Abstract

Over the past decade, Portugal became one of the countries most committed to involving citizens in public decision-making, using ‘open door' approaches based on participants’ self-selection. To what extent are such practices concerned with inclusiveness? The article is built on the first stage of a two-fold collaborative research to map strategies shaped by Portuguese municipalities for coping with underrepresented actors in participatory processes. The exploratory analysis – funded by the Network of Participatory Municipalities of Portugal (RAP) - reveals common patterns: (1) pursuing inclusion of underrepresented actors is not a policy for fostering a high diversification of actors in spaces of social dialogue, but just a tool for caring of marginalised groups; (2) ‘co-design’ of inclusionary policies with the targeted social actors is not a common method; (3) there is limited coordination between different policy sectors of each local authority; (4) the majority of 58 participation web-portals are imagined as mere instrumental spaces for organising their democratic innovations, but under-estimate their potential as ‘mirrors’ of the community and of the different underrepresented groups targeted. The dialogue opened among RAP members on the two surveys reveals a potential for imagining and co-designing shared solutions through the next stages of the collaborative research.

Fundamentally, inclusion is the principle that we are all entitled to participate fully in all aspects of society; that we all have something to contribute. (…) It is the right of the individual and the responsibility of society as a whole (…). Inclusion is about valued recognition, meaningful engagement and enabling social policy (Jones Citation2010, 58–59).

1. Introduction

Vast amount of literature – both academic and grey (Auger Citation1975) – has been dealing with the definition and measurement of ‘inclusion’ through public policies, along with the pivotal role that committed public institutions have had in the promotion of citizens’ participation as a tool to make inclusion effective in every area of life. Participation, in fact, offers an opportunity to bridge non-discriminatory attitudes of individuals and groups towards people with specificities which they feel are different from their own, with the facilitation of good living conditions for these same people (Jones Citation2010), thus favouring ‘the recognition of self in other, and other in self’ (Habermas Citation1987, 45).

Nevertheless, asymmetries exist between the vast literature on ‘inclusion through participation’ and the analysis of ‘inclusion within participation’. The latter tends to focus specifically on the notion of inclusionary tools and practices, focussing on ‘inclusiveness’ as the capacity of participatory processes to take charge of the inclusive dimension in the different phases and stages which structure democratic innovations (Smith Citation2009; Sorice Citation2019). This is especially true for participatory processes ‘by invitation’ (Blas and Ibarra Citation2006), which are promoted by representative institutions as a concession to their fellow citizens. In fact, in relation to such democratic innovations, institutions have a double responsibility: (1) to guarantee that they act as spaces which promote inclusiveness in public policies, and; (2) to guarantee that their architecture incorporates all the necessary features which can prevent them from being felt by some groups or individuals as new spaces of exclusion, unable of compensating the ‘unfulfilled promises of democracy’ (Bobbio Citation1987) or, even, capable of aggravating them.

In this perspective, the literature which deals with institutional-based participatory processes, tends to incorporate perspectives related to the ‘duty’ of organisers (Rioux, Basser, and Jones Citation2010; Ganuza and Francés Citation2012b) to guarantee an inclusionary dimension, especially when dealing with the subcategory of ‘deliberative experiments’, whose organisational design considers the inclusiveness of multiple and diverse voices as a central priority.

Few reflections, up until now, have tried to read these topics from the standpoint of those who – in public institutions – carry the task and responsibility of shaping the ‘participatory imperative’ (Sintomer and Allegretti Citation2009), taking into account the ‘ideology in practice’ of inclusion (Flem and Keller Citation2000). How is inclusiveness viewed by them? Is it intended as a capacity of incorporating and valuing diversity in participatory processes? If so, is inclusiveness felt as valuable and a priority for those who organise participatory processes in public institutions? Is it embedded into participatory practices, and if so, in which of them? Does a clear conceptualisation about it exist, and is it shared within the broader institutional environment in which they work in? Or is ‘inclusion’ mainly a rhetoric reference, or even a ‘tyranny’ (Cooke and Kothari Citation2001) that they feel compelled to couple up with participation as an ‘inseparable combination’ that cannot be split?

1.1. Relevance of the proposed standpoint and the context of analysis

This article intends to offer a contribution to start filling the above-mentioned gap, taking advantage of a collaborative action-research among Portuguese cities, which started in August 2020, within the Network of Participatory Local Authorities of Portugal (RAP). The latter is an association devoted to mutual learning between 62 local institutions strongly committed to experimenting with different tools of citizens participation. RAP took shape within the Portugal Participa project, co-funded by the Gulbenkian Foundation, in 2014–2016. Its origins are rooted in a longer process, started with previous projects coordinated by the NGO In-Loco and the Centre for Social Studies of Coimbra UniversityFootnote1 for supporting local authorities in acquiring skills for structuring and autonomously managing substantive participatory processes at local level (Falanga and Ferrão Citation2021). RAP represents the capacity of Portuguese local authorities of going beyond the dependence from the initiatives and the technical capacities of their long-time consultants, and showing an autonomous resourcefulness in shaping innovative arenas for incentivising civic participation in the territories of member cities. This still-informal organisation was able to provide continuity to the externally-funded initiative of Portugal Participa project and to build and acquire entrepreneurship for designing an independent strategy of survival and expansion based on self-funding and shared responsibility (Falanga and Ferrão Citation2021). Since then, RAP has been actively lobbying for mainstreaming participatory devices in the country, at a local, regional and national levels of the State (Falanga and Lüchmann Citation2019).

The Council of Ministers Resolution n. 130 – issued in September 2021 for regulating the National Participatory Budgeting (OPP) and the new Participatory Budgeting dedicated to Civil Servants (AP Participa)Footnote2 – represents a visible output of RAP main activity, as it owes much to local participatory experiments and to the tight collaboration between the Agency for Administrative Modernization (AMA), several ministerial offices and a committed group of local authorities. The same decree also reveals the limits of RAP lobbying capacity, provided that it creates a brand-new opportunity of multilevel governance for participatory processes in Portugal, but it does not create any system of incentives, monitoring and support for the deliberative and participatory practices. One could point out the same absence in the decentralisation processes which took place in the last three years in thematic sectors as education, planning, social assistance or health (Teles Citation2021), despite the latter topic has been the object of a bottom-up conquer, which introduced some obligations for all public authorities in relation to listening citizens while structuring policies of prevention and care.Footnote3 An aspect which is fundamental in the construction of RAP image is the commitment in overcoming any suspect of party-based partisanship; therefore, the competing lists running for the election of the RAP board of directors usually have tended to gather mayors belonging to a diverse range of parties, and it would be difficult today to identify specificities of the participatory processes experienced by RAP members strictly linked to party-based streamlines and directives (Dias Citation2018). Somehow, the political/ideological orientation of RAP members has played as an almost insignificant variable in the promotion of a growing variety of well-conceived and highly-committed participatory processes.

RAP can be identified as a ‘community of practices’ (Wenger Citation1998; Schweitzer, Howard, and Doran Citation2008), that learn and change through the practices that it enact(s), so that ‘as long as people are engaged in practices, community is being created, and the character of the practices defines the nature of the community’ (Quick and Feldman Citation2011, 273). In fact, it is a group with visible membership (Brown and Duguid Citation1991; Bechky Citation2003; Yanow Citation2003) and a strategy which enhances internal cohesion and knowledge management (Dawes, Cresswell, and Pardo Citation2009) as well as organisational capacity building (Snyder and Briggs Citation2004). Its efforts focus on creating contexts in which public servants, elected officials and observers’ organisations use networking among their participatory practices to experiment with new ways of learning about larger issues, such as governance and sustainability (Dotti Citation2018; Haupt Citation2018; Vinke-de Kruijf and Pahl-Wostl Citation2016; Fünfgeld Citation2015; Gilardi and Radaelli Citation2012; Tjandradewi and Marcotullio Citation2009; Kemp and Weehuizen Citation2005).

To understand why RAP emerged as a significant actor in the consolidation and diffusion of participatory practices in Portugal, it is worth stressing that, during the past decade, the country has abruptly emerged as one of the most committed countries globally to involve citizens in public decision-making (Dias Citation2018; Alves and Allegretti Citation2012), particularly with regards to youth policies and Participatory Budgeting (PB). In this frame, RAP has been an important tool in multiplying dissemination and cross-fertilisation in the field of participatory practices. The last census of Participatory Budgeting (Dias, Enríquez, and Júlio Citation2019) revealed that there are almost 1686 active experiences of this type in Portugal (36% of the entire European PB critical mass). Out of them, 124 take place in local administrations (LAs), 2 in regional governments, 3 are central government experiments (Falanga Citation2018). The rest, mostly take place in schools, due to national legislation issued by the Ministry of Education. In 2017, this legislation made the implementation of PBs mandatory in all public high schools (Dias, Enríquez, and Júlio Citation2019, 47). Other than this exception, Portugal's legal framework neither provides many obligations nor incentives to participatory processes (Allegretti and de Carvalho Citation2015). Thus, majority of experiences take place at a ‘policy level’ and are guided by the autonomous goodwill of different elected governments (Allegretti Citation2018), which feel motivated to fuel administrative practices which directly involve citizens – and organise stakeholders – in the construction of some public decisions, on different thematic areas (housing, green areas, mobility, culture, civil protection, urban planning, etc.).

Provided the absence of institutional, legal and financial incentives to the multiplication and consolidation of participatory processes, one could legitimately wonder what has been the main driver for political institutions to invest in such mainstreaming of participatory practices in Portugal. Literature has mainly converged (Cabral Citation2014) in stressing that the main hypothesis which could explain this growth can be referred to the need of contrasting, through the offer of committed participatory processes, the growing mistrust of Portuguese citizens in political institutions (Dias Citation2018; Viegas, Belchior, and Seiceira Citation2011; Silva, Cabral, and Saraiva Citation2008; Cabral, Lobo, and Feijó Citation2009a, Citation2009b). The latter is clearly reflected in the declining trends of electoral turnouts in the last decade,Footnote4 which the multiplication of participatory processes was not able to stop, even in municipalities where very large audiences are involved in arenas of civic engagement and several participants who declare that never voted continue to be active and committed (OPTAR Citation2013). In Portugal, the growth of participatory experiments, which took place amid impactful changes due to the contradictory trajectory of decentralisation of State competences (Mendes Citation2016),Footnote5 goes hand-in-hand with a generational shift of local authorities (Teles Citation2021),Footnote6 which brought new perspectives on how to involve citizens more effectively in public affairs, and on how to mainstream a new style of governance more carefully attentive to engage in decision-shaping also those who barely feel represented by aggregate movements and civic organisations. These phenomena coupled with a growing consideration in the public discourse for Art. 2 of the Portuguese Constitution, which states that ‘deepening participatory democracy’ is among the central duties of the State of the Rules of Law, and not only a mere instrument to improve its public policies. Despite such a constitutional framework, few regulatory measures were in practice undertaken by national authorities to incentivise the creation of a participatory culture and initiative was mainly let to local officers. Moreover, when attempts to ‘force’ an increase of participatory requirements of local policies have been pursued by central authorities, the same municipalities obtained from the Supreme Court the abrogation of the most binding measures (as it was the case of the Law 8/2009 on Municipal Youth Council).Footnote7

Despite this situation, in the last decade Portugal has experienced a substantial growth in the range and quality of different participatory devices used at local level, which was partially fuelled by the visibility acquired by the main sound practices on the national and local media as in the academic discourse and among the members of international networks related to good governance and democratic innovation. The creation of RAP network – which promotes interchanges among: political officials, experts, technical personnel and civil servants in charge of participatory processes – could be seen as an important catalyst for such diversification and maturation of participatory experiences. Among other achievements, RAP has created a Best Practice Award and issued guidelines to improve the quality of participatory processes, such as the ‘Charter for Quality of Participatory Budgets in Portugal’ (2017), which gradually oriented the construction of a LAs’ self-evaluation system to measure and monitor the progress of their processes. But, up until 2020, RAP had never promoted specific initiatives about inclusiveness in participation.

In 2020, the COVID-19 emergency paralysed many institutionalised participatory processes (Dias Citation2020); so, RAP took initiatives to dynamise the national debate on participation, which included: webinars with similar networks to other countries, and some surveys among civil servants and politicians involved in organising participatory processes, which could provide public authorities with ideas to rethink their practices of social dialogue (Allegretti Citation2020; Falanga and Allegretti Citation2021). Strategies for wider inclusiveness in participation have become a central topic, due to different pressures – especially those exerted by social movements in central sectors such as housing (Mendes Citation2020) – and the awareness of new exclusions that have emerged from two prolonged lockdowns and of those which will arise from the forthcoming economic crisis.

This article uses the results of two surveys among RAP members as its main source of data. The first is dedicated to the inclusive image of local websites which support participation, and the second to strategies for inclusion of underrepresented citizens. The author has contributed to shape the initiatives, whose results have been recently published in Serrano et al. (Citation2021). The two intertwined surveys have been presented by RAP as ‘collaborative action-research’ (RAP Citation2020a), as they were imagined as the first step in structuring a dialogue among municipalities. This dialogue will include – during 2021 and the start of 2022 – a series of collective discussions of data with the members of RAP, as well as training sessions, analyses of national and international best practices and further inquiries to expand the debate on how to better articulate participation and inclusion.

The umbrella-title that unifies the two surveys (‘The inclusion of underrepresented groups in participatory processes’) was inspired by COST Action n. 17135,Footnote8 and aimed to maintain definitions within a wider scope, while clearly focussing on the inside-out perspective of institutionalised participatory experiences. Despite this, the two initiatives are quite different. In fact, the one on the websites was conducted as an ‘external observation’ by a group of professionals who permanently support RAP in its activities (see section 3). It was added to the other inquiry – proposed and structured by the same group of professionals – when it became clear that as only a restricted group of municipalities was going to answer it, thus undermining its degree of representativeness and generalisability. Consequently, the two interlinked studies cannot be considered a proper phase of an action-research, as defined in literature (McNiff Citation2013; Kaneklin, Piccardo, and Scaratti Citation2010; Minardi and Cifiello Citation2005), but a preliminary step which can offer some evidence, interpretations and ‘provocations’ to later start a larger collaborative research project with and among RAP members. However, this further collective use makes them meaningful, as the interpretation of their results can pave the way for the future involvement of new municipalities and the consequent growth of collected data in terms of statistical significance and interpretative potential.

The exploratory analysis of the preliminary step of RAP collaborative research wants to offer a contribution for its further phases to be conducted in the next months, having the main goal to read what are the main orientations of respondents when approaching the topic of inclusiveness, and what are the main aspects and pattern emerging from the main literature related to the field, which appear as ‘missing dots’ from the work of the analysed cities.

With regards to the article's structure, the next section (part 2) will try to insert the two above-mentioned surveys promoted by RAP into a larger debate on inclusiveness in participation; section 3 will focus on better explaining the origin, scope, methodology and main limits of empirical work; sections 4–5 will refer to the deployment of the surveys’ results, offering space for interpretative hypotheses, while section 6 will link the main conclusions of this exploratory phase with further steps of collaborative initiative promoted by RAP, which is due to develop during 2021 and 2022 (see also: Falanga and Allegretti Citation2021).

2. The dialogue between inclusion and participation: some ambiguities emerging from literature

2.1. About diversity and fairness

Literature unanimously considers that valuing a diversity of perspectives is – per se – a thermometer of a well-functioning democracy, and an enriching factor in grounding any debate on policies and projects, as well as on the effectiveness of different public and market institutions (Hunt, Layton, and Prince Citation2015). Thus, participatory processes would have, as one of their primary functions, to contribute to guarantee it. As ethical philosophy would underline, valuing the plurality and diversity of voices is often a motivation used to justify deontological participatory processes – as pluralism is considered an inherent dimension of full democratic practices – but is not enough to sustain consequentialist practices, marked by clear goals (such as transparency, redistribution and social justice, among others) which must be coherently translated into action forging their targeted design and the evaluation of their efficacy and success. Sometimes, even the extents to which consequentialist participatory processes aimed at better inclusion are capable to embed adequate practices to support the active presence of a large diversity of participants, it remains unclear. Such practices often interpret ‘inclusiveness’ as a measure specifically tailored to involve marginalised and vulnerable groups, rather than as a principle that continuously attracts new and diverse social actors, independently from their socioeconomic or cultural specificities and their degree of social activism.

Positions – both in literature as in polity practices – differ substantially it comes to imagine how diversity can be made present and visible in participatory processes. Differences refer to the use of specific methodologies, rules and settings, which can guarantee that a multiplicity of different participants translates into equality of voices and fulfil the epistemological imperative to make expert knowledge dialogue with ‘lay’ ones, empowering citizens to influence critical collective decisions ‘at a time when the weight of science and technology is stronger than ever’ (Sintomer and Ganuza Citation2011, 215).

Some authors (Smith Citation2009; Saward Citation2003) have proposed to implement analytical frameworks which could compare different types of democratic innovations based on the manner and extent to which they manage to deliver complementary ‘democratic goods’, among which ‘inclusiveness’ represent a central one, together with others interlinked principles (such as popular control, considered judgement and transparency). As Smith underlines (Citation2009, 15), inclusiveness ‘turns our attention to the way in which political equality is realised in at least two aspects of participation: presence and voice’. In this frame, authors such as Giusti (Citation1995) have been describing the story of institutionalised participatory practices as an alternance of asymmetric moments in which the capacity of citizens to impact policy-making was exercised indirectly (via forms of advocacy by representation) or directly (attracting and empowering them in first person, through maieutic techniques which can make every person feel at ease in contributing to a wide collective public dialogue).

As stated by Gould (Citation1996, 171) finding diverse concrete methods in which differences would be adequately recognised and effectively considered in the public domain – as a starting point for building fairer and more equal processes of civic engagement – remain ‘undeveloped and problematic’. In fact, complex and sensitive questions must be addressed, such as ‘what is the normative rationale for this recognition? What differences ought to be recognised, and why these rather than others? Which differences would it be pernicious to recognise?’. Paraphrasing the title of a famous Scottish-based research (Lightbody et al. Citation2017): which voices are harder to reach and which are easier to ignore?

As remarked by all theorists of difference, a tight relation exists between the presence of specific groups in a polity process and the direction of decisions. Thus, being present is an undeniable need and the first step in granting a society marked by freedom of expression. The notion of ‘powerlessness’ by Iris Marion Young (Citation2011) – as happened decades before with Sherry Arnstein (Citation1969) – coincides with the absence of certain social groups in spaces where decisions are made, that affect the conditions of their lives and actions. Obviously, the impact on polities of each different actor can never be given for grant, provided that it is moderated by other factors as rules for decision-taking and the fairness of deliberative spaces (Benhabib and Meyer Citation1996; Vieten et al. Citation2014). In general, the concrete risks of uneven participation – a persistent concern across various modes of political and civic participation – raise key-questions about how to ‘constitute the demos’ (Goodin Citation2007) of each process, and how democratic innovations ‘can buck the trend and institutionalise effective incentives for participation by citizens from across different social groups’ (Smith Citation2009, 24). Evidence from recent processes demonstrates that good faith of organisers to find outreach and organisational formulas to maximise the involvement of certain specific groups is not enough to fight the risk of their under-representation, as it is often the consequence of several diverse and intertwined phenomena (Miscoiu and Gherghina Citation2021; Harris Citation2021), included the risk of dominance of some participants on others during mixed deliberation events (Strandberg et al. Citation2021).

If we imagine that any restriction would undermine fairness – i.e. the equal right and opportunity to participate – one could imagine that inclusiveness would be best served through institutions that are ‘open to all’ and to the different repertoires of collective action. However, a more careful weighting of difference theorists’ arguments (Phillips Citation1995, 13) may convince one that randomised, stratified or semi-random forms of selection, as well as mixed forms that include one or more of these methods, better serve the goal of including diversity. In fact, self-selection tends to simply replicate existing inequalities, and presence (or absence) of specific interests/conditions can have a significant impact on the nature of decisions, especially for those which concern them.

In light of this, authors as Smith (Citation2009) consider the fairness of selection rules and procedures as a central element for granting diversity of voices, considering that ‘deliberative designs’ (especially the recent ones, which incorporate adjustments to the selection procedures to better represent minorities) more carefully balance the democratic good of considered judgement and that of inclusiveness. Lijphart (Citation1997) went further, remarking that such designs explicitly face the democracy's unresolved dilemma of unequal participation, derived from the fact that ‘in the real world some people and groups have significantly greater ability to use democratic processes for their own ends’ (Young Citation2000, 17) and this is strongly positively correlated to income, wealth, education (Pattie, Seyd, and Whiteley Citation2004; Verba, Nie, and Kim Citation1978) and other ‘positional differences’. Under such a perspective, deliberative methodologies more explicitly struggle against the unfair consequences of ‘undeserved inequalities’ (Rawls Citation1999, 86), as they face – through different modalities of affirmative action – those asymmetries which undermine the equality of people's opportunities to expose their vision and needs, and incise in polity changes which can improve their quality of life. Nevertheless, ‘deliberative settings’ have been severely criticised by others, such as Young (Citation2001), for whom democratic inclusion meant sensitivity to the situated and historical contexts that people are born in, but also to the different forms of expressions which, concretely, struggle in a frame of ‘shared responsibility for justice’ (Citation2011). In her view, those settings are almost artificially created outside the multiple forms of social fights that include networks and collective intermediary bodies. In a convergent perspective, other authors state that, if participation is a matter of guaranteeing a differentiation not only of interests, but also of narratives and cognitive/epistemic diversities (Ganuza and Francés Citation2012b), it must be conceptualised as an embodied, multimodal process in which language together with bodily senses (vision, hearing, touch, smell and taste) contribute ‘to a phenomenon being recognised (as shared)’ (Raudaskoski Citation2013, 103).

The existence of such different positions on how to concretely guarantee and maximise inclusiveness of (more or less formalised) participatory practices, does not undermine the convergences existing in literature on the fact that the abstract universality and individualism of liberal positions on justice (Barry Citation1973) tend to under-estimate differences other than those of political opinion, overriding and assigning them to the private sphere (Gould Citation1996, 171). Consequently, a diffuse support has grown around different forms of positive discrimination intended to favour the marginalised and oppressed who are disadvantaged in society and, thus, ‘deserve more than others’ (Maboloc Citation2015, 19). These interventions target different persons through different measures, as attention to inclusiveness cannot limit its concerns to the formal characteristics of the selection mechanisms of a participatory arena. For example, they must consider how – in practice – institutional inducements motivate citizen engagement from across different cultural and social groups (Talukder and Pilet Citation2021): so, they must encompass the agenda setting, such as choosing the political salience of the topic (and its capacity to offer a clear and fast pay-off to participants) can affect the presence of a different range of participants. The latter differ in their political skills, confidence and political efficacy, i.e. the feeling that ‘one could have an impact on collective actions if one chose to do so’ (Warren Citation2001, 71). Therefore, leveraging the inclusion of diverse citizens, does not only require attention to the conception of different devices used for social dialogue, but also to the way in which each of such devices is tied to the institutions, in order to grant impact and implementation to the process’ outputs and to the social oversight of citizens on them. Some participatory technologies, such as participatory budgeting, are – by default – clearer than others in this respect (Cabannes and Delgado Citation2015). Finally, the relation between the arenas of social dialogue and the urban spaces where they take place becomes also important. For example, various techniques of ‘outreach’ can try to bring participation to where people live, avoiding risks of institutional self – referentiality; because, indeed, is in the city space that we can discover and experience the restlessness of otherness and uncommonness (Sennett Citation2012).

Authors that engaged in analysing vastly different designs of democratic innovations without pre-defined preferences of architectural models (as Trettel Citation2020; Sorice Citation2019 or Fung and Wright Citation2002), tend to recognise that no simple relationship between them and the reinforcement of differential rates of engagement across social groups exists. At the same time ‘realising inclusiveness is clearly tied to the incentive structure embedded within institutional designs’ (Smith Citation2009, 169), as well as to the combination with a fair offer of other democratic goods – such as transparency or popular control – which can affect the interest and/or the continuity of people participating.

2.2. The emergence of four meaningful questions

In view of the debates outlined so far, one can imagine a first level of interest in analysing the preliminary results of the two RAP surveys on underrepresented group in participatory processes, which is related to the need of understanding if inclusion strategies conceived by the responding cities are aimed: (1) to reinforce the diversity tout court of social actors whose voice is heard by the local institutions (independently from the conditions of marginalisation of the individuals and groups, which are targeted by each democratic innovation), or – conversely – (2) they are more targeted to reverse some patent or more invisible exclusions which characterise the specific socio-territorial milieu and requires to overcome the limits of the ‘majority normativity’ (Young Citation2000) and shape affirmative actions for the sake of those which are oppressed by injustice or ‘vulnerated’ in different ways (Fontes and Martins Citation2015) by societal rules, the market and the procedures of representative democracy. Actually, the specific survey on the participation websites of the RAP member cities seem particularly interesting, as far as it cast doubts on their capacity to create a space for a bi-directional dialogue with their citizens, in which structures and visual/textual imaginary they could feel represented, according to an idea of participation in permanent tense relation with the notions of ‘redistribution’ and ‘recognition’ at the centre of the dialogue between Fraser and Honneth (Citation2002; see also Hansson et al. Citation2013).

A second interesting question that arises from the RAP surveys may refer to the main typologies of actors targeted by the inclusionary actions, and to the families of methodologies adopted. As a matter of fact, the methodological part of the question (which has been specifically posed by the surveys) is partially answered analysing the general context of Portugal. In fact, the national Constitution (Art.2) has contributed to shape a horizon of ‘participatory democracy’, which is traditionally based on processes referred to as ‘open door’ methods, allowing citizens to step in and join in any phase. Thus, it is neither surprising that, in Portugal, any tradition of ‘mini-publics’ or other deliberative experiences developed,Footnote9 nor that ‘sortition’ and ‘random selection’ are concepts that – up till now – have not been at the centre of meaningful political proposals for involving citizens in public affairs or policy-shaping. The few occasions in which such proposals have emerged, were in mainly academic-led document directed to the policy-making community (Allegretti et al. Citation2021).Footnote10 Furthermore, when some municipality tried to use random selection, it was blocked by bureaucratic obstacles posed by the Privacy Protection Authority.Footnote11 In any case, the main focus of the majority of participatory processes has been on involving citizens as individuals because ‘our country has high levels of social mistrust, and the idea of someone representing me is not that attractive, and possibly explains why PB is so successful and spread’.Footnote12 Nevertheless, the trend towards ‘disintermediation’ of participatory arenas (Wellman Citation2001 and Haythornthwaite Citation2009) is balanced by the permanence of traditions of negotiations among governments and organised stakeholders (especially in urban planning, education and social policies), and by the remarkable growth – especially during the financial crisis – of new social collectives and movements (Falanga et al. Citation2019).

The framework outlined so far allows to see inclusion and participation as two different but inter-dependent dimensions of public engagement. The first captures the commitment to increasing input for decisions through engaging multiple ways of knowing (Quick and Feldman, 284), while the second represents the permanent obligation ‘to making connections among people, across issues, and over time (…) intentionally creating a community engaged in an ongoing stream of issues’ to feed its capacity ‘to implement the decisions and tackle related issues’ (274). Understood in this way, inclusion does not merely describe the openness of a process to socioeconomically diverse participants, because it favours connections ‘not only among individuals’ and groups’ points of view but [also] across issues, sectors, and engagement efforts’ (275), and advocates its presence as a permanent accompaniment of the participatory process, that must act in all phases. As such, inclusion focusses on the continuous construction of conditions of equity, that needs gradual improvements and cyclical revisions.

Interrelating the two components of public engagement mentioned above reduces the risk of further dichotomising the separation between the ‘process designer’ and ‘process participants’, or ‘government’ versus ‘public’ (Innes and Booher Citation2004; Roberts Citation2004). It also emphasises the need to constantly alter the process and sustain its temporal openness to guarantee its capacity to incrementally mature and better respond to the challenges of continuous transformation, of both participants and the hosting environment. This aspect of permanent and incremental reshaping of participatory processes has been a central issue in the past years in the debate among the members of RAP-Portugal, as annual reports of joint-activities underline.Footnote13 From this perspective, the RAP surveys raise a third pivotal question, which refers to the presence, or absence, of a ‘co-design’ approach to the construction of inclusion strategies, as a contribution to their effectiveness, efficiency and resilience, through a permanent/incremental transformation of the participatory practices themselves.

An important element of ‘pertinence’ – which deserves to be stressed about the conjuncture that RAP chose to propose for its surveys – refers to the significant increase in the centrality that technology has had in participation, since the explosion of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020, when ICTs became – in several cases – the only usable channel for many pre-existing arenas of social dialogue. Undoubtedly, this added a new layer of complexity to the debate on inclusion. In fact, it crosses both the controversies on the risks and transformations of the digital divide (Chia-Hui et al. Citation2020; Hargittai and Walejko Citation2008; Armenta et al. Citation2012; Warschauer Citation2002, Citation2003; Norris Citation2001), but also significant debates on the capacity of ICTs to promote a diversification of target audiences and institutional arrangements (Rahim Citation2018; Mellon et al. Citation2017; Albrecht Citation2006; Avgerou Citation2002), or – in contrast – to generate further distanciation and disembeddedness of social relationships (Peixoto and Steinberg Citation2020), with their spatial, emotional and democratic consequences (Giddens Citation1990) and new forms of exclusion.

Emerging research on the effects of technology on citizen engagement tends to highlight risks that amplify ‘existing participatory biases favouring, for example, the participation of those who are male, have higher income, or educational attainment’ (Peixoto and Sifry Citation2017). So, careful institutional and technological design will become more and more essential if inclusiveness is a value to be pursued. The need to improve the inclusive technological design of participation systems to leverage new citizen engagement practices and more equity in its use possibly needs a substantial change of pace in how many public institutions look to them. In fact, they require investments (which can increase inequalities among different places and administrations) and multiple rounds of user-research and user-testing more than the present approach uses assumptions about what users’ needs and habits probably are (Peixoto and Steinberg 2000, 67).

In such framework, a new reflection becomes necessary, on how web portals and web platforms, which support institutional processes of participation – which often becomes their main showcase – are exposing and treating diversity related to their potential participants (Helberger Citation2012, 68; Lemos Citation2004; Cogburn Citation2004; Starobinas Citation2004). Such an aspect is becoming increasingly important, but still has not been studied much, and remains untreated in political debates among participation promoters. Thus, the RAP survey on the inclusiveness approach emerging – or not – from the municipal portals dedicated to participation, offers a unique opportunity to observe the behaviour of cities strongly committed with organising formalised arenas for citizens’ participation. In such a perspective, it raises a fourth question that could be answered through the RAP surveys: are these websites somehow ‘mirroring’ their local communities and trying to favour the consolidation of their diversity, offering languages and tools devoted to the more underrepresented in the participatory processes?

Such a question implies a reflection on how bi-directional dialogue with their citizens is promoted by websites specifically linked to participatory processes, and the space they offer for the ‘self-recognition’ of some citizens in their target-audience.

Reflecting on this function of ‘mirroring’ of official portals/websites (in relation to the community, as well as to the fairness of the processes of social dialogue which they support) has barely been studied and assessed by academic literature, and that is why the RAP provocation on that point is a courageous and innovative one.

Somehow, it looks inspired to a specific field of analysis which recently received growing attention in countries like the USA, especially in grey literature linked to Equity Audits. The latter are tools for corporate assessment that – through framing-questions aimed to define and trace diversity, equity, and inclusion – analyse websites, governance structures and main strategic documents of companies or educational institutions under the perspective of their capacity of mirroring the complexity of differences that mark their potential communities of members/users/clients. Such analysis is usually proposed in relation to the demographics of their territories and to the possibility of making them feel comfortable, respected, culturally relevant and possibly empowered within the targeted organisation.Footnote14 Occasionally, academic studies have recently used similar methodologies in their evaluation of school services (Dodman et al. Citation2018), based on the adaptations provided by Feinberg and Willer (Citation2015) and Skrla et al. (Citation2004, 134) for decision-makers ‘to use in their equity-focused work’. But, in general, such literature has not received attention in Europe. So, RAP's attempt at leveraging a debate on the issue with its member cities offers new, meaningful insights by trying to complexify the debate on how local institutions are facing the issue of ‘inclusiveness in participation’.

3. The collection of data and its limits

As mentioned in section 1, the present article was made possible by the preliminary results of two surveys through which the director board and the executive secretariat of the Portuguese Network of Participatory Local Authorities (RAP) intend to leverage further collaborative action-research on the inclusion of underrepresented groups in participatory processes. The exploratory research is part of RAP commitment to remain focused on citizen participation in decision-making despite the tendency of COVID-19 emergency to marginalise its centrality (Falanga and Allegretti Citation2021; Dias Citation2020).

The research, carried on in July/September 2020, was imagined as the basis for further debates and training activities, and was shaped by the social enterprise Oficina (Executive Secretariat of RAP) and the Centre for Social Studies (CES) of Coimbra University, with intense negotiations on languages and the need to protect the anonymity of respondents, remarking that the focus is on ‘the joint production of knowledge (…) to improve our collective approaches’, rather than ‘assessing the performance of each municipality’ (RAP Citation2020b).Footnote15

The main tool was a guiding questionnaire given to member-cities, whose central research was formulated as ‘which strategies and tools do members of the Network develop to increase the involvement of underrepresented people and groups in participatory processes?’ The decision to start the inquiry from the perspective of the cities, instead of that of the citizens, had two main reasons:

One linked to the statutory role of RAP of promoting the awareness of local authorities (and their governing and technical teams) about their capacities and limits, for promoting coherent and adequate opportunities of training and mutual exchanges;

A second referred to the optimisation of existing resources (as far as a large inquiry would have higher costs, and RAP – as an informal entity – has still difficulties in fund-raising of its activities, relaying a lot on investments of single member cities).

It must be stressed that – in the conception of the research – a future survey among citizens has been explicitly mentioned as a possible second-step to enrich the debate on the topic of underrepresentation in participatory processes with different perspectives and ideas.Footnote16

The questionnaire to the RAP member cities was broken into four groups of sub-questions,Footnote17 related – in each territory – to: (1) the list of specific profiles considered as ‘under-represented subjects’; (2) the description of diverse actions undertaken to include them (and the most successful among them); (3) the main perceived changes in terms of participants profiles, and (4) the existence of effective pro-inclusion dynamics in other areas of institutional intervention. Out of the 20 questions, 8 included sub-questions and ‘free text’ to incorporate new issues for future internal debate among RAP members to provide detailed descriptions of exemplifying concrete actions carried out by each LA.

The design purposely chose not to inquire civil servants or politician individually, but to ask ‘member cities’ to delegate someone to respond, so to increase the collective commitment of these abstract entities. The risks of such choice were well know, but carefully calculated, as the survey was intended to ‘provoke’ a future debate and to responsibilise someone in each member city. From the beginning, it was considered that scarce answers (although with a reduced statistical representativity) could be anyway useful to generate a debate in the imagined spaces of self-learning and training for mutual support which RAP constantly shapes. People who formally filled the questionnaire qualify them as key-informants, as they were all civil servants (63,6% women), with an average age between 35–54,Footnote18 prevalently dedicated to participation (with other administrative tasks, too),Footnote19 72.7% have dealt with participation for less than 5 years.Footnote20 As they were involved not as individuals, but as speakers for their administrations, 46.7% requested the support of other colleagues; 20% received support from hierarchical superiors on some questions, and 13.3% answered alone.Footnote21

Unfortunately, only 11 cities out of 62 responded to the survey,Footnote22 despite the high commitment of RAP to stimulate its members to participate. The main justifications exposed by no-responding members, during the first online seminar held to comment on the preliminary results, was mainly related to the difficult period in which the questionnaire was distributed to overburdened teams, its width and complexity, and a certain difficulty in dividing and coordinating internal responsibilities among different officers in charge of participatory processes in each city.

Given the result of the first survey, another research streamline was added in mid-September 2020, using a different methodology (observation by experts), aiming to offer to member cities the opportunity of an external regard on their portals’ performance. This new thread was shaped around the recognition that online platforms and websites – as in many others activities during the pandemic – became central components of participatory processes, and, from a future perspective, they deserve more attention in the way in which their content and functionalities are structured and presented to target audiences. Here, 20 different variables were reported in an observation grid (with open spaces for qualitative notes) aiming to understand how – from a functional and textual/visual standpoint – the websites supporting participatory processes are conceived under a pro-inclusion perspective, and to what extent do they contribute to shape an image which pays attention to the perceptions of its users. The variables refer to four macro-areas: (1) existence of Internet pages with information about the process; (2) images used on the websites; (3) content and languages of the website; (4) accessibility according to different potential users and users with poor internet connections. Although 72.4% of LA also have Facebook accompanying their participatory processes (Nitzsche, Pistoia, and Elsäßer Citation2012), the latter have not been analysed, due to their stiff pre-moulded structures that allow few variations. This observation of the webpages dedicated to RAP members for their participatory processes (under the perspective of their attention to include marginalised/vulnerable potential users) was conducted by an independent research team, to minimise the risk of delayed answers and to maximise the homogeneity of the analysis. The analysis included more judgemental and subjective components which served to compose some ‘scenarios’ or ‘profiles’ (as sort of simplified behavioural ideal-types) that could facilitate a thorough discussion among RAP members in future events.

The limits of both research are set in their presentation: in fact, (1) they focus only on ‘institutionalised practices’; (2) they limit their scope to RAP membersFootnote23; (3) a solution-oriented perspective gives more relevance to solutions than to ontological problems; (4) emphasis on identifying common behaviours, challenges and capacity to respond to problems reduce the comparability of answers, especially of the 8 ‘open text questions’ whose clustering exercise on the part of the research-team has strong connotations of subjectivity; (5) the anonymisation of the dataset – specific approach of this ‘community of practice’ – reduced the possibility of cross-analyses, and of ‘zooming’ on some outputs. Furthermore, some important terms were placed aside on purpose by the research-team (such as multi-layered exclusion, homelessness, etc.) to see if they could emerge spontaneously through the answers.

It must be said that – after the testing phase of the websites’ analysis – one target-city started to improve the inclusiveness of its features, observing that ‘we learnt from this external regard, and many things we never imagined proved easy to modify, at no cost and within a short time’.Footnote24

To maintain anonymity, without missing the capacity of analysing some cross-references of the two surveys, RAP members were clustered into categories (A,B and C) referred to as the ‘class of complexity of participatory activity’Footnote25: 45% of respondents belong to class A (27.7% of the total number of cities comprised in that class), 45.5% to class B (16.6% of the class), while only 1% belongs to class C. Furthermore, 55.5% of them did not entirely suspend they participatory processes during COVID pandemic Footnote26 and 63.3% count on a structured specific department (or at least a uni-personal specific service, in smallest territories) in charge of organising and support participatory processes. Responding LAs represent 58.8% of the total number of RAP members (13/62) which – up to now – invested in a support office for participation. In terms of population, 27.27% of the answering LAs belong to small territories (with less than 30,000 inhabitants), 45.46% to middle-size territories and 27.27% to large territoriesFootnote27 (with over 90,000 inhabitants). It is worth underling that 90.9% of the city that responded to the survey on inclusionary strategies have an ongoing Participatory Budgeting process: so, they are highly representative of those 124 practices of local level, which characterise Portugal (Dias, Enríquez, and Júlio Citation2019).

From what said above, it is clear that this exploratory research could not count on a sample of territories with statistical representativity of the different levels of commitment with citizens participation in Portugal. Nevertheless, answers maintain a high degree of significance, as they represent a ‘high rank’ of LAs that more invest on participation in Portugal. And their high commitment could leverage an important debate on emerging answers, to fuel the next stages of the intended collaborative-research, which had its start in those surveys. The next section will examine them through an ‘inductive’ approach, in search of common patterns which can enlighten the next steps of the community of practices’ collaborative work. A series of interpretative hypothesis will be presented, as a first step for supporting next debates among RAP members.

4. The main data collected

4.1. Selection of data on the inclusive nature of the webpages dedicated to participatory process

The analysis of the potentially inclusive nature of Internet portals and webpages dedicated to participatory processes, conducted on the overall amount of 62 RAP members, revealed 58 positive occurrences. Only 25.4% are subpages of the main LAs’ portals: all the others are autonomous spaces, specifically dedicated to one or more participatory processes, and eventually – as in Cascais's or Valongo's case – hosting an entire ‘participatory multichannel system’ (as defined in Spada and Allegretti Citation2020).

The study, stating that ‘the images used to communicate web content are decisive in the message issued and in the way it is perceived by recipients’ (RAP Citation2020a) excluded 1.5% of occurrences, without images or logotypes. Then, four types of imaginaries transmitted by the pages in relation to the local community were clustered in order to spark further debates among RAP member easier and more intuitive: (1) the first typology (defined as generalist – 53.7% of the occurrences) uses only text and, eventually, the logo of the process; (2) the second, defined as dedicated (17.9% of cases), makes use of content taken from image banks/databases; the third (3), called careful (9% of cases) use images of local citizens, without ensuring the diversity of profiles; and (4), finally, 17.9% of websites fall into the category named as integrationist. The latter uses images of people from their community (often the previous years’ winners of public funding decided through participatory processes), ensuring diversity of profiles – in term of ethnic appearance, gender and/or age. Similarly, the analysis done on the language used in the textual content, revealed only 3 webpages (5.2%) with gender-sensitive language, while 55 (94.8%) tend to use simplified language making it friendly and accessible to people with low levels of literacy.

If most analysed websites tend to show accurate planning of their user-friendly performance,Footnote28 the same cannot be said when it comes to assessing specific functionalities which could make certain types of users’ lives easier. The table below shows that websites of participatory processes barely seem conceived to facilitate access to people with visual or hearing impairments, and only 82.8% provide a variety of contact that can guarantee diverse direct forms of biunivocal communication between citizens and administrative services.

refers to functionalities, specifically related to the use of websites to support the different phases of a participatory process. 86.2% of the webpages facilitate various activities such as: registering, voting, sending proposals or commenting onlineFootnote29; conversely, only 27.6% have additional downloads which provide more information.Footnote30

Table 1. Existence of functionalities – in the webpages of participatory processes – which can favour a friendly access to some minorities/traditionally under-represented groups.

Isolating the 10 LAs which were part of both analyses referred to,Footnote31 no significant deviation characterises their behaviour. There are just few exceptions, partially emerging from the last three columns of .

4.2. The inquiry on underrepresentation in participatory processes

Due to the low level of answers collected by this survey (although they were partially compensated by the fact that respondents constitute the highest percentile of committed cities with the most important and innovative participatory processes in Portugal), in the following pages only few tables that recompile the quantitative data collected are exposed. In fact, they can be read in the official publication issued by RAP (Serrano et al. Citation2021), while a qualitative-oriented reading could help to formulate some exploratory interpretative hypotheses, being useful in the next phases of the collaborative research among RAP members. When quantitative results are exposed, this is because they photograph interesting concentrations or dispersions of answers, offering some useful interpretative insights.

4.2.1. Who are the underrepresented?

The first set of qualitative data tried to capture the perception of respondents about the global presence in their local participatory processes of those groups who literature traditionally indicates as at risk of underrepresentation (Gherghina, Mokre, and Miscoiu Citation2020; Bruell, Mokre, and Siim Citation2012; Wheatley Citation2003; Bauböck Citation2001; Bellamy Citation2000). As for the perceptions about the existence of specific forms of territory-based underrepresentation, the majority of respondents identified the most significant with places poorly connected to inhabited centres; 1/3 referred to stigmatised neighbourhoods and/or deprived areas; around 10% (all in cities of populational, Class 3) to gated condos and/or areas with high purchasing capacity; few to rural or mountain areas, and other situations such as homeless people who stay overnight in urban areas or single derelict buildings that host families in extreme poverty.Footnote32

When requested to list 3 types of individual/groups traditionally at risk of underrepresentation, and for which is easier or most difficult to propose, finance and implement actions aimed to increase their inclusion in participatory processes, the answers were the following ():

Table 2. Social groups at risk of underrepresentation which are considered easier or most difficult to reach through specific inclusion strategies (Q10; Q11).

4.2.2. Between discourse and action

A second cluster of questions focussed on the relation between the discursive importance of inclusion of underrepresented groups and the reflexive action to favour it. It shows some disconnections and mismatching between answers, resulting into an interesting topic for the future collective reflection among RAP members involved in the collaborative research. Negotiating the formulation of such questions was the most difficult part of the questionnaire conception, as they include ‘judgemental’ reflections (Chew-Graham, May, and Perry Citation2002).Footnote33

When questioned about whether the importance of the topic inclusion of underrepresented groups in participatory processes is debated within each territory, almost 3/4 of respondents answered ‘yes’, only 1 said ‘no’ and around 1/5 selected ‘I don’t know/I can't answer’. The places where this debate takes place – according to respondents – are mainly: (1) the ‘social intervention’ department in general; (2) main ‘flagship’ participatory processes promoted by the LAs (as Participatory Budgeting); (3) specific actor-based institutions (such as Youth Councils, Councils devoted to People with special Needs, Fora for Immigrants, Roma People Council); (4) more rarely, specific Research Projects related to participatory practices, or inquiries/polls linked to special events (such as the European Local Democracy Week). One LA specified that the ‘co-design’ of rules, done with children, for a participatory process dedicated to them, was an important opportunity to debate about inclusionary strategies.

It is significant that, when asking to what extent three different statementsFootnote34 appear to be important to justify the implementation of actions to include underrepresented groups in participatory processes, almost 50% (or more) of respondent chose the option ‘I do not know/I can't answer’.

Finally, respondents were requested to state if they consider that all departments/services are equally committed to implementing actions to increase the presence of underrepresented groups in public policies; almost 3/4 of respondents answered ‘No’.Footnote35 Addictions specified that departments are usually more sensitive in areas related to education, culture and those that, in urban planning, deal with deprived areas and informal settlements.Footnote36 Such conclusions match with a study done by Falanga in Citation2013 on different participatory processes in the municipality of Lisbon.

4.2.3. Strategies and specific measures for inclusion

The last cluster of questions, focussed on the strategies which were implemented in each municipality to involve individuals and groups at risk of underrepresentation, had – in general – a more qualitative nature and a wide diversity of answers related to different methodologies and typologies of participatory devices.

Asked to what extent, in the last years, have actions been implemented to promote a greater presence/inclusion of underrepresented people in participatory processes, almost 1/2 of respondents answered that several measures were adopted; nearly 1/4% that a large number of measures were adopted, and an equal number that ‘some scattered measures were adopted’. Nobody reported cases with no measures or few measures.

When respondents were asked to depict which level of commitment – in the last years of participatory processes in each LA – their municipality had in relation to the promotion of inclusiveness (Q7), only less than half considered representative the answer ‘The local authority invested in a thorough policy to increase the diversity of participants in participatory processes they considered the following statements true’, and only 4 out of 11 judged very true that ‘the local authority made frequent assessments of the presence and absence of underrepresented groups in participatory processes’. Instead, the majority of answers (6 out of 11) converged on the sentence ‘the theme of social inclusion in the local authority seems to be a main concern of the policies of social assistance, but not of the participatory processes’. Instead, even more respondent (8 out of 11) declared that they identify with the sentences ‘the policies of social assistance in the municipality always include a participatory strand of dialogue with beneficiaries’ and ‘the policies dedicated to vulnerable or marginalised territories always include a participatory strand of dialogue with beneficiaries’.

The answers received in the free-text boxes to the question ‘Why the usually under-represented groups listed in are easier to reach?’, can be reorganised into 6 clusters ():

Table 3. ‘Why the usually under-represented groups listed in are easier to reach?’ (Main Clusters deduced from Q10.4.).

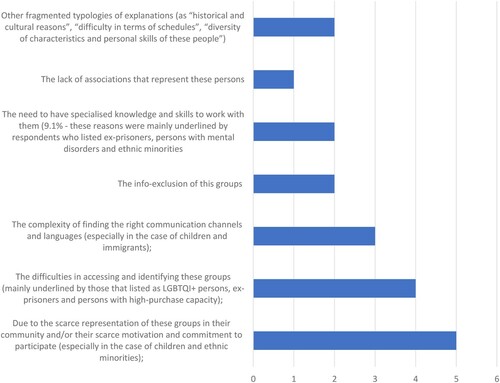

The range of reasons that justify why some underrepresented groups are considered ‘more difficult’ to reach than others can be clustered as in :

Figure 1. ‘Why the usually under-represented groups listed in are more difficult to reach?’ – Interpretation and clustering of main answers (N = 19).

When questioned about what the main reasons that – in recent years – prevented the implementation of measures to include individual and groups that end up being underrepresented in the participatory processes of each LAs,Footnote37 the respondents mainly pointed out: the limits of technical teams (almost 1/5); the lack of knowledge of appropriate methodologies (almost 1/5) or bureaucratic difficulties and high costs of the measures. For almost 1/5 of them, this has not been a focus or an issue in the processes; and for 1 respondent the motivation was a lack of response by target-audiences. Three of the motivations proposed where not chosen by any respondents: (a) difficulties in reaching a political consensus; (b) opposition by other social/territorial groups; (c) and negative press-campaigns.

The existence of specific communication strategies and tools used in the context of participatory processes for mobilising underrepresented groupsFootnote38 was referred by almost 3/4 of respondents, pointing out a diverse range of solutions. Only 1/4 declared that communication shows no focus at all on underrepresented groups. The majority of answers (almost 1/3) underline the existence of a wide range of complementary means (usually mixing different forms of publicity in the public spaces, with announcements in mass media and social networks, and the involvement of key-resource persons in the communities who can spread information through their contacts and territories); 1/4 of the answers stress the use of a suitable/adaptable language with those target groups, and few quote the use of images that mirror and illustrate the diversity of people and social groups in their local territories. These images are substantially in line with the independent analysis which was conducted on the websites.Footnote39 Conversely, the attention declared here on the adequate use of languages, when communicating with underrepresented target groups, reveals some mismatches in relation to the observation, that demonstrate – at least for the websites – a general lack of attention to provide functionalities that can facilitate the communication and interaction with different categories traditionally at risk of underrepresentation (such as citizens affected by different types of physical impairments).

Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that the detailed answers to the questionnaires describe a series of face-to-face practices which are complementary to web-based ones. Clustering them into groups that mainly refer to: (1) the production of leaflets, posters and other informative materials in different foreign languages and with images of multicultural environments; (2) informational and explanation sessions organised for some underrepresented categories in collective structures where they use to gather (such as schools, universities and youth associations, day-care centres, clinics for persons with mental diseases, meetings in the squares for favouring the dialogue with homeless people, or ‘localised sessions’ in deprived areas of the municipal territory); (3) the creation of ballot-boxes for voting in different places (including, shopping centres and elderly associations, libraries and municipal buildings, so to attract the attention of citizens beyond the ICT-based informational spaces); and (4) travelling information-cars or coaches, neighbourhood walks and other forms of ‘outreach’, that can increase the ‘proximity’ to target-citizens, and the ‘decentralisation’ of the communication strategies related to participatory processes.

When requested to list up the names of three participatory processes that have proved most effective in including people/groups traditionally underrepresented (Q9), 5 respondents listed their Participatory Budgeting and 6 their Youth Participatory BudgetFootnote40; 3 quoted other processes of youth involvement (such as, the Child-Friendly City Action Plan; Student Forum and Mini-Presidents Project) or senior-citizens involvement (Clube Idade +); 3 listed thematic local plans, with a social approach (Social diagnostics; Local Plan for the integration of Roma Communities; Municipal Plan for the Integration of Immigrants; Plan for Equality; Social and Health Development Plan) or with a physical planning perspective (urban rehabilitation plans).

Due to this large diversity of the participatory processes which are taking place in the municipalities involved (Q5), a precise mapping of ‘reference strategies, with proven success, in involving underrepresented groups listed in in participatory processes’ is not an easy task. Main clusters summarising the most significant recurrences include:

the direct involvement of schools (including private ones), daycentres for the elderly and private institutions of social solidarity in the mobilisation phases of participatory processes (eventually through the creation of devoted streamlines dedicated to specific social groups, such as Youth or School participatory Budgeting);

the creation of ‘spaces of convergence’ for different social organisations which work with an advocacy of rights of specific social groups, offering them a place (named as ‘Casa Comunitaria/Community Home’, or ‘Home of Grassroots Organisations’ or similar names) to establish their seats and organise their meetings (Especially in deprived neighbourhoods or areas with limited communication with main settlements);

the consolidation of ‘outreach initiatives that bring the participatory processes closer to the territories where people live and gather’Footnote41 (with special meetings in single associations, elderly centres, universities, institutions for people with mental disorders etc.);

some specific fora or plans (such as Municipal Youth Plans, Plans for Full Accessibility of the Municipality, Local Health Promotion Strategies or Plans for the Integration of Immigrants and/or Roma Communities) are often the opportunity to explain other participatory processes, and to involve their specific target audience in other wider spaces of civic engagement;

in some cases, questionnaires targeting specific problems of some groups and individuals at risk of underrepresentation, are seen as an effective ‘first step’ for recontacting them in view of their involvement in more participatory settings;

more rarely, ad hoc symbolic recurrences as the European Local Democracy Week, the Students’ Day or similar, are used for ‘organising events that somehow work as space for talent-scouting and dialoguing with specific social groups which are often absent from our participatory processes’.Footnote42

It is worth to note that Participatory Budgeting is – per se – listed also among the ‘strategies’ for inclusiveness of participatory processes, as ‘it results in more trust than other processes, because of it grants concrete and visible effects. And this attracts people that usually mistrust institutional action – people who could, by the way, be listed among the underrepresented (…)’.Footnote43 Namely, one answer quotes (by describing a concrete case happened in its municipality) the importance of the administration paying attention to the implementation of proposals that can benefit underrepresented vulnerated groups, which emerged in participatory processes but eventually did not went through and did not managed to receive funding through them. This could ‘solidly reinforce the self-confidence of some groups at risk of underrepresentation and make them feel recognised and cared for’.Footnote44

In relation to this complexity, also clustering the large variety specific actions that – within the inclusionary strategies – were experimented with to specifically include the groups mentioned in Q5 of represents a difficult task. However, it is worth to underline some main recurrent typologies, as for example:

Training actions and targeted information sessions;

improvement of the multichannel dynamics of participation (for example, adding online interaction to mainly off-line processes; or adding face-to-face sessions in specific places, for once-mainly-online processes);

adding decentralised sessions in diverse locations and at different hours of the day;

reducing the barriers to the participation of some groups through modifying process’ rules (i.e.: decreasing the minimum age for voters in the participatory initiatives; opening more spaces to no-residents; adding languages, etc.);

structuring collaborations with the social assistance department for the ‘cross-selling’ of participatory processes while offering psychosocial support to specific groups (i.e. ex-prisoners; Roma communities);

offering training and technical support to all citizens who require it (‘on-demand’ offer of public support: i.e. babysitting sessions for families interested in public meetings; free-of-charge transportation and/or accompanying persons to support individuals with special needs; cultural mediators/translators for supporting foreigners, etc.);

combining participatory processes with playful-pedagogical activities (such as theatre, role-plays and music sessions) to make them more attractive to diverse audiences;

economic-support measures, that can make the groups at risk of underrepresentation feel that ‘someone cares about them’;

investments in more attentive conditions of participatory settings (chairs in the first-row reserved for people with special needs; voting ballots written in braille, etc.).

Requested to specify if the strategies and specific actions listed above managed to increase the involvement of the target groups listed by each city in (Q5), 10 out of 11 respondents answered ‘yes’.

To the question ‘in which phases of the participatory processes the actions aimed to inclusion tend to concentrate’, the majorityFootnote45 responded ‘Mobilisation of ideas’ (around 1/5) and ‘Voting/ranking of projects and ideas’ (1/5), while other phases were reported as less important (few quoted: ‘Preliminary information phase’; ‘Selection of actions that can favour inclusion’; ‘Analysis of satisfaction of participants and process performance’; and what is usually conceive as the real ‘deliberative phase’, i.e. the phase of ‘Ideas detailing and elaboration’). Less attention was paid to the phases of ‘Construction of indicators to assess the process’ (1 respondent) and ‘Monitoring of process’ results and implementation’ (2 respondents).

Finally, when asked if the municipality ever used a ‘random selection’ methodology, as a measure to ensure greater social representation, the respondents gave convergent answers (1/2 never; 1/5 ‘it was discussed but no implemented’; only 1 out of 11 said ‘having used this method’, without explaining the context).Footnote46

5. Emerging common patterns: some hypotheses

Observations collected in the two surveys suggest that, in the last decade, the growth of Portuguese participatory processes was neither accompanied by a refined work for diversifying their participants, nor by the will to flee from what was already experienced (by others). In this frame, the topic of inclusion of underrepresented actors seems more a goal of the overall policies of administrative authorities (so, posing an issue to the improvement of the function of representative democracy) than a specific question – and an imagined mission – of participatory processes. Such a vision seems barely ‘problematised’ by Portuguese LAs, as proved by the results of the observation conducted on websites. Despite the respondents represent public authorities highly committed with participatory processes, very reduced appears the attention to invest in the monitoring and evaluation of participatory processes, and – even more – in codesign strategies to include the under-represented citizens who they declare they would like to involve more.

Actually, it must be stressed that the starting phase of the action-research promoted by RAP among (and on) its members, defined – although loosely – the concept of ‘under-representation’, but the definition of ‘participatory process’ was left to their autonomous imagination. This gave rise to two major families of interpretations (section 4): some considered all the collective dynamics of social dialogue, both those focussing on specific actors (such as plans for social integration) and the more generalist participatory processes that promote scenario-visioning for a territory, as well as a shared rethinking of different policies and projects. The latter, in contrast, was the main centre of reflection for those respondents who deal with participation as a specific policy and look to actor-based processes (focussed on specific social groups) just as pre-conditions, or preliminary actions, to build a more equal and fair society that could mirror itself in the general audience of large-spectrum participatory processes. Indeed, it is not surprising that this second vision emerges more clearly from those LAs that have a wider complexity of participatory processes (Class A), and a special office or department in charge of participation.

As the questionnaire had no details to depict the quality, articulation and methodological characteristics of each process quoted – some doubt remains about: (1) which processes are sectoral policies with a strand of social dialogue with beneficiaries; (2) which are conceived from the origin as participatory devices used to target specific groups, (3) which are addressed to the whole population of a territory, or a sub-area, and incorporate affirmative actions (Sigal Citation2015) to revert some absences and enrich the diversity of participants and interests represented. Paraphrasing ethical philosophy, we could say that not only institutionalised participatory practices, in Portugal, tend to coagulate around the macro-categories of: (1) deontological; and (2) consequentialist ones (Allegretti Citation2018), but also practices aimed at inclusion (in connection with devices of social dialogue) tend to do the same.

If deontological actions of inclusion are tautologically justified by a generic idea of inclusion of usually underrepresented people as something ‘good per se’, consequentialist actions to promote inclusion within participatory processes focus on translating their strong objectives into action (using specific tools which guarantee consequentiality and coherence between motivations, aims and targeted results, and evaluating them accordingly). But they remain few.

5.1. Three main asymmetries

Data shows that ‘social inclusion’ is declared as an important mission of public LAs, and – as such – is the object of several actions and policies. Combining the RAP researches, one cannot penetrate in any reliable analysis of the quality of Portuguese participatory processes, and their inclusiveness; but interesting dynamics suggest ‘asymmetries’ in the relation between the two complementary domains of participation and inclusion: