Abstract

This paper provides a general overview on different perspectives and studies on social cohesion, offers a definition of social cohesion that is deeply rooted in current literature, and provides a framework that can be used to characterize social cohesion and help support resilient cities. The framework highlights the factors that play a substantial role in enabling social cohesion, and shows from which perspectives it can be fostered.

Introduction

Many initiatives are dedicated to helping cities around the world become more resilient to the physical, social and economic challenges that current societies face.Footnote1 At least a hundred of these initiatives are held in major cities,Footnote2 and many of them consider social cohesion as one of the key characteristics of a resilient city (e.g. Resilient RotterdamFootnote3).

Cities are organized in ways that both produce and reflect underlying socio-economic disparities, and that weakens the resilience of some parts as compared to others (Vale Citation2014). There is growing evidence that social infrastructure, as opposed to physical infrastructure, drives social resilience, and resilience can only remain useful as a concept and as progressive practice, if social dimensions are taken into account. This process of understanding what makes a city resilient is in its infancy, and highlights how often resilience is unclear (Sellberg, Wilkinson, and Peterson Citation2015). This fact renders the process of understanding to be delicate, as the failure of shaping fitting resilience threatens the ability of cities as a whole to function economically, socially and politically (Vale Citation2014). Multiple understandings may result in organizations cherry picking specific aspects and leaving other unaddressed, polemic turf-wars that will not result in action, and, most challenging, a lack of cohesion in attempts to achieve meaningful resilience in and across cities (Sanchez, van der Heijden, and Osmond Citation2018). The opposite is true as well, as interventions based on such understandings can promote crisis on social cohesion at various levels (Kearns and Forrest Citation2000). Social cohesion is an important construct that is at the heart of what humanity currently needs, for which there is not one universal definition or sets of tools and methods with which it can be measured (Pahl Citation1991; Friedkin Citation2004). It is a complex social construct due to the fact that different societies have different geographies, political representations, economics, and problems (Bruhn Citation2009b). On the one hand, fostering social cohesion in cities means creating societies where people have the opportunity to live together with all their differences, and, on the other hand, the way to approach unity and diversity, and the thresholds involved, is unknown to specialists (Novy, Swiatek, and Moulaert Citation2012).

To further understanding of social resilience and its social dimensions, and to design interventions for more sustainable resilient systems, this article explores the concept of social cohesion and factors that influence social cohesion to this purpose. This article contributes to the state of the art on social cohesion by summarizing how social cohesion has been defined over time, by discussing the different points of view on social cohesion and how they are linked together, and by highlighting which approaches would benefit from further research. Adding to these contributions, this paper updates current definitions of social cohesion with one that better matches the multicultural nature of current societies and their multiplicity of values. This paper also offers a framework to characterize social cohesion and help promote resilient cities, i.e. to help identify levels and possible factors related to cohesion, which need to be taken into account to help design interventions for cities to become more sustainable and resilient.

A short explanation on the method used to search for studies follows in the next section. Next, different perspectives on social cohesion (theoretical and empirical, experimental, and social network analysis) are presented, followed by a discussion on the literature where three levels emerge. The definition of social cohesion is revisited, and a framework with which to characterize social cohesion is introduced. Finally, the conclusion summarizes the major findings and provides an outlook of future work.

Method used to search for studies

The method deployed in this paper for the review of the literature on social cohesion is a two-step approach. The first step consists of reviewing top cited books on social cohesion at the time of this review to provide insights in the current state of art in the field. The second step complemented the first step by reviewing research articles relevant to the field using a fixed query as described below.

By using the Google™ search engine and searching for “books on social cohesion”, and by considering the first most cited 10, the result is a fairly up-to-date starting point (ranging from the years of publication between 1999 and 2016) (Gough and Olofsson Citation1999; Vertovec Citation2003; Reitz et al. Citation2009; Bruhn Citation2009c; Jenson Citation2010; Hickman, Mai, and Crowley Citation2012; Larsen Citation2013; Dobbernack Citation2014; Dragolov et al. Citation2016; Mizukami Citation2016). The books were then studied one by one, and the references lists of all of them were screened for a further in-depth analysis of relevant articles on the concept of social cohesion alone. This approach also indicated a relevant period from late nineteenth century and today.

The analysis done in the first step was complemented with further research on the experimental studies on social cohesion in the same period and that were not already mentioned using the previous method. This was done by searching on Google™ Scholar for experimental studies on social cohesion with the criteria “experimental” AND “studies” AND “social cohesion”. This paper considers the first relevant 100 results (from today backwards), where relevant means that the whole experiment was motivated by social cohesion and applied to humans, which discards publications that briefly mention social cohesion, study social cohesion in species other than humans, had some analysis to offer in populated areas of the world (excluding the poles), or that do not even use “social cohesion” as a term in neither the title, the abstract, or as keyword.

Perspectives on social cohesion

The books selected in the first step of the adopted method showed that research on social cohesion started from late nineteenth century, has been pursued from many different disciplinary perspectives (within Psychology, Social Psychology, Sociology, Mental Health, and Public Health), and cover different scopes (from smaller groups, to larger societal groups). Three methodological approaches have been deployed throughout the centuries: on theoretical findings and empirical research, experimental studies, and more recently social network analysis (SNA) for societies, communities, neighbourhoods, and their levels of resilience (Bruhn Citation2009a, Citation2009b). This distinction is used to structure the literature reviews chronologically for each of the approaches, as it facilitates the understanding of the level of contribution that the vast literature on social cohesion can have in the field of resilient societies.

Theoretical and empirical studies

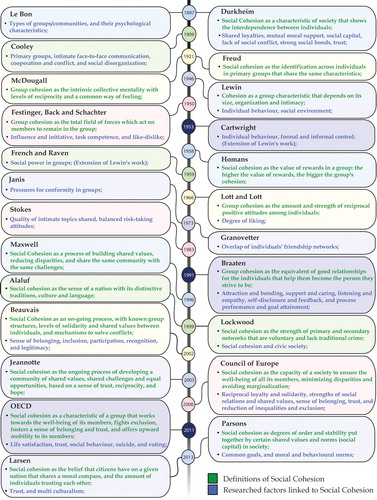

This section develops a timeline with theoretical and empirical studies. Information is presented in a way to convey three messages to the reader: (1) which researchers are, and were, prominent to the development of social cohesion as a construct, (2) how social cohesion has been defined over the centuries, both in general and specific terms, and (3) which topics/factors on social cohesion have been associated over time. This timeline is visually represented in , sums up points (1) in black, (2) in green and (3) in blue, and is developed thereafter.

Major research in social cohesion starts with Le Bon with the theory of collective behaviour and contagion (Le Bon Citation1897). He distinguishes different types of crowds/communities, and that these have a multiplicity of characteristics, opinions and beliefs that impact the individuals in a crowd. In 1897, Durkheim defines social cohesion as a characteristic of society that shows the interdependence in between individuals of that society (Berkman and Kawachi Citation2000), and coins to social cohesion (1) the absence of latent social conflict (any conflict based on for e.g. wealth, ethnicity, race, and gender) and (2) the presence of strong social bonds (e.g. civic society, responsive democracy, and impartial law enforcement) (Durkheim Citation1897). Cooley presents in 1909 the idea of primary groups, as groups having intimate face-to-face communications, dynamics of cooperation and conflict in between elements, and high numbers of friendships stemming from a substantial time spent together, which, when absent, can foster social disorganization (Cooley Citation1909). In 1921, Freud supports Le Bon's opinion about the unconscious identification of individuals, and defines social cohesion as the identification of one individual with others that share the same characteristics and provide intense emotional ties (Freud Citation1921). At the same time, McDougall defines group cohesion as the intrinsic collective mentality with levels of reciprocity and a common way of feeling and thinking (Schneider and Mcdougall Citation1921). Further ahead, Lewin defines a group as a dynamic whole with its own size, organization, and intimacy (Lewin Citation1946), and argues that individual behaviour is a product of both the person and the social environment, relating therefore agency of the individual to what the surrounding social context affords him/her.

In 1950, Festinger et al. come up with a definition of group cohesiveness that many researchers use thereafter (Festinger, Back, and Schachter Citation1950). For them, group cohesion is the desire of individuals to maintain their affiliation with a group, and this drive is measured by influence and initiative, task competence, and especially like-dislike. Cartwright endorses Lewin's theory of power field by arguing that power is not a trait of an individual alone, but from bilateral relationships that mediate formal or informal control (Cartwright and Zander Citation1953). Homans argues in 1958 that the higher the value of the rewards coming from the set of negotiated exchanges in people's friendships, the bigger the group's cohesion (Homans Citation1958). French and Raven also follow Lewin's field theory, and define seven sources of social power that affect groups’ dynamics and cohesion (connection, expertise, information, legitimacy, reference, reward, and coerciveness) (French Citation1959). Lott and Lott discover that the degree of liking is an indicator of group cohesion (Lott and Lott Citation1966), and advance a new definition of social cohesion as a group property that is induced from the amount and strength of reciprocal positive attitudes among individuals of a group (Lott and Lott Citation1961). Janis describes pressures for conformity in collective decisions observed in cohesive groups, even when these are wrong (Janis Citation1972). Granovetter complements the theory of primary groups by looking at the strength of weak ties. Social cohesion is affected by how much the friendship networks of individuals of different groups overlap (Granovetter Citation1973). In 1983, Stokes supports previous studies on the degree of cohesion and quality of information disclosed to other members, by defending that group cohesion is enhanced whenever intimate topics are shared in between individuals of the group, and whenever individuals adopt a balanced risk-taking behaviour (Stokes Citation1983). Braaten defines group cohesion as the equivalent of good relationship for an individual, which, when present, can help an individual to become the person h/she strives to be. He researches factors like group cohesion and its role in a good relationship, and creates a multidimensional model that supports the establishment, support, and achievement of a high level of cohesion (Braaten Citation1991).

Maxwell suggests a first definition for social cohesion for the Canadian Policy Research Networks:

Social cohesion involves building shared values and communities of interpretation, reducing disparities in wealth and income, and generally enabling people to have a sense that they are engaged in a common enterprise, facing shared challenges, and that they are members of the same community. (Maxwell Citation1996)

Jeannotte updates the definition of Maxwell in 2003 (and still in use today): “the ongoing process of developing a community of shared values, shared challenges and equal opportunity within Canada, based on a sense of trust, hope and reciprocity among all Canadians” (Jeannotte Citation2003). The Council of Europe defines social cohesion as “the capacity of a society to ensure the well-being of all its members, minimizing disparities and avoiding marginalization” (Europe Citation2008) with the following characteristics: (1) reciprocal loyalty and solidarity, (2) strength of social relations and shared values, (3) sense of belonging, (4) trust among individuals of society (the community), and (5) reduction of inequalities and exclusion. The Council of Europe still uses this definition today.Footnote5 The OECD presents its concise definition that relies on three independent pillars: social inclusion, social capital, and social mobility: “A cohesive society works towards the well-being of all its members, fights exclusion and marginalization, creates a sense of belonging, promotes trust, and offers its members the opportunity of upward mobility” (OECD Citation2011). Parsons researches how politics, religion, family, education, and economics are functional for a society, and considers social cohesion as levels of order and stability put together by shared norms and values in society (Parsons Citation2013). These enable individuals to identify and contribute to common goals, and share moral and behavioural norms that function as a base for interpersonal relationships. Larsen defines cohesion as the belief that citizens have on a given nation that shares a moral compass, which in turn provides a common ground for trust (Larsen Citation2013). It is then defined and measured by the amount of individuals trusting each other in some degree (national identification and belief).

Experimental studies

Experimental studies on social cohesion have an exploratory approach and can be categorized into three general types of experiments: (1) observational, (2) manipulation of group cohesion or test of its resilience, and (3) experiments fostering social cohesion. Experiments in the observational category regard measurements through observation of certain group conditions that are recorded via some quantitative method (either a scale, a questionnaire, or other form of annotation). Experiments in the manipulation of group cohesion or test of its resilience are experiments in which experimenters directly influence the cohesiveness of a group (or challenged it). Lastly, the experiments on fostering social cohesion fall into the third category, by mainly changing initial test conditions and then letting the group change its level of cohesion without further influence of the researchers.

This section develops each of the three types of experiments in subsections, each with a respective timeline and chronological presentation of studies. These timelines on experimental studies have two messages for the reader: (1) to show what the mentioned researchers consider to be relevant in social cohesion, and what they researched/measured, and (2) what researchers find. Each timeline presents a colour scheme to help the reader understand the nature of the research covered, and how often it was covered.

Observational measurement

Moreno researches the existent structures of social groups and their group dynamics based on forces of attraction and repulsion (Moreno Citation1934). He discovers in 1934 that group dynamics are shaped by the choices and patterns individuals take in regard to their relationships. Lippitt researches the impact of different leadership styles in group cohesion, and argues that group cohesion is higher when the leader is democratic, as it is highly influenced by whether individuals have their expectations met (Lippitt Citation1943; Lippitt and White Citation1943). Polansky looks at how social behaviour/interaction is influenced by other individuals, and finds out that the status in a group is an important determinant of both susceptibility and actual instigation of contagion behaviour in others (Polansky, Lippitt, and Redl Citation1950). Carron studies the theory of group dynamics, and defines a multidimensional model with several aspects linked to cohesion and the relationship between the group and the individual (Carron, Widmeyer, and Brawley Citation1985; Carron, Hausenblas, and Eys Citation2005). He defines group cohesion as a process of remaining together and united, with all the individuals’ needs met. Silbergeld researches the psychosocial atmosphere of different therapy groups, and creates a scale that measures group environment and several indicators of both group cohesion and conformity (Silbergeld et al. Citation1975; Harpine Citation2011). Mackenzie analyses both the leaders’ skills and groups’ climates, and develops a questionnaire to measure group cohesion via the individual's engagement, conflict, and avoidance (MacKenzie Citation1981; MacKenzie et al. Citation1987). Piper focuses on the perceptions that individuals have from other members of the group, the leader, and the group as a whole, and uses these to define group cohesion as the result of the set of bonds that exist in a group (Piper et al. Citation1983).

Budman relates group cohesion with individuals’ perceptions of outcome in the group, and defines three metrics to quantify social cohesion: (1) individuals acting together towards a common goal, (2) positive engagement around common goals, and (3) a vulnerable and trusting attitude that fosters the sharing of private materials (Budman et al. Citation1987; Fuhriman and Burlingame Citation1994). Brawley researches the relationship between cohesion and the behaviour of athletic teams and their individuals, and designs a questionnaire to measure multiple aspects of perceived cohesion in groups. He manages to validate both the group integration and individual attractions to the group as predictors of group cohesion (Brawley, Carron, and Widmeyer Citation1987). Meyer compares scores of two questionnaires (group environment and sport orientation) on group cohesion and attitude towards competition of athletes (Meyer Citation2000). She finds out that cohesion of co-acting teams is more strongly related to individual or social factors than it is the overall focus or goal of a team. Vianen examines the relationship between personality composition and team performance, and defends that (1) conscientiousness and agreeableness contribute to task cohesion, (2) levels of extraversion and emotional stability fostered social cohesion, and (3) task characteristics are a substantial factor influencing group personality, group dynamics, and group performance (van Vianen and De Dreu Citation2001). In 2002, Carron analyses the relationship between task cohesiveness and group success, while looking also at individuals’ perceptions of the group's cohesion and how these relate to group consistency (Carron, Bray, and Eys Citation2002). His analysis reveal that cohesiveness is a shared perception, and that there is a strong relationship between cohesion and success.

Peterson defines social cohesion as a construct linked to community participation with notions of trust, shared emotional commitment and reciprocity (Peterson and Hughey Citation2004). While furthering this notion, he investigates whether gender interacts with social cohesion to predict intrapersonal empowerment. He shows that the effects of social cohesion on intrapersonal empowerment are different for females and males, due to different participatory experiences related to social connectedness. Groenewegen studies health, well-being, and feelings of social safety, and looks at how social cohesion is affected by local green areas (Groenewegen et al. Citation2006). He argues that attractive green areas in the neighbourhood may serve as a focal point of tacit coordination for positive informal social interaction, which strengthens social ties and social cohesion. Høigaard looks at the relationship between group cohesion, group norms, and perceived social loafing, and discovers that the combination of high social cohesion, low task cohesion, and low team norms seems to underlie perceptions of social loafing (Høigaard, Säfvenbom, and Tønnessen Citation2006). Echeverría examines the association between social cohesion and several mental health and health behaviour problems (Echeverría et al. Citation2008). She associates less socially cohesive neighbourhoods with increased mental health problems and poorer health habits, regardless of race/ethnicity. Kim researches the relationship between social capital and health (public, mental, physical, health-related behaviours, and aging outcomes), and conceptualizes social capital as an attribute of a cohesive group (Kim, Subramanian, and Kawachi Citation2008). He points out that social relationships have, and produce, valued resources (capital), which exist in cohesive groups. Ball examines the associations between social participation of individuals, the neighbourhood's interpersonal trust, and physical activity among women, and argues that women are more likely to participate in leisure-time physical activity when they participate in local groups or events taking place in neighbourhoods where residents trust one another (Ball et al. Citation2010).

Mair analyses associations of neighbourhood stressors (perceived violence and disorder, and physical decay and disorder) and social support (residential stability, family structure, social cohesion, reciprocal exchange, social ties) with depressive symptoms, and argues that depressive symptoms are both positively and negatively associated with, respectively, neighbourhood stressors, and social support factors (Mair, Diez Roux, and Morenoff Citation2010). Verkuyten studies in 2010 whether assimilation of information affects the relationship between ethnic self-esteem and situational well-being (Verkuyten Citation2010). He shows that ethnic self-esteem is positively related to feelings of global self-worth and general life-satisfaction, particularly when information undermines the individual's ability to live their ethnic identity and threatens their group's positive distinctiveness. De Vries furthers the work of Groenewegen by focusing on greenspaces and in three particular mechanisms through which greenery might exert its positive effect on health: stress reduction, stimulating physical activity and facilitating social cohesion (De Vries et al. Citation2013). His study confirms that green spaces of quality reduce stress and facilitate social cohesion.

Gilligan studies in 2014 the effects of wartime violence on social cohesion, and discovers that violence-affected communities exhibit higher levels of prosocial motivation, measured by altruistic giving, public good contributions, investment in trust-based transactions, and willingness to reciprocate trust-based investments (Gilligan, Pasquale, and Samii Citation2014). At the same time, Whitton makes further analysis on the group environment questionnaire by accounting for the hierarchical nature of group data collected, and her analysis suggests that cohesion is a group-level construct (Whitton and Fletcher Citation2014). Aletta investigates an open public space used mainly as a pedestrian crossing to analyse the relationship between the audio stimuli and peoples’ behaviours (Aletta et al. Citation2016). The results support the idea that the acoustical manipulation of the existing sound environment could provide soundscape strategies capable of promoting social cohesion in public spaces. Ohmer argues that low-income communities can prevent violence and its extensive consequences by developing collective efficacy (the sharing of norms and values, trust one another, and willingness to intervene to address common problems) (Ohmer Citation2016). She proves that the increase of collective efficacy includes social capital and social cohesion.

Manipulation of group cohesion or its resilience

Festinger investigates the way that face-to-face interactions in small groups impose pressure upon individuals to follow group norms (Festinger, Back, and Schachter Citation1950). He argues that individuals have a drive to be accurately self-evaluated, and this affects group formation and group structure. In the following year, Schachter researches productivity in a group, and finds out that more cohesive groups are more successful at influencing their members (Schachter et al. Citation1951). Asch argues that people want to be liked, and therefore conform more or less depending on the forces opposing them in the group (Asch Citation1952). He finds out that 75% of the participants in his experiments change opinions at least once, especially when they are the only ones with a contrary judgement.

Milgram experiments on both the theory of pressures of conformity and on resilience of the cohesiveness of the group, and finds out that individuals go almost to any length in harming others in order to conform to given orders (Milgram Citation1965). Lott researches how different individuals’ agencies in a group affect their positive attitudes towards other members (Lott and Lott Citation1969). He also researches interpersonal attitudes that involve people who evoke attitudes, and supports the hypothesis that liked individuals can function as effective positive reinforcers and disliked individuals the opposite. Grieve examines the cohesion-performance relationship, and his results indicate that performance has more impact on cohesion than cohesion has on performance (Grieve, Whelan, and Meyers Citation2000). Blanchard researches intrinsic and extrinsic motivations’ impact on group cohesion, and finds out that individual perceptions of cohesiveness positively predict the satisfaction of the basic psychological needs of individuals (Blanchard et al. Citation2009).

Fostering of group cohesion (manipulation of initial variables)

Deutsch researches the influence of rewards on social cohesion based on cooperation and competition (Deutsch Citation1949). He finds that these have a substantial impact on social cohesion: (1) groups that are rewarded on a cooperative basis are more cohesive than those on a competition basis, and (2) group dynamics play a bigger role than the goal of the group when it comes to member's motivation to stay in the group. Sherif researches conflict, and how common tasks can mitigate conflicts and promote social cohesion (Sherif and Sherif Citation1969). He learns that common activities, both in between different groups and with all members together, result, respectively, in intergroup hostility, and intergroup cooperation (both with high in-group bonds). Hogg discusses psychological group formation, and whether this is linked to social cohesion (interpersonal attraction) or social identity (personal identification), and his findings prove that groups are formed due to motives of personal identity and not for existent social cohesion (Hogg and Turner Citation1985).

Social network analysis’ studies

Social Network Analysis (SNA) attempts to bridge the gap between different scopes of the several scientific disciplines by looking at all network levels of society – individual, micro, meso and macro (Persell Citation1990; Phillips Citation2006) – through the theories of networks and graphs. SNA characterizes network structures through individuals and the ties connecting them that represent the relationships or interactions (D’Andrea, Ferri, and Grifoni Citation2010).

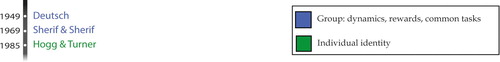

This section develops a timeline with studies on SNA. Information is presented in a way to convey two messages to the reader: (1) the researchers responsible for furthering the comprehension on social cohesion through SNA, and (2) the researched topics/factors that these studies focused on. This timeline is visually represented in , sums up points (1) in green and (2) in black, and is developed thereafter.

With the foundation of Sociometry in 1934, Moreno introduces basic analytical methods, and, twenty years later, Barnes studies social organization of class and committees while pinning SNA to explain patterns of ties, primary groups and social groups (Barnes Citation1954). Rapoport and Horvath are also among the early developers of SNA by showing that it is possible to measure higher-level networks by studying relationships’ dynamics through them (Sociometry) (Rapoport and Horvath Citation1961). Laumann creates social network surveys to display ethnographic and religious structures of different classes of social networks at higher levels than the individual (Laumann Citation1973), and, at around the same time, Granovetter contributes with his theory of the strength of weak ties, in which SNA is a central piece to link society at both micro and macro levels (Granovetter Citation1973).

White contributes in the 1960s to a well-developed methodology for SNA by developing models that combines patterns of relationships into descriptions of social structures (White, Boorman, and Breiger Citation1976). Burt describes social differentiation in terms of interpersonal patterns among individuals in a system (Burt Citation1980), i.e. some network models treat relationships among all individuals whilst others describe the relations in which an individual is involved. Krackhardt uses SNA to affirm that a better perception of the shape of informal networks can in itself be a base of power (Krackhardt Citation1990), which is perceived to be well above the power attributable by formal structural hierarchies. At the same period, Wellman and Wortley advance the definition of communities as personal networks no longer confined to geographical areas and with the capability to provide with different kinds of supportive resources (Wellman and Wortley Citation1990). Still in 1990, Bollen and Hoyle look at the same time at the perceptions of cohesion of members of a group at both the individual level (perceived cohesion is the role of the group in the life of the member) and group level (the role of members in the life of the group) (Bollen and Hoyle Citation1990).

Ahuja and Carley use SNA to develop a simulation model for individual behaviour that analyses how groups keep their distinctiveness throughout the intake of new members and ideas (Ahuja and Carley Citation1998). Moody and White define (1) the structural cohesion of a network as the minimum number of individuals that needed to be in the group for it not to become disconnected, and (2) the structural dimension of embeddedness as the tiered nesting of cohesive structures in the network (Moody and White Citation2003).

Discussion

This chapter analyses how consistently social cohesion has been defined over time, and discusses the different points of view on social cohesion and how they all link together, while arguing about the points of view that benefit from further research. Adding to this, this work updates current definitions of social cohesion with one that better matches the multicultural nature of current societies. At the end of this discussion, this paper also proposes a framework to help identify what impacts social cohesion and can thus be used to foster it.

Analysis

How social cohesion is defined

Literature shows that there is a fragmented view of what social cohesion is. It is best defined by the absence of conflict or crime (Durkheim Citation1897), a characteristic of society (Europe Citation2008), a desire for affiliation (Festinger, Back, and Schachter Citation1950), a group property (Lott and Lott Citation1966), a degree of stability (Parsons Citation2013), the strength of connections (Braaten Citation1991), as a transient state/process (Jeannotte Citation2003), and the same as good relationships or a national identity (Alaluf Citation1999) (which might not be true in current multicultural societies). Note, however, lack of consensus on defining values and factors related to the construct of social cohesion. A number of definitions that relate to economic aspects of society, such as general well-being and equal representation/opportunities in society (Jeannotte Citation2003; OECD Citation2011) have been adopted worldwide (e.g. in European Union, Canada and Australia). Such definitions have commonalities such as well-being of the members of the group, shared values such as trust, and equal opportunities in society.

Three levels in social cohesion

There are certain perspectives that are consistently used to study social cohesion, and these are seen to be levels that should be considered to acquire comprehensive understanding on the complex construct that is social cohesion. The three levels (the individual, community, and institutions) are described hereunder, and coined to the respective research(ers) and existing literature as well.

Level of the Community. The level of community is, for e.g. the shared loyalties, mutual moral support, social capital, strong social bonds, trust, social environment, formal/informal control, overlap of individuals’ friendship networks, pressures for conformity and caring, civic society, reciprocal loyalty and solidarity, strength of social relations, shared values, common goals, moral behaviour and norms, values of rewards in groups, and process performance and goal attainment.

In theoretical and empirical studies (e.g. from Durkheim (Durkheim Citation1897)), cohesion started initially to be studied through the level of the community/society. Research on the topic starts off with collective behaviour and group contagion, different groups and their characteristics/beliefs, the interdependence between individuals and the importance of other people for the individual (primary or secondary social ties to the individual and how much these overlap), the collective mentality of groups, the agency or power of the individual that is highly affected by others in the community, the errors made by groups and not by individuals alone, and the quality/intimacy of the topics shared in group. Cohesion is studied in groups of individuals, and even understood as the quantity/quality/type of social capital coming from the social relationships. The definition of social cohesion from the Council of Europe (Europe Citation2008) is linked to this level of the community through the shared values of reciprocity, loyalty, and solidarity, and the quality of social relations that includes the value of trust, a definition that is extended by Maxwell and Jeannote (Maxwell Citation1996; Jeannotte Citation2003). Adding to this level of the community are also the values of moral compass, national identification and belief.

On to experimental studies, a sizable amount of research done gives strength to the perspective on the community. Researchers focused for e.g. on the different group dynamics, group goals, and all the processes that occur in between individuals. Carron (Carron, Widmeyer, and Brawley Citation1985) and Deutsch (Deutsch Citation1949) focus on group dynamics like competition vs. collaboration towards group goals, which relates to both Mackenzie's work on group climate and Budman's experiments on individuals acting together towards common goals. Also covered are the in-group processes of group influence and leadership styles of Lippit (Lippitt Citation1943), which relates to Polansky work on the status an individual has in a group and the susceptibility and instigation of contagion behaviour in others (Polansky, Lippitt, and Redl Citation1950). These studies also relate to the group processes studied by Lott and Sherif (Lott and Lott Citation1969; Sherif and Sherif Citation1969), which looked at individuals as positive and negative reinforcers for the group, alongside inter-group processes of hostility and cooperation.

Level of the Individual. The level of the individual is, for e.g. the individuals’ intimate face-to-face communication, task competence, degree of like-dislike, initiative, individual behaviour, quality of intimate topics shared, sense of belonging, inclusion, individual participation, recognition and legitimacy.

Theoretical and empirical studies on social cohesion often take the point of view at the level of the individual. This level was first brought by Freud's work (Freud Citation1921), with the individual's identification with the group, which focuses more on the motives of the individual to be part of a group. Festinger, Back and Schachter's definition on social cohesion also strengthens Freud's argument on the role of the individual in cohesion and his/her desires to belong to a group and stay in it (Festinger, Back, and Schachter Citation1950). This level of the individual is also furthered through the importance of the degree of liking as a personal reward to belong and maintain affiliation with a group – the amount of personal reward. Braaten adds to the studies of these researchers by arguing that groups, when capable of bringing a good relationship to individuals, help them become who they desire to be (Braaten Citation1991). This desire of the individual also goes along with the argument from Beauvais (Beauvais and Jenson Citation2002) and the definition of social cohesion from the Council of Europe (Europe Citation2008), which mention the degree of belonging of the individual, and how much it affects the degree of participation in the group.

On experimental studies, researchers also cover this level well by for e.g. measuring personal feelings and general attitudes towards other individuals. Researchers like Moreno (Moreno Citation1934), Asch (Asch Citation1952) and Milgram (Milgram Citation1965) study levels of liking and disliking, degrees of likability and conformity in the group, which relate to the work of Piper on the individuals’ perceptions from other members of a group (Piper et al. Citation1983), and the work of Lott on positive attitudes towards other members (Lott and Lott Citation1969). Many of these works also precede the study on individual engagement (namely from Mackenzie and Budman – (MacKenzie et al. Citation1987; Budman et al. Citation1989)), which also consider aspects like conflict and avoidance, positive participation in group's activities, vulnerable and trusting attitudes, and the sharing of personal data in between individuals.

Level of the Institutions. The level of institutions consists of, for e.g. social disorganization, lack of social conflict, life satisfaction, voting, social behaviour, suicide rates, civic society, trust and multiculturalism, and reduction of inequalities and exclusion.

In theoretical and empirical studies, research identifies several relevant factors that play a role in social cohesion and that consistently point out the need for a balanced society with equal opportunities and rights for all citizens. Factors like impartial law enforcement, civic society, and responsive democracy are mentioned now and then by researchers like Durkheim and Lockwood, which underline the importance of social contexts and different styles of governance in variables such as wealth, ethnicity, race, and gender. Durkheim shed light on the role of the “formal” context of societies for cohesion, implying that the unequal or ill-structured context of societies (affected by, for e.g. law-making) hinders cohesion (Durkheim Citation1897). Lockwood added a distinction of social integration (actors) and system integration (structure), which covers the absence of traditional crime, voluntary associations and family organizations (civic society) (Lockwood Citation1999). This highlights the need to account for the role of formal institutions or societal bodies (that can aid citizens and intervene for them) in the debate on social cohesion. This is also coherent with the need for inclusion mentioned by Beauvais (Beauvais and Jenson Citation2002), the reduction of inequalities and exclusion mentioned by the Council of Europe (Europe Citation2008), and the equal opportunities and upward mobility from the definition of the OECD (OECD Citation2011), which can be provided by governments and formal institutions (e.g. NGO's) best.

To the best of our knowledge, the perspective formal institutions is not taken in experimental studies on social cohesion, or merely not coined to the literature on social cohesion. This means that future studies designed to research social cohesion should consider the perspective of institutions, as it does not seem to have been covered in a substantial way.

Abundancy of studies and the three levels

Theoretical and empirical studies are abundant, and so are most of the experimental ones. On experimental studies, there is a lack of research that manipulate group cohesion or its resilience (), and also research that seeks to foster social cohesion by altering initial conditions and testing these out (). The majority of the experimental studies focus on observing group dynamics and individual behaviour in regard to a group (and collecting data through scales or questionnaires), as shown in . These focus on observation of group dynamics from a distance (without disturbing the pre-existent in-group processes), and do not focus on manipulation of group cohesion or test of its resilience, or on trialling different group configurations or initial variables (and assess whether these foster or hinder cohesion). Particularly on experimental studies that aim at fostering group cohesion by manipulating initial variables only, the last recorded study is in 1985, and while this is not a scientific finding, it might be interesting to understand why this might be the case. In terms of SNA's studies, they focus on different levels and topologies of groups in society. They focus on how well or loosely coupled individual links are connected to the overall group, and on how these different topologies affect group characteristics like the overall cohesion or connectedness of that group. Studies through SNA prove to enhance the understanding of social cohesion in a way that experimental studies are not able to (for e.g. the strength of weak ties (Granovetter Citation1973) and overall ethnographic/religious social structures (Laumann Citation1973) that focus on the boundaries of groups at meso/macro levels).

As discussed in the following, it is not common to see research on social cohesion covering all three levels. Most of the studies cover the individual and the community, but they mostly miss the role of governance and formal institutions in society that are responsible for, for e.g. the social environment (and its structures, norms and values), for decision making, conflict management, social upward mobility, or human rights like voting or access to basic commodities. Researchers like Parsons consider the level of institutions in his definition (Parsons Citation2013), but do not cover the level of the individual, while others like Larsen focus on the levels of individual and community, but fail to mention the role of formal institutions (Larsen Citation2013). The three levels do appear in some research. They can be observed in several of the definitions of social cohesion widely used today, and, particularly, in those from the Council of Europe (Europe Citation2008), Jeannotte – used by the Canadian government (Jeannotte Citation2003), and from the OECD (OECD Citation2011).

Cohesion happens in the intersection of the three mentioned levels, and therefore all three levels need to be considered to understand social cohesion. An individual might have the motivation to belong to a group and the drive to participate and perform in it, but if the formal structure of the country does not allow citizens to act, then social cohesion is hampered. This means that the environment of individuals dictates their agency, i.e. the individual's freedom to act and choose that is directly conducive to the wellbeing of the individual (Ibrahim and Alkire Citation2007). For individuals to act, they need favourable communities (climate with compatible sets of norms and values) and institutions (formal structures, norms and values) that do not forbid or limit the individual's actions and choices. Further research is necessary though, in order to understand how these are linked.

Redefining social cohesion

Current definitions of social cohesion do not cover the multiplicity of values and cultures found in current societies, and, as a result, current societies might be governed and shaped around a construct that can also contribute to substantial/chronic conflict.

Larsen made a pertinent argumentation about the globalized multiculturalism and how it might go against the idea of similarity of mind and the shared values required to establish trust (and cohesion to a bigger extent) (Larsen Citation2013). He defended that heterogeneity of society and all its diversity goes against social cohesion because a cohesive society shares a moral compass (ground for trust). This implies that there cannot be generalized trust among different clusters of individuals with different cultures and values.Footnote6 Failure to achieve acceptance towards all forms of human kind and their diverse expressions leads through the course of time to a fragmented and negative cohesion (Cheong et al. Citation2007). Mixed neighbourhoods are better than separated clusters of highly cohesive communities (negative cohesion), as they offer a more open-ended engagement, vibrant opposition, and strike a balance between cultural autonomy and social solidarity (Amin Citation2002; Cheong et al. Citation2007).

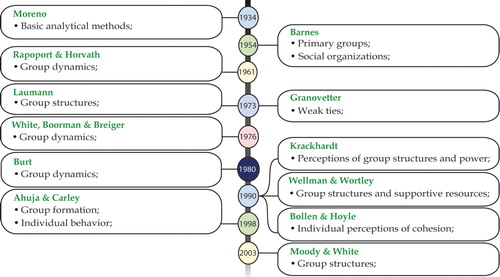

shows three current definitions widely in use today, which, however, do not fit current societies with their shifting conceptions (Bulmer and Solomos Citation2017). For e.g. these definitions mention the well-being of all its members, but while referring to the “shared values”, they do not stress the diversified nature these can have (i.e. regardless of the background of the individual), along with the tolerance required from individuals to cohabit with others fundamentally different from them; “fights exclusion and marginalization” can happen simply within “local” ethnicities as well, “reciprocity” is mentioned without stressing the agency and personal motivation of the individual to belong and act (voluntary social participation), and none of the three definitions addresses or stresses the diversity of values that determine social cohesion today (Bulmer and Solomos Citation2017).

Table 1. Definitions of social cohesion widely in use today.

An argument towards the need for an updated definition comes from the need to set more mature resilient societies in place (Sellberg, Wilkinson, and Peterson Citation2015). According to the City Resilience Framework (ARUP Citation2014), four dimensions are essential for future resilient cities: Health & Wellbeing; Economy & Society; Infrastructure & Environment; and Leadership & Strategy. Each dimension contains “drivers”, which reflect the actions cities can take to improve their resilience. One of the drivers of the City Resilience Framework is to “Promote Cohesive and Engaged Communities”:

Create a sense of collective identity and mutual support. This includes building a sense of local identity, social networks, and safe space; promoting features of an inclusive local cultural heritage; and encouraging cultural diversity while promoting tolerance and a willingness to accept other cultures.

As existing definitions fail to address this multicultural component of resilient societies, and the need for the identification and understanding of the factors that can influence means to achieve resilience in and across cities (ARUP Citation2014), this paper proposes a new definition of social cohesion. This definition is (1) based on what is overlapping in the three definitions presented in , (2) adds the role of multiculturalism, values of tolerance, voluntary participation, and diversity in societies that embellish the construct of cohesion for resilient societies of the future, and (3) associates the factor “sense of belonging” with resilient societies, as one of the factors correlated to social mechanisms of inclusion and expansion of systems built against social risk … The definition is thus:

The ongoing process of developing well-being, sense of belonging, and voluntary social participation of the members of society, while developing communities that tolerate and promote a multiplicity of values and cultures, and granting at the same time equal rights and opportunities in society.

Social cohesion framework

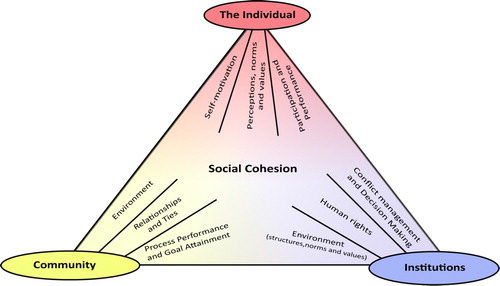

This section proposes a framework with which to analyse the levels and aspects that are not always accounted for, regardless of the perspective taken (theoretical and empirical, experimental, or SNA). This open generic framework is used to characterize social cohesion (as a complex and dynamic concept), made up of multiple and smaller levels that can help to quantify it. presents the generic social cohesion framework with the same three different but intertwined levels identified in the literature (and accounted for in the definition).

The framework shows the connections and interdependencies between the individual, the community and institutions, needed to be taken into account to better comprehend and study social cohesion in the future. For social cohesion to exist, individuals need to have motives to want to belong to a group/society, which stem from the cognitive beliefs (norms and values) they have. Perceptions of the environment and cognitive beliefs of an individual are directly linked to the informal and formal environments individuals experience and are able to experience. An individual can only feel in cohesion with the group and with the ability to participate and perform in it if the rest of the group provides with a proper environment with compatible norms and values. Equally, individuals can only take active part in a group if public laws, regulations, norms and values allow them to. If the person faces inequality, lack of representation and support of her position within a group or any deeply rooted conflict, then her personal drive to stay in the group is likely to fade away. It is therefore difficult to impact one of the three identified levels without ending up impacting one or more factors of any other level, and as such, the framework depicts this intersection.

Each factor shown in the framework, and belonging to a different level, is important to social cohesion and is inferred from the literature. At the level of the community, the factor of social environment is related to the social climate that a group has, and can be associated with the research done on for e.g. shared norms and values (Jeannotte Citation2003), formal/informal control (Cartwright and Zander Citation1953), friendship networks (Granovetter Citation1973), pressures for conformity and caring (Janis Citation1972), or civic society (Lockwood Citation1999). The factor of relationships and ties (community) regards the capital that the members of a group get, and is linked to for e.g. social capital, trust (Larsen Citation2013), reciprocal loyalties and solidarity (Europe Citation2008), moral support (Durkheim Citation1897), or value of rewards in the group (Homans Citation1958). The third factor defined at the community level (process performance and goal attainment) regards the performance of the group and its common objectives, being thus linked to common goals and moral behaviours/norms (Parsons Citation2013).

On the level of the individual, the mentioned factors (self-motivation, perceptions, norms and values, and participation and performance) are also linked to what is done so far. The factor of self-motivation relates to the reasons that lead the individual to be in a group, and links to the researched topics of for e.g. intimate face-to-face communication (Cooley Citation1909), quality of intimate topics shared (Stokes Citation1983), and recognition and legitimacy (Beauvais and Jenson Citation2002). The factor of perceptions, norms and values regards the individual view the individual has over the group he is in and his own belief system, being thus pinned to the research done on for e.g. degree of like-dislike (Lott and Lott Citation1966), and sense of belonging (Europe Citation2008). The last factor on the level of the individual is participation and performance, regards the drive that the individual has to act and take responsibility in the group, and can be linked to the research done on for e.g. initiative (Lockwood Citation1999), individual participation (Braaten Citation1991), task competence (Festinger, Back, and Schachter Citation1950), and individual behaviour (Cartwright and Zander Citation1953).

The last level, the one on institutions, defines the factors of conflict management and decision making, human rights, and environment (structures, norms and values). The factor of conflict management and decision making is considered as the governance of formal institutions in society, and can be associated with for e.g. social disorganization or conflict (Cooley Citation1909), and the reduction of inequalities and exclusion (Maxwell Citation1996; Europe Citation2008). The factor on human rights regards the agency, access and freedom of the individual while in a group/society, and research done in this direction is for e.g. voting (OECD Citation2011). Lastly, the factor of environment (structures, norms and values) regards the formal institutions and actors in society that are responsible for its upkeep, and can be coined to the research done on for e.g. social stability (Parsons Citation2013), suicide rates (OECD Citation2011), trust and multiculturalism (Larsen Citation2013), and civic society (Lockwood Citation1999).

The factors included in each of the three levels propose measures to impact and measure cohesion, while being at the same time generic enough to be extended by other factors not currently mentioned for clarity purposes.

Conclusion

This paper explores the social construct of social cohesion in relation to its potential to influence developments within the context of resilient cities and the social systems responsible for the formation of the resilient societies of the future. It presents a comprehensive survey of studies on social cohesion, while highlighting different perspectives of social cohesion, the aspects they study, their findings, and how researchers have defined social cohesion over time.

The construct social cohesion has been studied extensively over centuries, particularly through the perspective of theoretical and empirical studies, but also through experimental studies that measure social cohesion through observation. Different approaches in experimental studies (to observe and measure, influence group cohesion or its resilience, and fostering social cohesion) also point to a plurality of ways to study social cohesion. More recently SNA has added new insights to this construct.

This paper identifies a gap between definitions for social cohesion currently in use in societies and the current goal for resilient cities on the promotion of cohesive and engaged communities. This paper introduces a new definition of social cohesion, and a framework, to identify levels and possible factors related to cohesion in the context of resilient cities. The open framework is based on the literature and distinguishes three levels that should be taken into account in future studies to design and explore the impact of interventions on social cohesion. Note that the framework is not presented with an extensive list of all possible relevant factors, but is designed to be extensible.

Future research will address the influence of and between each of the levels on the design and implementation of interventions for social cohesion.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Xavier Fonseca is a researcher and PhD candidate at Delft University of Technology. He addresses sociotechnical challenges in societies in The Netherlands and Portugal via serious games. He is researching serious game design as a way to test whether meaningful social interaction can be fostered with implications for social cohesion. Current interests are on serious game design, game development, and research on HCI. Professional and academic experiences also include IoT and high-performance computing (e.g. embedded programming, multi-threaded highly optimized applications, multi-processor architectures, and GPGPU applications). His professional experience abroad covers Portugal, India, Germany and the Netherlands, as a result of which he has an extensive professional network.

Stephan Lukosch is associate professor at the Delft University of Technology. His current research focuses on designing engaging environments for participatory systems. In participatory systems' new social structures, communication and coordination networks are emerging. New types of interaction emerge that require new types of governance and participation. Enabled by technology, these structures span physical, temporal and relational distance in merging realities. Using augmented reality, he researches environments for virtual co-location in which individuals can virtually be at any place in the world and coordinate their activities with others and exchange their experiences. Using serious games, he researches on how to create effective training or assessment environments.

Frances Brazier is a full professor in Engineering Systems Foundations at the Delft University of Technology, as of September 2009, before which she chaired the Intelligent Interactive Distributed Systems Group for 10 years within the Department of Computer Science at the VU University Amsterdam. She holds an MSc in Mathematics and a doctorate in Cognitive Ergonomics from the VU Amsterdam. Parallel to her academic career, she co-founded the first ISP in the Netherlands: NLnet and later NLnet Labs. She is currently a board member of the NLnetLabs Foundation. She has over 200 refereed papers, has served on many programme committees, and is currently a member of 3 editorial boards – Artificial Intelligence for Engineering Design, Analysis and Manufacturing (Cambridge University Press), the Requirements Engineering Journal (Springer), and Birkenhauser's Autonomic Computing series.

ORCID

Xavier Fonseca http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0558-3172

Stephan Lukosch http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7203-2034

Notes

1. http://www.100resilientcities.org/about-us/, 100 Resilient Cities – Rockefeller Foundation (100RC).

2. http://www.100resilientcities.org/cities/, Member cities in the 100 Resilient Cities network.

3. https://www.resilientrotterdam.nl/en/rotterdam-resilient-city/, Main focus areas of Resilient Rotterdam.

4. https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/national_identity, definition of national identity, last visited on 22 January 2018.

5. http://www.coe.int/t/dg3/, last visited on 22 January 2018.

6. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/morality, definition of morality, last visited on 22 January 2018.

References

- Ahuja, Manju K., and Kathleen M. Carley. 1998. “Network Structure in Virtual Organizations.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 3: 0–0. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.1998.tb00079.x.

- Alaluf, Mateo. 1999. “Séminaire: ‘Evolutions démographiques et rôle de la protection sociale: le concept de cohésion sociale’”.

- Aletta, Francesco, Federica Lepore, Eirini Kostara-Konstantinou, Jian Kang, and Arianna Astolfi. 2016. “An Experimental Study on the Influence of Soundscapes on People’s Behaviour in an Open Public Space.” Applied Sciences 6: 1–12. doi: 10.3390/app6100276

- Amin, Ash. 2002. “Ethnicity and the Multicultural City: Living with Diversity.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 34 (6): 959–980. doi: 10.1068/a3537

- Asch, Solomon E. 1952. “Group Forces in the Modification and Distortion of Judgments.” In Social Psychology, 450–501. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Ball, Kylie, Verity J. Cleland, Anna F. Timperio, Jo Salmon, Billie Giles-Corti, and David A. Crawford. 2010. “Love Thy Neighbour? Associations of Social Capital and Crime with Physical Activity Amongst Women.” Social Science & Medicine 71: 807–814. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.041.

- Barnes, John Arundel. 1954. Class and Committees in a Norwegian Island Parish. New York: Plenum.

- Beauvais, Caroline, and Jane Jenson. 2002. Social Cohesion: Updating the State of the Research. Ottawa, ON: CPRN.

- Berkman, Lisa F., and Ichiro Kawachi. 2000. Social Epidemiology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Blanchard, Céline M., Catherine E. Amiot, Stéphane Perreault, Robert J. Vallerand, and Pierre Provencher. 2009. “Cohesiveness, Coach’s Interpersonal Style and Psychological Needs: Their Effects on Self-Determination and Athletes’ Subjective Well-Being.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 10: 545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.02.005

- Bollen, Kenneth A., and Rick H. Hoyle. 1990. “Perceived Cohesion: A Conceptual and Empirical Examination.” Social Forces 69: 479–504. doi:10.1093/sf/69.2.479.

- Braaten, Leif J. 1991. “Group Cohesion: A New Multidimensional Model.” Group 15: 39–55. doi: 10.1007/BF01419845

- Brawley, Lawrence R., Albert V. Carron, and W. Neil Widmeyer. 1987. “Assessing the Cohesion of Teams: Validity of the Group Environment Questionnaire.” Journal of Sport Psychology 9: 275–294. doi: 10.1123/jsp.9.3.275

- Bruhn, John. 2009a. “Cohesive Communities.” In The Group Effect: Social Cohesion and Health Outcomes, 79–101. Arizona: Springer.

- Bruhn, John. 2009b. “The Concept of Social Cohesion.” In The Group Effect, 31–48. Arizona: Springer.

- Bruhn, John. 2009c. The Group Effect. Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Budman, Simon H., Annette Demby, Michael Feldstein, Jose Redondo, Bruno Scherz, Michael J. Bennett, Geraldine Koppenaal, Barbara Sabin Daley, Mary Hunter, and Jane Ellis. 1987. “Preliminary Findings on a New Instrument to Measure Cohesion in Group Psychotherapy.” International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 37: 75–94. doi:10.1080/00207284.1987.11491042.

- Budman, S. H., S. Soldz, A. Demby, M. Feldstein, T. Springer, and M. S. Davis. 1989. “Cohesion, Alliance and Outcome in Group Psychotherapy.” Psychiatry 52: 339–350. doi: 10.1080/00332747.1989.11024456

- Bulmer, Martin, and John Solomos. 2017. Multiculturalism, Social Cohesion and Immigration: Shifting Conceptions in the UK, Ethnic and Racial Studies. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Burt, Ronald S. 1980. “Models of Network Structure.” Annual Review of Sociology 6: 79–141. doi: 10.1146/annurev.so.06.080180.000455

- Carron, Albert V., Steven R. Bray, and Mark A. Eys. 2002. “Team Cohesion and Team Success in Sport.” Journal of Sports Sciences 20: 119–126. doi:10.1080/026404102317200828.

- Carron, Albert V., Heather A. Hausenblas, and Mark A. Eys. 2005. Group Dynamics in Sport. Glenview, IL: Fitness Information Technology.

- Carron, Albert V., W. Neil Widmeyer, and Lawrence R. Brawley. 1985. “The Development of an Instrument to Assess Cohesion in Sport Teams: The Group Environment Questionnaire.” Journal of Sport Psychology 7: 244–266. doi: 10.1123/jsp.7.3.244

- Cartwright, Dorwin, and Alvin Zander. 1953. Group Dynamics Research and Theory. Vol. xiii. Oxford, England: Row, Peterson.

- Cheong, Pauline Hope, Rosalind Edwards, Harry Goulbourne, and John Solomos. 2007. “Immigration, Social Cohesion and Social Capital: A Critical Review.” Critical Social Policy 27: 24–49. doi:10.1177/0261018307072206.

- Cooley, Charles Horton. 1909. “Primary Groups.” In Social Organization: A Study of the Larger Mind, 23–31. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Council of Europe. 2008. Report of High-Level Task Force on Social Cohesion: Towards an Active, Fair and Socially Cohesive Europe.

- D’Andrea, Alessia, Fernando Ferri, and Patrizia Grifoni. 2010. “An Overview of Methods for Virtual Social Networks Analysis.” In Computational Social Network Analysis, 3–25. London: Springer.

- Deutsch, Morton. 1949. “An Experimental Study of the Effects of Cooperation and Competition upon Group Process.” Human Relations 2: 199–231. doi: 10.1177/001872674900200301

- De Vries, Sjerp, Sonja M. E. van Dillen, Peter P. Groenewegen, and Peter Spreeuwenberg. 2013. “Streetscape Greenery and Health: Stress, Social Cohesion and Physical Activity as Mediators.” Social Science & Medicine 94: 26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.030

- Dobbernack, Jan. 2014. The Politics of Social Cohesion in Germany, France and the United Kingdom. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dragolov, Georgi, Zsófia S. Ignácz, Jan Lorenz, Jan Delhey, Klaus Boehnke, and Kai Unzicker. 2016. Social Cohesion in the Western World: What Holds Societies Together: Insights from the Social Cohesion Radar. AG Switzerland: Springer.

- Durkheim, Emile. 1897. Le suicide: étude de sociologie. New York, NY: F. Alcan.

- Echeverría, Sandra, Ana V. Diez-Roux, Steven Shea, Luisa N. Borrell, and Sharon Jackson. 2008. “Associations of Neighborhood Problems and Neighborhood Social Cohesion with Mental Health and Health Behaviors: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis.” Health & Place 14: 853–865. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.004

- ELAC. 2007. Social Cohesion: Inclusion and a Sense of Belonging in Latin America and the Caribbean. New York: United Nations.

- Festinger, Leon, Kurt W. Back, and Stanley Schachter. 1950. Social Pressures in Informal Groups: A Study of Human Factors in Housing. Lincoln: Stanford University Press.

- French, John R. P. 1959. Classics of Organization Theory, Chapter 6. Oslo: Institute for Social Research.

- Freud, Sigmund. 1921. Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse. Wien: Internationaler Psychoanalytischer Verlag.

- Friedkin, Noah E. 2004. “Social Cohesion.” Annual Review of Sociology 30: 409–425. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110625

- Fuhriman, Addie, and Gary M. Burlingame. 1994. Handbook of Group Psychotherapy: An Empirical and Clinical Synthesis. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Gilligan, Michael J., Benjamin J. Pasquale, and Cyrus Samii. 2014. “Civil War and Social Cohesion: Lab-in-the-Field Evidence from Nepal.” American Journal of Political Science 58: 604–619. doi:10.1111/ajps.12067.

- Gough, I., and G. Olofsson. 1999. Capitalism and Social Cohesion: Essays on Exclusion and Integration. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78: 1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469

- Grieve, Frederick, James Whelan, and Andrew Meyers. 2000. “An Experimental Examination of the Cohesion-Performance Relationship in an Interactive Team Sport.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 12 (2): 219–235. doi: 10.1080/10413200008404224

- Groenewegen, Peter P., Agnes E. van den Berg, Sjerp de Vries, and Robert A. Verheij. 2006. “Vitamin G: Effects of Green Space on Health, Well-Being, and Social Safety.” BMC Public Health 6: 149. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-149

- Harpine, Elaine Clanton. 2011. “Group Cohesion: The Therapeutic Factor in Groups.” In Group-Centered Prevention Programs for At-Risk Students, 117–140. New York: Springer.

- Hickman, Mary J., Nicola Mai, and Helen Crowley. 2012. Migration and Social Cohesion in the UK. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Hogg, Michael A., and John C. Turner. 1985. “Interpersonal Attraction, Social Identification and Psychological Group Formation.” European Journal of Social Psychology 15: 51–66. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2420150105.

- Høigaard, Rune, Reidar Säfvenbom, and Finn Egil Tønnessen. 2006. “The Relationship Between Group Cohesion, Group Norms, and Perceived Social Loafing in Soccer Teams.” Small Group Research 37: 217–232. doi: 10.1177/1046496406287311

- Homans, George C. 1958. “Social Behavior as Exchange.” American Journal of Sociology 63: 597–606. doi: 10.1086/222355

- Ibrahim, Solava, and Sabina Alkire. 2007. “Agency and Empowerment: A Proposal for Internationally Comparable Indicators.” Oxford Development Studies 35: 379–403. doi:10.1080/13600810701701897.

- Janis, Irving L. 1972. Victims of Groupthink: A Psychological Study of Foreign-Policy Decisions and Fiascoes. Vol. viii. Oxford, England: Houghton Mifflin.

- Jeannotte, M. Sharon. 2003. “Singing Alone? The Contribution of Cultural Capital to Social Cohesion and Sustainable Communities.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 9: 35–49. doi: 10.1080/1028663032000089507

- Jenson, Jane. 2010. Defining and Measuring Social Cohesion. Hampshire: Commonwealth Secretariat.

- Kearns, Ade, and Ray Forrest. 2000. “Social Cohesion and Multilevel Urban Governance.” Urban Studies 37 (5-6): 995–1017. doi: 10.1080/00420980050011208

- Kim, Daniel, S. V. Subramanian, and Ichiro Kawachi. 2008. “Social Capital and Physical Health.” In Social Capital and Health, edited by Ichiro Kawachi, S. V. Subramanian, and Daniel Kim, 139–190. New York: Springer.

- Krackhardt, David. 1990. “Assessing the Political Landscape: Structure, Cognition, and Power in Organizations.” Administrative Science Quarterly 35: 342–369. doi:10.2307/2393394.

- Larsen, Christian Albrekt. 2013. The Rise and Fall of Social Cohesion: The Construction and De-construction of Social Trust in the US, UK, Sweden and Denmark. Oxford: OUP.

- Laumann, Edward O. 1973. Bonds of Pluralism: The Form and Substance of Urban Social Networks. New York: Wiley-Interscience.

- Le Bon, Gustave. 1897. The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind. London: Fischer.

- Lewin, Kurt. 1946. “Behavior and Development as a Function of the Total Situation.” In Manual of Child Psychology, 791–844. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Lippitt, Ronald. 1943. “The Psychodrama in Leadership Training.” Sociometry 6: 286–292. doi: 10.2307/2785182

- Lippitt, Ronald, and Ralph K. White. 1943. “The “Social Climate” of Children’s Groups.” In Child Behavior and Development: A Course of Representative Studies, edited by Roger G. Barker, Jacob S. Kounin, and Herbert F. Wright, 485–508. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Lockwood, David. 1999. “Civic Integration and Social Cohesion.” In Capitalism and Social Cohesion, edited by Ian Gough, and Gunnar Olofsson, 63–84. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lott, Albert J., and Bernice E. Lott. 1961. “Group Cohesiveness, Communication Level, and Conformity.” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 62: 408–412. doi:10.1037/h0041109.

- Lott, Albert J., and Bernice E. Lott. 1966. “Group Cohesiveness and Individual Learning.” Journal of Educational Psychology 57: 61–73. doi:10.1037/h0023038.

- Lott, Albert J., and Bernice E. Lott. 1969. “Liked and Disliked Persons as Reinforcing Stimuli.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 11: 129–137. doi:10.1037/h0027036.

- MacKenzie, K. Roy. 1981. “Measurement of Group Climate.” International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 31: 287–295. doi: 10.1080/00207284.1981.11491708

- MacKenzie, K. Roy, Robert R. Dies, Erich Coché, J. Scott Rutan, and Walter N. Stone. 1987. “An Analysis of AGPA Institute Groups.” International Journal of Group Psychotherapy 37: 55–74. doi: 10.1080/00207284.1987.11491041

- Mair, Christina, Ana V. Diez Roux, and Jeffrey D. Morenoff. 2010. “Neighborhood Stressors and Social Support as Predictors of Depressive Symptoms in the Chicago Community Adult Health Study.” Health & Place 16: 811–819. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.04.006

- Maxwell, Judith. 1996. “Social Dimensions of Economic Growth”.

- Meyer, Barbara B. 2000. “The Ropes and Challenge Course: A Quasi-Experimental Examination.” Perceptual and Motor Skills 90: 1249–1257. doi:10.2466/pms.2000.90.3c.1249.

- Milgram, Stanley. 1965. “Some Conditions of Obedience and Disobedience to Authority.” Human Relations 18: 57–76. doi: 10.1177/001872676501800105

- Mizukami, Tetsuo. 2016. Creating Social Cohesion in an Interdependent World: Experiences of Australia and Japan. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moody, James, and Douglas R. White. 2003. “Structural Cohesion and Embeddedness: A Hierarchical Concept of Social Groups.” American Sociological Review 68: 103–127. doi:10.2307/3088904.

- Moreno, Jacob. 1934. Who Shall Survive?: A New Approach to the Problem of Human Interrelations. Vol. xvi (Nervous and Mental Disease Monograph Series, no. 58). Washington, DC: Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Co.

- Novy, Andreas, Daniela Coimbra Swiatek, and Frank Moulaert. 2012. “Social Cohesion: A Conceptual and Political Elucidation.” Urban Studies 49 (9): 1873–1889. doi: 10.1177/0042098012444878

- OECD. 2011. Perspectives on Global Development 2012, Perspectives on Global Development. OECD Publishing.

- Ohmer, Mary L. 2016. “Strategies for Preventing Youth Violence: Facilitating Collective Efficacy among Youth and Adults.” Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research 7 (4): 681–705. doi: 10.1086/689407

- Pahl, R. E. 1991. “The Search for Social Cohesion: From Durkheim to the European Commission.” European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes de Sociologie 32: 345–360. doi: 10.1017/S0003975600006305

- Parsons, Talcott. 2013. Social System. London: Routledge.

- Persell, Caroline Hodges. 1990. Understanding Society: An Introduction to Sociology. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Peterson, N. Andrew, and Joseph Hughey. 2004. “Social Cohesion and Intrapersonal Empowerment: Gender as Moderator.” Health Education Research 19: 533–542. doi:10.1093/her/cyg057.

- Phillips, David. 2006. Quality of Life: Concept, Policy and Practice. Oxon: Routledge.

- Piper, William E., Myriam Marrache, Renee Lacroix, Astrid M. Richardsen, and Barry D. Jones. 1983. “Cohesion as a Basic Bond in Groups.” Human Relations 36: 93–108. doi:10.1177/001872678303600201.

- Polansky, Norman, Ronald Lippitt, and Fritz Redl. 1950. “An Investigation of Behavioral Contagion in Groups.” Human Relations 3: 319–348. doi:10.1177/001872675000300401.

- Rapoport, Anatol, and William J. Horvath. 1961. “A Study of a Large Sociogram.” Behavioral Science 6: 279–291. doi: 10.1002/bs.3830060402

- Reitz, Jeffrey G., Raymond Breton, Karen Kisiel Dion, and Kenneth L. Dion. 2009. Multiculturalism and Social Cohesion: Potentials and Challenges of Diversity. Toronto: Springer.

- The Rockefeller Foundation and ARUP. 2014. City Resilience Framework. In City Resilience Index, edited by Jo da Silva. All4energy.org.

- Sanchez, Adriana X, Jeroen van der Heijden, and Paul Osmond. 2018. “The City Politics of an Urban Age: Urban Resilience Conceptualisations and Policies.” Palgrave Communications 4 (25): 1–12.

- Schachter, Stanley, Norris Ellertson, Dorothy McBride, and Doris Gregory. 1951. “An Experimental Study of Cohesiveness and Productivity.” Human Relations 4: 229–238. doi:10.1177/001872675100400303.

- Schneider, Herbert W., and William Mcdougall. 1921. “The Group Mind.” Journal of Philosophy 18: 690–697. doi: 10.2307/2939741

- Sellberg, My M., Cathy Wilkinson, and Garry D. Peterson. 2015. “Resilience Assessment: A Useful Approach to Navigate Urban Sustainability Challenges.” Ecology and Society 20 (1). doi:10.5751/ES-07258-20014 doi: 10.5751/ES-07258-200143

- Sherif, Muzafer, and Carolyn W. Sherif. 1969. “Introduction to Psychology.” In Social Psychology, edited by James O. Whittaker, 221–266. Philadelphia: Saunders.

- Silbergeld, Sam, Gail R. Koenig, Ronald W. Manderscheid, Barbara F. Meeker, and Carlton A. Hornung. 1975. “Assessment of Environment-Therapy Systems: The Group Atmosphere Scale.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 43: 460–469. doi:10.1037/h0076897.

- Stokes, Joseph Powell. 1983. “Components of Group Cohesion Intermember Attraction, Instrumental Value, and Risk Taking.” Small Group Behavior 14: 163–173. doi:10.1177/104649648301400203.

- Vale, Lawrence J. 2014. “The Politics of Resilient Cities: Whose Resilience and Whose City?” Building Research & Information 42 (2): 191–201. doi: 10.1080/09613218.2014.850602

- van Vianen, Annelies E. M., and Carsten K. W. De Dreu. 2001. “Personality in Teams: Its Relationship to Social Cohesion, Task Cohesion, and Team Performance.” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 10: 97–120. doi: 10.1080/13594320143000573

- Verkuyten, Maykel. 2010. “Assimilation Ideology and Situational Well-Being among Ethnic Minority Members.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 46: 269–275. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2009.11.007.

- Vertovec, Steven. 2003. Conceiving Cosmopolitanism: Theory, Context and Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wellman, Barry, and Scot Wortley. 1990. “Different Strokes from Different Folks: Community Ties and Social Support.” American Journal of Sociology 96: 558–588. doi: 10.1086/229572

- White, Harrison C., Scott A. Boorman, and Ronald L. Breiger. 1976. “Social Structure from Multiple Networks. I. Blockmodels of Roles and Positions.” American Journal of Sociology 81: 730–780. doi: 10.1086/226141

- Whitton, Sarah M., and Richard B. Fletcher. 2014. “The Group Environment Questionnaire: A Multilevel Confirmatory Factor Analysis.” Small Group Research 45: 68–88. doi:10.1177/1046496413511121.