ABSTRACT

To what extent does societal resilience help to prevent governance breakdown? The EU’s southern neighbourhood has been troubled by multiple security risks in recent years. The security situation of many citizens is uncertain and local populations frequently feel insecure, an indication of governance breakdown. Resilience has become a new focus in preventing a breakdown of governance. Yet, the extent to which resilience can help prevent governance breakdown remains unclear. Building on original survey data from Libya and Tunisia this study contributes empirical evidence to the debate. The article shows that limited statehood and order contestation do not necessarily lead to a breakdown of governance. Although both risks affect Tunisia and Libya to different degrees none of them are strongly correlated with the security perceptions of local populations. Additionally, resilience is key in preventing governance breakdown. Social trust and the legitimacy of governance actors are two main sources of resilience helping to prevent a breakdown of governance. Moreover, resilience has divergent effects on different dimensions of security governance breakdown. While resilience has stronger effects on national security perceptions, local security considerations are partly driven by other factors such as individuals’ economic resources.

Introduction

The areas which the EU considers to be its “southern neighbourhood” have experienced turbulent times in their most recent history. High hopes of local populations regarding greater freedom and more political rights accompanied the so-called Arab Spring in 2010/2011. However, a potential security governance breakdown that would affect millions of local citizens has been looming over the region for several years. Violent fighting in Libya, terrorist attacks in Tunisia, or violence against civilians in Egypt are just three examples illustrating the dire security situation many individuals find themselves in.Footnote1 Local populations’ (in-)security perceptions are an essential part of governance breakdown. If local populations perceive security as insufficient, they experience security governance as ineffective indicating a breakdown of governance. Hence, the question of how to improve citizens’ security perceptions is key to preventing a breakdown of governance in the EU’s southern neighbourhood.

Societal resilience as the ability of societies, communities, and individuals to prevent or peacefully adapt to crises has become a new research focus as a key mechanism for averting governance breakdown (see introduction to this special issue).Footnote2 At the same time, international political actors, such as the European Union (EU), the World Bank, or the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), have assigned a prominent role to resilience in their policies.Footnote3 The European Global Strategy (EUGS) explicitly spells out that the EU seeks to foster resilience in its neighbourhood with the hope of ensuring a peaceful environment and effective governance.Footnote4 This marks a significant shift from the EU’s goal of external democracy promotion to a more pragmatic strategy of resilience building.Footnote5 However, empirical evidence on the extent to which resilience can help prevent a breakdown of governance remains rare.

To what extent does societal resilience help to prevent governance breakdown? In answering this question, this study focuses on (in-)security perceptions of local populations as a key indication of governance breakdown. Thereby, the analysis sheds light on the micro foundations of the linkages between resilience and security governance breakdown.

Based on the empirical findings, this article contributes three arguments to the debate on resilience and governance breakdown. First, limited statehood and order contestation do not necessarily lead to a breakdown of governance. Although both risks affect Tunisia and Libya to different degrees, they are not strongly correlated with the security perceptions of local populations. This challenges claims from the failed states literature often equating weak statehood with insecurity and anarchy.Footnote6 Moreover, the results support arguments holding that effective governance is possible, even where limited statehood prevails.Footnote7 Second, resilience is key in preventing a breakdown of security governance. Social trust and the legitimacy of governance actors are two key sources of resilience improving security perceptions. If local populations consider governance actors legitimate and strong social trust exists, they perceive security governance as more effective. These results support arguments from recent debates considering resilience a key mechanism to ensure effective governance.Footnote8 Third, resilience has diverging effects on different dimensions of security governance breakdown. While resilience is more strongly correlated with national security perceptions, local security considerations are partly driven by other factors such as individuals’ economic resources. Thereby, the study adds to the literature on the micro foundations of security governance, stressing the diverging relevance resilience has for different dimensions of security perceptions.Footnote9

Building on original survey data from Libya and Tunisia and by utilizing multilevel modelling the study analyses what the EU considers as its “southern neighbourhood”, a region where both limited statehood and order contestations are pressing risks. Libya as a country where violent conflicts have been going on for several years and Tunisia as a country that has dealt comparatively peaceful with the changes of the Arab Spring allow for an ideal comparison to understand how resilience can help prevent governance breakdown.

The remainder of this article presents the theoretical background of the study and illustrates how societal resilience can help to prevent security governance breakdown. Then, the study introduces the data and the methodological approach. Subsequently, the article shows how the risks of limited statehood and order contestation affect Libya and Tunisia. The empirical analysis of the nexus between resilience and governance breakdown is the next step of the article. A concluding section sums up the main findings, underscores the research contributions, and points out avenues for future research.

Preventing governance breakdown through societal resilience

Effective governance involves the provision of binding rules as well as public goods and services.Footnote10 Governance breakdown occurs where governance is highly ineffective or completely absent, i.e. few if any binding rules exist and/or no or insufficient goods and service provisions take place (see introduction to this special issue). One crucial aspect of effective governance is security. Security governance is guaranteed by diverse constellations of formal and informal institutions including state and non-state actors providing social control and conflict resolution, in an attempt to promote peace in the face of threats arising from collective life.Footnote11 An essential component of effective security governance are the security perceptions of local populations. If people perceive security as insufficient this signals a breakdown of security governance. This also means that security perceptions and actual security related events do not necessarily overlap (see ). For example, people living in areas where no or only few violent events occur may nevertheless perceive security as insufficient. On the contrary, people living in areas where a lot of violence takes places may still perceive security as sufficient.

By concentrating on (in-)security perceptions this article provides insight on the subjective side of governance breakdown. Governance breakdown as the dependent variable occurs if local populations perceive security as insufficient. If individuals perceive security as insufficient, one cannot speak of effective security governance since from a citizen’s perspective goods and service provision in the security sector is not adequate, and rules do not foster citizens’ security. Subjectively experiencing governance breakdown can have severe political consequences as the example of mass emigration from Iraq due to fear and insecurity of local populations underscores.Footnote12 Analysing how resilience affects security perceptions offers insights on the opportunities and limits of preventing governance breakdown through resilience.

The study distinguishes between (in-)security perceptions on the local level and on the national level as two perspectives on security governance breakdown. Individuals may assess their local security situation as different from the security situation of a country as a whole.Footnote13 While individuals may perceive security as insufficient locally, they may consider the security situation of the country as much better or vice versa. By differentiating between local and national security perceptions the study produces insights on whether resilience is equally relevant for different dimensions of security governance breakdown. Thereby, the study speaks to recent debates on resilience as an important mechanism to ensure effective governance, and to micro level approaches to security governance.Footnote14

This article focuses on societal resilience as the adaptive capacity of societies, communities, and individuals to deal with opportunities and risks in a peacefully adaptive manner (see introduction to this special issue). Thereby, societal resilience includes the state as one governance actor among many, but particularly also non-state, and societal actors in a broader sense. Resilience gives societies the ability to fend off and cope with risks in a peaceful manner, thereby preventing a breakdown of governance.Footnote15 If societies are resilient, they are not only able to block off risks, but to develop coping mechanisms allowing them to deal with risks in the long run.

Three sources are of particular importance when building resilience: social trust, the legitimacy of governance actors, and the design of governance institutions.Footnote16 These three factors should lead to a higher degree of resilience and are key in ensuring that security governance breakdown does not occur, i.e. that local populations perceive security as sufficient.

Social trust is defined as “a cooperative attitude towards other people based on the optimistic expectation that others are likely to respect one’s own interests”.Footnote17 Social trust can be subdivided into three categories.Footnote18 First, individual trust refers to trust between individuals that know each other through regular face-to-face interactions. Second, group-based trust refers to trust within social groups and communities based on shared features of their members such as religion or ethnicity. Third, generalized trust is the most inclusive category of trust where individuals trust other people in general regardless of their ethnicity, religion, etc. Generalized trust is most relevant for societal resilience. Building on theories of governance and collective action, this article holds that if generalized trust prevails, people are more inclined to cooperate and overcome collective action problems.Footnote19 Thereby, social trust becomes key in strengthening the resilience of societies towards risks and in preventing governance breakdown. Through trust peoples’ security perceptions improve, because individuals experience that they do not have to fear threat or harm from other individuals. Generalized trust and cooperation decrease in-group and out-group biases producing larger inclusive social groups where people trust each other which enhances security perceptions. Thereby, social trust ensures that people perceive security as sufficient and prevents a breakdown of governance. In order to test whether social trust shows comparable correlations with different levels of governance breakdown, this article distinguishes between local and national (in-)security perceptions:

H1a: Greater generalized trust improves local security perceptions.

H1b: Greater generalized trust improves national security perceptions.

H2a: Greater legitimacy beliefs in governance actors improve local security perceptions.

H2b: Greater legitimacy beliefs in governance actors improve national security perceptions.

This article focuses on social trust and the legitimacy of governance actors as two key sources of resilience. The study does not include the design of governance institutions as a third source of resilience for two reasons. First, it is extremely challenging to grasp the concept of the design of governance institutions empirically. It would not be sufficient to include data on the degree of statehood or on the prevalence of public private partnerships (PPP) to assess the institutional design of governance arrangements to name just two examples. One would need detailed data on the legal framework statehood that PPPs are embedded in. Does the rule of law and mechanisms of checks and balances constrain statehood from becoming predatory? What are the legal rights and obligations of PPPs to contribute to effective governance? Such questions are relevant in order to analyse the extent to which an institutional design is adequate to contribute to resilience and ensure effective governance. Qualitative research is better able to address such questions and has produced relevant insight on the topic. Second, a related, but more practical reason is that adequate sub-national quantitative data to capture the design of governance institutions is not available for Tunisia and Libya as the country cases of interest to this study. Not taking the design of governance institutions into account is a limitation of this study when analysing the resilience-governance breakdown nexus. Nevertheless, by considering social trust and the legitimacy of governance actors as two main sources of resilience, this article allows for in-depth comparative insight on a subject where such evidence remains rare.

Data and methods

The study builds on two original surveys I conducted in Libya and Tunisia. Data collection in Libya took place in February 2020 and in Tunisia in December 2019. Both surveys were mobile phone surveys covering 1000 respondents each. The surveys ensured wide national coverage as respondents were drawn randomly from mobile phone subscriber lists for each country collecting data from male and female individuals aged 18 or older. Additionally, Libya and Tunisia are countries with high mobile phone usage making mobile phone surveys an ideal tool to reach a diverse sample. In Tunisia 124 people per 100 inhabitants had a mobile phone subscription in 2019, i.e. 1.24 subscriptions per inhabitant. In 2019 there were 95 subscriptions per 100 inhabitants in Libya.Footnote27 Moreover, the data covers all 24 Governorates of Tunisia and all 22 Shabiyas in Libya, i.e. all first level administrative units of both countries.Footnote28 Finally, due to the sensitive issue of the surveys and the challenging political circumstances in both countries mobile phone surveys made it easier and safer for individuals to participate compared to face-to-face surveys or other research methods requiring face-to-face interaction on the ground.Footnote29

Libya and Tunisia represent most different systems for a comparison of countries that took very different directions in several respects after the Arab Spring (see and ). Therefore, a comparison between both cases is particularly fruitful in producing generalizable insights on the resilience-governance breakdown nexus.Footnote30

Figure 1. Limited statehood in Libya and Tunisia. Source: Author’s illustration. Based on statehood data by Stollenwerk and Opper, The Governance and Limited Statehood Dataset.

Figure 2. Order contestation in Libya and Tunisia. Source: Author’s illustration. Based on ACLED data for protests and riots, https://acleddata.com.

To measure security governance breakdown as the dependent variable the study uses two proxy indicators. For capturing local perceptions of (in-)security, the survey asked: “In the past 12 months, how many times have you or any of your family felt unsafe walking in your neighborhood?”. To capture the national (in-)security perceptions of individuals, the survey asked: “All in all, how would you rate the security situation in Libya/Tunisia?”. These two questions allow for disaggregating the (in-)security perceptions of local populations to produce fine-grained insights on what characteristics of resilience fend off which aspect of security governance breakdown. Both indicators have been integrated as binary variables to run logistic regressions.

Societal resilience is a highly challenging concept for direct measurements. In order to arrive at robust empirical findings, the study captures the legitimacy of governance actors and social trust as two sources of resilience to approximate the degree of resilience one can expect to find in a society. To measure the legitimacy of the police as a key state institution relevant for security governance, the survey asks: “How much trust do you have in the police in Libya/Tunisia?”. To measure the legitimacy the EU enjoys as a key external governance actor, the survey asks: “How much trust do you have in the European Union (EU)?”.

Trust in governance actors is a valid proxy for legitimacy for at least two reasons. First, strong long-lasting trust in institutions is likely to develop into legitimacy beliefs towards these institutions.Footnote31 Without trust in institutions, legitimacy beliefs towards these institutions are impossible. Therefore, trust in institutions is key for legitimacy. Second, questions about the level of trust respondents have in governance actors are comparable across different sources of authority. As this study seeks to compare the legitimacy of state institutions with the legitimacy the EU enjoys as an external actor and their respective association with governance breakdown, trust-based questions allow for adequate comparisons.

The study measures the degree of social trust as another source of societal resilience trough a well-established indicator: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?”.Footnote32 Through this question it is possible to capture the degree of generalized trust as a main source of resilience.

The analysis includes limited statehood and order contestation as two key risk factors affecting Libya and Tunisia to understand how they correlate with individuals’ (in-)security perceptions. Both proxy indicators focus on the Shabiya level (Libya) and the Governorate level (Tunisia). The degree of limited statehood has been included through ACLED data capturing the number of events that challenge the state’s monopoly on force.Footnote33 Three event types have been included: 1. Non-state actor overtakes territory, 2. Government regains territory, 3. Non-violent transfer of territory. The models control for the degree of order contestation through ACLED data on the number of protests and riots. The mean data for limited statehood and order contestation have been included for the years 2016–2018 (Tunisia) and 2017–2019 (Libya). As changes in macro phenomena such as limited statehood and order contestation need time to affect individuals’ governance perceptions, a three-year time lag has been chosen to take this trickle-down effect into account. Moreover, the mean for three years is more robust against outlier years than a one-year snapshot.

The study controls for several other theoretically relevant variables. The models include the perception of democratic input-mechanisms through the question: “How free do you think elections are in Libya/Tunisia?”. Theories on democratization hold that free and fair elections allow citizens to have their voices heard and hold government accountable.Footnote34 This should decrease the likelihood of governance breakdown as citizens have a channel to voice their discontent and articulate their demands on the state and other governors for security. A variable capturing the degree of procedural justice has also been included through the question: “Do you think you are being treated fairly by the state in Libya/Tunisia?”. Arguments of procedural justice underline that if people feel that they are being treated fairly by the state, this should prevent governance breakdown as they do not need to fear abuse or discrimination.Footnote35 Economic well-being is another factor that is being controlled for by asking: “How satisfied are you with the financial situation of your household?”. The economic literature stresses that individuals with greater economic means should perceive governance as more effective as they can substitute lacking public service provision through their private resources.Footnote36 Well off citizens can buy security, e.g. through private security firms or living in gated communities.Footnote37 Additionally, the models control for a number of respondents’ socio-economic features: level of education, sex, and age.

To analyse the data, the study uses logistic two-level random intercept models for the binary dependent variables. The Shabiya/Governorate level variables represent the second level units while the individual level data represents the first level units. The random intercepts allow for taking the varying intercept levels between the second level units into account. Through multilevel models it is possible to consider the effects of micro level factors as well as macro level factors on the same dependent variable.Footnote38 This has the advantage that it is possible to analyse how macro factors such as limited statehood and order contestation are associated with individuals’ security perceptions. Both, from a theoretical and from a methodological perspective multilevel modelling is an ideal tool to answer the research question of this article. On a theoretical level the combination of explanatory factors on the individual and on the macro level allows for conclusions about which factors are most relevant in understanding governance breakdown. Methodologically, multilevel modelling minimizes omitted variables bias and tackles problems of spurious correlations allowing for more robust findings.

Risks in the EU’s southern neighbourhood: limited statehood and order contestation

Areas of limited statehood (ALS) and contested orders (CO) are two pressing risks in the EU’s southern neighbourhood (see introduction to this special issue). ALS mark such areas of a country where the state lacks the ability to make and implement rules and/or where its monopoly on force is incomplete. CO occur where one or multiple societal actors challenge the rules and principles according to which societies are being organized. ALS and CO constitute risks factors that increase the probability of witnessing a breakdown of security governance in the EU’s southern neighbourhood. In short, ALS and CO make it more likely that local populations perceive security as insufficient.

Limited statehood occurs in Tunisia and Libya. illustrates that both countries have featured statehood limitations for several decades. The figure shows the degree of statehood over time with higher values on the y-axis indicating stronger statehood. Limited statehood is the norm, not the exception in both countries. However, remarkable differences exist. Tunisia displays statehood limitations on a constant level. For all years of observation, the statehood score for Tunisia was 75. This is surprising for several reasons. First, in 1987 Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali took over power from Habib Bourguiba, which did not affect the degree of statehood in the country. Second, Ben Ali’s autocratic rule in Tunisia from 1987 to 2011 also did not affect the level of statehood. Third, after Ben Ali stepped down in 2011 and considering the turmoil related to the Arab Spring one could have expected the level of statehood in Tunisia to be affected by these developments. However, statehood remained at the 75 level. Tunisia displays statehood limitations that are significant, but also stable throughout its recent history, despite the substantial political and social changes the country witnessed.Footnote39

Libya displays a very different statehood pattern. Muammar Gaddafi was in power from 1969 to 2011, i.e. for most of the years displayed in . Between 1984 and 1996 the level of statehood increased under Gaddafi's autocratic rule from a score of 58 to a score of 75. However, after 1996 the degree of statehood decreased and came to a turning point in 2011 when Gaddafi was removed from power. Statehood in Libya reached its lowest level in 2014 with a score of 46, only slightly increasing to 48 in 2015. While statehood in Libya was fairly stable under Gaddafi’s rule, the Arab Spring and his removal from power significantly weakened Libya’s statehood.Footnote40 Comparing Tunisia and Libya it becomes clear that while both countries display statehood limitations, Libya has a much lower level of statehood than Tunisia.

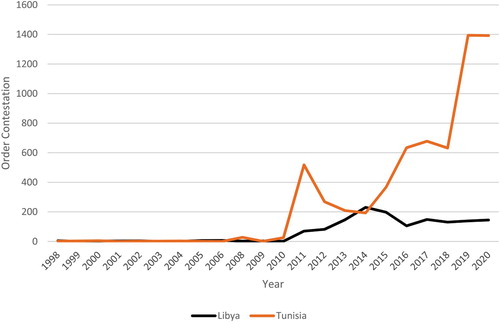

Order contestations as a second risk factor also affect Tunisia and Libya. Again, striking differences between the countries occur. indicates the degree of order contestation by showing the number of protests and riots per year for each country. Not surprisingly during the autocratic rule of Ben Ali in Tunisia and Gaddafi in Libya few if any protests and riots were recorded. This does not necessarily mean that they did not take place, i.e. that there were no contestations of the autocratic order, but data on such developments are mostly not available.

Tunisia and Libya were both affected by a steep rise in order contestations after 2010/2011 with a greater increase for Tunisia. In 2019 Tunisia reached its peak of order contestations with 1394 protests/riots taking place, while Libya experienced its peak in 2014 with 231 riots/protests occurring. Tunisia was and continues to be affected by stronger order contestations than Libya. Still, in Libya the interference of numerous external actors continues to contribute to order contestations. Some external actors like Turkey or the EU support the Government of National Accord (GNA) officially recognized by the United Nations. Other external actors like Russia or Egypt back Khalifa Haftar and the Libyan National Army (LNA).Footnote41 This led to a situation in which the political and social order in Libya is not only being challenged by various domestic actors, but that external actors, including the EU, fuel these order contestations through backing different sides.

Overall, Tunisia and Libya both display statehood limitations and order contestations. While Libya is much more affected by limited statehood, Tunisia is more disturbed by order contestations. In both countries the Arab Spring and developments since 2010/2011 marked a turning point. The rise in statehood limitations and order contestations increases the likelihood of experiencing a breakdown of security governance if societal resilience is not able to fend off such risks.

Analysing the resilience-governance breakdown nexus in Libya and Tunisia

To get an overview of the data shows the descriptive statistics for the variables included. It becomes obvious that in both samples the average respondent is male, aged 26–35 years (LBY)/34 years (TUN), and chose high school (LBY)/university (TUN) as their highest level of education. As such, the sample is slightly biased towards better educated male respondents who can afford a mobile phone, which should be kept in mind when interpreting the data.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics Libya and Tunisia.

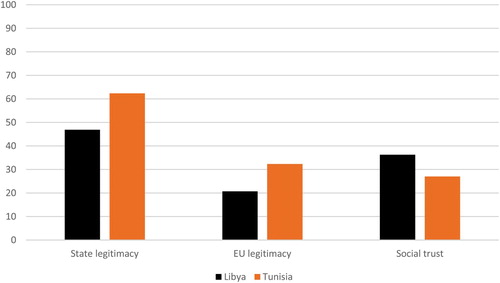

What is the level of resilience in Libya and Tunisia? provides an overview of social trust and the legitimacy of different governance actors as two key sources of resilience. Social trust and the legitimacy of governance actors give an indication of how much resilience one can expect to find.

Both countries possess some degree of societal resilience. Although there is plenty of room for improvement, Tunisia and Libya do not seem to be critically undermined by the risks affecting the countries. Looking at the legitimacy state institutions and the EU enjoy as two main politcial actors, it becomes obvious that state institutions enjoy broader legitimacy than the EU as an external actor. Given the autocratic rule both countries experienced in the past this is somewhat surprising, but a positive note for future initiatives to foster resilience. At the same time, the comparatively low levels of legitimacy for the EU as a relevant external actor signal that there is only a weak base of legitimacy to build on, potentially challenging EU efforts to help foster resilience. Both, the legitimacy of the state and the EU are stronger in Tunisia than in Libya. Yet, at the time of the surveys social trust was stronger in Libya than in Tunisia. This creates hopes that even in a highly conflict affected country with widespread limitations of statehood social trust might be an effective mechanism to deal with such risks. At the same time, the developments in Libya after 2010/2011 when compared to Tunisia suggest that state legitimacy might be the more powerful source of resilience than social trust (see also ). Tunisia with its higher levels of state legitimacy has been much less affected by violence and governance problems than Libya despite its higher levels of social trust. While resilience is not perfect in Tunisia or Libya, both countries have a solid resilience foundation to build on in order to prevent a breakdown of security governance.

Table 2. Multilevel models Tunisia and Libya.

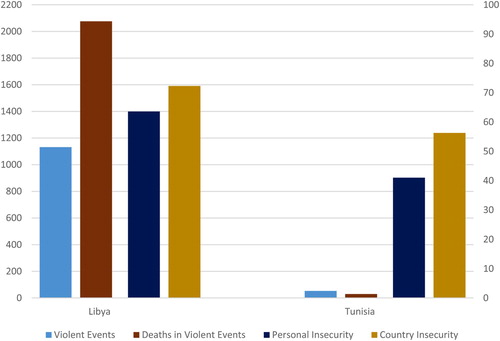

The security situation in Libya and Tunisia has been tense since the Arab Spring. Governance breakdown in the security sector has been a constant possibility in both countries for many years. illustrates the different levels of (in-)security one finds in both countries. The bar chart shows the percentage of people by country perceiving security as insufficient on the local level as well as on the country level. Moreover, the figure includes the absolute number of violent events and the number of deaths through violent events in both countries. Thereby, it is possible to compare perceived levels of (in-)security, i.e. the subjective side of governance breakdown with actual violent events and the number of deaths. underlines that (in-)security perceptions are a crucial aspect of security governance breakdown. Perceptions of (in-)security do only partly overlap with violent events and deaths capturing different dimensions of governance breakdown. For example, in Libya more than 2000 deaths through violent events were recorded in 2019. Still, this does not correlate with insecurity perceptions being equally high on the local and the country level. The situation in Tunisia is even more striking. Although there have been comparatively much fewer violent events and deaths, perceptions of insecurity are still high among Tunisians. This is particularly the case for their perception of the security situation in Tunisia as a whole. In both countries do people assess their personal security as much better than the security situation of the country in general.

Figure 4. Comparing aspects of (in-)security in Libya and Tunisia. Source: Author’s illustration. Note: Violent event and deaths data come from ACLED for the year 2019. The data for perceptions of (in-)security come from the original surveys in Libya and Tunisia evaluated in this study. The right hand y-axis shows the percentages of individuals feeling insecurity and the left hand y-axis absolute counts of violent events/deaths.

Overall, illustrates what a vital part of security governance breakdown the (in-)security perceptions of individuals are. (In-)security perceptions can drastically differ from actual security related events. Moreover, (in-)security perceptions can display stark differences depending on what the reference point is for individuals’ security perceptions, with people perceiving security as more effective on the local level than on the country level. Therefore, the perception-based side of security governance breakdown needs to be differentiated according to the local and the national level.

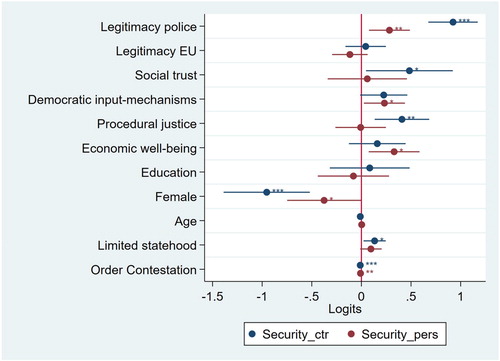

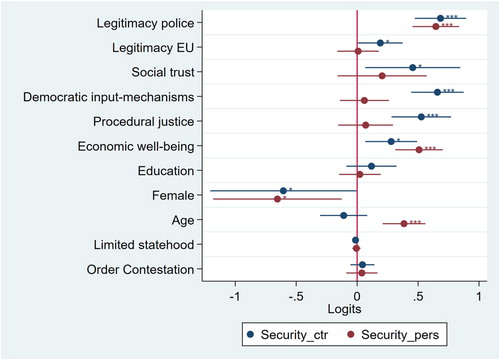

A multivariate analysis of how resilience and security perceptions interplay offers an in-depth assessment of the resilience-governance breakdown nexus. includes four models, where Model 1 contains the multilevel regressions for personal security perceptions in Tunisia as the dependent variable and Model 2 the country level security perceptions for Tunisia as the dependent variable. Model 3 and Model 4 replicate this for Libya. The models display the logits for the effect size and direction as well as robust standard errors in parentheses.

Resilience matters for preventing security governance breakdown. However, the individual sources of resilience are relevant to different degrees. State legitimacy is central to preventing governance breakdown. The legitimacy beliefs in core state institutions have a positive correlation with all levels of security perceptions across Tunisia and Libya. If citizens consider their state legitimate this becomes a key pillar of resilience and ensures effective governance.

The legitimacy belief in the EU as an external governance actor show significantly weaker correlations with security perceptions. Only in Libya does the EU’s legitimacy improve the perceived security of the country. This suggests that external actors are more relevant for preventing security governance breakdown in contexts where local populations are exposed to severe violence and where state institutions are so weak that they cannot be considered to be a sufficient source of security for citizens. The finding also signals that legitimacy is important for external actors, but that their ability to foster effective security governance might be limited. Although the EU is not the key security actor in Libya or Tunisia it is active in both countries trying to indirectly improve the security of local populations through rule of law reforms, fighting corruption, and empowering civil society no name just three examples.Footnote42 These results indicate that if the EU enjoys legitimacy, it can help prevent governance breakdown, but that its ability to do so is likely limited.

Social trust is another key source of resilience that helps in ensuring effective governance and citizens’ security. This is particularly the case for individuals’ assessment of the country’s security situation. When people trust each other, they are also more likely to evaluate the security situation in general as positive. This stresses the important role generalized trust plays for resilience and in turn for preventing governance breakdown. While all sources of resilience matter, the legitimacy of the state is most relevant, followed by social trust, and the legitimacy of the EU.

These results strongly support hypothesis 2a and 2b for the state as a governance actor and hypothesis 2b to a lesser extent for the EU as an external actor. Hypothesis 1a finds no support, while hypothesis 1b does. The findings underline the highly relevant role resilience plays in preventing a breakdown of governance. The results also highlight that it is important to differentiate between various dimensions of governance breakdown. Resilience seems to be more relevant for individuals’ assessment of the security situation in their country as a whole, rather than their local security conditions. Moreover, disentangling the sources of resilience points out that resilience can have different effects depending on the local context and the dimensions of governance breakdown considered.

Order contestation and limited statehood do not necessarily lead to governance breakdown in Libya and Tunisia. Limited statehood does not affect the security perceptions in Libya or Tunisia. The only exception is a slightly positive correlation between limited statehood and country level security perceptions in Tunisia. Still, this result should not be overstated due to the small effect size. One might speculate if in a previously autocratic setting like Tunisia ALS can improve the security perceptions of citizens as limited statehood eases the grip of state institutions on citizens and lowers the probability of oppressive state behaviour. Order contestations lower the security perceptions on the local and the country level in Tunisia, but not in Libya. Yet, the correlations are comparatively weak indicating that societal resilience is able to prevent stronger impacts. Tunisia has witnessed regular protests since the Arab Spring. As protests are sometimes coupled with clashes between various groups and violence of state institutions against protesters, this can lower Tunisians’ perception of security. Overall, the results stress that ALS and CO are not necessarily direct threats to local populations and do not automatically lead to a breakdown of governance. The findings indicate that in Tunisia and Libya societal resilience is able prevent a breakdown of governance despite the risks affecting both countries.

and display coefficient plots for the logits from . The blue dots represent the logits for security perceptions on the country level as the dependent variable and the red dots the logits for security perceptions on the local level as the dependent variable.

Both figures stress that the explanatory factors for (in-)security perceptions on the country and on the local level only partly overlap. This emphasizes the need to not only focus on security perceptions as an essential part of governance breakdown, but also the necessity to disentangle different dimensions of security perceptions.

In both Tunisia and Libya is resilience more relevant for citizens’ country level security perceptions than for their local security perceptions.

Additional factors deserve attention to understand peoples’ security perceptions and the subjective side of governance breakdown. Democratic input-mechanisms improve the security situation in Tunisia and Libya helping to prevent governance breakdown. While free and fair elections boost the security perceptions at the local level in Tunisia, they improve national security perceptions in Libya. This underscores arguments from democratization theory that free and fair elections can improve security governance, particularly in settings that experienced autocratic rule in the past. Yet, the results also show that elections are no silver bullet for preventing governance breakdown and might have varying effects depending on the specific context.

As procedural justice theory predicts, individuals who felt well treated by state institutions in Tunisia and Libya also considered the security situation of the country as more positive. While the resilience of societies is essential in preventing governance breakdown, fair and inclusive state institutions are another key factor in guaranteeing effective governance.

Socio-economic features of respondents matter for their security assessments. Respondents with greater economic means also felt more secure. This was most strongly the case for local and country level security perceptions in Libya, but also for the local security perceptions in Tunisia. This supports economic theories suggesting that citizens do ensure their security through private resources, if security is not delivered by the state. This happens through private security companies or living in gated communities to name just two examples.Footnote43 Another striking finding is that women were much more likely to suffer from a breakdown of governance than men. This underscores the important role gender aspects play in understanding for whom governance services are available and why. As women experience systematically less security than men the question which social groups suffer most from governance breakdown in the EU’s neighbourhood deserves more attention.

Conclusion

To what extent does societal resilience help prevent governance breakdown? By comparing evidence from Libya and Tunisia the study finds that societal resilience is key in averting governance breakdown in what the EU considers as its “southern neighbourhood”. Most relevant is the legitimacy of state institutions in ensuring that governance does not break down. Social trust is another essential resilience factor guaranteeing effective security governance. The legitimacy of the EU as an external actor can also help to prevent governance breakdown, although to a lesser extent. This suggests that not all sources of resilience have the same impact with state legitimacy being most relevant, followed by social trust, and the EU’s legitimacy. The analysis also shows that areas of limited statehood and contested orders as two pressing risks in Libya and Tunisia do not necessarily lead to governance breakdown, if resilience is strong enough to fend off such risks.

With these findings, this article contributes to understanding the resilience-governance breakdown nexus in several respects. First, on a theoretical level it demonstrates that the legitimacy of governance actors and social trust are two main sources of resilience able to prevent a breakdown of governance in areas where statehood is limited and order contestation occurs. Thereby, the study supports recent arguments about resilience being a key mechanism for ensuring peaceful change and effective governance.Footnote44 Moreover, the findings contradict arguments from the failed states literature that weak statehood equals chaos and insecurity.Footnote45 Instead, the results underscore claims that effective governance is possible even in areas where statehood is limited.Footnote46 By considering (in-)security perceptions as an essential aspect of governance breakdown, the article highlights that resilience is more important for individuals’ assessment of the country wide security situation, than of their personal security. Taking individuals’ security perceptions seriously is key for understanding and preventing governance breakdown. Thereby, this article adds new insights to the growing literature on the micro foundations of security governance.Footnote47

Second, empirically the study shows that resilience is highly relevant in Tunisia and Libya to prevent governance breakdown. Although some studies have demonstrated for individual cases how relevant resilience is for coping with crises, empirical evidence on the resilience-governance breakdown nexus remains rare.Footnote48 By comparing Tunisia and Libya utilizing large-scale survey data this article does not only provide comparative empirical evidence on how resilience affects governance breakdown, but also helps to generalize these findings for the EU’s southern neighbourhood more broadly. Additionally, data on resilience and security governance breakdown is often hard to get.Footnote49 This is particularly the case for countries like Tunisia and Libya that were under autocratic rule for decades. Through the original survey data evaluated the article underscores how strongly resilience and governance breakdown are correlated in the EU’s neighbourhood.

Third, this study has policy implications for external actors seeking to strengthen resilience, most notably the EU. If the EU wants to help build societal resilience in what it considers to be its neighbourhood, it is well-advised to focus on social trust and the legitimacy of governance actors as two essential sources of resilience. Resilience policies should not only focus on state actors but also include non-state actors that enjoy legitimacy among local populations and who are in turn able to help build social trust between individuals. Moreover, external actors need to take the security perceptions of local populations seriously. As security perceptions represent a vital part of effective governance no external governance involvement can expect to be successful when ignoring citizens’ governance perceptions and expectations. Finally, the negative externalities engagements of external actors can have for societal resilience have to be kept in mind. External actors can act as resilience builders, but also as resilience spoilers if their actions undermine social trust, the legitimacy of governance actors, and the effectiveness of governance institutions.

Despite the contributions of this study, limitations remain that indicate avenues for future research. First, the article underscored how relevant generalized trust is as a source of resilience. Nevertheless, future studies should identify the exact thresholds of trust that are necessary in order to arrive at resilience. Is generalized trust always necessary or might group-based trust be sufficient in some instances? Second, by considering the legitimacy of state institutions and the EU the study focused on two governance actors of relevance. Still, non-state actors, such as NGOs or other external actors, should be considered to understand whether their legitimacy also helps in preventing governance breakdown. Third, the study evaluated original cross-sectional data for areas where such data remains rare. However, the results should be considered in correlational terms rather than from a strongly causal perspective. Therefore, assessing the findings with longer time series data or experimental methods would further underline the causal mechanisms at play. Finally, as this article focused on security as one crucial dimension of governance, future studies could assess whether the arguments and findings extend to other governance dimensions. Is resilience equally relevant for preventing governance breakdown in sectors like public health or education?

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eric Stollenwerk

Eric Stollenwerk is a Research Fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) in Hamburg, Germany. He is also an Affiliated Senior Researcher at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO), Norway. He obtained his PhD from the Freie Universität Berlin, Germany and has been a guest researcher at Stanford University and the Peace Research Institute Oslo. His work lies at the intersection of international relations, comparative politics, and peace and conflict studies. His current research focuses on the legitimacy of state and non-state actors, security perceptions of local populations, and societal resilience. He has published his work among others in the Annual Review of Political Science, the Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, Terrorism and Political Violence, and Daedalus.

Notes

1 Boubekeur, “Islamists, Secularists and Old Regime Elites in Tunisia”; Schumacher and Schraeder, “The Evolving Impact of Violent Non-state Actors on North African Foreign Policies”.

2 Chandler, “Resilience and Human Security”; Juncos, “Resilience as the New EU Foreign Policy Paradigm”.

3 Korosteleva, “Reclaiming Resilience Back”; Pospisil and Kühn, “The Resilient State”; Tocci, “Resilience and the Role of the European Union”.

4 High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, “Shared Vision, Common Action”.

5 Tocci, “Resilience and the Role of the European Union”; Stollenwerk, Börzel, and Risse, “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU's Neighbourhood”, Bargués and Morrilas, “From democratization to fostering resilience”.

6 See Rotberg, When States Fail.

7 Börzel, Risse and Draude, “Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood”; Schmelzle and Stollenwerk, “Virtuous or Vicious Circle?”.

8 See e.g. Korosteleva, “Reclaiming Resilience Back”; Tocci, “Resilience and the Role of the European Union”; Stollenwerk, Börzel, and Risse, “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU's Neighbourhood”.

9 Glawion, The Security Arena in Africa; Stollenwerk “Securing Legitimacy”.

10 Börzel, Risse, and Draude, “Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood”.

11 Dupont, Grabosky, and Shearing, “The Governance of Security in Weak and Failing States”; see also Schröder, “Security”.

12 Sirkeci, “War in Iraq”.

13 Glawion, The Security Arena in Africa.

14 See e.g. Chandler, “Resilience and Human Security”; Glawion, The Security Arena in Africa.

15 Stollenwerk, Börzel, and Risse, “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU's Neighbourhood”; Chandler, “Resilience and Human Security”; Korosteleva, “Reclaiming Resilience Back”; Burnell and Calvert “The Resilience of Democracy”.

16 See Stollenwerk, Börzel, and Risse, “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU's Neighbourhood” a graphical illustration of the conceptual framework guiding this article and the entire special issue.

17 Draude, Hölck, and Stolle, “Social Trust”, 354.

18 Draude, Hölck, and Stolle, “Social Trust”; Stollenwerk, Börzel, and Risse, “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU's Neighbourhood”.

19 Börzel and Risse, “Dysfunctional State Institutions”; Ostrom, Governing the Commons.

20 Gilley, The Right to Rule; Risse and Stollenwerk, “Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood”.

21 Schmelzle, Politische Legitimität und zerfallene Staatlichkeit; Schmelzle and Stollenwerk, “Virtuous or Vicious Circle?”.

22 Levi, Sacks, and Tyler, “Conceptualizing Legitimacy”; Schmelzle and Stollenwerk, “Virtuous or Vicious Circle?”.

23 See e.g. Nickerson, “Confirmation Bias”.

24 See Krasner and Risse, “External Actors, State-Building, and Service Provision in Areas of Limited Statehood”; Schmelzle and Stollenwerk, “Virtuous or Vicious Circle?”.

25 Dandashly, “EU Democracy Promotion”; Gaub, “The EU and Libya”.

26 See Korosteleva, “Reclaiming Resilience Back”; Tocci, “Resilience and the Role of the European Union”; Stollenwerk, Börzel, and Risse, “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU's Neighbourhood”.

27 See cellular subscriptions (per 100 people) – Libya, Tunisia | Data (worldbank.org).

28 The list of Shabiyas in Libya is based on the Shabiya limits of 2007. As reforms of administrative units in Libya after 2007 have only partly been implemented and violent fighting has put the relevance of the new Shabiya limits for local populations in doubt, the 2007 Shabiya limits are considered more relevant. Due to an insufficient number of respondents the multilevel analysis includes 21 Shabiyas for Libya.

29 See Firchow and Mac Ginty, “Including Hard-to-Access Populations”.

30 Przeworski and Teune, The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry.

31 Gilley, The Right to Rule; von Haldenwang, “Measuring Legitimacy”.

32 See e.g. Knack and Keefer, “Does Social Capital Have an Economic Payoff?”.

33 Raleigh et al., “Introducing ACLED”.

34 Bratton, “Citizen Perceptions of Local Government Responsiveness”; Chu et al., “Public Opinion”.

35 Levi, Sacks, and Tyler, “Conceptualizing Legitimacy”; Tyler, Why People Obey the Law.

36 Lee, Walter-Drop, and Wiesel, “Taking the State (Back) Out?”.

37 Abrahamsen and Williams, “Securing the City”; Landmann and Schönteich, “Urban Fortresses”.

38 Hox, Multilevel Analysis; Wenzelburger, Jäckle, and König, Weiterführende Statistische Methoden.

39 See also O’Brien, “The Primacy of Political Security”.

40 See also Cross and Sorens, “Arab Spring Constitution-making”.

41 See e.g. Lefèvre, “The pitfalls of Russia's growing influence in Libya”.

42 Dandashly, “EU Democracy Promotion”; Gaub, “The EU and Libya”.

43 Abrahamsen and Williams, “Securing the City”; Landmann and Schönteich, “Urban Fortresses”.

44 See e.g. Korosteleva, “Reclaiming Resilience Back”; Tocci, “Resilience and the Role of the European Union”; Stollenwerk, Börzel, and Risse, “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU's Neighbourhood”.

45 Rotberg, When States Fail.

46 Börzel, Risse and Draude, “Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood”; Schmelzle and Stollenwerk, “Virtuous or Vicious Circle?”.

47 Glawion, The Security Arena in Africa; Stollenwerk “Securing Legitimacy”.

48 Joseph, “The EU in the Horn of Africa”; Natali, “Syria's Spillover on Iraq”; Kakachia, Legucka, and Lebanidze, “Can the EU's new global strategy make a difference?”; Ozcurumez, “The EU's effectiveness in the Eastern Mediterranean migration quandary”.

49 Owen, “Measuring Human Security”; Sherrieb, Norris, and Galea, “Measuring Capacities for Community Resilience”.

Bibliography

- Abrahamsen, Rita, and Michael C. Williams. “Securing the City: Private Security Companies and Non-State Authority in Global Governance.” International Relations 21, no. 2 (2007): 237–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117807077006.

- Bargués-Pedreny, Pol. “Resilience is “Always More” Than Our Practices: Limits, Critiques, and Skepticism About International Intervention.” Contemporary Security Policy 41, no. 2 (2020): 263–286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1678856.

- Bargués, Pol, and Pol Morillas. "From Democratization to Fostering Resilience: EU Intervention and the Challenges of Building Institutions, Social Trust, and Legitimacy in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Democratization (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1900120.

- Börzel, Tanja Anita, and Thomas Risse. “Dysfunctional State Institutions, Trust, and Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Regulation & Governance 10, no. 2 (2016): 149–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12100.

- Börzel, Tanja Anita, Thomas Risse, and Anke Draude. “Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood: Conceptual Clarifications and Major Contributions of the Handbook.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, Tanja Anita Börzel, and Anke Draude, 3–28. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Boubekeur, Amel. “Islamists, Secularists and Old Regime Elites in Tunisia: Bargained Competition.” Mediterranean Politics 21, no. 1 (2016): 107–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2015.1081449.

- Bratton, Michael. “Citizen Perceptions of Local Government Responsiveness in Sub-Saharan Africa.” World Development 40, no. 3 (2012): 516–527. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.07.003.

- Burnell, Peter, and Peter Calvert. “The Resilience of Democracy: An Introduction.” Democratization 6, no. 1 (1999): 1–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510349908403594.

- Chandler, David. “Resilience and Human Security: The Post-Interventionist Paradigm.” Security Dialogue 43, no. 3 (2012): 213–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010612444151.

- Chu, Yun-Han, Michael Bratton, Marta Lagos, Sandeep Shastri, and Mark Tessler. “Public Opinion and Democratic Legitimacy.” Journal of Democracy 19, no. 2 (2008): 74–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2008.0032.

- Cross, Ester, and Jason Sorens. “Arab Spring Constitution-Making: Polarization, Exclusion, and Constraints.” Democratization 23, no. 7 (2016): 1292–1312. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2015.1107719.

- Dandashly, Assem. “EU Democracy Promotion and the Dominance of the Security–Stability Nexus.” Mediterranean Politics 23, no. 1 (2018): 62–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2017.1358900.

- Draude, Anke, Lasse Hölck, and Dietlind Stolle. “Social Trust.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, Tanja Anita Börzel, and Anke Draude, 353–374. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Dupont, Benoit, Peter Grabosky, and Cifford Shearing. “The Governance of Security in Weak and Failing States.” Criminal Justice 3, no. 4 (2003): 331–349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/146680250334001.

- Firchow, Pamina, and Roger Mac Ginty. “Including Hard-to-Access Populations Using Mobile Phone Surveys and Participatory Indicators.” Sociological Methods & Research 49, no. 1 (2020): 133–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124117729702.

- Gaub, Florence. “The EU and Libya and the Art of the Possible.” The International Spectator 49, no. 3 (2014): 40–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2014.937093.

- Gilley, Bruce. The Right to Rule: How States Win and Lose Legitimacy. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

- Glawion, Tim. The Security Arena in Africa: Local Order-Making in the Central African Republic, Somaliland, and South Sudan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe. A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign And Security Policy. Brussels, 2016.

- Hox, Joop J. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Joseph, Jonathan. “The EU in the Horn of Africa: Building Resilience as a Distant Form of Governance.” Journal of Common Market Studies 52, no. 2 (2014): 285–301. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12085.

- Juncos, Ana E. “Resilience as the New EU Foreign Policy Paradigm: a Pragmatist Turn?” European Security 26, no. 1 (2017): 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2016.1247809.

- Kakachia, Kornely, Agnieszka Legucka, and Bidzina Lebanidze. Can the EU’s new Global Strategy make a Difference? Strengthening Resilience in the Eastern Partnership Countries." Democratization (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1918110.

- Knack, Stephen, and Philip Keefer. “Does Social Capital Have an Economic Payoff? A Cross-Country Investigation.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112, no. 4 (1997): 1251–1288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300555475.

- Korosteleva, Elena A. “Reclaiming Resilience Back: A Local Turn in EU External Governance.” Contemporary Security Policy 41, no. 2 (2020): 241–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1685316.

- Krasner, Stephen D., and Thomas Risse. “External Actors, State-Building, and Service Provision in Areas of Limited Statehood: Introduction.” Governance 27, no. 4 (2014): 545–567. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12065.

- Landmann, Karina, and Martin Schönteich. “Urban Fortresses: Gated Communities as a Reaction to Crime.” African Security Review 11, no. 4 (2002): 71–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10246029.2002.9628147.

- Lefèvre, Raphaël. The pitfalls of Russia’s growing influence in Libya. The Journal of North African Studies 22, no. 3 (2017): 329–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2017.1307840.

- Lee, Melissa M., Gregor Walter-Drop, and John Wiesel. “Taking the State (Back) Out? A Macro-Quantitative Analysis of Statehood and the Delivery of Collective Goods and Services.” Governance 27, no. 4 (2014): 635–654. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12069.

- Levi, Margaret, Audrey Sacks, and Tom Tyler. “Conceptualizing Legitimacy, Measuring Legitimating Beliefs.” American Behavioral Scientist 53, no. 3 (2009): 354–375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764209338797.

- Natali, Denise. “Syria's Spillover on Iraq: State Resilience.” Middle East Policy 24, no. 1 (2017): 48–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/mepo.12251.

- Nickerson, Raymond S. “Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises.” Review of General Psychology 2, no. 2 (1998): 175–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175.

- O'Brien, Thomas. “The Primacy of Political Security: Contentious Politics and Insecurity in the Tunisian Revolution.” Democratization 22, no. 7 (2015): 1209–1229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2014.949247.

- Ostrom, Elinor. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Owen, Taylor. “Measuring Human Security: Methodological Challenges and the Importance of Geographically Referenced Determinants.” In Environmental Change and Human Security: Recognizing and Acting on Hazard Impacts, edited by Peter H. Liotta, David A. Mourat, William G. Kepner, and Judith Lancaster, 35–64. Amsterdam: Springer, 2008.

- Ozcurumez, Saime. "The EU's Effectiveness in the Eastern Mediterranean Migration Quandary: Challenges to Building Societal Resilience." Democratization (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1918109.

- Pospisil, Jan, and Florian P. Kühn. “The Resilient State: New Regulatory Modes in International Approaches to State Building?” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 1 (2016): 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1086637.

- Przeworski, Adam, and Henry Teune. The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1970.

- Raleigh, Clionadh, Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre, and Joakim Karlsen. “Introducing ACLED-Armed Conflict Location and Event Data.” Journal of Peace Research 47, no. 5 (2010): 651–660. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343310378914.

- Risse, Thomas, and Eric Stollenwerk. “Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Annual Review of Political Science 21, no. 1 (2018): 403–418. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041916-023610.

- Rotberg, Robert I., ed. When States Fail: Causes and Consequences. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

- Schmelzle, Cord. Politische Legitimität und zerfallene Staatlichkeit. Vol. 80 of Theorie und Gesellschaft, edited by Jens Beckert, Rainer Forst, Wolfgang Knöbl, Frank Nullmeier, and Shalini Randeria. Frankfurt/New York: Campus, 2015.

- Schmelzle, Cord, and Eric Stollenwerk. “Virtuous or Vicious Circle? Governance Effectiveness and Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12, no. 4 (2018): 449–467. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2018.1531649.

- Schröder, Ursula. “Security.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, Tanja Anita Börzel, and Anke Draude, 375–393. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Schumacher, Michael J., and Peter J. Schraeder. “The Evolving Impact of Violent Non-State Actors on North African Foreign Policies During the Arab Spring: Insurgent Groups, Terrorists and Foreign Fighters.” The Journal of North African Studies 24, no. 4 (2019): 682–703. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2018.1525014.

- Sherrieb, Kathleen, Fran H. Norris, and Sandro Galea. “Measuring Capacities for Community Resilience.” Social Indicators Research 99, no. 2 (2010): 227–247. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9576-9.

- Sirkeci, Ibrahim. “War in Iraq: Environment of Insecurity and International Migration.” International Migration 43, no. 4 (2005): 197–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2005.00338.x.

- Stollenwerk, Eric. “Measuring Governance and Limited Statehood.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, Tanja Anita Börzel, and Anke Draude, 106–127. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018a.

- Stollenwerk, Eric. “Securing Legitimacy? Perceptions of Security and ISAF’s Legitimacy in Northeast Afghanistan.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12, no. 4 (2018b): 506–526. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2018.1504855.

- Stollenwerk, Eric, and Jan Opper. The Governance and Limited Statehood Dataset. 2017. https://www.sfb-governance.de/en/publikationen/daten/_elemente_startseite/3spalten/datensaetze_quantitativ/a1_stollenwerk_opper.html.

- Stollenwerk, Eric, Tanja A. Börzel, and Thomas Risse. “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU’s Neighbourhood: Introduction to the Special Issue." Democratization (2021): this special issue.

- Tocci, Nathalie. “Resilience and the Role of the European Union in the World.” Contemporary Security Policy 41, no. 2 (2020): 176–194. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1640342.

- Tyler, Tom R. Why People Obey the Law. New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1990.

- Von Haldenwang, Christian. “Measuring Legitimacy – New Trends, Old Shortcomings?” German Development Institute Discussion Paper 18/2016 (2016): 1–44.

- Wenzelburger, Georg, Sebastian Jäckle, and Pascal König. Weiterführende Statistische Methoden für Politikwissenschaftler: Die Anwendungsbezogene Einführung mit STATA. München: Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2014.