ABSTRACT

Economic explanations are central to our understanding of popular support for authoritarian regimes. Yet, we do not know to what extent economic evaluations of citizens living under these regimes are amenable to regime propaganda. This article engages with this question by relying on the case of Turkey, where the authoritarian regime led by Erdoğan has been able to sustain its popular support despite years of economic decline. A national developmentalist narrative has been central to the regime’s economic propaganda in Turkey since 2011. Relying on national face-to-face survey data, I first demonstrate that economic misperceptions grounded in this narrative are widespread among supporters of the ruling coalition in Turkey. I then use an online survey experiment to show that exposure to the developmentalist narrative improves economic evaluations among ruling coalition voters. These effects are mediated through the increase in partisan emotions, and they are especially large for non-partisan voters of the ruling coalition. These results help us understand how Erdoğan’s regime could sustain its popular support despite years of economic decline. From a broader perspective, this article demonstrates that scholars of authoritarian regimes need to pay more attention to economic narratives and their affective structures.

Some still consider our 2023 goals as an ordinary middle-long-term developmental plan. Our 2023 goals are a revolt against global conspiracies.

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, 2021

1. Introduction

Authoritarian regimes have an advantage when dealing with public opinion: unparalleled control over the information space.Footnote1 Researchers have demonstrated that authoritarian regimes can use this power to stir nationalist sentiments and shift the voters’ attention away from the economy.Footnote2 Can authoritarian propaganda also improve economic perceptions and expectations, especially during economic decline? Relying on a case study of Turkey, this article argues that narrative-based economic propaganda can help authoritarian regimes to sustain positive economic evaluations among their supporters by evoking emotional reactions and providing cognitive shortcuts.

Under the authoritarian rule of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Justice and Development Party (AKP), Turkey has been experiencing a protracted economic decline for nearly a decade. The economic situation has worsened since 2018, resulting in the significant depreciation of the Turkish currency and high inflation. Despite the bleak economic picture, however, Erdoğan and his ruling coalition have managed to sustain their support among a significant portion of the population.Footnote3 Erdoğan won three consecutive presidential elections between 2014 and 2023, receiving 52% or 53% of the votes. How can we explain this apparent disconnect between the government’s economic performance and popular support?

This article focuses on the economic propaganda employed by the regime to answer this question. A national developmentalist narrative (NDN) has been central to the Erdoğan regime’s economic discourse for the last decade. This narrative has been characterized by the promise of meteoric economic development, the articulation of grandiose infrastructural projects as symbols of the realization of this promise, the description of Erdoğan as the sole political will behind economic development, as well as the description of Western states and domestic opposition groups as forces working against this extraordinary promise.

I combine observational and experimental data to explore the effects of the NDN on voters in Turkey. First, I use data from a face-to-face national survey to demonstrate that the belief in the NDN is highly correlated with popular support for Erdoğan. Building on this, I use an online survey experiment to test the causal effects of the NDN more rigorously. I find that exposing ruling coalition voters to the NDN improves future economic evaluations on both a personal and national level and that this relationship between the NDN and economic evaluations is mediated through the increased association of Erdoğan with hope and enthusiasm.

However, there are also limits to the power of narrative-based economic propaganda. Most importantly, I show that authoritarian propaganda does not affect non-government voters. Despite the regime's attempts in this direction, I also find that the NDN does not evoke any negative emotions towards opposition parties. These results suggest that the power of economic propaganda to broaden the regime’s voter base is limited.

This article enriches our understanding of the formation of economic expectations under authoritarian regimes. There has been minimal attention among political scientists on economic narratives adopted by authoritarian regimes. However, authoritarian control over the economy and the media creates a fertile ground to propagate certain narratives and symbols to shape citizens’ economic assessments. The political instrumentalisation of the utopian promise of fast national development is especially widespread among leaders in the Global South.Footnote4 To the best of my knowledge; this article is the first to explore the individual-level effects of this narrative through an integrative framework, combining a descriptive account with a rigorous study of causal mechanisms. Furthermore, my article demonstrates that economic propaganda evokes enthusiasm and hope among regime supporters. As such, this article draws attention to the role of positive partisan emotions under authoritarianism, a topic that has been largely ignored in the literature.Footnote5

The rest of the article is formed of six sections. The following two sections are mainly theoretical and qualitative. First, I introduce national developmentalism as a strategic narrative and propaganda and discuss why Turkey is an appropriate case to study mass support under authoritarianism. Second, I theorize how the NDN in Turkey affects voters’ economic and emotional evaluations. Two quantitative sections follow, in which I test arguments laid out in theory sections through a national sample and an online survey experiment. I conclude with the discussion and conclusion sections.

2. National developmentalism as a narrative

2.1. Narratives in politics and national developmentalism

From a political perspective, we can analyse narratives along three dimensions: temporal, collective, and symbolic.Footnote6 The temporal dimension is central to the definition of narratives: narratives are sequential stories, combining specific interpretations of past and current events with a vision of the future. Second, narratives include references to actors and groups. By focusing on this collective dimension, we can explain how narratives contribute to forming group identities. Finally, we should also pay attention to how narratives are inscribed and embodied in the material world through the reorganization of the environment and human practices. Capturing this symbolic dimension is essential to understand how the power of narratives is reproduced through daily practices.

Political actors can use narratives strategically as “a communicative tool to attempt to give determined meaning to past, present, and future to achieve political objectives.”Footnote7 Strategic narratives are important in both democratic and authoritarian countries.Footnote8 However, it can be argued that authoritarian control over the information space and the economy creates even more room for authoritarian regimes to instrumentalise narratives for political goals. Authoritarian regimes have vast resources to propagate narratives, not only through mass media but also through the re-organization of the material space. Procedures and institutions that slow down this process, such as parliamentary and judicial oversight or independent media, do not exist under authoritarianism. Furthermore, opposition and civil society actors have a limited capacity to challenge these narratives. Hence most citizens do not have access to critical information to evaluate them.

Economic narratives play an important role in politics, mediating the relationship between objective economic conditions and political preferences.Footnote9 This article studies the developmentalist economic narratives which are especially popular in the Global South. These narratives imagine the national economy as a coherent object that competes with other national economies. According to the developmentalist perspective, fast economic development of the country and a “great leap” into the league of advanced countries is possible. As such, this should be the ultimate national goal as it can solve all country problems and bring joy and harmony to the entire nation.

Political scientists have predominantly studied developmentalism in regard to associated policy ideas and their outcomes.Footnote10 However, the developmentalist conceptualization has a utopian appeal that exists independently from specific policy ideas.Footnote11 Political leaders with various ideologies can attempt to instrumentalise this utopian core to build mass support for their political agendas. For example, it is possible to find historical examples of the use of developmentalist narratives under both communist regimes, such as the USSR under Stalin’s ruleFootnote12 and China under Mao’s ruleFootnote13 and democratic regimes, such as Brazil under Kubitschek’s rule.Footnote14

Examples of the strategic use of developmentalist narratives by contemporary authoritarian regimes are not hard to find. Paget argues that Magafuli’s regime in Tanzania used the imperative of development to justify the authoritarian rule in the country.Footnote15 According to Sinha, developmentalism is part of Modi’s appeal in India, as it is grounded in his image as a “development man” and his grandiose promises, such as constructing the world’s largest statue, bringing in the fastest train, making India like Singapore, and building 200 smart cities.Footnote16 Similarly, Huda argues that contemporary authoritarian regimes use energy megaprojects to perpetuate national and transnational narratives, foster patriotism, and gain legitimacy.Footnote17

Strategic developmentalist narratives share some common properties. Regarding the temporal dimension, all developmentalist narratives focus on the utopian promise of development that will take place in the future. The collective dimension of all developmentalist narratives is built on the division between the nation and advanced nations. Finally, regarding the symbolic dimension, all developmentalist narratives produce and celebrate material symbols that represent the realization of developmentalist promises. Political actors will also add new elements to their developmentalist narratives in line with their political agendas and ideologies. For example, the past can be depicted as a state of deprivation, as was the case with Stalin's communist developmentalism,Footnote18 or a state of glory, as was the case with Magafuli’s restorationist developmental nationalism.Footnote19 The competition at the international level can be depicted as benign or existential. The nation, i.e. the “us” of the narrative, can refer to the entire nation or only some parts of it. Finally, the symbolic dimension of developmentalist narratives can refer to industrialization and factories, construction and infrastructural projects, or consumer goods.

2.2. The Turkish case: Erdoğan’s national developmentalism

Under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) came to power in Turkey in 2002 through a free and fair election. Since then, the country has gone through a period of autocratization and personalization, following a trajectory similar to countries such as Russia and Venezuela.Footnote20 Today’s Turkey is a typical case of electoral authoritarian regimes, which combine some competitive electoral properties with the de facto authoritarian control of the government over the political and social space.Footnote21 Given the strength of popular support of Erdoğan’s regime in the face of a deep economic crisis, as discussed in the Introduction, Turkey is a likely case to document the relationship between authoritarian propaganda and performance evaluations.Footnote22

The power of Erdoğanist propaganda is usually explained with reference to populism and nationalism.Footnote23 While these are important to understand the regime’s policies and popular appeal, they should not overshadow the significance of performance evaluations for the survival of the authoritarian regime in Turkey. Academic researchers repeatedly find that economic evaluations are significant predictors of support for the AKP, even when accounting for partisanship, socio-demographic factors, and ideological self-positioning.Footnote24 Importantly, however, the gap between economic perceptions of government voters and opposition voters is increasingly growing,Footnote25 and media preferences are predictive of economic assessments.Footnote26 These findings suggest that, as Turkey’s economic crisis deepens, Erdoğan benefits from the authoritarian media space to preserve his image of competency. The AKP has become increasingly more dominant in the media since it came to power, and the media coverage of the party has become increasingly more positive.Footnote27 Currently, none of the popular TV channels in Turkey can openly criticize the regime in its news programmes; the only exception is Fox TV, owned by Fox Networks Group. However, media domination is not enough to explain the success of authoritarian propaganda. It is also necessary to pay attention to the content of the message and how its audience receives it.

Erdoğan’s economic propaganda is built on a national developmentalist narrative, which gradually emerged throughout the first decade of the AKP’s rule in Turkey. To begin with, the promise of historical economic development is at the core of the NDN. The utopian articulation of “development” in the AKP discourse has crystallised with the 2011 election campaign.Footnote28 “Turkey is ready, Target: 2023” was the official slogan of this campaign and making Turkey one of the top 10 economies by 2023 was the most significant promise of the campaign period.Footnote29 2023 is a carefully selected date with high symbolic and aesthetic significance; it is the centenary of the foundation of the Turkish Republic. The goal itself, on the other hand, is a grandiose one. According to World Bank data, Turkey was the eighteenth biggest economy in the world by 2011, and India, the world’s tenth biggest economy by that time, had an economy that was more than twice the size of Turkey’s economy. While the goal itself was unrealistic, the appeal was grounded in grandiosity. The promise of historic economic growth, along with references to 2023, has become a central part of the AKP’s propaganda since then. Most tellingly, all campaigns for general elections after 2011 used similar slogans, such as “National Will, National Power, Target 2023,” “New Turkey, New Power, Target 2023,” and “It is Turkey’s Time.”Footnote30

The NDN includes references to political actors and groups, which turn it into a collective partisan narrative. According to the NDN, the sole political will behind the 2023 vision is Erdoğan; he is the one who first dreamt of it, and he is the one who has pushed for it since then. Thus, the NDN is important in building Erdoğan’s image as a competent and visionary leader. On the other hand, references to political actors that work against Turkey’s development have also gradually become a central part of the narrative. These references were added when the regime started to be faced with economic and political setbacks. In those moments, the regime’s propaganda machine reversed the developmentalist frame to explain why such a successful government would face problems and discontent. For example, “foreign conspirers that are unhappy about Turkey’s economic development” was presented as the reason behind the Gezi protests, both by Erdoğan and the other regime actors.Footnote31 Public surveys conducted during that period show that this narrative was successful; around 80% of AKP supporters believed that foreign conspirers planned Gezi protests.Footnote32 At other times, foreign states were ridiculed. For example, to exaggerate the significance of the new airport, which was another symbol of the NDN, the regime media frequently claimed that Germany was jealous and dismayed about this development.Footnote33

Finally, the symbolic dimension of the NDN relies on a set of grandiose construction projects, such as two suspension bridges in Istanbul, a new airport in Istanbul, an artificial water leeway between the Marmara Sea and the Black Sea, as well as two new “cities” in Istanbul. These projects were first introduced as election promises in 2011, being the backbone of the AKP’s newly announced 2023 vision. They helped voters imagine what a top-ten Turkey would look like, hence turning the abstract goal of “Target: 2023” into a concrete representation. Their function as symbols of the developmentalist promise still continues. Several of these projects have since been completed and were opened to service. The AKP’s propaganda machine vividly celebrated these openings, arguing that they heralded that the 2023 vision was becoming a reality.Footnote34

To be clear, it is impossible to deny the economic significance of these megaprojects, especially in terms of the political economy of the authoritarian regime in Turkey.Footnote35 For example, the new Istanbul airport, which opened in 2019, has already become the busiest airport in entire Europe in terms of total passenger traffic. However, it is also crucial to note how the authoritarian regime in Turkey has always presented these megaprojects to the Turkish public within a narrative framework.

For example, one of the symbols of Erdoğan’s national developmentalist narrative (NDN) is the Osmangazi Bridge – a suspension bridge built over the Gulf of Izmit. The bridge was one of the AKP’s campaign promises in the 2011 election period, and it was later named after Osman Gazi, the founder of the Ottoman Empire. The bridge's construction started in 2013, and it was ceremoniously opened to service on 30 June 2016. Pro-regime TV channels made live broadcasts from the bridge throughout the week, dubbing 30 June “a historic day” and “the day of pride.” The speech that Erdoğan gave during the opening ceremony includes references to all dimensions of the NDN:

We will continue to be the biggest friend of those who sees us as a friend. Similarly, we won’t hesitate to take any measure against those who nurture enmity toward us. No one can stand in our way in the new era. No one will be able to stop us from achieving our goals for 2023.Footnote36

3. How do developmentalist narratives affect regime support: the theory

How does the NDN affect voters’ economic evaluations in Turkey? This section aims to develop a theoretical explanation for this question, drawing on the literature in public opinion, political psychology, and cultural studies.

3.1. National developmentalist narrative and emotions

Emotions are central to various forms of political behaviour, such as the formation of collective identities, political mobilization, and motivated reasoning.Footnote37 There is a very close relationship between narratives and emotions. By simplifying and dramatizing the complex reality surrounding us, narratives can play an important role in generating emotional reactions. Emotions, in return, can explain why some narratives are more powerful and attractive than others to the audience.Footnote38

I argue that the NDN cultivates affective ties between the ruling coalition voters and Erdoğan thanks to the powerful vision of the future that it provides. According to the appraisal theory of emotions, goal-orientation underlies all emotional reactions; positive emotions are derived from the cognitive appraisal of approaching a desirable goal, whereas negative emotions are associated with the appraisal of obstacles.Footnote39 In parallel with this insight, studies of charismatic leadership list “offering a powerful future vision” as one of the key elements of charismatic bonds between the leader and the follower, as well as being central to the elicitation of positive emotions from the followers.Footnote40 Similarly, McLaughlin et al. demonstrate that political ads that have a narrative format evoke emotional reactions from voters by stimulating them to imagine future scenarios.Footnote41 The NDN offers an appealing future vision for government voters, promising welfare, prosperity, and status. The goal of being one of the leader countries in the world may be grandiose, but it is the grandiosity of promises that arouses the audience, so long as these promises are made by “credible” leaders.Footnote42

The NDN also draws on existing identities to strengthen its affective appeal. For voters with strong national identification, the NDN offers a vision in which Turkey has a higher status in the international arena. International status hierarchies are closely associated with emotional reactions, and they are especially central to Turkish collective identity.Footnote43 For voters of the AKP, the NDN offers the pride of being a part of the political party that has achieved improving Turkey’s international status.

3.2. National developmentalist narrative and economic evaluations

I argue that the NDN improves economic evaluations both by offering cognitive shortcuts to evaluate the performance of the economy and through its emotional effects.

To begin with, the NDN provides a framework to evaluate the economic performance of the regime, and this framework heavily favours the regime. A large amount of literature in political science suggests that people use national economic indicators more than personal economic indicators to judge the incumbent government’s economic performance.Footnote44 We know less about how people decide on something as complex as the “national economic situation.”Footnote45 Recent research shows that international comparisons, such as cross-national performance comparisons and references to foreign socioeconomic conditions, can influence how people judge domestic performance.Footnote46 The NDN, by definition, draws attention to international comparisons of the economy. Crucially, the narrative also provides “benchmarks” that can be used to judge Turkey’s comparative economic performance. These are the symbols of the NDN: bridges, airports, fast train lines etc. These projects are frequently described in comparison to their counterparts in the Western world. For example, when Istanbul airport was completed, the regime media compared this with Frankfurt Airport, one of the largest airports in the world. The comparison underlay the claim that Germans were envious of Turks and the new Istanbul airport.Footnote47 Given that building these infrastructural projects is easier than creating millions of new jobs, the NDN provided a cheaper way to construct the image of competency in the eyes of Turkish people who regarded the regime media and Erdoğan as credible and who engaged with the narrative.

Second, it is also important to establish the link between the narrative structure of the NDN, which generates emotional reactions, and the NDN’s impact on economic evaluations. According to the affective intelligence theory, individuals who are angry or enthusiastic are more likely to rely on their existing dispositions during the reasoning process.Footnote48 In politics, this means that these individuals will rely more on the source of the message rather than its content when they process a message, and thus, they will stick more closely to their partisan and ideological commitments.Footnote49 If the NDN is evoking partisan emotions among certain individuals, as argued above, we would expect these people to bring their economic evaluations in line with their partisan preferences and adopt a motivated form of reasoning.

4. Study 1: national survey data

I have so far argued that the national developmentalist narrative (NDN) has been the backbone of the Erdoğan regime's economic propaganda and has successfully affected Turkish voters’ economic and affective evaluations. This section provides an initial test of these arguments with a national and face-to-face survey.

4.1. Introducing the data

The data used in this section comes from a survey conducted by Konda Survey Company, one of Turkey’s most reputable survey companies, in October 2018. The survey was conducted face-to-face with 2676 respondents from 148 districts, randomly chosen from a total of 49000 districts through a multi-stage, stratified cluster sampling design.Footnote50 Age and sex quotas were implemented at the district level. The survey took place four months after the 2018 general election, in which Erdoğan was re-elected as president in the first round with a vote share of 53%. That election year was a challenging year for the Turkish economy. The Turkish lira depreciated 72% against the dollar between January and October 2018, and most of the decline happened after the election. Steinberg shows that the currency crisis reduced support in the government.Footnote51 The Konda survey was conducted immediately after this sudden depreciation. It, therefore, allows us to study public opinion in the face of an economic crisis.

In addition to a wide range of questions, survey participants were also asked to express the extent to which they agreed with two statements that were directly linked to the NDN: “Turkey will be one of the top ten economies in the world by 2023” and “Germany is jealous of our third airport.” As detailed in the theory section, these two questions capture core dimensions of the NDN: the promise of historical economic development by 2023, Istanbul airport as a symbol of the NDN, and Western states’ uneasiness about and hostility towards Turkey’s economic development. The correlation between these two statements is 0.65.

4.1.1. How widespread is the belief in the NDN?

I start my analysis by exploring the proportion of the Turkish electorate who believe in the NDN. lists the proportions for three groups: respondents who voted for the ruling coalition (AKP and MHP) in the 2018 general election,Footnote52 respondents who did not vote for these parties in the same election, and the entire sample. I will call the first group of voters “the ruling coalition voters” in the rest of this article.

Table 1. Proportion of the Turkish electorate agreeing and disagreeing with the NDN, with samples divided based on past vote choice.

reveals that nearly half of the ruling coalition voters believe in both statements.Footnote53 The results are striking, given that these statements reflect severe misperceptions about the economy in Turkey. Results also reveal that Turkish voters are polarized over the NDN, as two equally sized groups of strong believers and strong deniers of the NDN formed along partisan lines. 48% of respondents who voted for the AKP or MHP in the last election agreed with both statements, while only 11% of other voters agreed with them both. Symmetrically, only 9% of the ruling coalition voters express disagreement with both statements, while half of the remaining respondents reject both statements. Given that the statements asked in the survey did not include any partisan cues, the partisan divide in responses verifies the partisan nature of the NDN.

4.1.2. Is the belief in the NDN correlated with regime support?

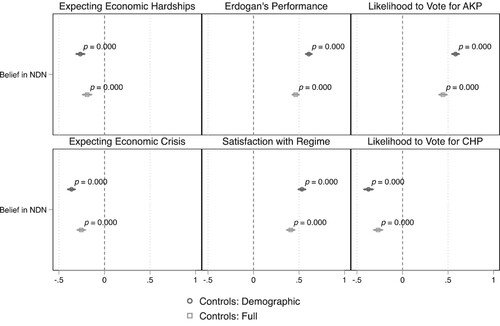

The Konda survey also allows us to measure the strength of the relationship between the NDN and regime support while controlling for other demographic and political variables.

I use six variables created from six different questions as outcome variables. First, the survey includes two questions to measure future economic expectations: “the expectation of personal economic hardship in the coming months” and “the expectation of an economic crisis in the coming months.” Furthermore, one question asks respondents about the level of satisfaction with democracy in the country; one question asks respondents to evaluate Erdoğan’s performance; and a series of questions ask respondents how likely they are to vote for each of the political parties in Turkey, including the AKP and the main opposition party CHP, in an immediate election. These are the six questions that are used to measure regime support. In order to simplify the analysis, I combine two NDN items into a single variable taking their row average. This variable, called “belief in the NDN,” is used as the independent variable in this analysis.

Two groups of control variables are added to the models. The first group is formed only of demographic variables: age, level of education, household income, and gender. The second group includes a set of political and attitudinal variables: religiosity, populism scale, conspiratorial thinking scale, ideology, political knowledge, experiencing personal economic hardship in the last year, voting for regime parties in the last election, and voting for opposition parties in the last election. A complete list of survey questions used to create these variables and descriptive statistics summarizing the properties of these variables can be found in the Online Appendix Section 3. Results are presented in .

Figure 1. OLS results measuring the relationship between the belief in the NDN and political and economic outcomes.

shows that the belief in the NDN is strongly associated with all indicators of regime support, except the likelihood of voting for the opposition party. These relationships are substantially significant as well. For example, the belief in developmentalism increases Erdoğan’s performance evaluations by 0.3 standard deviations, even when we control for a wide range of demographic and political variables.

To summarize, believing that Turkey is experiencing historic economic growth and the developed world is envious of this growth is a vital component of regime support in Turkey. However, the observational nature of the data limits the reliability of causal claims we can make over these relationships. As explained above, observational data also does not allow us to directly study emotions’ mediating role. I tackle these issues in the next section with the help of an experimental design.

5. Study 2: online survey experiment

I conducted an online survey experiment in Turkey during the Fall of 2021 to explore the causal effects of the national developmentalist narrative (NDN).Footnote54 The goal of the experimental design was to make people randomly assigned to the treatment group think about the NDN and then measure what kind of attitudinal and emotional changes would occur among those people. If the belief in the NDN were simply a result of partisan cue-taking from the AKP elites and Erdoğan, without any further political implications, we would not see any spillover effects of thinking about the NDN on questions that were not directly about the content of the NDN, such as political emotions about political actors. However, as explained below, I have found significant attitudinal and emotional changes in respondents assigned to the treatment condition.

5.1. Introducing the data

Participants in the experiment were recruited through Facebook paid advertisements, which then directed them to a survey page hosted on Qualtrics.Footnote55 The survey was registered on 21 September.Footnote56 The data collection lasted from 22 September to 1 October. In total, 1543 people participated in the survey, 773 of which had voted for the AKP or MHP in the last general election in 2018.

The advantage of recruiting participants online and letting them complete the survey through their own devices is increasing the treatment's power. This was especially important as I intended to evoke emotions through a set of questions and images. The challenge, on the other hand, is to reach a representative sample. The demographic distribution of respondents in this study is available in the Online Appendix Section 4.3, along with the comparison to the probability-based Comparative Study of Electoral Systems (CSES) 2018 Turkey sample. I used targeting tools offered by Facebook and incentive-based advertisements to increase the diversity of participants in the sample.Footnote57 My online sample diverges from the national population, measured through the CSES sample, primarily in education levels. Compared to the national population, my sample under-represents people with less than a secondary school degree (57% to 23%) and over-represents people with a university degree (36% to 18%). Overall, I find the differences between my sample and the national population acceptable, as my causal inferences in this section rely on random assignment into treatment groups.

The survey lasted less than ten minutes, and a complete list of questions asked in the survey is provided in Online Appendix Section 4.4. Outcome variables will be introduced in the relevant parts of this section; a complete list of all questions and outcome variables used in the study, along with descriptive statistics, is available in the Online Appendix Section 4.6.

5.2. Introducing the treatment

Around half of the survey participants were randomly assigned to a treatment condition after answering pre-treatment questions. Randomization was conducted through Qualtrics. Balance tests, presented in Online Appendix Section 4.2, demonstrate that randomization worked as planned with only minor differences between treatment and control groups.Footnote58

The treatment aimed to make respondents think about the NDN by showing propaganda images and asking questions to increase engagement. Respondents in the treatment condition were asked five questions about the NDN before they were directed to post-treatment questions. Images of Osmangazi Bridge and Istanbul Airport accompanied the questions in the treatment group. These images were taken from pro-regime websites. Two of them also included logos of pro-regime media outlets and propaganda phrases pasted on the images, such as “Germans are in dismay.” On the other hand, survey questions were objectively phrased, e.g. “Some media outlets claim that Germans are envious of the third airport. Do you agree with this claim?” Online Appendix Section 4.5 includes the complete treatment, including images and questions. Respondents in the control group did not see any questions or images.

The ruling coalition and other voters were separated at the data analysis stage based on the registration plan. The ruling coalition voters are respondents who said that they voted for the AKP or MHP in the last election, i.e. the 2018 legislative election, during the pre-treatment part of the survey. Other voters are all respondents who either voted for other parties or did not vote. Pre-registered hypotheses referred to ruling coalition voters, but I have also tested the influence of the NDN on other voters.

Finally, I conducted moderation and mediation analyses to interpret the causal effects of the NDN better. Moderation analyses explored whether the effects of the NDN depended on partisanship strength. Mediation analysis tested whether emotions mediated the relationship between the treatment and the change in economic and political preferences.

5.3. Analysis and results

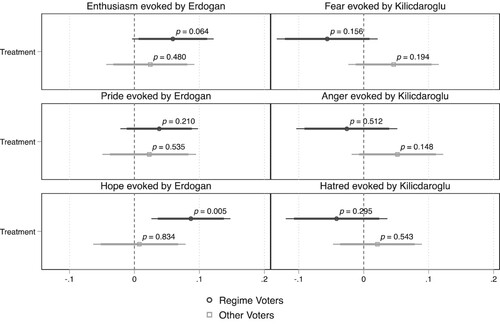

5.3.1. Does exposure to the NDN affect partisan emotions?

One of the main arguments of this article is that the NDN evokes affective reactions from the ruling coalition voters. Respondents’ affective reactions were measured through twelve self-reported questions. I asked respondents to what extent Erdoğan and Kilicdaroglu (the leader of the main opposition party, CHP) evoked emotions of enthusiasm, pride, hope, fear, anger, and hatred from them. As pre-registered, I only analysed the emotions of enthusiasm, pride, and hope for Erdoğan and the emotions of fear, anger, and hatred for Kilicdaroglu. The emotions scale ranged from 0 to 10. I analysed the ruling coalition and opposition voters separately following the registration plan.

Results, shown in , show that the ruling coalition voters who were exposed to the NDN were more likely to associate enthusiasm and hope with Erdoğan. More specifically, the ruling coalition voters’ association of Erdoğan with hope and enthusiasm increased by around 0.1 standard deviations when asked whether they agreed with the premises of the NDN. These results verify that the narrative structure of the propaganda is effective at building affective and charismatic ties between Erdoğan and his supporters.

Unlike hope and enthusiasm, we do not find any relationship between the treatment and pride. There are two alternative explanations here, which are probably both true. Firstly, among the ruling coalition voters in the control group, the level of pride was higher than levels of enthusiasm and hope, as can be seen in Online Appendix Section 4.6. Thus, there was less room to manipulate pride. In addition to this, it can be argued that the origin of pride is different from the origin of enthusiasm and hope among the ruling coalition voters. Pride might be associated with partisan group identities and feelings of superiority vis-a-vis other partisan groups in Turkey. In contrast, hope and enthusiasm are associated with the vision of the future.

We also do not find any relationship between the NDN and negative partisan emotions. This finding is in line with the finding from the national study, which showed no relationship between belief in the NDN and the likelihood of voting for the opposition party. Finally, we do not find any effect of the treatment on voters who did not vote for regime parties in the last election. This is an important finding which shows the limitations of narrative-based economic propaganda.

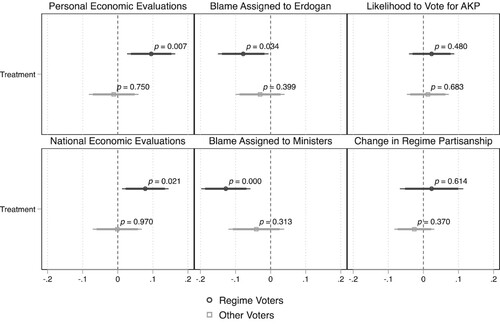

5.3.2. Does exposure to the NDN affect economic evaluations?

I use four variables to measure economic evaluations. The first two variables are future economic expectations on an individual and national level. Each averages responses to one positively worded and one negatively-worded and reverse-coded question on a scale of 1 to 5. The third and fourth variables measure to what extent respondents believe that Erdoğan or ministers of the economy are to blame for the country's economic troubles. These variables are produced from two separate questions, asking respondents to express blame assignment on a scale of 1 to 5.

The first two columns of present the results, which consistently demonstrate that exposure to the NDN improves economic evaluations among the ruling coalition voters. The ruling coalition voters not only express positive economic expectations for the future direction of the economy and their personal economic situation, but they also put less blame on Erdoğan and his ministers for the current economic troubles in the country.

5.3.3. Does exposure to the NDN affect political preferences?

Finally, I use two variables to measure political preferences. The first variable measures how likely respondents were to vote for the AKP if there was an immediate election. The scale ranged from 1 to 5. The second variable was built on the partisanship item used in the CSES. I asked respondents whether they felt close to any political party and how close they felt (if they felt at all), from 1 to 3. This set of questions was asked both before and after the treatment. As indicated in the registration plan, I created a variable ranging from – 3 to 3, measuring the individual-level change in partisanship due to the treatment.

Results are presented in the third column of . An unexpected result is that we do not find any relationships between the treatment and political preferences. As I have already established that the NDN improves both economic and affective evaluations, my only explanation is that the room for experimental manipulation was more limited in these questions than in other questions. The analysis of heterogeneous treatment effects in the following subsection allows us to explore if this was the case.

5.3.4. Exploring causal effects: the role of non-partisans and emotions

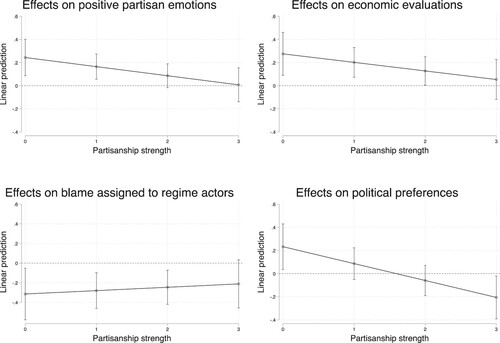

I ran moderation and mediation analyses over the ruling coalition voters’ responses to better understand causal effects.

Firstly, I explored how partisanship and its strength moderated the effect of the treatment on emotional, economic and political responses. Partisanship is a significant factor in Turkish politics, and it is essential to see whether there are any distinctions between strong partisans and non-partisans concerning the effect of the NDN. I created aggregate measures to simplify the analysis by taking row averages of relevant variables. All three variables of positive partisan emotion (hope, enthusiasm, and pride) were combined to form an aggregate positive emotions variable; personal and national economic evaluations were combined to form an aggregate economic evaluations measure; blame assigned to Erdoğan and ministers were combined to form an aggregate blame assignment variable, and vote and partisanship were combined to create an aggregate political preferences measure.

The results, presented in , consistently demonstrate that treatment effects were strongest among non-partisan ruling coalition voters. This means that the NDN helps the regime to sustain its support among one of the most crucial voter groups in terms of the regime's survival, that is, voters who voted for regime parties in the last election but do not feel close to those parties currently. Given that these people are probably more likely to abstain or defect in the next election than strong partisans, these results reveal that the NDN serves an important political function.

Figure 4. The moderating effect of partisanship on the relationship between developmentalism treatment and aggregate measures.

Interestingly, causal effects were nearly absent among strong partisan ruling coalition voters, which formed around 30% of ruling coalition voters in the sample. We can interpret these results as an indication of ceiling effects. For example, while the average level of positive partisan emotions among strong regime partisans was nine over 10, the average level of positive partisan emotions among the rest of the ruling coalition voters was 6.2. Similarly, these results suggest that our inability to find the effects of the NDN on political preferences was because of the lack of room for experimental manipulation among strong partisans. Exposure to the NDN does move political preferences among non-partisans.

Second, I ran three different mediation analyses, exploring how the change in aggregate positive emotions variable mediates the effect of the treatment on three different variables: Aggregate economic evaluations measure, aggregate blame assignment variable, and aggregate political preferences measure. Results are presented in .

Table 2. Mediation analysis: Treatment, Emotions, Economic and Political Preferences.

These results demonstrate that for each of the three outcome variables, there is a statistically significant effect between the treatment and the outcome variable that is mediated through partisan emotions. The size of this effect is around 0.1 standard deviation. This corresponds to more than 40% of the effect on economic evaluations and 30% of the effect on blame assignment. It is important to note that positive emotions fully mediate the significant and positive relationship between the treatment and pro-regime political preferences. Thus, we can conclude that evoking positive emotions is crucial to economic propaganda in Turkey.

6. Discussion: the political function of developmentalist propaganda

Empirical findings in this article raise two questions crucial to understanding the political function of developmentalist propaganda in Turkey. First, if the national developmentalist narrative (NDN) promises economic development for the entire nation, why is it only effective among voters of the ruling coalition? Second, if the NDN’s effects are limited to people who voted for ruling parties in the previous election, how does the NDN promote the regime’s political agenda?

To begin with the first question, it is not surprising that exposure to the NDN does not affect opposition voters in Turkey. Regime critics living in authoritarian countries develop distrust towards the regime’s propaganda channels and any news spread by them.Footnote59 As a result, it is harder to influence the political opinions of these voters through propaganda. Given that the NDN promotes serious economic misperceptions, such as the claim that Turkey will be one of the top ten economies in the world by 2023, it is probable that opposition voters are more cautious when engaging with these claims. Furthermore, the NDN includes partisan elements, such as “the heroic role of Erdoğan” and “obstacles laid out by opposition parties.” These partisan elements might discourage opposition voters from engaging with the narrative. As the concept of “narrative proximity” describes, a certain level of resonance between the narrative and the audience is necessary for the narrative to be influential.Footnote60 On the other hand, partisan elements of the NDN can make it easier to evoke pro-AKP emotions among voters close to the regime for sociological, ideological, or economic reasons.

This brings us to our second question: how does the NDN help the regime if its effects are concentrated among people who already voted for ruling parties in the last election? To answer this question, it may be helpful to underline the difference between partisan cue-taking and the emotional mobilization of partisans. It is a well-established finding in political science literature that partisans in democracies follow cues from in-party elites to form their opinions.Footnote61 This article contributes to the literature by demonstrating that authoritarian propaganda, built on developmentalist narratives, also can influence how partisans evaluate the economic situation.

Beyond this, however, results also reveal the emotional effects of propaganda. Partisans exposed to developmentalist propaganda become more likely to associate Erdoğan with hope and enthusiasm. These emotional effects talk to the broader literature on emotions and partisanship.Footnote62 According to this literature, emotions influence voters’ reliance on their partisan identities while forming political attitudes and evaluations. People who feel enthusiastic or angry are likelier to develop a political opinion aligning with their partisan identity. Second, emotional appeals play an essential role in mobilizing the partisan base. For example, partisans who feel positive or negative emotions are likelier to share partisan information or vote than partisans who do not feel the same emotions.Footnote63 Emotional appeals are essential for mobilizing weak partisans.Footnote64

The findings in this article point in the same direction. First, the mediation analysis suggests that the emotional nature of developmentalist propaganda plays a vital role in convincing voters of the ruling coalition to update their economic expectations in a positive direction. Furthermore, developmentalist propaganda sustains and strengthens partisan ties among voters of the ruling coalition by evoking partisan emotions. These findings should be considered in the context of the ongoing economic decline in Turkey. As shown above, the effects of developmentalist propaganda are most substantial among voters who voted for regime parties in the last election but do not define themselves as partisans. These non-partisan voters would normally be the voters most likely to defect in an upcoming election because of the economic crisis. Thus, developmentalist propaganda helps the regime to preserve its support base under difficult economic and political conditions.

7. Conclusion

Arguably, the AKP in Turkey has been more successful at managing the perceptions of the economy than managing the economy itself. Despite the economic decline that was ongoing for nearly a decade, the AKP and its leader Erdoğan secured another electoral victory in 2023. The national developmentalist propaganda preserved its central place in the AKP discourse during the election period, as the AKP and Erdoğan replaced temporal references to “2023” with an ostentatious slogan serving the same purpose: “The Century of Turkey.”

This article demonstrates that the national developmentalist propaganda in Turkey has built affective ties between Erdoğan and his voters, improved economic evaluations, and increased political support for the regime. Observational and experimental data support these arguments. Observational survey data confirms that a significant portion of ruling coalition voters in Turkey hold economic misperceptions originating from the national developmentalist narrative. It could be argued that this relationship was a result of the partisan cue-taking, with no further political consequences. However, the survey experiment overcomes this argument by showing that exposure to the developmentalist narrative results in emotional and attitudinal changes that can be observed through questions that are not directly related to the developmentalist narrative.

This article improves our understanding of support for authoritarianism in Turkey and other countries. Whether authoritarian regimes could improve their performance evaluations through propaganda has been an open question. This study shows that the narrative structure, which offers a powerful and appealing vision for the future, can help authoritarian regimes escape the responsibility for current economic troubles and strengthen affective bonds with their voters. As such, this article offers a new perspective to understand the development of partisan and affective attachments towards authoritarian parties.

Going beyond the case of Turkey and authoritarianism, this article also contributes to studying ideological formations in the Global South. Historians and anthropologists have long pointed to the role of utopian developmentalist ideologies in developing countries.Footnote65 However, political scientists’ engagement with this discourse has been limited to studying developmentalist policy ideas and their results.Footnote66 Similarly, political scientists have overwhelmingly focused on negative emotions and ignored the role that can be played by positive emotions, such as hope and enthusiasm.Footnote67 This article introduces developmentalism as a popular narrative, and it reveals the mediating role that positive emotions play in the formation of economic evaluations.

This study also opens new avenues for future research. One such area is the variation in the success of certain authoritarian narratives. Many leaders in the Global South attempt to use promises of fast economic development to build public support and legitimacy. Under what conditions do these promises evoke enthusiasm and hope among the population and build popular support for the regime? The previous credibility of the regime and the temporal order of economic developments can play important roles here. When Erdoğan made the developmentalist promise the centre of his electoral campaign in 2011, he could boast about years of fast economic growth under his leadership. When the economic decline started in the mid-2010s, his supporters had already developed affective investments in the NDN. While this temporal explanation seems plausible to me, we need more systematic comparisons to understand political and economic conditions facilitating the success of authoritarian narratives.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (2.1 MB)Acknowledgements

This article has benefitted from the feedback of many scholars. I want to thank Chris Claassen, Rhys Crilley, Wooseok Kim, Nazlı Konya, Rachael McLellan, Katerina Tertytchnaya, Lauren E. Young, participants of the APSA 2022 and PSA 2022 Annual Meeting panels at which this paper was presented, participants of the University of Glasgow Comparative Politics cluster meeting at which this paper was presented, anonymous reviewers and all other scholars who have provided feedback on various versions of this manuscript. I also want to thank KONDA Survey Company and Aydın Erdem for sharing the national face-to-face survey data. The origins of this article go back to Dr Yahya Madra's seminars at Bogazici University in 2013, but I am not sure if he will like the theoretical and methodological framework I built on his idea of “development fantasy.” I will always be grateful for his contributions to my academic development during that period.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aykut Öztürk

Aykut Öztürk is a lecturer (assistant professor) in the School of Social & Political Sciences at the University of Glasgow. His research focuses on democratic backsliding and authoritarianism, political identities and emotions, and online survey methods. Outputs of his previous research on these topics have been published in academic journals including Comparative Political Studies, Perspectives on Politics, and Government and Opposition.

Notes

1 Guriev and Treisman, “Informational autocrats.”

2 Aytaç, “Effectiveness of Incumbent’s Strategic Communication”; Mattingly and Yao, “How Soft Propaganda Persuades.”

3 More information on Turkey’s economic and democratic trajectory under Erdoğan’s rule can be found in Online Appendix Section 1.

4 Paget, “Again, making Tanzania great”; Sinha “Strong leaders, authoritarian populism”; Huda, “Autocratic power?”.

5 Greene and Robertson, “Affect and Autocracy”, 38.

6 See Hammack and Pilecki, “Narrative as a root metaphor”, 76; Kølvraa, “European Fantasies”, 171; Polletta et al., “The sociology of storytelling”; Skonieczny, “Emotions and political narratives”, 65.

7 Miskimmon et al., Strategic narratives, 5.

8 Compare to, for example, Brand, Official Stories; Sheafer et al., “Voting for our story”.

9 Herrera, “Imagined Economies”; Tomlinson Managing the Economy.

10 Kohli, State-directed development; Scott, Seeing like a state; Sikkink, Ideas and institutions.

11 Coronil, Magical State; Inden, “Embodying God”.

12 Kotkin, Magnetic Mountain; Weitz, A century of genocide.

13 Liu, “Maoist discourse.”

14 Ioris, Transforming Brazil.

15 Paget, “Again, making Tanzania great”.

16 Sinha “Strong leaders, authoritarian populism”.

17 Huda, “Autocratic power?”, 11.

18 Kotkin, Magnetic Mountain.

19 Paget, “Again, making Tanzania great;”

20 Cleary and Özturk, “When does backsliding lead to breakdown”; Öztürk and Reilly, “Assessing centralization”.

21 Levitsky and Way, Competitive authoritarianism; Luhrman et al.,; “Regimes of the world”.

22 A broader and comparative discussion on Turkey’s current political regime can be found in Online Appendix Section 1.

23 Aslan, “Public Tears”; Hintz and Banks, “Symbolic Amplification”; Soyaltin-Colella and Demiryol, “Unusual middle power activism”.

24 Aytaç, “Economic voting during the AKP”.

25 Ibid.

26 Yagci and Oyvat, “Partisanship, media and the objective economy”.

27 Yıldırım et al., “Dynamics of campaign reporting”.

28 A full list of election posters used in 2011 election campaign can be found in Online Appendix Section 2.

29 AKP, Election Manifesto.

30 These election posters can be found in Online Appendix Section 2.

31 Nefes, “The impacts of the Turkish government’s”.

32 Konda, Toplumun Gezi Parkı Olayları Algısı, 35.

33 Zengin and Ongur, “How sovereign is a populist”.

34 (Cosentino et al., “Post-truth politics”, 97.

35 Tuğal, “Politicized megaprojects”.

36 Presidency, “President Erdoğan Inaugurates Osmangazi”.

37 Brader and Marcus, “Emotion and political psychology”.

38 Solomon, “The affective underpinnings of soft power.”

39 Carver et al., “Origins and functions”; Lerner et al., “Emotion and decision making”.

40 Andrews-Lee, “The revival of charisma”; Antonakis et al., “Charisma: An ill-defined and ill-measured gift”; Bono and Ilies, “Charisma, positive emotions”.

41 McLaughlin et al., “React to the future”.

42 Andrews-Lee, “The revival of charisma”. It is important to remind that the first decade of Erdoğan’s rule in Turkey, between 2002 and 2011, was characterized with fast economic growth. It can be argued that this initial success story made Erdoğan credible enough, in the eyes of AKP voters, when he introduced his developmentalist promises in 2011.

43 Subotic and Zarakol, “Hierarchies, emotions, and memory”; Gursoy, “Emotions and narratives”.

44 Lewis-Beck and Paldam, “Economic voting”.

45 Anson, “That’s not how it works”.

46 Aytaç¸ “Relative economic performance”; Huang, “International knowledge and domestic evaluations”, Kayser and Peress, “Benchmarking across borders”.

47 For example, see Türkiye, “Almanlar bizi kıskanıyor”; Habertürk, “Almanlar Istanbul Havalimanı’nı neden”.

48 Marcus et al., Affective intelligence and political judgment.

49 Lerner et al., “Emotion and decision making”; Marcus et al., “Applying the theory of affective intelligence”.

50 Balta et al., “Populist attitudes and conspiratorial thinking”; Konda, “Populist Tutum, Negatif Kimliklenme.”

51 Steinberg, “How Voters Respond to Currency”.

52 MHP (Nationalist Action Party) has been a critical element of the ruling coalition since 2016. See Online Appendix Section 4.9 for more discussion on the inclusion of MHP voters among the ruling coalition voters.

53 What is the difference between ruling party voters who believe in the NDN and who do not? My preliminary analysis demonstrated that the belief in the NDN among the ruling coalition voters was correlated with right-wing ideology (r = 0.17), religiosity (r = 0.18), and watching pro-government media (r = 0.18).

54 Exemption from Institutional Review was received from Syracuse University on February 25, 2020.

55 See Neundorf & Öztürk, “How to improve representativeness” and Section 4.1 of the Online Appendix for more explanation of this method and our advertisement materials.

56 The registration plan is accessible at https://osf.io/hjekf. There were only two diversions from the registration plan: collecting a larger sample than initially planned and including MHP voters among the ruling coalition voters. These changes are discussed in more detail in Online Appendix Section 4.9.

57 Neundorf & Öztürk, “Advertising Online Surveys”; Neundorf & Öztürk, “How to improve representativeness”.

58 All of the nine pre-treatment variables were used for balance tests. Results have shown that, among The ruling coalition voters, respondents in the treatment group were more religious than respondents in the control group (p = 0.043). Among other voters, respondents in the treatment group had less political interest than respondents in the control group (p = 0.047). Following the pre-analysis plan, I added all nine pre-treatment variables to the models presented in this section as control variables. Results without control variables are presented in Online Appendix Section 4.7; there are no serious differences.

59 Shirikov, “Fake news for all.”

60 Sheafer et al., “Voting for our story”, 318

61 Zaller, The nature and origins.

62 Webster & Albertson, “Emotion and politics”.

63 Hasell and Weeks, Partisan provocation; Valentino and Neuner, “Why the sky didn’t fall”.

64 Stapleton and Dawkins, “Catching my anger”.

65 See Coronil, Magical State; Ioris, Transforming Brazil; Inden, “Embodying God”; Kotkin, Magnetic Mountain; Scott, Seeing like a state.

66 Kohli, State-directed development; Sikkink, Ideas and institutions.

67 Dornschneider, Hot contention, cool abstention; Greene and Robertson, “Affect and Autocracy”.

References

- AKP. Election Manifesto for 12 June 2011 General Election [In Turkish]. Available at www.akparti.org.tr/media/318778/12-haziran-2011-genel-secimleri-secim-beyannamesi-1.pdf, 2011.

- Andrews-Lee, Caitlin. “The Revival of Charisma: Experimental Evidence from Argentina and Venezuela.” Comparative Political Studies 52, no. 5 (2019): 687–719.

- Anson, Ian G. ““That’s not How it Works”: Economic Indicators and the Construction of Partisan Economic Narratives.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 27, no. 2 (2017): 213–234.

- Antonakis, John, Nicolas Bastardoz, Philippe Jacquart, and Boas Shamir. “Charisma: An ill-Defined and ill-Measured Gift.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 3 (2016): 293–319.

- Aslan, Senem. “Public Tears: Populism and the Politics of Emotion in AKP's Turkey.” International Journal of Middle East Studies 53, no. 1 (2021): 1–17.

- Aytaç, Selim Erdem. “Relative Economic Performance and the Incumbent Vote: A Reference Point Theory.” The Journal of Politics 80, no. 1 (2018): 16–29.

- Aytaç, Selim Erdem. “Economic voting during the AKP era in Turkey.” In The Oxford Handbook of Turkish Politics, edited by Murat Tezcur Gunes 319–340. New York (NY): Oxford University Press.

- Aytaç, Selim Erdem. “Effectiveness of Incumbent’s Strategic Communication During Economic Crisis Under Electoral Authoritarianism: Evidence from Turkey.” American Political Science Review 115, no. 4 (2021): 1517–1523.

- Balta, Evren, Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, and Alper H. Yagci. “Populist Attitudes and Conspiratorial Thinking.” Party Politics 28, no. 4 (2022): 625–637.

- Bono, Joyce E., and Remus Ilies. “Charisma, Positive Emotions and Mood Contagion.” The Leadership Quarterly 17, no. 4 (2006): 317–334.

- Brader, Ted, and George E Marcus. “Emotion and Political Psychology.” In Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, edited by Leonie Huddy, David Sears, and Jack S. Levy, 165–204. New York (NY): Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Brand, Laurie A. Official Stories: Politics and National Narratives in Egypt and Algeria. Stanford (CA): Stanford University Press, 2014.

- Carver, Charles S, Michael F Scheier, and Sheri L Johnson. “Origins and Functions of Positive Affect: A Goal Regulation Perspective.” In Positive Emotion: Integrating the Light Sides and Dark Sides, edited by June Gruber, and Judith Tedlie Moskowitz, 34–51. New York (NY): Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Chen, Dan. “Political Context and Citizen Information: Propaganda Effects in China.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 31, no. 3 (2019): 463–484.

- Cleary, Matthew R., and Aykut Öztürk. “When Does Backsliding Lead to Breakdown? Uncertainty and Opposition Strategies in Democracies at Risk.” Perspectives on Politics 20, no. 1 (2022): 205–221.

- Coronil, Fernando. The Magical State: Nature, Money, and Modernity in Venezuela. Chicago (IL): University of Chicago Press, 1997.

- Cosentino, Gabriele, and Berke Alikasifoglu. “Post-Truth Politics in the Middle East: The Case Studies of Syria and Turkey.” Artnodes 24 (2019): 91–100.

- Dornschneider, Stephanie. Hot Contention, Cool Abstention: Positive Emotions and Protest Behavior During the Arab Spring. New York (NY): Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Greene, Samuel A., and Graeme Robertson. “Affect and Autocracy: Emotions and Attitudes in Russia After Crimea.” Perspectives on Politics 20, no. 1 (2022): 38–52.

- Guriev, Sergei, and Daniel Treisman. “Informational Autocrats.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33, no. 4 (2019): 100–127.

- Gürsoy, Yaprak. “Emotions and Narratives of the Spirit of Gallipoli: Turkey’s Collective Identity and Status in International Relations.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies (2022): 1–19.

- Haberturk. “Almanlar Istanbul Havalimanı’nı neden kıskanıyor.” Haberturk Gazetesi URL https://www.haberturk.com/almanlar-istanbul-havalimani-ni-neden-kiska niyor-2199352-ekonomi. Accessed on 24 July 2023.

- Hammack, Phillip L., and Andrew Pilecki. “Narrative as a Root Metaphor for Political Psychology.” Political Psychology 33, no. 1 (2012): 75–103.

- Hasell, Ariel, and Brian E. Weeks. “Partisan Provocation: The Role of Partisan News use and Emotional Responses in Political Information Sharing in Social Media.” Human Communication Research 42, no. 4 (2016): 641–661.

- Herrera, Yoshiko M. “Imagined Economies.” In Constructing the International Economy, edited by Rawi Abdelal, Mark Blyth, Craig Parsons, 114–134. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press, 2011.

- Hintz, Lisel, and David E. Banks. “Symbolic Amplification and Suboptimal Weapons Procurement: Explaining Turkey’s S-400 Program.” Security Studies 31, no. 5 (2022): 826–856.

- Huang, Haifeng. “International Knowledge and Domestic Evaluations in a Changing Society: The Case of China.” American Political Science Review 109, no. 3 (2015): 613–634.

- Huda, Mirza Sadaqat. “Autocratic Power? Energy Megaprojects in the age of Democratic Backsliding.” Energy Research & Social Science 90 (2022): 102605.

- Inden, R. “Embodying God: From Imperial Progresses to National Progress in India.” Economy and Society 24-2 (1995): 245–278.

- Ioris, Rafael R. Transforming Brazil: A History of National Development in the Postwar Era. New York (NY): Routledge, 2014.

- Kayser, Mark Andreas, and Michael Peress. “Benchmarking Across Borders: Electoral Accountability and the Necessity of Comparison.” American Political Science Review 106, no. 3 (2012): 661–684.

- Kohli, Atul. State-Directed Development: Political Power and Industrialization in the Global Periphery. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge university press, 2004.

- Konda. Toplumun “Gezi Parkı Olayları” Algısı Gezi Parkındakiler Kimlerdi.: https://konda.com.tr/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/KONDA_GeziRaporu2014.pdf. 2014.

- Konda. Populist Tutum, Negatif Kimliklenme ve Komploculuk. https://konda. com.tr/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/TR1811_Barometre92_Populist_Tutum_ve_Ko mploculuk.pdf. 2018.

- Kotkin, Stephen. Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization. Berkeley (CA): University of California Press, 1997.

- Kølvraa, Christoffer. “European Fantasies: On the EU's Political Myths and the Affective Potential of Utopian Imaginaries for European Identity.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 54, no. 1 (2016): 169–184.

- Lerner, Jennifer S., Ye Li, Piercarlo Valdesolo, and Karim S. Kassam. “Emotion and Decision Making.” Annual Review of Psychology 66 (2015): 799–823.

- Levitsky, Steven, and Lucan A Way. Competitive Authoritarianism: Hybrid Regimes After the Cold War. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Lewis-Beck, Michael S., and Martin Paldam. “Economic Voting: An Introduction.” Electoral Studies 19, no. 2-3 (2000): 113–121.

- Liu, Yu. “Maoist Discourse and the Mobilization of Emotions in Revolutionary China.” Modern China 36, no. 3 (2010): 329–362.

- Lührmann, Anna, Marcus Tannenberg, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening new Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes.” Politics and Governance 6, no. 1 (2018): 60–77.

- Marcus, George E, W. Russell Neuman, and Michael MacKuen. Affective Intelligence and Political Judgment. Chicago (IL): University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- Marcus, George E., Nicholas A. Valentino, Pavlos Vasilopoulos, and Martial Foucault. “Applying the Theory of Affective Intelligence to Support for Authoritarian Policies and Parties.” Political Psychology 40 (2019): 109–139.

- Mattingly, Daniel C., and Elaine Yao. “How Soft Propaganda Persuades.” Comparative Political Studies 55, no. 9 (2022): 1569–1594.

- McLaughlin, Bryan, John A. Velez, Melissa R. Gotlieb, Bailey A. Thompson, and Amber Krause-McCord. “React to the Future: Political Visualization, Emotional Reactions and Political Behavior.” International Journal of Advertising 38, no. 5 (2019): 760–775.

- Miskimmon, Alister, Ben O’loughlin, and Laura Roselle. Strategic Narratives: Communication Power and the New World Order. New York (NY): Routledge, 2014.

- Nefes, Türkay Salim. “The Impacts of the Turkish Government’s Conspiratorial Framing of the Gezi Park Protests.” Social Movement Studies 16, no. 5 (2017): 610–622.

- Neundorf, Anja, and Aykut Öztürk. “Advertising Online Surveys on Social Media: How Your Advertisements Affect Your Samples.” OSF Preprints, 2022. https://osf.io/84h3t.

- Neundorf, Anja, and Aykut Öztürk. “How to Improve Representativeness and Cost-Effectiveness in Samples Recruited Through Meta: A Comparison of Advertisement Tools.” Plos one 18, no. 2 (2023): e0281243.

- Öztürk, Sevinç, and Thomas Reilly. “Assessing Centralization: On Turkey’s Rising Personalist Regime.” Southeast European and Black Sea Studies (2022): 1–19.

- Paget, Dan. “Again, Making Tanzania Great: Magufuli’s Restorationist Developmental Nationalism.” Democratization 27, no. 7 (2020): 1240–1260.

- Polletta, Francesca. “Pang Ching Bobby Chen, Beth Gharrity Gardner, and Alice Motes. “The sociology of storytelling.”.” Annual Review of Sociology 37 (2011): 109–130.

- Presidency, of Turkey. “President Erdoğan Inaugurates Osmangazi Bridge.” URL https://www.tccb.gov.tr/en/news/542/45570/president-Erdoğan-inaugurat es-osmangazi-bridge. 2016.

- Scott, James C. Seeing like a state. New Haven (CT): Yale University Press, 1999.

- Sheafer, Tamir, Shaul R. Shenhav, and Kenneth Goldstein. “Voting for our Story: A Narrative Model of Electoral Choice in Multiparty Systems.” Comparative Political Studies 44, no. 3 (2011): 313–338.

- Shirikov, Anton. Fake News for All: Misinformation and Polarization in Authoritarian Regimes. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3944011.

- Sikkink, Kathyrn. Ideas and Institutions: Developmentalism in Brazil and Argentina. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Press, 1991.

- Sinha, Subir. “‘Strong Leaders’, Authoritarian Populism and Indian Developmentalism: The Modi Moment in Historical Context.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 124 (2021): 320–333.

- Skonieczny, Amy. “Emotions and Political Narratives: Populism, Trump and Trade.” Politics and Governance 6, no. 4 (2018): 62–72.

- Solomon, Ty. “The Affective Underpinnings of Soft Power.” European Journal of International Relations 20, no. 3 (2014): 720–741.

- Soyaltin-Colella, Digdem, and Tolga Demiryol. “Unusual Middle Power Activism and Regime Survival: Turkey’s Drone Warfare and its Regime-Boosting Effects.” Third World Quarterly 44, no. 4 (2023): 724–743.

- Stapleton, Carey E., and Ryan Dawkins. “Catching my Anger: How Political Elites Create Angrier Citizens.” Political Research Quarterly 75, no. 3 (2022): 754–765.

- Steinberg, David A. “How Voters Respond to Currency Crises: Evidence from Turkey.” Comparative Political Studies 55, no. 8 (2022): 1332–1365.

- Subotić, Jelena, and Ayşe Zarakol. “Hierarchies, Emotions, and Memory in International Relations.” In The Power of Emotions in World Politics, edited by Simon Koschut, 100–112. New York (NY): Routledge, 2020.

- Tomlinson, Jim. Managing the Economy, Managing the People: Narratives of economic life in Britain from Beveridge to Brexit. New York (NY): Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Turkiye. “Almanlar bizi kıskanıyor: Türkler nasıl bu kadar hızlı.” Turkiye Gazetesi. URL: https://www.turkiyegazetesi.com.tr/dunya/549165.aspx 2018.

- Tuğal, Cihan. “Politicized Megaprojects and Public Sector Interventions: Mass Consent Under Neoliberal Statism.” Critical Sociology 49, no. 3 (2023): 457–473.

- Valentino, Nicholas A., and Fabian G. Neuner. “Why the Sky Didn't Fall: Mobilizing Anger in Reaction to Voter ID Laws.” Political Psychology 38, no. 2 (2017): 331–350.

- Webster, Steven W., and Bethany Albertson. “Emotion and Politics: Noncognitive Psychological Biases in Public Opinion.” Annual Review of Political Science 25 (2022): 401–418.

- Weitz, E. D. A Century of Genocide: Utopias of Race and Nation. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

- Yagci, Alper H., and Cem Oyvat. “Partisanship, Media and the Objective Economy: Sources of Individual-Level Economic Assessments.” Electoral Studies 66 (2020): 102135.

- Yıldırım, Kerem, Lemi Baruh, and Ali Çarkoğlu. “Dynamics of Campaign Reporting and Press-Party Parallelism: Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism and the Media System in Turkey.” Political Communication 38, no. 3 (2021): 326–349.

- Zaller, John R. The Nature and Origins of Mass Opinion. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Zengin, Huseyin, and Hakan Ovunc Ongur. “How Sovereign is a Populist? The Nexus Between Populism and Political Economy of the AKP.” Turkish Studies 21, no. 4 (2020): 578–595.