (to the opposition or the ruling party).

The article adds to the recent approach that tries to understand the role of legislatures in social welfare-promotion within authoritarian and democratic regimes from an integrated theoretical framework perspective. However, moving beyond this it adds to the authoritarian welfare debate by showing how two institutional effects often associated with democracies – the separation of powers in presidentialism and median voter-convergence under majoritarian electoral rules – can be understood from an integrated perspective: the higher the level of democracy, the more clearly visible these effects will be. To demonstrate this point, I focused on Korea between 1948 and 2016 considering its three ideal conditions: i) has been under presidential structure and majoritarian electoral rule, ii) has seen substantial changes both in the level of democracy and the degree of social welfare agenda setting, and iii) has consistently allowed both legislative and executive branch to sponsor bills. The article follows examples of previous works on authoritarian legislaturesFootnote57 in the sense that the careful examination of one country’s political system can lay important foundations for broader theoretical claims being generated.

Finally, I want to suggest two potential avenues for future research. First, as made clear from this article, successful and unsuccessful legislative attempts should both be analysed together to gain a broader sense of how particular social welfare legislation came into being. This is especially pertinent if the goal is to understand the preferences of particular political actors; analysing only successful attempts can clearly bias one’s results, since they may be only the tip of the iceberg. Going beyond a simple aggregation of failed attempts, future works can distinguish between these – since many of them tend to affect the successful ones either directly (by making some parts of unsuccessful bills be included in the eventually successful ones) or indirectly (by creating a bidding pressure during the legislative’s deliberation stage). Relatedly, second, formal social welfare itself can be broken down into different categories and closely examined by looking at which types are more likely to succeed, who key supporting actors were and what the underlying motivates have been.

Supplementary_document__20190404_.docx

Download MS Word (26.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Thomas Richter, Elena Korshenko, Masaaki Higashijima, Sinan Chu, Sijeong lim and David Kuehn for helpful feedback on parts of the article. The suggestions of the two anonymous reviewers were particularly helpful. The research also benefited from presenting findings at International Conference on Global Dynamics of Social Policy and at Authoritarian Politics research team meeting of the German Institute of Global and Area Studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jaemin Shim

Dr. Shim is currently a Thyssen post-doctoral research fellow at German Institute of Global and Area Studie. He has received a PhD in Politics at the University of Oxford and his primary research interests lie in welfare states, political institutions, and legislative politics. His dissertation “Welfare Politics in Northeast Asia: An Analysis of Welfare Legislation Patterns in South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan” investigates how changing power structure affect incentives and constraints of elected politicians and elite bureaucrats in supporting different types of welfare bills by applying both quantitative and qualitative methods to his original dataset. His wider work covers gender politics, party politics, and mass-elite representation gap.

Notes

1 Ansell and Samuels, Inequality and Democratization. Haggard and Kaufmann, Development, Democracy, and Welfare States; Lindert, Growing Public; Marshall, Citizenship and Social Class.

2 De Mesquita et al., The Logic of Political.

3 Examining only successful bills is particularly misguided in understanding preference of political actors since how particular legislative attempts become successful is more likely to be a result of actors’ capacity or surrounding situations – such as experience and expertise on issues, size of the political coalition or government type (divided or unified). Furthermore, existing works have repeatedly confirmed that bill submission data can be used to examine legislators’ preferences. For example, Alenman et al., Explaining Policy Ties in Presidential Congress or Talbert and Potoski Setting the Legislative Agenda.

4 Knutsen and Rasmussen, The Autocratic Welfare State.

5 The scale ranges from 0 to 1, and the higher number indicates higher democracy. This is measured through five subcomponents: freedom of association, clean elections, freedom of expression, elected officials and suffrage.

6 Considering that the president is the head of the executive branch and the person who should sign each submitted bill, the cabinet-sponsored ones have been directly related to the specific preferences of dictators (or of democratically elected presidents after 1987). In contrast, legislator-sponsored bills incorporate the preferences of both ruling and opposition party members.

7 Except for a brief period in the early 1960s, Korean politics has had a presidential structure. Although Korea has had mixed electoral rules where legislators were elected from the district and party tiers both during the authoritarian and democracy period, the party tier was either minor in terms of the proportion (roughly 15–25 of the legislators were elected from here between 1988 and 2004) or designed to amplify majoritarian bias (half to two-thirds of the party-tier seats were allocated to the top-ranked party at the district tier between 1963 and 1972, and between 1980 and 1988).

8 A higher score indicates greater legislative independence. It is measured by legislative constraint scores with the expert judgment on the question: “To what extent are the legislature and government agencies (e.g. comptroller general, general prosecutor or ombudsman) capable of questioning, investigating and exercising oversight on the executive?”

9 Rimlinger, Welfare Policy and industrialization; Mares and Carnes “Social Policy in Developing.”

10 Huber and Stephens, Development and Crisis of Welfare State.

11 Ansell and Samuels, Inequality and Democratization. Haggard and Kaufmann, Development, Democracy, and Welfare States; Lindert, Growing Public; Marshall, Citizenship and Social Class).

12 Marshall, Citizenship and Social Class; Melzer and Richard.

13 Melzer and Richard, “A Rational Theory of.”

14 De Mesquita et al. The Logic of Political.

15 Knutsen and Rasmussen, “The Autocratic Welfare State”

16 Magaloni and Kricheli “Political Order and One-Party”; Erzow and Frantz, “Dicators and Dictatorships.”

17 Acemoglu and Robinson, Economic Origins of Democracy.

18 Knutsen and Rasmussen, “The Autocratic Welfare Sate.”

19 Ibid.

20 De Mesquita et al., The Logic of Political.

21 For example, see Person and Tabellin, “Comparative Politics and.”

22 Levitsky and Way, “The Rise of Competitive.”

23 Levitsky and Murillo, “Variation in Institutional Strength.”

24 Wright, “Do Authoritarian Institutions Constrain?”

25 Bonvecchi and Simison, “Legislative Institutions and Performance”

26 Malesky and Schuler, “Nodding or Needling”

27 Gandhi, Political Institutions under Dictatorship.

28 Magaloni, “Credible Power-Sharing”

29 Gandhi, Political Institutions under Dictatorship

30 Mayhew, Congress: The Electoral Connection.

31 Olson and Mezey, Leigslatures in the Policy

32 Eaton, “Parliamentarism versus Presidentialism”

33 Duverger, Political Parties; Downs, “An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy.”

34 Gingrich, “Visibility, Values, and Voters”.

35 Esping-Andersen, The Three Worlds of.

36 Carroll, The Impact of Women.

37 Lijphart and Crepaz, “Corporatism and Consensus Democracy”

38 Gandhi, Political Institutions under Dictatorship.

39 Levitsky and Way, Competitive Authoritarianism.

40 Until 2003, the threshold was 20 members in Korea. Although their number varies over time, there were 200–300 elected legislators during the period of observation meanwhile.

41 Of the National Legislation Search Centre, run by the Ministry of Justice. Accessible online at: http://www.law.go.kr/main.html.

42 Here, the definition of welfare is based on the broad boundaries covered in the modern comparative welfare state literature.

43 Gingrich, “Visibility, Values, and Voters.”

44 These specific distinctions are drawn from Gamm and Kousser, “Broad Bills or Particularistic.”

45 Significant welfare bills include those making changes such as increasing the amount of subsidy/loan/compensation; extending the benefit-receiving period; or, relaxing the benefit-receiving conditions – for example contribution period, benefit-receiving period. These resonate with the categories used in a well-established welfare state project, Comparative Welfare Entitlement Data, by Scruggs, Jahn and Kuitto (accessible online at: http://cwed2.org/). See the online appendix for further details.

46 With regards to the contents of expansion and retrenchment, this coding scheme is mainly drawn from social policy bill coding by Klitgaard and Elmelund-Præstekær, “Policy or Institution?” See the online appendix for further details.

47 To list few, the known political spectrum of affiliated parties after 1987 can be categorized as follows: centre-right (Grand National Party, Democratic Liberal Party, Democratic Justice Party, Liberal Democracy Coalition, Democratic Liberal Party, Pro-Park Coalition, Korea People Party, Korea Democracy Party); centre-left (Uri Party, United Democratic Party, Democratic Party, New Democratic Republic Party, Creative Korea Party, United Democratic Party, Democratic Peace Party, New Politics People’s Congress, New Korean Democratic Party); left (Democratic Labour Party, New Progressive Party); and others (independent and other small parties). This is treated as a multinominal variable, considering that ideological spectrum of independent legislators is uncertain.

48 Kwon, The welfare state in Korea; Peng and Wong, “East Asia”

49 See Author, for a review of this literature.

50 Svolik, “Power Sharing and Leadership.”

51 De Mesquitaet et al., The Logic of Political.

52 Kwon, The Welfare State in Korea.

53 Ibid.

54 Instead, the primary divide between the left and right revolves around the issue of taking a diplomatic or military stance towards North Korea; the relationship to the US is also a key point of demarcation. The left/right favours a more dovish/hawkish approach to North Korea, while holding a position of less dependence/dependence on the US too.

55 For example, Kim et al., Changing Cleavage Structure in New Democracies, Huber and Inglehart, Expert Interpretations of Party Space and Party Locations.

56 Wong, Healthy Democracies.

57 Bonvecchi and Simison, “Legislative Institutions and Performance”; Malesky and Schuler, “Nodding or Needling.”

Bibliography

- Acemoglu, D., and J. A. Robinson. Economic Origins of Democracy and Dictatorship. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Alemán, Eduardo, and Ernesto Calvo. “Explaining Policy Ties in Presidential Congresses: A Network Analysis of Bill Initiation Data.” Political Studies 61, no. 2 (2013): 356–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00964.x

- Ansell, B. W., and D. J. Samuels. Inequality and Democratization. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Bonvecchi, A., and E. Simison. “Legislative Institutions and Performance in Authoritarian Regimes.” Comparative Politics 49, no. 4 (2017): 521–544. doi: 10.5129/001041517821273099

- Carroll, Susan J. The Impact of Women in Public Office. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001.

- De Mesquita, B. B., A. Smith, J. D. Morrow, and R. M. Siverson. The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge, Mass: MIT press, 2005.

- Downs, A. “An Economic Theory of Political Action in a Democracy.” Journal of Political Economy 65, no. 2 (1957): 135–150. doi: 10.1086/257897

- Duverger, M. Political Parties: Their Organization and Activity in the Modern State. London: Methuen, 1959.

- Eaton, Kent. “Parliamentarism Versus Presidentialism in the Policy Arena.” Comparative Politics 32, no. 3 (2000): 355–376. doi: 10.2307/422371

- Esping-Andersen, G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1990.

- Estévez-Abe, M. Welfare and Capitalism in Postwar Japan: Party, Bureaucracy, and Business. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Ezrow, N. M., and E. Frantz. Dictators and Dictatorships: Understanding Authoritarian Regimes and their Leaders. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2011.

- Gamm, G., and T. Kousser. “Broad Bills or Particularistic Policy? Historical Patterns in American State Legislatures.” American Political Science Review 104, no. 1 (2010): 151–170. doi: 10.1017/S000305540999030X

- Gandhi, J. Political Institutions Under Dictatorship. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Gingrich, J. “Visibility, Values, and Voters: The Informational Role of the Welfare State.” The Journal of Politics 76, no. 02 (2014): 565–580. doi: 10.1017/S0022381613001540

- Haggard, S., and R. R. Kaufman. Development, Democracy, and Welfare States: Latin America, East Asia, and Eastern Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Huber, John, and Ronald Inglehart. “Expert Interpretations of Party Space and Party Locations in 42 Societies.” Party Politics 1, no. 1 (1995): 73–111. doi: 10.1177/1354068895001001004

- Huber, E., and J. D. Stephens. Development and Crisis of the Welfare State: Parties and Policies in Global Markets. Princeton: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

- Elmelund-Præstekær, C., and M. B. Klitgaard. “Policy or Institution? The Political Choice of Retrenchment Strategy.” Journal of European Public Policy 19, no. 7 (2012): 1089–1107. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2012.672112

- Kim, Hee Min, Jun Young Choi, and Jinman Cho. “Changing Cleavage Structure in new Democracies: An Empirical Analysis of Political Cleavages in Korea.” Electoral Studies 27, no. 1 (2008): 136–150. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2007.10.004

- Knutsen, C. H., and M. Rasmussen. “The Autocratic Welfare State: old-age Pensions, Credible Commitments, and Regime Survival.” Comparative Political Studies 51, no. 5 (2018): 659–695. doi: 10.1177/0010414017710265

- Kornai, J. The Socialist System: The Political Economy of Communism: The Political Economy of Communism. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Kwon, H. J. The Welfare State in Korea: the Politics of Legitimization. Oxford: Springer, 1998.

- Kwon, H. J. “Transforming the Developmental Welfare State in East Asia.” Development and Change 36, no. 3 (2005): 477–497. doi: 10.1111/j.0012-155X.2005.00420.x

- Levitsky, S., and M. V. Murillo. “Variation in Institutional Strength.” Annual Review of Political Science 12 (2009): 115–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.091106.121756

- Levitsky, S., and L. A. Way. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Levitsky, S., and L. Way. “The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism.” Journal of Democracy 13, no. 2 (2002): 51–65. doi: 10.1353/jod.2002.0026

- Lijphart, A., and M. M. Crepaz. “Corporatism and Consensus Democracy in Eighteen Countries: Conceptual and Empirical Linkages.” British Journal of Political Science 21, no. 02 (1991): 235–246. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400006128

- Lindert, P. H. Growing Public: Social Spending and Economic Growth Since the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Malesky, E., and P. Schuler. “Nodding or Needling: Analyzing Delegate Responsiveness in an Authoritarian Parliament.” American Political Science Review 104, no. 3 (2010): 482–502. doi: 10.1017/S0003055410000250

- Magaloni, B. “Credible Power-Sharing and the Longevity of Authoritarian Rule.” Comparative Political Studies 41, no. 4–5 (2008): 715–741. doi: 10.1177/0010414007313124

- Magaloni, B., and R. Kricheli. “Political Order and one-Party Rule.” Annual Review of Political Science 13 (2010): 123–143. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.031908.220529

- Mares, I., and M. E. Carnes. “Social Policy in Developing Countries.” Annual Review of Political Science 12 (2009): 93–113. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.12.071207.093504

- Marshall, T. H. Citizenship and Social Class (Vol. 2). London: Pluto Press, 1992.

- Mayhew, D. R. Congress: The Electoral Connection (Vol. 26). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974.

- Meltzer, Allan H., and Scott F. Richard. “A Rational Theory of the Size of Government.” Journal of Political Economy 89, no. 5 (1981): 914–927. doi: 10.1086/261013

- Olson, D. M., and M. L. Mezey, eds. Legislatures in the Policy Process: The Dilemmas of Economic Policy (Vol. 8). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991

- Peng, I., and J. Wong. “East Asia.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Welfare State, edited by Francis G. Castles, Stephan Leibfried, Jane Lewis, Herbert Obinger, and Christopher Pierson, 657–671. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Persson, Torsten, Gerard Roland, and Guido Tabellini. “Comparative Politics and Public Finance.” Journal of Political Economy 108, no. 6 (2000): 1121–1161. doi: 10.1086/317686

- Rimlinger, Gaston V. Welfare Policy and Industrialization in Europe, America, and Russia. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1971.

- Svolik, M. W. “Power Sharing and Leadership Dynamics in Authoritarian Regimes.” American Journal of Political Science 53, no. 2 (2009): 477–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00382.x

- Talbert, Jeffery C., and Matthew Potoski. “Setting the Legislative Agenda: The Dimensional Structure of Bill Cosponsoring and Floor Voting.” Journal of Politics 64, no. 3 (2002): 864–891. doi: 10.1111/0022-3816.00150

- Wong, J. Healthy Democracies: Welfare Politics in Taiwan and South Korea. New York: Cornell University Press, 2006.

- Wright, J. “Do Authoritarian Institutions Constrain? How Legislatures Affect Economic Growth and Investment.” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 2 (2008): 322–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00315.x