?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The literature on government popularity focuses on security and prosperity as two key factors that shape government evaluation. While a recent wave of studies explores the impact of these factors on public support in non-democratic countries, the Arab World is one region that has received relatively little scholarly attention. Beginning with the Arab Uprisings, ongoing national crises have created myriad security challenges for governments and led to greater political instability. Since under these conditions citizens tend to be more uncertain about the political environment, it is unclear how those who are concerned about security challenges can decide whether to reward or punish the incumbent government. This study proposes that individuals may use information about the economy to make a decision concerning the security-popularity linkage. Using individual-level data from 13 countries in the Arab World from 2010 to 2019, we find that citizens are more likely to reward or punish the government for security issues (external and internal) if their judgement is aligned with their economic sentiment.

Much political thought about representative democracy centres on the notion that the governed can and do hold the executive accountable for its performance. Citizens are expected to evaluate the incumbent over the course of the term in office, rewarding them in good times and punishing them in bad times.Footnote1 Concerns about whether and how citizens hold leaders and governments accountable have driven decades of scholarly interest in the impact of domestic and foreign policies on popularity ratings.Footnote2 If the public does not hold the incumbent accountable for the outcomes of government policies, one of the foundations of democratic governance is clearly threatened.

Whilst the bulk of the literature on government popularity focuses on advanced democracies, a recent wave of studies examines public support in other political contexts, with most of these studies focusing on the impact of the economy.Footnote3 The long-held assumption that only democratically elected governments can be held accountable for their economic performance has been challenged and tested in authoritarian regimes,Footnote4 post-Communist countries,Footnote5 and developing democracies.Footnote6 The key conclusion of these studies is that the economy-popularity linkage is also present in these political systems, although the impact can vary depending on the political context.

In this recent wave of studies, security issues received less scholarly attention; although there is evidence that on-going security threats in non-democratic countries are politically influential.Footnote7 We know from the literature on popularity that security threats can have different impacts on support for the government depending on whether they are perceived as external, which is expected to give a boost to popularity, or internal, which is likely to decrease support for the government.Footnote8 Since this distinction has not been applied to popularity models outside the democratic context, this study, therefore, begins by asking whether concerns about internal and external security issues play a similar role in non-democratic countries.

At the same time, we should reconsider the implicit assumption in the popularity literature that individuals have complete information to evaluate their government.Footnote9 Evaluation of the government can be more challenging when security problems are coupled with greater political instability and the state of the nation is fraught and uncertain. The internal and external conditions that make individuals more concerned about security issues, are often related to broader national developments that make the political environment less predictable.Footnote10 Characteristics of the political system, most notably regime transition and authoritarian practices, can further exacerbate uncertainty about the intentions of the government and its competence.Footnote11 As uncertainty about the political environment increases, it can constrain individuals’ ability to evaluate the government.Footnote12 Therefore, this study also asks how can those who are worried about security issues, be more certain about whether the government should be rewarded or punished for their concern?

Looking for ways to decide whether security concerns should be attributed to the government, individuals can rely on other policy outcomes, specifically the economy as a pivotal social issue in various political systems,Footnote13 to make more informed judgments about their government. An additional issue domain can signal incumbent competency and therefore provide more certainty about how to evaluate the government. When an individual considers rallying in support of the government when confronted with a foreign threat, or punishing the government for domestic divisions, uncertainty can be reduced if there is an additional indication that expressing satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the government is the right thing to do. This study, therefore, argues that individuals who are concerned about external security should be more certain about supporting the government if they have a positive perception of the economy; and those who are concerned about internal security should be more certain about punishing the government if they have a negative perception of the economy.

To test these hypotheses this study focuses on the Arab World from 2010 through 2019, as a region where complex and lingering security challenges stand out particularly starkly. Specifically, following the Arab Uprisings and the political instability that came with it, many in the Arab World became concerned about domestic and foreign threats.Footnote14 While the popular uprisings dissipated within a few years, the political turmoil that ensued in some countries had a more enduring impact that projected across the entire region.Footnote15 This study uses individual-level data from mass surveys conducted by the Arab Barometer (AB) covering 13 countries during the decade following the Arab Uprisings. Through multi-level modelling techniques, we bring together both individual – and national-level indicators to explain variation in the impacts of security issues on government popularity. Our findings show the distinct impacts of concerns with internal and external security threats, and their interaction with evaluations of the economy, in shaping support for government.

This study makes three important contributions. First, it shows that government popularity in the Arab World fits with a body of recent work demonstrating that evaluations of policy issues can play an important role in shaping satisfaction with the executive in non-democratic contexts.Footnote16 Second, the study further shows that whilst the logic of the distinct impacts of external and internal security concerns on popularity also holds in a non-democratic context, the security-popularity linkage can vary considerably across individuals. This can help explain the broader empirical puzzle in the literature of why security issues do not always have the expected impact on popularity.Footnote17 Third, the findings of this study imply that political issues are not necessarily in competition with one another for citizens’ attention, but rather can operate together in shaping support for the incumbent government.

Economy, security and government popularity

Two key factors that have been a central focus of studies on government popularity are prosperity and security.Footnote18 Of these two factors, the economy has attracted more scholarly attention both at the individual and the national level. Even in non-democratic political systems, where public opinion is often viewed as a product of political manipulation, studies have shown that the economy shapes support for the executive.Footnote19 Gandhi and Lust-OkarFootnote20 argue that whilst elections under authoritarianism operate according to a different logic than elections in democratic polities, they nevertheless afford a pathway for economic accountability. This is supported by Gélineau's large-N cross-national study of electoral accountability in developing regions, which finds that patterns of economic approval in these regions are “strikingly similar to those obtained in comparable studies of the developed world.”Footnote21 Nevertheless, the study also shows that the extent of the economic effect can vary across countries, and over time within countries, which might indicate that other factors in the political environment interact with the economic effect.

The literature on popularity ratings has also shown that security conditions often shape public support for the executive.Footnote22 The notion of a security effect has developed over the years to include various types of positive and negative occurrences, which share a common aspect: the expectation that the government will maintain a safe and secure environment.Footnote23 Although studies on popularity in non-democratic political systems mostly focus on economic effects,Footnote24 there is some evidence from single-country studies, which focus on specific events, that popularity models should also consider the impacts of security.Footnote25

Conceptualization and operationalization of both the economy and security have changed over the years to focus on subjective perceptions as key drivers of government popularity.Footnote26 In the context of the economy, the literature shows that what ultimately counts for citizens is their interpretation of the state of the economy, rather than objective conditions such as unemployment or inflation.Footnote27 Similarly, for security, indicators that focus on the physical consequences of events, do not always capture individual judgement of these consequences.Footnote28 Rather than trying to determine the nature of these events, focusing on perceptions can provide insight into how these conditions were understood by citizens.Footnote29

Most scholarship on government popularity tends to examine the independent impact of the economy and of security on public support for the executive. The main exception is a cross-national study by Tir and Singh,Footnote30 which examines whether foreign policy crisis offsets the negative impact of a poorly performing economy in terms of incumbent approval. However, the authors do not find support for an offsetting effect, which is in line with studies on the diversionary theory that report mixed results about the postulation that, via rally effects, foreign crises divert attention from domestic issues and unify fractured societies.Footnote31 Overall, the government popularity literature to date has engaged in limited investigation of the interaction between security and economic evaluations in shaping support for government.

Theory and hypotheses

Beginning with Mueller'sFootnote32 pioneering study on presidential popularity, scholars identified that certain conditions lead to rally effects. According to Mueller's threefold criteria, rally points are associated with events that are (1) international, (2) involve the executive, whilst also being (3) “specific, dramatic, and sharply focused.”Footnote33 The last two criteria require citizens to notice changes in conditions and perceive them as relevant to government performance. Yet, it is the first criterion that turns a politically dramatic event into a rally point. Early studies understood the first criterion as mostly referring to foreign crises and diplomatic activities. Later studies, however, have extended this criterion to include any security event that has a major international component, even if the event occurs domestically.Footnote34 The external component of the threat provokes a unified response across party and social lines to unify the population and support the executive.

With the understanding that international threats fuel the rally effect, the literature has also acknowledged the negative impact of domestic instability and local security threats on support for the executive. For example, studies have shown that crime,Footnote35 social unrestFootnote36 and domestic political violenceFootnote37 can reduce support for the executive. The main reason for the negative impact of domestic threats on support for the executive is that such threats might exacerbate internal divisions,Footnote38 when citizens feel targeted either by the attackers, or by the government as part of its efforts to enforce order.

The distinction between the positive impact of external threats and the negative impact of internal threats on public support has served as the basis for studies on government popularity.Footnote39 This distinction is closely related to psychological theories of in-group versus out-group threats.Footnote40 The rally phenomenon of external threats occurs when the superordinate category of the nation-state is made salient. Then “group members are more likely to think of themselves as ‘one unit’ rather than two separate groups.”Footnote41 Internal threats, however, highlight the battle between competing identities, and the cost of the threats, which can result in a decrease in support for the incumbent government. We, therefore, begin our theoretical model with two hypotheses: (H1) individuals who are concerned about external security threats are more likely to support the incumbent government; whereas (H2) those who are concerned about internal security threats are more likely not to support the government.

Yet, the threats that make more people concerned about security issues are often related to an increase in political uncertainty, which can be conceptualized as incomplete information.Footnote42 Following Lupu and RiedlFootnote43, we think of uncertainty as the imprecision with which individuals are able to predict future behaviour of, and interactions with, political actors. National crisis, social unrest, wars, and similar security developments can make the political environment more unstable and therefore less predictable, which means that individuals will have more doubts about their understanding of it.Footnote44 As uncertainty increases it tends to have a significant impact on citizen evaluations and preferences.Footnote45 Most importantly, during turbulent times the policy-making process is perceived to be more volatile, which makes its evaluation more challenging.Footnote46 As previous studies have shown, uncertainty constrains individuals’ ability to anticipate government behaviour on specific issuesFootnote47 and may even reduce citizens’ capacity to evaluate their government.Footnote48

Characteristics of the political system can further exacerbate uncertainty,Footnote49 especially during periods of regime transition when citizens are faced with uncertainty about the ultimate intentions of governments.Footnote50 Authoritarian practices of information censorship or manipulation can also lead to political uncertainty. While the leadership of non-democratic regimes can use media manipulation to achieve higher popularity ratings, citizens are sometimes aware of these efforts, even when the regime is trying to camouflage its media controls.Footnote51 This can bring about confusion and uncertainty regarding government competence when, for example, citizens need to decide whether less “bad news” in national media is due to a reduction in relevant events, or due to information restrictions by the government.Footnote52 As noted by Shadmehr and Bernhardt,Footnote53 there can be extensive uncertainty in citizens’ assessments “because of propaganda and state censorship that limit reliable information dissemination to citizens.” Overall, political uncertainty that is related to security problems, can be amplified by the political system, which can then make evaluation of the incumbent government more challenging.

We argue that those who are concerned about security issues but may be uncertain about their evaluation of the government, can be expected to rely on additional information to address their doubts about the executive. The supplementary information can help individuals make more informed evaluation decisions.Footnote54 Since people tend to dislike uncertainty,Footnote55 they can use information they already possess in their evaluation process. In other words, citizens will be more likely to approve or disapprove of the way the government is doing its job concerning security issues if they can find support for their judgment of the government in another politically relevant domain. Whilst most studies on popularity assume that politically relevant issues are evaluated independently,Footnote56 by relaxing this assumption we allow for two issues to interact in shaping government evaluation. This logic resonates with a competence-based voting (or popularity) approach, where rational citizens optimally use all available information to infer administrative competence.Footnote57 Supporting the government based on evaluation of more than one issue should make citizens more certain about how they judge the incumbent.

Given our expectation that external and internal security concerns will have a distinct impact on support for the executive, we can now consider how these concerns would influence government popularity in the context of the economy, as a key policy issue in both democratic and non-democratic political systems.Footnote58 Individuals who are concerned about external security should be more certain about supporting the government if they have a positive perception of the economy. Therefore, it is hypothesized that (H3) As evaluation of the economy becomes more positive (negative) the positive impact of external security concern should increase (decrease). On the other hand, individuals who are concerned about internal security should be more certain about punishing the government if they have a negative perception of the economy. It is therefore hypothesized that (H4) As evaluation of the economy becomes more negative (positive) the negative impact of internal security concern should increase (decrease). These hypotheses are meant to test if information that individuals have from the economic domain helps them judge whether the government is competent to effectively handle security threats.

Focusing on the Arab World

Until the twenty-first century, Arab-majority states in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region were noted for regime stability and authoritarian persistence.Footnote59 However, following the Arab Uprisings that commenced in Tunisia in late-2010, several states underwent political instability, regime transition and even state breakdown.Footnote60 During this period, security conditions changed dramatically, and individuals in the Arab World were exposed to both local and foreign threats: from rising domestic social violence in Egypt,Footnote61 to foreign military interventions in Libya and Yemen.Footnote62 While these types of threats were not new,Footnote63 they posed major political and social challenges to regimes and their leaders.Footnote64

Alongside these security threats, this period of political instability in the Arab World has been characterized by uncertainty.Footnote65 Post-Arab-Uprisings, a “wide range of political and socio-economic uncertainties have been escalated dramatically.”Footnote66 The Arab Uprisings led to the removal of long-standing leaders, the outbreak of civil wars, and destabilizing protest across the region as “popular mobilisation broke down previously established governing practices and fragmented the state apparatus.”Footnote67 For several years following the Arab Uprisings regime trajectories in a number of states remained unclear – as there was a “struggle of rival social forces – the military, civil society, Islamists, and workers – to shape outcomes.”Footnote68 Financial stability was also threatened across the region with political crises prompting volatile economic conditions.Footnote69 In addition, political transitions created uncertainty regarding social policy agendas towards minority groupsFootnote70 and women.Footnote71

Authoritarian practices in general, and information manipulation in particular, may also have contributed to uncertainty about the ultimate intentions of governments and their policies. Whilst the Arab Uprisings demonstrated that social media and new technologies can create new opportunities for political activism and access to information,Footnote72 they also prompted existing elites to respond with new mechanisms of manipulation and control.Footnote73 The Arab Uprisings have led to increased state violence in most of the regionFootnote74 as established elites struggle to maintain control.Footnote75 There is also evidence that social media platforms were in some cases co-opted “by agents of the state for repression and misinformation.”Footnote76 Under these conditions of security threats coupled with political uncertainty, how can citizens who are concerned about security evaluate their government? Whilst the literature on the Arab World shows that good governance credentials lead to broader popular support,Footnote77 and that the state of the economy matters in the calculus of supporting the incumbent,Footnote78 we still do not know how citizens in the Arab World evaluate their government based on security issues.

Data and operationalization

In this study, we use survey data from four waves of the Arab Barometer (AB; 2010–2019) which cover the period from the beginning of the Arab Uprisings to a decade later (see Appendix Table A1).Footnote79 The AB was designed to study the social, political, and economic attitudes of ordinary citizens across the Arab World, whilst also taking into account variation in contextual factors across countries.Footnote80 Each wave of the AB covers a period of two-to-three years. The survey produces a cross national comparable set of survey questions. To measure country-level control variables, the study also utilizes data from the World Development Indicators, Freedom House Index, and Autocratic Regime Data (see Appendix Table A2).

Government Popularity: The dependent variable is expressed support for the incumbent government. The AB asks the following question in all survey waves and countries included in the study: To what extent are you satisfied with the government's performance? The wording of the question is parallel to surveys in other regions.Footnote81 Similar to much of the literature on government popularity,Footnote82 we distinguish between those who approve and those who disapprove of the government: individuals who indicated they are satisfied with government performance (values 6–10 on a 10-point scale) are considered highly supportive and coded 1, while all others are coded zero. The mean of this variable in the sample is 0.31.

Security Concern – Internal and External: This study focuses on individuals’ general perceptions of security issues,Footnote83 and the two main independent variables are individual concern with internal security or external security. To measure these two variables, we use an AB question that asks respondents: What are the two most important challenges your country is facing today? Two response categories specifically refer to security threats. Individuals whose response was “internal stability and security” were coded as being concerned with internal security. Respondents who chose “foreign interference” as the main challenge facing the country, were coded as being concerned with external security.Footnote84 We further differentiated between respondents who selected one of the two security categories as either the first (coded 2) or the second (coded 1) most important challenge. All others were coded 0. Overall, about 30 percent of all individuals were concerned with at least one security issue, as either first or second most important challenge. The mean of internal security is 0.24 and the mean of external security is 0.20.

When it comes to external security, states in the Arab World have been subjected to various threats of foreign interference, from political interventions to military invasions. While some aspects of foreign interference might take place in the respondent’s country, this is still likely to trigger the rally effect if it is perceived to incorporate a major international component.Footnote85 Moreover, although foreign interference does not capture all external threats to countries in the Arab World, it has three main benefits as a security indicator: for many decades foreign interference has been a major security issue in the Arab World; oftentimes foreign interference has been an integral component of other, and sometimes broader, external threats; and it captures the type of concern that should lead to a rally when an out-group threatens the nation-state.Footnote86

Economic Evaluation: For Hypotheses 3 and 4, we are interested in the impact of economic evaluation. A rich literature on economic approval/voting has demonstrated a strong relationship between the state of the economy and citizens’ preferences.Footnote87 The AB asks the following question: “How would you evaluate the current economic situation in your country?” This question focuses on a current sociotropic evaluation of the economy, which is inline with our theoretical model. Respondents were able to choose between four categories, ranging from “very bad” (coded 1), to “very good” (coded 4). The mean of this variable in the sample is 2.04.

Control Variables: To be consistent with the rich literature on popularity and vote functions, we included several individual-level control variables: party closeness, religiosity, age, education, income, gender and unemployment. These controls follow cleavage theories of political behaviour and are meant to capture long-standing predispositions to support the incumbent government, as well as traditional sociodemographic indicators.Footnote88 Also included in the models are national-level controls to account for prominent characteristics of countries in the Arab World,Footnote89 namely: national unemployment, oil resources, political rights and civil liberties, and whether the country is a monarchy or a republic (see Appendix Table A6 for control variables’ description).

Statistical method

To explore the determinants of government popularity in the Arab World, this study uses a multilevel and mixed effects research design. We are interested in understanding how individuals’ support for the government is shaped by economic and security evaluations over multiple surveys and across countries.Footnote90 One of the sources of instability in the main coefficients of popularity models is confining the analysis to a single country,Footnote91 which leads to a small sample size. This tends to restrict the variance of the variables. As a result, the possibility for uncovering statistical significance is reduced and the R2 decreases in magnitude.Footnote92 To help address these difficulties, we pool the variables, as measured in 13 countries in various time periods. With this approach we are able to substantially boost sample size. The data is thus observed at the individual level, while allowing for random effects due to characteristics of countries and due to multiple surveys in different time periods within countries.

Results of baseline models

Our first two hypotheses postulate that internal and external security concerns have different impacts on government popularity. In we evaluate a baseline model to test these hypotheses in a multilevel framework. As Model 1 shows, external security concern has a positive and significant impact on government popularity. Internal security concern, however, has a negative and significant impact on public support for the government. Transforming the logit coefficients into predicted probabilities indicates that, all else equal, individuals who are concerned about external security are 4.5 percentage points more likely to be satisfied with the government, whereas individuals who are concerned about internal security are 2.1 percentage points less likely to be satisfied. Moreover, Model 1 shows that a more positive evaluation of the economy is likely to increase support for the government.Footnote93

Table 1. The impacts of security concern and economic evaluations on government support.

In the next two models (, Models 2 and 3) we add several control variables at the individual-level and the country-level that might shape government popularity. These control variables enable us to construct a more comprehensive model of government popularity in the Arab World, as well as take into account citizens’ initial bias or predisposition toward the government. The results of Model 2 show that, even when individuals’ political and social characteristics are taken into account, the impact of security concerns and economic evaluation remain significant and in the expected direction. The positive impact of the party closeness variable indicates that individuals are more likely to be satisfied with their government if they identify with the incumbent party. Also, religious individuals are more likely to support their government, which is consistent with the literature on voting behaviour in other parts of the world. Finally, individuals with financial difficulties, younger and better educated, are less likely to be satisfied with the performance of their government. While the coefficient of the unemployment variable is in the expected direction, its impact is not significant.

Model 3 extends the previous model by also including national-level political and economic characteristics. As in Model 2, even with the full set of control variables, the impact of the main independent variables – security concerns and economic evaluation – remain significant and in the expected direction. Additionally, critical attitudes toward the government are more prevalent when there is more freedom to express them. The other three control variables that measure whether the country is a monarchy, a major oil exporter, and the national level of unemployment, are not significant. Overall, we find support in all three models for our first two hypotheses regarding the distinct impact of external and internal security concerns on government support.

Results of interaction models

After establishing three baseline models of government popularity in the Arab World, we continue to investigate how popularity is shaped by the relationships between the two types of security concern and economic evaluation. That is, the models in extend the baseline models by adding two interaction terms. In all three models, the interaction terms are positive and significant, which indicates that the impact of internal and external security concerns on government satisfaction depends on individual evaluation of the state of the economy.

Table 2. The interaction of security concern and economic evaluations.

Models 4–6 show that with increased positive values of economic evaluation, the external security variable becomes more positively associated with government popularity. They also show that with increased negative values of economic evaluation, the internal security variable becomes negatively associated with government popularity. Moreover, both the individual – and the national-level control variables have a similar effect on government evaluation as in the baseline models. Most importantly, comparison of the model fit criteria – AIC and BIC – between the baseline models and the interaction models, indicates a clear preference for the latter. When similar model specifications are compared – Models 1 and 4, Models 2 and 5, and Models 3 and 6 – we see that the values of both the AIC and the BIC are lower in the interaction models. The inclusion of interaction terms between security and the economy better explains government satisfaction than a model without them.

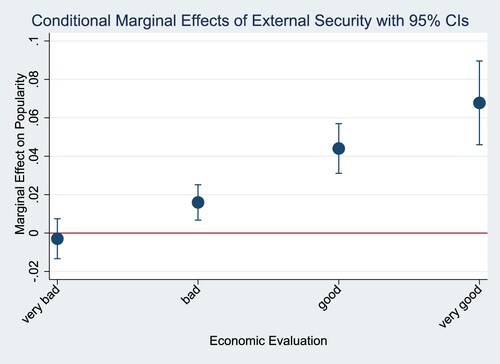

Yet to fully understand the interaction effects, we need to see the impact of security concerns for each of the four values of economic evaluation from “very bad” to “very good.” shows the marginal effects of external security concern on predicted values of government satisfaction depending on values of economic evaluation. We see that as economic evaluation improves, the positive impact of external security concern increases. As hypothesized (H3), the interaction of positive economic evaluation and external security has a positive impact on support for government. The marginal effect of “very good” economic evaluation is more than 6 percentage points, and the effect of “good” economic evaluation is more than 4 percentage points. The positive impact of external security concern continues to decline for the two lower categories of economic evaluation. While the marginal effect of “bad” economic evaluation and external security is still positive and significant, it is not significant for the lowest category (“very bad”).

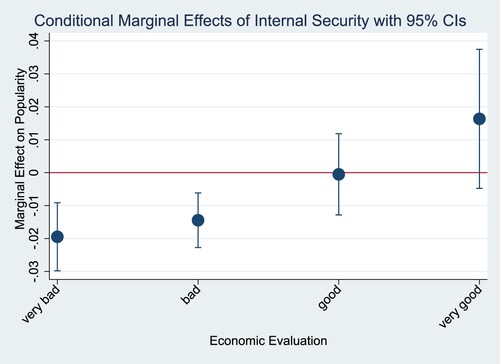

shows the marginal effects of internal security concern on predicted values of government satisfaction, depending on values of economic evaluation. We see that as economic evaluation worsens the negative impact of internal security concern increases. As expected (H4), the interaction of low economic evaluation and internal security has a negative impact on government popularity. The marginal effect of “bad” economic evaluation is more than 1 percentage point, and the effect of “very bad” economic evaluation is about 2 percentage points. The marginal effect for the two positive categories of economic evaluation is not significant.

Overall we see that while the two types of security concern – internal and external – had an effect on satisfaction with the government, we learn from the interaction models that this effect is dependent on economic evaluations. The impacts of security concerns are strongest when they are aligned with current evaluations of the economic situation in the country. These results suggest that individuals in the Arab World can partly address the challenge of holding the government accountable for security issues by incorporating their evaluations of a different policy domain. That is, citizens infer about the government's competence and policy effectiveness in the security domain from information they have from the economic domain.

Conclusion

In this study, we identified the main components of the popularity function in the Arab World. We found that, overall, citizens can hold the government accountable based on their evaluation of policy outcomes. This finding is consistent with the literature on popularity in other regions, democratic and non-democratic alike. More specifically, the economy and security play a major role in shaping individuals’ support for their government. This study reinforces the link between evaluation of policy performance and support for the incumbent that studies on the Arab World have been more systematically investigating in recent decades.Footnote94 Moreover, following the Arab Uprisings, debates over basic questions, such as “what is security?” and “security for whom?” have taken centre stage in studies on Middle East International Relations.Footnote95 Our study extends this discussion not only by emphasizing, similar to BilginFootnote96 that “[d]ifferent people … have different ideas as to … what they find threatening,” but also by demonstrating how these perceptions of security threats shape political preferences.

While previous studies on government popularity in non-democratic countries mostly focus on the impact of the economy, this study shows the importance of security issues. More specifically, it demonstrates that the conventional scholarly wisdom that external security and internal security have distinct impacts on popularity, holds beyond the context of advanced democracies. Being concerned about threats that have an international component, which increases salience of the nation-state, is associated with supporting the government. Concerns about internal threats, where social and political divisions within the state are more salient, are associated with government disapproval.

Our findings further show that evaluations of security and economic issues interact in shaping government popularity. Individuals can become more certain in their evaluation of the executive by relying on two different policy issues. For this process to occur, the two issues need to provide similar information about whether the government should be rewarded or punished. Citizens who think that external security threats are a major national challenge are more likely to support the incumbent if they also think the economy is doing well. Those who are worried about internal security threats are more likely to be dissatisfied with the government if they also think the economy is doing badly.

Beyond establishing a popularity function in the context of the Arab World, the findings make two additional contributions. First, the literature on government popularity has long acknowledged the instability in the coefficients of economic and security indicators.Footnote97 This study suggests an explanation for variation in the impact of security issues. Distinguishing between internal and external security issues enables us to capture the full impact of security issues on government popularity. In addition, the study demonstrates that even when citizens are concerned with security threats, they may consider other factors before deciding whether to reward or punish the government. Second, the findings suggest that issues are not necessarily in competition with one another for citizens’ attention. Pundits and researchers often ask the question of whether it is the economy or security that shapes support for the incumbent.Footnote98 This study shows that the salience of one issue does not have to come at the expense of another, but rather that both issues can shape evaluation of the government together.

Further research would be beneficial in two key areas. First, testing these results in additional regions where both the economy and security play a major role would be valuable. In addition, future research can take a closer look at which types of foreign interference and domestic safety issues are most likely to generate a change in political support, as well as how social identities inform perceptions of security concern.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ryan Carlin and Charles Ostrom for valuable comments on the article. We would also like to express our gratitude to our colleagues at the School of Politics and International Relations at the Australian National University for exceptionally useful guidance on an earlier draft. We are indebted to the reviewers of the article for astute comments that helped us craft this into a stronger piece of work. As always, any errors remain ours alone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alon P. Kraitzman

Alon P. Kraitzman is a visiting researcher at the School of Politics and International Relations, at the Australian National University. His research interests lie in political behaviour, public opinion, and political institutions.

Jessica Genauer

Jessica Genauer is a Senior Lecturer in International Relations at Flinders University. Jessica's research focuses on conflict, threat perceptions, and post-conflict institution-building.

Notes

1 Carlin and Singh, “Executive Power and Economic Accountability.”; Dahl, Democracy and its Critics; Powell, Elections as Instruments of Democracy.

2 Carlin et al., “Cushioning the Fall”; Gronke and Newman, “FDR to Clinton, Mueller to?”; Tir and Singh, “Is It the Economy or Foreign Policy, Stupid?”

3 Stegmaier et al., The VP-Function: A Review.

4 E.g. Lewis-Beck et al., “A Chinese Popularity Function.”; Treisman, “Presidential Popularity in a Hybrid Regime.”

5 E.g. Bojar et al., “The Effect of Austerity Packages.”; Coffey, “Pain Tolerance.”

6 Carlin and Hunt, “Peasants, Bankers, or Piggybankers?”; Pignataro, “Lealtad y castigo.”

7 Di Lonardo et al., “Autocratic Stability in the Shadow of Foreign Threats.”

8 Newman and Forcehimes, ““Rally Round the Flag” Events for Presidential Approval Research.”; Ostrom and Simon, “Promise and Performance.”

9 Nannestad and Paldam, “The VP-function.”

10 Cioffi-Revilla, Politics and Uncertainty.

11 Nalepa et al., “Authoritarian Backsliding.”; Shadmehr and Bernhardt, “Collective Action with Uncertain Payoffs.”

12 Hellwig, “Economic Openness, Policy Uncertainty.”

13 Bellucci and Lewis-Beck, “A Stable Popularity Function?.”; Gélineau, “Electoral Accountability in the Developing World.”

14 Cammett et al., “Insecurity and Political Values in the Arab world.”

15 Josua and Edel, “The Arab Uprisings and the Return of Repression.”

16 Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, “Economic Voting.”; Treisman, “Presidential Popularity in a Hybrid Regime.”

17 Feinstein, Rally 'Round the Flag.

18 E.g. Carlin et al., “Security, Clarity of Responsibility.”; Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, “The VP-function Revisited.”

19 Lewis-Beck et al., “A Chinese Popularity Function.”; Stegmaier et al., The VP-Function.; Treisman, “Presidential Popularity in a Hybrid Regime.”

20 Gandhi and Lust-Okar, “Elections Under Authoritarianism.”

21 Gélineau, “Electoral Accountability in the Developing World,” 423.

22 Newman and Forcehimes, “Rally Round the Flag.”; Willer, “The Effects of Government-Issued Terror.”

23 Kraitzman and Ostrom, “The Impact of Governmental Characteristics on Prime Ministers’ Popularity Ratings.”

24 Stegmaier et al., The VP-Function: A Review.

25 E.g. Hale, “How Crimea Pays.” Treisman, “Presidential Popularity in a Hybrid Regime.”

26 E.g. Bellucci and Lewis-Beck, “A Stable Popularity Function?”; Ostrom et al., “Polls and Elections.”

27 Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, “Economic Determinants of Electoral Outcomes,” 186.

28 Gelpi, “Cost of War-How Many Casualties Will Americans Tolerate-Misdiagnosis.”

29 Tir and Singh, “Is It the Economy or Foreign Policy, Stupid?”

30 Ibid.

31 Russett, “Economic Decline, Electoral Pressure.”; Tir and Jasinski, “Domestic-Level Diversionary Theory of War.”

32 Mueller, “Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson.”

33 Ibid, 21.

34 Chowanietz, “Rallying Around the Flag.”; Holman et al., “The Curious Case of Theresa May.”

35 Corbacho et al., “Crime and Erosion of Trust.”

36 Clarke et al., “Politics, Economics and Party Popularity in Britain, 1979–83.”

37 Carlin et al., “Security, Clarity of Responsibility, and Presidential Approval.” Carlin et al., “Presidents’ Sex and Popularity: Baselines, Dynamics and Policy Performance.”

38 Simon and Ostrom, “The Impact of Televised Speeches.”

39 Just et al., “Follow the Leader.”; Newman and Forcehimes, “Rally Round the Flag.”

40 Kam and Ramos, “Joining and Leaving the Rally.”

41 Brewer, “When Contact is Not Enough,” 294.

42 E.g. Chau et al., “Political Uncertainty and Stock Market Volatility.”; Mohamed, “The Arising Uncertainties from Democratization Process.”; Uyangoda, “Sri Lanka in 2009.”

43 Lupu and Riedl, “Political Parties and Uncertainty in Developing Democracies.”

44 Cioffi-Revilla, Politics and Uncertainty.

45 Gill, “An Entropy Measure of Uncertainty in Vote Choice.”

46 Carmignani, “Political Instability, Uncertainty and Economics.”

47 Van Dalen et al., “Mediated Uncertainty,” 711.

48 Hellwig, “Economic Openness, Policy Uncertainty.”

49 Johnson and Scicchitano, “Uncertainty, Risk, Trust, and Information.”; Lupu and Riedl, “Political Parties and Uncertainty in Developing Democracies.”; Porter, “Taking uncertainty seriously.”

50 Nalepa et al., “Authoritarian Backsliding.”

51 Guriev and Treisman, Spin Dictators. It is important to note that even democratic politicians' public relations efforts can sometimes resemble state propaganda. As noted by Guriev and Treisman (“Informational autocrats.”) in some regimes the distinction between “low-quality democracy and informational autocracy is fuzzy”.

52 Shadmehr and Bernhardt, “State Censorship.”

53 Shadmehr and Bernhardt, “Collective Action with Uncertain Payoffs,” 829.

54 Levy and Razin, “Correlation Neglect, Voting Behavior.”; Lupia, “Shortcuts Versus Encyclopedias.”

55 Glasgow and Alvarez, “Uncertainty and Candidate Personality Traits.”

56 Edwards et al., “Explaining Presidential Approval.”; Ostrom et al., “Polls and Elections.”

57 Alesina and Rosenthal, Partisan Politics, Divided Government; Duch and Stevenson, The Economic Vote. As noted by Aytaç (“Relative Economic Performance and the Incumbent Vote: A Reference Point Theory.”), the emphasis in this approach is on how the context affects the “competence signal”. In previous studies this has been conceptualized as the information about the competence of the incumbent that citizens can extract from economic conditions. In this study, we follow this logic and examine how information can be extracted across issues to evaluate the incumbent.

58 Gélineau, “Electoral Accountability in the Developing World.”; Stegmaier et al., The VP-Function.

59 Bellin, “The Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East.”; Bank et al., Authoritarianism Reconfigured.

60 Al-Ali, The Struggle for Iraq's Future; Brownlee et al., The Arab Spring; Isakhan et al., “Introduction.”; Napoleoni, The Islamist Phoenix.

61 Abadeer et al., “Did Egypt’s Post-Uprising Crime Wave.”

62 Murthy, “United Nations and the Arab Spring.”

63 David, “Explaining Third World Alignment.”; Gause, “Balancing What?.”; Hazbun, “A History of Insecurity.”

64 Darwich et al., International Relations and Regional (In)security; Gause, “Saudi Arabia’s Regional Security Strategy.”; Ryan, “Shifting Alliances and Shifting Theories in the Middle East,” 87.

65 Kam and Ramos, “Joining and Leaving the Rally.”; Lynch et al., “Online Clustering, Fear and Uncertainty.”

66 Mohamed, “The Arising Uncertainties from Democratization Process,” 443.

67 Stacher, “Fragmenting States, New Regimes,” 260.

68 Hinnebusch, “Introduction,” 206.

69 Arayssi et al., “Did the Arab Spring Reduce?.”; Chau et al., “Political Uncertainty and Stock Market.”; Tanyeri et al., “The Stock and CDS Market Consequences.”

70 Klocek et al., “Regime Change and Religious Discrimination.”

71 Tchaïcha and Arfaoui, “Tunisian Women in the Twenty-First Century.”

72 Danju et al., “From Autocracy to Democracy.”; Rezaei, “The Role of Social Media.”; Shirazi, “Social Media and the Social Movements.” Volpi and Clark, Activism in the Middle East.

73 Blaydes et al., “Authoritarian Media and Diversionary Threats.”; Topak et al., New Authoritarian Practices.

74 Josua and Edel, “The Arab Uprisings and the Return of Repression.”; Stacher, “Fragmenting States, New Regimes.”

75 Even in Tunisia, where a political opening was experienced post-Arab-Uprisings, some “authoritarian practices persist”(Topak et al., New Authoritarian Practices, 9).

76 Allam et al., Between Two Uprisings, 66.

77 Cammett and Luong, “Is there an Islamist Political Advantage?”

78 De Miguel et al., “Elections in the Arab world.”; Gélineau, “Electoral Accountability in the Developing World.”

79 The appendix is available online via FigShare at: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.21994988. While not all Arab states are included in the AB, the surveys cover thirteen states that constitute a majority of countries in the Arab World and provide a range of institutional, political, social and economic settings.

80 Benstead, “Survey Research in the Arab world.”

81 Bellucci and Lewis-Beck, “A Stable Popularity Function?.”; Gélineau, “Electoral Accountability in the Developing World.”

82 Tir and Singh, “Is It the Economy or Foreign Policy, Stupid?”

83 Ibid.

84 On the external-internal continuum, participating perpetrators sometimes cannot be easily identified, which can create ambiguity (e.g. terror attacks linked to the Islamic State group but carried out by local actors). Nevertheless, while for part of the population this ambiguity might endure, others should be able to identify some aspects of the threats as more concerning than others. Stevens and Vaughan-Williams, “Citizens and security threats: Issues, perceptions and consequences beyond the national frame.”

85 Chowanietz, “Rallying Around the Flag.”; Holman et al., “The Curious Case of Theresa May.”

86 Darwich et al., International Relations and Regional (In)security.

87 Gélineau, “Electoral Accountability in the Developing World.”; Kinder and Kiewiet, “Sociotropic Politics.”; Lewis-Beck, Economics and Elections; Lewis-Beck and Stegmaier, “Economic Determinants of Electoral Outcomes.”

88 Anderson, “Economic Voting and Political Context.”; De Miguel et al., “Elections in the Arab World.”; Tir and Singh, “Is It the Economy or Foreign Policy, Stupid?.”

89 Brownlee et al., The Arab Spring; Gélineau, “Electoral Accountability in the Developing World.”

90 Similar to Tir and Singh's study (“Is It the Economy or Foreign Policy, Stupid? The Impact of Foreign Crises on Leader Support.”), which found that international crisis triggers foreign policy concerns, our preliminary analyses show that the three main independent variables of this study are significantly shaped by real-world conditions: concerns with foreign interference are stimulated by the impact of external actors on the functioning of the state, as measured by the External Intervention indicator of the Fragile States Index (Appendix Table A3). Also, there is evidence that concerns with internal security are stimulated by domestic security conditions, as measured by the Safety and Security Indicator of The Global Peace Index (Appendix Table A4). Finally, economic evaluations are shaped by economic conditions, as measured by national unemployment (Appendix Table A5).

91 Bellucci and Lewis-Beck, “A Stable Popularity Function?.”

92 Lewis-Beck and Skalaban, “The R-squared.”

93 We also considered models in which the main economic indicators were not included. Yet, the results show that such specification have worse model fit and we do not see the full impact of security issues on government satisfaction (see Appendix Table A7).

94 E.g. De Miguel et al., “Elections in the Arab world.”; Gélineau, “Electoral Accountability in the Developing World.”

95 Darwich et al., International Relations and Regional (In)security.

96 Bilgin, Region, Security, Regional Security, 19.

97 Bellucci and Lewis-Beck, “A Stable Popularity Function?.”; Carlin et al., “Security, Clarity of Responsibility, and Presidential Approval.” Ostrom et al., “Polls and Elections.”

98 Tir and Singh, “Is It the Economy or Foreign Policy, Stupid?”

References

- Abadeer, C., A. D. Blackman, L. Blaydes, and S. Williamson. “Did Egypt’s Post-Uprising Crime Wave Increase Support for Authoritarian Rule?.” Journal of Peace Research 59, no. 4 (2022): 577–592.

- Al-Ali, Z. The Struggle for Iraq's Future. Chap.: Yale University Press, 2017.

- Alesina, A., and H. Rosenthal. Partisan Politics, Divided Government, and the Economy. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Allam, N., C. Berman, K. Clarke, and J. Schwedler. “Between Two Uprisings.” In The Political Science of the Middle East. 62-85: Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Anderson, C. J. “Economic Voting and Political Context: A Comparative Perspective.” Electoral Studies 19, no. 2-3 (2000): 151–170. doi:10.1016/s0261-3794(99)00045-1.

- Arayssi, M., A. Fakih, and N. Haimoun. “Did the Arab Spring Reduce MENA Countries’ Growth?” Applied Economics Letters 26, no. 19 (2019): 1579–1585.

- Aytaç, S. E. “Relative Economic Performance and the Incumbent Vote: A Reference Point Theory.” The Journal of Politics 80, no. 1 (2018): 16–29. doi:10.1086/693908.

- Bank, A., E. Bellin, M. Herb, L. Wedeen, S. Yom, and S. Zerhouni. “Authoritarianism Reconfigured.” In The Political Science of the Middle East. 35-61: Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Bellin, E. “The Robustness of Authoritarianism in the Middle East: Exceptionalism in Comparative Perspective.” Comparative Politics 36, no. 2 (2004): 139. doi:10.2307/4150140.

- Bellucci, P., and M. S. Lewis-Beck. “A Stable Popularity Function? Cross-National Analysis.” European Journal of Political Research 50, no. 2 (2011): 190–211. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01926.x.

- Benstead, L. J. “Survey Research in the Arab World: Challenges and Opportunities.” PS: Political Science \& Politics 51, no. 3 (2018): 535–542.

- Bilgin, P. “Region, Security, Regional Security: “Whose Middle East?” Revisited.” In Regional Insecurity After the Arab Uprisings. 19-39: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015.

- Blaydes, L., et al. “Authoritarian Media and Diversionary Threats: Lessons from 30 Years of Syrian State Discourse.” Political Science Research and Methods 9, no. 4 (2021): 693–708.

- Bojar, A., B. Bremer, H. Kriesi, and C. Wang. “The Effect of Austerity Packages on Government Popularity During the Great Recession.” British Journal of Political Science 52, no. 1 (2021): 181–199. doi:10.1017/s0007123420000472.

- Brewer, M. B. “When Contact is not Enough: Social Identity and Intergroup Cooperation.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 20, no. 3-4 (1996): 291–303.

- Brownlee, J., T. Masoud, and A. Reynolds. The Arab Spring. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Cammett, M., I. Diwan, and I. Vartanova. “Insecurity and Political Values in the Arab World.” Democratization 27, no. 5 (2020): 699–716.

- Cammett, M., and P. J. Luong. “Is There an Islamist Political Advantage?” Annual Review of Political Science (Palo Alto, Calif.) 17 (2014): 187.

- Carlin, R., and K. H. Hunt. “Peasants, Bankers, or Piggybankers? the Economy and Presidential Popularity in Uruguay.” Política 53, no. 1 (2015): 73–93.

- Carlin, R. E., M. Carreras, and G. J. Love. “Presidents’ Sex and Popularity: Baselines, Dynamics and Policy Performance.” British Journal of Political Science 50, no. 4 (2019): 1359–1379. doi:10.1017/s0007123418000364.

- Carlin, R. E., G. J. Love, and C. Martínez-Gallardo. “Security, Clarity of Responsibility, and Presidential Approval.” Comparative Political Studies 48, no. 4 (2014): 438–463. doi:10.1177/0010414014554693.

- Carlin, R. E., G. J. Love, and C. Martnez-Gallardo. “Cushioning the Fall: Scandals, Economic Conditions, and Executive Approval.” Political Behavior 37, no. 1 (2015): 109–130.

- Carlin, R. E., and S. P. Singh. “Executive Power and Economic Accountability.” The Journal of Politics 77, no. 4 (2015): 1031–1044.

- Carmignani, F. “Political Instability, Uncertainty and Economics.” Journal of Economic Surveys 17, no. 1 (2003): 1–54.

- Chau, F., R. Deesomsak, and J. Wang. “Political Uncertainty and Stock Market Volatility in the Middle East and North African (MENA) Countries.” Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 28 (2014): 1–19.

- Chowanietz, C. “Rallying Around the Flag or Railing Against the Government? Political Parties’ Reactions to Terrorist Acts.” Party Politics 17, no. 5 (2010): 673–698. doi:10.1177/1354068809346073.

- Cioffi-Revilla, C. Politics and Uncertainty: Theory, Models and Applications, 1998.

- Clarke, H. D., M. C. Stewart, and G. Zuk. “Politics, Economics and Party Popularity in Britain, 1979–83.” Electoral Studies 5, no. 2 (1986): 123–141. doi:10.1016/0261-3794(86)90002-8.

- Coffey, E. “Pain Tolerance: Economic Voting in the Czech Republic.” Electoral Studies 32, no. 3 (2013): 432–437. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2013.05.011.

- Corbacho, A., J. Philipp, and M. Ruiz-Vega. “Crime and Erosion of Trust: Evidence for Latin America.” World Development 70 (2015): 400–415.

- Dahl, R. A. Democracy and its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

- Danju, I., Y. Maasoglu, and N. Maasoglu. “From Autocracy to Democracy: The Impact of Social Media on the Transformation Process in North Africa and Middle East.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 81 (2013): 678–681.

- Darwich, M., F. G. Gause, W. Hazbun, C. Ryan, and M. Valbjørn. “International Relations and Regional (In)Security.” In The Political Science of the Middle East, 86–107. Oxford University Press, 2022.

- David, S. R. “Explaining Third World Alignment.” World Politics 43, no. 2 (1991): 233–256.

- De Miguel, C., A. A. Jamal, and M. Tessler. “Elections in the Arab World: Why do Citizens Turn out?.” Comparative Political Studies 48, no. 11 (2015): 1355–1388.

- Di Lonardo, L., J. S. Sun, and S. A. Tyson. “Autocratic Stability in the Shadow of Foreign Threats.” American Political Science Review 114, no. 4 (2020): 1247–1265.

- Duch, R. M., and R. T. Stevenson. The Economic Vote. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

- Edwards, G. C., W. Mitchell, and R. Welch. “Explaining Presidential Approval: The Significance of Issue Salience.” American Journal of Political Science 39, no. 1 (1995): 108. doi:10.2307/2111760.

- Feinstein, Y. Rally ‘Round the Flag: The Search for National Honor and Respect in Times of Crisis. Chap.: Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Gandhi, J., and E. Lust-Okar. “Elections Under Authoritarianism.” Annual Review of Political Science 12, no. 1 (2009): 403–422. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.11.060106.095434.

- Gause, F. G. “Balancing What? Threat Perception and Alliance Choice in the Gulf.” Security Studies 13, no. 2 (2003): 273–305.

- Gause, F. G. “Saudi Arabia’s Regional Security Strategy.” International Politics of the Persian Gulf (2011): 169–183.

- Gélineau, F. “Electoral Accountability in the Developing World.” Electoral Studies 32, no. 3 (2013): 418–424. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2013.05.030.

- Gelpi, C. “Cost of War-How Many Casualties Will Americans Tolerate-Misdiagnosis.” Foreign Affairs (council. on Foreign Relations) 85 (2006): 139.

- Gill, J. “An Entropy Measure of Uncertainty in Vote Choice.” Electoral Studies 24, no. 3 (2005): 371–392. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2004.10.009.

- Glasgow, G., and R. M. Alvarez. “Uncertainty and Candidate Personality Traits.” American Politics Quarterly 28, no. 1 (2000): 26–49. doi:10.1177/1532673 ( 00028001002.

- Gronke, P., and B. Newman. “FDR to Clinton, Mueller to?: A Field Essay on Presidential Approval.” Political Research Quarterly 56, no. 4 (2003): 501–512. doi:10.1177/106591290305600411.

- Guriev, S., and D. Treisman. “Informational Autocrats.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33, no. 4 (2019): 100–127.

- Guriev, S., and D. Treisman. Spin Dictators. Chap.: Princeton University Press, 2022.

- Hale, H. E. “How Crimea Pays: Media, Rallying ‘Round the Flag, and Authoritarian Support.” Comparative Politics 50, no. 3 (2018): 369–391. doi:10.5129/001041518822704953.

- Hazbun, W. “A History of Insecurity: From the Arab Uprisings to ISIS.” Middle East Policy 22, no. 3 (2015): 55–65.

- Hellwig, T. “Economic Openness, Policy Uncertainty, and the Dynamics of Government Support.” Electoral Studies 26, no. 4 (2007): 772–786. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2007.06.005.

- Hinnebusch, R. “Introduction: Understanding the Consequences of the Arab Uprisings–Starting Points and Divergent Trajectories.” Democratization 22, no. 2 (2015): 205–217.

- Holman, M. R., J. L. Merolla, and E. J. Zechmeister. “The Curious Case of Theresa May and the Public That Did Not Rally: Gendered Reactions to Terrorist Attacks Can Cause Slumps Not Bumps.” American Political Science Review 116, no. 1 (2021): 249–264. doi:10.1017/s0003055421000861.

- Isakhan, B., F. Mansouri, and S. Akbarzadeh. “Introduction: People Power and the Arab Revolutions: Towards a new Conceptual Framework of Democracy in the Middle East.” The Arab Revolutions in Context: Civil Society and Democracy in a Changing Middle East (2012): 1–20.

- Johnson, R. J., and M. J. Scicchitano. “Uncertainty, Risk, Trust, and Information: Public Perceptions of Environmental Issues and Willingness to Take Action.” Policy Studies Journal 28, no. 3 (2000): 633–647. doi:10.1111/j.1541-0072.2000.tb02052.x.

- Josua, M., and M. Edel. “The Arab Uprisings and the Return of Repression.” Mediterranean Politics 26, no. 5 (2021): 586–611.

- Just, M. R., P. Brace, and B. Hinckley. “Follow the Leader: Opinion Polls and the Modern Presidents.” Political Science Quarterly 108, no. 2 (1993): 362. doi:10.2307/2152037.

- Kam, C. D., and J. M. Ramos. “Joining and Leaving the Rally: Understanding the Surge and Decline in Presidential Approval Following 9/11.” Public Opinion Quarterly 72, no. 4 (2008): 619–650. doi:10.1093/poq/nfn055.

- Kinder, D. R., and D. R. Kiewiet. “Sociotropic Politics: The American Case.” British Journal of Political Science 11, no. 2 (1981): 129–161. doi:10.1017/s0007123400002544.

- Klocek, J., H. J. Ha, and N. G. Sumaktoyo. “Regime Change and Religious Discrimination After the Arab Uprisings.” Journal of Peace Research (2022. doi:10.1177/00223433221085894.

- Kraitzman, A. P., and C. W. Ostrom. “The Impact of Governmental Characteristics on Prime Ministers’ Popularity Ratings: Evidence from Israel.” Political Behavior (2021): 1–26.

- Levy, G., and R. Razin. “Correlation Neglect, Voting Behavior, and Information Aggregation.” American Economic Review 105, no. 4 (2015): 1634–1645. doi:10.1257/aer.20140134.

- Lewis-Beck, M. Economics and Elections. University of Michigan Press, 1990.

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., and A. Skalaban. “The R-Squared: Some Straight Talk.” Political Analysis 2 (1990): 153–171.

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., and M. Stegmaier. “Economic Determinants of Electoral Outcomes.” Annual Review of Political Science 3, no. 1 (2000): 183–219. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.3.1.183.

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., and M. Stegmaier. “Economic Voting.” The Oxford Handbook of Public Choice 1 (2018): 247–265.

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., and M. Stegmaier. “The VP-Function Revisited: A Survey of the Literature on Vote and Popularity Functions After Over 40 Years.” Public Choice 157, no. 3-4 (2013): 367–385. doi:10.1007/s11127-013-0086-6.

- Lewis-Beck, M. S., W. Tang, and N. F. Martini. “A Chinese Popularity Function.” Political Research Quarterly 67, no. 1 (2013): 16–25. doi:10.1177/1065912913486196.

- Lupia, A. “Shortcuts Versus Encyclopedias: Information and Voting Behavior in California Insurance Reform Elections.” American Political Science Review 88, no. 1 (1994): 63–76. doi:10.2307/2944882.

- Lupu, N., and R. B. Riedl. “Political Parties and Uncertainty in Developing Democracies.” Comparative Political Studies 46, no. 11 (2012): 1339–1365. doi:10.1177/0010414012453445.

- Lynch, M., D. Freelon, and S. Aday. “Online Clustering, Fear and Uncertainty in Egypt’s Transition.” Democratization 24, no. 6 (2017): 1159–1177.

- Mohamed, K. “The Arising Uncertainties from Democratization Process in Arab Spring Countries.” Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 4, no. 10 (2013): 443–443.

- Mueller, J. E. “Presidential Popularity from Truman to Johnson.” American Political Science Review 64, no. 1 (1970): 18–34. doi:10.2307/1955610.

- Murthy, C. “United Nations and the Arab Spring: Role in Libya, Syria, and Yemen.” Contemporary Review of the Middle East 5, no. 2 (2018): 116–136.

- Nalepa, M., G. Vanberg, and C. Chiopris. “Authoritarian Backsliding.” Unpublished manuscript, University of Chicago and Duke University, 2018.

- Nannestad, P., and M. Paldam. “The VP-Function: A Survey of the Literature on Vote and Popularity Functions After 25 Years.” Public Choice 79, no. 3 (1994): 213–245.

- Napoleoni, L. The Islamist Phoenix: The Islamic State (ISIS) and the Redrawing of the Middle East. Seven Stories Press, 2014.

- Newman, B., and A. Forcehimes. ““Rally Round the Flag” Events for Presidential Approval Research.” Electoral Studies 29, no. 1 (2010): 144–154. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2009.07.003.

- Ostrom, C. W., A. P. Kraitzman, B. Newman, and P. R. Abramson. “Polls and Elections: Terror, War, and the Economy in George W. Bush's Approval Ratings: The Importance of Salience in Presidential Approval.” Presidential Studies Quarterly 48, no. 2 (2017): 318–341. doi:10.1111/psq.12415.

- Ostrom, C. W., and D. M. Simon. “Promise and Performance: A Dynamic Model of Presidential Popularity.” American Political Science Review 79, no. 2 (1985): 334–358. doi:10.2307/1956653.

- Pignataro, A. “Lealtad y Castigo: Comportamiento Electoral en Costa Rica.” Revista Uruguaya de Ciencia Política 26, no. 2 (2017. doi:10.26851/rucp.v26n2.1.

- Porter, P. “Taking Uncertainty Seriously: Classical Realism and National Security.” European Journal of International Security 1, no. 2 (2016): 239–260. doi:10.1017/eis.2016.4.

- Powell, G. B. Elections as Instruments of Democracy: Majoritarian and Proportional Visions. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000.

- Rezaei, F. “The Role of Social Media in the Recent Political Shifts in the Middle East and North Africa.” IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 4, no. 6 (2012): 1–10. doi:10.9790/0837-0460110.

- Russett, B. “Economic Decline, Electoral Pressure, and the Initiation of Interstate Conflict.” Prisoners of war (1990): 123–140.

- Ryan, C. R. “Shifting Alliances and Shifting Theories in the Middle East.” Shifting Global Politics and the Middle East 7 (2019.

- Shadmehr, M., and D. Bernhardt. “Collective Action with Uncertain Payoffs: Coordination, Public Signals, and Punishment Dilemmas.” American Political Science Review 105, no. 4 (2011): 829–851. doi:10.1017/s0003055411000359.

- Shadmehr, M., and D. Bernhardt. “State Censorship.” American Economic Journal: Microeconomics 7, no. 2 (2015): 280–307.

- Shirazi, F. “Social Media and the Social Movements in the Middle East and North Africa.” Information Technology & People 26, no. 1 (2013): 28–49. doi:10.1108/09593841311307123.

- Simon, D. M., and J. C. W. Ostrom. “The Impact of Televised Speeches and Foreign Travel on Presidential Approval.” Public Opinion Quarterly 53, no. 1 (1989): 58. doi:10.1086/269141.

- Stacher, J. “Fragmenting States, new Regimes: Militarized State Violence and Transition in the Middle East.” Democratization 22, no. 2 (2015): 259–275.

- Stegmaier, M., M. S. Lewis-Beck, and B. Park. “The VP-Function: A Review.” In The SAGE Handbook of Electoral Behaviour: Volume 2, 584–605. SAGE Publications Ltd, 2017.

- Stevens, D., and N. Vaughan-Williams. “Citizens and Security Threats: Issues, Perceptions and Consequences Beyond the National Frame.” British Journal of Political Science 46, no. 1 (2016): 149–175.

- Tanyeri, B., T. Savaser, and N. Usul. “The Stock and CDS Market Consequences of Political Uncertainty: The Arab Spring.” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 58, no. 7 (2022): 1821–1837.

- Tchaïcha, J. D., and K. Arfaoui. “Tunisian Women in the Twenty-First Century: Past Achievements and Present Uncertainties in the Wake of the Jasmine Revolution.” The Journal of North African Studies 17, no. 2 (2012): 215–238. doi:10.1080/13629387.2011.630499.

- Tir, J., and M. Jasinski. “Domestic-Level Diversionary Theory of War.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 52, no. 5 (2008): 641–664. doi:10.1177/0022002708318565.

- Tir, J., and S. P. Singh. “Is It the Economy or Foreign Policy, Stupid? The Impact of Foreign Crises on Leader Support.” Comparative Politics 46, no. 1 (2013): 83–101. doi:10.5129/001041513807709374.

- Topak, Z. E., M. Merouan, and C. Francesco. New Authoritarian Practices in the Middle East and North Africa, 2022.

- Treisman, D. “Presidential Popularity in a Hybrid Regime: Russia Under Yeltsin and Putin.” American Journal of Political Science 55, no. 3 (2011): 590–609. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2010.00500.x.

- Uyangoda, J. “Sri Lanka in 2009: From Civil war to Political Uncertainties.” Asian Survey 50, no. 1 (2010): 104–111.

- Valentino, N. A. “Crime News and the Priming of Racial Attitudes During Evaluations of the President.” Public Opinion Quarterly (1999): 293–320.

- Van Dalen, A., C. H. De Vreese, and E. AlbÆk. “Mediated Uncertainty.” Public Opinion Quarterly (2016. doi:10.1093/poq/nfw039.

- Volpi, F., and J. A. Clark. “Activism in the Middle East and North Africa in Times of Upheaval: Social Networks’ Actions and Interactions.” In Network Mobilization Dynamics in Uncertain Times in the Middle East and North Africa, 1–16. Routledge, 2020.

- Willer, R. “The Effects of Government-Issued Terror Warnings on Presidential Approval Ratings.” Current Research in Social Psychology 10, no. 1 (2004): 1–12.

Appendix

Table A1: List of cases

Table A2: Descriptive Statistics

Table A3: Does an increase in the impact of external actors on the functioning of the state lead citizens to be more concerned with foreign interference?

Table A4: Does an increase in national safety and security problems lead citizens to be more concerned with internal stability and security?

Table A5: Does an increase in national unemployment lead citizens to give lower evaluation of the economy?

Table A6: Description of Control Variables

Table A7: The Impacts of Security Concerns on Government Support: without economic indicators