ABSTRACT

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments across the globe implemented severe restrictions of civic freedoms to contain the spread of the virus. The global health emergency posed the risk of governments seizing the pandemic as a window of opportunity to curb (potential) challenges to their power, thereby reinforcing the ongoing, worldwide trend of shrinking civic spaces. In this article, we investigate whether and how governments used the pandemic as a justification to impose restrictions of freedom of expression. Drawing on the scholarship on the causes of civic space restrictions, we argue that governments responded to COVID-19 by curtailing the freedom of expression when they had faced significant contentious political challenges before the pandemic. Our results from a quantitative analysis indeed show that countries who experienced high levels of pro-democracy mobilization before the onset of the pandemic were more likely to see restrictions of the freedom of expression relative to countries with no or low levels of mobilization. Additional three brief case studies (Algeria, Bolivia and India) illustrate the process of how pre-pandemic mass protests fostered the im-position of restrictions on the freedom of expression during the pandemic.

1. Introduction

During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, authorities in Algeria, Hungary, Russia, Thailand or Uzbekistan introduced penalties including prison sentences for the dissemination of false information on the pandemic. In Bolivia, an executive decree established “penalties for persons who incite non-compliance, misinform, or cause uncertainty among the population”. Meanwhile, Egypt’s Supreme Council for Media Regulation threatened “legal action against journalists or media outlets who might depict negative aspects of the government’s response to the COVID-19 crisis” and “blocked or limited access to dozens of news websites and social media accounts for allegedly spreading false information about the coronavirus”.

These examples, which are taken from the COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker produced by the International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL),Footnote1 represent but a few of a whole range of measures adopted through 2020 by governments across the world as supposed means to contain the spread of COVID-19. As Freedom House summarized in October 2020:

“Journalists covering the [COVID-19] crisis have been arrested and targeted with violence, harassment, and intimidation. Governments have exerted control over content, revoked outlets’ registrations, suspended printing of newspapers, denied press credentials, and limited independent questioning at press conferences. New legislation against spreading ‘fake news’ about the virus has been passed, while websites have been blocked and online articles or social media posts removed.”Footnote2

COVID-related restrictions on the freedom of expression are part of a broader wave of governmental measures that, since 2020, have infringed upon a number of basic rights in the name of pandemic control. This has given rise to a debate about “pandemic backsliding”, i.e. a (further) erosion of democratic norms and institutions triggered by COVID-19.Footnote6 In addition to constraints on democratic processes and institutions, which concern parliaments, judicial controls and the holding of elections, policy measures have particularly implied restrictions on the individual and collective ability of citizens to organize, act collectively, and express their interests and values.Footnote7 At least temporarily, pandemic-related restrictions have brought about a dramatic shrinking of civic spaces.Footnote8 Still, while the wave of pandemic-related civic space restrictions has been almost global in nature and characterized by many commonalitiesFootnote9, there are also important differences between countries that concern the specific type and combination of measures, their overall intensity as well as the extent to which they violate democratic and human rights standards.Footnote10 This variation points to a key question that is of great interest for the overall debate on the causes of shrinking civic spaces but that is also of significant political relevance: Under which conditions have governments used the COVID-19 pandemic as an opportunity and a justification to impose civic space restrictions for political purposes?

In this article, we contribute to research about the causes of civic space restrictions by focusing on restrictions of the freedom of expression in response to COVID-19. We do so by investigating one prominent explanation that has been put forward in the overall research on shrinking civic spaces, namely: the argument that governments restrict the space, capacity and autonomy of civil society organizations (CSOs) in response to (perceived) threats to their power that emanate from these very CSOs.Footnote11 More specifically, we argue that governments responded to the COVID-19 pandemic by introducing or tightening restrictions on the freedom of expression when they had faced significant contentious political challenges – that is, mass protests directed against the government, its policies or the entire regimeFootnote12 – before the outbreak and global spread of the pandemic.

It is for two reasons that we focus on restrictions of the freedom of expression. First, this type of restriction most directly signals a political misuse of the pandemic by the executive as a justification “to repress domestic dissent”.Footnote13 To be sure, in the context of states of emergency and lockdowns, severe restrictions of the freedoms of assembly and movement have been the most far-reaching and widespread measures taken in response to the pandemic. Yet, as even human rights organizations and observers have noted, such restrictions in and of themselves may well be justified as means to protect citizens by containing the spread of COVID-19.Footnote14 In contrast to social distancing measures, it is much more difficult to see restrictions on the freedom of expression as an appropriate means of pandemic control.Footnote15 As mentioned above, therefore, restrictions on the freedom of expression have been identified as the most important area in which violations of democratic standards have been observed.Footnote16

The second reason is more empirical in nature. Pandemic-related restrictions on the freedom of assembly have been so widespread that variation in the outcome is limited. Restrictions on the freedom of association, in contrast, have been very rare. It is precisely with a view to freedom of expression that we observe significant variation in the implementation of restrictions, which may suggest a strategic political explanation.Footnote17

The article provides a quantitative analysis of how contentious political challenges, measured as pro-democratic mass mobilization prior to the pandemic, influence the probability of COVID-19-related restrictions of freedom of expression. With logistic regression analysis, we show that governments that had previously faced such significant contentious political challenges were indeed more likely to restrict the freedom of expression during the pandemic. Results from three brief case studies (Algeria, Bolivia and India) support the interpretation that there is indeed a link between the experience with pre-pandemic mass protest and the decision to impose restrictions on the freedom of expression in response to COVID-19. These findings improve our understand about the causes of shrinking civic spaces in general and pandemic-related restrictions in particular.

The article is organized as follows. The next section situates our study in the context of existing research on shrinking civic spaces and pandemic-related restrictions. In the third section we clarify the main concepts that guide our analysis and detail the theoretical argument and its empirical implications. Data and estimation procedures for the empirical analysis are discussed in section four. In section five, we describe the results of the quantitative analysis. Section six provides corroborating evidence from three country cases. In the conclusion, the results of the analysis, caveats, and avenues for further research are discussed.

2. State of research

This article contributes to two scholarly debates: the literature on the phenomenon of shrinking civic spaces, that is, on the global wave of governmental restrictions targeting civil society actors that has been observed since the early 2000s; and incipient research on the restrictions that have been introduced since early 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. With a view to both debates, our focus is on explaining these restrictive policies.

In the early 2000s, it was US think tanks and policy circles that first drew attention to a new trend of restrictions imposed on (foreign-funded) CSOs in the context of an emerging “backlash against democracy promotion”.Footnote18 As shrinking civic spaces continued to spread and impact the work of many internationally engaged activists and organizations, a growing body of scholarship began to address the phenomenon. This first generation of contributions was mostly of a descriptive and/or policy-oriented nature.Footnote19 With a certain time lag, scholars began to analyse the empirical trend more closely with a view to identifying its various manifestations as well as the conditions under which governments resort to civic space restrictions. The majority of existing comparative analyses tends to focus on restrictions on international civil society support.Footnote20 Only a few academic studies have begun to look at the wider spectrum of restrictions on domestic CSOs, many of which are independent of their relations with external actors.Footnote21

Regarding the causes of shrinking civic spaces, existing publications highlight a set of factors that have arguably triggered, driven or enabled the current wave of civic space restrictions, including the spread of counter-terrorist measures following 9/11, fear of contagion on the part of incumbent governments in response to the “color revolutions”, as well as the changes in global power relations and the rising assertiveness of non-democratic states like China and Russia.Footnote22 But the precise relationship between these broader trends and the adoption and implementation of civic space restrictions has yet to be studied systematically.

Comparative research on the causes of shrinking civic spaces, which mainly consists of a few large-N studies, points to several potential causes.Footnote23 At the international level, these potential causes include factors such as foreign aid, economic dependencies, and commitment to human rights treaties. At the domestic level, research highlights the relevance of political regime type, the ability of CSOs to mobilize against the government, public opinion (i.e. government popularity), terrorist incidents, and the existence and timing of elections. From a theoretical perspective, existing studies mainly assume that both international and domestic drivers of civic space restrictions primarily operate through governments’ threat perceptions: If governments perceive (foreign-funded) CSOs as competitors and a threat to their power, they tend to respond with restrictions to mitigate these threats.Footnote24

Considering this ongoing trend of shrinking civic spaces, the wave of restrictions adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic immediately raised concern among both civil society organizations and scholars.Footnote25 Early on, academic institutions and CSOs started to gather data on the governmental restrictions imposed in response to COVID-19.Footnote26 However, there is still little academic research that analyses, from a comparative perspective, governmental responses to COVID-19 and their implications for civic spaces. In a previous publication, written in August 2020, we provided a descriptive analysis of civic space restrictions, based on an analysis of the data available at that time.Footnote27 Among other things, we found that while most governments focused their pandemic control measures on restricting public gatherings, some engaged also in media restrictions and/or directly targeted CSOs that opposed the government. Another study, which similarly focuses on the first months of the pandemic, finds “democratic violations in dictatorships and democracies alike, with a high degree of heterogeneity within and across regime types”.Footnote28 When it comes to the specific types of violations of democratic standards, the article finds that media freedom is by the far the area most affected by major violations.Footnote29 Looking broadly at “nonpharmaceutical interventions” against the COVID-19 pandemic, Abiel Sebhatu et al. identify a surprisingly homogeneous response across OECD member states, emphasizing processes of policy diffusion.Footnote30

A second strand of incipient research looks at (the implications of) civic space restrictions from the perspective of civil society actors and protest movements in particular. An early assessment of global protest dynamics until the end of April 2020 found an “unprecedented fall in protest activity around the world […] especially in Asian and European countries”.Footnote31 Yet, later studies quickly revealed that the global reduction in protest remained a rather short-term phenomenon only. Following a significant drop in the number of protest events around mid-March 2020, protests quickly started to resurge and, by early-October 2020 surpassed the pre-pandemic level.Footnote32 In addition, qualitative studies have analysed the dynamics of social protest, the adaptation on the part of social movements as well as the broader shifts in civic activism in the context of the pandemic.Footnote33 Overall, this research suggests that the pandemic has not led to an effective closure of civic space.

Related research investigated if and how the pandemic created an opportunity for governments to intensify state repression. Focusing on state violence against civilians in Africa, Grasse et al. suggest that pandemic-related shutdown orders led to substantial increases in repression.Footnote34 In a global analysis, Barceló et al. find that governments that had previously engaged in state violence or human rights abuses were substantially more likely to enact lockdown and curfew policies.Footnote35

In sum, we still know little about the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the dynamics of shrinking civic spaces. While existing research points to a high degree of variation or heterogeneity when it comes to civic space restrictions, we know little about the causes of this variation.

3. Theoretical approach

To conceptualize the causes of pandemic-related restrictions of freedom of expression, we situate these measures within a general framework of shrinking civic spaces. The term civic space refers to the scope of action that individual citizens as well as formal and informal CSOs have to organize, act collectively, and express their interests and values.Footnote36 In the terminology of international human rights law, these three functions correspond to three core freedoms of association, assembly, and expression. Civic space restrictions, then, are policies that deliberately constrain the room for civic activism in at least one of these three domains.

During the pandemic in 2020, most frequently governments across the globe substantially limited citizens’ and CSOs’ freedom to assemble and protest in public places. Lockdown measures included curfews and contact bans of varying severity. Pandemic-related restrictions targeting freedom of association occurred only in few countries, but a substantial number of governments responded to the pandemic by restricting freedom of expression.Footnote37

Against this background, we conceptualize the pandemic as a window of opportunity for governments to implement civic space restrictions in general and restrictions of freedom of expression in particular. In this sense, COVID-19 bears similarities to the way in which the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the subsequent wave of counterterrorism measures contributed to the spread of civic space restrictions in the early 2000s.Footnote38 In both cases, an exogenous threat (terrorism, the coronavirus) enables governments to frame and justify restrictions as measures necessary to protect the very citizens whose rights are infringed upon. However, the specific threat narrative has consequences for the types of civic space restrictions that can be justified. In the case of COVID-19, the most obvious measures, which responded to the aim to advance social distancing and reduce physical contacts among people, concerned restrictions of the freedom of assembly. At the same time, lockdowns and broad bans on public gatherings can hardly be used as targeted means to restrict the space of specific actors. This may well explain why they have been very hard to sustain – and why they have been only temporarily effective in shutting down anti-government protests. In the case of the freedom of association, the pandemic appears to be less useful to justify restrictions, not to speak of targeted restrictions that deliberately focus on a subgroup of CSOs for political purposes. Accordingly, beyond constraints on the freedom of assembly only few governments have responded to the pandemic by directly limiting the ability of CSOs to operate.

This has been different in the case of our third domain of civic spaces. To be sure, restrictions of the freedom of expression do not directly reduce the spread of the coronavirus. Yet, the (supposed) need to curb the propagation of misinformation that would undermine pandemic control policies enabled governments to justify corresponding measures. In fact, key justifications offered by governments when curbing the freedom of expression included the need to prevent the spread of “fake news” and misinformation.Footnote39 We identify three types of policies of pandemic related restrictions of freedom of expression: Extending government control over media (including censorship); criminalizing the distribution of “fake news” and misinformation; and verbal as well as physical attacks or harassment of media outlets and individual journalists.

Considering the role of governmental threat perceptions that has been emphasized by research on shrinking civic spaces, we argue that such pandemic-related restrictions of freedom of expression tend to occur in countries in which governments have been confronted by significant contentious political challenges. Drawing on Franklin, we define significant contentious political challenges as “collective, unconventional acts taken by inhabitants of a country directed against or expressing opposition to their government, its policies or personal, or the political regime itself” that achieve mass participation and, thereby, acquire national-level political importance.Footnote40 Given such mass protests, governments are likely to perceive civil society actors as threats to their hold on power, which creates incentives to limit their strength, influence and impact by restricting the freedom of expression. As scholars of social movements and protest have shown, freedom of expression is a crucial factor that facilitates contentious collective action, while constraints on the freedom of expression increase coordination problems among opposition groups and limit their capacity to reach a wider audience.Footnote41

Accordingly, we expect that governments that had faced contentious political challenges via social movements and mass protests were more likely to implement pandemic-related restrictions of freedom of expression.

4. Research design

To measure pandemic-related restrictions of freedom of expression, we collected data from ICNL’s COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker and the Global Monitor on Covid-19’s Impact on Democracy and Human Rights hosted by International IDEA, which report pandemic emergency response measures that include civic space restrictions. Using these reports, we created a binary indicator, restriction of expression, which takes the value of 1 if a country implemented policies that restrict freedom of expression in response to the pandemic and the value of 0 if no restrictions occurred. The indicator refers to the initial policy response to the pandemic, i.e. we only include policies that were implemented in 2020. We consider this a broad-based measure, which captures both legal and non-legal restrictions of freedom of expression. Our data covers 175 countries across the globe.Footnote42

shows the frequency of restrictions for the sample of countries included in the analysis. As shown, the majority of countries did not impose restrictions of freedom of expression. However, a substantial share of more than 40% did.

Table 1. Frequency of restrictions of freedom of expression.

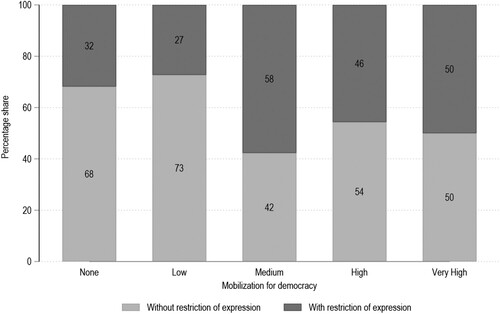

Our main explanatory variable captures if the government, prior to the pandemic, faced substantial contentious political challenges as defined above. Here, we use the indicator mobilization for democracy that is provided by V-Dem and measures the frequency and size of mass events of citizens (demonstrations, strikes, sit-ins) that explicitly pursue pro-democratic goals.Footnote43 The indicator is scaled from zero (no events) to four (many large-scale and small-scale events).Footnote44 All indicator scores are measured for the year 2019. describes the frequency distribution of the five categories for the sample of countries included in our analysis.

Table 2. Frequency of different levels of mobilization for democracy 2019.

As shown in , cases are spread across all categories measuring the severity of mobilization. , which depicts the percentage share of cases with and without restrictions for each category of mobilization for democracy, indicates that a substantially higher share of countries that had medium to very high levels of pro-democracy mobilization prior to the onset of the pandemic saw governments imposing restriction on freedom of expression later (46% to 58% versus 27% and 32% for countries with none or low levels of mobilization).

Figure 1. Share of countries with restrictions across different levels of pro-democracy mobilization.

In the following empirical analysis, we will investigate this descriptive pattern in more detail, while also accounting for confounding factors using logistic regression analysis. Specifically, we use the indicator of pro-democracy mobilization in three different ways to capture specific treatment effects on the probability of restrictions. First, we employ a continuous measurement to estimate the effect of a one-unit change in pro-democracy mobilization on the probability of governments implementing restrictions on freedom of expression in response to the pandemic. Second, we use a categorical measurement to estimate the effect of each specific level of the treatment indicator relative to the baseline category of no mobilization on the probability of restrictions. Third, we use a binary measurement, which estimates the effect of substantial mobilization (i.e. categories of medium, high, and very high mobilization) relative to no or low mobilization on the probability of restrictions.

For regression analysis, we include covariates measuring the level of liberal democracy, populist rule, GDP per capita, (log), Covid-19 Cases per mil. (log), which represent either potential confounding or prognostic factors. As indicated by previous research, pandemic response strategies appear to be less likely to contain violations of democratic standards the higher the level of democracy in a country is.Footnote45 At the same, higher levels of democracy should also make the occurrence of pro-democracy mobilization less likely. We account for this potential confounding factor by including V-Dem’s Liberal Democracy Index in our regression model. Moreover, previous research indicates that once in power, populist rulers may foster the occurrence of pro-democratic resistance.Footnote46 At the same time, research has shown that populist rule is associated with a decline in media freedom.Footnote47 Accordingly, we include populist rule as a potential confounding factor in our regression model. Using data from the Global Populism in Power databaseFootnote48, we created the indicator populist rule, which measures if through the pandemic in 2020 a country was governed by a populist leader or government. Individual leaders or governments are coded as populist if they simultaneously put forward two types of claims: (1) That “the people” are locked into conflict with outsiders (including domestic elites); and (2) nothing should constrain the will of the “true people”.

Finally, we include measures of economic development and COVID-19 cases per one million population in our statistical models, to approximate the exposure of states to the pandemic and their capacity to handle it. We measure the economic development of countries with an indicator of GDP per capita. The data comes from the World Development Indicators.Footnote49 Data on the number of COVID-19 cases comes from the World Health Organization Coronavirus Dashboard. To address skewness and non-linearity, we apply a natural logarithm transformation for the variables measuring GDP per capita and COVID-19 cases. Summary statistics for all variables used in the analysis are reported in the appendix.

5. Quantitative analysis

describes the main findings from the logistic regression analysis. Model 1 reports the results for the continuous measure, model 2 for the categorical measurement and model 3 for the binary measurement of pro-democracy mobilization.

Table 3. Restriction of freedom of expression.

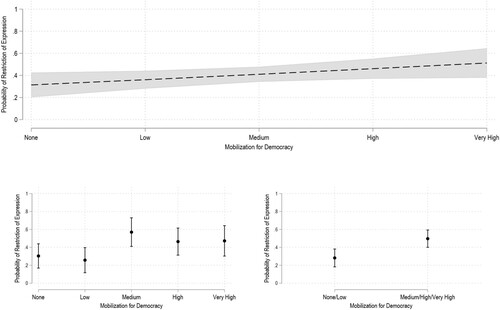

The results for the different indicators of pro-democracy mobilization indicate a positive effect on restrictions. To further explore the size of the effects, we provide marginal effect estimates in .

The upper panel of describes the effect of the continuous measure of pro-democracy mobilization on the occurrence of restrictions. The estimated coefficient, which is statistically significant at p < 0.1, suggests a linear effect of about 5% for each additional level of pro-democracy mobilization. Without any pro-democracy mobilization, the probability of restrictions is estimated as 31%. The probability increases up until 51% with very high levels of pro-democracy mobilization. However, the estimates for the categorical measurement of democracy mobilization suggest that the relationship is not linear. As shown in the lower-left panel of , the probability of restrictions is not increasing with each level of democracy mobilization. Instead, the probability of restriction is small for none or low levels of democracy mobilization and substantially higher for medium and higher levels of democracy mobilization. Therefore, the binary measure of pro-democracy mobilization seems to be the most appropriate measure for the empirical patterns in the data. As shown in the lower-right panel of , at no or low levels of democracy mobilization the probability of restrictions is estimated as 28% and with medium, high or very high levels the probability is 50%. The effect size is substantial and the difference between the two categories is statistically significant.

Among the other covariates described in , we find a statistically significant negative effect of the Liberal Democracy Index on the probability of restrictions of freedom of expression. The more democratic a country is the less likely governments implement restrictions of freedom of expression due to the pandemic. Moreover, we find some evidence that countries with high exposure to the pandemic are less likely to restrict freedom of expression, but the estimates are not robust across different model specifications. The coefficient estimates for the measures of economic development and populist government are not statistically significant.

In sum, these results suggest a positive relationship between pro-democracy mobilization before the onset of the pandemic and the occurrence of pandemic-related policies that restrict freedom of expression. However, the effect appears to be not linearly additive, but the results suggest a distinction between governments that faced no or very low levels of mobilization, which resulted in a low probability of imposing restrictions, and governments facing medium to very high levels of pro-democracy mobilization, for which the probability of pandemic related restrictions of freedom of expression is substantially higher.

To probe the robustness and generalizability of this finding, we – first – analysed the effect of pro-democracy mobilization on an alternative outcome measure, which focuses on incidents of media repression. We collected data from IPI‘s COVID-19 Press Freedom Tracker, which reports attacks on journalists and the press worldwide linked to the pandemic. Using this data, we created a count measure, media attacks, which captures the number of pandemic-related media attacks that occurred in 2020 and an alternative binary measure, which takes the value of 1 if media attacks occurred and the value of 0 otherwise.Footnote50 The results suggest a strong association between the severity of pro-democracy mobilization and the frequency of media attacks. With higher levels of mobilization prior to the onset of the pandemic, governments more frequently engage in attacks on journalists. We also find a positive effect of pro-democracy mobilization on the probability that any media attacks occurred in a country in response to the pandemic.

Second, we explored the relevance of protest goals. Specifically, we analysed mass mobilization in general, i.e. without focusing on democratic goals. We replicated the regression models described above using V-Dem’s more general indicator for mass mobilization, which is again scaled from zero (no mobilization) to four (very high mobilization). The results indicate a positive effect of mass mobilization on the probability of restrictions on freedom of expression, but effect sizes are very small and subject to substantial statistical uncertainty. V-Dem’s indicator of mass mobilization, which covers a broad range of mass events, no matter whether they target political authorities or not, probably grasps too many events that do not present any challenge to the incumbent government. All results from the additional analysis are reported in detail in the appendix.Footnote51

6. Qualitative analysis

This section focuses on probing the plausibility of the link between prior contentious political challenges and pandemic-related restrictions of freedom of expression identified in the quantitative analysis. Following a crucial case logic, we examine cases in which our theoretical argument should most likely be applicable,Footnote52 i.e. countries which had significant anti-government protests in 2019 and, then, saw the introduction of pandemic-related restrictions on the freedom of expression in 2020. In order to select countries, we therefore identified all cases in our dataset which saw very high level of pro-democracy mobilization in 2019 as well restrictions of freedom of expression in the context of the pandemic. This procedure resulted in ten candidate cases. Given that the dynamic at play is most typically observed in intermediate regime types (electoral democracies and electoral autocracies,), we excluded liberal democracies (United States of America, Taiwan) as well as closed autocracies (Sudan). From the remaining seven cases, we ultimately selected Algeria, Bolivia and India in order to have variation in terms of world regions as well as regime type. The North African country of Algeria, according to V-Dem, is a stable electoral autocracy, whereas the Latin American Bolivia and South Asian India have traditionally been categorized as electoral democracies.Footnote53 In what follows, we summarize key developments in these three countries in order to show that pandemic-related restrictions of the freedom of expression can plausibly be considered a governmental response to domestic threats to their power as expressed in preceding mass protests.

In Algeria, a massive protest movement erupted in February 2019. The protests were triggered by then President Abdelaziz Bouteflika’s announcement that he would seek a fifth term in office. But neither the resignation of Bouteflika (in April 2019) nor the holding of new elections (in December 2019), which were boycotted by large parts of the population, successfully tamed the so-called Hirak movement that continued to demand the “removal of the military and political elites”.Footnote54 With a view to the restrictions on the freedom of expression that have been imposed in response to the pandemic, Algeria’s parliament on 22 April 2022 “dealt a blow to freedom of speech when it swiftly adopted a draft law punishing the dissemination of false information”.Footnote55 A few days later, amendments to the Penal Code were reported to “increase prison sentences for defamation, and introduce new penalties including prison sentences for the dissemination of false information”.Footnote56 As Reporters without Borders (RSF) criticized, the “vaguely worded and draconian legislation is designed to tighten the gag on press freedom”.Footnote57 According to RSF, the bill “follows a crackdown on the ‘Hirak’ anti-government street protests and on the Algerian media”.Footnote58 Indeed, throughout 2020, the regime reportedly “arrested and tried dozens of protesters and citizens for expression their opinion”, while overall also “at least twenty-one journalists have been arrested for their coverage of the [Hirak] movement”.Footnote59

In Bolivia, the general elections of October 2019 led to major protests that first targeted the government of Evo Morales but, after Morales’s forced resignation, also confronted the interim government led by Jeanine Áñez.Footnote60 When the pandemic hit the country in March 2020, therefore, Bolivia was governed by a conservative transition government that aimed at preventing the return to power of the left-wing Movement Towards Socialism (MAS), which had governed Bolivia since 2006 and that still had significant popular support (as confirmed later that year when the MAS won the new elections in October 2020 in a landslide). In response to COVID-19, on 25 March 2020, the Áñez administration adopted the controversial Supreme Decree 4200, which included an article stating that all those “who incite non-compliance with this Supreme Decree or misinform or generate uncertainty for the population, will be subject to criminal charges for the commission of crimes against public health”.Footnote61 In response to public and international pressure, decree 4231 (from 7 May 2020) rephrased, but essentially retained this norm,Footnote62 until Decree 4236 (from 14 May 2020) finally repealed the controversial provisions.Footnote63 Commenting on the temporary legal restrictions, PanDem’s expert assessment adds that “Amnesty International, HRW and Civicus argued that this measure threatened freedom of expression”, mentioning “accusations that it was used to persecute political adversaries”.Footnote64 In fact, observers have noted that “hundreds of people associated with the press […] where targeted by the interim government”, some jailed, others threatened and/or attacked by police or pro-government groups. Footnote65 In addition, the Áñez administration closed community radio states, which tend to be close to the MAS party.Footnote66

In India, the adoption of the Citizenship Amendment Act in December 2019 triggered widespread protests. This controversial law offers “a path to citizenship for non-Muslim religious minorities from three neighboring countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan) who did not migrate to the country legally” but “contains no such exemptions for Muslim migrants”.Footnote67 As noted in Peninsula Press on June 18, 2020, the protests, which met with both governmental repression and government-tolerated violence by Hindu-nationalist groups, endured well into early 2020 and only effectively subsided in the context of the pandemic-related lockdown.Footnote68 Already before the pandemic, the Indian authorities used internet shutdowns to constrain the organization and spread of protests.Footnote69 With the health emergency, governments at the central and state level could refer to the Penal Code and the Disaster Management Act in order to prosecute the spread of (supposedly) false news regarding COVID-19.Footnote70 In the context of the national lockdown, journalists were arrested all across the country, which has been seen, by activists, as a clear attempt “to curb criticism against authorities in the name of the health care”.Footnote71

In sum, while the evidence presented in this section is certainly far from conclusive, in all three cases a plausible case can be made that is in line with our overall argument.

7. Conclusion

Previous research has identified the threat perception of governments as a crucial driver of civic space restrictions. When governments perceive civil society actors, including protest movements, to seriously threaten their hold on power, they are likely to implement measures that aim at constraining processes of social organization and mobilization. Such policies are particularly easy to implement in response to external threats, since restrictions can then be justified as necessary means to protect the population. We apply this argument to the COVID-19 pandemic and show that governments have indeed used this external threat as a window of opportunity. Advancing existing research on the causes of “pandemic backsliding”, our study specifically suggests it is the previous experience of contentious political challenges that made governments more likely to misuse the pandemic for political purposes.

We provide evidence that contentious political challenges indeed foster governments to engage in pandemic-related restrictions of freedom of expression. We find a strong effect of pro-democratic mobilization driving the implementation of pandemic-related restrictions of freedom of expression. However, the association between pro-democratic mobilization and restrictions is not linear additive, i.e. the more mobilization the higher the likelihood of restriction. Instead, we find that there appears to be a certain threshold of mobilization after which the probability of restrictions increases substantially.

Additionally, our results from the qualitative analysis of political dynamics in Algeria, Bolivia, and India support the notion that there is a causal link between governments’ threat perceptions as produced by contentious political challenges and the decision to use the pandemic to impose restrictions of freedom of expression.

Two important caveats apply. First, our main indicator of pandemic-related restrictions of freedom of expression likely suffers from measurement error. It includes a mixed bag of policies related to censorship, criminalization of pandemic-related news reports, and attacks on media outlets and journalists. Related to this, the event data underlying our measures was scraped from NGO websites (ICNL, IDEA, and IPI, respectively) and thus may suffer from reporting bias.Footnote72 We also do not have much knowledge about the data-generating process, i.e. what are the criteria for including and categorizing events. We tried to address some of these issues by using a binary outcome measure, which captures if governments implemented any restrictions or not, and, most importantly by aggregating ICNL and IDEA data. However, this does at best mitigate but not solve the problem of data quality. Further research needs to develop clear coding rules for such events and develop more sophisticated frameworks for event categorizations.

Second, our findings are explorative in nature. Because of the crude measurement approach, which basically relates events or aggregated expert judgements from one year with events that occurred in another year, but also because of the analytical methods used, we are not able to identify causal effects but instead only correlations between variables. Therefore, our findings should be interpreted as explorative and of a theory or hypotheses generating nature. The brief case studies, while lending support to the findings from the quantitative analysis, are also overly superficial and do not look in detail into the causal mechanisms at work. Further research should advance more sophisticated quantitative research designs and engage in in-depth process tracing of individual cases to advance the causal interpretation of the evidence.

Given the preliminary nature of our findings, we abstain from deriving specific policy recommendations. However, if the results prove robust in further research the practical implications of these findings are relevant for two reasons. First, freedom of expression is a basic human right and a key ingredient of democracy. Second, if governments are successful in permanently restricting freedom of expression in the wake of the pandemic, this impedes the ability of civil society actors to constrain executive power and to mobilize against civic space restrictions as well as against broader dynamics of democratic backsliding.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (644.5 KB)Supplemental Material

Download (465 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Felix S. Bethke

Felix S. Bethke is Senior Researcher at the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF), in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. His research focuses on civil wars, protest and resistance movements, democratization, and African politics.

Jonas Wolff

Jonas Wolff is Professor of Political Science with a focus on Transformation Studies and Latin America at Goethe University Frankfurt as well as Head of the Research Department ‘Intrastate Conflict’ and Executive Board Member of the Peace Research Institute Frankfurt (PRIF). His research focuses on the transformation of political orders, contentious politics, international democracy promotion and Latin American politics.

Notes

1 ICNL, “COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker.”

2 Freedom House, Democracy under Lockdown, 7–8. See also the 20 case studies in the Law Library of Congress report on “Freedom of Expression during COVID-19” as well as UNICEF’s global report on world trends in freedom of expression and media development. Law Library of Congress, Freedom of Expression during COVID-19; UNICEF.

3 Maerz et al., “Worth the Sacrifice?” 9.

4 Freedom House, Democracy under Lockdown, 7.

5 Kolvani et al., “Pandemic Backsliding,” 2.

6 See Edgell et al., “Pandemic Backsliding”; Kolvani et al., “Pandemic Backsliding”; V-Dem, Autocratization Turns Viral.

7 The distinction between these two dimensions of pandemic-related restrictions roughly corresponds to the two types of “executive overreach” mentioned by Scheppele and Pozen: the degradation of checks and balances, on the one hand, and the violation of civil liberties, on the other. Scheppele and Pozen, “Executive Overreach and Underreach,” 39. For an analysis that focuses on the horizontal dimension of executive overreach, see, for instance, Ginsburg and Versteeg, “The Bound Executive.” For an overview on the specific topic of COVID-19’s impact on elections, see International IDEA, “Global Overview of COVID-19.”

8 Bethke and Wolff, “COVID-19 and Shrinking Civic Spaces”; Rutzen and Dutta, “Pandemics and Human Rights.”

9 See, for instance, Sebhatu et al., “Homogeneous Diffusion of COVID-19 Nonpharmaceutical Interventions.”

10 See Bethke and Wolff, “COVID-19 and Shrinking Civic Spaces”; Cheibub, Hong and Przeworski, “Rights and Deaths”; Maerz et al., “Worth the Sacrifice?”

11 See Bakke, Mitchell and Smidt, “When States Crack Down”; Buyse, “Squeezing Civic Space”; Chaudhry, “The Assault on Democracy Assistance”; Christensen and Weinstein, “Defunding Dissent”; Dupuy, Ron and Prakash, “Hands Off My Regime!”

12 Franklin, “Contentious Challenges and Government Responses.”

13 Barceló et al., “Windows of Repression.”

14 Amnesty International, “Responses to COVID-19”; HRW, “Human Rights Dimensions of COVID-19 Response.”

15 HRW, “Human Rights Dimensions of COVID-19 Response”; Maerz et al., “Worth the Sacrifice?” 5.

16 Generally speaking, restrictions on the freedom of expression constitute an important dimension of the overall phenomenon of shrinking civic spaces, see, for instance, Carothers and Brechenmacher, Closing Space, as well as a key element in the broader trend of democratic regression or autocratization. Diamond, “Democratic Regression in Comparative Perspective”; V-Dem, Autocratization Turns Viral.

17 See Bethke and Wolff, “COVID-19 and Shrinking Civic Spaces,” 367.

18 Carothers, “The Backlash against Democracy Promotion”; Gershman and Allen, “The Assault on Democracy Assistance.”

19 See Borgh and Terwindt, “Shrinking Operational Space of NGOs”; Carothers and Brechenmacher, Closing Space; Howell et al., “The Backlash against Civil Society”; Moore, “Safeguarding Civil Society”; Rutzen, “Civil Society under Assault.”

20 Chaudhry, “The Assault on Democracy Assistance”; Christensen and Weinstein, “Defunding Dissent”; Dupuy, Ron and Prakash, “Hands Off My Regime!”; Heiss, “Amicable Contempt”; Poppe and Wolff, “The Contested Spaces of Civil Society.”

21 Bakke, Mitchell and Smidt, “When States Crack Down”; Chaudhry, “The Assault on Civil Society”; Glasius, Schalk and De Lange, “Illiberal Norm Diffusion.”

22 Poppe and Wolff, “The Contested Spaces of Civil Society,” 472; see Carothers and Brechenmacher, Closing Space; Howell et al., “The Backlash against Civil Society.”

23 Bakke, Mitchell and Smidt, “When States Crack Down”; Chaudhry, “The Assault on Civil Society”; Christensen and Weinstein, “Defunding Dissent”; Dupuy, Ron and Prakash, “Hands Off My Regime!”; Glasius, Schalk and De Lange, “Illiberal Norm Diffusion.”

24 Bakke, Mitchell and Smidt, “When States Crack Down”; Buyse, “Squeezing Civic Space”; Christensen and Weinstein, “Defunding Dissent”; Dupuy, Ron and Prakash, “Hands Off My Regime!”

25 Amnesty International, “Responses to COVID-19”; Bethke and Wolff, “COVID-19 and Shrinking Civic Spaces”; Rutzen and Dutta, “Pandemics and Human Rights”; HRW, “Human Rights Dimensions of COVID-19 Response.”

26 Edgell et al., “Pandemic Backsliding”; Hale et al., “Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker”; ICNL, “COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker”; International IDEA, “Global Monitor of COVID-19”; IPI, “IPI COVID-19 Press Freedom Tracker.”

27 Bethke and Wolff, “COVID-19 and Shrinking Civic Spaces.”

28 Maerz et al., “Worth the Sacrifice?” 7.

29 Maerz et al., “Worth the Sacrifice?” 8–9.

30 Sebhatu et al., “Homogeneous Diffusion of COVID-19 Nonpharmaceutical Interventions”; see also Cheibub, Hong and Przeworski, “Rights and Deaths.”

31 Metternich, “Drawback Before the Wave?” 1.

32 Bloem and Salemi, “COVID-19 and Conflict,” 2–3; see also Press and Carothers, “Worldwide Protests in 2020.”

33 See Kowalewski, “Street Protests in Times of COVID-19”; Pleyers, “The Pandemic is a Battlefield”; Youngs, Global Civil Society in the Shadow of Coronavirus.

34 Grasse et al., “Opportunistic Repression.”

35 Barceló et al., “Windows of Repression.”

36 CSOs include the broad range of formal and informal associations that are neither part of the state nor of the market economy, or of the private sphere: from interest groups, labor unions, and professional associations to classic nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), religious organizations, social movements, and neighborhood associations. In contrast to the broader concept of CSOs, NGOs are usually defined more narrowly as those formally established not-for-profit organizations that claim to represent some general public interest, see Berger-Kern et al., “Defending Civic Space,” 91, note 1; “The Backlash against Civil Society,” 91, note 4.

37 Bethke and Wolff, “COVID-19 and Shrinking Civic Spaces,” 367.

38 See Carothers and Brechenmacher, “Closing Space,” 29; Howell et al., “The Backlash against Civil Society,” 87.

39 See also Law Library of Congress, “Freedom of Expression during COVID-19.”

40 Franklin, “Contentious Challenges and Government Responses,” 701,

41 Gleditsch, Macías, and Rivera, “A Double-Edge Sword?”; Rohlinger and Corrigall-Brown, “Social Movements and Mass Media”; Whitten-Woodring and James, “Fourth Estate or Mouthpiece?”

42 We provide additional details on the coding procedure in the appendix.

43 We use this indicator instead of the more general indicator mass mobilization because the latter explicitly also includes “state-orchestrated rallies”, Coppedge et al., “V-Dem Codebook v11,” 226. The mobilization for democracy indicator, therefore, better grasps what we call contentious political challenges (to the government).

44 Coppedge et al., “V-Dem Codebook v11,” 227.

45 Edgell et al., “Pandemic Backsliding.”

46 Sato and Arce, “Resistance to Populism.”

47 Kenny, “The Enemy of the People.”

48 Kyle and Meyer, “High Tide? Populism in Power.”

49 World Bank, “World Development Indicators.”

50 Note that we excluded reports about attacks on journalists where the perpetrator was a non-state actor, e.g., ordinary citizens or members of a CSO.

51 The appendix also contains additional analyses about potential interaction effects and robustness tests where we employ alternative measures for exposure to the pandemic and populist government.

52 Eckstein, Regarding Politics; on case selection for mixed-method research designs see also Rohlfing, Case Studies and Causal Inference, 61–96.

53 In the time period under consideration, however, Bolivia (in late 2019) experienced a temporary break with democratic rule (with ultimately annulled elections, the coerced resignation of the elected president, and the assumption of an unelected transition government), but a return to a democratic regime in late 2020 (with new elections). India, in contrast, has experienced a gradual process of de-democratization and, according to an updated V-Dem assessment in 2020, crossed the line from electoral democracy to electoral autocracy in 2019. The remaining four countries that we chose not to consider include Ethiopia, Iraq, Venezuela and Zimbabwe.

54 Carnegie, “Global Protest Tracker.”

55 Rachidi, “Algeria’s Hirak.”

56 ICNL, “COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker.”

57 RSF, “Fake News’ Bill.”

58 RSF, “Fake News’ Bill”; see also V-Dem, “The Pandemic Backsliding Project.”

59 Rachidi, “Algeria’s Hirak.”

60 See Wolff, “The Turbulent End of an Era.”

61 As quoted in V-Dem, “The Pandemic Backsliding Project”; see also ICNL, “COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker.”

62 The rephrased article then read: “People who incite non-compliance with this Supreme Decree or disseminate information of any kind, whether in written, printed, artistic and/or by any other procedure that endangers or affects public health, generating uncertainty in the population, will be liable to complaints for the commission of crimes typified in the Penal Code.” V-Dem “The Pandemic Backsliding Project.”

63 V-Dem, “The Pandemic Backsliding Project.”

64 V-Dem, “The Pandemic Backsliding Project.”

65 Farthing and Becker, Coup, 164.

66 See Farthing and Becker, Coup, 162–65.

67 Carnegie, “Global Protest Tracker.”

68 HRW, “Shoot the Traitors”.

69 HRW, “Shoot the Traitors”; for a brief account of the broader context of civic space restrictions in India, see Chaudhry, “The Assault on Democracy Assistance,” 31–35.

70 Law Library of Congress, “Freedom of Expression during COVID-19,” 15–16.

71 Quoted in Law Library of Congress, “Freedom of Expression during COVID-19,” 17; see also ICNL, “COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker.” V-Dem, “The Pandemic Backsliding Project.”

72 Weidmann, “A Closer Look at Reporting Bias.”

References

- Amnesty International. “Responses to COVID-19 and States’ Human Rights Obligations: Preliminary Observations.” Amnesty International. Accessed March 16, 2020. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/pol30/1967/2020/en/.

- Bakke, Kristin M., Neil J. Mitchell, and Hannah M. Smidt. “When States Crack Down on Human Rights Defenders.” International Studies Quarterly 64, no. 1 (2020): 85–96. doi:10.1093/isq/sqz088.

- Barceló, J., R. Kubinec, C. Cheng, T. H. Rahn, and L. Messerschmidt. “Windows of Repression: Using COVID-19 Policies Against Political Dissidents?” Journal of Peace Research 59, no. 1 (2022): 73–89.

- Berger-Kern, Nora, Fabian Hetz, Rebecca Wagner, and Jonas Wolff. “Defending Civic Space: Successful Resistance Against NGO Laws in Kenya and Kyrgyzstan.” Global Policy 12 (2021): 84–94. doi:10.1111/1758-5899.12976.

- Bethke, Felix, and Jonas Wolff. “COVID-19 and Shrinking Civic Spaces: Patterns and Consequences.” Zeitschrift für Friedens- und Konfliktforschung (ZeFKo) 9, no. 2 (2020): 361–374. doi:10.1007/s42597-020-00038-w.

- Bloem, Jeffrey R., and Colette Salemi. “COVID-19 and Conflict.” World Development 140 (2020): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105294.

- Borgh, Chris van der, and Carolijn Terwindt. “Shrinking Operational Space of NGOs – a Framework of Analysis.” Development in Practice 22, no. 8 (2012): 1065–1081.

- Buyse, Antoine. “Squeezing Civic Space: Restrictions on Civil Society Organizations and the Linkages with Human Rights.” The International Journal of Human Rights 22, no. 8 (2018): 966–988.

- Carothers, Thomas. “The Backlash Against Democracy Promotion.” Foreign Affairs 85, no. 2 (2006): 55–68.

- Carothers, Thomas, and Saskia Brechenmacher. Closing Space. Democracy and Human Rights Support Under Fire. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2014.

- Chaudhry, Suparna. “The Assault on Democracy Assistance: Explaining State Repression of NGOs.” PhD diss., Yale University, 2016.

- Chaudhry, Suparna. “The Assault on Civil Society: Explaining State Crackdown on NGOs.” International Organization 76, no. 3 (2022): 549–590.

- Cheibub, Jose Antonio, Ji Yeon Jean Hong, and Adam Przeworski. “Rights and Deaths: Government Reactions to the Pandemic.” 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3645410.

- Christensen, Darin, and Jeremy Weinstein. “Defunding Dissent: Restrictions on Aid to NGOs.” Journal of Democracy 24, no. 2 (2013): 77–91.

- Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, et al. “V-Dem Codebook v11.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, 2021.

- Diamond, Larry. “Democratic Regression in Comparative Perspective: Scope, Methods, and Causes.” Democratization 28, no. 1 (2021): 22–42.

- Dupuy, Kendra, James Ron, and Aseem Prakash. “Hands Off My Regime! Governments’ Restrictions on Foreign Aid to Non-Governmental Organizations in Poor and Middle-Income Countries.” World Development 84 (2016): 299–311.

- Eckstein, Harry. Regarding Politics. Essays on Political Theory, Stability, and Change. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992.

- Edgell, A. B., J. Lachapelle, A. Lührmann, and S. F. Maerz. “Pandemic Backsliding: Violations of Democratic Standards During Covid-19.” Social Science & Medicine 285 (2021): 114244.

- Farthing, Linda, and Thomas Becker. Coup. A Story of Violence and Resistance in Bolivia. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books, 2021.

- Franklin, James C. “Contentious Challenges and Government Responses in Latin America.” Political Research Quarterly 62, no. 4 (2009): 700–714.

- Freedom House. Democracy Under Lockdown. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Global Struggle for Freedom. Washington, DC: Freedom House, 2020.

- Gershman, Carl, and Michael Allen. “The Assault on Democracy Assistance.” Journal of Democracy 17, no. 2 (2006): 36–51.

- Ginsburg, Tom, and Mila Versteeg. “The Bound Executive: Emergency Powers During the Pandemic.” Virginia Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper 2020-52. July 26, 2020. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3608974.

- Glasius, Marlies, Jelmer Schalk, and Meta De Lange. “Illiberal Norm Diffusion: How Do Governments Learn to Restrict Nongovernmental Organizations?” International Studies Quarterly 64, no. 2 (2020): 453–468.

- Gleditsch, Kristian, Martín Macías, and Mauricio Rivera. “A Double-Edge Sword? Mass Media and Nonviolent Dissent in Autocracies.” Political Research Quarterly (2022). doi:10.1177/10659129221080921.

- Grasse, D., Melissa Pavlik, Hilary Matfess, and Travis B. Curtice. “Opportunistic Repression: Civilian Targeting by the State in Response to COVID-19.” International Security 46, no. 2 (2021): 130–165.

- Hale, Thomas, Noam Angrist, Emily Cameron-Blake, Laura Hallas, Beatriz Kira, Saptarshi Majumdar, Anna Petherick, Toby Phillips, Helen Tatlow, and Samuel Webster. “Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker.” Oxford: Blavatnik School of Government ([dataset]; accessed 2020). https://www.bsg.ox.ac.uk/research/research-projects/covid-19-government-response-tracker.

- Heiss, Andrew. “Amicable Contempt: The Strategic Balance between Dictators and International NGOs.” PhD diss., Duke University, 2017.

- Howell, Jude, Armine Ishkanian, Ebenezer Obadare, Hakan Seckinelgin, and Marlies Glasius. “The Backlash Against Civil Society in the Wake of the Long War on Terror.” Development in Practice 18, no. 1 (2008): 82–93.

- HRW (Human Rights Watch). “Human Rights Dimensions of COVID-19 Response.” Human Rights Watch. March 19, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/19/human-rights-dimensions-covid-19-response.

- HRW (Human Rights Watch). “Shoot the Traitors”: Discrimination Against Muslims Under India’s New Citizenship Policy. Washington, DC: Human Rights Watch, 2020. https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/india0420_web_0.pdf.

- ICNL (International Center for Not-for-Profit Law). “COVID-19 Civic Freedom Tracker.” International Center for Not-for-Profit Law. Accessed 10 March 2021. https://www.icnl.org/covid19tracker.

- International IDEA. “Global Monitor of COVID-19’s Impact on Democracy and Human Rights.” ([dataset]; accessed October 7, 2022). https://www.idea.int/gsod-indices/#/indices/world-map?covid19 = 1.

- International IDEA. “Global Overview of COVID-19: Impact on Elections. The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, 8 March 2021. https://www.idea.int/news-media/multimedia-reports/global-overview-covid-19-impact-elections.

- IPI (International Press Institute). “IPI COVID-19 Press Freedom Tracker.” International Press Institute, 2021. https://ipi.media/covid19.

- Kenny, Paul D. “‘The Enemy of the People’: Populists and Press Freedom.” Political Research Quarterly 73, no. 2 (2020): 261–275.

- Kolvani, Palina, Martin Lundstedt, Amanda B. Edgell, and Jean Lachapelle. “Pandemic Backsliding: A Year of Violations and Advances in Response to Covid-19.” Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute. Policy Brief No. 32, 2021. https://www.v-dem.net/media/publications/pb_32.pdf.

- Kowalewski, Maciej. “Street Protests in Times of COVID-19: Adjusting Tactics and Marching ‘as Usual’.” Social Movement Studies. (2020). doi:10.1080/14742837.2020.1843014.

- Kyle, Jordan, and Brett Meyer. “High Tide? Populism in Power, 1990-2020.” Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, 2020.

- Law Library of Congress. Freedom of Expression During COVID-19. Washington, DC: The Law Library of Congress, 2020. https://www.loc.gov/law/help/covid-19-freedom-of-expression/index.php.

- Maerz, Seaphine F., Anna Lührmann, Jean Lachapelle, and Amanda B. Edgell. “Worth the Sacrifice? Illiberal and Authoritarian Practices during Covid-19.” V-Dem Working Paper, September 2020. https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/14/e0/14e03f3b-1c44-4389-8edf-36a141f08a2d/wp_110_final.pdf.

- Metternich, Nils W. “Drawback Before the Wave? Protest Decline During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” 2020. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/3ej72.

- Moore, David. “Safeguarding Civil Society in Politically Complex Environments.” The International Journal of Not-for-Profit Law 9, no. 3 (2007): 3–26.

- Pleyers, Geoffrey. “The Pandemic is a Battlefield. Social Movements in the COVID-19 Lockdown.” Journal of Civil Society 16, no. 4 (2020): 295–312.

- Poppe, Annika Elena, and Jonas Wolff. “The Contested Spaces of Civil Society in a Plural World: Norm Contestation in the Debate About Restrictions on International Civil Society Support.” Contemporary Politics 23, no. 4 (2017): 469–488.

- Press, Benjamin, and Thomas Carothers. “Worldwide Protests in 2020: A Year in Review.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. December 21, 2020. https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/12/21/worldwide-protests-in-2020-year-in-review-pub-83445.

- Rachidi, Ilhem. “Algeria’s Hirak: Defenders of Freedom of Expression.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. January 19, 2021. https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/83682.

- Rohlfing, Ingo. Case Studies and Causal Inference: An Integrative Framework. Houdmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Rohlinger, Deana A., and Catherine Corrigall-Brown. “Social Movements and Mass Media in a Global Context.” In The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, edited by David A. Snow, Sarah A. Soule, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Holly J. McCammon, 131–147. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2022. doi:10.1002/9781119168577.ch7

- RSF (Reporters without Borders). “‘Fake News’ Bill will Tighten Gag on Press Freedom in Algeria.” Reporters without Borders. April 23, 2020. https://rsf.org/en/news/fake-news-bill-will-tighten-gag-press-freedom-algeria.

- Rutzen, Douglas. “Civil Society Under Assault.” Journal of Democracy 26, no. 4 (2015): 28–39.

- Rutzen, Doug, and Nikhil Dutta. “Pandemics and Human Rights.” Just Security, March 12, 2020. https://www.justsecurity.org/69141/pandemics-and-human-rights.

- Sato, Yuko, and Moisés Arce. “Resistance to Populism.” Democratization 29, no. 6 (2022): 1137–1156. doi:10.1080/13510347.2022.2033972.

- Scheppele, Kim Lane, and David Pozen. “Executive Overreach and Underreach in the Pandemic.” In Democracy in Times of Pandemic: Different Futures Imagined, edited by Miguel Poiares Maduro, and Paul W. Kahn, 38–53. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

- Sebhatu, Abiel, Karl Wennberg, Stefan Arora-Jonsson, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “Explaining the Homogeneous Diffusion of COVID-19 Nonpharmaceutical Interventions Across Heterogeneous Countries.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) 117, no. 35 (2020): 21201–21208.

- UNESCO. Journalism is a Public Good: World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development. Global Report 2021/2022. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2022. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000380618.

- V-Dem Institute. “The Pandemic Backsliding Project (PanDem).” Version 5 (repository) ([dataset]; accessed October 7, 2022). https://github.com/vdeminstitute/pandem.

- V-Dem Institute. Autocratization Turns Viral. Democracy Report 2021. Gothenburg: V-Dem Institute, 2021.

- Weidmann, Nils B. “A Closer Look at Reporting Bias in Conflict Event Data.” American Journal of Political Science 60, no. 1 (2016): 206–218.

- Whitten-Woodring, Jenifer, and Patrick James. “Fourth Estate or Mouthpiece? A Formal Model of Media,: Protest, and Government Repression.” Political Communication 29, no. 2 (2012): 113–136. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2012.671232.

- Wolff, Jonas. “The Turbulent end of an era in Bolivia: Contested Elections, the Ouster of Evo Morales, and the Beginning of a Transition Towards an Uncertain Future.” Revista de Ciencia Política 40, no. 2 (2020): 163–186. doi:10.4067/S0718-090X2020005000105.

- World Bank. “World Development Indicators.” 2021. https://databank.worldbank.org.

- Youngs, Richard, ed. Global Civil Society in the Shadow of Coronavirus. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2020.