ABSTRACT

The Danish general election in 2022 appeared to foster a paradox: the campaign was remarkably personalized, while voters were less likely to vote for an individual candidate compared to the last five elections. Personalization in the campaign did not seem to spill over to voting behaviour. The study argues and shows using register and survey data that institutional barriers limited the direct expression of personalized electoral behaviour, but voters strongly motivated by political leaders compensated by casting party list votes. The true paradox of the Danish election was that decreasing preferential votes actually reflected increasing personalization, concentrating personal votes in the hands of party leaders. This finding speaks to a general concern about how different arenas of political personalization interact. It suggests that political institutions can only partly contain the personalization of politics because political actors – elites as well as ordinary voters – navigate within the given institutions to maximize their personalized political preferences, finding opportunities to compensate for the institutional barriers. Democracies must, therefore, consider institutional designs as well as political cultures when meeting the possible challenges posed by increased personalization of politics.

Introduction

When Danish voters went to the polls on 1 November 2022, they found two brand new parties – registered only five months prior to the election – on the ballots. Both parties were founded by very prominent former ministers as splinter parties of one of the two main parties (Venstre – the liberal party). The Moderates was founded by former prime minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen campaigning for a broad, centre coalition government. The Danish Democrats – Inger Støjberg was formed by the former minister for integration and immigration Inger Støjberg using her own name as part of the party label and campaigning to limit immigration and increase support to rural areas. These two very personalized parties competed against a highly personalized campaign led by the Social Democrats strongly promoting their incumbent Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen.Footnote1 The two main established parties of the right-wing opposition (Venstre – the liberal party and the Conservatives) followed through and conducted a negative campaign targeting Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen’s personal habitus on a level not seen before in Denmark. The main feature of the 2022 campaign, however, was the new social media-based and extremely personalized campaign led by the party Liberal Alliance establishing a brand for their leader Alex Vanopslagh as “the King of TikTok,” thus nurturing a very strong – and unprecedented – fan culture, not least among the young voters.Footnote2 Traditionally, the campaign is centred around a few nationally broadcasted debates among the party leaders, which reach very broad audiences in Denmark. Moreover, in general, the party leaders get the lion’s share of media attention. This was indeed the case in the 2022 campaign, with 57 percent of all newspaper articles covering the campaign and mentioning at least one of the 14 party leaders, the highest share over the last four elections.Footnote3

So far, this prologue on the 2022 Danish parliamentary election seems to fit very well into a narrative of politics getting more and more personalized – a narrative that has been told (and discussed) intensively in the literature for the better part of the last two decades.Footnote4 Pundits observing this most recent campaign could very well conclude that this was the moment when the personalization of politics hit Denmark for real. This was when the traditional party-based version of democracy started if not to erode then to be challenged by a mode of democracy centred more around persons and personalities, and where the foundation of democratic representation began to change from party platforms to personal appeals. However, when election day came, the picture became more blurred. Although the four parties running very personalized campaigns for their party leaders all fared well at the polls, the percentage of votes cast as preferential votes (votes for individual candidates rather than party lists) declined (from 52 to 46 percent) to become the lowest in four decades.

As will be discussed below, personalization is a multi-dimensional concept that can be applied to different spheres of politics. In the electoral sphere of personalization, casting a preferential vote when the voter has the opportunity to vote for either a specific candidate or a party list (as is the case in Denmark) can be perceived as a relevant measure of personalization. Therefore, it seems paradoxical that a presumably more personalized campaign was accompanied by a decline in this kind of personalized voting behaviour. It is, however, important to notice that when measuring personalization, we can be looking at all the candidates, or we can focus on the few persons leading their parties in the campaign and in the fight for political power.Footnote5 If focus moves from parties to persons in general (i.e. all candidates), it has been denoted decentralized personalization, whereas in the case where only a few persons get the electoral focus (i.e. the party leaders), it has been denoted centralized personalization.Footnote6

The paradox pointed out is intriguing. First, it illustrates that personalization is not as simple a concept as it is sometimes portrayed in the popular debate, and not least that the mechanism of personalizing politics is probably more complex than the one based on merely pointing to an ongoing trend. Rahat and Sheafer distinguish between three different types of political personalization: the media, the institutional, and the behavioural type.Footnote7 So far, empirical evidence for personalization across all the different types is mixed and country specific.Footnote8 Moreover, the different types may not always co-develop.Footnote9 Looking for the mechanism behind the seemingly opposite directions in campaign and voting personalization, the institutional dimension connecting the two is relevant to consider. The personalization of the institution of electoral systems itself has been thoroughly researched by Renwick and Pilet.Footnote10 And more specifically, the effect of the electoral system on the personalization of electoral behaviour has been shown by Wauters and colleagues for the Belgian case.Footnote11 We thus ask: Can institutions contain personalization limiting the spillover from one arena to another?

Second, the paradox suggests that voters either ignored the personalized campaign or found ways to express personalized preferences despite institutional barriers. The first option adds to the separation of types or arenas of political personalization, whereas the second option solves the paradox illuminating “hidden” electoral personalization not visible from the basic indicator of preference votes. For instance, Ferreira da Silva et al. show that party leaders influence not only vote choice but also incentives to turn out to vote.Footnote12 Hence, electoral personalization may materialize in different ways. We therefore ask: Do voters find alternative ways to express personalized preferences, and if so, which voters are most likely to use such compensational, personalized voting strategies?

The Danish case suggests a situation where a more complex relationship exists between the personalization of campaigns, the electoral system, and voting behaviour, and we will, therefore, investigate the Danish case more carefully to disentangle the interplay between these dimensions further and answer our research questions. In the next section, and based on existing literature, we will develop an argument for institutional containment and compensational voting more carefully to provide a theoretical answer to our questions, which are operationalized into four testable hypotheses. In a nutshell, we claim that in district-based PR electoral systems where the party leaders are running a nationwide campaign but are restricted to run personally only in one of several districts, the level of preference votes within the political parties will differ across districts according to whether we observe the one district where the party leader is on the ballot or the several others where the voters will not find the party leader’s name on the ballot. Wauters and colleagues have claimed that features of the party (the age and extremism of the party) can explain levels of preference votes.Footnote13 We add to this line of research, theorizing how list votes can be perceived as compensational vote personalization and how party leader sympathy, party leader polarization, and party belonging should, therefore, influence voters’ likelihood of casting a list vote when not being able to vote for the preferred party leader.Footnote14

We test these hypotheses by combining election statistics and voter survey data (N = 2,372) from Denmark. Our results show, first, that institutions are indeed able to contain personalization, as the electoral system hindered Danish voters in expressing strong personal preferences for party leaders as the leader did not run in their district. The number of votes cast for individual candidates and especially party leaders was, therefore, constrained. However, secondly, the results show that voters found ways to compensate for the institutional constraints by voting for the party list rather than an alternative candidate when they could not vote for their preferred party leader. As such, electoral personalization supported the concentration of personal votes to party leaders, especially leaders of personalized parties and running personalized campaigns. This entails that the true paradox of the 2022 Danish elections is not that a personalized campaign was accompanied by a decrease in preferential votes but that the decrease in preferential votes can be interpreted as a sign of increasing personalization.

The theoretical argument and empirical results contribute to the literature on personalization and especially to our understanding of interpreting indicators of personalized behaviour and how different arenas of personalization can be connected. Hereby, they inform our public debate about one of the most salient changes in liberal democracies, potentially destabilizing democratic institutions and cultures as individual politicians gain and guard increased personal powers.Footnote15

Compensational list vote as an expression of personalized voting behaviour

Personalized politics describes a situation in which political persons matter more to politics than political collectives, typically political parties. The personalization of politics describes developments towards a situation where individual political actors become more prominent at the expense of parties and collective identities.Footnote16 Both phenomena – the process of personalization and the static situation of personalized politics – can be studied in multiple realms of politics: in the design of political institutions, in media coverage, or in the behaviour of political actors such as politicians and voters. Therefore, it may be more meaningful to talk about personalizations rather than the personalization of politics.Footnote17

A key concern is to understand how these realms of personalization relate. Scholars have been particularly devoted to studying how political institutions – e.g. candidate selection procedures and electoral systems – influence (personalized) political behaviour.Footnote18 This focus is not limited to the study of personalization as it relates to a fundamental interest in understanding representative linkages more broadly.Footnote19 As such, political institutions have been related to the prominence of geographical representation and the general representative effort of legislators.Footnote20 Even though political institutions are always products of politics as they are created by political actors at some point, their stability and consequentiality often put them in the position of independent variables. Most often, they are taken to explain political behaviour rather than the other way around. As such, the design of political institutions is also taken to influence the incentives and possibilities for personalizing political behaviour and is potentially key to explaining differences in personalized politics across time, political systems, and parties.Footnote21

The electoral system is especially important as it defines the incentives and possibilities for voters as well as politicians for creating representative linkages in democratic systems. Within the literature on personalization, electoral systems have been used to explain personalized behaviour among politicians, basically arguing that personal vote-seeking behaviour should be more prominent among politicians acting within candidate-oriented systems compared to party-oriented systems.Footnote22 Electoral systems have been classified in slightly different ways, but a common distinction includes three types: closed list, open list, and mixed systems. Systems are more candidate oriented if (1) voters can cast preferential votes for individual candidates, and (2) preferential votes determine which candidates are elected. Systems are more party oriented if (1) voters can cast a vote for the party list, and (2) party list ranking determines which candidates are elected.

Fewer have studied how electoral systems influence the behaviour of voters, which makes sense as voters’ behaviour is often studied by their vote rather than, for instance, their campaign attention or news consumption.Footnote23 Their political behaviour by vote is often perceived as uniform within systems as it is determined by the ballot opportunities. However, in some systems (e.g. Denmark, Belgium, or Austria), ballots allow voters to express preferences for either candidates or parties. In these systems, it is possible to study personalized voter behaviour by the type of vote voters cast: a list vote can be taken as a collective vote, while a candidate vote can be taken as a personalized vote. As all candidates run on party lists, a candidate vote automatically transfers into a party vote, as such it is difficult to fully isolate the personalized motivation behind a candidate vote.Footnote24 However, it is equally difficult to disentangle the candidate motivation behind a party list vote, as we will explain below. Moreover, a candidate vote – motivated mainly by party list or candidate – personalize the electoral base of each candidate and hence contribute to the decentralized or centralized personalization of political parties.Footnote25 Therefore, we suggest that a candidate vote is a relevant proxy for the personalized nature of voter-party-relations. Yet, voters’ opportunities for casting votes are influenced by not only the ballot design but also the constituency demarcation. Again, important variation can be described in three broad categories: single-member districts, multi-member districts, and no districts. In single-member districts (UK as a prime example), preferential and list votes typically merge as voters will have to switch parties to switch candidates. In systems with no districts (e.g. Israel and the Netherlands), voters are not limited to geographically defined party lists. Finally, in the most common multi-member districts, voters’ vote choice is constrained by geographically defined lists of candidates. This is the case in Belgium as well as in Denmark where list and preference votes are possible. With these two ballot features, the simple inference relating list votes to collectively oriented voter behaviour and candidate votes to personalized voter behaviour may be misleading.Footnote26 Voters preferring a candidate who is not on their ballot cannot express their personalized preference and must, therefore, consider alternatives, i.e. cast a preference vote for another candidate or – as a compensational strategy – cast a vote for the party list.

As for the compensational strategy, the likelihood of voters being in the situation of having to find alternatives for their preferred candidate, we argue, is most likely for voters preferring high-profile politicians prominent in national news and therefore most likely to be considered by voters outside their districts. Party leaders especially are likely to gain such media attention and recognition nationally.Footnote27 When voters are not able to vote for their preferred party leader as the person is running in a different district, we argue that they can use a party list vote as a compensational strategy to support the party leader. By casting a list vote rather than an alternative candidate vote, they minimize information costs associated with identifying an alternative candidate, and they express support for the party their preferred candidate is leading. The success of the party is closely related to the success of the party leader, and thus, a vote for the party supports the success of the party leader.Footnote28

Going back to the distinction between centralized personalization, where votes are concentrated on the party leaders, and decentralized personalization, where the many preferential votes are spread out on more candidates, it is important for our analysis to notice that “the two faces of personalization (centralized and decentralized) may not always go hand in hand.”Footnote29 If party leaders can run only in one district, it will put a limit on the number of personal votes the leader can win. A centralized campaign personalization can, thus, be contained by decentralized institutions such as electoral systems with district-based nominations.Footnote30 In Belgium – with a similar electoral system to Denmark – Wauters et al. indeed find that the share of preference votes is lower for lists not including the leader and that this trend intensifies over time.Footnote31 They infer that centralized personalization among voters increases at the expense of decentralized personalization. This finding has been nuanced by Dodeigne and Pilet showing that, in Belgium, the possibility of casting multiple preference votes contributes “to resisting the overarching trend of centralized personalization” as multiple identities can be mobilized by splitting the vote.Footnote32 This opportunity of casting multiple preference votes is not available in Denmark, and as we focus on the compensational strategy of supporting the party leader indirectly by casting a list vote in the absence of the preferred party leader, we argue that list votes will more likely be cast as compensational list votes for the party leader among voters who are unable to vote for their preferred party leader in their own district. We therefore expect that:

H1a: The share of preferential votes on a party list will be larger in the district of the party leader compared to other districts.

H1b: Voters from the district where the party leader of the party they vote for is running will cast a preferential vote more often than voters supporting the same party but voting in districts where the party leader is not on the ballot.

If the list vote is indeed driven by personalized political preferences that cannot be expressed due to the electoral system, voters with strong sympathy for the party leader should be more likely to cast a list vote when the party leader is absent from the list, using the list vote as a compensation strategy for expressing support for this party leader. We therefore expect that:

H2: The positive relationship between having the opportunity to vote for the preferred party leader and casting a preference vote is stronger for voters with higher sympathy for their party leader compared to voters with more moderate sympathy.

H3: The positive relationship between having the opportunity to vote for the preferred party leader and casting a preference vote is weaker for voters with a sense of party belonging compared to voters without it.

H4: The positive relationship between having the opportunity to vote for the preferred party leader and casting a preference vote is stronger for voters supporting polarizing party leaders compared to voters preferring leaders who are less polarizing.

Case selection and data

As already pointed at in the introduction, list PR electoral systems can help explain the immediate paradoxical relationship between centralized and decentralized personalization. As Wauters et al. states: “In the vast majority of countries using list PR, candidates are running in only one district and not nationwide,” and they continue, “In these countries, the situation of a voter motivated by the party leader but not finding his name on the ballot in his district is, therefore, rather common, and the tension between centralized and decentralized personalization can also be found there.”Footnote35

We will use Denmark as a case in point. An interesting feature of Denmark’s electoral system is that it is both personalized and has built-in limitations for personalization since the electoral system is also organized into decentralized 10 multi-member districts. Candidates may only run in one district, and voters can only vote for candidates running in their own district. The electoral system is designed for district-level competition, while crucial campaign events take place on national platforms. The Danish system sets the basis for personalized behaviour among candidates and voters as “[i]ntra-party preference voting, by definition, rules out voters’ ability to rely solely on the shared party label as a readily available voting cue and requires legislators to set themselves apart from co-partisan competitors in constituents’ minds.”Footnote36

Apart from meeting the criteria of being a PR list system with district-based nominations, Denmark has been chosen for two reasons. First, the pattern of a simultaneous increasingly centralized and decreasingly decentralized electoral personalization can be observed. As pointed out in the introduction, the most recent parliamentary election in Denmark (November 2022) presented several phenomena pointing at electoral personalization: person-driven parties established right before the election and already established parties running extremely person-focused campaigns. However, while the centralized electoral personalization increased, the decentralized electoral personalization declined.

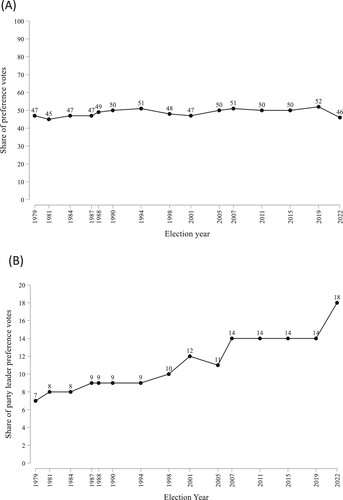

This is demonstrated in . We use official election data from Statistics Denmark including information on where each candidate is listed (party and district), how many personal votes and list votes were cast, and how many personal votes each candidate received. These statistics are collected over multiple years, and shows how the most recent general election produced the two opposite trends of personalization.Footnote37 , panel A shows the share of preference votes relative to all valid votes in all general elections since 1979. Across elections, about half of the votes are cast for a specific candidate. There is no trend towards more personalized voting behaviour using preference votes as an indicator. However, a decline was observed at the 2022 election where the share of preferential votes (46 percent) is the smallest share since 1981. Panel B shows the share of preference votes for the party leaders relative to all preference votes. This share shows an upward trend throughout the period. The increase is gradual with two important “jumps.” The share increases in the 2007 election, which was the first election after an electoral reform reducing the number of electoral districts from 17 to 10. Therefore, ceteris paribus, more voters should be able to vote for their party leader, and the increase is in line with our argument that decentralized electoral systems hinder voters in expressing centralized, personalized preferences directly. However, the second “jump” appears in the most recent election where no institutional reform can explain the change. Rather, the two panels provide the first suggestive evidence for personalized compensation, as the overall share of preference votes dropped while the share of preference votes for the party leaders increased. Regressing the share of party leader preference votes on time, a reform dummy, number of parties running for election, and the number of votes casted at the election suggests that centralized personalization is indeed increasing over time.Footnote38

Figure 1. Time trend in preference votes of total votes (panel A) and party leader preference votes of total preference votes (panel B).

Note: based on electoral reports from Statistics Denmark.

Second, since we would like to shift the analysis to individual-level data, Denmark offers very rich data since we can take advantage of the large voter survey data (N = 2,372, response rate 38) collected in the Danish National Election Study.Footnote39 The dataset contains high-quality survey data collected among Danish voters right after the election, and these have subsequently been merged with register data on the electoral district of the voter.Footnote40 The dataset is representative of the Danish voter population on gender, age, party choice, and region.

When testing the four hypotheses, our dependent variable is dichotomous and shows whether the respondent indicated to have cast a preference vote, 1, (53 percent) or not, 0, (47 percent).Footnote41 As evident, the share of preference votes indicated by respondents is slightly larger than in the election statistics (, panel A), which may be due to sampling error – maybe voters with higher political interests are more likely to answer the survey and more likely to cast a preference vote.

As for the independent variables, to test H1, we construct the variable Party leader district, which indicates whether the leader of the voter’s preferred party was running in the voter’s electoral district, 1, (15 percent) or not, 0, (85 percent). We use the election data to link party leaders to electoral districts and survey data to link respondents to party and electoral district. For example, if a respondent prefers the Social Democrats and votes in the Northen Jutland district, the variable Party leader district is one as the leader of the Social Democrats was indeed running in the district.

To test H2, we include the variable Party leader sympathy indicating how much the respondents like the leader of their preferred party. It is measured by the question: “How would you place the party leaders on a scale from 0 to 10 if 0 means that you really dislike the leader, and 10 means that you really like the leader?” We only use the answer related to the leader of the party the respondent voted for. Unfortunately, the survey did not include all party leaders. The leaders of the two smallest parties, Free Greens and the Christian Democrats, are not included. These parties did not receive enough votes to win seats in parliament, and only 26 respondents had to be excluded for this reason. The mean sympathy for own party leader is relatively high (7.88) but also varies substantively with a standard error of 2.23.

To test H3, we include the variable Party belonging,Footnote42 which indicates whether respondents perceive themselves as supporters of a specific party, 1 (34 percent), or not, 0 (66 percent). It is measured by the question: “Many see themselves as supporters of a given party. Many others do not feel like supporters of any specific party. Do you see yourself as, for instance, a social democrat, conservative, radikal, venstremand, or SF’er,Footnote43 or do you not feel like a supporter of any specific party?” The answer “Yes, I do feel like a supporter of a specific party” is coded 1, while “No, I am not a supporter of any specific party” or “Don’t know” are coded 0.

To test H4, we include the variable Party leader polarization, which is measured on the party leader level – completely overlapping with party level in this case – and utilizes the same question as used for measuring party leader sympathy. Party leader polarization indicated the difference between the mean sympathy among own party voters and the mean sympathy among non-party voters. For instance, respondents voting for the Social Democrats have an average sympathy score for the party leader and prime minister, Mette Frederiksen, of 8.45, while respondents not voting for the Social Democrats express a sympathy with Mette Frederiksen of, on average, 3.98. The party leader polarization score for Mette Frederiksen is therefore 4.47. Overall, the mean party leader polarization score is 4.31, with a standard deviation of 0.78. describes the popularity and polarization of the included party leaders.

Table 1. Party leader sympathy and polarization.

While these are our four main independent variables, we also include four control variables in the analyses: political interest, education, age, and sex. Political interest is measured in four categories: (1) not interested at all, (2) only a little interested, (3) somewhat interested, and (4) very interested. Education is measured in six categories: (1) only primary school, (2) high school, (3) vocational education (4) short higher education (<3 years), (5) medium-length higher education (3–4 years), and (6) long higher education (>4 years). Sex is measured in two categories, female (1) and male (0),Footnote44 and age is measured in years by the register-based variable of age on election day supplied by the survey dataset.

All models using the survey data are estimated with an analytical weight constructed to model the difference between survey respondents and voter population regarding region, age, gender, education, and party choice.Footnote45

Results

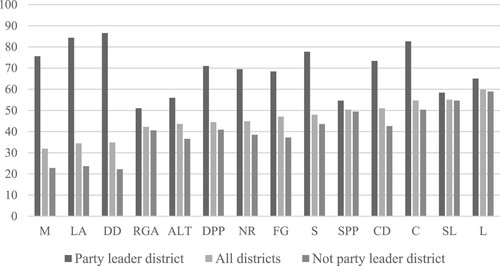

The election data has high external validity as all votes are counted and is, therefore, used to test our first hypothesis (H1a) regarding the larger share of preference votes for party lists running the party leader. H1a stated that more preference votes should be cast on party lists running the party leader. shows the share of preference votes in (1) party leader districts, (2) all districts, and (3) district without party leader across all parties. It is evident that for all parties, more preference votes are cast in the district where the party leader runs compared to districts where it is not the case. However, it is also evident that the differences are not equally large across parties. Differences are particularly large for the Moderates, the Danish Democrats – Inger Støjberg, and the Liberal Alliance. These are exactly the parties mentioned in the introduction as prominent examples of personalized parties (the Moderates and the Danish Democrats – Inger Støjberg) and personalized campaigns (the Liberal Alliance). In contrast, differences are small for the Liberals, the Social Liberals, and the Socialist People’s Party representing older and more established parties in Denmark, potentially hosting more party supporters among voters. However, the difference is also relatively substantial for the Social Democrats and the Conservatives who also represent old and well-established parties in Danish politics. Hence, centralized personalization in preference votes is not only a young party trait that diminishes as parties institutionalize.

Figure 2. Share of preference votes across parties and presence of party leader on list. 2022 General Election.

Note: party abbreviations are M: Moderates, LA: Liberal Alliance, DD: Danish Democrats – Inger Støjberg, RGA: Red–Green Alliance, ALT: Alternative, DPP: Danish People’s Party, NR: New Right, FG: Free Greens, S: Social Democrats, SPP: Socialist People’s Party, CD: Christian Democrats, C: Conservatives, SL: Social Liberals, L: Liberals.

The Social Democrats ran as the former governing party and thus included former ministers as prominent politicians on their lists. These candidates are potentially able to attract more preference votes.Footnote46 Two ministers are particularly prominent (finance minister Nicolai Wammen and health minister Magnus Heunicke, who was very visible during the Covid-19 crisis) and also electorally successful collecting the second and third most preference votes in the party. Still, in both districts the share of preference votes is clearly lower (47 and 45 percent) than in the district of the party leader (78 percent). Hence, even though other prominent politicians do indeed mobilize more preference votes, the party leader stands out.

Regressing the share of preference votes on whether the party leader runs or not including party fixed effects shows that the difference in share of preference votes across party leader districts and non-party leader districts is statistically significant. The difference amounts to 30 percentage points on average (p < 0.001). Few of the differences across parties are statistically significant. Using the Liberals, the largest none-prime minister party, as a reference category and including an interaction term between party leader district and party, the relationship between party leader districts and share of preference votes is only stronger for the Liberal Alliance, the Moderates, and the Danish Democrats – Inger Støjberg on a 95 percent confidence interval. The relationship is also stronger for the Prime Minister’s party – the Social Democrats – but the interaction term is not statistically significant (p = 0.059). In sum, the analyses support H1a as district party lists running the party leader receive a substantially larger share of preference votes compared to district party lists not running the party leader.

presents the results of the logistic regressions based on survey data and using whether (1) or not (0) a respondent reported to have cast a preference vote as a dependent variable. In Model 1, the first hypothesis stipulating that more preferential votes are cast in the districts where the party leader is running is repeated in its individual-level variant (H1b), and it is, unsurprisingly, demonstrated that voters are more likely to cast a preference vote when the preferred party leader is running in the voter’s district. Among survey respondents, the impact of being able to vote for the preferred party’s leader increases the likelihood of casting a preference vote by 26 percent. The predicted likelihood of voters being able to vote for their preferred party’s leader to cast a preference vote is 77 percent. If the voter is not able to vote for the preferred party’s leader, the predicted likelihood of casting a preference vote is 51 percent. Notice again that the level of reported preference voting is higher than the actual share of preference votes cast; however, the predicted difference of 26 percent is very similar to the 30 percent difference estimated with election data. Hence, the survey data replicates the results based on election statistics.

Table 2. Predicting preference vote cast.

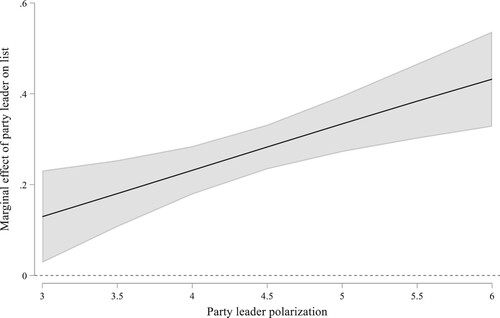

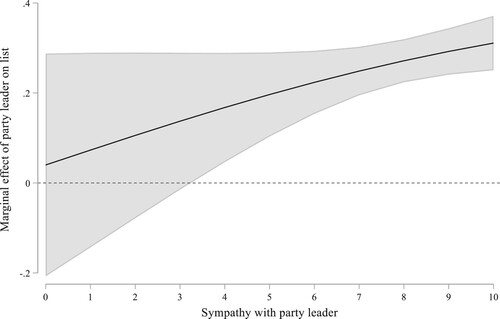

The second hypothesis (H2) stated that if compensational, personalized voting is in place and part of the explanation for the patterns revealed above, the positive relationship between having the opportunity to vote for the preferred party leader and casting a preference vote is stronger for voters with higher sympathy for their party leader compared to voters with more moderate sympathy. Model 2 in is the relevant model for evaluating H2. The interaction term between party leader district and party leader sympathy is positive and statistically significant, which means that the correlation between being able to vote for the preferred party leader and the likelihood of casting a preference vote is stronger for respondents with higher sympathy for the relevant party leader as predicted by the hypothesis. The interaction is illustrated in . The figure shows the marginal effect of the party leader running in the district for casting a preference vote across different levels of party leader sympathy.Footnote47

Figure 3. Marginal effect of party leader running on list across voters’ party leader sympathy (H2).

When the sympathy for the party leader is very modest – below 3 – it does not matter for voters’ decision to cast a preference or list vote whether the party leader runs in the voter’s district or not. In contrast, for voters with very high sympathy – over 7 – for their party leader, the ability to vote for that leader increases the likelihood of casting a preference vote by close to 30 percentage points compared to voters also holding high party leader sympathy but without possibility to express this support as the party leader does not run in the district. In sum, the analysis supports the hypothesis that voters most supportive of their party leader are the ones most affected by the ability to vote for the party leader or not.

The third hypothesis (H3) stated that in contrast to party leader sympathy, party belonging should weaken the positive relationship between casting a preference vote and voting in a district where the party leader runs. Model 3 in includes the relevant interaction term between being a party supporter and being able to vote for the preferred party’s leader. The coefficient is positive and non-significant. illustrates the marginal effect of the party leader running in the district on the likelihood of casting a preference vote across party supporters and non-party supporters. The effects are very similar (0.27), and the confidence intervals clearly overlap. The hypothesis is, therefore, not supported. Being a party supporter does not weaken the relationship between casting a preference vote and voting in a party leader district. Model 1 shows that party supporters are generally more likely to cast a preference vote, which suggests that the main mechanism is not that party supporters are collectively oriented, preferring to vote for the party list, but rather that party supporters are more sophisticated voters who are more likely to select a candidate even if the party leader is not running in the district compared to non-party supporters.

Figure 4. Marginal effect of party leader running on list across voters supporting specific party or not (H3).

Finally, the fourth hypothesis (H4) moves from the voter to the party leader level as it states that leaders that are more polarizing will be more likely to activate the compensational list vote for voters’ who cannot support their party leader personally. As demonstrated in , Inger Støjberg, leader of the new party Danish Democrats – Inger Støjberg, is the most popular among her own party voters. Alex Vanopslagh (Liberal Alliance) comes in second, while Mette Frederiksen (Social Democrats and prime minister) is third. Some party leaders are not very popular even among their own party voters. Particularly the leader of the Social Liberals, Sofie Carsten-Nielsen, faces relatively low sympathy among party voters. With regard to polarization, there is a clear pattern for more extreme left- or right-leaning parties to have leaders that are more polarizing, while more moderate parties have leaders that are less polarizing. This is thus not only a trait of party leaders but also related to the party policy. However, even among more extreme parties, leader polarization varies. Especially, Inger Støjberg and Morten Messerschmidt polarize the voters. Both have been connected to illegal practices as politicians and ministers besides representing extreme policy positions regarding immigration.

In , Model 4 includes the relevant interaction term to test the hypothesis. The coefficient is positive and statistically significant in accordance with the hypothesis. illustrates the marginal effect of being able to vote for the preferred party leader on casting a preference vote across different levels of leader polarization.Footnote48 The effect is significantly different from zero across all levels of party leader polarization. Even for the least polarizing leader (Sofie Carsten-Nielsen), the ability to vote for the party leader increases the likelihood of casting a preference vote. However, the relationship is stronger for leaders that are more polarizing. For the lowest level of leader polarization, the likelihood of casting a preference vote is increased by 13 percentage points if the leader is running in the district. For the highest level of leader polarization, the likelihood is increased by 43 percentage points – a substantial difference of 30 percentage points.

Conclusion

Our research departed from two questions: (1) Can institutions contain personalization limiting the spillover from one arena to another? (2) Do voters find alternative ways to express personalized preferences, and if so, which voters are most likely to use such compensational, personalized voting strategies?

Our theoretical answers were the following: (1) Yes, institutions could limit actors in one arena to respond to personalized behaviour of actors in another arena. Specifically, electoral rules allowing candidates to run in only one out of multiple electoral districts limit voters’ opportunity to respond to national, personalized campaigns of prominent candidates. (2) Yes, voters should turn towards compensational list voting, expressing personalized political preferences by supporting the party of their preferred party leader rather than alternative candidates, and particularly voters with strong party leader sympathy, low party identification, and supporting polarizing party leaders should use such compensational voting strategies.

Our empirical results align with the theoretical ideas: (1) The share of preference votes was significantly higher in districts with the party leader running. The number of preference votes would most likely have been higher had electoral rules allowed voters to vote for the preferred party leader in all districts as such direct expressions of personalized voting was constrained by electoral institutions. (2) Voters were less likely to cast a preference vote in districts where the preferred party leader was not running and particularly so if they have high sympathy with their party leader and this leader polarizes voters. As such, voters can be perceived as using list votes as a compensation strategy. The usage of compensational voting is not moderated by party identification as suggested by our theoretical argument.

In sum, the study supports the idea of compensational list voting, indicating that voters find ways to best express their party leader loyalty even when electoral systems are designed to foster district-level, intra-party competition. On the one hand, political institutions may, thus, constrain tendencies to centralize personalization as party leaders cannot sweep up all possible personal votes. The share of party list votes remains high due to personalized, compensational list voting among voters in districts where the preferred party leader is not running. On the other hand, the difference between preference votes for the party leader and for other candidates increases with compensational list votes, though prominent politicians besides party leaders also have opportunities to build their personal electoral base.Footnote49 As such, political institutions do not limit the personalization of parties as expressed by the concentration of electoral power of the party leader.Footnote50

This points to the importance of the analytical distinction between centralized and decentralized personalization in the electoral arena. While electoral systems such as the PR list system with optional preferential votes allowing party leaders to run in only one district contain total centralized personalization, they can also contain decentralized personalization. This is unintentional since the original intention is to support geographical representativeness. In situations where strong party leaders are personalizing politics, this can lead to an increase in centralized electoral personalization in the districts where they run while simultaneously leading to a decrease in decentralized electoral personalization in all other districts. High-profile party leaders can lead to less preference votes and thereby to signals of decreased electoral personalization, while personalized electoral behaviour is – in reality – increasing through compensational list voting. Therefore, the true paradox of the 2022 Danish elections was not that a personalized campaign was accompanied by a decrease in preferential votes but that the decrease in preferential votes was actually a sign of increasing centralized personalization.

Political institutions may, thus, limit the expression of personalized politics but perhaps not the intensity of personalized politics. This has important implications for party democracy. First, the “hidden” personalization brought about by the personalization constraints of the electoral system make the electoral power base of party leaders less evident. Hereby, centralized personalization of political parties may be kept in check as party leaders cannot directly show how they carried most of the votes. Second, the compensational list vote indicates that electoral systems limit voters’ ability to express their vote preferences as precisely as possible. Given the nationwide campaign, voters may feel led astray and frustrated at not being able to express preferences for their party leader. This limitation was never stated as the intention of the electoral system and is debatable given the personalized character of campaigns and campaign coverage. However, voters seem to navigate this limitation smoothly, connecting party and party leader in their vote and hereby mixing collective and personal vote orientations, resulting in the same overall electoral results.

Our general result of more preference votes in districts running party leaders replicates findings from Belgium and thus increases the external validity of this pattern.Footnote51 Further, we have theorized and tested observable implications of the compensational list vote mechanism. Two of the implications are supported: voters with stronger likes and preferring party leaders that are more polarizing are more likely to cast a list vote when unable to vote for their preferred party leader. The third implication is not supported as feelings of belonging to a party do not weaken the negative relationship between casting a preference vote and not being able to vote for the relevant party leader. Thus, there is room for further theorizing and exploration of the mechanism offering a better understanding of the meaning of a list vote inside or outside party leader districts and of the potential voter frustrations of not being able to express personalized support.

We will close this article by returning to one of the examples from the Danish 2022 elections described in the introduction, namely the party the Danish Democrats – Inger Støjberg, which as a newcomer included the name of the party leader in its name, and therefore, Inger Støjberg was “on the ballot” in the entire country and not only in one of the 10 constituencies like the remaining 13 party leaders. While the electoral system contains the decentralized personalization, the article has demonstrated that we are not equally convinced that the voting motives are more generally contained by the electoral institutions. And if some parties would challenge the institutions and circumvent the containment of personalization by including the party leader’s name in the party name, another part of the institutional set-up makes this possible since the rules for getting the name of a party accepted is quite liberal in Denmark. This also means that the Danish Democrats – Inger Støjberg will be the party name on the ballot when the election for the European Parliament is held in Denmark on 9 June 2024 – an election where party leader Inger Støjberg is not running as a candidate but where she, contrary to the other party leaders, will have her name listed on the ballot as part of the party name. This is a kind of inter-level personalization not seen before in Denmark.

Ethical declaration

The analyses are based on anonymized survey answers from adult Danish voters. The data is collected and made available by the Danish National Election Study https://www.valgprojektet.dk/pages/page.asp?pid=308&l=eng. The documentary report includes invitation material sent to participants. The invitation contains detailed information about (1) the purpose of the study, (2) the researchers behind the study, (3) the data responsible institution, (4) the survey agency, (5) the rules and rights regarding participation, and (6) description of how data will be used in publications. Data is therefore collected based on informed consent. The data collection has received GDPR-approval by Copenhagen University (reference number: 514-0051/18-2000). The data collection is not approved by an institutional review board as this is not required in Danish political science. Given the anonymized version used for this study and the detailed information provided to participants, we believe that all relevant ethical considerations are met.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank the conveners of this special issue for initiating the collaboration and providing valuable comments on earlier versions of the paper. We also thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for helpful and encouraging comments. Finally, we thank Professor Rune Stubager and Professor Kasper Møller Hansen for collecting, organising, and sharing the anonymous survey data from https://www.valgprojektet.dk/default.asp?l=engThe Danish National Election Study without which this study was not possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Helene Helboe Pedersen

Helene Helboe Pedersen is a professor at the Department of Political Science at Aarhus University. Her research focuses on political representation, including the organization of political parties, parliamentary institutions, the influence of interest organizations, and the behaviour of politicians. She leads a project on politicians' task priority and working conditions.

Ulrik Kjær

Ulrik Kjær is a professor at the Department of Political Science at the University of Southern Denmark. His research focuses on political leadership, political elites, elections, party systems, gender, and local democracy. He leads the Danish Municipal Election Study.

Notes

1 Rahat, “Party Types”; Frantz et al., “Personalist Ruling Parties.”

2 Pedersen and Kjær, “Et Personligt Valg.”

3 Hansen et al., “Kandidaternes Kampagner.”

4 Rahat and Sheafer, “The Personalization(s) of Politics”; Karvonen, The Personalisation of Politics; Balmas et al., “Two Routes to Personalized Politics.”

5 Balmas et al., “Two Routes to Personalized Politics.”

6 Ibid.

7 Rahat and Sheafer, “The Personalization(s) of Politics.”

8 Pedersen “Personalisation and Political Parties.”

9 Rahat and Kenig, “From Party Politics to Personalized Politics?”

10 Renwick and Pilet, “Faces on the Ballot.”

11 Wauters et al., “Centralized Personalization.”

12 Ferreira da Silva et al., “From Party to Leader Mobilization?”

13 Wauters et al., “Centralized Personalization.”

14 Pedersen and Kjær, “Et Personaliseret Valg.”

15 Frantz et al., “Personalist Ruling Parties.”

16 Pedersen and Rahat, “Political Personalization and Personalized Politics”; Karvonen, “The Personalisation of Politics.”

17 Rahat and Sheafer, “The Personalization(s) of Politics.”

18 Caiani et al., “Candidate Selection, Personalization and Different Logics”; Önnudóttir, “Political Parties and Styles”; Bøggild and Pedersen, “Campaigning on Behalf of the Party?”

19 Gallagher and Mitchell, The Politics of Electoral Systems.

20 Cain et al., The Personal Vote; Viganó, “Electoral Incentives and Geographical Representation”; Crisp et al., “Vote-Seeking Incentives and Legislative Representation.”

21 Bøggild et al., “Which Personality Fits Personalized Representation?”

22 E.g., Carey and Shugart, “Incentives to Cultivate a Personal Vote”; André et al., “Electoral Rules and Legislators’ Personal Vote-Seeking”, Pedersen and van Heerde, “Two Strategies for Building a Personal Vote”; Zittel and Gschwend, “Individualised Constituency Campaigns.”

23 See, however, Dodeigne and Pilet, “Centralized or Decentralized Personalization?”

24 Andre et al. “The Nature of Preference Voting”

25 Rahat, “Party Types in the Age of Personalized Politics.”

26 Wauters et al., “Centralized Personalization.”

27 Takens et al., “Party Leaders in the Media.”

28 Andrews and Jackman, “If Winning Isn’t Everything, Why Do They Keep Score?”; Ennser-Jedenastik and Schumacher, “What Parties Want from Their Leaders.”

29 Wauters et al., “Centralized Personalization.”

30 Balmas et al., “Two Routes to Personalized Politics”; Rahat and Sheafer, “The Personalization(s) of Politics”; Pedersen and Rahat, “Political Personalization and Personalized Politics.”

31 Wauters et al., “Centralized Personalization.”

32 Dodeigne and Pilet, “It’s not Only About the Leader.”

33 Garzia et al., “Partisan Dealignment and the Personalisation of Politics.”

34 Reiljan et al., “Patterns of Affective Polarization.”

35 Wauters et al., “Centralized Personalization”, 520.

36 André et al., “Electoral Rules and Legislators’ Personal Vote-Seeking”, 89.

37 Pedersen and Kjær, “Et Personaliseret Valg”

38 The model is estimated with election as unit of analysis (N = 15). The time coefficient is positive and significant (0.17, p = 0.005). The reform dummy indicating whether the election took place before or after the reform is positive as expected but not statistically significant (p = 0.14). The coefficients of the number of parties (hence also party leaders) running for election, and the total number of valid votes are not statistically significant (p = 0.37–0.85).

39 Hansen and Stubager, The Danish National Election Study 2022.

40 Ibid.

41 The variable is measured using the question: “Did you cast a personal vote at the general election November 1st, 2022?” Respondents indicating “Yes, for a man” or “Yes, for a woman” were coded as Yes (1), while respondents indicating “No, I did not cast a personal vote” or “Don’t know” were coded No (0).

42 We refrain from describing this as party identification as we do not capture all aspects of the concept; Huddy et al., “Expressive Partisanship.”

43 These terms are difficult to translate as they indicate names of supporters of specific parties. Radikal refers to voters supporting the Social Liberals, venstremand refers to voters supporting the liberal party Venstre, and SF’er refers to voters supporting the Socialist People’s Party (SF).

44 The measure of sex is based on register data and supplied in the survey dataset. The survey also includes a question of gender. Only 14 respondents indicated to identify themselves neither as female nor male.

45 See also Hansen and Stubager, The Danish National Election Study 2022, 12.

46 Dodeigne and Pilet, “It’s not Only About the Leader.”

47 Pedersen and Kjær, “Et Personligt Valg.”

48 Ibid.

49 Ibid.

50 Rahat, “Party Types”; Poguntke and Webb, The Presidentialization of Politics.

51 Wauters et al., “Centralized Personalization.”

Bibliography

- André, Audrey, Sam Depauw, and Jean-Benoit Pilet. “The Nature of Preference Voting: Disentangling the Party and Personal Components of Candidate Choice.” In Mind the Gap. Political Participation and Representation in Belgium, edited by K. Deschouwer, 251–274. Colchester: ECPR Press / Rowman & Littlefield International, 2017.

- André, A., A. Freire, and Z. Papp. “Electoral Rules and Legislators’ Personal Vote-Seeking.” In Representing the People: A Survey Among Members of Statewide and Substate Parliaments, edited by K. Deschouwer and S. Depauw, 87–109. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Andrews, J. T., and R. W. Jackman. “If Winning Isn’t Everything,: Why Do They Keep Score? Consequences of Electoral Performance for Party Leaders.” British Journal of Political Science 38, no. 4 (2008): 657–675.

- Balmas, M., G. Rahat, T. Sheafer, and S. R. Shenhav. “Two Routes to Personalized Politics: Centralized and Decentralized Personalization.” Party Politics 20, no. 1 (2014): 37–51.

- Bøggild, T., R. Campbell, M. K. Nielsen, H. H. Pedersen, and J. A. VanHeerde-Hudson. “Which Personality Fits Personalized Representation?” Party Politics 27, no. 2 (2021): 269–281.

- Bøggild, T., and H. H. Pedersen. “Campaigning on Behalf of the Party? Party Constraints on Candidate Campaign Personalisation.” European Journal of Political Research 57, no. 4 (2018): 883–899.

- Caiani, M., E. Padoan, and B. Marino. “Candidate Selection,: Personalization and Different Logics of Centralization in New Southern European Populism: The Cases of Podemos and the M5S.” Government and Opposition 57, no. 3 (2022): 404–427.

- Cain, B., J. Ferejohn, and M. Fiorina. The Personal Vote: Constituency Service and Electoral Independence. Harvard University Press, 1987.

- Carey, J. M., and M. S. Shugart. “Incentives to Cultivate a Personal Vote: A Rank Ordering of Electoral Formulas.” Electoral Studies 14, no. 4 (1995): 417–439.

- Crisp, B. F., M. C. Escobar-Lemmon, B. S. Jones, M. P. Jones, and M. M. Taylor-Robinson. “Vote-Seeking Incentives and Legislative Representation in Six Presidential Democracies.” The Journal of Politics 66, no. 3 (2004): 823–846.

- Dodeigne, J., and J. B. Pilet. “Centralized or Decentralized Personalization? Measuring Intra-Party Competition in Open and Flexible List PR Systems.” Party Politics 27, no. 2 (2021): 234–245.

- Dodeigne, J., and J. B. Pilet. “It’s Not Only About the Leader: Oligarchized Personalization and Preference Voting in Belgium.” Party Politics 30, no. 1 (2024): 24–36.

- Ennser-Jedenastik, L., and G. Schumacher. “What Parties Want from Their Leaders: How Office Achievement Trumps Electoral Performance as a Driver of Party Leader Survival.” European Journal of Political Research 60, no. 1 (2021): 114–130.

- Ferreira da Silva, F., D. Garzia, and A. De Angelis. “From Party to Leader Mobilization? The Personalization of Voter Turnout.” Party Politics 27, no. 2 (2021): 220–233.

- Frantz, E., A. Kendall-Taylor, J. Li, and J. Wright. “Personalist Ruling Parties in Democracies.” Democratization 29, no. 5 (2022): 918–938.

- Gallagher, M., and P. Mitchell, eds. The Politics of Electoral Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Garzia, D., F. Ferreira da Silva, and A. De Angelis. “Partisan Dealignment and the Personalisation of Politics in West European Parliamentary Democracies, 1961–2018.” West European Politics 45, no. 2 (2022): 311–334.

- Hansen, K. M., K. Kosiara-Pedersen, and H. H. Pedersen. “Kandidaternes kampagner og betydning for de personlige stemmetal.” In Partiledernes kamp om midten. Folketingsvalget 2022, edited by K. M. Hansen and R. Stubager. Copenhagen: Jurist- og Økonomforbundets Forlag, 2024.

- Hansen, K. M., and R. Stubager. “The Danish National Election Study 2022.” CVAP Working Paper Series no. 3/2023. Copenhagen: Centre for Voting and Parties, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Copenhagen, 2023.

- Huddy, L., L. Mason, and L. Aarøe. “Expressive Partisanship: Campaign Involvement, Political Emotion, and Partisan Identity.” American Political Science Review 109, no. 1 (2015): 1–17.

- Karvonen, L. The Personalisation of Politics: A Study of Parliamentary Democracies. Colchester: ECPR Press, 2010.

- Önnudóttir, E. H. “Political Parties and Styles of Representation.” Party Politics 22, no. 6 (2014): 732–745.

- Pedersen, H. H. “Personalisation and Political Parties.” In The Routledge Handbook of Political Parties, edited by N. Carter, D. Keith, S. Vasilopoulou, and G. Sindre, 254–265. London: Routledge, 2023.

- Pedersen, H. H., and U. Kjær. “Et Personligt Valg.” In Partiernes kamp om midten. Folketingsvalget, edited by K. M. Hansen, and R. Stubager. Copenhagen: Djøf Forlag, 2022.

- Pedersen, H. H., and G. Rahat. “Political Personalization and Personalized Politics Within and Beyond the Behavioral Arena.” Party Politics 27, no. 2 (2021): 211–219.

- Pedersen, H. H., and J. vanHeerde-Hudson. “Two Strategies for Building a Personal Vote: Personalized Representation in the UK and Denmark.” Electoral Studies 59 (2019): 17–26.

- Poguntke, T., and P. Webb, eds. The Presidentialization of Politics: A Comparative Study of Modern Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005

- Rahat, G. “Party Types in the Age of Personalized Politics.” Perspectives on Politics 22, no. 1 (2024): 213–228.

- Rahat, G., and O. Kenig. From Party Politics to Personalized Politics?: Party Change and Political Personalization in Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Rahat, G., and T. Sheafer. “The Personalization (s) of Politics: Israel, 1949–2003.” Political Communication 24, no. 1 (2007): 65–80.

- Reiljan, A., D. Garzia, F. F. Da Silva, and A. H. Trechsel. “Patterns of Affective Polarization Toward Parties and Leaders Across the Democratic World.” American Political Science Review 118, no. 2 (2024): 654–670.

- Renwick, A., and J. B. Pilet. Faces on the Ballot: The Personalization of Electoral Systems in Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Takens, J., J. Kleinnijenhuis, A. Van Hoof, and W. Van Atteveldt. “Party Leaders in the Media and Voting Behavior: Priming Rather Than Learning or Projection.” Political Communication 32, no. 2 (2015): 249–267.

- Viganò, E. A. “Electoral Incentives and Geographical Representation: Evidence from an Italian Electoral Reform.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 49, no. 2 (2024): 257–287.

- Wauters, B., P. Thijssen, P. Van Aelst, and J. B. Pilet. “Centralized Personalization at the Expense of Decentralized Personalization. The Decline of Preferential Voting in Belgium (2003–2014).” Party Politics 24, no. 5 (2018): 511–523.

- Zittel, T., and T. Gschwend. “Individualised Constituency Campaigns in Mixed-Member Electoral Systems: Candidates in the 2005 German Elections.” West European Politics 31, no. 5 (2008): 978–1003.