ABSTRACT

This article critically examines the cultural backlash theory proposed by Norris and Inglehart [Cultural Backlash] to explain the rise of authoritarian populism in the US and Europe. While the theory emphasizes the conservative mobilization against progressive values, we argue that the success of authoritarian populism in Europe cannot be attributed solely to a cultural backlash. We contend that different European countries have unique historical contexts and older, unresolved conflicts are pivotal to understand the rise of authoritarian populist parties in the European context. By employing EVS-data from 2017–18, we analyse case studies from Hungary, Italy, Norway, and Poland. Challenging the “one-size-fits-all” approach, our study demonstrates that older cleavages are essential to understand the success of these parties and highlights the need to consider different variables and unresolved conflicts within specific national contexts when explaining the success of authoritarian populism in Europe.

Introduction

In the US and Europe, the growing “authoritarian populism” is linked to what Norris and InglehartFootnote1 have named the “cultural backlash”: a conservative and religious mobilization in favour of traditional values, and an “authoritarian reflex” against everything foreign, enhanced by economic insecurity and increasing inequality. While the backlash-model works well to explain the social forces that brought Donald Trump to power, we argue that it is not the only road to the success of authoritarian populism in Europe.

We argue that the “cultural shift” from social conservative-religious values to secular-liberal values may have reached a “tipping-point” in the US, but that the situation across Europe is more complex. Rather than adopting a “one size fits all” approach, we hold that in different European countries different factors and unresolved conflicts are nourishing the success of authoritarian populist, for instance those linked to the nation-building process. In Eastern and Central Europe, old authoritarian, and nationalist movements, suppressed during the communist period, have re-emerged after the brief interlude of westernization.Footnote2 In Northern and Western Europe, on the other hand, the process of secularization and democracy has moved past the tipping-point. Secular and liberal values are dominant, but the populist parties are still thriving. Their original rhetorical mix of anti-tax and anti-immigrant attitudes, seems sufficient to attract numerous voters.

Based on data from the European Value Study of 2017–2018, our study adds to our understanding of authoritarian populist voters by focusing on the resurgence of old political conflicts. We believe it is essential to focus on and distinguish between authoritarianism, nationalism, social conservatism, and religiosity, because these belief-systems and values have different historical roots, and their relevance today depends on the national political context. By using Hungary, Poland, Italy, and Norway as test-cases, we find that the governing party in Hungary, cultivate the image of past national grandeur and seeks revenge for the lost territories. In Poland, the Catholic Church is a mayor political player, with a firm grip on civil society and a de facto right to veto in many political issues. In Norway authoritarian populism thrives, despite the waning support for authoritarianism, social conservatism, and religious beliefs.

Of the four cases we discuss, only one (Italy) seems to fit the backlash theory well. Resistance to value-change is not sufficient to explain the support for these parties indiscriminately: the motives to support authoritarian populists are diverse and context-related.

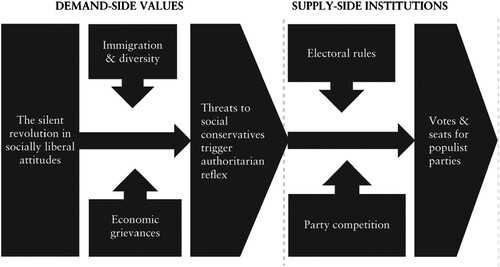

The cultural backlash-argument

The cultural backlash thesis holds that the growing support for “authoritarian populism” in America and Europe is the consequence of a conservative reaction in defence of traditional values, caused by the spread of progressive values, and enhanced by an “authoritarian reflex”, enhanced by economic insecurity, and increasing immigration.Footnote3 Older cohorts and the less educated support traditional values, and consequently authoritarian populism, while younger cohorts tend to support more progressive values. As the generational aspect of the theory and its criticalities have been addressed by Schäfer,Footnote4 we reflect on the demand-side values perspective of the theory ().

Figure 1. Theoretical framework of the cultural backlash theory (Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash, 33).

Inglehart argued that the steady economic growth and peace created a “silent revolution” from materialist values to post-materialism in Western Europe, as new generations raised under favourable conditions replaced older generations marked by poverty and war.Footnote5 Later, he focused on “survival-values”: support for traditional family values like woman’s responsibility for children, the rejection of sexual minorities, etc. He showed how support for survival-values declined after World War II and that support for self-expression values increased in Western countries.

According to the cultural-backlash-hypothesis, the values shift has now reached a “tipping-point” where the supporters of traditional values fear that they are about to lose their cultural hegemony.Footnote6 When the “tipping-point” is reached, social conservatives feel threatened, and they mobilize politically in favour of authoritarian populist parties and candidates.

Norris and Inglehart explain authoritarianism both as a value with three components – conformity, aggression towards outsiders, loyalty to the in-groupFootnote7 – and as an “authoritarian reflex”: an inborn, psychological mechanism formed through evolution to cope with insecurity and external threat.Footnote8

Immigration, economic vulnerability, insecurity, and relative deprivation are described as “triggers” unleashing the authoritarian reflex. The “Reagan/Thatcher-revolution” in the 1980s, the “knowledge society” and the financial crisis have created widespread insecurity and increased relative deprivation.Footnote9

Further, the presence of minorities and immigration pose a threat, unleashing the authoritarian reflex, reversing the causal direction of the well-established link between authoritarianism and hostility towards minorities.Footnote10

Our argument and case selection

The Backlash-theory presents a unidimensional timeline with people with new values “silently” replacing older generations with authoritarian and traditional values.Footnote11 The conflict has reached a “tipping point”, with the supporters of the once hegemonic traditional values making a last stance against the forces of change. In this sense, the theory implies that the same causes explain authoritarian populism across contexts.

We, however, theorize that (I) the European context is much more diversified and that the support for authoritarian populism has diverse roots; and (II) that the tipping-point timeline is at different stages in different European countries.

On the former, we hold that some of the most successful authoritarian-populist parties in Europe feed on much older political conflicts, for instance those linked to the nation-building process, or, with reference to Central and Eastern Europe, the effects of communist rule. The democratic political culture is still in its infancy in many East and Central countries, and some parties and their followers revert to the authoritarian policies of the interwar period, such as aggressive nationalism.Footnote12 The communist regimes sought to suppress and control civil society, including the churches. In the end, the communist ended up strengthening the churches, as symbols of resistance in many countriesFootnote13 and made them a formidable political force in the post-communist years. The communist regimes were, at least in theory, in favour of gender equality: women got access to e.g. contraceptives, the legal right to abortion, divorce. Today, some authoritarian populist parties fight to remove these rights, and they succeed because the progressive forces are weak, not strong.

This latter point brings the attention on the second part of our argument, holding that the values-change timeline is at different stages in different European countries. While some countries still have to reach the tipping-point situation, others are beyond. On this notice, we suggest that authoritarian populist parties survive the “tipping point”, as some of them have adapted and thrive in countries dominated by secular and liberal values.

Before addressing the case selection strategy and its details, it is important to note that this study employs a mixed method research design: we combine in-depth investigation of case study with statistical analyses. As in Renske and Kopecký,Footnote14 this method is particularly suitable when the results of the large-N studies (in this case represented by the cultural backlash theory) are not entirely satisfactory, and the goal of the case study approach is to build a better explanatory model.Footnote15

Case studies have been shown to be particularly effective when integrated with statistical regression and comparative approaches,Footnote16 allowing researchers to determine whether patterns or results from regression analyses align with case study findings. Consistency between the two methods can strengthen causal explanations. Conversely, if inconsistencies highlight areas for refining statistical models or adjusting variables based on case study insights, ensuring a more accurate explanatory model.

On the methodological justification for the choice of case studies, we employ what Seawright and GerringFootnote17 define as diverse case method. Resembling Mill’sFootnote18 method of agreement and difference and Przeworski and Teune’sFootnote19 most different systems approach, the diverse case method has as its primary objective the achievement of maximum variance along relevant dimensions. This diversity is aimed at representing the full range of values characterizing X, Y, or some particular X/Y relationship,Footnote20 as well as identifying the various causal paths that can lead to a particular outcome. As in the purpose of the current study, the diverse case method is suitable for those cases when different independent variables all cause the outcome, but they might do so independently of each other and in different ways.

Following this argument, the selection of countries (Hungary, Italy, Norway, and Poland) reflects a deliberate attempt to encompass a wide array of political, social, and economic contexts, thus providing a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon. The goal of this study is not to identify typical or extreme cases, but rather to illustrate the diversity and multiple pathways through which authoritarian populist parties can achieve success across different European settings.

Therefore, we have chosen Hungary, Italy, Norway, and Poland as test-cases. The following criteria explain our country choice: first, the countries display a different history of authoritarian and democratic rule, the role of Church and religion in society, their experience of ethnic diversity and migration. They differ in the average standard of living and economic inequality, and when it comes to the support for traditional versus secular values.Footnote21 Despite the focus on “democratic backsliding”, Hungary and Poland are not extreme cases in post-communist Europe. Both entered NATO and the EU soon after the regime-change; unlike many eastern neighbours, they have at least some, albeit brief, historic experience with democratic rule. Finally, they all have successful “authoritarian populist” parties as categorized by Norris and Inglehart. The selection of countries does not have the objective to disprove the theory, but rather to uncover the range of significant additional variables of equal importance in the European context.

In the following sections we reflect on the key elements of the cultural-backlash theory. We focus on religion and social conservatism, authoritarianism, nationalism and migration, economic hardship. These belief systems have different historical roots: as argued by Harteveld et al.Footnote22, the specific social and economic conditions that citizens experience have an influence on the strength and relevance of their attitudes, also in the context of political behaviour. Through the four test-cases, we show how different forces and factors are at work in the various European countries and why the cultural backlash theory might not be working to explain authoritarian populism indiscriminately in Europe.

Religion and social conservatism

Religion and social conservatism are at the core of the cultural-backlash theory. Norris and Inglehart argue that the driving force of the cultural-backlash is the political mobilization of social conservatives in defence of traditional values, driven by the fear that they are becoming a minority and lose cultural hegemony.Footnote23

Alternatively, we highlight how the political mobilization of these forces in European countries is at very different stages and the support for authoritarian populists cannot be universally attributed to the reaction of social conservatives. We expect the impact of religious faith and social conservatism on the support for authoritarian populism to be stronger in countries where these forces are still in a hegemonic position than in countries close to, or beyond, the “tipping-point”.

The Polish case exemplifies the hegemonic position of social-conservative forces. The “tipping-point” metaphor evokes an image of historic drama; the last faithful making their final stance against the ungodly. But in Poland the Catholic Church is acting from a position of strength, not weakness. The Church’s dominant position does not encounter much internal resistance. The Law and Justice party (PiS) must point outwards, to the EU, to identify a credible secular threat. Rather than a defensive political struggle, the Catholic Church is on the offensive.

In Hungary the Catholic Church has a less dominant position than in Poland.Footnote24 Although Fidesz emphasizes Christian values in the party’s platform, the party’s support for IVF and a series of recent sex-scandals involving prominent party-members suggest a relaxed commitment to Christian values. Their appeal to traditional forces does not seem to stand on solid ground.

The Italian case resembles the metaphor of the “tipping-point”. Religiosity and church attendance have been steadily declining since the 1970s, with an acceleration during 2008–2018. Simultaneously, public opinion rapidly shifted on topics at the core of a potential conflict between religious-conservative forces and liberal-secular ones. LGBT+ rights, for example, gained visibility and overall high levels of tolerance among Italians.Footnote25

Norway on the contrary has been beyond the “tipping-point” for some time.Footnote26 Norwegians are among the least religious people in Europe; the Church of Norway has lost much of its authority and was legally separated from the state in 2017. If there ever was “a tipping-point” or a confrontation between religious, social-conservative forces versus secular-liberal ones, it must be the struggle over the right to abortion in the 1970s.

The four test-cases display profound differences in their experience with conservative and religious forces. Except perhaps the Italian case, none of them seem to resemble the end game described in the cultural-backlash theory, that explains the mobilization of authoritarian populism.

Authoritarian and democratic heritages

In the cultural-backlash, authoritarian populism is conceived as a combination of populism with authoritarianism, where authoritarianism is defined as a cluster of values prioritizing collective security for the group at the expense of liberal autonomy of the individual.

European countries, however, have different experiences with democratic and authoritarian rule. The authoritarian populist parties in Western Europe challenge the political establishment, the elite, but open support for non-democratic rule is almost absent. On the contrary, the “democratic backslide” in some Central and East European countries reflects their non-democratic past. A deep-rooted democratic political culture never had time to fasten and unsolved issues from their past have returned to the political agenda. It takes time to develop a democratic political culture. Of the analysed countries, Poland and Hungary had little to build upon. After the transition period (1989–2004, culminating in their admission to the European Union), the pattern of political conflict may have gravitated back to old themes: nationalism, religion, and social conservatism. The centre-left governments did not deliver the rise in living standard and effective welfare-benefits many had hoped for, and many voters turned to right-wing parties.

Poland’s experience with democracy was overall limited. The idea of party-competition was unfamiliar to many Poles in 1990, and political parties themselves have made little effort to educate people on the functioning of democracy.Footnote27

Similarly in Hungary, the overall experience with democracy was rather limited before the break away from communism. We agree with Bozóki and SimonFootnote28 when they argue that:

(…) democratic traditions have few roots in Hungary. Thus, it is not the democratic backsliding that represents an exception to the rule, but the twenty years of democracy that existed after 1989. What we have been witnessing since 2010 is simply the re-emergence of a long-term historical pattern of authoritarianism.

To add to this variety, in Italy the process of democratization has been bumpy; after unification in 1861 it came to a halt with the Fascist march on Rome-coup in 1922. The post-war period was marked by political tensions, violence, instability, and culminated with the dismantling of the party system for corruption. Rose and ShinFootnote30 have characterized Italy as an “incomplete democracy” during this period: democratic institution on top of an inefficient and corrupt state apparatus. While the League’s roots are independent of neo-fascist legacies, Brothers of Italy descends from National Alliance, the neo-Fascist party which, nevertheless, embraced liberal democracy.

The diverse histories of authoritarian and democratic rule that characterize the European context, make it hard to assume that the roots and the extent to which these parties benefit from the democratic (or not) past can be put on the same level.

Nationalism and migration

Norris and InglehartFootnote31 argue that authoritarian values lead people to emphasize group solidarity and to reject outsiders. Authoritarians tend to be intolerant of outgroups, uniform in their hostility towards immigration, along with nationalism and nativism, xenophobia, cultural protectionism.

The expansion of the EU/EEA common labour market has led to increased mobility, mainly from the east to the west.Footnote32 Poland and Hungary had very little experience with immigration under Soviet control, and after 1990 emigration has been more common than immigration. The hostility towards immigrants and minorities in these countries can hardly be explained by the experience of immigrants displacing natives, as theorized in the cultural-backlash thesis. Alternatively, we suggest that it must be the symbolic threat, the fear of changes that immigration might cause in the future, that drives this hostility: aggressive nationalism tends to exploit the fear of foreigners by exaggerating the “threat”.

This seems to be the case of Hungary.Footnote33 Orbán’s support for nativism is rooted in a more than 100 years-old conflict regarding the annexation of ethnic Hungarian lands in the wake of World War One. Under Fidesz, the heavy-handed assimilation of minorities into the Hungarian nation has been resumed, together with the re-emergence of the violence and opposition to Romani, the largest minority in Hungary.Footnote34 During the refugee-crisis in 2015–16, Hungary closed its borders, despite most of the refuges were heading for Western Europe. Grajczjár et al.Footnote35 argue that Fidesz wanted to convince voters that only it can save the Hungarian nation from the enemy, immigrants.

Similarly, despite Poland’s EU-membership opened the possibility of immigration, the PiS-government has opposed receiving refugees and it has been accused of playing on anti-Muslim sentiments.

In contrast, Italy and Norway did experience influxes of immigrants. The fall of the Berlin-wall and the proximity to North Africa significantly changed the composition of Italy’s foreign population. This allowed authoritarian populists to target immigration in cultural, security, and “ethnic-substitution” terms.

Also Norway was unprepared when asylum-seekers started arriving in the 1980s. Immigration soon became a major political issue and the most divisive one in every national election.Footnote36 During the refugee-crisis in 2015–16, only Germany and Sweden received more asylum seekers per capita than Norway, with the asylum-seekers from Muslim-countries drawing the most political attention.Footnote37

Anti-immigrant policies may be the only thing authoritarian populist parties have in common.Footnote38 But, again, the roots of these attitudes are diverse. Countries such as Italy and Norway have experienced a significant influx of immigrants, whereas many countries in Eastern and Central Europe face emigration – not immigration. The hostility against “the outsiders” in these countries must have other roots and cannot be attributed to the presence of immigrants in the countries.

Economic hardship and authoritarian reflex

Norris and InglehartFootnote39 state that economic insecurity is likely to trigger the authoritarian reflex; authoritarianism and populist values are stronger among less prosperous people, such as working class, lower income households. Through our test-cases we uncover important dissimilarities within the European context that might help us understand the different role that economic insecurity has to the success of authoritarian populist parties.

On one side, the Hungarian economy was in shambles after the turn to a market economy and the industrial base stood no chance on the world-market.Footnote40 The support for the transition to capitalism fell as well as the support for the change to a multiparty system.Footnote41 This is the context in which the Social Democratic Party (MSZP) lost the 2010-election to Fidesz: after years of austerity-policy and a political scandal over mismanagement of the economy.Footnote42

Differently, the economic growth in Poland was above the EU-average in the years leading up to the electionFootnote43 and income inequality had been reduced since 2005 (OECD). The electoral victory of PiS over the liberal Civic Platform in 2015 was not the result of an economic downturn.

Among the test-cases, Italy has the highest level of income-inequality, which increased between 2008 and 2017 (OECD). Wages close to the EU-average (Eurostat), make the labour-market attractive for workers from poorer EU-countries. However, immigrants in the labour-market mainly provide a workforce in sectors that are no longer attractive to Italians for wages and social status, such as manual labour, unskilled or semi-skilled jobs. Except for low-skill jobs, it seems difficult to attribute the aversion towards immigrant to job competition.

According to the OECD, income inequality in Norway has increased over the last decade but remains among the lowest in Western Europe. During the financial crises in 2006–2007, the Progress Party lost popular supportFootnote44 as it was unable to put the blame on the immigrants. It is hard to find a strong link between economic fluctuations and hostility towards immigrants in Norway. The number of Norwegians expressing negative attitudes is rather stable, irrespective of the ups and downs in the economy.

Public opinion in Norway seems sensitive to sharp rises in immigration. The second breakthrough of the Progress Party in 1987 came after the exponential growth of asylum-seekers in the mid-1980s.Footnote45 According to opinion polls, the Progress Party gained around 4,5% in popular support during the refugee-crisis in 2015–16, but its support dropped just four months later.Footnote46 This may be an example of what Norris and InglehartFootnote47 call “authoritarian reflex”, an immediate response to a perceived threat. Simultaneously, this illustrates why cross-national surveys are unsuited to test the authoritarian reflex-hypotheses: most surveys record authoritarian values, stable beliefs about how power and authority should be distributed in society.

Expectations

Authoritarians tend to see men as superior to women, the ethnic majority as superior to immigrants, etc., but moral conservatism, and nativism are independent belief-systems, with distinct historic roots. We define authoritarianism as the belief that hierarchical power structures are natural and desirable, a value with political connotations. If we were to merge all of these into one super-dimension we would risk overlooking significant differences in cultural context among countries.

Based on the described contextual differences, we expect the following individual-level attitudes to predict support for authoritarian-populist parties in each country:

Anti-immigrant attitudes seem the common denominator for supporters of authoritarian populist parties.Footnote48 As neither the presence of large numbers of immigrants nor economic hardship are essential for the rise of anti-immigrant sentiments, we expect a significant effect in all countries.

We expect authoritarianism to be more common in the countries with the most recent experience with non-democratic rule, Poland, and Hungary, and least common in the country with the longest democratic tradition, Norway. However, we expect the likelihood of authoritarians supporting authoritarian populist parties to be similar across countries.

Perceived threats to the national identity play a key role in Hungary and explains the support for the right-wing populists to a larger extent than in Poland, Italy, and Norway.

Social conservatism is linked to religiosity but may also play an independent role. In Poland social conservatism signified resistance to the communist states attempts to transform society. PiS stands in this tradition. Abortion, gay-rights, and divorce may be seen as threats both to traditions and to religion, creating an independent factor promoting social conservatism.

Religion is expected to explain the support for authoritarian populists to a larger extent in Poland than in Hungary and Italy – not because the Christian-conservatives are making a last stand against secularism, but because of the hegemonic position of the Catholic Church. Italy is probably the case closest to a tipping-point-situation. We expect no effect of religiosity in Norway.

We do not expect authoritarianism to be strongly associated with income, education, or other indicators of economic well-being.

These expectations, if met, would make the cultural-backlash theory unfitting in its attempt to explain authoritarian populism across cases. They would, however, suggest that more than a common explanation to authoritarian populism we might have different pathways in each context.

Data and method

This study relies on the European Values Study data of 2017. The EVS is a large-scale cross-national survey covering topics on family, religion, politics, and society, thus fitting with the purpose of this study. The countries in our sample are Hungary, Italy, Norway, and Poland.

Dependent variable

This study differs empirically from Norris and Inglehart:Footnote49 they run two separate OLS regressions with the populism-scale of party position (measured through respondents trust in politics) and the authoritarianism-scale of party position (measured through social-conservative attitudes) as dependent variables. Our dependent variable is the preference for authoritarian populist parties, which is based on the recoded variable asking Which (political) party appeals to you most?.

Through our models, we do not directly investigate the tipping-point argument. While building on the main theoretical arguments of the cultural backlash theory, this article does not empirically replicate it (for a closer replication see SchäferFootnote50). Rather, we investigate the theorized different effects that the drivers might have to explain the support for authoritarian populism in different contexts, as discussed in the previous section. The operationalization of authoritarian populist parties relies on the distinction originally made by Norris and Inglehart.Footnote51 While not necessarily agreeing with such definition, for the purpose of this study we decided to keep their classification. shows the parties denoted as authoritarian populist and citizens expressed preference.

Table 1. Authoritarian populist parties and shares in voters’ preference.

Independent variables

The details on variables wordings and reliability coefficients are available in the supplementary material. As the meaning of some of the attitudinal predictors may vary across countries, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated both for the whole sample and for each individual country. The variables have been recorded so that a higher score represents stronger support for the various attitudes. We controlled for collinearity between the variables using the Variance Inflation Factor. All VIF values are below the threshold level.

Cultural backlash

Anti-immigrant attitudes are measured on a scale of five items, asking respondents to “evaluate the impact of these people on the development of [your] country”, if immigrants “take jobs away”, “make crime problems worse”, or “are a strain on a country’s welfare system” and if “it is better if immigrants maintain their distinct customs and traditions”. Nationalism is operationalized with five questions asking how important it is to share the nation’s ancestry, to have been born in the country, to speak the language and share the national culture, to be truly a citizen, how proud one is to be the country’s citizen.

Previous studies measuring authoritarian values mainly adopted the Altemeyer’s Right-Wing authoritarianism scale (RWA). However, the RWA scale does not allow one to measure authoritarian predispositions without simultaneously measuring other political attitudes that authoritarianism is theorized to predict.Footnote52 Disentangling the effects of social conservatism and authoritarianism is important when testing the cultural-backlash theory.

We thus preferred to keep the measurement of these two attitudes separate. This choice differs from Norris and Inglehart decision to measure authoritarianism through social-conservative attitudes. We measure citizens’ support for authoritarian values with two items asking whether “greater respect for authority is a good or a bad change in our way of life” and whether “having a strong leader who does not have to bother with parliament and elections” is a good or bad way of governing the country. We acknowledge the limitations of this variable: while several alternative indexes have been tested, none of them were valid and reliable across countries.

Social conservatism is operationalized by a scale of five items measuring the level of agreement on whether homosexuality, abortion, divorce, having casual sex, and IVF can be always, never or sometimes justified.

The scales on anti-immigrant attitudes, authoritarianism, nationalism, social conservatism, and religiosity have been standardized and coded with a minimum value of 0 and a maximum of 1.

Trust

Populist parties tend to be overtly anti-elitist in nature; they criticize institutions such as political parties, organizations, and bureaucracies. Where international organizations are concerned, populists often argue that national elites are prioritizing the interest of the EU and international organizations over the interests of the country and its people.Footnote53

We therefore measure the level of trust in national institutions (justice system, police, social security, civil service, education system) and supranational institutions (EU, UN). As when the data were collected populist parties were holding government positions in Hungary, Poland, and Norway, we expect higher levels of trust in national institution in these countries.

Economic deprivation

Economic deprivation was measured with the variables “unemployed” and “social security”, measuring whether the respondents experienced unemployment for more than three months in the past five years and/or the dependence on social security benefits during the last five years. Objective financial deprivation was measured with the variable income. As the number of missing values of the income variable was high, they have been assigned the average income per country.Footnote54 It would have been ideal to have measured the respondents’ perceived economic deprivation; also, the questions on unemployment and social security might be less precise as they cover a rather long period. Educational level is measured using the International Standard Classification of Education, ranking from 0 to 8. We included age and gender as control variables.

Results

shows the descriptive statistics for each country. As expected, people on average are more religious in Poland and Italy than in Norway, with Hungary in-between. Nationalist sentiments are more widespread in Poland and Hungary and less in Italy and Norway. On social conservatism, Polish respondents are those scoring higher, followed by Hungarians, Italians, and Norwegians. Respondents in Hungary and Italy show a higher degree of anti-immigrant sentiments, but the mean values in Poland and Norway are only slightly lower. Italy, Poland, and Hungary score higher on authoritarianism, while Norway has the lowest mean. Overall, Norway stands out as it has the lowest mean values on all the cultural backlash-related explanatory variables. Hungary and Poland show the highest mean scores on these variables, with Italy being somewhat in the middle between the Norwegian case and the Hungarian and Polish ones.

Table 2. Descriptivestatistics.

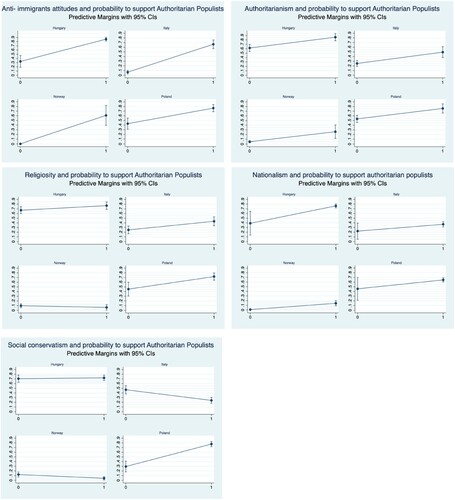

We conducted logistic regressions with the preference for authoritarian populist parties as the dependent variable. presents the results. What stands out are the differences, not only in terms of significant effects, but also in the direction of the relationships of some key explanatory factors across countries.

Table 3. Logistic regressions per analysed country.

Unlike the other predictors, anti-immigrant attitudes and authoritarianism stand out as consistently related to the preference for authoritarian populist parties, constituting the common core of support for these parties across countries. Nationalism represents a significant explanatory variable in Hungary and Norway, while it displays insignificant effects in Italy and Poland. As expected, social conservatism is positively related to the preference for authoritarian populists in Poland, while this relationship is negative in Norway. Interestingly, social conservatism is negatively related to the support for authoritarian populists also in Italy. Due to the prominent role played by the Catholic Church we would have expected results similar to the Polish ones. Social conservatism did not have a significant effect in Hungary. Religiosity constitutes a significant and positive predictor only in Italy and Poland, while it is insignificant in Norway and Hungary.

Also based on the analysis of the marginal effects as in the supplementary materials, in Hungary the explanatory factor having the greater impact on the probability to prefer authoritarian populist parties is anti-immigrant attitudes, followed by nationalism and authoritarianism respectively, while social-conservatism and religiosity are insignificant factors. In the Polish case, the main driver for the predicted preference for authoritarian populism is social conservatism, followed by anti-immigrant attitudes, religiosity, and authoritarianism, while nationalism is not significant. In Italy anti-immigrant attitudes have the strongest impact on the preference for authoritarian populist parties, followed by authoritarianism and religiosity. As shows, while nationalism is not significant, social conservatism has a negative effect on the probability to support authoritarian populist parties.

As for the Norwegian case, the most important factor appears to be anti-immigrant attitudes, followed by nationalism and authoritarianism. Social conservatism is negatively correlated to the support for authoritarian populists, while the effect of religiosity is insignificant.

The variables on the socioeconomic indicators are for the most insignificant. While it might be argued that these insignificant results are explained by the strong main predictors such as anti-immigrant attitudes or authoritarianism, logistic regressions performed with only socioeconomic indicators (table A7) display mostly the same trend as in . To further assess the robustness of the results on socioeconomic indicators we ran a regression with authoritarian attitudes as the dependent variable (table A8). The results point to a consistent, significant, and negative effect of education and age in all the countries analysed. In this model, of the “cultural-related” variables, only social conservatism is consistently and positively associated with having authoritarian values in all the four countries; anti-immigrant attitudes have a positive effect only in Italy and Hungary.

To compare the effect of the results across countries we first show the post-estimation predictions of each variable across countries and secondly, we assess whether the differences are significant by adding an interaction term between the dummy variable for country and the relevant predictors. shows the average predicted probability per country of preferring authoritarian populist parties for different levels of anti-immigration attitudes, authoritarianism, nationalism, social conservatism, and religiosity. The estimates are based on the model presented in , with the other variables set at their mean values. In , Norway stands out as an outsider; while still being mostly significant, the effects of the predictors seem rather marginal. Differently, Hungary, Poland, and Italy show similar and clearer patterns across the different variables.

Figure 2. Predicted probability to support authoritarian populist parties at different levels of predictors.

Higher levels of anti-immigrant attitudes and authoritarianism lead to a higher level of support for authoritarian populist parties, with highlighting the differences of both slopes and intercepts. The other variables show more mixed results across the sample. As in , shows how the effect of social conservatism is negative in Italy and Norway, while it is positive in Poland and insignificant in Hungary. Higher levels of nationalist sentiments have a strong impact on the probability to support authoritarian populists in Hungary, whereas in Italy and Poland they display non-significant effects. The effect of increased level of nationalism has a positive effect also in Norway, but this is, however, rather marginal, especially when compared with Hungary. The predicted effect of an increase in the level of religiosity is positively correlated with support for authoritarian populists in Italy and Poland, with Poland registering a much higher impact of religiosity in comparison with Italy. Norway and Hungary report non-significant effects.

Overall, it seems that the change from a low to a high-level of anti-immigrant attitudes constitutes the factor having the strongest effect in increasing the probability to support authoritarian populist parties across countries: this result is consistent not only with the cultural backlash theory as developed by Norris and Inglehart,Footnote55 but also with the replication carried out by Schäfer.Footnote56 As anticipated, Norway displays overall minor effects on all the explanatory variables, while in Poland and Hungary the predictors seem to have the greatest impact.

To test whether these differences across countries are significant, we replicate the model as in with the addition of the interaction term between the dummy variable for country and the relevant predictors. Separate models have been conducted for each predictor (see supplementary materials).

The findings show that for anti-immigrants attitudes, the probability of supporting authoritarian populist parties is not the same for Hungary as for Norway: when having anti-immigrants attitudes, the probability is higher in Norway than in Hungary. The effects of holding nationalist sentiments on the preference for authoritarian populist parties is significantly lower in Italy than in Hungary, while it is higher in Norway. The comparison between Poland and Hungary did not yield any significant difference. The country differences on authoritarianism seem to be insignificant. When scoring higher on social conservatism, the probability of preferring an authoritarian populist party is higher for Poland than for Hungary, while it is lower in Italy when compared to Hungary. Similarly, the effect of religiosity is stronger in Poland than in Hungary, while being lower in Norway than in Hungary.

When having Poland as a reference category,Footnote57 the results confirm the expected significant differences on the effect of religiosity and social conservatism. The probability of supporting authoritarian populists is higher for Poles holding religious and social conservative attitudes, than it is for Hungarians, Italians, and Norwegians. The rest of the variables do not display significant group-differences, except for nationalism: the effects of holding nationalist sentiments is lower in Italy than in Poland, while it is higher in Norway compared to Poland.

Norway displays a higher probability of supporting authoritarian populists when holding anti-immigrant and nationalist sentiments than in the other countries. This is interesting as both the descriptive statistics in table and show how Norway is the country with the lowest level of nationalism and anti-immigrant attitudes and displays the lowest impact on the predicted probability. It might be argued that nationalism and anti-immigrant sentiments are not widespread in Norway, but among those holding these sentiments, the support for authoritarian populism is common.

This article does not focus on the generational differences as stated in the cultural-backlash theory, nevertheless, for completeness of the analysis, we test whether there are significant differences among cohorts, by performing regression models with interactions between the dummy variable for cohorts and the relevant predictors. The categorization of cohorts is the one adopted by Norris and Inglehart.Footnote58 The interactions are mostly non-significant; the few significant effects display how the effect of the predictors is stronger for younger generations than it is for older generations. While contradicting Norris and Inglehart,Footnote59 these results are in line with the replication by Schäfer.Footnote60 As some of the predictors might not be independent from one another, further regression models with interactions have been carried out and are available in the supplementary materials. The results are however mostly significant.

Discussion

Building on the cultural-backlash theory, this article offers an alternative to the “one size fit all” approach to the study of authoritarian populism, by displaying that there are different pathways to the support for authoritarian populism in the European context and that the tipping-point timeline is at different stages in different European countries.

Our results show how the cultural-backlash theory, as it is, explains the support for authoritarian populism in some but not all contexts. We show through four test-cases that the European context is much more varied and suggest that multicausal explanations are more suitable for the study of populism: each context is unique and the support for authoritarian populism has diverse roots. As argued, citizens’ belief systems and values such as authoritarianism, social conservatism, nationalism, and religiosity have different historical roots: they originate in specific socio-structural conditions that are context-dependent.Footnote61 Our analysis acknowledges how these differences in the political, economic, and historical backgrounds come into play when explaining the support for authoritarian populism.

As anticipated, beyond the differences we also identify the commonalities of authoritarian populist parties’ supporters, being the support for authoritarian and anti-immigrant sentiments. We consider these two elements to be the common core of authoritarian populism that transcends different contexts, and not the mobilization of social conservatives. However, we acknowledge, as argued, that the roots of these feelings are diverse: e.g. while Italy and Norway directly experience immigration, in Hungary and Poland the strength of anti-immigrants attitudes is probably due to the exploitation of the perceived threat of immigration.

Overall, the results add nuance to the understanding of far-right supporters by revealing important differences in social forces and underlying dynamics determining the support for these parties, that go beyond the cultural-backlash explanation.

In Poland, the support for right-wing populist parties is explained by social conservatism and religious values, meeting our expectations. As theorized, tradition and religion are important explanators of the support for PiS. It is, however, hard to interpret these results as a backlash against secularism due to the strong position of the Catholic Church. Rather, as argued, they point at the re-emergence of unresolved conflicts linked to the effects of communist rule.

In Norway the results display a quite different picture and, as theorized, do not point a conflict between conservative and liberal forces. Religiosity is insignificant, while social conservatism is negatively related to the preference for authoritarian populists. shows how Norway stands out in this comparison. While anti-immigrant sentiments and nationalism might have a strong effect in predicting party preference, they constitute a marginal phenomenon. Overall, the Norwegian results confirm how authoritarian populism can succeed also in societies dominated by more progressive values, limiting the relevance of the tipping-point and backlash arguments.

Nationalism is more widespread in Hungary than in the other countries and the effects of religiosity and social conservatism, at the core of the cultural backlash-thesis, are insignificant. As theorized, authoritarianism has the strongest predicted effect in Hungary and Poland, confirming how authoritarianism is more common among countries with a recent experience of non-democratic rule.

Italy’s results and the latest political developments of the country suggest that this case might fit the cultural-backlash theory. The negative correlation of social conservatism in predicting support for authoritarian populism and the positive effect of religion, might signal that Italy is on “the tipping-point” and that a cultural backlash is ongoing among the electorate. The country has recently seen a shift in public opinion on topics at the core of a potential conflict between religious-conservative forces and liberal-secular ones. Parallelly, however, these topics have become much more divisive, core political issues, while authoritarian populists have become more popular.

Another contribution comes from disentangling the effects of authoritarianism and social conservatism on the preference for authoritarian populists: In Italy and Norway, the support for social conservative values is not linked to support for authoritarian populist parties. These results align with Schäfer,Footnote62 assumption on how “It is less obvious, however, that citizens who oppose (some form of) migration also reject same-sex marriage, female emancipation or religious pluralism”. This constitutes a particularly important finding as the reaction of those advocating more conservative values is at the core of the success of authoritarian populism. Previous studiesFootnote63 tended to include social conservatism values in the measurement of authoritarianism, blending into one variable distinct belief systems, missing the opportunity to track the different roles that they play in explaining party preferences.

Having this in mind, two explanations can justify the negative correlations of social conservative views with support for authoritarian populists in Norway and Italy. The first is anchored in what OzzanoFootnote64 defines as

a dilemma between a model of party anchored to traditional Christian values, with a conservative orientation towards gender issues, sexual morality and personal rights; and another where Christianity mainly plays the role of an identity marker in the relation with other cultures, typically Muslims, and does not prevent the development of more open discourses on gender roles and individual rights.Footnote65

Our results are not consistent with the argument that sees authoritarian populism as rooted in economic deprivation. This is in line with previous studiesFootnote68 showing that far-right voters are not the “so-called socioeconomic losers of globalization”.

Conclusion

Formulating a theory requires finding the right balance between generalization and particularism, abstraction, and empirical facts, and between being all-encompassing and being parsimonious. This study reveals that there is no single model explaining the support for this class of parties: the countries analysed, and more generally the European political landscape, present different structural conditions, party backgrounds, and a diversified electorate. The drivers explaining the electorate’s motives to support authoritarian parties are diverse and reflect the different combinations of social forces acting in each country. Simultaneously, this study confirms how the supporters of different authoritarian populist parties have as a common denominator anti-immigrants and authoritarian attitudes and de-escalates the role of social conservatism values in determining the support for authoritarian populists. While recognizing the common elements of these parties, we should not overlook the differences among them, or the different contexts in which they operate.

Limitations

Disentangling the effect of social conservatism and authoritarianism came with a price in the measurement of the latter. Further studies should ideally adopt an alternative measurement for authoritarianism. Due to the lack of proper indicators in our dataset we were also unable to test the effect of perceived economic wellbeing.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (686.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Elena Baro

Elena Baro is a researcher at the department for Interdisciplinary Studies of Culture at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. She holds a PhD in Political Science from the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. Her research interests include populism, political behaviour, political psychology.

Anders Todal Jenssen

Anders Todal Jenssen is a Professor of Political Science at the Department of Sociology and Political Science at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. He has contributed to numerous books and published articles in international and Norwegian academic journals. His research focuses on political behavior, including electoral studies, political sociology and political psychology.

Notes

1 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash.

2 Nagle, “Ethnos, Demos and Democratization,” 28–56.

3 Norris and Inglehart. Cultural Backlash.

4 Schäfer, “Cultural Backlash?” 1–17.

5 Inglehart, “The Silent Revolution in Europe,” 991–1017; Inglehart, The Silent Revolution; Inglehart, “Post-materialism in an Environment of Insecurity,” 880–900.

6 Inglehart, Cultural Evolution; Norris and Inglehart. Cultural Backlash, 47.

7 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash, 71.

8 Inglehart, Cultural Evolution, 188.

9 Inglehart, Cultural Evolution, 191–199; Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash, 133.

10 Adorno et al. The Authoritarian Personality.

11 Norris and Inglehart. Cultural Backlash, 446.

12 Csehi, “Neither Episodic, Nor Destined to Failure?” 1011–1027.

13 Chu, “Unfinished Business,” 631–654.

14 Doorenspleet and Kopecký. “Against the Odds,” 697–713. p. 709.

15 Lieberman, “Nested Analysis as a Mixed-method Strategy for Comparative Research,” 435–452.

16 Moses and Knutsen, “Chapter 1. Introduction”.

17 Seawright and Gerring, “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research,” 294–308.

18 Mill, A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive.

19 Przeworski and Teune, The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry.

20 Seawright and Gerring, “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research,” 294–308, p. 300.

21 Inglehart, Cultural Evolution.

22 Harteveld, et al., “Multiple Roots of the Populist Radical Right,” 440–461.

23 Norris and Inglehart. Cultural Backlash.

24 Norris, “Does Praying Together Mean Staying Together?” 285–305. p. 290; Zoltán and Bozóki, “State and Faith”.

25 Ben-Porat et al., “Populism, Religion and Family Values Policies in Israel, Italy and Turkey,” 1–23.

26 Jenssen, “Norske holdninger etter 1945 – Et verdikonservativt tilbakeslag”.

27 Sƚowikowski and Pierzgalski, “The Party System and Voting Behavior in Poland”.

28 Bozoki and Simon, “Two Faces of Hungary,” 221–248. p. 238.

29 Andersen and Bjørklund, “Radical Right-wing Populism in Scandinavia”; Jupskås and Ivarsflaten, “Norway,” 64–77.

30 Rose and Shin, “Democratization Backwards,” 331–354. p. 348.

31 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash.

32 Barslund and Busse, “Too much or too Little Labour Mobility?” 116–123.

33 Batory, “Populists in Government?” 283–303. p. 289–90.

34 Halasz, “The Rise of the Radical Right in Europe and the Case of Hungary,” 490–494.

35 Grajczjár et al., “Routes to Right-wing Extremism in Times of Crisis an Austrian-Hungarian Comparison Based on the SOCRIS Survey,” 95–117.

36 Aardal, Bergh, and Haugsgjerd, “Politiske stridsspørsmål, ideologiske dimensjoner og stemmegivning,” 44–80.

37 Strabac and Listhaug, “Anti-Muslim Prejudice in Europe,” 268–286.

38 Ivarsflaten, “What Unites Right-wing Populists in Western Europe?” 3–23.

39 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash.

40 Wilkin, “The Rise of ‘Illiberal’ Democracy,” 5–42.

41 Krekó and Mayer, “Transforming Hungary–Together?” 183–205.

42 Enyedi, “Plebeians, Citizens and Aristocrats or Where is the Bottom of Bottom-up?” 229–244; Batory, “Populists in Government?” 283–303; Csehi, “Neither Episodic, nor Destined to Failure?” 1011–1027.

43 Ramet, Ringdal, and Dośpiał-Borysiak, eds. Civic and Uncivic Values in Poland.

44 Jenssen, and Male Kalstø, “Did the Financial Crisis Save the Red-Green Government in the 2009 Norwegian Election–the Dissatisfaction with Rising Expectations Superseded By a Grace Period?” 70–100.

45 Jenssen, “The Rise of Racism and the Norwegian New Right,” 29–54.

46 Jenssen, “Norske holdninger etter 1945 – Et verdikonservativt tilbakeslag”.

47 Norris and Inglehart. Cultural Backlash.

48 Ivarsflaten, “What Unites Right-wing Populists in Western Europe?” 3–23.

49 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash.

50 Schäfer, “Cultural Backlash?” 1–17.

51 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash.

52 Tillman, “Authoritarianism and Citizen Attitudes Towards European Integration," 566–589.

53 Mudde and Kaltwasser, Populism.

54 Hungary: 1.603; Italy: 2.220; Norway: 5.337; Poland: 1.885.

55 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash.

56 Schäfer, “Cultural Backlash?” 1–17.

57 Supplementary materials.

58 Norris and Inglehart. Cultural Backlash; Interwar generation (1900–45); Baby Boomers (1946–64); Generation X (1965–79); Millennials (1980–96).

59 Ibid.

60 Schäfer, “Cultural Backlash?” 1–17; Table in supplementary materials.

61 Harteveld et al., “Multiple Roots of the Populist Radical Right,” 440–461.

62 Schäfer, “Cultural Backlash?” 1–17. p. 16.

63 Norris and Inglehart, Cultural Backlash.

64 Ozzano, “Religion, Cleavages, and Right-wing Populist Parties,” 65–77.

65 Ibid., 71.

66 Vossen, “Classifying Wilders,” 179–189.

67 Schwörer, “Right-wing Populist Parties as Defender of Christianity?” 387–413; Ozzano, “Religion, Cleavages, and Right-wing Populist Parties,” 65–77.

68 Brils, Muis, and Gaidytė, “Dissecting Electoral Support for the Far Right,” 1–28.

Bibliography

- Aardal, Bernt, Johannes Bergh, and Atle Haugsgjerd. “Politiske stridsspørsmål, ideologiske dimensjoner og stemmegivning.” Bergh og B. Aardal (Red.), Velgere og valgkamp. En studie av stortingsvalget (2017): 44–80.

- Adorno, Theodor, et al. The Authoritarian Personality. London: Verso Books, 2019.

- Andersen, Jørgen Goul, and Tor Bjørklund. “Radical Right-wing Populism in Scandinavia: From Tax Revolt to Neo-liberalism and Xenophobia.” In The Politics of the Extreme Right: From the Margins to the Mainstream, edited by Paul Hainsworth, 193–224. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2000.

- Barslund, Mikkel, and Matthias Busse. “Too much or too Little Labour Mobility? State of Play and Policy Issues.” Intereconomics 49, no. 3 (2014): 116–123.

- Batory, Agnes. “Populists in Government? Hungary's “System of National Cooperation.” Democratization 23, no. 2 (2016): 283–303.

- Bell, Daniel. The End of Ideology: On the Exhaustion of Political Ideas in the Fifties. New York: Collier Books; Collier-Macmillan, 1965.

- Ben-Porat, Guy, et al. “Populism, Religion and Family Values Policies in Israel, Italy and Turkey.” Mediterranean Politics 28, no. 2 (2023): 155–177.

- Bergh, Johannes, and Karlsen Rune. “Politisk dagsorden og sakseierskap ved stortingsvalget i 2017.” In Velgere og valgkamp, edited by Johannes Bergh, and Bernt Aardal, 27–43. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk, 2019.

- Bozoki, Andras, and Eszter Simon. “Two Faces of Hungary: From Democratization to Democratic Backsliding.” In Central and Southeast European Politics Since 1989, 221–248. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Brils, Tobias, Jasper Muis, and Teodora Gaidytė. “Dissecting Electoral Support for the Far Right: A Comparison Between Mature and Post-communist European Democracies.” Government and Opposition (2020): 1–28.

- Chu, Lan T. “Unfinished Business: The Catholic Church, Communism, and Democratization.” Democratization 18, no. 3 (2011): 631–654.

- Csehi, Robert. “Neither Episodic, nor Destined to Failure? The Endurance of Hungarian Populism after 2010.” Democratization 26, no. 6 (2019): 1011–1027.

- Doorenspleet, Renske, and Petr Kopecký. “Against the Odds: Deviant Cases of Democratization.” Democratization 15, no. 4 (2008): 697–713.

- Dośpiał-Borysiak, Katarzyna, Michał Klonowski, and Agata Włodarska-Frykowska. “European Values in Poland: The Special Case of Ethnic and National Minorities.” In Civic and Uncivic Values in Poland, 79. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2019. doi:10.7829/j.ctvs1g8rj.9.

- Enyedi, Zsolt. “Plebeians, Citizens and Aristocrats or Where is the Bottom of Bottom-up? The Case of Hungary.” In Kriesi, Hanspeter und Takis S. Pappas, Hrsg. 2015. European Populism in the Shadow of the Great Recession. Studies in European Political Science, edited by R. A. Huber, 229–244. Colchester: ECPR Press, 2015.

- Fukuyama, F. “The End of History?” The National Interest 16 (1989): 3–18.

- Grajczjár, István, et al. “Routes to Right-wing Extremism in Times of Crisis An Austrian-Hungarian Comparison Based on the SOCRIS Survey.” socio. hu (2018): 95–117.

- Halasz, Katalin. “The Rise of the Radical Right in Europe and the Case of Hungary: ‘Gypsy crime’ Defines National Identity?” Development 52, no. 4 (2009): 490–494.

- Harteveld, Eelco, et al. “Multiple Roots of the Populist Radical Right: Support for the Dutch PVV in Cities and the Countryside.” European Journal of Political Research 61, no. 2 (2022): 440–461.

- Inglehart, Ronald. “The Silent Revolution in Europe: Intergenerational Change in Post-industrial Societies.” American Political Science Review 65, no. 4 (1971): 991–1017.

- Inglehart, Ronald. The Silent Revolution. Changing Values and Political Styles Among the Western Publics. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977.

- Inglehart, Ronald. “Post-materialism in an Environment of Insecurity.” American Political Science Review 75, no. 4 (1981): 880–900.

- Inglehart, Ronald. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990.

- Inglehart, Ronald. Cultural Evolution: People's Motivations are Changing, and Reshaping the World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth. “What Unites Right-wing Populists in Western Europe? Re-examining Grievance Mobilization Models in Seven Successful Cases.” Comparative Political Studies 41, no. 1 (2008): 3–23.

- Jenssen, Anders Todal. “The Rise of Racism and the Norwegian New Right.” In Encounter with Strangers-The Nordic Experience, 29–54. Lund: Lund University Press, 1994.

- Jenssen, Anders Todal. “Norske holdninger etter 1945 – Et verdikonservativt tilbakeslag.” In Valg og politikk etter 1945, edited by Johannes Bergh, Atle Haugsgjerd, and Rune Karlsen, 55–73. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk, 2020.

- Jenssen, Anders Todal, and Åshild Male Kalstø. “Did the Financial Crisis Save the Red-Green Government in the 2009 Norwegian Election–the Dissatisfaction with Rising Expectations Superseded By a Grace Period?” World Political Science 8, no. 1 (2012): 70–100.

- Jupskås, Anders R., and Elisabeth Ivarsflaten. “Norway: Populism from Anti-tax Movement to Government Party.” In Populist Political Communication in Europe, 64–77. Oxford: Taylor & Francis, 2016.

- Krekó, Péter, and Gregor Mayer. “Transforming Hungary–together?: An analysis of the Fidesz–Jobbik Relationship.” In Transforming the Transformation? 183–205. London: Routledge, 2015.

- Lieberman, Evan S. “Nested Analysis as a Mixed-method Strategy for Comparative Research.” American Political Science Review 99, no. 3 (2005): 435–452.

- Mill, John Stuart. A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive. 8th Republished as Project Gutenberg Ebook, released 31 January 2009. ed. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1882.

- Minkenberg, Michael, and Ronald Inglehart. “Neoconservatism and Value Change in the USA: Tendencies in the Mass Public of a Postindustrial Society.” In Contemporary Political Culture. Politics in a Postmodern Age, edited by John R. Gibbins, 81–109. London: Sage, 1989.

- Moses, Jonathon, and Torbjørn Knutsen. “Chapter 1. Introduction.” In Ways of Knowing: Competing Methodologies in Social and Political Research, 1–14. London: Red Globe Press, 2012.

- Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. Populism: A Very Short Introduction. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- Nagle, John. “Ethnos, Demos and Democratization: A Comparison of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland.” Democratization 4, no. 2 (1997): 28–56.

- Norris, Pippa. “Does Praying Together Mean Staying Together? Religion and Civic Engagement in Europe and the United States.” In Religion and Civil Society in Europe, edited by Joep de Hart, Paul Dekker, and Loek Halman, 285–305. Dordrecht: Springer, 2013.

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Ozzano, Luca. “Religion, Cleavages, and Right-wing Populist Parties: The Italian Case.” The Review of Faith & International Affairs 17, no. 1 (2019): 65–77.

- Przeworski, Adam, and Henry Teune. The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry. New York: Wiley-Interscience, 1970.

- Ramet, Sabrina P., Kristen Ringdal, and Katarzyna Dośpiał-Borysiak, eds. Civic and Uncivic Values in Poland: Value Transformation, Education, and Culture. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2019.

- Rose, Richard, and Doh Chull Shin. “Democratization Backwards: The Problem of Third-wave Democracies.” British Journal of Political Science 31, no. 2 (2001): 331–354.

- Schäfer, Armin. “Cultural Backlash? How (Not) to Explain the Rise of Authoritarian Populism.” British Journal of Political Science 52, no. 4 (2022): 1977–1993.

- Schwörer, Jakob. “Right-wing Populist Parties as Defender of Christianity? The Case of the Italian Northern League.” Zeitschrift für Religion, Gesellschaft und Politik 2, no. 2 (2018): 387–413.

- Seawright, Jason, and John Gerring. “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options.” Political Research Quarterly 61, no. 2 (2008): 294–308.

- Sƚowikowski, Michał, and Michał Pierzgalski. “The Party System and Voting Behavior in Poland.” In Civic and Uncivic Values in Poland, 41–78. Budapest Central European University Press, 2019.

- Strabac, Zan, and Ola Listhaug. “Anti-Muslim Prejudice in Europe: A Multilevel Analysis of Survey Data from 30 Countries.” Social Science Research 37, no. 1 (2008): 268–286.

- Tillman, Erik R. “Authoritarianism and Citizen Attitudes Towards European Integration.” European Union Politics 14, no. 4 (2013): 566–589.

- Vossen, Koen. “Classifying Wilders: The Ideological Development of Geert Wilders and His Party for Freedom.” Politics 31, no. 3 (2011): 179–189.

- Wilkin, Peter. “The Rise of ‘Illiberal’ Democracy: The Orbánization of Hungarian Political Culture.” Journal of World-Systems Research 24, no. 1 (2018): 5–42.

- Zoltán, Ádám, and András. Bozóki. “State and Faith: Right-wing Populism and Nationalized Religion in Hungary.” Intersections. East European Journal of Society and Politics 2, no. 1 (2016): 98–122.