Abstract

This article studies citizens’ support for deliberative democracy in Belgium. It examines it, first, from the perspective of Belgian citizens in general. In a second step, it looks specifically at the attitudes of citizens from four disadvantaged groups (women, lower educated citizens, citizens with precarious job conditions and younger citizens). Regarding these groups we want to see whether they show different levels of support for deliberative democracy than the rest of the population and if their attitudes are driven by the same factors as for citizens from more advantaged groups. Regarding the general population, the main finding is that support for deliberative democracy is driven by negative attitudes towards elected politicians but mainly by positive attitudes regarding the political competence of fellow citizens. Regarding disadvantaged groups, we see first that women and younger citizens show higher levels of support than the rest of the population. Second, when it comes to the factors driving support for deliberative democracy within these disadvantaged groups, it appears that they are similar to the rest of the population except when it comes to political interest. Being more interested in politics is a determinant to be in favour of deliberative democracy for citizens from disadvantaged groups.

Introduction

As emphasized by several decades of studies, advanced industrial democracies are confronted with an erosion of political support (Dalton Citation2004). Citizens tend to be more distant from political parties, more critical toward institutions and less positive regarding governments (Dalton Citation2004). Two competitive hypotheses are proposed: the socialization and resocialization experience of people and the performance evaluation. The resocialisation theory refers to a change within individuals toward post-materialist values (Inglehart Citation1990, Citation1997). Citizens holding such values would no longer be satisfied with a representative system that would just leave them with the opportunity to vote in elections every four years or so. It refers to what Norris (Citation2011) calls the rise of critical citizens. The other line of explanation – the performance evaluation hypothesis – claims that political dissatisfaction stems from a negative evaluation of the policy performance of government. Especially in Western democracies, periods of sustained growth are becoming rare, and public debts have been on the rise, leading to the adoption of austerity policies and to growing pressures on public services as well as on the welfare system (Thomassen Citation2015).

Building on this idea of a growing political resentment in many democracies, scholars have examined whether and how such discontent might translate into demands for reforms of representative democracy. Literature on the topic has grown significantly over the last decade (Landwehr and Faas Citation2016; Caluwaerts et al. Citation2018; Bedock and Pilet Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Gherghina and Geissel Citation2020). It appeared that citizens might be divided between those calling for a system that would remain essentially representative and dominated by elected politicians, those demanding a greater role for citizens in policy-making, and those pushing for a more technocratic model of government (see Gherghina and Geissel Citation2017). The three logic have been summarized by Bengtsson and Christensen (Citation2016) under three competitive conceptions of democracy: the Representation/Elitist, Expertise/technocratic and Participation/Pluralist conceptions of democracy.

Yet, a limitation in existing research is that they have been looking at support in the broader public, but without examining specifically and in detail differences that may be present among some specific groups in society. In particular, they have not looked at the specific cases of citizens belonging to groups that are politically disadvantaged and less represented in elected institutions such as women, younger citizens, lower educated citizens or citizens with more precarious jobs. The specific contribution of this article, and of the special issue more broadly, is precisely to fill in this gap. We will look at the case of women, younger citizens, citizens with a lower level of education and citizens in a more precarious professional situation.

We believe that such an addition to current studies is crucial as there are several reasons to believe that citizens from groups that are politically disadvantaged would hold different attitudes towards deliberative democracy. As elaborated above, recent research on support for deliberative democracy has mobilized two arguments. The first is the re-socialization argument according to which support for deliberation is driven by the growing competence of citizens, and the demand associated for more and richer political participation. Yet, this line of explanation would be less likely to hold for some of the disadvantaged groups we study, namely lower educated citizens and citizens with precarious professional situations. Such groups are not the ones which have experienced an increase in their political competence or in their educational capital. Therefore, according to the re-socialization hypothesis, we might see lower support for deliberative democracy in these two groups. They tend to have lower resources (in terms of education and/or income) and often to participate less. As a consequence, they might not be willing for more participation and would support less deliberative democracy. The other main argument is the performance hypothesis, which claims that support for deliberative democracy, and for institutional change more broadly, is stronger among citizens who do not benefit from the current institutional architecture (see Ceka and Magalhaes Citation2020). This argument is especially strong when it comes to supporting direct democracy (see Bowler, Donovan, and Karp Citation2007) as referendums give a direct say in policy-making to all citizens. With deliberative democracy, the effect might be less straightforward as it would give a direct say to a limited number of citizens, and some citizens from disadvantaged groups might fear that they would again come from a restricted elite (Pow, van Dijk, and Marien Citation2020). Yet, overall, deliberative democracy remains a reform going in the direction of opening up the policy process to each and every citizen. Therefore, we would still expect stronger support for deliberative democracy among disadvantaged groups. They are less well represented in representative institutions and they might develop stronger forms of resentment towards elected politicians. We hope to shed more light on these debates with the present article.

More precisely, we propose to examine in detail which citizens would call for a greater and more direct intervention of citizens in policy-making by supporting democratic innovations inspired by the logic of deliberative democracy. Deliberative democracy refers to “any one of a family of views according to which the public deliberation of free and equal citizens is the core of legitimate political decision making and self-government” (Bohman Citation1998, 401). Such instruments have gained ground in many established democracies (Smith Citation2009; Geißel and Joas Citation2013). For instance, Paulis et al. (Citation2020) identify at least 127 deliberative mini-publics implemented in Europe by public authorities and scholarship regarding deliberative democracy increased during the last decades. Belgium, the case covered in this study, is one of the countries in which such mini-publics have been often used by public authorities.

The paper is divided in two parts. In the first, we examine the determinants of support for deliberative democracy in the broader public. We test hypotheses derived by recent studies on the topic, or on support for other democratic innovations enhancing citizens’ participation, and we test them in the Belgian context (Schuck and de Vreese Citation2015; Bowler, Donovan, and Karp Citation2007; Bedock and Pilet Citation2020b, Citation2020a; Gherghina and Geissel Citation2020). These are (1) political dissatisfaction, (2) political interest (as an indicator of political engagement), and (3) trust in the political skills of fellow citizens.

Then, in the second part of the analysis, we look more specifically at the attitudes towards deliberative processes of citizens from groups that tend to be less represented in political institutions (women, young people, lower educated citizens and citizens with precarious job conditions). We first examine whether their belonging to one of these groups generates different levels of support for deliberative democracy. We then look at the factors shaping attitudes towards deliberative democracy to see whether they are the same within such disadvantaged groups and within more advantaged groups.

Theoretical framework: who supports instruments of deliberative democracy?

Various studies have over recent years tried to understand which citizens were more supportive of a greater role of citizens in policy-making (Webb Citation2013; Río, Navarro, and Font Citation2016; Gherghina and Geissel Citation2017). Among them, a few have then tried to examine specifically support for instruments of deliberative democracy (Font, Wojcieszak, and Navarro Citation2015; Bedock and Pilet Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Gherghina and Geissel Citation2020).

The main approach to support for deliberative democracy or other forms of democratic innovations is that it would find ground among the most politically dissatisfied citizens. Citizens who are unhappy with the way politics is working in their country would look for alternative models of governance, and would therefore be more open to reforms that would increase the role of citizens in policy-making. This line of explanation was first developed in studies on public support for a greater use of referendums (Schuck and de Vreese Citation2015). Bowler, Donovan, and Karp (Citation2007) present it as the “enraged citizens” hypothesis. More recently, the same hypothesis has been tested regarding support for participatory models of governance (Bengtsson and Mattila Citation2009; Río, Navarro, and Font Citation2016; Caluwaerts et al. Citation2018), as well as in accounting for support for specific democratic innovations like mini-publics (Bedock and Pilet Citation2020a, Citation2020b).

An interesting development within this approach has been made by Gherghina and Geissel (Citation2019). Before them, most studies were using quite generic and broad measures of political (dis)satisfaction. They used indicators such as “satisfaction with democracy” or trust towards the main actors and institutions of representative democracy. Gherghina and Geissel (Citation2019) have proposed going back to Easton’s (Citation1965) classical distinction between diffuse and specific support, and distinguishing between diffuse support for the principles of the political system and support for specific actors. They found that dissatisfaction with institutions and the political system are more affecting support for citizens as decision makers in Germany. Gherghina and Geissel (Citation2020) also find a positive relationship between doubt in institutions and government and support for deliberative democracy as well as for political interest. Other authors rather distinguish between different objects of political support such as the political regime, political institutions and political actors (see Norris Citation2011). Bedock and Pilet (Citation2020b) found, for instance, that support for mini-publics among French citizens was strong when political support was low for political actors, but was even stronger when support was lower for institutions and the regime. We propose to follow this logic for our first three hypotheses.

H1: Support for instruments of deliberative democracy will be stronger among citizens with lower satisfaction with democracy in general (regime support).

H2: Support for instruments of deliberative democracy will be stronger among citizens with lower trust in representative institutions (support for political institutions).

H3: Support for instruments of deliberative democracy will be stronger among citizens holding more negative evaluations of politicians (support for political actors).

A second set of political attitudes relates to how citizens perceive themselves, how competent and interested they consider to be for politics. The general argument is that some citizens have acquired stronger political skills, and feel, as a consequence, more able to have a useful say into policymaking. Those citizens also tend to show greater interest for public affairs. These elements connect to traditional explanations of political participation: citizens with more resources and more (perceived) ability to participate support more opportunities to have a say in politics (Almond and Verba Citation1963; Brady, Verba, and Scholzman Citation1995). In their study about referendums, Schuck and de Vreese (Citation2015) refer to it as the “engaged citizens” hypothesis and several studies have confirmed that it was also playing a role in shaping opinions towards deliberative democracy (Jacobs, Cook, and Delli Carpini Citation2009; Bedock and Pilet Citation2020b; Gherghina and Geissel Citation2020). It leads us to the following hypothesis.

H4: Support for instruments of deliberative democracy will be stronger among citizens with higher levels of political interest.

Finally, in their study of French citizens’ attitudes towards sortition, Bedock and Pilet (Citation2020a) underlined the role of a third set of attitudes: how citizens evaluate the political competence of their fellow citizens. The same kinds of attitudes had been earlier underlined in Spain by Adrian Río, Navarro, and Font (Citation2016). The same line of reflection has been central in the qualitative work of García-Espín and Ganuza (Citation2017) on “participatory sceptics”. Using focus groups, they clearly demonstrated that a good share of citizens might be opposed towards deliberative democracy because they doubt that most citizens would have the competence to take part. Deliberative forms of democratic innovation are indeed demanding participatory instruments. They invite participants to engage into long and complex deliberations. How one evaluates the competence of fellow citizens might be even more salient for deliberative forums. In elections and in referendums, everybody is entitled to participate. You do not delegate your sovereignty fully to others. By contrast, in deliberative forums, only a handful of citizens are invited to take part (sometimes via sortition mechanisms). In the vast majority of cases, it means that you would yourself not participate and would have to delegate your sovereignty completely to other citizens. Trusting in their political competence becomes, therefore, more important. In a recent study, Pilet et al. (Citation2020b) have confirmed that a good share of Belgian citizens were quite sceptical regarding the competence, honesty and empathy of their fellow citizens, and such negative evaluations often led them to be more negative towards the introduction of deliberative forms of democracy. It leads to the following hypothesis.

H5: Support for instruments of deliberative democracy will be stronger among citizens who evaluate positively the political skills of their fellow citizens.

The first goal of the paper is to examine whether these hypotheses derived from extant literature do hold in the case of Belgium (see below for case selection). Yet, in line with the rest of this special issue (Gherghina, Mokre, and Miscoiu Citation2020), we want to decompose further public attitudes towards deliberative democracy by looking more specifically at the case of citizens from disadvantaged groups. We pursue two goals here. First, we want to see whether belonging to a disadvantaged group exerts a specific impact in being in favour (or against) deliberative democracy and, second, we want to compare the effects of the highlighted explanatory variables between advantaged and disadvantaged groups. These disadvantaged groups may be defined on the basis of age, level of education, professional situation, or gender.Footnote1

Our expectation is that, overall, citizens from disadvantaged groups will be more supportive of deliberative democracy. The main arguments developed were that non-disadvantaged citizens are more reluctant to move away from the institutional status quo. First, they hold more resources to participate to politics (see Brady, Verba, and Scholzman Citation1995). They are quite well able to find their way with current representative institutions. Therefore, they are more prone to defend the institutional status quo (Ceka and Magalhaes Citation2020). By contrast, citizens from disadvantaged would be keen to move away from the representative logic in which they are less represented among elected politicians, and that does not guarantee a good representation of their interest (Traber et al. Citation2021). It leads to the following hypothesis.

H6: Support for deliberative democracy will be stronger among citizens from disadvantaged groups.

But we want to move beyond this first observation by looking at the dynamics behind support (or opposition) to deliberative democracy. We want to see whether the same factors would apply to account for attitudes towards deliberative democracy within these groups. The question has not been often posed in earlier research. Our hypotheses are therefore more inductive here, even if we may anchor them in some earlier work.

First, we can expect that political dissatisfaction would exert an even stronger effect for citizens from disadvantaged groups. As said above, these groups are less represented in representative institutions (Bartels Citation2008; Lefkofridi, Giger, and Kissau Citation2012; Carnes Citation2016; Rosset Citation2016), and they would also feel that their interests might not be heard by elected politicians. Negative attitudes towards elected politicians would therefore be stronger but also more salient, which should lead to greater demands for giving a more direct say to citizens in policy-making. We, therefore, propose to test the following hypothesis.

H7: The positive impact of factors related to political dissatisfaction on support for deliberative democracy will be stronger for citizens from disadvantaged groups.

The next hypothesis related to the role of political interest. Overall, political interest is less pronounced among citizens from disadvantaged groups (Bennett and Bennett Citation1989; Brady, Verba, and Scholzman Citation1995) and, as said above, low political interest should lead to reduced support for deliberative democracy. However, within disadvantaged groups, there are also citizens with high political interest and we might expect that they would therefore be even more willing to engage into new opportunities for political participation. They understand the limits of representative mechanisms for citizens from disadvantaged groups. We would therefore expect that within disadvantaged groups, the effect of political interest on support for deliberative democracy would be even greater.

H8. The positive impact of factors related to political interest on support for deliberative democracy will be stronger for citizens from disadvantaged groups.

Finally, regarding the impact of how citizens from disadvantaged groups evaluate their fellow citizens, it is harder to formulate clear expectations. What could be argued is that citizens from disadvantaged groups tend to have more negative views on their own political skills. Indeed, internal political efficacy tends to be lower among lower educated, more professionally precarious citizens and women (Campbell et al. Citation1960; Hayes and Bean Citation1993; Schlozman, Verba, and Burns Citation2001; Marx and Nguyen Citation2016). Consequently, we might expect that they would also perceive that their fellow citizens would be more competent politically.

Therefore, the positive impact of their perception of the competence of other citizens on support for deliberative democracy could be a bit stronger. Yet, since no earlier work as elaborated on that, we should be more careful with this last hypothesis.

H9. The positive impact of factors related to the evaluation of fellow citizens will be stronger for citizens from disadvantaged groups.

Data and operationalization

Belgium as a peculiar case regarding the implementation of deliberative practices

The Belgian context is, we believe, very relevant but also quite peculiar to study public attitudes towards deliberative democracy. The Belgian case is very relevant because it is a case where citizens’ familiarity with such form of democratic innovations could be expected to be higher than in many other countries. The topic of the support for tools of deliberative democracy is very salient in the Belgian context. Indeed, lots of citizens’ panels have been organized during the last two decades, Vrydagh et al. (Citation2020) find 38 occurrences of mini-publics including random selection between 2001 and 2018 with 15 of them between 2016 and 2018. Further, four regional assemblies have organized deliberative mini-publics composed of citizens selected by lot over the last five years: the Walloon parliament, the Brussels parliament, the parliament of the French-speaking community, and the parliament of the German-speaking community. The Belgian case goes even further by reaching a crucial stage: the institutionalization of mini-publics (Vrydagh et al. CitationForthcoming) with the Ostbelgien Model (Niessen and Reuchamps Citation2019), but also mixed-deliberative commission in Brussels (Vrydagh et al. Citation2021) and Wallonia.Footnote2 Those recent developments regarding the implementation of deliberative processes make Belgium a very relevant case and might help to have a better grasp of the determinants of support for deliberative democracy.

Yet, the Belgian context might also be quite peculiar when it comes to the political participation of citizens in general, and of citizens of underrepresented groups in particular. Belgium’s representative democracy is one of the most inclusive in contemporary democracies. First, Belgium is a proportional system, which as emphasized by Lijphart (Citation1997) might make those groups better represented than in a majoritarian electoral system and indeed, in terms of pure descriptive representation, Belgian assemblies are doing quite well in terms of presence of women and of ethnic minorities (Celis, Meier, and Wauters Citation2010; Pilet et al. Citation2020a). Second, and perhaps more importantly, Belgium has a mandatory voting system. Mandatory voting increases significantly electoral participation. Around 90% of the electorate do turn out on Election Day. It automatically boosts the participation of citizens from underrepresented groups. All those elements suggest that disadvantaged groups might have incentives to prefer the classical Belgian representative system due to its characteristics (proportional system and mandatory voting) than deliberative mini-publics in which there is an over-representation of privileged citizens and in which inequality in terms of (e.g. cultural or economic) resources might unbalance the deliberative process in favour of the privileged citizens. We will therefore have to be attentive to the peculiarity of the Belgian context when discussing the generalizability of our findings.

In order to test the hypotheses, we are making use of the data collected by the 2019 Belgian Election Study coordinated by the interuniversity consortium Represent.Footnote3 A representative sample of Belgian citizens (based on age, gender and level of education criteria) was surveyed twice, first within the four weeks preceding the 2019 Federal Elections, and a second time in the two weeks that followed Election Day. The survey was conducted online and respondents were recruited by a private polling company (TNS Kantar). Here, we are making use of the first wave of the survey in which 7609 voters were surveyed (3420 in Flanders, 3133 in Wallonia and 1056 in Brussels).

Variables of interest

The Represent survey provides reliable data to study citizens’ attitudes regarding political representation, political attitudes and support for political reforms. First, the questionnaire includes a long list of items capturing voters’ political attitudes and how democracy should be organized. Second, two questions are asked regarding: citizens’ support for consultative mini-public with randomly selected citizens and citizens’ support for participatory budgeting.

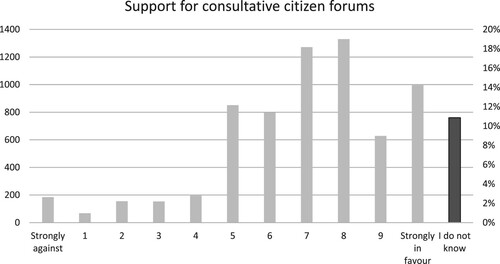

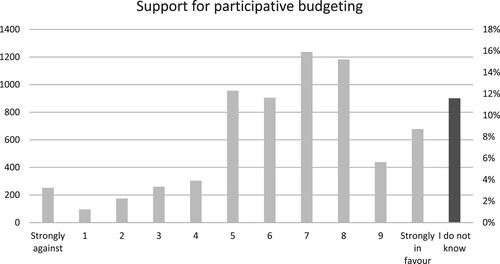

For the purpose of this paper, we use one dependent variable that is the support for the deliberative model of democracy. The dependent variable is composed of two indicators regarding common processes linked to deliberative democracy: deliberative mini-publics and participatory budgeting. The two questions that are asked are the following and a sum of the two indicators (Cronbach’s alpha = .75) constitutes our dependent variable:

In general, are you for or against the organization of consultative citizen forums on important national issues? A citizen forum is an assembly composed of around 30–50 citizens, selected at random, who meet and discuss a certain topic in order to formulate a recommendation that is then transmitted to the parliament. [0-10 scale: 0 = Strongly against; 10 = Strongly in favour]

In general, are you for or against participative budgeting on a national level? Participative budgeting consists of citizens deciding on a portion of the Belgian state’s budget. The citizens involved meet and discuss the way in which they wish to spend that amount in order to support different specific projects. [0-10 scale: 0 = Strongly against; 10 = Strongly in favour]

The questions were formulated to describe each instrument of deliberative democracy well. Further, to guarantee that we gathered informed opinions, an “I do not know” option was available. The distributions of the citizens on both questions are available in appendices 3 and 4. The table below describes the summary statistics for both indicators and of our key dependent variable: “Support for instruments of deliberative democracy” constituted as the sum of both indicators. The dependent variable oscillates between 0 and 20, has a mean of 13.34 and a standard deviation of 4.28. Each instrument of deliberative democracy appears to have a rather positive perception among most of the respondents .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of support for deliberative democracy.

In order to test the first hypothesis related to regime support, the classical survey question regarding satisfaction with democracy is asked. The second hypothesis, related to trust in political institutions consists in capturing citizens’ trust toward the parliament. The last hypothesis of the first block of explanatory variables, related to support for political actors, is an index composed of several indicators that assesses the evaluation of politicians (see Table 1 of the appendix for more details regarding the operationalization).

In order to test citizens’ engagement in relation to the support for deliberative democracy we use their declared level of political interest (H4).Footnote4 Furthermore, to test citizens’ evaluation of their fellow-citizens (H5) an index similar to the one regarding the evaluation of politicians is constituted based on three indicators. The indexes are constituted using a principal component analysis.

Finally, to test H6 to H9 we first identify disadvantaged groups. Despite not allowing to isolate members of ethnic minorities, the data provided by the 2019 Represent Belgian Election Study allow to identify several disadvantaged groups. We rely mainly on groups that are considered as disadvantaged according to the literature on political representation. Indeed, for the last two decades, several scholarships tackled the issue of inequality in terms of political representation. Several studies support the fact that under-privileged citizens tend to have a lower influence on public policies and extensive research highlight the fact that disadvantaged groups such as women, lower educated citizens or economically disadvantaged citizens tend to be less represented than other privileged groups (Bartels Citation2008; Giger, Rosset, and Bernauer Citation2012; Gilens Citation2005; Jacobs and Page Citation2005; Lefkofridi, Giger, and Kissau Citation2012; Lesschaeve Citation2017; Rosset Citation2016; Stockemer and Sundström Citation2019). To those traditionally disadvantaged groups, Celis, Meier, and Wauters (Citation2010) add the groups of the older citizens, the sexual minorities and linguistic minorities for the Belgian case.

This paper will focus on four disadvantaged groups: the women, the lower educated, the people in precarious professional situations (either unskilled workers or unemployed citizens)Footnote5 and the younger population. The selection of those groups is based on the literature regarding the political representation of disadvantaged groups as well as on the descriptive representation of disadvantaged citizens in the Belgian parliament (see Talukder Citation2021). It was decided not to include older population as the age groups of the 60–65 years old tend to be over represented. Indeed, at the time of the data collection in Belgium, 14.3% of the MPs were between 60 and 65 years old (while their share within the adult Belgian population is of 8.1%) while fewer than 1% of the MPs were 30 years old or younger. The same can be said regarding occupation and level of education.

The following variables are therefore used: “women” (woman = 1 and man = 0) “lower educated” (0 = having at least finished full secondary (around 18 years old) education and 1 = having at best finished lower secondary (around 15 years old) education), “Precarious job conditions” (1 = being an unskilled worker or unemployed and 0 = others), and finally “younger citizens” (1= under 30 years old at the time of the survey and 0 = being older than 30 years old). Each “disadvantaged group” is therefore compared to its counterpart which is referred to an “advantaged” group in our analyses. Indeed, the purpose of this study is to have a specific focus on disadvantaged groups compared to other citizens who are not part of a disadvantaged group. It is, however, necessary to underline the fact that it does not mean that citizens who are not disadvantaged necessarily share a unified view regarding instruments of deliberative democracy. One might also expect different effects depending on multiple memberships within different disadvantaged groups. Indeed, being a lower educated man might be different than a lower educated woman and have different impacts in terms of support for instruments of deliberative democracy. In order to control for it, we ran bivariate statistics on the dependent variable for each combination of disadvantage and we did not find any significant results (see ). Finally, while it would have been interesting to analyse further other groups such as ethnic, sexual, and linguistic minorities, the data we are using do not allow us to identify those citizens and to analyse them specifically.

Results

In order to test the hypotheses developed in the first section of this piece, we ran several regression models with robust standard errors. We start with a test of the hypotheses developed for the general population (H1 to H5). The dependent variable is “support for deliberative democracy” based on citizens’ support for two instruments of deliberation: participatory budgeting and consultative citizens’ forums. Each model tests separately each block of independent variable (e.g. political (dis)satisfaction, political interest/competence, citizens evaluations of fellow citizens and under-represented citizens). The last model tests all explanatory factors together, which allows to assess the impact of the variables while controlling for other explanatory variables. allows us to have a better grasp of the factor that might impact citizens’ support for deliberative democracy. While some of the hypotheses find support others might be rejected.

Table 2. Multivariate linear regression (OLS) to explain support for deliberative democracy.

The first broad explanation that could explain citizens’ support for deliberative democracy is linked to citizens’ attitude toward political actors and more specifically citizens’ dissatisfaction. Three hypotheses were considered regarding this specific element: the respondents’ satisfaction with democracy (H1), trust in representative institutions (H2) and evaluations of the politicians (H3). The results from models 1 and 5 lead us to the conclusion that H3 could be corroborated and that the key factor (in terms of attitude toward political actors) that explains citizens support for deliberative democracy might be linked to the evaluation of the politicians. Indeed, the relationship is significant in model 1 but also in model 5. H2 is partially corroborated as the relationship is significant in model 1 but is not significant anymore when we control for other variables. H1 can be rejected as it does not show a significant relationship with support for deliberative democracy. Therefore, what our findings seem to indicate is that what drives Belgian citizens to support deliberative democracy lies in their low levels of specific support towards elected politicians. Support for deliberative democracy is, by contrast, not rooted in (low) diffuse support in representative institutions or in democracy.

The second set of explanatory factors are related to the citizens’ views towards their own interest to engage in politics (Schuck and de Vreese Citation2015). Our hypothesis for this second set of attitudes is confirmed. We find, indeed, that support for deliberative democracy is higher among citizens who feel more politically interested (H4). Such findings confirm the “engaged citizens” explanation underlined by Bedock and Pilet (Citation2020b) as well as by Gherghina and Geissel (Citation2020).

These last findings can be directly connected to the third set of political attitudes – which is that some citizens would be reluctant towards deliberative democracy because they are not very confident in the political skills of other citizens (H5). Our findings seem to corroborate this expectation. Citizens holding more positive evaluations of their fellow citizens are significantly more likely to be supportive of deliberative democracy. Furthermore, the percentage of variance explained by this attitude is quite large (11%). Actually, it is much higher than the other variables and might indicate that the evaluation of fellow citizens is of crucial importance when studying support for instruments of deliberation.

We can now move to the second part of our study, by looking more specifically at the attitudes of citizens from four disadvantaged groups – women, younger citizens, lower educated citizens, citizens in precarious professional situations – towards deliberative democracy. Our first hypothesis about such groups (H6) was that they would be more supportive of deliberative democracy. It is tested in the regressions presented in for models 4 and 5. Model 4 tests for the impact of socio-demographic variables related to our disadvantaged groups alone and we see that for only one group – women – there is a statistically significant effect. Only women are significantly more in favour of deliberative democracy. In model 5, the same variables are included but controlling for our other relevant factors. The statistically significant positive effect remains for women and we see the same effect for a second group: citizens aged below 30 years old. For the two other groups, we see no statistically significant effect. It is especially interesting since these last two groups are not only politically less well represented – like women and younger citizens – but they are also socioeconomically disadvantaged within Belgium. Yet, it does not lead that to call for political reforms towards deliberative democracy.

This difference leads us to dig a bit deeper and to try understanding what factors could shape support for deliberative democracy within disadvantaged groups. More precisely, we propose to examine whether the drivers of support (or opposition) to deliberative democracy are the same for citizens belonging to politically disadvantaged groups and their counterparts. As developed above (see hypotheses 7–9), there are theoretical reasons to expect that some factors would have a different impact for (at least some) disadvantaged groups.

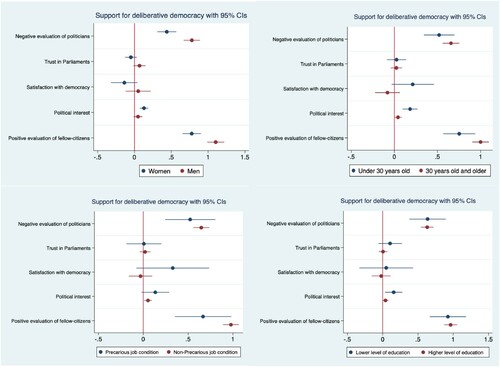

The second step of the analysis is, thus, to conduct multivariate regression analyses with interaction effect between each theoretical explanation and disadvantaged citizens to have a better grasp of the explanatory factors that have an impact on support for deliberation among specific disadvantaged groups. In order to verify it, we have run additional regressions examining the difference in the effects of each independent variable for citizens from advantaged and disadvantaged groups. We can visualize these differences in the figures below, which display the coefficient for each independent variable of the models and allows to distinguish the effects for each disadvantaged group.Footnote6

The main finding from these figures is that there are no major differences in variables that shape support for deliberative democracy among citizens from disadvantaged groups and citizens from advantaged groups. All factors tend to go in the same direction. It is first true for the negative evaluation of politicians, which increases support for deliberative democracy in all disadvantaged and advantaged groups. In the same vein, positive evaluation of fellow citizens pushes citizens from both disadvantaged and advantaged groups to back deliberative democracy. We should therefore reject H7 and H9 .

Figure 1. Multivariate regressions’ coefficient plot between disadvantaged groups and their counterparts.

The only exception could be for political interest. For all groups, there is a modest positive effect of political interest on support for deliberative democracy. But the effect is not significantly different from 0 for three advantaged groups: men, respondents aged above 30 years old, and higher educated respondents. There is therefore a bit of support for H8.

Yet, there is also another way of looking at those figures: comparing respondents within more disadvantaged and more advantaged groups. Instead of looking at the direction of the effects of our independent variables, we might look at their magnitude. Once again, differences are often not major. There are rarely statistically significant differences between the effects of the factors for advantaged and disadvantaged groups. But there are a few exceptions. First, regarding the negative evaluation of politicians, the effect is significantly lower for women than men. Second, we can also see that the effect of how respondents evaluate their fellow citizens on support for deliberative democracy is significantly stronger among male compared to female respondents. Finally, there is a statistically significant difference between respondents aged below and over 30 years old for the effect of political interest on support for deliberative democracy. The effect of this variable is significantly stronger among younger citizens.

For the rest, differences in the magnitude of the effect of the variables examined might exist but are not statistically significant. Here again, it appears that the dynamics at play to understand support for deliberative democracy are not radically different among Belgian citizens of more disadvantaged and advantaged groups. At best we can argue that citizens from advantaged groups are a bit more influenced by their negative evaluation of politicians and by their positive evaluation of fellow citizens. Among citizens from more disadvantaged groups, these factors also play a key role, but also observe an impact of political interest. Among disadvantaged groups, support for deliberative democracy is driven by political dissatisfaction and by trust in the political competence of fellow citizens, but it is also stronger among those who show higher levels of political interest.

Discussion and conclusion

While deliberative processes are extensively studied, research aiming to grasp citizens’ support for instruments of deliberative democracy remain scarce (Font, Wojcieszak, and Navarro Citation2015; Bedock and Pilet Citation2020b, Citation2020a; Gherghina and Geissel Citation2020). This article aimed, therefore, to contribute to the literature with evidence from the Belgian case. The Belgian case is of interest as it has experienced numerous cases at the regional and local level (Vrydagh et al. Citation2020 find 15 between 2016 and 2018) and that several Parliaments within the country institutionalized (or are in the process of institutionalizing) deliberative instruments such as the “Ostbelgien Model” or mixed deliberative parliamentary commission.

The second aim of the paper, further than contributing to the understanding of support for deliberative democracy in Belgium, is to shift the focus from the whole population to specific disadvantaged groups. Indeed, literature on political representation highlighted that several groups within the population are under-represented in terms of descriptive and substantive representation. This peculiar relationship might induce different dynamics in how they relate to political reforms (Ceka and Magalhaes Citation2020). We have therefore examined the attitudes of citizens from four political disadvantaged groups in Belgium – women, younger citizens (below 30), lower educated citizens, and citizens in more precarious professional situations, and compared them to the attitudes of citizens from more advantaged groups.

First, we have seen that only for two of these groups being politically disadvantaged translated into greater support for deliberative democracy: it is the case for women and for younger citizens. We do not observe such difference for lower educated citizens and citizens in more precarious professional situations. In order to understand better these findings, we have looked at the factors shaping attitudes towards deliberative democracy within these groups. We have first seen that they were for the most part driven by the same factors as for the rest of the Belgian population. Support for deliberative democracy is mostly found among citizens with more negative evaluations of politicians and higher trust in the political competence of their fellow citizens. Yet, there is also one factor that marks a slight difference: political interest. This variable does not affect much support for deliberative democracy within more advantaged groups. By contrast, among disadvantaged groups, it has a small but significant positive effect. Being in favour of deliberative democracy, within these groups, is correlated with being more politically interested. This element might explain why we observe more support for deliberative democracy among women and younger citizens, where political interest could be more present, than among lower educated citizens and citizens in more precarious professional situations. Other explanations regarding those two groups could be related to the fact that they tend to vary in terms of socio-economic conditions but also due to the characteristics of deliberative instruments. Deliberative democracy instruments may be perceived as innovative, as inclusive and as decision-making processes that tend to favour consensus and empathy. These values might be more appealing for women and younger citizens.

These findings provide interesting new insights for the study of public attitudes towards deliberative democracy, and especially when it comes to citizens from more disadvantaged groups. Yet, other approaches would be useful to dig deeper into this topic. First, it would be interesting to compare support for direct and deliberative democracy among disadvantaged groups as most citizens would be more familiar with the earlier. Instruments of direct democracy are quite straightforward and easily understood by citizens while deliberative instruments (including sortition) have benefits that are more complex (Vandamme and Verret-Hamelin Citation2017) and less exposed. Moreover, instruments of direct democracy may be perceived by citizens from disadvantaged groups as a more direct empowerment due to the fact that it gives everyone a direct say into policy-making. Deliberative democracy innovations may still give a greater role to citizens with more resources and could be perceived as more elitist. Another interesting avenue for future research would be to compare the role of objective descriptive under-representation – which is the way we have defined our disadvantaged groups – with subjective perceptions of being badly represented politically. Some citizens from our disadvantaged groups may still feel well-represented. It would be interesting to examine whether it affects how they relate to deliberative democracy innovations. These two questions, like several others underline in the other articles of this special issue, would definitely be good candidates for new research on the topic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

David Talukder

David Talukder is a PhD candidate at the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB). He works within the research project “Reforming Representative Democracy” and write a dissertation about the political representation of disadvantaged groups and their support for reforms. His main research interests are democratic innovation, political representation, and democratic reforms.

Jean-Benoit Pilet

Jean-Benoit Pilet is a professor of political science at Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB). He works on elections, political parties, and democratic reforms. He has recently co-authored Faces on the Ballot. The Personalization of Electoral Systems in Europe (OUP, 2016, with Alan Renwick) and The Politics of Party Leadership (OUP, 2016, with William Cross). He is currently the Principal Investigator of the project POLITICIZE (ERC Consolidator Grant) that examines citizens attitudes towards democratic innovations as well as technocratic governments.

Notes

1 There is also quite some literature on ethnic minorities. Yet, unfortunately, the sample of the 2019 Belgian Election Study does not include a question that allows to identify respondents from ethnic minorities to run analyses on them in this article.

2 Nevertheless, the deliberative processes (with randomly selected participants) are less current in the Dutch speaking community (Vrydagh et al. Citation2020; Rangoni, Bedock, and Talukder Citation2021).

3 Stefaan Walgrave (PI – University of Antwerp), Pierre Baudewyns (UC Louvain), Karen Celis (VUB), Kris Deschouwer (VUB), Sofie Marien (KU Leuven), Jean-Benoit Pilet (ULB), Benoît Rihoux (UC Louvain), Emilie van Haute (ULB), Virgine van Ingelgom (UC Louvain).

4 We use political interest as an indicator for citizens’ political engagement. A supplementary indicator related to internal political efficacy would have been better but we are unable to make the use of it due to data constraint.

5 The two categories are considered as member of one group as they tend to be disadvantaged. On one hand unskilled workers tend to have difficult working conditions and lower wages in average. On the other hand unemployed citizens are excluded from the labour market and it might be a de-socializing experience (Paugam Citation2006). Further, Bègue (Citation2007) find similarities between unemployed citizens and unskilled workers regarding political attitudes.

6 The detailed regression table is available in Appendix 2.

Bibliography

- Almond, G., and S. Verba. 1963. The Civic Culture. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

- Bartels, Larry M. 2008. Unequal Democracy. STU-Student ed. Princeton University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt7t9ks.

- Bedock, Camille, and Jean-Benoit Pilet. 2020a. “Who Supports Citizens Selected by Lot to Be the Main Policymakers? A Study of French Citizens.” Government and Opposition 56: 485–504.

- Bedock, Camille, and Jean-Benoit Pilet. 2020b. “Enraged, Engaged, or Both? A Study of the Determinants of Support for Consultative vs. Binding Mini-Publics.” Representation June: 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2020.1778511.

- Bègue, Murielle. 2007. ‘Le Rapport Au Politique Des Personnes En Situation Défavorisée : Une Comparaison Européenne : France, Grande-Bretagne, Espagne’. PhD Thesis. http://www.theses.fr/2007IEPP0047/document.

- Bengtsson, Åsa, and Henrik Christensen. 2016. “Ideals and Actions: Do Citizens’ Patterns of Political Participation Correspond to Their Conceptions of Democracy?” Government and Opposition 51 (2): 234–260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2014.29.

- Bengtsson, Åsa, and Mikko Mattila. 2009. “Direct Democracy and Its Critics: Support for Direct Democracy and “Stealth” Democracy in Finland.” West European Politics 32 (5): 1031–1048. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380903065256.

- Bennett, Linda LM, and Stephen Earl Bennett. 1989. “Enduring Gender Differences in Political Interest: The Impact of Socialization and Political Dispositions.” American Politics Quarterly 17 (1): 105–122.

- Bohman, James. 1998. “Survey Article: The Coming of Age of Deliberative Democracy.” Journal of Political Philosophy 6 (4): 400–425.

- Bowler, Shaun, Todd Donovan, and Jeffrey A. Karp. 2007. “Enraged or Engaged? Preferences for Direct Citizen Participation in Affluent Democracies.” Political Research Quarterly 60 (3): 351–362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907304108.

- Brady, Henry E., Sydney Verba, and Kay Lehman Scholzman. 1995. “Beyond Ses: A Resource Model of Political Participation.” American Political Science Review 89 (2): 271–294.

- Caluwaerts, Didier, Benjamin Biard, Vincent Jacquet, and Min Reuchamps. 2018. “‘What Is a Good Democracy? Citizens’ Support for New Modes of Governing’.” In Mind the Gap. Political Participation and Representation in Belgium, edited by Kris Deschouwer, 75–90. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Campbell, Angus, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, and Donald E. Strokes. 1960. The American Voter. New York: John Wiley.

- Carnes, Nicholas. 2016. “Why Are There so Few Working-Class People in Political Office? Evidence from State Legislatures.” Politics, Groups, and Identities 4 (1): 84–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2015.1066689.

- Ceka, Besir, and Pedro C Magalhaes. 2020. “Do the Rich and the Poor Have Different Conceptions of Democracy? Socioeconomic Status, Inequality, and the Political Status Quo.” Comparative Politics 52 (3): 383–412.

- Celis, Karen, Petra Meier, and Bram Wauters. 2010. “Diversiteit, vertegenwoordiging en onderzoek in België.” In: Karen Celis, Petra Meier and Bram Wauters. Ghent Academia Press. http://lib.ugent.be/catalog/pug01:901284.

- Dalton, Russell J. 2004. Democratic Challenges, Democratic Choices : The Erosion of Political Support in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Easton, David. 1965. A Systems Analysis of Political Life. New York: John Wiley.

- Font, Joan, Magdalena Wojcieszak, and Clemente J. Navarro. 2015. “Participation, Representation and Expertise: Citizen Preferences for Political Decision-Making Processes.” Political Studies 63 (S1): 153–172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12191.

- García-Espín, Patricia, and Ernesto Ganuza. 2017. “Participatory Skepticism: Ambivalence and Conflict in Popular Discourses of Participatory Democracy.” Qualitative Sociology 40 (4): 425–446.

- Geißel, Brigitte, and Marko Joas. 2013. Participatory Democratic Innovations in Europe: Improving the Quality of Democracy? Verlag Barbara Budrich.

- Gherghina, Sergiu, and Brigitte Geissel. 2017. “Linking Democratic Preferences and Political Participation: Evidence from Germany.” Political Studies 65 (1_suppl): 24–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0032321716672224.

- Gherghina, Sergiu, and Brigitte Geissel. 2019. “An Alternative to Representation: Explaining Preferences for Citizens as Political Decision-Makers.” Political Studies Review 17 (3): 224–238.

- Gherghina, Sergiu, and Brigitte Geissel. 2020. “Support for Direct and Deliberative Models of Democracy in the UK: Understanding the Difference.” Political Research Exchange 2 (1): 1809474.

- Gherghina, Sergiu, Monika Mokre, and Sergiu Miscoiu. 2020. “Introduction: Democratic Deliberation and Under-Represented Groups.” Political Studies Review, doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929920950931.

- Giger, Nathalie, Jan Rosset, and Julian Bernauer. 2012. “The Poor Political Representation of the Poor in a Comparative Perspective.” Representation 48 (1): 47–61.

- Gilens, Martin. 2005. “Inequality and Democratic Responsiveness.” Public Opinion Quarterly 69 (5): 778–796.

- Hayes, Bernadette C, and Clive S Bean. 1993. “Political Efficacy: A Comparative Study of the United States, West Germany, Great Britain and Australia.” European Journal of Political Research 23 (3): 261–280.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1990. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Political Science : Sociology. Princeton University Press. https://books.google.be/books?id=ztYnOnSgs1EC.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1997. “Postmaterialist Values and the Erosion of Institutional Authority.” In Why People Don’t Trust Government, edited by Joseph S. Nye and David C. King. Cambridge, MA/London: Harvard University Press.

- Jacobs, Lawrence R, Fay Lomax Cook, and Michael X Delli Carpini. 2009. Talking Together: Public Deliberation and Political Participation in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Jacobs, Lawrence R., and Benjamin I. Page. 2005. “. ‘Who Influences U.S. Foreign Policy?” ’ The American Political Science Review 99 (1): 107–123.

- Landwehr, Claudia, and Thorsten Faas. 2016. ‘Who Wants Democratic Innovations, and Why’. Mainz: Universität Mainz.

- Lefkofridi, Zoe, Nathalie Giger, and Kathrin Kissau. 2012. ‘Inequality and Representation in Europe’.

- Lesschaeve, Christophe. 2017. ‘Whose Democracy Is It? A Study of Inequality in Policy Opinion Congruence Between Privileged and Underprivileged Voters in Belgium’.

- Lijphart, Arend. 1997. “‘Unequal Participation: Democracy’s Unresolved Dilemma’.” The American Political Science Review 91 (1): 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2952255.

- Marx, Paul, and Christoph Nguyen. 2016. “Are the Unemployed Less Politically Involved? A Comparative Study of Internal Political Efficacy.” European Sociological Review 32 (5): 634–648.

- Niessen, Christoph, and Min Reuchamps. 2019. ‘Designing a Permanent Deliberative Citizens’ Assembly’. Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance Working Paper Series 6.

- Norris, Pippa. 2011. Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. Cambridge University Press. https://books.google.be/books?id=slFcAQAACAAJ.

- Paugam, Serge. 2006. “L’épreuve Du Chômage: Une Rupture Cumulative Des Liens Sociaux?” Revue Européenne Des Sciences Sociales. European Journal of Social Sciences XLIV–135: 11–27.

- Paulis, Emilien, Jean-Benoit Pilet, Sophie Panel, Davide Vittori, and Caroline Close. 2020. “The Politicize Dataset: An Inventory of Deliberative Mini-Publics (DMPs) in Europe.” European Political Science 20: 521–542.

- Pilet, Jean-Benoit, David Talukder, Maria Jimena Sanhueza, and Jeremy Dodeigne. 2020a. La Représentation Politique Des Femmes Au Niveau Communal En Wallonie Après Les Élections de 2018’. In Les Élections Locales Du 14 Octobre 2018 En Wallonie et à Bruxelles: Une Offre Politique Renouvelée?, 193–216. Vanden Broele.

- Pilet, Jean-Benoit, David Talukder, Maria Jimena Sanhueza, and Sacha Rangoni. 2020b. “Do Citizens Perceive Elected Politicians, Experts and Citizens as Alternative or Complementary Policy-Makers? A Study of Belgian Citizens.” Frontiers in Political Science 2: 10.

- Pow, James, Lisa van Dijk, and Sofie Marien. 2020. “‘It’s Not Just the Taking Part That Counts:‘Like Me’Perceptions Connect the Wider Public to Minipublics’.” Journal of Deliberative Democracy 16 (2): 43–55.

- Rangoni, Sacha, Camille Bedock, and David Talukder. 2021. “More Competent Thus More Legitimate? MPs’ Discourses on Deliberative Mini-Publics.” Acta Politica June. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-021-00209-4.

- Río, Adrián del, Clemente J Navarro, and Joan Font. 2016. “Citizens, Politicians and Experts in Political Decision-Making: The Importance of Perceptions of the Qualities of Political Actors.” Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas (REIS) 154 (1): 83–120.

- Rosset, Jan. 2016. Economic Inequality and Political Representation in Switzerland. Springer.

- Schlozman, Kay Lehman, Sidney Verba, and Nancy Burns. 2001. The Private Roots of Public Action: Gender, Equality, and Political Participation. London: Harvard University Press.

- Schuck, Andreas R. T., and Claes H. de Vreese. 2015. “Public Support for Referendums in Europe: A Cross-National Comparison in 21 Countries.” Electoral Studies 38: 149–158.

- Smith, Graham. 2009. Democratic Innovations: Designing Institutions for Citizen Participation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Stockemer, Daniel, and Aksel Sundström. 2019. “Young Deputies in the European Parliament: A Starkly Underrepresented Age Group.” Acta Politica 54 (1): 124–144.

- Talukder, David. 2021. ‘Do Underrepresented Citizens Perceive That They Are Underrepresented?: An Inquiry into Belgian Disadvantaged Groups’ Satisfaction with Policies Implemented by the Government.’ In ECPR Joint Sessions of Workshops, 1–20.

- Thomassen, Jacques. 2015. “What’s Gone Wrong with Democracy, or with Theories Explaining Why It Has?” In Citizenship and Democracy in an Era of Crisis, edited by Thomas Pogunkte, Sigrid Rossteutscher, Rüdiger Schmitt-Beck, and Sonja Zmerli, 56–74. London: Routledge.

- Traber, Denise, Miriam Hänni, Nathalie Giger, and Christian Breunig. 2021. “Social Status, Political Priorities and Unequal Representation.” European Journal of Political Research 1–23.

- Vandamme, Pierre-Etienne, and Antoine Verret-Hamelin. 2017. “A Randomly Selected Chamber: Promises and Challenges.” Journal of Public Deliberation 13 (1): 1–24.

- Vrydagh, Julien, Jehan Bottin, Min Reuchamps, Frédéric Bouhon, and Sophie Devillers. 2021. “Les Commissions Délibératives Entre Parlementaires et Citoyens Tirés Au Sort Au Sein Des Assemblées Bruxelloises.” Courrier Hebdomadaire Du CRISP 7: 5–68.

- Vrydagh, Julien, Sophie Devillers, David Talukder, Vincent Jacquet, and Jehan Bottin. 2020. “Les mini-publics en Belgique (2001-2018) : expériences de panels citoyens délibératifs.” Courrier hebdomadaire du CRISP 2477–2478 (32–33): 5–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.3917/cris.2477.0005.

- Vrydagh, Julien, Sophie Devillers, Vincent Jacquet, David Talukder, and Jehan Bottin. Forthcoming. “Thriving in an Unfriendly Territory: The Peculiar Rise of Minipublics in Consociational Belgium.” In Belgian Exceptionalism. Belgian Politics between Realism and Surrealism. London: Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Belgian-Exceptionalism-Belgian-Politics-between-Realism-and-Surrealism/Caluwaerts-Reuchamps/p/book/9780367610241#sup.

- Webb, Paul. 2013. “Who Is Willing to Participate? Dissatisfied Democrats, Stealth Democrats and Populists in the United Kingdom: Who Is Willing to Participate?” European Journal of Political Research 52 (6): 747–772. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12021.