ABSTRACT

In a context of areas of limited statehood and contested order, Iraq, Lebanon and Syria have been affected by similar diffuse global and more specific regional and local risks over the past two decades. Yet they differ in outcomes. Lebanon has not descended into civil war despite fears that the one raging in Syria might spill over to its territory and Iraq has coped better over the past decade than Syria has – despite having been subject to various forms of conflict since 1980. We analyse this variance by asking to what extent resilience might buffer against violent conflict and governance breakdown. Through a comparative discussion of sources of resilience – social trust, legitimacy and institutional design – we find that limited input and threatened output legitimacy are harmful to resilience, while collective memory and reconciliation, as well as flexibility of institutions are crucial factors of resilience. Nonetheless, our findings caution that resilience should not only mean the capability to adapt to crises but also needs to set the stage for comprehensive and inclusive transformations that are locally rooted.

Introduction

Resilience has become an important concept at the intersection of the International Relations and Comparative Political Science literatures over the past decade, representing a polysemous concept whose meaning has been contested.Footnote1 Regarding the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), there has been a longer-standing literature which has focused on authoritarian resilience,Footnote2 i.e. the resilience of political elites and “their system of patronage and clientelism often endorsed directly or indirectly by the international community”,Footnote3 which undermines the state, its institutions and social trust.Footnote4 The “newer” resilience literature has evolved around issues such as resistance as resilience,Footnote5 resilience and the Arab uprisingsFootnote6 and resilience and refugees.Footnote7 At the same time, the concept of resilience has been subject to vociferous debates in the MENA that have criticized it as a new stability paradigm that asks local societies to adapt to oppressive conditions, hardship and inequalityFootnote8 and to fill the gap of the state while “agreeing to move on without justice” and “accepting that you don’t have a state to hold accountable”.Footnote9 Resilience also evades the question of how the international community props up corrupt and authoritarian regimesFootnote10 and the fallacies in the larger neoliberal development model.Footnote11

This article contributes to this debate in two respects. Firstly, apart from the authoritarian resilience literature much of the “newer” research on resilience in the MENA is based on single case studies,Footnote12 we add a comparative perspective to this by analysing three countries: Iraq, Lebanon and Syria. Secondly, we apply the comprehensive understanding of resilience of this Special Issue (SI), namely “the adaptive capacity of societies, communities, and individuals to deal with opportunities and risks in a peaceful manner”. This definition is not about stability, but about the ability to change; and it is not about state but societal resilience. Furthermore, we also draw on the conceptual framework of this SI regarding the sources of resilience, namely social trust, legitimacy and institutional design, which allows for a concise comparative analysis.

The comparative analysis of Iraq, Lebanon and Syria is promising, as all three countries have been exposed to similar risks since the Arab uprisings, be they economic crises, decreasing oil revenues, reduced flows of regionally recycled oil rents, internal contestation, foreign interference, the threat of the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq (ISIS), waves of refugees and internally displaced persons, as well as Covid-19. While dynamics in the three countries are intertwined and part of what Reinoud Leenders refers to as “regional conflict formations”,Footnote13 the ability and approaches to cope with the associated risks differ. The area encompasses a rentier state with hybrid governance structures (Iraq), a semi-rentier state where an unreformed authoritarianism reigns supreme and oil production has collapsed (Syria) and a formally democratic sectarian system that has heavily depended on the regional recycling of oil rents and international capital inflows that have become untenable by now (Lebanon). In terms of outcomes, Lebanon has not descended into renewed civil war and Iraq has coped better over the past decade than Syria has – despite having been subject to various forms of conflict since 1980.

How can we explain this variance? In line with the larger research question of this Special Issue, we are asking to what extent resilience might buffer against violent conflict and governance breakdown in a context of areas of limited statehood (ALS) and contested orders.

The methodology of this article is based on a most-similar case study design, meaning observing similar cases (in terms of risks, the independent variable) that differ in terms of outcomes (violent conflict and governance breakdown, the dependent variables). This enables us to look into variance in resilience, the main mediating variable we are interested in (see Figure 1 in the Introduction to this Special Issue). As this is a comparative study, we cannot engage in deep process-tracing of a single case study. Instead, we start by analysing the similar risks that all three countries have been exposed to over the last two decades before highlighting the variance they have experienced in terms of violent conflict and governance breakdown.

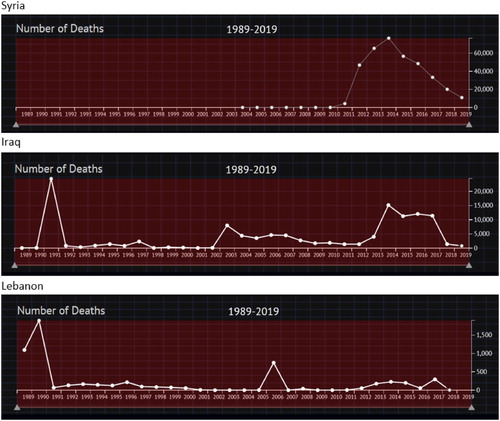

Figure 1. Conflict Data for Iraq, Lebanon and Syria. Source: Uppsala University Department of Peace and Conflict Research (2020).

Notes: Total number of deaths from state-based violence, non-state violence and from one-sided violence.

We then turn to a comparative analysis of resilience, particularly three sources thereof: social trust, legitimacy and institutional design that is “fit for purpose”.Footnote14 To all these ends, we use data from three H2020 projects: an elite survey consisting of in-depth interviews with 30 Lebanese stakeholders (MEDRESET), a focus group of twelve experts, civil society leaders and activists from the Arab Middle East held in Beirut (MENARA), and theoretical research from the larger EULISTCO framework.Footnote15 We also engage with existing databases such as the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) on organized violence and civil war and the Arab Barometer surveys, as well as the existing secondary literature, particularly from local researchers, that provides in-depth research on these three sources of resilience.

Risks for Iraq, Lebanon and Syria

The global, regional and local risks that Iraq, Lebanon and Syria face sometimes affect them in different ways. Diffuse global risks include climate change, reliability of food supplies, fluctuations in oil revenues and more recently the Covid-19 pandemic.Footnote16 Particularly important here is the ability to absorb adverse shocks, such as declining oil production (Syria), oil price corrections (Iraq) and waning indirect inflows of oil rents from the Gulf countries in the form of strategic transfer payments, investments and remittances (Lebanon). The strong reliance on direct and indirect oil rents also affects the ability to finance food imports on which the three countries depend. Considerable government capacity is invested in generating and maintaining oil-related revenue streams in terms of domestic policy and diplomacy (e.g. at OPEC in the case of Iraq or with the Gulf countries in the case of Lebanon). In comparison, climate change does not play a prominent role in policy discourse and implementation. Although the MENA is among the most affected regions globally, the risk appears as too diffuse compared to limited governance capacities and the pressing day-to-day issues. Addressing it would also run counter to oil production and related consumer interests, such as fuel subsidies. Meanwhile much of the governance capacity and public discourse is consumed by the regional risks that affect the lives of citizens with daily immediacy. More recently the Covid-19 pandemic has exposed the strained public health infrastructure in the three countries, all three states have been international laggards in rolling out vaccination campaigns and accused of allocating the few vaccines they received to politically connected people, rather than according to medical priorities.Footnote17

The United States’ invasion of Iraq in 2003 and the failure to control the post-war situation and build a regional security architecture increased regional risks and order contestation sharply. As the MENARA focus group has put it, the

“proliferation of weak states has created new opportunities for intervention by other regional and global actors, as well as non-state players. Regional dynamics are no longer based on formal or rigid alliances and conventional wars. Instead, they are largely based on proxy wars, state–society clashes and the larger Saudi–Iranian–Israeli conflict”,

Uncontained regional-order contestation is directly connected to ALS and local risks: it thrives on them and aggravates them. As Börzel and Risse point out,

The ability to set and enforce rules or to control the means of violence can be limited along various dimensions: (1) territorial, i.e. parts of a country’s territorial spaces; (2) sectorial, that is, with regard to specific policy areas; (3) social, i.e. with regard to specific parts of the population.Footnote19

Withdrew their loyalty from the state and attached it to sub/trans-state movements and identities, Islamism, sectarianism and ethnicity. Thus, as state’s strength declined, so correspondingly did their penetration by global forces and vulnerability to mobilizing sub/trans-state movements relatively increase.Footnote22

Violent conflict and governance breakdown

If in 2010, just before the Arab uprisings began, someone had asked whether Iraq, Lebanon or Syria was most likely to experience violent conflict and a breakdown of governance, many would have pointed to Iraq, maybe Lebanon, but most likely not Syria. The last time the latter had experienced violent conflict was in the late 1970s (continuing up until 1982). Then, the Hama uprising of the Muslim Brotherhood was followed by the siege of that city and the massacre of thousands of its inhabitants by Syrian security forces.

In contrast, Iraq had been through 30 years of conflict in various forms by 2010. After the long Iran–Iraq war (1980–1988), Iraq occupied Kuwait – only to be pushed back by the US and its allies (1990–1991). A devastating sanctions policy (1990–2003) that was accompanied by “no-fly zones” and occasional military skirmishes was followed by the US-led invasion (2003) that eventually resulted in insurgency and a civil war (see ).

Lebanon lived through an ostensibly stable period after the end of its own civil war in 1990, when parts of its territory were occupied by Israel until 2000 and by Syria until 2005. The most violent episode in the period that followed was the war with Israel in 2006. After 2010, Syria was the country that would become engulfed by an extremely violent conflict. In Iraq, conflict grew again between 2013 and 2017. Lebanon, in contrast, experienced comparatively minor levels of violent conflict as the UCDP graphs below show.

The Syrian civil war that broke out in 2011 represented a tipping point. It had been preceded by the detrimental impact of the Iraqi civil war and corresponding refugee flows as well as of the economic opening up of the over-extended Syrian security state in an attempt to mitigate its fiscal predicament. The Arab uprising in Syria began in areas particularly affected by these policies, such as Dera’a. The regime reacted with outright violence, while opposition actors in Syria were armed by outside forces; the tipping point cascaded, as an uprising turned into a multiple-front civil and proxy war. Violence escalated further when ISIS seized territory in Syria in 2013.

In Iraq, a first tipping point was the eruption of civil war after sanctions had weakened the country’s social fabric and once the US invasion toppled the authoritarian order of Saddam Hussein. A second tipping point happened in 2014 when ISIS overran one-third of the country’s territory, capitalizing on Sunni grievances against the Shia-led government in Baghdad. It was only defeated by a concerted military effort by the Kurdish Peshmerga and the Shiite Popular Mobilization Units (PMU), which received military support from Western allies and Iran respectively. In early 2020, a third tipping point could have occurred with US airstrikes on the PMU, the occupation of the US embassy, the American assassination of Iran’s General Qasem Suleimani and the ongoing protests in the country. However, the situation was contained, as an agreement on a new government was found that sufficiently satisfied – for now, at least – the interests of the US, Iran and protesters alike.

Finally, Lebanon has often been depicted as a “poster child” for ALS since the civil war years (1975–1990). Yet more recently it has avoided the tipping points occurring in Syria and Iraq. The end of the so-called “Pax Syriana”, the relatively stable period following the civil war, could have pushed the country towards the brink of renewed civil war in the 2004–2008 period. The US pushed the question of Syrian withdrawal and the disarming of Hezbollah through the United Nations Security Council in 2004, then Prime Minister Rafic Hariri was assassinated in 2005 and massive demonstrations arose subsequently. In this precarious situation, a year later said war broke out between Israel and Hezbollah.

UNSC Resolution 1701 ended the violence, but the situation remained tense. As Karim Makdisi has pointed out, a “bitter internal conflict resulted in sectarian clashes, the collapse of the national unity government in November 2007 and the creation of an unprecedented constitutional vacuum” – one which ended only in 2008 with the Doha Agreement. As a result, Hezbollah was reincorporated into the Lebanese government and “the resistance [to Israel] as a national project that could coexist with the Lebanese armed forces [was confirmed]”.Footnote23 Another tipping point could have emerged with the civil war in Syria, Hezbollah’s role in it, the threat of ISIS and the enormous refugee flows to Lebanon – which, amongst other issues, have significant implications for the delicate demographic balance in the country. Yet it has managed to avoid a spill-over effect so far. Whether this might change remains to be seen at the time of writing. In 2019/20 renewed waves of protest occurred. Lebanon is facing an existential crisis in the wake of currency devaluation, the breakdown of a financial Ponzi scheme that was engineered over decades by its central bank,Footnote24 Covid-19 and the devastating explosion in the port of Beirut. Traditional elite cooperation is compromised and there is a pronounced short-termism of its hybrid governance arrangements in the face of such challenges.

To conclude this section, diffuse global, as well as regional and local risks are high in all cases. ALS were territorially confined in Syria until the outbreak of civil war there, whereas both Iraq and Lebanon had ALS and hybrid constitutions before 2010. Since then, Syria and Iraq have experienced diverse forms of violence and governance breakdown; Lebanon decidedly less so. In Syria, a tipping point cascaded into a civil and proxy war from 2011 onwards. In Iraq, the 2013/14 tipping point emerged in a layered way out of its recent history of sanctions, invasion, insurgency and civil war. In 2019/20, the country only narrowly escaped a second tipping point after widespread protests. In contrast, Lebanon was able to avert tipping points towards violent conflict during two periods in the recent past (2004–2008 and 2013–present), even though one can speak of a gradual governance breakdown. How, then, can we explain this variance in outcomes given the rather similar presence of risks in all three cases?

Resilience

Societal resilience and its constituting factors – social trust, legitimacy and governance institutions – play a role in moderating risks and avoiding violent conflict and governance breakdown. We now analyse these factors, and the supporting conditions that help explain variant levels of resilience in the three countries.

Social trust

According to the Arab Barometer, 95% of people in Lebanon feel that they “must be very careful in dealing with people”, in Iraq the figure is 91%. Similarly, 81% of Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon feel that “most people are not trustworthy”.Footnote25 Social-trust levels in the region appear compromised. We will now qualitatively investigate central factors in social trust: namely, “inclusive social identities, impartial political institutions and positive interactions between various societal groups”.Footnote26 We analyse these factors from a perspective of “sectarianization”, which has been driving a wedge between individuals regarding generalized social trust, trust between groups as well as interpersonal trust.

Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel point out that sectarianization is a “process shaped by political actors operating within specific contexts, pursuing political goals that involve […] popular mobilization around particular (religious) identity markers”.Footnote27 Sectarianization has been used by politicians to deflect demands for political change, by external powers to gain influence and by local actors to cultivate autonomous power bases. In Lebanon, sectarianism “is deployed to camouflage wide income disparities among regions but also within sects, and to obfuscate debates about the country’s political economy”.Footnote28 In Syria, the Assad regime has used sectarianization extensively to delegitimize protesters and fracture the opposition along sectarian linesFootnote29; ethnicity-based militias that are crucial for regime survival and rival the official army in importance have grown in stature meanwhile, as they have in Iraq as well. Sectarianization flourishes in a context of authoritarianism, limited statehood and contested order, harming the various forms of trust substantially.

Interpersonal trust levels have been compromised in Syria and Iraq by the focus of state power on repression, which contributes to a vivid sense of one’s own insecurity. During decades of despotism under Saddam Hussein, the Iraqi state exposed the population to a high degree of violence and arbitrariness.Footnote30 Generalized trust was fully eroded, and later only haphazardly reconstructed during the emergence of a sectarian hybrid regime after 2003 that grappled with civil war.Footnote31 In Syria, as Abdalhadi Alijla has pointed out, “the long decades of political oppression, lack of political participation and absence of public consultation, in addition to securitization of the public sphere, produced a society of distrust; between the members of the society and in institutions.”Footnote32 A decade later, the country entered a civil war that is still ongoing and has eroded trust on all levels.

In Lebanon’s system of sectarian power-sharing, there is more flexibility – but institutions are not “impartial” and have fostered sectarian identities, clientelism and corruption. Sectarian identities can remain “sticky” even when civil society organizations (CSOs) try to move beyond them. As evidenced by Janine A. Clark and Bassel F. Salloukh, sectarian elites seek to infiltrate CSOs, “[thus] preventing them from effecting political or socioeconomic change at the national level through, for example, legal campaigns to change personal status laws”. The result is, consequently, the preclusion of “any effective mode of cross-sectarian affiliation or political mobilization and the sabotaging of anti-sectarian initiatives in Lebanon”.Footnote33

People both in Lebanon and Iraq are increasingly fed up with these sectarian systems, however. In the latter, protesters have called for a “country” and turned against “toxic and unequal living conditions and corruption”, thus rejecting “the ethno-sectarian political system […] imposed on Iraq after the 2003 US invasion, which controls Iraq’s growing oil-wealth surpluses”.Footnote34 In Lebanon meanwhile, across the whole country people have “protested against both the ruling sectarian elites and the financial elites and banks they see as responsible for the crisis”.Footnote35 In both of these states, protesters have claimed public spaces and reinterpreted them through inclusive community-building.

This leads us to positive interactions between various societal groups. Sectarian identities and the politics of sectarianization in the three countries are evident in the ethnic segregation of urban spaces, which ethnic cleansing during the bouts of civil war would reinforce (e.g. in Baghdad). They manifest also in the ethnic militias emerging during civil wars (e.g. Hezbollah and the PMU), the impediments of personal status law to marriages between different religions and in the declining number of mixed marriages between different sects (e.g. Sunnis and Shi’is in Iraq).Footnote36 The more urbane and affluent strata of Lebanese society go to Cyprus to conduct mixed marriages between members of different religions, a bottom-up practice that indicates a degree of social trust between various societal groups. In more conservative Syria and Iraq, such practices are less common.

The most significant difference might, however, be the “shadow of the past” in Lebanon, namely the painful memory of the civil war. Post-war Lebanon “has been dominated by a politics of forgetting […] without amnesia”,Footnote37 but since the late 1990s there has been “an explosion of creative commemorations and memorializations of the war”.Footnote38 These bottom-up initiatives are not matched by official policies of reconciliation, but the shadow of the civil war is nonetheless present in the official political discourse too – wherein it is often instrumentalized for political purposes. Such political practices construct a collective identity of present-day Lebanese society that perceives the “temporal other” of the not-so-distant past as a constantly looming danger. The shadow of the past is always imminent, which also resonates in the everyday practices of ordinary people – as Sami Hermez’s ethnographic study of this phenomenon shows. People continuously engage in practices of recollecting past violence while anticipating future forms too – “[a] sense of […] living in between past and future violence, remembering one, anticipating the other [in a] seamless duration where recollection and anticipation are simultaneous processes that meld into each other”.Footnote39

These practices do not constitute one monolithic collective memory, but rather a diverse collective remembrance produced by a mosaic of voices; nor do they constitute a memory which clearly distinguishes the past from the present, rather they produce a past always present. The shadow of the past might therefore act as a correlate of generalized social trust, in the form of the collective and ever-present knowledge that “we are in this together”. This awareness does not just “hang in the air”, but also translates into concrete forms and acts of solidarity – as evident, for example, in the substantial civic engagement in Beirut after the port blast.

This shadow of the past was not present in Syria before 2010 and no mechanism for reconciliation currently exists. Meanwhile experts have pointed out how crucial such a process would be to re-establish social cohesion and construct a Syrian identity that is “pluralistic and expressive of Syrian cultural diversity”.Footnote40 In Iraq, reconciliation initiatives to deal with its more recent history of civil war and Baathist repression have been limited. In the immediate aftermath of the US invasion they were not fostered and later they were overshadowed by political calculations. Local tribal reconciliations have been interlaced with state capture and power politics at the national level. Highly transactional, they have been less effective than overtly romantic view of local peacebuilding initiatives might suggest.Footnote41 Indeed – as the MENARA focus group project pointed out, transitional justice is hardly present in Arab countries, except for Tunisia.Footnote42 Nonetheless, it might gradually emerge. For example, Iraqi Prime Minister Khadimi has recently initiated a process of commemoration for the victims of the Yazidi genocide by ISIS. Such efforts are particularly important as turning points towards a cross-sectarian future.

Legitimacy

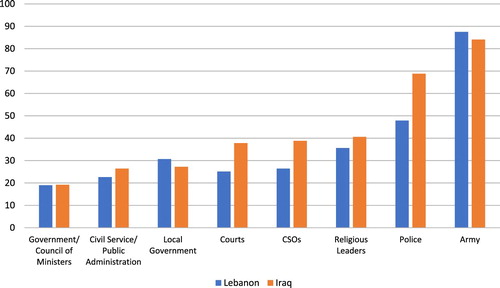

Trust in public institutions, as a proxy for empirical legitimacy, is limited in Iraq and Lebanon according to the Arab Barometer. This is similar for both countries across almost all parameters (in Syria, the survey series has never been conducted to date). Governmental institutions only have the trust of around one-fifth of respondents, with local governments performing slightly better. The same is true for courts, CSOs (both enjoy even lower levels of trust in Lebanon) and for religious leaders. What is striking are the high trust levels in the police (higher in Iraq than in Lebanon), and even more so in the army – even though these institutions lack transparency and have a long history of corruption. Their rankings are possibly reflective of the high degree of insecurity that citizens have to endure and a corresponding prioritization of basic physical security (see below). Overall empirical legitimacy – that is, “social acceptance [by the governed community] of a governance actor’s right to rule” – is low.Footnote43 This low level of trust has also been evident in the protests witnessed in all three countries, and can directly be linked to input and output legitimacy.

Figure 2. Institutional Trust Levels in Iraq and Lebanon (2018). Source: Arab Barometer (2018).

Note: Percentages of respondents who have “a great deal of trust” or “quite a lot of trust” in the respective institutions.

Input legitimacy is most restricted in the case of the Syrian regime, while both Lebanon and Iraq have elections – though they are organized within the framework of a sectarian power-sharing system. Traditional legitimacy based on religious narratives, pedigree and kinship ties that the authoritarian monarchies of the region have cultivated (Gulf countries, Morocco and Jordan) is limited in all three countries. The informal avenues to air grievances that are related to such phenomena (e.g. petitioning in diwans and shura councils) are not available. Lack of input legitimacy helps to explain the response of the Syrian regime to the protests in the country, which focused solely on violence and suppression. Violence against protestors was also deployed in Iraq and less so in Lebanon, but both political systems showed some responsiveness as they reconfigured their respective governments – even though meaningful systemic reform has never been pursued in either. As the MEDRESET elite survey in Lebanon summed it up,

“in terms of domestic issues, corruption and the lack of accountability by political and other elites figures prominently. The persistence of the confessional political system and growing socioeconomic inequalities are also mentioned. The Lebanese are often critical of the state of democracy in their country, and believe their government is working to undermine rather than promote it”.Footnote44

With input legitimacy limited, the focus for regime survival is on output legitimacy instead – especially in Iraq and Syria. Both have enjoyed a degree of it as a result of oil wealth and related transfer payments and development efforts, as inefficient they may be. Syria saw growing oil production in the 1990s, which would peak in the early years of the new century, then halve by 2011, collapsing thereafter due to the conflict. Even the most authoritarian regime with a narrow regime coalition such as Saddam Hussein’s Iraq requires and indeed craves output legitimacy, to achieve a degree of popular legitimacy via welfare policies and maintain the semblance of a functioning economy to demonstrate state capacity.Footnote48

In comparison to Iraq and Syria, hydrocarbons were never a direct option for Lebanon – hopes to develop gas fields in the Mediterranean aside. However, the country has benefitted from the regional recycling of oil rents. It actively solicited such funds from the Gulf region in order to finance reconstruction after the civil war, balance its current account deficit and also to strengthen its military capacities. However, such inflows are greatly reduced today. As a result of low oil prices and Iran-backed Hezbollah playing a role in Lebanese politics, the ability and willingness of Gulf countries to provide such external funds have decreased over time and remittances have come under pressure.

Lack of accountability and allocation efficiency limit output legitimacy, and have been targeted by political protest in Syria, Iraq and Lebanon alike. Syria, as a low-income country, faces tougher constraints. The social crisis in its rural north-east – it started even before a severe drought in the second half of the first decade of the new millennium aggravated it – has been attributed to mismanagement and an economic-liberalization drive that favoured urban cronies at the expense of the countryside.Footnote49 Iraq and Lebanon instead belong to the upper middle-income countries, yet their ability to provide public goods is also hampered. Electricity blackouts and mismanaged waste disposal have been focal points of civil protests in both countries. Lack of such public-goods provision makes reliance on private providers (e.g. of power generators) mandatory, actors whose own commercial interests in turn have an influence on government decisions.

As reliance on oil rents is unsustainable, economic diversification is an urgent if elusive requirement. It is particularly pressing in Iraq and Syria, which both still have considerable population-growth with fertility rates of 4.3 and 2.8 children per woman respectively. In Lebanon, in contrast, the fertility rate has fallen from 5 children per woman in 1970 to 1.7 today, now being below the replacement level of 2.1.Footnote50 Variance in output legitimacy is thus conditioned in major ways by direct and indirect flows of oil rent, implementation efficiency and differences in development levels and demographic factors.

Governance institutions

Some scholars (see the introduction to this Special Issue) have argued that institutional design needs to be inclusive, fair and adequate.Footnote51 Protests have highlighted that this is not the case in any of the three countries, but in Lebanon and to some degree in Iraq institutions are designed in a more flexible way than in Syria so as to: (a) manage ethnic diversity and (b) govern relationships with powerful non-state actors. While this “flexibility” might prevent a spiral into conflict, it works mainly in the interests of maintaining a system that serves sectarian and business elites, rather than the state or citizens for whom it has far-reaching consequences.

According to a prominent strand of the literature, ethnic diversity has a negative effect on public-goods provision.Footnote52 Matthias vom Hau and Guillem Amatller Domine have questioned this line of reasoning as apolitical and ahistorical. It treats ethnic diversity as exogenous, when in reality it is rather an endogenous factor emanating from the relative underdevelopment of state capacity and the retarding effect thereof on ethnic homogenization. Weak state capacity and public-goods provision are more likely to foster ethnic grievances, while strong state capacity and public-goods provision provide incentives for assimilation.Footnote53 Authoritarianism further reduces the ability for flexible adaption and inclusive solutions to political conflict, and has been conducive to a politicization of ethnic diversity.

Iraq, Lebanon and Syria have a high degree of ethnic diversity. Up until the 1980s, Syria and Iraq were governed by populist authoritarian regimes. The state only granted limited autonomy to private sector actors, and dominated the economy via socialist rhetoric and patronage relationships. This period was followed by a transition to a post-populist authoritarianism facilitating economic reform, fomenting crony capitalism and relying on narrower regime coalitions.Footnote54 In Syria this process accelerated during the 2000s after Bashar al Assad came to power. In Iraq the rampant corruption of the sanction years of the 1990s and the ensuing liberalization agenda in the wake of the US occupation in 2003 functioned as catalysts. The post-populist shifts have been accompanied by growing sectarianism. The latter is a symptom of how limited access systems channel influence and scarce resources after they have narrowed regime coalitions and estranged considerable parts of their old bases. It is a risk, not a source of resilience.

This is abundantly clear in Syria, and hopes for change are slim. Exclusiveness, sectarian politicization and the selective allocation of public goods such as electricity to supportive population segments are part of the Assad regime’s business model.Footnote55 Syria’s state capacity was previously excessively focused on bureaucracy, security forces and the supervision of the population. In the conflicts that the post-populist transformation engendered this proved to be an inflexible arrangement, unable to mediate pressures from diverse ethnic groups and different external actors.

In Lebanon, circumstances are different; the same is true in today’s Iraq to some extent. Lebanon never had a comparative trajectory of import-substituting industrialization (ISI) and authoritarian populism that would be followed by structural adjustment. As a small country with a strong tradition of trading, ISI was neither a preference nor an option. Furthermore, Lebanon has no oil resources, and thus no easy fix available in the form of resource capture by elites. Rather, sectarian leaders need to cooperate to facilitate other forms of external inflows – ones that are often based on recycled oil rents, and which need at least a semblance of political stability on the Lebanese market to function (i.e. strategic transfer payments, investments, remittances).

The Lebanese sectarian system was introduced in the late nineteenth century by the Ottomans as a concession to European powers,Footnote56 enshrined in the constitution of 1926 and subsequently entrenched by political practices. While this system embeds sectarianism in the state, it also includes non-state mechanisms in the mediation of domestic crisesFootnote57 and accommodates the interests of external actors (as evident in the fact that Lebanon simultaneously receives money from adversaries such as the US, Iran and Saudi Arabia). Similar flexibility could be observed in Iraq, where the new government was set up to keep both the US and Iran content. Nonetheless, these mechanisms in Iraq and Lebanon also mean that the system is “stuck” and resists reform.Footnote58 It might make the countries resilient in the sense of being capable to adapt to crisis without sliding into conflict, but it does not foster resilience in the sense of exiting the cycle of crises. Rather, it robs locals of agency, by making them reliant on the support of external actors that view sectarian power-sharing as a stabilizing force. It also serves the preservation of power of corrupt elites which enrich themselves at the expense of an inclusive, fair and adequate institutional design.

The centralized but weak nature of MENA states discussed above implies a center–periphery paradox that manifests, among other places, in the institutional relations with powerful non-state actors who either cooperate with the government or have carved out their niche in opposition to it. The state, in turn, structures its relationship with its peripheries not only via stable ordering, which is rigid, rules-based and top-down, but also by fluid ordering, which is open, ad-hoc and horizontal. This occurs either for lack of state capacity or as a deliberate strategy of flexible co-optation under resource constraints in areas that are of reduced importance to a given regime.Footnote59

Regarding Syria, Helle Malmvig has pointed out that “the regime has informally outsourced a defining element in its performance of statehood to foreign and local semi-private agents”, “[which has] enabled the Syrian government to perform and maintain its claim to statehood”.Footnote60 In the case of the other two countries two non-state actors have even greater leeway, namely the PMU in Iraq and Hezbollah in Lebanon. Hazbun has used the concept of “security assemblages” for the case of Lebanon, where a pluralist form of governance over security has been established between the multi-sectarian Lebanese Armed Forces and the Shia Hezbollah.Footnote61 This arrangement has been crucial in their cooperation to drive back ISIS. The same applies to the PMU, which virtually enacted Iraqi statehood as the country’s own military collapsed. While there are important differences to Hezbollah – the PMU represent a heterogeneous organization of various groups – there are crucial similarities from an ALS perspective. As Fanar Haddad has pointed out,

When trying to understand hybrid actors in hybrid States, such as the PMU in Iraq, it is unhelpful to think in terms of rigid binaries between State and non-State, formal and informal, and legal and illicit. Projecting concepts rooted in ideal-type Weberian States onto cases like contemporary Iraq is a futile exercise. The PMU today is very much part of the State: its more powerful figures and formations are key actors in elite politics, electoral competition, the economy (formal and illicit) and in Iraq’s security sector.Footnote62

Conclusions

The comparative analysis of sources of resilience in Iraq, Lebanon and Syria has revealed some significant differences in terms of input legitimacy, the fiscal space to generate output legitimacy (which is partly conditioned by direct and indirect oil revenues as well as demographic dynamics), the flexibility of hybrid governance arrangements to bridge ethnic divides, and elites’ need to cooperate in the attraction of external rents. What sets Lebanon apart is the shadow of the past: the memory of the civil war continuously produced by both politicians and ordinary people as a constituting part of the present. While the collective memory is characterized by its diversity, it acts as a correlate of social trust in the form of the collective knowledge that “we are in this together” and has been linked by scholars to resilience.Footnote63 This social fabric could also be seen in the form of daily solidarity practices following the disastrous Beirut blast.

These findings should be qualified in three respects. First, this article has exclusively focused on countries in the Middle East and their recent history. Comparative studies from other world regions over diverse time periods could increase the generalizability of findings and test core arguments in other settings. Second, more reliability could be added with quantitative evidence, which is relatively scarce in the MENA, as authoritarian regimes are disinclined to share information and have underdeveloped capacities to collect data as far as they are oil exporters as the need for fiscal bureaucracies that reach into society is reduced.Footnote64 Third, in-depth qualitative research in a single case study pursued in an inductive way would also increase the validity of findings. Such an angle might potentially uncover alternate sources of resilience which this research neglected in its deductive approach.

What then do these findings mean from a more practical and policy-oriented perspective? Limited input and threatened output legitimacy seem particularly harmful to resilience, while flexible institutions and, more importantly, collective memory can be crucial factors of resilience. Indeed, all three cases point to the key that reconciliation holds for resilience understood “as transformation”. However, there is no easy way to translate these findings into a policy template; rather any resilience policy needs to be tailored to the respective local context and owned by an array of local actors. Indeed, as this article has laid bare, resilience can be a problematic concept if it only means adaptation to crises. Instead, it must set the stage for a comprehensive, locally driven and inclusive transformation that is not externally imposed. As Lebanese writer Sara Mourad powerfully argued after the port of Beirut blast in August 2020,

Resilience romanticizes our loss and dispossession. It brands our survival, making it an object of fascination for foreigners and inspiration for locals, advertising it as a valorized mode of attachment. Resilience is a marketing stunt for a political and economic system that runs on crises, that manufactures crises in order to sustain itself. Resilience celebrates survival at the expense of justice. It is the rhetorical and symbolic symptom of the normalization of injustice.Footnote65

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniela Huber

Daniela Huber is Head of the Mediterranean, Middle East and Africa Programme at the Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI) and Editor of The International Spectator. She is also adjunct professor at Roma Tre University where she teaches a M.A. course on International Politics. Between 2016 and 2019, she has been the scientific coordinator of the Horizon 2020 project MEDRESET. Her research focuses on the interface of and entanglements between Europe and the Middle East, with a particular focus on decentring the study of European foreign policy theoretically and on EU policies in the Middle East empirically. On these issues, she has published two monographs (Palgrave and State University of New York Press), 13 peer-reviewed articles, 7 edited books, 6 book chapters and numerous research papers and commentaries.

Eckart Woertz

Eckart Woertz is director of the Institute for Middle East Studies (IMES) at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) in Hamburg and professor for contemporary history and politics of the Middle East at the University of Hamburg. He is author of Oil for Food (Oxford University Press 2013), co-editor of the Water-Energy Food Nexus in the Middle East and North Africa (Routledge 2016) and editor of GCC Financial Markets (Gerlach Press 2012). Besides academic publications he has contributed to numerous consultancy and policy reports for clients in the Middle East and at international organizations. Previously he held positions at the Barcelona Centre for International Affairs (CIDOB), Sciences Po in Paris, Princeton University and the Gulf Research Center in Dubai and worked for banks in Germany and the United Arab Emirates in equity and fixed income trading.

Notes

1 Rogers, “The Etymology and Geneaology of a Contested Concept.”

2 Bellin, “The Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East”; Schlumberger, Debating Arab Authoritarianism; Heydemann and Leenders, “Authoritarian Learning and Authoritarian Resilience”; Hill, “Authoritarian Resilience and Regime Cohesion in Morocco after the Arab Spring.”

3 Mouawad, “Unpacking Lebanon’s Resilience.”

4 Alijla, Trust in Divided Societies.

5 Ryan, “Everyday Resilience as Resistance”; Bourbeau and Ryan, “Resilience, Resistance, Infrapolitics and Enmeshment.”

6 Aarts et al., “From Resilience to Revolt.”

7 Dionigi, “The Syrian Refugee Crisis in Lebanon.”

8 Fawaz, “While We Recognize the Refugees Resilience.”

9 Majed, “Interview.”

10 Fakhoury, “After the Beirut Blast”; Ülgen, “Resilience as the Guiding Principle of EU External Action.”

11 Huber and Paciello, “Contesting ‘EU as Empire’ from Within?”

12 Ranj, “Fragility and Resilience in Iraq”; Mouawad, “Unpacking Lebanon’s Resilience.” For a comparison of Libya and Tunisia see Stollenwerk, “Preventing Governance Breakdown in the EU's Southern Neighborhood.”

13 Leenders, “‘Regional conflict formations’.”

14 Börzel and Risse, “Conceptual Framework.”

15 EULISTCO dealt with ALS and contested orders in the EU’s Eastern and Southern neighbourhood (https://www.eu-listco.net/); MENARA dealt with the regional order and domestic transformations in the MENA (http://menara.iai.it/menara-project/); MEDRESET reset our understanding of Mediterranean relations through almost 700 interviews in various policy areas (http://www.medreset.eu/project/).

16 Stollenwerk, Eric, Tanja A. Börzel, and Thomas Risse. “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU's Neighbourhood: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Democratization (2021): Forthcoming.

17 Woertz and Yellinek, “Vaccine Diplomacy in the Middle East.”

18 Issam Fares Institute. “Report of the Focus Group with Stakeholders in the Middle-East,” 3.

19 Börzel and Risse, “Conceptual Framework,” 8–9.

20 Migdal, Strong Societies and Weak States.

21 Mann, “The autonomous power of the state”, Springborg, Political Economies of the Middle East & North Africa.

22 Hinnebusch, “From Westphalian Failure to Heterarchic Governance in MENA,” 395.

23 Makdisi, “Constructing Security Council Resolution 1701 in Lebanon in the Shadow of the ‘War on Terror’,” 163.

24 Halabi and Boswall, “Lebanon’s Financial House of Cards.”

25 Arab Barometer, Arab Barometer Wave V - 2018 and Arab Barometer Wave IV - 2016.

26 Stollenwerk, Eric, Tanja A. Börzel, and Thomas Risse. “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU's Neighbourhood: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Democratization (2021): Forthcoming.

27 Hashemi and Postel, Sectarianization, 4.

28 Salloukh, “The Architecture of Sectarianization in Lebanon,” 224.

29 Pinto, “The Shattered Nation,” 129.

30 Blaydes, State of Repression.

31 Dodge, Iraq: From war to a new authoritarianism.

32 Alijla, Trust in Divided Societies, 166.

33 Clark and Salloukh, “Elite Strategies, Civil Society, and Sectarian Identities in Postwar Lebanon.”

34 Ali, “Iraqis Demand a Country,” 3.

35 Majed and Salman, “Lebanon’s Thawra,” 7.

36 Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, “Iraq: Inter-sect marriage between Sunni and Shia Muslims”; CS Monitor Editorial Board, “Iraq’s Opportunity in the Battle for Mosul”; Scott, “Sectarian Violence in Iraq Slows Mixed Marriages,”

37 Makdisi and Silverstein, Memory and Violence in the Middle East and North Africa, 15.

38 Salloukh, “War Memory, Confessional Imaginaries, and Political Contestation in Postwar Lebanon,” 2.

39 Hermez, War Is Coming.

40 Dashti and Hinnebusch. “Syria at War: Eight Years On,” 33.

41 Watkins and Hasan, “Post-ISIL Reconciliation in Iraq.” Al-Marashi and Keskin, “Reconciliation Dilemmas in Post-Ba'athist Iraq.”

42 Issam Fares Institute. “Report of the Focus Group with Stakeholders in the Middle-East,” 5.

43 Schmelzle and Stollenwerk, “Virtuous or Vicious Circle?,” 456.

44 Goulordava, “Lebanese Elites’ Views on Lebanon and Its Relations with the EU,” 161.

45 Woertz, “Wise Cities” in the Mediterranean?; Cammett, Compassionate communalism: Welfare and sectarianism in Lebanon.

46 Al-Ali, The struggle for Iraq’s future.

47 Phillips, “Sectarianism and Conflict in Syria,” 368.

48 Woertz, “Iraq under UN Embargo.”

49 Selby et al., “Climate change and the Syrian civil war revisited.”

50 United Nations, World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision.

51 Stollenwerk, Eric, Tanja A. Börzel, and Thomas Risse. “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU's Neighbourhood: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Democratization (2021): Forthcoming.

52 Alesina et al., “Fractionalization”, Easterly and Levine, “Africa’s Growth Tragedy.”

53 Vom Hau and Domine, “State Power and the Relationship Between Ethnic Diversity and Public Goods Provision.”

54 Hinnebusch, “Authoritarian persistence, democratization theory and the Middle East.”

55 De Juan and Bank, “The Ba‘athist blackout?”

56 Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism.

57 Carmen Geha has illustrated how Lebanese “non-state institutions devised by the Lebanese zu’ama [have] played a decisive role in maintaining powersharing during the war in Syria, at the same time revealing how state institutions are actually a façade behind which real power-brokers operate and reach agreements, or disagreements, outside the state”. Geha, “Sharing Power and Faking Governance?” 3.

58 Fakhoury, “Power-Sharing after the Arab Spring?”

59 Glawion, The Security Arena in Africa.

60 Malmvig, “Mosaics of Power. Fragmentation of the Syrian State since 2011,” 9.

61 Hazbun, “Assembling Security in a ‘Weak State’.”

62 Haddad, “Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Units,” 31.

63 Hermez, War Is Coming.

64 Pellicier and Wegener, “Quantitative Research in MENA Political Science.”

65 Mourad, “AFTERSHOCK.”

Bibliography

- Stollenwerk, Eric, Tanja A. Börzel, and Thomas Risse. “Theorizing Resilience-Building in the EU's Neighbourhood: Introduction to the Special Issue.” Democratization (2021): Forthcoming.

- Aarts, P., P. van Dijke, I. Kolman, J. Statema, and G. Dahhan. “From Resilience to Revolt: Making Sense of the Arab Spring,” 2012. https://dare.uva.nl/search?metis.record.id=376791.

- Al-Ali, Zaid. The Struggle for Iraq’s Future: How Corruption, Incompetence and Sectarianism Have Undermined Democracy. New Haven; London: Yale University Press, 2014.

- Albera, Dionigi, and Maria Couroucli. Sharing Sacred Spaces in the Mediterranean: Christians, Muslims, and Jews at Shrines and Sanctuaries. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011.

- Alesina, Alberto, Arnaud Devleeschauwer, William Easterly, Sergio Kurlat, and Romain Wacziarg. “Fractionalization.” Journal of Economic Growth 8, no. 2 (2003): 155–194.

- Ali, Zahra. “Iraqis Demand a Country.” MERIP, December 17, https://merip.org/2019/12/return-to-revolution/, 2019.

- Alijla, Abdalhadi M. Trust in Divided Societies: State, Institutions and Governance in Lebanon, Syria and Palestine. London: I.B. Tauris, 2020.

- Al-Marashi, Ibrahim, and Aysegul Keskin. “Reconciliation Dilemmas in Post-Ba’athist Iraq: Truth Commissions, Media and EthnoSectarian Conflicts.” Mediterranean Politics 13, no. 2 (2008): 243–259.

- Arab Barometer. “Arab Barometer Wave IV - 2016.” http://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/data-analysis-tool/.

- Arab Barometer. “Arab Barometer Wave V - 2018.” http://www.arabbarometer.org/survey-data/data-analysis-tool/.

- Bellin, Eva. “The Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Exceptionalism in Comparative Perspective.” Comparative Politics 36, no. 2 (2004): 139–157. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/4150140.

- Bicchi, Federica, and Agnieszka Legucka, eds. “D4.2 - Report on radicalisation, political revisionism, role of migration and demography as sources of threats in the EU’s neighbouring regions and related conditions for resilience”. 2020: unpublished EULISTCO deliverable.

- Blaydes, Lisa. State of Repression: Iraq under Saddam Hussein. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018.

- Börzel, Tanja, and Thomas Risse. “Conceptual Framework: Fostering Resilience in Areas of Limited Statehood and Contested Orders.” EULISTCO Working Paper No 1, 2018. https://www.eu-listco.net/publications/conceptual-framework-fostering-resilience-in-areas-of-limited-statehood-and-contested-orders.

- Bourbeau, Philippe, and Caitlin Ryan. “Resilience, Resistance, Infrapolitics and Enmeshment.” European Journal of International Relations 24, no. 1 (2018): 221–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066117692031.

- Cammett, Melani. Compassionate Communalism: Welfare and Sectarianism in Lebanon. Itahca, London: Cornell University Press, 2014.

- Clark, Janine A., and Bassel F. Salloukh. “Elite Strategies, Civil Society, and Sectarian Identities in Postwar Lebanon.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 45, no. 4 (2013): 731–749. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743813000883.

- CS Monitor Editorial Board. “Iraq’s Opportunity in the Battle for Mosul.” Christian Science Monitor, August 30, 2016. https://www.csmonitor.com/Commentary/the-monitors-view/2016/0830/Iraq-s-opportunity-in-the-battle-for-Mosul.

- Dashti, Rola, and Raymond Hinnebusch. ‘Syria at War: Eight Years On’. UNESCWA, 2020. https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/syria-war-eight-years.

- De Juan, Alexander, and André Bank. “The Ba‘Athist Blackout? Selective Goods Provision and Political Violence in the Syrian Civil War.” Journal of Peace Research 52, no. 1 (2015): 91–104.

- Dionigi, Filippo. “The Syrian Refugee Crisis in Lebanon: State Fragility and Social Resilience.” LSE Middle East Centre paper series, 2016. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/65565/.

- Dodge, Toby. Iraq: From War to a New Authoritarianism. Adelphi Series. London; New York: Routledge for the International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2013.

- Easterly, William, and Ross Levine. “Africa’s Growth Tragedy: Policies and Ethnic Divisions*.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 112, no. 4 (1997): 1203–1250.

- Fakhoury, Tamirace. “After the Beirut Blast, the International Community Must Stop Propping up Lebanon’s Broken Political System.” The Conversation, 2020. http://theconversation.com/after-the-beirut-blast-the-international-community-must-stop-propping-up-lebanons-broken-political-system-144302.

- Fakhoury, Tamirace. “Power-Sharing after the Arab Spring? Insights from Lebanon’s Political Transition.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 25, no. 1 (2019): 9–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2019.1565173.

- Fawaz, Mona. ‘While We Recognize the Refugees Resilience, We Do Not Want to Romanticize the Hardship and Inequality That They Are Still Facing.’ https://T.Co/BNDXUjZVg6.” Tweet. @ifi_aub (blog), September 10, 2018. https://twitter.com/ifi_aub/status/1039147538404831233.

- Geha, Carmen. “Sharing Power and Faking Governance? Lebanese State and Non-State Institutions During the War in Syria.” The International Spectator 54, no. 4 (2019): 125–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2019.1632064.

- Glawion, Tim. The Security Arena in Africa: Local Order-Making in the Central African Republic, Somaliland, and South Sudan. Cambridge, UK, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Goulordava, Karina. “Lebanese Elites’ Views on Lebanon and Its Relations with the EU.” In The Remaking of the Euro-Mediterranean Vision Challenging Eurocentrism with Local Perceptions in the Middle East and North Africa, edited by Aybars Görgülü, and Gülşah Dark, 147–171. Peter Lang, 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.3726/b15448/13.

- Haddad, Fanar. “Iraq’ s Popular Mobilization Units: A Hybrid Actor in a Hybrid State.” United Nations University Centre for Policy Research, 2020. https://cpr.unu.edu/hybrid-conflict.html.

- Halabi, Sami, and Jacob Boswall. “Lebanon’s Financial House of Cards.” Triangle Working Paper Series, 2019. https://www.thinktriangle.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Extend_Pretend_Lebanons_Financial_House_of_Cards_2019.pdf.

- Hashemi, Nader, and Danny Postel. Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East. 1 ed. Oxford; New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Hazbun, Waleed. “Assembling Security in a ‘Weak State:’ The Contentious Politics of Plural Governance in Lebanon Since 2005.” Third World Quarterly 37, no. 6 (2016): 1053–1070. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1110016.

- Hermez, Sami. War Is Coming: Between Past and Future Violence in Lebanon. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017.

- Heydemann, Steven, and Reinoud Leenders. “Authoritarian Learning and Authoritarian Resilience: Regime Responses to the ‘Arab Awakening.’.” Globalizations 8, no. 5 (2011): 647–653. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2011.621274.

- Hill, J. N. C. “Authoritarian Resilience and Regime Cohesion in Morocco after the Arab Spring.” Middle Eastern Studies 55, no. 2 (2019): 276–288. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00263206.2018.1538967.

- Hinnebusch, Raymond. “Authoritarian Persistence, Democratization Theory and the Middle East: An Overview and Critique.” Democratization 13, no. 3 (2006): 373–395.

- Hinnebusch, Raymond. “From Westphalian Failure to Heterarchic Governance in MENA: The Case of Syria.” Small Wars & Insurgencies 29, no. 3 (2018): 391–413. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2018.1455330.

- Huber, Daniela, and Maria Cristina Paciello. “Contesting ‘EU as Empire’ from Within? Analysing European Perceptions on EU Presence and Practices in the Mediterranean.” European Foreign Affairs Review 25, no. Special (2020). https://kluwerlawonline.com/journalarticle/European+Foreign+Affairs+Review/25.4/EERR2020012.

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. “Iraq: Inter-sect marriage between Sunni and Shia Muslims, including prevalence; treatment of inter-sect spouses and their children by society and authorities, including in Baghdad; state protection available (2016-January 2018).” Accessed 25 August, 2020. http://www.refworld.org/docid/5aa916bb7.html.

- Issam Fares Institute. ‘Report of the Focus Group with Stakeholders in the Middle-East’. MENARA Working Document No. 6, 2019. http://menara.iai.it/portfolio-items/report-of-the-focus-group-with-stakeholders-in-the-middle-east/.

- Leenders, Reinoud. “‘Regional Conflict Formations’: Is the Middle East Next?” Third World Quarterly 28, no. 5 (2007): 959–982.

- Majed, Rima, and Lana Salman. “Lebanon’s Thawra.” MERIP, December 17, 2019. https://merip.org/2019/12/return-to-revolution/.

- Majed, Rima, and Lana Salman. “Interview: Beirut Blast Exposed a Global System.” Rs21 (blog), August 30, 2020. https://www.rs21.org.uk/2020/08/30/interview-beirut-blast-exposed-a-global-system/.

- Makdisi, Karim. “Constructing Security Council Resolution 1701 in Lebanon in the Shadow of the ‘War on Terror’.” In Land of Blue Helmets, edited by Karim Makdisi, and Vijay Prashad. University of California Press, 2017. https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520286948/land-of-blue-helmets.

- Makdisi, Ussama. The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon. First edition. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 2000.

- Makdisi, Ussama, and Paul A. Silverstein, eds. Memory and Violence in the Middle East and North Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006.

- Malmvig, Helle. “Mosaics of Power. Fragmentation of the Syrian State since 2011.” DIIS Report 2018:4, 2018.

- Mann, Michael. “The Autonomous Power of the State: Its Origins, Mechanisms and Results.” European Journal of Sociology 25, no. 2 (2009): 185–213.

- Migdal, J. S. Strong Societies and Weak States: State-Society Relations and State Capabilities in the Third World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Mouawad, Djamil. “Unpacking Lebanon’s Resilience: Undermining State Institutions and Consolidating the System?” In The EU, Resilience and the MENA Region, edited by Silvia Colombo, Andrea Dessi, and Vassilis Ntousas. Rome: Edizioni Nuova Cultura, 2017. https://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/9788868129712.pdf.

- Mourad, Sara. “AFTERSHOCK.” Rusted Radishes (blog), August 16, 2020. http://www.rustedradishes.com/aftershock/.

- Pellicier, Miquel, and Eva Wegener. “Quantitative Research in MENA Political Science.” In Political Science Research in the Middle East and North Africa: Methodological and Ethical Challenges, edited by Janine A. Clark, and Francesco Cavatorta, 187–196. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Phillips, Christopher. “Sectarianism and Conflict in Syria.” Third World Quarterly 36, no. 2 (2015): 357–376. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1015788.

- Pinto, Paolo Gabriel Hilu. “The Shattered Nation: The Sectarianization of the Syrian Conflict.” In Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East, edited by Nader Hashemi, and Danny Postel, 123–142. London: C Hurst & Co, 2017.

- Ranj, Alaaldin. “Fragility and Resilience in Iraq.” In The EU, Resilience and the MENA Region, edited by Silvia Colombo, Andrea Dessi, and Vassilis Ntousas. Rome: Edizioni Nuova Cultura, 2017. https://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/9788868129712.pdf.

- Ryan, Caitlin. “Everyday Resilience as Resistance: Palestinian Women Practicing Sumud.” International Political Sociology 9, no. 4 (2015): 299–315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ips.12099.

- Rogers, Peter. “The Etymology and Geneology of a Contested Concept.” In The Routledge Handbook of International Resilience, edited by David Chandler and Jon Coaffee, 13–25. London: Routledge, 2016.

- Salloukh, Bassel F. “The Architecture of Sectarianization in Lebanon.” In Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East, edited by Nader Hashemi, and Danny Postel, 215–234. London: C Hurst & Co, 2017.

- Salloukh, Bassel F. “War Memory, Confessional Imaginaries, and Political Contestation in Postwar Lebanon.” Middle East Critique 28, no. 3 (2019): 341–359. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19436149.2019.1633748.

- Schlumberger, Oliver. Debating Arab Authoritarianism: Dynamics and Durability in Nondemocratic Regimes. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2007.

- Schmelzle, Cord, and Eric Stollenwerk. “Virtuous or Vicious Circle? Governance Effectiveness and Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12, no. 4 (2018): 449–467. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2018.1531649.

- Scott, Simon. “Sectarian Violence in Iraq Slows Mixed Marriages.” NPR.org, 2007. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=15691287.

- Selby, Jan, Omar S. Dahi, Christiane Fröhlich, and Mike Hulme. “Climate Change and the Syrian Civil War Revisited.” Political Geography 60, no. Supplement C (2017): 232–244.

- Sowers, Jeannie. “Environmental Activism in the Middle East and North Africa.” In Environmental Politics in the Middle East, edited by Harry Verhoeven, 27–52. London; New York: Hurst; Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Stollenwerk, Eric. “Preventing governance breakdown in the EU’s southern neighbourhood: fostering resilience to strengthen security perceptions,” Democratization, online first, 2021. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1928079.

- Springborg, Robert. Political Economies of the Middle East & North Africa. Cambridge, UK; Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2020.

- Ülgen, Sinan. “Resilience as the Guiding Principle of EU External Action.” Carnegie Europe, 2016. https://carnegieeurope.eu/strategiceurope/64007.

- United Nations. “World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision.” https://population.un.org/wpp/Download/Standard/Fertility/.

- Uppsala University Department of Peace and Conflict Research. Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), https://ucdp.uu.se/ (accessed 20 September 2020).

- vom Hau, Matthias, and Guillem Amatller Domine. “State Power and the Relationship between Ethnic Diversity and Public Goods Provision.” Working Paper (forthcoming).

- Watkins, Jessica and Hasan, Mustafa. “Post-ISIL Reconciliation in Iraq and the Local Anatomy of National Grievances: The Case of Yathrib.” Peacebuilding (2021).

- Woertz, Eckart. “Iraq Under UN Embargo: Food Security, Agriculture, and Regime Survival.” Middle East Journal 73, no. 1 (2019): 92–111.

- Woertz, Eckart. “Wise Cities” in the Mediterranean? Challenges of Urban Sustainability. Colección Mongrafías Barcelona: CIDOB, 2018.

- Woertz, Eckart, and Roie Yellinek. “Vaccine Diplomacy in the Middle East.” Middle East Institute (2021). https://www.mei.edu/publications/vaccine-diplomacy-mena-region.