Abstract

The article discusses mechanisms and policy that stimulate regional economic restructuring. Economic restructuring is conceptualised through the notion of path development. The article distinguishes four types of path development: the extension and upgrading of existing regional industries are two types, diversification of existing industries and the creation of new industry paths are the two others and more substantial path developments. A main idea in the article is that new path development requires industry actors who initiate new firms or innovation activities in existing firms, i.e. firm level agency, but that restructuring also requires action by actors operating in the regional support system, i.e. system level agency. System level agency, understood as actions or intervention to transform regional innovation systems to better support economic restructuring, is particularly important for the two most ‘radical’ types of restructuring, i.e. path diversification and creation, and in regions with thin and specialised knowledge and industrial structure.

1. Introduction

Industry and society face significant challenges from globalisation, technological development, environmental regulations and so on that demand relevant answers. Existing firms and industries face restructuring challenges, and new industries who can address pressing challenges are required. Industrial restructuring through innovation activity occurs to a large extent as regional (sub-national) processes (Martin Citation2010). This implies that knowledge about regional economic restructuring and how this can be stimulated though regional adapted policy is important.

The academic and policy literature maintains that the promotion of existing economic strongholds and specialisations does no longer suffice as the key policy strategy to ensure the long-term competitiveness of nations and regions (Asheim, Boschma, and Cooke Citation2011; European Commission Citation2012; Foray Citation2015). New policy concepts such as smart specialisation highlight the need to develop innovation strategies that foster economic structural change, i.e. policies that support restructuring through diversifying into new but related economic fields or creating entirely new sectors (e.g. Boschma Citation2014; Foray Citation2015). This new strategic orientation for (regional) innovation policies has been informed by evolutionary economic geography (EEG) and related disciplines. These have offered new insights into how regional economies transform over time and how new growth paths come into being (Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Neffke, Henning, and Boschma Citation2011; Simmie Citation2012).

The EEG approach mainly regards regional economic restructuring as a firm-led process of regional branching in which technological, related knowledge is combined in novel ways, resulting in the emergence of new industries related to the existing industrial structure (Boschma and Frenken Citation2011). This means that restructuring of economic activity typically results from changes in existing industries and economic activities, i.e. upgrading and diversification of economic activity, but also that creation of new industry activity is an important enabler for restructuring. The article studies different forms of regional restructuring, which we define as substantial changes in existing industries in a region (for example the introduction of more automated production processes) and the development of new industries for a region. Thus, the aim of the article is to examine the importance and role of different types of agency (firm level and system level agency) in different forms of regional economic restructuring. The conceptual discussion aims to combine approaches on regional restructuring, agency and regional innovation systems to broaden our understanding of how and to what extent different types of restructuring develop in different types of regions. Based on the conceptual framework we also discuss what can be relevant policy for enabling different types of restructuring.

The next sections of the article develop a conceptual framework that postulates how different types of regional economic restructuring, in the meaning of different path developments, can emerge through the combined effect of firm level and system level agency. The conceptual framework is illustrated with four example cases from Norway, each portraying a specific industrial path. The cases form the basis for discussions of relevant policies to stimulate different types of regional industrial restructuring.

2. Regional industrial path development

The article considers regional industrial restructuring through the lenses of path dependence theory (Boschma and Frenken Citation2006; Martin and Sunley Citation2006). This approach maintains that ‘history matters’, current industrial activity in a region, represented by the industrial structure, dominant technology solutions, skill bases etc. is largely influenced by the region’s former industrial development. Former development paths are thus reflected in, amongst others, current education and study programmes, in workers’ skill, and in informal institutions in the meaning of ‘taken-for granted’, culturally embedded understandings.

The literature offers various fine-grained typologies to distinguish between and categorise different types of industrial path development (Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Tödtling and Trippl Citation2013; Isaksen Citation2015; Grillitsch, Asheim, and Trippl Citation2017). We find it, however, too complex to work with many detailed regional industrial paths when the aim is to construct a conceptual framework that analyses how restructuring is influenced by various types of agency and how this is linked to different regions. We therefore chose to apply a distinction between four different regional industrial paths; extension, upgrading, diversification and creation (Neffke, Henning, and Boschma Citation2011; Grillitsch, Asheim, and Trippl Citation2017). Together, these constitute a continuum from continuation (path extension) through to change and novelty (path creation) in the industrial development in a region. Taken together, these four paths inform about the complex processes of regional economic restructuring.

Regional industrial path extension consists of ‘incremental product and process innovations in existing industry and along prevailing technological paths’ (Isaksen Citation2015, 587). This will most often lead to consolidation of prevailing industrial activities, although stepwise innovations over time will lead to changes in existing industries (for example by employing new technologies). Thus, this process represents a low degree of change.

Path upgrading consists of ‘major intra-path changes, that is, changes of an existing regional industrial path into a new direction’ (Grillitsch, Asheim, and Trippl Citation2017, 15). Upgrading takes place through the inclusion of new technologies or major organisational changes, development of more advanced functions or more specialised skills, and development of niches in mature industries (op. cit.).

Path extension and upgrading can slowly change the firm structure and move the regional industry into new directions when both existing and new firms employ more advanced techniques, introduce different variants of products and services, organise differently, and so on (Martin Citation2014). Such changes, however, first of all strengthen the competitiveness of existing regional industries through continuous improvements and more efficient processes rather than the development of new industries. Path extension and upgrading take place continually as part of firms’ efforts to maintain their competitiveness. They result in the strengthening of some regional industries often at the expense of others (due to limited regional resources).

Path extension and upgrading characterise the bulk of regional economic activities. At the same time though, new activities and industries can simultaneously emerge in a regional economy. Such activities ‘emerge from and develop alongside, and perhaps eventually replace, existing activities’ (Martin Citation2014, 622).

New industries can emerge through regional industrial path diversification and creation. Diversification results from capabilities in existing regional firms and industries. New paths emerge when existing regional competence is combined with (local or external) related or unrelated knowledge. This combination results in new competence and innovations exploited by existing firms when they move into new markets or by new firms established in the region.

Path creation is a more comprehensive way of restructuring, and represents a substantial degree of novelty for a regional economy. Path creation comes about when firms and industries are transplanted into a new region, or through the commercialisation of knowledge and competence already developed and existing in the region (Tödtling and Trippl Citation2013). Even though path creation applies to brand new industries for a region, emergence of a new industry is often based on the existence of relevant assets, resources or competencies already present in the region. Examples include an excellent scientific base or the availability of a highly skilled labour force (Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Isaksen Citation2016). External investments, for example by multinational companies, are typically targeted towards regions where some existing, relevant knowledge and skills exist. This means that path creation covers formation of an industry that is new to a region, but this industry does not need to be new from a global perspective.

Path diversification and creation appear through the emergence of new industries in a region. The development of ‘full-grown’ industries may take long time since these, as we will see, must be included in value chains and institutional frameworks, i.e. consists of more than the establishments of some new firms (or substantial change in existing ones). The time taken will vary with a number of issues related to the industry in question and the existing regional innovation system (see below).

3. Firm and system level agency

The path development approach provides a nuanced picture of processes influencing regional restructuring. The approach focuses on ‘major’ mechanisms such as knowledge creation and combination. However, this approach has until recently said little about ‘agency, that is about how economic and other actors create, recreate, and alter paths’ (Martin Citation2014, 619; italics in original quotation). This article aims to bring agency stronger into the path development approach to achieve more insight in how regional economic restructuring may take place. Agency is defined as an ‘action or intervention by an actor to produce a particular effect’ (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998; Sotarauta and Suvinen Citation2018). This is furthermore linked to discussions on the role of agency in regional economic change, where for instance the recent contribution of Boschma et al. (Citation2017) discusses the importance of approaches sensitive towards both the firm and the system level. Similarly, the approach of ‘entrepreneurial ecosystems’ (Stam Citation2015; Spigel Citation2017) has moved focus from the firm-level as drivers of entrepreneurship to also include discussions of contextual factors underpinning entrepreneurship activity. This field of research shares similarities with the regional innovation system literature in that it relates a major part of firms’ competitiveness to resources found within the regional environment, rather than residing within the single firm or the individual entrepreneur (Isaksen and Jakobsen Citation2017). Based on this, it can be argued that regional economic restructuring results from combinations of firm level and system level agency, and combinations of the two approaches has been called for (Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero Citation2017; Njøs and Fosse Citation2018).

However, for analytical purposes, we discuss the two types of agency separately. Firm agency or organisational agency considers how actors start new innovative firms or organisations, or initiate new activities in existing firms or organisations with the potential to create new growth paths. A much-cited study on the role of agency for restructuring and the creation of new industrial paths is Garud and Karnoe’s (Citation2003) study of the development of the wind turbine industry in Denmark and the US. They focus on distributed agency and embedded involvement as key concepts. Distributed agency points towards how successful introduction of a new technology and the development of a new industrial path does not only rely on the inventor or the first mover that introduces the technology in the market, but also on those who develop complementary assets, rivalling technology developers, customers, policy actors and so on. In the development of a new technology, multiple actors with different levels of involvement participate, meaning that agency is distributed across actors.

A similar argument is found in transition studies which argue that the creation of new industrial paths presupposes efforts from multiple actors (Geels and Schot Citation2007; Boschma et al. Citation2017). This includes not only those developing new ideas and products, but also other industry actors (suppliers, collaborators, competitors etc.), policy actors, research milieus, potential customers etc. (Simmie Citation2012). A core in transition studies is analyses of how the mindful deviation of entrepreneurs can promote systemic changes through co-evolutionary and multi-level processes. It is argued that entrepreneurs are influenced by their surrounding environment, while at the same time they intentionally try to deviate from established routines and practices and create new market possibilities.

Embedded involvement is associated with the learning and knowledge accumulation processes in the development of an emerging industrial path. Firms and other actors are embedded in these processes through their involvement, and the knowledge that they collectively develop becomes a platform for future action. Garud and Karnoe (Citation2003) distinguish two different models for the development of new industrial paths. The first model is bricolage, which is a stepwise and bottom-up process in which a new technology is constantly improved through incremental innovations. The process is driven by distributed agency, embedded involvement and local knowledge, and implies a gradual transformation of a new technology towards an industrial path. The alternative model is a breakthrough strategy, where key actors are pushing for fundamental changes which can lead to a lack of collective learning and embedded involvement. The authors found that the success of the wind turbine industry in Denmark could be explained by their bricolage strategy, while the breakthrough approach of the turbine industry in the US was far less successful due to the fact that pursuing a breakthrough in this case reduced the micro-learning processes that are fundamental for the co-creation of new technology paths.

The importance of distributed agency points to the second type of agency, system level agency. We link system level agency to the regional innovation system approach. A regional innovation system (RIS) includes regionally located industries that are embedded in a regional knowledge infrastructure and institutional framework (Asheim and Isaksen Citation2002). The RIS includes long-term knowledge links between regional actors. System level agency is based on actions or interventions able to transform regional innovation systems to better support growing industries and economic restructuring. We focus in particular on changes by the actors that constitute RISs (firms, knowledge and support organisations) and in the links between the actors.

Similar arguments are put forward by Musiolik, Markard, and Hekkert (Citation2012) who regard system building as an important activity in the development of technological innovation systems so that these support emerging business fields. ‘System building is the deliberate creation and modification of broader institutional and organisational structures (…) carried out by innovating actors’ (op. cit.: 1035). System building is regarded as a collective approach by set of actors who joins forces in networks. A key to system changes is the interplay and deployment of resources at the organisational, network and system level.

The defining characteristic of system level agency is that actors exert influences outside their institutional or organisational border. It can be defined as ‘the leadership of interdependent actors and institutions that are operationally autonomous and not necessarily connected in a formal system of steering and authority’ (Normann et al. Citation2017, 275). An example of system agency that transcends institutional spheres is a regional cluster manager and a dean that aligns industry strategy with regional university strategy, for example in developing a joint educational programme or a user oriented research centre (Normann, Vasström, and Johnsen Citation2016). Another example is agency in the public support system that develops and implements new policy measures to which actors and institutions can respond and adapt.

When discussing regional industry restructuring and industry formation, it is relevant to analyse how regional innovation systems contribute to such changes. From a RIS perspective, system level agency is action or intervention to change the functioning of the regional support structure for innovation. These changes can in principle be of three types (Miörner and Trippl Citation2017). First, within the RIS, new institutions, organisations and policy instruments can be created and added to the existing structure (layering). Second, existing institutions, organisations and policy instruments can be adapted to for example better fit emerging industrial paths (adaptation), and third, existing institutions, organisations and policy instruments can be used in new ways (novel application).

Various conceptualisations of what we denote as system level agency have emerged in the regional development literature as attempts to combine insights from evolutionary economic geography (Boschma et al. Citation2017) with institutional theories (Sotarauta, Horlings, and Liddle Citation2012; Normann Citation2013; Beer Citation2014). In this setting we can identify system level agency as carried out by skilled social actors with highly developed cognitive capacity for ‘reading’ people and environments, framing lines of action, and mobilising people in the service of broader conceptions of the world and themselves to fashion shared worlds and identities (Jasper Citation2004).

We see both types of agency as necessary for new path development. summarises the role of firm level and system level agency in the four types of regional path development. There is no clear-cut boundary between the four industrial paths and, thus, it is also difficult to distinguish the role of firm level agency as well as system level agency between the paths. However, the table brings out some key points in how the two types of agency contribute to industrial path development, but it should be noted that combinations of the two is a precondition for all types of new path development (Zukauskaite, Trippl, and Plechero Citation2017). Necessarily, the dynamics underpinning the interplays between firm and system agency is largely an issue of contextual specificities (i.e. regions), something that is returned to in Section 5.2.

Table 1. The role of firm level and system level agency in different types of path development.

4. Regional innovation system as stimulating and hampering new path development

System level agency is deemed as necessary as regional innovation systems often support (incremental) innovation processes and the competitiveness of existing regional industries, i.e. path extension and to some degree path upgrading. If changes in RISs are not introduced, a lock-in situation can occur, which stems from close and stable linkages between regional firms and between the politico-administrative system and regional industry (Grabher Citation1993). This points to a paradoxical situation. On the one hand, restructuring requires changes in the support system, i.e. the knowledge and institutional infrastructure. However, on the other hand and given that RISs are characterised by a certain degree of stability and continuation (Jakobsen et al. Citation2012; Njøs and Jakobsen Citation2018), the existing support system may not be tuned towards supporting emerging industries that challenge existing regional practices. This means that stable RISs can be ‘prone to lock-in and path dependency [as they are] largely geared to generate incremental innovations and gradual change’ (Boschma et al. Citation2017, 36), and well-functioning RISs often do not support development of new growth paths (Weber and Truffer Citation2017).

In other words, regional innovation systems can both support and hamper regional economic restructuring. This is further illustrated by discussions of the innovation system failure approach. Four distinct types of innovation system failures are identified by Klein Woolthuis, Lankhuizen, and Gilsing (Citation2005). The first is capability failures. This involves that RIS actors such as firms and knowledge and support organisations lack appropriate competence. Second, coordination failures include on the one hand too much information and knowledge exchange between a stable set of actors, and on the other hand lack of interactions and knowledge exchange between actors in the RIS. Third, institutional failures occur when formal institutions (laws, regulations etc.) and informal institutions (norms and implicit ‘rules of the game’) hinder innovation. Last, infrastructural failures include, in particular, poor or lacking knowledge infrastructure and high-quality ICT infrastructure.

These system failures hinder RISs to efficiently support innovation activity in existing regional industry. Through correcting system failures, improved conditions for existing industries (for which it is possible to identify and rectify weaknesses in the RIS) can be introduced. Moreover, ‘the rather static concept of system failures’ (Weber and Truffer Citation2017, 113) should be expanded to also include transformation failures understood as the failures of RISs to support the emergence of new industrial growth paths, i.e. path diversification and creation. Grillitsch and Trippl (Citation2016) distinguish two regional innovation system barriers; those that hamper the breaking with existing paths and barriers for growing new paths. ‘Structural change results from a combination of breaking with existing structures (…) and growing new development paths’ (Grillitsch and Trippl Citation2016, 7). Barriers to break with existing regional industrial paths are strong capabilities of RIS actors in existing industries, strong connectedness and interdependencies between actors in the old path, and institutions that are customised to supporting the old path. The opposite innovation system barriers hamper the development of new regional industrial paths, i.e. weak capabilities in emerging paths, weak connectedness between actors with relevant knowledge for the new paths, and weak institutional alignments for new paths (Grillitsch and Trippl Citation2016).

Following this line of thought, transformation failures in the form of barriers to the growing of new regional industrial paths can be seen as specific characteristics of the above mentioned four failures. These includes that a) RIS actors are lacking knowledge and competence of new technology, business models etc. that can form the basis for emergent industries, b) networks between RIS actors are too close to acquire new, relevant knowledge for new sectors, or networks relevant for new growth paths are non-existent or weak, c) regulations and informal ‘rules of the game’ are not adapted to new ways of doing things, and d) knowledge and physical infrastructures that fit the requirements of emerging industries are not developed or supported.

Consequently, we argue that new growth paths require both firm level agency and adaptation or transformation of regional innovation systems by system level agency. We link this argument to evolutionary reasoning. Evolutionary theory holds that different levels, such as the firm and the system level, may be characterised by divergent rationales and logics, and, not least, different development trajectories (Martin and Sunley Citation2006; Bergek et al. Citation2008). Different paths can compete within the same setting (Onufrey and Bergek Citation2015) (e.g. a region), echoing arguments from the literature on transition studies, and especially the sub-field of Technological Innovation Systems (TIS) (Carlson and Stankiewicz Citation1991). This literature has mainly been concerned with the ‘functionality’ of innovation systems (Hekkert et al. Citation2007; Bergek et al. Citation2008), where understandings of linkages between the levels are of particular importance. Similar discussions have also surfaced in the literature of Evolutionary Economic Geography, where the role of different forms of agency has become an important topic when discussing regional economic restructuring (Simmie Citation2012; Dawley et al. Citation2015; Boschma et al. Citation2017). The point here is that these discussions call for ‘moving beyond’ static approaches, and instead open up for approaching intersections between (regional) actors (firm-level agency) and the regional innovation systems (system-level agency).

5. The geographical specificities of agency and its role in different path developments

Hence, we argue that different geographical contexts are characterised by differentiated interplays between firm level and system level agency. However, from a theoretical point of view it can be argued that the four different path developments are characterised by different ‘mixes’ between the two types of agency. As the degree of change increases, that is, as one moves on the continuum from path extension through to path creation, the importance of firm level actors that breaks with traditional ways of doing things or come up with brand new ideas increases in importance. The need for further development and adaption of the regional innovation system also increases, and, thus, the importance of system level agency increases accordingly. Similarly, while agency for path extension can be of the reactive type, path creation requires more proactive agency. It should also be noted that paths evolve over time and that the two types of agency play different roles in different phases of evolution, for instance implying that policy should be adapted to such developments (Njøs and Jakobsen, Citation2018).

5.1. Two ‘roads’ to new path development

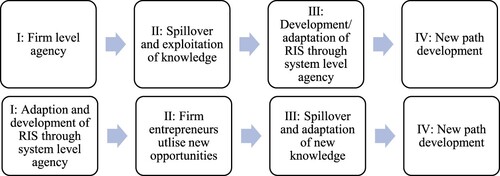

To further discuss the role of the two types of agency, two different, simple ‘roads’ to regional restructuring are outlined in . These can be combined in different ways as discussed below. They are nevertheless presented here as two separate processes for analytical purpose. The first approach, the firm-oriented road, starts when firm level actors come up with new ideas, inventions or innovations that have some potentials to upgrade existing or create new regional industrial paths. For a new path to appear the innovation developed by the forerunners have to be employed and possibly adapted by several other firm actors so that a critical mass of firms or organisations using a new technology, producing a new product or service, and so on, emerges (Foray Citation2015). Diffusion and further development of new knowledge and innovations is the first precondition for new path development in this approach. The next precondition is that the regional innovation system develops to fit better a new or altered regional path. This means that box III in the firm oriented road is linked to box I in the second road. In this case, firm level agency ‘push’ forward changes in the regional innovation system. The first initiatives are taken by firm actors, but in line with our conceptualisation of path development, system actors must contribute by developing and changing the RIS to better support the new initiatives.

The other route, the RIS-oriented road, to new path development starts when system level actors develop and adapt regional innovation systems to better fit the need of potential new industries, technologies, business models and so on. Examples of system level agency are the introduction of organisations facilitating the commercialisation of research ideas, support for technology development in cooperation between firms, research institutes or technology centres, or by regulations to protect firms in new market niches. The idea is then that firm level actors in new and existing firms utilise new possibilities, that lead to the fact that more firms and organisations use new knowledge and skill, and a new regional path can emerge.

5.2. The role of different types of RIS

We have argued that restructuring, understood through four conceptual path developments, is characterised by interplays between firm level and system level agency, as illustrated in the two ‘roads’ in . We will further argue that the importance of firm level versus system level agency depends on the type of regions in question, for example if new paths emerge in metropolitan or peripheral regions (Isaksen et al. Citation2018).

We characterise regions by use of the regional innovation system approach. Different types of RISs have different potentials to supporting innovation and new path development. We follow the typology in Isaksen and Trippl (Citation2016) by distinguishing three types of RISs that are supposed to have different potentials for interactive learning, innovation and new path development. RISs are separated based on the number and variety of RIS actors, i.e. firms, industries and knowledge and support organisations present in a region.

The three different types of RISs include organisationally thick and diversified RISs, organisationally thick and specialised RISs, and organisationally thin RISs (op. cit.). Organisationally thick and diversified RISs have a relatively large number of different firms, a heterogeneous industrial structure and a number of knowledge and supporting organisations that facilitate innovation in different economic and technological fields. This type of RIS is most often found in large core regions like metropolitan areas.

Organisationally thick and specialised RISs host strong clusters in one or a few industries only, and knowledge and support organisations are mostly adapted to regions’ narrow industrial base. These RISs are typical for old industrial areas. Compared to the first type, thick and specialised RISs are supposed to have poorer conditions for radical innovations, path diversification and creation, while more possibilities for lock-in of existing industrial strongholds (Grabher Citation1993).

Organisationally thin RISs have few knowledge and support organisations and none or weakly developed clusters. Such characteristics are often found in peripheral regions. These offers little potential for new path development based on local skills and resources. Thus, actors with external knowledge links or in-migrants are assumed to be important in innovation and new path development processes in this RIS-type.

theorises (based on Isaksen et al. Citation2018) about the importance of firm level and system level agency in each of the three types of RISs, and about possible industrial paths in each type. Empirical studies point to the fact that thick and diversified RISs demonstrate considerable economic dynamism and radical innovation activity compared to the two other regional types (Feldman and Audretsch Citation1999; Duranton and Puga Citation2002). Based on this, we expect firm level actors to initiate much innovation activity in new and existing firms and organisations in thick and diversified RISs. The firm level actors in this RIS-type also have the possibilities to make use of the large and diversified knowledge infrastructure in thick and diversified RIS. A fragmented and complex system may, however, hamper knowledge flow and innovation activity in these RISs (Tödtling and Trippl Citation2005). The strengthening of knowledge links between industry and academia may therefore be particularly relevant in thick and diversified RIS, which also is a task for system level actors.

Table 2. Type of agency and new path development that characterise different types of regional innovation systems.

Regions with thin RIS have far less dynamic industry (Petrov Citation2011). Generally speaking, these regions can to a lesser extent than thick and diversified regions rely on firm level actors to create new innovations that can lead to new paths development. We therefore expect system level agency that include system building (Musiolik, Markard, and Hekkert (Citation2012), to be relatively more important in thin RISs compared to the thick and diversified ones.

This applies also in thick and specialised RISs which have industry that in general is attuned to incremental innovations. By definition, thick and specialised RISs have knowledge and support organisations within a narrow area of knowledge, which also provides a need for system level agency.

Based on the above arguments, the three types of regional innovation systems are expected to be able to support different types of new path development. Path extension and upgrading are key to industrial development in all types of RISs. Besides that, path creation and diversification are first of all possible in thick and diversified RISs due to their industrial dynamics, varied industrial structure and heterogenous knowledge infrastructure The characteristics of the two other RIS-types make it more demanding to support path creation and diversification. Thus, we argue that thin and thick and specialised RISs first of all are able to strengthen path extension and upgrading (Isaksen and Trippl Citation2016). In addition, we anticipate that the thick and specialised RIS to some extent can support path diversification.

6. Empirical illustrations

In order to illustrate and further clarify our conceptual discussion, four concrete examples from Norway are employed, one for each of the four industrial paths. The role of firm level and system level agency is portrayed in each case. The cases also lie behind the discussion of policy lessons for regional restructuring in section 7.

Path extension is exemplified by the process industry in the Agder region in Norway, which resembles a thick and specialised RIS. The about ten main firms in the process industry in Agder are part of multinational companies (MNCs). The firms have developed increasing collaboration the last decade through a cluster project. The collaboration has focused on the development of competence and tools for resource and energy efficient, more sustainable, production. The process innovations provided for path extension in this case.

The cluster project and the collaboration were initiated by CEOs in the major process industry firms in Agder (Landmark, Rodvelt, and Torjesen Citation2015). The firms are not competitors, but experienced similar challenges in maintaining and increasing global competitiveness and to uphold their position within the MNCs. The CEOs quickly identified a vision for the cluster, framing their aim as a goal of becoming a world-leading knowledge hub within sustainable process industry by 2020. The development resembles the firm oriented road in , with initiatives by firm actors followed by system level agency The systemic changes have mainly included increased collaboration and joint projects among cluster firms and with external actors, in particular with regionally located research institutes and the University of Agder. Of key importance is also a number of projects for joint knowledge sharing and joint research and innovation run by the cluster organisation.

The aquaculture industry in the county of Hordaland on the west coast of Norway, with a relatively thick and diversified RIS, exemplifies path upgrading. There is widespread concern in the aquaculture industry about negative environmental effects caused by the open net-pen technology of Norwegian fish farming, such as ocean floor waste, spread of diseases, escape of fish and sea lice. This has created a call for new technological solutions, materialised in a policy-induced greening programme that began in 2014 and ‘development licences’ launched in 2015. It also means that system level agency is a more important triggering factor than in the previous case (Fløysand and Jakobsen Citation2016).

The introduction of ‘green licences’ and ‘development licenses’ marked a shift towards a more explicit green policy attitude by the Norwegian government. The announced licences were met with great interest. About 350 organisations applied for the 45 new green licences, which illustrates a willingness from firm level actors to invest capital into sustainable fish farming. Three new technology systems are presently being developed and introduced to the aquaculture industry which all represent radical technical innovations. The ongoing development of new technological solutions within fish farming represents an upgrading of this industry path, and illustrates that system level agency at the national level and firm level agency work in tandem in the process of developing a more sustainable industry.

The subsea industry in the Bergen region (with a thick and diversified RIS) in western Norway is specialised in maintenance, operation and adaptation of subsea equipment for the oil and gas industry. However, recent developments in the industry illustrates path diversification. The downturn in the oil and gas market from 2014 resulted in a need for restructuring among many actors in the subsea industry. As the Bergen region is characterised by a varied industry structure with related, ocean-based industries (e.g. shipping, fish farming and renewable energy), this has, together with targeted efforts by firms and system actors, stimulated ongoing restructuring activities in the form of path diversification.

For instance, the cluster organisation GCE (Global Centre of Expertise) Subsea has been an important enabler towards path diversification. Initially, GCE Subsea focused on the petroleum market and petroleum industry only. However, since the drop in oil prices in 2014, proactive efforts have been taken towards strategic reorientation of the cluster initiative and linked activities. Hence, the subsea industry in the Bergen region has evolved from focusing on the oil and gas market to instead encouraging development of subsea competence and knowledge that is applicable also within other markets and industries, where it currently appears that fish farming (which is also strong in the Bergen region) is the most attractive one. In addition to this, other system actors (e.g. industry facilitators, policy makers and others) are also consciously working towards stimulation of cross-over activities between regional industries. This case also illustrates the importance of system and firm actors that move in the same direction.

The industry that develops cancer medicine and treatment in Oslo exemplifies path creation. Important for path creation is about 15 entrepreneurial, and mostly small pharmaceutical, firms that have been established the last two decades (Isaksen Citation2016). These are most often spin-offs or start-up companies with Norwegian entrepreneurs and venture capital. The entrepreneurs’ core competence originates in particular from research carried out at the large, specialised cancer treatment hospital in Oslo, Radiumhospitalet. The large company Hydro also acted as an important firm level agent for some years through a pharmacy department that cooperated with the research milieu in Oslo. Hydro contributed with industry experience about e.g. start-ups and business planning to complement researchers’ scientific knowledge.

The system level agency of particular importance for the growth of the cancer medicine industry in Oslo includes two regulatory changes in Norway in 2003, in addition to the work by the cluster organisation Oslo Cancer Cluster. The regulatory changes are coupled. A new law on employee invention meant that employers could claim the right to inventions made by workers transferred to them, while the University and University College Law of 2003 included a duty for these organisations to provide for the application of research results in industry. These regulations led to the build-up of stronger commercialisation units, such as seed and venture capital funds, in Oslo. In addition, the Oslo Cancer Cluster has initiated increased collaboration among regional actors and beyond. This is a case where firm actors are key but where these actors’ potential for creating a new path was triggered by specific firm level agency.

7. Policy reflections

The four cases illustrate the role of firm level and system level agency for different types of regional industrial path development. We use the cases in a discussion of policy that may support each of the industrial paths, and we also point to possible, more general policy lessons ().

Table 3. Illustrative policy lessons from four example cases.

The example from the joint effort among traditional process industry firms in the Agder region to increase competitiveness and become a world-leading knowledge hub within sustainable process industry points to the fact that traditional cluster and RIS policy is relevant for path extension. Such policy should also open up for creating and acquiring relevant knowledge from regional actors beyond the firm cluster (such as building local knowledge in higher education institutions and R&D-institutes) and from outside the region (Njøs and Jakobsen Citation2016). Our example of path upgrading is quite specific as it includes the aquaculture industry on parts of the west coast of Norway. Path upgrading involves in this case to developing a more sustainable industry, which is stimulated by a combination of regulations, where new concessions are given to firms that develop new ‘green technology’, and commercial actors willing to invest in new, costly technology solutions. The case demonstrates the importance of system level agency in the form of government regulations and support measures to upgrade a successful path in which significant investments in new technology and competence are required by firms.

Path diversification can be supported by system level agency that contributes to linking firm level actors. That is the case in our example from the subsea oil and gas industry in the Bergen region. Several cluster organisations in this area are working to connect their members and to investigate how existing competencies can be used across clusters, technologies and market areas, such as to use skills from the subsea industry in fish farming.

Path creation may require long-term, focused research that is usually based on public financing; at least in new science-based industries as our example from the cancer medicine industry in Oslo. Again, the importance of system level agency is demonstrated, e.g. that can contribute to the commercialisation and protection of research results.

8. Conclusion

The article aims to contribute to a better understanding of regional industrial restructuring, which can also provide the basis for relevant policy lessons. The article conceptualises economic restructuring through the notion of regional industrial paths. The article proposes to combine several theoretical approaches in order to supplement the rather narrow understanding of restructuring as branching processes stemming from combinations of related technological knowledge. The article introduces human agency as an important enabler for restructuring. We have made a distinction between firm level and system level agency. These types of agency have different roles in regional economic restructuring but are both necessary for path upgrading, path diversification and path creation processes.

System level agency is important as the support of regional innovation systems is necessary for new paths to grow beyond the efforts of individual entrepreneurs, firms or organisations (Sotarauta, Beer, and Gibney Citation2017; Beer et al. Citation2018). RISs support existing industries and paths and need to be developed and transformed to be able to support path diversification and new path creation. Proactive system level agency is thus seen as increasingly important when path developments are becoming more radical and when regional innovation systems are becoming thinner. The latter means that firm level agency is less dynamic and less capable of initiating new growth paths, thus system level agency increases in importance.

The article has illustrated the conceptual analyses with four empirical examples that also form the basis for some illustrative policy lessons. We think more empirical studies could build on the proposed conceptual framework as a next step to test and possibly improve the framework, and by that developing a better tool for analysing regional industrial restructuring and in making policy adapted to the need for stimulating restructuring processes in different types of regions.

However, such empirical studies will demand a more nuanced operationalisation of the proposed framework. This includes in particular methods to identify firm level and system level agency, and to assess their influence on regional industrial path development.

We propose to identify firm level agency by first looking for changes among various RIS actors, i.e. firms, knowledge organisations and policy support organisations. The next step can be to examine the intention of the actors who carry out the changes. The intention of firm level actors is to strengthen an individual firm or organisation, e.g. to increase the competitiveness of a firm or the customer base of a technology centre. Such actions can have ‘system effects’, however, of an unintended nature (Normann Citation2013; Normann et al. Citation2017; Sotarauta, Beer, and Gibney Citation2017; Beer et al. Citation2018).

System level agency include activities that intend to affect the working of a RIS. These can be identified as a) the emergence of new organisations, policy instruments, regulations etc., b) new use of existing organisations, instruments etc. and c) new relations between RIS actors such as increased knowledge flows. Thus, operationalisation of agency could involve identifying RIS-changes, the actors behind these, and their intentions.

With regard to the combined effect of firm and system level agency on regional restructuring, we have pointed to regional industrial path development as a way to approach this process analytically. The main analytical distinction is between the strengthening and transformation of existing regional paths (extension and upgrading) and the development of new regional industrial paths (diversification and creation). Thus, the idea here is to search for major changes in existing industries and the emergence of new industries, but also how such transformations are accompanied by ‘systemic’ changes. One way to do this is to go ‘backward’ and analyse the firm level and system level agency that were leading to the transformations in the first place (Sydow et al. Citation2012; Pike et al. Citation2016). Our proposal for such an operationalisation of a conceptual framework should be tested and further developed in empirical studies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arne Isaksen

Arne Isaksen is professor at the University of Agder.

Stig-Erik Jakobsen

Stig-Erik Jakobsen is professor at Western Norway University of Applied Science.

Rune Njøs

Dr. Rune Njøs is researcher at Western Norway University of Applied Science.

Roger Normann

Dr. Roger Normann is CEO at the research institute Agderforskning AS.

References

- Asheim, B. T., R. Boschma, and P. Cooke. 2011. “Constructing Regional Advantage: Platform Policies Based on Related Variety and Differentiated Knowledge Bases.” Regional Studies 45 (7): 893–904. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2010.543126

- Asheim, B. T., and A. Isaksen. 2002. “Regional Innovation Systems: The Integration of Local “Sticky” and Global “Ubiquitous” Knowledge.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 27: 77–86. doi: 10.1023/A:1013100704794

- Beer, A. 2014. “Leadership and the Governance in Rural Communities.” Journal of Rural Studies 34: 254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.01.007

- Beer, A., S. Ayres, T. Clower, F. Faller, A. Sancino, and M. Sotarauta. 2018. “Place Leadership and Regional Economic Development: a Framework for Cross-Regional Analysis.” Regional Studies 101:1–12. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1447662.

- Bergek, A., S. Jacobsson, B. Carlsson, S. Lindmark, and A. Rickne. 2008. “Analyzing the Functional Dynamics of Technological Innovation Systems. A Scheme of Analysis.” Research Policy 37: 407–429. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2007.12.003

- Boschma, R. 2014. “Constructing Regional Advantage and Smart Specialisation: Comparison of Two European Policy Concepts.” Scienze Regionali 13 (1): 51–68. doi: 10.3280/SCRE2014-001004

- Boschma, R., L. Coenen, K. Frenken, and B. Truffer. 2017. “Towards a Theory of Regional Diversification: Combining Insights From Evolutionayr Economic Geography and Transition Studies.” Regional Studies 51 (1): 31–45. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1258460

- Boschma, R., and K. Frenken. 2006. “Why Is Economic Geography Not an Evolutionary Science? Towards an Evolutionary Economic Geography.” Journal of Economic Geography 6 (3): 273–302. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbi022

- Boschma, R., and K. Frenken. 2011. “Technological Relatedness and Regional Branching.” In Beyond Territory. Dynamic Geographies of Knowledge Creation, Diffusion, and Innovation, edited by H. Bathelt, M. P. Feldman, and D. F. Kogler, 64–81. London and New York: Routledge.

- Carlson, B., and R. Stankiewicz. 1991. “On the Nature, Function and Composition of Technological Systems.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 1 (2): 93–118. doi: 10.1007/BF01224915

- Dawley, S., D. MacKinnon, A. Cumbers, and A. Pike. 2015. “Policy Activism and Regional Path Creation: the Promotion of Offshore Wind in North East England and Scotland.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 8 (2): 257–272. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsu036

- Duranton, G., and D. Puga. 2002. “Diversity and Specialisation in Cities: Why, Where and When Does it Matter?” In Industrial Location Economics, edited by P. McCann, 151–186. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Emirbayer, M., and A. Mische. 1998. “What is Agency?” The American Journal of Sociology 103 (4): 962–1032. doi: 10.1086/231294

- European Commission. 2012. Guide to Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisations (RIS 3). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Feldman, M. P., and D. B. Audretsch. 1999. “Innovation in Cities: Science-Based Diversity, Specialisation and Localized Competition.” European Economic Review 43: 409–429. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00047-6

- Fløysand, A., and S.-E. Jakobsen. 2016. “Industrial Renewal: Narratives in Play in the Development of Green Technologies in the Norwegian Salmon Fish Farming Industry.” The Geographicl Journal 182 (2): 140–151.

- Foray, D. 2015. Smart Specialisation. Opportunities and Challenges for Regional Innovation Policy. London and New York: Routledge.

- Garud, R., and P. Karnoe. 2003. “Bricolage Versus Breakthrough: Distributed and Embedded Agency in Technology Entrepreneurship.” Research Policy 32 (2): 277–300. doi: 10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00100-2

- Geels, F. W., and J. Schot. 2007. “Typology of Sociotechnical Transition Pathways.” Research Policy 36: 399–417. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2007.01.003

- Grabher, G. 1993. “The Weakness of Strong Ties. The Lock-in of Regional Development in the Ruhr Area.” In The Embedded Firm. On the Socioeconomics of Industrial Networks, edited by G. Grabher, 255–277. London and New York: Routledge.

- Grillitsch, M., B. Asheim, and M. Trippl. 2017. “Unrelated knowledge combinations: Unexplored potential for regional industrial path development.” Papers in Innovation Studies. Paper no. 2017/10. Circle, Lund University.

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Trippl. 2016. “Innovation Policies and New Regional growth paths: A place-based system failure framework.” Papers in Innovation Studies. Paper no. 2016/26. Circle, Lund University.

- Hekkert, M. P., R. A. Suurs, S. Negro, S. Kuhlmann, and R. E. Smiths. 2007. “Functions of Innovation Systems: A New Appraoch for Analysing Technological Change.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 74 (4): 413–432. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2006.03.002

- Isaksen, A. 2015. “Industrial Development in Thin Regions: Trapped in Path Extension?” Journal of Economic Geography 15 (3): 585–600. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbu026

- Isaksen, A. 2016. “Cluster Emergence: Combining pre-Existing Conditions and Triggering Factors.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 28 (9–10): 704–723. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2016.1239762

- Isaksen, A., and S.-E. Jakobsen. 2017. “New Path Development between Innovation Systems and Individual Actors.” European Planning Studies 25: 355–370. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1268570

- Isaksen, A., N. Kyllingstad, J. O. Rypestøl, and A. C. Schulze-Krogh. 2018, forhtcoming. “Entrepreneurial Discovery Processes in Different Regional Contexts. A Conceptual Discussion.” In Unpacking the Entrepreneurial Discovery Process – New Knowledge Emergence, Conversion and Exploitation, edited by Å Mariussen, S. Virkkala, and H. A. Finne. London: Routledge.

- Isaksen, A., and M. Trippl. 2016. “Path Development in Different Regional Innovation Systems: A Conceptual Analysis.” In Innovation Drivers and Regional Innovation Strategies, edited by M. D. Parrilli, R. D. Fitjar, and A. Rodriguez-Pose, 66–84. London: Routledge.

- Jakobsen, S.-E., M. Byrkjeland, F. O. Båtevik, I. B. Pettersen, I. Skogseid, and E. R. Yttredal. 2012. “Continuity and Change in Path-Dependent Regional Policy Development: The Regional Implementation of the Norwegian VRI Programme.” Norwegian Journal of Geograph 66: 133–143.

- Jasper, J. 2004. “A Strategic Approach to Collective Action: Looking for Agency in Social-Movement Choices.” Mobilization 9: 1–16.

- Klein Woolthuis, R., M. Lankhuizen, and V. Gilsing. 2005. “A System Failure Framework for Innovation Policy Design.” Technovation 25: 609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2003.11.002

- Landmark, K., M. Rodvelt, and S. Torjesen. 2015. “Agder as Mutual Competence Builders: Developing Sustainability as a Competitive Advantage.” In Higher Education in a Sustainable Society, edited by H. G. Johnsen, S. Torjesen, and R. Ennals, 197–205. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Martin, R. 2010. “Roepke Lecture in Economic Geography—Rethinking Regional Path Dependence: Beyond Lock-in to Evolution.” Economic Geography 86: 1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Martin, R. 2014. “Path Dependence and the Spatial Economy: A Key Concept in Retrospect and Prospect.” In Handbook of Regional Science, edited by M. M. Fischer, and P. Nijkamp, 609–629. Berlin: Springer.

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2006. “Path Dependence and Regional Economic Evolution.” Journal of Economic Geography 64 (4): 395–437. doi: 10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Miörner, J., and M. Trippl. 2017. “Paving the Way for New Regional Industrial Paths: Actors and Modes of Change in Scania’s Games Industry.” European Planning Studies 25 (3): 481–497. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2016.1212815

- Musiolik, J., J. Markard, and M. Hekkert. 2012. “Networks and Network Resources in Technological Innovation Systems: Towards a Conceptual Framework for System Building.” Technological Forecasting & Social Change 79: 1032–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2012.01.003

- Neffke, F., M. Henning, and R. Boschma. 2011. “How Do Regions Diversify Over Time? Industry Relatedness and the Development of New Growth Paths in Regions.” Economic Geography 87 (3): 237–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01121.x

- Njøs, R., and J. K. Fosse. 2018. “Linking the Bottom-up and Top-Down Evolution of Regional Innovation Systems to Policy: Organizations, Support Structures and Learning Processes.” Industry and Innovation, doi:10.1080/13662716.2018.1438248.

- Njøs, R., and S.-E. Jakobsen. 2016. “Cluster Policy and Regional Development: Scale, Scope and Renewal.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 3 (1): 146–169. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2015.1138094

- Njøs, R., and S.-E. Jakobsen. 2018. “Policy for Evolution of Regional Innovation Systems: The Role of Social Capital and Regional Particularities.” Science and Public Policy 45 (2): 257–268. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scx064

- Njøs, R., and S.-E. Jakobsen. 2018. “Policy for Evolution ofRegional Innovation Systems: The Role of Social Capital and Regional Particularities.” Science and Public Policy 45 (2): 257–268. doi: 10.1093/scipol/scx064

- Normann, R. H. 2013. “Regional Leadership - A Systemic View.” Systemic Practice and Action Research 26: 23–38. doi: 10.1007/s11213-012-9268-2

- Normann, R. H., H. C. Johnsen, M. Vasström, and I. G. Johnsen. 2017. “Emergence of Regional Leadership - a Field Approach.” Regional Studies 51 (2): 273–284. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1182146

- Normann, R. H., M. Vasström, and H. C. Johnsen. 2016. The role of agency in regional path development. Regional Studies Associateion Annual Conference, 3–6 April. Graz, Austria.

- Onufrey, K., and A. Bergek. 2015. “Self-reinforcing Mechanisms in a Multi-Technology Industry: Understanding Sustained Technological Cariety in a Context of Path Dependency.” Industry and Innovation 22 (6): 523–551. doi: 10.1080/13662716.2015.1100532

- Petrov, A. N. 2011. “Beyond Spillovers. Interrogating Innovation and Creativity in the Peripheries.” In Beyond Territory. Dynamic Geographies of Knowledge Creation, Diffusion, and Innovation, edited by H. Bathelt, M. P. Feldman, and D. T. Kogler, 168–190. London: Routledge.

- Pike, A., D. MacKinnon, A. Cumbers, S. Dawley, and R. McMaster. 2016. “Doing Evolution in Economic Geography.” Economic Geography 92 (2): 123–144. doi: 10.1080/00130095.2015.1108830

- Simmie, J. 2012. “Path Dependence and New Technological Path Creation in the Danish Wind Power Industry.” European Planning Studies 20 (5): 753–772. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2012.667924

- Sotarauta, M., A. Beer, and J. Gibney. 2017. “Making Sense of Leadership in Urban and Regional Development.” Regional Studies 51 (2): 187–193. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1267340

- Sotarauta, M., L. Horlings, and J. Liddle. 2012. Leadership and Change in Sustanable Regional Development. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Sotarauta, M., and N. Suvinen. 2018. “Institutional Agency and Path Creation. Institutional Path From Industrial to Knowledge City.” In New Avenues for Regional Innovation Systems. Theoretical Advances, Empirical Cases and Policy Lessons, edited by A. Isaksen, R. Martin, and M. Trippl, 85–104. Berlin: Springer.

- Spigel, B. 2017. “The Relational Organization of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41 (1): 49–72. doi: 10.1111/etap.12167

- Stam, E. 2015. “Entrepreneurial Ecosystems and Regional Policy: A Sympathetic Critique.” European Planning Studies 23 (9): 1759–1769. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484

- Sydow, J., A. Windeler, G. Müller-Seitz, and K. Lange. 2012. “Path Constitution Analysis: a Methodology for Understanding Path Dependence and Path Creation.” BuR-Business Research 5 (2): 155–176. doi: 10.1007/BF03342736

- Tödtling, F., and M. Trippl. 2005. “One Size Fits all? Towards a Differentiated Regional Innovation Policy Approach.” Research Policy 34: 1203–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.respol.2005.01.018

- Tödtling, F., and M. Trippl. 2013. “Transformation of Regional Innovation Systems: From Old Leagacies to New Development Paths.” In Reframing Regional Development. Evolution, Innovation and Transition, edited by P. Cooke, 297–317. London and New York: Routledge.

- Weber, K. M., and B. Truffer. 2017. “Moving Innovation Systems Research to the Next Level: Towards an Integrative Agenda.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33 (1): 101–121. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grx002

- Zukauskaite, E., M. Trippl, and M. Plechero. 2017. “Institutional Thickness Revisited.” Economic Geography 93 (4): 325–345. doi: 10.1080/00130095.2017.1331703