Abstract

The paper contributes to the field of party politics and the use of deliberative practices by analyzing how a Hungarian political party uses deliberation to its own advantage. Our focus is on the National Consultation, which was designed by the elite populist radical right party Fidesz – Hungarian Civic Alliance (Fidesz-MPP) in 2005 as a deliberative practice to increase the party’s social embeddedness. The National Consultation became a government-funded questionnaire that is sent to Hungarian citizens by mail. Our article builds on existing typologies to show how the party established deliberative procedures to achieve strategic vote and policy seeking goals, as well as legitimacy and other normative objectives with the electorate. The article uses inductive thematic analysis of 27 semi-structured interviews with Hungarian politicians conducted in 2020. Our results provide evidence that deliberative practices can be hijacked by the political actors.

Introduction

A genuine democracy entails, at least in theory, good relations between citizens and representative institutions. This relationship consists of trust and support of the citizens. In order to consolidate this relationship, representative institutions should fulfill their commitments and prove their willingness to ensure citizens’ welfare (Levi and Stoker Citation2000; Phelan Citation2006; Whiteley Citation2016). When the performance of representative institutions do not meet citizens’ expectations, citizens grow dissatisfied with the overall functioning of the regime (Norris Citation1999; Linde and Holmberg Citation2013; Dahlberg, Linde, and Holmberg Citation2015). One of the sources of popular dissatisfaction is the quality of decision-making (Norris Citation1999). The contemporary challenges raised by the post-materials societies have determined political agendas that imply a greater involvement of citizens in political activities. Representative institutions must be more transparent, inclusive and must provide citizens a greater say in politics (Gherghina, Soare, and Jacquet Citation2020). Earlier research stressed that deliberation could achieve these goals (Andersen and Hansen Citation2007; Caluwaerts and Reuchamps Citation2016; Wolkenstein Citation2016; Dryzek Citation2019). Deliberation was extensively approached in the literature from the standpoint of its internal and external effects as well as how it is used by political parties (Chaney Citation2006; Flinders and Curry Citation2008; Davidson and Stark Citation2011; Wolkenstein Citation2016, Citation2018; Gherghina, Soare, and Jacquet Citation2020). Studies show that political actors use deliberation or direct democracy tools (i.e. referendums) to achieve internal objectives (Gherghina, Soare, and Jacquet Citation2020; Gherghina Citation2019b; Hollander Citation2019). Hiba! A könyvjelző nem létezik. However, little attention is paid to how political actors could use deliberative practices for their own advantage, specifically in countries that are not considered to be authoritarian but have experienced democratic backsliding in the last decade (Bogaards Citation2018).

By bridging studies on party politics and democratic innovations, this article seeks to contribute to the literature by analyzing how Fidesz-MPP (i.e. a populist radical right party) transformed a political tool that initially started as a deliberative process (i.e. the National Consultation) into an instrument employed to achieve political gains. Fidesz-MPP is an appropriate case for studying this phenomenon because the party gained advantage over other political practices (e.g. referendums) in order to consolidate its position in the political arena in the past . Also, Fidesz-MPP stressed that National Consultations provide opportunities to citizens to actively engage into political processes and promote their will (Batory and Svensson Citation2019; van Eeden Citation2019). Therefore, by supporting the creation of positive attitudes toward deliberative practices and conveying to citizens the idea that their involvement in politics is necessary for a streamlined decision-making, Fidesz-MPP grew citizens’ support for these practices while obtaining a tool that could be easily used for its own advantage. We conducted 27 semi-structured interviews with Hungarian politicians. The questions were meant to capture the attitudes of the politicians regarding National Consultation. They were conducted between March and August 2020. The study uses inductive thematic analysis to identify common themes within the politicians’ answers. We identified two main themes: normative objectives (i.e. legitimacy) and strategic objectives (i.e. vote and policy seeking).

This is one of the first attempts to explain how political parties use deliberative practices to their own advantages, perceived in terms of normative and strategic gains. The study contributes to the field of party politics and the use of deliberative practices in three ways. First, it uses original data to explain how political parties can use deliberative practices for their own gains. Second, it proposes an analytical framework that identifies several themes that could be applied in other cases outside Hungary. Third, it shows how deliberative practices can be hijacked by political actors. The results also allow for further comparisons between Fidesz and other cases.

The article is structured as it follows. The next section reviews the literature on deliberation and how it is used by political parties. The second section shows the characteristics of populist parties and how they position themselves in regards to deliberative practices. The third section explains the interests of populist parties in using participatory and deliberative instruments. We then present the research design with an emphasis on case selection, data and methods of data collection and analysis. The fifth section presents the analysis and the results of the study. The conclusion discusses the implications of our analysis and proposes avenues for further research.

Deliberation: features, partisan use and legitimacy

Extensive research has been devoted to explain deliberation and how it can increase the quality of democracies (Fishkin, Luskin, and Jowell Citation2000; Dryzek Citation2004; Caluwaerts and Reuchamps Citation2016; Wolkenstein Citation2018). Deliberation encompasses any process through which individuals engage in discussions motivated by the desire to find proper solutions for specific issues or for making a valuable exchange of information or opinions that could help a stakeholder to adopt a certain course of action (Dutwin Citation2003; Fishkin Citation2010). Genuine deliberations are characterized by balanced, comprehensive, conscientious, informative and substantive discussions (Fishkin and Luskin Citation2005). Also, they fulfill an educative role (i.e. the participants extend their knowledge regarding the discussed topics) and can enhance the sentiment of belonging with the community while increasing participants’ desire to engage in such processes (Cooke Citation2000). Deliberations are usually fair processes through which citizens make their voices heard and lead to outcomes more congruent outcomes between civic and political interests (Fishkin Citation2010).

Harnessing the deliberation’s characteristics and citizens’ positive attitudes towards them, political parties and governments extensively use deliberation for internal and external purposes (Teorell Citation1999; Baiocchi and Ganuza Citation2014; Wolkenstein Citation2016; Jacquet and Does Citation2020). At the internal level, political parties employ deliberation in order to increase the degree of intra-party democracy by creating opportunities for their members or citizens to engage in political debates or the party’s internal decision-making (Croissant and Chambers Citation2010; Loxbo Citation2013). By making their internal processes more deliberative, political parties enhance their transparency and trustworthiness, reduce the gap between elites, party members and citizens, stimulate equality and make the idea of engaging in politics more appealing (Teorell Citation1999; Lehrer Citation2012; Biezen and Piccio Citation2013). Political parties that use deliberation argue that they differ from traditional politics because they bring political processes closely to the citizens. This could be achieved by organizing traditional forms of deliberation (e.g. face-to-face meetings, citizen assemblies) or by involving technologies to create opportunities for online participation (Gherghina, Soare, and Jacquet Citation2020). The employment of technologies for enhancing internal deliberation is extensively used by digital parties that create online opportunities for engagement in discussions or decision-making for their members or external sympathizers (e.g. deliberative forums or platforms) (Borge and Santamarina Citation2016; Bennett, Segerberg, and Knüpfer Citation2017; Vittori Citation2017, Citation2019; Gad Citation2020; Gherghina and Stoiciu Citation2020; Vodová and Voda Citation2020).

At the external level, political parties create opportunities for citizens to engage in deliberative processes aiming at improving the policies that concern their communities. For instance, they support the creation of deliberative mini-publics that represent lower-scale representative forums where randomly selected citizens gather and discuss local issues that affect their neighborhoods (Setälä and Smith Citation2018; Jacquet and Does Citation2020). Similarly, political parties can enforce their bonds with citizens by organizing deliberative events where political elites and stakeholders engage in transparent discussions regarding political or social issues (Davidson and Stark Citation2011). Also, parliamentarian legislators stimulate citizen involvement in deliberative activities by proposing debates concerning topics for which specific social groups manifest increased interest, e.g. women legislators could approach topics of interest for women (Chaney Citation2006). In addition, motivated by the idea of consulting the population towards representative allegations deliberative polling can be summoned or deliberative assemblies can be created for discussing electoral reforms (Flinders and Curry Citation2008; Warren and Pearse Citation2008; Fishkin Citation2009). All of these external deliberative practices represent a transition from a vote-centric to a talk-centric approach and they increase political parties’ legitimacy (Chambers Citation2003; Wampler Citation2008).

Irrespective of the internal or external use of deliberation, political parties employ it for increasing their legitimacy. The latter is synonymous with the right to rule and is associated with concepts such as trust and support for political institutions (Scherz Citation2019). Legitimacy can also be an objective when it refers to the regime’s institutions and principles through which decision-making and the exercise of power occur; or it can be subjective when it concerns the citizens’ perceptions of the performance of political institutions (Gherghina Citation2017). Political actors use deliberation mostly for enhancing the level of subjective legitimacy because deliberative practices are usually perceived by citizens as an inclusive and transparent process that provide more accountable outcomes drawn from their involvement in decision-making (Paxon Citation2020).

Populist parties and deliberation

In the last decades, we have witnessed an increasing support for populist parties that portray themselves as being the proper choices for curing the general dissatisfaction toward representative institutions (Suteu Citation2019; Bartha, Boda, and Szikra Citation2020). Previous research underlines that there are three broad groups of populist parties: right-wing, left-wing and valence parties. These variations refer to the degree of identification to a specific ideology (Zulianello Citation2020). However, there can also be varieties of populist parties belonging to each individual group. For instance, right-wing populism, which usually combines nativist discourses with authoritarian rule, is divided between the populist radical right, neoliberal populism and national-conservative populists – the latter variation encapsulating a category of radicalized right-wing populist parties such as Fidesz-MPP (Zulianello Citation2020). Populist parties divide the society between the ‘treacherous political elites’ and the ‘honest citizens’ (Mudde Citation2007). They support the idea that a country should be governed by a strong government which draws its power from the citizens (Anduiza, Guinjoan, and Rico Citation2019; Pirro and Portos Citation2021). Populist parties provide plenty of opportunities for the citizens to engage in political processes outside the usual elections (e.g. national consultations, protests, referendums) in order to enhance the degree of subjective legitimacy and trustworthiness (Canovan Citation1999; Dzur and Hendriks Citation2018; Sharon Citation2019; Pirro and Portos Citation2021).

Even though populist parties provide an apparent support for the citizens’ engagement in politics, they do not support deliberative practices without scrutiny (Zaslove Citation2021). Taking into account the above-mentioned features of genuine deliberation, the interests of the populist parties can be endangered when different groups of citizens (e.g. those belonging to a minority group) that oppose the populist party’s views make their voices heard during a deliberative action (Suteu Citation2019; Bartha, Boda, and Szikra Citation2020). However, the fact that populists do not support deliberation does not mean that they do not use it in order to achieve specific objectives. Earlier research stresses that there are forms of authoritarian deliberation where political actors seek to gain legitimacy from the citizens through these practices (Jiang Citation2010). Simply put, authoritarian forms of deliberation are in line with the general tenets of deliberative practices in which citizens and officials engage in substantive discussions, but in essence, these processes are highly controlled by the power-holders and the discussions cannot go beyond the borders imposed by the political authorities (He and Warren Citation2011). In a similar vein, populist parties can employ highly-scrutinized deliberative practices just to make sure that will gain the necessary subjective legitimacy for approaching a specific course of action (Zaslove Citation2021).

Research design

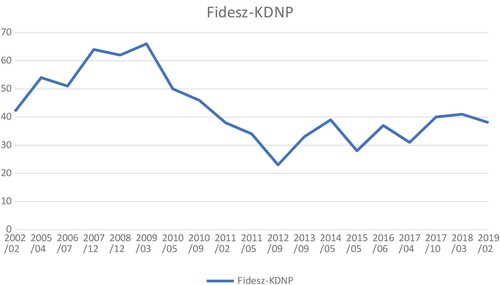

This article focuses on Hungary between 2005 and 2021 in order to embrace the development on National Consultation in line with the change of the Hungarian political system during that time period. While in 2005 the party was in opposition, this time period was following by the 2010 ‘critical elections’ when Fidesz gained a 2/3 majority of seats in the parliament and has since won three consecutive parliamentary elections (2010, 2014, 2018), keeping its 2/3 majority in Parliament. Over the years, Orbán turned Hungary into a plebiscitary leader democracy (Körösényi, Illés, and Gyulai Citation2020). Fidesz could reach and mobilize a relatively significant part of the Hungarian electorate both in opposition and in government and a part of that success is a result of the party’s connection with the citizenry. In his article which has built a bridge between the very different literatures on direct democracy and illiberal populism, van Eeden (Citation2019, 710) argues that Hungary is ‘the vanguard of contemporary post-democratic processes’ and analyzed referendums initiated by the Fidesz-MPP party within the theoretical framework of post-democracy. Batory and Svensson (Citation2019) specifically focused on the practice of national consultation by applying a descriptive framework based on a synthesis of previous literature on participatory instruments. We argue that the 2005 National Consultation was invented as a special, top-down instrument of deliberation and became a strategic tool of the Orbán government after 2010. The process was successful – if success is measured by mobilization of the party’s own electorate, the voter camp of the party (see Graph 1).

Graph 1 . Support for Fidesz among likely voters (2005-2018). Source: Median Public Opinion from Market Research Institute.

The National Consultation was born in a context where Fidesz-MPP faced low levels of party identification. In February 2005, Viktor Orbán announced in his state of the nation address, a speech made annually, that a National Consultation process would be organized in order to bring citizens back to politics and to ensure that public life is about the will of the people. The original aim behind the consultation process was to reinvigorate activism of Fidesz-MPP supporters and to reshape public perceptions about the party. The body responsible for National Consultation was a Consultative Board that was not (officially) linked to the party. On the 28th of April, a questionnaire was presented by the board to the press that asked seven questionsFootnote1 about citizens’ perceptions of Hungary’s democratic transition. The deadline for filling and sending the questionnaire was 30th of July. On May 18th, the National Consultation Center was opened for citizens who wanted to talk about public life, consult members of the Board, or wanted to submit a consultation questionnaire. On June 17th, four national consultancy buses started their one-month trip to nearly 700 settlements. Results of the consultation were presented on the Conclusion Day (October 16) by members of the Consultative Board. A large outdoor event was held where board members responded to participant’s questions and the event ended with a concert (Meghallgattuk Magyarországot Citation2005).

Although from the perspective of the normative theoretical framework of input, throughput and output legitimacy, the national consultation process has lost much of its legitimacy over the years (). We argue that the first round of national consultation can be considered a deliberative process. In terms of input legitimacy, in 2005 the national consultation facilitated a deliberative process for citizens who visited the National Consultation Center or decided to meet members of the board during the events of the consultation (quality of representation). The Center was open for a period of three months and was enabled to consult members of the Board. The agenda of the discussions was pre-determined: participants were invited to answer seven questions on the broad topic of how they imagined the future of Hungary. Five out of the seven questions posed were open ended, allowing participants to raise their own ideas, while the personal meetings with board members allowed for a dialogue (even though those dialogues were not recorded) (agenda setting). As for epistemic completeness, members of the board held speeches at different events of the consultation about the aims of the consultation, but there were no small-group discussions organized and no information booklets were provided to participants during the events.

Regarding throughput legitimacy, participants were allowed to consult members of the board and to fill in a questionnaire. At a local level, village parliaments were organized and a bus trip was also organized for the members of the board to make contact with 700 settlements of Hungary. As an incentive, a lottery was organized by the foundation for participants (the jackpot was a family car). Nevertheless, engaging minority and/or marginalized groups to participate in the consultation process was not a priority of the organizers (inclusiveness). Activists (many of whom were Fidesz members) helped to organize events and they were also in charge of collecting questionnaires. Therefore, it can be assumed that the overwhelming majority of the respondents sympathized with the Fidesz party (limiting the contextual independence of the process). There was no incentive to help participants to reach a consensus or confront different positions: the citizens’ role in the decision-making process was restricted to filling in the questionnaires (quality of decision making). Consequently, the consultation process somewhat resembled a political rally except that it was not organized during an electoral campaign period and the speakers were not political candidates for any position.

Regarding the output legitimacy, the National Consultation Foundation published a book (Meghallgattuk Magyarországot Citation2005) about the results of the consultation, providing not only the stories of the board members and the main results of the questionnaire, but also a statistical analysis of the preferences of participants (public endorsement). Although only the politicians of Fidesz (especially Viktor Orbán) made references to those results, the evidence taken from the consultation was made public and theoretically was available to any decision maker (weight of the results). The results of the consultation made clear that the majority of its participants were tired of the daily worries of living. A higher standard of living was identified as a common aim of Hungarians. On 23 October 2006, Viktor Orbán announced that Fidesz had submitted seven questions to the National Election Office that were related to the standard of living, fees and prices (in line with the results of the national consultation, thus indicating some extent of responsiveness). After three of the questions (on abolishing co-payments, daily fees at hospitals and college tuition fees) were officially approved on 17th December 2007, a referendum was held on 9th March 2008. As the referendum reached the threshold for validity (50.5% of voters participated) and all three proposals were supported by a majority (82–84%) of the voters, the outcome of the referendum was legally binding (consequently the weight of the results of the national consultation process increased significantly). The socialist-liberal coalition in power at the time had to abolish the three fees. The referendum helped Fidesz to retain momentum until the next general elections in 2010, in which they gained a landslide victory (Pállinger Citation2016).

After Fidesz-MPP won the 2010 parliamentary elections, the National Consultation was institutionalized and became a communication tool of the Prime Minister. The a government-funded questionnaire would be sent to Hungarian citizens by mail. It contained a letter from the Prime Minister that is followed by a list of selectively chosen and carefully-crafted questions. Since 2010, ten National Consultations were organized and each consultation had a specific topic. The number of questions and the format of the questionnaire was simplified over the years (Appendix 1) and the process has lost its deliberative character ()

Table 1. Loss of input, throughput and output legitimacy of National Consultations.

The case study we present below is based on documentary analysis and on 27 semi-structured interviews that we have conducted with Hungarian politicians in March-August 2020 to detect the attitudes of political leaders toward the National Consultation which we triangulate through a variety of documents. In order to cover the three faces of party organization (Katz and Mair Citation1993, 594) elected representatives of party in public office (e.g. presidents of each party, heads of the Parliamentary Groups, selected Members of the European Parliament), party members in the central office (e.g. operative director) and party members on the ground (party leaders at the local level, mayors, local councilors) were invited to take part in the research. In order to reveal party links to society, party experts (e.g. heads of the Party FoundationFootnote2, spin doctors) were also invited. The interview guide contained two questions about National Consultation. One question asked the interviewee about previous experience about National Consultation (positive and negative aspects of the consultation process) while another allowed respondents to rate five participation/consultation processes based on how close they felt to it. The average duration of the semi-structured interview was 50 minutes. As illustrated in Appendix 2, the interviewees came from ten Hungarian parties.

We use data-driven thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) to identify common themes within the interviews. The coding was inductive: instead of using pre-established themes we read all interviews and identified potential themes. The procedures consisted of three phases ().

Table 2. Coding scheme for the use of National Consultation.

Fidesz-MPP and the hijacking of participatory tools

Let us start by introducing the Hungarian political system. From the perspective of challenges to democracy, the political system of Hungary was described as a ‘diffusely defective’ democracy (Bogaards Citation2018); a political system in which both the relations among parties and the relationship of the party system with its environment is affected by populist polarization (Enyedi Citation2016b).

Since 2010, the country has been governed by the same party (Fidesz-MPP) that enjoys great support for its political and economic reforms (Batory Citation2016; Scoggins Citation2020). The dominant parties of the Hungarian party system consist of eight established, parliamentary parties: Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP), Democratic Coalition (DK), Dialogue (Párbeszéd), Politics Can Be Different (LMP), Alliance of Young Democrats – Hungarian Civic Alliance (Fidesz-MPP), Christian Democratic People's Party (KDNP), Movement for a Better Hungary (Jobbik), Our Homeland Movement (Mi Hazánk) and two additional parliamentary parties Hungarian Two-Tailed Dog Party (MKKP), Momentum Movement (M). Although in the last two decades, parties moved gradually toward a more centralized party structure with mostly un-contested intra-party leadership selection (Illonszki and Várnagy Citation2014). Hungarian political parties have recently provided several new practices to coordinate candidate selection, to consult citizens about policy issues at national or local levels, or to make their presence visible in the digital environment (Batory and Svensson Citation2019; Oross and Tap Citation2021)

After the 2010 elections, Fidesz-MPP became the dominant political party in Hungary (Pirro Citation2015). Fidesz-MPP is a populist radical right party that promotes anti-elitist and conservative principles and supports both the idea that power should be given to the citizens and the need for political reforms aimed at reshaping the defficient Hungarian political establishment (Bartha, Boda, and Szikra Citation2020). Viktor Orbán and his party (i.e. Fidesz-MPP) have continuously valorized specific political or social crises that enhanced citizens’ dissatisfaction toward Hungarian politics (e.g. poor economic development, immigration, lack of political alternatives, social welfare) and turned them into subjects that increased legitimacy (Batory Citation2016b; Dzur and Hendriks Citation2018). Orbán promoted a paternalist approach from which Fidesz-MPP bacame a political force capable of protecting the Hungarian people and the nation’s interests (Enyedi Citation2016a; Bartha, Boda, and Szikra Citation2020).

However, in spite of the fact that Fidesz-MPP is considered a populist party that supports the idea that citizens should participate actively in political processes, its actions resemble more to a top-down approach in which the entire decision-making is placed in the hands of a strong government and the participatory processes issued for the citizens (e.g. referendums) are controlled by the authorities that only want to gain formal legitimacy for its actions (Enyedi Citation2016a). The literature on hijacking direct democracy practices is vast and evidences from Bulgaria (Stoychev and Tomova Citation2019), Poland (Hartliński Citation2019), Romania (Gherghina Citation2019a) and Slovakia (Nemčok and Spáč Citation2019) show that political actors manipulate referendums in order to achieve partisan gains. These studies emphasized that referendums were employed by the authorities not to give citizens a bigger say in politics, but rather for obtaining legitimacy for specific actions, mobilizing the electorate or outplaying the political competition. Similar use of referendums was encountered in Hungary where Fidesz-MPP gained advantage over the 2004, 2008 and 2016 referendums to attain specific goals and dethrone the political establishment (van Eeden Citation2019). Valorizing the social realities (i.e. the financial or migrant crisis) and the sensitive subjects of the referendums, Fidesz-MPP promoted extensive campaigns through which it suggested what answers should be given by the citizens, emphasizing how important these practices are for citizen empowerment in politics. By Fidesz-MPP’ mischievous instrumentation of referendums, the party managed to gain electoral success and secure its position in the political arena (van Eeden Citation2019).

Similarly, we expect that other political practices could be hijacked by political parties in order to fulfil strategic goals. For instance, the latter could take advantage over the citizens’ positive attitudes toward deliberation and turn it into an instrument for increasing popularity or promoting its political agenda (Fournier Citation2011; Pascolo Citation2020). We argue that an example in support of the previous statement is the 2015 Hungarian National Consultation (Batory and Svensson Citation2019). In this paper we argue that national consultations can be considered deliberative practices not only because they meet several features of deliberation (i.e. informative character, community-belonging sentiments, valuable input generators), but because they create opportunities for citizens to engage in discussions regarding the topics they impose (see the research design). Therefore, the 2015 National Consultation in Hungary was instrumented by Fidesz-MPP in a similar way the party manipulated the aforementioned referendums (i.e. Orbán manipulated the National Consultation questionaires and suggested which answers citizens should give in order to gain legitimacy for his anti-European stances). By doing this, the National Consultation did not deliver meaningful input because the responses were biased because Fidesz-MPP controlled the process. Due to Fidesz-MPP’ negative campaign toward immigrants, the National Consultation enhanced only xenophobic attitudes and fear of migrants and supported the idea that these mechanisms could be misused and abused by decision-makers (Batory and Svensson Citation2019). Accordingly, we will explain in detail how a participatory process (i.e. the National Consultation) that started as a deliberative instrument was hijacked by Fidesz-MPP and transformed into an instrument for increasing the party’s legitimacy similar to the cases in which deliberative practices are used by authoritarian governments.

In order to assess actors and practices according to how they perform different objectives of deliberation in the Hungarian context, we used the typology of Gherghina and Jacquet (Citation2021) as an analytical framework that aims to provide a common understanding about how and why parties establish deliberative procedures. While the first branch of the analytical framework refers to the issue of deliberation, showing that external deliberative practices tackle the selection of people and particular policies, the second refers to the goals (strategic objectives: vote-seeking behavior, office-seeking behavior and policy-seeking behavior; and normative objectives: legitimacy, efficacy of decision-making and educative function) of the deliberative practices.

Analysis and results

From our interviews with politicians, the arguments behind the use of National Consultation are clearly outlined in this finding section. We explore those arguments and contextualize them by highlighting the related characteristics of the process by bringing examples. As for the framework of Gherghina and Jacquet (Citation2021) in our analysis we found that interviewees referred to the second branch – strategic and normative objectives – for the use of National Consultation ().

Table 3. An overview of the themes covered in the interviews.

Strategic motivations

The discourse with Hungarian politicians and experts revolved around two topics: vote seeking and policy seeking. Regarding vote-seeking, reaching out to a significant part of the Hungarian electorate (between 1 and 3 million voters responding to the questionnaire) was the most often mentioned goal associated with the use of National Consultation. Regardless of belonging to the opposition or to the government, politicians agreed that Fidesz-MPP has invested in the National Consultation as part of efforts to increase the party’s social embeddedness. Politicians of the opposition recognized ‘the systematic work that Fidesz-MPP has put into national party building (Á.D.)’ and explained that ‘the aim is to strengthen their own camp, it is in their interest, to hold their voters together (O.D.)’. An expert of another opposition party claimed that the ‘National Consultation is about Fidesz keeping in touch with its own constituents (…) as Fidesz voters are the ones who send it back. (E.I.)’. As an example to the efficient use of the process, we mentioned that National Consultation, used as a preliminary phase before the EU ‘Migrant Quota’ Referendum, successfully mobilized citizens. Following the National Consultation in 2015 and a referendum campaign in 2016, not only did the campaign appeal to Fidesz’s electoral camp (2.5 million voters), it mobilized a total of 3.6 million citizens who voted in line with the government’s proposition at the referendum.

Critics explained that the government uses National Consultation for collecting data about citizens because ‘they are working on the basis of the Kubatov listFootnote3, this is nothing more than a campaign tool (G.D.N)’. Concerns regarding the protection of personal data were expressed by the Data Protection Commissioner who ordered the deletion of the personal data contained in the questionnaires based on the data protection law in 2011. However, the issue was not solved by the government and the way that personal data was treated during the consultation remained a concern.

Obviously, to ask questions about whether the sun rises in the morning and to organize a consultation on this, or to ask a question in such a way that only the government likes the sure answer, is sure to be good for two things: distraction and database building (J.T.)

Speaking about National Consultation as a campaign tool, one interviewee highlighted that questions are often targeted against people who criticize the policies of Fidesz-MPP. Therefore, the aim of the consultation is partly ‘to present an image of the enemy’ (O.D.). The most influential enemy of the party is the billionaire philanthropist George Soros who is depicted as public enemy number one. In 2017, the ‘National Consultation on the Soros Plan’ mobilized Hungarian citizens based on the conspiracy theory that ‘the bureaucrats in Brussels’ are implementing the Soros Plan that aims to push the languages and culture of European countries to the background (Batory and Svensson Citation2019, 235).

In terms of policy-seeking, politicians agreed that the questionnaires sent by the government focus on policy issues. But National Consultation was defined as a communication tool by ‘which it can steal itself into people’s lives through the mailbox (V.T.Ö.)’. The agenda setting power of the process was also emphasized: ‘It is an effective tool, as the thematic power of such a National Consultation is very high, and thanks to this, Fidesz is able to dominate the political agenda, even for half a year, on the topics on which it conducts national consultations (G.G.)’. The process of National Consultations not only consists of printing (costs are estimated as 2 million EUR for a consultation process) and posting the questionnaires to the citizens, but the government invests (about 11,5 million EUR) into the communication campaign that lasts for several weeks and includes television and online advertising, hiring billboards and newspaper advertisements. Leading politicians of the party refer to the number of citizens who respond to the questionnaire and critics claim that instead of focusing on citizens’ replies, ‘the point is to thematize, to mention issues on which the majority agrees with the Prime Minister (O.J.)’.

Although officially it is the government that is in contact with the citizens on a semi-annual basis, critics argued that the government does not wait for any feedback. Some critics allege that ‘the whole thing is done meaninglessly, the questioning is misleading’ (E.G.), while others claim that ‘the whole thing is such an absurd comedy anyway, because they don’t really ask for anything’ (Ö.Z.). We mentioned earlier two examples regarding the inclusion of under-represented groups regarding the 2011 National Consultation where political leaders felt free to choose which recommendation they want to follow. While the question of providing the right to vote to children and delegating that right to their legal parents had impact on the government’s decision, the government did not act to express its commitment to future generations even though 86% of respondents were in agreement. In line with what we have mentioned earlier about the ever-simplified format of the questionnaire, critics explained that ‘the questions are worded in such a way that there is almost only one answer to it: yes or no’ (O.F.). This is because ‘questions were asked in a controlled way that was favorable to Fidesz’ (O.R.P.). Some politicians consider National Consultation as ‘a propaganda tool, as most of the time the questions include the answer as well’ (N.Á.) and expressed that ‘it is very manipulative throughout, if you look at issues of national consultations then it seems that there are some very general statements of a kind that make it clear to the respondent what the right solution is (D.G.)’.

The other branch of critiques referred to National Consultation as a tool to increase party polarization because the process ‘does not facilitate finding of a middle ground between polarized ideas, but reinforces existing cleavages (E.F.)’. According to politicians of the opposition, the main purpose behind National Consultation is ‘to find issues where the majority supports the policies of the government, to prove that ‘the majority of the country wants it that way’ (…) and that ‘(…), in political terms, it brings a lot to the kitchen for Fidesz, the ruling party’ (O.F.).

Normative objectives

As a normative objective, interviewees mentioned the aim of making the decisions of the government more legitimate. The idea behind promoting National Consultation is Fidesz-MPP’s discourse that depicts the nation as a unitary actor that can only legitimately be represented by the Fidesz-MPP (Herman Citation2016) and National Consultation is a process for that.

Politicians of Fidesz admitted that National Consultation ‘is not a professional polling tool, but a political tool (…) that is suitable for detecting the will of the people and for confirming the government's policy’ (V.J.). Criticizing the process, a politician of the opposition expressed that ‘the government just wants to say a number of people have filled out and agreed with Fidesz’s proposed policies (D.G.)’. Yet, it is typical for the process that politicians of Fidesz-MPP communicate the number of returned questionnaires and only those results that coincide with the intention of the government.

A politician of an opposition party claimed that ‘it can give greater legitimacy to the decisions that the government makes on this basis’ (G.G.). As a clear example, in 2011 the ‘Citizens’ Questionnaire on Fundamental Law’ provided additional legitimacy to the draft constitution because Fidesz-MPP had been criticized for its refusal to hold a referendum concerning the constitution. Questions of the National Consultation in 2015 and the question of the referendum in 2016 were worded parallel to Viktor Orbán’s arguments in opposition to the European Union’s plans to impose mandatory migrant quotas on member states, so the government used this instrument to gather support for its foreign policy (Pállinger Citation2016, 19).

Discussion

Bridging two bodies of literature – party politics and democratic innovations – this article aimed to explain how Fidesz-MPP used the National Consultation to its advantage. The findings indicate that originally the National Consultation promised citizens a bigger say in politics, but over the years the party made instrumental use of the consultation process and it completely lost its deliberative character. While the external use of deliberation implies systematic weighing of rational arguments, the case of National Consultations highlights how political actors can embrace external deliberation in order to use it to further their own interests. While according to the literature external use of deliberation marks the transition from vote-centric to talk-centric conception, in the case of National Consultations, the process was transformed from a talk-centric process into a highly effective strategic instrument that aggregates the preferences of citizens to realize the political aims of Fidesz-MPP and the government.

As Fidesz-MPP has been criticized for its refusal to hold a referendum concerning the constitution, National Consultation was used as a strategic tool for the interest of the party and it has given additional legitimacy to the draft constitution. Because of its design and practice, National Consultation served political purposes as it has lent more credibility to the government, and has provided effective arguments against criticism and an opportunity to shape public opinion. Although National Consultation allowed some groups that are under-represented in day-to-day politics to make their voices heard in relation to constitution-making, the high level of elite control over the whole process led to cherry picking ideas and to a very flexible interpretation of the responses that were received from the citizens. As for including the voice of under-represented groups into constitutional deliberation, the present paper found that deliberative elements had little weight and argued that National Consultation is not an adequate exercise for securing input from under-represented groups into policy making because it serves mainly as an agenda setting opportunity for the government.

Based on the analytical framework of Gherghina and Jacquet (Citation2021), we analyzed 27 interviews that we conducted with Hungarian politicians and experts. Our results allowed us to empirically investigate the party’ approaches to deliberation and we found that the political elite of Fidesz engaged in discussions regarding specific political issues framed in National Consultations for two strategic goals (vote seeking and policy seeking) and one normative objective (making the decisions of the government more legitimate). Regarding the goal of vote seeking, National Consultations mobilized not only the party’s own electorate but also a significant part of the Hungarian electorate beyond the electoral camp of the party, helped the electoral campaign of the party and contributed to the party’s consecutive electoral successes. As for policy seeking, the agenda setting power of the process enabled the party to dominate the political agenda. By communicating the high number of citizens who responded to the questionnaire and answers to issues on which the majority agrees with the Prime Minister, National Consultations also increased party polarization and reinforced existing cleavages among citizens. As a normative objective, we uncovered the objective of making the decisions of the government more legitimate. In 2011, the process provided additional legitimacy to the draft constitution while in 2015 the government was able to gather support for its foreign policy.

Future research can reveal how other parties tackle the selection of people and particular policies, as well as further comparisons between Fidesz-MPP and other cases regarding the goals and normative objectives of parties when using deliberation. Next to interviews documentary analysis of policy documents accepted by the selected party may help to see more clearly how parties refer to the results of deliberative processes. To investigate parties’ approaches toward deliberation, surveys conducted among participants of the deliberative process could inform us not only about the socio-demographic characteristics of participants but also about cognitive and attitudinal changes that happen during such processes.

Acknowledgment

This article is based upon work from COST Action “Constitution-making and deliberative democracy” (CA17135), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniel Oross

Daniel Oross is Research Fellow at the Eötvös Loránd Research Network, Centre for Social Sciences, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Centre of Excellence. His areas of expertise are youth policy, political participation, democratic innovations.

Paul Tap

Paul Tap is Research Assistant at the Department of International Studies and Contemporary History, Babes-Bolyai University. His research interests lie in political leadership, political parties and security studies.

Notes

1 What did Hungary for you? What are the reasons of your disappointment? How do you find life before 1990? What are you afraid of? What decisions would you like to influence? What should be changed? What should be our common goal?

2 In 2004 The Law on Party Foundations introduced the German model of Party Foundations in Hungary. Party foundations are eligible for central funding, though central funding cannot be used to finance the daily operation of parties.

3 A list with Fidesz-MPP’s supporters’ personal data collected under command of the director of the party, Gábor Kubatov. It is believed that it does also contain details about other parties’ voters and their preferences.

References

- Andersen, V. N., and K. M. Hansen. 2007. “How Deliberation Makes Better Citizens: The Danish Deliberative Poll on the Euro.” European Journal OfPolitical Research 46 (4): 531–556.

- Anduiza, E., M. Guinjoan, and G. Rico. 2019. “Populism, Participation, and Political Equality.” European Political Science Review 11 (1): 109–124.

- Baiocchi, G., and E. Ganuza. 2014. “Participatory Budgeting as if Emancipation Mattered.” Politics & Society 42 (1): 29–50.

- Bartha, A., Z. Boda, and D. Szikra. 2020. “When Populist Leaders Govern: Conceptualising Populism in Policy Making.” Politics and Governance 8 (3): 71–81.

- Batory, A. 2016. “‘Populists in Government? Hungary’s “System of National Cooperation”’.” Democratization 23 (2): 283–303.

- Batory, A., and S. Svensson. 2019. “The use and Abuse of Participatory Governance by Populist Governments.” Policy & Politics 47 (2): 227–244.

- Bennett, W. L., A. Segerberg, and C. B. Knüpfer. 2017. “The Democratic Interface: Technology, Political Organization, and Diverging Patterns of Electoral Representation.” Information, Communication & Society 28 (11): 1655–1680.

- Biezen, I. van, and D. R. Piccio. 2013. “Shaping Intra-Party Democracy: On the Legal Regulation of Internal Party Organizations.” In The Challenges of Intra-Party Democracy, edited by W. P. Cross, and R. S. Katz, 27–48. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bogaards, M. 2018. “De-democratization in Hungary: Diffusely Defective Democracy.” Democratization. Taylor & Francis 25 (8): 1481–1499.

- Borge, R., and E. Santamarina. 2016. “From Protest to Political Parties: Online Deliberation in New Parties in Spain.” Media Studies 7 (14): 104–122.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Caluwaerts, D., and M. Reuchamps. 2016. “Generating Democratic Legitimacy Through Deliberative Innovations: The Role of Embeddedness and Disruptiveness.” Representation. Taylor & Francis 52 (1): 13–27.

- Canovan, M. 1999. “Trust the People! Populism and the Two Faces of Democracy.” Political Studies 47 (1): 2–16.

- Chambers, S. 2003. “Deliberative Democratic Theory.” Annual Review of Political Science 6 (1): 307–326.

- Chaney, P. 2006. “‘Critical Mass, Deliberation and the Substantive Representation of Women: Evidence from the UK’s Devolution Programme’.” Political Studies 54 (4): 691–714.

- Cooke, M. 2000. “Five Arguments for Deliberative Democracy.” Political Studies 48 (5): 947–969.

- Croissant, A., and P. Chambers. 2010. “Unravelling Intra-Party Democracy in Thailand.” Asian Journal of Political Science 18 (2): 195–223.

- Dahlberg, S., J. Linde, and S. Holmberg. 2015. “Democratic Discontent in Old and New Democracies: Assessing the Importance of Democratic Input and Governmental Output.” Political Studies 63 (S1): 18–37.

- Davidson, S., and A. Stark. 2011. “Institutionalising Public Deliberation: Insights from the Scottish Parliament.” British Politics 6 (2): 155–186.

- Dryzek, J. S. 2004. “Legitimacy and Economy in Deliberative Democracy.” Contemporary Political Theory: A Reader 29 (5): 242–260.

- Dryzek, J. S., et al. 2019. “The Crisis of Democracy and the Science of Deliberation.” Science 363 (6432): 1144–1146.

- Dutwin, D. 2003. “The Character of Deliberation: Equality, Argument, and the Formation of Public Opinion.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 15 (3): 239–264.

- Dzur, A. W., and C. M. Hendriks. 2018. “Thick Populism: Democracy-Enhancing Popular Participation.” Policy Studies. Taylor & Francis 39 (3): 334–351.

- Eerola, A., and M. Reuchamps. 2016. “Constitutional Modernisation and Deliberative Democracy: A Political Science Assessment of Four Cases.” Revue Interdisciplinaire D’études Juridiques 77 (2): 319–336.

- Enyedi, Z. 2016a. “Paternalist Populism and Illiberal Elitism in Central Europe.” Journal of Political Ideologies 21 (1): 9–25.

- Enyedi, Z. 2016b. “Populist Polarization and Party System Institutionalization: The Role of Party Politics in De-Democratization.” Problems of Post-Communism 63 (4): 210–220.

- Fishkin, J. S. 2009. When the People Speak. Deliberative Democracy & Public Consultation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fishkin, J. S., et al. 2010. “Deliberative Democracy in an Unlikely Place: Deliberative Polling in China.” British Journal of Political Science 40 (2): 435–448.

- Fishkin, J. S., and R. C. Luskin. 2005. “Experimenting with a Democratic Ideal: Deliberative Polling and Public Opinion.” Acta Politica 40 (3): 284–298.

- Fishkin, J. S., R. C. Luskin, and R. Jowell. 2000. “Deliberative Polling and Public Consultation.” Parliamentary Affairs 53 (4): 657–666.

- Flinders, M., and D. Curry. 2008. “Deliberative Democracy, Elite Politics and Electoral Reform.” Policy Studies 29 (4): 371–392.

- Fournier, P., et al. 2011. When Citizens Decide: Lessons from Citizen Assemblies on Electoral Reform. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gad, N. 2020. “A “new Political Culture”: the Challenges of Deliberation in Alternativet.” European Political Science 19 (2): 190–199.

- Gherghina, S. 2017. “Direct Democracy and Subjective Regime Legitimacy in Europe.” Democratization 24 (4): 613–631.

- Gherghina, S. 2019a. “Hijacked Direct Democracy: The Instrumental Use of Referendums in Romania.” East European Politics and Societies 33 (3): 778–797.

- Gherghina, S. 2019b. “How Political Parties use Referendums: An Analytical Framework.” East European Politics and Societies 33 (3): 677–690.

- Gherghina, S., and V. Jacquet. 2021. “How and why Political Parties use Deliberation: A Framework for Analysis.” Acta Politica. Forthcomin.

- Gherghina, S., S. Soare, and V. Jacquet. 2020. “Deliberative Democracy and Political Parties: Functions and Consequences.” European Political Science 19 (2): 200–211.

- Gherghina, S., and V. Stoiciu. 2020. “Selecting Candidates Through Deliberation: The Effects for Demos in Romania.” European Political Science 19 (2): 171–180.

- Hartliński, M. 2019. “The Effect of Political Parties on Nationwide Referendums in Poland After 1989.” East European Politics and Societies 33 (3): 733–754.

- He, B., and M. E. Warren. 2011. “Authoritarian Deliberation: The Deliberative Turn in Chinese Political Development.” Perspectives on Politics 9 (2): 269–289.

- Herman, L. E. 2016. “Re-evaluating the Post-Communist Success Story: Party Elite Loyalty, Citizen Mobilization and the Erosion of Hungarian Democracy.” European Political Science Review 8 (2): 251–284.

- Hollander, S. 2019. The Politics of Referendum use in European Democracies. Nijmegen: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Illonszki, G., and R. Várnagy. 2014. “Stable Leadership in the Context of Party Change: The Hungarian Case.” In The Selection of Political Party Leaders in Contemporary Parliamentary Democracies: A Comparative Study, edited by J.-B. Pilet, and W. P. Cross, 156–171. London: Routledge.

- Jacquet, V., and R. Van Der Does. 2020. “The Consequences of Deliberative Minipublics : Systematic Overview, Conceptual Gaps, and New Directions.” Representation. Taylor & Francis 0 (0): 1–11.

- Jiang, M. 2010. “Authoritarian Deliberation on Chinese Internet.” Electronic Journal of Communication 20 (3&4): 1–22.

- Katz, R. S., and P. Mair. 1993. “The Evolution of Party Organizations in Europe: The Three Faces of Party Organization.” The American Review of Politics 14 (Winter): 593–617.

- Körösényi, A., G. Illés, and A. Gyulai. 2020. The Orbán Regime: Plebiscitary Leader Democracy in the Making, Routledge advances in European politics. London: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Lehrer, R. 2012. “Intra-Party Democracy and Party Responsiveness.” West European Politics 35 (6): 1295–1319.

- Levi, M., and L. Stoker. 2000. “Political Trust and Trustworthiness.” Annual Review of Political Science 3 (1): 475–507.

- Linde, J., and S. Holmberg. 2013. Dissatisfied Democrats: A Matter of Representation or Performance? 8. Gothenburg.

- Loxbo, K. 2013. “The Fate of Intra-Party Democracy: Leadership Autonomy and Activist Influence in the Mass Party and the Cartel Party.” Party Politics 19 (4): 537–554.

- Meghallgattuk Magyarországot, M. 2005. Nemzeti Konzultáció. Budapest: Nemzeti Konzultációért Alapítvány.

- Mudde, C. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Nemčok, M., and P. Spáč. 2019. “Referendum as a Party Tool: The Case of Slovakia.” East European Politics and Societies 33 (3): 755–777.

- Norris, P. 1999. Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Oross, D., and P. Tap. 2021. “Moving Online: Political Parties and the Internal use of Digital Tools in Hungary.” European Societies. (online first).

- Pascolo, L. 2020. “Do Political Parties Support Participatory Democracy? A Comparative Analysis of Party Manifestos in Belgium.” ConstDelib Working Paper Series 1 (9): 1–26.

- Paxon, M. 2020. Agonistic Democracy. Rethinking Political Institutions in Pluralist Times. London: Routledge.

- Pállinger, Z. T. 2016. The Uses of Direct Democracy in Hungary. Paper presented at the ECPR 2016 Generals Conference.

- Phelan, C. 2006. “Public Trust and Government Betrayal.” Journal of Economic Theory 130 (1): 27–43.

- Pirro, A. L. P. 2015. “The Populist Radical Right in the Political Process: Assessing Party Impact in Central and Eastern Europe.” In Transforming the Transformation? The East European Radical Right in the Political Process, edited by M. Minkenberg, 80–105. London: Routledge.

- Pirro, A. L. P., and M. Portos. 2021. “Populism Between Voting and non-Electoral Participation.” West European Politics. Routledge 44 (3): 558–584.

- Reuchamps, M., and J. Suiter. 2016. Constitutional Deliberative Democracy in Europe. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Scherz, A. 2019. “Tying Legitimacy to Political Power: Graded Legitimacy Standards for International Institutions.” European Journal of Political Theory 0 (0): 1–23.

- Scoggins, B. 2020. “Identity Politics or Economics? Explaining Voter Support for Hungary’s Illiberal FIDESZ:.” East European Politics and Societies, and Cultures. (online first).

- Setälä, M., and G. Smith. 2018. “Mini-Publics and Deliberative Democracy.” In The Oxford Handbook of Deliberative Democracy, edited by A. Bächtiger, J. S. Dryzek, J. Mansbridge, and M. E. Warren, 300–314. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sharon, A. 2019. “Populism and Democracy: The Challenge for Deliberative Democracy.” European Journal of Philosophy 27 (2): 359–376.

- Stoychev, S. P., and G. Tomova. 2019. “Campaigning Outside the Campaign: Political Parties and Referendums in Bulgaria.” East European Politics and Societies and Cultures 33 (3): 691–704.

- Suteu, S. 2019. “The Populist Turn in Central and Eastern Europe: Is Deliberative Democracy Part of the Solution?” European Constitutional Law Review 15 (3): 488–518.

- Teorell, J. 1999. “A Deliberative Defence of Intra-Party Democracy.” Party Politics 5 (3): 363–382.

- van Eeden, P. 2019. “‘Discover, Instrumentalize, Monopolize: Fidesz’s Three-Step Blueprint for a Populist Take-Over of Referendums’.” East European Politics and Societies 33 (3): 705–732.

- Vittori, D. 2017. “Podemos and the Five Stars Movement: Divergent Trajectories in a Similar Crisis.” Constellations (oxford, England) 24 (3): 324–338.

- Vittori, D. 2019. “‘Membership and Members’ Participation in new Digital Parties: Bring Back the People?’.” Comparative European Politics 18 (4): 609–629.

- Vodová, P., and P. Voda. 2020. “The Effects of Deliberation in Czech Pirate Party: the Case of Coalition Formation in Brno (2018).” European Political Science 19 (2): 181–189.

- Wampler, B. 2008. “When Does Participatory Democracy Deepen the Quality of Democracy? Brazil Lessons from.” Comparative Politics 41 (1): 61–81.

- Warren, M. E., and H. Pearse. 2008. Designing Deliberative Democracy: The British Columbia Citizens’ Assembly. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Whiteley, P., et al. 2016. “Why do Voters Lose Trust in Governments? Public Perceptions of Government Honesty and Trustworthiness in Britain 2000-2013.” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 18 (1): 234–254.

- Wolkenstein, F. 2016. “A Deliberative Model of Intra-Party Democracy.” Journal of Political Philosophy 24 (3): 297–320.

- Wolkenstein, F. 2018. “Intra-party Democracy Beyond Aggregation.” Party Politics 24 (4): 323–334.

- Zaslove, A., et al. 2021. “‘Power to the People? Populism, Democracy, and Political Participation: a Citizen’s Perspective’.” West European Politics. Routledge 44 (4): 727–751.

- Zulianello, M. 2020. “Varieties of Populist Parties and Party Systems in Europe: From State-of-the-Art to the Application of a Novel Classification Scheme to 66 Parties in 33 Countries.” Government and Opposition 55: 327–347.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Topics and questions of National Consultations.

Appendix 2. The list of interviews used in the analysis (in chronological order).