ABSTRACT

How do we theorize the unexpected global trend of democratic regression? Building upon recent literature on backsliding, we offer a new conceptualization of the notion of democratic authoritarianism, denoting the use of democratic-looking institutions for the expansion of authoritarian forms of power across different regime types, democratic and authoritarian. Whereas existing accounts of autocratization focus overwhelmingly on the executive, we outline democratic authoritarianism as a broader process involving mechanisms of institutional and ideational capture, which may be initiated and implemented by executives, legislatures, judiciaries as well as non-state organizations, often acting in tandem. Our notion of democratic authoritarianism can explain autocratization in states with both strong and weak elected executives; it recognizes the role of anti-pluralist ideologies and civil society organizations in enabling autocratization. We illustrate our argument through a comparative analysis of contemporary South Asia, which we argue illustrates different variants of democratic authoritarianism. Through detailed case studies of India and Pakistan since 2014, we show that South Asia is significant for understandings of autocratization, notably, the range of instruments deployed and the different stages of democratic authoritarianism, the interplay between state and societal institutions, and the limits of commonly suggested remedies, notably empowering the judiciary and civil society.

Introduction

The rise of authoritarian leaders in ostensibly democratic countries across the world has generated a rich emerging scholarship on the subject. A wide range of concepts has been proposed to understand and explain different aspects of the unexpected global trend of democratic decline – competitive authoritarianism, democratic backsliding, constitutional retrogression, autocratization, to name a few.Footnote1 We welcome its recognition that democracy and authoritarianism should not be treated as mutually exclusive categories, and argue that recent scholarship on backsliding marks an advance over older democratization debates in important respects.Footnote2 However, whereas the scholarship on democratic regression has focused overwhelmingly on populist leaders and executive over-reach, we argue that a broader analytical framework is necessary to grasp the institutional and ideational dimensions of autocratization that include but extend beyond the actions of elected executives.

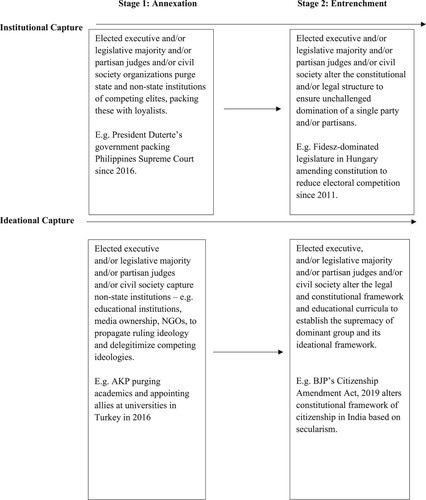

In this article, we reconceptualize the notion of democratic authoritarianism to offer such a framework, a phenomenon that transcends democratic and authoritarian regimes.Footnote3 In our account, democratic authoritarianism connotes the mobilization of multiple democratic-looking institutions across state and civil society, including elections, constitutional courts, and private media, to expand authoritarian forms of power in a polity. We outline two inter-related processes that characterize this contemporary global phenomenon: institutional capture, or the removal of political opposition from positions of power in key institutions, and ideational capture, or the exclusion and delegitimization of competing or opposing ideological frameworks. The goal is not simply domination but hegemony or monopolistic control of the political system, through creating the appearance of popular consent for the undivided supremacy of a leader or party. In a simplified form, democratic authoritarianism unfolds in two stages, annexation, or monopolistic control of the political system, and entrenchment, in which a new political and normative framework is instituted in the polity that enshrines the ideological vision and reinforces the political dominance of the hegemon.

We derive our analytical framework from, and demonstrate its utility for, South Asia, home to a fourth of the world’s population, which has witnessed democratic reversals in all major countries in recent years. South Asia offers examples of different variants of democratic authoritarianism today, with hegemonic control exercised through one-party hegemony in India and Bangladesh, and civilian–military hybrid regimes in Pakistan and Sri Lanka. We seek to contribute to the valuable scholarship on backsliding as follows.Footnote4 First, whereas the literature offers mostly executive-centred accounts, our account of democratic authoritarianism encompasses autocratizing practices and strategies across multiple state institutions – executive, legislature, the judiciary – as well as sections of civil society, including the media, socio-religious organizations, and street mobs. Second, our notion of democratic authoritarianism highlights the central role of democratic-looking ideologies in legitimizing authoritarian power. Elections, court decisions and street mobilizations also augment and secure the power of autocratizing actors by offering democratic legitimation.Footnote5 While most contemporary scholarship focusses on right-wing ethno-nationalism,Footnote6 we contend this is a common but not a necessary feature of autocratization, which can be supported by anti-pluralist ideologies that are not always exclusionary ethno-nationalist in content. Finally, whereas scholars of backsliding have focussed on nominally democratic regimes, and of electoral authoritarianism, on authoritarian regimes, our notion of democratic authoritarianism transcends different regime types, separating itself in a more thorough-going fashion from the influential categorical distinction between democratic and authoritarian regimes.

In this article, we first discuss the literature on the use of democratic institutions by authoritarian regimes, and backsliding in consolidated democracies, to argue for a unifying framework for studying processes of autocratization across regime types. We then elaborate our notion of democratic authoritarianism in terms of inter-related processes of institutional and ideational capture across state and civil society. In the following section, we focus on South Asia and provide a brief comparison of India and Pakistan since 2014 to demonstrate the multiple mechanisms and pathways to democratic authoritarianism. We argue that, notwithstanding their distinct historical trajectories, regime types, and ideological dispositions, both states have witnessed fundamentally similar processes of autocratization in the last decade, and resemble cases of democratic backsliding across the world, while highlighting certain lesser-known features of this global phenomenon. In the conclusion, we outline some wider implications of our argument, as well as its limits, for South Asia and beyond.

Democratic authoritarianism

Two puzzles have recently attracted considerable attention among scholars of comparative politics. First, why do authoritarian regimes adopt institutions conventionally associated with democracy? Second, why are erstwhile consolidated democratic regimes experiencing democratic backsliding? Although scholarship on these questions has tended to proceed on separate tracks, we argue that these puzzles are inter-related. Scholarship on authoritarianism has shown how elections, judiciaries and legislatures, instead of fostering democratization, can serve to consolidate and stabilize authoritarian regimes, providing tools for sustained domination over society. However, these democratic-looking institutions can serve as instruments of domination in consolidated democracies as well, a fact overlooked until recently by political scientists.

Recent scholarship has made valuable progress, recognizing that democracy and authoritarianism are not mutually exclusive categories. Scholars have argued that hybrid regimes that combine “democratic rules with authoritarian governance” are not transitional regimes but a distinct form in their own right.Footnote7 Scholarship on autocratization marks an important advance over the older democratization literature, going beyond its binary democratic-authoritarian distinction and associated teleology of inevitable progression toward democratization over time. It has shown how established democracies can become less democratic over time as a result of the accretion of authoritarian features, a process that is often incremental and gradual, occurring below the radar, which makes it harder to recognize and to oppose, in contrast to spectacular modes of democratic breakdown such as coups.Footnote8 However, scholarship is still catching-up with ground-level realities of democratic regression, and struggles to explain its speed in many cases, as discussed below.

We argue that explaining the current democratic recession poses an analytical challenge for at least two reasons. First, notwithstanding recent advances, the influential categorical distinction between democratic and authoritarian regimes in political science continues to exercise a residual hold on political science scholarship. The associated apriori assumption that democratic institutions necessarily play a democracy-enabling role in countries classified as democratic, and an authoritarian-enabling role in countries classified as authoritarian, has for long forestalled empirical inquiry into how similar institutions may be used for similar purposes across democratic and authoritarian regimes. Scholars of comparative authoritarianism, for instance, have argued that the intentions and functions of elections, constitutions and courts in authoritarian regimes and democracies differ fundamentally.Footnote9 Yet many of the ways in which elections, courts and constitutions are used to shore up the power of dictatorial regimes – co-opting rivals, dividing and weakening the opposition, bolstering regime legitimacy and cohesion – can also be observed in instances of democratic decline.Footnote10 Similarly, while scholars of authoritarianism have drawn attention to how the core tasks of a state, such as tax collection, policing and welfare, are “the ultimate institutional weapons in the authoritarian arsenal,”Footnote11 how the coercive apparatus of the state can be deployed for the expansion of authoritarianism also in consolidated democracies, remains under-explored by political scientists.Footnote12

Second, the valuable scholarship on autocratization has tended to focus on particular state institutions, notably the executive, to the neglect of others, such as the judiciary and civil society actors such as religious organizations and vigilante groups, which we argue also play a key role in the expansion of authoritarianism. Scholars have rightly noted the similarities in the techniques used by leaders in Hungary, Poland, India, and the US on the one hand, and those in Russia, Malaysia and Cambodia, on the other.Footnote13 Across these diverse democratic and authoritarian regimes, autocratization takes place through a similar process, the dismantling of checks to executive power, undertaken mostly through channels that are, or appear to be, democratic and/or constitutional or legal. Focussing on executive aggrandizement, scholars have shown how elected executives neutralize potential checks to their power posed by courts, elections commissions, parliaments, media and civil society organizations, to evade accountability, and instead use these institutions to further expand their power.Footnote14

Yet, focussing solely on elected executivesFootnote15 leaves us unable to adequately explain autocratization in states where elected executives are weak, constrained by other state institutions, such as the judiciary and military. For instance, recent decisions by courts in Brazil and Pakistan demonstrate how judges expand their constitutional role in order to oust elected executives, with critical consequences for autocratization. In Paraguay, the opposition-controlled parliament used its constitutional powers of impeachment to destabilize and finally remove President Lugo from power in 2012. Indeed, the relatively swift pace of autocratization in relatively consolidated democracies is hard to explain with reference to a single institution and begs more questions – why, and how, have authoritarian actors managed to capture multiple institutions with relative ease in some countries, and not in others?Footnote16

Thus, while building upon the important literature on backsliding, we also depart from it in key respects. First, we argue that while executive aggrandizement is undoubtedly a key driver, autocratization can also be the consequence of actions initiated by actors other than elected executives. Aspiring authoritarians can emerge from a range of state and non-state institutions, there can be more pathways to democratic regression than those suggested by a focus on executive aggrandizement. Second, whereas scholarship on backsliding has focussed mostly on institutional processes, and the scholarship on populism has focussed on ideological frames, we argue for a unifying framework that combines institutional and ideational dimensions of autocratization. Populism scholarship has insightfully delineated the contours of populist ideologiesFootnote17; however, these have been usually examined in the context of particular leaders (e.g. Trump, Erdogan, Modi) and/or institutions (e.g. political parties). We need a framework that can explain how populist ideologies are propagated by multiple institutions across state and society to facilitate autocratization. Third, terms such as “executive aggrandizement” and “autocratic legalism” obscure the fact that contemporary autocratization is facilitated by legitimizing ideologies which are democratic in form if not content, invoking the majority, the masses, the people, against elites.Footnote18 The distinguishing feature of these ideologies is not so much their ethno-nationalism although this is a common feature in most contemporary instances, as their appeal to democratic values of political equality and popular rule, in ways that are anti-pluralist.

We, therefore, propose a broader conceptual framework for understanding the dynamics of autocratization, across different regime types. In political science, the term democratic authoritarianism has been used to describe the deployment of nominally democratic institutions to consolidate authoritarian regimes.Footnote19 We lift this concept out of the context of authoritarian regimes and argue that such processes of buttressing authoritarian power can play out in so-called democratic regimes as well. Democratic authoritarianism as a phenomenon that transcends regime types is familiar to scholars of South Asia, who have long used the term to describe the coexistence of democratic and authoritarian elements in political systems.Footnote20 Building upon their pioneering scholarship, we develop the concept further, to denote the deployment of democratic-looking institutions such as elections, legislatures and judiciaries, for the expansion of authoritarian forms of power across different regime-types. “Democratic authoritarianism” in our account is not simply an interweaving of democratic and autocratic processes, a mixture of the two with open outcomes, but denotes the deployment of democratic-looking institutions and ideologies for purposes that are fundamentally authoritarian. “Democratic-looking” here denotes that these institutions and ideologies are democratic in form, if not in content, mobilizing electoral majorities and numbers on streets, deploying the rhetoric of popular sovereignty, mobilizing legality through constitutional amendments and judicial decisions.Footnote21 “Authoritarianism” denotes that the ends to which these democratic-looking instruments are deployed by a leader and/or party, are domination without accountability. Coming to grips with the complex dynamics and multiple trajectories of democratic authoritarianism requires us to (i) examine the role of multiple democratic-looking institutions, including constitutional courts, elected legislatures, as well as the executive, and their inter-relationships; (ii) consider the role of state and non-state institutional actors, including mobilized civil society; (iii) examine the role of democratic-looking ideological legitimation for advancing authoritarian outcomes.

Mechanisms of institutional and ideational capture

Democratic authoritarianism involves systemic control extending across multiple state institutions as well as civil society, exercised through ideational as well as institutional capture, what scholars have termed hegemony.Footnote22 The goals here extend beyond political domination, to monopolistic control of state and civil society institutions, not just to aggrandize power, but to establish the political, ideological, and social dominance of a ruling party or elite.Footnote23 Institutional and ideational capture can be pursued by actors not just from the executive, but also the legislature, the judiciary, and civil society organizations, deploying a wide range of instruments available to these institutions.

Institutional capture: A party or segment of political elites seeks to capture political institutions such as the executive, legislature and judiciary, and purge competing parties and rival elites from positions of power and influence. The goal here is not simply to remove limits on executive power, but also to empower other state institutions after these are packed with supporters and purged of critics.

Ideational Capture: Authoritarian elites annex the opinion-making bodies that Althusser famously termed the “ideological state apparatus,” including educational institutions (universities, school curricula), print, electronic and social media, to propagate their ideology. The process of ideational capture involves using democratic-looking institutions, as well as the ideational legitimacy they bestow, to establish the monopoly of the authoritarian’s ideology, delegitimizing competing and opposing ideological frameworks. The goal is to transform the identity of the state in ways that implement the ideological vision of the ruling party, as well as ensure its continued political control.

How then do ostensibly democratic institutions and ideologies facilitate institutional and ideational capture?

First, in addition to emergency state powers, which are also constitutional and legal, several routine powers vested in elected and constitutional state branches can be deployed by different institutional actors for institutional and ideological capture. Legislators and judges can also act on their own initiative, even if less so than the executive, to facilitate the appointment and empowerment of like-minded elites, the removal of oppositional elites, and the propagation of their ideational frameworks.

An elected executive can (i) use appointment powers to legally pack oversight institutions (e.g. constitutional courts, election commissions) with loyalists and purge them of critics (e.g. in Hungary); (ii) define and change the rules which give effect to laws, including legal exceptions, public order, health and related restrictions on constitutional rights and liberties (e.g. during the COVID-19 pandemic); (iii) selectively deploy the military, police, bureaucracy, intelligence and investigative agencies to punish and silence opposition leaders (e.g. Turkey, India); and (iv) use advertising revenues to fund supporters in the media and silence critics.

A legislative majority, with or without an elected executive, can (i) combine majority decision-making with party discipline and the use of whips to augment executive power by slamming laws through legislatures, circumventing scrutiny; deny institutional recognition and positions to opposition parties, impeach and dismiss officials within other branches (e.g. Paraguay in 2012); (ii) impose draconian restrictions on civil and political liberties and criminalize dissent, (iii) allow aspiring authoritarians to amend the constitution to translate their political vision into law; and (iv) alter the regulatory framework for private associations in ways which advantage the ruling party, and diminish the organizational capacity of opponents.

An assertive judiciary can interpret the constitution, laws, and its prerogatives in ways that further an authoritarian agenda. Judges can overrule state appointments and disqualify elected leaders from political office, convicting them for fraud or civil offences. Judges can also use their pulpits to delegitimize dissenters and elected executives (e.g. Brazil in 2016).Footnote24

Second, the deployment of democratic-looking ideologies has also facilitated autocratization. Historically, a dominant ideology was seen as a defining feature of revolutionary and totalitarian regimes, providing the leader with a source of legitimacy, and mobilizing public support for the regime’s goals.Footnote25 In democratic authoritarianism, not only do leaders and parties achieve political dominance through ostensibly working democratic institutions such as elections, they also appeal to democratic values such as political equality and popular rule. An extensive scholarship has examined the populist ideologies deployed by today’s elected autocrats, which pit a simple, virtuous “people” against a self-interested corrupt elite who control the levers of power.Footnote26 Populism is often associated with right-wing ethno-nationalism in contemporary cases, and analysts have therefore tended to focus on the autocratizing resources of ethno-nationalist ideologies. But populist ideologies can facilitate autocratization independently of right-wing ethno-nationalism, as these posit a direct, unmediated relationship between the people on the one hand, and the (elected) leader and/or ruling parties, on the other. Elected leaders and parties can portray themselves as the sole embodiment of the popular will, laying claim to the absolute power associated with popular sovereignty, unshackled from the chains of countervailing institutions (e.g. legislatures, judiciaries, election commissions), which can be delegitimized as elitist, undemocratic and corrupt.Footnote27 Democratic-authoritarian ideologies can range across the Left–Right spectrum as long as they are anti-pluralist, denying space for competing actors and values in the public sphere.Footnote28 For instance, in India in the 1970s, autocratization was enabled by the ostensibly left-wing populism of Indira Gandhi.

Third, whereas scholarship on backsliding has focussed mainly on state institutions, non-state actors such as socio-religious organizations and the media can also advance autocratization in ways that appear democratic. Civil society is of course diverse and multi-valent; several civil society organizations do play a crucial democracy-enhancing role, demanding “diagonal accountability” from the executive.Footnote29 Nevertheless, allies of the ruling party in civil society can also act as key partners in autocratization, not only in a subsidiary role as these are captured by political elites, but also as initiators of autocratization in their own right, with ruling parties sometimes as their dependent partners. A reckoning of the autocratizing partnerships that can exist between state and civil state actors is necessary to explain the swift pace of democratic backsliding witnessed in some countries. For instance, India’s rapid democratic decline since 2014 is hard to explain solely in terms of Modi and the BJP, without also taking into account the long-standing work, material and ideational, of grass-roots socio-religious organizations of the Hindu nationalist family (Sangh parivar), with the Rasthriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) as its nucleus.Footnote30 Non-state organizations can act as partners of autocratizing state actors in a range of roles – as advisors with veto powers; mobilizers for political parties at election time; missionaries and recruiters for its cause; service providers of social goods (e.g. education and activity clubs), and of violence (e.g. vigilante outfits performing harassment, beatings, and lynchings of opponents of the government, with tacit or active support of police, army, judiciary). While vigilantism seeks to “challenge, usurp or displace the state’s authority,”Footnote31 vigilante outfits often act in partnership with state actors who offer financial support and impunity,Footnote32 deriving legitimacy as an expression of popular sentiment, enforcing the will of a social majority and thereby as democratic to an extent.Footnote33 Street mobilizations of sections of civil society can make the purging of oppositional elites and the repression of competing ideologies seem a response to popular demands and hence as “democratic” (e.g. protests in Thailand in 2013 to demand a replacement of the system of elected representatives).Footnote34

The twin processes of institutional and ideational capture tend to unfold in two stages,Footnote35 which we illustrate in . In the first stage that we term annexation, autocratizing actors acquire power typically by winning an election, and/or legally removing rival elites from positions of power in the political system (e.g. through disqualification of elected leaders). Once positions of state power are captured, co-optation and coercion are used to establish their political hegemony and demobilize resistance. Simultaneously, ideational institutions, notably in education and the academy, print, electronic and social media, are captured and sought to be remade into instruments of propaganda and proselytization.

In the second stage that we term entrenchment, authoritarian elites seek to transform the existing democratic state structure, for instance changing the constitution to reorganize the division of power between institutions or levels of the polity, and/or alter the framework of citizenship in ways that reflect their ideological vision and secure their political rule. Under democratic authoritarianism, competing elites are forced to accept being subsidiary allies or loyal opponents, with opposition, dissent or even with-holding assent rendered very costly, or illegal, crushed by state agencies, often acting in tandem with affiliate civil society groups. With political competition and participation radically reduced in scope, democratic decay becomes endemic, and self-reinforcing.

Democratic authoritarianism in South Asia

In this section, we probe the utility of our framework for understanding autocratization in South Asia over the last decade. Since decolonization in the mid-twentieth century, South Asia has had a mixed history of democracy. India and Sri Lanka have remained electoral democracies for the most part with strong ethnic majoritarian elements, whereas Pakistan and Bangladesh have fluctuated between periods of direct military rule and unstable civilian rule. However, in the last decade, all four countries, with their very distinct histories and institutional arrangements, have seen remarkably similar processes of autocratization unfolding. In each country, authoritarian elites have used a range of executive, legislative and judicial powers and affiliate groups in civil society to remove and weaken competing elites and critics, using state power to propagate the ideology of the ruling party, substantially reducing the scope of political competition and participation. Furthermore, domination has been legitimized as democratic through electoral victories and mobilizations of mass support and demonstrations of strength on the street. These similarities in the instruments deployed by authoritarian leaders, summarized in , co-exist with different trajectories to, and forms of democratic authoritarianism outlined in , making South Asia a key region for a comparative study of the phenomenon.

Table 1. Similarities in mechanisms of institutional and ideational capture across South Asia.

Table 2. Democratic authoritarian formations in South Asia since 2010.

In order to provide a deeper analysis of mechanisms of democratic authoritarianism, we provide case studies of India and Pakistan below. These illustrate how fundamentally similar processes can involve different actors (elected executive, judiciary, military) and distinct ideologies (ethno-religious nationalism, militarized nationalism) across distinct regime types.

India since 2014: from electoral democracy to electoral autocracy?

Hailed until recently as the world’s largest democracy, India in the period of Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) rule has been demoted from electoral democracy to electoral autocracy in international rankings, with the decline in its level of liberal democracy one of “the most dramatic shifts” across the world over the last decade.Footnote36 Democratic authoritarianism in India is not entirely new, nor is it limited to a particular party. The era of electoral dominance by the Congress party (1947–1989) was also punctuated by the deployment of colonial era authoritarian laws.Footnote37 Nevertheless, there is a growing consensus that the period since the 2014 election has witnessed a step change, with rising levels of authoritarianism on multiple indicators.Footnote38

Institutional and ideational capture by the BJP is well-documented and follows a pattern familiar to scholars of backsliding in other countries. In the first annexation stage (roughly 2014–2019), following a watershed election powered by Modi’s charismatic leadership, the BJP formed the first single party majority government in India in thirty years (based on 31% of the popular vote). The BJP government proceeded to use its executive powers and legislative majority in the lower house (Lok Sabha) to eliminate rivals and critics from positions of power through questionable, albeit mostly legal mechanisms. Initially, this involved contravening existing democratic conventions, notably regarding partisanship, with BJP leaders installed in key state offices (including President and Vice President), with Opposition offices (e.g. the Leader of the parliamentary opposition), deliberately kept vacant. The BJP government used its legislative majority to ram controversial laws through Parliament without referral to committees as per convention, including, notably, an electoral bonds scheme that, under the guise of election finance reform, enabled unlimited anonymous corporate donations to political parties (the BJP has received around 75%).Footnote39 Judicial oversight was weakened as against convention, the Modi government repeatedly refused to confirm the recommendations of the Supreme Court collegium for appointments of judges who have given decisions adverse to the BJP leadership.Footnote40 Institutional capture was also achieved by expanding the role of the executive in appointments to other oversight institutions, notably the Election Commission, Information Commissions, the Reserve Bank of India, leaving many deliberately understaffed, undermining their capacity to hold the government accountable.Footnote41

The annexation phase also involved the capture of ideational institutions in civil society, including the press and academic institutions, using instruments of coercion familiar from the authoritarian arsenal. Prestigious public universities and research bodies were brought under government control by foisting leadership affiliated with Hindu right organizations that often lacked academic qualifications, in the teeth of opposition from students and academics.Footnote42 Private media houses were brought in line with the use of incentives such as advertising revenues, government information, as well as threats, such as deploying state investigative and intelligence agencies (notably the Central Bureau of Investigation, the Enforcement Directorate, Income Tax),Footnote43 with editors of leading dailies critical of the Modi government forced to quit allegedly under pressure from their proprietors.Footnote44 Censorship, previously rare, became routine. Critics of the Modi government among students, journalists, human rights activists were punished, and criticism, suppressed, using laws on sedition, defamation, counterterrorism and restrictions on foreign funding for NGOs (e.g. Amnesty International was forced to halt its India operations in September 2020 after being pursued by state agencies for several years).Footnote45 Ideational capture by the BJP has also involved novel communication and political marketing techniques (e.g. Modi’s monthly radio broadcasts addressing the nation); the use of new technologies and social media platforms to infiltrate and dominate hitherto untapped civil society spaces (notably, the BJP IT cell’s infiltration of WhatsApp friends and family groups with government propaganda and misinformation), propagating an image of ubiquitous and invincible leadership familiar from authoritarian contexts.

The pace of institutional and ideational capture speaks to the role of ideology and of non-state actors as partners, and in some cases as drivers of autocratization in India. Modi and the BJP are the current political iteration of a long-standing Hindu nationalist social tendency in India, committed to the mission of remaking India as a Hindu rashtra (state), where national identity is defined in Hindu religio-cultural terms; national unity, as security from Muslim terrorism and “foreign” threats; democracy, as rule by the Hindu majority. This ideology is underpinned by a powerful institutional infrastructure – the RSS and allied organizations have embedded themselves in civil society through decades of social work, including service provision in non-elite neighbourhoods where state provision has been lacking (e.g. youth leisure clubs, community organizations). Together with persuasion, Hindu nationalist outfits in civil society have deployed coercion, including increasingly vigilantism, acts of assault and lynching of critics, activists, Muslims, with the support of a police controlled by the BJP government, and an enfeebled judiciary unable to act against them.Footnote46 Lynching and mob violence are characteristic of democratic authoritarianism, involving a mobilization both of the strength of numbers and of the rationale that a majority’s norms ought to prevail in a land, through force if necessary.

After the Modi government was re-elected in May 2019 with a bigger plurality (around 38% of the popular vote), the second stage of entrenchment commenced, of transforming the constitutional legal framework which stands in the way of a Hindu state. The government used its legislative majority to push a new law for Jammu and Kashmir through Parliament in August 2019, revoking its nominally semi-autonomous status.Footnote47 It amended an anti-terrorism law to expand the definition of a terrorist and remove the possibility of judicial review (Unlawful Activities Amendment Act, 2019), as well as Indian citizenship law, to introduce a religious criterion for the first time, for migrants from South Asian countries that excluded Muslims (Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019).Footnote48 Coercion has been increasingly deployed to silence opponents of Hindu nationalism, with protests against these controversial laws quelled through a combination of vigilante violence by pro-government goons against protestors (e.g. Delhi 2020),Footnote49 arrests, imprisonment of students and activists under draconian laws,Footnote50 internet and communication shutdowns (e.g. Kashmir; India has imposed the longest internet shutdowns in the world), and pandemic restrictions on gatherings. The Supreme Court has sought assiduously to avoid conflict with the Modi government, issued key judgements in its favour (Ayodhya land title case, 2019), often failing to hold it to account for violations of basic constitutional rights (notably in Kashmir).Footnote51 In the meantime, a slew of Hindu nationalist legislation that enshrines the moral norms of the social majority has been enacted and/or strengthened in many states (e.g. anti-cow slaughter laws, anti-conversion and so-called love-jihad legislation), accompanied by mobilization and violence against minorities.Footnote52

As regular elections continue to be held, some have suggested that India illustrates a decoupling between democratic institutions of elections on the one hand, and rights on the otherFootnote53; however, recent evidence suggests a decline in the quality of elections as well.Footnote54 The extent to which the 2019 national election was free and fair is debatable – government ministers and BJP leaders openly made hate speeches against Muslims in election meetings, and threatened voters with adverse consequences if they did not vote for the party.Footnote55 As such, while the democratic routines of elections, parliamentary sessions and court decisions continue to be enacted in India, these appear increasingly as exercises in democratic legitimation of a form of rule that is substantially authoritarian.

Pakistan from 2017: seeking “hybrid” hegemony

Pakistan is usually classified as a “hybrid” state in which power remains contested and negotiated between civilian and military power centres.Footnote56 Historically, Pakistan’s politics has been dominated by a military-led coalition of officers, bureaucrats, judges and political parties, loosely allied around a common political agenda, of a centralized, depoliticized polity, in which ethnic identities and divisions are de-emphasized, in favour of a hegemonic national “Pakistan” identity. With the military repeatedly seizing power through coups, Pakistan is usually contrasted with India with its history of continuous, if flawed, elections. Nevertheless, substantially similar democratic authoritarian dynamics can be observed in recent years.

Since 2008, Pakistan has been ruled as an electoral democracy. However, electoral supremacy was not established, as the military retained significant autonomy, and an interventionist judiciary constrained and undermined elected governments.Footnote57 In 2010, the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and the Pakistan Muslim League (PML-N) passed the 18th constitutional amendment, decentralizing the political system, and giving ethnically distinct provinces a greater role in policymaking. Tensions also grew between these ruling parties and the military and judiciary over questions of control over foreign policy and executive appointments. In response, partisans favouring a centralized and depoliticized state, including the military, and like-minded judges and politicians in the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI), focussed on using democratic and constitutional institutions to delegitimize and push out proponents of a more decentralized, civilianized and ethnically representative state from positions of political power. Instead, they sought to populate state institutions, media and academia with like-minded partisans of a centralized and depoliticized state underpinned by a populist nationalist ideology that rejects sub-state ethnic distinctions and ideological pluralism.Footnote58

In the first stage of annexation, Supreme Court judges initiated the process of autocratization. The Pakistan Supreme Court has recently grown increasingly independent and assertive. However, contrary to the common assumption that judicial independence safeguards democracy, in Pakistan, independence has not translated into a commitment to electoral supremacy.Footnote59 Many leading judges shared the military’s disdain for political parties and vision for a more centralized and depoliticized state.Footnote60 In an interview, a former Court clerk explained, “for these judges the real problem was political corruption, and there was nothing wrong with the military helping … curb political corruption.” Between 2009 and 2018, the Court interpreted its constitutional authority and “public interest” jurisdiction expansively to intervene in all areas of political life.Footnote61 It regularly overturned executive appointments, criticized policy measures, and used populist rhetoric to criticize the PML-N and PPP for being corrupt and unrepresentative.Footnote62 The Court also expanded its powers to decide who could join the government, disqualifying politicians from elections based on allegations of corruption. Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif of the PML-N had not yet been convicted of a crime, but a misdeclaration of assets was deemed enough to be removed and banned for life from political office. Judges used populist rhetoric to legitimize this judicial aggrandizement and purging of executive and legislative branches, by tying themselves directly to the people. They claimed the constitution represented the “will of the people,” a singular undifferentiated nation, and the Court, by using its constitutional powers to remove corruption and factionalism, was realizing the will of the people. In an interview, a politician from the PPP helplessly lamented, “What can we do, when all these judges all think they are messiahs now, all come to save the people.”Footnote63 The selective purge by the judiciary between 2017 and 2018 of elected officers from the legislature and executive, created a favourable political opportunity structure for the expansion of military power.

While judicial decisions provided some space for the military’s role, the expansion of military authority and realization of its agenda via democratic-looking mechanisms required a civilian actor to provide popular legitimacy. The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI), led by the charismatic leader Imran Khan, a political outsider with large support in the country’s urban middle classes and a proven capacity to mobilize people, fit the bill. Since 2011, the military helped nurture and build organizational depth and political support for the PTI,Footnote64 which based its political campaign on a stinging critique of the corruption and ethnic factionalism of Pakistan’s “traditional” political elites. Like Modi, Imran Khan built support around his personal narrative as a political outsider liberating the nation from the crippling effects of corrupt dynastic political elites. The PTI’s populist election manifesto declared that the “legacy of misrule and misery by a corrupt inept elite will be relegated to the dustbin of history.”Footnote65

Democratic authoritarianism expanded through a process involving democratic legitimation through electoral victories and demonstrations of support beyond the state, including street protests and media capture. The PTI’s sit-in in the centre of the capital city in 2014 to protest against the PML-N’s alleged rigging of the 2013 elections, was widely covered by the media, helping ensure that corruption became the most salient political issue for the urban middle class. The Tehreek-e-Labaik Pakistan (TLP)’s sit-in Islamabad in 2017 to protest the PML-N government’s alleged softness on the issue of blasphemy, with the endorsement of Imran Khan, and the covert backing of the military, helped to further delegitimize the PML-N as weak in the face of “threats” to Islam.Footnote66 Then during its 2018 election campaign, PTI espoused an aggressive militaristic populist nationalism that de-emphasized ethnic divisions and criticized political corruption to appeal to middle-class constituencies, and formed tactical alliances with extremist religious parties.Footnote67 The military used its influence over owners of private media houses and television anchors and journalists to influence media coverage in PTI’s favour. Persuasion also involved the use of social media platforms, notably fake accounts on Facebook that were tied to military employees, and an army of Twitter accounts who worked to glorify Imran Khan and the Chief of Army Staff, and rail against political corruption and ethnic factionalism.Footnote68

The combined effect of the Court’s judgments, the pressures and incentives offered by the military to fragment the PML-N’s vote at the local level,Footnote69 the PTI’s anti-corruption electoral campaign and protests, and the military’s manipulations of media and social media narratives, enabled the PTI to win an electoral plurality in the 2018 election, and form a new government.

After 2018, this coalition of authoritarian elites sought to entrench their domination through formal capture of state institutions and silencing of dissenting views in the public sphere. The anti-corruption drive, mandated and legitimated by the electoral victory, became an instrument for eliminating political opposition. Through the National Accountability Bureau, and an array of task forces, leaders of the PML-N and PPP and allied bureaucrats were arrested on corruption charges. The PTI itself, the Supreme Court and military, remained largely immune while opposition parties were selectively debilitated. The new ruling elite also made efforts to roll-back the constitutional amendment that decentralized political authority. The Supreme Court has, in recent years, chipped away at provincial discretion in critical policy areas.Footnote70 Imran and members of his government have also criticized decentralization, and initiated action to review the provincial distribution of resources and homogenize school curricula across provinces.Footnote71

Since 2018, there was a significant drop in freedom of expression in Pakistan, with Freedom House citing actions taken by the state to curtail media freedom, including withdrawing advertising from critical publications, banning and prosecuting critical news channels, and censoring coverage of opposition rallies.Footnote72 Outside the state, mobs of PTI supporters attacked offices of media houses which were critical of the emerging regime. Universities were pressured to dismiss scholars who aligned with political organizations demanding greater ethnic representation, and some were charged with sedition.Footnote73

Thus, in a manner paralleling democratic authoritarianism in India, the very different authoritarian elite in Pakistan used a similar combination of formal institutions, informal coercion, and co-optation to limit criticism of its agenda, while delegitimizing and seeking to eliminate competition from opposition parties advocating decentralized ethnic politics and critics in civil society. A segment of the political elite, aligned across the military, Supreme Court and PTI used coercion, co-optation and persuasion in pursuit of domination and monopolistic control. The capture of state institutions, and mobilization of partisans outside the state enabled proponents of a more centralized and depoliticized political system to build legitimacy. The future of this “hybrid” hegemony is uncertain, as opposition parties seek to re-enter the political system by weakening the civilian PTI and even impeaching Imran Khan, without challenging the military’s revived supremacy, but the impact on Pakistan’s ideational and institutional structure is likely to endure for years to come.

Thus, notwithstanding their diverse regime types and trajectories, South Asian states have witnessed substantially similar processes of democratic authoritarianism, involving a concentration of unaccountable power in central institutions, enabled by ideologies of populist nationalism. South Asian cases show that autocratization today is not simply a result of executive aggrandizement, nor limited to state institutions, nor necessarily propelled by exclusionary ethnic nationalism. In their present, as in their past as Jalal had observed in 1995, South Asian states exemplify different faces of the same phenomenon, democratic authoritarianism.

Conclusion

In this article, we have sought to contribute to the emerging literature on autocratization through a new elaboration of the concept of democratic authoritarianism. We have argued for a need to redress an overemphasis in the backsliding literature on executive mechanisms of autocratization, and its relative neglect of the role of civil society and ideology as enablers of autocratization. Our notion of democratic authoritarianism, unlike previous formulations, speaks to the overall direction of change; encompasses multiple actors and routes of institutional and ideational capture, across state as well as civil society; and is applicable to regimes across the democratic – authoritarian spectrum. With political leaders across the world using the Covid-19 pandemic as a pretext to further political control, we need a concept that integrates the multiple dimensions of autocratization across different regime types into a single framework. Our case studies illuminate the range of instruments, pathways and variants of democratic authoritarianism, as well as the limits of commonly suggested constitutional and democratic checks, such as empowered judiciaries and resilient civil society.

While our concept and case studies of democratic authoritarianism seek to explain how autocratization is enabled by democratic-looking mechanisms, this is only part of the causal story. It tells us little of the conditions that account for the resurgence of autocratization over the last decade in such diverse polities. Among the conditions noted in the literature are the role of structural factors such as increasing socio-economic inequalities, class insecurity and re-alignments, the popularity of communication technologies such as social media platforms that facilitate the spread of extremist views and false information.Footnote74 Our account is compatible with these explanations, while suggesting a need for more comparative historical research to evaluate the relevance and weight of these factors and others, including historical colonial legacies of state institutions. Our framework does suggest an important, neglected explanation for variation in the pace and the extent of autocratization in different countries, namely the alignment (or lack thereof) of authoritarian actors across state and civil society institutions on the one hand, and multiple levels of the polity (federal and provincial), on the other. In India for instance, the alignment between elected executive and socio-religious organizations has accelerated the pace of autocratization, dismantling institutional resistance, whereas the federal structure has acted as a decelerator, putting brakes on the still advancing process.

Future research must also consider what conception of democracy will be sustained in the hegemony secured through democratic authoritarian processes, and how this differs from the hegemony of political elites secured through democratic processes. In democratic authoritarian formations, consent is secured more through coercion than is the case in democratic ones, and is typically forced or imposed, rather than free. As democratic processes embedded in state institutions also involve consent underpinned by coercion, what distinguishes these from democratic authoritarian processes needs elaboration.

At one level, the expansion of democratic authoritarianism demonstrates the global reach of democracy as a norm, with today’s authoritarian leaders seeking to maintain the appearance of a democratic order, even as it has become a shell largely emptied of the substance of political equality and popular rule for all. At another level, however, the rise of democratic authoritarianism poses difficult questions regarding possible dissonance between different elements of democracy, as well as contradictions between democratization as a social process, and democracy as an ideal that de Tocqueville had noted long ago, and recent scholarship has affirmed.Footnote75 Our study has shown that multiple elements of democracy are not so much decoupled but depleted, reduced to demonstrations of majoritarian support through increasingly unequal elections, engineered mass mobilizations and approved vigilantism. If greater equalization of social conditions creates tendencies toward the centralization of power in a popular autocrat, the tyranny of majority opinion, and the proliferation of falsehoods in the marketplace of ideas, then the distance between democracy as a social form on the one hand, and democratic ideals of political equality and popular rule on the other, seems even harder to bridge today than in Tocqueville’s time.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Katharine Adeney, Vatsal Naresh, Aziz ul Haq, Zoha Waseem, journal editor Aurel Croissant, and two anonymous referees for their helpful guidance, useful comments and generous feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rochana Bajpai

Rochana Bajpai is a Reader in Politics at the Department of Politics and International Studies, SOAS University of London. She is the author of Debating Difference: Group Rights and Liberal Democracy in India (Oxford University Press, 2011), and of several publications on comparative political thought, political ideas in South Asia and Southeast Asia, constitution-making, secularism, social justice, and minority representation in India.

Yasser Kureshi

Yasser Kureshi is a postdoctoral research fellow with Trinity College and the Programme for the Foundations of Law and Constitutional Government at the University of Oxford. His research focuses on judicial and constitutional politics in authoritarian and post-authoritarian states. His book, Seeking Supremacy: The Pursuit of Judicial Power in Pakistan (Cambridge University Press, 2022) is forthcoming.

Notes

1 Levitsky and Way, “Competitive Authoritarianism”; Bermeo, “Democratic Backsliding”; Scheppele, “Autocratic Legalism”; Huq and Ginsburg, “Constitutional Democracy” and Pelke and Croissant, “Conceptualizing and Measuring Autocratization Episodes.”

2 Curato and Fossati, “Authoritarian Innovations.”

3 Jalal, Democracy and Authoritarianism.

4 For consistency, and to contrast with democratization, we use the term autocratization, defined as the defacto decline of core institutional requirements for electoral democracy (Luhrmann and Lindberg, “Third Wave of Autocratization”).

5 Whether or not these are genuinely democratic is a separate issue, outside the scope of this article.

6 Vachudova, “Populism, Democracy and Party System” and Pappas, Populism and Liberal Democracy.

7 Levitsky and Way, “Competitive Authoritarianism,” 51–2.

8 Bermeo, “Democratic Backsliding”; Huq and Ginsburg, “Constitutional Democracy” and Luhrmann and Lindberg, “Third Wave of Autocratization.”

9 On authoritarian constitutions, see Ginsburg and Simpser, Constitutions in Authoritarian Regimes; On authoritarian courts, see Moustafa and Ginsburg, Rule by Law.

10 Schedler, Electoral Authoritarianism; Gandhi and Lust-Okar, “Elections under Authoritarianism” and Moustafa and Ginsburg, Rule by Law.

11 Slater and Fenner, “State Power and Staying Power,” 17.

12 Historians have paid more attention to the role of state agencies such as the military and the police in expanding authoritarianism within democracies; however, institutional dynamics have not typically received attention in this scholarship. See Jalal, Democracy and Authoritarianism.

13 See Bermeo, “Democratic Backsliding”; Scheppele, “Autocratic Legalism”; Huq and Ginsburg, “Constitutional Democracy”; Curato and Fossati, “Authoritarian Innovations.”

14 Bermeo, “Democratic Backsliding”; Khaitan, “Killing the Constitution.”

15 Haggard and Kaufman, Backsliding.

16 Ding and Slater, “Democratic Decoupling,” highlight the importance of examining decoupling between multiple democratic institutions; however, their account of decoupling is still executive-centered.

17 Some argue that populism is not an ideology in the typical sense. However, in line with Mudde and Kaltwaaser, we consider populism to be a thin ideology with a defining, if incomplete, set of ideas. On the contours of populist ideas, see Mudde and Kaltwaser, Populism; McDonnell and Cabrera “The Right-Wing Populism of India” and Rogenhofer and Panievsky, “Anti-Democratic Populism in Power.”

18 Our point here is about democratic form, distinct from the content of the ideological vision of authoritarian regimes that is outside the scope of this article.

19 Brancati, “Democratic Authoritarianism.”

20 Ayesha Jalal used the term “democratic authoritarianism” to argue that post-colonial states of South Asia combined both democratic and authoritarian elements. Kanchan Chandra has described democratic authoritarianism as an admixture in which authoritarian elements co-exist with democratic ones. See Jalal, Democracy and Authoritarianism and Chandra, “Authoritarian Elements in Democracy.”

21 Our usage of “democracy” here is more descriptive than normative, hence the qualifier democratic-“looking.” For other uses of “democratic-looking” see Slater and Fenner, “State Power and Staying Power.”

22 In a hegemonic system, the authority of the hegemonic party is not uncontested, but challenges do not come from elites within the political system. See Bajpai and Brown, “From Ideas to Hegemony.”

23 In the Indian context, see Palshikar, “BJP Beyond Electoral Dominance.”

24 Peluso, “Judges and Courts.”

25 Huntington and Moore, Authoritarian Politics and Linz, Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes.

26 For overviews, see e.g. Mudde and Kaltwasser, Populism and Vachudova, “Populism, Democracy and Party System.”

27 Mudde and Kaltwasser, Populism.

28 See Hansen, “Democracy Against the Law,” on ideologies of popular sovereignty in India.

29 Khaitan, “Killing the Constitution.”

30 On the RSS as a civil society organization pursuing social and cultural transformation from below, see Jaffrelot, “A De-Facto Ethnic Democracy?” 54–63.

31 Bateson, “Politics of Vigilantism,” 927 and Jaffrey, “Populism and Vigilante Violence.”

32 In the context of Hindu nationalist vigilantism in India, Jaffrelot notes that the state out-sources or “subcontracts policing tasks to non-state actors, turning them into a para-state force” (Jaffrelot, “A De-Facto Ethnic Democracy?” 61).

33 On the links between violence and popular sovereignty in India, see Hansen, “Democracy Against the Law.”

34 Lorch, “Elite Capture, Civil Society.”

35 For different accounts of stages of autocratization, see Levitsky and Ziblatt, “How Democracies Die” and V-Dem, “Autocratization Turns Viral.”

36 V-Dem report (2021, 19); V-Dem report (2022, 24). In 2021, India’s status was downgraded to electoral autocracy by V-Dem, and to partially free by Freedom House, where it remains in 2022.

37 See Chandra, “Authoritarian Elements”; Khaitan, “Killing the Constitution.”

38 See Jaffrelot, “A De-Facto Ethnic Democracy?.”

40 Sebastian, “Supreme Court Modi Years.” https://thewire.in/law/supreme-court-modi-years.

41 See e.g. Khaitan, “Killing the Constitution.”

42 On the ways in which the BJP governments since 2014 have undermined academic freedom in numerous institutions in India and Kashmir, see Sunder and Fazili, “Academic Freedom in India.” The India Forum.

43 See Rajput, “NDTV Founders Detained.” https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/ndtv-founders-detained-at-city-airport-roys-say-fake-case/articleshow/70609683.cms.

44 On the sacking of Bobby Ghosh editor in chief of The Hindustan Times who had launched a database for hate crimes, allegedly under government pressure, see Srivas, “Hindustan Times Editor,” September 25, 2017. https://thewire.in/media/hindustan-times-bobby-ghosh-narendra-modi-shobhana-bhartia.

45 Sedition cases have seen a 28% increase between 2014 and 2020 compared to the previous yearly average, see Purohit, “Database Reveals Rise in Sedition Cases.” https://www.article-14.com/post/our-new-database-reveals-rise-in-sedition-cases-in-the-modi-era” and Limaye, “Amnesty International.” https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-54277329.

46 On RSS support for vigilantism and cultural policing, see Jaffrelot, “A De-Facto Ethnic Democracy,” 54–64.

47 On the revocation of Article 370, subsequent arrests of senior politicians, torture and human rights abuses by Indian forces in Kashmir, see Zargar, “A Year of Turmoil.” 2020. https://www.newframe.com/a-year-of-turmoil-and-traumatic-loss-in-kashmir/August.

48 The controversial law offers a fast-track route to Indian citizenship to non-Muslim migrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan residing in India, in effect reserving “the category of ‘illegal migrant’ for Muslims alone.”

49 Subramanian, “Indian Supremacists.” https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/feb/20/hindu-supremacists-nationalism-tearing-india-apart-modi-bjp-rss-jnu-attacks.

50 Alam, “2020 for India’s Journalists.” https://thewire.in/media/journalists-arrested-press-freedom-2020.

51 Bhawani, “The Crisis of Legitimacy.” https://scroll.in/article/979818/the-crisis-of-legitimacy-plaguing-the-supreme-court-in-modi-era-is-now-hidden-in-plain-sight.

52 See Patel, “The Many Anti-Muslim Laws.” https://thewire.in/politics/price-of-the-modi-years-book-excerpt; Ganguli, “India’s Religious Minorities.” https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/12/30/india-religious-minorities-under-attack-christian-muslim-modi-bjp/.

53 Ding and Slater, “Democratic Decoupling.”

54 E.g. V-Dem data 2021, 2022.

55 The BJP rejected the use of voting machines designed to ensure the anonymity of booth-level data – see Banerjee, “The New Indian Election.” https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2019/05/10/the-new-indian-election-free-but-not-fair/.

56 Adeney, “How to Understand Pakistan's Hybrid Regime.”

57 Shah, “Constraining Consolidation.”

58 Talbot, “Pakistan’s Hybrid Regime.”

59 Kureshi, “Judicial Politics in Hybrid Regimes.”

60 See Azeem, Law, State and Inequality and Aziz, “Politics of Anti-Corruption.”

61 Siddique, “Judicialization of Politics.”

62 Mir, “Judicial Restraint.” https://www.dawn.com/news/1458321.

63 Interview with a politician, December 3, 2020.

64 Shah, “Voting under Military Tutelage.”

65 For a cross-national account of anti-democratic populism, see Rogenhofer and Panievsky, “Anti-Democratic Populism in Power.”

66 “Faizabad sit-in, Imran Khan.”

67 Altaf, “ASWJ Reveals Backing PTI.” https://tribune.com.pk/story/1772875/aswj-reveals-backing-pti-70-constituencies.

68 Sayeed, “Facebook Removes Accounts Linked to Pakistani Military Employees.” https://www.reuters.com/article/us-facebook-accounts-pakistan-idUSKCN1RD1R6.

69 Shah, “Voting under Military Tutelage.”

70 Niazi, “18th Amendment and the Supreme Court.” https://tribune.com.pk/story/2224292/18th-amendment-supreme-court.

71 Hasan, “Flaws in Single National Curriculum.” https://www.dawn.com/news/1574777.

72 “Freedom in the World 2021: Pakistan Country Report.”

73 Gabol, “Sedition Cases Registered.” https://www.dawn.com/news/1519976.

74 In India, the rise of the BJP has been explained as an upper caste -reaction to the expansion of quotas to lower castes since the 1980s, and linked to the growth of a middle-class.

75 See Ding and Slater, “Democratic Decoupling.”

Bibliography

- Adeney, Katherine. “How to Understand Pakistan’s Hybrid Regime: The Importance of a Multidimensional Continuum.” Democratization 24, no. 1 (2015): 119–137.

- Althusser, Louis. Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. Paris: Monthly Review Press, 1970.

- “Autocratization Turns Viral.” Democracy Report. Varieties of Democracy, 2021.

- “Autocratization Changing Nature?” Democracy Report. Varieties of Democracy, 2022.

- Azeem, Muhammad. Law, State and Inequality in Pakistan: Explaining the Rise of the Judiciary. Singapore: Springer International Publishing, 2017.

- Aziz, Sadaf. “The Politics of Anti-Corruption.” In The Politics and Jurisprudence of the Chaudhry Court, edited by Moeen Cheema and Ijaz Shafi Gilani, 253–280. Karachi: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Bajpai, Rochana, and Graham Brown. “From Ideas to Hegemony: Ideational Change and Affirmative Action Policy in Malaysia: 1955-2010.” Journal of Political Ideologies 18, no. 3 (2013): 257–280.

- Bateson, Regina. “The Politics of Vigilantism.” Comparative Political Studies 54, no. 6 (2021): 923–955.

- Bermeo, Nancy. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27, no. 1 (2016): 5–19.

- Brancati, Dawn. “Democratic Authoritarianism: Origins and Effects.” Annual Review of Political Science 17 (2014): 313–326.

- Chandra, Kanchan. “Authoritarian Elements in Democracy.” Seminar, 2017.

- Curato, Nicole, and Diego Fossati. “Authoritarian Innovations: Crafting Support for a Less Democratic Southeast Asia.” Democratization 27, no. 6 (2020): 1006–1020.

- DeVotta, Neil. “Knocked Down, Getting Backed Up.” Global Asia 15, no. 1 (2020): 42–47.

- Ding, Iza, and Dan Slater. “Democratic Decoupling.” Democratization (2021). doi:10.1080/13510347.2020.1842361.

- “Freedom in the World 2022.” Freedom House, 2022.

- Gandhi, Jennifer, and Ellen Lust-Okar. “Elections under Authoritarianism.” Annual Review of Political Science 12 (2009): 403–422.

- Ginsburg, Tom, and Alberto Simpser, eds. Constitutions in Authoritarian Regimes. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- Hansen, Thomas Blom. “Democracy Against the Law: Reflections on India’s Illiberal Democracy.” In Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism is Changing India, edited by Angana P. Chatterji, Thomas Blom Hansen, and Christophe Jaffrelot, 19–40. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Huntington, Samuel, and Clement Moore, eds. Authoritarian Politics in Modern Society. New York: Basic Books, 1970.

- Huq, Aziz, and Tom Ginsburg. “How to Lose a Constitutional Democracy.” UCLA Law Review 65 (2018): 95–170.

- Jaffrey, Sana. “Right-Wing Populism and Vigilante Violence in Asia.” Studies in Comparative International Development 56, no. 2 (2021): 223–249.

- Jaffrelot, Christophe. “A De-Facto Ethnic Democracy? Obliterating and Targeting the Other, Hindu Vigilantes and the Ethno-State.” In Majoritarian State: How Hindu Nationalism Is Changing India, edited by Angana Chatterji Thomas Hansen and Christophe Jaffrelot, 41–57. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Jalal, Ayesha. Democracy and Authoritarianism in South Asia: A Comparative and Historical Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Haggard, Stephan, and Robert Kaufman. Backsliding: Democratic Regress in the Contemporary World. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Khaitan, Tarunabh. “Killing a Constitution with a Thousand Cuts: Executive Aggrandizement and Party-State Fusion in India.” Law and Ethics of Human Rights 14, no. 1 (2020): 49–95.

- Kureshi, Yasser. “Judicial Politics in Hybrid States: Judiciary and Political Parties in Pakistan.” In Pakistan’s Political Parties: Against All Odds, edited by Mariam Mufti, Niloufer Siddiqui, and Sahar Shafqat, 235–252. Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2020.

- Levitsky, Steve, and Lucian Way. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Levitsky, Steve, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die: What History Reveals About Our Future. London: Penguin, 2018.

- Linz, Juan. Totalitarian and Authoritarian Regimes. New York: Lynne Reinner, 2000.

- Lorch, Jasmin. “Elite Capture, Civil Society and Democratic Backsliding in Bangladesh, Thailand and the Philippines.” Democratization 28, no. 1 (2021): 81–102.

- Luhrmann, Anna, and Staffan Lindberg. “A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here: What Is New About It?” Democratization 26, no. 7 (2019): 1095–1113.

- McDonnell, D., and L. Cabrera. “The Right-Wing Populism of India’s Bharatiya Janata Party (and Why Comparativists Should Care).” Democratization 26, no. 3 (2019): 484–501.

- Mostafa, Shafi, and D. B. Subedi. “Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism in Bangladesh.” Politics and Religion 14, no. 3 (2021): 431–459.

- Moustafa, Tamir, and Tom Ginsburg, eds. Rule by Law: The Politics of Courts in Authoritarian Regimes. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristobal Kaltwasser. Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Palshikar, Suhas. “BJP Beyond Electoral Dominance: Towards hegemony.” Economic & Political Weekly 53, no. 33 (2018): 36–42.

- Pappas, Takis. Populism and Liberal Democracy: A Comparative and Theoretical Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Pelke, Lars, and Aurel Croissant. “Conceptualizing and Measuring Autocratization Episodes.” Swiss Political Science Review 27, no. 2 (2021): 434–448.

- Peluso, Neder Meyer. “Judges and Courts Destabilizing Constitutionalism: The Brazilian Judiciary Branch’s Political and Authoritarian Character.” German Law Journal 19, no. 4 (2018): 727–768.

- Riaz, Ali. “The Pathway of Democratic Backsliding in Bangladesh.” Democratization 28, no. 7 (2021): 179–197.

- Rogenhofer, Julius, and Ayala Panievsky. “Antidemocratic Populism in Power: Comparing Erdogan’s Turkey with Modi’s India and Netanyahu’s Israel.” Democratization 27, no. 8 (2020): 1394–1412.

- Sanjeev, Laxmanan. “Is Sri Lanka Becoming a DeFacto Junta?” Foreign Policy, July 17, 2020.

- Schedler, Andreas. Electoral Authoritarianism: The Dynamics of Unfree Competition. Boulder, CO: Lynne Reinner, 2006.

- Scheppele, Kim. “Autocratic Legalism.” University of Chicago Law Review 85 (2018): 546–583.

- Shah, Aqil. “Constraining Consolidation: Military, Politics and Democracy in Pakistan (2007–2013).” Democratization 21, no. 6 (2014): 1007–1033.

- Shah, Aqil. “Pakistan: Voting Under Military Tutelage.” Journal of Democracy 30, no. 1 (2019): 128–142.

- Siddique, Osama. “Judicialization of Politics: Pakistan Supreme Court’s Jurisprudence after the Lawyer’s Movement.” In Unstable Constitutionalism: Law and Politics in South Asia, edited by Mark Tushnet and Madhav, 159–191. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Slater, Dan, and Sofia Fenner. “State Power and Staying Power: Infrastructural Mechanisms and Authoritarian Durability.” Journal of International Affairs 65, no. 1 (2011): 15–29.

- Sundar, Nandini, and Gowhar Fazili. “Academic Freedom in Induia: A Status Report, 2020.” The India Forum, August 27, 2020. https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/academic-freedom-india.

- Talbot, Ian. “Pakistan’s Hybrid Regime.” In Routledge Handbook of Autocratization in South Asia, edited by Sten Widmalm, 141–150. Oxford: Routledge, 2022.

- Vachudova, Milada. “Populism, Democracy and Party System Change in Europe.” Annual Review of Political Science 24 (2021): 471–498.

- Waldner, David, and Ellen Lust-Okar. “Unwelcome Change: Coming to Terms with Democratic Backsliding.” Annual Review of Political Science 21 (2018): 93–113.

- Widmalm, Sten, ed. Routledge Handbook of Autocratization in South Asia. London: Routledge, 2022.