ABSTRACT

Authoritarian regimes frequently reach across borders to repress against exiled dissidents. Existing scholarship has investigated the methods and effects of transnational repression. Yet, we lack knowledge of the role that the political context of a host country and its relations to the origin country of diasporas play in incidents of transnational repression. Addressing this gap, we use a Freedom House dataset on physical acts of transnational repression (2014–2020) to study how the regime type of the host country and the regional ties between the host and origin country influence the likelihood and type of transnational repression incidents. Conducting a logistic regression analysis with yearly directed dyads, we find that to target exiles in autocratic host states perpetrators primarily rely on the cooperation of authorities, whereas in democratic host states they resort more often to direct attacks. We also show that authoritarian cooperation on transnational repression is regionally clustered: it often occurs when home and host state are situated within the same authoritarian neighbourhood, and partly also when they are members in the same regional organization. Our article reveals some of the host state conditions and relational dynamics that shape the decisions and strategies of transnational repression perpetrators.

Introduction

Authoritarian governments frequently use threats and violence against exiles and diaspora groups to silence and punish dissidents in other countries. For the purposes of transnational repression they rely on methods ranging from digital surveillance to kidnappings and murder.Footnote1 In response to global flows of information and migration, these regimes extend the reach of domestic political controls across borders “in ways that partially transcend both territorial jurisdiction and geographical distance.”Footnote2 Thereby, they show a dangerous disregard for human rights, state sovereignty, and other international norms.Footnote3 The Belarusian authorities’ forced landing of a commercial airplane to capture an exiled blogger, in May 2021, is a case in point.Footnote4 Existing studies have investigated the methods and motivations of authoritarian rulers engaging in transnational repression as well as the detrimental effects of their tactics on the personal security and fundamental rights of affected diasporas.Footnote5 However, research has yet to address how the political context of the country hosting the targeted exiles and its relations to the origin country influence the decisions and capabilities of authoritarian governments to rely on transnational repression. When going after exiles, the perpetrating governments may use embassies as outposts for launching spying operations, harassment, and physical assaults. Occasionally they even send secret squads to capture or kill their opponents in exile. More often, they seek the cooperation of host state authorities to get hold of dissidents, for instance with international arrest warrants or deportation and detention requests. Whether perpetrators of transnational repression engage in a direct attack or cooperate with authorities, the host country context and relations with the host government will determine their opportunities and deliberations on the use of coercive action across borders.

In this article, we study how the regime type of the host country and the regional ties between the host and origin country influence the likelihood and type of transnational repression incidents. Building on a database about physical acts of transnational repression compiled by Freedom House, we conduct a logistic regression analysis using yearly directed dyads for the period 2014 to 2020. Our study reveals some of the dynamics and conditions that shape the prospects and strategies for successful acts of physical transnational repression.

First, we show that the host state's level of democracy affects the method with which exiles are targeted: Whereas in other autocracies the perpetrators primarily work with the host state's institutions, in democracies they often resort to direct attacks. We explain this finding with the different behaviour of the host state authorities. In autocracies, perpetrators more easily get assistance from authorities, due to weak rule of law and a common disregard for human rights. Democratic host states, in turn, are more resistant to cooperation requests from authoritarian regimes that would facilitate the persecution of dissidents. As a result, when perpetrators decide to repress against exiles living in democracies that they perceive as threatening, they primarily resort to direct physical attacks. Behind such types of incidents are authoritarian governments that are determined, assertive and resourceful enough to engage in operations on the territory of another state, accepting the potential risks and costs of these attacks.

Second, we show that authoritarian cooperation on transnational repression often occurs among states within the same region as well as states that are members of the same regional organization. In these authoritarian neighbourhoods, state authorities are more likely to assist each other in the cross-border persecution of dissidents because of existing ties among security agencies, shared strategic interests of regime preservation, or common ideological ground. Such authoritarian clusters are not only a high-risk zone for dissidents in search of refuge from their repressive home state but also areas where authoritarian rule and practices are strengthened and reinforced across borders.

In the next section, we review some of the key tenets of scholarship on transnational repression. Then we theorize on potential host country influences on successful acts of transnational repression, before moving on to present our data and research design. Next, we present our findings and discuss their implications. We conclude with recommendations for future research.

Authoritarian reach across borders

Whether it is the brutal killing of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Saudi Arabia's Istanbul consulate or the attempted poisoning of former Russian military intelligence officer Sergei Skripal in Salisbury – drastic acts of extraterritorial violence committed by repressive regimes occasionally make the news. Transnational repression is not a new phenomenon as the 1940 murder of Leon Trotsky by Soviet agents in Mexico shows. Yet, it has become more widespread, and the variety of deployed methods is often underestimated. Revealing the global scope of transnational repression, an investigation by Freedom House, a Washington-based advocacy organization, shows that between 2014 and 2020, 31 origin states committed 608 cases of physical repression in 79 host countries.Footnote6 These incidents included acts of detention, assault, physical intimidation, unlawful deportation, rendition, or suspected assassination. Governments also rely on passport cancellations and international arrest warrants to trap and detain opponents abroad. The system of the International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol) is frequently abused for politically motivated extradition requests.Footnote7 In addition to these direct physical threats and constraints on mobility, digital technologies provide authoritarian rulers with powerful tools to extend surveillance and control beyond borders and deep into the personal life of exiles.Footnote8 Moreover, the “proxy punishment” of family members in the home country allows for coercing entire diaspora communities at low cost without regime agents even needing to leave their territory.Footnote9

Among the targets of transnational repression are exiled human rights defenders, journalists, and political opposition members but also former regime insiders, ethnic and religious minorities. They range from recent refugees and emigrants to second-generation diasporas. Thus, a key tenet of scholarship on state repression in domestic settings often also holds for incidents of transnational repression: governments repress in response to dissent they consider as a threat to their position in power.Footnote10 The perpetrators of transnational repression primarily target exiles and diaspora communities who either risk fomenting dissent and opposition inside their country of origin or have the potential to raise external pressure or shape the international environment in ways contravening regime interests.Footnote11 Recent research shows that the likelihood of transnational repression increases in parallel with escalating domestic repression because in these situations regimes perceive transnational diaspora ties and new exiles who are driven abroad by the crackdown with greater suspicion.Footnote12

Whereas threat perception is a key driver for the motivation to repress, however, a regime's reliance on repression is also affected by other factors unrelated to the interaction between the repressor and the targeted groups or individuals.Footnote13 When governments “choose from the repressive toolkit, they do not choose in a vacuum.”Footnote14 The decisions on whether to use repression at all and, if so, which methods are seen as a result of deliberations in which “political leaders carefully weigh the costs and benefits of coercive action.”Footnote15 Although repression is a key strategy of authoritarian rule, governments cannot rely on it permanently and exclusively lest they risk eroding a second important “pillar of stability”, namely their legitimation, both at home and abroad.Footnote16 Finally, in addition to threat perception and cost–benefit calculations, Shain lists another key variable determining the “likelihood of a regime using counter-exile measures”: the opportunities and capacities to engage in transnational repression.Footnote17 In transnational settings, repressive agents obviously find other opportunities and constraints than in the domestic context. Consequently, the host country environment and the relations to the host government play an important role for acts of transnational repression which, by definition, cross borders to interfere in the territory and jurisdiction of another state.

The manifestations of authoritarian coercion beyond the nation-state have long been ignored by both comparative politics scholarship and research on political repression. Studies into the international dimensions of authoritarian rule typically centre on the diffusion and promotion of repressive policies and corresponding legitimation strategies from one nation-state to another.Footnote18 The repression literature is still constrained by some of its widely used definitions, prioritizing a focus on repressive behaviour “within the territorial jurisdiction of the state.”Footnote19 Our knowledge about transnational repression comes from scholarship at the intersection of migration research, area studies, and international relations. It is based on qualitative research approaches using mainly interviews and case studies. However, recently compiled datasets on incidents of transnational repression allow for more systematic comparative research.Footnote20 In our article, we use one of these datasets to extend the current state of the field and investigate the potential influence of the host country regime type and the regional ties between the host and origin country on the probability of successful acts of physical transnational repression.

Theorizing host country influences

Host country regime type

Whether exiles reside in a democracy or autocracy will be a key factor shaping the threat perceptions, opportunities and cost–benefit calculations of transnational repression perpetrators. In authoritarian host countries, diasporas and exiles are more exposed to threats from their home regimes. The Freedom House data shows that, between 2014 and 2020, more than half (58%) of the documented acts of physical transnational repression were committed on the territory of another autocracy. In the following year, this figure still increased. Moreover, the researchers emphasize that “authoritarian governments are increasingly working together to help locate, threaten, detain, and expel their critics.”Footnote21 Going after exiles on the basis of cooperation with the authoritarian host state provides perpetrators of transnational repression with greater opportunities and benefits.

Due to a shared disregard for civil and political liberties, authoritarian governments are more likely to cooperate in the persecution of dissidents from other countries. Weak rule of law under these governments means that judicial authorities will not prevent politically motivated extradition requests or forced repatriations of dissidents. Instead of protecting exiles against threats from their home regime, law enforcement may readily collaborate with their counterparts from the authoritarian origin country to arrest and deport political exiles. International arrest warrants or agreements on mutual legal assistance between the two states allow to create a semblance of legal process before targets are forcibly returned to their origin country. As a consequence of back-door agreements, cooperation on transnational repression remains under the radar of media and civil society, causing less international attention and reputational costs for the perpetrating state. Finally, in authoritarian host countries, exiles can also fall prey to higher-ranking political interests and decisions of political convenience that bring the two states to exchange favours for the sake of improving strategic or economic relations. Turkey, for instance, was for a long time an important receiving country for Uyghurs seeking to escape repression in China's Xinjiang region. As the government of President Erdogan improved its relations with the Chinese government, however, it started deporting them.Footnote22

In more democratic host states, on the other hand, regimes engaging in transnational repression should find it more difficult to get host state authorities to cooperate. The rule of law and guarantee of fundamental rights inherent to democracies provide important bulwarks against attempts of authoritarian interference and cross-border repression. Also, the asylum regulations of Western democracies still establish a layer of protection for persecuted dissidents who are recognized as political refugees. One possible consequence is that authoritarian regimes resort to methods of “everyday repression,”Footnote23 such as surveillance and digital attacks, threats against home-country families and smear campaigns in state-aligned media.

However, there will still be cases when, because of increased threat perceptions, regimes choose to directly attack exiles despite potentially higher operational and reputational costs. The liberal environment of democracies provides diasporas from authoritarian countries with greater opportunities for voicing their demands and shoring up opposition to their home country regime. In particular, high-profile and outspoken political activists and journalists benefit from their “positionality” in Western democracies to build ties to influential media, advocacy organizations, and policy circles.Footnote24 They can act as information brokers, helping to publicize and frame demands of domestic opposition movements, raising awareness of rights violations, and leveraging public attention against the regime.Footnote25 Another important group of targets are former insiders who risk revealing sensitive information on a regime's inner workings to Western intelligence agencies or policy makers, thus harming the immediate security, economic or reputational interests of their home country government.Footnote26 To silence such types of challengers, regimes are more likely to resort to direct physical attacks when the manipulation or cooperation of democratic host state authorities appears impossible. The assassination attempts against former Russian military intelligence officer Sergei Skripal in the United Kingdom and prominent Azerbaijani blogger Mahammad Mirzali in France illustrate this point.Footnote27

In other cases, when a direct attack against exiles in more democratic host countries seems too costly or too difficult to implement, regimes can also try to lure their targets to locations within closer geographical proximity and under the rule of another authoritarian government – which are both important factors increasing the likelihood of successful transnational repression attacks, as outlined below.Footnote28

Based on the previous, we hypothesize that transnational repression (TR) incidents that involve the cooperation of host state authorities are more likely to take place in more authoritarian host states (H1). Because of the difficulty to get authorities in democratic countries to cooperate for the purposes of transnational repression, we expect direct attacks to primarily occur in more democratic host states (H2).

Authoritarian neighbourhoods

Although acts of transnational repression cross borders and distance, perpetrators will find greater opportunities and incentives for repressing against exiles in clusters of two or more neighbouring authoritarian countries. In particular, the practices of cooperation between authoritarian host and home states, which we describe above, are further amplified when both countries are situated within the same region.

Research on the international dimensions of authoritarian rule shows that authoritarian practices and regime persistence are reinforced by regional clusters. First of all, authoritarian neighbourhoods facilitate a diffusion of repressive practices as regimes learn from one another how to shield themselves against transnational advocacy and diaspora activism.Footnote29 Moreover, authoritarian regimes prefer to be surrounded by governments of similar regime type as they perceive the stability of their own rule to be interlinked with that of others in their neighbourhood.Footnote30 Especially regional authoritarian powers or “autocratic gravity centers” can influence their surroundings, either by setting an example that others emulate or by exporting “sets of autocratic ideas, rules or policy instruments.”Footnote31 This latter active authoritarian sponsorship is primarily pursued on the basis of self-interest, for instance, to cultivate and support strategic allies or to prevent contagion effects from popular resistance and uprisings against the ruler next door. But autocracy promotion can also be more ideology-driven, aiming to build legitimacy for authoritarian and region-specific forms of governance as a means to offset Western ideas and pressure for democratization and human rights.Footnote32

Therefore, the regional linkages of autocracies bring about not only better opportunities for engaging in transnational repression but also a greater willingness on the part of the host state to cooperate in attacks against exiles. Transnational repression between Russia and Central Asia, for instance, often builds on long-term contacts among the security agencies of these countries, making it easier for regime agents to chase opponents outside their jurisdiction.Footnote33 Authoritarian governments have also limited interest in hosting exiles who criticize neighbouring rulers and could act as transmitters of dangerous ideas. Prominent women's rights advocate Loujain Alhathloul, for instance, a Saudi national living in the United Arab Emirates, was surveilled by the UAE-based cybersecurity company Dark Matter before being captured by Abu Dhabi police and forcibly rendered to Saudi Arabia where she was put in prison.Footnote34 Finally, regimes will also feel less compelled to protect exiles persecuted by their neighbours when cooperation helps to advance their own interests. With the support of Turkish authorities, for instance, Iranian security agents kidnapped on Turkish territory a Swedish-Iranian political activist advocating for Arab minority rights in Iran. In an apparent return of favours, Iran handed over three Kurdish activists to Turkey.Footnote35

Authoritarian diffusion and cooperation within a region are institutionalized and further reinforced by regional organizations. These work as a “transmission belt and learning room”Footnote36 or as “opportunity structures”Footnote37 for the spreading of authoritarian practices. Regional organizations facilitate the distribution of resources, provide legitimacy to authoritarian sponsorship, support in the event of domestic discontent and protection against Western pressure on accountability and human rights. As such, they are “instrumental in stabilizing authoritarian rule.”Footnote38 The Freedom House research highlights two regional organizations with authoritarian membership as particularly relevant for cooperation on transnational repression: the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC).Footnote39 The SCO's security doctrine stipulates a fight against the “three evils” of religious extremism, terrorism, and separatism. These framings as well as the organization's joint security and intelligence structures have helped China, among others, to prosecute Uyghurs across borders.Footnote40 Security arrangements between GCC members include broadly formulated extradition agreements, preventing the protection of dissidents from one member country in another.Footnote41 But also membership in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is based on non-interference, strong bilateral security ties and informal elite-centred decision-making, all of which undermine accountability mechanisms and could pave the way for backdoor cooperation on transnational repression within the region.Footnote42

Based on these reflections, we hypothesize that acts of transnational repression involving cooperation between home and host state authorities are more likely to happen when host and origin state are members of GCC, SCO, or ASEAN (H3). The likelihood of such incidents also increases in regional authoritarian clusters (H4).

Research design

Our data on transnational repression comes from the Freedom House Transnational Repression DatabaseFootnote43 which contains incidents of physical transnational repression with information on the type of repression (assassination/assassination attempt, assault, unlawful deportation or detention, rendition, unexplained disappearance), as well as on the victim's origin country and the host state. FH relies on a variety of (public) sources for its database, including reports from international organizations, non-governmental organizations, legal documents, and journalistic accounts. Some reported incidents were further investigated by interviewing relevant actors.Footnote44 The database only documents a case if it is already in the public domain so as to not endanger any victim of transnational repression.Footnote45 Importantly, the database only includes incidents of physical transnational repression, not any non-physical types, such as online harassment, coercion by proxy or the use of spyware. This approach is in line with the overall research on state repression as “overt, coercive forms of repression are studied most often.”Footnote46 It is moreover possible that in spite of FH's rigorous methods, some transnational repression incidents remain under the radar, potentially causing an underreporting of incidents in the database. We reflect on some implications of this (potential) bias in the discussion of our results.

To estimate the probability of a transnational repression incident we use yearly directed dyads for the period 2014 to 2020 as our unit of analysis. The dyadic nature allows us to include information on the host and origin country, as well as on their relationship. Similar to the democratic peace theory literature, we only include politically relevant dyads where a reasonable possibility of a transnational repression incident exists.Footnote47 This means that, since transnational repression is almost exclusively carried out by authoritarian states, we use V-Dem's information on regime type to only include those dyads where the country of origin is either an “electoral autocracy” or a “closed autocracy.” The host state can be any type of regime. This results in a total of 103,935 directed dyads for our analysis (excluding any independent variables).

Dependent variable(s)

We split our dependent variable into two distinct types of transnational repression: cooperation incidents and direct attacks.

Cooperation incident is a dummy variable measuring whether in a particular (directed) dyad/year at least one TR incident occurred that required the cooperation of the host state's institutions, including both unlawful deportations, detentions, and renditions. Our dataset contains 182 cooperation incidents in a directed dyad/year, meaning the probability of a cooperation incident without any explanatory variables is p = 0.0018. Although FH distinguishes renditions from cooperation incidents, we include them in this category. While some renditions can take the form of kidnappings of the target person from the territory of the host country, in most cases they involve “working closely with host country authorities to illegally transfer people to the origin country.”Footnote48 counts for the period 2014–2020 the number of years that a directed dyad had at least one cooperation incident. Especially Russian citizens in Tajikistan and Chinese citizens in Thailand seem vulnerable to cooperative transnational repression: Out of the seven years included in the dataset, in six of them at least one cooperation incident occurred in these directed dyads.

Table 1. Years with at least one cooperation incident (2014–2020).

We run separate models for robustness that exclude renditions from cooperation incidents, and also run a separate model with our dependent variable operationalized as a count variable with the total number of cooperation incidents per directed dyad/year. Our dataset contains 510 cooperation incidents in total. shows the directed dyads/years with the highest total number of cooperation incidents. Especially the 121 incidents with Chinese citizens in Thailand in 2015 strikes out, as well as the Turkey-Saudi Arabia nexus with 21 incidents in 2017.

Table 2. Total number of cooperation incidents (2014–2020).

Direct attack is also a dummy variable and indicates whether at least one direct attack occurred in a (directed) dyad/year, including assassinations (or attempted murder)Footnote49, physical assaults, and unexplained disappearances. Our dataset contains 45 direct attacks in a directed dyad/year and a probability of a direct attack without any explanatory variables of p = 0.0004. shows for the period 2014–2020 the number of years that a directed dyad had at least one direct attack. With three years of at least one direct attack, the Thailand-Laos nexus tops this list.

Table 3. Years with at least one direct attack (2014–2020).

Also here we run a separate model using the total number of direct attacks per directed dyad/year as our dependent variable. This count variable contains 55 direct attacks in total. shows the directed dyads/years with the highest total number of direct attacks. With four direct attacks in 2017, the Vietnam–Cambodia nexus tops this list.

Table 4. Total number of direct attacks (2014–2020).

Independent variables

To test H1 and H2, we operationalize the level of democracy host state by using the V-DEM liberal democracy index.Footnote50 The variable runs from 0.006 (Eritrea) to 0.891 (Denmark). As an alternative operationalization for the level of democracy, we use Freedom House's tripartite distinction between non-free, partly free, and free countries.Footnote51 To test H3, we operationalize regional authoritarian clusters using V-DEM's 10 politico-geographic regions, including those regions with variation on our dependent variables: Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Latin America, MENA, Sub-Sahara Africa, Eastern Asia and South–Eastern Asia.Footnote52 We expect cooperation incidents to occur most often in those regions with the lowest average liberal democracy scores. In our dataset, these are the MENA region, South-East Asia, and Eastern-Europe and Central Asia. To test H4, we measure the participation in authoritarian organizations by making dummy variables GCC, SCO and ASEAN that score a 1 if both the host and origin country are members of that platform.

Control variables

We control for a set of factors that are likely to be correlated to both our independent and dependent variables. Firstly, the power relation between the host and origin state is likely to be important for the dynamics and conditions that shape the prospects and strategies for transnational repression. Powerful states have more leverage over weaker states to force them to cooperate and might have less to fear from repercussions after a direct attack. We operationalize the power advantage of the origin state by using the CINC index, containing annual values for total population, urban population (the demographic dimension), iron and steel production, energy consumption (the industrial dimension), and military personnel, and military expenditure (the military dimension).Footnote53 As the dataset runs until 2016, a linear interpolation was carried out for the years 2017–2020. To calculate the power advantage of the origin state, we deduct the host state's CINC score from the origin state's CINC score, and subsequently multiply by 100. The variable runs from -23 to 23, with China holding the largest power advantage over the Seychelles. We also attempt to capture the economic dimension of the power relationship by using the IMF's Direction of Trade Statistics to measure the host state's economic dependency vis-à-vis the origin state.Footnote54 This variable is calculated by dividing the total trade (the sum of the imports and exports) by the size of the host state's economy (as measured by the GDP, PPP) × 100.Footnote55 The variable runs from practically 0 to 71 (Liberia-China), with a mean of 0.29.

The regional dynamics of transnational repression are likely to be strongly influenced by migrant flows within regions. Neighbouring or proximate countries are often easier to reach for citizens leaving their origin state, resulting in larger migrant communities in proximate host states and more diaspora activism. In order to determine the importance of authoritarian regional cooperation on TR (H3 and H4), it is thus important to hold the migrant flows constant. Using UN data, we include a control variable measuring the migrant stock from the origin country in our models (/100,000).Footnote56 As the original dataset only contains data for 2015 and 2020, a linear interpolation was carried out to fill in the missing years. The variable runs from 0 to 38 (meaning 3.8 million Syrians residing in Turkey) and has a mean of 0.27.Footnote57 Because we argue that geographic and political ties within a given region matter for authoritarian cooperation, we want to ensure that our regional variables are not merely picking up the geographical proximity between host and origin countries. We therefore include geographical distance between the origin and host state as a control in our standard models, measured as the distance per mile (x1000) between the two capitals using the EUGene database.Footnote58 We run separate models excluding geographical distance as a robustness check.

Because many of our variables might be strongly correlated to one another, it is important to check for multicollinearity. Only the region South East Asia and the organization ASEAN turn out to be too strongly correlated to be included in one model;Footnote59 the other variables all have VIF scores below 1.5. We therefore run separate models including the platforms and the regions. To control for time autocorrelation, we have included t (time since the last incident), t^2 and t^3 in the regression.Footnote60 Alternative techniques to control for time autocorrelation, could lead to estimation problems (time dummies) or are relatively difficult to implement (splines). Since we work with a binary dependent variable with many “0”s and few “1”s, there is the risk that the probability of occurrence of the event will be underestimated. Therefore, as robustness checks, we carried out the correction for the occurrence of rare events,Footnote61 as well as a penalized maximum likelihood estimation.Footnote62 We include standard errors clustered by year (and by directed dyad as robustness check).

Results

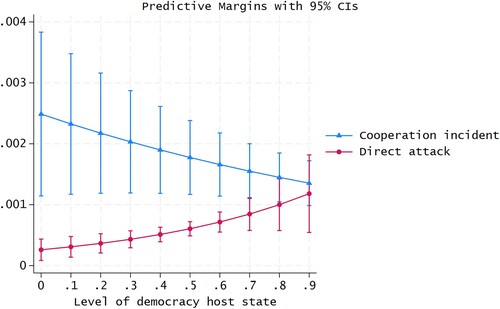

shows (in odds ratios) how the explanatory variables affect the probability of a cooperation incident (model 1) and a direct attack (model 4). Economic dependency of the host state (models 2 and 5) and migrants from the origin country (models 3 and 6) are added separately as the sample shrinks substantially due to missing values. Confirming H1 and H2,Footnote63 the probability of a cooperation incident increases in more authoritarian host states while the chance of a direct attack increases if the host state becomes more democratic. based on models 1 and 4 illustrates this: Whereas the likelihood of a cooperation incident in a dyad/year goes from p = 0.0025 in an (extremely) authoritarian state to p = 0.0014 in an (extremely) democratic host state, the probability of a direct attack shows the reverse pattern. Here, the probability is higher in an (extremely) democratic host state (p = 0.0012) than its (extremely) autocratic counterpart (p = 0.0003). Albeit the changes seem small, they are substantial in the light of the earlier mentioned probabilities when there are no covariates in our model. These findings are also very robust and hold when we run relogit and firthlogit models, when we use FH's dichotomous categorization of democracy, and when we cluster on the dyad id rather than year (see Appendix A1–4). When we exclude renditions from cooperation incidents, the level of democracy of the host state is no longer significant in model 1 (see A5), emphasizing the importance of renditions for authoritarian cooperation on TR.

Figure 1. Probability of a cooperation incident and a direct attack across different levels of democracy for the host state.

Table 5. Logistic regression models in odds ratios.

The finding that cooperation incidents occur more once the host states gets more authoritarian and direct attacks in more democratic host states is also highly robust when a count variable (measuring the total number of cooperation incidents and direct attacks per directed dyad/year) is used as the dependent variable. Table A6 in the Appendix shows that if the host state moves from extremely authoritarian to extremely democratic, the predicted number of cooperation incidents would be expected to decrease by a factor of 0.223 while the number of direct attacks would be expected to increase by a factor of 5.097.

The FH dataset also allows us to take a closer look at who is targeted in what hosting states, distinguishing target profiles in journalists, political activists, former regime insiders, human rights defenders, people who are targeted for their group identity, asylum seekers, and refugees.Footnote64 Importantly, these categories are not mutually exclusive, meaning that a victim of TR can for instance be both a political activist and an asylum seeker. provides information on the profiles of all TR targets across V-DEM's earlier introduced four different types of host states; Closed autocracies, electoral autocracies, electoral democracies, and liberal democracies. In addition to the absolute number of targets across regime type, the table reports in italics the column percentages that can be compared horizontally to learn who is targeted (more) in what type of host state. Confirming our arguments, political activists, journalists, and former regime insiders are more often a target of TR in liberal democracies than in any other regime type (higher percentages in italics). This corroborates the idea that the direct attacks in more democratic states are primarily used against diaspora members with “voice” who are considered a threat by the origin state. A chi-square test of independence also shows the relation between targets and regime type to be significant, X2 (18, N = 842) = 152.2, p = <0.01.

Table 6. Targets across different host states.

Looking at the origin states, we find that the majority of direct physical attacks against targets in democracies are committed by some of the key perpetrators of transnational repression at the global level: Russia (7 incidents), China (6), Iran (3), and Rwanda (2). These governments engage in broad campaigns of transnational repression using a wide range of methods. When they perceive an exile as a threat and cannot rely on the cooperation of host state authorities, they seem determined and resourceful enough to directly attack their opponents residing in democracies, even at the risk of political, economic or reputational consequences. China arguably “conducts the most sophisticated, global, and comprehensive campaign of transnational repression in the world.”Footnote65 Going after a variety of targets, including ethnic minorities, political dissidents, and former insiders, the Chinese government uses its international power and geopolitical weight to exert leverage on host states, bend international norms, and shield itself against accountability demands. Russia has made assassinations against former regime insiders and other perceived enemies of the state part of its larger programme of foreign interference and subversion that aims to aggressively assert its role in world politics. The Kremlin continues engaging in acts of physical transnational repression despite international condemnation, systematically denying any responsibility even in the most obvious cases such as the poisoning of former intelligence officer Alexander Litvinenko in 2006.Footnote66

As for Iran and Rwanda, both countries are not in a powerful political and economic position vis-à-vis Western host countries, but nevertheless determined enough to physically attack exiles residing in democracies. Under pressure from rising domestic discontent, the Iranian regime has even stepped up its efforts to go after the diaspora.Footnote67 Internationally isolated, the regime seems to see more benefit in silencing opponents abroad than being deterred by the repercussions of yet another act of transnational repression. The Rwandan government under President Paul Kagame depends on international donors and development cooperation, but has enjoyed remarkable impunity for its attacks against the diaspora. To fend off criticism, the Rwandan government successfully manipulates feelings of guilt in Western governments for their lack of intervention during the genocide of the Tutsi minority.Footnote68

Moving to H3, (model 1–3) also demonstrates the importance of the regional organizations for cooperation on TR, yet only for the SCO. If both countries are part of the SCO, the probability is p = 0.011 against p = 0.0018 if they are not. ASEAN is only significant at the 90% CI level in the first model, while the GCC is not significant at all. The GCC's non-significance might result from the fact that many incidents stay under the radar in this region. Freedom House claims that “it is quite possible that the scale of renditions and unlawful deportations between countries in the Gulf region […] is even larger.”Footnote69 An additional explanation for our finding regarding the GCC could be that the long-standing arrangements between governments in the region dissuade dissidents from resettling to neighbouring Gulf countries because they are already aware of the risks.

Membership of ASEAN turns out to have a surprising positive effect on the probability of a direct attack. If both countries are part of ASEAN, the probability of a direct attack is p = 0.0063 against p = 0.0008 if they are not. This finding is largely due to a sequence of direct attacks between Thailand and Laos that occurred in four subsequent years (2016–2019). In particular, five high-profile Thai dissidents exiled in Laos disappeared; some were later found killed. Although these incidents count as direct attacks in the database, the involvement and knowledge of Lao authorities remains unknown. Thailand repeatedly requested the assistance of Lao authorities in rendering exiles who defied the country's strict lèse-majesté laws by criticizing the monarchy. Lao military leadership also pledged to the Thai government that they would help track down Thai activists hiding out in Laos.Footnote70 In the case of a Lao human rights activist who disappeared in August 2019 in Bangkok, members of his network claim that he had been surveilled and put under pressure by authorities from both countries.Footnote71 In sum, even if the initial findings contradict our hypothesis on a higher probability of cooperation incidents among ASEAN members, the details of the cases suggest a different story. Although it is a relatively small cluster of incidents, transnational repression within ASEAN seems to work less along formal extradition treaties and security agreements than on the basis of informal understandings among fellow authoritarians within the same region. Obviously, state actors in authoritarian countries are never really transparent about their repressive practices and the extent of their cooperation.

To prevent multicollinearity issues, we run separate models in for H4 that include the politico-regional variables instead of the regional organizations. Both the MENA and Eastern-Europe/Central Asia turn out to be important regional political clusters for cooperation on transnational repression. If both the host and origin country are part of the MENA (p = 0.0037 against p = 0.0019) and Eastern Europe/Central Asia (p = 0.0059 against p = 0.0017), the probability of a cooperation incident is significantly higher. Once controlling for the migrants from the origin country (3rd model), the effect of MENA becomes insignificant. Looking deeper into cooperation incidents among MENA countries, it turns out that Egypt is responsible for 9 out of the 25 dyad/years with a cooperation incident, including 6 in Gulf states (Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and UAE) that host a large Egyptian diaspora (>400,000 Egyptians). This means that the regional clustering of (cooperative) transnational repression in the MENA seems to be at least partly driven by larger migrant flows among MENA countries.

Table 7. Logistic regression models in odds ratios (with politico-regional variables).

Contrary to our expectations, South-East Asia is not found to be an important regional authoritarian cluster for cooperative transnational repression. We have already highlighted possible dynamics of cooperation among states in the region even in incidents of direct attacks. An additional explanation comes from V-DEM's categorization of politico-geographic regions in which China is part of East-Asia and not of South-East Asia. However, in its global campaign of transnational repression, China intensively cooperates with South-East Asian governments. In our data, in 9 out of 22 dyad/years that China cooperated with another country to target a Chinese citizen it was with a South-East Asian government. As an important travel and migration hub, Thailand is particularly exposed to Beijing's reach: for six of the seven years included in the database, there is at least one incident of physical repression.

Despite low average democracy levels Sub-Saharan Africa turns out to have a negative effect on the probability of TR.Footnote72 A closer look at the data reveals that although most states in Sub-Saharan Africa indeed refrain from conducting TR, the states that do target exiles across borders (Sudan, South-Sudan, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Burundi, and Equatorial Guinea) still primarily cooperate with other African governments when doing so. Out of the 20 dyad/years that a Sub-Saharan African state conducted any sort of TR, 13 were cooperation incidents with other Sub-Saharan African governments.

Also the findings on regional organizations and regional authoritarian clusters are highly robust: When we run relogit or firthlogit models, as well as when we cluster on the dyad id rather than year (see Appendix A2–9) the findings hold, with South-East Asia here also becoming significant and positive despite the exclusion of China. When we exclude renditions from cooperation incidents (A10), the MENA variable loses some of its strength and significance, yet remains significant at a 90% confidence level (see A10). Our findings are also highly robust when a count variable is used as our dependent variable. Table A6 and A11 in the Appendix show that the predicted number of cooperation incidents would be expected to increase by a factor of 3.577 if both countries are part of the MENA, by a factor of 4.356 if both countries are part of Eastern Europe/Central Asia, and by 19.716 if both countries are members of the SCO.

Finally, when we run models excluding geographical distance as a control variable (Appendix A12 and A13) the strength and significance of the regional variables strongly increase. Compared to model 1 in , the probability of a cooperation incident among MENA states now jumps from p = 0.0037 to p = 0.0139 and for Eastern European/Central Asian states from p = 0.0059–0.0228. South-East Asia (p = 0.0204 against p = 0.0019) and East Asia (p = 0.0209 against p = 0.0020) now also become significant at the 99% CI level. Controlling for economic dependency and migrant flows decreases the strength of all regional effects, while East- and South-East Asia also lose some significance. All three regional organizations also become significant when geographical distance is excluded: As A13 in the Appendix shows, ASEAN (p = 0.0156 against 0.0019), SCO (p = 0.0375 against p = 0.0018) and GCC (p = 0.01511 against p = 0.020) are now all significant and positive at the 99% CI level. Relating these results back to and , we can conclude that the close geographic ties between authoritarian regimes within the same region and that are part of the same regional organization are an important, but for the SCO, the MENA and Eastern-Europe/Central Asia not the only explanation for why they cooperate more on transnational repression.

Discussion and conclusion

In their hunt for political exiles and the suppression of dissent across borders, authoritarian rulers’ decisions and opportunities are shaped by the international environment. In this article, we systematically investigated how the regime type of the host country and the regional ties between the host and origin country influence the probability and type of successful acts of physical transnational repression.

Our findings show that, first, the host country's regime type affects the type of transnational repression that is used: Whereas authoritarian host states mostly cooperate with perpetrating governments, resulting in deportations, detentions, and renditions, in democracies, where cooperation from state authorities is limited, perpetrators more often resort to direct assassinations and assaults. Our analysis of the profiles of targeted exiles reveals that these direct attacks in democracies are primarily directed against individuals who have the knowledge, position, and “voice” to challenge the legitimacy and stability of their home country regime, both in the domestic and international arena (political activists, journalists, former regime insiders). Second, our findings show the relevance of authoritarian regional clusters for incidents of transnational repression that involve cooperation among the home and host state. With regards to regional organizations acting as facilitators of cooperation on transnational repression, we find a greater probability of incidents if both host and origin state are members of the SCO, confirming the organization's role as a platform for authoritarian diffusion and consolidation. Qualifying our non-findings on the influence of ASEAN and the GCC, we explain how these two other regional organizations with predominantly authoritarian membership might still play a role in the practice of transnational repression, creating an unsafe environment for dissidents migrating from one member state to another.

Beyond formal membership in regional organizations, we show that the geographical and political ties of authoritarian countries within a given region amplify the dynamics of mutual support and cooperation between host and origin state in the repression of dissent across borders. We have pointed out some of the mechanisms that could be at the bottom of such regional clustering of cooperation on transnational repression: a strategic interest to be surrounded by governments of a similar regime type, the leverage exerted by an authoritarian regional power, a shared disregard for human rights activism and adherence to illiberal ideas, or simply a pragmatic quid pro quo between host and home state authorities. The most cooperative host states sit firmly within regions dominated by authoritarian rule or have even ties to more than one authoritarian neighbourhood. Authorities in Thailand and Russia have cooperated on transnational repression with five different origin countries during 2014–2020, for Turkey (6) and the UAE (7) this number is even higher.

Our approach to studying patterns of transnational repression also has some limitations. The first results from a likely underreporting of transnational repression incidents in authoritarian host countries. As explained in our research design, the Freedom House database relies on public sources. Perpetrators of transnational repression as well as their cooperation partners have strategic incentives to act in secrecy to forestall criticism and accountability demands from domestic and international actors. The freedom of media and civil society organizations who could document transnational repression is also restricted in these contexts. As a consequence, a number of incidents in authoritarian host countries likely stays under the radar of public attention and is not captured by the database.

Second, the dyadic approach using nation states as units of analysis for the home and host country of targeted exiles cannot properly account for the role of transit locations and travel hubs in incidents of transnational repression. Dissidents from authoritarian countries are particularly exposed to the long arm of their home regimes during times of travel or before reaching their final destination of exile. A Tajik opposition member residing in the Netherlands, for instance, was seized by regime authorities during a business trip to Moscow.Footnote73 A Saudi royal fallen out of favour with the government who lived in France was intercepted at an airport in Morocco and rendered to Saudi Arabia.Footnote74 The half-brother of North Korean leader Kim Jong-Un was assassinated at Kuala Lumpur Airport.Footnote75 These examples highlight the role of locations which are easily accessible both for the exiles and the agents of the perpetrating states who then seize such opportunities to attack. At times, they even try to lure their targets to such places. Cities and airports at the crossroads of travel routes and migration flows represent important nodes in the socio-spatial networks or “transnational fields” that tie exiles to their home country and transcend the boundaries of nation-states.Footnote76 The particular risks of such locations and stages of transit need to be further explored by research using alternative methodological approaches.

By identifying some of the conditions and relational dynamics that facilitate acts of transnational repression, our article contributes to three different sets of literature. First, for scholarship on transnational repression, we confirm the prevalence of cooperation in cases that involve authoritarian home and host countries, especially when both are situated within authoritarian regional clusters. We also highlight the increased risk of direct physical attacks against exiles in democratic host countries and provide possible explanations for the behaviour of the determined perpetrators behind such threats. Second, for research into the “third wave of autocratization”Footnote77 our article provides new insights into the role that transnational repression plays for the persistence of authoritarianism. We show that in regional clusters regimes not only learn from and mutually support each other to repress dissent and stabilize their domestic rule. They also collaborate in the control of their populations on other territories, reinforcing the outreach and impact of authoritarian practices across borders and within their larger neighbourhood. Finally, with regards to the literature on migration and diaspora activism, we highlight some of the locations and activities that increase the probability of transnational repression incidents and expose exiles and diaspora communities to threats from their home regimes.

In addition to academic research, our results also have implications for policy making that aims to counter transnational repression. First, our findings on the higher likelihood of direct attacks in democracies should serve as a warning that the costs for perpetrators are still not high enough to deter them from physically attacking their nationals on the territory of a democratic state. To overcome difficulties of cooperation with democratic host state authorities, perpetrators are even finding alternatives. China, for instance, has set up parallel police stations across countries in Europe, North and Latin America, and Asia.Footnote78 Both China and Iran have used private detectives to spy on dissidents in the United States.Footnote79 Iran has also hired members of a criminal organization to assassinate a high-profile women's rights defender living in New York.Footnote80 Second, the findings on authoritarian collaboration in regional clusters highlight the crucial importance of effective asylum and resettlement procedures providing protection against political persecution. The increasingly harsh migration regimes and measures of border externalization of democracies in the Global North push political emigrants farther away from the territory of liberal host states which they would need to reach as a precondition for securing refuge and protection. As a result, exiles remain trapped in third countries within authoritarian neighbourhoods, often at closer reach of their repressive home state.

With these contributions, our article paves the way for further research into the tactics and effects of globalized authoritarianism. First, the influence of some of our control variables (migrant ties, economic dependency, power relations) on the threat perceptions, opportunities and cost–benefit calculations of transnational repression perpetrators merits more attention. Second, the differences between direct attacks and cooperation incidents highlight the agency of host governments as a focus area that needs more research in order to explain the success or failure of specific transnational repression strategies. How are host governments responding to transnational repression against diasporas on their territory? How are their policies constraining or facilitating acts of transnational repression? There clearly is a need for studies investigating the host government actors, institutions and policies addressing, affected by, or possibly implicated in authoritarian repression across borders. Finally, it is important to understand how relevant the factors which we have identified are for other, non-physical types of transnational repression. Methods such as targeted surveillance or coercion by proxy do not require regime agents to enter the territory of the host state or gain the cooperation of its authorities, altering the cost–benefit calculations of perpetrators. How are the use of spyware and threats against home country families influenced by the regime type of the host country or the regional relations between home and host country? As these more subtle, but nonetheless impactful, methods of transnational repression often prepare, or go hand in hand with, an escalation to physical threats, it is important to discern patterns in their workings. Only by gaining a deeper understanding of the conditions and practices that facilitate transnational repression can we devise appropriate countermeasures to the global reach of assertive authoritarian regimes.

appendix.docx

Download MS Word (76.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the anonymous reviewers, whose constructive comments played a pivotal role in enhancing the quality of this paper. Special thanks are owed to Ursula Daxecker and Philipp M. Lutscher for their invaluable feedback. Johannes von Engelhardt deserves appreciation for his guidance in data analysis. Additionally, the authors acknowledge and thank Nate Schenkkan and Yana Gorokhovskaia for generously sharing the Freedom House dataset on transnational repression and for their constructive input on earlier drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marcus Michaelsen

Marcus Michaelsen, PhD, is a researcher studying digital technologies, human rights activism and authoritarian politics. He currently works as a Senior Researcher at the Citizen Lab focusing on digital transnational repression. Previously he was a Marie-Skłodowska-Curie Fellow in the Law, Science, Technology and Society (LSTS) research group of Vrije Universiteit Brussel and a Senior Information Controls Fellow with the Open Technology Fund. From 2014 until 2018 he was a post-doctoral researcher in the project Authoritarianism in a Global Age at the University of Amsterdam. His work on transnational repression has been published in Globalizations, Global Networks, the European Journal of International Security, and Surveillance & Society.

Kris Ruijgrok

Kris Ruijgrok, PhD in political science, studies the information and communication environments that shape, and are shaped by, authoritarian politics. He currently works as a postdoctoral researcher at the KITLV in Leiden on a project investigating online influence operations in South-East Asia. Previously he was an Information Controls Fellow with the Open Technology Fund conducting research on internet shutdowns in India. His PhD research (2014-2018) was part of the ERC funded “Authoritarianism in a Global Age” project at the University of Amsterdam and studied the effect of internet use on anti-government protest under authoritarian regimes, including in-depth fieldwork in Malaysia. The book based on his PhD dissertation was published with Palgrave Macmillan, while articles from his hand appeared in Contemporary Politics and Democratization.

Notes

1 Glasius, “Extraterritorial Authoritarian Practices”; Michaelsen, “Exit and Voice”; Moss, “Transnational Repression”; Schenkkan and Linzer, “Out of Sight”; Tsourapas, “Global Autocracies.”

2 Dalmasso et al., “Intervention,” 95.

3 Anstis and Barnett, “Digital Transnational Repression”; Cooley, “Authoritarianism”; Milanovic, “Murder of Jamal Khashoggi”; Michaelsen, “Exit and Voice.”

4 Eccles and Sheftalovich, “Inside the Control Room.”

5 Dukalskis, Making the World Safe; Furstenberg, Lemon, and Heathershaw, “Spatialising State Practices”; Lemon, Jardine and Hall, “Globalizing Minority Persecution”; Lewis, “Illiberal Spaces.”

6 Schenkkan and Linzer, “Out of Sight.”

7 Lemon, “Weaponizing Interpol.”

8 Al-Jizawi et al., “Psychological and Emotional War”; Michaelsen, “Silencing Across Borders”; Moss, “The Ties That Bind”.

9 Moss, Michaelsen and Kennedy, “Going after the family.”

10 deMeritt, “Strategic Use.”

11 Dukalskis, Making the World Safe.

12 Dukalskis et al., “Long Arm.”

13 Chenoweth, Perkoski, and Kang, “State Repression,” 1952.

14 deMeritt, “Strategic Use,” 6.

15 Davenport, “State Repression,” 4.

16 Gerschewski, “Three Pillars”; See also: Josua and Edel, “Regime Survival Strategies.”

17 Shain, The Frontier of Loyalty, 161.

18 Bank and Edel, “Authoritarian Regime Learning”; Bank, “Authoritarian Diffusion”; Tansey, International Politics.

19 Davenport, “State Repression and Political Order,” 1. See also: Cingranelli, Political Terror Scale.

20 Dukalskis et al., “Transnational Repression.”

21 Gorokhovskaia and Linzer, “Long Arm.”

22 Gorokhovskaia and Linzer, “Turkey.”

23 Schenkkan et al., “Perspectives.”

24 Koinova, “Beyond Statist Paradigms.”

25 Moss, “Voice After Exit.”

26 Dukalskis et al., “Long Arm,” 7.

27 Schwirtz and Barry, “A Spy Story”; Committee to Protect Journalists, “Exiled Azerbaijani Blogger.”

28 Consider the example of Ruhollah Zam, an exiled Iranian journalist, who fell for a trap set by Iran's Revolutionary Guard and travelled to Iraq from where he was rendered to Tehran and later executed. Peltier and Fassihi, “Iran Executes Dissident.”

29 Heydemann and Leenders, “Authoritarian Learning”; Koesel and Bunce, “Diffusion-Proofing.”

30 Bader, Grävingholt, and Kästner, “Would Autocracies Promote Autocracy?”

31 Kneuer et al., “Playing the Regional Card,” 3.

32 Ibid., 9; Tansey, International Politics; Schmotz and Tansey, “Regional Autocratic Linkage.”

33 Cooley and Heathershaw, Dictators Without Borders; Furstenberg, Lemon, and Heathershaw, “Spatialising State Practices”; Lewis, “Illiberal Spaces.”

34 Electronic Frontier Foundation, “AlHathloul v. DarkMatter.”

35 Msalmi, “Ahvazi Swedish Leader.”

36 Kneuer et al., “Playing the Regional Card.”

37 Debre, “Dark Side.”

38 Libman and Obydenkova, “Understanding Authoritarian Regionalism,” 153.

39 Schenkkan and Linzer, “Out of Sight,” 7.

40 Debre, “Dark Side,” 404.

41 Schenkkan and Linzer, “Out of Sight,” 33.

42 Acharya, “Democratisation.” By including ASEAN, we aim to extend the focus of Freedom House on the SCO and GCC and further qualify their arguments on these regional organizations as platforms for cooperation on transnational repression. However, we exclude other regional organizations with significant authoritarian membership such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) or the Bolivarian Alliance for the People of Our America (ALBA) because the number of transnational repression incidents involving their members is insignificantly low in the dataset. The Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) counts some persistent perpetrators of transnational repression among its members, but the organization's focus is primarily on economy and trade and its members largely overlap with the SCO which is more security-oriented.

43 See note 6 above.

44 See note 20 above.

45 Ibid.

46 Earl, “Political Repression,” 265.

47 Lemke and Reed, “Politically Relevant Dyads.”

48 Schenkkan and Linzer, “Out of Sight,” 2.

49 Attempted murder means attacks with the obvious intention to murder the targeted individual which ultimately failed or a murder plot that was foiled by the host country authorities

50 Coppedge, “V-Dem Dataset 2021.”

51 Gorokhovskaia, Shahbaz, en Slipowitz, “Freedom in the World 2023.”

52 Due to missing variation on our dependent variable (i.e. no TR incidents) for Western Europe and North America, South Asia, The Pacific and The Caribbean, these regions are excluded from our tables.

53 Singer, Bremer, and Stuckley, “Capability Distribution.”

54 International Monetary Fund, “Direction of Trade.”

55 Oneal and Russet, “Classical Liberals.”

56 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “International Migrant Stock.”

57 Here too, because of the interpolation, some scores are just below 0 for some years.

58 Bennett and Stam, “Research Design.”

59 VIF score above 12.

60 Carter and Signorino, “Back to the Future.”

61 Tomz, King, and Zeng, “Logistic Regression.”

62 Firth, “Bias Reduction.”

63 Except for model 6, which can be due to a reduced sample.

64 Freedom House Dataset 2021. The activity is not necessarily the main occupation of the individual in question. Asylum seeker refers to a person who has applied for but not yet been granted asylum in the host country; a refugee is someone who has been granted asylum in the host country. A former insider is someone who was part of the elite in the origin country but fell out with authorities. This can include former government officials, major financial or business figures and high-ranking defectors. A political activist is a person engaging in political activity relevant to the origin country, typically of an oppositional nature. Journalists can also include individuals publishing content on social media for a substantial audience, in contexts where traditional media are restricted. A human rights defender engages in the defence of and advocacy on behalf of the rights of a targeted individual or community.

65 Schenkkan and Linzer, “Out of Sight,” 15.

66 Blake, From Russia with Blood.

67 Harris, Mekhennet, and Torbati, “Iranian Assassination.”

68 Wrong, Do Not Disturb.

69 Schenkkan and Linzer, “Out of Sight,” 51.

70 Ellis-Petersen, “Murder on the Mekong.”

71 Lamb, “Thai Government.”

72 The same applies to South Asia which is not even included in the model due to a lack of variation in the dependent variables (i.e. no transnational repression incidents).

73 Eurasianet, “Tajikistan.”

74 Mohyeldin, “No One Is Safe.”

75 Ellis-Petersen and Haas, “How North Korea Got Away.”

76 Levitt and Schiller, “Conceptualizing Simultaneity.”

77 Lührmann and Lindberg, “Third Wave”; Hellmeier et al., “State of the World.”

78 Safeguard Defenders, “101 Overseas.”

79 Weiser and Rashbaum, “Iran and China.”

80 Weiser and Thrush, “Justice Department.”

Bibliography

- Acharya, Amitav. “Democratisation and the Prospects for Participatory Regionalism in Southeast Asia.” Third World Quarterly 24, no. 2 (2003): 375–390. doi:10.1080/0143659032000074646.

- Al-Jizawi, Noura, Siena Anstis, Sophie Barnett, Sharly Chan, Niamh Leonard, Adam Senft, and Ron Deibert. “Psychological and Emotional War: Digital Transnational Repression in Canada.” University of Toronto. 1 March 2022. https://citizenlab.ca/2022/03/psychological-emotional-war-digital-transnational-repression-canada/.

- Anstis, Siena, and Sophie Barnett. “‘Digital Transnational Repression and Host States’ Obligation to Protect Against Human Rights Abuses’.” Journal of Human Rights Practice 14, no. 2 (1 July 2022): 698–725. doi:10.1093/jhuman/huab051.

- Bader, Julia, Jörn Grävingholt, and Antje Kästner. “Would Autocracies Promote Autocracy? A Political Economy Perspective on Regime-Type Export in Regional Neighbourhoods.” Contemporary Politics 16, no. 1 (2010): 81–100. doi:10.1080/13569771003593904.

- Bank, André, and Mirjam Edel. “Authoritarian Regime Learning: Comparative Insights from the Arab Uprisings.” Hamburg: GIGA Institute, 2015. https://www.giga-hamburg.de/de/publikationen/giga-working-papers/authoritarian-regime-learning-comparative-insights-from-the-arab-uprisings.

- Bank, André. “The Study of Authoritarian Diffusion and Cooperation: Comparative Lessons on Interests Versus Ideology,: Nowadays and in History.” Democratization 24, no. 7 (2017): 1345–1357. doi:10.1080/13510347.2017.1312349.

- Bennett, D. Scott, and Allan C. Stam. “Research Design and Estimator Choices in the Analysis of Interstate Dyads: When Decisions Matter.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 44, no. 5 (October 2000): 653–685. doi:10.1177/0022002700044005005.

- Blake, Heidi. From Russia with Blood. The Kremlin’s Ruthless Assassination Program and Vladimir Putin’s War on the West. Hachette, UK: Mulholland Books, 2019.

- Carter, David B., and Curtis S. Signorino. “Back to the Future: Modeling Time Dependence in Binary Data.” Political Analysis 18, no. 3 (2010): 271–292. doi:10.1093/pan/mpq013.

- Chenoweth, Erica, Evan Perkoski, and Sooyeon Kang. “State Repression and Nonviolent Resistance.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 61, no. 9 (2017): 1950–1969. doi:10.1177/0022002717721390.

- Cheresheva, Mariya. “Bulgarians Outraged at Deportation of Gulen Supporter to Turkey.” Balkan Insight, 16 August 2016. https://balkaninsight.com/2016/08/16/bulgarians-outraged-at-deportation-of-a-gulen-supporter-to-turkey-08-15-2016/.

- Committee to Protect Journalists. “Exiled Azerbaijani Blogger Mahammad Mirzali Stabbed at Least 16 Times in Knife Attack in France.” 16 March 2021. https://cpj.org/2021/03/exiled-azerbaijani-blogger-mahammad-mirzali-stabbed-at-least-16-times-in-knife-attack-in-france/.

- Cooley, Alexander A., and John Heathershaw. Dictators Without Borders: Power and Money in Central Asia. Dictators Without Borders. Yale University Press, 2017.

- Cooley, Alexander. “Authoritarianism Goes Global: Countering Democratic Norms.” Journal of Democracy 26, no. 3 (2015): 49–63. doi:10.1353/jod.2015.0049.

- Coppedge, Michael. “V-Dem Dataset 2021.” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, 2021. https://doi.org/10.23696/VDEMDS21.

- Dalmasso, Emanuela, Adele Del Sordi, Marlies Glasius, Nicole Hirt, Marcus Michaelsen, Abdulkader S. Mohammad, and Dana Moss. “Intervention: Extraterritorial Authoritarian Power.” Political Geography 64 (2018): 95–104. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.07.003.

- Davenport, Christian. “State Repression and Political Order.” Annual Review of Political Science 10, no. 1 (2007): 1–23. doi:10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.101405.143216.

- Debre, Maria J. “The Dark Side of Regionalism: How Regional Organizations Help Authoritarian Regimes to Boost Survival.” Democratization 28, no. 2 (2021): 394–413. doi:10.1080/13510347.2020.1823970.

- deMeritt, Jacqueline H. R. “The Strategic Use of State Repression and Political Violence.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.32.

- Dukalskis, Alexander, Saipira Furstenberg, Sebastian Hellmeier, and Redmond Scales. “The Long Arm and the Iron Fist: Authoritarian Crackdowns and Transnational Repression.” Journal of Conflict Resolution: 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220027231188896.

- Dukalskis, Alexander, Saipira Furstenberg, Yana Gorokhovskaia, John Heathershaw, Edward Lemon, and Nate Schenkkan. “Transnational Repression: Data Advances, Comparisons, and Challenges.” Political Research Exchange 4, no. 1 (2022): 2104651. doi:10.1080/2474736X.2022.2104651.

- Dukalskis, Alexander. Making the World Safe for Dictatorship. Oxford University Press, 2021.

- Earl, Jennifer. “Political Repression: Iron Fists,: Velvet Gloves, and Diffuse Control.” Annual Review of Sociology 37, no. 1 (2011): 261–284. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102609.

- Eccles, Mari, and Zoya Sheftalovich. “Inside the Control Room of Belarus’ Hijacked Ryanair Flight.” POLITICO, 25 October 2022. https://www.politico.eu/article/belarus-hijack-minsk-ryanair-athens-to-vilnius-control-room/.

- Electronic Frontier Foundation. “AlHathloul v. DarkMatter Group - First Amended Complaint.” May 8, 2023, https://www.eff.org/files/2023/05/09/54.pdf.

- Ellis-Petersen, Hannah, and Benjamin Haas. “How North Korea Got Away with the Assassination of Kim Jong-Nam.” The Guardian. April 1, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/apr/01/how-north-korea-got-away-with-the-assassination-of-kim-jong-nam.

- Ellis-Petersen, Hannah. “Murder on the Mekong: Why Exiled Thai Dissidents Are Abducted and Killed.” The Observer, March 17, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/mar/17/thailand-dissidents-murder-mekong-election.

- Eurasianet. “Tajikistan: The Mysterious Case of the Would-Be Repentant Dissident.” 18 February 2019. https://eurasianet.org/tajikistan-the-mysterious-case-of-the-would-be-repentant-dissident.

- Firth, David. “Bias Reduction of Maximum Likelihood Estimates.” Biometrika 80, no. 1 (1993): 27–38. doi:10.1093/biomet/80.1.27.

- Freedom House. “Ukraine: Azerbaijani Activist Deported on Politically Motivated Grounds.” 15 December 2019. https://freedomhouse.org/article/ukraine-azerbaijani-activist-deported-politically-motivated-grounds.

- Furstenberg, Saipira, Edward Lemon, and John Heathershaw. “Spatialising state practices through transnational repression.” European Journal of International Security 6, no. 3 (2021): 358–378.

- Gerschewski, Johannes. “The Three Pillars of Stability: Legitimation,: Repression, and Co-Optation in Autocratic Regimes.” Democratization 20, no. 1 (2013): 13–38. doi:10.1080/13510347.2013.738860.

- Glasius, Marlies. “Extraterritorial Authoritarian Practices: A Framework.” Globalizations 15, no. 2 (2018): 179–197. doi:10.1080/14747731.2017.1403781.

- Gorokhovskaia, Yana, Adrian Shahbaz, and Amy Slipowitz. “Freedom in the World 2023: Marking 50 Years in the Struggle for Democracy.” Washington, DC, March 2023. https://freedomhouse.org/sites/default/files/2023-03/FIW_World_2023_DigtalPDF.pdf.

- Gorokhovskaia, Yana, and Isabel Linzer. “Defending Democracy in Exile. Understanding and Responding to Transnational Repression.” Freedom House, 2022.

- Gorokhovskaia, Yana, and Isabel Linzer. “The Long Arm of Authoritarianism.” 24 June 2022. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/world/2022-06-02/long-arm-authoritarianism.

- Gorokhovskaia, Yana, and Isabel Linzer. “Turkey: Transnational Repression Host Country Case Study.” Washington, DC: Freedom House, 2022. https://freedomhouse.org/report/transnational-repression/turkey-host.

- Harris, Shane, Souad Mekhennet, and Yeganeh Torbati. “Rise in Iranian Assassination, Kidnapping Plots Alarms Western Officials.” Washington Post, 1 December 2022, sec. Middle East. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/12/01/iran-kidnapping-assassination-plots/.

- Hellmeier, Sebastian, Rowan Cole, Sandra Grahn, Palina Kolvani, Jean Lachapelle, Anna Lührmann, Seraphine F. Maerz, Shreeya Pillai, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “State of the World 2020: Autocratization Turns Viral.” Democratization 28, no. 6 (2021): 1053–1074. doi:10.1080/13510347.2021.1922390.

- Heydemann, Steven, and Reinoud Leenders. “Authoritarian Learning and Authoritarian Resilience: Regime Responses to the “Arab Awakening”.” Globalizations 8, no. 5 (2011): 647–653. doi:10.1080/14747731.2011.621274.

- International Monetary Fund. “Direction of Trade: Version 2.” ICPSR - Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research, 1984. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR07628.V2.

- Josua, Maria, and Mirjam Edel. “To Repress or Not to Repress—Regime Survival Strategies in the Arab Spring.” Terrorism and Political Violence 27, no. 2 (2015): 289–309. doi:10.1080/09546553.2013.806911.

- Kneuer, Marianne, Thomas Demmelhuber, Raphael Peresson, and Tobias Zumbrägel. “Playing the Regional Card: Why and How Authoritarian Gravity Centres Exploit Regional Organisations.” Third World Quarterly 40, no. 3 (2019): 451–470. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1474713.

- Koesel, Karrie J., and Valerie J. Bunce. “Diffusion-Proofing: Russian and Chinese Responses to Waves of Popular Mobilizations Against Authoritarian Rulers.” Perspectives on Politics 11, no. 3 (2013): 753–768. doi:10.1017/S1537592713002107.

- Koinova, Maria. “Beyond Statist Paradigms: Sociospatial Positionality and Diaspora Mobilization in International Relations.” International Studies Review 19, no. 4 (2017): 597–621. doi:10.1093/isr/vix015.

- Lamb, Kate. “Thai Government Pressed over Missing Lao Activist Od Sayavong.” The Guardian, September 7, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/07/thai-government-pressed-over-missing-lao-activist-od-sayavong.

- Lemke, Douglas, and William Reed. “The Relevance of Politically Relevant Dyads.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 45, no. 1 (2001): 126–144. doi:10.1177/0022002701045001006.

- Lemon, Edward, Bradley Jardine, and Natalie Hall. “Globalizing minority persecution: China's transnational repression of the Uyghurs.” Globalizations 20, no. 4 (2023): 564–580.

- Lemon, Edward. “Weaponizing Interpol.” Journal of Democracy 30, no. 2 (2019): 15–29. doi:10.1353/jod.2019.0019.

- Levitt, Peggy, and Nina Glick Schiller. “Conceptualizing Simultaneity: A Transnational Social Field Perspective on Society1.” International Migration Review 38, no. 3 (2004): 1002–1039. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00227.x.

- Lewis, David. “‘“Illiberal Spaces:” Uzbekistan’s Extraterritorial Security Practices and the Spatial Politics of Contemporary Authoritarianism’.” Nationalities Papers 43, no. 1 (2015): 140–159. doi:10.1080/00905992.2014.980796.

- Libman, Alexander, and Anastassia V. Obydenkova. “Understanding Authoritarian Regionalism.” Journal of Democracy 29, no. 4 (2018): 151–165. doi:10.1353/jod.2018.0070.

- Lührmann, Anna, and Staffan I. Lindberg. “A Third Wave of Autocratization Is Here: What Is New About It?” Democratization 26, no. 7 (2019): 1095–1113. doi:10.1080/13510347.2019.1582029.

- Michaelsen, Marcus. “Exit and Voice in a Digital Age: Iran’s Exiled Activists and the Authoritarian State.” Globalizations 15, no. 2 (2018): 248–264. doi:10.1080/14747731.2016.1263078.

- Michaelsen, Marcus, and Johannes Thumfart. “Drawing a line: Digital Transnational Repression Against Political Exiles and Host State Sovereignty.” European Journal of International Security 8, no. 2 (2023): 151–171. doi:10.1017/eis.2022.27.

- Michaelsen, Marcus. “Silencing Across Borders: Transnational Repression and Digital Threats Against Exiled Dissidents from Egypt,: Syria and Iran.” The Hague: HIVOS, 2020. https://www.hivos.org/assets/2020/02/SILENCING-ACROSS-BORDERS-Marcus-Michaelsen-Hivos-Report.pdf.

- Milanovic, Marko. “The Murder of Jamal Khashoggi: Immunities: Inviolability and the Human Right to Life.” Human Rights Law Review 20, no. 1 (2020): 1–49. doi:10.1093/hrlr/ngaa007.

- Mohyeldin, Ayman. “No One Is Safe: How Saudi Arabia Makes Dissidents Disappear.” Vanity Fair, 29 July 2019. https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2019/07/how-saudi-arabia-makes-dissidents-disappear.

- Moss, Dana M. “The Ties That Bind: Internet Communication Technologies: Networked Authoritarianism, and “Voice” in the Syrian Diaspora.” Globalizations 15, no. 2 (2018): 265–282. doi:10.1080/14747731.2016.1263079.

- Moss, Dana M. “Transnational Repression: Diaspora Mobilization, and the Case of The Arab Spring.” Social Problems 63, no. 4 (1 November 2016): 480–498. doi:10.1093/socpro/spw019.

- Moss, Dana M., Marcus Michaelsen, and Gillian Kennedy. “Going after the Family: Transnational Repression and the Proxy Punishment of Middle Eastern Diasporas.” Global Networks 22, no. 4 (2022): 735–751. doi:10.1111/glob.12372.