ABSTRACT

The literature on the political “resource curse” has recently seen heated debates over the average causal effects of oil on democracy and the generalizability of the theory. One of the reasons these disagreements remain unresolved is that the causal mechanisms of the resource curse receive little scholarly attention and historical and international aspects are frequently overlooked. To address these problems, this study investigates the relationship between oil and the political regime in Brunei, arguably the most understudied state among the archetypes of the resource curse, extending the time frame back to the very beginning of oil exploration during the colonial period. It uncovers a previously overlooked causal process by which oil affected the emergence of authoritarianism. It shows that in the case of Brunei (and potentially some Persian Gulf monarchies), sovereignty is endogenous to the resource curse. That is, oil, together with indirect colonial rule, affected the creation of the state, and this state-formation process contributed to the long-standing autocracy. This study contributes to the resource curse literature by identifying a new mechanism of the resource curse, showing that we need to reconsider the way we apply the potential outcomes approach, and highlighting the importance of historical and international factors.

Introduction

When the miracles of Japan and the Four Asian Tigers’ rapid development are discussed, the emphasis is frequently placed on the scarcity of their natural resource endowments. Behind this lies an assumption that abundant natural resources facilitate development. In reality, however, natural resources, especially oil, are associated with various political, economic, and social pathologies. The negative impacts of natural resources are collectively referred to as the “resource curse,” and numerous scholarly works on this subject have been published over the last 20 years. One of the main hypotheses of the resource curse is that oil hinders democracy.Footnote1 While a large number of studies confirm the negative effects of oil on democracy or its positive effects on autocracy,Footnote2 some of the recent works argue that the effects of oil are non-existentFootnote3 or conditional,Footnote4 and scholars have not reached a consensus as to the actual relationship between oil and political regimes.Footnote5

One of the problems of the existing literature is that the causal mechanisms of the resource curse have been relatively understudied.Footnote6 Previous studies have tended to focus on testing the correlation between oil and autocracy through regression analysis, rather than using case studies to trace the causal process connecting the two. As a result, there has not been much discussion on causal mechanisms with only a few exceptions including Ross’ pioneering study.Footnote7 Relatedly, previous studies have also had a tendency to overlook historical and international factors. They often begin their analysis from the 1970s despite the fact that both oil and authoritarian regimes had already existed even before the oil boom. It is important to analyse the entire history of oil development, which requires our attention to the colonial period in which international actors played an important role. To address these issues and contribute to the discussion, this study investigates how oil is relevant to authoritarianism by closely examining the causal process that produced authoritarian rule in Brunei, arguably the most understudied state among the archetypes of the resource curse, by going back to the very beginning of oil production.

In contrast to existing explanations, the analysis finds that the resource curse has colonial origins. The central argument of this article is that sovereignty is endogenous to the resource curse. That is, the state-formation process was affected by oil and it influenced political regimes in turn. Brunei and potentially several other most autocratic oil-rich states became authoritarian not just because their abundant oil wealth enabled the government to repress the opposition and buy people’s support, as previous studies suggest. It was also because oil, together with an indirect colonial administration system, enabled small colonial areas to become sovereign states that would not otherwise exist and to secure strong protection by the colonizers from internal and external threats.

This study offers both substantive and methodological contributions to the resource curse literature. First, it finds a new mechanism of the resource curse, which leads to extreme authoritarianism and exists only in a limited number of countries. Second, it shows that we need to rethink the way we apply the potential outcomes approach, which has been increasingly employed by studies on this topic, because in some cases, states would simply not exist without oil. Third, it highlights the importance of historical and international factors in understanding the causal process of the resource curse more comprehensively.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. The next section reviews relevant literature, identifying what previous research has overlooked. The third section presents the argument of this article, followed by a brief discussion on methodology and case selection in the fourth section. The fifth section is a case study of the political history of Brunei, and the sixth section discusses the applicability of the framework to other cases. Lastly, the seventh section explains the implications of the findings.

Background

Since the oil boom in the 1970s, the politics of natural resources has been a major topic in the field of comparative politics. At the turn of the century, the rentier state theoryFootnote8 was revisited and generalized to establish a new agenda: the “resource curse.” Scholars have argued that oil wealth leads to various pathologies including authoritarianism, civil wars, and slower economic growth.

In the political regime branch of the resource curse, Michael Ross conducted the first cross-national quantitative test of the theory, finding a significant negative correlation between oil and democracy. Many works following Ross’ initial study confirmed the significance of the negative effects of oil on democracy or positive effects on the survival of authoritarian regimes.Footnote9

However, some of the recent studies on this topic have cast serious doubt on the validity of the oil-autocracy link. They pointed out various methodological problems with previous research including omitted variable bias and overdependence on cross-national variation, asserting that if tested with stricter statistical models for causal inference, the resource curse cannot be substantiated.Footnote10 Another type of newer research argues that the resource curse exists but is not universal; it is observed only in countries under particular circumstances. This type of research has attempted to identify “conditions” for the resource curse, assuming the heterogeneity of oil-rich states.Footnote11

As can be seen in the studies reviewed above, the field still remains uncertain about the relationship between oil and democracy. There are increasingly diverse versions of the theory, often contradicting each other. One potential reason for this situation is that the causal mechanisms of the resource curse have been relatively understudied, as Gerring rightly pointed out.Footnote12 Generally, because the debate in the literature has mainly centred on the average causal effects of oil on political regimes, scholars have focused more on testing correlation through statistical analyses than identifying causal mechanisms through case studies.

However, it is important to investigate causal mechanisms especially in the current situation where there are still major disagreements regarding the relationship between oil and democracy. This is because by tracing the process by which oil affects democracy using an actual case, scholars can more closely examine whether and how oil is actually relevant. Considering that a complete explanation must answer not only the “why” question but also the “how” question, paying more attention to the latter can potentially influence the course of the current debate.

What do existing studies tell us about the causal mechanisms of the resource curse? Ross provides arguably the most important insights available so far.Footnote13 He presents three mechanisms of the resource curse. The first is called the “rentier effect,” which refers to the government’s use of its resource rents on patronage and the prevention of the organization of the opposition. The second mechanism is called the “repression effect.” That is, oil revenues enable the government to spend more on internal security and repression. Lastly, he also suggests a “modernization effect,” which means oil revenues hinder the social and cultural changes that normally accompany economic growth.

Dunning’s explanation is another useful reference.Footnote14 He argues that oil wealth has both an authoritarian effect and a democratic effect. It has an immediate authoritarian effect because the elite faces pressure from the poor for redistribution, which contradicts their own preference. However, with abundant oil revenues, redistribution becomes less threatening for the elite, and the cost of democracy decreases, resulting in an indirect democratic effect. The two effects offset each other, and whether a country becomes democratic or not depends on the relative strength of the two.

These explanations provide an excellent starting point for understanding the causal mechanisms of the resource curse. This study supports their argument that oil revenues affect elites’ cost calculations regarding redistributive measures and representative institutions. I argue, however, that existing explanations do not capture the entire picture because historical and international factors are not given sufficient attention here.

When investigating the causal mechanisms of the resource curse, it is important to go back to the very beginning of oil development because that is precisely when the interaction between oil and political regimes started. Existing studies, however, tend to limit the time frame of their analyses to the post-1970s period.Footnote15 This may seem natural considering that the literature originally emerged out of an observation of political turmoil in oil-rich countries during and after the oil boom in the 1970s, but history tells us that many of the most typical examples of the resource curse, such as Qatar or the United Arab Emirates, had been both oil-rich and non-democratic since even before the oil boom. In order to fully account for the relationship between oil and political regimes, we should avoid truncating the process by only looking at recent developments and pay attention to the pre-oil boom history in oil-rich states, which may bring new insights.

If we extend the time frame of the study to the beginning of oil exploration, it becomes impossible to overlook international factors because, with the exception of those in Europe and the Americas, oil-rich countries we see today were colonies, protectorates or other kinds of dependencies when oil was first discovered and developed. During the colonial period, colonizers intervened in the governance of their spheres of influence to varying degrees and the interaction between local and international actors usually shaped the type of governance each colonial area had. Therefore, it is also crucial to incorporate international perspectives in order to reach a more comprehensive understanding of the resource curse.

Resource curse and sovereignty

By incorporating historical and international factors, this article finds that the resource curse has colonial origins. It argues that sovereignty is endogenous to the resource curse in the case of some of the most authoritarian oil-rich states. That is, oil, together with an indirect colonial administration system,Footnote16 affected the state-formation process by creating states that would otherwise not exist and contributed to their long-standing autocracy.

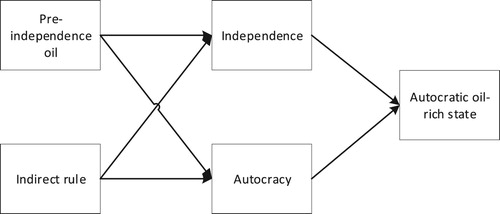

How is the state-formation process relevant to the resource curse? This article uncovers the following causal process (visualized in ) in the Bruneian case. In brief, two factors, namely pre-independence oil and an indirect colonial administration system, contributed to two outcomes, namely separate independence and autocracy.

First, oil and indirect rule provided some colonial areas with reasons to pursue independence separately from neighbouring regions, even though the colonizers normally tried to establish federations amalgamating small neighbouring territories, assuming that they could not survive individually.Footnote17 Oil wealth made the rulers of oil-rich areas unwilling to share their abundant oil revenues with other regions and helped them achieve financial self-sufficiency. It also contributed to their external security, as well as stronger negotiating power vis-à-vis the colonizers during the decolonization process, because the colonizers needed a stable supply of their oil. On the other hand, colonial rule as a separate entity with the rulers at the top of the political hierarchy made them unwilling to give up the status quo and kept the colonizers involved in the protection of the colonial area from external threats. Because of the indirect nature of colonial administration, the rulers had a say over the decolonization outcome of their realms.

Second, the same two factors maintained and reinforced the indigenous autocratic rule. The relationship with the colonizers enhanced the rulers’ political status, for the metropole secured their position and succession. With the start of oil production, their realms became crucially important to the metropole. The rulers’ status became increasingly secure and their rule continued to be protected from both internal and external threats. They could reinforce their own power base by utilizing oil revenues, and even when the colonizers promoted democratization, they could reject it because oil had strengthened their negotiating power vis-à-vis the colonizers.

To become an authoritarian state means two things: that it becomes a state and that it becomes authoritarian. Both are the results of the two factors mentioned above. Previous studies have only discussed the latter, but this article emphasizes the importance of the former.

Methods and case selection

In the following section, I closely investigate the case of Brunei, a microstate on the island of Borneo, to show that oil and the protectorate system contributed to its independence as a sovereign state and the birth of its authoritarianism. This is primarily a theory-building, rather than theory-testing, single case study. Although it briefly discusses other cases, this study does not assume that its framework immediately travels to other cases. The purpose of this research is to uncover a historical causal process of the resource curse that previous studies have failed to find, not to test the applicability of a theory that explains all cases. I agree with Falleti and Lynch’s claim that causal mechanisms differ in different contexts.Footnote18

The method I use here is within-case analysis. I conduct process tracing to identify causal mechanisms by which the cause leads to the outcome.Footnote19 I also employ counterfactual analysis by asking what would have happened had it not been for oil or the protectorate system, to assess the significance of the causal factors.Footnote20

The case of Brunei was chosen for two reasons. First, Brunei is one of the most authoritarian oil-rich states. Focusing on the most typical examples of the theory is a useful way to learn about the mechanisms because if there is a causal relationship, it should be seen most evidently in those cases. As noted above, there have been increasingly diverse versions of the resource curse theory, often contradicting each other. Especially in such a situation, it becomes useful to turn to the “most likely” cases and investigate them in detail to understand the causal process.

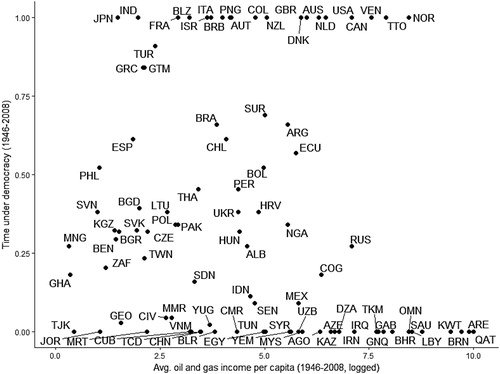

depicts the relationship between average oil and gas income per capita (1946–2008, logged) and the proportion of time under democracy (1946–2008). Brunei is on the bottom-right corner, along with countries like Qatar and the UAE, which means it has received a tremendous amount of oil wealth and has remained extremely autocratic. Although the production itself is not as large compared to major oil-producers, its oil income per capita has been extremely high because of its small population. Since the colonial period, Brunei has been under the rule of the Sultan, whose family has reigned it for several centuries. The Sultan is the head of state and also holds multiple ministerial positions.

Figure 2. Oil and democracy. Note: Data on oil and gas income per capita are from Ross, “Oil and Gas Data, 1932–2014” and data on democracy are from Cheibub et al., “Democracy and Dictatorship Revisited.” Labels in the figure are ISO 3166–1 alpha-3 country codes.

Second, the case of Brunei provides a good illustration of the problem of excluding cases due to their small size or the difficulty to acquire statistical data. Brunei is one of the smallest countries in the world, with only approximately 400,000 people residing in the land as small as 5765 km². It is also one of the countries that do not publish much social, economic, and political data because of their secretive authoritarian regime and limited administrative capacity. Scholars have tended to drop countries with small population intentionally,Footnote21 and those with limited data availability have also been frequently excluded from the sample due to the coverage of the dataset they use. However, as Herb points out, in the case of the resource curse, those small countries that tend not to be very open are the ones that provide the most illustrative examples of the theory.Footnote22 It is important, therefore, to focus on Brunei, which has been largely ignored by the literature despite its extreme rentierism and authoritarianism because the most widely-used datasets on democracy such as the Polity IV and Varieties of Democracy do not cover it. It is likely that studying understudied cases brings new insights, and it would be particularly useful if those new insights also shed new light on other cases that have previously been studied.

Brunei’s road to independence and authoritarianism

Brunei was among numerous sultanates that had existed in the Malay world before the arrival of Western imperialism. It prospered as an entrepôt and became a major power in the region in the sixteenth century, but its power deteriorated after the latter half of the seventeenth century.Footnote23 In the nineteenth century, it allowed a British national (James Brooke) and a British company (the North Borneo Chartered Company) to rule a part of its territory, namely Sarawak and North Borneo, respectively. Since then, the two started to force Brunei to cede its remaining territory. Although Brunei, Sarawak, and North Borneo became separate British protectorates in 1888 (collectively referred to as British Borneo), the British government did not make efforts to stop the invasion.Footnote24 For most British officials, whether Brunei survived or disappeared was not a concern because their interest at that time lay solely in keeping other imperial powers out of the region.Footnote25

However, the discovery of oil in Brunei in 1903, together with the Sultan’s request for the support of Turkey and the United States, led to a change in the British approach to the region, and hence the survival of Brunei.Footnote26 Because oil was becoming increasingly important for the British, as a result of rapid economic development and shifting energy sources,Footnote27 reports of the discovery of oil in Brunei encouraged them to pay more attention to the tiny sultanate. Consequently, a new treaty was signed in 1906. From that point on, the British started to show a stronger position on the integrity of Brunei, and as a result, Bruneian territory was no longer ceded to other regions.Footnote28

This new arrangement also had implications for the internal political order in Brunei. Namely, it reinforced the authority of the Sultan. Although the British practically took control of the administration, all policies by the government were announced under the name of the Sultan, and the British secured the right of succession of the Sultan’s descendants.Footnote29 Brunei, which had previously been politically unstable due to recurring conflicts among factions in the royal family, finally became integrated under the Sultan with the support of the British. The entity of Brunei and the Sultan’s rule remained intact and became increasingly secure after the discovery of a large amount of oil in 1929 at the Seria field.

After World War II, Brunei faced another challenge to its survival as a state and its political regime, but once again, oil and the British protectorate system paved the way for separate independence and long-standing autocracy. With the international trend towards decolonization, the British started planning to let British Borneo achieve independence, but the question was how. In 1961, Malaya’s then prime minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, proposed a potential solution: the Malaysia project. He announced that the three Bornean dependencies were welcome to join the Malayan Federation to create a new federation named Malaysia, and Britain also supported the idea. The Bruneian Sultan, Omar Ali Saifuddin III, initially responded favourably to the plan, but repeated negotiations revealed serious disagreements.

Although there were multiple issues including the Sultan’s status in the federation and the number of federal MPs elected from Brunei,Footnote30 many scholars agree that the most crucial issue was the distribution of Brunei’s oil revenues.Footnote31 Malaya argued that after 10 years since the foundation of Malaysia, the federal government should control the oil fields in Brunei and that resources discovered after the merger would have to be levied immediately. In contrast, the Bruneian government insisted on controlling its natural resources in perpetuity.Footnote32 Becoming a part of a federation meant that Brunei’s oil wealth would have to be distributed to other regions of Malaysia that were poorer than Brunei. Because oil revenues enabled Brunei to stand on its own feet financially, the Sultan did not find it economically necessary to join any federation.Footnote33

Another major reason for Brunei’s decision to go it alone was that the Sultan was confident that the British would continue to protect Brunei even if Brunei did not join Malaysia. The event that made him believe so was the Brunei Revolt in December 1962. The Brunei People’s Party (Parti Rakyat Brunei: PRB), founded by A. M. Azahari in 1956, had become increasingly popular in the 1950s and early 1960s. It disagreed with the Sultan’s policies on decolonization while demanding him of implementing a democratic election and establishing an elected government so that it can come to power. Although the PRB won in a landslide in the District Council elections in 1962, it was unable to influence the policy of the central government due to the Sultan’s refusal to cooperate with it. As a result, it eventually resorted to a violent uprising to overturn the existing regime. Although the PRB swiftly seized most of the country, with British regiments immediately sent to Brunei, the revolt was suppressed in two weeks, and the PRB was outlawed.Footnote34 This incident convinced the Sultan that Britain would continue to provide his country with security, removing an obstacle to its continued existence as a separate entity.Footnote35 Consequently, Brunei chose not to become part of the new federation.

The suppression of the Brunei Revolt also had profound implications for the political regime in the sultanate. After the PRB, the most powerful pro-democracy organization, was defeated by force with the help of the British, there was no longer any strong internal political movement pushing for the introduction of democracy.Footnote36 Emergency regulations were introduced and renewed repeatedly, and the government tightened its control over the society, while utilizing oil revenues to obtain people’s support. It can be said that Britain greatly helped the Sultan to maintain his autocratic rule.Footnote37 Brunei became a depoliticized society.

Even after Brunei announced that it would not be part of Malaysia, the British still exerted pressure on Brunei both to join Malaysia and to introduce democracy.Footnote38 However, Brunei’s oil and its status as a protectorate enabled the Bruneian government to refuse British requests. After the Wilson Labour government came to power in 1964, Britain became increasingly eager to withdraw its troops from and promote democracy to Brunei.Footnote39 However, the Sultan was still not free from concerns about the security of Brunei and he never had the intention to give up his status as an absolute monarch. Therefore, he resisted the withdrawal and political reforms by abdicating in favour of his son and threatening to transfer his fortune, which was deposited in a British bank.Footnote40 Because the Sultan’s money, which came from oil revenues, was important for the British economy and Brunei Shell supported the Sultan, the British eventually agreed to continue offering security to Brunei.Footnote41 In addition, the British could not force the Sultan to join Malaysia or introduce democracy because Brunei, as a British protectorate, had sovereignty, although limited, and they could not take “the risk of being accused of bullying a sovereign ruler.”Footnote42

Consequently, it was as late as 1984 that Brunei became fully independent, when the Sultan was finally convinced that all foreign and internal threats had already been cleared. He even managed to keep British Gurkha regiments stationed in Brunei, which is still the key to Brunei’s security.Footnote43 With regard to democracy, Britain had no choice but to stop demanding it and gave Brunei full internal sovereignty in 1971, leaving all internal authorities to the Sultan’s hands.Footnote44

The independence of Brunei meant the birth of a country under an absolute monarchy. Brunei presents a typical example of a rentier state through both patronage and coercion. It is “the only ASEAN country without general elections, an organized opposition, or an independent civil society.”Footnote45 The current Sultan, Hassanal Bolkiah, holds four ministerial offices (Prime Minister, Minister of Finance and Economy, Minister of Defence, and Minister of Foreign Affairs) and is the commander of the army and police. There has been no elected parliament, and although a number of parties have existed, political opposition has remained extremely weak ever since the defeat of the PRB.Footnote46

The Sultan has not only relied on coercion to maintain his rule; he has also utilized the country’s wealth to gain people’s support. Brunei has had extremely generous social welfare programmes, ranging from free education and healthcare to no obligation to pay income tax. The state is the largest employer of its people, giving a job to 25% of the total population. The Bruneian state has been called a “Shellfare” state, for the financial source of those programmes is its oil and gas developed by Brunei Shell Petroleum.Footnote47

What does the Bruneian case tell us about the causal process leading to the resource curse? First, oil contributed to Brunei’s separate independence and the authoritarian rule of the Sultan. If oil had not been discovered in 1903, the British would probably have let Sarawak and North Borneo annex Brunei. Even if Brunei had been preserved this time for other reasons, there could not have been any financial issues between Brunei and Malaya if it had not been for oil in Brunei. Rather, Brunei would have been the one that would economically benefit from the merger. Likewise, oil was the factor that gave the Sultan leverage to extract more support from Britain for securing succession, suppressing the opposition, and protecting the country from external threats. Without oil, the British would not have found a compelling reason to protect Brunei from neighbours or support the Sultan in internal conflicts, which would have led to the weaker internal political foundation of the Sultan.

Second, in addition to oil, indirect colonial administration as a British protectorate also contributed to the separate independence of the sultanate and the empowerment of the indigenous autocratic rule. If Brunei had been governed in a more direct way, there would be no reason to believe that the Sultan would have had a say over the decolonization policy. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that Brunei would have smoothly followed the British proposal to merge with the neighbouring regions and would eventually have become part of Malaysia. Likewise, the Sultan would have lost any political power and would not have had a way to stop the rise of nationalist political groups such as the PRB had it not been for the British support. British direct colonial administration would have let political parties sympathetic to Britain govern the country, just like in the case of Malaya, resulting in the absence of an absolute monarchy.

These points become clearer when one compares Brunei with its neighbouring colonial areas, namely Sarawak and Dutch Kalimantan. Sarawak was part of Brunei until James Brooke, a British citizen, was appointed as Sarawak’s Rajah in 1842 by the Bruneian Sultan because of his help in suppressing a revolt. It became practically independent of Brunei and became a British protectorate in 1888. It had the same colonial status as Brunei until the end of the Second World War as a British protectorate. However, it differed significantly from Brunei in its financial situation, which eventually led to the absence of separate independence and extreme authoritarianism. Dutch Kalimantan was the southern half of the island of Borneo under the Dutch rule. It has been oil-rich just like Brunei since the late nineteenth century, which means that it was not much different from Brunei in terms of the material incentive to achieve independence. However, they differed markedly in the type of colonial administration after the discovery of oil, which resulted in different outcomes as to decolonization and political regimes.

In Sarawak, when the Japanese occupation during the Second World War ended, the Brookes were financially incapable of reconstructing the devastated lands.Footnote48 The reason why Sarawak did not have enough financial resources was that it was much less rich in natural resources than originally expected at the time of colonization.Footnote49 Oil was found at the Miri field in 1910, but the amount the field could produce was very small compared with Brunei’s Seria field.Footnote50 As a result, Sarawak was by no means financially viable as a sovereign state and had no material incentive to pursue separate independence. It had to depend on other regions to achieve economic development, and Malaya was virtually the only possibility. Because Malaya was willing to offer the necessary assistance, Sarawak had no choice but to join Malaysia.Footnote51

Because of the lack of financial resources, the Brookes could not even sustain their rule over their territory; Sarawak was transferred from a protectorate to a Crown colony in 1946. Since then, the British administered the area directly, and the Brookes left the political arena. Political parties such as the Sarawak United Peoples’ Party (SUPP) and the National Party of Sarawak (PANAS) were established and became central indigenous political actors in Sarawak.

In the Dutch East Indies, including the island of Borneo (also known as Kalimantan), a number of sultanates enjoyed de facto autonomy until the 1870s. When the Dutch realized the economic potential of the outer islands, however, they ended the non-interference policy and started to actively intervene in the local administration.Footnote52 The main motivation behind this change was the newly-discovered natural resources.Footnote53 In Dutch Kalimantan, oil was discovered within the realm of Kutai and Bulungan sultanates at the turn of the century.Footnote54 Once oil was discovered, the Dutch started to deprive the sultans of their authority and place their realms under the effective direct control of the colonial government, whose headquarters was in Batavia on the island of Java.Footnote55 Dutch Kalimantan started to be administered merely as part of the Dutch East Indies, not as separate sultanates, and the rulers lost political power. The colonizers took control of the oil fields so that they could freely exploit the oil revenues.Footnote56

As a result, political movements in Dutch Kalimantan became part of those in the Dutch East Indies as a whole. Anti-colonial movements centred in Java spread to Kalimantan, establishing branches of nation-wide political parties in 1933.Footnote57 Nationalism in Kalimantan was not nationalism of sultanates such as Kutai or Bulungan, but that of the Dutch East Indies. Kalimantan eventually experienced decolonization as part of Indonesia in 1950.

Malaysia and Indonesia, the new sovereign states that include former Sarawak and Dutch Kalimantan, respectively, did not experience the same historical path as Brunei and did not become as authoritarian. Unlike Brunei, they did not become independent as a sovereign state because of oil; they included multiple colonial units with different historical background. Malaysia is an amalgam of multiple colonial areas from which Brunei opted out, and Indonesia succeeded the Dutch East Indies, which included numerous former sultanates. In those larger entities, there was no indigenous ruler to govern the entire nation, and therefore oil did not empower any particular local ruler during the initial state-formation process like it did in Brunei. Although the British supported indigenous rulers in Malaya during the colonial period, the rulers did not have financial resources or British support to seize full control of political power, eventually giving way to nationalists, who relied on party politics to take control of the country.Footnote58 In Indonesia, indigenous rulers had already lost their political power during the colonial period due to the centralization of Dutch colonial administration.Footnote59 Upon decolonization, which was achieved through a conflict with the colonizers, the national political leaders did not have a monopoly of power and had to form a pact with each other.Footnote60

To summarize, the key point in understanding the origins of authoritarianism in Brunei is its history between colonization and decolonization. As mentioned above, the statement that Brunei became an authoritarian state has two components: that Brunei became a state, and that it became authoritarian. It is true that Bruneian internal politics since its independence has been a typical example of the rentier state and resource curse theories, but it is not the entire picture. Brunei is a country that would not exist had it not been for oil and an indirect colonial administration system. Had it not become independent as a sovereign state, we would not see an authoritarian Brunei today. This study shows that the two components above are causally relevant to each other, both being affected by oil, which means that sovereignty is endogenous to the resource curse.

Generalizability of the Bruneian case

Does the framework induced from the case study of Brunei apply to other cases? As this article is essentially a theory-building paper, a complete test of the argument is outside of its scope. However, it is useful to consider whether the same framework can also explain other cases.

I suggest that the historical path explained in this article can be applied not only to Brunei but also to a number of Persian Gulf states. Gulf sheikhdoms enjoyed a treaty relationship with Britain, which offered protection and political authority to the local rulers.Footnote61 The region was important for the British in terms of the access to India, “the crown jewel” of the British Empire, but the development of the region itself was initially out of their concern, so indirect rule was the optimal choice for them.Footnote62 After oil was discovered in many parts of the region in the interwar period, however, the British became more committed to the security and the internal stability of the sheikhdoms. They started to actively deter expansionist regional powers and intervene in internal political conflicts in favour of the rulers.Footnote63

The very existence of many Persian Gulf states owes much to their oil and the British protectorate system to different degrees. The separate independence of Qatar and Bahrain is a good example. The two sheikhdoms originally planned to join the UAE, which was established in 1971 merging seven separate entities, but eventually opted out from the project and achieved independence individually. The reasons for their separate independence were very similar to those for Brunei’s.Footnote64 They were among the first colonial areas in the region to develop and benefit from oil, which gave them an incentive to achieve independence separately. Treaty relations with Britain freed them from territorial ambitions of neighbouring powers, and also cleared internal threats. More generally, as Zahlan points out, it owes much to oil and British protection that smaller Persian Gulf states, including not only the above two but also Kuwait, the UAE, and Oman, managed to survive as separate entities, not being annexed by stronger states such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Iraq.Footnote65

Oil and British protection also led to extreme authoritarianism that is prevalent in the region. Britain often interfered in domestic affairs of the Persian Gulf states, supporting pro-British rulers, and reinforced their domestic authority.Footnote66 This was because Britain had crucial interests in oil in the Persian Gulf. The stability of friendly oil producers was extremely important to Britain and its allies.Footnote67 Oil revenues and British support thus strengthened the political power of the rulers, empowering the authoritarian regime.

Implications

This article has revealed that the resource curse has colonial origins and sovereignty is endogenous to the resource curse. Oil, together with an indirect colonial administration system, enabled some colonial areas to become sovereign states that would not otherwise exist and also contributed to their long-standing autocracy. This study has three kinds of implications for the resource curse theory.

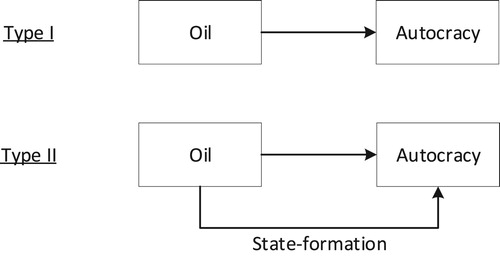

First, it suggests that there are two different, although related, causal mechanisms of the resource curse (). One is a direct link between oil and autocracy, and the other is an indirect link through state-formation. The former enables existing regimes to live longer, which existing studies have already discussed, while the latter gives birth to authoritarian regimes, which I described here. The latter seems to exist only in a small number of countries that I mentioned in this article, namely Brunei and potentially the Persian Gulf states, while the former is more common.

This suggests that the causal mechanism by which oil hinders democracy is not homogeneous. It is erroneous to assume that all oil-rich states are directly comparable or that we can understand the politics of natural resources in all oil producers with a “one-size-fits-all” theory.Footnote68 There are reasons to believe that some countries (“Type II” countries in ) are exceptionally authoritarian because they experienced a distinct causal mechanism that does not exist in other oil-rich states (“Type I” countries in ).

Second, this article points out that we need to rethink the way we apply the potential outcomes approach in the study of the resource curse, which has been increasingly employed by studies on this topic. In the context of the resource curse, this approach defines the effects of oil on democracy as the difference between the level of democracy in a given country with and without oil, one of which is a counterfactual.Footnote69

However, this study finds that this is not always the best way to identify the effects of oil on democracy. At least in the case of Brunei and potentially some Gulf states, it is hardly possible to consider a counterfactual of these countries without oil because their very existence as a sovereign state owes much to the existence of oil. In these cases, we need to consider what the area would look like without these countries. The adequate counterfactual for Brunei is a Malaysian region of “Brunei” without oil, not Brunei without oil.

Third, and most importantly, this article highlights the importance of historical and international factors in the discussion of the resource curse, which have been and are increasingly overlooked in the literature. This article demonstrated that oil has been enabling rulers to remain in power since even before the “big oil change”Footnote70 through colonial political relations. In the cases mentioned in this article, the resource curse is thus a very long-term historical process that often dates back to the colonial period.

Conclusion

Although the resource curse literature has seen a significant development over the past two decades, it has not yet reached a consensus as to whether and how exactly oil affects political regimes. There have been increasingly diverse versions of the theory, often contradicting each other.

To contribute to a better understanding of the relationship between oil and political regimes, this study conducted a detailed case study of the political history of Brunei and revealed that oil, together with an indirect colonial administration system, enabled the tiny sultanate to achieve independence separately from neighbouring regions and maintained and reinforced its authoritarian internal rule. This shows that the resource curse has colonial origins and that sovereignty is endogenous to the resource curse. The endogeneity of sovereignty to the resource curse cannot be overlooked, and incorporating the findings discussed here would advance the theory of the resource curse even further.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this article was presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association (September 2018, Boston) and Nuffield DPhil Politics/IR Seminar (November 2018, Oxford), where it received insightful feedback from Benjamin Smith and Ben Ansell, respectively. I would like to thank the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Suntory Foundation for research funding, and Ricardo Soares de Oliveira and Kiichi Fujiwara for their excellent feedback on early drafts of this article. I am also grateful to Ezequiel Gonzalez Ocantos, Yuko Kasuya, Reo Matsuzaki, Kenneth McElwain, Shun Watanabe, and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Naosuke Mukoyama http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3069-0121

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Naosuke Mukoyama

Naosuke Mukoyama is a DPhil Candidate at the Department of Politics and International Relations of the University of Oxford (St. Antony’s College).

Notes

1 Ross, “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?”

2 Andersen and Aslaksen, “Oil and Political Survival”; Aslaksen, “Oil and Democracy”; Jensen and Wantchekon, “Resource Wealth and Political Regimes in Africa”; Ross, The Oil Curse; Smith, “Oil Wealth and Regime Survival”; Ulfelder, “Natural-Resource Wealth and the Survival of Autocracy”; Wright, Frantz, and Geddes, “Oil and Autocratic Regime Survival.” As is the case with most researchers on this topic, I discuss whether a regime is democratic or autocratic rather than different types of authoritarianism, focusing particularly on the legal and institutional aspects.

3 Haber and Menaldo, “Do Natural Resources Fuel Authoritarianism?”; Liou and Musgrave, “Refining the Oil Curse.”

4 Dunning, Crude Democracy; Houle, “A Two-step Theory”; Luong and Weinthal, “Rethinking the Resource Curse”; Smith, Hard Times in the Lands of Plenty; Tsui, “More Oil, Less Democracy.”

5 For a review of recent developments in the field, see Morrison, “Whither the Resource Curse?”

6 Gerring, “Causal Mechanisms.”

7 Ross, “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?”

8 Beblawi and Luciani, The Rentier State; Mahdavy, “The Patterns and Problems.”

9 See note 2.

10 See note 3.

11 See note 4.

12 Gerring, “Causal Mechanisms.” See also Sandbakken, “The Limits to Democracy.”

13 Ross, “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?”

14 Dunning, Crude Democracy.

15 A notable exception is Mitchell, Carbon Democracy.

16 In this article, I use “indirect rule”, “indirect colonial administration system”, and “protectorate system” interchangeably to refer to a type of colonial administration system built on the pre-existing local political order, with the local ruler at the top of the political structure. For the distinction between direct rule and indirect rule, see Cell, “Colonial Rule.”

17 McIntyre, British Decolonization, 1946-1997.

18 Falleti and Lynch, “Context and Causal Mechanisms.”

19 Bennett and Checkel, Process Tracing; Collier, “Understanding Process Tracing”; George and Bennett, Case Studies and Theory Development.

20 Levy, “Counterfactuals and Case Studies”; Tetlock and Belkin, Counterfactual Thought Experiments.

21 For example, Ross, “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?” excludes countries with populations smaller than 100,000, while Smith, “Resource Wealth as Rent Leverage” drops those with less than 500,000. Brunei can be covered by the first, although it can be dropped for other reasons, while it cannot be covered in the latter.

22 Herb, “No Representation without Taxation?,” 305.

23 For Bruneian history before the arrival of the British, see Al-Sufri, Brunei Darussalam; de Vienne, Brunei; Saunders, A History of Brunei.

24 Ranjit Singh, Brunei, 1839-1983, Chapter 3.

25 Hussainmiya, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III and Britain, 14.

26 Although it was not until 1929 that commercial quantities of oil were found in the Seria field, oil exploration started in 1899 and Brunei’s potential for oil production was confirmed when oil was found in 1903 in Berambang Island. Sidhu, Historical Dictionary, 237.

27 The British Navy shifted its energy source from coal to oil in the 1910s under Winston Churchill’s initiative. For the history of the oil industry, see Mitchell, Carbon Democracy; Yergin, The Prize.

28 Ranjit Singh, Brunei, 1839-1983, 95–8; Sidhu, Historical Dictionary, 18.

29 Hussainmiya, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III and Britain, 24–6; Saunders, A History of Brunei, 111.

30 For the details of the negotiation, see Melayong, The Catalyst Towards Victory, 139–69; Suzuki, “Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III,” 68–70.

31 Al-Sufri, Brunei Darussalam, 162–6; Cleary and Wong, Oil, Economic Development, and Diversification, 28; Hamza, The Oil Sultanate, 99; Hussainmiya, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III and Britain, 320; Melayong, The Catalyst Towards Victory, 139, 165; Ranjit Singh, Brunei, 1839-1983, 183–90; Saunders, A History of Brunei, 154; Stockwell, “Britain and Brunei, 1945-1963,” 812.

32 For details of the disagreement, see Saunders, A History of Brunei, 144–54.

33 In addition, the discovery of a new oil field in Southwest Ampa was reported in 1963 by Brunei Shell. Hamzah argues that this affected the Sultan’s decision. Hamzah, “Oil and Independence in Brunei,” 93–9.

34 Melayong, The Catalyst Towards Victory, 91–136; Ranjit Singh, Brunei, 1839-1983, 150–76.

35 Hussainmiya, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III and Britain, 323, 334–5; Melayong, The Catalyst Towards Victory, 221; Stockwell, “Britain and Brunei, 1945-1963,” 815. Indonesia’s confrontation policy in the subsequent years also contributed to the continued protection of Brunei by the British. Objecting to the establishment of Malaysia, the Indonesian government declared the start of a confrontation policy on 20 January 1963, and Malaysia severed relations with Indonesia immediately after its foundation. An undeclared armed conflict erupted in northern Borneo, and because it was an imminent threat posed by a pro-communist regime to a good friend of the West, the British had to help defend the front area, which included Brunei, rather than withdrawing from the region as it had previously planned. See Jones, Conflict and Confrontation.

36 Hussainmiya, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III and Britain, 312; Melayong, The Catalyst Towards Victory, 175.

37 See Talib, “Brunei Darussalam” further on this point.

38 Melayong, The Catalyst Towards Victory, 231.

39 Hussainmiya, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III and Britain, 348

40 Cleary and Wong, Oil, Economic Development, and Diversification, 31; Suzuki, “Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III,” 74.

41 Hamzah, “Oil and Independence in Brunei.”

42 Stockwell, “Britain and Brunei, 1945-1963,” 791, 794.

43 Kershaw, Partners in Realism, 48.

44 Hussainmiya, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III and Britain, 375.

45 Müller, “Brunei Darussalam in 2016,” 199. For democratic development in Asia, see Croissant, “From transition to defective democracy.”

46 Case, “Brunei in 2006.”

47 Cheung, “Rentier Welfare States.”

48 Ooi, Post-War Borneo, 1945-1950, 84.

49 Ooi, Of Free Trade and Native Interests, 120.

50 Kaur, “The Babbling Brookes,” 80–2. Kaur, “Economic Change in East Malaysia,” 130.

51 Tamura, “Malaysia Rempo ni okeru Kokka Touitsu,” 14.

52 Lindblad, “Economic Aspects of the Dutch Expansion,” 5–7.

53 Lindblad, Between Dayak and Dutch, 123.

54 Lindblad, “The Petroleum Industry in Indonesia,” 53.

55 Magenda, East Kalimantan, 13–25.

56 All oil revenues of the archipelago were sent to Batavia first, and then distributed to each area by the colonial government. See Lindblad, Between Dayak and Dutch, 152.

57 Lindblad, Between Dayak and Dutch, 136.

58 Smith, “The Rise, Decline and Survival”; Smith, “‘Moving a Little with the Tide.’”

59 Lindblad, “Economic Aspects of the Dutch Expansion”; Magenda, East Kalimantan.

60 Slater, Ordering Power.

61 Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf, 17.

62 Onley, The Arabian frontier.

63 Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf, 51, 116; Macris, The Politics and Security of the Gulf, 27; Zahlan, The Making of the Modern Gulf States, 21.

64 For detailed accounts of the negotiation process of the formation of the United Arab Emirates, see Heard-Bey, From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates; Sato, Britain and the Formation of the Gulf States; Smith, Britain’s Revival and Fall in the Gulf.

65 Zahlan, The Making of the Modern Gulf States, Chapter 2.

66 Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf.

67 Macris, The Politics and Security of the Gulf, 33.

68 In statistical analyses, researchers may benefit from adopting a sample-selection procedure. I thank anonymous reviewer 1 for raising this point.

69 Herb, “No Representation without Taxation?”; Liou and Musgrave, “Refining the Oil Curse.”

70 Andersen and Ross, “The Big Oil Change.”

Bibliography

- Al-Sufri, Mohd. Jamil. Brunei Darussalam: The Road to Independence. Translated by Mohd. Amin Hassan. Bandar Seri Begawan: Brunei History Centre, Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports, 1998.

- Andersen, Jørgen J., and Michael L. Ross. “The Big Oil Change: A Closer Look at the Haber-Menaldo Analysis.” Comparative Political Studies 47, no. 7 (2014): 993–1021. doi: 10.1177/0010414013488557

- Andersen, Jørgen Juel, and Silje Aslaksen. “Oil and Political Survival.” Journal of Development Economics 100, no. 1 (2013): 89–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2012.08.008

- Aslaksen, Silje. “Oil and Democracy: More than a Cross-Country Correlation?” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 4 (2010): 421–431. doi: 10.1177/0022343310368348

- Beblawi, Hazem, and Giacomo Luciani. The Rentier State. London: Croom Helm, 1987.

- Bennett, Andrew, and Jeffrey T Checkel. Process Tracing: From Metaphor to Analytic Tool. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Case, William. “Brunei in 2006: Not a Bad Year.” Asian Survey 47, no. 1 (2007): 189–193. doi: 10.1525/as.2007.47.1.189

- Cell, John W. “Colonial Rule.” In The Oxford History of the British Empire. Volume 4, The Twentieth Century, edited by Judith M. Brown, and William Roger Louis, 232–253. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Cheibub, José Antonio, Jennifer Gandhi, and James Raymond Vreeland. “Democracy and Dictatorship Revisited.” Public Choice 143, no. 2-1 (2010): 67–101. doi: 10.1007/s11127-009-9491-2

- Cheung, Johnson Chun-Sing. “Rentier Welfare States in Hydrocarbon-Based Economies: Brunei Darussalam and Islamic Republic of Iran in Comparative Context.” Journal of Asian Public Policy 10, no. 3 (2017): 287–301. doi: 10.1080/17516234.2015.1130468

- Cleary, Mark, and Shuang Yann Wong. Oil, Economic Development and Diversification in Brunei Darussalam. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1994.

- Collier, David. “Understanding Process Tracing.” PS: Political Science & Politics 44, no. 04 (2011): 823–830.

- Croissant, Aurel. “From Transition to Defective Democracy: Mapping Asian Democratization.” Democratization 11, no. 5 (2004): 156–178. doi: 10.1080/13510340412331304633

- Crystal, Jill. Oil and Politics in the Gulf : Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar. Cambridge Middle East Library; 24. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Dunning, Thad. Crude Democracy: Natural Resource Wealth and Political Regimes. Vol. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Falleti, Tulia G, and Julia F Lynch. “Context and Causal Mechanisms in Political Analysis.” Comparative Political Studies 42, no. 9 (2009): 1143–1166. doi: 10.1177/0010414009331724

- George, Alexander L, and Andrew Bennett. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005.

- Gerring, John. “Causal Mechanisms: Yes, But … .” Comparative Political Studies 43, no. 11 (2010): 1499–1526. doi: 10.1177/0010414010376911

- Haber, Stephen, and Victor Menaldo. “Do Natural Resources Fuel Authoritarianism? A Reappraisal of the Resource Curse.” American Political Science Review 105, no. 1 (2011): 1–26. doi: 10.1017/S0003055410000584

- Hamzah, B. A. “Oil And Independence In Brunei: A Perspective.” Southeast Asian Affairs 8 (1981): 93–99. doi: 10.1355/SEAA81G

- Hamzah, B. A. The Oil Sultanate: Political History of Oil in Brunei Darussalam. Seremban, Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia: Mawaddah Enterprise, 1991.

- Heard-Bey, Frauke. From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates: A Society in Transition. London: Motivate, 2005.

- Herb, Michael. “No Representation without Taxation? Rents, Development, and Democracy.” Comparative Politics 37, no. 3 (2005): 297–316. doi: 10.2307/20072891

- Houle, Christian. “A Two-Step Theory and Test of the Oil Curse: The Conditional Effect of Oil on Democratization.” Democratization 25, no. 3 (2018): 404–421. doi: 10.1080/13510347.2017.1366449

- Hussainmiya, B. A. Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III and Britain : The Making of Brunei Darussalam. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Jensen, Nathan, and Leonard Wantchekon. “Resource Wealth and Political Regimes in Africa.” Comparative Political Studies 37, no. 7 (2004): 816–841. doi: 10.1177/0010414004266867

- Jones, Matthew. Conflict and Confrontation in South East Asia, 1961-1965: Britain, the United States and the Creation of Malaysia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Kaur, Amarjit. “The Babbling Brookes: Economic Change in Sarawak 1841–1941.” Modern Asian Studies 29, no. 1 (1995): 65–109. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X00012634

- Kaur, Amarjit. Economic Change in East Malaysia: Sabah and Sarawak Since 1850. Studies in the Economies of East and South-East Asia. Oxford: Macmillan, 1998.

- Kershaw, Roger. “Partners in Realism: Britain and Brunei Amid Recent Turbulence.” Asian Affairs 34, no. 1 (2003): 46–53. doi: 10.1080/0306837032000054270

- Levy, Jack S. “Counterfactuals and Case Studies.” In The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology, edited by Janet M. Box-Steffensmeier, Henry E. Brady, and David Collier, 627–644. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Lindblad, J Thomas. Between Dayak and Dutch: The Economic History of Southeast Kalimantan 1880-1942. Dordrecht: Foris, 1988.

- Lindblad, J Thomas. “Economic Aspects of the Dutch Expansion in Indonesia, 1870-1914.” Modern Asian Studies 23 (1989): 1–24. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X00011392

- Lindblad, J Thomas. “The Petroleum Industry in Indonesia before the Second World War.” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 25, no. 2 (1989): 53–77. doi: 10.1080/00074918812331335569

- Liou, Yu-Ming, and Paul Musgrave. “Refining the Oil Curse: Country-Level Evidence From Exogenous Variations in Resource Income.” Comparative Political Studies 47, no. 11 (2014): 1584–1610. doi: 10.1177/0010414013512607

- Luong, Pauline Jones, and Erika Weinthal. “Rethinking the Resource Curse: Ownership Structure, Institutional Capacity, and Domestic Constraints.” Annual Review of Political Science 9 (2006): 241–263. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.062404.170436

- Macris, Jeffrey R. The Politics and Security of the Gulf: Anglo-American Hegemony and the Shaping of a Region. London: Routledge, 2010.

- Magenda, Burhan. East Kalimantan: The Decline of a Commercial Aristocracy. Ithaca: Cornell Modern Indonesia Project, Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University, 1991.

- Mahdavy, H. “The Patterns and Problems of Economic Development in Rentier States: The Case of Iran.” In Studies in Economic History of the Middle East, edited by M. A. Cook, 428–467. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- McIntyre, William David. British Decolonization, 1946-1997: When, Why and How Did the British Empire Fall? Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998.

- Melayong, Muhammad Hadi bin Muhammad. The Catalyst towards Victory. Bandar Seri Begawan: Brunei History Centre, Ministry of Culture, Youth and Sports, 2010.

- Mitchell, Timothy. Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil. London: Verso Books, 2011.

- Morrison, Kevin M. “Whither the Resource Curse?” Perspectives on Politics 11, no. 4 (2013): 1117–1125. doi: 10.1017/S1537592713002855

- Müller, Dominik M. “Brunei Darussalam in 2016: The Sultan Is Not Amused.” Asian Survey 57, no. 1 (2017): 199–205. doi: 10.1525/as.2017.57.1.199

- Onley, James. Arabian Frontier of the British Raj: Merchants, Rulers and the British in the Nineteenth-Century Gulf. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Ooi, Keat Gin. Of Free Trade and Native Interests : The Brookes and the Economic Development of Sarawak, 1841-1941. South-East Asian Historical Monographs. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Ooi, Keat Gin. Post-War Borneo, 1945-1950 : Nationalism, Empire, and State-Building. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Ranjit Singh, D. S. Brunei, 1839-1983: The Problems of Political Survival. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984.

- Ross, Michael L. “Does Oil Hinder Democracy?” World Politics 53, no. 3 (2001): 325–361. doi: 10.1353/wp.2001.0011

- Ross, Michael L. The Oil Curse: How Petroleum Wealth Shapes the Development of Nations. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- Ross, Michael L. “Oil and Gas Data, 1932-2014.” Harvard Dataverse (2015). doi:10.7910/DVN/ZTPW0Y.

- Sandbakken, Camilla. “The Limits to Democracy Posed by Oil Rentier States: The Cases of Algeria, Nigeria and Libya.” Democratization 13, no. 1 (2006): 135–152. doi: 10.1080/13510340500378464

- Sato, Shohei. Britain and the Formation of the Gulf States: Embers of Empire. University Press Scholarship Online. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016.

- Saunders, Graham. A History of Brunei. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Sidhu, Jatswan. S. Historical Dictionary of Brunei Darussalam. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2016.

- Slater, Dan. Ordering Power: Contentious Politics and Authoritarian Leviathans in Southeast Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Smith, Benjamin B. Hard Times in the Lands of Plenty: Oil Politics in Iran and Indonesia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007.

- Smith, Benjamin B. “Oil Wealth and Regime Survival in the Developing World, 1960-1999.” American Journal of Political Science 48, no. 2 (2004): 232–246. doi: 10.1111/j.0092-5853.2004.00067.x

- Smith, Benjamin B. “Resource Wealth as Rent Leverage: Rethinking the Oil–Stability Nexus.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 34, no. 6 (2017): 597–617. doi: 10.1177/0738894215609000

- Smith, Simon C. Britain’s Revival and Fall in the Gulf: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the Trucial States, 1950-71. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004.

- Smith, Simon C. “‘Moving a Little with the Tide’: Malay Monarchy and the Development of Modern Malay Nationalism.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 34, no. 1 (2006): 123–138. doi: 10.1080/03086530500412165

- Smith, Simon C. “The Rise, Decline and Survival of the Malay Rulers during the Colonial Period, 1874–1957.” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 22, no. 1 (1994): 84–108. doi: 10.1080/03086539408582921

- Stockwell, A. “Britain and Brunei, 1945-1963: Imperial Retreat and Royal Ascendancy.” Modern Asian Studies 38 (2004): 785–819. doi: 10.1017/S0026749X04001271

- Suzuki, Yoichi. “Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin III to Shinrempo Kousou: Brunei No Malaysia Hennyu Mondai, 1959-1963.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 89 (2015): 47–78.

- Talib, Naimah S. “Brunei Darussalam: Royal Absolutism and the Modern State.” Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia 13 (2013). https://kyotoreview.org/issue-13/brunei-darussalam-royal-absolutism-and-the-modern-state/.

- Tamura, Keiko. “Malaysia Rempo ni okeru Kokka Touitsu.” Ajia Kenkyu 35, no. 1 (1988): 1–44.

- Tetlock, Philip E, and Aaron Belkin. Counterfactual Thought Experiments in World Politics: Logical, Methodological, and Psychological Perspectives. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Tsui, Kevin K. “More Oil, Less Democracy: Evidence from Worldwide Crude Oil Discoveries.” The Economic Journal 121, no. 551 (2011): 89–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02327.x

- Ulfelder, Jay. “Natural-Resource Wealth and the Survival of Autocracy.” Comparative Political Studies 40, no. 8 (2007): 995–1018. doi: 10.1177/0010414006287238

- de Vienne, Marie-Sybille. Brunei: From the Age of Commerce to the 21st Century. Translated by Emilia Lanier. Singapore: NUS Press, 2015.

- Wright, Joseph, Erica Frantz, and Barbara Geddes. “Oil and Autocratic Regime Survival.” British Journal of Political Science 45, no. 2 (2015): 287–306. doi: 10.1017/S0007123413000252

- Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991.

- Zahlan, Rosemarie Said. The Making of the Modern Gulf States: Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates and Oman. Reading: Ithaca Press, 1998.