ABSTRACT

The EU is surrounded by areas of limited statehood (ALS) and contested orders (CO) in its southern and eastern neighbourhood. Resilience has become a focus of attention in the academic debate on how to successfully deal with ALS and CO. Moreover, resilience-building is a new cornerstone in the EU’s foreign and security policy. However, to what extent is resilience a mechanism to cope with ALS and CO? What are the sources of resilience? To what extent does the EU act as a resilience builder or spoiler in its neighbourhood? By presenting a new conceptual framework for analysing the interplay between risks, resilience, and governance breakdown/violent conflict as well as through in-depth empirical evidence, this special issue puts forward three key arguments. First, resilience is a key mechanism to prevent governance breakdown and violent conflict in the EU’s neighbourhood. Second, three sources are key in building resilience: Social trust within societies and communities, legitimacy of (state and non-state) governance actors and institutions, as well as effective, fair, and inclusive governance institutions. Third, if external actors, such as the EU, seek to build resilience, they need to factor in long-time horizons, in-depth local knowledge, and a clearly designed strategy.

Introduction

The EU is surrounded by areas of limited statehood at its eastern and southern borders where central state authorities lack administrative capacities and/or do not fully hold the monopoly of the use of force. Another frequent phenomenon in the EU borderlands are order contestations with state, external, and non-state actors challenging the rules of the political game according to which societies are organized. In short, areas of limited statehood (ALS) and contested orders (CO) are the default condition in the EU’s neighbourhood. The unresolved conflicts in Eastern Ukraine and regarding South Ossetia and Abkhazia in Georgia exemplify these dynamics in the EU’s eastern neighbourhood. Its southern neighbourhood is equally plagued by limited statehood and violent order contestations as developments in Libya and Algeria demonstrate.

For a long time, democracy promotion and state-building was considered the main remedy for tackling governance breakdown and violent conflict in areas of limited statehood. This approach has by now been debunked as both ineffective and illegitimate.Footnote1 At the same time, scholarly work has demonstrated that, first, areas of limited statehood are neither ungovernable nor ungoverned and, second, effective and legitimate governance is possible even under rather adverse conditions of limited statehood.Footnote2

In the meantime, resilience has become a focus of attention as a way to tackle ALS and CO. For many years, resilience has been a key topic in other disciplines, including psychology or public health.Footnote3 Democratization published a first special issue on the “Resilience of Democracy” already in 1999. A second special issue on “Resilience of Democracies: Responses to Illiberal and Authoritarian Challenges” came out in 2021.Footnote4 These and other works demonstrate a more elaborate effort to grapple with the concept in the political and social sciences.Footnote5 This special issue complements the one on “Resilience of Democracies” by focusing on challenges to societal resilience in areas where statehood is limited and democracy is contested in the EU’s eastern and southern neighbourhoods.

Broadly understood, resilience is the capacity to cope with, adapt to, and recover from various external and internal challenges.Footnote6 Hence, in order for societies to successfully deal with risks that emanate from ALS and CO in a peaceful manner, resilience is an essential mechanism. More often than not, though, it is unclear what academics have in mind when they talk about resilience. The concept tends to be undertheorized and remains vague, meaning different things to different people.Footnote7 We also know little about the sources and consequences of resilience both from a conceptual and from an empirical perspective.

Resilience-building has also become the EU’s new approach in dealing with ALS and CO in its eastern and southern neighbourhoods. The EU Global Strategy (EUGS) turned resilience into one of the cornerstones of EU foreign and security policy.Footnote8 Yet, the EUGS invites for various interpretations of what resilience means and what the concrete implications are for EU foreign and security policy.

Against this background, this special issue focuses on resilience as the capacity of societies, communities, and individuals in the eastern and southern European neighbourhoods to anticipate, cope with, adapt to, and recover from various external and internal challenges in ALS and CO including challenges to democracy and democratization as well as global and diffuse risks such as climate change.Footnote9 We hypothesize that resilient societies should be able to sustain effective governance and peace under conditions of limited statehood and contested orders. Therefore, the authors of this special issue ask three interrelated questions:

To what extent does societal resilience help prevent violent conflict and governance breakdown in areas of limited statehood and contested orders in the EU’s eastern and southern neighbourhoods?

What are the sources of resilience?

To what extent and under which conditions does the EU act as resilience builder or spoiler in its eastern and southern neighbourhoods?

The special issue puts forward three key arguments. First, we confirm that societal resilience constitutes a key mechanism to prevent governance breakdown and violent conflict in the EU’s neighbourhood, while enabling effective governance and peace. If societies display a sufficient degree of resilience, they are able to fend off risks and to cope with these risks in a peaceful and adaptive way. No or too little resilience allows risks to become immediate threats leading to violent conflict and/or governance breakdown. Second, three interrelated sources are crucial in building resilience: Social trust within societies and communities, legitimacy of (state and non-state) governance actors and institutions, as well as effective, fair, and inclusive governance institutions. Third, if external actors, such as the EU, seek to build resilience, they need to factor in long-time horizons, in-depth local knowledge, and a clearly designed strategy. Strengthening resilience does not happen overnight, but is a long-term project due to the deep societal changes it requires. Moreover, local knowledge is essential to foster resilience and in order to strengthen all three sources of resilience adequately. If we use these criteria to assess the EU’s resilience-building strategies, the record is decidedly mixed, as the contributions to this special issue demonstrate.

The core arguments of our special issue speak to several existing research gaps. First, our theoretical contribution is a deeper understanding of resilience. We provide a conceptual framework on the sources and consequences of resilience. We demonstrate how resilience is able to push back against risks of limited statehood and order contestations and helps to avoid violent conflict as well as governance breakdown. While this special issue focuses on the EU as an external governance actor in its eastern and southern neighbourhood, the conceptual framework is applicable beyond the EU.

Second, our understanding of societal resilience is directed against interpretations of resilience focusing predominantly on the state and its capacities to fend off external and internal challenges. Such conceptualizations have all too often supported the stabilization of autocratic and repressive regimes, which abound in the EU’s eastern and southern neighbourhoods. Since state capacity as such might undermine societal resilience in autocratic and repressive regimes, regime type matters; fostering transparent, participatory, and legitimate governance is key to societal resilience-building. In other words, the more democratic the state, the more it can enable societal resilience.Footnote10 At the same time, there is a feedback loop between societal resilience which requires collective action capacities of communities and individuals, and democratization.

Third, we provide novel empirical insights from both the EU’s eastern and southern neighbourhood. We show how resilience plays out in diverse empirical contexts and how a diverse set of state, external, and non-state actors can help building it. At the same time, we demonstrate how domestic and external governors can undermine resilience pointing out complex social and political dynamics for EU engagements in its neighbourhood. Last not least, we draw on our theoretical and empirical work to spell out policy implications for the EU and its member states.

This introduction proceeds in three steps. First, we define our main categories and present our conceptual framework. Second, we elaborate on how external actors can act as resilience builders or spoilers with special emphasis on the EU. In this context, we distinguish the concept of resilience-building from earlier state-building and stabilization strategies and also discuss how resilience-building relates to democracy and human rights promotion. Third, we outline the structure and contributions of the special issue.

The conceptual framework: limited statehood, contested orders, and societal resilience

Areas of limited statehood and contested orders

Areas of limited statehood (ALS) and contested orders (CO) constitute the environment in which we analyse the role of resilience and the relationships between the central variables of this special issue. ALS are areas in which central government authorities and institutions are too weak to set and enforce rules and/or do not control the monopoly of the use of force.Footnote11 ALS can refer to parts of a country’s territory or to particular policy areas in which state authorities are incapable to enforce the rules. The Donbas region of Ukraine partly controlled by Russian separatists or the Libyan territories not controlled by the Libyan state, but by Khalifa Haftar and the Libyan National Army (LNA), are prominent examples of ALS. As to policy areas, the Covid-19 pandemic has turned many parts of the EU neighbourhood, but also highly industrialized countries into areas of limited statehood, since it overwhelmed the capacities of public health services. The common discourse surrounding so-called “failed” or “fragile” states overlooks that areas of limited statehood where state authorities are too weak to provide effective governance, are ubiquitous in the contemporary international system, while consolidated statehood constitutes the exception to the rule.Footnote12 This is particularly true for the EU’s eastern and southern neighbourhoods. There are very few consolidated states in the EU’s neighbourhood where central state authorities are able to enforce central decisions in most of the territory and with regard to most policy areas. In Ukraine, Georgia, Syria, or Libya, the state has partly even lost the monopoly of the use of force. In sum, ALS serve as a context condition for our inquiry in the EU’s southern and eastern neighbourhood.

Contested orders (CO) refer to situations in which state and non-state actors challenge the norms, principles, and rules according to which societies and political systems are or should be organized. In other words, CO are incompatibilities between two or more competing views about how political, economic, social, and territorial order should be established and sustained. At the global and regional level, powers such as Russia, China, and increasingly Turkey challenge democratic and rule of law-based orders. Domestically, Western and non-Western societies struggle with the rise of populist forces that question their current political and legal order from the inside. Poland and Hungary only constitute the tip of the iceberg within the EU.Footnote13 CO might not be as ubiquitous as ALS in the contemporary international system; but they are fairly common, particularly in the EU’s eastern and southern neighbourhoods. CO constitute the second context condition for our analyses.

We contend that neither ALS nor CO have to necessarily result in governance breakdown or violent conflict. Some degree of order contestations is constitutive for liberal democratic states, as long as they are dealt with in a peaceful manner. By the same token, ALS are neither ungoverned nor ungovernable. As we have shown elsewhere in detail, some areas of limited statehood are reasonably well governed by a whole variety of actors – state and non-state, domestic/local and international, while others are not.Footnote14 In many cases, international organizations, (I)NGOs, and even private companies as well as rebel groups and other violent non-state actors step in where the state authorities fail to deliver common goods and services.Footnote15 The EU’s eastern and southern neighbourhoods are no exception in this regard, as the case studies in this special issue demonstrate.

It follows that the challenge for EU foreign policy is to foster conditions in which order contestations do not contribute to governance breakdown or violent conflict in areas of limited statehood. ALS and CO are the default context condition in the EU’s eastern and southern neighbourhood. Neither limited statehood nor contested orders are likely to go away. They create vulnerabilities and pose risks, but ALS or CO do not in themselves amount to immediate threats for the countries and regions in question or for European security in general. Only if and when areas of limited statehood and contested orders deteriorate into governance breakdown and violent conflict (as, e.g. in Libya), do the risks turn into threats for the respective country or region, but also for the EU. For much of the 2000s, state-building has been the main paradigm for external actors to deal with ALS and CO. The strategy has failed – examples in the EU’s neighbourhood abound from Libya to the Western Balkans to Ukraine.Footnote16 The EU’s record as a democracy promoter is also decidedly mixed.Footnote17 Most recently, this has contributed to the EU’s change of strategies towards resilience-building.Footnote18 This leads us to our third concept in our framework, (societal) resilience.

Resilience

While the concept of resilience has entered the political discourse including the EU’s Global Strategy (see below), it increasingly risks becoming an empty signifier which can mean anything. However, as mentioned above, there has been a long discussion on resilience and its sources in the social sciences which is compatible with our two main context conditions of ALS and CO.Footnote19 As Korosteleva and Flockart point out, resilience “is about having the necessary elements in place that can facilitate reflexivity and self-organization, to amplify an entity’s inherent strength, awareness of the outside […] and its purpose and ambition”.Footnote20 Moreover, “resilience ought to be seen as a form of ‘self-governance,’ which places the emphasis on the ‘local’ and the ‘person’ in inside-out processes of learning and capacity-building to help a self-referential agency to find its own equilibrium”.Footnote21 Thus, we conceptualize (societal) resilience as the capacity of societies, communities, and individuals to deal with opportunities and risks in a peaceful manner. While this understanding is rather general and abstract, it has important implications.

First, non-resilient societies and/or authoritarian states can be stable. Efforts to support these societies and state institutions would lead to stability, but not to resilience precisely because they do not have the ability to peacefully transform and adapt. Resilience produces the capacity to cope with risks and to manage social change peacefully.Footnote22 Hence, resilience must not to be confused with stability.

Second, while the state might contribute to societal resilience, we emphasize (local) communities, non-state as well as external actors. This means that there can be resilient societies without the state. This is particularly significant in areas of limited statehood where the state is too weak to implement and enforce decisions and where other actors have to provide governance and public services in the absence of viable state institutions. Resilience enables societies, communities, and individuals developing the collective action capacity to provide governance in the absence of a functioning state, i.e. effective rule-making and the provision of common goods and services. Resilience also empowers them to cope with external and internal order contestations in a peaceful manner and to ensure effective governance despite these contestations.

Finally, societal resilience is not static. It is first and foremost about change as well as pro-active adaptation and the ability to anticipate and to deal with risks, including “unknown unknowns”. It follows that societal resilience cannot be measured independently from the risks it is supposed to deal with, e.g. humanitarian disasters, health crises such as Covid-19, large-scale cyber-attacks, and the like.Footnote23

Three sources of resilience

Social trust: We hold that in order to arrive at resilience, three sources are essential. The first source is social trust. We understand trust as “a cooperative attitude towards other people based on the optimistic expectation that others are likely to respect one’s own interests”.Footnote24 Social trust can be subdivided into three components: individual trust, group-based trust, and generalized trust. While individual trust relies on regular face to face interaction, group-based trust builds on shared group identity and membership, and generalized trust works independently of face to face interaction and group membership.Footnote25 Moving from individual trust to group-based trust to generalized trust, trust relationships become more inclusive in terms of “imagined communities” where members do not know, but trust each other.Footnote26 This also means that out-group biases decrease and the in-group grows larger.Footnote27 For resilience, trust relationships that are as encompassing and as inclusive as possible are most relevant, since they enable societies to engage in peaceful change in the face of risks. Moreover, social trust enhances the capacity of communities to overcome collective action problems and ensure effective governance, even in the absence of a functioning state.Footnote28

Legitimacy: Legitimacy of governance actors and institutions is a second source of resilience, whether state or non-state. Legitimacy bestows the “license to govern” to particular actors and institutions. The empirical legitimacy of governance actors understood as the social acceptance they enjoy among the governed populationFootnote29 is key in preventing governance breakdown and violent conflict.Footnote30 If people accept governance actors and institutions as legitimate, they will comply with their rule and orders even if they do not agree with every action or order in all instances. If governance actors are considered legitimate, they do not have to rely on more costly mechanisms for compliance and cooperation, such as coercion, since legitimacy renders permanent monitoring of compliance obsolete.Footnote31 Legitimacy is of particular relevance for governance actors in areas of limited statehood to acquire compliance and cooperation in the absence of effective enforcement capacities.Footnote32 Legitimacy as a source of resilience also provides the link to democracy and democratization. Autocratic governance by definition must rely mostly on “output legitimacy” through effective service provision, since its “input legitimacy” through citizens' participation and the like is extremely limited.Footnote33

Institutions: The design of (particularly non-state) governance institutions is a third source of the resilience of societies and communities. Here, we concentrate on political or governance institutions, that is, institutions designed for rule-making and/or the provision of public goods and services. Governance institutions – from (non-state) judicial systems to educational institutions, or public health governance – must be “fit for purpose” in order to be effective. This is a straightforward functional argument which – in international relations – has been made by rationalist institutionalistsFootnote34, and also resonates with institutional approaches based on “rational design”.Footnote35 Yet, there is no “one size fits all” design for governance institutions in areas of limited statehood and contested orders. The organizational rules and procedures of governance institutions have to be flexible enough to enable social learning and to adapt to changing circumstances. Flexibility and functionality apply to both state and non-state institutions, the latter being particularly important in areas of limited statehood. Finally, governance institutions can be supported by external actors, such as the EU, under the condition that the external actors enjoy sufficient legitimacy on the ground (see above).Footnote36

Our conceptual framework

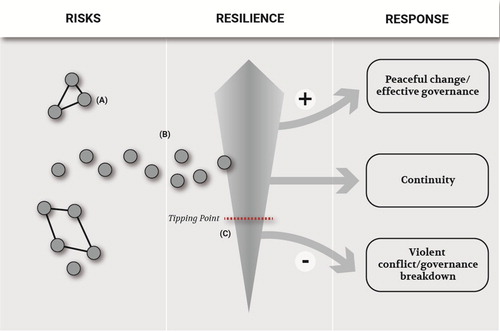

How do societal resilience and its sources help prevent governance breakdown and violent conflict in the EU’s southern and eastern neighbourhoods which are characterized by areas of limited statehood and contested orders? depicts our conceptual framework. We treat ALS and CO as context conditions in the EU’s neighbourhood which are unlikely to change any time soon – from Eastern Europe to the Western Balkans, the Southern Caucasus, the Middle East, and North Africa.Footnote37 As argued above, ALS and CO per se are neither ungovernable nor ungoverned in most cases. Whether ALS and CO result in governance breakdown or violent conflict depends on the degree of societal resilience to fend off the various risks entailed.

The outcome variable of our framework i.e. the response has three categories: peaceful change/effective governance, continuity, and violent conflict/governance breakdown. Only, the last category can become a threat to security as well as to political and social stability of the respective regions, countries, as well as the EU and its member states. The key independent variables are risks affecting the EU neighbourhood and thereby indirectly also the EU. Societal resilience presents a moderating variable predicting how strong the effects of risks on societies are and what kind of societal response we ought to expect. We will now discuss our framework one by one.

Risks and resilience

Risks are omnipresent in the EU’s neighbourhood and on a global scale.Footnote38 Such risks can individually affect a society (see (B) in ) or in groups and bundles (see (A) in ). In other words, risks can come alone or in interconnected groups. Risks and resilience affect tipping points in opposite directions. While risks make tipping points and therefore governance breakdown and violent conflict more likely, resilience renders reaching such tipping points less likely. Whether risks turn into threats in areas of limited statehood and contested orders depends on the extent to which societal resilience can successfully contain global and diffuse risks at the local, domestic, and regional level.

We distinguish between global, diffuse, and regional risks.Footnote39 Global, diffuse, and regional risks can originate from particular actors and countries inside and outside of Europe’s immediate proximity. For instance, governance breakdown and violent conflict in Afghanistan and in Mali or the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) might spill over into the European neighbourhoods. In a similar vein, nuclear proliferation in the Middle East following a final breakdown of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) with regard to Iran if it occurred, might equally translate into threats to European security, as might violent conflicts in the European Eastern neighbourhood, e.g. involving Eastern Ukraine, South Ossetia, or Abkhazia.

Diffuse risks are non-territorial and often hard to ascribe to particular actors. Examples are climate change and cyber coercion. Cyber-attacks on critical infrastructure in the EU’s neighbourhood are a risk to the EU as such attacks can have severe economic and security spillover effects. In most cases, global, diffuse, and regional risks affect Europe’s security indirectly, namely via areas of limited statehood and contested orders by leading to governance breakdown and violence. A case in point is the strategic rivalry between Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Turkey and its consequences for the violent conflict and order contestations in Syria.Footnote40 The war in Syria does not threaten European security per se, but mostly its social and political stability through its spillover effects, e.g. refugee flows. Climate change as a more diffuse risk does not constitute a security threat to Europe as such either. However, it might affect European security through, e.g. water conflicts in the EU’s Southern surroundings, particularly North and Sub-Saharan Africa. We focus on the interconnections between global, regional, and diffuse risks, on the one hand, and areas of limited statehood and contested orders in Europe’s surroundings in the East and the South, on the other.

Responses and resilience

We hypothesize that societal resilience as defined above is essential to ensure peaceful change and effective governance. In a society with high levels of resilience, risks that affect these societies will not result in governance breakdown and/or violent conflict. Rather, a high or at least sufficiently high level of societal resilience will increase the ability to fight off those risks and lead to peaceful adaption and change within a society as well as allow for effective governance. In short, resilient societies are able to cope with risks in a peaceful and adaptive manner, preventing governance breakdown and/or violent conflict. Having only a medium level of societal resilience may allow fending off risks. However, such a degree of resilience may only be enough to keep the pre-risk status quo and result in continuity. Societies remain exposed to risks and run constant danger of those risks turning into threats i.e. governance breakdown and/or violent conflict. An example of where some resilience is present, but societies are nevertheless constantly struggling with varying risks is Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH). Here, despite the long-term commitment by the EU to help foster resilience, societal resilience remains limited keeping society vulnerable to risks, including social segregation and ethnic tensions.Footnote41

If societal resilience is too low or completely absent, risks can set off violent conflict and governance breakdown. In such a scenario, the degree of resilience reaches a tipping point where societal resilience falls under a crucial threshold below which societies are no longer able to fend off and successfully cope with risks (see (C) in ). Thereby, these risks result in violent conflict and/or governance breakdown. An overall breakdown of governance implies a substantial under-provision or complete lack of basic public goods and services. For example, an Ebola outbreak in West Africa does not constitute a threat to societies per se. Governance breakdown only occurs if affected states as well as regional and international organizations are unable to contain and neutralize the disease, as it happened in Liberia and Sierra Leone in 2014. There, the outbreak threatened the security and stability of the region. Likewise, contested orders only turn violent if domestic conflicts over what constitutes a “good public and political order” undermine the legitimacy of a regime to an extent that it loses support of key parts of society and relies on repression of dissent to set and enforce its rule. This may eventually trigger violent opposition by those political forces that seek to establish a different order, resulting in popular uprisings or civil war. The loss of legitimacy for the autocratic regime in Libya in the wake of the Arab Spring as well as the following violent developments in the country illustrate these dynamics.Footnote42

In sum, governance breakdown and violent conflict are instances where

state, non-state, and external/international actors do not provide sufficient public goods and services (anymore), and/or

multiple violent non-state actors fight with state actors or among themselves over the control over territory, and/or

conflicts about domestic/international order turn violent.

The tipping points that determine when risks turn into threats are to a large degree context-dependent (see (C) in ). To understand and analyse such tipping points, we need to take local circumstances and different combinations of factors into account. The specific nature of the risk(s) as well as the level of societal resilience are decisive in this regard. For instance, droughts and water scarcity represent a more significant risk in the EU’s southern neighbourhood than in the eastern neighbourhood regardless of the degree of societal resilience in the eastern neighbourhood countries. Reaching a tipping point leading to governance breakdown/violent conflict through droughts and water scarcity is more likely in many parts of the EU’s southern neighbourhood than in the eastern neighbourhood. In short, risks and resilience affect tipping points in opposite directions with resilience making such tipping points less likely and risks making them more likely. We cannot determine specific events or dynamics that produce such a tipping point with absolute certainty. Yet, it is nevertheless possible and valid to identify events and dynamics that increase the likelihood for a tipping point to occur. For example, societal resilience in Jordan and Turkey has so far helped cope with migration influx from Syria. However, Özçürümez warns that if resilience levels should drop and/or migration pressures increase significantly, this may constitute a tipping point resulting in governance breakdown/violent conflict.Footnote43 Other examples include latest research on forecasting violent conflict, which analyses factors predicting future violent events with a certain likelihood.Footnote44 Single events, such as the withdrawal of foreign troops and/or INGOs from a country, can mark a tipping point. The same holds true for pandemics such as Covid-19. Other potential tipping points build up more slowly over time, such as large scale (youth) unemployment in Tunisia or Algeria.Footnote45

The EU as a resilience builder in its neighbourhood

The EU has embraced the concept of resilience in its 2016 Global Strategy (EUGS) replacing earlier foci on state-building, democracy promotion, and stabilization. It defines resilience as the “ability of states and societies to reform, thus withstanding and recovering from internal and external crises.”Footnote46 While this understanding remains rather vague, the following conceptualization is close to our own. Resilience concerns the capacity of

individuals, communities, institutions, and countries to better prepare for, withstand, adapt to and quickly recover from political, economic, and societal pressures and shocks, natural or man-made disasters, conflicts and global threats; including by reinforcing the capacity of a state – in the face of significant pressures to rapidly build, maintain or restore its core functions, and basic social and political cohesion and of societies, communities and individuals to manage opportunities and risks in a peaceful and stable manner and to build, maintain or restore livelihoods in the face of major pressures.Footnote47

The key arguments this special issue advances have direct implications for external actors in general, and for the EU trying to foster resilience in its neighbourhood in particular. First, as societal resilience prevents violent conflict and governance breakdown, external actors need to invest sufficient resources for fostering it. Since resilience is a fairly new focus in EU foreign and security policy, this also implies a steep learning curve on the side of the EU in order to avoid policy failure in its neighbourhood. Fostering resilience requires long-term engagements and sufficient material and immaterial resources. Building resilience does not happen overnight and is not “free of charge”. The Eastern Partnership or the various partnerships the EU has built with African countries (e.g. on migration, mobility, and employment) provide institutional frameworks for resilience-building. As the contributions to the special issue show, however, they need better funding and target the sources of societal resilience more systematically. For instance, through the EU Association Agendas and the 20 Deliverables for 2020 (20 for 2020) the EU seeks to strengthen resilience in Georgia and Ukraine. However, the track record of these initiatives remains mixed so far.Footnote51 Another example, is the 3RP (Refugee Resilience and Response Plan), which aims to provide an extensive approach to forced displacement in countries such as Turkey, Jordan, or Lebanon. The EU has been a key supporter and donor of the 3RP, but the effectiveness of the initiative in fostering resilience remains largely unclear.Footnote52 If resilience-building is just an excuse for no longer investing in democracy assistance and human rights, it easily becomes an empty signifier.Footnote53

Most important, resilience-building moves away from state-centric approaches towards governance-building and peace-building “from below” and “bottom up”. Resilience-building puts societal actors, local communities, and even individuals front and center of the strategy.Footnote54 If taken seriously, it requires the EU to essentially overhaul its overly state-centric strategies of capacity-building towards strengthening the adaptive capacities of societies and local communities in its eastern and southern neighbourhoods. Resilience-building entails engagement with non-state actors, including non-state justice institutions and even violent actors. As the articles in this special issue demonstrate, it remains unclear whether the EU and its member states are both willing and capable of doing just that.Footnote55 The situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina exemplifies this. Despite the EU’s commitment to build resilience, the track record is mixed at best. Risks continue to affect the country and strong long-lasting societal resilience is yet to be reached.Footnote56 Another example are EU efforts to strengthen resilience in Georgia and Ukraine. Although the EU managed to strengthen resilience and helped fend off domestic risks in both countries, it largely failed to mitigate geopolitical risks such as Russian interference.Footnote57

Second, as the sources of resilience are multidimensional, external actors need to address a diverse set of sources to foster societal resilience successfully. Regarding capacity-building, effective, fair, transparent, and inclusive political processes and institutions are key in fostering societal resilience. The foreign aid programmes of the EU and its members states claim to do just that. It then depends on the local circumstances in the EU’s neighbourhoods, whether to invest in state or non-state institutions to provide common goods and services – from public health to education and even security. Effective, flexible, and fair governance institutions are of primary importance for resilience-building, irrespective of whether these are state or non-state institutions. In fact, central state authorities often act as governance spoilers in ALS, as the example of Belarus has amply demonstrated. The Lukashenko regime has not only suppressed the order contestations of civil society and democratic opposition movements, but has also contributed to governance breakdowns on a large scale.

Fostering the legitimacy of governance actors and institutions is another key factor in resilience-building. Earlier efforts of democracy-promotion by the EU have been largely state-centric using the Western model of liberal democracy as the blueprint.Footnote58 Resilience-building does not entail giving up on the EU’s values of human rights, democracy, and the rule of law. However, it requires a focus on building inclusive, fair, and transparent governance institutions, whether state or non-state, that enjoy broad acceptance among local populations. Democracy promotion “from the bottom up” redirects attention to participatory institutions in local communities rather than mostly concentrating on free and fair elections.

Last but not least, social trust constitutes another crucial source of societal resilience. Various studies have shown in this context that people develop generalized trust, the more they experience inclusive, fair and transparent governance institutions.Footnote59 In other words, a focus on capacity-building with regard to such governance institutions (see above) will probably have positive effects on trust-building as a source of resilience. The EU has various means at its disposal with regard to institution-building to enhance social trust within local populations. For example, efforts by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) helped building inclusive schools in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and to establish Dialogue Platforms bringing together civil society, citizens, and government partners, which has strengthened social trust.Footnote60 Similar approaches and activities would be viable options for the EU in order to help foster resilience.

Third, since the tipping points for governance breakdown and violent conflict are context specific, external actors, such as the EU, need to invest knowledge and resources in a broad anticipatory monitoring of foreign environments. Possessing in-depth regional and local knowledge of political and societal conditions where the EU seeks to foster resilience is of the essence in order to increase its chances for success. At the moment, the EU and its member states have mostly focused on building up monitoring capacities for assessing global and regional risks as well as potential crises. Equally strong efforts have to be put into developing monitoring and information capacities with regard to the sources of societal resilience in the various eastern and southern neighbourhoods. In many instances, “resilience monitoring” can be done from the outside and does not require permission by – often corrupt – state governments. In sum, we not only need crisis-monitoring, but also regular assessments of societal resilience.Footnote61

Finally, external actors can also act as resilience spoilers. Activities of other external actors can undermine EU efforts to build resilience. The situation in Libya serves as an example.Footnote62 The Government of National Accord (GNA) and the Libyan National Army (LNA) fought over who legitimately represents the Libyan state. The EU and most of her member states supported the UN backed GNA in Tripoli. It presents a challenge to any EU effort to build resilience that other external actors, including Russia or Egypt, back Khalifa Haftar and the LNA.Footnote63 Moreover, the EU and its member states can be resilience spoilers themselves. While France has backed the LNA, the EU and other member states have supported the GNA government in Tripoli officially recognized by the UN.

Through engagements in environments as diverse as Ukraine, Georgia, Libya, the Balkans or Mali, the EU has the potential to strengthen resilience in a broad variety of contexts.Footnote64 However, building resilience is largely a domestic process where local state and non-state actors take center stage. The EU and her member states cannot, nor should they be expected to build resilience as external actors by themselves and from scratch. They can promote resilience in the eastern and southern neighbourhood through contributing material, human, and immaterial resources such as training missions or aid. Their efforts to help build effective institutions need to be based on the condition that these institutions are fair, transparent, and open. If the EU makes its financial and political support for state institutions conditional on such domestic (state) institutions becoming (more) impartial towards their citizens and societal groups, this may increase social trust between citizens in the respective country or area.

Structure of the special issue

The following in-depth case studies speak to our theoretical foundation offering broad empirical evidence from the EU’s southern and eastern neighbourhood. Magen and Richemond-Barak argue that it is necessary to systematically integrate global and diffuse risks into explanatory logics of governance breakdown and violent conflict to develop better predictive models and resilience-building strategies. Their contribution presents a six-cluster typology of global and diffuse risks, and highlights three distinct types of tipping-points that can overwhelm societal resilience.

By comparing Iraq, Lebanon and Syria Huber and Woertz find that limited input and threatened output legitimacy are harmful to resilience, while collective memory, reconciliation, and flexibility of institutions are crucial for resilience. Their findings caution that resilience should not only mean the capability to adapt to crises but also needs to set the stage for comprehensive and inclusive transformations that are locally rooted.

Stollenwerk uses original survey data to analyse the extent to which societal resilience helps to prevent governance breakdown in Libya and Tunisia. His article shows that limited statehood and order contestation do not necessarily lead to a breakdown of security governance. Social trust and the legitimacy of governance actors are two main sources of resilience helping to prevent governance breakdown.

Özçürümez examines the EU’s effectiveness in fostering societal resilience in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. She argues that the EU has been moderately effective in building societal resilience due to several constraints the EU faces, including the extent to which the host countries perceive the EU as a legitimate external actor, and the context-specific risks in the host countries.

Bargués and Morillas consider the extent to which the EU has helped enhance societal resilience in Bosnia and Herzegovina. They conclude that the record of resilience building is mixed and that the EU intervention is resulting in continuity – a process of only slow progress that is increasingly perceived as frustrating for the local population – rather than peaceful change.

Kakachia, Legucka, and Lebanidze assess the EU’s performance in promoting societal resilience in Georgia and Ukraine. While Ukraine and Georgia possess a moderate degree of societal resilience, both countries suffer from a high exposure to domestic and external risks, making them dependent on external resilience-building support from the EU. The analysis underlines the EU’s mixed record of resilience-building in the EU’s eastern neighbourhood.

Bressan and Bergmaier compare the role that resilience plays in crisis early warning in diplomatic services at the EU and member state level in France and Germany. They find that member states see value in complementing risk analysis with a resilience perspective, but also that the EU has so far failed to provide a sufficiently clear and coherent source model of resilience for such efforts.

With these contributions, this special issue provides a theory guided empirical assessment of the EU’s efforts to foster resilience in its eastern and southern neighbourhood. Through in-depth empirical research from various contexts that builds on a new conceptual framework, the volume sheds light on the promises and pitfalls of the new EU resilience paradigm. The findings of this special issue carry both academic and policy relevance. Even though this special issue underscores that resilience is a key mechanism to prevent violent conflict and governance breakdown, the EU has yet to adjust its policies towards its neighbourhoods accordingly in order to successfully help foster resilience.

Acknowledgements

This special issue results from a collaborative research endeavour entitled “Europe’s External Action and the Dual Challenges of Limited Statehood and Contested Orders” (EU-LISTCO), funded under Grant 769886 by the European Commission. EU-LISTCO entailed altogether fourteen partners in twelve countries. We are extremely grateful to all our partners for making this special issue possible through their research and valuable input. We also thank our collaborators for their critical comments during the online workshop on July 10 & 11, 2020. Felicia Riethmüller and Christine Dümler have supported this project through their terrific research assistance. We also thank Oriol Farrés for his support on graphics. Last not least, we are grateful to our anonymous reviewers as well as to the editors of Democratization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eric Stollenwerk

Eric Stollenwerk is a Research Fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies (GIGA) in Hamburg, Germany. His work lies at the intersection of international relations, comparative politics, and peace and conflict studies. His current research focuses on the legitimacy of state and non-state actors, security perceptions of local populations, and societal resilience. He has published his work among others in the Annual Review of Political Science, the Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, Terrorism and Political Violence, and Daedalus.

Tanja A. Börzel

Tanja A. Börzel is professor of political science and holds the Chair for European Integration at the Otto-Suhr-Institute for Political Science, Freie Universität Berlin. She is director of the Cluster of Excellence “Contestations of the Liberal Script”. Together with Thomas Risse, she directed the collaborative research project EULISTCO, funded by Horizon 2020. Her most recent publications include “The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism” (Oxford University Press 2016, co-edited with Thomas Risse), “Effective Governance Under Anarchy. Institutions, Legitimacy, and Social Trust in Areas of Limited Statehood,” with Thomas Risse (Cambridge University Press 2021), and “Why Noncompliance: The Politics of Law in the European Union” (Cornell University Press 2021).

Thomas Risse

Thomas Risse is professor of international politics at the Otto Suhr Institute of Political Science, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany. His most recent publications include “Challenges to the Liberal International Order” (co-editor, 75th anniversary issue of International Organization, 2021) and Effective Governance Under Anarchy. Institutions, Legitimacy, and Social Trust in Areas of Limited Statehood (Cambridge University. Press, 2021, with Tanja A. Börzel).

Notes

1 see e.g. Lake, The Statebuilder’s Dilemma; Woodward, The Ideology of Failed States; Krasner and Risse, “External Actors”.

2 see e.g. Risse et al., The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood.; Oxford Handbook of Governance; Börzel and Risse, Effective Governance Under Anarchy: Institutions, Trust, and Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.; Krasner and Risse, “External Actors.” On rebel governance see Arjona, Kasfir, and Mampilly, Rebel Governance in Civil War. On governance by “traditional” leaders see Baldwin, The Paradox of Traditional Chiefs in Democratic Africa.

3 Keim, “Building Human Resilience”; Ong et al., “Psychological Resilience”.

4 Burnell and Calvert, “The Resilience of Democracy: An Introduction”; Merkel and Lührmann, “Resilience of Democracies”.

5 See e.g. Chandler, “Resilience”; Keck and Sakdapolrak, “What is Social Resilience?”; Korosteleva, “Reclaiming Resilience Back”; Zebrowski, “The Nature of Resilience”; Merkel and Lührmann, “Resilience of Democracies”.

6 Chandler, “Resilience”. See also Merkel and Lührmann, “Resilience of Democracies”.

7 Bourbeau, “Resiliencism”; Korosteleva, “Reclaiming Resilience Back”.

8 High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, “Shared Vision, Common Action”; see also Korosteleva and Flockhart, “Resilience in EU”; Barbé and Morillas, “The EU Global Strategy”; Tocci, “EU Global Strategy”.

9 On global and diffuse risks see Magen and Richemond-Barak, “Anticipating Global and Diffuse Risks,” this special issue.

10 We see this as the main conceptual link between this special issue of Democratization and the one by Merkel and Lührmann, “Resilience of democracies.”

11 see Risse, “Governance”; Risse, Börzel, and Draude, Oxford Handbook of Governance; Börzel and Risse, Effective Governance. for details.

12 For details see Börzel and Risse, Effective Governance, ch. 2; Lee, Crippling Leviathan, ch. 1.

13 see e.g. Welzel, “Democratic Horizons”.

14 See e.g. Börzel and Risse, Effective Governance; Schmelzle and Stollenwerk, “Virtuous or Vicious Circle? for details.

15 On rebel group governance see Arjona, Kasfir, and Mampilly, Rebel Governance in Civil War; Jo, Compliant Rebels.

16 see e.g. Kakachia, Legucka, and Lebanidze, “Can the EU’s New Global Strategy Make a Difference?”, this special issue.

17 see Babayan and Risse, Democracy Promotion; Lavenex and Schimmelfennig, EU Democracy Promotion.

18 see Bargués and Morillas, “From Democratization to Fostering Resilience”, this special issue.

19 see e.g. Chandler, “Resilience”; Chandler, “Security through Societal Resilience”; Bargués-Pedreny, “Resilience is ‘Always More’”; Merkel and Lührmann, “Resilience of Democracies”.

20 Korosteleva and Flockhart; “Resilience in EU”, 158.

21 ibid., 159.

22 Chandler, “Beyond Neoliberalism”; Korosteleva, “Reclaiming Resilience Back”.

23 Magen and Richemond-Barak, “Anticipating Global and Diffuse Risks,” this special issue; see also Huber and Woertz, “Resilience, Conflict, and Areas of Limited Statehood”, this special issue.

24 Draude, Hölck, and Stolle, “Social Trust”, 354.

25 Draude, Hölck, and Stolle, “Social Trust.”

26 Anderson, Imagined Communities.

27 Foddy and Yamagishi, “Group-Based Trust”.

28 Ostrom, Governing the Commons.

29 Levi and Sacks, “Legitimating Beliefs”; Risse and Stollenwerk, “Legitimacy”.

30 Krasner and Risse, “External Actors”.

31 Schmelzle, Politische Legitimität; Schmelzle and Stollenwerk, “Virtuous or Vicious Circle?”.

32 Atack, “Four Criteria of Development”; Bratton and Chang, “State Building and Democratization”; Krasner and Risse, “External Actors”.

33 On these distinctions see Scharpf, Governing in Europe.

34 Martin, Coercive Cooperation; Zürn, Interessen und Institutionen.

35 Koremenos, Lipson, and Snidal, Rational Design.

36 Beisheim et al., “Transnational Partnerships”.

37 See e.g. Özçürümez, “The EU’s Effectiveness in the Eastern Mediterranean Migration Quandary”; Kakachia, Legucka, and Lebanidze, “Can the EU’s New Global Strategy Make a Difference?”; Bargués and Morillas, “From Democratization to Fostering Resilience”, this special issue.

38 see e.g. Magen and Barak, “Anticipating Global and Diffuse Risks”; Stollenwerk, “Preventing Governance Breakdown”; Bressan and Bergmaier, “From Conflict Early Warning to Fostering Resilience?”, this special issue.

39 Magen and Barak, “Anticipating Global and Diffuse Risks”.

40 see also Özçürümez, “The EU’s Effectiveness in the Eastern Mediterranean Migration Quandary”, this special issue; Huber and Woertz, “Resilience, Conflict, and Areas of Limited Statehood”, this special issue.

41 Bargués and Morillas, “From Democratization to Fostering Resilience”, this special issue.

42 see Stollenwerk, “Preventing Governance Breakdown”, this special issue.

43 Özçürümez, “The EU’s Effectiveness in the Eastern Mediterranean Migration Quandary”, this special issue.

44 Hegre et al., “Introduction”; Nygård et al.,“Predicting Future Challenges”.

45 Kouaouci, “Population Transitions”; Fakih, Haimoun, and Kassem, “Youth Unemployment”.

46 High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, “Shared Vision, Common Action”, 23, for a discussion see Tocci, “EU Global Strategy”.

47 European Commission, Annexes, 16.

48 Tocci, “Resilience,” 179.

49 Wagner and Anholt, “Resilience as the EU,” 415; quoted approvingly in Tocci, “Resilience,” 180.

50 see e.g. Börzel and van Hüllen, Governance Transfer; Börzel and van Hüllen, “State-Building”.

51 see e.g. Kakachia, Legucka, and Lebanidze, “Can the EU’s New Global Strategy Make a Difference?”, this special issue.

52 see e.g. Özçürümez, “The EU’s Effectiveness in the Eastern Mediterranean Migration Quandary”.

53 see e.g. Bargués and Morillas, “From Democratization to Fostering Resilience”, this special issue.

54 see Korosteleva and Flockhart “Resilience in EU”.

55 on the need for a strategy see also Brozus, Jetzlsperger, and Walter-Drop, “Policy”.

56 Bargués and Morillas, “From Democratization to Fostering Resilience”, this special issue.

57 Kakachia, Legucka, and Lebanidze, “Can the EU’s New Global Strategy Make a Difference?”, this special issue.

58 Börzel and Risse, “Venus Approaching Mars?”.

59 Rothstein and Stolle, “Political Institutions”; Rothstein and Stolle, “The State and Social”.

60 Bargués and Morillas, “From Democratization to Fostering Resilience”, this special issue.

61 see Bressan and Bergmaier “From Conflict Early Warning to Fostering Resilience?”, this special issue.

62 see Stollenwerk “Preventing Governance Breakdown”, this special issue.

63 Nicole Koenig, “The EU”; Nils Koenig, “Between Conflict Management”; Lefèvre, “The Pitfalls”.

64 See Kakachia, Legucka, and Lebanidze, “Can the EU’s New Global Strategy Make a Difference?”; Bargués and Morillas “From Democratization to Fostering Resilience”; Stollenwerk, “Preventing Governance Breakdown”, this special issue; see also Davis, “Reform or Business”; Mouhib, “EU Democracy Promotion”; Noutcheva, “Whose Legitimacy?”; Lavrelashvili, “Resilience-Building”.

References

- Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities. Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. 2nd ed. London: Verso, 1991.

- Arjona, Ana, Nelson Kasfir, and Zachariah Mampilly, eds. Rebel Governance in Civil War. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Atack, Iain. “Four Criteria of Development NGO Legitimacy.” World Development 27, no. 5 (1999): 855–864. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00033-9.

- Babayan, Nelli, and Thomas Risse, eds. Democracy Promotion and the Challenges of Illiberal Regional Powers. Special Issue of ‘Democratization’. Abingdon: Routledge, 2016.

- Baldwin, Kate. The Paradox of Traditional Chiefs in Democratic Africa. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Barbé, Esther, and Pol Morillas. “The EU Global Strategy: The Dynamics of a More Politicized and Politically Integrated Foreign Policy.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 32, no. 6 (2019): 753–770. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09557571.2019.1588227.

- Bargués, Pol, and Pol Morillas. “From Democratization to Fostering Resilience: EU Intervention and the Challenges of Building Institutions, Social Trust and Legitimacy in Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Democratization (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1900120.

- Bargués-Pedreny, Pol. “Resilience is “Always More” than our Practices: Limits, Critiques, and Skepticism About International Intervention.” Contemporary Security Policy 41, no. 2 (2020): 263–286. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1678856.

- Beisheim, Marianne, Andrea Liese, Hannah Janetschek, and Johanna Sarre. “Transnational Partnerships: Conditions for Successful Service Provision in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Governance 27, no. 4 (2014): 655–673. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12070.

- Boiten, Valérie J. “The Semantics of “Civil”: The EU, Civil Society and the Building of Democracy in Tunisia.” European Foreign Affairs Review 20, no. 3 (2015): 357–378. https://heinonline.org/HOL/NotSubscribed?collection=0&bad_coll=kluwer&send=1.

- Börzel, Tanja A., and Thomas Risse. “Venus Approaching Mars? The European Union’s Approaches to Democracy Promotion in Comparative Perspective.” In Promoting Democracy and the Rule of Law. American and European Strategies, edited by Amichai Magen, Thomas Risse, and Michael McFaul, 34–60. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- Börzel, Tanja A., and Thomas Risse. “Dysfunctional State Institutions, Trust, and Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Regulation & Governance 10, no. 2 (2016): 149–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12100.

- Börzel, Tanja A., and Thomas Risse. Effective Governance Under Anarchy. Institutions, Legitimacy, and Social Trust in Areas of Limited Statehood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Börzel, Tanja A., Thomas Risse, and Anke Draude. “Conceptual Clarifications and Major Contributions of the Handbook.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, Tanja A. Börzel, and A. Draude, 3–28. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Börzel, Tanja A., and Vera van Hüllen. “State-Building and the European Union’s Fight Against Corruption in the Southern Caucasus: Why Legitimacy Matters.” Governance 27, no. 4 (2014): 613–634. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12068.

- Börzel, Tanja A., and Vera van Hüllen, eds. Governance Transfer by Regional Organizations. Patching Together a Global Script. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Bourbeau, Philippe. “Resiliencism: Premises and Promises in Securitisation Research.” Resilience 1, no. 1 (2013): 3–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21693293.2013.765738.

- Bratton, Michael, and Eric C.C. Chang. “State Building and Democratization in Sub-Saharan Africa Forwards, Backwards, or Together?” Comparative Political Studies 39, no. 9 (2006): 1059–1083. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414005280853.

- Bressan, Sarah, and Aurora Bergmaier. “From Conflict Early Warning to Fostering Resilience? Chasing Convergence in EU Foreign Policy.” Democratization (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1918108.

- Brozus, Lars, Christian Jetzlsperger, and Gregor Walter-Drop. “Policy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, Tanja A. Börzel, and Anke Draude, 584–603. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Burnell, Peter, and Peter Calvert. “The Resilience of Democracy: An Introduction.” Democratization 6, no. 1 (1999): 1–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510349908403594.

- Chandler, D. “Beyond Neoliberalism: Resilience, the new art of Governing Complexity.” Resilience 2, no. 1 (2014): 47–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21693293.2013.878544.

- Chandler, David. “Resilience.” In Routledge Handbook of Security Studies, edited by Myriam D. Cavelty, and Thierry Balzacq, 436–446. Abingdon and New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Chandler, David. “Security Through Societal Resilience: Contemporary Challenges in the Anthropocene.” Contemporary Security Policy 41, no. 2 (2020): 195–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1659574.

- Davis, Laura. “Reform or Business as Usual? EU Security Provision in Complex Contexts: Mali.” Global Society 29, no. 1 (2015): 260–279. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2015.1034092.

- Draude, Anke, Lasse Hölck, and Dietlind Stolle. “Social Trust.” In The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, Tanja A. Börzel, and Anke Draude, 353–372. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Easton, David. The Poltical System. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1953.

- European Commission. Annexes to the Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council Establishing the Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument. Brussels: European Commission, 2018.

- Fakih, Ali, Nathir Haimoun, and Mohamad Kassem. “Youth Unemployment, Gender and Institutions During Transition: Evidence from the Arab Spring.” Social Indicators Research 150 (2020): 311–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-020-02300-3.

- Fisk, Kylia, and Adrian Cherney. “Pathways to Institutional Legitimacy in Postconflict Societies: Perceptions of Process and Performance in Nepal.” Governance 30, no. 2 (2017): 263–281. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12208.

- Foddy, Margaret, and Toshio Yamagishi. “Group-Based Trust.” In Whom Can We Trust? How Groups, Networks, And Institutions Make Trust Possible, edited by Karen S. Cook, Margaret Levi, and Russel Hardin, 17–41. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2009.

- Hegre, Håvard, Nils W. Metternich, Håvard Mokleiv Nygård, and Julian Wucherpfennig. “Introduction.” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 2 (2017): 113–124.

- High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy. Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe. A Global Strategy for the European Union’s Foreign and Security Policy. Brussels: European Union, 2016.

- Huber, Daniela, and Eckart Woertz. “Resilience, Conflict and Areas of Limited Statehood in Iraq, Lebanon and Syria.” Democratization (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1940967.

- Jo, Hyeran. Compliant Rebels. Rebel Groups and International Law in World Politics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Kakachia, Kornely, Agnieszka Legucka, and Bidzina Lebanidze. “Can the EU’s new Global Strategy Make a Difference? Strengthening Resilience in the Eastern Partnership Countries.” Democratization (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1918110.

- Keck, Markus, and Patrick Sakdapolrak. “What Is Social Resilience? Lessons Learned and Ways Forward.” Erdkunde 67, no. 1 (2013): 5–19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23595352.

- Keim, Mark E. “Building Human Resilience: The Role of Public Health Preparedness and Response As an Adaptation to Climate Change.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35, no. 5 (2008): 508–516. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.08.022.

- Keohane, Robert O. “Neoliberal Institutionalism. A Perspective on World Politics.” In International Institutions and State Power. Essays in International Relations Theory, edited by Robert O. Keohane, 35–73. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1989.

- Koenig, Nicole. “The EU and the Libyan Crisis – In Quest of Coherence?” The International Spectator 46, no. 4 (2011): 11–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2011.628089.

- Koenig, Nicole. “Between Conflict Management and Role Conflict: the EU in the Libyan Crisis.” European Security 23, no. 3 (2014): 250–269. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2013.875532.

- Koremenos, Barbara, Charles Lipson, and Duncan Snidal, eds. Rational Design: Explaining the Form of International Institutions. Special Issue of International Organization. Vol. 55. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Korosteleva, Elena A. “Reclaiming Resilience Back: A Local Turn in EU External Governance.” Contemporary Security Policy 41, no. 2 (2020): 241–262. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1685316.

- Korosteleva, Elena A., and Trine Flockhart. “Resilience in EU and International Institutions. Special Issue.” Contemporary Security Policy 41, no. 2 (2020). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2020.1723973.

- Korosteleva, Elena A., and Trine Flockhart. “Resilience in EU and International Institutions: Redefining Local Ownership in a new Global Governance Agenda.” Contemporary Security Policy 41, no. 2 (2020): 153–175. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2020.1723973.

- Kouaouci, Ali. “Population Transitions, Youth Unemployment, Postponement of Marriage and Violence in Algeria.” The Journal of North African Studies 9, no. 2 (2004): 28–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1362938042000323329.

- Krasner, Stephen D., and Thomas Risse. “External Actors, State-Building, and Service Provision in Areas of Limited Statehood: Introduction.” Governance 27, no. 4 (2014): 545–567. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12065.

- Lake, David A. The Statebuilder's Dilemma. On the Limits of Foreign Intervention. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016.

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Frank Schimmelfennig, eds. EU Democracy Promotion in the Neighbourhood: From Leverage to Governance? Special Issue of 'Democratization'. London: Routledge, 2011.

- Lavrelashvili, Teona. “Resilience-Building in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine: Towards a Tailored Regional Approach from the EU.” European View 17, no. 2 (2018): 189–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1781685818805680.

- Lee, Melissa M. Crippling Leviathan. How Foreign Subversion Weakens the State. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2020.

- Lefèvre, Raphael. “The Pitfalls of Russia’s Growing Influence in Libya.” The Journal of North African Studies 22, no. 3 (2017): 329–334. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2017.1307840.

- Levi, Margaret, and Audrey Sacks. “Legitimating Beliefs: Sources and Indicators.” Regulation & Governance 3, no. 4 (2009): 311–333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5991.2009.01066.x.

- Magen, Amichai, and Daphné Richemond-Barak. “Anticipating global and diffuse risks to prevent conflict and governance breakdown: lessons from the EU's southern neighbourhood.” Democratization (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1940968.

- Martin, Lisa L. Coercive Cooperation: Explaining Multilateral Economic Sanctions. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992.

- Merkel, Wolfgang, and Anna Lührmann. “Resilience of Democracies: Responses to Illiberal and Authoritarian Challenges.” Democratization 28, no. 5 (2021): 869–884. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1928081.

- Müller, Martin. “Public Opinion Toward the European Union in Georgia.” Post-Soviet Affairs 27, no. 1 (2011): 64–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.2747/1060-586X.27.1.64.

- Noutcheva, Gergana. “Whose Legitimacy? The EU and Russia in Contest for the Eastern Neighbourhood.” Democratization 25, no. 2 (2018): 312–330. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2017.1363186.

- Nygård, Håvard Mokleiv, Siri Aas Rustad, Eric Stollenwerk, and Andreas F. Tollefsen. “Predicting Future Challenges: Quantitative Risk Assessment Tools for the EU's Eastern and Southern Neighbourhoods.” EU-LISTCO Working Paper Series, No. 3 (2019): 1–61.

- Ong, Anthony D., C. S. Bergeman, Tony L. Bisconti, and Kimberly A. Wallace. “Psychological Resilience, Positive Emotions, and Successful Adaptation to Stress in Later Life.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 91, no. 4 (2006): 730–749. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730.

- Ostrom, Elinor. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Özçürümez, Saime. “The EU's Effectiveness in the Eastern Mediterranean Migration Quandary: Challenges to Building Societal Resilience.” Democratization (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1918109.

- Risse, Thomas. “Governance in Areas of Limited Statehood. Introduction and Overview.” In Governance Without a State? Policies and Politics in Areas of Limited Statehood, edited by Thomas Risse, 1–35. New York: Columbia University Press, 2011.

- Risse, Thomas, Tanja A. Börzel, and Anke Draude, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Governance and Limited Statehood. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Risse, Thomas, and Eric Stollenwerk. “Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Annual Review of Political Science 21, no. 1 (2018): 403–418. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041916-023610.

- Rothstein, Bo, and Dietlind Stolle. “Political Institutions and Generalized Trust.” In The Handbook of Social Capital, edited by Dario Castiglione, Jan W. Van Deth, and Guglielmo Wolleb, 273–302. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Rothstein, Bo, and Dietlind Stolle. “The State and Social Capital: An Institutional Theory of Generalized Trust.” Comparative Politics 40, no. 4 (2008): 441–459. doi:https://doi.org/10.5129/001041508X12911362383354.

- Scharpf, Fritz W. Governing in Europe. Effective and Democratic? Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Schmelzle, Cord. Politische Legitimität und zerfallene Staatlichkeit. Vol. 80. Frankfurt/New York: Campus, 2015.

- Schmelzle, Cord, and Eric Stollenwerk. “Virtuous or Vicious Circle? Governance Effectiveness and Legitimacy in Areas of Limited Statehood.” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 12, no. 4 (2018): 449–467. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2018.1531649.

- Schmidt, Vivien A. “Democracy and Legitimacy in the European Union Revisited: Input, Output and ‘Throughput’.” Political Studies 61, no. 1 (2013): 2–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00962.x.

- Stollenwerk, Eric. “Preventing Governance Breakdown in the EU’s Southern Neighborhood: Fostering Resilience to Strengthen Security Perceptions.” Democratization (2021). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1928079.

- Tocci, Nathalie. “The Making of the EU Global Strategy.” Contemporary Security Policy 37, no. 3 (2016): 461–472. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2016.1232559.

- Tocci, Nathalie. “Resilience and the Role of the European Union in the World.” Contemporary Security Policy 41, no. 2 (2020): 176–194. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2019.1640342.

- Tyler, Tom R. Why People Obey the Law. New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1990.

- Wagner, Wolfgang, and Rosanne Anholt. “Resilience as the EU Global Strategy’s New Leitmotif: Pragmatic, Problematic or Promising?” Contemporary Security Policy 37, no. 3 (2016): 414–430. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2016.1228034.

- Weber, Max. Economy and Society. Berkeley–Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1978 (1922).

- Welzel, Christian. “Democratic Horizons: What Value Change Reveals About the Future of Democracy.” Democratization 28, no. 5 (2021): 992–1016. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2021.1883001.

- Woodward, Susan L. The Ideology of Failed States. Why Intervention Fails. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Zebrowski, Chris. “The Nature of Resilience.” Resilience 1, no. 3 (2013): 159–173.

- Zürn, Michael. Interessen und Institutionen in der internationalen Politik. Grundlegung und Anwendung des situationsstrukturellen Ansatzes. Opladen: Leske & Budrich, 1992.