Abstract

This paper builds on the idea of cross-border regional innovation system (CBRIS) to investigate the implications of global and regional changes in social, political, economic, and ecological systems on cross-border regions. In an era of increasingly abrupt changes in border permeability, CBRIS offers an intriguing context for studying such processes. Our main contribution is to define a resilient CBRIS (R-CBRIS) for sustainability based on careful reading of previous literature on resilience, sustainability, and CBRIS integration. As merging these concepts requires a sound understanding of the factors driving or constraining CBRIS integration, we conduct a systematic review of the literature to answer our main research question: what factors affect the resilience and sustainability of CBRIS? The literature reveals that the studied CBRIS are not particularly sustainable and that their resilience remains a neglected topic. This is a definite cause for concern for everyone interested in the long-term success of cross-border regions.

1. Introduction

Humanity is presently not only trespassing a number of critical biophysical boundaries, such as those in relation to carbon emissions and ecological footprint, but failing to achieve the minimum social thresholds to guarantee a ‘safe and just’ development space (O’Neill et al. Citation2018; Steffen et al. Citation2018). To move nations and regions from present trends to greater sustainability is bound to require many fundamental changes – transitions – that are all connected to one another in complex ways, including an economic transition, a technological transition, an institutional transition, and an informational transition (Gell-Mann Citation2010; Wilson G Citation2014). Technological and social innovations, such as nanotechnology and novel modes of governance, carry potential to induce such large-scale transitions in and across societies. Although every innovation must be accompanied by a careful evaluation of its impacts, they can nevertheless be important tools for staying within the safe and just space for humanity (Raworth Citation2013).

Despite the more-than-a-century-long study, defining innovation precisely remains difficult (Taylor Citation2016). Austrian economist Schumpeter (Citation1911, 66) defined innovation broadly as ‘new combinations’ of new or improved products, processes, or methods of production, new markets, new forms of organization, or even ‘conquests’ of new resources. He also distinguished invention from innovation: the former occurs when someone creates something for the first time, while the latter occurs only if the former diffuses into practice. Based on the common definitions applied across disciplines, innovation may refer to a product innovation, a process innovation, a service (delivery) innovation, an administrative innovation, an organizational innovation, a conceptual innovation, a policy innovation, or a systemic innovation (Gault Citation2018, 619). Some have also referred to innovation as a means of conflict resolution (Schulze, Stade, and Netzel Citation2014), whereby it diffuses through informal, self-organizing networks of individuals and collectives (Henry Citation2018). Consequently, an important notion in the popular ‘innovation systems’ approach is that innovations come in many forms and result from the interactions (and interdependencies) between actors who possess diverse resources and knowledge (Asheim, Grillitsch, and Trippl Citation2016).

After recognizing that increasing inclusiveness was necessary for achieving its goal of improving ‘competitiveness’ in the European Union (EU), the European Commission (EC) has been promoting regional collaboration, research, and innovation efforts for at least two decades (Pohoryles Citation2007). More recently, the EC has launched ‘place-based strategies’, or Smart Specialisation Strategies (S3), to better adjust to regional needs and potentials (European Commission Citation2014). S3 claim to embrace the unique place-based circumstances, including regional resources, competences, and decision-making power in relation to the national constitution. S3 also laid the foundation for updating the European Council's overarching goal from improving competitiveness to achieving ‘smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth’ in the EU.

Guidelines for place-based innovation and innovation policies in the EU were drafted in the EC's recent synthesis report on priority setting for regional innovation strategies (Clar Citation2018). According to the report, many regions in many European nations have succeeded in applying such place-based innovation approaches, but significant obstacles in many cases remain. The cited difficulties included shortcomings in governing for research and innovation, in broadening the understanding of innovation and innovation policies for system-level transition, in enhancing the meaningful involvement of stakeholders in innovation processes, and in harnessing synergies and complementarities between other policies (see also Asheim Citation2018). Hassink and Gong (Citation2019) also stress that innovation strategies for smart specialization continue to be projected under the most conventional model of innovation – one based on science and technology. Alternative models, such as those that could be more relevant for other-than-technological transitions, are largely absent from the strategies.

While the innovation systems approach is paving the way for implementing regional innovation policies (Asheim, Isaksen, and Trippl Citation2019), the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), each of which include a set of targets and to which world's governments signed on to in 2015, are key formulations of sustainability goals that could guide priority setting also for regional innovation policies (United Nations Citation2015; Lyytimäki et al. Citation2020). Although there is an ongoing debate about the contradictions of the SDGs and the methods for assessing progress towards achieving them (Hickel Citation2019; Citation2020; Zeng et al. Citation2020), strong sustainability, when framed as performing well on human development indicators without destructive levels of ecological impact, is arguably a result of implementing many policies in and across diverse regional contexts (Pohoryles Citation2007; Xu et al. Citation2020). In our view, such regional diversity calls for systemic approaches to implementing regional innovation policies that focus attention and action to the regionally most relevant issues and to maximizing synergies (or minimizing trade-offs) between the many goals.

Cross-border regions – areas consisting of adjacent regions belonging to more than one nation (Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013, 452) – adds another layer of complexity to studying innovation systems. However, studying cross-border regional innovation systems (CBRIS) allows for observing the influences of the different forms of interaction for cross-border integration while accounting for the roles of different cultural identities, social dynamics, political systems, economic histories, and innovation capacities (Makkonen and Rohde Citation2016). In CBRIS, the notion of ‘no size fits all’ is highlighted, and surely one of the most persistent challenges that those seeking to spur innovation in border regions are facing (Asheim Citation2018, 8).

In this paper, we stress that regional innovation must be pursued in a manner that allows for (cross-border) regions to engage with more sustainable trajectories of development. However, specific concepts, models, or frameworks for understanding the sustainability of CBRIS (or innovation systems thereof) have not been proposed. Insofar as CBRIS is concerned, we address the issue by proposing sustainability as an additional dimension to the well-known CBRIS integration model of Lundquist and Trippl (Citation2013), the focus of which has largely been on economic integration. As the long-term sustainability of any complex system depends upon its ability to adapt and transform in ever-changing environments (Elmqvist et al. Citation2019), we also harness the concept of ‘resilience’ to introduce our conceptual invention: resilient CBRIS for sustainability.

Although regional innovation (Cooke Citation1992), cross-border integration (Hansen Citation1983), resilience (Dissart Citation2003), and sustainability (Blatter Citation2000) have been on the research agenda of economic geographers and other social scientists for long, systematic efforts to combine them have not occurred. Merging them naturally requires a sound understanding of the factors driving or constraining the integration of CBRIS, potentially leading to a common innovation system. Therefore, besides introducing resilient CBRIS for sustainability, the objective of this paper is to operationalize the proposed framework by reviewing empirical case studies of CBRIS integration, first, to provide an updated synthesis of the drivers and constraints that condition the emergence of CBRIS and, second, to identify factors that affect their resilience and sustainability. We address the second part also by linking the findings from our systematic review to relevant SDGs. This allows us to identify gaps in the scholarly evidence of the integration of CBRIS beyond economic integration by focusing on what we call as sustainable integration. The review is guided by the following research questions:

What is the general status of the evidence base as regards to CBRIS integration?

What drives and constrains CBRIS integration?

How are sustainability goals reflected in literature on CBRIS integration?

What do we know about the resilience and sustainability of CBRIS?

The next section outlines the CBRIS integration model of Lundquist and Trippl (Citation2013) and elaborates it with resilience and sustainability. The sections that follow describe our methods and results. The paper concludes by answering the research questions and with a discussion on its limitations and implications.

2. Resilient cross-border regional innovation systems for sustainability

2.1. From economic to sustainable integration

The concept of CBRIS was created by applying the innovation systems approach to cross-border contexts (Trippl Citation2010). It has gained in importance as various factors, such as strong regionalization tendencies in different parts of the world, political upheavals in Central and Eastern Europe, and ongoing enlargement of the EU, has rendered current innovation systems approaches inadequate (Blatter Citation2004; Trippl Citation2010). The long-term ‘competitive edge’ of cross-border regions, according to regional and European policymakers and other stakeholders, will depend upon their ability to create an integrated cross-border region (innovation system) with considerable interaction between actors across the border (Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013).

Lundquist and Trippl (Citation2013) present a linear framework for analyzing CBRIS and their level of integration. They suggest that integration may occur in the following dimensions: economic structures, science bases, nature of linkages, institutional set-ups, policy structures, and accessibility (). A well-integrated CBRIS is expected to increase the exchange of goods, knowledge, labor, mobility, and investments, thereby creating shared growth on all sides of a border (Trippl Citation2010, 151). However, apart from economic growth, this model does not consider the sustainability of such systems. Therefore, we propose to add a seventh dimension to the framework, namely that of sustainability. This implies adjusting the focus from economic integration to sustainable integration over time and space.

Table 1. Stages and dimensions of CBRIS integration (adapted from Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013).

In ‘weakly integrated asymmetric cost-driven systems’, common sustainability goals (such as SDGs) are not guiding the setting of priorities on a cross-border scale. Thus, efforts to attach to more sustainable trajectories of cross-border development are uncoordinated and potentially undesirable – for example, increasing nature conservation on one side of the border may lead to negative ecological impact on the other due to increased extraction of natural resources (Mayer et al. Citation2005). The role of sustainability is recognized in a ‘semi-integrated emerging knowledge-driven system’, and efforts to achieve selected sustainability goals on a cross-border scale, likely those that are easiest to achieve, are emerging. In such CBRIS, progress towards greater sustainability is largely project-driven and visible through, for example, memorandums of understanding underlining the importance of social and ecological goals along with economic goals (such as the European Green Belt initiative, see Zmelik, Schindler, and Wrbka Citation2011). However, the sustainability of cross-border projects is always a cause for concern after the formal funding periods have expired (Makkonen et al. Citation2018), while memorandums of understanding may remain at the level of political rhetoric without much concrete action.

In the ‘sustainable stage’ of CBRIS integration (‘a symmetric innovation-driven system’), common cross-border policies and actions for sustainability are in place and progress is under continuous monitoring. Such sustainable integration entails aligning cross-border regional development along a coherent set of the regionally most relevant SDGs, such as initiatives targeting economic inequality across the border (SDG 8 and SDG 9Footnote1) and the establishment of common nature reserves, such as the Finnish-Russian Friendship Nature Reserve, to support life below water (SDG 13) and life on land (SDG 14). Even if there are many well-known issues with stakeholder participation in policymaking (Malkamäki et al. Citation2019; Reed et al. Citation2018), citizens’ and stakeholders’ voices are heard when determining the relevant set of sustainability goals. Because of the potential for social costs of economic growth exceeding its benefits, effectively leading to unsustainability, generating economic growth in terms of GDP is not an overriding policy priority (Archer, Kite, and Lusk Citation2020; Hickel Citation2019. However, a boost in growth and sustained well-being could result from actions that reduce inequality or enhance natural ecosystems’ ability to provide valuable 'services' (OECD Citation2015; Song Citation2018). In the best-case scenario, sustainability has been turned into a competitive advantage for the CBRIS by introducing innovations that lay a long-lasting foundation for the creation of shared value on both sides of the border, and beyond.

2.2. From a linear approach to resilience thinking

The linear stage-based approach is another weakness of the existing framework underlying CBRIS integration. It implicitly assumes that advancing from one stage to another is an inherently positive step without accounting for the possibility of non-linear development. For example, in relation to the accessibility dimension, as noted by Kratseva (Citation2020) and Durand and Perrin (Citation2018), border effects are reduced at times (for example, due to the Schengen Agreement) leading to increased permeability of the border, and at times they are reinforced or reinstated leading to a decrease in border permeability (for example, due to hardening border control in the EU due to the contemporary immigrant issue, in the US due to 9/11, and at the US-Mexico border due to the US presidential election in 2016, or due to EU-Russia sanctions, Brexit, or Covid-19 pandemic). However, a ‘resilient’ CBRIS would possess capacity to respond to such shocks (or trends thereof) and to reshape its structures and processes, so that neither internal nor external changes result in undesirable instability but rather in desirable renewal. Thus, understanding resilience is key for understanding how sustainable integration of CBRIS unfolds.

Contrary to the linear CBRIS integration framework, resilience is distinguished from the pursuit of stable states for being an inherently dynamic concept. It is essentially about cultivating the capacity to continue to live and develop with change, incremental and abrupt, expected and surprising (Folke Citation2016, 3). As regards to the nature of ‘change’, and as discussed above, some of the most sweeping changes affecting CBRIS integration may nowadays emerge as surprises from global phenomena, such as financial crashes, disease outbreaks, or global warming (Centeno et al. Citation2015; Keys et al. Citation2019).

Although the concept of resilience originates from the ecological literature on system stability (Holling Citation1973), as in fact does sustainability (Pohoryles Citation2007), it has grown into an umbrella concept for rethinking and reshaping development towards more sustainable trajectories (Bousquet et al. Citation2016). Its importance for the problem of sustainability has nevertheless been recognized for at least three decades (Common and Perrings Citation1992). However, for understanding how resilience links to sustainability, recognizing the difference between adaptability and transformability is important. While the former refers to the ability of actors in a given system to influence resilience, the latter translates into their ability to create a fundamentally new system when the sweeping changes have made or are gradually making the existing system untenable (Walker et al. Citation2004).

Distinguishing between these concepts is highly relevant for the sustainable integration of CBRIS in the sense that it is often the adaptability of an existing system that prevents the more fundamental shifts to sustainability (Olsson, Galaz, and Boonstra Citation2014). Even if a ‘paradigm shift’ to pursue sustainability (e.g. SDGs) would occur (cf. ‘semi-integrated emerging knowledge-driven CBRIS’), achieving greater sustainability may entail the complete transformation of the often persistent institutions in the existing system, be they practices (e.g. indicators used to track progress), taboos (e.g. structural discrimination), worldviews (e.g. modernism), or power asymmetries (e.g. the uneven abilities of actors to influence both conduct and context) (Boonstra Citation2016; Kaika Citation2017). Therefore, ‘resilience thinking’ emphasizes the need for transformation rather than mere persistence to disturbances (Folke Citation2016).

Unlike sustainability, resilience is essentially an apolitical attribute of a system (Elmqvist et al. Citation2019). It can be either desirable or undesirable. Whereas undesirable resilience could conflict with achieving sustainability goals, desirable resilience could translate into managing for resilience in order to stay on a more sustainable trajectory of development. Determining resilience and its desirability would in turn depend upon an analysis ‘of what, ‘to what, and ‘for whom’, as numerous examples of resilient systems following ‘unsafe and unjust’ pathways exist (Carpenter et al. Citation2001; Keys et al. Citation2019). Applying resilience thinking to CBRIS integration requires an understanding of the desirable conditions and factors driving (or constraining) their ability to innovate. Innovation is an important means for managing both adaptability and transformability, and by managing resilience, it is not only possible to enhance the probability of sustaining desirable pathways of development, but to intervene when and if innovations act against sustainability once they have been scaled up (Walker et al. Citation2004; Olsson, Galaz, and Boonstra Citation2014). However, as there are major barriers to triggering and coordinating system-level behavioral changes proactively (Beck Citation2010; Gifford Citation2011), one would expect most transformations, to greater sustainability or otherwise, to occur relatively abruptly as reactions to external forces or bottom-up pressure (for example, due to Covid-19 pandemic or disruptive innovations, respectively) when resilience is reduced (Elmqvist et al. Citation2019).

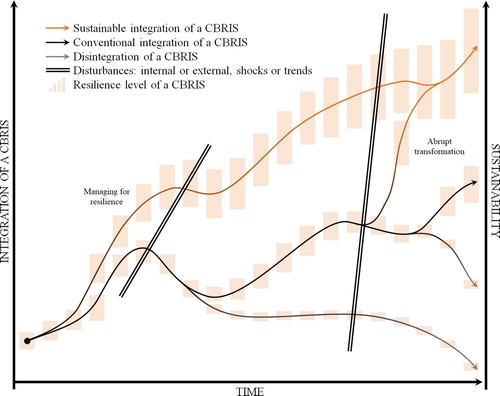

Following this line of reasoning, hypothesizes the connections between integration, resilience, and sustainability of a single CBRIS. Managing for resilience proactively through sustainable integration could translate into resilience that accumulates over time and is desirable in the sense that it serves for greater sustainability (manifest as the height of the bars in ). Such pathways are likely to enhance and expedite adaptability to various disturbances. Alternatively, a CBRIS following a more conventional integration pathway could abruptly transform toward sustainability when resilience is reduced due to a disturbance, adapt and continue on its historical pathway that is neither particularly sustainable nor resilient, or disintegrate.

Figure 1. Hypothesizing the connections between resilience, sustainable integration, and sustainability of a cross-border regional innovation system (adapted from Elmqvist et al. Citation2019).

Whereas our take on resilience draws on the emerging body of literature on social-ecological systems, resilience has been gaining ground also in describing the ‘durability’ of regional economic systems. The interpretation of such ‘regional resilience’ has been given different connotations (Hassink Citation2010; Halonen Citation2019), but essentially, as stated by Martin and Sunley (Citation2015, 4), it is similarly concerned with the capacity of a region to withstand or recover from shocks or to swap development pathways. According to Boschma (Citation2015, 734), regional resilience should also be understood as a continuous process rather than as a fixed property of a region. Although social-ecological resilience and regional resilience are complementary perspectives to thinking about development, the former places a stronger emphasis on bringing human development back into balance with the living world – that is, it views cross-scale social, economic, and ecological resilience as tightly coupled notions (Folke et al. Citation2011).

Insofar as resilience thinking is concerned, it is particularly relevant for border regions. On the one hand, their economies often rely on cross-border relations, such as commuting and trade, and are, thus, particularly vulnerable to decreases in border permeability (Prokkola Citation2019). On the other hand, they are deemed as ‘innovative platforms for multidimensional integration processes, which are needed for more sustainable ways of living’ (Blatter Citation2000, 402). As such, CBRIS, and particularly their sustainable integration, can indeed create new ‘spaces for resilience’ (cf. Blatter Citation2004). Analogously, by adapting resilience thinking to cross-border contexts, we define cross-border regional resilience as the ability of actors on all sides of the border to continually and jointly uphold various capacities that allows for recovering (adapting) and renewing (transforming) in ever-changing environments and disturbances in cross-border integration. A resilient CBRIS (R-CBRIS) for sustainability, in turn, is basically doing what it says to be doing: innovating in the broadest possible sense, but only after having determined a coherent set of regionally relevant sustainability goals.

The specific means of managing for resilience and sustainability in CBRIS are out of the scope of this paper. However, literature has identified fail-to-safe experimentation, inclusive and interactive innovation spaces, collaborative governance, and intentional diversity, redundancy, and connectivity as possible ways of managing for both (Elmqvist et al. Citation2019; Olsson, Galaz, and Boonstra Citation2014; Seyfang and Haxeltine Citation2012). The next section outlines the method for conducting a systematic review of the factors driving and constraining CBRIS integration in the first place, and for applying the above framework to address the other objectives of this paper.

3. Methods

Systematic reviews intend to provide a comprehensive assessment of available literature on a given question. Many advantages exist for conducting the review systematically in comparison to conventional reviews, including the reduction of selection bias when searching for and screening of literature along with improved transparency and replicability (Pullin and Stewart Citation2006).

We formulated specific inclusion criteria for a systematic search and screening of relevant studies. To be included in our sample, each study must have (a) dealt with an innovation referring to it explicitly (b) been in a cross-border region. These innovations did not have to be new to the world if they were new to the given cross-border region. In addition, each study (c) must have used empirical primary data, whether longitudinal or cross-sectional, in its analysis.

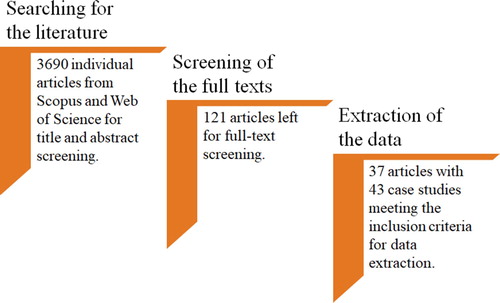

We considered peer-reviewed studies available in Scopus and Web of Science databases. The literature searchFootnote2 was conducted in English in May 2018, although German, Portuguese, Spanish, and Russian (following the language proficiency of the authors) studies identified in these searches were also included in the screening process. The search identified 3690 individual articles. We utilized Abstrackr software for the initial screening of abstracts and undertook a test for a subset of 50 randomly selected studies to ensure inter-reviewer consistency by calculating Randolph's free-marginal multi-rater kappa (Randolph Citation2008). The acceptable minimum threshold for the kappa value (0.7) (Brennan and Prediger Citation1981) was reached on the second try, after differences in the initial interpretation were deliberated. As a result of the initial screening, we identified 121 articles that seemed to be suitable for our purposes. After full text screening and careful consideration to exclude articles that did not, after all, fit our inclusion criteria, 37 articles were kept for the final review. These studies comprise our data, which were collected with the help of a specifically designed sheet for data extraction following the common principles of a qualitative meta-synthesis (Walsh and Downe Citation2005) (see Supplementary material). Some studies presented multiple case studies, which raised the final number of our sample to 43 cases. summarizes the main stages of the review process.

4. Results

4.1. Description of the sample: temporal and geographical distribution of articles

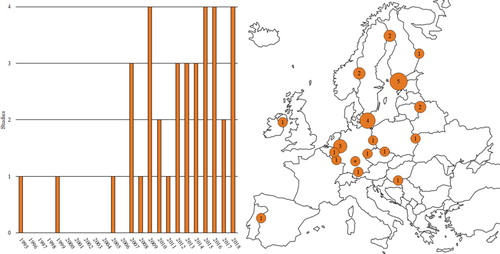

illustrates the publication years of the 37 articles in our sample. The earliest study was published in 1995, but it took considerable time for the topic to gain more traction: articles have been published yearly only since 2007. Hence, the scholarship on innovation and innovation systems in cross-border regions has been on the rise for a relatively short time, yet it remains fairly niche. Geographically, a vast majority of the studied cases are located in Europe. Out of 43 CBRIS cases, 35 are located in Europe and only four in North America, three in Latin America, one in Africa, and one in Asia (). Thus, the literature on the topic is highly Eurocentric concentrating particularly to Nordic and Northern European cases. This result is more likely reflecting the institutional backgrounds of the authors active in the field of innovation studies in cross-border contexts than the lack of representative cases in other parts of Europe and globally.

4.2. Analysis of the dimensions of sustainable integration of CBRIS

In the following, we identify drivers and constraints of sustainable integration of CBRIS, based on our sample, under each of the seven dimensions in .

4.2.1. Economic synergies

Twenty-five cases out of the 43 report on the role of economic structure concerning the emergence of CBRIS. Strong synergies were identified in 16 cases, 14 of which report that such synergies were either major or minor drivers of integration (see Supplementary material). Complementarity of economic structures on both sides of the border, including similar economic activities or socio-economic conditions, generally contributes to the emergence of CBRIS (Lee Citation2009; Knippschild and Wiechmann Citation2012; de Souza et al. Citation2014). However, strong economic synergies may also have a constraining effect on integration; e.g. van den Broek and Smulders (Citation2015) report on how strong synergies have increased competition and, consequently, increased the protection of domestic production, while Sarmiento-Mirwaldt and Roman-Kamphaus (Citation2013) observe that if regions on both sides of the border are in an equally weak economic situation, the low economic activity as a starting point (accompanied by highly centralized national economies) constrains integration. Interestingly, our results are rather mixed with regard to the role of weak economic synergies in the cross-border regions. Nine cases deal with such events, five of which consider their role as either a major or minor constraint. The incompatibility of business structures, such as different-sized firms and strong technological investments in domestic production in one of the countries, is viewed as a particularly major barrier (Domínguez, Noronha Vaz, and Vaz Citation2015; Galko, Volodin, and Nakonechna Citation2015).

4.2.2. Research synergies

The level of research synergies was reported in 20 cases included in this study. Strong research synergies in research structures in the cross-border regions were reported in 13 cases, where the science base and knowledge infrastructures are considered major or minor drivers. The existence of high-ranking universities and scientific projects were positive drivers for integration efforts in cross-border regions through integrated research structures (Lepik and Krigul Citation2009, Citation2015; Medeiros Citation2017). Fruitful synergies and functional proximity were identified particularly in high-tech industries such as biotechnology and the IT-sector (Coenen, Moodysson, and Asheim Citation2004; Lee Citation2009; Hansen Citation2013). Seven cases reported a lack of synergies in research structures, which were systematically linked with a weak integration level. Differences in knowledge bases across the border, a lack of common goals, economic resources devoted to research, and the underestimation of science are factors that particularly constrain integration (Pikner Citation2008; Galko, Volodin, and Nakonechna Citation2015; Lavrinenko et al. Citation2016; Makkonen and Weidenfeld Citation2016).

4.2.3. Knowledge flows

Ten out of 26 reported cases concerning knowledge flows considered the absence, weakness, or vagueness of knowledge interaction either as a minor (three) or major (seven) constraint (Perkmann Citation2007; Sarmiento-Mirwaldt and Roman-Kamphaus Citation2013; Lavrinenko, Jefimovs, and Teivāns-Treinovskis Citation2018). For example, investments in concrete infrastructure development over human capacity and the fact that knowledge flows between actors tend to happen at the personal level were seen as constraints (Makkonen et al. Citation2018, 147). In four out of the five cases where knowledge flows were perceived as more embedded in national contexts, the established links served as drivers for integration (Perkmann Citation2007; Knippschild and Wiechmann Citation2012), but Miörner et al. (Citation2018) acknowledge this to influence actors’ adaptation to the existing system rather than triggering its renewal. Contrarily, genuinely interactive links are drivers for the emergence of CBRIS in ten cases, and particularly relevant in the context of high-tech industries with a strong scientific publishing culture (Hansen Citation2013; Makkonen and Weidenfeld Citation2016). However, there is also evidence that intensive knowledge flows do not necessarily result in creating common ’know-how’ (Pikner Citation2008, 215).

4.2.4. Institutional support

A total of 39 studies reported on the role of institutional set-up in cross-border regions, 19 of which perceived a particular institutional set-up as a major or minor driver for integration (Coenen, Moodysson, and Asheim Citation2004; de Souza et al. Citation2014; Jakola and Prokkola Citation2018), whereas 20 considered it a major or minor constraint (Perkmann Citation2007; Sarmiento-Mirwaldt and Roman-Kamphaus Citation2013; Domínguez, Noronha Vaz, and Vaz Citation2015). A clear link seems to exist where a strong institutional set-up characterized e.g. by a low degree of institutional distance, high acceptance of integration processes, and existence of key bridging organizations positively influence the emergence of CBRIS (Lee Citation2009; Krigul Citation2011). The weak institutional synergies with a high degree of institutional distance, the absence of a cross-sectoral coordination body, and low acceptance of integration processes constrain the integration efforts (Peberdy and Crush Citation2001; Medeiros Citation2014; Lepik and Krigul Citation2015). However, a weak institutional set-up may also act as a minor driver for integration in cases of resultant high levels of citizen interest and local participation (Carter and Ortolano Citation2000; Kranjac, Dickov, and Sikimic Citation2013).

The difference in legislation and various associated legal constraints, such as limits of free cross-border movement and rigid national orientation of development programs, were among the factors limiting efforts to advance integration (Peberdy and Crush Citation2001; Judkins and Larson Citation2010; Lavrinenko et al. Citation2016). Another significant reported reason lies in the certain degree of institutional incompatibility and lack of cooperation among countries, which often makes it difficult to find common ground and understanding required for the integration of institutions (Hassink, Dankbaar, and Corvers Citation1995; Francis, Mukherji, and Mukherji Citation2009; Sarmiento-Mirwaldt and Roman-Kamphaus Citation2013; Domínguez, Noronha Vaz, and Vaz Citation2015). Additionally, cultural and linguistic barriers along with informal institutional hindrances may reinforce these constraints and increase the transaction costs of integration efforts (Heenan Citation2009; Hahn Citation2013; Lepik and Krigul Citation2015; Berrová, Jeřábek, and Jüttler Citation2016). Contrarily, other studies reported cultural and language similarities and shared values as major drivers for integration, which may support mutual interest and efficient communication and contribute to a generally positive experience and commitments to integration (Bagchi-Sen and MacPherson Citation1999; Coenen, Moodysson, and Asheim Citation2004; Pikner Citation2008; Krigul Citation2011; Jakola and Prokkola Citation2018). Furthermore, supportive institutional and governance structures may facilitate integration through access to specific cross-border cooperation funding (e.g. INTERREG), ease the implementation of joint programs, and encourage closer cooperation between the public and private sectors (Lee Citation2009; Knippschild and Wiechmann Citation2012).

4.2.5. Policy support

Policy structures were mainly seen as constraints (a major constraint in eleven cases and a minor one in twelve cases), whereas only nine cases (five as major and four as minor drivers) considered them drivers of integration. The reasons behind these negative assessments commonly relate to weak synergies in terms of 1) differences in political culture and governance structures, 2) the lack of long-term commitment in developing cooperation, 3) contrasting interest of national and local policymakers, and 4) the lack of regional administrative and political bodies needed for steering integration. Firstly, many studies reported a general lack of policy interest towards integration (Medeiros Citation2017), while differences in political culture and governance structures were deemed to hinder the capacity of local authorities to cooperate across borders and to design joint policies (Pikner Citation2008; Domínguez, Noronha Vaz, and Vaz Citation2015). Secondly, a general lack of long-term vision concerning integration appears to exist (Lepik and Krigul Citation2015; Medeiros Citation2017), which is partly considered to be a result of the project-based funding that this type of cooperation is commonly built upon. Thirdly, national governments have been deemed as slow in agreeing on, e.g. funding programs while acting rapidly when needs and opportunities arise is in the interests of local policymakers (Sarmiento-Mirwaldt and Roman-Kamphaus Citation2013). Finally, the local authorities of many countries do not have a direct say concerning funding cooperation, as decisions are made on the national level, which limits their ability to direct integration processes (Carter and Ortolano Citation2000; van den Broek and Smulders Citation2015). Thus, integration is commonly dependent on external authorities (Perkmann Citation2007). In cases where policy structures were discussed as drivers of integration, they related most often to the harmonizing role of international agreements, such as the now-defunct NAFTA and the Single European Market (Hassink, Dankbaar, and Corvers Citation1995; Bagchi-Sen and MacPherson Citation1999), or to the benefits of funding initiatives such as INTERREG (Perkmann Citation2007; Perkmann and Spicer Citation2007).

4.2.6. Accessibility

In 13 out of 21 reported cases, good accessibility across the border enhanced integration. Good accessibility of a region was a major driver in three cases located in densely populated areas (Bagchi-Sen and MacPherson Citation1999; Perkmann and Spicer Citation2007; Fiedor et al. Citation2017). In the remaining ten cases, it was a minor driver maintained by accessible and regular transportation connections along with high-quality infrastructure. Low accessibility, identified as a constraint, was reported in six cases (three times as a minor and three times as a major constraint), e.g. due to bad connections (Domínguez, Noronha Vaz, and Vaz Citation2015) or poor infrastructure (Kurowska-Pysz, Castanho, and Loures Citation2018).

4.2.7. Sustainability and resilience

Finally, we pinpoint issues regarding cross-cutting sustainability that would thereby indicate desirable or undesirable resilience in terms of CBRIS integration, using the SDG framework as guidance for assessing sustainable integration. Although very few cases explicitly mentioned or considered such issues, we extracted relevant concerns regarding socio-economic and ecological systems in 15 and eight cases, respectively. Several of these articles observed concerns related to the lack of any meaningful inclusiveness in decision-making regarding regional development, whereas economic inequality and job opportunities on different sides of the border (SDG8 and SDG 10Footnote3), a constant lack of funding, and a sudden drop in funding or project termination are the clearest examples of issues undermining sustainability mentioned in at least a few of our sample cases (Galko, Volodin, and Nakonechna Citation2015; Lepik and Krigul Citation2015; Medeiros Citation2017). This heavy dependence on (external) funding is particularly problematic for managing desirable resilience: a CBRIS that bases its activities on external funding possesses continuously low levels of resilience that never really allow for managing for resilience. The literature discusses that firms need to devote themselves to building more flexible, self-organizing linkages with various actors to enhance integration, adaptability and resilience (Lee Citation2009; Lavrinenko et al. Citation2016). However, further elaboration on the consequences of such development is missing. In the future, studies could be expanded to assess the impacts of network development particularly with SDG9, SDG11, and SDG12.Footnote4

One study mentioned that municipalities within a cross-border region with higher development levels are usually environmentally less sustainable (Domínguez, Noronha Vaz, and Vaz Citation2015), highlighting the common trade-offs of developing businesses in weak institutional environments. More specifically, the study discussed how the tourism industry supports socio-economic development and is not necessarily designed to comply with the ecological requirements and may contribute to, for example, biodiversity loss (Domínguez, Noronha Vaz, and Vaz Citation2015, SDG9, and SDG10).

Consideration of economic equality in a cross-border region is important from the resilience viewpoint because inequality may spark unwanted social feedbacks over space and time. Our results point out some of the mechanisms of how inequality within and among nations in the cross-border regions continues to be a significant concern despite progress in efforts to narrow disparities in opportunity, income, and power at the global level (SDG10). For example, evidence shows that the integration of CBRIS in areas where the standard of living and wages are higher on the other side of the border leads to ’brain-drain’ to the wealthier side (Makkonen and Weidenfeld Citation2016), which raises questions regarding resilience, social inequalities and the availability of decent work (SDG8) on both sides of the border, especially in the long term. Peripheral border regions often fare worse economically than metropolitan areas, and differences may occur depending upon which side of the border a person is located in. People moving away from their homes increase cross-border traffic, which may lead to undesirable local ecological impacts and potential burdening of the climate and nature, especially if public transportation is not available in remote regions (SDG 13, SDG 14, and SDG 15). Again, a system whose actions lead to environmental degradation cannot be considered neither sustainable nor desirably resilient.

Initiatives to protect natural and environmental heritage sites in a cross-border setting were considered a possible practice for promoting environmental sustainability (Medeiros Citation2017, 152). However, the evidence base for CBRIS with regards to resilience, whether desirable or undesirable, and the proposed ‘sustainable integration’ are generally very thin.

5. Conclusion

To answer our first research question: studies on CBRIS and their integration have recently started to gain momentum but the literature is still heavily Eurocentric. Thus, studies focusing on cross-border regions elsewhere are needed to gain an understanding of the (potential) validity and feasibility of the CBRIS integration model of Lundquist and Trippl (Citation2013) in non-European contexts. Our results suggest that cross-border regional development is typically driven by the conventional ‘triple helix’ model of innovation with governmental, business, and research organizations at its core (Clar Citation2018, 8). From the sustainability viewpoint, public participation needs to be better evaluated in cross-border regions, where defining and achieving sustainability goals may depend upon the commitment of citizens and stakeholders (Reed et al. Citation2018).

With regard to drivers and constraints of CBRIS integration (Lundquist and Trippl Citation2013, 455), our second research question, we are able to depict, with a few exceptions, a systematic pattern between CBRIS integration and strong economic synergies, and weak CBRIS integration and economic constraints. Similar reciprocal patterns can be confirmed for the other drivers (or constraints), such as research synergies, knowledge flows, and institutional and policy structures. The results concerning the benefits and role of research synergies and strong policy structures are rather conclusive, but the other dimensions show more variation in their impacts on CBRIS integration. Overall, the reviewed articles had a strong focus on economic synergies and institutional and policy set-ups, whereas other components received less attention. Particularly, the proposed sustainable integration of CBRIS and its relation to desirable resilience needs more attention and needs to be better evaluated to allow for cross-border regions to engage with more sustainable development trajectories.

To answer our third and fourth research questions, based on the reviewed literature it seems that the studied CBRIS are not particularly sustainable (nor well-integrated in the first place) and that their resilience has largely remained a neglected topic (possibly due to the lack of suitable frameworks). The reviewed studies only marginally discuss the incorporation of sustainability goals in the current CBRIS practices – literature on cross-border innovation focuses merely on expediting integration in a linear fashion. However, considering the contemporary ‘border shocks’, the linear model of CBRIS is clearly not functioning, and therefore, resilience thinking must be adopted. Keeping in mind that the future success of border regions may well depend upon their ability to create common innovation spaces and to transform themselves in ever-changing environments and in face of disturbances in CBRIS integration, this apparent lack should be a concern for policymakers considering how to survive the negative impacts of decreased border permeability.

We propose that the concept of R-CBRIS for sustainability allows for determining factors that contribute to the resilience and sustainability of cross-border regions. Linking these two conceptually broad and complex issues together requires further efforts to pinpoint exactly, for example, can cross-border synergies help to build desirable resilience, can knowledge flows tolerate decreased border permeability (affecting physical accessibility), and thus contribute to desirable resilience, and what types of institutional structures and cross-border policies are needed for managing for cross-border regional resilience? By adding the sustainability dimension to the CBRIS integration model of Lundquist and Trippl (Citation2013), further research can depict and analyze development towards sustainable integration of CBRIS. Although our focus in this paper has been on defining R-CBRIS for sustainability, much of the underlying reasoning can be useful also for those studying innovation systems more generally.

Therefore, the main theoretical contribution of our study is to bridge the innovation systems literature (Asheim, Grillitsch, and Trippl Citation2016) through the concepts of (social-ecological) resilience and sustainability (Elmqvist et al. Citation2019; Folke Citation2016; Olsson, Galaz, and Boonstra Citation2014) in the context of CBRIS (Makkonen and Rohde Citation2016), which offers a novel way of rethinking the processes that may lead to greater sustainability in border regions. Our results are also a first attempt at applying the SDG framework to ‘place-specific’ smart specialization in border regions (Xu et al. Citation2020; Clar Citation2018). We suggest that cross-border regions provide an interesting context where the role of innovation in managing for resilience and sustainability can be depicted. However, the empirical part of our study reveals that resilience thinking is in its infancy in CBRIS and particularly the ecological impact of developing CBRIS is not recognized by empirical research (see also Hassink and Gong Citation2019).

Our approach entails some important limitations, which also pave the way for further research. Notably, we were unable to determine which integration stage the analyzed cases represent. Most of the studies are bound to the linear five-year project interval and to the relatively short lifespan of projects, on which most of the empirical evidence in the analyzed studies rely and which does not allow for the evaluation of CBRIS integration over a long period of time. Ironically, the scholarship on CBRIS integration is not particularly resilient either. Our results also reflect the geographical diffusion of interest in studying CBRIS. As a concept developed to a large extent by utilizing the ‘textbook example’ of the Øresund cross-border region, it is perhaps not so surprising that empirical study on the topic has concentrated on north European case studies. Research institutes active in this strand of research, such as the universities in eastern Finland, Oulu, southern Denmark and Nijmegen, are also largely based in northern Europe. Therefore, the results do not imply that CBRIS exist mainly in northern Europe – rather, they have not yet been extensively studied elsewhere. Moreover, the selection of studies was based on internationally peer-reviewed articles, which may leave out important unpublished work, and grey literature, causing a selection bias. We carefully examined each article to determine whether they contain relevant data, but there is a good chance of human error in interpreting what types of cases fall explicitly under the concept of innovation. It was also hard to define whether the ‘innovations’ were successful.

In order to analyze and generalize findings across different CBRIS without undermining their inherent complexity and context-specificity, future research should focus on developing both empirical methods for diagnosing R-CBRIS for sustainability and the proposed framework per se. For example, there is certainly room for exploring the confluences between our framework and the ones by Rinkinen and Harmaakorpi (Citation2018) and Cappellano and Makkonen (Citation2019) concerning the uptake of the business and innovation ‘ecosystem’ concepts in the context of innovation policy more generally.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Helsinki Institute of Sustainability Science (HELSUS) of the University of Helsinki through its seed-funding instrument. Dr. Korhonen thanks ORBIT project (307480) funded by the Academy of Finland.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2020.1867518.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 SDG8 Promote sustained, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all; SDG9 Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation; SDG13 Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts; SDG14 Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development.

2 The search string for Scopus: (‘cross?border’ OR ‘border region*’ OR ‘trans?boundar*’ OR borderland* OR ‘inter?region*’ OR ‘trans?frontier’ OR ‘border area*’) AND (innovat* OR ‘knowledge transfer*’ OR ‘technology transfer*’ OR ‘technology diffusion’ OR ‘market diffusion’ OR ‘new technolog*’ OR ‘new product*’ OR ‘new market*’ OR ‘new service*’ OR ‘new process*’ OR ‘novel technolog*’ OR ‘novel product*’ OR ‘novel market*’ OR ‘novel service*’ OR ‘novel process*’)

3 SDG 10 Reduce inequality within and among countries

4 SDG 11 Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable; SDG12 Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns; SDG 15 Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss

References

- Archer, D., E. Kite, and G. Lusk. 2020. “The Ultimate Cost of Carbon.” Climatic Change 162: 2069–2086.

- Asheim, B. 2018. “Smart Specialisation, Innovation Policy and Regional Innovation Systems: What About new Path Development in Less Innovative Regions?” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 32: 8–25. doi:10.1080/13511610.2018.1491001.

- Asheim, B., M. Grillitsch, and M. Trippl. 2016. “Regional Innovation Systems: Past-Present-Future.” In Handbook on the Geographies of Innovations, edited by R. Shearmur, C. Carrincazeaux, and D. Doloreux, 45–62. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Asheim, B., A. Isaksen, and M. Trippl. 2019. Advanced Introduction to Regional Innovation Systems. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Bagchi-Sen, S., and A. MacPherson. 1999. “Competitive Characteristics of Small and Medium-Sized Manufacturing Firms in the U.” S. and Canada. Growth and Change 30: 315–336.

- Beck, U. 2010. “Climate for Change, or how to Create a Green Modernity?” Theory, Culture and Society 27 (2–3): 254–266.

- Berrová, E., M. Jeřábek, and G. K. Jüttler. 2016. “Research and Practice: Partners and/or Competitors?” GeoScape 9: 33–46.

- Blatter, J. 2000. “Emerging Cross-Border Regions as a Step Towards Sustainable Development? Experiences and Considerations from Examples in Europe and North America.” International Journal of Economic Development 2: 402–440.

- Blatter, J. 2004. “From ‘Spaces of Place’ to ‘Spaces of Flows’?” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28: 530–548.

- Boonstra, W. J. 2016. “Conceptualizing Power to Study Social-Ecological Interactions.” Ecology and Society 21: 21.

- Boschma, R. 2015. “Towards an Evolutionary Perspective on Regional Resilience.” Regional Studies 49: 433–751.

- Bousquet, F., A. Botta, L. Alinovi, O. Barreteau, D. Bossio, K. Brown, P. Caron, et al. 2016. “Resilience and Development: Mobilizing for Transformation.” Ecology and Society 21: 40.

- Brennan, R. L., and D. J. Prediger. 1981. “Coefficient Kappa: Some Uses, Misuses, and Alternatives.” Educational and Psychological Measurement 41: 687–699.

- Cappellano, F., and T. Makkonen. 2019. “Cross-border Regional Innovation Ecosystems: The Role of non-Profit Organizations in Cross-Border Cooperation at the US-Mexico Border.” GeoJournal 85: 1515–1528.

- Carpenter, S., B. Walker, J. M. Anderies, and N. Abel. 2001. “From Metaphor to Measurement: Resilience of What to What?” Ecosystems 4: 765–781.

- Carter, N., and L. Ortolano. 2000. “Working Toward Sustainable Water and Wastewater Infrastructure in the US-Mexico Border Region.” International Journal of Water Resources Development 16: 691–708.

- Centeno, M. A., M. Nag, T. S. Patterson, A. Shaver, and A. J. Windawi. 2015. “The Emergence of Global Systemic Risk.” Annual Review of Sociology 41: 65–85.

- Clar, G. 2018. Guiding Investments in Place-Based Development. Priority Setting in Regional Innovation Strategies. JRC112689. Seville: European Commission, p. 39.

- Coenen, L., J. Moodysson, and B. Asheim. 2004. “Nodes, Networks and Proximities: on the Knowledge Dynamics of the Medicon Valley Biotech Cluster.” European Planning Studies 12: 1003–1018.

- Common, M., and C. Perrings. 1992. “Towards an Ecological Economics of Sustainability.” Ecological Economics 6: 7–34.

- Cooke, P. 1992. “Regional Innovation Systems: Competitive Regulation in the new Europe.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 23: 365–382.

- de Souza, M., F. T. Veloso, L. B. dos Santos, and R. B. da Silva Caeiro. 2014. “Governance of Common Pool Resources.” Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional 57: 152–175.

- Dissart, J. C. 2003. “Regional Economic Diversity and Regional Economic Stability.” International Regional Science Review 26: 423–446.

- Domínguez, J. A., T. Noronha Vaz, and E. Vaz. 2015. “Sustainability in the Trans-Border Regions?” International Journal of Global Environmental Issues 14: 151–163.

- Durand, F., and T. Perrin. 2018. “Eurometropolis Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai: Cross-Border Integration with or Without the Border?” European Urban and Regional Studies 25: 320–336.

- Elmqvist, T., E. Andersson, N. Frantzeskaki, T. McPhearson, P. Olsson, O. Gaffney, K. Takeuchi, and C. Folke. 2019. “Sustainability and Resilience for Transformation in the Urban Century.” Nature Sustainability 2: 267–273.

- European Commission. 2014. National/Regional Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisation. Brussels: European Commission.

- Fiedor, D., Z. Szczyrba, M. Šerý, I. Smolová, and V. Toušek. 2017. “The Spatial Distribution of Gambling and its Economic Benefits to Municipalities in the Czech Republic.” Moravian Geographical Reports 25: 104–117.

- Folke, C. 2016. “Resilience (Republished).” Ecology and Society 21: 44.

- Folke, C., Å Jansson, J. Rockström, P. Olsson, S. R. Carpenter, F. S. Chapin, III, A.-S. Crepín, et al. 2011. “Reconnecting to the Biosphere.” Ambio 40: 719–738.

- Francis, J., A. Mukherji, and J. Mukherji. 2009. “Examining Relational and Resource Influences on the Performance of Border Region SMEs.” International Business Review 18: 331–343.

- Galko, S., D. Volodin, and A. Nakonechna. 2015. “Economic Competitiveness Increase Through Development of SMEs in Cross-Border Regions of Poland.” Belarus and Ukraine. Economic Annals 21: 23–27.

- Gault, F. 2018. “Defining and Measuring Innovation in all Sectors of the Economy.” Research Policy 47: 617–622.

- Gell-Mann, M. 2010. “Transformations of the Twenty-First Century: Transitions to Greater Sustainability.” In Global Sustainability: a Nobel Cause. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, edited by J. Schellnhuber, M. Molina, N. Stern, V. Huber, and S. Kadner, 1–8. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gifford, R. 2011. “The Dragons of Inaction: Psychological Barriers That Limit Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation.” American Psychologist 66 (4): 290–302.

- Hahn, C. K. 2013. “The Transboundary Automotive Region of Saar-Lor-Lux: Political Fantasy or Economic Reality?” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 48: 102–113.

- Halonen, M. 2019. “The Long-Term Adaptation of a Resource Periphery as Narrated by Local Policy-Makers in Lieksa.” Fennia 197: 40–57.

- Hansen, N. 1983. “International Cooperation in Border Regions.” International Regional Science Review 8: 255–270.

- Hansen, T. 2013. “Bridging Regional Innovation: Cross-Border Collaboration in the Øresund Region.” Geografisk Tidsskrift 113: 25–38.

- Hassink, R. 2010. “Regional Resilience: a Promising Concept to Explain Differences in Regional Economic Adaptability?” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 3: 45–58.

- Hassink, R., B. Dankbaar, and F. Corvers. 1995. “Technology Networking in Border Regions.” European Planning Studies 3: 63–83.

- Hassink, R., and H. Gong. 2019. “Six Critical Questions About Smart Specialization.” European Planning Studies, 2049–2065. doi:10.1080/09654313.2019.1650898.

- Heenan, D. 2009. “Working Across Borders to Promote Positive Mental Health and Well-Being.” Disability and Society 24: 715–726.

- Henry, A. D. 2018. “Learning Sustainability Innovations.” Nature Sustainability 1: 164–165.

- Hickel, J. 2019. “The Contradiction of the Sustainable Development Goals: Growth Versus Ecology on a Finite Planet.” Sustainable Development 25 (5): 873–884.

- Hickel, J. 2020. “The Sustainable Development Index: Measuring the Ecological Efficiency of Human Development in the Anthropocene.” Ecological Economics 167: 106331.

- Holling, C. 1973. “Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems.” Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 4: 1–23.

- Jakola, F., and E. K. Prokkola. 2018. “Trust Building or Vested Interest?” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 109: 224–238.

- Judkins, G. L., and K. Larson. 2010. “The Yuma Desalting Plant and Cienega de Santa Clara Dispute.” Water Policy 12: 401–415.

- Kaika, M. 2017. ““Don’t Call me Resilient Again!”: The New Urban Agenda as Immunology … or … What Happens When Communities Refuse to be Vaccinated with “Smart Cities” and Indicators.” Environment and Urbanization 29: 89–102.

- Keys, P. W., V. Galaz, M. Dyer, N. Matthews, C. Folke, M. Nyström, and S. E. Cornell. 2019. “Anthropocene Risk.” Nature Sustainability 2: 667–673.

- Knippschild, R., and T. Wiechmann. 2012. “Supraregional Partnerships in Large Cross-Border Areas.” Planning Practice and Research 27: 297–314.

- Kranjac, M., V. Dickov, and U. Sikimic. 2013. “Cross-border Innovation Process Within the EU Economy.” Actual Problems of Economics 1: 386–396.

- Kratseva, A. 2020. “If Borders Did Not Exist, Euroscepticism Would Have Invented Them Or, on Post-Communist Re/De/Re/Bordering in Bulgaria.” Geopolitics 25 (3): 678–705.

- Krigul, M. 2011. “On Possibilities to Develop Cross-Border Knowledge Region.” Problems and Perspectives in Management 9: 1–31.

- Kurowska-Pysz, J., R. A. Castanho, and L. Loures. 2018. “Sustainable Planning of Cross-Border Cooperation.” Sustainability 10: 1416.

- Lavrinenko, O., N. Jefimovs, and J. Teivāns-Treinovskis. 2018. “Issues in the Area of Secure Development: Trust as an Innovative System’s Economic Growth Factor of Border Regions.” Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues 6: 435–444.

- Lavrinenko, O., A. Ohotina, V. Tumalavicius, and O. V. Pidlisna. 2016. “Assessment of Partnership Development in Cross-Border Regions’ Innovation Systems.” Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues 6: 155–166.

- Lee, C. K. 2009. “How Does a Cluster Relocate Across the Border?” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 73: 371–381.

- Lepik, K. L., and M. Krigul. 2009. “Cross-border Cooperation Institution in Building a Knowledge Cross-Border Region.” Problems and Perspectives in Management 7: 33–45.

- Lepik, K. L., and M. Krigul. 2015. “Challenges in Knowledge Sharing for Innovation in Cross-Border Context.” International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development 5: 332–343.

- Lundquist, K. J., and M. Trippl. 2013. “Distance, Proximity and Types of Cross-Border Innovation Systems.” Regional Studies 47: 450–460.

- Lyytimäki, J., K.-M. Lonkila, E. Furman, K.-K. Korhonen, and S. Lähteenoja. 2020. “Untangling the Interactions of Sustainability Targets: Synergies and Trade-Offs in the Northern European Context.” Environment, Development and Sustainability. doi:10.1007/s10668-020-00726-w.

- Makkonen, T., and S. Rohde. 2016. “Cross-border Regional Innovation Systems: Conceptual Backgrounds, Empirical Evidence and Policy Implications.” European Planning Studies 24: 1623–1642.

- Makkonen, T., and A. Weidenfeld. 2016. “Knowledge-based Urban Development of Cross-Border Twin Cities.” International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development 7: 389–406.

- Makkonen, T., A. M. Williams, A. Weidenfeld, and V. Kaisto. 2018. “Cross-border Knowledge Transfer and Innovation in the European Neighbourhood.” Tourism Management 68: 140–151.

- Malkamäki, A., P. Wagner, M. Brockhaus, A. Toppinen, and T. Ylä-Anttila. 2019. “On the Acoustics of Policy Learning: Can Co-Participation in Policy Forums Break Up Echo Chambers?” Policy Studies Journal. doi:10.1111/psj.12378.

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2015. “On the Notion of Regional Economic Resilience.” Journal of Economic Geography 15: 1–42.

- Mayer, A., P. E. Kauppi, P. Anglestam, Y. Zhang, and P. Tikka. 2005. “Importing Timber, Exporting Ecological Impact.” Science 308: 359–360.

- Medeiros, E. 2014. “Territorial Cohesion Trends in Inner Scandinavia.” Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift 68: 310–317.

- Medeiros, E. 2017. “Cross-border Cooperation in Inner Scandinavia.” Environmental Impact Assessment Review 62: 147–157.

- Miörner, J., E. Zukauskaite, M. Trippl, and J. Moodysson. 2018. “Creating Institutional Preconditions for Knowledge Flows in Cross-Border Regions.” Environment and Planning C 36: 201–218.

- OECD. 2015. In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Olsson, P., V. Galaz, and W. J. Boonstra. 2014. “Sustainability Transformations: a Resilience Perspective.” Ecology and Society 19: 1.

- O’Neill, D. W., A. L. Fanning, W. F. Lamb, and J. K. Steinberger. 2018. “A Good Life for All within Planetary Boundaries.” Nature Sustainability 1: 88–95.

- Peberdy, S., and J. Crush. 2001. “Invisible Trade, Invisible Travelers.” South African Geographical Journal 83: 115–123.

- Perkmann, M. 2007. “Policy Entrepreneurship and Multilevel Governance.” Environment and Planning C 25: 861–879.

- Perkmann, M., and A. Spicer. 2007. “Healing the Scars of History: Projects, Skills and Field Strategies in Institutional Entrepreneurship.” Organization Studies 28: 1101–1122.

- Pikner, T. 2008. “Reorganizing Cross-Border Governance Capacity.” European Urban and Regional Studies 15: 211–227.

- Pohoryles, R. J. 2007. “Sustainable Development, Innovation and Democracy: What Role for the Regions?” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 20 (3): 183–190.

- Prokkola, E. K. 2019. “Border-regional Resilience in EU Internal and External Border Areas in Finland.” European Planning Studies 27: 1587–1606.

- Pullin, A. S., and G. B. Stewart. 2006. “Guidelines for Systematic Review in Conservation and Environmental Management.” Conservation Biology 20: 1647–1656.

- Randolph, J. J. 2008. Online kappa calculator. http://justusrandolph.net/kappa/.

- Raworth, K. 2013. “Defining a Safe and Just Space for Humanity.” In Worldwatch Institute, State of the World 2013, 28–38. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Reed, M. S., S. Vella, E. Challies, J. de Vente, L. Frewer, D. Hohenwallner-Ries, T. Huber, et al. 2018. “ A Theory of Participation: What Makes Stakeholder and Public Engagement in Environmental Management Work?” Restoration Ecology 26: S7–S17.

- Rinkinen, S., and V. Harmaakorpi. 2018. “The Business Ecosystem Concept in Innovation Policy Context: Building a Conceptual Framework.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 31 (3): 333–349.

- Sarmiento-Mirwaldt, K., and U. Roman-Kamphaus. 2013. “Cross-border Cooperation in Central Europe.” Europe-Asia Studies 65: 1621–1641.

- Schulze, A. D., M. J. C. Stade, and J. Netzel. 2014. “Conflict and Conflict Management in Innovation Processes in the Life Sciences.” Creativity and Innovation Management 23: 57–75.

- Schumpeter, J. A. 1911. Theorie der Wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung. Leipzig: Duncker und Humblot.

- Seyfang, G., and A. Haxeltine. 2012. “Growing Grassroots Innovations: Exploring the Role of Community-Based Initiatives in Governing Sustainable Energy Transitions.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 30: 381–400.

- Song, X.-P. 2018. “Global Estimates of Ecosystem Service Value and Change: Taking Into Account Uncertainties in Satellite-Based Land Cover Data.” Ecological Economics 143: 227–235.

- Steffen, W., J. Rockström, K. Richardson, T. M. Lenton, C. Folke, D. Liverman, and C. P. Summerhayes. 2018. “Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115: 8252–8259.

- Taylor, M. Z. 2016. “Great Definitions (Non)Debate.” In The Politics of Innovation, edited by M. Z. Taylor, 301–309. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Trippl, M. 2010. “Developing Cross-Border Regional Innovation Systems.” Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 101: 150–160.

- United Nations. 2015. United Nations General Assembly Resolution A/Res/70/1: Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. In Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015.

- van den Broek, J., and H. Smulders. 2015. “ Institutional Hindrances in Cross-Border Regional Innovation Systems.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 2: 116–122.

- Walker, B., C. S. Holling, S. R. Carpenter, and A. Kinzig. 2004. “Resilience, Adaptability and Transformability in Social-Ecological Systems.” Ecology and Society 9: 5.

- Walsh, D., and S. Downe. 2005. “Meta-synthesis Method for Qualitative Research.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 50: 204–211.

- Wilson G, A. 2014. “Community Resilience: Path Dependency, Lock-in Effects and Transitional Ruptures.” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 57 (1): 1–26.

- Xu, Z., S. N. Chau, X. Chen, L. Zhang, Y. Li, T. Dietz, et al. 2020. “Assessing Progress Towards Sustainable Development Over Space and Time.” Nature 577: 74–78.

- Zeng, Y., S. Maxwell, R. K. Runting, O. Venter, J. E. M. Watson, and L. R. Carrasco. 2020. “Environmental Destruction not Avoided with the Sustainable Development Goals.” Nature Sustainability 3: 795–798.

- Zmelik, K., S. Schindler, and T. Wrbka. 2011. “The European Green Belt: International Collaboration in Biodiversity Research and Nature Conservation Along the Former Iron Curtain.” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 24: 273–294.