ABSTRACT

When backsliding occurs at the hands of populist presidents who were elected in landslide elections, producing dominant executives with few institutional checks and weak opposition parties, should we blame the decline in democracy on their populist ideology, their presidential powers, or their parties’ dominance in the legislature? The literature on democratic backsliding has mostly arrived at a consensus on what backsliding entails and collectively has revealed its growing prevalence around the globe. Yet, scholars have not settled on causal explanations for this phenomenon. We assess the evidence for recent ideology-centered arguments for democratic backsliding relative to previous institutional arguments among all democratically elected executives serving in all regions of the world since 1970. We use newly available datasets on populist leaders and parties to evaluate the danger of populists in government, and we employ matching methods to distinguish the effects of populist executives, presidents as chief executives, and dominant executives on the extent of decline in liberal democracy.

Did democracy in Venezuela slide backwards under Hugo Chavez because of this former leader’s populist worldview or because he was able to evade checks on his power as a president whose government was not subject to parliamentary confidence? Did democracy decline in Hungary because Viktor Orbán is a populist or because his Fidesz party won a supermajority that allowed it to alter the constitution and modify the rules in its favour? The same question is relevant in other countries where backsliding occurred at the hands of populist executives, both presidents and prime ministers, who controlled supermajorities. Yet we cannot answer this question if we only study such infamous cases of decline that make front-page news.

By studying cases of democratic backsliding, scholars reveal the process by which backsliding unfolds when and where it does.Footnote1 Approaching the study of democratic backsliding from a different angle, we want to know how much backsliding, on average, can be attributed to certain causes. By analysing the full range of potential cases, we assess the evidence for recent leadership-centred arguments for democratic backsliding relative to previous institutional arguments for democratic instability. Research on democratic backsliding emphasizes leaders’ values, norms and skills.Footnote2 This work melds with scholarship on populism that recognizes the ambivalent relationship between populism and liberal democracy.Footnote3 The synthesis of these two literatures suggests that populist leaders’ ideology predisposes them to democratic backsliding.Footnote4 Previous research in comparative political institutions links presidential democracies to various forms of political instability and previous studies of backsliding episodes highlight how executives’ legislative dominance facilitated their power grabs.Footnote5

In this article, we use newly available datasets on populist leaders and parties to evaluate the danger of populists in government, both as presidents and as prime ministers, while paying attention to the fact that some of these leaders are elected in landslide elections or under disproportionate electoral rules that produce very powerful governments with few institutional checks and weak opposition parties. Using matching methods, we distinguish the effects of populists, presidents, and dominant executives on the decline in democracy under democratic governments serving in all regions of the world since 1970. Our results provide evidence that populists, apart from their institutional position or the institutional means at their disposal, are to blame for democratic backsliding.

We organize the article as follows. In the next section, we provide a brief descriptive overview of the extent of democratic backsliding in our analysis, noting how it compares to previous research. We then use previous research to explain why we expect populists, presidents, and dominant executives to engage in democratic backsliding to a greater extent than non-populists, prime ministers, and executives without supermajorities, respectively. In the subsequent section, we explain our dataset in detail and the matching methods we employ in our analysis. We follow this with a section presenting our results, along with balance assessments. Finally, we conclude the article.

How widespread is backsliding?

“The term democratic backsliding … denotes the state-led debilitation or elimination of any of the political institutions that sustain an existing democracy.”Footnote6 Retaining Bermeo’s definition, we limit the scope of democratic backsliding to settings that were democratic to begin with, distinguishing these declines in democracy from autocratization or authoritarian backsliding.Footnote7 Her definition implies endogenous, rather than exogenous, decay in democracy, at the hands of incumbent governments, opposition politicians, or other veto players.Footnote8 However, while Bermeo describes several varieties of democratic backsliding, we use the term only to refer to the forms she identifies as executive aggrandizement and strategic electoral manipulation. In other words, we separate out the abrupt collapse of democracy due to military coups or autogolpes from the intentional but incremental “institutional changes that hamper the power of opposition forces to challenge executive preferences” and “actions aimed at tilting the electoral playing field in favour of the incumbent.”Footnote9

With this conceptualization, democratic backsliding results in a loss in the quality of liberal democracy. Liberal democracy, by definition, limits freely and fairly elected governments and holds them accountable. To measure the degradation in liberal democracy, we use the Liberal Democracy Index (LDI) from the Varieties of Democracy project.Footnote10 This index adds the protection of civil liberties, legislative constraints on the executive and judicial constraints on the executive to the underlying Electoral Democracy Index, which is based on Robert Dahl’s criteria for polyarchy.Footnote11

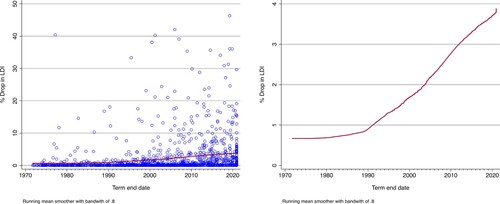

We assess democratic backsliding during executive-legislative terms, relying on “signal events,” such as a new chief executive or an election, to define our start and end points, instead of annual data.Footnote12 Between January 1, 1970 and December 31, 2020, we record 1358 terms, across 98 countries, that were occupied by 856 executives who were elected in democratic elections or who assumed office under democracy. Although our unit of analysis differs, like other studies, we find an increasing global trend in democratic backsliding over time, as reveals.Footnote13 This trend is consistent with research that points to the vulnerability of “third-wave” democracies to backsliding.Footnote14

While we only include terms that come to power democratically, we measure the full extent of decline during each term – even if that takes the regime below the threshold for democracy. We measure how much backsliding occurs as a percentage drop in the LDI, such that higher initial values give liberal democracy more room to fall before sliding into authoritarianism.Footnote15 For example, the drop of .181 in Venezuela during Chavez’s first term from February 1999 to August 2000 amounts to 38% of the LDI score in Venezuela when Chavez assumed office (.475), whereas a similar-sized drop of .163 in Hungary during Orbán’s term from May 2010 to April 2014 was “just” 24% of the LDI score in Hungary when Orbán assumed office in 2010 (.679).

In , we show the terms for which we record declines of more than 20%, prior to any coups or self-coups that terminated democracy instantaneously. In some of these rare cases democracy ends tout court, as happened eventually under Chavez in Venezuela, Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in Turkey, for example. In other cases, democratic backsliding is followed by democratic collapse, due to military coups, as under Thaksin Shinawatra in Thailand or Marc Ravalomanana in Madagascar. Yet, during 50.7% of terms, liberal democracy did not decline at all, and for another 21.5% of terms, the drop in liberal democracy was less than one percent of its starting value.Footnote16 We are precisely interested in how much democratic backsliding occurs, on average, across executives who came to power through democratic means, including but not limited to the infamous backsliders listed in . Thus, we expand the focus of inquiry to all cases, and also to potential cases for which no backsliding was detected.

Table 1. Cases of extreme democratic backsliding.

What causes backsliding?

Scholars identify, describe, and draw “bright lines” to warn us of the dangers of democratic backsliding in the scholarly literature and beyond.Footnote17 Yet there is less consensus on explanations for democratic backsliding.Footnote18 While we find a wide range of theories, they are largely untested because scholars have mostly selected on the dependent variable when examining democratic backsliding. Some of the “causes” proposed in the literature can be empirically tested, while claims that “weakly institutionalized horizontal accountability and civil and political liberties are causes of democratic reversal come close to being tautological,” as David Anderson contends.Footnote19

In their oft-cited review of democratic backsliding research, David Waldner and Ellen Lust “evaluate existing theories in terms of their utility for explaining outcomes related to but distinct from the classic debate on transitions to and from democracy.”Footnote20 They consider political agency, political institutions, and structural theories, among others, and remind us that “the causes of vulnerability to backsliding may be distinct from the proximate causes of particular instantiations of backsliding.”Footnote21 On the more proximate end of the causal spectrum, agent-based explanations for democratic backsliding, or lack thereof, emphasize leaders’ normative preference for democracy and willingness to practice tolerance and forbearance.Footnote22 Dismantling democracy also requires nerve and skill, or “political craft.”Footnote23 On the other end, we find structural theories that propose that higher levels of development prevent backslides.Footnote24 Scholars also point to international factors to explain domestic trends in democracy.Footnote25

In this article we consider causal explanations that fall somewhere in between individuals and structures. With our broad scope of countries but restricted temporal unit of analysis (the executive-legislative term), personalities are too idiosyncratic and structures are too stable to account for the varied extent of backsliding across the observations in our dataset. Instead, we identify characteristics of national executives (presidents or prime ministers) specifically that make it more likely that backsliding will occur on their watch. In doing so, we draw implications with respect to backsliding from broader discussions about liberal democracy and executive-legislative relations. Scholars have argued that populism provides executives with ideological motivation for anti-democratic infringements, presidential systems create institutional incentives for executives’ power grabs, and supermajorities reduce legislative checks on executives. We test each of these claims, but do not propose them as a complete explanation for democratic backsliding. Moreover, being a populist, holding presidential powers or enjoying legislative dominance are not mutually exclusive traits of executives. With potential additive effects, we hypothesize that each one will, on average, increase the amount of democratic backsliding that occurs during an executive-legislative term.

Populism provides ideological motivation

We rely on an ideational definition of populism, explained as a thin-centred ideology that pits the pure people against the corrupt elites and claims that politics should represent the general will of the people.Footnote26 Unlike traditional “thick” ideologies, populism does not endorse any specific policy content. It does, however, promote a set of ideas that are at odds with those of liberal democracy. Some scholars argue that populism can potentially serve as a corrective to democracy because of its ability to signal the malaise of unrepresented citizens and raise awareness on issues that are not adequately addressed by mainstream politics.Footnote27 Other scholars share a concern that populism presents serious threats to democracy because of its inherently anti-pluralist and illiberal elements.Footnote28

While liberal democracy rests upon a pluralist view of society as consisting of free and equal individuals with competing values and interests, populism identifies a common identity of “the people” and considers the volonté générale as the ultimate source of political authority. Populists derive a Manichean conception of society from a sense of belonging to a “heartland,” an imaginary community with distinct boundaries that separate the good people from those outside.Footnote29 Accordingly, however the heartland is defined, populists exclude and antagonize those who do not belong to it: economic, intellectual, and political elites, often seen as the enemies of common people, as well as marginalized social groups, such as ethnic, religious and sexual minorities.Footnote30 This exclusionary ideology challenges the inspiring principles of liberal democracy, particularly when it comes to the protection of minority rights.

Another source of tension with liberal democracy is populists’ disdain for the complex procedures of representative democracy, which they see as obstacles to the realization of the common good.Footnote31 Populists value unmediated expressions of the popular will, which clash with the logic of checks and balances that limit popular sovereignty and prevent the tyranny of the majority. Populists prefer acclamation over deliberation as the means to express the will of the people and they often turn to strong charismatic leaders that claim to embody the will of the people and who promise to remove all obstacles to the realization of the popular will.Footnote32 They also draw justification for their actions from a sense of enduring emergency, fuelled by the way in which populists frame political competition as an existential struggle between the people and their enemies.

Qualitative and quantitative studies show that populists in power pursue political agendas that undermine the separation of powers, the protection of minority rights, individual freedoms, the rule of law and press freedom.Footnote33 Yet, given that most studies examine a single country or region, it remains difficult to determine from previous research whether it is populists themselves or the circumstances in which they come to power that have a direct effect on democratic backsliding. Recent cross-regional analyses that compare Europe and Latin America provide empirical evidence that populism is associated with lower quality democracy, or with lower levels of some components of democracy, on a country-year basis.Footnote34 As we detail in the Research Design section below, our analysis employs a different unit of analysis and extends both the geographical scope and the time frame.

Presidentialism creates institutional incentives

Since the third wave of democratization that brought about many new presidential democracies, scholars have expected democracy to be less stable under presidential systems of government. While these arguments arose before the backsliding trend, they provide theoretical foundation for explanations of this new form of instability in presidential democracies specifically.

Drawing from the classic “perils of presidentialism,” the greater chances of political outsiders winning presidential elections and the tendency of presidents to personalize politics once in office may explain why democratic backsliding is higher in systems with popularly-elected, powerful presidents.Footnote35 Given that outsiders lack the experience and connections that facilitate working relationships with the legislature, they will attempt to govern unilaterally, with the help of a few cronies.Footnote36 More generally, personalized presidential campaigns and individual presidential authority, which contrasts with the collective responsibility that prime ministers share with their governments, give presidents reason to mould the system so that it works for them personally. Also, the constitutional separation of powers reduces intraparty accountability because “the party that nominated the presidential candidate can no longer hold that person immediately accountable” once they have been elected to office, unlike prime ministers who can be replaced through no confidence procedures.Footnote37

In principle, the checks and balances written into presidential constitutions increase interbranch accountability, thereby constraining executive aggrandizement. However, the lack of institutional solutions to interbranch conflict in presidential systems is a long-standing concern of comparativists.Footnote38 Previous studies led us to expect coups or self-coups since presidents were thought to have only non-democratic means of evading executive-legislative gridlock. Yet, powerful presidents may use their bully pulpit and non-legislative authorities to weaken checks and balances so as to avoid gridlock, which would result in democratic backsliding rather than democratic collapse.Footnote39 For example, recent U.S. presidents have used executive orders to avoid the legislative process and to expand their powers.Footnote40 Presidents may also use political appointments in their attempts to extend their time in office or to prevent impeachment or other challenges that may force them to leave office before their current term is up.Footnote41 To get around his congressional opponents, for instance, Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa decreed a referendum for a constituent assembly, threatened the Supreme Electoral Tribunal to approve the referendum and to depose legislators who opposed its approval, provided backing from the National Police for these moves, dismissed the Constitutional Court, and gained public approval for the constituent assembly that would assume full powers, thereby replacing congress.Footnote42 In sum, the separate origin and survival of the executive in presidential systems incentivizes and empowers presidents to strengthen their position vis-à-vis congress, which takes them down a slippery slope into democratic backsliding.

These theoretical arguments lead us to expect presidents to be more prone to democratic backsliding than prime ministers. We expect that presidents in the president-parliamentary version of semi-presidentialism will also be more likely to usurp power than prime ministers who serve as chief executives in parliamentary or premier-presidential systems. Analysis of a wide range of governance indicators shows that president-parliamentary systems resemble presidential systems, whereas premier-presidential systems have more in common with parliamentary systems.Footnote43

While previous empirical research indicates that presidentialism raises the risk of incumbent takeovers or endogenous termination of democracy, this work did not examine the gradual degradation of democracy (i.e. democratic backsliding), which is different from its outright termination.Footnote44 Other research shows that democratic quality is lower in presidential systems and president-parliamentary systems of government than it is in parliamentary and the premier-presidential form of semi-presidentialism.Footnote45 However, a low level of democracy is not the same thing as a negative change in the level of democracy. To fill this empirical gap, we compare the amount of democratic backsliding under presidents and prime ministers. Moreover, our controlled comparison allows us to determine whether the democratic backsliding that occurs in presidential systems can be attributed to the institutional framework itself, apart from the leader who fills the position and the size of her coalition or other structural conditions correlated with these systems of government.

Supermajorities eliminate legislative constraints

Whether in a presidential, parliamentary, or semi-presidential system of government, having a supportive majority coalition facilitates the executive’s policy agenda and likely reduces horizontal accountability. Supermajority support is qualitatively different: not only do most landslide victories imply mandates for change, but most constitutions also specify a two-thirds threshold for constitutional reform. With a supermajority behind her, an executive can change (in other words, break) the rules of the game. Nevertheless, supermajority governments are outcomes of regular democratic processes, and need not imply democratic backsliding.

The difference between a supermajority government that results in democratic backsliding and a supermajority government that does not comes down to what the executive does with their power. Presidents usually start by abolishing the rules prohibiting their own re-election.Footnote46 For instance, once his MAS party gained two-thirds of the legislative assembly, Bolivian president Evo Morales obtained legislative backing for his third (and eventual fourth) re-election bid. As Omar Sánchez-Sibony details, “The MAS legislative caucus passed laws tailor-made to colonize the judiciary and dominate the mass media ecosystem to build on incumbent advantage at election time, to target independent civil society organizations, or to directly empower the executive more generally.”Footnote47 Similarly, observers of backsliding in Hungary note how the Fidesz supermajority allowed Orbán to change electoral rules in his party’s favour and rewrite the constitution.Footnote48 As Daniel Keleman summarizes, “Through its new 2011 constitution (and subsequent amendments) and Cardinal Laws, the Orbán government has managed to eliminate previous constitutional checks and balances, asserting control over previously independent public bodies that might have checked the government’s power such as the ombudsman for data protection, the National Election Com – mission and the National Media Board.”Footnote49

As these examples illustrate, presidents and prime ministers can use their control of the legislature to gain control of decision-making outside of the legislature – in the judicial branch and other oversight agencies.Footnote50 When an executive lacks a viable opposition in the legislature, other accountability actors that step in to oppose the executive agenda will become the executive’s next opponent.Footnote51 Judges, journalists, or civil society organizations are more vulnerable when the legislative opposition to the president or prime minister is weak.

Case studies of backsliding episodes have revealed the importance of the executive’s control in the legislature.Footnote52 Yet, case studies cannot isolate the effect of supermajorities if they only select cases where democratic backsliding occurred. Moreover, case studies emphasize that the executive’s control over the legislature often increases over the course of the backsliding episode. Pérez-Liñán, Schmidt & Vairo address this endogeneity through an instrumental variable analysis and find that presidential hegemony (including both legislative and judicial control) makes democracy less stable in presidential regimes.Footnote53 Our empirical analysis assesses whether governments that come to power with supermajorities, across all democracies, engage in more backsliding than governments that lack such dominance to begin with.

In summary, our review of the literature leads us to consider arguments centred on ideology as well as arguments about executive-legislative relations to explain why some executives oversee large declines in liberal democracy during their terms in office while most see little if any decline at all. We test the following hypotheses:

All else equal, there will be more democratic backsliding during populist executives’ terms than during non-populist executives’ terms.

All else equal, there will be more democratic backsliding during presidential chief executive’s terms than during prime ministerial chief executives’ terms.

All else equal, there will be more democratic backsliding during dominant executives’ terms than during non-dominant executives’ terms.

Research design

The scope of our analysis includes polities that experienced at least ten consecutive years of democracy since 1970 across all continents, excluding microstates and dependent territories. As mentioned above, we measure changes in the quality of democracy using the Liberal Democracy Index (v2x_libdem) from the V-Dem project. The index, which ranges from 0 to 1, captures the effectiveness of checks and balances and the degree of protection of civil liberties and minority rights. Drawing on the country-date version of the V-Dem dataset, we collect all the LDI scores that have been recorded for each executive-legislative term in our dataset. Each new term is marked by a new executive (or a president’s re-election), a legislative election (including “midterm” elections), or a change in the supermajority status of the government (for governing coalition changes that occur between elections). We then assess democratic backsliding by looking at drops in liberal democracy, which we measure as the difference between the lowest score during each of the terms and the initial score; we convert these drops into percentages relative to the initial scores.

By executive, we refer to the president in countries with presidential and presidential-parliamentary systems and to the prime minister in parliamentary or premier-presidential countries.Footnote54 We identify populist executives based on the Populism Index (v2xpa_popul) from the Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V-Party) dataset, which is computed from two components that address the core conceptual properties of populism, namely anti-elitism and people-centrism. We dichotomize the 0–1 index so that populist executives are defined as those whose party has a score above 0.5. According to this measure, the share of populist leaders in power has doubled since the 1970s and 1980s, with populists leading almost one third of all democratic governments worldwide since 2010.

We derive additional measures of populism from the Votes for Populists (VfP) dataset and the Global Populism Database (GPD). The VfP dataset emphasizes similar components to those used by V-Party: “populism argues that the establishment elites are a corrupt and unresponsive cartel, and that the people need to have their general will represented.”Footnote55 The GPD project measures the level of populism in executive leaders’ speeches, which are assigned a grade from 0, indicating minimal levels of populism, to 2, indicating extremely populist discourses. We rely on a threshold of greater than 0.5, such that chief executives whose speeches are moderately populist are coded as populists.

We collect data on coalitions from various sources that include information on parties’ parliamentary seats, including the ParlGov database, the Database of Political Institutions, and the V-Party dataset. When necessary, we crosscheck parliamentary data using election reports. Based on the seat shares of the government coalition parties, we establish a threshold of 66.67% for supermajorities, as most constitutions require a two-thirds majority to pass major reforms or constitutional changes.

We are interested in the causal effect of populism, presidentialism, and supermajorities on the extent of backsliding that occurs during democratically elected executives’ terms in office. Yet these “treatments” may be simultaneously present for some terms. Since it is impossible to implement an experiment that randomly assigns, for example, a populist executive to some countries in some periods but not others, we use matching to make the distributions of covariates in the “treatment” group and the “control” group approximately equal to each other, and considerably more equal than we find in our raw observational data. Well-matched samples allow us to estimate causal effects with less bias from the covariates.Footnote56

Our goal is to estimate the marginal impact that populism (presidentialism, supermajorities) had, on average, on the amount of backsliding that occurred during populists’ (presidents’; dominant executives’) terms in office. This quantity is referred to as the average treatment effect in the treated (ATET). To estimate it, we use the backsliding that occurred during executives’ terms who took office under conditions that were similar to those where and when populists (presidents, dominant executives) assumed office. To identify these similar executives, we use nearest neighbour matching on covariates.

The key covariates, or alternative treatments, in our analysis are the presence or absence of a populist executive, a presidential chief executive (president), and a dominant executive (supermajority). For these key covariates, all measured as binary indicators, we use exact matching. In addition to these variables of interest, we also include pre-treatment covariates to identify the nearest neighbour matches using Mahalanobis distance.Footnote57 We select covariates that make democratic backsliding more or less likely, and which potentially affect the likelihood that a populist is elected to office or that an executive has supermajority support in the legislature, or which relate to presidential or presidential-parliamentary systems of government. Moreover, we expect that most unobserved covariates would likely correlate with these variables.Footnote58 We measure these variables in the year prior to the executive’s assumption of office as follows:Footnote59

The natural log of population, originally from Clio Infra, but sourced from the V-Dem dataset.Footnote60

Democratic stock refers to the number of years a country has been democratic, in addition to the level of democracy experienced during that period.Footnote61 We use a stock measure that captures the country’s accumulated prior experience with democracy, based on V-Dem’s Electoral Democracy Index, using a one-percent annual depreciation rate and adjusted to fall within a 0–1 interval.Footnote62

Economic growth, sourced from the V-Dem dataset, is a measure of growth based on GDP estimates.Footnote63

Economic globalization assesses the de-facto extent of trade and fiscal integration in the global economy, both over time and across countries.Footnote64 We divide the KOF Economic Globalization Index (De-facto) by 100.

In addition, since term duration ranges from 90 days to over 6 years in our data, we also include the natural log of duration in the nearest neighbour matching.

Endogeneity is an important point of consideration when identifying causes of backsliding, just as it is with many other political outcomes. Theoretically, the question comes down to whether the treatments we identify are in fact related to other unobserved factors that drive democratic backsliding but that are not themselves consequences of these treatments. For example, scholars may describe pernicious political polarization as a cause of democratic backsliding, but polarization is also a strategy – adopted by politicians who are already motivated to accrue more power for themselves – which then prompts reciprocal polarizing tactics from their opposition.Footnote65 That is, “the authoritarian politician … is more the generator of polarization than the product.”Footnote66

Previous empirical research uses quasi-experimental techniques and instrumental variables to show that their findings with respect to the consequences of populism or presidential hegemony on democratic backsliding are robust to endogeneity concerns.Footnote67 Here, we use matching methods, to compare executives that were as similar as possible at the outset of their terms. This means that we do not match on any post-treatment covariates, such as political polarization. After matching, we assume “ignorability,” but we cannot fully rule out the possibility that there are no unobserved differences between the treatment and control groups, conditional on the set of background structural covariates that we observe in our data.Footnote68

Results

In this section, we first report the average treatment effect in the treated (ATET), which is computed by taking the average of the difference between the observed outcome and the potential outcome for each “treated” observation in our dataset using nearest-neighbour matching. We estimate treatment effects for populist executives, presidential chief executives, and dominant executives who control a supermajority in the legislature, as well as the combined effects of populist presidents and dominant populists. In addition to the main effects that we obtain with matching methods, our robustness checks use regression to control for background conditions and contextual variables.

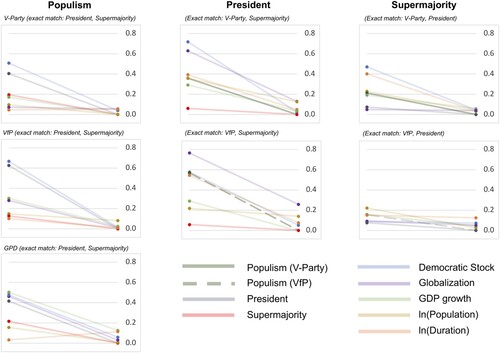

Before we turn to our estimated causal effects, we provide evidence that our research design improves covariate balance as compared to the unmatched data.Footnote69 shows the improvement in balance based on the absolute standardized differences in means. We observe a significant reduction in the mean differences, indicating an acceptable degree of homogeneity in the treatment and control groups after matching.

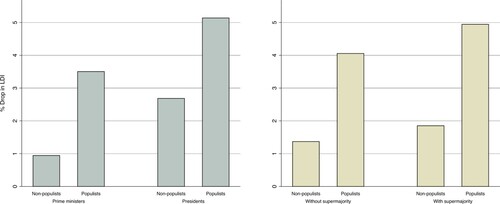

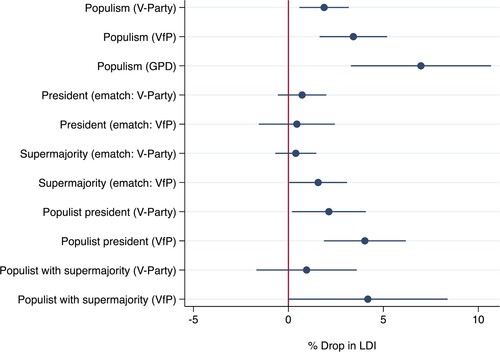

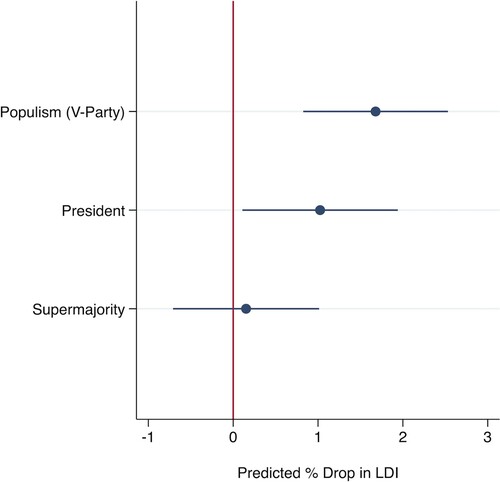

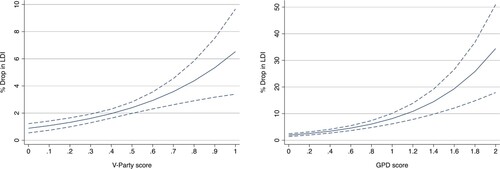

We report the ATET estimates in . Our analyses indicate that populists have a detrimental effect on liberal democracy and these results hold for all measures of populism. The first set of estimates indicate that the percentage drop in the LDI attributed to the populist ideology of the chief executive ranges from 1.88% using the full dataset with the V-Party measure to identify populists to 3.42% using data from VfP to almost 7% when populism is measured for individual leaders using GPD. The negative impact of populism (however defined) is substantial, considering that the amount of decline, if any, is usually in the range of 1–3 percentage points relative to the initial LDI score. The differences in effect magnitude largely depend on the data sample available for each of the three measures of populism. Additional analyses where we estimate the effects for each measure of populism using subsets of cases with no missing values on the other measures generate results that are more consistent in magnitude. These analyses are reported in the supplementary materials alongside cross-sample frequencies and the geographical coverage of each measure.

Table 2. Estimated treatment effects.

When examining the effect of presidents and dominant executives, we match on two of the three populism measures that provide sufficient cases. Contrary to our expectations, our analysis does not uncover statistically significant effects attributed to having a president as chief executive as opposed to a prime minister.Footnote70 As for the effect of having a supermajority in the legislature, the findings depend on which populism measure we employ in the exact matches, and thus the particular subset of cases analysed. With the VfP measure, we find a small positive and significant effect, a result which suggests that democratic backsliding is more likely to occur when executives obtain landslide parliamentary support, be they populists or non-populists and regardless of their position as presidents or prime ministers.

Even if having presidential powers or commanding a supermajority does not significantly increase the amount of backsliding that occurs on an executive’s watch, it may be the case that these factors assist an already motivated populist. As Bakke and Sitter contend, “In order to backslide, power-holders need motive, opportunity, and the absence of constraints” (italic added).Footnote71As the descriptive plots in reveal, empirical patterns in our data show greater amounts of backsliding under populist presidents and under populists with supermajorities. Therefore, we also consider the impact of populism when combined with specific institutional contexts.

We report the ATET for the combined treatment effects in . These estimates show that populist presidents oversee larger declines in democracy as compared to all non-populist presidents and prime ministers, as well as populist prime-ministers. Although we did not find that presidents carry out more backsliding than prime ministers all else being equal, this combined finding indicates that presidentialism can be dangerous if a populist occupies the highest office. In addition, we find more backsliding under dominant populists with supermajorities backing them, but the significance of this combined treatment is limited to populists as identified by the VfP measure. plots our estimates of the combined treatment effects alongside the basic treatment effects reported earlier.

Table 3. Estimated combined treatment effects.

In summary, our results suggest that populism (however identified) has a deleterious impact on the quality of democracy regardless of leaders’ status as presidents or prime ministers and irrespective of the supermajority status of their governments. Although the estimates for supermajorities demand a cautious interpretation, our results suggest some evidence that executive dominance in the legislature provides the means to leaders who seek to consolidate power and rollback liberal democracy. In contrast, we find no support for the argument that presidents cause more harm to democracy than prime ministers. Moreover, our combined effects suggest that populists endanger liberal democracy when they take advantage of their presidential powers or the legislative means at their disposal.

Robustness checks

We obtain similar findings with regard to the relationship between populism and democratic backsliding when we use regression to analyse our observational data. Given the skewed distribution of the dependent variable (non-negative with meaningful zeros), we rely on Poisson regression with robust standard errors clustered by country. First, we include the same variables as those used in our estimates of treatment effects. We employ the three different indicators of populism, as before. We also estimate models using the available continuous variables of populism (V-Party and GPD) and obtain similar findings. The estimate for populism, which is consistent with the treatment effects found using matching methods, is positive, statistically significant and robust to all measures and all model specifications. We find mixed results with respect to the marginal effects of presidents and supermajorities. We show the average marginal effects for our key variables in and and we report the full set of regression results in the supplementary materials. Although the effect of president is significant in the results we show here, it is not significant across all models and data samples that we report in the supplementary materials.

In addition, we replace the democratic stock variable with GDP per capita, as a measure of development, which is highly correlated with it and democracy, and with the initial LDI score – that is, the level of democracy at the start of the executive term – but neither substitution changes our results substantively. Finally, we control for additional political conditions that we did not include as part of our covariates in the nearest neighbour matching. As reported in the supplementary materials, our results indicate that the relationship between populism and democratic backsliding holds even when we take into account additional contextual factors, namely polarized societies, the presence of anti-system opposition movements and the lack of state authority over the national territory.

Conclusion

In this article, we identified populists, presidents and dominant executives as plausible suspects in the search for causal explanations for democratic backsliding around the world. Building on previous literature on executive aggrandizement, as well as earlier studies of democratic stability, we argued that ideology and institutional contexts may concomitantly act as contributing factors to democratic decline by providing executives with motivation and means. We compiled an original dataset of democratically elected executives since 1970, merged V-Dem data on the quality of liberal democracy with newly available measures of populism, and collected information on coalitions and presidential vs parliamentary institutions. We employed matching methods, and regression, to disentangle the effects of populism, presidentialism and supermajorities on the decline in liberal democracy.

To return to the questions asked in the beginning of the article, does democratic backsliding occur because landslide majorities in the hands of powerful leaders enable them to bend the rules of the game to their advantage or is it the activation of a populist ideological repertoire that provides chief executives with sufficient scope to erode liberal democratic institutions? Our answer leans towards the latter: we find strong evidence of more backsliding under populist executives and weak support for the hypotheses that executives controlling a supermajority in the legislature cause more damage to liberal democracy. To a similar question about Latin America specifically, whether it is the institutions of presidential regimes that have caused democratic backsliding there or the region’s extensive experience with populists in power, the evidence supports only the latter explanation. In short, our findings concur with Rummens’ claim that populism is a “threat” to liberal democracy, and not a corrective.Footnote72 These findings should urge practitioners looking to prevent democratic backsliding to consult scholarship on populism and its appeal to voters.Footnote73

We conclude that the populist ideology of executives is largely to blame for democratic backsliding, and that institutional assets are most dangerous when in the hands of the ill-intended. Yet, it remains to be explained why some populist leaders such as Orbán in Hungary and Chavez in Venezuela dismantled the very foundations of liberal democracy in their countries to an extent unappareled even among their populist peers. Our findings put the backsliding of Orbán and Chavez in context: their executive aggrandizement goes much beyond the typical populist in power. In their cases, the extent of decline in liberal democracy surpassed the dividing line between backsliding and democratic breakdown, for which our analysis offers no exhaustive explanation. We look forward to future research that accounts for such outlying cases.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Antonio Benasaglio Berlucchi

Antonio Benasaglio Berlucchi is a doctoral student and research associate at Waseda University in Tokyo. His main research interests are parties, elections and voting behaviour. In particular, his research addresses the relationship between voters’ ideology and values, party positions and election outcomes. He is currently writing a PhD dissertation comparing the vote for non-mainstream challenger parties across EU and non-EU liberal democracies.

Marisa Kellam

Marisa Kellam’s research links institutional analysis to various governance outcomes in democracies, with a focus on Latin America and a growing interest in East Asia. She earned her PhD in Political Science from UCLA in 2007 and has been associate professor at Waseda University in Tokyo since 2013. Currently, she serves as a steering committee member for the V-Dem Regional Center for East Asia and is a visiting scholar at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford University.

Notes

1 For a case study approach, see Haggard and Kaufman, Backsliding; For a quantitative examination of all third-wave democracies, see Wunsch and Blanchard, “Patterns of Democratic Backsliding in Third-Wave Democracies”.

2 Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán, “Democratic Breakdown and Survival”; Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die; Diamond, “Democratic Regression in Comparative Perspective”.

3 Canovan, “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy”; Canovan, “Taking Politics to the People: Populism as the Ideology of Democracy”; Mudde, “The Populist Zeitgeist”; Taggart, “Populism and the Pathology of Representative Politics”.

4 Houle and Kenny, “The Political and Economic Consequences of Populist Rule in Latin America”; Ruth, “Populism and the Erosion of Horizontal Accountability in Latin America”.

5 On presidents, see Cheibub, Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, and Democracy; Helmke, Institutions on the Edge; Hochstetler, “Rethinking Presidentialism”; Linz, “Presidential or Parliamentary: Does It Make a Difference?” On legislative dominance, see Bakke and Sitter, “The EU’s Enfants Terribles”; Pérez-Liñán, Schmidt, and Vairo, “Presidential Hegemony and Democratic Backsliding in Latin America, 1925–2016”; Pozsár-Szentmiklósy, “Supermajority in Parliamentary Systems – A Concept of Substantive Legislative Supermajority”.

6 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding,” 5.

7 Lührmann and Lindberg, “A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here”; Dresden and Howard, “Authoritarian Backsliding and the Concentration of Political Power”.

8 Gerschewski, “Erosion or Decay?”; Maeda, “Two Modes of Democratic Breakdown”.

9 Bermeo, “On Democratic Backsliding,” 10, 13.

10 In the supplementary materials, we list all sources of data and describe our selection criteria, unit of analysis and dependent variable in detail.

11 Dahl, “What Political Institutions Does Large-Scale Democracy Require?”

12 Lueders and Lust, “Multiple Measurements, Elusive Agreement, and Unstable Outcomes in the Study of Regime Change”.

13 Diamond, “Democratic Regression in Comparative Perspective”; Mechkova, Lührmann, and Lindberg, “How Much Democratic Backsliding?”

14 Mainwaring and Bizzarro, “The Fates of Third-Wave Democracies”; Lührmann and Lindberg, “A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here”; Huntington, “Democracy’s Third Wave”.

15 For a helpful discussion of the challenges of measuring backsliding, see Jee, Lueders, and Myrick, “Towards a Unified Approach to Research on Democratic Backsliding”.

16 For a similar finding, see Wunsch and Blanchard, “Patterns of Democratic Backsliding in Third-Wave Democracies”. They find that about half of third-wave democracies have followed stable democratic trajectories, without backsliding.

17 See http://brightlinewatch.org.

18 Jee, Lueders, and Myrick, “Towards a Unified Approach to Research on Democratic Backsliding”.

19 Andersen, “Comparative Democratization and Democratic Backsliding,” 657.

20 Waldner and Lust, “Unwelcome Change,” 97.

21 Ibid., 107.

22 Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die; Mainwaring and Pérez-Liñán, “Democratic Breakdown and Survival”.

23 Diamond, “Democratic Regression in Comparative Perspective,” 12.

24 Alemán and Yang, “A Duration Analysis of Democratic Transitions and Authoritarian Backslides”.

25 Diamond, Ill Winds: Saving Democracy from Russian Rage, Chinese Ambition and American Complacency.

26 Mudde, “The Populist Zeitgeist,” 543.

27 Arditi, “Populism, or, Politics at the Edges of Democracy”; Laclau, On Populist Reason; Mudde and Kaltwasser, Populism in Europe and the Americas.

28 Galston, “The Populist Challenge to Liberal Democracy”; Plattner, “Democracy’s Past and Future”; Rummens, “Populism as a Threat to Liberal Democracy,” 26 October 2017.

29 Taggart, “Populism and the Pathology of Representative Politics”.

30 Abts and Rummens, “Populism versus Democracy”; Plattner, “Democracy’s Past and Future”.

31 Canovan, “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy”; Canovan, “Taking Politics to the People: Populism as the Ideology of Democracy”; Rummens, “Populism as a Threat to Liberal Democracy,” 2017.

32 Albertazzi and McDonnell, “Introduction”; Urbinati, “Democracy and Populism”.

33 Albertazzi and Mueller, “Populism and Liberal Democracy”; Grzymala-Busse, “How Populists Rule”; Houle and Kenny, “The Political and Economic Consequences of Populist Rule in Latin America”; Vittori, “Threat or Corrective?”; Kenny, ““The Enemy of the People””; Ruth-Lovell and Grahn, “Threat or Corrective to Democracy?”; Juon and Bochsler, “Hurricane or Fresh Breeze?”

34 Ruth-Lovell and Grahn, “Threat or Corrective to Democracy?”; Juon and Bochsler, “Hurricane or Fresh Breeze?”

35 Linz, “The Perils of Presidentialism”.

36 Carreras, “The Evolution of the Study of Executive-Legislative Relations in Latin America”.

37 Samuels and Shugart, Presidents, Parties, and Prime Ministers: How the Separation of Powers Affects Party Organization and Behavior, 16.

38 Linz, “Presidential or Parliamentary: Does It Make a Difference?”; Tsebelis, “Decision Making in Political Systems”.

39 Shugart and Carey, Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics.

40 Cooper, By Order of the President.

41 Hochstetler, “Rethinking Presidentialism”; Kim and Bahry, “Interrupted Presidencies in Third Wave Democracies”; Helmke, Institutions on the Edge.

42 Conaghan, “Ecuador,” 51–2.

43 Sedelius and Linde, “Unravelling Semi-Presidentialism”.

44 Maeda, “Two Modes of Democratic Breakdown”; Svolik, “Which Democracies Will Last?”

45 Sedelius and Linde, “Unravelling Semi-Presidentialism”.

46 Corrales, “Can Anyone Stop the President?”

47 Sánchez-Sibony, “Competitive Authoritarianism in Morales’s Bolivia,” 128.

48 Bakke and Sitter, “The EU’s Enfants Terribles”; Pozsár-Szentmiklósy, “Supermajority in Parliamentary Systems – A Concept of Substantive Legislative Supermajority”.

49 Kelemen, “Europe’s Other Democratic Deficit,” 222.

50 Haggard and Kaufman, “The Anatomy of Democratic Backsliding”; Pérez-Liñán, Schmidt, and Vairo, “Presidential Hegemony and Democratic Backsliding in Latin America, 1925–2016”.

51 Kellam and Stein, “Silencing Critics: Why and How Presidents Restrict Media Freedom in Democracies”.

52 Haggard and Kaufman, “The Anatomy of Democratic Backsliding”.

53 Pérez-Liñán, Schmidt, and Vairo, “Presidential Hegemony and Democratic Backsliding in Latin America, 1925–2016”.

54 We treat Austria and Iceland as functionally-equivalent to a parliamentary system. We exclude countries with collective executives or those that employ systems other than one of the four aforementioned systems of government.

55 Grzymala-Busse and McFaul, “Votes for Populists Codebook”.

56 Stuart, “Matching Methods for Causal Inference”.

57 Given that we are matching on several continuous variables, we employ the bias-adjusted estimator available in Stata. See page 270 in Stata Treatment Effects Reference Manual: Potential Outcomes/Counterfactual Outcomes, Release 15, Stata Press: College Station, TX.

58 For instance, GDP per capita, a measure of economic development, is highly correlated with democratic stock.

59 If the executive assumes office after July 1, we use data from the current year.

60 Bolt and van Zanden, “GDP per Capita”.

61 Gerring et al., “Democracy and Economic Growth”.

62 Edgell et al., “Democratic Legacies”.

63 Fariss et al., “New Estimates of Over 500 Years of Historic GDP and Population Data”.

64 Gygli et al., “The KOF Globalisation Index – Revisited”.

65 Frantz et al., “Personalist Ruling Parties in Democracies”; McCoy and Somer, “Toward a Theory of Pernicious Polarization and How It Harms Democracies”; Orhan, “The Relationship between Affective Polarization and Democratic Backsliding”.

66 Diamond, “Democratic Regression in Comparative Perspective,” 9.

67 Houle and Kenny, “The Political and Economic Consequences of Populist Rule in Latin America”; Pérez-Liñán, Schmidt, and Vairo, “Presidential Hegemony and Democratic Backsliding in Latin America, 1925–2016”.

68 Stuart, “Matching Methods for Causal Inference”.

69 To assess covariate balance, we rely on thresholds of 0.1 or less for the absolute value of the standardized differences of means and between 0.5 and 1.5 for the variance ratios. See supplementary materials.

70 In fact, we find a positive relationship between presidentialism and backsliding when we do not take populism into account. However, our analysis as presented here, which controls for populism, reveals this relationship to be spurious.

71 Bakke and Sitter, “The EU’s Enfants Terribles,” 23.

72 Rummens, “Populism as a Threat to Liberal Democracy,” 2017.

73 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash; Rodrik, “Why Does Globalization Fuel Populism? Economics, Culture, and the Rise of Right-Wing Populism”; Bakker, Schumacher, and Rooduijn, “The Populist Appeal”.

Bibliography

- Abts, Koen, and Stefan Rummens. “Populism versus Democracy.” Political Studies 55, no. 2 (1 June 2007): 405–24.

- Albertazzi, Daniele, and Duncan McDonnell. “Introduction: The Sceptre and the Spectre.” In Twenty-First Century Populism, edited by Daniele Albertazzi and Duncan McDonnell, 1–11. Springer, 2008.

- Albertazzi, Daniele, and Sean Mueller. “Populism and Liberal Democracy: Populists in Government in Austria, Italy, Poland and Switzerland.” Government and Opposition 48, no. 3 (July 2013): 343–71.

- Alemán, José, and David D. Yang. “A Duration Analysis of Democratic Transitions and Authoritarian Backslides.” Comparative Political Studies 44, no. 9 (September 2011): 1123–51.

- Andersen, David. “Comparative Democratization and Democratic Backsliding: The Case for a Historical-Institutional Approach.” Comparative Politics 51, no. 4 (1 June 2019): 645–63.

- Arditi, Benjamin. “Populism, or, Politics at the Edges of Democracy.” Contemporary Politics 9, no. 1 (March 2003): 17–31.

- Bakke, Elisabeth, and Nick Sitter. “The EU’s Enfants Terribles : Democratic Backsliding in Central Europe Since 2010.” Perspectives on Politics 20, no. 1 (March 2022): 22–37.

- Bakker, Bert N., Gijs Schumacher, and Matthijs Rooduijn. “The Populist Appeal: Personality and Antiestablishment Communication.” The Journal of Politics 83, no. 2 (1 April 2021): 589–601.

- Bermeo, Nancy. “On Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 27, no. 1 (2016): 5–19.

- Bolt, Jutta, and Jan Luiten van Zanden. “GDP per Capita.” IISH Dataverse, 2015. https://clio-infra.eu/Indicators/GDPperCapita.html.

- Canovan, Margaret. “Taking Politics to the People: Populism as the Ideology of Democracy.” In Democracies and the Populist Challenge, 25–44. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Canovan, Margaret. “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy.” Political Studies 47, no. 1 (1 March 1999): 2–16.

- Carreras, Miguel. “The Evolution of the Study of Executive-Legislative Relations in Latin America: Or How Theory Slowly Catches up with Reality.” Revista Ibero-Americana de Estudos Legislativos 2 (2012): 20–6.

- Cheibub, José Antonio. Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, and Democracy. Cambridge: CUP, 2007.

- Conaghan, Catherine M. “Ecuador: Correa’s Plebiscitary Presidency.” Journal of Democracy 19, no. 2 (2008): 46–60.

- Cooper, Phillip J. By Order of the President: The Use and Abuse of Executive Direct Action. Second Edition, Revised and Expanded. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2014.

- Corrales, Javier. “Can Anyone Stop the President? Power Asymmetries and Term Limits in Latin America, 1984–2016.” Latin American Politics and Society 58, no. 2 (1 June 2016): 3–25.

- Dahl, Robert A. “What Political Institutions Does Large-Scale Democracy Require?” Political Science Quarterly 120, no. 2 (2005): 187–97.

- Diamond, Larry. “Democratic Regression in Comparative Perspective: Scope, Methods, and Causes.” Democratization 28, no. 1 (2 January 2021): 22–42.

- Diamond, Larry. Ill Winds: Saving Democracy from Russian Rage, Chinese Ambition and American Complacency. New York: Penguin Press, 2019.

- Dresden, Jennifer Raymond, and Marc Morjé Howard. “Authoritarian Backsliding and the Concentration of Political Power.” Democratization 23, no. 7 (9 November 2016): 1122–43.

- Edgell, Amanda B., Matthew C. Wilson, Vanessa A. Boese, and Sandra Grahn. “Democratic Legacies: Using Democratic Stock to Assess Norms, Growth, and Regime Trajectories.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, 1 May 2020.

- Fariss, Christopher J., Therese Anders, Jonathan N. Markowitz, and Miriam Barnum. “New Estimates of Over 500 Years of Historic GDP and Population Data.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 66, no. 3 (1 April 2022): 553–91.

- Frantz, Erica, Andrea Kendall-Taylor, Jia Li, and Joseph Wright. “Personalist Ruling Parties in Democracies.” Democratization 29, no. 5 (4 July 2022): 918–38.

- Galston, William A. “The Populist Challenge to Liberal Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 29, no. 2 (10 April 2018): 5–19.

- Gerring, John, Philip Bond, William T. Barndt, and Carola Moreno. “Democracy and Economic Growth: A Historical Perspective.” World Politics 57, no. 3 (April 2005): 323–64.

- Gerschewski, Johannes. “Erosion or Decay? Conceptualizing Causes and Mechanisms of Democratic Regression.” Democratization 28, no. 1 (2 January 2021): 43–62.

- Grzymala-Busse, Anna. “How Populists Rule: The Consequences for Democratic Governance.” Polity 51, no. 4 (October 2019): 707–17.

- Grzymala-Busse, Anna, and Michael McFaul. “Votes for Populists Codebook.” Global Populisms Project. Stanford University, 2020.

- Gygli, Savina, Florian Haelg, Niklas Potrafke, and Jan-Egbert Sturm. “The KOF Globalisation Index – Revisited.” The Review of International Organizations 14, no. 3 (1 September 2019): 543–74.

- Haggard, Stephan, and Robert Kaufman. Backsliding: Democratic Regress in the Contemporary World. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021.

- Haggard, Stephan, and Robert Kaufman. “The Anatomy of Democratic Backsliding.” Journal of Democracy 32, no. 4 (2021): 27–41.

- Helmke, Gretchen. Institutions on the Edge: The Origins and Consequences of Inter-Branch Crises in Latin America. Cambridge Studies in Comparative Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Hochstetler, Kathryn. “Rethinking Presidentialism: Challenges and Presidential Falls in South America.” Comparative Politics 38, no. 4 (1 July 2006): 401–18.

- Houle, Christian, and Paul D. Kenny. “The Political and Economic Consequences of Populist Rule in Latin America.” Government and Opposition 53, no. 2 (April 2018): 256–87.

- Huntington, Samuel P. “Democracy’s Third Wave.” Journal of Democracy 2, no. 2 (1991): 12.

- Jee, Haemin, Hans Lueders, and Rachel Myrick. “Towards a Unified Approach to Research on Democratic Backsliding.” Democratization 29, no. 4 (9 December 2021): 1–14.

- Juon, Andreas, and Daniel Bochsler. “Hurricane or Fresh Breeze? Disentangling the Populist Effect on the Quality of Democracy.” European Political Science Review 12, no. 3 (August 2020): 391–408.

- Kelemen, R. Daniel. “Europe’s Other Democratic Deficit: National Authoritarianism in Europe’s Democratic Union.” Government and Opposition 52, no. 2 (April 2017): 211–38.

- Kellam, Marisa, and Elizabeth A. Stein. “Silencing Critics: Why and How Presidents Restrict Media Freedom in Democracies.” Comparative Political Studies 49 (2016): 36–77.

- Kenny, Paul D. ““The Enemy of the People”: Populists and Press Freedom.” Political Research Quarterly 73, no. 2 (1 June 2020): 261–75.

- Kim, Young Hun, and Donna Bahry. “Interrupted Presidencies in Third Wave Democracies.” The Journal of Politics 70, no. 3 (July 2008): 807–22.

- Laclau, Ernesto. On Populist Reason. London: Verso, 2005.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Daniel Ziblatt. How Democracies Die. New York: Crown, 2018.

- Linz, Juan. “Presidential or Parliamentary: Does It Make a Difference?” In The Failure of Presidential Democracy, edited by Juan Linz, and Arturo Valenzuela. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1994.

- Linz, Juan. “The Perils of Presidentialism.” Journal of Democracy 1, no. 1 (1990): 51–69.

- Lueders, Hans, and Ellen Lust. “Multiple Measurements, Elusive Agreement, and Unstable Outcomes in the Study of Regime Change.” The Journal of Politics 80, no. 2 (April 2018): 736–41.

- Lührmann, Anna, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here: What Is New about It?” Democratization 26, no. 7 (3 October 2019): 1095–113.

- Maeda, Ko. “Two Modes of Democratic Breakdown: A Competing Risks Analysis of Democratic Durability.” The Journal of Politics 72, no. 4 (October 2010): 1129–43.

- Mainwaring, Scott, and Fernando Bizzarro. “The Fates of Third-Wave Democracies.” Journal of Democracy 30, no. 1 (2019): 99–113.

- Mainwaring, Scott, and Aníbal Pérez-Liñán. “Democratic Breakdown and Survival.” Journal of Democracy 24, no. 2 (2013): 123–37.

- McCoy, Jennifer, and Murat Somer. “Toward a Theory of Pernicious Polarization and How It Harms Democracies: Comparative Evidence and Possible Remedies.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 681, no. 1 (January 2019): 234–71.

- Mechkova, Valeriya, Anna Lührmann, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “How Much Democratic Backsliding?” Journal of Democracy 28, no. 4 (2017): 162–9.

- Mudde, Cas. “The Populist Zeitgeist.” Government and Opposition 39, no. 4 (2004): 541–63.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or Corrective for Democracy? New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Orhan, Yunus Emre. “The Relationship between Affective Polarization and Democratic Backsliding: Comparative Evidence.” Democratization 29, no. 4 (19 May 2022): 714–35.

- Pérez-Liñán, Aníbal, Nicolás Schmidt, and Daniela Vairo. “Presidential Hegemony and Democratic Backsliding in Latin America, 1925–2016.” Democratization 26, no. 4 (19 May 2019): 606–25.

- Plattner, Marc F. “Democracy’s Past and Future: Populism, Pluralism, and Liberal Democracy.” Journal of Democracy 21, no. 1 (2010): 81–92.

- Pozsár-Szentmiklósy, Zoltán. “Supermajority in Parliamentary Systems – A Concept of Substantive Legislative Supermajority: Lessons from Hungary.” Hungarian Journal of Legal Studies 58, no. 3 (September 2017): 281–90.

- Rodrik, Dani. “Why Does Globalization Fuel Populism? Economics, Culture, and the Rise of Right-Wing Populism.” Annual Review of Economics 13, no. 1 (2021): 133–70.

- Rummens, Stefan. “Populism as a Threat to Liberal Democracy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Populism, edited by Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Paul Taggart, Paulina Ochoa Espejo, and Pierre Ostiguy, 554–70. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Rummens, Stefan. “Populism as a Threat to Liberal Democracy”, 26 October 2017.

- Ruth, Saskia Pauline. “Populism and the Erosion of Horizontal Accountability in Latin America.” Political Studies 66, no. 2 (May 2018): 356–75.

- Ruth-Lovell, Saskia Pauline, and Sandra Grahn. “Threat or Corrective to Democracy? The Relationship between Populism and Different Models of Democracy.” European Journal of Political Research (2022): 1–22.

- Samuels, David, and Matthew Shugart. Presidents, Parties, and Prime Ministers: How the Separation of Powers Affects Party Organization and Behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Sánchez-Sibony, Omar. “Competitive Authoritarianism in Morales’s Bolivia: Skewing Arenas of Competition.” Latin American Politics and Society 63, no. 1 (February 2021): 118–44.

- Sedelius, Thomas, and Jonas Linde. “Unravelling Semi-Presidentialism: Democracy and Government Performance in Four Distinct Regime Types.” Democratization 25, no. 1 (2 January 2018): 136–57.

- Shugart, Matthew S., and John M. Carey. Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics. Cambridge, U.K: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Stuart, Elizabeth A. “Matching Methods for Causal Inference: A Review and a Look Forward.” Statistical Science 25, no. 1 (1 February 2010): 1–21.

- Svolik, Milan W. “Which Democracies Will Last? Coups, Incumbent Takeovers, and the Dynamic of Democratic Consolidation.” British Journal of Political Science 45, no. 4 (October 2015): 715–38.

- Taggart, Paul. “Populism and the Pathology of Representative Politics.” In Democracies and the Populist Challenge, edited by Mény Yves and Surel Yves, 62–80. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.

- Tsebelis, George. “Decision Making in Political Systems: Veto Players in Presidentialism, Parliamentarism, Multicameralism and Multipartyism.” British Journal of Political Science 25, no. 03 (July 1995): 289.

- Urbinati, Nadia. “Democracy and Populism.” Constellations 5, no. 1 (1998): 110–24.

- Vittori, Davide. “Threat or Corrective? Assessing the Impact of Populist Parties in Government on the Qualities of Democracy: A 19-Country Comparison.” Government and Opposition (6 July 2021): 1–21. doi:10.1017/gov.2021.21.

- Waldner, David, and Ellen Lust. “Unwelcome Change: Coming to Terms with Democratic Backsliding.” Annual Review of Political Science 21, no. 1 (11 May 2018): 93–113.

- Wunsch, Natasha, and Philippe Blanchard. “Patterns of Democratic Backsliding in Third-Wave Democracies: A Sequence Analysis Perspective.” Democratization (2 December 2022): 1–24. doi:10.1080/13510347.2022.2130260.