ABSTRACT

Social service provision by non-state actors is cited as an important factor in maintaining authoritarian regime stability in the Middle East. By facilitating their growth regimes ease the burden on their own shrinking resources and avoid resultant social unrest. But these arrangements are not politically risk free, with Islamic opposition groups able to develop substantial social capital. After the Arab Spring, in which regimes faced mass mobilization, and in some cases, nascent democratization, authoritarian elites adapted and transformed their tactics of control to contain newly mobilized societies. Focusing on the crackdown on Islamic service providers in Egypt since 2013, this article shows when a process of democratic transition is reversed, reviving previous arrangements of non-state service provision is deemed unsustainable due to continued political threat. In response, a model of reconstituted authoritarianism is developed that sees the utilization of the state apparatus to extend “direct” controls over non-state service provision, through four strategies: nationalization, corporatization, extraction, and state building. However, the sustainability of this strategy is tempered by state capacity. The article offers a path to increased understanding of authoritarian adaptation after the Arab Spring, and the role of service provision in maintaining regime stability.

Introduction

The authoritarian upgrading literature cites the importance of non-state service provision in maintaining regime stability in Middle East states. Facilitating the growth of civil society organizations – especially Islamic ones – to provide services allows authoritarian regimes to ease the burden on their shrinking resources and avoid social unrest.Footnote1 Administrative and bureaucratic regulation enables control over these groups in an “indirect” form.Footnote2 Yet these arrangements are not politically risk free, with opposition groups able to develop substantial social capital.Footnote3 After the 2011 Arab Spring, when regimes faced mass mobilization, and nascent democratization, the upgrading strategies that proved so effective “carried social costs that they could not contain indefinitely”.Footnote4 Authoritarian elites responded by transforming their tactics to “contain newly mobilized societies”.Footnote5 Focusing on Egypt’s crackdown on Islamic associations, this article shows when democratic transitions are reversed, regimes can revise previous arrangements of non-state service provision due to their political threat. But how do reconstituted authoritarian regimes reduce their reliance on non-state service provision, whilst maintaining regime stability? This article argues that authoritarian regimes can use state institutions to assume “direct” control over the operations of non-state service providers, whilst reinvigorating the state’s own service apparatus.

The Egyptian state’s relations with Islamic associations began changing after a coup d’état deposed its first democratically elected president on 3 July 2013, the Muslim Brotherhood’s Mohamed Morsi, following a two-year transitional period. Over the following months the state, de facto led by then Minister of Defence, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, undertook measures to eradicate the Brotherhood as a social and political force. Morsi was imprisoned alongside the organization’s General Guide, Mohammed Badie, and his deputy Khairat al-Shater. On 14 August, security forces killed at least 800 Brotherhood supporters during a sit-in at Cairo’s Rabaa al-Adawiya Square. Thousands more were arrested as the authorities banned the group and seized their headquarters. The Brotherhood’s social base was linked to the services provided by Islamic associations. In December 2013, 1055 Islamic associations were seized under the premise of their exploitation for political support.Footnote6 Whilst previously encouraging these Islamic actors to provide services, this move confounded expectations around the role of non-state actors and service provision in transitioning authoritarian regimes.

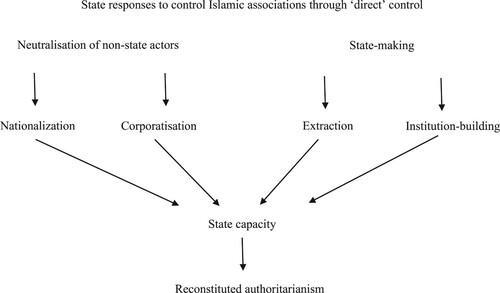

This article builds theory on the role of non-state service provision in re-establishing authoritarian rule. Drawing on Charles Tilly’s work on “war making and state making”, it develops a model of reconstituted authoritarianism comprising four strategies: nationalization, corporatization, extraction, and institution-building. Nationalization and corporatization are aimed at neutralizing non-state opponents, while extraction and institution-building are components of state making, aimed at increasing the state’s service provision role and relatedly, reliance on non-state actors. Through nationalization the assets of associations were seized with their capabilities incorporated into state ministries. Corporatization is a form of co-optation which allowed associations to retain formal autonomy, but with enhanced state controls over budgets and management appointments. Extraction saw appropriation of resources from society, through the creation of new state institutions for collecting and distributing Islamic charity for use in state projects. Institution-building involved the reinvigoration of the state’s service apparatus, aided by external support and an increased role for the Egyptian military. However, the long-term feasibility of these strategies is tempered by state capacity, which determines whether authoritarian consolidation is based on governance or coercion.

Previous literature focused on the expanding role of Islamic associations under authoritarian regimes in Egypt and the Middle East in the 1990s and 2000s.Footnote7 Since Morsi’s deposal, studies have detailed the state’s repression of the Brotherhood’s movement,Footnote8 and the wider crackdown on Islamic social and religious institutions, including state efforts to control private mosques and preaching.Footnote9 While the threat al-Sisi’s regime presents to civil society has been highlighted,Footnote10 relatively less attention has been given to repression of Islamic associations. The most detailed study gave an overview of the state’s seizure of the Brotherhood’s schools and medical facilities, using it to exemplify the adoption of more confrontational opposition methods.Footnote11 This article provides empirical depth by charting systematically the consequences for seized organizations, and applies this wider strategy of controlling Islamic service provision to conceptualize state-society relations under al-Sisi and its adapted form of authoritarian rule.

The article firstly situates the case study within the authoritarian resilience literature. A note on data collection precedes a brief history examining the service provision balance between Islamic associations and the state across the regimes of Nasser, Sadat, Mubarak, and the 2011–2013 transition. The empirical sections detail the crackdown on Islamic associations through the strategies of nationalization, corporatization, extraction, and institution-building. The penultimate section draws on Tilly’s theory to create the theoretical model of reconstituted authoritarianism, with the implications of these findings discussed in the conclusion.

Authoritarian resilience

The literature on authoritarian resilience centres on the “three pillars of stability”: repression, legitimation, and co-optation.Footnote12 Egypt’s re-establishment of authoritarian rule has relied heavily on repression, with violence against the Brotherhood being justified through “securitization”, constructing the group as an existential threat,Footnote13 as part of an elite pact against political Islam.Footnote14 But repression can have mixed effects. The violent response to anti-coup protests among Islamist activists in 2013 led to the suppression of tactics like mass public gatherings, which evolved into smaller, flexible, decentralised forms of mobilization which better evaded regime repression.Footnote15 Consequently, authoritarian consolidation requires regimes to “substitute coercion for governing by organization, regulation”,Footnote16 signalling the need for further stabilizing factors.

Through legitimation, authoritarian regimes pursue active consent among the population, or minimally, passive obedience and compliance.Footnote17 Legitimation strategies vary by regime type, with closed regimes relying on identity-based legitimacy claims, while competitive regimes use elections to mimic democratic features.Footnote18 Al-Sisi relies more on the former, with a highly personalized claim to legitimacy, with his missionary role substituting for ideology.Footnote19 Representations of external actors as threats to domestic political developments have also legitimized the expansion and political influence of the military.Footnote20 Religious legitimacy is sought through using the popularity of al-Azhar, the semi-official religious and historic body of Islamic learning, for political legitimisation.Footnote21

Authoritarian regimes also engage in co-optation, an inclusionary process strategically tying relevant actors to regime elites to prevent them becoming political opponents.Footnote22 Existing literature focuses on political parties’ ability to provide institutionalized access to the spoils of power,Footnote23 or clientelist distribution of goods for continued support.Footnote24 In Egypt under Sadat and Mubarak, the state incentivised religious actors to engage in welfare provision to alleviate pressures resulting from declining state services, as long as they were “depoliticized”.Footnote25 In regimes returning to authoritarian rule after mass uprisings, protest movements can be fragmented by co-opting some movement actors, while repressing others posing a political threat to the regime.Footnote26 A similar policy under al-Sisi has fragmented Egypt’s Islamist movement, with the repression of the Brotherhood contrasting with the co-optation of their Salafi counterparts.Footnote27

Although Egypt’s re-establishment of authoritarianism draws heavily on this tripod of strategies, it doesn’t fully explain the range of measures used after periods of mass mobilization and democratization. In these circumstances, I argue, strategies of “indirect” control, such as co-optation, may require “direct” supplements to consolidate authoritarian rule. In other cases, the threat of Islamic associations has been confronted through “direct” controls, including nationalizations of private institutions.Footnote28 Drawing on Michael Mann’s work, “direct” controls see authoritarian regimes increasingly develop “infrastructural power” to penetrate and control civil society.Footnote29 “Direct” control is reflective of statism, or centralized state control over social and economic spheres. Under Mubarak, the dismantlement of the public sector meant that the Nasserist doctrine of state-guided economic development, including state provision of education and health care, was cast off.Footnote30 Egypt’s political economy under al-Sisi has reintroduced statist elements.Footnote31 This article identifies the use of statism to control social service sectors as a tactic of authoritarian control. The crackdown on Islamic associations in Egypt indicates a move away from “indirect” co-optation towards a form of “direct” control over social sectors engaged in service provision. A renewed focus on statism and control over service provision indicates a shift in Egyptian authoritarianism. This is suggestive of revised state-society relations in regimes seeking to reconstitute authoritarianism after a period of democratization, which is theorized further following the presentation of empirical results.

Data collection

Due to security concerns, fieldwork for this research was not possible. Nevertheless, original primary source material from open-source Arabic-language sources provided a workable alternative. From January 2014 until May 2016, Egypt’s Ministry of Social Solidarity (MOSS) made monthly pronouncements on its website of the fate of seized associations, which were reported by the Egyptian press. This article relies on these press sources, which, in addition to providing numbers of associations seized, nationalized, or subject to closure, also included extended comments from relevant government officials. Further background information was gathered from a systematic process to cover every available edition of online and print news sources between June 2013 and December 2016, while less frequent searches were conducted between 2016 and 2019. Key search terms were used for online searches in the archives of newspapers, including associations (jam‘iyyat), and the verb to denote the crackdown process (ḥal). Using these terms located hundreds of articles detailing relevant events involving the state’s crackdown on Islamic associations.

There are limitations in relying on newspaper accounts. These reports effectively relay Egyptian government announcements on the takeover process, without further scrutiny, due to tightening restrictions on press freedoms in Egypt. Some reports do indicate the impact of the crackdown on Islamic associations and their volunteers, either those that were targeted or the impact on others who suffered as a result.Footnote32 As such, these sources provide an account of the seizure process, and the immediate fortunes of each association, i.e. nationalization or corporatization. What they cannot tell us are the various trends in the trajectory of these organizations since this initial period, such as whether nationalized associations have continued to operate, or eventually ceased to function. This can only be determined through further research, such as fieldwork, if and when this is possible, or through the research of Egyptian-based scholars.

Islamic associations, service provision, and the Egyptian state

Islamic associations represent part of a “mixed economy of charity”, the extent of their involvement in service provision fluctuating vis-à-vis the state and its own service apparatus.Footnote33 This section charts Egypt’s mixed economy of service provision between the state and Islamic associations during Egypt’s republican era, focusing on the regimes of Nasser, Sadat, Mubarak, and the 2011–13 transitional period.

In 1952, the Free Officers’ Movement, led by Gamal Abdel Nasser, launched a successful coup to end monarchical rule. The desire for economic growth alongside wealth redistribution led to the creation of a welfare state, with universal healthcare, social assistance, and poverty alleviation schemes.Footnote34 This established the state as the primary benefactor of Egyptians.Footnote35 Article 66 of Law 32 accorded “public status” for associations demonstrating significant efficacy and national scope, allowing their absorption into the state’s bureaucracy.Footnote36 In the 1960s, large charitable organizations providing health services came under government administration,Footnote37 alongside hospitals and other service providers,Footnote38 including those belonging to the Brotherhood.Footnote39 Legal frameworks also curtailed associational autonomy. Law 384 of 1956 authorized the state to dissolve associations posing a security threat,Footnote40 with Islamic associations prominent targets. In 1966, the management board of al-Gam‘iyya al-Shar‘iyya was dissolved and replaced by government appointees.Footnote41 In 1969, Ansar al-Sunna was forced to merge with al-Gam‘iyya al-Shar‘iyya for several years.Footnote42 Under Nasser the state increasingly dominated the service sector and Islamic associations.

Islamic associations proliferated as an alternative to the state in the service sector after Anwar Sadat became president in 1970. He shifted the state’s economic orientation from socialism towards capitalism by initiating economic liberalization, or infitaḥ,Footnote43 retracting the state’s universal commitment to health and education. Health programmes faced increased user demand with fewer resources. Public hospitals were left in squalor, with nursing shortages and deterioration in equipment quality.Footnote44 Developing the private health sector was promoted, with new private clinics and hospitals opening.Footnote45 This coincided with the facilitation of Islamic movements in civil society. Islamic activism was encouraged on university campusesFootnote46 and the Brotherhood was allowed to re-establish charitable networks.Footnote47

After Sadat’s assassination in 1981, Hosni Mubarak assumed the presidency, continuing economic liberalization and encouraging civil society growth. Amidst a fiscal crisis, an economic reform programme (ERSAP) was agreed with the IMF and World Bank in 1991 to reinvigorate economic liberalization.Footnote48 The impact of this pro-market, anti-statist economic approach was a further decline in state welfare, and increasing NGO activity.Footnote49 In Mubarak’s first decade in power, NGOs increased from around 10,000 to 12,832.Footnote50 Within two years of ERSAP’s launch they reached 14,000, rising to 20,000 by 2000.Footnote51 On the eve of Mubarak’s deposal in 2011, NGOs numbered more than 30,000.Footnote52 In the mid-1980s Islamic associations represented about 35% of all voluntary associations, rising to 43% in 1991. By 1993 they comprised a majority – more than 8000 out of a 14,000 total.Footnote53

The Egyptian government facilitated this burgeoning Islamic service sector to alleviate pressure during economic restructuring. The Ministry of Awqaf (religious affairs) pursued its majhud dhati (self-help) policy, encouraging private mosques and Islamic associations to engage in social service provision.Footnote54 Control functions accompanied this encouragement of associational activity. Law 32 of 1964 and its replacement, Law 53 of 1999, provided measures to prevent civil society organizations from engaging in political activity, placing them at risk of closure.Footnote55 As a result, under Mubarak, these Islamic social services “passively” produced social capital for Islamists such as the Brotherhood, through competent and depoliticized services.Footnote56

Mubarak’s removal in 2011 and the initiation of a transitional period bringing open elections presented new opportunities for Islamic actors to challenge the norm of depoliticized services. The Brotherhood deployed “highly politicized mobile medical caravans to establish essentially clientelist linkages with Egypt’s poor” in support of parliamentary and presidential campaigns in 2012 and 2013.Footnote57 After taking the presidency and forming a government, they launched another highly politicized service campaign in January 2013. This five-month effort represented “a nationwide effort at voter mobilization” to boost the Brotherhood’s prospects in expected parliamentary elections later that year.Footnote58 “Together We Build Egypt” included more than 2000 medical caravans, 1635 co-operative food markets, 1534 school refurbishments, 827 street cleaning efforts, and 257 craftsmen delivering household repairs.Footnote59 But this politicization had repercussions for the wider Islamic service sector after the 2013 coup and authoritarian reconstitution under al-Sisi.

The crackdown on Islamic associations under al-Sisi

After Morsi’s deposal, the Egyptian state under al-Sisi undertook a campaign to neutralize the Brotherhood’s threat, with social services a prime target. This section details the four strategies used for “direct” control over the Islamic service sector – nationalization, corporatization, extraction, and institution-building – which are then combined to build the theoretical model of reconstituted authoritarianism. The legal process for the Brotherhood’s dismantlement began on 23 September 2013, when the Court for Urgent Matters banned “all activities” of the group and “any institution derived from it”.Footnote60 This ruling facilitated the crackdown on social institutions with alleged Brotherhood affiliations, with 1055 Islamic associations seized on 23 December.Footnote61 At the beginning of 2011, 31,000 associations were registered with MOSS, rising to 35,500 during the transitional period,Footnote62 at least half being Islamic-based.Footnote63 Seized associations therefore represented around 6% of the total number of Islamic associations in Egypt, indicating a targeted strategy over associations deemed a political threat, rather than a wholesale takeover.

The fate of seized associations was determined through regional committees formed across Egypt’s 27 governorates, comprising representatives of the MOSS, the General Federation of NGOs (GFNGOs), and other economic and administrative “experts”.Footnote64 In each governorate, lists of seized associations passed to regional GFNGOs branches, which audited management boards, their activities and financial positions, before providing recommendations to MOSS.Footnote65 Beginning in February 2014, MOSS made monthly announcements on the fate of seized associations. shows the outcome of either nationalization or corporatization for seized associations from the first pronouncements until their end on March 2016.

Table 1. Nationalization.

A large majority of seized associations, 743 out of 989 were nationalized, with their registration dissolved, and full control of any assets or operations being placed in the hands of state ministries or used as subsidies for other state-led associations.Footnote66 Justification for dissolution included absence of discernible presence, such as a headquarters or on-the-ground activities. Those identified as “major associations” with “visible activities” such as health or education services continued to operate.Footnote67 These associations became managed and controlled directly through the ministries of Social Solidarity, Health, and Education.

The most prominent example of nationalization was the January 2016 absorption of all 28 of the Islamic Medical Association’s (IMA) branches into the Ministry of Health. The IMA was a well-known Brotherhood affiliate and the centrepiece of its service apparatus. Founded in 1978, the IMA began as a single charitable medical clinic in Cairo, before expanding nationwide.Footnote68 The IMA was highly revered within the Brotherhood, with the association’s secretary general and parliamentarian, Gamal Heshmat, lamenting its seizure on Facebook: “When I heard the news, I felt like they killed or arrested a son of mine. They are brutally demolishing all we ever built”.Footnote69 Egypt’s former Grand Mufti Ali Goma‘a, who provided Islamic legal justifications for the massacre of Brotherhood anti-coup protestors at al-Nahda and Rabaa al-Adawiya squares in August 2013,Footnote70 was appointed the new IMA chair. The Brotherhood’s flagship social institution was taken over by a state committed to the group’s eradication, with its new figurehead a prominent figure of “official” Islam actively promoting that process.

Nationalization extended to 50 hospitals, 100 schools, and 70 nurseries.Footnote71 Further seizures included the assets of more than 700 individuals, 532 companies, 2 factories, 14 currency-exchanges, 522 regional headquarters, and 400 feddans of agricultural land.Footnote72 Five publishing houses were taken over by the Ministry of Culture.Footnote73 The warehouses and 15 branches of Zad supermarkets, owned by Brotherhood deputy-chair, Khairat al-Shater, were confiscated.Footnote74 Police forces also closed 26 branches of the supermarket chain Seoudi, owned by a Brotherhood-affiliated businessman. The Ministry of Supply reopened the outlets through a state-run holding company.Footnote75 By absorbing food distribution networks set up by the Brotherhood the state added to its own service infrastructure.

Through nationalizations, the Egyptian state assumed direct control over a variety of service providers with varying Brotherhood affiliations, including charitable associations, health and education providers, and food distribution networks. The nationalization strategy represents an attempt to eradicate domestic rivals by incorporating them into the state apparatus, thus providing increased state legitimation.

Corporatization

Corporatism is a form of co-optation, where NGO’s retain formal autonomy, yet with enhanced state controls over budgets and management appointments. Under corporatist state-society relations, “representative” organizations for civil society act as “regulatory agencies on behalf of the state”.Footnote76 These agencies license social actors under their umbrella,Footnote77 creating a dependent relationship where economic benefits are released in exchange for ceding organizational autonomy, like leader selection.Footnote78

The corporatization strategy was engineered towards ensuring continuing services but with enhanced state oversight to prevent venture into political activism. This saw financial controls and management changes in 246 associations, for “links to the terrorist Brotherhood” and “financial irregularities”.Footnote79 After the replacement of management boards, an association’s finances would be released subject to approval from the MOSS and GFNGOs,Footnote80 allowing their continuation under the supervision of a state-appointed board. This applied to al-Gam‘iyya al-Shar‘iyya, a major nationally-networked Islamic association, which had 138 of its 1100 branches seized. A collaborative process between MOSS and GFNGOs aimed to purge the branches of Brotherhood influence. Oversight of the groups’ leadership was accompanied by a licence to solicit donations under a detailed auditing process. On 1 April 2015, the MOSS licensed al-Gam‘iyya al-Shar‘iyya to raise £50 m EGY ($3 m) for the following financial year, but under strict oversights over its collection and use.Footnote81 Receipts for all donations and their spending within each branch were to be handed over to the MOSS for auditing. The state’s corporatization strategy thereby enforced a strict scrutinization over the finances and projects of one of Egypt’s most prominent non-state providers.

Extraction: state appropriation of Islamic charity

Egypt’s Islamic associations have been described as “a largely ‘unincorporated’ class”,Footnote82 due to their autonomous source of financing through zakat donations.Footnote83 Religious charitable endowments were exempt from state supervision under Law 32, which restricts independent collection of funds for associations.Footnote84 In January 2014, the Minister of Awqaf announced the funds of all Islamic associations would be more closely monitored.Footnote85 A task force was formed to monitor mosques, religious lessons, and prayers, to prevent any association soliciting or collecting donations.Footnote86

Subsequently, a new state-sanctioned institution was created to collect and distribute Islamic charity. Established in 2014, Bayt al-Zakat is an ostensibly independent body.Footnote87 Its statutes define its organizational structure as independent from government, under the supervision of al-Azhar and headed by its Grand Shaykh, Ahmed al-Tayyib. However, state representation is strong on its board of directors, which includes al-Tayyib, a General Secretary, the Minister of Awqaf, representatives of other ministries, as well as a team of experts in administration, economics, and other fields.Footnote88 The general secretary of Kuwait’s own Bayt al-Zakat is also on the board, alongside representatives of state-led Gulf charities from Bahrain and the UAE.Footnote89 The establishment of Egypt’s Bayt al-Zakat was modelled on Kuwait’s institution, with guidance from other Gulf states who established stringent oversights over charitable endowments. Unlike its Gulf counterparts, Egypt’s Bayt al-Zakat relies on voluntary zakat donations, limiting the amount it can extract.

Bayt al-Zakat’s method of collection includes the opening of dedicated bank accounts enabling wire transfer of zakat donations.Footnote90 Other methods include a dedicated telephone line, or an SMS, with each message costing £10 EGY.Footnote91 In 2015, its first year of operation, Bayt al-Zakat’s budget for the period from February to September was roughly £350 m EGY (around $20 m).Footnote92 During this period, it received millions in payments from prominent businessmen, whilst Bahrain and the UAE also made significant contributions.Footnote93 It is estimated that around 75% of zakat donations are made during Ramadan, falling across June and July in 2015. Although this figure refers only to an 8-month period, the full accounts of this first year were unlikely to be substantially above this £350 m EGY figure. By 2019, the yearly budget of Bayt al-Zakat had more than doubled to reach £800 m EGY.Footnote94 Although a significant increase, it remained less than 5% of Egypt’s overall yearly zakat estimates of £17b EGY.Footnote95 Despite the state’s attempts appropriate Islamic charity, these figures question the extent to which Bayt al-Zakat has limited regime challengers’ access to zakat donations. Instead, Bayt al-Zakat’s main benefactors suggest it has operated more successfully as an outlet for regime allies and supporters to demonstrate their loyalty. It faces significant obstacles, such as the informal and localized nature of zakat donations, which make it a particularly difficult resource to penetrate. There may be a reluctance on the part of those giving donations to redirect zakat centrally, rather than being utilized locally. Therefore, the statization of zakat would require a complete transformation in behavioural practice for much of Egypt’s population, requiring substantial state capacity for such widespread penetration of civil society.

The resources Bayt al-Zakat has been able to extract have still been used to benefit state projects focused on economic development, reflecting the state’s developmental objectives. Its statutes specify part of its strategy is building a strong economy, through charitable funds for small income-generating development, to reduce unemployment and establish local projects in education and health.Footnote96 In 2015, £20 m EGY financed a joint project between Bayt al-Zakat and the Egyptian Holding Company for Drinking Water, installing home water connections in poor villages in the Sharqiya, Sohag, Asyut and Minya governorates.Footnote97 Also in 2015, Bayt al-Zakat allocated £100 m EGY for treating the Hepatitis C virus, cooperating with the Ministry of Health,Footnote98 while funds were used to build 1,000 social housing units.Footnote99 The zakat funds, appropriated by an ostensibly state-backed body, have therefore contributed to state building efforts and the wider developmental agenda of the Egyptian government, whilst siphoning off funds previously accessed by Islamic associations for their own activities.

Institution-building

By strengthening the components of the state that provide social services, a previous reliance on non-state actors can be compensated for, while cultivating loyalty to the state among its citizens. This section details three components of institution-building contributing to the provision of social services: support from international financial institutions for state welfare; the (attempted) reinvigoration of state ministries engaged in service provision; and an expanded role for the military in social service provision.

Shifting norms among international financial institutions has supported the state’s expanding service role. To secure loans from the IMF, Egypt agreed to cut food and energy subsidies significantly. In the 2012/2013 budget, energy subsidies amounted to £120 billion EGY, with food subsidies at £32.5 billion EGY.Footnote100 The IMF agreed to lend Egypt $12 billion over three years as part of its economic reform programme, enabling increased service provision to compensate for reduced subsidies. In 2015 the IMF mission chief for Egypt, Christopher Jarvis, noted that, “to help the poor weather the reforms, the government is increasing cash transfers and spending on health, education, and infrastructure”.Footnote101 In contrast to its pre-2013 stance, the IMF was now making “explicit recommendations to expand health and education spending and services”.Footnote102 An IMF report stated: “Phasing out fuel subsidies created more room in the budget for better-targeted social spending, as well as more investment in health, education, and public infrastructure”.Footnote103 By the 2014/2015 budget, energy subsidies had dropped to £104.5 billion EGY, falling again to £93 billion EGY and £62 billion EGY the following two years. Spending on health, meanwhile, was at £31.6 billion EGY in 2012/2013, rising to £49 billion EGY by 2015/2016. Education rose from £73 billion EGY to £110 billion EGY in 2015/2016. By the end of the loan period, in the 2018/2019 budget, health spending continued to increase to £98 billion EGY, while education rose to £159 billion EGY.Footnote104

In part, these increases mirror President al-Sisi’s rhetoric on “social justice”.Footnote105 In the 2014 constitution, minimum spending levels for the health and education budgets were set. Over the previous decade, public health expenditures averaged 2% of GDP, one of the lowest among Arab states.Footnote106 In response, the new constitution required the government to commit to global averages, with Article 18 stipulating at least 3% of GDP to health and Article 19 specifying 4% on education. However, as of 2019, as a percentage of GDP, the size of the education sector actually decreased from 3.6% in the 2018 financial year to 2.5% in 2019, with health spending only at 1.6% of GDP in 2018, meaning both sectors fell below constitutional targets. Footnote107 These figures question the extent to which the Egyptian state has been able to reinvigorate its service apparatus.

The World Bank also held that reforms enabling private investment in infrastructure would free up public funds for education, health, and social protection.Footnote108 In 2015, it directly provided funds for social service programmes with $400 million for two cash transfer programmes – Takaful (insurance) and Karama (dignity) – aimed at mitigating the negative impacts of the subsidy reforms on the poorest sectors of Egypt’s population.Footnote109 Takaful provides a basic monthly cash transfer of £325 EGY with support for up to 3 children, while Karama provides elderly citizens above 65 years of age, and citizens with severe disabilities, a monthly pension of £450 EGY. The MOSS uses a targeting method using means testing in geographical regions, to identify areas with the highest poverty levels. However, an impact evaluation study of the programme showed only 20% of the poorest quintile benefitted from the programme’s coverage.Footnote110 This is linked to a poor targeting mechanism in use of household information, resulting in inefficient use of the programmes’ expenditure. While equipped with the material resources to improve conditions for its poorest citizens, the Egyptian state still appears to lack the organizational competency required for its rollout.

Despite IMF and World Bank assistance, Egypt’s poverty rate actually increased by 4.7% over 2017 and 2018 to 32.5% of the population.Footnote111 This was partly due to real public wages decreasing, with an inflation rate at more than 10%, and rising fuel prices during energy subsidy reductions.Footnote112 In 2014, when energy subsidies reduced by £30 billion EGY, energy prices rose by 40%, which included gas, fuel, and electricity for households.Footnote113 Whilst compensatory policies aimed to balance out fiscal changes by providing cash subsidies, the cost of living rose so high that the value of handouts was insufficient. Despite renewed focus on the state’s welfare apparatus, the overall net effect of statist interventions has not produced vastly improved outcomes for Egypt’s poor.

The Egyptian military also played an expanded role in the provision of social services. In December 2016, army trucks distributed 8 million food cartons across governorates at subsidized prices.Footnote114 During Ramadan 2017, millions more subsidized boxes were distributed carrying Armed Forces’ Supply Authority labels.Footnote115 The military has coordinated with state ministries to distribute food and other services to citizens, in 2016 joining with the Ministry of Health to distribute 30 million packages of infant milk at half price to pharmacies.Footnote116 In May 2018, it coordinated with the Ministry of Supply across various governorates during Ramadan to provide 2.7 million food cartons.

The military’s increased role also developed in food distribution networks. The National Service Products Organisation – established under Sadat in the 1970s to achieve self-sufficiency for the military – manufactures military and civilian products. In 2016, its sale of food to civilian markets increased exponentially, providing 250 tons of meat and commodities at reduced prices through 700 outlets.Footnote117 In 2017, it provided local markets with 300,000 tons of meat, poultry, and cooking oil, both through its own outlets and those of the Ministry of Supply.Footnote118 In January 2019, 600,000 food packages were given as a religious donation to the residents of 18 “development communities” under construction by the Armed Forces’ Engineering Authority in North and South Sinai.Footnote119 Mirroring the militarization of the ruling regime, the Egyptian military has become an important actor in social service delivery under al-Sisi.

Reconstituted authoritarianism

outlines the model of reconstituted authoritarianism resulting from the four strategies identified above from the Egyptian case. Charles Tilly’s theory on “war making and state making” is introduced to conceptualize these strategies, both those aimed at neutralizing non-state actors, and those utilizing state institutions to increase the state’s service provision role. The intervening variable of state capacity determines whether the dependent variable of reconstituted authoritarianism will be strong or weak.

Tilly’s theory of “war making and state making” is useful for understanding the shift from “indirect” to “direct” rule, and distinguishing between strategies aimed at “neutralising” the organizational autonomy of non-state actors, and those which forestall the need for non-state service provision. Tilly argues that through “state-making” and “extraction”, fledgling states could neutralize domestic opponents.Footnote120 For Tilly, “a state that successfully eradicates its internal rivals strengthens its ability to extract resources”,Footnote121 which are then used for state building to centralize the state apparatus. States establish authority by transitioning from “indirect” to “direct” rule. Prior to the French Revolution, most European governments relied on “indirect” rule through local magnates. But as collaborators rather than officials, they remained “potential rivals, possible allies of a rebellious people”.Footnote122 Outsourcing service provision to non-state actors presents a similar risk for contemporary regimes. Tilly argues that states reduced their reliance on indirect forms of rule by extending their official presence in local communities through state agencies rather than local patrons.Footnote123 For reconstituted authoritarian regimes, neutralizing local rivals necessitates the enforcement of “direct” controls over service provision.

Nationalization and corporatization represent strategies to neutralize non-state actors. The Egyptian case demonstrates that the clearest form of “direct” control occurs when a state incorporates existing associations into its own infrastructure through nationalization. Although regimes can simply shut down the operations of civil society organizations deemed to pose a threat,Footnote124 doing so could be problematic when their very existence is partly a result of state strategy to avoid social unrest. Nationalization enables services to continue, while the provider shifts from the private sector to the state. This practice can be observed in other authoritarian regimes such as China, where NGOs have been vulnerable to government takeover through absorption within state institutions.Footnote125 Nationalizing service providers establishes direct control through the state apparatus to eliminate rivals. Corporatism, meanwhile, represents an indirect strategy of co-optation that can supplement direct controls such as nationalization. Despite formal independence, incorporation turns associations into an extension of the state’s governance, providing a cost-effective means of control.Footnote126 This strategy is prevalent in authoritarian regimes in Muslim-majority states in sub-Saharan Africa,Footnote127 East Asia,Footnote128 and the Middle East.Footnote129

Extraction and institution-building represent distinct but related dimensions of state making. Extraction, including taxes or foreign aid, provides material resources for regimes to maintain socio-economic stability.Footnote130 The potential of Islamic charity as a revenue stream was already recognized in several Muslim-majority states. In Malaysia and Pakistan, states centralized its collection and distribution.Footnote131 State oversight of zakat is commonplace in the Gulf, with increased “statization” in Jordan and the Palestinian West Bank.Footnote132 Extraction of zakat not only appropriates the resource base of Islamic rivals, but provides a resource for the state’s own priorities. Institution-building is an extension of the state’s own infrastructure, including service provision. Through domination of service provision, states can “disrupt alternative social-service networks”, depriving non-state actors from “connecting and gaining credibility with the masses”.Footnote133 State-provided services can “cultivate dependence” through citizen loyalty, helping sustain authoritarian rule.Footnote134 In the Gulf, social safety nets negated the need for services to be “outsourced” to non-state actors,Footnote135 while Indonesia’s developmental focus removed service provision as a means of Islamist mobilization.Footnote136 Robust state provision may explain divergent outcomes during the Arab Spring, with wealthier oil-producing Gulf monarchies able to increase “benefits in return for obedience”, unlike post-populist republics like Egypt and Syria.Footnote137 Reconstituting authoritarian regimes, like al-Sisi’s Egypt, engage in institution-building to reinvigorate their own service apparatus as a means of forestalling challengers and insulating against future socio-economic disruption.

The Egyptian case shows that despite pursuing these strategies, their efficacy is tempered by the state’s capacity to realize its goals. State capacity operates as an intervening variable, determining whether authoritarian reconstitution is strong or weak. Comprehensive state-led strategies for change depend on “the overall capacity of a state to realise transformative goals across multiple spheres”.Footnote138 High levels of infrastructural capacity are associated with authoritarian durability.Footnote139 State capacities can be separated into coercive, extractive, and administrative, the latter two pertinent for Egypt’s reconstituted authoritarianism.Footnote140 Extractive capacity is measured by collecting data on government revenue collections,Footnote141 or the proportion of zakat donations retrieved. This article shows that in Egypt’s case, the state’s capacity is limited. Administrative capacity relates to organizational capabilities, including the delivery of public services, with material resources providing the means to enact policy.Footnote142 Effective organization includes technical competence and coordination across the state’s territory and social groupings.Footnote143 This article demonstrates Egypt’s ability to increase material resources for institution-building, but its organizational incompetence undermines its reinvigoration of state services. Therefore, the long-term durability of reconstituted authoritarianism, particularly in resource-poor states such as Egypt, is consequently contingent on having sufficient state capacity to consolidate authoritarian rule.

Conclusion

Egypt’s reconstituted authoritarianism under al-Sisi aims to neutralize the social capital accrued by Islamic associations’ service provision, and the benefits this produced for the government’s Islamist opponent, the Muslim Brotherhood. Through nationalization, the Egyptian state enforced “direct” controls over Islamic non-state actors engaged in service provision. However, the select number targeted out of a much greater total indicates a more limited effort to neutralize political challengers, rather than a wholesale takeover of the Islamic social sector. This suggests that the Egyptian state may still tolerate Islamic non-state actors engaged in service provision – by necessity if not preference – but will readily deploy statist measures against those perceived as a political threat. Attempts to occupy a greater role in service provision by engaging in extraction and institution-building may generate increasing levels of legitimacy, while reducing the need to rely on non-state actors engaged in service provision. However, this is a long-term process which requires ongoing monitoring. Indications from this article suggest that the Egyptian state’s renewed emphasis on state welfarism is limited by organizational capacity, coupled with a generally bleak outlook for its economy. Attempts to statize the collection and distribution of zakat donations indicate a potential growth area to generate resources for institution-building. Yet rhetoric over state control is belied by relatively modest zakat levels extracted by Bayt al-Zakat. As with nationalization, these strategies appear better geared towards forestalling rivals rather than fundamentally reshaping Islamic charity more broadly.

This article contributes to the authoritarian upgrading literature by arguing that during periods of authoritarian transition, regimes may revise previous arrangements where non-state provision of social services served to stabilize regimes socio-economically. The Egyptian case suggests that a change in orientation for the role of service provision is seen as a legitimating factor; and that a move from “indirect” co-optation towards an enhanced “direct” role for the state is in order to maintain power. To make this argument, the article developed the model of reconstituted authoritarianism, with the four strategies of nationalization, corporatization, extraction, and institution-building representing the shift from “indirect” to “direct” relations with actors engaged in welfare provision. This change reflects Tilly’s conceptualization of state formation, whereby the state apparatus is utilized to neutralize domestic rivals, in this case, through extraction and institution-building. The article also makes several contributions to debates on post-2013 Egypt under al-Sisi. It offers a conceptualization of the structure of authoritarianism in Egypt, going beyond the much-highlighted repressive dimension, by focusing on state-society relations and the often-overlooked role of service provision during political transition. In addition, its findings on an enhanced role for the state apparatus adds to a growing literature on the statist dimensions of al-Sisi’s rule. Finally, it offers a significant empirical contribution to the literature on the repression of the Brotherhood’s social mobilization, by systematically charting the outcome of Islamic associations seized after the coup.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Una McGahern and Valentina Feklyunina for their comments on an earlier draft of this paper. I also wish to express my gratitude to Steven Brooke, Nathan Brown, Marc Lynch, and all the participants in the autumn 2020 POMEPS Virtual Research Workshop, for their helpful feedback and encouragement. The suggestions from anonymous reviewers were also invaluable in sharpening the contribution of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No financial interest or benefit that has arisen from the direct applications of my research.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Neil Russell

Neil Russell is Lecturer in Politics at Glasgow Caledonian University, having previously taught at Newcastle University. His research focuses on state regulation of Islamic social and religious institutions in Egypt and the Middle East more widely. He has published chapters on Islamist politics and Salafism in volumes by Routledge and Edinburgh University Press and is currently working on a book project based on his PhD dissertation from the University of Edinburgh.

Notes

1 Harrigan and el-Said, Economic Liberalisation.

2 Heydemann, “Upgrading Authoritarianism”.

3 Pierret and Selvik, “Limits of “Authoritarian Upgrading””.

4 Heydemann, “Mass Politics”.

5 Ibid., 15.

6 al-Sherbini, “Islamist Charities”.

7 Abdelrahman, Civil Society Exposed; Atia, Building a House; Clark, Islam, Charity; Wickham, Mobilizing Islam; Wiktorowicz, Management of Islamic.

8 al-Anani, “Rethinking the Repression-Dissent”; Ardovini and Biagini, “Assessing the Egyptian Muslim”.

9 Fahmi, “The Egyptian State”.

10 Herrold, Delta Democracy.

11 Brooke, “The Muslim Brotherhood’s Social”.

12 Gerschewski, “Three Pillars of Stability”.

13 Abdelrahman, “Policing Neoliberalism”; Pratt and Rezk, “Securitizing the Muslim Brotherhood”.

14 Rutherford, “Egypt’s New Authoritarianism”.

15 Grimm and Harders, “Unpacking the Effects,” 2.

16 Gobel, “Authoritarian Consolidation”.

17 Gerschewski, “The Three Pillars of,” 18.

18 Von-Soest and Grauvogel, “Identity, Procedures and Performance”.

19 Yefet and Lavie, “Legitimation in Post-Revolutionary”.

20 Wessel, “The “Third Hand’,” 344.

21 Bano and Benadi, “Regulating Religious Authority”.

22 Gerschewski, “Three Pillars of Stability,” 22.

23 Levitsky and Way, “Beyond Patronage: Violent Struggle”.

24 Cammett and Issar, “Bricks and Mortar Clientelism”.

25 Pioppi.

26 Sika, “Repression, Cooptation”.

27 El-Sherif, “Egypt’s Salafists”.

28 Pierret “The State Management,” 84.

29 Pierret, 85.

30 Rutherford, Egypt after Mubarak, 145.

31 Khalil and Dill, “Negotiating Statist Neoliberalism”.

32 Linn and Crane-Linn. “Egypt’s War”.

33 Singer, Charity in Islamic Societies, 177.

34 Kawamura, “Social Welfare”.

35 Gallagher, Egypt’s Other Wars, 169–70.

36 Berger, Islam in Egypt, 117–8.

37 Gallagher, Egypt’s Other Wars, 171.

38 Bromley, Rethinking Middle East Politics, 131.

39 Atia, Building a House.

40 Berger, 94.

41 Menza, Patronage Politics, 73.

42 Gauvain, Salafi Ritual Purity, 37.

43 Waterbury, The Egypt of Nasser, 223.

44 Hinnebusch, Egyptian Politics, 272.

45 Ibid., 272.

46 Al-Arian, Answering the Call, 54.

47 Zahid, The Muslim Brotherhood, 40.

48 Harrigan and El-Said, Economic Liberalisation, 78.

49 Hinnebusch, “The Politics of Economic,” 161.

50 Ibrahim, An Assessment of Grass, 62.

51 Harrigan and El-Said, Economic Liberalisation.

52 Herrold, “Giving in Egypt,” 307–15.

53 Ibrahim, An Assessment of Grassroots, 67.

54 Pioppi, “Privatization of Social Services,” 135.

55 Abdelrahman, Civil Society Exposed, 131.

56 Brooke, Winning Hearts and Votes, 124.

57 Ibid., 121.

58 Ibid., 142.

59 Ibid., 124.

60 BBC News, “Egypt Bans Brotherhood”.

61 The newspaper al-Masry al-Youm published a list of all associations seized by the government which made clear the Islamic basis of each association. The list included Brotherhood affiliates such as the Islamic Education Association, Islamic Medical Association, Islamic Relief Committee, and branches of well-known nationally networked Islamic charities such as Ansar al-Sunna and al-Gam‘iyya al-Shar‘iyya.

62 Qandil, “al-taḥawulāt”.

63 Qandil.

64 al-Ahram, “waqf tajmīd”.

65 Rahim, “ḥal 46 jam“iyya”.

66 al-Masry al-Yawm, ‘al-taḍāmun: ḥal 112.

67 al-Masry al-Yawm, “wazīra al-taḍāmun”.

68 Ikhwan Web, “Heshmat Condemns Coup”.

69 Ibid.

70 Warren, “Cleansing the Nation”.

71 Daily News Egypt, “Market Unaffected”.

72 Ahram Online, “Egypt Seizes Several Freedom”.

73 Ahram Online, “Egypt Seizes 5 Muslim”.

74 Daily News Egypt, “Government Seizes Seoudi Supermarkets”.

75 Alabass, “Seoudi and Zad”.

76 Williamson, Varieties of Corporatism.

77 Williamson, 11.

78 Ayubi, “Over-Stating”.

79 Rahim.

80 Qenaoui, “ḥal 25 jam“iyya”.

81 Ali, ““al-jam‘iyya al-shar‘iyya””.

82 Sullivan and Abed-Kotob, Islam in Contemporary Egypt, 34.

83 Bianchi, Unruly Corporatism, 193.

84 Wickham, Mobilizing Islam, 100.

85 al-Masry al-Yawm, “al-awqāf tu’akid”.

86 Refaat, “al-awqāf tashkul”.

87 Amwal al-Ghad, “Egypt Zakat House”.

88 Buheiry, “majlis ’umnā’”.

89 Ali, “shaykh al-’azhar”.

90 Buheiry, ““al-’azhar””.

91 Gamal, “7 ṭuruq l-taḥṣīl”.

92 el-Hoty, “’amīn ‘ām bayt al-zakāa”.

93 Ali, “al-baḥrayn tatabr‘a”.

94 Mousa and al-Ghareeb, “ṣafwat al-naḥās”.

95 Ibid.

96 Ali, “shaykh al-’azhar”.

97 Hassan, “brutūkūl bayn”.

98 el-Hoty, “’amīn ‘ām bayt al-zakāa”.

99 Ali, ““bayt al-zakāa wa al-ṣadqāt””.

100 Aggour, “FY 2014/2015 State Budget”.

101 IMF “Egypt: Steadfast Reforms Key”.

102 Momani and Lanz, “Shifting IMF Policies”.

103 IMF “Egypt: A Path Forward”.

104 Ahram Online “Egypt Implements 2018/19 Budget”.

105 Ezzat, “The Dream That Won’t”.

106 “BTI 2016: Egypt Country Report”.

107 World Bank, “Egypt Economic Monitor”.

108 World Bank, “Egypt: Shifting Public Funds”.

109 World Bank, “The Story of Takaful”.

110 Hussien and Park, “Measurement of Multidimensional Poverty,” 38.

111 Kassab, “Austerity Measures a Major”.

112 Mossallam, “The IMF”.

113 Ibid.

114 Aswat Masriya, “al-jaysh: bad’ tawzī‘”.

115 Abul-Magd, “Feeding Social Stability”.

116 Kandil, “Police, Army Distribute Food”.

117 Sayigh, “Owners of the Republic,” 275.

118 Ibid., 275.

119 Ibid., 252.

120 Tilly, “War Making”.

121 Ibid., 181.

122 Ibid., 174.

123 Ibid., 175.

124 Toepler et al., “The Changing Space,” 654.

125 Hasmath and Hsu, “Isomorphic Pressures”.

126 Toepler et al., 657.

127 Elischer, “Autocratic Legacies”.

128 Liddle, “The Islamic Turn”.

129 Wiktorowicz, The Management of Islamic, 34.

130 Slater and Fenner, “State Power and Staying,” 21.

131 Tripp, Islam and the Moral, 125.

132 Challand, “Comparative Perspective”.

133 Slater and Fenner, 23.

134 Ibid., 19.

135 Freer, Rentier Islamism.

136 Brooke, “Islamist Organizations”.

137 Mann, “The Infrastructural Powers”.

138 Skocpol, “Bringing the State Back,” 17.

139 Fortin-Rittberger, “Exploring the Relationship”.

140 Hanson and Sigman, “Leviathan’s Latent Dimensions”, 1498.

141 Ibid, 1499.

142 Ibid, 1501.

143 Ibid, 1499.

Bibliography

- Abdelrahman, Maha. Civil Society Exposed: The Politics of NGOs in Egypt. London: I.B. Tauris, 2004.

- Abdelrahman, Maha. “Policing Neoliberalism in Egypt: The Continuing Rise of the ‘Securocratic’ State.” Third World Quarterly 38, no. 1 (2017): 185–202.

- Abul-Magd, Zeinab. “Feeding Social Stability in Egypt.” Carnegie Endowment (2017). https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/71198.

- Aggour, Sara. “FY 2014/2015 State Budget Announced.” Daily News Egypt, 26 May 2014. https://wwww.dailynewssegypt.com/2014/05/26/fy-20142015-state-budget-announced-analysts-weight/.

- al-Ahram. “waqf tajmīd ‘amwāl al-jam‘iyyat al-’ahliyya’.” 27 December 2013.

- Ahram Online. “Egypt Implements 2018/19 Budget.” 1 July 2018. http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/3/12/305965/Business/Economy/Egypt-implements–budget-with-more-expenditures-on.aspx.

- Ahram Online. “Egypt Seizes 5 Muslim Brotherhood Affiliated Publishing Houses.” 1 September 2015. http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/0/139443/Egypt/0/Egypt-seizes–Muslim-Brotherhood-affiliated-publis.aspx.

- Ahram Online. “Egypt Seizes Several Freedom and Justice Party Offices.” 16 November 2015. http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/64/168851/Egypt/Politics-/Egypt-seizes-several-Freedom-and-Justice-Party-off.aspx.

- Alabass, Bassem. “Seoudi and Zad to Be Re-Opened under Egyptian Government’s Control.” Ahram Online, 16 June 2014. http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/3/12/103882/Business/Economy/Seoudi-and-Zad-to-be-reopened-under-Egyptian-gover.aspx.

- Albertus, Michael, and Victor Menaldo. “Coercive Capacity and the Prospects for Democratization.” Comparative Politics 44, no. 2 (2012): 151–169.

- Ali, Loay. “al-baḥrayn tatabr‘a b-16 milīūn junayh l-“bayt al-zakāa”.” al-Yawm al-Saba’a, 6 October 2015. https://bit.ly/2ZtGRNW.

- Ali, Loay. ““bayt al-zakāa wa al- ṣadqāt”: musā“adāt shahriyya l-’akthar min 81 “alf mustaḥaq li-l-zakāa.” al-Yawm al-Saba’a, 27 December 2018. https://bit.ly/2HmjpaO.

- Ali, Loay. ““al-jam‘iyya al-shar‘iyya”: ḥaṣalnā ‘alā tarkhīṣ min “al-taḍāmun”.” al-Yawm al-Saba’a, 1 April 2015. https://bit.ly/2NJam9z.

- Ali, Loay. “shaykh al-’azhar yitarās ijtimā“ majlis “amnā’ bayt al-zakāa.” al-Yawm al-Saba’a, 18 November 2014.

- Amwal al-Ghad. “Egypt Zakat House to Promote Transparency.” 10 July 2014. https://www.masress.com/en/amwalalghaden/28332.

- Al-Anani, Khalil. “Rethinking the Repression-Dissent Nexus: Assessing Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood’s Response to Repression Since the Coup of 2013.” Democratization 26, no. 8 (2019): 1329–1341.

- Ardovini, Lucia, and Erika Biagini. “Assessing the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood After the 2013 Coup: Tracing Trajectories of Continuity and Change.” Middle East Law and Governance 13, no. 2 (2021): 125–129.

- al-Arian, Abdullah. Answering the Call: Popular Islamic Activism in Sadat’s Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Aswat Masriya. “al-jaysh: bad’ tawzī‘ milāyīn kartūna.” 11 January 2016. http://www.aswatmasriya.com/news/details/69426.

- Atia, Mona. Building a House in Heaven: Pious Neoliberalism and Islamic Charity in Egypt. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

- Ayubi, Nazih N. Over-Stating the Arab State: Politics and Society in the Middle East. London: Tauris, 1995.

- Bano, Masooda, and Hanane Benadi. “Regulating Religious Authority for Political Gains: Al-Sisi’s Manipulation of al-Azhar in Egypt.” Third World Quarterly 39, no. 8 (2018): 1604–1621.

- BBC News. “Egypt Bans Brotherhood “Activities”.” 23 September 2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-24208933.

- Berger, Morroe. Islam in Egypt Today. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1970.

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. “BTI 2016: Egypt Country Report.” 2016. https://www.bti-project.org/fileadmin/files/BTI/Downloads/Reports/2016/pdf/BTI_2016_Egypt.pdf.

- Bianchi, Robert. Unruly Corporatism: Associational Life in Twentieth-Century Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Bromley, Simon. Rethinking Middle East Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1994.

- Brooke, Steven. “The Muslim Brotherhood’s Social Outreach after the Egyptian Coup.” Brookings Institute, August 2015. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Egypt_Brooke-FINALE.pdf.

- Brooke, Steven. “Islamist Organizations and the Provision of Social Services.” In The Oxford Handbook of Politics in Muslim Societies, edited by Melani Cammett, and Pauline Jones. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Brooke, Steven. Winning Hearts and Votes: Social Services and the Islamist Political Advantage. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2019.

- Buheiry, Ahmed. ““al-’azhar” yu“lin “arqām ḥisāb bayt al-zakāa.” al-Masry al-Yawm, 18 November 2014. https://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/577501.

- Buheiry, Ahmed. “majlis ‘umnā’ bayt al-zakāa yu‘qad ijtimā‘an b-r’āsat shaykh al-’azhar.” al-Masry al-Yawm, 10 November 2015. https://www.almasryalyoum.com/news/details/841334.

- Cammett, Melani, and Sukriti Issar. “Bricks and Mortar Clientelism: Sectarianism and the Logics of Welfare Allocation in Lebanon.” World Politics 62, no. 3 (2010): 381–421.

- Cammett, Melani, and Pauline Jones-Luong. “Is There an Islamist Political Advantage?” Annual Review of Political Science 17, no. 1 (2014): 187–206.

- Challand, Benoit. “A Nahḍa of Charitable Organizations? Health Service Provision and the Politics of Aid in Palestine.” International Journal Middle East Studies 40, no. 2 (2008): 227–247.

- Challand, Benoit. “Comparative Perspective on the Growth and Legal Transformations of Arab (Islamic) Charities.” In Charities in the Non-Western World, edited by Justin Pierce, and Rajeswary Brown, 293–310. Abingdon: Routledge, 2013.

- Clark, Janine. Islam, Charity, and Activism: Middle-Class Networks and Social Welfare in Egypt, Jordan, and Yemen. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.

- Daily News Egypt. “Government Seizes Seoudi Supermarkets.” 15 June 2014. https://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2014/06/15/government-seizes-seoudi-supermarkets-among-muslim-brotherhood-assets/.

- Daily News Egypt. “Market Unaffected by Confiscated Muslim Brotherhood Assets.” 8 September 2016. https://www.dailynewsegypt.com/2015/09/08/market-unaffected-by-confiscated-muslim-brotherhood-assets-economic-expert/.

- Elischer, Sebastian. “Autocratic Legacies and State Management of Islamic Activism in Niger.” African Affairs 114, no. 457 (2015): 577–597.

- Evans, Peter, Rueschemeyer, Dietrich, and Skocpol, Theda, eds. Bringing the State Back In. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- Ezzat, Dina. “The Dream That Won’t Quit - a Nasserite Welfare State.” Ahram Online, 29 September 2015. http://english.ahram.org.eg/NewsContent/1/151/149650/Egypt/Features/The-dream-that-wont-quit–a-Nasserite-welfare-stat.aspx.

- Fahmi, Georges. “The Egyptian State and the Religious Sphere.” Carnegie Middle East Center, 18 September 2014. https://carnegie-mec.org/2014/09/18/egyptian-state-and-religious-sphere-pub-56619.

- Fortin-Rittberger, Jessica. “Exploring the Relationship Between Infrastructural and Coercive State Capacity.” Democratization 21, no. 7 (2014): 1244–1264.

- Freer, Courtney. Rentier Islamism: The Influence of the Muslim Brotherhood in Gulf Monarchies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Gamal, Mustafa. “7 ṭuruq l-taḥṣīl al-zakāa fī al-’azhar al-sharīf.” Vetogate, 15 June 2017. https://www.vetogate.com/2752752.

- Gauvain, Richard. Salafi Ritual Purity: In the Presence of God. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Gallagher, Nancy. Egypt’s Other Wars: Epidemics and the Politics of Public Health. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1990.

- Gerschewski, Johannes. “The Three Pillars of Stability: Legitimation, Repression, and Co-Optation in Autocratic Regimes.” Democratization 20, no. 1 (2013): 13–38.

- Göbel, Christian. “Authoritarian Consolidation.” European Political Science 10, no. 2 (2011): 176–190.

- Grimm, Jannis, and Cilja Harders. “Unpacking the Effects of Repression: The Evolution of Islamist Repertoires of Contention in Egypt After the Fall of President Morsi.” Social Movement Studies 17, no. 1 (2018): 1–18.

- Hanson, Jonathan, and Rachel Sigman. “Leviathan’s Latent Dimensions: Measuring State Capacity for Comparative Political Research.” The Journal of Politics 83, no. 4 (2021): 1495–1510.

- Harrigan, Jane, and Hamed El-Said. Economic Liberalisation, Social Capital and Islamic Welfare Provision. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

- Hasmath, Reza, and Jennifer Hsu. “Isomorphic Pressures, Epistemic Communities and State–NGO Collaboration in China.” China Quarterly 220 (2014): 936–954.

- Hassan, Ahmed. “brutūkūl bayn “al-qābḍa li-l-mayāh” wa ṣundūq bayt al-zakāa.” al-Yawm al-Saba’a, 20 October 2015. https://bit.ly/2ZiyyQH.

- Herrold, Catherine. Delta Democracy: Pathways to Incremental Civic Revolution in Egypt and Beyond. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Herrold, Catherine. “Giving in Egypt: Evolving Charitable Traditions in a Changing Political Economy.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Global Philanthropy, 307–315. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

- Heydemann, Steven. “Mass Politics and the Future of Authoritarian Governance in the Arab World.” POMEPS Studies (2015).

- Heydemann, Steven. Upgrading Authoritarianism in the Arab World. Brookings Institute, 2007.

- Hinnebusch, Raymond. Egyptian Politics Under Sadat: The Post-Populist Development of an Authoritarian-Modernizing State. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1988.

- Hinnebusch, Raymond. “The Politics of Economic Reform in Egypt.” Third World Quarterly 14, no. 1 (1993): 159–171.

- El-Hoty, Hani. “’amīn ‘ām bayt al-zakāa: 350 milīūn junayh al-mīzāniyya.” al-Yawm al-Saba’a, 28 October 2015. https://bit.ly/2KZTg2B.

- Hussien, Shaimaa, and Bokyeong Park. “Measurement of Multidimensional Poverty in Egypt.” Journal of International and Area Studies 26, no. 2 (2019): 35–54.

- Ibrahim, Saad. An Assessment of Grass Roots Participation in the Development of Egypt. Cairo: AUC Press, 1997.

- Ikhwan Web. “Heshmat Condemns Coup Takeover of Islamic Association Hospitals.” https://www.ikhwanweb.com/article.php?id=31967.

- IMF. “Egypt: A Path Forward for Economic Prosperity.” 24 July 2019. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/07/24/na072419-egypt-a-path-forward-for-economic-prosperity.

- IMF. “Egypt: Steadfast Reforms Key for Economic Stability.” 11 February 2015. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2015/CAR021115A.htm.

- Kamrava, Mehran, ed. Beyond the Arab Spring: The Evolving Ruling Bargain in the Middle East. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Kassab, Beesan. “Austerity Measures a Major Cause of Poverty Increase.” Mada Masr, 4 September 2019. https://madamasr.com/en/2019/09/04/feature/economy/austerity-measures-a-major-cause-of-poverty-increase-statistics-agency-advisor-says/.

- Kandil, Amr. “Police, Army Distribute Food Cartons to Needy People.” Egypt Today, 17 May 2018. http://www.egypttoday.com/Article/2/50261/Police-army-distribute-food-cartons-to-needy-people.

- Kawamura, Yusuke. “Social Welfare under Authoritarian Rule: Change and Path Dependence in the Social Welfare System in Mubarak’s Egypt.” Doctoral thesis, Durham University, 2016.

- Khalil, Heba, and Brian Dill. “Negotiating Statist Neoliberalism: The Political Economy of Post-Revolution Egypt.” Review of African Political Economy 45, no. 158 (2018): 574–591.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan Way. “Beyond Patronage: Violent Struggle, Ruling Party Cohesion, and Authoritarian Durability.” Perspectives on Politics 10, no. 4 (2012): 869–889.

- Liddle, William. “The Islamic Turn in Indonesia.” The Journal of Asian Studies 55, no. 3 (1996): 613–634.

- Linn, Nicholas, and Emily Crane-Linn. “Egypt’s War on Charity.” Foreign Policy, 29 January 2015. https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/01/29/egypts-war-on-charity-morsi-muslim-brotherhood/.

- Lorch, Jasmin, and Bettina Bunk. “Using Civil Society as an Authoritarian Legitimation Strategy: Algeria and Mozambique in Comparative Perspective.” Democratization 24, no. 6 (2017): 987–1005.

- Mann, Michael. “The Infrastructural Powers of Authoritarian States in the “Arab Spring”.” 2014. https://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/soc/faculty/mann/Morocco.pdf.

- Masoud, Tarek. Counting Islam: Religion, Class, And Elections In Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- al-Masry al-Yawm. “al-awqāf tu’akid ahmīa al-jam‘iyyat al-khayr‘iyya.” 3 January 2014.

- al-Masry al-Yawm. “al-taḍāmun: ḥal 112 jam‘iyya ahlīya tum ishārha bayn 2011 wa 2012.” 1 March 2015.

- al-Masry al-Yawm. “wazīra al-taḍāmun: ‘amwāl jam‘iyyāt “al-ikhwān” al-manḥalla qalīla jiddan.” 21 April 2016.

- Menza, Mohamed Fahmy. Patronage Politics in Egypt: The National Democratic Party and Muslim Brotherhood in Cairo. New York, NY: Routledge, 2012.

- Momani, Bessma, and Dustyn Lanz. “Shifting IMF Policies Since the Arab Uprisings.” Center for International Governance. https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/cigi_pb_34_0.pdf.

- Mossallam, Mohammed. “The IMF in the Arab World: Lessons Unlearnt.” Bretton Woods Project, November 2015. https://bit.ly/3eXQfPY.

- Mousa, Ali, and Muhammad al-Ghareeb. “ṣafwat al-naḥās: 60 milīyār junayh qīmat ‘amwāl al-zakāa.” al-Bawabh, 21 May 2019. https://www.albawabhnews.com/3604942.

- Norton, Augustus, ed. Civil Society in the Middle East. Leiden: Brill, 1995.

- Pierret, Thomas. “The State Management of Religion in Syria: The End of “Indirect Rule”?” In Middle East Authoritarianisms, edited by Steven Heydemann, and Reinoud Leenders, 595–614. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2013.

- Pierret, Thomas, and Kjetil Selvik. “Limits of “Authoritarian Upgrading” in Syria: Private Welfare, Islamic Charities, and the Rise of the Zayd Movement.” International Journal Middle East Studies 41, no. 4 (2009): 129–142.

- Pioppi, Daniela. “Privatization of Social Services as a Regime Strategy: The Revival of Islamic Endowments (Awqaf) in Egypt.” In Debating Arab Authoritarianism, edited by Oliver Schlumberger, 239–256. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

- Pratt, Nicola, and Dina Rezk. “Securitizing the Muslim Brotherhood: State Violence and Authoritarianism in Egypt After the Arab Spring.” Security Dialogue 50, no. 3 (2019): 239–256.

- Qandil, Amany. “al-taḥawulāt fī al-buniyya al-waẓīfa.” Arab Center for Research, 27 December 2014. http://www.acrseg.org/30498.

- Qenaoui, Ayman. “ḥal 25 jam‘iyya tābi‘a li-l-ikhwān al-muslimīn.” al-Sharq, 20 April 2016. https://bit.ly/2ROsJbG.

- Rahim, Sayyid. “ḥal 46 jam‘iyya khayriyya bi-l-manūfiyya.” al-Araby al-Jadid, 1 September 2015. https://bit.ly/2Nqbv5T.

- Refaat, Ismail. “al-awqāf tashkul ghurfa l-murāqiba al-a‘tikāf.” al-Yawm al-Saba’a, 2 July 2015.

- Rutherford, Bruce K. “Egypt’s New Authoritarianism Under Sisi.” Middle East Journal 72, no. 2 (2018): 185–208.

- Sayigh, Yezid. “Owners of the Republic: An Anatomy of Egypt’s Military Economy.” Carnegie Middle East Center, 2019. https://carnegieendowment.org/files/Sayigh-Egypt_full_final2.pdf.

- Al-Sherbini, Ramadan. “Islamist Charities Targeted in Egypt.” Gulf News, 27 December 2013. http://gulfnews.com/news/mena/egypt/islamist-charities-targeted-in-egypt-1.1271285.

- Sika, Nadine. “Repression, Cooptation, and Movement Fragmentation in Authoritarian Regimes: Evidence from the Youth Movement in Egypt.” Political Studies 67, no. 3 (2019): 676–692.

- Singer, Amy. Charity in Islamic Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Slater, Dan, and Sofia Fenner. “State Power and Staying Power: Infrastructural Mechanisms and Authoritarian Durability.” Journal of International Affairs 65, no. 1 (2011): 15–29.

- Von-Soest, Christian, and Julia Grauvogel. “Identity, Procedures and Performance: How Authoritarian Regimes Legitimize Their Rule.” Contemporary Politics 23, no. 3 (2017): 287–305.

- Sullivan, Denis, and Sana Abed-Kotob. Islam in Contemporary Egypt: Civil Society vs the State. London: Lynne Rienner, 1999.

- Tilly, Charles. “War Making and State Making as Organized Crime.” In Bringing the State Back In, edited by Peter B. Evans, Dietrich Rueschemeyer, and Theda Skocpol, 169–191. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- Toepler, Stefan, Annette Zimmer, Christian Fröhlich, and Katharina Obuch. “The Changing Space for NGOs: Civil Society in Authoritarian and Hybrid Regimes.” Voluntas 31 (2020): 649–662.

- Tripp, Charles. Islam and the Moral Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Warren, David. “Cleansing the Nation of the “Dogs of Hell”: ʿAli Jumʿa’s Nationalist Legal Reasoning in Support of the 2013 Egyptian Coup.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 49, no. 3 (2017): 457–477.

- Waterbury, John. The Egypt of Nasser and Sadat: The Political Economy of two Regimes. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Wessel, Sarah. “The ‘Third Hand’ in Egypt.” Middle East Law and Governance 10, no. 3 (2018): 341–374.

- Wickham, Carrie. Mobilizing Islam: Religion, Activism, and Political Change in Egypt. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002.

- Wiktorowicz, Quintan. The Management of Islamic Activism: Salafis, the Muslim Brotherhood, and State Power in Jordan. New York: SUNY Press, 2000.

- Williamson, Peter. Varieties of Corporatism: A Conceptual Discussion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

- World Bank. “A Roadmap to Achieve Social Justice in Health Care in Egypt.” January 2015. https://bit.ly/2oHEOVF.

- World Bank. “Egypt Economic Monitor: From Floating to Thriving.” July 2019. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/260061563202299626/pdf/Egypt-Economic-Monitor-From-Floating-to-Thriving-Taking-Egypts-Exports-to-New-Levels.pdf.

- World Bank. “Egypt: Shifting Public Funds from Infrastructure to Investing in People.” 11 December 2018. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/12/11/egypt-shifting-public-funds-from-infrastructure-to-investing-in-people.

- World Bank. “The Story of Takaful and Karama Cash Transfer Program.” 15 November 2018. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/11/15/the-story-of-takaful-and-karama-cash-transfer-program.

- Yefet, Bosmat, and Limor Lavie. “Legitimation in Post-Revolutionary Egypt: Al-Sisi and the Renewal of Authoritarianism.” Digest of Middle East Studies 30, no. 3 (2021): 170–185.

- Yom, Sean L. “Civil Society and Democratization in the Arab World.” Middle East Review of International Affairs 9, no. 4 (2005): 14–33.

- Zahid, Mohammed. The Muslim Brotherhood and Egypt’s Succession Crisis: The Politics of Liberalisation and Reform in the Middle East. London: I.B. Tauris, 2010.