ABSTRACT

I present a business case for democracy, focusing on the impact of democracy on economic growth. This relationship is widely studied, and results have been less robust for growth than many other development outcomes such as literacy or infant mortality. I discuss four factors pertaining to data quality and modelling choices, suggesting that several previous studies have underestimated the growth-benefits of democracy. I further discuss the relationships between democracy and economic crises and variation in economic performance. By mitigating abysmal economic outcomes and ensuring more stable performance, democracy is generally of benefit to risk-averse entrepreneurs, investors, workers, and consumers alike.

Introduction

In this article, I make a “business case” for democracy by summarizing and critically evaluating the state of the existing evidence on regime type and growth and by presenting new evidence drawing on recent data with time series extending back to the nineteenth century. When making this case, I consider how expected growth rates, but also growth volatility and frequency of short-term crises, depend on regime type. While these outcomes have often been studied and discussed in isolation, there are good reasons for considering them together when making an overall evaluation of how democracy influences the economic situations of firms, investors, workers, and consumers:

Market demand and individual incomes depend on numerous factors, but they are strongly correlated with a country’s average production and income levels. Sustained growth in GDP per capita over time, everything else equal, thus brings rewards both to firms and consumers. If democracy enhances growth, this would be a core component of any business case for democracy. Yet, most individuals are risk averse. Viewed from the perspective of, say, a risk averse investor or consumer, both the expected income and the uncertainty surrounding future income growth matter for expected utility. If risk averse consumers or other economic actors should evaluate political systems according to their economic effects, they would presumably consider both their expected (average) effects and how they mitigate variation, especially “downside risks” that accompany economic crises.Footnote1 Hence, I here take an integrated approach when considering the effects of democracy on growth.

But, let us first take one step back and ask a tough question: What would you pick if you had to choose between freedom and bread? Most people – I suspect – would choose bread. Several social scientists and others (including autocrats) have suggested that a similar trade-off, at the macro-level, pertains to the choice between autocracy and democracy. Democracy ensures more extensive political rights and better protection of liberties for citizens, but autocracy is often presumed to enable development-minded leaders to push through different policies and reforms that enhance growth.

A stylized version of this argument goes as follows: Development-minded autocrats can initiate large-scale infrastructure projects with fewer constraints from partisan wrangling and opposing interest groups. The same absence of constraints also means they can respond more rapidly and forcefully to looming crisis with different policy instruments, potentially mitigating large drops in GDP per capita. They can also take a longer time horizon than their myopic citizens and channel resources towards public and private savings rather than consumption, thereby achieving higher investment rates than democracies. Political rights and civil liberties are, supposedly, luxury goods to be afforded sometime in the future once economic development has been achieved. Democracy and freedom may have intrinsic normative value, but – the argument goes – ensuring economic development is more important. Advocates of this argument often point to the development experiences of a handful of autocracies, with the extraordinarily high and quite stable growth of China after its economic reforms in the late 1970s and 80s being a prime example.

Nevertheless, the trade-off between democracy and development is far from evident. Whether democracy helps or hinders economic development is, ultimately, an empirical question. As Amartya Sen noted more than twenty years ago:

It is sometimes claimed that the denial of [political and civil] rights helps to stimulate economic growth and is “good” for economic development. Some have even championed harsher political systems – with denial of basic civil and political rights – for their alleged advantage in promoting economic development. This thesis … is sometimes backed by some fairly rudimentary empirical evidence.Footnote2

Despite this evidence to the contrary, the idea that autocracies have development advantages remains widely asserted by policy makers (also from developed democracies), journalists, public intellectuals, and some researchers.Footnote9 One likely reason is the stellar economic performances of certain, high-profile autocracies. In the 1930s (and beyond), Hitler’s building of the German Autobahn and Stalin’s 5-year plans received widespread admiration. Aided by regime propaganda and inflated statistics, these experiences were perceived as impressive economic accomplishments pushed through by “strong leaders”.Footnote10 After WWII, the rapid growth of export manufacturing in South Korea and Taiwan, fuelled by high savings rates and creative industrial policies, were widely regarded as authoritarian success stories.Footnote11 More recently, China’s industrialization and fast growth has captivated both policy makers and academics, spurring talk of an authoritarian Chinese developmental model.Footnote12

Hence, there is a continued need to state the “business case” for democracy. This is perhaps especially relevant today, as authoritarian practices are replacing democratic governance in several large countries, from Brazil to India to Poland to Turkey,Footnote13 and where democratic principles have been under pressure even in long-standing democracies such as the United States. In the following, I review existing evidence and point to often overlooked methodological issues that indicate a clearer “business case” for democracy than what its detractors believe. I draw two important conclusions:

First, I propose that – the mixed results in the large, statistical literature notwithstanding – democracy likely carries a stronger positive relationship with economic growth than often concluded. Existing studies underappreciate the relationship due to seemingly technical matters such as controlling for important mechanisms through which democracy enhances growth and omitting autocracies with poor growth records. Moreover, autocracies often report biased data that exaggerate their performances. This pattern has received recent attention with the likely under-reporting of COVID19 deaths in autocracies from China to Russia to Iran,Footnote14 but pertains also to GDP statistics.

Second, I highlight how democracy works as a safety-net for avoiding the worst possible economic outcomes. Autocracies make up a heterogeneous group of countries,Footnote15 and this heterogeneity is reflected in their economic policies and performances.Footnote16 While some uncertainty surrounds the “average” relationship, democracies clearly have lower variance in their economic performances than autocracies, and are better at avoiding economic crises. Hence, democracy is a less risky proposition for citizens and investors alike.

To substantiate the latter point, I present descriptive patterns and results from analyses conducted on extensive data material. Autocracies dominate among the worst economic performances (at various points in modern history after 1800) and experience more frequent short-term crises. Further, they experience far more variation in growth patterns, both across and within countries, from year-to-year. While these relationships have been proposed by previous studies, these studies have typically relied on short time series and data from recent decades, used democracy measures with well-known reliability and validity issues, and failed to account for potential confounders by not controlling for, e.g. country-fixed effects. My results, from different model specifications that use new democracy measures and data extending back to the early nineteenth century, should mitigate any lingering doubt that democracies are superior at mitigating growth volatility and the risk of experiencing economic crisis.

Why democracy is better for business than it first appears

Plausible theoretical arguments point in different directions concerning the economic benefits of democracy relative to autocracy. The ability of autocrats to ignore demands from short-sighted, consumption-seeking electorates – and bulldoze over various interest groups – should increase savings (and thus investment) rates and allow for efficiency-enhancing economic reforms to be pushed through without delays.Footnote17 This should boost growth in autocracies. Conversely, democratic leaders being accountable to wider constituencies strengthens incentives to spend on productivity-enhancing public goods and services that benefit the many and dis-incentivize predatory behaviour.Footnote18 Further, an open and inclusive environment for critical debate and free exchange of ideas increases the dissemination of new technologies into and within democracies. Hence, democracies observe faster technological change, a primary driver of long-term growth.Footnote19

Early statistical studies mostly report a null relationship or that democracy is bad for growth, whereas more recent studies typically find either a positive or non-robust relationship.Footnote20 Hence, a “democracy advantage” in generating growth looks more plausible today than a few decades ago. Still, also several recent studies find a non-significant relationship. Why do even recent studies drawing on extensive data material find varying results? In part, these differences stem from several methodological choices and issues. When properly accounting for them, I propose, the evidence is even stronger for a positive relationship between democracy and growth:

First, it takes considerable time – up to a decade – before the economic benefits of democratization are realized.Footnote21 Economic growth seems to decline initially after democratization, before it increases, and then peaks and stabilizes after about three years.Footnote22 It takes time from a regime changes to the new leaders legislating new economic policies, but it also takes time for economic actors to respond to these policy changes and adjust investments and labour supply. Hence, analyses measuring democracy and growth with a time lag of, say, 3–5 years, are more credible than analyses measuring them concurrently, and democracy’s estimated growth-benefit is typically larger in the former specifications.Footnote23

Second, control variable selection matters. For example, Acemoglu et al. discuss the importance of taking into account past dynamics in income, and report a positive relationship between democracy and growth once doing so.Footnote24 Other statistical studies arguably “over-control” by holding constant factors that enhance growth, but which are also affected by democracy.Footnote25 This practice of “blocking off” relevant indirect effects has led researchers to under-estimate the growth benefits of democracy. A meta-analysis of 84 studies substantiates this point, finding that the studies that control for several policy or outcome variables, including inflation, economic freedom, education, and political instability, are less likely to find a positive relationship.Footnote26

Third, democracy measurement may influence results.Footnote27 For instance, the dichotomous measure used in the most cited study on the topic (by Przeworski and colleagues) systematically underestimates democracy’s effect on growth.Footnote28 Further, taking into account a country’s past experiences with democratic rule, in addition to the current level, strengthens the positive link with growth.Footnote29 Most studies on the topic do not use measures that capture the influence of regime history.

Fourth, dictatorships more often fail to report or, alternatively, report less credible economic statistics than democracies.Footnote30 Missing GDP data is more common for autocracies, especially low-performing ones such as North Korea under Kim Jong Il or Afghanistan under the Taliban.Footnote31 Even when data are reported, systematic errors may lead researchers to underestimate the effect of democracy on growth. Politicized statistical agencies, and national and local leaders’ expectations (or demands) that bureaucrats create advantageous production statistics, were features of the Soviet Union’s planned economy.Footnote32 A more recent example of manipulated GDP numbers is China. Researchers have estimated that China’s GDP growth was 1.7 percentage points below official numbers from 2008 to 2016, possibly because “local governments are rewarded for meeting growth and investment targets, [and therefore] have an incentive to skew local statistics”.Footnote33 Differences in growth rates between GDP and production or consumption of electricity also indicate manipulated Chinese GDP numbers – divergences are higher in years of turnover in party or government leadership at the province level, suggesting that GDP data are manipulated for political reasons.Footnote34 The Soviet and Chinese examples are not exceptions. Using satellite nighttime light data as a yardstick, one study estimated that autocracies systematically exaggerate their growth data, and the bias is sizeable: “Annual GDP growth rates are estimated to be overstated by 0.5–1.5 percentage points in the statistics that dictatorships report to the World Bank”.Footnote35 Another recent study using similar data, and which accounts for alternative explanations such as differences in statistical capacity or differential rates of electrification, finds that “the most authoritarian governments inflate yearly GDP growth by a factor of 1.15–1.3 on average”.Footnote36

In sum, the observed relationship between democracy and growth depends on statistical modelling choices and data quality. A conservative conclusion is that the relationship between democracy and growth is not robust. While true, this conclusion should come with caveats: Many plausible statistical models do find a positive and rather sizeable relationship. This finding has become more prevalent over the last 15 years,Footnote37 as sample sizes, data quality, and methodological sophistication have improved. These patterns indicate that a positive relationship may still be our “best guess”.

Democracy as a safety-net: patterns in the data

The discussion above notwithstanding, the democracy-growth relationship lacks in robustness. One important explanation is that growth performances are very heterogeneous for regimes with similar levels of democracy, especially towards the autocratic end of the scale. Hence, analysis on the “average relationship” between democracy and growth masks substantial heterogeneity. Put differently, some autocracies display very high growth, at least for some time, whereas others preside over stagnant or even contracting economies. This observation has been made before in different studies.Footnote38

However, there are limitations to these existing studies, suggesting some caution against accepting the observed correlations as strong evidence of a general, causal effect. Conducting a comprehensive search on journal articles published after 2000, with country/country-year as unit and 60 or more countries included, I identified 14 studies on democracy and growth volatility or related outcomes such as crises, growth reversals, or growth accelerations and decelerations. 12 articles identify a significant association between autocracy and high-variability outcomes. Yet, there are three recurring issues with these studies.

First, work on the average relationship between democracy and growth shows that estimates depend on the time series, and inclusion of data from a particular decade could alter results when time series are short.Footnote39 Similar caveats could apply to growth volatility, and most existing studies use data from only a few decades. Indeed, the longest time series extends across six decades (1950–2010),Footnote40 and the average time series across the 14 articles is 34 years.

Second, existing studies have relied on democracy measures from Polity or Freedom House. Since these measures have several validity and reliability issues,Footnote41 re-assessing the relationship using alternative measures is of value. Below, I use two recent state-of-the-art measures of democracy – one minimalist and categorical and one more comprehensive and continuous – from different sources.

Third, most studies have not accounted for country-specific effects on growth volatility, which could stem from several geographical, cultural, or other features. Countries with particular climates and soils, for example, could be conducive to certain types of agriculture with volatile output. If such factors relate also to autocratic rule, this could bias the observed relationship between regime type and volatility. Of the 14 identified articles, only two (both in economics journals) control for country-fixed effects. One is conducted on 73 countries and panels of 29 years and the other on 112 countries and 46 years.Footnote42

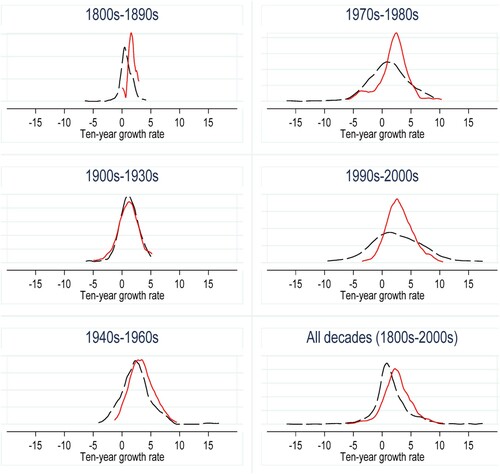

Hence, I revisit this relationship to assess how it holds up across time, leveraging data from more than two centuries. I start out by describing the distributions of growth rates, by regime type, for different periods across modern history. I utilize GDP p.c. data from the Maddison project and draw on Skaaning et al.’s Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy.Footnote43 I calculate the annualized percentage growth rate in GDP p.c. across a decade (e.g. 2000–2009), and measure regime type at the decade’s beginning (e.g. in 2000). For this descriptive exercise, I dichotomize the democracy index so that countries scoring ≥5, i.e. having both competitive multi-party elections and suffrage for at least half the adult population, are coded “democratic”. Countries (scoring <5) without competitive multi-party elections or with less extensive suffrage are coded “autocratic”.Footnote44 To check how consistent patterns are across time, I split the 1800–2009 period into five intervals. Given the fewer countries with data, and especially the paucity of democracies, early on, I consider the entire nineteenth century as one interval. The second interval (1900–1939) covers four decades, whereas the third interval covers three (1940–1969). The two final periods (1970–1989; 1990–2009) cover two decades each.

shows that certain patterns appear in most periods. First, the typical growth rates for democratic observations (red, solid lines) are higher than for autocracies (black, dashed lines). Second, variation is higher for the autocratic distributions, which incorporate various political systems with diverse institutional arrangements. The larger variation is especially notable if we consider the distributions’ “tails” – more extreme growth rates appear more frequently in autocratic contexts. In particular, periods of high negative growth are much more common in autocracies.Footnote45 These descriptive statistics do not account for autocracies typically being poorer than democracies, and poorer countries have higher growth variation. Yet, similar patterns emerge, for most time periods, when considering only relatively poor countries (Appendix Figure A-1).

Figure 1. Economic growth rates for democracies (red, solid lines) and autocracies (black, dashed lines) in different time periods. Note: Kernel density plots of ten-year growth rates, with country-decade as unit.

To be more specific, shows that mean growth was considerably higher in democracies during all periods, except for 1900–1939, when several democratic economies were hit by World War I and struggled through the subsequent Great Depression. For instance, the mean GDP p.c. growth rate was 1.7 for democracies during the nineteenth century, compared to 0.8 for autocracies. The corresponding numbers for 1970–1989 were 2.0 and 1.0. Moreover, the variance in growth rates was also consistently higher for autocracies, again with the exception being 1900–1939. The difference was particularly high during for 1990–2009, with 5.5 in variance across 154 democratic country-decades and 23.1 in variance across 145 autocratic country-decades. In these decades, only 7.1% of democratic observations observed negative growth rates and 0.6% exceeded +10% (positive) growth. For autocracies, 28.3% of observations experienced negative growth and 5.5% achieved growth above +10%.

When jointly considering 1800–2009, the mean autocratic and democratic growth rates were, respectively, 1.5% (877 country-decades) and 2.6% (364 country-decades). The respective variances were 9.4 and 6.0.

The higher variation among autocracies – especially the longer tails signifying more extreme observations – is also indicated by lists of “growth miracles” and “growth disasters”, to use Przeworski et al.’s terminology. These authors used data from 1950–1990 and concluded that both lists “are populated almost exclusively by dictatorships”.Footnote46

maps the worst and best performers per decade after 1990, when Przeworski et al.’s investigation ended. Also here, Autocracies dominate the lists for top- and, especially, bottom performers. Autocracies made up 6 of 10 top-performing countries in the (relatively slow-growing) 1990s, but 9 of 10 in the (fast-growing) 2000s. From 2010–2016 (last year of the GDP data), autocracies made up 5 of 10 top performers. Concerning bottom performers, all 10 countries were autocracies in the 1990s and 7 of 10 countries were autocracies during 2010–2016. The 2000s is the exception, as only 5 bottom achievers were autocracies – this is, indeed, the lowest share of autocracies on the bottom-10 list in any decade in modern history.

Table 1. Growth miracles and disasters, 1990–2016.

When looking closer at these lists, some noticeable patterns indicate why autocracies vary more in growth than democracies. Surely, the top-10 list for the 1990s include persistent development miracles such as Singapore and more recent ones like Vietnam. Yet, it also includes economies with oil-fuelled growth booms like Kuwait, Qatar, and Equatorial Guinea (also on the bottom-10 list after 2010, when oil prices decreased). The worst-performers list of the 1990s is dominated by post-Soviet republics – though not the more democratic ones in the Baltics – that experienced a sharp decline in registered growth rates with the collapse of Soviet command economy (and its inflated GDP statistics). Inevitably, several post-Soviet republics experienced “rebound growth” after the disastrous early 1990s, and some figure among the top performers of the ensuing decade.

More generally, as Przeworski et al. also observed, being a top performer in a particular decade often follows a disastrous economic performance in years prior. The high growth volatility of autocracies entails that some autocracies experience short periods of rapid growth. This holds also for regimes that experience rebound growth after devastating conflicts, such as Angola or Iraq in the 2000s. Insofar as regime type affects the likelihood of large-scale conflict, this also contributes to explain why 1990s-DR Congo or Afghanistan, 2000s-Burundi, or Assad’s Syria, Gadhafi’s Libya and Yemen, 2010–2016 are on the growth disasters lists. Finally, the growth disasters include autocratic regimes with well-documented track-records of economic mismanagement, like 2000s-Zimbabwe under Mugabe or Venezuela under Chavez and then Maduro, from 2010–2016.

However, such direct comparisons of growth rates across democracies and autocracies must be taken with a grain of salt; regimes differ systematically in other relevant regards. For example, initially poor countries are more often autocratic, and poor countries have higher potential for fast (catch-up) growth and inherently higher variation in growth performance. Hence, scholars working on democracy and growth typically run regression analysis, controlling for relevant confounders.

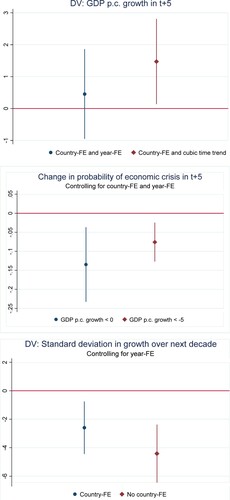

shows results from regressions controlling for initial income level, time trends, and country-specific factors that may affect both regime type and growth. contains coefficient plots visualizing the main results. I do not include additional controls in this initial analysis, following the discussion above on the dangers of “over-controlling” for factors that are important intermediate variables such as education policies or investment rates. Since I no longer discuss simple descriptive contrasts, and want to include as much information as possible, I employ V-Dem’s continuous Polyarchy index of electoral democracy.Footnote47 These analyses include 15,516 country-year observations, spanning 163 countries and 223 years.

Figure 2. Coefficient plots for Polyarchy index on economic growth (top), probability of experiencing economic crisis (middle), or growth volatility (bottom). Notes: Point estimates are surrounded by 95% confidence intervals. The plots are based on Models 1–5 and 7, .

Table 2. Democracy and different economic outcomes.

Models 1 and 2 consider the standard, “average” relationship between democracy and GDP p.c. growth. To account for the discussed time-lag, I measure growth five years after Polyarchy. Model 1 includes year-specific effects, whereas Model 2 includes a fairly flexible (cubic) time trend. Both analysis indicate a positive relationship between democracy and growth, but the significance of the relationship hinges on the particular model chosen. When I control for year-specific effects on growth, the relationship is statistically insignificant at conventional levels, whereas the more lenient control for time-trends in growth yields a substantially larger and statistically significant coefficient. Going from the Polyarchy score of 2019-Venezuela (0.23) to 2019-Uruguay (0.86) increases the predicted growth rate in the latter specification by almost one percentage point, which is substantial: If two initially equal economies growth at different speeds, with the faster-growing having a 1% higher annual growth rate, the faster-growing one will end up as twice as rich as the slower-growing one after about 70 years. Indeed, this estimated difference may even be attenuated, since it does not account for the discussed over-reporting of GDP numbers in more autocratic regimes.

The “average” relationship is thus sensitive to statistical modelling choices. In contrast, measures focusing on particular adverse economic outcomes or variability in economic performance yield more robust results. Consider first the relationship between democracy and probability of observing a subsequent economic crisis. presents results from two regressions where crisis is variously defined as experiencing negative growth rate in a year (Model 3) or growth below minus 5 percentage points (Model 4). Overall, 28.6% of the observations included experienced negative growth, whereas 8.8% experienced growth below minus 5 percentage points. The predicted probabilities of experiencing such events are reduced by, respectively, 8.5 and 4.8 percentage points when going from Venezuela’s 2019 Polyarchy level (0.23) to Uruguay’s (0.86). These significant results hold up even when controlling for ongoing inter- and intra-state armed conflicts and fuel and mineral income as share of GDP (Online Appendix B). The results also seem robust to using alternative definitions of “crisis”, other regime measures, and alternative GDP data.Footnote48

Moreover, democracy reduces overall growth variability. The outcome in Models 5–7 is the standard deviation in GDP p.c. growth over the subsequent decade. Models 5 (pooled cross-section time-series) and 6 (between-effects regression) indicate that the variation is much higher in more autocratic regimes when allowing for comparisons across countries. The Polyarchy coefficient is especially large in Model 6, which only draws on cross-country variation in growth volatility.

Yet, growth volatility may be higher in some countries than others for various reasons, and specifications omitting country-fixed effects could give biased results. Therefore, it is notable that Model 7 shows systematically higher variation for autocracies also when we consider changes within countries as they become more or less democratic over time. Although the fixed-effects Polyarchy coefficient is about one-third of the between-effects coefficient, the results corroborate earlier findings, which have typically omitted country-fixed effects and relied on far shorter time series,Footnote49 that autocracies have higher growth volatility.

The results on crises and especially growth variability are fairly robust to making different changes to measurements and specifications. For example, results are quite similar when substituting Polyarchy with the dichotomous measure counting countries scoring ≥5 on the Lexical Index, as democracies. Yet, the patterns might reflect that many autocracies are fuel and mineral producers or that poor autocracies more often experience armed conflicts. An economy centred on natural resource production is sensitive to particular fuel or mineral price fluctuations, increasing growth volatility. Armed conflicts are associated with destruction of capital stocks and reduced output, whereas post-conflict periods often observe high rebound growth. Hence, I re-ran the specifications in , but controlling for fuel and mineral income share in GDP and dummies registering inter- and intra-state conflicts. While results on crises are a bit weakened when controlling for resource dependence, controlling for ongoing armed conflicts and resource dependence barely alters the estimated difference in growth variability between regimes. One might argue that adding these controls is inappropriate, as the tendency to operate a non-diversified, resource-reliant economy or experience armed conflict are partly consequences of autocratic rule. This question notwithstanding, the conclusion is that more autocratic regimes have significantly higher growth variability.

Despite the control strategy and inclusion of country-fixed effects, unobserved time-varying confounders could still bias results. This is hard to guard against, but further tests included in Appendix B relieve some of the concern. First, I include multiple lagged dependent variables, up to 10 years before democracy is measured, to account for reverse causality or unobserved factors affecting trends both in the outcome and democracy.Footnote50 For growth volatility, I tried out additional combinations, controlling for growth variability in the two decades prior and multiple lags on GDP p.c. growth. All results in are retained. Similarly, results are retained in 2SLS models using two instruments pertaining to, respectively, the latest regime change happening in one of Huntington’s “reverse waves of democratization” and the current average democracy level in other countries in the region. These are strong instruments, displaying a high correlation with democracy in the first stage. Yet, it is hard to ensure that the instruments are not directly linked to growth outcomes, and thus that the exclusion restriction holds.Footnote51 Nonetheless, the robust results in these specifications at least provide additional indications that democracy mitigates crisis and reduces growth volatility.

Finally, I checked whether the democracy–growth volatility relationship is non-linear, or even non-monotonic, by adding Polyarchy squared to the benchmark. Countries with intermediate levels of democracy more frequently experience different types of political instability,Footnote52 which may enhance growth volatility. Moreover, it is unclear at what level of democracy the relevant safety-net mechanisms, discussed below, for constraining leaders and mitigating policies that give volatile growth set in. Hence, growth volatility could be quite high even at intermediary democracy levels. Indeed, I do find a non-linear relationship, with predicted growth volatility being fairly similar for relatively autocratic countries scoring between 0 and 0.5 on Polyarchy, but there is a sharp drop in growth volatility as Polyarchy increases further (Appendix Figure A-2). There is some evidence of countries scoring around 0.3 on Polyarchy having more volatile growth than countries scoring around 0, but the predicted difference is fairly small.

There are different plausible explanations for the large variation in growth performances among dictatorships, both when measured across countries but also within countries, over time. For instance, autocracies may have an advantage in enhancing (growth driven by) physical capital accumulation, but have slower rates of technological change, and thus TFP growth.Footnote53 This should mechanically contribute to higher volatility in autocracies; capital-induced growth often come in bursts of “catch-up growth”, especially in initially poor countries before convergence mechanisms kick in. TFP growth, especially in innovative countries at the technology frontier, is expectedly more durable and give more stable growth patterns.Footnote54 Yet, there are also plausible “political explanations” of the observed pattern centring on the (i) individual autocrat and (ii) different institutions that appear in the heterogeneous systems grouped together due to their lack of democracy.

First, power is more concentrated with the leadership – and often with one particular leader – in autocracies than democracies. Thus, the preferences and cognitive abilities of the top leader also matters more for which policies are selected, with downstream consequences for economic performance. Given the large variance in cognitive abilities and preferences of different individuals, this should contribute to the large growth variance in autocracies, also within regimes when one leader replaces another. For example, dictators who care primarily about their private consumption pursue different investment policies than autocrats primarily concerned with maximizing regime survival or their own control over society.Footnote55

The notion that the individual autocrat is important for economic performance is backed up by stringent evidence. Jones and Olken consider natural deaths of leaders and study the subsequent impact on growth rates.Footnote56 Leader deaths in autocracies are accompanied by a significant change in growth, and the change is larger in autocracies with fewer constraints on executive power. In contrast, leader deaths do not systematically alter growth rates in democracies.

In addition, autocracies display vast variation in political institutions. How institutions are structured shape which leaders are selected. Institutions also shape leaders’ incentives to take a long-time horizon or be myopic, or to consider broad swaths of the population versus only the utility of a selected few when formulating economic policies. Institutions, of different kinds, also place constraints on what kind of economic policies leaders can select, regardless of their personal policy preferences. Nyrup theorizes and shows empirically how constraints by regime outsiders, namely active civil society organizations, and by powerful regime insiders, proxied by long tenure of cabinet ministers, both enhance growth in autocracies.Footnote57 Drawing on global data back to 1965, Nyrup finds that such constraints matter for growth in autocracies even when accounting for leader-fixed effects. Hence, changes in external and internal constraints during a ruler’s tenure may add to the high growth volatility in autocracies.

In Appendix C, I consider three other institutional features that could shape the economic performances of, and more specifically mitigate growth volatility in, autocracies, as they place different constraints on what economic policies leaders can pursue. These institutional features pertain to the impartiality and rule-following nature of state bureaucracies, autonomy and capabilities of legislatures, and extent to which political parties are institutionalized. I assess these institutions because they are explicitly argued to place constraints on autocrats in existing scholarship,Footnote58 and because I can leverage extensive time series data (from V-Dem) to measure them. In brief, I find little support for the hypotheses that impartial and rule-following administrations or capable and autonomous legislatures mitigate growth volatility when studying a sub-sample of autocracies. I find some support for institutionalized parties reducing volatility, but this is not robust to controlling for country-fixed effects. Further, the strong relationship between democracy and (low) volatility is retained when controlling for all these measures, although it is somewhat attenuated when controlling for party institutionalization. Hence, autocracies have higher growth volatility than democracies even when accounting for several other institutional differences.

The higher variability in economic performance among autocracies is not only of academic interest, but likely influences the actions and well-being of investors, entrepreneurs, and citizens trying to manoeuver in these volatile economies. High growth volatility, presumably following from high variability in the economic policies pursued by autocrats, may thus even have independent effects on future economic performance. The behaviour of economic actors – from entrepreneurs considering whether or not to start a new business to prospective workers considering which education to pursue – is predicated on forming predictions about the future economic environment.

Assuming that many such economic actors are risk averse, high variability could deter different types of investments and other economic transactions with high expected future gains. Stability and predictability may be especially important for innovation-related activities that require a long-time horizon, or for actors who invest in asset-specific human and physical capital (which allow for specialization and potentially have high returns to investment, but also entail higher risk). Hence, the desire to mitigate variability in policy and performance, and ensuring a stable, less risky environment, is a key part of the business case for democracy.Footnote59 For risk-averse workers and consumers, high growth volatility related to violent business cycles enhances the chances of outcomes that produce low utility, notably including increased chances of unemployment, which may be especially bad in autocracies where large groups of workers are often not covered by unemployment insurance.

Growth volatility thus matters for both producers and consumers. While scholars studying democracy and growth have studied average growth over long periods of time, macro-economists from Keynes onwards have focused intensively on business cycles and how to mitigate them with fiscal and monetary policies. Especially after WWII, also many politicians have been concerned with constructing economic policies to counter business cycles. The results presented above suggest that one cure for violent business cycles is not merely a particular policy, but rather democratic features of the regime that, in turn, likely affect several policies with downstream implications for growth volatility.

Conclusion

I have laid out a business case for democracy, focusing on the relationship with economic growth. In doing so, I made two contributions. The first is a review and critical discussion of the vast literature on democracy and growth, focusing on common methodological issues and how they influence results. The second is an empirical analysis on comprehensive data material, focusing primarily on growth volatility.

Concerning the former contribution, existing studies have been more ambiguous about the benevolent effects of democracy on growth compared to other development outcomes such as infant mortality rates or literacy. A leading textbook in comparative politics sums up the debate as follows: “This question has generated an enormous literature in both political science and economics, but … there is as yet no strong consensus on what the answer is. Different arguments abound.”Footnote60 Yet, I have discussed factors that might make several previous studies underestimate the relationship between democracy and growth. For instance, autocracies seem to systematically over-report GDP numbers and many existing studies have controlled for relevant indirect effects, such as access to education, through which democracy enhances growth. Nonetheless, the average relationship between democracy and growth – while fairly strong and plausible – is not entirely robust and hinges on specification choices, which is also reflected in the results presented in this paper.

In contrast, relationships between democracy and measures of variation in economic performance are robust. As such, democratic rule may present both businesses and citizens with an important economic safety-net. Democracy mitigates the possibility for countries to experience truly tragic economic outcomes. The kind of growth disasters associated with Mao’s Great Leap Forward in China or Mobutu Sese Seko’s kleptocratic rule in Zaïre simply do not occur in democracies. This is presumably, in part, because voters would kick out leaders pursuing very harmful economic policies, and democratic incumbents aware of this scenario therefore refrain from pursuing such policies in the first place. Further, global data from the last two centuries reveal that democracies observe lower growth volatility than autocracies. This pattern constitutes a strong business case for democracy; avoiding crises and macro-economic instability – with adverse consequences for bankruptcies, unemployment, inflation, wages, profits, and so on – is of great value to investors, firms, workers, and consumers alike.

Appendix_Business_Case_Democratization_Revised_2.pdf

Download PDF (299.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carl Henrik Knutsen

Carl Henrik Knutsen is Professor of Political Science at the University of Oslo. His research interests include the economic effects of political institutions, the determinants of regime change, and the measurement of democracy. He has published his work in journals such as the American Journal of Political Science, British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, Journal of Politics, Political Analysis, World Development, and World Politics. He currently leads, inter alia, an ERC Consolidator Grant project on the “Emergence, Life, and Demise of Autocratic Regimes” and is co-PI of V-Dem.

Notes

1 While numerous studies find that GDP growth is correlated with other outcomes that affect consumers (e.g. wage growth, unemployment) or investors and firms (e.g. demand, product prices, stock prices), particular crises may deviate from the general patterns. For instance, the US stock market improved during 2020, even as GDP slumped with the Covid-crisis. Also, certain individuals, firms, and sectors may gain from a crisis (e.g. producers of hand-sanitizers during the Covid-crisis), but the general picture is that both consumers and firms are adversely affected.

2 Sen, Development as Freedom, 15.

3 Przeworski and Limongi, “Political Regimes”; Przeworski et al., Democracy and development.

4 For an early meta-study, see Doucouliagos and Ulubasoglu, “Democracy and Economic Growth”- For a recent meta-study, comprising 2047 regression models from 188 studies, see Colagrossi et al., “Does Democracy Cause Growth?” This study finds (stronger) evidence of a positive effect of democracy once considering only studies after December, 2005.

5 For example, Ganau, “Institutions and Economic Growth” studies 50 African countries. He finds a negative effect of democracy, as measured by Freedom House, but controls for several variables that are arguably post-treatment to democracy including “government crisis” and “legislature effectiveness.” Aisen and Veiga, “Political Instability and Growth” find negative and sometimes significant estimates in a larger global sample, using the Polity measure, but also control for post-treatment variables such as investment, primary school enrollment, and economic freedom.

6 One prominent study from the 2010s reporting a null effect is Murtin and Wacziarg’s, “The Democratic Transition” (206 Google Scholar citations). Among those reporting a positive effect, we find Acemoglu et al., “Democracy Does Cause Growth” (985 citations). Other recent studies report mixed results. For example, Gründler and Krieger, “Democracy and Growth” (100 citations) find a positive relationship when using their Support Vector Machines Democracy Index but several null results for conventional democracy measures.

7 Gjerløw et al., One Road to Riches?

8 See, e.g. Fukuyama, “States and Democracy”; Mazzuca and Munck, “State or Democracy First?”

9 For recent examples, see Nyrup, Benevolent Autocrat? 1.

10 E.g. Wiles, “Soviet Economy Outpaces West.”

11 Kim, The Four Asian Tigers.

12 See Li, “The Chinese Model.”

13 E.g. Lührman and Lindberg, “Third Wave of Autocratization.”

14 E.g. BBC, “Coronavirus: Iran cover-up.”

15 Geddes et al., How Dictatorships Work.

16 E.g. Almeida and Ferreira, “Democracy and Variability”; Knutsen, “Autocracy and Variation”; Mobarak, “Democracy, Volatility, Economic Development”; Rodrik, One Economics, Many Recipes; Sen et al., “Democracy Versus Dictatorship?”

17 See, e.g. Przeworski and Limongi, “Political Regimes.”

18 See, e.g. Baum and Lake, “The Political Economy.”

19 See, e.g. Knutsen, The Economic Effects.

20 Colagrossi et al., “Does Democracy Cause Growth?”

21 Knutsen, The Economic Effects.

22 Papaioannou and Siourounis, “Democratization and Growth.”

23 Knutsen, The Economic Effects.

24 Acemoglu et al., “Democracy Does Cause Growth.”

25 Knutsen, “Democracy and Economic Growth.”

26 See Doucouliagos and Ulubasoglu, “Democracy and Economic Growth.”

27 See also, e.g. Krieckhaus, “The Regime Debate Revisited.”

28 Knutsen and Wig, “Government Turnover.”

29 Gerring et al., “Democracy and Economic Growth”; Edgell et al., “Democratic Legacies.”

30 Hollyer et al., Information, Democracy, and Autocracy.

31 Halperin et al., The Democracy Advantage, 33; Knutsen, The Economic Effects, 174–75.

32 Wheatcroft and Davies, “The Crooked Mirror.”

33 Chen et al., “A Forensic Examination.”

34 Wallace, “Juking the Stats?”

35 Magee and Doces, “Reconsidering Regime Type,” 223.

36 Martinez, “Dictator's GDP Growth Estimates,” 2.

37 Colagrossi et al., “Does Democracy Cause Growth?”

38 E.g. Almeida and Ferreira, “Democracy and Variability”; Knutsen, “Autocracy and Variation”; Mobarak, “Democracy, Volatility, Economic Development”; Rodrik, One Economics, Many Recipes; Sen et al., “Democracy Versus Dictatorship?”

39 Colagrossi et al., “Does Democracy Cause Growth?”

40 Sen et al., “Democracy Versus Dictatorship?”

41 Boese, “How to Measure Democracy.”

42 Edwards and Thames, “Growth Volatility and Development”; Klomp and De Haan, “Institutions and Economic Volatility.”

43 Bolt and van Zanden, “The Maddison Project”; Skaaning et al., “A Lexical Index.” Regarding other data used in this paper, indices for Polyarchy, Party Institutionalization, Legislative Constraints, and Impartial Administration are from Coppedge et al., “V-Dem Dataset v10.” See also Coppedge et al., “V-Dem v10. Codebook” and Pemstein et al., “V-Dem Measurement Model.” Conflict data are from Sarkees and Wayman, Resort to War. Natural resource data are from Miller, “Democratic Pieces.”

44 Results are quite robust to using alternative operational rules for dividing up the sample into relatively democratic and relatively autocratic countries, for instance when using the categorical measure by Lührman et al., “Regimes of the World” or the dichotomous measure by Boix et al., “A Complete Dataset.”

45 See also Sen et al., “Democracy Versus Dictatorship?”

46 Przeworski et al., Democracy and Development, 178.

47 Teorell et al., ”Measuring Polyarchy.”

48 See Knutsen, “Autocracy and variation” for tests on growth variability and crisis that draw on different GDP data and a different measure for distinguishing democracies from autocracies.

49 But, see Knutsen, “Autocracy and Variation.”

50 See Acemoglu et al., “Democracy Does Cause Growth.”

51 Sargan tests suggest that the exclusion restriction may be violated in the two specifications on crises and in the fixed-effects specification on growth volatility. Theoretically, there is particular reason for concern about the regional averages instrument (see Betz et al., “Spatial Interdependence”), although the issue of a country’s democracy level influencing the regional averages instrument should be reduced by exempting the country in question from the regional average calculation and by dividing the world into only six regions. The reverse wave instrument is from Knutsen, The Economic Effects.

52 E.g. Knutsen and Nygård, “Institutional Characteristics and Survival.”

53 E.g. Knutsen, The Economic Effects.

54 Gerschenkron, Economic Backwardness; Barro and Sala-i-Martin, Economic Growth.

55 Wintrobe, Political Economy of Dictatorship.

56 Jones and Olken, “Do Leaders Matter?”

57 Nyrup, Benevolent Autocrat? Nyrup also finds that the effect of external constraints are stronger absent internal constraints, and vice versa.

58 On impartial and rule-following administration, see, e.g. Knutsen, “Democracy, State Capacity.” On legislatures, see, e.g. Wright, “Do Authoritarian Institutions Constrain?” Gandhi, “Dictatorial Institutions” Cox and Weingast, “Executive Constraint, Political Stability.” On institutionalized parties, see, e.g. Bizzarro et al., “Party Strength.”

59 See also Mobarak, “Democracy, Volatility, Economic Development.”

60 Clark et al., Principles in Comparative Politics, 330.

Bibliography

- Acemoglu, Daron, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restrepo, and James A. Robinson. “Democracy Does Cause Growth.” Journal of Political Economy 127, no. 1 (2019): 47–100.

- Aisen, Ari, and Francisco José Veiga. “How Does Political Instability Affect Economic Growth?” European Journal of Political Economy 29, no. 1 (2013): 151–167.

- Almeida, Heitor, and Daniel Ferreira. “Democracy and the Variability of Economic Performance.” Economics & Politics 14, no. 3 (2002): 225–257.

- Amsden, Alice. Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Barro, Robert J., and Xavier Sala-i-Martin. Economic Growth. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004.

- Baum, Matthew A., and David A. Lake. “The Political Economy of Growth: Democracy and Human Capital.” American Journal of Political Science 47, no. 2 (2003): 333–347.

- BBC. “Coronavirus: Iran Cover-Up of Deaths Revealed by Data Leak.” News Article, August 3, 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-53598965.

- Betz, Timm, Scott J. Cook, and Florian M. Hollenbach. “Spatial Interdependence and Instrumental Variable Models.” Political Analysis 8, no. 4 (2020): 646–661.

- Bizzarro, Fernando, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Allen Hicken, Michael Bernhard, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Michael Coppedge, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “Party Strength and Economic Growth.” World Politics 70, no. 2 (2018): 275–320.

- Boese, Vanessa. “How (not) to Measure Democracy.” International Area Studies Review 22, no. 2 (2019): 95–127.

- Boix, Carles, Michael Miller, and Sebastian Rosato. “A Complete Dataset of Political Regimes, 1800-2007.” Comparative Political Studies 46, no. 12 (2013): 1523–1554.

- Bolt, Jutta, and Jan L. van Zanden. “The Maddison Project: Collaborative Research on Historical National Accounts.” Economic History Review 67, no. 3 (2014): 627–651.

- Chen, Xilu, Wei Chen, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and Zheng Song. “A Forensic Examination of China’s National Accounts.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1 (2019): 77–141.

- Clark, William Roberts, Matt Golder, and Sona N. Golder. Principles in Comparative Politics. 3rd ed. London: Sage, 2018.

- Colagrossi, Marco, Domenico Rossignoli, and Mario A. Maggioni. “Does Democracy Cause Growth? A Meta-Analysis (of 2000 Regressions).” European Journal of Political Economy 61, no. 101824 (2020): 1–39.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, et al. “V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v10,” 2020. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, et al. “V-Dem Codebook v10”, 2020.

- Cox, Gary W., and Barry R. Weingast. “Executive Constraint, Political Stability, and Economic Growth.” Comparative Political Studies 51, no. 3 (2018): 279–303.

- Doucouliagos, Hristos, and Mehmet Ulubasoglu. “Democracy and Economic Growth: A Meta-Analysis.” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 1 (2008): 61–83.

- Edgell, Amanda B., Matthew C. Wilson, Vanessa A. Boese, and Sandra Grahn. “Democratic Legacies: Using Democratic Stock to Assess Norms, Growth, and Regime Trajectories.” University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Working Paper 100, 2020.

- Edwards, Jeffrey A, and Frank C. Thames. “Growth Volatility and the Interaction between Economic and Political Development.” Empirical Economics 39, no. 1 (2010): 183–201.

- Fukuyama, Francis. “States and Democracy.” Democratization 21, no. 7 (2014): 1326–1340.

- Ganau, Roberto. “Institutions and Economic Growth in Africa: A Spatial Econometric Approach.” Economia Politica 34 (2017): 425–444.

- Gandhi, Jennifer. “Dictatorial Institutions and their Impact on Economic Growth.” European Journal of Sociology 49, no. 3 (2008): 3–30.

- Geddes, Barbara, Joseph Wright, and Erica Frantz. How Dictatorships Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Gerring, John, Philip Bond, William T. Barndt, and Carola Moreno. “Democracy and Economic Growth: A Historical Perspective.” World Politics 57, no. 3 (2005): 323–364.

- Gerschenkron, Alexander. Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1962.

- Gjerløw, Haakon, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Tore Wig, and Matthew C. Wilson. One Road to Riches? How State Building and Democratization Affect Economic Development. Forthcoming on Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Gründler, Klaus, and Tommy Krieger. “Democracy and Growth: Evidence from a Machine Learning Indicator.” European Journal of Political Economy 45 (2016): 85–107.

- Halperin, Morton H., Joseph T Siegle, and Michael M. Weinstein. The Democracy Advantage: How Democracies Promote Prosperity and Peace. New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Hollyer, James R., B. Peter Rosendorff, and James R. Vreeland. Information, Democracy, and Autocracy: Economic Transparency and Political (In)Stability. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Jones, Benjamin F., and Benjamin A. Olken. “Do Leaders Matter? National Leadership and Growth Since World War II.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 120, no. 3 (2005): 835–864.

- Kim, Eun Mee, ed. The Four Asian Tigers – Economic Development and the Global Political Economy. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998.

- Klomp, Jeroen, and Jakob De Haan. “Political Institutions and Economic Volatility.” European Journal of Political Economy 25, no. 3 (2009): 311–326.

- Knutsen, Carl Henrik. “Autocracy and Variation in Economic Development Outcomes.” In Handbook on Democracy and Development, edited by G. Crawford, and A.-G. Abdulai, 117–134. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, 2020.

- Knutsen, Carl Henrik. “Democracy and Economic Growth: A Review of Arguments and Results.” International Area Studies Review 15, no. 4 (2012): 393–415.

- Knutsen, Carl Henrik. “Democracy, State Capacity and Economic Growth.” World Development 43 (2013): 1–18.

- Knutsen, Carl Henrik. “The Economic Effects of Democracy and Dictatorship.” PhD thesis, University of Oslo, 2011.

- Knutsen, Carl Henrik, and Håvard M. Nygård. “Institutional Characteristics and Regime Survival: Why Are Semi-Democracies Less Durable Than Autocracies and Democracies?” American Journal of Political Science 59, no. 3 (2015): 656–670.

- Knutsen, Carl Henrik, and Tore Wig. “Government Turnover and the Effects of Regime Type: How Requiring Alternation in Power Biases against the Estimated Economic Benefits of Democracy.” Comparative Political Studies 48, no. 7 (2015): 882–914.

- Krieckhaus, Jonathan. “The Regime Debate Revisted: A Sensitivity Analysis of Democracy’s Economic Effect.” British Journal of Political Science 34, no. 4 (2004): 635–655.

- Li, He. “The Chinese Model of Development and Its Implications.” World Journal of Social Science Research 2, no. 2 (2015): 128–138.

- Lührman, Anna, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “A Third Wave of Autocratization is Here: What is New about It?” Democratization 26, no. 7 (2019): 1095–1113.

- Lührman, Anna, Marcus Tannenberg, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes.” Politics and Governance 6, no. 1 (2018): 60–77.

- Magee, Christopher S., and John A. Doces. “Reconsidering Regime Type and Growth: Lies, Dictatorships, and Statistics.” International Studies Quarterly 59, no. 2 (2015): 223–237.

- Martinez, Luis R. “How Much Should We Trust the Dictator’s GDP Growth Estimates?” University of Chicago, Working Paper, 2019.

- Mazzuca, Sebastian L., and Gerardo L. Munck. “State or Democracy First? Alternative Perspectives on the State-Democracy Nexus.” Democratization 21, no. 7 (2014): 1221–1243.

- Miller, Michael K. “Democratic Pieces: Autocratic Elections and Democratic Development Since 1815.” British Journal of Political Science 45, no. 3 (2015): 501–530.

- Mobarak, Ahmed Mushfiq. “Democracy, Volatility, and Economic Development.” Review of Economics and Statistics 87, no. 2 (2005): 348–361.

- Murtin, Fabrice, and Romain Wacziarg. “The Democratic Transition.” Journal of Economic Growth 19, no. 2 (2014): 141–181.

- Nyrup, Jacob. “The Myth of the Benevolent Autocrat? Internal Constraints, External Constraints and Economic Development in Autocracies.” PhD thesis, University of Oxford, 2020.

- Papaioannou, Elias, and Gregorios Siourounis. “Democratisation and Growth.” The Economic Journal 118, no. 532 (2008): 1520–1551.

- Pemstein, Daniel, Kyle L. Marquardt, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Juraj Medzihorsky, Joshua Krusell, Farhad Miri, and Johannes von Römer. “The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-National and Cross-Temporal Expert-Coded Data.” University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Working Paper 21, 2020.

- Przeworski, Adam, Michael E. Alvarez, José Antonio Cheibub, and Fernando Limongi. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 1950-1990. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Przeworski, Adam, and Fernando Limongi. “Political Regimes and Economic Growth.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 7, no. 3 (1993): 51–69.

- Rodrik, Dani. One Economics, Many Recipes: Globalization, Institutions, and Economic Growth. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Sarkees, Meredith Reid, and Frank Wayman. Resort to War: 1816 - 2007. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2010.

- Sen, Amartya. Development as Freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Sen, Kunal, Lant Pritchett, Sabyasachi Kar, and Selim Raihan. “Democracy Versus Dictatorship? The Political Determinants of Growth Episodes.” Journal of Development Perspectives 2, no. 1-2 (2018): 3–28.

- Skaaning, Svend-Erik, John Gerring, and Henrikas Bartusevičius. “A Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy.” Comparative Political Studies 48, no. 12 (2015): 1491–1525.

- Teorell, Jan, Michael Coppedge, Staffan I. Lindberg, and Svend-Erik Skaaning. “Measuring Polyarchy Across the Globe, 1900–2017.” Studies in Comparative International Development 54, no. 1 (2019): 71–95.

- Wallace, Jeremy L. “Juking the Stats? Authoritarian Information Problems in China.” British Journal of Political Science 46, no. 1 (2016): 11–29.

- Wheatcroft, S. G., and R. W. Davies. “The Crooked Mirror of Soviet Economic Statistics.” In The Economic Transformation of the Soviet Union 1913–1945, edited by R.W. Davies, Mark Harrison, and S.G. Wheatcroft, 24–37. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

- Wiles, Peter. “The Soviet Economy Outpaces the West.” Foreign Affairs 31, no. 4 (1953): 566–580.

- Wintrobe, Ronald. The Political Economy of Dictatorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Wright, Joseph. “Do Authoritarian Institutions Constrain? How Legislatures Affect Economic Growth and Investment.” American Journal of Political Science 52, no. 2 (2008): 322–343.