?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

How does electoral competition shape parties’ use of clientelist strategies during elections? In this article, we present a theoretical framework which suggests that in contexts where electoral clientelism is present but not ubiquitous, clientelist strategies take a distinctive form by being more considered and rationally targeted at individuals and areas that maximize the value of the transaction for the clientelist party. Using individual-level survey data collected in the aftermath of the South African municipal elections of 2016, we find considerable evidence to suggest that electoral competition moderates the relationship between several individual and municipal level variables and individuals’ exposure to clientelist campaigns. Our results also demonstrate how the subtleties of targeting strategies differ between dominant and opposition parties depending on the level of competitiveness. These findings suggest the presence of a rational political economy of clientelism where parties carefully tailor their clientelist strategies to suit the local context.

Introduction

Electoral competition is a cornerstone of democracy. Competitive elections grant opposition parties the opportunity to displace incumbents, and is generally associated with “good governance” and a range of desirable policy outcomes, such as increased education spending,Footnote1 higher life expectancy,Footnote2 less corruption,Footnote3 more public goods provision,Footnote4 and higher levels of economic growth.Footnote5 Yet, electoral competition may also have drawbacks; it can give rise to trade-offs or have mixed effects on development outcomes.Footnote6 The incentives created by tight electoral campaigns can also encourage candidates and parties to bend or break the rules of fair democratic elections to improve their chances of victoryFootnote7 and to use clientelist modes of distribution during election campaigns to mobilize voter support.

While the association between electoral competition and different types of clientelism has garnered an increasing amount of attention over recent years,Footnote8 the literature does not give a clear picture of how competition shapes the use of electoral clientelism where it is present but not ubiquitous, and how this relationship may differ between political parties. In a case where clientelism is common and over half of votes are typically “bought”, CorstangeFootnote9 finds that political parties in Lebanon use clientelism in contexts of both high and low competition, but that clientelism is used differently depending on the extent of that competition. These findings suggest that when competition is low, parties tend to target voters whose reservation price is low – the poor and weakly committed partisans. In contrast, high electoral competition tends to broaden the composition of the groups targeted by clientelist parties during election campaigns. Even if electoral clientelism may be more widespread in competitive areas, Kramon’sFootnote10 work in Kenya suggests that vote buying is more effective in influencing voter decisions in less competitive areas. We expand upon this work by examining the links between competition and electoral clientelism, and by emphasizing how this link affects how different types of parties engage in electoral clientelism.

We depart from the argument that competition for voter support provides parties and candidates with strong incentives to employ clientelist strategies during election campaigns, particularly in contexts where democracy is weakly institutionalized, and poverty provides fertile grounds for the operation of clientelism. Our baseline expectation is that when electoral clientelism is a feature of electoral campaigns – but is less pervasive – political parties direct resources employed for pre-electoral clientelist distribution to areas where the election outcome is expected to be close and hotly contested (rather than using clientelism as a general strategy for mobilizing voters across competitive and non-competitive districts). For instance, in highly competitive areas, electoral inducements – such as money or food parcels – offered by parties to voters may serve to mobilize supporters who are disinclined to turn outFootnote11 or it may help sway the vote choice of weakly opposed voters who are marginally inclined to support the competing party.Footnote12

We also argue that clientelist strategies can vary by the relative power-status of political parties – even within the context of a dominant party system. We hypothesize that challenger parties – which have more limited resources and face higher commitment problems – are likely to target clientelist efforts to a greater extent in competitive races. In contrast, the dominant party does not always have to employ clientelist strategies on the campaign trail to secure victory. These expectations do not imply that types of relational clientelismFootnote13 are not used in secure and uncompetitive municipalities during the election cycle, but they do imply that we should observe a more widespread use of electoral clientelism in competitive elections.

We examine these claims in the context of a relatively young democracy with a dominant party system – South Africa – and make two key contributions to the literature on competition and electoral clientelism in developing democracies. First, we unpack – theoretically and empirically – the clientelist strategies of dominant and challenger parties across areas with varying levels of electoral competition. Using evidence from the case of the highly contested 2016 municipal elections in South Africa to distinguish between the clientelist strategies used by the dominant party – the African National Congress (ANC) – and smaller, rival parties like the Democratic Alliance (DA). This allows us to examine the types of voters that are targeted by particular parties and how these effects are moderated by electoral competition. Second, we provide one of most encompassing tests yet of the relationship between electoral competition and electoral clientelism, and the conditions under which competition shapes parties’ use of clientelist strategies during election campaigns. We do so by employing data from a survey of over 3200 face-to-face interviews in the aftermath of the 2016 municipal electionsFootnote14 and merge this data with records of municipality-level vote shares from the previous election. In line with our expectations, we find strong evidence that past levels of electoral competition predict present rates of direct experience with various types of electoral clientelism. These findings elucidate different clientelistic strategies employed by South Africa’s main political parties and shed new light on the relationship between local-level electoral competition and clientelism in a system where national politics is usually characterized by one party dominance.

Competition and clientelism

Electoral clientelism denotes situations where political parties either distribute money or material benefits to voters during election campaigns conditional on voters casting their ballot for the distributing party in the election booth.Footnote15 Electoral clientelism is therefore a contingent political strategy where access to distributional benefits is exchanged in return for votes or political support around election time. While clientelism thrives in a variety of societies and political regime types,Footnote16 the advent of competitive elections in many countries across the globe has transformed the character of clientelist relationships from buying elite support towards a set of strategies aimed at mobilizing support among the mass of ordinary (and often poor) voters.Footnote17 Common clientelist strategies constitute attempts to sway people’s party choice,Footnote18 mobilize turnout,Footnote19 paying people to abstain,Footnote20 or a mix of these.Footnote21 In this article, we associate these strategies with “electoral clientelism”, because they are all attempts to provide positive inducements to people to affect their electoral behaviour.

Clientelist exchange and the value of votes

The extent and frequency of electoral clientelism varies considerably across countries.Footnote22 Where the practices are widespread, such as in Uganda or Lebanon, clientelist strategies such as vote-buying form one of the bases of established patronage networks and are commonplace during election campaigns. When electoral clientelism is more the exception than the rule, however, its implementation may take a distinctive form and the targeting of voters should be more considered and rational. When resources for electoral clientelism are scarce, it would be wasteful to attempt to affect votes indiscriminately. This perspective on electoral clientelism is consistent with models of machine politics,Footnote23 where parties engaging in vote buying rationally consider the potential value of a vote as a function of the expected returns relative to the costs. This does not imply that votes are bought indiscriminately in contexts where the practice is prevalent,Footnote24 rather the rational targeting of voters is likely to be more pronounced when the practice is less pervasive, as is the case in South Africa.

The supposition that parties and their brokers are more strategic and selective therefore begs the question: which votes make the most sense to influence? A growing literature taps into the targeted nature of vote buying in many countries, reaching the general conclusion that targets tend to be those who increase the cost-effectiveness of the transaction, such as low-income voters,Footnote25 or those who live in more densely populated urban areas.Footnote26 By pursuing low-income voters and densely populated areas, brokers can reach a larger pool of potential votes while spending significantly fewer resources in doing so. Alternatively, others argue that electoral clientelism is targeted to increase the reliability of the transaction (i.e. whether the attempt to buy a vote will be successful). Previous theories have suggested that a particular obstacle to the enforcement of vote buying is the secret ballot.Footnote27 When votes are bought, the secret ballot introduces a principal-agent problem that makes it difficult for party brokers to ensure that voters comply with their commitment to vote as promised. By relying on established grass-roots party networks that can reinforce the norm of following through with such practices, brokers can target loyal partisansFootnote28 or those who are more politically interestedFootnote29 to increase the reliability of the transaction.

Parties may also attempt to maximize the potential returns of electoral clientelism by targeting individuals in areas where the aggregation of transactions could plausibly make a difference to the electoral outcome. We expect this to be particularly relevant in a context such as South Africa, where political parties are often unable to credibly deliver on campaign promises and vote buying is employed as an alternative means to distribute goods.Footnote30 Any given vote in a competitive area has a higher value to parties, brokers, and vote sellers, and the potential returns are maximized. As we assume that parties seek to first and foremost maintain or obtain political power, we expect cost-effectiveness and reliability to be ancillary considerations following the potential returns. While it may be the case that party brokers target different groups of individuals within certain areas, we argue that parties will first seek to channel greater resources into competitive areas, where they are able to maximize the returns of electoral clientelism.Footnote31

| (1) | H1: Voters are more likely to be targets of electoral clientelism in electorally competitive areas. | ||||

Given that our expectation regarding competitiveness is grounded in the limited availability of resources, we can also extend this reasoning further by considering the resources available to political parties operating in such conditions. Electoral clientelism is not limited to the incumbent machine, and such strategies may also be used by parties in opposition in “duelling machines”.Footnote32 Resources are not evenly distributed between parties during election campaigns, and incumbent or dominant parties are likely to have a great advantage in this regard.Footnote33 In South Africa in particular, two-thirds of public party financing is based largely on proportionality of seats in national and provincial legislatures,Footnote34 favouring the ANC and other larger opposition parties. Sitting parties receive public and private funding to be used in all elections (national, provincial and local), whereby strategic allocation is generally hierarchical.Footnote35,Footnote36 In a dominant-party state such as South Africa, challenger parties may face higher commitment problems since they have yet to prove to many voters what they would, in fact, do in office. In competitive areas, such parties may use electoral clientelism as a pre-electoral signal to voters uncertain about their performance. Consequently, opposition parties with limited resources and greater commitment problems need to be more selective with their voter-targeting strategies. This does not imply that dominant parties will not target their clientelist efforts. Rather, the vigour with which electoral clientelism is targeted to competitive areas will increase as available resources for brokers and clientelist distribution decrease.

| (2) | H2: Challenger parties are likely to target competitive areas to a greater extent than dominant parties. | ||||

Importantly, these expectations are not expected to be limited to municipal election in South Africa. However, we do expect this to apply specifically at the level of the distribution of legislative seats as this is the level at which the returns of the election (election of candidates) are realized. In electoral systems where seats are distributed at the national or provincial level (such as is the case in national elections in South Africa), we would not expect parties to target specific municipalities or districts within those jurisdictions. Rather, the targeting of electoral jurisdictions should correspond to the administrative level at which seats are distributed. In first-past-the-post systems, for example, we should expect the targeting of competitive areas to take place at the constituency level.

Data and estimation strategy

To tests these hypotheses, we employ an observational research design using survey data collected in South Africa following the 2016 municipal elections.Footnote37 South Africa is characterized by widespread and persistent poverty and an income distribution that is estimated to be the most unequal in the world.Footnote38 Despite South Africa’s status as an upper-middle income country, this provides the material foundation that is often associated with clientelism.

South Africa also constitutes a case of a dominant party system. Every national election in the post-apartheid era has been won by the African National Congress (ANC) – a liberation-movement-turned-governing-partyFootnote39 – which is also the key source of clientelist distribution in the country.Footnote40 Indeed, clientelist distribution in South Africa often revolves around the governing party, the ANC. This induces a certain incumbency bias in the use of clientelist strategies because the ANC – in addition to its own party campaign funds – can access state resources and use them to target voters with benefits like food parcels or help getting access to social grants during election campaigns.Footnote41

A dominant party system like South Africa’s may appear as an unlikely setting to examine the relationship between electoral competition and electoral clientelism. However, even in party systems where one party tends to dominate and elections (on average) are not closely contested, clientelist strategies are frequently used as mechanisms of distributional politics during elections.Footnote42 More importantly, while the ANC’s dominance of South African politics is most clearly visible at the national level, it is increasingly challenged at the local level. This was witnessed most clearly in the 2016 municipal elections – easily the most contested in the country’s democratic history – where the ANC suffered the worst electoral result since the inaugural democratic elections in 1994, losing its majority and office of mayor in a number of key cities such as Johannesburg, Tshwane, and Nelson Mandela Bay. This is also a testimony to the fact that – at least at the local level in South Africa – competitive elections matter for alternations in local government power. Importantly for our purposes, local-level competition may also affect the distribution of clientelist goods within a dominant party system. Focusing on municipal elections therefore allows us to probe the relationship between municipal-level electoral competition and parties’ use of clientelism, even within a national context like South Africa’s that is characterized by one-party dominance and “monopolistic clientelism”, where one party – the ANC – mainly delivers and distributes goods using clientelist strategies.Footnote43

Local elections in South Africa serve to elect councillors to municipal councils. Municipal elections use a mixed electoral system, where voters cast two votes: One for a ward councillor in single-member districts and one for a political party on a party list that serves to create proportionality in the allocation of votes to seats.Footnote44,Footnote45 The mixed electoral system means that candidates running for the municipal council face a mix of incentives to run on party labels (in the wider municipality) and to cultivate personal votes and addresses issues pertaining to their immediate constituency (in wards). While political parties in South Africa generally rely heavily on national labels – like the ANC – winning office in municipal elections is important, not least because municipalities have responsibilities for providing essential public services like clean water, sanitation, and electricity. Indeed, failure to provide such services have given rise to a range of service delivery protests particularly in impoverished areasFootnote46 – suggesting that municipal councils play an important role in South African society for both political parties, candidates, and voters.

The data we use are from a nationwide survey fielded in all nine provinces of South Africa following the municipal elections on August 3rd, 2016. The survey was implemented in collaboration with Citizen Surveys – a South African survey and research consultancy. To obtain a random sample that is nationally representative, the sample was first stratified based on province, racial classification, and urban/rural area, ensuring sufficient coverage of subgroups in the data. Secondly, census data from Statistics South Africa was used to draw a sample of enumeration areas (EA) – the smallest geographical unit for which demographic data are available – within which to sample households and individuals. In the third step, enumerators performed random walks within the EAs in order to select households for the sample, and – finally – within the household a randomization algorithm pre-coded onto the tablet was used to select the respondents for interviews. All interviews were performed by trained enumerators in face-to-face interviews using a standardized, tablet-based questionnaire available to respondents in one of six languages. The sample size is 3,210 and is representative of voting-age citizens in South Africa.

The outcome of interest is the event of electoral clientelism. We create a binary measure at the individual level that equals “1” if a respondent answered “once or twice” or “often” to any of three questions asking whether a respondent was offered something “like food, a gift, or money” in return for voting, voting for them specifically, not showing up to vote (see Appendix Section 1 for full question wording). These questions represent measures of turnout buying, vote buying, and abstention buying respectively, which together fall under our conceptualization of electoral clientelism.

We find that in total, 8.4% of the sample reported personal experience with electoral clientelism.Footnote47 We address respondents who refused to answer, which were roughly 1% in each of the three questions, in two ways. First, we include the refusals in the “0” category, as they did not report any clientelist attempts to affect their vote per se. Second, we create an additional measure whereby the refusals are dropped, thus only comparing the respondents who answered affirmatively or “never”. As the third question in particular constitutes a different objective (abstention) than the first two (buying votes and turnout, respectively), we investigate these individually in some analyses. Expectations for targeting on the municipal level in this respect remain constant, although some individual-level factors (such as party loyalty) may produce heterogenous effects across our electoral clientelism measures. We account for this difference in several models below.

Asking respondents about electoral clientelism is potentially a sensitive subject and inevitably raises issues of social desirability bias. Recent studies have tested the extent of this bias using list experiments and found significant disparities between self-reported experiences and estimates that were derived from the list experiment.Footnote48 However, our main explanatory variable – electoral competition – is measured at the municipal level. As we are more interested in assessing the relationship between electoral competitiveness and the occurrences of – rather than the total estimated amount of – clientelism, the problems associated with social desirability bias would only bias our results to the degree that such under-reporting where a direct function the level of electoral competition. Nevertheless, to assess the validity of the direct measures of electoral clientelism used here, the survey also embedded a list experiment to capture the potentially sensitive question. Using this estimate as our dependent variable yielded result within 2–3% of the direct question (see Appendix Section 3 for comparison of estimates and analysis replication), thus providing strong measurement validity and alleviating concerns of social desirability bias with regard to experiences with electoral clientelism in South Africa.

Respondents were also asked to identify which party made offers to buy or suppress votes, which offers a significant empirical contribution relative to most studies which tend to aggregate electoral clientelism from all parties in their empirical models. As this too could be produce some degree of social desirability bias, we interpret results from this question with caution. In line with the expectations posited in H2, this allows us to investigate whether clientelist strategies are uniform or heterogeneous depending on whether they originate from the dominant party (ANC) or the main opposition party (DA). Moreover, this distinction makes identification and estimation of loyalists more valid.

The main explanatory variable is the degree of electoral competitiveness in a municipality. Although there are several ways to operationalize this concept which are subject to critique,Footnote49 we capture this with the absolute value of the margin of victory for the incumbent party compared with its largest competitor in the previous election, 2011,Footnote50 which is a standard proxy in the literature.Footnote51,Footnote52 We reverse the variable, such that higher values equal more past electoral competition, with a value of “0” indicating no competition, and 99.9 indicating an election decided by a vote margin of 0.1. Our measure of competition is temporally prior (2011) to the outcome variable (2016), which lowers the risk of endogeneity. Thus, our measure is arguably an improvement over previous studies that have assessed empirically the relationship between electoral competition and electoral clientelism, which have been measured at the national level,Footnote53 or during the same election period as vote buying was measured,Footnote54 or using a binary, subjective measure.Footnote55

As our study relies on real-word, election poll-like survey data, we are not able to randomize the main explanatory variable of interest – competition. Thus, our design is observational and as sample sizes are often limited in many municipalities, we control for a host of potential confounders. In addition, we also investigate how electoral competition moderates the effect of other factors at the individual and municipal level via cross-level interactions. First, we anticipate that poorer voters are likely to be targets of electoral clientelism. Building on several empirical studies capturing poverty in AfricaFootnote56 we construct an index of “experienced poverty” with six survey questions inquiring about the degree to which respondents lack basic and essential household goods, such as food, clean water, medicine, and cash (see Appendix Section 1 more details). Next, we account for party loyalty. We expect brokers to target party loyalists in competitive contexts to increase the reliability of the transaction. We measure “loyalist” both directly and indirectly. Given South Africa’s troubled history of racial segregation and Apartheid rule, racial affiliation is strongly related to vote choice in South Africa.Footnote57 We therefore include an indirect measure of the voter’s racial affiliation, which is a heuristic used by party brokers. Our direct measure is vote choice from the previous election, which we capture in models where we specific party vote buying (ANC, the DA or other smaller parties). Third, politically interested citizens to be a more reliable vote to target. We proxy “interest” by accounting for contact with any political figure/organization in the last 12 months and whether the respondent responded “yes” to the question of whether they “feel strongly about a particular party”, resulting in roughly 17% of the sample. In addition, we control for education, age and gender of the respondents.

At the municipal level, we consider three primary factors that are likely to attract more attempts to affect the vote when competition is high: population poverty, and the expected turnout To measure the first of these, we have two available measures, one being the logged population of the municipality as a continuous variable, and the other a binary measure that captures the urban/rural divide, equalling “1” if a respondent resides in a metropolitan area and “0” if otherwise. We proxy for the expected turnout with turnout in the municipal elections in 2011, thus temporarily prior to the dependent variable. We account for municipal level poverty (macro level), via a measure of poverty intensity, which captures the proportion of people living under official poverty levels. Finally, as there is considerable variation in both electoral competition, opposition party support, and the rate of electoral clientelism at the provincial level, we include provincial-level fixed effects to account for potentially unobserved confounders. We provide summary statistics for all variables in Appendix Section 1, Table A1.

Results

How does electoral competitiveness shape citizens’ experiences with electoral clientelism? To address this first question, we model an individual “i” living in municipality “m” as having experience with electoral clientelism or not ().Footnote58 With this in mind, we can empirically test the degree to which electoral competitiveness and other observable factors are systematically related to our outcome of interest. We express the relevance of electoral competitiveness on electoral clientelism via the following:

(1)

(1) Where we include a vector of municipal level variables

including electoral competitiveness, and individual level factors

that we believe will be systematically linked with an individual’s experience with electoral clientelism, along with unobservable idiosyncratic factors not directly included in the model

.

Our dependent variable is binary, thus we estimate all models using standard logistic regression.Footnote59 We employ survey design and population weights to adjust for representativeness of the sample in relation to the population.

Competition and electoral clientelism

reveals the main results for H1 – that electoral competition is positively linked with experiences with electoral clientelism at the municipal level. Model 1 includes only the focal relationship, while models 2 and 3 add individual and municipal level control variables. Overall, the results reported in suggest a strong, non-random effect of past levels of electoral competition on clientelism in 2016. The estimates are moreover larger when assessing the effect of competitiveness under control for additional individual and municipal level factors.

Table 1. Test of H1 – logistic estimates.

On the whole, our individual-level findings are much in line with expectations from the literature, in particular with respect to poverty and political interest.Footnote60 While some previous studies have found that lower education correlates with being a target of electoral clientelism,Footnote61 or findings are more in line with Gonzalez-Ocantos et al.,Footnote62 who find that education is positively correlated with vote buying. However, our results show that the largest impact on the outcome variable in terms of total explained variance is electoral competition.

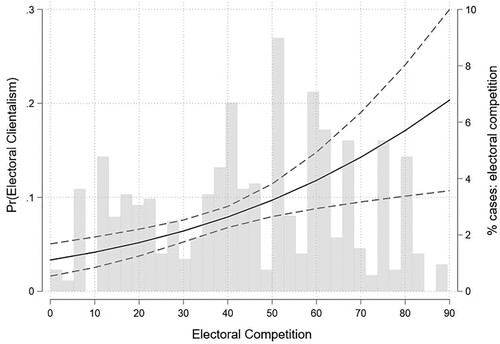

In models 4 and 5, we disaggregate the main measure into two dependent variables. Model 4 captures turnout buying that intends to encourage people to go to the polls on election day either to turnout or to vote specifically for a party, while model 5 captures abstention buying, which serves to reward people for not voting.Footnote63 In this case, we find similar strong effects of competition on the first type of vote buying, yet the positive effects are insignificant with regard to abstention. In sum, provides strong empirical evidence for in most cases, that the average effects of electoral competition on whole increase the people’s exposure to electoral clientelism.

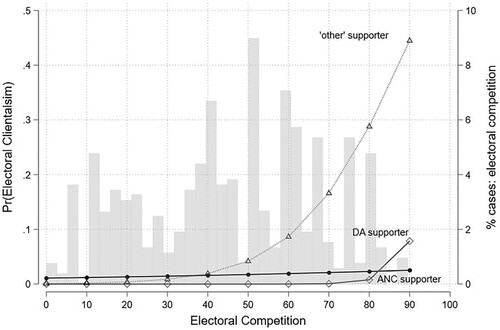

summarizes the main relationship from model 3 in , including a histogram of the distribution of electoral competition throughout the sample. The effect of competition on respondents’ experience with electoral clientelism is substantial. For example, a person living in one of the most competitive municipalities in South Africa is roughly seven times more likely to have experienced offers for their vote than a resident living among the least competitive municipalities, which is a different finding from those in previous studies which mainly found the direct effects of competition negligible.Footnote64

Figure 1. Predicted levels of vote buying over electoral competition.

Note: Estimates from model 3 in . Dashed line is a 95% confidence interval from municipal-level clustered standard errors. Histogram of the distribution of electoral competition among municipalities shown in background (and explained on right-side of y-axis).

Testing for heterogeneous effects among individual parties

In this section, we turn to which expects the lower resource-base of the opposition DA party as well as other smaller opposition parties to result in a more stringent, and more acute targeting strategy vis-á-vis the ANC. In our data, roughly 50% of all cases of electoral clientelism are perpetrated by the ANC, while the DA constitutes roughly 25%, leaving roughly 25% to all other parties. We thus separate our analyses into these three groups to maintain a sufficient number of cases to analyse statistically, while providing possibilities for nuance between the DA and other smaller parties.Footnote65

Models 1–4 in detail the findings with regard to the ANC – the dominant party and main clientelist party in South African politics.Footnote66 Notably, in our model diagnostic checks, we observe that among ANC electoral clientelism, the effect is actually somewhat “J-shaped”, in that it is slightly higher in highly uncompetitive areas, and higher in the most competitive (see Figure A2 in the appendix), with higher rates at lowest levels and highest levels of competition compared with moderate levels of competition. This suggests that the ANC could be applying a clientelist strategy to areas of strong core voters and more undecided voters. Albeit the standard errors around the estimates are noticeably wide, meaning these findings should be interpreted with some caution.

Table 2. Electoral competition and electoral clientelism by party: ANC.

In addition, we link our findings to the literature on micro-level factors of electoral clientelism via testing several cross-level interactions to see whether the parties target certain types of voters in municipalities with higher (or lower) levels of competition. We posit that this both provides a clearer picture of the political economy of vote buying by party, and provides motivation for future research. First, we see that although local ANC agents are much more inclined to target their own party supporters – compared with DA supporters or non-aligned swing voters – such targeting is not moderated by electoral competition (Model 2). This finding is consistent with the idea that the party leadership prefers to target competitive (swing) districts while party brokers on the ground within those districts tend to target core constituents who are easier to mobilize.Footnote67 We also find that those in poverty demonstrate a higher likelihood of being targets of electoral clientelism by the ANC, in particular in areas of higher electoral competition. However, racial affiliation does not explain patters in ANC electoral clientelism.

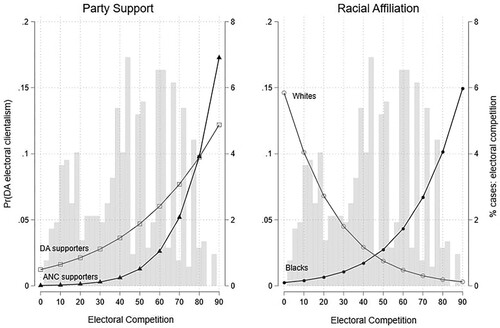

In , we turn to the determinants of clientelist attempts from the main opposition party – the Democratic Alliance (DA) in models 1–4 as well as the other opposition parties in models 5–8. To reiterate, H2 expects electoral clientelism to be targeted to a greater extent by the DA than the ANC. In these cases, to obtain a more valid picture of smaller party strategies, we only include municipalities where the DA or smaller parties competed. Model 1 shows a strong, positive relationship between competition and electoral clientelism. As in the ANC model, we check for non-linearity, and find in contrast to the ANC, a clear linear effect only – the DA targeted virtually no voters in uncompetitive municipalities, which – with the exception of the DA dominated Western Cape province – in most cases will have clear ANC dominance.

Table 3. Electoral competition and electoral clientelism by party: DA and all other parties.

The interactions in models 2–4 display clear differences in strategies between the ANC and the DA with respect to electoral clientelism. First, although the ANC targeted their supporters at much higher rates across the board, model 2 reveals that the DA in fact targets ANC supporters at higher rates than their own supporters in the most competitive municipalities (see ). This is an interesting finding because it suggests that – while the ANC is the main clientelist party – the DA also uses vote buying strategies during its electoral campaigns and seeks to expand its voter base by eating into potentially weaker ANC supporters. Given that the DA needs to make inroads into the ANC’s core constituency (black voters) in order to win elections, trying to buy the votes of ANC supporters (rather than mobilizing turnout) appears to be a rational strategy. Consistent with this finding, the effect of racial affiliation on DA electoral clientelism is also conditioned by competition. Whereas the DA targets white voters at higher rates in municipalities with lower competition, black voters (the core constituents of the ANC) are clearly the main targets of DA clientelist attempts in competitive municipalities.

Figure 2. Interaction effects and DA electoral clientelism.

Note: Lines represent the probability of vote buying, from models 2 (party support) and 3 (race) in .

Finally, in models 5–8, we examine the effects of competition on strategies of electoral clientelism for all other parties identified by respondents in the survey that competed in municipal elections in 2016, which includes such parties the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), among several others. We find overall that other smaller parties appear to have a similar pattern to the largest opposition party, the DA, in that where electoral competition is higher, there are greater levels of electoral clientelism (model 5). As with the DA, the quadradic effects of competition are insignificant. In model 5 we also observe that smaller parties target voters via partisanship – compared with “other” supporters (reference group) the DA supporters are the least likely targets on average, followed by ANC partisans. This implies that smaller parties are most likely to seek out their own core voters to increase turnout and vote share.

Model 6 sheds a clearer light on the relationship between partisanship and electoral clientelism. The results reveal a significant interaction between a respondent’s partisan support and municipal electoral competition from 2011, implying that compared with other partisans of the ANC, “other” supporters are significantly more likely to be targets of electoral clientelism where competition is higher, along with DA partisans. summarizes this finding. While the model predicts virtually zero vote buying by smaller parties at low levels of electoral competition, the targeting of “other” supporters increases markedly as a function of competition. DA supporters receive slightly higher levels of electoral clientelism at high levels of competition, while ANC supporters are essentially ignored by brokers of smaller parties at all levels of competition. While this is presumably the effect of smaller parties targeting their own supporters in highly competitive races, the data do not allow us to test this directly due to very few observations per party when disaggregating clientelism for each small party. Models 7 reveals that there is a slightly lower targeting of self-identified coloured voters relative to blacks at higher levels of competition, whereas poorer voters do not appear to be targeted at higher levels of competition by smaller political parties (model 8).

Checks of robustness

In Appendix Section 2, we replicate the main results of H1 using municipal (rather than individual) level data, and find similar results. In addition, we investigate whether the results we find using the direct measure of electoral clientelism are similar to those using the list experiment data (see Appendix Section 3). To the degree that we can replicate the results shown in the previous section (mainly for H1), we find quite similar effects.Footnote68 While competition has a positive effect on the number of items selected from the list on average, the rate of the number of items chosen increases at a higher rate among those that received the treatment in the list experiment as a function of competition (see Appendix Section 3 for more on this).

Conclusions

This article has investigated the relationship between electoral competition and electoral clientelism at the local level in a relatively young democracy, South Africa. In this context, electoral clientelism is present, but it is not ubiquitous – with an estimated 8% of the population in the 2016 election reporting experience with electoral clientelism. Our findings provide evidence for our expectation that given parties devote some resources to electoral clientelism, parties seem to systematically target municipalities with higher levels of electoral competition. In such contexts, our findings suggest that parties do in fact seem to strategically direct such resources to areas where they can feasibly flip (or hold) a previously close municipality. Our study therefore provides additional clarity to a relationship that has previously suggested mixed findings.Footnote69

Importantly, there are clear differences in how electoral competition determines opposition vis-á-vis dominant parties’ decisions to direct clientelist strategies during elections. Electoral competition does not significantly explain the clientelist strategy of the dominant ANC in a clear, linear way – ANC targets both voters in high and low competitive municipalities. Yet on the other hand, the strategies of the DA and other smaller opposition parties are clearly affected by competition – these parties overwhelmingly target highly competitive municipalities and tend to ignore moderate to less-competitive municipalities. Where the DA differs from other smaller parties appears to be who they target in highly competitive areas. Whereas smaller parties would appear to target their own core partisan supporters (or at least non-ANC and DA supporters), the DA appears to target ANC and/or black voters in competitive areas. This warrants further investigation in future research.

In sum, electoral competition is a desirable feature of all democracies, and it is necessary to hold incumbents accountable. Yet, competition may also create perverse incentives for parties to engage in clientelist practices that are antithetical to democracy and may undermine citizens’ trust in elections. Our findings suggest that more work is needed to explain the rise and fall of clientelism within countries. On the one hand, electoral clientelism may simply form part of the evolution of electoral practices in the early phases of new democracies, where parties have yet to build credibility with voters regarding more programmatic policies.Footnote70 If this is the case, one might expect the strategy to fade with a combination of shifting norms and/or stronger oversight and punishment laws for such behaviour, or as parties can establish more credibility with voters. On the other hand, electoral clientelism may be part of a broader clientelist equilibrium, where contingent exchanges of positive (and negative) inducements constitute an enduring part of politics and election campaigns for parties and voters – and from which there is no easy escape. Given that clientelist practices are still prevalent even in relatively advanced economies like Argentina,Footnote71 Brazil,Footnote72 Hungary and RomaniaFootnote73 and – as we have shown – South Africa, clientelism is likely an enduring feature of democratic elections for countries at different levels of economic development. Measures to reduce clientelism will therefore need to look beyond material conditions facilitating clientelism and much more on regulations surrounding party campaigns and finance during elections.

appendices.docx

Download MS Word (261.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of the Quality of Government (QoG) Institute for providing invaluable comments and feedback on previous drafts of this article, as well as Sarah Birch, Kristen Kao, and Jørgen Elklit.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Stephen Dawson

Stephen Dawson is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. He is affiliated with the Quality of Government (QoG) Institute and the Knowledge Resistance (KR) project. His research interests include electoral integrity, political competition, political behaviour, comparative political institutions, and the political economy of clientelism.

Nicholas Charron

Nicholas Charron is a Professor in the Department of Political Science and a Research Fellow at the Quality of Government Institute, University of Gothenburg. He is also a visiting scholar at the Minda de Gunzburg Centre for European Studies at Harvard University for the 2022–2023 academic year. Charron’s research is concerned with political behaviour, links between gender and politics and corruption, electoral behaviour, comparative politics on political institutions, studies of corruption and quality of government and how these factors impact economic development with a focus on Europe and the US.

Mogens Kamp Justesen

Mogens Kamp Justesen is Professor (mso) in the Department of International Economics, Government and Business, Copenhagen Business School. Justesen’s research concerns the political economy of development and issues of corruption, clientelism, and relations between business and politics.

Notes

1 Stasavage, “Democracy and Education Spending.”

2 Baum and Lake, “The Political Economy of Growth.”

3 Olken and Pande, “Corruption in Developing Countries.”

4 Bueno de Mesquita et al., Logic of Political Survival.

5 Acemoglu et al., “Democracy Does Cause Growth” and Besley, Persson, and Sturm, “Political Competition, Policy and Growth.”

6 De Kadt and Wittels, “Democratization and Economic Output.”

7 Dawson, “Electoral Fraud and the Paradox of Political Competition.”

8 e.g., Pierskalla and Sacks, “Personnel Politics”; Corstange, “Clientelism and Competitive Elections”; Kramon, “Where is Vote Buying Effective?”; Rundlett and Svolik, “Deliver the Vote!”

9 Corstange, “Clientelism and Competitive Elections.”

10 Kramon, “Where is Vote Buying Effective?”

11 Nichter, “Vote Buying or Turnout Buying?”

12 Stokes, “Perverse Accountability.”

13 Nichter, Votes for Survival.

14 Justesen et al., “Vote Markets.”

15 Mares and Young, Conditionality and Coercion; Nichter, “Conceptualizing Vote Buying”; Stokes et al., Brokers, Voters, and Clientelism.

16 Lust, “Democratization by Elections?”; Stokes et al., Brokers, Voters, and Clientelism.

17 Van de Walle, “The Democratization of Clientelism.”

18 Stokes, “Perverse Accountability”; Brusco, Nazareno, and Stokes, “Vote Buying in Argentina.”

19 Nichter, “Vote Buying or Turnout Buying?”

20 Cox and Kousser, “Turnout and Rural Corruption.”

21 Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter, “Varieties of Clientelism”; Nichter, “Conceptualizing Vote Buying.”

22 Keefer and Vlaicu, “Vote Buying and Campaign Promises.”

23 Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter, “Varieties of Clientelism”; Stokes, “Perverse Accountability.”

24 Corstange, “Clientelism and Competitive Elections.”

25 Brusco, Nazareno, and Stokes, “Vote Buying in Argentina”; Stokes, “Perverse Accountability”; Jensen and Justesen, “Poverty and Vote Buying.”

26 Gunes-Ayata, “Roots and Trends of Clientelism in Turkey”; Çarkoğlu and Aytaç, “Who gets Targeted for Vote-buying?”

27 Cox and Kousser, “Turnout and Rural Corruption”; Jensen and Justesen, “Poverty and Vote Buying”; Lehoucq, “When Does a Market for Votes Emerge?”; Mares and Young, Conditionality and Coercion; Nichter, “Vote Buying or Turnout Buying?”

28 Stokes et al., Brokers, Voters, and Clientelism.

29 Cerreras and Irepoglu, “Trust in Elections.”

30 Keefer and Vlaicu, “Vote Buying and Campaign Promises.”

31 We do not formally hypothesize about individual and group characteristics in this study. We do, however, include these factors in the analysis.

32 Stokes, “Perverse Accountability,” 324; Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter, “Varieties of Clientelism.”

33 Wantchekon, “Clientelism and Voting Behavior.”

34 EISA, African Democracy Encyclopaedia Project.

35 Lieberman, Martin, and McMurray, “When Do Strong Parties “Throw the Bums Out”?”

36 See Appendix Section 4 for more information on party financing and expenditures.

37 Justesen et al., “Vote Markets.”

38 Sands and de Kadt, “Local Support for Taxing the Rich.”

39 Ferree, “Electoral Systems in Context.”

40 Woller, Justesen, and Hariri, “The Cost of Voting and the Cost of Votes”; Nichter and Peress, “Request Fulfilling.”

41 Woller, Justesen, and Hariri, “The Cost of Voting and the Cost of Votes”; Wegner et al., “Citizen Assessments of Clientelism in SA.”

42 Lust, “Democratization by Elections?”

43 Nichter and Peress, “Request Fulfilling.”

44 Justesen and Schulz-Herzenberg, “The Decline of the ANC in 2016’s Municipal Elections.”

45 In areas outside the eight biggest cities (the so-called Metros), voters are given a third ballot for so-called district municipalities comprising 4–6 local municipalities that collaborate on issues of local development. National elections in South Africa use a closed-list party system.

46 Paret, “Contested Hegemony in Urban Townships.”

47 5.8% reported experiencing vote buying, 5.1% reported turnout buying and 4.1% reported abstention buying.

48 Gonzalez-Ocantos et al., “Vote Buying and Social Desirability Bias”; Kramon, “Where is Vote Buying Effective?”; Corstange, “Clientelism and Competitive Elections.”

49 See Kayser and Lindstädt, “Electoral Competitiveness.”

50 In the 2011 election, the ANC party is either the winner or the first runner up in all municipalities in our election, thus the measure employed is essentially the absolute difference between the ANC and its closest rival.

51 Eifert, Miguel, and Posner, “Political Competition and Ethnic Identification in Africa.”

52 South Africa has 205 local municipalities, and an additional eight urban municipalities. The citizen survey of just over 3,100 respondents on which we rely for our dependent variable, inter alia, sampled 157 municipalities (77%), including all eight of the urban areas. Therefore, the coverage is quite extensive and representative of the general population. On the whole, the municipalities omitted from the survey are rural areas, and do not exceed 10,000 inhabitants. A comprehensive list of the municipalities included in the analysis can be found in Appendix Section 1 (Table A2).

53 Jensen and Justesen, “Poverty and Vote Buying”; Pierskalla and Sacks, “Personnel Politics.”

54 Kramon, “Where is Vote Buying Effective?”; Rundlett and Svolik, “Deliver the Vote!”

55 Corstange, “Clientelism and Competitive Elections.”

56 Bratton, “Vote Buying and Violence in Nigeria”; Poku and Mdee, Politics in Africa; Jensen and Justesen, “Poverty and Vote Buying.”

57 Ferree, “Explaining South Africa’s Racial Census”; Harris, “Toward Performance-based Politics.”

58 In addition, we run several models whereby the unit of analysis is the municipality (see Appendix Table A3).

59 An alternative to this approach would be to use the data from the list experiment and construct an interaction between competition and the treatment variable, as per Gonzales-Ocantos, de Jonge, and Nickerson, “Legitimacy Buying” and Kramon “Where is Vote Buying Effective?”. The interaction term in this case would thus test whether the slope of competition varies significantly between the control and treatment groups, which we test for in Appendix Section 3, Table A8. In this approach, we focus mainly on testing H1, as testing H2 with the experimental data would require a number of triple interaction terms, with fewer observations than in the main analyses.

60 Stokes, “Perverse Accountability”; Bratton, “Vote Buying and Violence in Nigeria”; Jensen and Justesen, “Poverty and Vote Buying”; Mares and Young, Conditionality and Coercion.

61 Stokes, “Perverse Accountability”; Nichter, “Vote Buying or Turnout Buying?”

62 Gonzalez-Ocantos et al., “Vote Buying and Social Desirability Bias.”

63 Gans-Morse, Mazzuca, and Nichter, “Varieties of Clientelism.”

64 Corstange, “Clientelism and Competitive Elections”; Kramon, “Where is Vote Buying Effective?”

65 We acknowledge that there could be heterogenous effects among the small parties within the third group, for example the strategy of the EFF could be different from other parties. Yet for statistical purposes, we take a pragmatic approach and combine them, thus results should be treated with some caution.

66 Justesen et al., “Vote Markets”; Nichter and Peress, “Request Fulfilling.”

67 Stokes et al., Brokers, Voters, and Clientelism.

68 We are for example, unable to disaggregate by party from the list experiment.

69 Kramon, “Where is Vote Buying Effective?”; Rundlett and Svolik, “Deliver the Vote!”; Corstange, “Clientelism and Competitive Elections”; Jensen and Justesen, “Poverty and Vote Buying.”

70 Keefer, “Clientelism and Credibility in Young Democracies.”

71 Weitz-Shapiro, “What Wins Votes.”

72 Nichter, Votes for Survival.

73 Mares and Young, Conditionality and Coercion.

Bibliography

- Acemoglu, Daron, Suresh Naidu, Pascual Restrepo, and James A. Robinson. “Democracy Does Cause Growth.” Journal of Political Economy 127, no. 1 (2019): 47–100.

- Baum, Matthew, and Andrew Lake. “The Political Economy of Growth: Democracy and Human Capital.” American Journal of Political Science 47, no. 2 (2003): 333–347.

- Besley, Timothy, Torsten Persson, and Daniel M. Sturm. “Political Competition, Policy and Growth: Theory and Evidence from the US.” The Review of Economic Studies 77, no. 4 (2010): 1329–1352.

- Bratton, Michael. “Vote Buying and Violence in Nigerian Election Campaigns.” Electoral Studies 27, no. 4 (2008): 621–632.

- Brusco, Valeria, Marcelo Nazareno, and Susan C. Stokes. “Vote Buying in Argentina.” Latin American Research Review 39, no. 2 (2004): 66–88.

- Bueno de Mesquita, Bruce, Alastair Smith, Randolph M. Siverson, and James D. Morrow. The Logic of Political Survival. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003.

- Çarkoğlu, Ali, and S. Erdem Aytaç. “Who Gets Targeted for Vote-Buying? Evidence from an Augmented List Experiment in Turkey.” European Political Science Review 7, no. 4 (2015): 547–566.

- Cerreras, Miguel, and Yasemin Irepoglu. “Trust in Elections, Vote Buying, and Turnout in Latin America.” Electoral Studies 32, no. 4 (2013): 609–619.

- Corstange, Daniel. “Clientelism in Competitive and Uncompetitive Elections.” Comparative Political Studies 51, no. 1 (2018): 76–104.

- Cox, Gary, and Morgan Kousser. “Turnout and Rural Corruption: New York as a Test Case.” American Journal of Political Science 25, no. 4 (1981): 646–663.

- Dawson, Stephen. “Electoral Fraud and the Paradox of Political Competition.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 32, no. 4 (2022): 793–812.

- De Kadt, Daniel, and Stephen B. Wittels. “Democratization and Economic Output in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Political Science Research and Methods 7, no. 1 (2019): 63–84.

- Eifert, Benn, Edward Miguel, and Daniel Posner. “Political Competition and Ethnic Identification in Africa.” American Journal of Political Science 54, no. 2 (2010): 494–510.

- Electoral Institute for Sustainable Democracy in Africa (EISA). African Democracy Encyclopaedia Project. Accessed April, 2019. https://www.eisa.org/wep/souparties2.htm.

- Ferree, Karen. “Explaining South Africa’s Racial Census.” The Journal of Politics 68, no. 4 (2006): 803–815.

- Ferree, Karen. “Electoral Systems in Context: South Africa.” In The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems, edited by Erik S. Herron, Robert J. Pekannen, and Matthew S. Shugart, 943–964. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Gans-Morse, Jordan, Sebastian Mazzuca, and Simeon Nichter. “Varieties of Clientelism: Machine Politics During Elections.” American Journal of Political Science 58, no. 2 (2014): 415–432.

- Gonzalez-Ocantos, Ezequiel, Chad Kiewiet de Jonge, Carlos Meléndez, Javier Osorio, and David Nickerson. “Vote Buying and Social Desirability Bias: Experimental Evidence from Nicaragua.” American Journal of Political Science 56, no. 1 (2012): 202–217.

- González-Ocantos, Ezequiel, Chad Kiewiet de Jonge, and David Nickerson. “Legitimacy Buying: The Dynamics of Clientelism in the Face of Legitimacy Challenges.” Comparative Political Studies 48, no. 9 (2015): 1127–1158.

- Gunes-Ayata, Ayse. “Roots and Trends of Clientelism in Turkey.” In Democracy, Clientelism, and Civil Society, edited by Luis Roniger, and Ayse Gunes-Ayata, 49–63. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1994.

- Harris, Adam. “Toward Performance-Based Politics: Swing Voters in South Africa’s 2016 Local Elections.” Politikon 47, no. 2 (2020): 196–214.

- Jensen, Peter, and Mogens K. Justesen. “Poverty and Vote Buying: Survey-Based Evidence from Africa.” Electoral Studies 33 (2014): 220–232.

- Justesen, Mogens K., Louise Thorn Bøttkjær, Scott Gates, and Jacob Gerner Hariri. “Vote Markets, Latent Opportunism, and the Secret Ballot.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, San Francisco, August 31–September 3, 2017.

- Justesen, Mogens K., and Collette Schulz-Herzenberg. “The Decline of the African National Congress in South Africa’s 2016 Municipal Elections.” Journal of Southern African Studies 44, no. 6 (2018): 1133–1151.

- Kayser, Mark Andreas, and René Lindstädt. “A Cross-National Measure of Electoral Competitiveness.” Political Analysis 23, no. 2 (2015): 242–253.

- Keefer, Philip. “Clientelism, Credibility, and the Policy Choices of Young Democracies.” American Journal of Political Science 51, no. 4 (2007): 804–821.

- Keefer, Philip, and Razvan Vlaicu. “Vote Buying and Campaign Promises.” Journal of Comparative Economics 45, no. 4 (2017): 773–792.

- Kramon, Eric. “Where is Vote Buying Effective? Evidence from a List Experiment in Kenya.” Electoral Studies 44 (2016): 397–408.

- Lehoucq, Fabrice. “When Does a Market for Votes Emerge?” In Elections for Sale: The Causes and Consequences of Vote Buying, edited by Frederic C. Schaffer, 33–45. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2007.

- Lieberman, Evan, Philip Martin, and Nina McMurray. “When Do Strong Parties “Throw the Bums Out”? Competition and Accountability in South African Candidate Nominations.” Studies in Comparative International Development 56 (2021): 316–342.

- Lust, Ellen. “Democratization by Elections? Competitive Clientelism in the Middle East.” Journal of Democracy 20, no. 3 (2009): 122–135.

- Mares, Isabela, and Lauren E. Young. Conditionality and Coercion: Electoral Clientelism in Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019.

- Nichter, Simeon. “Vote Buying or Turnout Buying? Machina Politics and the Secret Ballot.” American Political Science Review 102, no. 1 (2008): 19–31.

- Nichter, Simeon. “Conceptualizing Vote Buying.” Electoral Studies 35 (2014): 315–327.

- Nichter, Simeon. Votes for Survival: Relational Clientelism in Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Nichter, Simeon, and Michael Peress. “Request Fulfilling: When Citizens Demand Clientelist Benefits.” Comparative Political Studies 50, no. 8 (2017): 1086–1117.

- Olken, Benjamin, and Rohini Pande. “Corruption in Developing Countries.” Annual Review of Economics 4 (2012): 479–509.

- Paret, Marcel. “Contested ANC Hegemony in the Urban Townships: Evidence from the 2014 South African Election.” African Affairs 115, no. 460 (2016): 419–442.

- Pierskalla, Jan H., and Audrey Sacks. “Personnel Politics: Elections, Clientelistic Competition and Teacher Hiring in Indonesia.” British Journal of Political Science 50, no. 4 (2020): 1283–1305.

- Poku, Nana, and Anna Mdee. Politics in Africa: A New Introduction. London: Zed Books Ltd, 2013.

- Rundlett, Ashlea, and Milan Svolik. “Deliver the Vote! Micromotives and Macrobehavior in Electoral Fraud.” American Political Science Review 110, no. 1 (2016): 180–197.

- Sands, Melissa, and Daniel de Kadt. “Local Exposure to Inequality Among the Poor Increases Support for Taxing the Rich.” Preprint. SocArXiv, 2019. doi:10.31235/osf.io/9ktg2.

- Scott, James C. “Corruption, Machine Politics, and Political Change.” American Political Science Review 63, no. 4 (1969): 1142–1158.

- Stasavage, David. “Democracy and Education Spending in Africa.” American Journal of Political Science 49, no. 2 (2005): 343–358.

- Stokes, Susan C. “Perverse Accountability: A Formal Model of Machine Politics with Evidence from Argentina.” American Political Science Review 99, no. 3 (2005): 315–325.

- Stokes Susan, C., Thad Dunning, Marcelo Nazareno, and Valeria Brusco. Brokers, Voters, and Clientelism: The Puzzle of Distributive Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Van de Walle, Nicolas. “The Democratization of Clientelism in Sub-Saharan Africa.” In Clientelism, Social Policy, and the Quality of Democracy, edited by Diego Abente Brun, and Larry Diamond, 230–252. Baltimore: JHU Press, 2014.

- Wantchekon, Leonard. “Clientelism and Voting Behavior: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Benin.” World Politics 55, no. 3 (2003): 399–422.

- Wegner, Eva, Miquel Pellicer, Markus Bayer, and Christian Tischmeyer. “Citizen Assessments of Clientelistic Practices in South Africa.” Third World Quarterly 43, no. 10 (2022): 2467–2487.

- Weitz-Shapiro, Rebecca. “What Wins Votes: Why Some Politicians opt out of Clientelism.” American Journal of Political Science 56, no. 3 (2012): 568–583.

- Woller, Anders, Mogens K. Justesen, and Jacob Gerner Hariri. “The Cost of Voting and the Cost of Votes.” The Journal of Politics (Forthcoming). DOI: 10.1086/722047.