Abstract

In 2013, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) agreed to carry out a regional assessment for Africa. Since then, roughly 100 authors have been working to deliver, in 2018, a document that not only synthesises existing knowledge on biodiversity and ecosystem services for the African region but to distil from it knowledge that is relevant, credible, and legitimate for both societal and scientific practise. This requires, firstly, to carefully constituting the group of authors and, secondly, to design an assessment process that allows for deriving at an integrated perspective amongst these experts. Such a joint process of knowledge production that encompasses both interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary collaboration can be framed as co-creation. In this contribution, we analyse whether the IPBES African assessment accounts for these two prerequisites for an effective assessment process. Our particular interest lays in the question whether scholars from social sciences and the humanities are sufficiently involved. Our analysis is based on the curriculum vitae of 97 members of the expert group, and reads quite straightforward: there is an overall lack of non-natural science perspectives and expertise that might lead to essential knowledge and data gaps when wishing to understand the effects of the diverse human concepts of and activities on biodiversity and ecosystem services. In order to address these gaps and to derive at an assessment report truly relevant for policy makers as well as other social and scientific actors, IPBES needs to widen its outreach to networks of scholars from the social sciences and the humanities and to inform them appropriately about the specific roles they could play within IPBES processes, particularly assessments.

1. Introduction

At its second plenary, held in Turkey in December 2013 (IPBES-2), IPBES agreed to carry out a regional assessment for AfricaFootnote1 and subsequently, in 2014, invited experts on the region to join a working group and share their expertise. Since then, roughly 100 authors have been working to deliver, in 2018, a document that synthesises the existing knowledge on biodiversity and ecosystem services for the African region and derived from it policy options for governments and other end users (IPBES/Citation3/Citation6/Add.Citation1 Citation2014). The goal of this assessment is not only to bring together experts and knowledge and, by doing so, to strengthen the biodiversity science-policy interface in the region. The ultimate objective of this exercise is to distil from it knowledge that is relevant, credible, and legitimate for both societal and scientific practice, describing the three key characteristics of effective science-policy processes (Heink et al. Citation2014; Koetz, Farrell, and Bridgewater Citation2012). “Support[ing] policy formulation and implementation by identifying policy-relevant tools and methodologies, such as those arising from assessments” is one of the four explicit functions of IPBES as agreed in the Busan Outcome (UNEP/IPBES/Citation3/INF/Citation1/Add.Citation1 Citation2010).Footnote2

However, to achieve the latter is more than challenging. What became clear from previous global assessments on biodiversity and ecosystems, such as the Global Biodiversity Assessment (GBA) and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MA), as well as from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), is that simply pooling together the state-of-the-art of natural sciences knowledge on biodiversity status and trends no longer proofs sufficient to appropriately inform biodiversity governance (Perrings et al. Citation2011). The rationale behind that is that biodiversity and ecosystem services are considered typical boundary objects dealt with by a great plurality of different scientific disciplines and knowledge systems, including their underlying worldviews and often dynamic values (Spierenburg Citation2012). Furthermore, biodiversity is highly context dependent, both with regard to biophysical factors such as geographic, climatic and time scales, and social-cultural, political and economic factors. Eventually, this means that “natural sciences should no longer dictate the Earth system research agenda” as Reid and colleagues phrased it (Citation2009, p. 245).

For carrying out an assessment on biodiversity within a global science-policy process this means, firstly, to carefully composing the expert groups in charge of pulling together this knowledge. Thus, from the outset, IPBES opened up its assessment processes to disciplines beyond the natural sciences world alone. Within its guiding principles it embraced an interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary approach, including social and natural sciences, and striving for gender and regional balance. This also accounts for societal actors outside the academic world: “Improving the involvement of appropriate stakeholders at all assessment stages would be a valuable contribution to developing and communicating key messages and increasing a sense of ownership and understanding.”Footnote3

Scholars particularly trained in, amongst others, political sciences, social and public policy, sociology, law, and economics – or new interdisciplinary fields emerging from them, such as political ecology or ecological economics – will be of major importance to acknowledge and engage with the political aspects of biodiversity policy (Spierenburg Citation2012). As Briggs states it (Citation2011)

Undoubtedly, IPBES will contribute to global understanding of biodiversity and ecosystem services, but the effectiveness of the Platform in operating across the science-policy interface will depend on how well the scientists associated with IPBES understand the nature of policy. (pp. 696–697).

It furthermore means to align such assessments to the different scales global biodiversity change may impact on: local, national, regional, and global (Perrings et al. Citation2011). Accordingly, the Busan Outcome reads as “the new platform should identify and prioritize key scientific information needed for policymakers at appropriate scales” (UNEP Citation2010). That is, IPBES authors need to critically review who exactly the policy makers/end users are they want to address and if the products of the assessment processes truly serve their needs. Furthermore, scholars specifically looking at regional and local characteristics with regards to the use, valuation and governance of BES, and embedded differences related to gender, culture and socio-economic characteristics of their users, amongst others, will become crucial to analyse in which ways policy could adequately influence resource use in such specific contexts. This also holds true for the appropriate inclusion of indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) about and generated in specific local contexts, complementing scientific knowledge. Again, this is a field originally addressed by social sciences and humanities and their interdisciplinary, often more holistic perceptions of generating knowledge.

However, when looking at the current composition of IPBES subsidiary bodies, it becomes clear, that IPBES still lacks an adequate representation of non-natural sciences disciplines as well as other stakeholders. For example, the Multidisciplinary Expert Panel (MEP), which governs the composition of assessment expert groups and tasks forces. Even after two rounds of election in 2013 and 2015, the MEP has failed to live up to its name. The MEP is still dominated by male natural scientists; social sciences and the humanities (SSH) and indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) are greatly under-represented, as are representatives of Eastern Europe; and only 36% of MEP members are women. Moreover, ILK is represented by natural scientists holding expertise in working with local communities rather than by members of such communities. Even if slight progress can be observed between the first and the second round of elections, i.e. the share of non-natural scientists increased from 16% to 24%, there is still much room for improvement (Montana and Borie Citation2015).

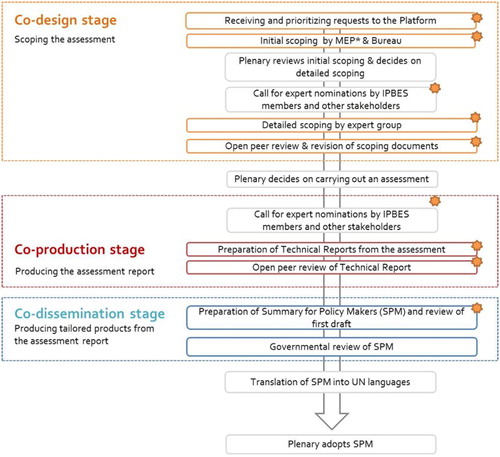

Next to establishing a working group with balanced expertise and stakeholder representation it is, secondly, essential to design an assessment process that truly allows for deriving at an integrated perspective on biodiversity and ecosystem services amongst these experts. Such a joint process of knowledge production that encompasses both interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary collaboration can be framed as co-creation (Mauser et al. Citation2013), a conceptual model that was proposed for the Future Earth processFootnote4 and is rooted in earlier concepts on knowledge integration (e.g. Jahn, Bergmann, and Keil Citation2012; Lang et al. Citation2012; Tress, Tress, and Fry Citation2005). The framework consists of three consecutive steps: co-design, co-production and co-dissemination. Co-design is characterised by a joint framing of the societal problem by all relevant scientific and non-scientific actors resulting in a common research object, i.e. the knowledge needed to address this problem, and a corresponding research agenda. In the co-production step, the research object is broken down into single questions to be tackled by disciplinary scholars and/or interdisciplinary teams, and the answers gained by these scholars subsequently integrated – in tight collaboration with the societal actors. Subsequently, this new knowledge is assessed with respect to its possible contributions to the initial societal problem and scientific questions, forming the basis to draft recommendations for courses of actions appropriate to address them (e.g. formulation of strategies, policies, or knowledge needs), i.e. the production of “knowledge for practice” and “knowledge for science” (Bergmann et al. Citation2012). Lastly, co-dissemination refers to the appropriate formulation and translation into knowledge products appropriate for specific audiences and their publication/circulation (Mauser et al. Citation2013).

In this contribution, we analyse whether the IPBES regional assessment for Africa is accounting for these two prerequisites for an effective assessment process as identified above. That is, firstly, we investigate whether the composition of the group of authors, by looking at its interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary balance (involvement of non-scientific actors), as well as gender and regional constitution. Our particular interest lays in the question whether scholars from social sciences and the humanities are sufficiently involved in the assessment. Secondly, using the concept of co-creation as a methodological framework, we examine the process of the assessment to deduce which specific roles scholars from the social sciences and the humanities could play within it, and at which levels of the process they would add most value.Footnote5

Our analysis is based on the curriculum vitae of 97 members of the expert group, which attended the First Author Meeting for the assessment. Access to these documents was possible given that the authors of this contribution are members of the expert group and took part in the First Author Meeting where the CVs of the authors were shared among the participants.

In the following section we, first of all, apply the co-creation framework onto a typical assessment process in IPBES which also applies to the African assessment. We provide descriptions of the individual assessment steps and identify entry points for stakeholders. Secondly, we analyse the composition of the expert group undertaking the assessment in terms of its regional (with regards to the representation of African subregions) and gender, as well as disciplinary balance. On the basis of our results we, thirdly, outline specific roles for scholars from the social sciences and the humanities within the African assessment, and conclude with some ideas how to practically increase their involvement in IPBES (assessment) processes.

2. Co-creation in IPBES assessment processes and entry points for stakeholders

shows how we applied the three co-production steps as described above on the IPBES assessment process (as described in IPBES/Citation4/INF/Citation9 Citation2016, p. 41ff), and marked possible entry points for stakeholders,Footnote6 i.e. divers knowledge holders.

Figure 1. Co-creation in IPBES assessment processes, as described by IPBES’ rules and procedures (see IPBES/Citation2/Citation17 Citation2014), consists of three steps (the orange stars mark entry points for stakeholders). The scoping of the assessment correlates to the co-design step; the undertaking of the assessment and the actual writing of the assessment report equates to the co-production step; and finally the preparation of the Summary for Policy Makers (SPM) represents a first product distilled from the assessment which is tailored to the needs of particular stakeholders – in this case policy makers. The production of further products tailored to the needs of other end users of the assessments is not intended in the context of IPBES assessment processes. Here is a great need to further develop the co-dissemination step – and a particular good additional entry point for stakeholders. (*The MEP is selected by the Plenary by consensus from the nominations received from IPBES member states which can comprise of both government and stakeholder representatives, as described in IPBES/Citation2/Citation17 Citation2014).

2.1. Co-design step: scoping the assessment

The co-design step then comprises the (i) joint identification of topics to be addressed by IPBES assessments and (ii) related scoping processes. The topics addressed by the IPBES work programme result from the requests put to the Platform by its member states and other governments, multilateral agreements, United Nations institutions, and other relevant stakeholders. These requests are collected by the IPBES secretariat and subsequently screened and prioritised in collaboration with the MEP and the BureauFootnote7 who also carry out an initial scoping of the feasibility of undertaking an assessment. Based on this initial scoping, the MEP and Bureau will prepare a prioritised list of requested assessments to be submitted to the IPBES Plenary, which then identifies and decides on a set of topics that could finally be addressed. However, before the final decision to effectively carry out an assessment on a particular topic, the Plenary will request a detailed scoping for it,Footnote8 for which the MEP will establish an expert group based on nominations by member states and other stakeholders. This detailed scoping aims at determining the need and rationale for an assessment, and identifies its key policy questions and objectives. It furthermore identifies the information, and the human and financial requirements needed to achieve the objectives and evaluates the actual availability of these resources. Already at this stage, the expert group is requested to consider possible knowledge gaps, as well as consider how to mobilise relevant ILK holders and other possible contributors outside the academic world. The scoping report will subsequently be open for review by IPBES members and other stakeholders and its revised version serves as the basis for decision by the Plenary whether to carry out an assessment or not.

Entry points for stakeholders during the co-design step comprise: (i) submitting request to the Platform (as an institution), (ii) participating in the initial scoping as member of the MEP (when selected), (iii) taking part in the call for nomination and subsequently being selected as (iv) member of the scoping expert group, and finally (v) engaging in the review of the scoping document.

2.2. Co-production step: undertaking the assessment and producing the assessment report

The co-production step of the IPBES assessment process encompasses undertaking the assessment of a particular topic (searching the knowledge base) and preparing a technical report on its findings. Report writing and the review of reports (First-Order Drafts – FOD, Second-Order Drafts – SOD) are iterative processes that can last between one (fast-track assessment) and three (standard assessment) years. The assessment and the report writing are carried out by an expert group, selected by the MEP from the nominations received, in which authors have different roles: Co-chair, Coordinating Lead Authors, Lead Authors, Contributing Authors, Review Editors, and Expert Reviewers. In these different roles are explained in more detail. The review of the two versions of the assessment report is again open to all stakeholders.

Table 1. Possible roles experts can play within the IPBES assessment process (Modified after IPBES/Citation4/INF/Citation9 Citation2016, .1, p: 45).

The authors undertaking the assessment were selected in accordance to the criteria set out in the procedures for the preparation of the Platform’s deliverables in the annex to decision IPBES-2/3. Based on both the nomination templates (nominees had to fill in an online template in order to apply as author) and curriculum vitaes received from the candidates, the MEP selected the experts based on the relevance of their expertise is with regard to the topics to be addressed by and the role to be fulfilled within the assessment process. Within this selection process, the MEP tried to balance disciplinary, gender and regional diversity (IPBES/Citation4/INF/Citation10 Citation2015). In general, selected experts contribute to the assessment pro bono and need to cover their possible expenses related to their work for IPBES (e.g. travel costs) by their own budgets. Excluded from this rule are authors from developing countries who receive reimbursement of their travel expenses and daily allowances from the IPBES Trust Fund.

Entry points for stakeholders during the co-production step comprise: (i) taking part in the call for nomination and subsequently being selected as (ii) member of the expert group, and (iii) engaging in the review of the technical reports.

2.3. Co-dissemination step: producing tailored products from the assessment report

The final stage of the co-production process is the co-dissemination step, i.e. producing tailored products from the assessment report. The Summary for Policy Makers (SPM) represents a first product distilled from the assessment report which is tailored to the needs of particular stakeholders – in this case policy makers. However, other tailored products resulting from what is described as “transdisciplinary integration” by Jahn, Bergmann, and Keil (Citation2012) as mentioned above, i.e. evaluating the possible contributions of the assessment process for both the societal and the scientific practice, are not intended so far in the IPBES assessment processes.

So far, the entry points for stakeholders in the co-dissemination step comprise: (i) being member of the expert group drafting the SPM and (ii) review of the first draft of the SPM. The review of the second and final draft of the SPM is restricted to governments only. However, but more informally, individuals always can engage as facilitators who help to disseminate and transfer the final deliverables of IPBES, support its capacity building activities and activate other relevant stakeholders and their networks to broaden the expertise assembled under IPBES.

The final version of the SPM will be translated into the six official UN languages (while the technical report is not which is written in English) and submitted to the upcoming IPBES plenary for approval and adoption.

3. Co-creation in the IPBES regional assessment for Africa

3.1. Co-design step

The decision to undertake a Regional Assessment for Africa as one of four regional assessmentsFootnote9 was taken by the second plenary of IPBES (IPBES-2) in December 2013 (decision IPBES/2-5). As such it was a joint decision of 119 governments which were IPBES members back then (today IPBES counts 127 member states), based on the prioritised list of requests to the Platform published prior by the Multidisciplinary Expert Panel (MEP). The subsequent scoping was carried out jointly for all four regional assessments to support coherence across them and facilitate their integration into the global assessment of IPBES. Accordingly, based on a call for nominations, the scoping expert group was constituted by experts with a great range of expertise from all UN regions, of which approximately 68% were representatives of governments (48 countries) and 32% of other institutions (scientific, non-governmental, intergovernmental, national, private), who met at a workshop in 2014 in Paris.Footnote10 It resulted in a generic scoping report that addresses (i) the scope, rationale, utility and assumptions, (ii) the chapter outline, (iii) the key datasets, (iv) the operational structure, (v) strategic partnerships, (vi) the process and timetable, (vii) the cost estimate, (viii) the communication and outreach, and (ix) the capacity building valid for each of the regional assessments (IPBES/Citation3/Citation6/Add.Citation1 Citation2014). In January 2015, IPBES-3 approved the scoping document which marked the official start of the assessment. Given the collaborative and multidisciplinary character of this scoping process we can speak of a co-designed agenda within the meaning of our previous definition.

3.2. Co-production step

After the scoping document had been approved, the IPBES Secretariat launched a second call for nominations in 2015, this time for the expert group to undertake the assessment and prepare the final reports. The selected experts convened at the First Author Meeting of the IPBES Regional Assessment for Africa held 2–6 August 2015 in Pretoria, South Africa, with the objective to detail the generic chapter outline for the African regional and subregional contexts, and to allocate responsibilities among the authors, with respect to their roles within the assessment process (see ). The resulting document, the so-called Zero-Order Draft (ZOD) of the assessment, contained a detailed table of contents and brief descriptions of the objectives of each of its chapters, which was later revised by the assessment Co-chairs. The authors were then invited to submit their texts according to their assignments to produce the First-Order-Draft (FOD). This document was the first official draft to undergo an external review by all interested experts. It took place 30 May to 18 July 2016. Subsequently, the authors addressed the reviewers’ comments. Further advancing the report, the co-chairs, coordinating lead authors, and review editors gathered for a second author meeting from 22–26 August 2016 in Bonn, Germany. The subsequent document, the Second-Order Draft of the assessment report (SOD) was open for review from 1 May to 26 June 2017. The comments received were addressed individually by the authors and during the third author meeting held from 7 to 12 August 2017 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The final draft of the assessment report and its Summary for Policymaker (SPM) will be presented to the upcoming sixth plenary of IPBES (IPBES-6) in March 2018.

In the following, we present the findings of our analysis of the composition of the expert group which is based on the self-written curricula vitae of the authors as provided during the First Author Meeting The CVs provided information on (in slightly varying order) (i) personal data (name, date and place of birth, nationality, marital status, languages spoken, contact details), (ii) education (completed studies and graduation, post-graduate studies), (iii) practical experiences (career stages, former and recent positions and responsibilities), (iv) research experience, (v) advanced training (trainings, seminars, workshops, courses, etc.), (vi) participation in and contribution to national and/or international scientific conferences (talks, poster presentations, sessions etc.), (vii) membership in scientific bodies, boards, committees, societies and networks (scientific, technical, political, etc.), (viii) publications, and (ix) referees. The length of the CVs differed between 4–20 pages.

3.2.1. Expert participation by stakeholder group, gender, knowledge system

In total, 97 authors participated in this meeting, comprising of 13 Coordinating Lead Authors (including two Co-chairs with double roles) and 83 Lead Authors. They recruit mostly from scientific institutions and networks (70%), followed by representatives from ministries and administration (18%), non-governmental organisations (8%), and private business (4%). Gender balance was not achieved: the majority of authors are male (74%), only 25 authors are female (26%).

Furthermore, no holders of indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) are members of the expert group. However, there is a dedicated dialogue process, launched by the UNESCO-led IPBES task force on indigenous and local knowledge, to promote the integration of ILK into IPBES assessment processes. For the African Assessment, such a dialogue workshop, in which members of the expert group met ILK holders from different African regions and cultural backgrounds, was held in September 2015 in Paris. Its results have been circulated among the assessment authors, but it has not been decided yet how and where to integrate the collected ILK into the assessment report.

3.2.2. Expert participation by UN regions and african subregions

Authors of the African assessment come from three UN regions, of which the majority originates from Africa (82%, 79 experts), next to experts from the Western Europe and Others Group (WEOG, 17%, 17 experts) and one expert from the Asia-Pacific region ().

Table 2. Composition of the expert group by UN regions.

According to the scoping document for the IPBES Regional Assessment for Africa, the regional scope of the assessment covers five subregions: East Africa and adjacent islands, Southern Africa, Central Africa, North Africa, and West Africa. Numerically these regions are represented in the expert group as follows (in descending magnitude): Southern Africa, East Africa and adjacent islands, West Africa, North Africa and Central Africa (). While there is quite a balanced representation of countries by subregion for West, North and also East Africa (both in terms of number of different countries and the number of experts from these countries), particularly the participation of Central African states is biased: the only country out of nine that belong to the region which takes part in the assessment is Cameroon. Likewise, the Southern African region is quite dominated by a single country: South Africa.

Table 3. Countries and experts from the five African subregions as classified by the scoping document for the African Regional Assessment (IPBES/Citation3/Citation6/Add.Citation1 Citation2014); Countries marked in italic are IPBES member states.

3.2.3. Expert participation by disciplinary background and their assignment to chapters and author roles

We classified the authors into three categories: natural sciences, social sciences and the humanities, and interdisciplinary sciences (), based on the person’s primary disciplinary background, practical experience, main scientific subject and current position hold. As expected, natural sciences constitute the largest group of experts (71%), followed by interdisciplinary sciences (19%), and social sciences and the humanities (9%).

Table 4. Classification of the disciplinary backgrounds of the experts involved in the IPBES Regional Assessment for Africa (based on CVs as provided during the First Author Meeting held 2–6 August 2015, in Pretoria, South Africa) into the three fields of studies: natural sciences, social sciences and the humanities, and interdisciplinary sciences.

Next, we looked at the distribution of disciplines into the assessment’s six chapters and the author roles (Coordinating Lead Author or Lead Author) they had been assigned to (). The analysis shows that the author groups of four out of six chapters (1 – Setting the scene, 2 – Nature’s benefits, 3 – Status, trends, and future dynamics of biodiversity, and 6 – Options for governance) are constituted by all three science categories, however, still being dominated by natural scientists. Particular chapters 1 and 6 show a quite well mixed group of authors. Only two chapters are exclusively occupied by natural scientists, i.e. chapters 4 and 5 which address drivers of change (4) and interaction of the natural world and human society (5) – clearly two chapters that deserve integrated perspectives.

Table 5. Disciplinary backgrounds of the experts involved in the IPBES Regional Assessment for Africa (based on CVs as provided during the First Author Meeting held 2–6 August 2015, in Pretoria, South Africa), divided by the six chapters of the assessment report and author roles (Coordinating Lead Author or Lead Author).

3.2.4. Calling for replacement experts in 2016

During the development of the FOD of the assessment report a couple of authors withdrew from the process, so additional experts needed to be called for in 2016 to replace them (IPBES/Citation5/INF/Citation7 Citation2016). In total, 12 members of the initial expert group left, and seven new authors joined the team. Comparing the disciplinary backgrounds of the outgoing and incoming experts there has not been much change regarding the disciplinary balance within the group of authors – relatively given the overall ratio of the three different categories of disciplines:

Outgoing expertise: NAS (8): Water resources management (1), Microbiology (1), Agricultural sciences (2), Plant sciences (1), Botany (1), Ecology (2); SSH (3): Economics (1), Policy and law (1), Journalism (1); IS (1): Agricultural economics;

Incoming expertise: NAS (4): Biology (1), Ecology (1), Natural resources management (1), Animal rangeland and wildlife sciences (1); SSH (1): Economy (1), IS (2): Agricultural economics (1), Geographer (1),

3.3. Co-dissemination step

The production of the summary for policymakers (SPM) was started during the second author meeting held from 22–26 August 2016 in Bonn, Germany, and was continued during a writing workshop from 27 February to 3 March 2017 in Oslo, Norway. The document is currently under revision with the co-chairs and coordinating lead authors on basis of the comments received by governments. The final SPM will be presented at IPBES-6 in March 2018 in Medellin, Colombia, together the final draft of the assessment report (IPBES/Citation5/INF/Citation7 Citation2016).

4. Discussion: advancing co-creation in the IPBES regional assessment for Africa

4.1. Encourage nominations of scholars from the social sciences and the humanities

Biodiversity as boundary object requires integrated knowledge and understanding of the social-ecological system it is embedded in. This means having both the appropriate bodies of knowledges and a proper process of integration. If we look at the current composition of the African expert group, the conclusion reads quite straightforward: there is an overall lack of non-natural science perspectives and expertise – whereat we do not want to disregard the efforts the MEP has already put into at least fill the author roles with higher overall responsibilities, e.g. coordinating lead authors, with scholars from interdisciplinary and social sciences (see ). What needs to be understood here is, that the MEP of course can only select from the pool of experts that had been nominated – and if that pool is not matching the assessment’s expertise needs, the MEP has tied hands.

That is, if wishing to enhance and diversify the expert pool from which the MEP can select, it is indispensable to strengthen the outreach of the Platform and stir communication about IPBES in non-natural sciences networks and communities – networks which are mostly still off the IPBES radar – to make experts aware of their value to the Platform. It also means to approach related institutions and organisations, including governmental institutions, and to encourage them to nominate interested experts. Drawing from various discussions with IPBES authors there is further a great need to sharpen the issues and activities, as well as better estimate the financial and time resources IPBES authors are to expect. A large number of authors involved in different IPBES assessments have stated that it would have been easier to decide on the role and chapter to apply for – and to apply at all – if their descriptions would have been more concrete.Footnote11 (Of course, on the other hand, there is an advantage of leaving things rather open in the beginning of a process: one might have greater degrees of freedom to define ones duties and responsibilities within the expert team and the final issues to be covered.)

4.2. Specific roles for scholars from social sciences and the humanities within the african assessment

We tried to distil concrete entry points for experts in social sciences and the humanities (SSH) in the IPBES regional assessment for Africa, alongside the three steps of the co-creation concept as use before (). In general, there would be needed to accomplish the assessments itself, i.e. the co-production of the assessment report. Next to contributing to developing the narratives of particular chapter, such as chapter 2 on nature’s benefits to people or chapter 4 on direct and indirect drivers, SSH scholars could help to phrase a policy-relevant language and messages. Furthermore, they could help to facilitate the process itself bringing in their experiences and knowledge about such organisational and societal processes.

Table 6. Specific roles and tasks for scholars from social sciences and the humanities within the IPBES regional assessment for Africa, structured alongside the three steps of the co-creation concept.

4.3. Regional representation

Looking at the regional balance, the representation of the overall African region is quite good. However, when looking at the individual subregions numerous African countries need to catch up. This is not only relevant with regards to their (political) representation within the assessment process. It is much more important regarding their contributions: in terms of data, information, and knowledge, but also their world views, values and perspectives on biodiversity. IPBES needs to stimulate the engagement of currently underrepresented countries, for instance in the remaining author roles (contributing authors, expert reviewers) for which no formal nomination process is needed. The lower the fruits of participation hang, the likelier the engagement of missing countries, particularly with regard to lacking financial resources. Reviewing a document requires considerably low technical and financial inputs.

The reasons for the observed pattern are manifold of which financial constraints to take part in such an assessment is one of the challenge most reported by IPBES delegates and observers. Others are language barriers between anglophone, francophone, lusophone and hispanophone speaking African IPBES stakeholders, lack of (or lack of knowledge of) expertise within the country, weak political and institutional structures and commitment to delegate experts to IPBES processes.Footnote12 Identifying in which of these constraints IPBES could effectively and reasonably support is of high importance. For instance, the availability of IPBES documents languages other than English (only SPMs are translated into the six official UN languages), particularly French, Spanish, Portuguese and Russian.

5. Conclusions

To become relevant for different end users, but particularly for governments and other policy makers being the political key players in the science-policy interface, IPBES assessments need to reflect on the social-ecological systems biodiversity and ecosystem services are embedded in. To understand these systems it is indispensable to systematically integrate social sciences and the humanities in such assessment processes to allow for generating new knowledge in a collaborative and transdisciplinary co-production process – a lot better than is currently the case as shown here through the findings from our empirical analysis of the composition of the expert group undertaking the IPBES regional assessment for Africa.

In order to do so, IPBES needs to widen its outreach to networks of scholars from the social sciences and the humanities, those currently off-radar, and to inform them appropriately about the specific roles they could play within IPBES processes, particularly assessments. Such specific roles could encompass facilitating the understanding of the political aspects of assessments and identifying policy-relevant messages and helping to formulate them. But such roles could also address current knowledge gaps with regard to local and regional knowledge on how societies interact with nature, including indigenous peoples and local communities, their diverse conceptualisations of nature’s values, as well as underlying social drivers of change. In the case of the IPBES regional assessments for Africa, for example, such knowledge would be of great added value to chapter 2 (benefits of nature’s benefits to people) and chapter 4 (direct and indirect drivers), amongst others, to complement their currently natural-sciences focussed perspectives.

As a very good starting point to address these needs, IPBES, during its fourth plenary in February 2016, agreed on a new mechanism to fill expertise gaps in expert groupsFootnote13 and subsequently launched a call dedicated to scholars from the social sciences and the humanities to consider contributing to IPBES. However, if it still lacked clarity on the specific roles they could play within e.g. IPBES assessments. Future such calls should address this. Specific networking support could be channelled through existing and emerging initiatives aiming at supporting IPBES in reaching out to stakeholders and potential experts, such as the European biodiversity platforms which have been active in matter of IPBES on both the national and the pan-European level for several yearsFootnote14 and the IPBES Engagement Network,Footnote15 amongst many others.

Furthermore, the process of co-dissemination (besides the preparation of the Summary for Policymakers) is still to be defined: an exciting laboratory to explore new participatory approaches with the relevant mix of experts from all fields as well as end users to distil useful knowledge from assessment reports.

In conclusion, the paper calls for strengthening the practice of transdisciplinary and transdisciplinary integration in IPBES assessments, as well as equal representation in terms of regional expertise and gender, by carefully composing its expert groups, particularly with regards to existing knowledge gaps and complementary perspectives on social-ecological systems.

ORCID

Katja Heubach http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4298-7750

Notes

1 The IPBES Regional Assessment for Africa is one of 12 assessments IPBES is to undertake during the phase of its first work programme 2014 to 2018, and among the four regional assessments (for Asia-Pacific, Africa, Americas, and Europa/Central Asia) of the Platform.

2 The report of the final of three multi-stakeholder meetings preparing the establishment of IPBES.

3 As stated in the “Busan Outcome”, the report of the 3rd multi-stakeholder meeting on IPBES, Busan, 2010; UNEP/IPBES/Citation3/INF/Citation1/Add.Citation1 Citation2010.

4 Future Earth was launched in 2015, being the follow-up to recent programmes addressing global environmental change, such as DIVERSITAS or the International Human Dimensions Programme (IHDP).

5 We would like to emphasize that we are not looking at the quality of the process in terms of quality standards in transdisciplinary process. One major reason for this is that currently only few of such quality standards exist and the results of the current debate around this subject remain to be seen. The other reason is that the process is still in its drafting stage and therefore such evaluation seems far too early.

6 IPBES defines to categories of stakeholder: “contributors (scientists, knowledge holders, practitioners and others) and end-users (policymakers and others).” (IPBES/Citation3/Citation18 Citation2015, p. 114, para 8)

7 Subsidiary body in charge of administrative issues

8 With the exception of so-called fast-track assessments which would not need a detailed scoping as the availability of data and knowledge on the selected topic is considerable comprehensive and accessible to allow for a “fast” synthesis. In this contribution we only look at the standard process for assessments under IPBES.

9 For Africa, Asia-Pacific, the Americas, and Europe/Central-Asia

10 This data is derived from an analysis of the constitution of the list of participants of the scoping workshop for the regional assessments as provided by IPBES on its website: http://www.ipbes.net/work-programme/regional-and-subregional-assessments.

11 Personal communication and findings from several IPBES-related workshops conducted by the Network-Forum for Biodiversity Research Germany – NeFo http://www.biodiversity.de/de

12 Information obtained from frequent discussions with African colleagues and others engaged in IPBES, during IPBES plenaries and related workshops and meetings.

13 IPBES/4/15, Annex

References

- Bergmann, M., T. Jahn, T. Knobloch, W. Krohn, C. Pohl, and E. Schramm. 2012. Methods for Transdisciplinary Research. A Primer for Practice. Frankfurt, Germany: Campus Verlag.

- Briggs, S. V., and A. T. Knight. 2011. “Science-Policy Interface: Scientific Input Limited.” Science 333: 696–697. doi: 10.1126/science.333.6043.696-b

- Heink, U., E. Marquard, K. Heubach, K. Jax, C. Kugel, N. Neßhöver, R. K. Neumann, et al. 2014. “Conceptualizing Credibility, Relevance and Legitimacy for Evaluating the Effectiveness of Science.” Policy Interfaces: Challenges and Opportunities Science and Public Policy (2015)42 (5): 676–689.

- IPBES/2/17. 2014. Report of the Second Session of the Plenary of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

- IPBES/3/18. 2015. Report of the Plenary of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services on the Work of its Third Session.

- IPBES/3/6/Add.1. 2014. Report on the Regional Scoping Process for a Set of Regional and Subregional Assessments (Deliverable 2 (b)) Draft Generic Scoping Report for the Regional and Subregional Assessments of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.

- IPBES/4/INF/10. 2015. Progress Report on the Implementation of the Regional and Subregional Assessments on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (Deliverable 2 (b)).

- IPBES/4/INF/9. 2016. Guide on the Production and Integration of Assessments From and Across All Scales (Deliverable 2 (a)).

- IPBES/5/INF/7. 2016. Progress Report on the Implementation of the Regional and Subregional Assessments on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (Deliverable 2 (b)).

- Jahn, Th., M. Bergmann, and F. Keil. 2012. “Transdisciplinarity: Between Mainstreaming and Marginalization.” Ecological Economics 79: 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.04.017

- Koetz, T., K. N. Farrell, and P. Bridgewater. 2012. “Building Better Science-Policy Interfaces for International Environmental Governance: Assessing Potential Within the Intergovernmental Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.” International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 12: 1–21. doi: 10.1007/s10784-011-9152-z

- Lang, D., A. Wiek, M. Bergmann, M. Stauffacher, P. Martens, P. Moll, M. Swilling, and C. J. Thomas. 2012. “Transdisciplinary Research in Sustainability Science: Practice, Principles, and Challenges.” Sustainability Science 7 ( Supplement 1): 25–43. doi: 10.1007/s11625-011-0149-x

- Mauser, W., G. Klepper, M. Rice, B. Schmalzbauer, H. Hackmann, R. Leemans, and H. Moore. 2013. “Transdisciplinary Global Change Research: the co-Creation of Knowledge for Sustainability.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 5 (3–4): 420–431. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2013.07.001

- Montana, J., and M. Borie. 2015. “IPBES and Biodiversity Expertise: Regional, Gender and Disciplinary Balance in the Composition of the Interim and 2015 Multidisciplinary Expert Panel.” Conservation Letters 9: 138–142. doi:10.1111/conl.12192.

- Perrings, C., A. Duraiappah, A. Larigauderie, and H. Mooney. 2011. “The Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services Science-Policy Interface.” Science 331: 1139–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.1202400

- Reid, W. V., C. Bréchignac, and Y. T. Lee. 2009. “Earth System Research Priorities.” Science 325 (5938): 245. doi:10.1126/science.1178591.

- Spierenburg, M. 2012. “Getting the Message Across.” Biodiverisity Science and Policy Interfaces – A Review, GAIA 21: 125–134.

- Tress, G., B. Tress, and G. Fry. 2005. “Clarifying Integrative Research Concepts in Landscape Ecology.” Landscape Ecology 20 (4): 479–493. doi: 10.1007/s10980-004-3290-4

- UNEP/IPBES/3/INF/1/Add.1. 2010. Analysis of the Assessment Landscape for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services.