ABSTRACT

Referendums figure prominently in discussions about democracy and democratic innovation. Whereas much of the literature is focused on binary versions of the referendum, this article centralizes the non-binary or multi-option referendum, paying special attention to its modalities and the leverage they give to citizens in the ballot agenda-setting stage. Studying agenda-setting in multi-option referendums contributes to our understanding of civic democratic empowerment. For this purpose, we distil from practical experience the process steps and actors involved in triggering multi-option referendums and formulating ballot options. We map them in six main models of agenda-setting processes, three of which are legally institutionalized and triggered through bottom-up processes, allowing for competing proposals by citizens and legislators; three other models are characterized by top-down, ad hoc triggering and entail variation in the involvement of political parties, experts, societal groups and citizens in suggesting or selecting ballot options. Our procedural typology ultimately contributes to the body of research on referendum triggering and option formulation in the context of democratic innovation.

1. Introduction

Referendums figure prominently in discussions about democracy and democratic innovation. Feared by some as a threat to modern representative democracy, the referendum is hailed by others for taking democracy closer to its core essence by giving kratos to the demos.Footnote1 Whereas much of the literature is focused on binary referendum formats, presenting the voter with basically two competing options, this article centralizes the non-binary or multi-option referendum, paying special attention to its modalities and leverage provided to the demos in the ballot agenda-setting stage. Referendums can democratically empower citizens not only in voting on a pre-defined ballot proposal but also in formulating and pushing proposals in the preceding stage. Control over the topic and alternatives submitted to a vote provides new democratic possibilities, within constraints, which we conceptually and empirically explore in this article.

1.1. Multi-option referendums

Tierney recognizes three main objections to referendums: they can be prone to elite control and manipulation; tend to aggregate pre-formed opinions over encouraging meaningful deliberation; and consolidate majoritarian decision making at the expense of individual and minority interests.Footnote2 In particular theories of deliberative and consensual democracy tend to be critical or at least hesitant about the referendum, especially the common binary format.Footnote3 Discussions surrounding the Brexit-referendum and other recent binary referendums have rekindled thinking about the multi-option referendum as a possible alternative, empowering voters to express their views on more detailed policy options, reducing emphasis on adversarial competition and facilitating creativity in the process of option formulation.

We define multi-option referendums as referendum balloting on three or more mutually exclusive policy alternatives – in practice usually two or more alternatives alongside the status quo – resulting in one winning option.Footnote4 Multi-option referendums increase possibilities for voters to express their preferences, may reduce status quo bias because an explicit no-option is absent and can provide insight into support for various alternatives beyond two extremes and beyond voters’ most highly favoured option. The multi-option format also comes with new challenges, including cognitive demands on voters, agenda-setting demands to formulate a limited yet relevant set of options, selection of a voting method satisfying various voting requirements and electing an undisputed majority winner.Footnote5

In this article we zoom in on one of those challenges in particular: the agenda-setting stage, in which multi-option ballots are triggered and ballot content is formulated. This stage opens up a myriad of opportunities for process design and actor involvement, each with particular opportunities and limitations. Other design choices such as voting method selection receive specific attention in other sourcesFootnote6 and are beyond the scope of our agenda-setting analysis because they do not pertain to ballot content and often do not involve citizen influence. Processes of formulating ballot content and selecting a voting method are analytically separable and our focus is on the former.

1.2. Ballot agenda-setting

Whilst agenda-setting as a concept is usually reserved for agendas of deliberation and decision-making in the representative-political arena, several core elements lend themselves well for application to the referendum process. We view agenda-setting as “pre-political, or at least pre-decisional processes [which] are often of the most critical importance in determining what issues and alternatives are to be considered by the polity”.Footnote7 In referendum processes, the decision agenda is the ballot presented to the electorate. In this article, we focus on setting this voting agenda.

Multi-option ballot agenda-setting precedes the actual voting stage, making it relevant to study because referendum outcomes are strongly predefined by which alternatives are on the ballot.Footnote8 Two specific pre-voting phases entail (a) the step in which a referendum is triggered, or initiated, on a particular topic and (b) the steps in which the concrete ballot options or alternatives pertaining to this topic are formulated.Footnote9 Together these two steps form the “agenda-setting or issue-framing stage, where the matter to be put to the people is formulated”.Footnote10 Multi-option referendums broaden the scope for citizen empowerment compared to triggering a binary referendum on a specific proposal, as the latter rules out other ballot alternatives and civic input.

1.3. Data collection and analysis

We take an empirical approach to agenda-setting practices, providing an innovative overview of ballot triggering and formulation from the perspective of actor involvement and civic empowerment. We focus on referendum cases between 1958 and 2018. Data on national-level multi-option referendums come from a dataset assembled by one of the authors. Further elaboration on the compilation of this dataset is provided in the online appendix. We supplemented these data with further examples from sub-national levels. A complete overview of Swiss cantonal-level multi-option referendums since 1999 was compiled by analysing official cantonal voting data websites. Illustrative cases of subnational multi-option referendums elsewhere were found through online searches in English, German and Dutch and are referred to individually in the text.

We analysed the actors involved in setting the decision agenda for these referendums, which led us to identify six main models with common overarching characteristics from the perspectives of referendum triggering and option formulation. For each model we selected one illustrative example, for which we gathered further data through legislation, voter information brochures, official voting results websites, online newspaper articles, government papers, electoral commission reports and academic articles and books. All case-specific sources used are referred to in section 3. We do not intend to claim that all illustrative example topics were of equal political significance, nor that all referendum cases within a single model category are; our goal is to demonstrate differences with regard to the processes of producing ballot content.

We approach the topic from an inductive and political scientist perspective, seeking patterns in real-world data on multi-option referendums. Our contributions are a typology, mapping variation in ballot agenda-setting processes, and an analysis in which we tease out similarities and differences between the agenda-setting models and reflect on their comparative opportunities and limitations for civic empowerment. It is not our intent to apply a normative lens or to advocate multi-option referendums in general or any specific model in particular. We acknowledge that individual referendums may promote or restrict democratic empowerment in a myriad of further ways beyond the scope of this article, including deliberative opportunities during referendum campaigning, voter information provision and voter eligibility requirements. Our reflection on the comparative advantages and limitations of different agenda-setting models may provide a stepping stone for further research on the desirability of different models for particular topics or political contexts.

In the next section we discuss literature on referendum triggering and ballot option formulation. In the third section, we present our typology of multi-option ballot agenda-setting processes. For each model we discuss the defining process steps and explore the roles of different actors in setting the voting agenda, illustrated with an example. In section four we discuss how variation between the six models affects the democratic empowerment of civic actors. In the conclusion, we reflect on the generated insights.

2. Referendum ballot agenda-setting

The core essence of any referendum is that the citizenry can partake in decision-making by voting directly on an issue-related proposal. Yet, citizens can also take on other roles in the referendum process largely prior to that of voter. In this section we discuss referendum triggering and option formulation and elaborate on the relevance of broadening our scope to the distinctive category of multi-option referendums.

2.1. Referendum triggering

Understanding agenda-setting in referendum processes generally begins with distinguishing formal abilities to initiate a referendum. Various authors juxtapose two opposite types: top-down, majority- or government-initiated referendums and bottom-up, minority- or citizen-initiated referendums.Footnote11 Some jurisdictions also legislate for mandatory referendums constitutionally requiring popular approval on treaties or laws approved by parliament. A traditional top-down referendum is not formally required but held on the voluntary initiative of a parliamentary majority, often the government.

On the bottom-up side of this classification, referendums are triggered by institutional minorities or sizeable minorities of citizens presenting a minimum number of supporting signatures.Footnote12 The referendum can be proactive, as in citizen-initiatives for direct legislation, or reactive, as in veto-referendums seeking to correct parliamentary legislation. In either case the government has little formal control over the process.Footnote13 In several countries, institutional minorities can challenge legislation approved by a political majority. Minorities may constitute parliamentary members pre-specified in legislation (e.g. 1/3) or territorial actors such as cantons or regions.Footnote14 Some jurisdictions legally provide for referendum triggering by an upper parliamentary chamber. Legislation for corrective referendums essentially adds citizens, political minorities or other pre-defined actors as an additional veto player to the policymaking process, requiring their (implicit) agreement.Footnote15

2.2. Referendum option formulation

Whilst triggering a referendum defines a policy problem, the ballot option formulation phase fulfils another important agenda-setting role.Footnote16 Though all bottom-up referendums provide citizens with triggering powers, there is a distinction between reactive and proactive referendums in terms of option formulation. Whereas the classic corrective referendum facilitates a veto of approved legislation (reactive), a citizen initiative provides citizens with the opportunity to formulate a policy proposal (proactive).Footnote17 In “decision-promoting” referendums, the same actor is responsible for both triggering the referendum and formulating its policy proposal; in “decision-controlling” referendums two different actors are involved.Footnote18

Top-down binary referendums usually provide no opportunity for citizens to influence ballot content; the government or parliamentary majority formulates the proposal subjected to a referendum. Depending on the topic, experts can be involved in (co-)designing a ballot proposal through (extra-)parliamentary committees, electoral commissions and/or expert hearings. It has been suggested that upper parliamentary chambers can also fulfil a solution-searching role.Footnote19 In exceptional instances, initiators of top-down referendums delegated option formulation to citizens in the shape of a mini-public.Footnote20

In top-down triggered processes, it is common for an electoral or referendum commission to review the referendum question and suggest ballot content wording. Good practice for bottom-up referendums is to allow citizens to propose either a specifically-worded draft or a concrete proposal in general wording.Footnote21

2.3. Unravelling agenda-setting for multi-option referendum ballots

Literature on agenda-setting for referendum voting predominantly focuses on triggering a binary run-off on a single policy proposal. Because the single-proposal focus presupposes a single ballot author, the extant literature does not suffice to capture diversity observed in option formulation procedures for multi-option balloting. Whilst the triggering and option formulation dimensions of agenda-setting in referendum literature are analytically applicable to multi-option balloting, the potential involvement of a wider diversity of actors in proposing ballot options requires a broader perspective on multi-option ballot agenda-setting.

3. Six models of multi-option ballot agenda-setting

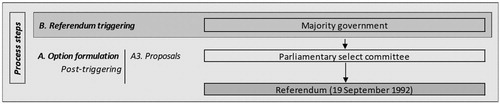

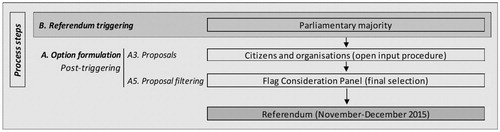

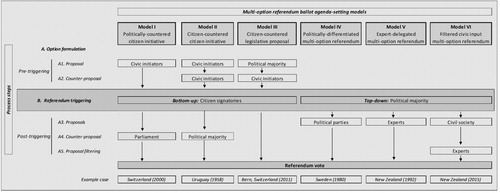

We distinguish six multi-option referendum agenda-setting processes each characterized by the involvement of political minorities, civil society or experts.Footnote22 presents the six models, visualising – chronologically from top to bottom – the different process steps leading to a referendum vote: ballot content formulation (process steps A1 through A5) and formal referendum triggering (process step B). The commonly accepted division between two main referendum types is prominent: bottom-up triggered (I, II and III) and top-down triggered (IV, V and VI) models. Agenda-setting powers are further diversified through various processes of ballot option formulation taking place either before (steps A1 and A2) or after (steps A3, A4 and A5) the referendum is triggered. Characteristic for the bottom-up models is that at least one of the options has already been formulated before the referendum is formally triggered. Under the top-down models, the referendum is triggered before ballot options are formally specified. In this section we present each model in turn, discussing its basic characteristics and main process steps. We highlight an illustrative case for the model and provide initial observations of actor empowerment.

Figure 1. Procedural typology of six ballot agenda-setting process models depicting referendum triggering (step B) and option formulation (steps A1 to A5) resulting in a multi-option referendum vote.

3.1. Model I. Politically-countered citizen initiative

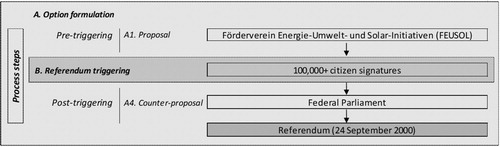

In the first model, a referendum follows from a citizen initiative (process step A1). Predefined regulations specify eligibility conditions, including eligible policy topics and required numbers of valid supporting signatures. Legislation specifies whether popular initiatives can concern regular policy issues, constitutional amendments or both, with signature requirements usually being higher for constitutional changes. A group of individual citizens, a minority political party or an action group takes the initiative to formulate a proposal and collects signatures from the wider electorate to demonstrate societal support (process step B). If conditions are met, policymakers are required to submit the proposal to a referendum vote. The triggered referendum is initially binary, and takes the shape of a multi-option ballot only if policymakers respond by formulating a counter-proposal (process step A4). This usually requires a parliamentary majority, though formal provisions may specify other constellations. In the referendum, voters express their opinion on both the initiative and the counter proposal. A Swiss example is described in Box 1 and .

Between 1993 and 1995, the initiating committee Förderverein Energie-Umwelt- und Solar-Initiativen (FEUSOL)Footnote57 collected 114,824 valid signatures for constitutional amendments promoting solar energy. The initiative proposed two constitutional articles posing an additional levy on non-renewable energy sources, at least half of its proceeds benefitting solar energy applications.Footnote58 The Federal Council considered the focus on solar energy too narrow and recommended the federal parliament to reject the initiative without a counter-proposal.Footnote59 The Swiss Council of States disagreed and instead started preparing a counter-proposal. After several debates, both parliamentary chambers – Council of States and National Council – agreed on a constitutional article. Like the initiative, it proposed a levy on non-renewable energy, but its proceeds would benefit renewable energy more generally. In the referendum, neither initiative nor counter-proposal were approved and the status quo prevailed.Footnote60

Model I provides agenda influence to civic initiators and supporting citizens. The counter-proposal provision prevents a citizen initiative from circumventing the political arena entirely. Counter-proposal provisions are used in various legislatures with established use of direct democratic instruments such as Switzerland and Liechtenstein, where cases under this model occurred twelve and nine initiatives respectively. In practice, Swiss counter-proposals often represent a compromise between the citizen proposal and the status quo.Footnote23 Also in Uruguay, the political majority or a 2/5 parliamentary minority may propose a “proyecto sustitutivo.”Footnote24 In 1946 this led to a minority-formulated counter-proposal to a citizen initiative on constitutional reforms.Footnote25 Under similar legislation, a 1996 referendum in Slovenia triggered by a citizen initiative featured two counter-proposals: one by a parliamentary minority and one by the upper parliamentary chamber, the National Council.Footnote26 On the subnational level, the German state of Bavaria also has provisions for counter-proposals to popular initiatives.Footnote27

3.2. Model II. Citizen-countered citizen initiative

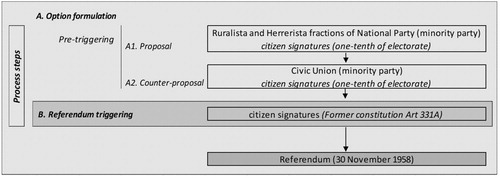

Under the second model a referendum also follows from a citizen initiative subject to predefined conditions (process step A1). In response, other civic groups field their own alternative policy proposal on the issue, subject to the same signature requirements.Footnote28 When one or more proposals meet the requirements, a referendum is triggered (process step B) on the successful proposals alongside the status quo. In some jurisdictions, the political majority can propose a counter-proposal to the popular initiatives after the referendum has been triggered (process step A4). A Uruguayan example involving two popular initiatives is described in Box 2 and .

On 18 May 1958, the Ruralista and Herrerista fractions of the oppositional National Party formulated a constitutional reform proposal involving the re-introduction of a Presidential system, separate election terms for parliament and president and the abolishment of the double simultaneous voting system known as “Lemas”. On 29 May the significantly smaller Civic Union raised an alternative initiative, proposing a presidential system including Lemas. Signatures of one tenth of the electorate for each proposal triggered a referendum. Held in November 1958 alongside national elections, neither proposal secured the required 35% support of all eligible voters.Footnote61

Unique for model II, which is rather uncommon in practice, is that the ballot can consist solely of competing citizen-supported proposals. The Uruguayan constitution allows the political majority to present a counter-proposal after referendum triggering (process step A4), merging an element of model I into model II.Footnote29 This occurred in 1966 when three constitutional reform packages proposed by political minorities through the popular initiative channel faced a political majority counter-proposal.

A similar procedure involving competition of multiple citizen initiatives exists in several US states. In California, Maine and Washington, multiple civic groups can present ballot propositions supported by sufficient citizen signatures.Footnote30 What makes the procedure different is that propositions are not explicitly juxtaposed during referendum voting. When the court decides that several approved propositions have conflicting content, all but the one with the highest approval rate are invalidated. The US practice represents an indirect, implicit form of multi-option balloting rather than a direct, explicit counter-proposal to an initiative.

3.3. Model III. Citizen-countered legislative proposal

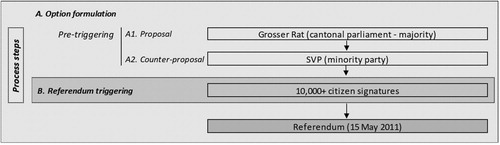

The third model starts from a legislative proposal approved by parliament (process step A1). Similar to common practice for veto referendums, citizens or political minorities can collect signatures to evoke a binding referendum on the legislative proposal. Under this model, however, civic initiators also formulate a counter-proposal (process step A2). When sufficient citizen signatures back the counter-proposal, a referendum on both proposals is triggered (process step B). Referendum processes of this type are deployed at the cantonal level in Switzerland.Footnote31 Multiple counter-proposals may be submitted by different groups as long as each meets the requirements. An example of this model is described in Box 3 and .

In March 2010 the Bern cantonal parliament passed a proposal to amend cantonal energy legislation, aiming to increase energy efficiency and encourage renewable energy use. Political party SVP formulated a counter-proposal, backed by cantonal businesses and home owners associations. The initiating committee amended the compulsory housing energy label and the levy on electricity and proposed that financial means for renewable energy come from general cantonal funds.Footnote62 The counter-proposal collected more than double the required amount of signatures. In the referendum, 32% approved the parliamentary energy bill and 79% approved the civic energy bill.Footnote63

This model empowers citizens to correct policymaking beyond triggering a vetoing vote. The alternative proposal adds a constructive component to a reactive referendum process. In most cases political minorities or dedicated action or interest groups initiate a counter-proposal. Present use of the citizen-countered legislative proposal appears to be confined to the Swiss cantonal level. In Bern, around half were triggered by political opposition parties.Footnote32 Others were formulated by newly formed societal groups, such as “Flugschneise Süd-Nein” (Zurich) and “Majorz: Kopf-statt Parteiwahlen” (Nidwalden), or by cooperating groups of individual citizens (Zurich, 2011 and 2012). In two instances more than one counter-proposal was proposed.Footnote33

3.4. Model IV. Politically-differentiated referendum

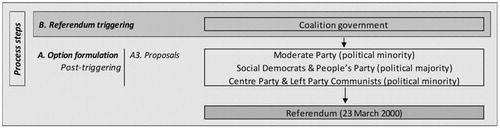

The politically-differentiated referendum is initiated by a parliamentary majority (process step B). Whilst the general possibilities for a majority-triggered referendum may be laid down in legislation, specific regulations for a multi-option format tend to be drawn up ad hoc. The key characteristic of this model is that concrete ballot options are each formulated by a different parliamentary party or alliance of parties (process step A3). Occurrences of referendum cases with this differentiated focus on political party lines are rare. A well-known case is described in Box 4 and .

Coalition partners of the 1978 Swedish government could not reach consensus on the nuclear issue, which diverged from the ideological left-right division.Footnote64 The referendum rose as a conflict-resolution instrument.Footnote65 Three alternative scenarios were offered to voters. The first (supporting continuation of the existing Energy Bill) was proposed by the liberal-conservative Moderate Party, the second (supplementing the existing bill with additional paragraphs on renewable energy) by the Social Democrats and the People’s Party, together forming a majority. The third (demanding pro-active phasing out) was proposed by the Centre Party and the Left Party Communists. Voters voted for their most preferred option. The close outcome (18.9% – 39.1% – 38.7%) evoked confusion, but the second alternative was adopted as the new phase-out policy.Footnote66

In Sweden, political parties formulated the ballot options. Bearing in mind the Ostrogorski paradox, however, political party views do not necessarily accurately represent societal positions on the issue. Two options were highly similar, and none included longer-term maintenance of nuclear energy. Although all referendums, both binary and multi-option, may to some extent rely on partisan cues, this particular model most strongly approximates a second order election.

3.5. Model V. Expert-delegated referendum

Expert-delegated referendums are triggered by parliament, usually by the government (process step B), which then delegates the formulation of ballot options to an external body of experts (process step A3). The expert body can be an existing body, such as an Electoral Commission, or a newly formed body, recruited either internally or externally. It analyses possible policy scenarios, fit with the country context and corresponding levels of societal support. The findings are cumulated into a report with recommendations for ballot options and referendum conduct. Legislation for the specific multi-option referendum is usually formulated ad hoc. An illustrative case from New Zealand is described in Box 5 and .

Electoral reform became a prominent topic in 1980s New Zealand because of societal dissatisfaction with the two-party system and several “wrong winner” elections.Footnote67 In 1984 a Royal Commission on the Electoral System recommended a referendum on implementing a Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system. Ignored by the ruling Labour Party, National Party successfully adopted the referendum promise during election campaigning. National. Also not favouring radical reform, National averted a direct FPTP-MMP vote. An instituted parliamentary select committee proposed a referendum bill with three options: MMP, recommended by the Royal Commission, Supplementary Member (SM), its own preference, and Preferential Vote (PV), appealing to some parliamentarians. Written submissions persuaded the committee to include Single Transferable Vote (STV) as a fourth option. In the 1992 referendum, voters selected their preferred alternative system: MMP.Footnote68

In this model ballot formulation is deliberately delegated to a body of experts. The level of convergence between experts and dominant political views influences to which extent this delegation depoliticizes ballot formulation … The recruitment of experts varies widely, ranging from parliamentary committees to existing advisory bodies and specially constituted expert panels. Rather exceptional was the Newfoundland 1984 referendum in which 45 delegates were directly elected to a National Convention preparing the ballot options.Footnote34

The expert-delegated model is the dominant top-down agenda-setting model and is particularly common for referendums on electoral or status reforms. In Guernsey (2018) and Jersey (2013) referendums, voters ranked alternative scenarios for electoral reform as proposed by the Guernsey States’ Assembly & Constitution Committee and the Jersey Electoral Commission respectively.Footnote35 In 2014, the Referendum Commission on St Eustatius proposed four ballot options for a status referendum.Footnote36 Whilst it is plausible that expert involvement contributes to more balanced options, this is not always guaranteed. In 2017 the Puerto Rican Electoral Commission proposed a referendum on political status vis-à-vis the US with two alternatives: Statehood and Independence/Free Association. The selection was heavily influenced by pro-statehood ruling party PNP.Footnote37 The US rejected the two-option ballot as “not drafted in a way that ensures that its results will accurately reflect the current popular will of the people of Puerto Rico”.Footnote38 In response, a status quo option was included. The three-option referendum nevertheless suffered from boycotts by supporters of an improved current status.

3.6. Model VI. Filtered civic input referendum

The filtered civic input referendum is triggered by a political majority (process step B). The option formulation process is then managed by an expert body, usually of ad hoc constellation. A wide range of individual citizens and organisations may propose ballot options, provide general input on new policy and respond to submitted proposals (process step A3). The open consultation procedure may take different online and/or offline shapes and involve different stages. Distinctive is the additional filtering step (process step A5) in which the external body trims down the final ballot options. A telling example features in Box 6 and .

A postal referendum on a potential new flag was proposed by New Zealand’s Prime Minister John Key and approved by parliament.Footnote69 The Flag Consideration Project involved workshops and information stands across the country, an online deliberation forum receiving over 43,000 contributions and 1.1 million social media posts. Citizens submitted 10,292 flag designs. The specially recruited Flag Consideration Panel – experts of diverse age, region, gender and ethnicity – filtered the submitted designs and comments to arrive at a shortlist of four which was accepted by parliamentary vote.Footnote70 The selection sparked public protest because of the perceived similarity of the designs and their close resemblance to the Prime Minister’s preferences. A 50,000-signature petition convinced parliament to include a fifth flag.Footnote71 The five flags were voted on using Alternative Vote procedures. The winning flag design was later defeated by the existing flag in a run-off stage.Footnote72

The filtered civic input model is unique in its broadly designed focus on obtaining civic input.Footnote39 Any citizen can suggest ballot options and policy qualities without engaging in collective action. A few variations on this model occurred at subnational levels. The 2018 referendum on electoral reform in British Columbia, Canada, was preceded by a public consultation process entitled “How we vote”. The 91,725 questionnaire responses, 58,000 open-ended comments, and community groups meeting inputs were collated into a report with accompanying recommendations for referendum design.Footnote40 A 2012 municipal referendum in Arnhem, The Netherlands, followed from citywide dialogue with debates, interactive sessions and target group sessions on eight pre-defined options for renewed harbour area design. An expert panel of civil servants, project developers and external urban planners distilled three ballot options from the interactions.Footnote41 A 1990 referendum in Oregon offered voters four alternative proposals for school funding. After the referendum had been triggered, a joint House-Senate committee drew up the alternatives using input from eight public hearings across the state with randomly selected community members to achieve a cross-section of public opinion.Footnote42

4. Variation in ballot agenda-setting processes

In this section we reflect on the implications of variation between the six models for citizen empowerment. We summarize the scope for agenda control and related advantages and limitations of the six models in . We elaborate on variations in civic empowerment between the models in the agenda-setting phases of referendum triggering (4.1) and option formulation (4.2) and briefly discuss the empowerment of referendum voters (4.3) as a result of civic involvement in the agenda-setting stage.

Table 1. Scope and limits of agenda control under six multi-option ballot agenda-setting models.

4.1. Referendum triggering under the six models

Process step B in highlights which actors trigger the referendum. Following general referendum terminology, we distinguish two main types: bottom-up (I, II and III) and top-down (IV, V and VI) models. Legal basis is a determining factor: citizen-triggered referendums always depend on legislation specifying the eligibility conditions which bind policymakers to organize the proposed referendum. Acquiring civic support for a proposal beyond the confines of the initiating committee is essential, reserving a significant role for a larger group of citizens as signatories.

Regulations for activating top-down referendums may be embedded in legislation, but they can always be triggered by a majority and regulated by ad hoc legislation. Triggering a referendum is sometimes part of an election promise or used as a conflict mediating device for intraparty or intra-coalition disagreement. These and other potentially strategic motivations help to explain why, beyond ideals of broad democratic inclusion or innovative ambitions, a political majority might resort to a referendum rather than legislating directly for a most-preferred option. Societal pressures for change may also influence referendum triggering through prior lobbying (New Zealand, 2015) or a citizen petition (St Eustatius, 2014).Footnote43 Some countries regulate for direct referendum triggering by a parliamentary minority or upper chamber, but no referendums with a multi-option format were identified that were triggered by such actors without the support of citizen signatures.

The absence of formalized rights for citizens to set their own agenda renders the top-down models more vulnerable to elite control. Political elites have exclusive powers over the process, from deciding to hold a referendum to choosing the topic, setting the question and alternatives and outlining the process.Footnote44 Bottom-up processes are more explicitly regulated and initiatives in particular provide citizens with the possibility to “counteract the agenda-setting monopoly of political elites”.Footnote45

Bottom-up triggered citizen initiatives (models I and II) can be triggered on any eligible policy topic and demonstrate significant variation, varying from amendments to constitutional, electoral and tax legislation to innovations in health, energy, social and infrastructural policies. Citizen-countered legislative initiatives and top-down referendums exclude citizens from choosing the referendum topic. Top-down multi-option referendums tend towards electoral, sovereignty, ceremonial and other constitutional issues. Generally speaking, the ad hoc nature of top-down referendums lends itself to one-off issues of paramount importance to the state, whereas bottom-up referendums are deployed for day-to-day policy issues confronting citizens. A challenge specific to bottom-up models is that referendums may be triggered on individual issues taken out of a broader context. Mutual dependencies between issues may upset policy coherence between various policies or programmes. Popular initiatives may also raise questions of financing. Whereas policies put forward in top-down triggered referendums face similar dependencies, their financial and programmatic implications can arguably be premeditated and weighed before the referendum options are finalized.

4.2. Option formulation under the six models

The bottom-up models regulate for a select group of civic initiators to formulate a policy proposal, either on a topic of their choice (models I and II) or within the boundaries of a legislative proposal (model III). Initiative is often taken by a civic action group or subset of a political party or movement.Footnote46 This entails a risk that narrow goals of initiators, which tend to be better organized politically and financially, dictate the ballot content.Footnote47 In bottom-up models, political majorities lack discretion to obstruct the referendum, though they maintain partial agenda control as formulators of one of the ballot options: the sole counter-proposal in model I (step A4), the initial legislative proposal in model III (step A1) and optionally a counter-proposal in model II (step A4). Political elites can – and often do – respond to a popular initiative with a compromise option, strategically placed between the popular initiative and the status quo to maximize votes.

A main characteristic of the top-down models is that referendums are triggered before the ballot options are formally specified. In practice, one or several ballot options may be on the scene before a referendum is formally triggered. Contrary to most binary referendums, however, the referendum is not triggered on one specific proposal. Even if the order of referendum triggering and option formulation is muddled in some cases, the defining model characteristics remain: political majority triggering and a specific type of actors formulating the options. When ballot formulation (step A3) is delegated to experts (model V), the constellation of expert bodies varies from formalized and pre-existing, such as an electoral commission, to specifically recruited for the referendum process, such as the Flag Consideration Panel. Experts can be recruited from outside the legislature or within, such as a parliamentary select committee. The decision to delegate ballot formulation can democratically empower experts to seek alternative options but can also be employed strategically to avoid a binary vote on a politically undesirable proposal, as in New Zealand in 1992. Model V is the only model in which a single institutional actor (an expert body) formulates and selects all ballot options. Other models can be considered more competitive models, as multiple actors bring in competing alternatives, either through a deliberate division of labour (models IV and VI) or a reactive pattern (models I, II and III). It follows that the distinction between decision-promoting and decision-controlling referendums is less obvious for multi-option referendums than for binary ones. Citizen initiatives (models I and II) are initially decision-promoting at triggering, but eventually include multiple ballot content authors. Referendums challenging a legislative proposal (model III) would be decision-controlling in a binary format, but now also feature a ballot proposal formulated by citizens. In top-down models, formal powers to decide ballot content remain with political majorities, strictly rendering them decision-promoting, though various other actors are involved in actually proposing the ballot options.

The filtered civic input referendum (model VI) is the most elaborate top-down type in terms of public deliberation opportunities, with the referendum vote representing the clearly defined decision at the end of a multi-staged process.Footnote48 Civil society actors propose solutions (step A4) to a policy question pre-defined by a political majority.Footnote49 Input is more individualized than under the bottom-up models with proposals not requiring signatories, providing a more level playing field for citizens with limited political and financial resources. The trade-off is a much larger volume of individual inputs, lowering the weight and visibility of individual submissions. Contrary to formalized responsibilities under bottom-up models, uptake ultimately depends on expert filtering and political majority approval. Expertise serves as an external filter (step A5) on the deliberation of ordinary citizens, eliminating irrelevant or unfeasible options to arrive at a small subset of policy options.Footnote50 As witnessed in the New Zealand flag referendum, the final step of political majority approval of the proposed ballot entails a final possibility for the inclusion of societal views.

Referendums may provide an additional avenue of agenda influence to minority parties or societal groups.Footnote51 The politically-differentiated (IV) model does not provide for citizen influence beyond voting, but does empower political minority parties to indirectly represent diverse societal views and interests by formulating their own ballot option. Parties can however also strategically formulate their proposals in relation to those of other parties to attract more votes.Footnote52 In some jurisdictions, a predetermined parliamentary minority may directly formulate a counter-proposal to a citizen initiative, as in Slovenia and Uruguay. In the absence of such provisions, minority parties can use the avenues of citizen initiatives (models I and II) and citizen-supported counter-proposals (models II and III) to forward their proposal backed by citizen signatures. Civil-society organisations fare well under the filtered civic input model (VI), where they can pool resources. Their collective submissions (step A4) may carry more weight than individual citizens’ submissions and their reputation may lend them more credence in the filtering stage (step A5).

4.3. Empowering citizens as voters

The opportunities and limitations of the six process models also impact on the empowerment of citizens in their role as voters. The diversity of ballot options ultimately offered to voters depends on the interactions of formulating actors. In the bottom-up models, actors respond to each other with a modified proposal, presenting voters with nuanced variations of a proposal. Models II and III allow multiple civic groups to formulate their own counter-proposal, thereby most directly meeting the requirement that successful multi-option ballots include all options with reasonable amounts of societal support.Footnote53 In the politically-differentiated model, the ideologies and strategies of political parties determine ballot content, risking that attainable policy scenarios enjoying societal support but insufficient political support are excluded. The range of ballot options resulting from expert-delegated and filtered civic input models varies from highly different policy scenarios to nuanced policy details. A referendum on electoral reform can entail, for example, wholly different electoral systems (New Zealand, 1992) or similar systems with detailed variations (Guernsey, 2018). Democratic empowerment of the wider electorate depends on the confines determined by political majorities and on the abilities of experts or civic initiators to understand and translate public opinion.

Though an analysis of voting methods is beyond the scope of this article, a brief reflection on our illustrative examples shows that voters could express their single favourite option (models II, IV and V examples), vote in favour of each proposal they approved (models I and III examples)Footnote54 or rank the various options (model VI example). Voting procedures can differ within the model categories, as there is no intrinsic link between which actors are involved in agenda-setting and which voting method is used. In this article we contend that empowering voters follows not only from how they vote but also to an important extent from the options available to them on the ballot.

5. Conclusion

The key contributions of our exploration are succinctly summarized in – depicting six central models of ballot agenda-setting for multi-option referendums – and – summarising the scope for agenda control and related democratic advantages and limitations. We have highlighted imminent variation in the involvement of different non-political majority actors – citizens, experts, political minorities – in pre-political and pre-decisional agenda-setting processes. We have shown how not just voting in a referendum but also setting the voting agenda holds potential for civic democratic empowerment. We encourage further research on whether specific models might be especially suitable for particular political contexts or topics. Our classification can provide a starting point for such an endeavour.

A balanced ballot is a necessary though not sufficient condition for empowered multi-option balloting. Voters must also be able to express their opinion adequately on the available options. A voting method focused on absolute majority consent as opposed to plurality rule, is arguably best suited to uphold the added value of extended ballot options regardless of the agenda-setting model. Thresholds, legal binding and political uptake further affect whether civic agenda-setting empowerments come to full fruition in the referendum process as a whole. Beyond what is currently observed in practice, further variations on the six models are conceivable in which direct and deliberative democratic elements explicitly complement each other. For example, deliberative citizens’ assemblies could explore and filter policy scenarios in a model similar to the expert-delegated model, presenting the electorate with the assemblies’ shortlist.Footnote55 Alternatively, citizens’ assemblies can be involved in developing counter-proposals to a legislative proposal rather than relying on a small group of initiators to represent the citizenry.Footnote56

Though we explore ballot agenda-setting and citizen empowerment in relation to multi-option designs, our findings are more widely applicable to referendum democracy. Inviting citizen input, adding consultative elements and incorporating expert advice can be feasible strategies to mitigate the occasionally sharp edges of the binary referendum instrument. But first and foremost, the models open up avenues for thinking and acting beyond the binary format dominating the field. By viewing referendums as processes entailing multiple steps, actors and policy scenarios, we can transcend a dichotomous analysis of referendums as instruments posing citizens against representatives by voting on one specific proposal.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank their colleagues at the Politics and Public Administration section as well as Kristof Jacobs and the Editors and three anonymous reviewers of this journal for their helpful feedback on earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Charlotte C. L. Wagenaar

Charlotte C. L. Wagenaar is a researcher at Tilburg University, specialising in multi-option referendums.

Frank Hendriks

Frank Hendriks is professor of comparative governance at Tilburg University, specialising in democratic governance and innovation.

Notes

1 a.o. Suksi, Bringing in the People; Altman, Direct Democracy Worldwide; Taillon, Democratic Potential of Referendums.

2 Tierney, Constitutional Referendums, 23.

3 a.o. Setälä, Role of Deliberative Mini-Publics, 206; Hendriks, Democratic Innovation Beyond Deliberative Reflection.

4 There are various ways in which multiple options can be presented on a ballot paper and voted on, a full analysis of which transcends the scope of our article. In the online appendix, we elaborate on the voting procedures of the illustrative examples employed in this article.

5 See Wagenaar, Beyond For or Against, for an extended discussion of the advantages and challenges of multi-option referendums.

6 a.o. Wagenaar, Lessons from Multi-Option Referendums; Sargeant et al., Mechanics of a Further Referendum; Tierney, The Multi-Option Referendum; Emerson, Defining Democracy.

7 Cobb and Elder, Politics of Agenda-Building, 903.

8 Altman, Direct Democracy Worldwide; Collin, Peacemaking Referendums, 721.

9 In binary referendums, the second phase is often superfluous, as triggering takes place on one specific legislative proposal or popular initiative. Literature on option formulation (a.o. Hug and Tsebelis, Veto Players and Referendums) focuses on the author of the legislation as formulated prior to referendum triggering.

10 Tierney, The Multi-Option Referendum, 51.

11 a.o. Papadopoulos, Top-Down and Bottom-Up Perspectives; Vatter, Lijphart Expanded; Altman, Direct Democracy Worldwide.

12 Müller, Plebiscitary Agenda-Setting, 304.

13 Papadopoulos, Top-Down and Bottom-Up Perspectives; Vatter, Lijphart Expanded.

14 Bulmer, Minority-Veto Referendums.

15 Hug and Tsebelis, Veto Players and Referendums.

16 Bua, Agenda-Setting and Democratic Innovation.

17 Altman, Direct Democracy Worldwide; Gherghina, Direct Democracy and Regime Legitimacy

18 Uleri, Referendum Experience in Europe.

19 Goodin and Spiekermann, Epistemic Theory of Democracy.

20 Farrell et al., “Systematizing” Constitutional Deliberation.

21 Venice Commission, Code of Good Practice on Referendums 2007, 19.

22 In a theoretically less obvious and practically exceptional variant, all ballot alternatives are formulated by a political majority. In the canton of Bern, a political majority may propose both a main referendum proposal (Hauptvorlage) and an alternative proposal (Eventualantrag) (cantonal constitution, article 63). This procedure is criticised for being employed strategically to disqualify a citizens’ counter-proposal (Baumgartner and Bundi, Eventualantrag und Volksvorschlag).

23 Kaufmann et al., Guidebook to Direct Democracy.

24 Uruguayan constitution, article 331B.

25 Lissidini, Mirada Crítica a la Democracia Directa.

26 Nikolenyi, When Electoral Reform Fails.

27 Landeswahlgesetz Bayern, part 3.

28 Because sequencing suggests that second – and further – proposals are formulated in response to the first citizen initiative, we list them as counter-proposals (step A2) rather than simultaneous proposals (step A1).

29 Constitution Art 331A. We view a citizen initiative countered by both another citizen initiative and a political counter-proposal as a variation on model II rather than on model I because of the exceptional legal possibility for multiple citizen initiatives to be proposed in the absence of a political proposal.

30 Lagerspetz, Social Choice and Democratic Values, 121–24.

31 Glaser et al., Das Konstruktive Referendum. Currently in the cantons of Bern and Nidwalden. Between 2005 and 2013 also in the canton of Zurich. In this article, we use the term citizen-countered legislative proposal to explicitly refer to the reactive process.

32 Website Der Bund. “Zu kompliziert für das Volk?” (28 August 2011).

33 Glaser et al., Das Konstruktive Referendum. In May 2011 (Zurich) and September 2013 (Nidwalden).

34 Baker, Falling into the Canadian Lap.

35 States’ Assembly & Constitution Committee. Referendum on Guernsey’s Voting System. P. 2017/49.

States of Jersey Electoral Commission. Final Report January 2013. St Helier: Electoral Commission, 2013.

36 Referendumverordening 2014–2. Time constraints prevented continuation of the initial plan to involve three external advisors after parliament rejected a first selection of experts over perceived conflicts of interest.

37 Party politics in Puerto Rico is divided along the lines of ideologies for Puerto Rican status: pro-statehood PNP, pro-commonwealth PPD and pro-independence PIP.

38 Letter by Deputy Attorney General of U.S. Department of Justice to Puerto Rican Governor Rosselló, 13 April 2017.

39 Other top-down models may include elements of civic consultation like written submissions or public hearings – similar to parliamentary policymaking – though these are notably more passive than the widespread and actively encouraged public consultation campaigns under this model.

40 Attorney General. How We Vote.

41 Boogers and de Graaf. Een ongewenst preferendum.

42 The register-Guard, “School funding reform options unpopular” (16 March 1990), 3c.

43 Lobby by the NZ Flag.com trust in 2004 and by, three civic foundations on St Eustatius backed by one third of the electorate.

44 Tierney, The Multi-Option Referendum, 24.

45 Setälä, Theories of Referendum, 274.

46 Müller, Plebiscitary Agenda-Setting.

47 Magleby, Let the Voters Decide? 35.

48 Moore, Critical Elitism.

49 Bua, Agenda-Setting and Democratic Innovation, 12.

50 Christiano, Rational Deliberation, 42; Goodin and Spiekermann, Epistemic Theory of Democracy.

51 Hug and Tsebelis, Veto Players and Referendums.

52 Setälä, Theories of Referendum, Chapter 5.

53 Independent Commission on Referendums, Report of the Independent Commission on Referendums.

54 Until 1987, Swiss voters could only support one of the proposals. Initiators often withdrew their proposal before the referendum to boost the winning chances of the counter-proposal.

55 Similar processes in top-down binary referendums featured an assemblies’ proposed ballot option in Ireland (2018), Iceland (2011) and British Columbia (2004).

56 McKay, Designing Popular Vote Processes.

57 Launched by the Swiss Solar Agency.

58 Erläuterungen des Bundesrates (24.09.2000) (official voting booklet).

59 Menzi, Umverteilung ist nicht Mehrheitsfähig.

61 Lissidini, Mirada Crítica a la Democracia Directa.

62 Website Berner Zeitung, “SVP sagt Energiepolitik der Regierung den Kampf an” (28 May 2010).

64 Ruin, Sweden in the 1970s; Suksi, Bringing in the People.

65 Bjørklund, Demand for Referendum.

66 Suksi, Bringing in the People.

67 Renwick, “Wrong Winner” Elections.

68 Nagel, What Political Scientists Can Learn; Levine and Roberts, New Zealand Electoral Referendum.

69 National was one seat short of a majority and relied on other parties’ support.

70 Cabinet Paper New Zealand Flag Referendums Orders (2015).

71 Cabinet Paper New Zealand Flag Referendums (First Flag Referendum) Amendment Order (2015).

Bibliography

- Altman, D. Direct Democracy Worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Attorney General. How We Vote: 2018 Electoral Reform Referendum Report and Recommendations of the Attorney General. British Columbia, 2018.

- Baker, M. Falling Into the Canadian Lap: The Confederation of Newfoundland and Canada, 1945-1949. Royal Commission on Renewing and Strengthening Our Place in Canada, 2003.

- Baumgartner, C., and C. Bundi. Eventualantrag und Volksvorschlag im Kanton Bern. Leges 2017/1, 83–96.

- Bjørklund, T. “The Demand for Referendum: When Does it Arise and When Does it Succeed?” Scandinavian Political Studies 5 (1982): 237–259.

- Boogers, M. J. G. J. A., and L. de Graaf. Een ongewenst preferendum [Referendum evaluation report]. Tilburg: Tilburgse School voor Politiek en Bestuur, 2008.

- Bua, A. “Agenda Setting and Democratic Innovation: The Case of the Sustainable Communities Act (2007).” Politics 32, no. 1 (2012): 10–20.

- Bulmer, W. E. “Minority-Veto Referendums: An Alternative to Bicameralism?” Politics 31, no. 3 (2011): 107–120.

- Christiano, T. “Rational Deliberation among Experts and Citizens.” In Deliberative Systems, edited by J. Parkinson, and J. Mansbridge, 27–51. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Cobb, R. W., and C. D. Elder. “The Politics of Agenda-Building: An Alternative Perspective for Modern Democratic Theory.” The Journal of Politics 33, no. 4 (1971): 892–915.

- Collin, K. “Peacemaking Referendums: The Use of Direct Democracy in Peace Processes.” Democratization 27, no. 5 (2020): 717–736.

- Emerson, P. Defining Democracy. Heidelberg: Springer, 2012.

- Farrell, D. M., J. Suiter, and C. Harris. “‘Systematizing’ Constitutional Deliberation: the 2016-2018 Citizens’ Assembly in Ireland.” Irish Political Studies 34, no. 1 (2019): 113–123.

- Gherghina, S. “Direct Democracy and Subjective Regime Legitimacy in Europe.” Democratization 24, no. 4 (2017): 613–631.

- Glaser, A., U. Serdült, and E. Somer. “Das konstruktive Referendum–ein Volksrecht vor dem Aus?” Aktuelle Juristische Praxis (AJP) 10 (2016): 1343–1355.

- Goodin, R. E., and K. Spiekermann. An Epistemic Theory of Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Hendriks, F. “Democratic Innovation Beyond Deliberative Reflection: The Plebiscitary Rebound and the Advent of Action-Oriented Democracy.” Democratization 26, no. 3 (2019): 444–464.

- Hug, S., and G. Tsebelis. “Veto Players and Referendums Around the World.” Journal of Theoretical Politics 14, no. 4 (2002): 465–515.

- Independent Commission on Referendums. Report of the Independent Commission on Referendums. London: The Constitution Unit, UCL, 2018.

- Kaufmann, B., R. Büchi, and N. Braun. Guidebook to Direct Democracy: In Switzerland and Beyond. Marburg: Initiative & Referendum Institute Europe, 2010.

- Lagerspetz, E. Social Choice and Democratic Values. Heidelberg: Springer, 2016.

- Levine, S., and N. S. Roberts. “The New Zealand Electoral Referendum of 1992.” Electoral Studies 12, no. 2 (1993): 158–167.

- Lissidini, A. “Una mirada crítica a la democracia directa: el origen y las prácticas de los plebiscitos en Uruguay.” Perfiles Latinoamericanos 12 (1998): 169–200.

- Magleby, D. B. “Let the Voters Decide?” An Assessment of the Initiative and Referendum Process.” University of Colorado Law Review 66, no. 1 (1995): 13–46.

- McKay, S. “Designing Popular Vote Processes for Democratic Systems: Counter-Proposals, Recurring Referendums, and Iterated Popular Votes.” Swiss Political Science Review 24, no. 3 (2018): 328–334.

- Menzi, B. “Umverteilung zugunsten von nachhaltigen Energiequellen ist nicht mehrheitsfähig.” In Handbuch der eidgenössischen Volksabstimmungen 1848–2007, edited by W. Linder, C. Bolliger, and Y. Rielle, 591–592. Bern: Haupt Verlag, 2010.

- Moore, A. Critical Elitism: Deliberation, Democracy, and the Problem of Expertise. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Müller, W. C. “Plebiscitary Agenda-Setting and Party Strategies: Theoretical Considerations and Evidence from Austria.” Party Politics 5, no. 3 (1999): 303–315.

- Nagel, J. H. “What Political Scientists Can Learn from the 1993 Electoral Reform in New Zealand.” PS: Political Science and Politics 27, no. 3 (1994): 525–529.

- Nikolenyi, C. “When Electoral Reform Fails: The Stability of Proportional Representation in Post-Communist Democracies.” West European Politics 34, no. 3 (2011): 607–625.

- Papadopoulos, Y. “Analysis of Functions and Dysfunctions of Direct Democracy: Top-Down and Bottom-Up Perspectives.” Politics & Society 23, no. 4 (1995): 421–448.

- Renwick, A. “Do ‘Wrong Winner’ Elections Trigger Electoral Reform? Lessons from New Zealand.” Representation 45, no. 4 (2009): 357–367.

- Ruin, O. “Sweden in the 1970s.” In Policy Styles in Western Europe, edited by J Richardson, 141–168. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1982.

- Sargeant, J., A. Renwick, and M. Russell. The Mechanics of a Further Referendum on Brexit. London: The Constitution Unit, 2018.

- Setälä, M. “The Role of Deliberative Mini-Publics in Representative Democracy: Lessons from the Experience of Referendums.” Representation 47, no. 2 (2011): 201–213.

- Setälä, M. “Theories of Referendum and the Analysis of Agenda-Setting.” PhD Thesis. LSE, 1997.

- Suksi, M. Bringing in the People: A Comparison of Constitutional Forms and Practices of the Referendum. Groningen: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1993.

- Taillon, P. “The Democratic Potential of Referendums. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Limitations.” In The Routledge Handbook to Referendums and Direct Democracy, edited by L. Morel, and M. Qvortrup, 169–191. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Tierney, S. Constitutional Referendums. The Theory and Practice of Republican Deliberation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Tierney, S. The Multi-Option Referendum: International Guidelines, International Practice and Practical Issues. School of Law, Working Papers, 2013. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

- Uleri, P. V. “Introduction.” In The Referendum Experience in Europe, edited by M. Gallagher, and P.V. Uleri, 1–19. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1996.

- Vatter, A. “Lijphart Expanded: Three Dimensions of Democracy in Advanced OECD Countries?” European Political Science Review 1, no. 1 (2009): 125–154.

- Wagenaar, C. C. L. “Beyond for or Against? Multi-Option Alternatives to a Corrective Referendum.” Electoral Studies 62 (2019): 102091.

- Wagenaar, C. C. L. “Lessons from International Multi-Option Referendum Experiences.” The Political Quarterly 91, no. 1 (2020): 192–202.