ABSTRACT

While the functions of political parties have been extensively defined in the political science literature, it is still an open question whether citizens attribute the same roles to parties. Established theories of parties emphasize their linkage functions geared towards representation or effectiveness. This article investigates where citizens locate parties within these perspectives and whether their understanding of party functions is connected to their democratic values, preference for democratic institutions, and evaluations of the democratic systems. We base our exploratory investigation on original data from a survey run in the UK and Australia in 2020, which includes novel survey instruments measuring citizens’ preferences for party behaviour. The findings show that citizens rate both representation and effectiveness highly and that their preferences are unrelated to their support for democracy. Significant effects of preferences for representative vs direct democracy and the evaluation of their country’s democracy indicate that dissatisfied citizens are more likely to value representation. Importantly, we identify a large group of respondents who cannot choose between representation and effectiveness, which has theoretical and measurement implications.

1. Introduction

How do political parties relate to democracy in voters’ minds? In democratic theory, parties are considered indispensable for democracy.Footnote1 As a group, they are the crucial connection between society and the state in most modern democracies. They establish this connection through linkage functions like organizing elections, mobilizing voters, providing policy alternatives and candidates, and legislating and governing.Footnote2 More generally, they allow citizens to be represented in politics and participate in decision-making and are thus unique organizations because they can respond to voter input and balance different democratic functions.Footnote3 While the link between citizen, party, and democracy is considered to be at the core of liberal democracy, research on what voters themselves think about the party-democracy linkage is extremely limited in scope and theoretical approach. This question is increasingly relevant in the face of an increasingly pessimistic discourse that bears on this relationship: citizen dissatisfaction with democracy and its consequences.Footnote4

Therefore, we need a better understanding of how voters see the link between parties and democracy. This leads to our two-part research question: How do voters expect parties to link to democracy, and what role do attitudes to democracy play in explaining variations in these expectations? Fundamentally, we are interested in whether voters relate to parties as primarily representational, that is, as extensions of their political identity. This includes their ideological views and principles as well as the feeling that parties are made up of people like themselves.Footnote5 Or do people prefer to see parties as functionally effective organizations that are principally focused on winning to influence political outcomes? In democratic systems, parties need to be, on the one hand, effective advocates for their constituents by winning elections and, on the other, organizations that enable input through representation. While in an ideal world, it is easy to see that voters would likely want all of these characteristics equally present, there are constraints and trade-offs in reality. Therefore, we expect that most voters will prefer one direction or another.

While we first investigate how voters relate to parties – primarily as representational or effective institutions – our subsequent analysis explains the variation in such linkages by focusing on perceptions of democracy. In particular, we wonder how voters perceive the functions of parties if they have different levels of support for democracy, different levels of preference for direct versus representative democracy, and different levels of dissatisfaction with their democracy.Footnote6

Our focus on democracy as an explanation is informed by the idea that effectiveness and representation appear orthogonal and complementary at the system level. However, from the perspective of party behaviour and party strategy, they often conflict, requiring trade-offs or balance. Representation may increase the input legitimacy of parties and thus appeal to certain voters. Others may prefer effectiveness in political competition, in the sense that they want their party to win elections and be able to deliver policies, but this often necessitates other strategies, such as strong leadership and a focus on winning elections. Thus, people may privilege specific party characteristics based on their understanding of democracy. A preference for direct democracy may lead people to think of parties as more participatory and member-oriented rather than leader-oriented. Voters dissatisfied with the democratic status quo may be more interested in the effectiveness of bringing about political change.

Our empirical analysis is based on customized survey questions that we were fortunate to include in a survey in Australia and the UK, which was fielded in September 2020 and yielded about 4500 respondents. In our exploratory approach, we proceed by assessing as our independent variable the voters’ attitudes towards democracy, including which type of democracy they prefer and how they evaluate their country’s political actors. We then measure the effect of these attitudes on voters’ expectations towards party behaviour and party strategy, juxtaposing the central linkage functions of effectiveness and representation.

One of our principal findings is that both the representative and the effectiveness dimension are essential to our respondents. However, they regard electoral success – a core component of effectiveness – as markedly less relevant than expected. Furthermore, we find that individuals’ preferences are unrelated to whether or not they support democracy, indicating that party behaviour might not be able to influence democratic stability. At the same time, our analyses suggest that those who prefer direct democracy to the existing representative system and those who believe that there are high levels of political corruption have stronger preferences for representative parties. Thus, respondents who perceive the system as malfunctioning still seem rooted in the promises of representative democracy. Finally, our original survey items uncover a substantial number of respondents who refuse to choose between representative and effective party behaviour. Depending on the question, between 15%–25% of the respondents chose “don’t know” instead. We discuss this finding both in terms of its theoretical and methodological implications.

Our article proceeds as follows: We first present our theoretical argument in detail, showing the relevance and complexity of party linkage functions and how they should be related to individuals’ support for democracy and its different components. We then explain our concept operationalization and survey methodology. Following brief descriptive analyses of how vital the linkage functions are for our respondents, we present our models and discuss our findings.

2. Theory

At the core of our investigation is the idea of democratic linkage. The fundamental premise of this theory states that parties must connect to citizens and the state to remain legitimate.Footnote7 Pedersen and Saglie describe the central role of political parties as “the creation of linkage between elected representatives and the mass public”.Footnote8 They act as intermediaries that solicit, aggregate, articulate, regulate citizen demands and facilitate citizen participation in democratic institutions. In this, parties fulfil the representation function, allowing for input legitimacy to be established in democratic decision-making.Footnote9 They do so by mobilizing people to vote for them and bringing their voters’ preferences and views into the political process.

For democracy to function, however, representation is not enough; effectiveness at competition is equally important. This entails providing alternative policy options, supplying competent candidates, and engaging in various campaigning strategies to maximize the chances of being elected. Indeed, for theorists such as Schumpeter, competition based on political alternatives for the right to govern was most important.Footnote10 According to him, democracy is an “institutional arrangement for bringing about political decisions in which individuals acquire decision-making power through a competitive struggle for the popular vote”.Footnote11 Being effective, thus, refers to the idea that parties need to win elections to advocate for their constituents and deliver policies that address their concerns. In this case, the linkage function to democracy is not the representativeness of parties’ proposed policy agenda but rather the likelihood of its adoption. In this study, therefore, we focus on the central aspect of electoral effectiveness because it is first in a theoretical chain leading to policy and government effectiveness.

Scholars have pointed out that fundamental democratic principles and party goals can conflict with each other. Mair has argued that democratic systems are increasingly dominated by concerns of political responsibility over representativeness and identifies this as an increasing democratic deficit.Footnote12 Strom has shown that political parties, reacting to the incentives of elections and struggling between voter demands and government responsibilities, shift between focusing on policy, office and vote.Footnote13 These are two prominent examples of how political actors navigate such tensions. We, however, turn to the perspective of citizens.

A slowly growing body of literature investigates citizens’ expectations about the role of representatives. Studies have shown that citizens differ in their preferences for different types of representation, in particular whether they prefer trustee, delegate or symbolic, nation or party voter-focused representation.Footnote14 Other studies have highlighted the theoretical conflict between responsiveness and responsibility or focused on the particular role of electoral pledges and voters’ valuation of the related accountability mechanism.Footnote15 All of these studies show that citizens’ expectations vary widely and highlight the complexity of voters’ understanding of representation and party behaviour. Going beyond the focus on representation types and the role of electoral pledges contrasted with other decision-making heuristics, our study focuses on a broader set of different party behaviours and asks how citizens’ understandings of democratic principles apply to political parties and are thus reflected in the preferences of individuals for party processes and activities. Specifically, we examine how citizens relate their understanding of democracy to how parties should be organized and function, not only in the abstract but also in very concrete ways, for example, when principles such as political effectiveness and representation compete with each other. For example, should electoral success trump ideology, or should a party’s agenda be shaped by its members or leadership?

More directly speaking to our study’s purpose, findings by Dommett from the United Kingdom suggest that voters want parties to be transparent, communicative, reliable, principled, inclusive, and accessible and to act with integrity.Footnote16 Evidence also indicates that citizens view parties as self-interested, voter-focused, and unreliable organizations focusing on short-term demands rather than long-term interests. While voters may have different ideas about what makes parties effective, it is also evident that unity, leadership, and a clear party profile are organizational and strategic aspects that we commonly associate with political effectiveness. Indeed, Green and Jennings have argued that citizens’ views of parties are heavily informed by an “evaluation of issue competence and government performance”Footnote17 In sum, effectiveness, which matters for competing competently and achieving the desired political outcome, and representation, which matters for the inclusion of the citizenry in the political process, are the two central dimensions underlying the party-democracy link. However, we wonder how voters balance these expectations and on what basis they do so.

In what follows, we address what may explain the variation in these expectations and, specifically, what role democracy plays in this. Numerous studies have shown that individuals in democratic states relate to and support the idea of democracy in multiple ways.Footnote18 This includes the extent to which voters value the idea of democracy and think that democracy is the only acceptable way to organize society and legitimize the government.Footnote19 Moreover, support for democracy may be reflected in views about institutions and norms, or citizens may relate to their country’s specific political actors and current officeholders.Footnote20 Building on the idea that citizens might evaluate the institutional setup of their democracy, it is fruitful to distinguish the two dominant democratic institutionalizations: representative democracy, which is strongly entwined with the role of political parties, and direct democracy, which formally cuts parties out of the decision-making process in favour of citizen participation. Finally, rather than asking voters more generally about their (dis)satisfaction with democracy, which risks tapping again into democracy as an abstraction, their evaluations of the existing political arrangements, institutions, and leaders seem a more appropriate conceptualization for this study. In this way, we can capture the difference in conceptualization between democracy as a normative system and as a working model experienced by citizens.

As a starting point for combining the logic of democratic support and how citizens might relate to parties’ linkage functions, we refer to an ongoing debate related to the question of how parties should behave within the democratic system.Footnote21 Our central question is whether they should prefer effectiveness or representation concerns.

Generally, the democracy literature identifies a growing dissatisfaction with democratic actors and institutions. Here, we see two general problems the literature identifies that bear on our research. In one case, the argument is that attitudes towards democracy as a fundamental value have changed because the system is perceived to be failing a majority of the people, who find themselves increasingly tending towards illiberal or authoritarian solutions. If this view is correct, we should see a clear separation between individuals who hold democratic values and those who do not hold democratic values regarding their preferred party behaviour. In particular, we would expect those who have turned away from democratic principles to favour parties to be as effective as possible. This is not to say that effectiveness is undemocratic per se, but rather that those who hold undemocratic views should privilege the instrumental aspect of parties that win elections and are strong decision-making machines over the input- and consensus-oriented aspects of representation.

H1: Respondents who do not share democratic values are more likely to favour party effectiveness over representation than respondents who share democratic values.

The alternative argument in the democracy literature is that support for liberal democratic principles remains strong but that people are disappointed with how the current political system works for them.Footnote22 In this case, dissatisfaction stems from the discrepancy between citizens’ expectations and the perceived inadequate response of democratic institutions to social and economic change.Footnote23 Some argue that this is due to citizens’ inflated expectations by focusing on their entitlement but never their duties.Footnote24 Others blame people’s dissatisfaction on the failure or crisis of representation and lack of responsiveness.Footnote25 Here, people’s grievances are not directed at democracy but specifically at the performance and configuration of, in our case, political parties. If this is correct, we should not see differences in their evaluation of democracy.

Several studies support the idea that disaffection does indeed motivate political participation, which is a crucial means to ensuring representativeness.Footnote26 However, the literature disagrees on the data sources and the importance of the underlying emotional dimension that animates disaffection.Footnote27 While political participation is understood in a broader sense in the literature, specifically encompassing various forms of social activism, the same logic applies to participation in political parties to affect political change. Unfavourable evaluations of the existing system can thus motivate joining political parties and emphasizing representativeness. The idea is that the democratic system has become distant from citizens and no longer works. Greater citizen participation in democratic institutions would then be a plausible remedy. Since people are seen as the solution to the democratic deficit, democracy based on citizen participation should be preferred. Thus, we would expect individuals who support ideas of direct democracy over representative democracy to have more positive attitudes towards representation linkages than towards effectiveness issues.

H2a: Respondents who value direct democracy over representative democracy are more likely to favour party representation over effectiveness than respondents who value representative democracy over direct democracy.

H2b: Respondents who value direct democracy over representative democracy are more likely to favour party effectiveness over representation than respondents who value representative democracy over direct democracy.

H3a: Respondents who perceive their democratic system as dysfunctional are more likely to favour effectiveness as a party function than respondents who do not perceive their system as dysfunctional.

H3b: Respondents who perceive their democratic system as dysfunctional are more likely to favour representation as a party function than satisfied respondents who do not perceive their system as dysfunctional.

3. Data and methods

To investigate the relationship between attitudes towards democracy as a system and attitudes towards the role of parties in democracies, we utilize a survey with tailor-made questions that we conducted in Australia and the UK in September 2020 using the online survey platform Lucid. We asked the same questions in both countries. Our samples included 5003 respondents (UK: 2552; Australia: 2451). To balance some of the disadvantages from the fact that our samples are randomly drawn from underlying convenience samples of the populations, we used quotas for the standard demographic attributes known to influence political attitudes: gender, age, education level and region of residence.Footnote35

To test our argument, we selected two ideally suited cases for such an exploratory study: Australia and the United Kingdom. Both countries have closely related political environments, use majoritarian electoral systems and have party systems dominated by two parties that usually form single-party governments, and comparable political cultures. This high similarity allows us to pool the samples, given that there are no prima facia theoretical reasons to predict systematic differences, which is advantageous for our study because it focuses on a relationship that has not been really explored before. However, this choice also leads to the limitation that we cannot empirically generalize to proportional, multi-party systems.

At the same time, using two closely related political systems is also an advantage when field-testing innovative survey items, as we do in this study. In addition, other relevant data for appropriate cases were not available to examine our hypothesis. Therefore, we were fortunate to include a set of specific questions derived from our research design in two ongoing surveys. Because these surveys focused on entirely unrelated questions about public perceptions of foreign policy, they did not affect our party- and democracy-based survey items. Despite the high degree of similarity in our country cases, we account for possible residual differences across countries by including a fixed country effect in all analyses.

When measuring people’s attitudes towards the linkage functions of political parties, it is impossible to capture them directly by asking voters bluntly whether they prefer one particular linkage function to another. This would be far too abstract and open to interpretation of what these linkage functions mean in a person’s mind. Instead, we break down these linkage functions into concrete examples of party behaviour. shows the survey items that underlie our dependent and main independent variables. While we rely on well-established survey items for our independent variables on democracy, we developed new items for our dependent variables. These items went through multiple rounds of feedback and refinement with survey experts in Europe and Australia. The survey itself started with a soft launch of 100 respondents that elicited feedback from these respondents about the survey items, which we used for the final refinement of the wordingFootnote36.

Table 1. Measures of attitudes towards democracy and the role of parties in democracy.

3.1. Measuring attitudes towards parties’ roles in democracy

We included new questions that focused on the importance respondents attach to the linkage functions of political parties in the democratic system (). First, as representative democracy is based on competition between parties and parties vying to win elections, we operationalize one aspect of effectiveness as electoral success. We ask respondents how important election success itself is to them. As electoral success has a different meaning for supporters of (in particular) large vis-à-vis small parties in the majoritarian systems of our two case countries, we did not define the term “winning” further. Thus, respondents were free to interpret electoral success as they saw fit, such as a takeover of the government, a greater share of seats in parliament, an increase in the percentage of votes, or some other meaning. We focus on the idea that electoral success is more or less important. However, because electoral success often requires parties to adapt to become more attractive to a larger share of the electorate, we ask respondents how important winning elections is in contrast to the parties’ ideologies and general principles. The two later aspects can be subsumed under the representation linkage function. We distinguish between party ideology and party principles because parties can stand for different values, and we want to ensure that we have a full measure of representation. The classical political party research literature focuses heavily on the party programme and policies based on a general ideology that the party represents and is often named after. However, parties can also stand for other principles like internal democracy, gender parity in the leadership or strong hierarchical role allocations. Thus, we include the more general term “principles” and leave it to the respondents to fill it with specific meaning, while the language clarifies that we aim at the ideas that the party stands for. This becomes even more evident in the survey items as all respondents also see the item that includes ideology and principles are juxtaposed with electoral success.

Another way of measuring the importance of effectiveness is to focus on the role of party leaders. While the relationship between party leaders and members might primarily seem to be a question of intraparty democracy, it is also central to parties’ functions in the democratic system. A party’s agenda, shaped by the party leader, tends to be more internally coherent and is supported by the party’s power structure. As such, it is likely to have greater political or electoral impact but is less representative of a party’s diverse groups and supporters. Conversely, a more broadly representative agenda may be preferable from the standpoint of democratic inclusiveness, but likely entails compromises and potential inconsistencies, making a party’s message vulnerable to political attack. Thus, individuals who value effectiveness should expect that the policy programme (and thus the party’s agenda and future party behaviour) reflect the preferences of the party leader to whom the tasks of explaining, defending, advertising and enacting this programme fall. Individuals who value representation will expect that the programme reflects the party membership, which is the societal base of the party. Thus, we include a survey item that juxtaposes the role of party members and leadership in the decisions about the policy programme.

The central component of the linkage “representation” is the primary function of political parties to represent the interests of their supporters. This lies at the heart of most theories of party and electoral behaviour. Thus, we ask respondents how important interest representation is for them. Furthermore, recent studies of the role of parties and voter attachment to them have shown that some individuals reject the theoretical assumptions of rationality that underlie notions of electoral success and advocacy. Instead, voters form tribal or identity-based connections to parties, which function through emotions instead of rationality. But this, too, could be a form of linkage through representation, and we include a survey item for affective representation. Here, we should note that this does not refer to a descriptive subcategory of citizens but rather to an individual’s sense of emotional and psychological connection to the party and the people for which it generally stands.

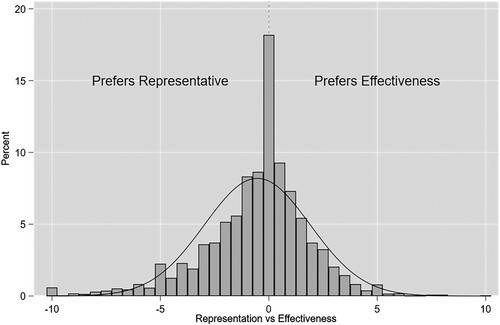

Because these indicators follow two different structures, we construct two dependent variables that measure respondents’ preference for effectiveness versus representation in the following way: First, we combine the continuous variables of support for representation and winning elections. We calculate respondents’ general preference for the representative function of parties by averaging the two indicators for interest and affective representation. We then subtract the resulting variable from the variable of support for the primacy of winning elections.Footnote37 This calculation yields the first dependent variable, which is continuous, ranging from −10 to 10, with negative values denoting a stronger preference for representation and positive values stating a greater preference for effectiveness. In short, in this configuration, voters were not directly forced to weigh preferences against each other because they did not have to make dyadic choices but instead rated their preferences on a scale. The voting decisions resulting from this preference hierarchy show a slight overall preference for representation, with an average value of –0.53 (standard deviation of 2.43, ).

Our second set of dependent variables raises the bar for respondents in the sense that competing preferences between representation and effectiveness can also be viewed as dyadic orderings of important party activities, such as the decision to prioritize electoral success over party ideology or party principles or vice versa. This also includes the dyadic choice between whether the party programme should, in the respondents’ mind, reflect the leadership’s agenda or rather that of the party members.

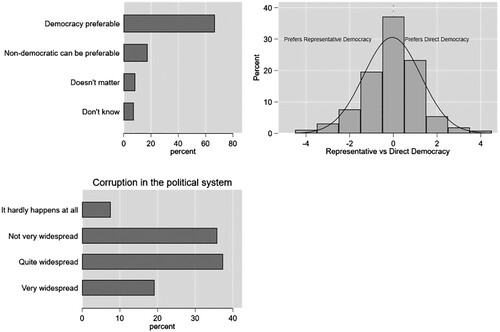

To obtain a clear ordering of preferences concerning this second set of dependent variables juxtaposing representation and effectiveness, we combined the “agree” and “strongly agree” response categories into one preference expression each. shows the response frequencies. Notably, the “don’t know” option is highly populated, indicating that these choices are hard for respondents, and they might not have ready-made decision-making rationales at hand.

Table 2. Distribution of preference for representation and effectiveness as party functions.

If we break this down further, we notice that “ideology” and “principle” are the most frequently selected choices through which people relate to parties. Such expression of a distinct political identity is, thus, perceived as an important function of parties and highlights an ideational bond between the individual and the party. Thus, among the key party roles within a democracy, our respondents rate interest representation as the most important. This result is consistent with the most widely used models of representative and party democracy.

Remarkably, “success” is always the lesser choice by a wide margin when pitted against ideology or principle. In both cases, representation “wins” over effectiveness, each rated as more important by about 80% of respondents. We only see an outcome that does not favour representation when we pit the party leader’s influence against the party members’ influence. However, the preference shares are not far apart, and the number of undecideds is very large. Overall, we may conclude from these results that people relate to parties primarily through representation. Effectiveness is a much less desired party function. Yet, there is a relatively smaller but clearly present group for whom parties primarily serve the goal of functional effectiveness.

Comparing the descriptive analyses for our two sets of dependent variables, we have a first important finding. First, when respondents can express their support for representation and effectiveness individually, they rate them relatively equally. Second, when made to choose, the majority of respondents chose representation. We argue that this reflects the difference between considering abstract principles singularly and measuring preferences when these principles are presented in a dyadic fashion. It seems that in the abstract, respondents tend towards balancing ideas that each have clear positive implications. At the same time, when asked to choose, they can articulate a clear preference.

3.2. Measuring attitudes towards democracy

To examine the impact of citizens’ relationship with democracy on their assessment of the role of parties as a link, we measure three levels of attitudes towards democracy: democracy as a value, the democratic institutional setup and evaluation of their country’s political actors. We operationalize the value of democracy in a question that contrasts respondents’ full belief in democracy with the possibilities that non-democratic options are preferable, or that it does not matter which system prevails, or that respondents do not know which they prefer. Regarding citizen support for the institutional implementation of democracy, we focus on the most common and party-based form of democracy and measure their preference for representative democracy. Furthermore, we also measure their support for direct democracy as the non-party-based alternative to institutionalized representative democracy. We combine these two indicators by subtracting respondents’ agreement to representative democracy from their agreement to direct democracy. Thus, this variable is positive when respondents prefer direct democracy over representative democracy and negative in the opposite case.

Finally, to measure respondents’ perception of whether their democratic system is functioning or dysfunctional, we refrain from using common indicators such as popularity ratings of politicians and parties or satisfaction with democracy. These are directly related to parties and could lead respondents to think of the respective governing party when answering our questions on party attitudes. Instead, we employ respondents’ perceptions of the extent of political corruption in their countries to determine whether they believe that political actors in their countries act broadly according to basic democratic principles. shows the distribution of these three main independent variables in our dataset.

4. Analysis

Our analysis focuses on the fundamental functions of political parties and their role in the democratic system. We test the effect of democratic attitudes on how much respondents value representation and effectiveness as well as electoral success – even to the detriment of ideology and principles – as well as leadership. The analysis is based on our online survey in Australia and the UK in September 2020. Descriptive statistics can be found above and in the Appendix for the control variables. In our models, we use standard control variables at the individual level (age, gender, education, interest in politics as well as voter of a major vs a minor party) and the respective measures and their descriptive statistics can be found in the Appendix (Table A2)

4.1. Democratic values and support for parties’ systemic roles

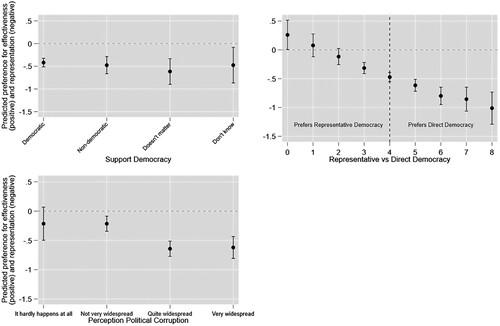

For our analysis of which democratic attitudes are associated with preferences for different party functions, we first focus on a limited continuous variable that captures the relative support for representation versus effectiveness. The findings for the hypothesized effects are presented in , while the results with the control variables can be found in the Appendix. However, due to the complexity of these variables, we turn to the marginal effect plots in for our substantive interpretations that give us a clearer picture.

Figure 3. Marginal effects of Democratic Attitudes on Preference for Representation vs Effectiveness (DV1). Note: Positive predicted effects denote a greater preference for effectiveness; negative predicted effects denote a greater preference for representation.

Table 3. Effect of attitudes towards democracy on attitudes to parties’ effectiveness vs representation.

First, we test H1 that respondents who do not share democratic values are more likely to favour party effectiveness over representation than respondents who share democratic values. We detect no consistent relationship between those prioritising effectiveness or representation and support for democracy. While we can see from the consistently negative effects that there is a general preference for party representation over effectiveness, this is not motivated by respondents’ differing views of democracy; as a result, we reject H1.

However, the marginal effects plot shows a difference between respondents who prefer direct and representative democracy when weighing a political party as a representative organization against a politically effective organization. Here, we test hypothesis 2a, that respondents who value direct democracy over representative democracy are more likely to favour party representation over effectiveness than respondents who value representative democracy over direct democracy, the reverse hypothesis 2b. The right-hand panel of shows that respondents in the United Kingdom and Australia who prefer a representative democratic system have a relatively stronger preference for parties’ effectiveness function. At the same time, those who are relatively more in favour of direct democracy are more likely to prefer parties to be representative political actors. This effect is in line with H2a, stating that respondents who value direct democracy over representative democracy should be more likely to favour party representation over effectiveness. In turn, this finding contradicts the alternative H2b. Thus, we find evidence that proponents of direct democracy also seek greater self-representation in political parties, which we had argued and supports our hypothesis. From the perspective of party reform for more democracy, this is encouraging, as it suggests that citizens may be willing to have their needs, expressed as a preference for direct democracy, met through existing representative mechanisms.

Let’s take this further by considering dissatisfaction with the existing democratic system and testing hypothesis 3a, that respondents who perceive their democratic system as dysfunctional are more likely to favour effectiveness as a party function than respondents who do not, and the reverse effect hypothesized in H3b. We find that those respondents who consider corruption “quite widespread” or “very wide spread” were significantly more likely to favour representation than the reference group, which is consistent with H3b. Thus, it seems that the frustration with a system perceived as deficient is not rooted in a perception that parties need to be more effective agents, as we hypothesized in H3a. Instead, our findings suggest that dissatisfaction with the system leads respondents to favour parties to be representative and that respondents count on robust representative mechanisms as the cornerstone of the democratic system. A positive interpretation of this finding is that political parties have an opportunity to reconnect citizens to their democratic regime by strengthening their actual and communicated interest and affective representation.

4.2. Choices between parties’ systemic roles

In the second step of our analysis, we turn to those of our original survey questions that directly contrasted different party roles. Using easy-to-understand and practical examples of different functions that respondents might expect or prefer from parties, we presented them with three choice questions that asked them to decide between (a) party ideology and electoral success, (b) the party’s (broader) principles and electoral success, and (c) the voice of the members, who make up the party on the ground, and the voice of the leader, who stands for the aspect of the party that focuses on effective campaigning and concerted presentation with a view to parliament and government.

As mentioned above, 15%–25% of our respondents could not make these decisions and answered “don’t know”. Since this is a particularly high proportion, we interpret this result as a substantive effect. We assume that these are indeed difficult decisions for which many people cannot think of a valid reason to make such a choice (thus, this should not be interpreted as laziness on the part of the respondents). As such, we perceive the “don’t know” respondent group in all three choice questions as a substantive group and use them as the reference group in our multinomial regression analyses. As a robustness check, we also run the equivalent logistic regressions that exclude the “don’t know” responses. The results can be found in Appendix Table A5 and confirm our findings regarding our hypotheses. At the same time, it shows that excluding “don’t knows” results in losing important information, as highlighted below.

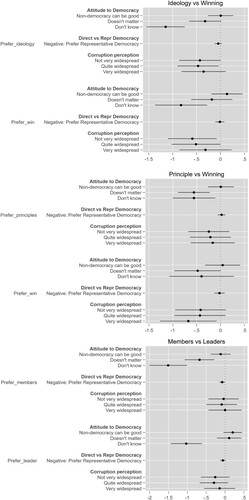

shows the results of these analyses, again focusing on our three sets of hypothesized explanatory variables that are connected to respondents’ views on democracy. There are two main findings in this Table, which are also corroborated by the effect plots in . First, there are very few connections between democratic attitudes and respondents’ choices. We reject H1as non-democratic values have no effects at all. Similarly, we reject H2a and H2b as respondents’ views on representative and direct democracy do not affect these choices either. The only significant effect for those respondents who prefer party members’ voice over party leaders is substantially very small. We also reject H3a and H3b, here, as respondents’ system evaluations also do not matter. In summary, we must reject the notion that respondents, when given a choice of how parties might act, would fall back on higher-order system preferences as decision heuristics. Whether this means that they use other heuristics or are driven by non-rational considerations needs to be investigated in other studies.

Figure 4. Coefficient plots for 3 models in , effects on likelihood to be in one preference group instead of having answered “don’t know”.

Table 4. Multinomial regressions, coefficients and significance only, reference group in each choice question is the answer “don’t know”.

Our second main finding is that we find only significant and substantive effects among those who do not know or care about the role of democracy. The results in show that the effect of these attitudes is systematically negative, which means that these respondents are also more likely to have answered “don’t know” to the three choices that are our dependent variables. If we compare this aspect with Table A5 in the Appendix, for which we excluded the “don’t know” category in the dependent variables, we see that this exclusion leads to most of these effects disappearing. This confirms that there is a clear link between the “don’t knows” in our dependent and independent variables. Thus, the second important finding from this analysis is that those indifferent or unable to decide on democratic issues have the same attitude towards the role of political parties in the democratic system and that excluding them results in the loss of a vital aspect of these patterns.

Overall, our results suggest that respondents do not equally recognize all of the democratic linkage functions of parties, as representation is more important than electoral success and exercising leadership, which clearly differs from some of the expert opinions about parties. Moreover, how respondents value these two functions in relation to each other is only partially related to their appreciation of democracy. In general, it does not matter whether respondents value democracy or not, implying that undemocratic citizens do not seem to seek stronger leaders or more effective party behaviour. However, we find some correlation between preferences for democratic systems and perceptions of their democratic experiences and varying levels of support for effectiveness.

Another important finding from our analyses concerns the type of questions used to elicit respondents’ attitudes. The literature suggests that it is advantageous to confront respondents with clear choices to capture their preferences directly, whereas one-dimensional questions in support of a concept risk eliciting a falsely high level of support. Indeed, conjoint surveys and related experiments are based on this fundamental idea. We argue that the different answer patterns for our two sets of dependent variables confirm this and highlight the difference between measuring the support of principles in the abstract and measuring preferences when presented in a dyadic fashion. While the questions about abstract principles show relationships with the independent variables that are also abstract principles (support for democracy, etc.), the preference measures do not. This indicates that individuals have relatively clear cognitive systems of support for principles, which do not work anymore when these principles are brought in conflict with each other.

However, our results indicate that this may be risky as the demands of decision-making for preferences between competing ideas is substantially higher than deciding on how much one supports a single principle. Our results show the consequences of this, since many respondents would not answer the more complex question and those who answered did not seem to follow any discernible pattern. Yet, given the limitations of our survey, we cannot determine with certainty whether the substantial number of “don’t know” responses reflect a genuine attitude that might be explained by other political, psychological or sociological factors, whether “don’t know” is simply an escape from a situation of cognitive overload, and whether a random selection of people simply do not have formed opinions.

5. Conclusion

This article asks how voters expect parties to link to democracy and how best to explain the differences between these expectations. In doing so, we question to what extent voters perceive the linkage functions of parties in the way that the literature on parties and democracy would have us believe. Experts often assume that party supporters are guided by rational policy preferences for which effectiveness and winning should matter most. We situate our inquiry within the closely related debate about the backsliding of democracy. Thus, we want to know whether democracy as an intrinsic value, together with specific models of democracy, influences people’s perceptions of parties or whether any effect is based on people’s perceptions of how democracy actually works. We seek, first, to compare the effect of attitudes towards dimensions of party democracy and, second, to examine the causes of attitudes towards the democratic linkage functions of representation, on the one hand, and effectiveness, on the other.

Putting all our findings from original surveys fielded in Australia and the UK together, we find several clear patterns: First, the effectiveness dimension is much less important to our respondents than expected. When presented with a choice, the majority of respondents consistently rate certain aspects of representation higher than electoral success. Then, when forced to choose either leadership or member input in the party manifesto, respondents split into two equally sized groups. Second, we find that attitudes towards representation and effectiveness as democratic roles of parties are generally not associated with individuals’ support for the democratic system. Respondents with undemocratic attitudes do not clearly prefer either dimension of party behaviour. This result, if confirmed in other contexts, means that a greater focus by parties on improving representation or ensuring a sense of achievement for their supporters cannot remedy undemocratic attitudes among citizens.

Third, we find that the relationship of our Australian and British respondents to the representation and effectiveness dimensions of political parties appears to be related to their preference for representative and direct democracy and their assessment of their country’s democracy. Respondents who prefer direct to representative democracy at the system level and respondents who perceive their democratic system as dysfunctional tend to have a greater preference for the representative function of parties. Both results suggest that those sceptical of the existing system prefer actors who better fulfil the promises of interest and affective representation. Thus, rather than replacing the system with actors who effectively bring about change, there seems to be a strong attachment to the ideas of representative democracy.

Our decision to explore this innovative research question and ask our original survey questions in Australia and the United Kingdom had the benefit of a larger pool of respondents and, thus, extensive variation in both the dependent and independent variables. While the comparability of the selected party systems was important for this exploratory study to assess the robustness of our results, and thus an advantage, the similarities between the cases also have their limitations. Further research clearly requires extending this study to other party systems and contexts, particularly proportional multiparty systems with coalition governments. However, we deliberately focused on basic questions about democracy related to representation versus electoral effectiveness and leadership versus membership while staying away from more complex scenarios such as parties in government and policymaking. Since the principles of representation and effectiveness are fundamental to democracy, our results should transfer well. Nevertheless, we must acknowledge that empirical work on more party systems and party types is needed but must leave this aspect to future studies.

Finally, we make a most unexpected and potentially consequential observation when we compare the results of our two analyses. On the one hand, the analysis built on survey items asking about respondents’ support for individual party behaviours (advocacy, winning elections, etc.) shows (a) only a slight preference for party representation and (b) a relationship between certain democratic attitudes and party behaviour preferences. On the other hand, the analysis built on survey items forcing respondents to choose between representation and effectiveness exhibits (a) a clear preference for party representation but (b) no relationship with democratic attitudes. Since we did not expect these strong differences, we lack further survey items to explain this discrepancy.

However, we suggest a possible mechanism that might be at play here: First, it could be that the questions about individual party functions produce strong social desirability effects. These effects could lead respondents to agree with everything and show little variation in their relationship to the representative system in general. If further studies can empirically corroborate this argument, the first set of questions might be problematic from a measurement point of view. Second, it might be that making respondents choose between mutually exclusive dimensions of partisan behaviour forces them into a decision-making dilemma, even if respondents do not perceive them as conflicting alternatives. This situation could be particularly problematic if respondents view this as an intrinsically false choice and decide more or less randomly, simply because we asked them to do so. However, the opposite could also be the case in that respondents refuse to answer because they believe representation and effectiveness are equally important and necessary. In the latter scenario, respondents fall into three groups: those who prefer representation, those who prefer effectiveness, and those who value both equally. The large number of “don’t know” responses support this conclusion and might mask such a third group. Determining which of these explanations holds requires careful further research and employing dedicated surveys.

Overall, both our approach and our results call into question certain experts’ assumptions about the role that citizens attribute to political parties in democracies. Resolving these issues is highly valuable to better understand attitudes towards political parties and democracy. We hope this study has made a first significant contribution in this direction.

Authors’ contributions

Both authors equally contributed to this article.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (964.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data, replication instructions, and the data’s codebook will be provided on the author’s Dataverse page.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Annika Werner

Annika Werner is Head of School at the School of Politics and International Relations, Australian National University. She is an expert on comparative and European politics, with a special research focus on populism, party behaviour, representation and public attitudes in democracies. Her research has been published in journals such as the Journal of European Public Policy, Democratization, Party Politics, and Electoral Studies. Her book “International Populism: The Radical Right in the European Parliament”, co-authored with Duncan McDonnell, is published with Hurst/Oxford University Press. Annika is Steering Group member of the Manifesto Project (MARPOR, former CMP) and of the ECPR Standing Group Extremism and Democracy.

Reinhard Heinisch

Reinhard Heinisch is Professor of Comparative Austrian Politics at the University of Salzburg and chair of the department. His main research is centered on comparative populism, Euroscepticism, political parties, the radical right and democracy. His research has appeared in journals such as the Journal of Common Market Studies, Journal of European Political Research, Party Politics, West European Politics, Democratization, a.a. His latest book publications are The People and the Nation: Populism and Ethno-Territorial Politics (Routledge 2019), Political Populism/Handbook (Nomos 2021), Politicizing Islam in Austria (Rutgers University Press 2024).

Notes

1 Schattschneider, “Party government,” 1.

2 Lawson, “Political Parties and Linkage: A Comparative Perspective.”

3 Bartolini and Mair, “Challenges to Contemporary Political Parties,” 339; Caramani, “Understanding the Party Brand: Experimental Evidence on the Role of Valence,” 60; Mair, “Representative Versus Responsible Government,” 5.

4 Van Biezen et al., “Going, Going, … Gone? The Decline of Party Membership in Contemporary Europe.”

5 In this article, we consider ideology as part of the representation dimension since sharing a belief system is a central aspect of people joining together politically and defining themselves as a group in relation to other groups.

6 While these functions also play a role for intra-party organization and decision-making, this article focuses on parties’ roles in the system.

7 Lawson, “Political Parties and Linkage: A Comparative Perspective.”; Deschouwer, “Pinball Wizards: Political Parties and Democratic Representation in the Changing Institutional Architecture of European Politics.”

8 Pedersen and Saglie, “New Technology in Ageing Parties: Internet Use in Danish and Norwegian Parties,” 361.

9 cf. Dahl, “Polyarchy,”“On Democracy.”

10 Schumpeter, “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy.”

11 Schumpeter, “Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy,” 269.

12 Mair, “Representative Versus Responsible Government.”

13 Strom, “A behavioral Theory of Competitive Political Parties.”

14 Bengtsson and Wass, “Styles of Political Representation: What Do Voters Expect?”; Carman, “Public Preferences for Parliamentary Representation in the UK: An Overlooked Link?”; Matthiess, “Retrospective Pledge Voting: A Comparative Study of the Electoral Consequences of Government Parties’ Pledge Fulfilment.”

15 Dommett, “The Reimagined Party: Democracy, Change and the Public.”; Dommett & Temple, “The Expert Cure? Exploring the Restorative Potential of Expertise for Public Satisfaction with Parties.”; Werner “What Voters Want from Their Parties: Testing the Promise-keeping Assumption.”; Werner, “Voters’ Preferences for Party Representation: Promise-keeping, Responsiveness to Public Opinion or Enacting the Common Good.”

16 Dommett, “The Reimagined Party: Democracy, Change and the Public.”

17 Green and Jennings, “The Politics of Competence,” 488; Butler and Powell “Understanding the Party Brand: Experimental Evidence on the Role of Valence”; Green and Jennings, “The Politics of Competence: Parties, Public Opinion and Voters.”; Stokes, “Valence Politics”; Tilley and Hobolt, “Is the Government to Blame?”

18 Inglehart, “How Solid is Mass Support for Democracy—And How Can We Measure It?”; Diamond, “Developing Democracy: Toward Consolidation.”

19 Lipset, “Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics.”

20 Easton, “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support.”; Norris, “Is Western democracy backsliding? Diagnosing the risks.”

21 Kriesi, “The Transformation of Cleavage Politics: The 1997 Stein Rokkan Lecture.”; Norris and Inglehart, “Cultural Backlash: Trump. Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism.”; van Ham et al., “Myth and Reality of the Legitimacy Crisis: Explaining Trends and Cross-National Differences in Established Democracies.”

22 Kriesi et al., “The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Social Movements.”

23 Green-Pedersen, “A Giant Fast Asleep? Party Incentives and the Politicisation of European Integration”; Hooghe and Marks, “Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage.”

24 Blühdorn, “Simulative Demokratie. Neue Politik nach der postdemokratischen Wende.”

25 Kriesi et al., “The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Social Movements.”; Ferrin, “An Empirical Assessment of Satisfaction with Democracy.”

26 van der Meer and van Ingen, “Schools of Democracy? Disentangling the Relationship between Civic Participation and Political Action in 17 European Countries.”; Marien et al., “Inequalities in Non-institutionalised forms of Political Participation: A Multi-Level Analysis of 25 Countries.”; Norris, “Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited”; Grasso and Giugni, “Protest Participation and Economic Crisis: The Conditioning Role of Political Opportunity.”; Grasso et al., “Relative Deprivation and Inequalities in Social and Political Activism.”

27 Goodwin et al., “The Return of the Repressed: The Fall and Rise of Emotions in Social Movement Theory”; McAdam, “Social Movement Theory and the Prospect for Climate Change Activism in the United States.”

28 Noam, “The Efficiency of Direct Democracy.”; Wagschal, “Direct Democracy and Public Policymaking.”; Feld and Kirchgässner, “On the Economic Efficiency of Direct Democracy.”

29 Morlino, “Crisis of Parties and Change of Party System in Italy 1996.”; Pasquino, “Italy: The Triumph of Personalist Parties.”

30 Katz and Mair, “The Cartel Party Thesis: A Restatement.”; Rooduijn et al., “Expressing or Fuelling Discontent? The Relationship between Populist Voting and Political Discontent.”; Spruyt et al., “Who Supports Populism and What Attracts People to it?”; van Hauwaert and van Kessel, “‘Beyond Protest and Discontent: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support”; Koch et al., “Mainstream Voters, Non-voters and Populist Voters: What Sets Them Apart?”

31 Abou-Chadi and Wagner, “The Electoral Appeal of Party Strategies in Post-Industrial Societies: When Can the Mainstream Left Succeed?”; Immerzeel and Pickup, “Populist Radical Right Parties Mobilising ‘The People’? The Role of Populist Radical Right Success in Voter Turnout.”

32 Dommett, “The Reimagined Party: Democracy, Change and the Public.”

33 van Hauwaert & van Kessel, “Beyond Protest and Discontent: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support.”

34 Heinisch & Wegscheider, “‘Disentangling how Populism and Radical Host Ideologies Shape Citizens’ Conceptions of Democratic Decision-Making.”; Zaslove et al., “Power to the People? Populism, Democracy, and Political Participation: a Citizen’s Perspective.”

35 See Appendix Table A1 for the quotas and underlying population shares.

36 While this wording cannot preclude respondents from imagining their already preferred party, it is worded so openly that even then it appeals to that party’s ideal behaviour.

37 We measure the absolute difference in preference between the two principles. This is the property in which we are interested, since we want to know how much respondents value representative versus effective organizations. For our question, it does not matter whether respondents strongly or weakly agree with the principles themselves (e.g. whether the value of 1 comes from the difference between 4 and 5 or between 8 and 9), but only the difference between them. Therefore, we do not standardize the variable.

Bibliography

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, and Markus Wagner. “The Electoral Appeal of Party Strategies in Postindustrial Societies: When Can the Mainstream Left Succeed?.” The Journal of Politics 81, no. 4 (2019): 1405–1419. doi: 10.1086/704436

- Bartolini, Stefano, and Peter Mair. “Challenges to Contemporary Political Parties.” In Political Parties and Democracy, edited by Larry Diamond and Richard Gunther, 327–343. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001.

- Bengtsson, Åsa, and Hanna Wass. “Styles of Political Representation: What do Voters Expect?.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 20, no. 1 (2010): 55–81. doi: 10.1080/17457280903450724

- Blühdorn, Ingolfur. Simulative Demokratie: neue Politik nach der postdemokratischen Wende. Berlin: Suhrkamp Verlag, 2013.

- Butler, Daniel M., and Eleanor Neff Powell. “Understanding the Party Brand: Experimental Evidence on the Role of Valence.” The Journal of Politics 76, no. 2 (2014): 492–505. doi: 10.1017/S0022381613001436

- Carman, Christopher Jan. “Public Preferences for Parliamentary Representation in the UK: An Overlooked Link?.” Political Studies 54, no. 1 (2006): 103–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2006.00568.x

- Dahl, R. A. Polyarchy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1971.

- Dahl, R. A. On Democracy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020.

- Deschouwer, Kris. “Pinball Wizards. Political Parties and Democratic Representation in the Changing Institutional Architecture of European Politics.” In Political Parties and Political Systems, edited by Andrea Römmele, David M. Farrell, and Piero Ignazi, 83–100. London: Praeger, 2005.

- Diamond, Larry. Developing democracy: Toward consolidation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999.

- Dommett, Katharine. “Roadblocks to Interactive Digital Adoption? Elite Perspectives of Party Practices in the United Kingdom.” Party Politics 26 no. 2 (2020): 165–175.

- Dommett, Katharine, and Luke Temple. “The Expert Cure? Exploring the Restorative Potential of Expertise for Public Satisfaction with Parties.” Political Studies 68, no. 2 (2020): 332–349. doi: 10.1177/0032321719844122

- Easton, David. “A Re-Assessment of the Concept of Political Support.” British Journal of Political Science 5, no. 4 (1975): 435–457. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400008309

- Feld, Lars P., and Gebhard Kirchgässner. “On the Economic Efficiency of Direct Democracy.” In Direct Democracy in Europe, edited by Pállinger, Z. T., Kaufmann, B., Marxer, W., Schiller, T. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2007.

- Ferrín, Mónica, and Hanspeter Kriesi. “An Empirical Assessment of Satisfaction with Democracy.” In How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy, edited by Monica Ferrin and Hanspeter Kriesi, 283–306. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Goodwin, Jeff, James Jasper, and Francesca Polletta. “The Return of the Repressed: The Fall and Rise of Emotions in Social Movement Theory.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 5, no. 1 (2000): 65–83. doi: 10.17813/maiq.5.1.74u39102m107g748

- Grasso, Maria T., and Marco Giugni. “Protest Participation and Economic Crisis: The Conditioning Role of Political Opportunities.” European Journal of Political Research 55, no. 4 (2016): 663–680. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12153

- Grasso, Maria T., Barbara Yoxon, Sotirios Karampampas, and Luke Temple. “Relative Deprivation and Inequalities in Social and Political Activism.” Acta Politica 54, no. 3 (2019): 398–429. doi: 10.1057/s41269-017-0072-y

- Green, Jane, and Will Jennings. The Politics of Competence: Parties, Public Opinion and Voters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer. “A Giant Fast Asleep? Party Incentives and the Politicisation of European Integration.” Political Studies 60, no. 1 (2012): 115–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00895.x

- Heinisch, Reinhard, and Carsten Wegscheider. “Disentangling how Populism and Radical Host Ideologies Shape Citizens’ Conceptions of Democratic Decision-Making.” Politics and Governance 8, no. 3 (2020): 32–44. doi: 10.17645/pag.v8i3.2915

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. “Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage.” Journal of European Public Policy 25, no. 1 (2018): 109–135. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279

- Immerzeel, Tim, and Mark Pickup. “Populist Radical Right Parties Mobilizing ‘the People’? The Role of Populist Radical Right Success in Voter Turnout.” Electoral Studies 40 (2015): 347–360. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2015.10.007

- Inglehart, Ronald. “How Solid is Mass Support for Democracy—and how Can we Measure it?” Political Science and Politics 36, no. 1 (2003): 51–57. doi: 10.1017/S1049096503001689

- Katz, Richard S., and Peter Mair. “The Cartel Party Thesis: A Restatement.” Perspectives on Politics 7, no. 4 (2009): 753–766. doi: 10.1017/S1537592709991782

- Koch, Cédric M., Carlos Meléndez, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. “Mainstream Voters, non-Voters and Populist Voters: What Sets Them Apart?” Political Studies (2021). doi:10.1177/00323217211049298.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter. “The Implications of the Euro Crisis for Democracy.” Journal of European Public Policy 25, no. 1 (2018): 59–82. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2017.1310277

- Kriesi, Hanspeter. “The Transformation of Cleavage Politics The 1997 Stein Rokkan Lecture.” European Journal of Political Research 33, no. 2 (1998): 165–185.

- Lawson, Kay. Political Parties and Linkage: A Comparative Perspective. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1980.

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. Political Man: The Social Bases of Politics. New York: Anchor Books, 1963.

- Mair, Peter. “Representative versus Responsible Government.” Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, MPIfG Working Paper, August, 2009. Accessed January 24, 2021. http://www.mpifg.de/pu/workpap/wp09-8.pdf

- Marien, Sofie, Marc Hooghe, and Ellen Quintelier. “Inequalities in Non-Institutionalised Forms of Political Participation: A Multi-Level Analysis of 25 Countries.” Political Studies 58, no. 1 (2010): 187–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2009.00801.x

- Matthiess, Theres. “Retrospective Pledge Voting: A Comparative Study of the Electoral Consequences of Government Parties’ Pledge Fulfilment.” European Journal of Political Research 59, no. 4 (2020): 774–796. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12377

- McAdam, Doug. “Social Movement Theory and the Prospects for Climate Change Activism in the United States.” Annual Review of Political Science 20, no. 1 (2017): 189–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev-polisci-052615-025801

- Morlino, Leonardo. “Crisis of Parties and Change of Party System in Italy.” Party Politics 2, no. 1 (1996): 5-30. doi: 10.1177/1354068896002001001

- Noam, Eli M. “The Efficiency of Direct Democracy.” Journal of Political Economy 88, no. 4 (1980): 803–810. doi: 10.1086/260903

- Norris, Pippa. Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Norris, Pippa, Is Western Democracy Backsliding? Diagnosing the Risks (March 7, 2017). Forthcoming, The Journal of Democracy, April 2017, HKS Working Paper No. RWP17-012.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Pasquino, Gianfranco. “ITaly: The Triumph of Personalist Parties” Politics & Policy 42, no. 4 (2014): 548–566. doi: 10.1111/polp.12079

- Pedersen, Karina, and Jo Saglie. “New Technology in Ageing Parties: Internet use in Danish and Norwegian Parties.” Party Politics 11, no. 3 (2005): 359–377. doi: 10.1177/1354068805051782

- Rooduijn, Matthijs, Wouter Van Der Brug, and Sarah L. De Lange. “Expressing or Fuelling Discontent? The Relationship Between Populist Voting and Political Discontent.” Electoral Studies 43 (2016): 32-40. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2016.04.006

- Schattschneider, Elmer Eric. Party Government. New Brunswick: Transaction, 2004. (originally published in 1942).

- Schumpeter, Joseph A. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. New York: Harper, 1950.

- Spruyt, Bram, Gil Keppens, and Filip Van Droogenbroeck. “Who Supports Populism and What Attracts People to It?” Political Research Quarterly 69, no. 2 (2016): 335–346. doi: 10.1177/1065912916639138

- Stokes, Donald. “Valence Politics.” In Electoral Politics, edited by Dennis Kavanagh, 141–164. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992.

- Strom, Kaare. “A Behavioral Theory of Competitive Political Parties.” American Journal of Political Science 34, no. 2 (1990): 565–598. doi: 10.2307/2111461

- Tilley, James, and Sara B. Hobolt. “Is the Government to Blame? An Experimental Test of how Partisanship Shapes Perceptions of Performance and Responsibility.” The Journal of Politics 73, no. 2 (2011): 316–330. doi: 10.1017/S0022381611000168

- Van Biezen, Ingrid, Peter Mair, and Thomas Poguntke. “Going, Going, … Gone? The Decline of Party Membership in Contemporary Europe” European Journal of Political Research 51, no. 1 (2012): 24–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2011.01995.x

- van der Meer, Tom W. G., and Erik J. Van Ingen. “Schools of Democracy? Disentangling the Relationship between Civic Participation and Political Action in 17 European Countries.” European Journal of Political Research 48, no. 2 (2009): 281–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00836.x

- van Ham, Carolien, Jacques J. A. Thomassen, Kees Aarts, and Rudy B. Andeweg, eds. Myth and Reality of the Legitimacy Crisis: Explaining Trends and Cross-National Differences in Established Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Van Hauwaert, Steven M., and Stijn Van Kessel. “Beyond Protest and Discontent: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effect of Populist Attitudes and Issue Positions on Populist Party Support.” European Journal of Political Research 57, no. 1 (2018): 68–92. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12216

- Wagschal, Uwe. “Direct Democracy and Public Policymaking.” Journal of Public Policy 17, no. 2 (1997): 223–245. doi: 10.1017/S0143814X0000355X

- Werner, Annika. “What Voters Want from Their Parties: Testing the Promise-Keeping Assumption.” Electoral Studies 57 (2019a): 186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2018.12.006

- Werner, Annika. “Voters’ Preferences for Party Representation: Promise-Keeping, Responsiveness to Public Opinion or Enacting the Common Good.” International Political Science Review 40, no. 4 (2019b): 486–501. doi: 10.1177/0192512118787430

- Zaslove, Andrej, Bram Geurkink, Kristof Jacobs, and Agnes Akkerman. “Power to the People? Populism, Democracy, and Political Participation: A Citizen's Perspective.” West European Politics 44, no. 4 (2021): 727–751. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2020.1776490